Protecting Victoria's Coastal Assets

Overview

Victoria’s coastline is one of the state’s major assets. The coast and its built and natural assets are under increasing pressure from population growth and climate change.

Threats to coastal assets affect the commercial, recreational and environmental services they directly provide or support. It has been estimated that, in Victoria, a 0.8-metre rise in sea level by 2100 will put most of our coastal infrastructure and assets at risk of inundation or erosion.

Given the value of Victoria’s coastal assets and the significant threats they face from current and future coastal hazards, it is important that they are adequately protected.

The government, through the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), is currently implementing a range of reforms to improve the legislative framework, governance, planning and management arrangements for the coast.

This audit examined whether natural and built assets on Victoria’s coastline are adequately protected against current and future erosion and inundation hazards. We looked at the adequacy of individual agencies’ asset and risk management approaches, funding for assets at risk, and statewide coordination of coastal asset protection. Based on the issues identified, the audit also helped to assess and further inform the reform process.

We audited seven agencies responsible for protecting coastal assets—DELWP, Parks Victoria, VicRoads, East Gippsland Shire Council, Mornington Peninsula Shire Council, Gippsland Ports and the Great Ocean Road Coast Committee. These agencies manage a range of significant coastal assets, coastline areas and risks.

We made three recommendations for DELWP, and three further recommendations for coastal managers including DELWP.

Transmittal letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2018

PP No 379, Session 2014–18

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Protecting Victoria's Coastal Assets.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

29 March 2018

Acronyms

| AMAF | Asset Management Accountability Framework |

| CoM | Committee of management |

| DEDJTR | Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources |

| DELWP | Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

| DEPI | Department of Environment and Primary Industries |

| DSE | Department of Sustainability and Environment |

| EGSC | East Gippsland Shire Council |

| GORCC | Great Ocean Road Coast Committee |

| GP | Gippsland Ports |

| ISO 31000 AS/NZS | ISO 31000:2009 Risk management—Principles and guidelines |

| LCHA | Local coastal hazard assessment |

| MPSC | Mornington Peninsula Shire Council |

| NCCARF | National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility |

| PV | Parks Victoria |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VCC | Victorian Coastal Council |

Audit overview

Many Victorians live, work and play close to the coast. It is home to over one million people—19 per cent of the state's population—and four out of five Victorians visit the coast every year to enjoy a wide variety of recreational pursuits.

The coast is also the destination for a growing domestic, national and international tourist market, with nature-based tourism one of Victoria's key growth industries and a major contributor to our economy. In 2015–16, tourism along the Great Ocean Road and the Mornington Peninsula reportedly generated $795 million and $700 million respectively.

|

Coastal inundation is the temporary or permanent flooding of low-lying areas caused by high sea level events, with or without the impacts of rainfall in coastal catchments. |

Built and natural coastal assets provide valuable services and add value to the environment, the economy and the community. When natural and built structures, such as sea walls, beaches and dunes are intact, they protect against coastal inundation and erosion hazards. This protection is important for land and water based coastal assets including critical infrastructure, such as telecommunications, drainage and sewerage networks.

Managing and, where needed, safeguarding these protective structures is as important as managing and protecting the water and land based coastal assets they shield. While protecting our coastal assets is important now, it will become even more so with the predicted effects of climate change and population growth.

In Victoria, 96 per cent of the coast is public land overseen by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP):

- Parks Victoria (PV) manages approximately 70 per cent, the majority of which requires a high level of conservation protection.

- Councils, local port managers and committees of management (CoM) manage a further 20 per cent reserved for recreation and conservation purposes.

- DELWP directly manages the remaining 6 per cent, which is not reserved for a particular purpose.

We audited seven agencies that represent coastal managers of different types and sizes. All have responsibilities for managing significant coastal assets and coastline areas at risk of inundation and erosion. The agencies were:

- DELWP

- PV

- Mornington Peninsula Shire Council (MPSC)

- East Gippsland Shire Council (EGSC)

- Gippsland Ports (GP)

- Great Ocean Road Coast Committee (GORCC)

- VicRoads.

We focused on how well these agencies are managing and safeguarding their coastal assets, including:

- coastal protection structures―natural and built

- maritime assets—including jetties, piers, wharves and boat ramps

- access assets—including stairs and boardwalks

- natural assets—including beaches, biodiversity, cliffs, coastal parks, sand dunes, coastal plants and animals.

Good asset management starts with agencies knowing the number, type and condition of their assets and understanding the hazards and risks facing them. Agencies can use this knowledge to prioritise asset works, to make the best use of available funding. It also requires skilled and adequately resourced managers.

Conclusion

A common theme in many of our audits that examine infrastructure is that agencies generally are not managing their assets as well as they need to. This is the case for Victoria's coastal assets—agencies are not managing their assets adequately to protect them from current and future hazards.

There is a real risk, in the near future, of Victorians losing valued assets and infrastructure along the coast. This is partly because not all agencies have complete knowledge of all the assets for which they are accountable, or of the assets' age and condition. Targeting of scarce funding also does not properly consider risks, and significant unfunded maintenance backlogs remain unaddressed.

Compounding this, poorly integrated planning and fragmented responsibility for coastal assets across agencies of various sizes and capabilities works against a cohesive and strategic perspective. Such a perspective is necessary for managing the inundation and erosion risks caused by climate change and the pressures of increased population growth now and in the future.

There is a strong case for more top-down management that takes a statewide view of our coastal assets, hazards and risks. While such an approach requires investment in a consolidated asset inventory, it would make it possible to eliminate the inconsistency in management approaches and practices across agencies. It would also promote integrated thinking and serve to better target funding to protect our most valuable built and natural assets.

Findings

Each of the seven audited agencies is engaging in some good on-ground local work to manage and protect coastal assets from current coastal inundation and erosion risks. This work ranges from repairing beach access stairs after storms and rebuilding eroded beaches, to protecting dune vegetation and nesting shorebirds.

However, overall natural and built assets on Victoria's coastline are not being adequately protected. The audited agencies' ability to do this strategically and cost-effectively is limited by weaknesses in their coastal asset management practices and a number of governance and management barriers:

- Coastal assets are not a focus for larger agencies, because they make up only a small subset of agencies' overall asset portfolios.

- The limited knowledge about existing coastal processes, such as wave behaviour and sand movement, and uncertainty about the likely impact of future climate change reduce agencies' ability and confidence to act.

- The need to focus on the safety risks that failing coastal assets may pose diverts agencies' attention or leaves little time for them to consider other risks.

- The lack of a risk management culture means staff consider and respond to risks informally during their daily activities but do not systematically assess risks or document their response activities.

Additional barriers at the state level affecting the management and protection of coastal assets include:

- poor oversight by DELWP across all public coastal areas contributing to overly complex planning and management arrangements

- the skills and capacities of coastal managers not aligning with what is needed to manage and protect assets

- constraints on funding, how revenue is generated, and where and when it can be spent

- the lack of a statewide perspective on what areas are at greatest risk from coastal hazards, as well as on what assets are currently being protected or need to be protected

- the lack of effective guidance and support provided by DELWP to its coastal managers to be effective risk-based asset managers.

Asset management

We assessed the agencies' asset management approaches and practices against key elements of the Department of Treasury and Finance's Asset Management Accountability Framework (AMAF), including its March 2017 Implementation Guidance.

Asset management practices

Across the audited agencies, a 'fix on fail' approach prevails. Management decisions focus on the assets in poorest condition without considering other important aspects, such as the service the asset provides, its level of use and the risks it faces from hazards, such as coastal inundation and erosion.

Only PV (for its maritime assets), GP and MPSC systematically plan, deliver and regularly review their maintenance programs, making good use of available asset information. The other agencies primarily focus on the assets in worst condition, or simply follow the previous year's maintenance activities. This means the agencies do not use routine maintenance effectively to optimise asset life and keep coastal assets functioning as needed and for longer.

Agencies record different aspects of asset information in different databases and spreadsheets. These systems are not all linked, so they cannot readily use all the information they have to guide their asset management activities. They also make little use of their systems to interrogate the data or use it to inform their asset management practices and decisions.

In the larger agencies we audited, we identified some common reasons for poorer management of coastal assets:

- Coastal assets receive less attention or are not included in the agency's standard asset management practices because other more critical assets have higher priority. Further, assets in inland areas outnumber those in the narrower coastal areas.

- Asset management is not the main focus of the agency's work.

- Agencies rely on staff experience and knowledge instead of applying robust systems and processes to maintain and protect their assets.

Across the audited agencies, funding restrictions and shortfalls limit their ability to manage their assets effectively. For the smaller agencies—GORCC and GP—staff capacity and funding limit opportunities to improve asset management systems and practices.

A number of improvements are underway. DELWP and PV are developing new asset management systems and electronic field tools to improve the management, quality and consistency of the data they collect. MPSC is also developing a new asset information system. VicRoads and PV have reviewed their asset practices and are working to meet AMAF requirements.

Asset knowledge

There are thousands of built coastal assets across the state, including coastal protection structures, but there is no comprehensive statewide register that records them. Only two of the audited agencies—MPSC and VicRoads—have identified and listed all of their assets.

There is also no inventory of the assets that coastal protection structures are intended to protect. These natural and built assets and critical infrastructure include houses, lifesaving clubs, and sewerage, drainage and telecommunication networks.

No one agency or system collects asset condition information across the entire Victorian coast. Agencies use different asset information systems to store data, which limits their ability to share information and compile a statewide dataset.

Asset condition

Many of Victoria's coastal assets are approaching the end of their life or are deteriorating.

There is limited information on the condition of coastal assets across the state. Based on the data that the agencies could provide, between 20 and 30 per cent of coastal assets are in poor condition, and between 30 and 50 per cent are estimated to have less than 10 years' useful life remaining.

None of the audited agencies have complete and robust information on the condition of all their coastal assets, although they generally have good knowledge of which are failing. This information gap occurs because they either do not collect condition information on all assets, or their collection methods are not regular, comprehensive and consistent. The agencies rely strongly on visual inspections. With the exception of PV and MPSC, they do not complement these programs with periodic technical and underwater inspections. These are only done on the assets in poorest condition. Technical inspections are expensive but without them agencies cannot proactively identify potential performance failures for some types of assets.

Risk management

We assessed agencies' risk management practices against the international risk management standard AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009 Risk management—Principles and guidelines (ISO 31000). This standard provides the foundation for the state government's risk management guidance and DELWP's 2012 Victorian Coastal Hazard Guide .

Current risks to assets

The audited agencies do not have a good understanding of the current risks to their coastal assets from coastal inundation and erosion.

We identified a fundamental disconnect between the agencies' asset and risk management practices. While all agencies assess risks to individual assets before they undergo major works, only three of the seven have assessed relative risks across their asset portfolios to target their asset management activities and funding.

The agencies' assessments reveal relatively few assets at high risk from coastal inundation and erosion, but the accuracy of these results is uncertain due to the high variability in the quality of the agencies' risk assessment processes.

Limited understanding of risks also stems from critical gaps in coastal hazard knowledge and asset information, which is integral to coastal asset risk assessments. While DELWP and its predecessors have significantly improved coastal hazard data at the statewide level over the last decade, gaps remain, particularly in information specific to local areas, and how multiple and successive hazards may affect an asset over time.

Risk assessment practices

The quality of the agencies' risk assessments varies, both within each agency and between agencies. This hinders effective statewide prioritisation of funds to treat the highest-risk assets. The assessments vary because agencies:

- do not comprehensively or consistently apply the risk assessment process described in ISO 31000 and the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority's 2016 Victorian Government Risk Management Framework Practice Guide

- do not generally use the range of available information to support their assessments, such as information about coastal inundation and erosion hazards, visitor use and levels of service required.

We identified four key reasons for the lack of a strong risk-based approach to agencies' asset management and funding activities:

- Several agencies have a weak risk management culture and capability, or use informal practices for risk assessment, which may result in staff applying agency risk frameworks or approaches inconsistently.

- Except for DELWP and PV, agencies lack staff with the necessary skills and experience in coastal hazard identification and risk assessment.

- DELWP's limited oversight of CoMs' risk assessment and management processes means DELWP does not know whether the committees are regularly and effectively assessing risks to coastal assets.

- DELWP's risk-based guidance is not tailored to the range of capacities and skills of CoMs.

MPSC, GP and GORCC are working on their corporate approach to risk management and plan to apply these improvements to their coastal asset management practices.

Risk-based funding decisions

The audited agencies are not effectively targeting funding and works to protect coastal assets at the greatest risk. Instead, funding decisions are mainly based on asset failure, poor condition or the need to renew assets as they near end of life. Agencies seldom, or inconsistently, document how work priorities and funding decisions relate to the service the asset provides, its value and need, or the level of risk associated with the asset.

Only PV and VicRoads consider risk when prioritising their investment in major works. However, even these agencies fund works for some lower-risk assets ahead of all identified high-risk assets.

DELWP is developing a risk-based decision-making framework to improve the way it prioritises works on coastal protection assets.

Responding to future risks

Climate change will affect the nature and potential impact of coastal hazards in the future. In particular, rising sea levels and increased storm intensity are predicted to expand and intensify inundation and erosion of coastal assets. Victoria's Climate Change Act 2017 and Victoria's Climate Change Adaptation Plan 2017–2020 (the Adaptation Plan), establish the need for agencies to support and deliver actions that will mitigate or adapt to climate change hazards. These are actions designed to make communities' built and natural environments resilient to the predicted impacts of climate change.

While the practices for managing current risks need prompt attention, agencies also need to consider the long lead times required to plan and deliver appropriate responses to future climate change risks.

Knowledge of climate change risks

There is an incomplete understanding of future climate change risks to Victoria's coastal assets.

Some of the audited agencies—DELWP, PV and VicRoads at a statewide level, and GORCC at a local level—have assessed future risks to their coastal assets, based on how climate change is predicted to impact existing coastal hazards. The other agencies consider climate change risks as part of individual asset and risk management activities, but they have not systematically assessed future risks across their asset portfolios.

In 2015 and 2017, DELWP's assessments of 17 significant types of coastal assets identified that many would be at high risk from coastal inundation and erosion hazards by 2040 and most by 2100.

DELWP's work raises significant concerns about Victoria's ability to adequately protect its coastal assets. None of the existing risk controls were considered likely to effectively mitigate these risks, and actions to address the risks have been slow and limited.

DELWP's 2017 assessment contained a more comprehensive spatial model and hazard information. DELWP plans to make the modelling and data available to coastal managers in 2018. It has also started a project to improve the comprehensiveness of its forecasting and climate change projections by collecting wave data.

Agency actions to address climate change risks

Across the audited agencies, there are limited examples of strategic and systematic implementation of actions to respond to climate change. Further, agencies' actions to adapt assets for climate change are largely ad hoc.

All of the audited agencies, even those that have not systematically assessed climate change risks across all their coastal assets, demonstrate that they consider climate change risks. For example, these risks are considered when planning major upgrades for individual assets, renewal or replacement and through strategic and operational risk assessments.

None of the four audited agencies that assessed climate change risks across all their coastal assets have embedded the outcomes of these assessments into planning and management across their portfolios.

The audited agencies do not effectively stage or adapt their risk responses over time. This is primarily because they do not have the triggers and monitoring information needed to identify when to implement or revise their risk treatment approaches.

The role of land use planning in managing future risks

While planning schemes have limited application for protecting developed areas from coastal hazards, they do regulate future coastal land use and development. In this way, they are a key tool for reducing communities' exposure to coastal hazards and mitigating the impacts of inundation and erosion.

Coastal councils have not used land use planning controls or planning scheme overlays consistently or to their full potential, to protect coastal assets from current hazards and the predicted impacts of rising sea levels as a result of climate change. Only three of the 19 coastal councils have controls in place, although MPSC has a planning scheme amendment underway to implement controls. Councils that we consulted during the audit cited difficulties in translating and implementing coastal planning policies and sea-level-rise benchmarks into land use and development decisions.

Reasons for slow progress in responding to climate change

There are several common reasons for agencies' generally slow progress in responding to climate change:

- uncertainty about climate change impacts

- the relatively long time frames before impacts will be felt

- limited capability, capacity and funding to do the work within a standard council term

- an overriding need to focus on managing current coastal hazards.

In addition, liability for planning decisions, the time it takes to inform and engage communities in adaptation planning, and the need for stronger leadership at state and local levels, have also had a strong influence.

Funding

Audited agencies' management of assets is hindered by:

- the amount and uncertainty of funding they receive

- limitations on how they can use this funding

- their inability to generate sufficient revenue to fund their asset management activities.

All agencies except MPSC advised us that funding for coastal assets is inadequate and that the significant gap between available funding and the costs of adequately maintaining high-value coastal assets is increasing.

Industry and agency reports show the annual maintenance investment benchmarks for port and maritime assets range from 2 to 7 per cent of the replacement value. None of the audited agencies invests this amount—the actual figure is closer to 1 per cent of asset value or less.

CoMs do not receive grants for routine asset maintenance and are required to be financially self-sustaining to maintain their assets. The amount of funding available to CoMs for asset maintenance varies significantly across committees and does not align with what is needed.

Further, revenue generated by the audited agencies is not aligned to what is needed to adequately manage and protect the assets they are responsible for.

Audited agencies have limited ability to raise adequate revenue to fund the coastal asset works needed. PV, GP, GORCC, councils and CoMs raise revenue through fees and charges. Their ability to do this relies on their commercial assets and associated fees. The number of these varies significantly in each agency's region. While they do a commendable job with limited resources, they are not able to effectively manage and protect the assets they are responsible for.

In addition, revenue and funding sources are often uncertain, subject to restrictions and unequally distributed. There are constraints on when and where the audited agencies can use the funds they receive, particularly for funding granted through DELWP's statewide coastal improvement program.

Agencies are not delivering all of their planned maintenance activities and major works due to these revenue and funding issues. They also focus on short‑term fixes, for example, fencing off a dangerous asset, rather than long‑term solutions such as repairing or removing the asset. Funding limitations largely keep the agencies in a cycle of reactive works rather than enabling them to balance this with preventative asset management, which would better optimise the life of coastal assets.

The resulting backlogs in maintenance and major works create an increasing financial liability for the state. In 2012, PV estimated this liability at $336 million for its coastal maritime assets. These backlogs also increase the risk of compromised service delivery and public safety issues.

Without improved distribution and funding models for the protection and management of assets, this gap continues to grow due to ageing assets, climate change and population pressures.

Performance in managing and protecting coastal assets

There is no statewide framework for measuring how agencies perform in managing and protecting coastal assets and reducing risks. Nor do the audited agencies individually measure, monitor and report well on how they are performing in protecting their coastal assets. Collectively, performance measures are lacking or do not assess how well coastal assets are performing in delivering their intended function or service.

|

Beach re-nourishment is a process by which sand, lost through natural coastal processes, including erosion, is manually replaced from other sources. |

DELWP administers a range of statewide coastal improvement funds and programs to deliver works and activities to upgrade coastal protective structures and assets. These include erosion works, beach re-nourishment, and habitat and dune restoration.

DELWP regularly evaluates the delivery of its coastal asset improvement programs, but the other agencies generally only assess individual asset works rather than the overall effectiveness of their asset management.

DELWP's evaluations between 2012–13 and 2015–16 show its statewide coastal improvement programs generally deliver planned works within approved budgets and time frames. However, DELWP cannot measure whether these works achieved their aims because it does not measure and report on these programs' effectiveness and overall performance.

At a local level, the audited agencies are largely effective in treating individual assets that pose a public safety risk or that are failing.

The audited agencies do not have enough information at the local level to determine whether the total number of assets at a high risk is increasing or decreasing over time, or whether funds are being used for the assets at highest risk. At a statewide level, the works funded through one component of DELWP's coastal improvement program successfully reduced the risk ratings of the assets involved.

Statewide oversight and guidance

DELWP is responsible for overseeing that public coastal land and its assets are effectively protected and managed, and for providing coastal managers with adequate guidance to enable this.

Oversight

A lack of strong governance and oversight of public coastal land by DELWP and its predecessors has led to:

- fragmented and overly complex coastal management and planning arrangements

- the skills and capacities of coastal managers not being well aligned with responsibilities and asset risks

- a lack of clarity around roles and responsibilities for asset management and maintenance

- a lack of clarity and transparency around coastal funding and expenditure.

Many regional and local coastal plans are not up to date and there is no effective reporting on total funds generated or expended across the coast. DELWP, as a result, cannot provide assurance that revenue and funds are being effectively prioritised to manage high-value, high-risk assets.

These are longstanding issues that have been identified in previous departmental reviews and reports. Our audit found most of them continue to be barriers to the effective oversight and governance of public coastal land and its assets.

Guidance

Coastal managers lack guidance from DELWP on how to protect their assets effectively from coastal hazards. There is a lack of:

- a statewide perspective on what areas and assets are at greatest risk from coastal hazards

- uniform knowledge across managers on what coastal assets are of regional and state significance

- fit-for-purpose guidance on how to effectively manage and protect assets according to risk.

CoMs advised us that DELWP's guidance and support had lessened over the last 12 months. There has been a lack of information sharing and a loss of DELWP technical advice to properly advise and support effective risk-based asset management. There has been no statewide perspective on what areas are at greatest risk and what assets are currently being protected or need to be protected.

While DELWP has undertaken a number of projects to improve information on coastal hazards and their potential impacts, as well as risk-based approaches to protecting coastal assets, it has not shared this information and guidance consistently with its coastal managers.

Progressing reforms

In 2015 and 2016 government called for the review and reform of coastal and marine management and public land management respectively. These reviews identified longstanding governance and management issues that have hindered the effective management of public land and its assets, including the coast.

In 2015–16 and 2016–17, DELWP proposed a range of actions to better integrate coastal planning and management and improve coastal managers' knowledge, skills and capacity to address longstanding coastal governance and management issues. Government has funded or partially funded approximately half of these actions.

The Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change introduced a Bill and proposed transition plan (reform package) to Parliament in December 2017. This reform package outlines a range of legislative and non-legislative actions to reform marine and coastal management, including the development of a new marine and coastal Act, policy and strategy.

Government and DELWP intend this reform process to improve coastal and marine planning and management, to address a range of longstanding issues, and to better align and resource coastal manager capabilities with need and risk.

DELWP has developed a comprehensive 2018–19 business case to seek budget funds to resource the majority of the reform package actions—including those not funded in 2016–17—and to ensure ongoing funding for a range of critical coastal improvement programs and grants.

Actions in the proposed reform package will go part of the way to addressing the longstanding issues identified by internal and external department reviews.

Further work and resources are required to ensure DELWP delivers government's intended reforms including:

- improved DELWP oversight of all public coastal areas and its managers, including PV and coastal councils

- development of a management model that aligns the resources, skills and capacities of coastal managers with accountabilities, and current and future risks across the entire coast

- ongoing streamlining, integration and review of regional and local plans to reduce complexity, address planning gaps and issues, and improve the currency of outdated plans

- review of national and international coastal funding and cost-sharing models to develop a better practice funding model that allows distribution of revenue and funds in accordance with risk and need across the coast and its managers

- clarification of roles and responsibilities for coastal asset maintenance and management

- development and uptake of a risk-based approach to protect coastal assets, including implementation of fit-for-purpose risk-based guidelines for its coastal managers.

Victoria's valuable coastal assets will continue to be at significant risk without adequate and more effectively targeted funding. The timely implementation of reforms is needed, particularly as risks to our coastal assets grow due to climate change and population growth.

Recommendations

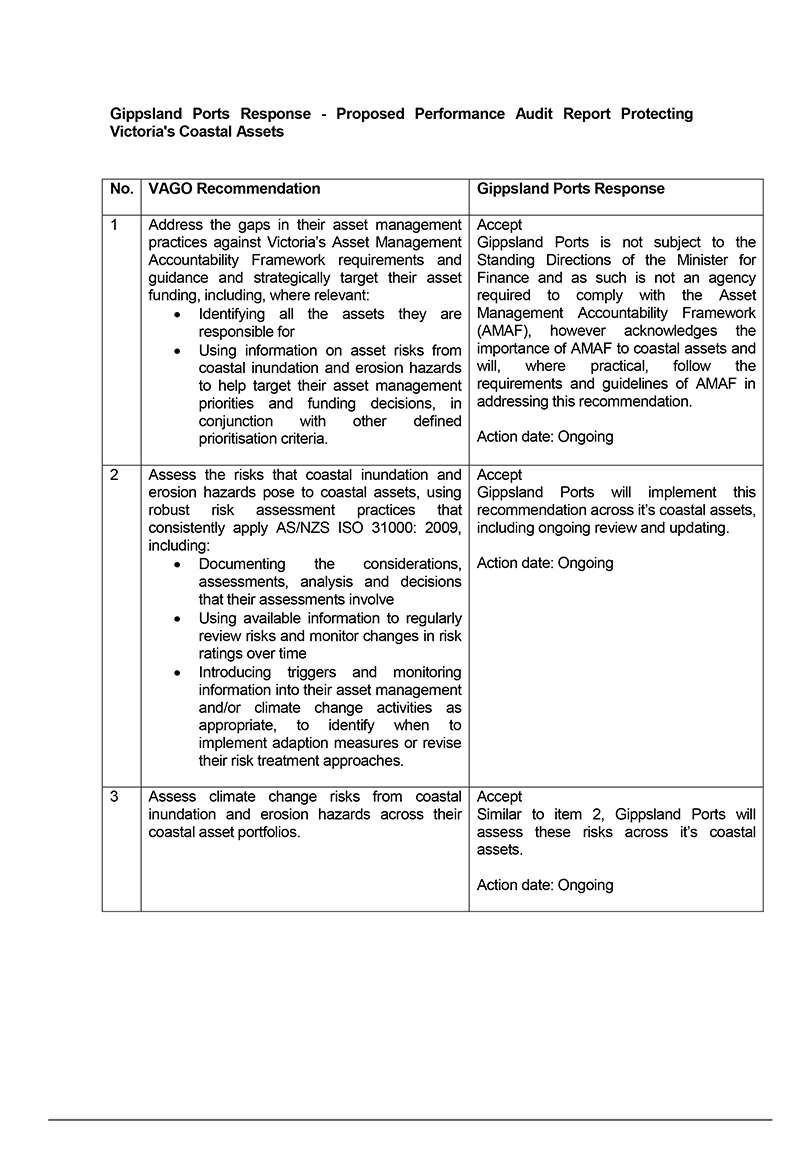

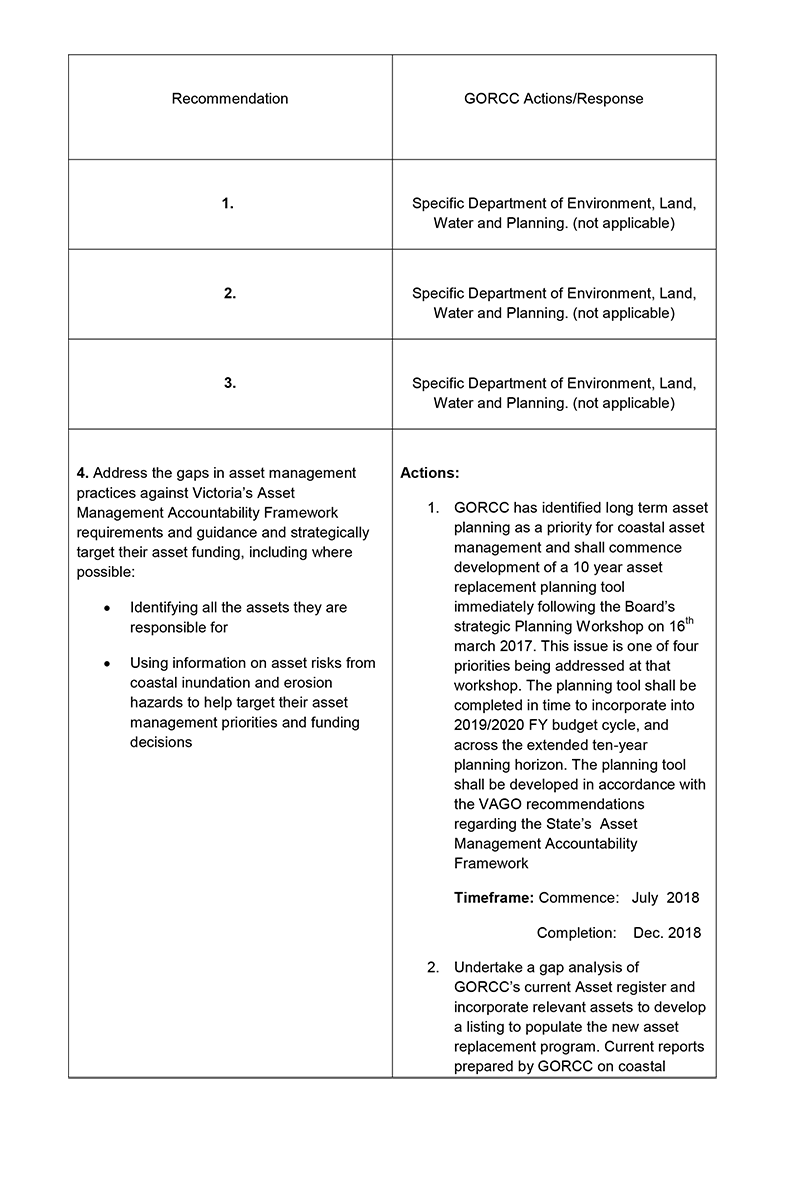

We recommend that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

1. improve its knowledge of coastal hazards and its oversight of coastal asset management across the state by:

- compiling and maintaining a statewide inventory of state, regional and locally significant coastal assets on Crown land and their condition using consistent ratings (see Section 2.2)

- supporting and overseeing committees of management to align their asset management practices with key elements of Victoria's Asset Management Accountability Framework and their risk management practices with AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009 Risk management—Principles and guidelines (see Sections 2.2 and 2.3)

- addressing gaps in coastal hazard data and knowledge of risks to coastal assets across the state, and communicating this information and any tools developed to coastal managers to help them guide local risk‑based asset management (see Section 2.3)

2. strengthen oversight of Victoria's coastal managers, by extending and adequately resourcing its oversight role to cover the management of all public coastal areas and:

- clarifying the coastal asset management roles and responsibilities of the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, and committees of management under the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978, the functions and the performance measures they will be held accountable for, and holding them accountable (see Section 5.3)

- providing guidance to support coastal managers' decisions about where and when it is appropriate to use different climate change response options—protect, adapt, relocate or decide not to renew assets—and additional support on coastal hazard and risk assessment to those managers with limited capability and/or resources (see Sections 2.3 and 3.3)

3. develop a sustainable funding model to guide the effective resourcing of coastal managers, including:

- developing a coast-wide understanding of the cost and skills required to manage and maintain significant coastal assets to the levels of service needed to support their function (see Section 5.3)

- appointing the most appropriate skilled and resourced coastal manager under the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978 based on this understanding (see Section 4.2)

- implementing the coastal accounting framework once developed and requiring coastal committees of management to adhere to it (see Section 4.3).

We recommend that the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, East Gippsland Shire Council, Gippsland Ports, Great Ocean Road Coast Committee, Mornington Peninsula Shire Council, Parks Victoria and VicRoads:

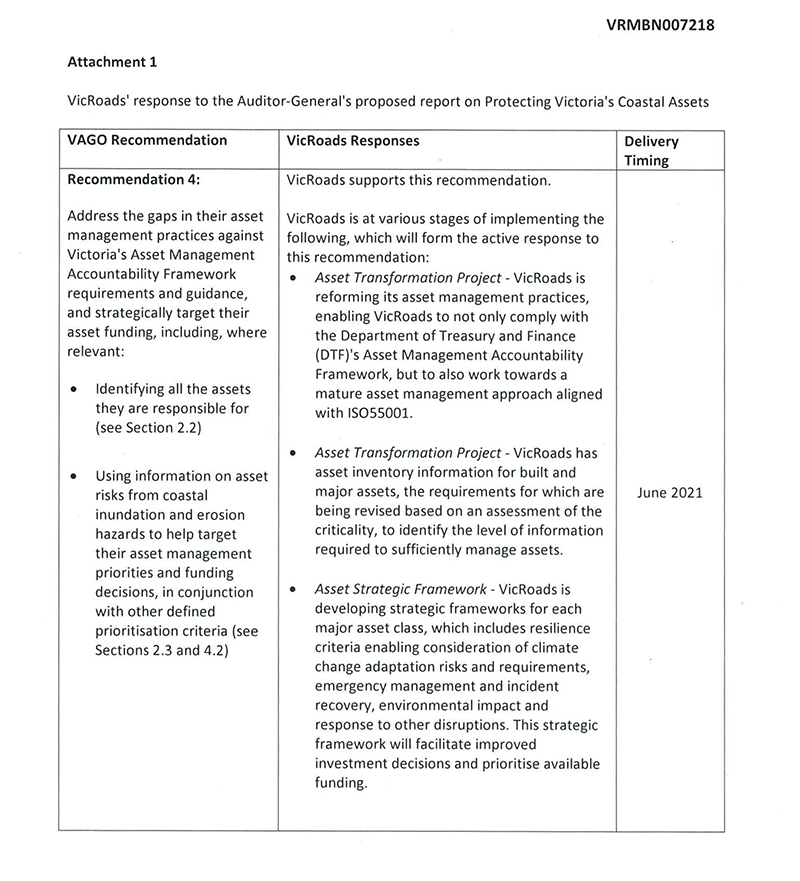

4. address the gaps in their asset management practices against Victoria's Asset Management Accountability Framework requirements and guidance and strategically target their asset funding, including, where relevant:

- identifying all the assets they are responsible for (see Section 2.2)

- using information on asset risks from coastal inundation and erosion hazards to help target their asset management priorities and funding decisions, in conjunction with other defined prioritisation criteria (see Sections 2.3 and 4.2)

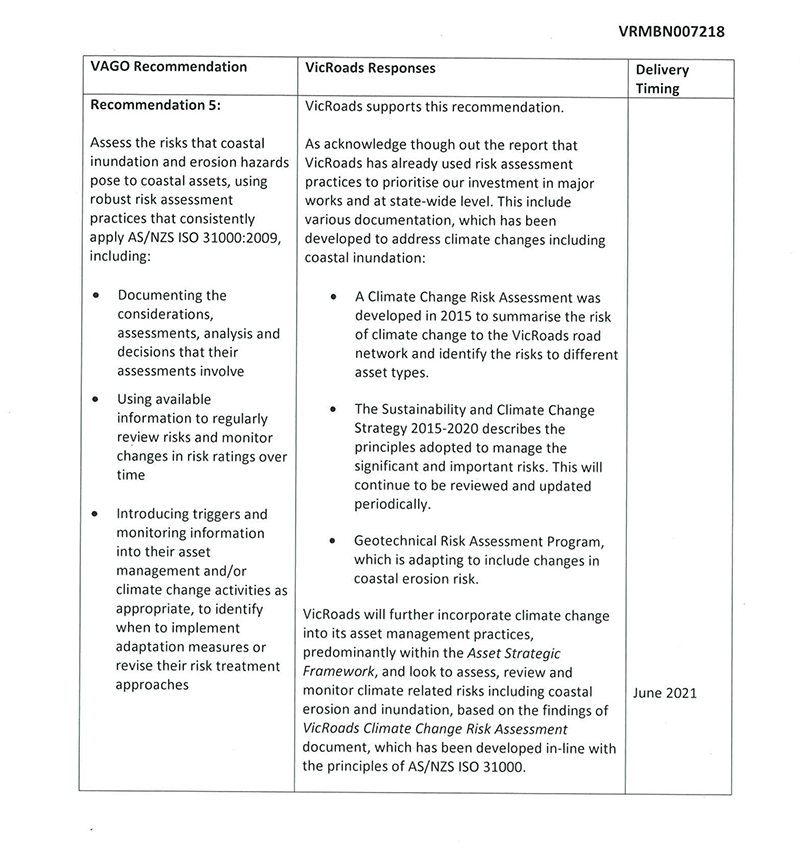

5. assess the risks that coastal inundation and erosion hazards pose to coastal assets, using robust risk assessment practices that consistently apply AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009, including:

- documenting the considerations, assessments, analysis and decisions that their assessments involve (see Section 2.3)

- using available information to regularly review risks and monitor changes in risk ratings over time (see Section 2.3)

- introducing triggers and monitoring information into their asset management and/or climate change activities as appropriate, to identify when to implement adaptation measures or revise their risk treatment approaches (see Section 3.3).

We recommend that the East Gippsland Shire Council, Gippsland Ports and Mornington Peninsula Shire Council:

6. assess climate change risks from coastal inundation and erosion hazards across their coastal asset portfolios (see Section 3.2).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DELWP, PV, MPSC, EGSC, GP, GORCC and VicRoads, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 , we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

The agencies welcomed the report's findings and accepted all recommendations to improve their management of coastal assets.

EGSC outlined its response to the recommendations and the remaining six agencies all provided an action plan for how they will implement the recommendations relevant to them.

1 Audit context

1.1 Victoria's coastal assets

Most Victorians live, work and play close to the coast. It is home to over one million people—19 per cent of the state's population—and four out of five Victorians visit the coast every year to enjoy a wide variety of recreational pursuits. The coast is also the destination for a growing domestic, national and international tourist market.

In 2016, Tourism Australia, working closely with Tourism Victoria, launched its $40 million global campaign focusing on one of Australia's key competitive advantages—our world-class aquatic and coastal experiences—to attract more international visitors. Its research showed that 70 per cent of overseas tourists visited the coast. In 2015–16, tourism along the Great Ocean Road and the Mornington Peninsula reportedly generated $795 million and $700 million for Victoria's economy respectively.

Natural and built assets on the coast can provide valuable protection for other coastal assets―such as jetties, boat ramps, coastal parks, stairs and viewing platforms—which provide important economic, recreational and environmental services and functions. There is also critical infrastructure along the coast―including telecommunications, drainage and sewerage networks, roads and housing—which requires protection. When intact, protective assets―including seawalls, groynes, beaches and mangroves―act as an effective barrier against coastal processes such as inundation and erosion.

These protective assets, while vitally important now, will be even more so in the future when the predicted effects of climate change exacerbate coastal hazards.

In 2011, the National Climate Change Adaptation Research Facility (NCCARF) estimated the total economic value of Victoria's coastal assets, including both natural and built assets, at $18.3 billion annually. In 2013, the Victorian Coastal Council (VCC) estimated that it would cost $24–$56 million annually to replace the natural protection offered by coastal assets like beaches and dunes.

Figure 1A identifies the coastal assets that were the focus of this audit.

Figure 1A

Natural and built coastal asset categories

|

Asset category |

Asset type |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Built assets |

Protective assets |

Sea walls Groynes Rock revetments |

|

Maritime assets |

Piers and jetties Local ports Water access points—including boat ramps, slipways and rowing launches Safety navigation aids |

|

|

Access assets |

Stairs Boardwalks Viewing platforms |

|

|

Natural assets |

Protective assets |

Beaches Mangroves Wetlands Salt marshes Sea grasses Coastal dune systems |

|

Ecosystem assets |

Cliffs Coastal parks and reserves Significant flora and fauna Biodiversity Beaches |

Source: VAGO based on data supplied by audited agencies.

1.2 Asset Management Accountability Framework

The AMAF governs asset management in Victoria. It requires a risk-based whole‑of-life-cycle approach to asset management, including maintenance and the eventual removal or replacement of an asset. It details mandatory asset management and information requirements, as well as general guidance for agencies responsible for managing both built and natural assets. The AMAF is supported by Implementation Guidance released in 2017, which provides a benchmark for better practice asset management, including examples for agencies with smaller, narrower asset portfolios as well as for those with large, complex portfolios.

We assessed the audited agencies' practices against the key steps in the AMAF guidance.

1.3 Managing risks to coastal assets

What coastal assets are at risk?

The 2012 Victorian Coastal Hazard Guide defines coastal hazards as natural coastal processes—such as tides, currents, winds, waves and rainfall—that are likely to have an adverse effect on life, property or aspects of the natural environment.

Coastal assets are at increasing risk from coastal hazards, including inundation and erosion. NCCARF predicts these impacts will worsen and accelerate due to climate change. In 2011, NCCARF estimated that sea levels in Victoria will rise by 0.8 metres by 2100, significantly increasing impacts on coastal assets, as outlined in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Assets at risk of inundation based on a 0.8-metre sea level rise by 2100

|

Asset |

Quantity |

Value |

|---|---|---|

|

Built assets |

||

|

Residential buildings |

31 000–48 000 |

$6.5 to $10.3 billion |

|

Commercial buildings |

Up to 2 000 |

$12 million |

|

Roads |

527 km |

$9.8 million |

|

Railways |

125 km |

$500 million |

|

Government-owned public facilities |

87 |

Not known |

|

Maritime assets |

Not known |

$220 million |

|

Coastal protection structures |

Over 1 000 |

$700 million |

|

Natural assets |

||

|

Public land |

586 km |

Not known |

|

National and state coastal parks |

15 |

Not known |

|

Vegetation |

48 720 hectares supporting 95 ecological vegetation classes |

Not known |

|

Mangroves |

6 300 hectares |

Not known |

|

Wildlife reserves |

14 |

Not known |

|

Nature conservation reserves |

9 |

Not known |

|

Flora and fauna reserves |

4 |

Not known |

|

Rare or threatened species |

880 |

Not known |

Note: This table does not include costs associated with impacts on maritime assets and loss of revenue for other activities that rely on coastal assets.

Source: Built asset figures taken from 2011 NCCARF data and 2016 PV data. Natural asset figures taken from 2012 Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) data, 2013 VCC data and 2016 Victorian National Parks Association data.

Assessing risks

The 2016 Victorian Government Risk Management Framework sets minimum standards for public sector risk management—including managing risks to assets—in accordance with ISO 31000, as shown in Figure 1C. While only departments and public sector bodies covered by the Financial Management Act 1994 are required to comply with this framework, it provides a suitable benchmark for all public sector agencies.

Figure 1C

Key steps to assess risk under ISO 31000

Source: NCCARF, 2011, based on ISO 31000.

Information needed to support risk assessment

|

Design life is the length of time an asset is predicted to keep functioning, based on its design. |

To assess risks accurately, agencies need robust asset information, including:

- the number and types of assets

- asset value, design life and condition

- the service or function that the asset provides

- data about usage or visitation

- what assets and or infrastructure require protection.

Agencies also need information about hazards and knowledge of variations in shoreline characteristics and coastal processes at state, regional and local levels.

NCCARF recommends that the states and their agencies systematically assess coastal hazards, starting at the national scale and working through progressive levels of detail to the regional and local level. Information gathered using this process can inform risk assessments.

Responding to coastal asset risks

Once agencies collect information on the current state of assets and risks facing them, they can evaluate potential risk treatments to identify the most effective and cost-efficient response. These treatments may include:

- protecting assets—maintaining the existing coastal environment and infrastructure, which includes the use of coastal protection structures

- adapting/accommodating assets—managing potential impacts of coastal inundation and erosion through adaptive measures, such as raising floor levels in buildings

- retreating—deliberately removing or relocating high-value community and commercial built coastal assets and built coastal protection structures from expected areas of impact, and allowing nature to take its course

- doing nothing—allowing nature to take its course and accepting the cost.

Implementation of these risk treatments may be supported by:

- actions in coastal plans

- land use planning controls—incorporating planning policies and tools into state and local planning frameworks to address coastal hazards

- approvals for the use and development of coastal Crown land

- asset management practices, including capital works, replacement, renewal, restoration and maintenance works

- building coastal managers' capacity and capability through education, training, guidance and grants.

Some of these treatments aim to reduce the likelihood of impacts occurring—such as constructing or maintaining seawalls that prevent inundation—while others, like land use planning and building controls, focus on mitigating the consequences.

1.4 Governance and oversight

Legislative framework

Four primary Acts provide the legislative framework for the management and protection of assets on public lands in Victoria, including coastal areas:

- The Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978 identifies coastal Crown land reserves and their purpose (generally conservation and recreation) and establishes CoMs to manage these areas on behalf of the Crown.

- The National Parks Act 1975 establishes a system to protect coastal areas of high conservation value, including the development of management plans.

- The Land Act 1958 provides legislative and governance arrangements for unreserved Crown land.

- The Forests Act 1958 provides legislative and governance arrangements for the management of forests on Crown land.

A range of overlapping Acts that address specific public land management categories and issues support these primary Acts. Three further overlapping Acts influence coastal planning and management:

- The Coastal Management Act 1995 provides the framework for protecting Victoria's coastal assets on Crown land. This Act establishes the VCC and three regional coastal boards and requires the development of a hierarchy of coastal strategies and plans.

- The Planning and Environment Act 1987 develops the state's planning system, which governs land use and development across the coast. All planning and land use decisions under this Act must consider the Victorian Coastal Strategy. Decisions must take into account a projected sea level rise of 0.2 metres by 2040 in established areas, and 0.8 metres by 2100 in undeveloped coastal areas.

- The Port Services Act 1995 provides for the local port manager to develop and maintain port facilities, including wharves, jetties, slipways, breakwaters, moorings, buildings and vehicle parks.

Coastal policy and plans

A number of different coastal plans may apply to coastal areas, depending on the area's legislative status.

The Victorian Coastal Strategy, established under the Coastal Management Act 1995, provides the overarching strategic framework for the planning, management, and protection of coastal assets on Crown land. It establishes a hierarchy of principles, supported by policy objectives and strategic actions, to maintain and protect coastal assets. It has a strong focus on managing population growth pressures and hazards resulting from climate change.

Coastal plans developed by regional coastal boards are the key tools used to implement the principles and objectives of the Victorian Coastal Strategy across coastal Crown land. These can be either broad regional coastal plans or specific area or issue plans, known as coastal action plans.

Coastal management plans set out the local coastal management requirements and actions based on strategic directions in regional coastal plans and coastal action plans. CoMs develop coastal management plans and each must contain a three‑year business plan detailing proposed works. The Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change is required to approve these plans. In 2017, DELWP released guidelines for the development of these plans.

Assets within coastal areas protected under the National Parks Act 1975 are the responsibility of PV. PV develops a hierarchy of management plans at the landscape, regional and local levels for coastal areas requiring a higher degree of protection.

Coastal management arrangements

There are at least 63 entities responsible for managing and protecting Victoria's coastal assets. Along some areas of the coast, multiple coastal managers form a patchwork of relatively small areas of responsibility, particularly around the Port Phillip Bay and Western Port coastline—the central region—as shown in Figure 1D.

More than two-thirds of public coastal land is national park, coastal park, marine national park or marine sanctuary. PV maintains and protects the natural and built assets in these protected areas under the National Parks Act 1975. Assets in these areas include high-value natural coastal ecosystems, access assets—such as boardwalks, viewing platforms, stairs and tracks—and maritime assets. Local port managers, including PV and GP, manage maritime assets.

Most of the remaining public coastal land above the high-water mark is Crown land under the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978. DELWP delegates the management of most of this land to CoMs. The Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change appoints agencies or individuals to committees under the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978. A coastal CoM may be a local council, PV, a local port manager, large skilled committees or smaller volunteer committees.

Figure 1D

Management arrangements around the Port Phillip Bay and Western Port coastline

Source: DELWP.

The role of a CoM is to 'manage, improve, maintain and control' Crown land reserves for the purposes for which they are reserved under the Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978. Assets managed by CoMs include both land-based and water-based natural and built coastal assets.

DELWP classifies large skilled and smaller volunteer CoMs into two categories depending on their annual financial return:

- CoMs that generate more than $1 million in revenue annually are classified as 'category 1'—there are currently five across the coast[1]

- CoMs that generate less than $1 million annually are classified as 'category2'—there are currently 19 across the coast.

Some small areas of public Crown land are 'unreserved' and fall under the control of the Land Act 1958 . DELWP manages these areas directly.

DELWP's role

DELWP is responsible for overseeing the management of Crown land on behalf of the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change. In this role, it oversees the performance of coastal protection assets on Crown land—including groynes, seawalls, rock revetments and beaches—for both their community and amenity value and their role in protecting other coastal assets and infrastructure. DELWP also oversees the performance of CoMs, to which the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change delegates much of the day-to-day management of Crown land. In this role, DELWP:

- recommends appointments to CoMs for ministerial approval

- produces guidelines that outline CoMs' responsibilities and provides support to implement them

- supports the development of coastal management plans by CoMs and recommends their approval by the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change

- requires CoMs to submit annual financial returns.

1.5 Reform of public land management

Reviews since the mid-2000s have called for the overhaul of the legislative framework for managing public land—which includes 96 per cent of coastal areas—to simplify, update and better integrate its planning and management.

Multiple reviews by DELWP, ministerial advisory committees and others have identified issues specific to the effective management and protection of coastal assets. These include:

- outdated legislation

- overly complex governance and management arrangements

- poor accountability and implementation of actions identified in coastal strategies and plans

- poorly resourced and skilled coastal managers

- unclear roles and responsibilities for managing coastal assets

- lack of transparency of generated coastal revenue and expenditure, including how revenue expenditure is prioritised to address risks to coastal assets

- the absence of a uniform system to support decision-making to manage the many competing priorities and demands across the coast

- poor collation and storage of coastal knowledge.

Between 2015 and 2016, the Victorian Government instigated a range of reviews into public land management, including coastal areas. In 2015, the government committed to a package of reforms including a new legislative framework, policy reforms and improved coastal and marine management arrangements. Figure 1E outlines the drivers that underpin the government's proposed reforms.

Figure 1E

Drivers of the Victorian Government's proposed coastal reforms

Source: DELWP, Marine and Coastal Act Consultation Paper, 2016.

In 2016, government asked the Victorian Environment Assessment Council to review public land management, including coastal areas. It made 30 recommendations, all of which government accepted, in full, in part or in principle, in 2017. In particular, it agreed to develop a new public land Act within five years to replace the current Land Act 1958, Crown Land (Reserves) Act 1978 and Forests Act 1958 .

1.6 Why this audit is important

Victoria's coastline is one of the state's major assets. The coast and its built and natural assets are under increasing pressure from population growth and climate change.

Threats to natural and built assets affect the commercial, recreational and environmental services they directly provide or support. It has been estimated that, in Victoria, a 0.8-metre sea level rise by 2100 will put $18.3 billion worth of coastal infrastructure and assets at risk of inundation and erosion. The costs of these impacts on ecosystem services provided by natural assets have not been quantified, but would be significant.

Given the value of Victoria's coastal assets and the significant threats they face from current and future coastal hazards, it is important that they are adequately protected.

The government, through DELWP, is currently implementing a range of reforms to improve the legislative framework, governance, planning and management arrangements for the coast. This audit helps to assess and further inform these reforms.

1.7 What this audit examined and how

This audit aimed to determine whether natural and built assets on Victoria's coastline are adequately protected against inundation and erosion. We focused on:

- coastal protection structures

- built structures—such as seawalls, groynes, breakwaters and rock revetments

- natural structures—including beaches, dunes, mangroves and reefs

- maritime assets—water-based assets with a commercial, recreational or access function, such as wharves, jetties, piers and boat ramps

- access assets—land-based assets that support access and recreation, such as stairs and boardwalks

- natural assets—including beaches, public land, biodiversity, cliffs and coastal parks.

We examined the adequacy of individual agencies' asset and risk management approaches, funding for assets at risk and statewide coordination of coastal asset protection.

We audited seven agencies responsible for protecting coastal assets—DELWP, PV, MPSC, EGSC, GP, GORCC and VicRoads. These agencies are of varying sizes and manage a range of significant coastal assets, coastline areas and risks. A summary of their responsibilities for coastal asset protection, funding and expenditure, as well as our expectations for their asset and risk management practices, is included in Appendix B.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $640 000.

1.8 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 discusses how agencies manage coastal assets in their local areas and current risks posed by coastal inundation and erosion

- Part 3 discusses how agencies manage future risks to coastal assets that may result from climate change

- Part 4 examines funding and how it is prioritised

- Part 5 discusses statewide oversight and support for the protection of coastal assets.

[1] One of the category 1 CoMs is a trust, which we did not include in this audit.

2 Local management of coastal assets

Asset management aims to optimise the life span of assets and the services that they provide, for minimum cost. Risk management is an integral part of good asset management. It helps asset managers to identify high-value assets and prioritise and manage threats to them.

In this part of the report, we analyse agencies' knowledge of their coastal assets and how they prioritise, manage and protect them.

2.1 Conclusion

While there is evidence of good on-ground work to manage failing assets that pose a public safety risk, key weaknesses exist in the way the audited agencies identify, assess and manage their coastal assets. In addition to these weaknesses, agencies do not use a risk-based approach to target their efforts and resources to high-value, high-risk assets.

This means they are not effectively protecting assets from coastal hazards. Agencies are not balancing their response to damaged and failing assets with strategic maintenance to optimise the life of their assets.

Fundamental gaps in asset and coastal hazard information, and a reliance on staff experience and knowledge rather than good asset management systems, further limit agencies' ability to be effective risk-based asset managers.

Two of the seven audited agencies have a better approach to managing their coastal assets than the others, but they could still improve their systems or make better use of them. The other five agencies lack practices that are fundamental to good asset management and are not making the best use of the systems they have.

Common weaknesses include:

- an incomplete inventory of coastal assets and the other infrastructure and values that are being protected by coastal protection assets

- poor asset condition information

- an inability to share information about assets between agencies and statewide

- an overriding 'fix on fail' approach at the expense of preventative routine maintenance to keep assets functioning as needed, for longer.

Funding and resource constraints influence the audited agencies' ability to rectify a number of these problems.

2.2 Coastal assets and their management

Asset management approaches

We assessed agencies' asset management approaches and practices against key elements of the Department of Treasury and Finance's AMAF and its Implementation Guidance.

Figure 2A lists the critical elements from the AMAF that we assessed as necessary for effective asset management, and the extent to which the audited agencies have them in place for their coastal assets. Most agencies have key elements of a good framework and practices, but there are also many gaps.

Figure 2A

Alignment of agency asset management frameworks and coastal asset management practices with key elements of the AMAF guidance

|

Asset management element |

DELWP |

PV |

MPSC |

EGSC |

GP |

GORCC |

VicRoads |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Asset management framework elements |

|||||||

|

Asset strategy |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

n/a(a) |

|

Asset plans (e.g., five-year plan) |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Operational plans (e.g., one-year plan) |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Asset register |

◗ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Information management system |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

◗ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Asset management practices |

|||||||

|

Defined levels of service |

✘ |

✔ |

◗ |

✘ |

◗ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Disposal process |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Major event (storm, flood) triggers inspection |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Trigger for expert assessment |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

Key: ✘yes; ✔no; ◗ partly.

(a) Transport for Victoria is responsible for developing the asset strategy VicRoads will use.

Source: VAGO.

We identified some common reasons for agencies' weak coastal asset management:

- coastal assets are not a key focus for agencies with a broad range of responsibilities and assets

- agencies' limited knowledge about existing coastal processes and their uncertainty about the impact of future climate change reduce their ability or confidence to act

- agencies lack guidance about how to identify high-value coastal assets—those of local, regional or state significance

- some agencies do not recognise the need to manage assets strategically and, for some that do, it is not supported or driven across their operations.

As smaller agencies, GP and GORCC have fewer assets overall, allowing them to more easily identify and manage their coastal assets, even though their systems and documentation are limited. In contrast, the larger agencies have many inland assets as well, which means they give less attention to the proportionally small number of coastal assets that they are responsible for.

The two audited councils—EGSC and MPSC—have a broad asset base, and their management priorities focus on assets such as roads and bridges. The councils advised us that they use a more mature asset management approach for their major asset classes, but their approach for managing coastal assets did not demonstrate the same maturity—because coastal assets are not a priority based on the funding and staff resources available. EGSC also advised that it has to prioritise its asset management effort because it has low revenue relative to the size of its asset portfolio.

Knowledge of assets and their condition

The asset inventories that individual agencies keep do not record all coastal assets in Victoria. Only two of the audited agencies have reviewed their asset inventories to make sure they have identified all of their coastal assets. None of the agencies consistently collects all of the information needed to manage their assets effectively.

Built assets

There are thousands of built coastal assets across the state but no comprehensive central or interoperable register of them. There are several issues among the audited agencies:

- VicRoads and MPSC are the only agencies that have undertaken a 'stocktake' of the built assets within their management areas.

- MPSC's 2015 stocktake identified over 1 200 built assets not recorded in either its own asset information system or DELWP's. Many of these were minor assets—such as fences and bollards—but they also included boat ramps, seawalls and jetties. MPSC recorded these on its asset register in 2015, where it has noted that the responsibility for them is 'to be advised', pending resolution of responsibilities with DELWP.

- DELWP has recently identified other built coastal protection assets that it has not recorded previously around the open coast, as its focus has been on the main bays and town areas.

Figure 2B gives examples of the quantity and type of built assets within the audited agencies' portfolios.

Figure 2B

Examples of coastal assets managed by the audited agencies

|

Agency |

Asset type |

Quantity |

Age range |

Proportion in poor condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

DELWP |

Seawalls, groynes and other protection assets |

Over 1 000 |

1920s to present 33% with less than 10 years remaining in its useful life |

Not known |

|

PV |

Piers, jetties, boat ramps and associated structures |

193 |

1957 to present 53% with less than 10 years remaining in its useful life |

22% |

|

MPSC |

Seawalls, groynes, jetties, boat ramps |

54 |

1940 to present |

22% |

|

EGSC |

Seawalls and marinas |

81 |

Not known |

30% |

|

GP |

Wharves, jetties, boat harbours |

97 |

1937 to present |

Not known |

Note: Agencies may identify assets in different ways—for example, one agency might count a jetty and the landing platform attached to it as one asset, while another agency might count it as two assets.

Source: VAGO based on agency data.

No audited agency keeps information on the coastal infrastructure or natural values protected by its groynes, seawalls, rock revetments, beaches or dune systems. This information is critical to determine the need for a coastal protection structure and the level of service it should deliver—important parts of risk-based asset management and prioritising works and funding.

DELWP is developing a new asset inspection tool that will enable it to capture this type of information, but other audited agencies are not doing this and are unaware of DELWP's tool.

Other important asset information that agencies are not recording consistently includes asset condition, usage or visitation data, design life and expected remaining life, and life cycle cost.

Natural assets

Agencies with responsibility for protecting both built and natural assets have a stronger focus on their built assets. All the audited agencies, except VicRoads, have done some work to value their natural coastal assets, however information about these assets is sparse.

We identified a number of reasons for this unbalanced focus:

- Accounting systems for natural assets are not as mature as those for built assets, and government asset guidelines are less explicit, making it difficult for agencies to comprehensively value these assets.

- Built assets are more readily managed through established corporate asset systems.

- In many cases, built assets pose greater safety risks to the public, with the exception of unstable cliffs.

DELWP and PV engaged consultants in 2011 and 2013 to improve their valuation of natural assets and develop an accounting framework. Recommendations arising from this work have not progressed. The agencies cite limited funding and other priorities as the cause for this.

PV manages approximately 70 per cent of Victoria's public coastal land. The National Parks Act 1975 protects most of this land , as the ecosystems in these areas have high conservation values. PV collects information on natural assets and data on visitors and their experiences in its parks, but it is yet to do this for the majority of coastal areas. Its new approach to planning for its parks including coastal areas aims to improve information collection on natural assets across the state. To date, its ability to apply this planning approach to coastal areas has been limited by a lack of resources.

As a result, information on natural coastal assets is either lacking or outdated. PV does not routinely collect new data across the coast, instead collecting it only for priority areas or issues, because of staffing and funding constraints.

Asset condition

|

Information on asset condition helps agencies understand:

|

The audited agencies could not provide comprehensive information on the condition of their coastal assets, and there is no oversight of information collected on asset condition across the agencies and the coast. Available information suggests 22 to 30 per cent of assets are in poor condition, as shown in Figure 2B, but the accuracy of this estimate is questionable.

With the exception of PV and MPSC, the audited agencies usually only conduct comprehensive technical inspections on assets that are failing or are in poor condition. Funding is a barrier to the more widespread use of technical inspections by the audited agencies due to their high cost. This means while they cannot be done as frequently as required, they need to be carefully targeted at high-value, high-risk assets. Such detailed inspections are needed to meet the AMAF requirements for particular assets.

Standard inspections, when undertaken, are often basic visual checks and only collect information on asset condition, rather than on an asset's performance in providing the required level of service or protection. Agencies do not routinely assess the impacts of coastal processes and hazards on assets. Without this information, agencies cannot accurately track asset condition over time to determine when maintenance, renewal or replacement works are required, which could prevent deterioration of the asset―and for protective structures, of any assets they are shielding. Figure 2C highlights the risks of not assessing condition adequately and regularly.

Many staff from the audited agencies lack appropriate training to undertake more complex and technical asset assessments, and some agencies' guidance to support consistent inspections is limited.

There is little evidence of audited agencies using standardised condition ratings or descriptions of asset condition. GP and GORCC use different condition rating systems for assets and do not use standardised condition descriptions.

PV, MPSC, VicRoads and GP have established processes to identify, inspect, monitor, assess and record information on the condition and status of their built coastal assets. Only PV has documentation to show that it regularly applies these processes to coastal assets.

DELWP and PV are developing electronic field tools to improve the quality and consistency of their asset inspections and the data they collect. DELWP is also developing new guidance for its staff to ensure a consistent standard of visual inspections and reduce assessor subjectivity. This guidance has been validated against standard coastal engineering principles and practice.

Figure 2C

Case study: Lakes Entrance training walls and seawalls

|

Access from the Gippsland Lakes to Bass Strait at Lakes Entrance was established in 1872 by constructing 'training' walls. Seawalls were also built around this time to help protect the coastal township area. There has been little major work on the training walls since they were last extended in 1934, or on the seawalls. Lakes Entrance has significant local, regional and state value for residents and visitors. It is also home to Victoria's largest commercial fishing fleet. The GP is responsible for the training walls and it regularly conducts land-based visual inspections and undertakes minor maintenance. DELWP also periodically assesses the condition of the training walls. However, the training walls have not had any underwater technical inspections in the last decade. DELWP is also responsible for most of the seawalls but it has not maintained or replaced them and, prior to 2016, it had not conducted detailed technical inspections of them. DELWP's 2011 visual inspection of the training walls identified that the concrete head wall was deteriorating while, in other areas, the rock protection had slipped, exposing the old timber structure. DELWP rated these issues as a medium priority and estimated that works to address them would cost $460 000, but it has not planned any works to date. GP's 2017–18 business plan noted continuing concern about the condition of the training walls, concluding that a partial wall failure could occur at any time. |

|

Below: A hole in the path reveals a void behind the seawall where the bank has been eroded by water entering through gaps in the mortar. The wall's foundations have been undermined and the adjacent stormwater system (in the foreground) has failed. |

|

DELWP's 2016 seawall inspection program identified several sections of wall in poor condition and the need for $6.6 million worth of emergency stabilisation works at a number of sites, along with $40−$60 million in the long term to rebuild key walls. EGSC has estimated that replacing the three highest-priority seawall sections will cost $14−$25 million. Thorough, periodic technical inspections of the training walls and seawalls would have identified the deteriorating condition of these assets earlier, enabling more timely works to extend the assets' life and reducing the cost of works needed in the longer term. |

Source: VAGO, with pictures provided by DELWP.

Asset services

Each asset provides a service or function, such as protection, community use and environmental or social value. Understanding an asset's level of service and function is important for determining its value and its priority for protection. For example, a boat ramp may not have high use, but if there are no other suitably sheltered spots for launching a boat within several kilometres, the level of service required from that ramp may be higher than for ramps in other locations where there are a number of them. Defining levels of service helps agencies to better target their resources to conduct inspections, maintenance and major works.

Only PV and MPSC adequately define the level of service required or expected from their built and natural coastal assets.

Asset information management systems

We found significant issues with coastal asset data storage, use and sharing across the audited agencies. These issues in data storage:

- impair the state's and agencies' ability to compare and assess assets and their relative condition across the coast to target funding to those of highest value and at highest risk

- result in gaps in asset identification and maintenance responsibilities

- duplicate effort

- impede integrated and consistent management of assets across the Victorian coast.

| The AMAF guidelines recommend agencies store asset information in an information management system to ensure the information is collated, structured, reliable and easily accessed. It should be fit for purpose—that is, appropriate to the nature and scale of the agency's responsibilities and assets. |

Except for DELWP and GORCC, the audited agencies have information systems to manage their coastal asset data, although they each use different systems. While these systems are largely fit for purpose, they do not address key elements of the AMAF. Information is often stored across a number of databases or spreadsheets that are not linked and searchable, and agencies do not use them to interrogate the data or use the collected information to inform their asset management practices and decisions.

DELWP has introduced two asset information systems in recent years, but these were poorly implemented and not well used, as neither was fit for purpose or user friendly.

PV, DELWP and MPSC are in the process of introducing new asset information systems, which they advise will incorporate their coastal assets. DELWP anticipates that its proposed new asset information management system, due to be implemented in 2018, will be interoperable with some local government asset systems, which will go part way to addressing this issue.

Asset maintenance and disposal