WoVG Information Security Management Framework

Overview

The audit examined 11 public sector agencies and found that the policy, standards and protection mechanisms for the security of the state’s information and communications technology (ICT) systems and data have not been effectively applied. Agencies undertake only limited monitoring of suspicious internal network activity, and they do not have a capability to detect an intrusion into sensitive public sector systems.

The audit also found that if there was an external cyber attack or a cyber alert issued by an Australian Government national security agency, there would be no coordinated understanding of the threat or its impact across the state’s public sector ICT systems, because central agencies do not conduct follow up actions after a cyber alert is disseminated.

The audit further identified a number of critical- and medium-level risks related to individual agency systems that have been raised with each of those agencies through individual management letters. Agreement has been reached with each agency about what actions will be implemented and a proposed time frame for implementation.

WoVG Information Security Management Framework: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2013

PP No 281, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report WoVG Information Security Management Framework.

The audit examined 11 public sector agencies and found that the policy, standards and protection mechanisms for the security of the state's information and communications technology (ICT) systems and data have not been effectively applied. Agencies undertake only limited monitoring of suspicious internal network activity, and they do not have a capability to detect an intrusion into sensitive public sector systems.

I also found that if there was an external cyber attack or a cyber alert issued by an Australian Government national security agency, there would be no coordinated understanding of the threat or its impact across the state's public sector ICT systems, because central agencies do not conduct follow-up actions after a cyber alert is disseminated.

During the course of this audit, I identified a number of critical- and medium-level risks related to individual agency systems that I have raised with each of those agencies through individual management letters. I have reached agreement with each agency about what actions will be implemented and a proposed time frame for implementation.

Given the ongoing implications of these issues for ICT security, I intend to closely monitor the completion of these actions and may report their status to Parliament at a later date.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle Auditor-General

27 November 2013

Audit summary

Background

Information security is critical to ensure the confidentiality, integrity and availability of public sector data, information and services.

Security risks for information and communications technology (ICT) systems have significantly increased in recent years. Around the world, there have been unprecedented and escalating external threats to information security for both public and private sector ICT systems, commonly referred to as cyber threats.

This audit focused on whether information security policy and standards have been appropriately implemented across Whole-of-Victorian-Government (WoVG) agencies and whether systems are capable of resisting cyber attacks and protecting public sector information in a hostile environment.

Currently, the published information security policy and framework applies only to 20 Victorian Government agencies, referred to in this report as 'inner WoVG agencies'. There is no requirement for any 'outer WoVG agency' to conform to any specific policy or standard.

To assess the effectiveness of the state's ICT security policy, standards and protection mechanisms, this audit examined whether:

- appropriate information security policy direction and guidance was in place to provide consistent protection to state ICT systems and data

- central agencies had oversight of, and coordinated responses to, information and system threats

- selected agencies had established and complied with information security policy and standards.

VAGO appointed an independent specialist information security advisor to assist in reviewing whether the information security policy, standards and processes that agencies have in place comply with mandated government standards.

Under VAGO's supervision, the specialist information security advisor also conducted internal and external penetration testing—a method of testing for vulnerabilities within an ICT system—of selected agency ICT systems.

This audit examined 11 agencies:

- Seven agencies were inner WoVG agencies, defined in the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) information security procedures as 'WoVG'.

- Four agencies were outer WoVG agencies, defined in DSDBI's information security procedures as 'non-WoVG'.

Conclusions

Agencies have not effectively implemented Victorian Government information security policy and standards. Agencies are potentially exposed to cyber attacks, primarily because of inadequate ICT security controls and immature operational processes.

The current information security policy has not been endorsed by government and there are no current arrangements to brief ministers if a major cyber threat affects the public sector's ability to deliver services. This position may be addressed by the Emergency Management Bill 2013 which was introduced into Parliament on 31 October 2013.

The application and coverage of the government's information security policy and standards should be reviewed. While the content of the mandated information security procedures is appropriate, it applies only to inner WoVG agencies. The remaining outer WoVG agencies—of which there are more than 500—are not required to conform to any specific policy or standard. Four of the outer WoVG agencies reviewed as part of this audit are responsible for significant sources of state revenue, and control billions of dollars of financial assets, yet are not covered by the policy and standards.

The lack of any specific information security guidance for outer WoVG agencies conflicts with recommendations made by VAGO in our 2009 audit, Maintaining the Integrity and Confidentiality of Personal Information. This is despite the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) accepting those recommendations.

Government relies on central agencies to provide it with appropriate and timely information about the status of cyber threats and the ability of systems to resist cyber attack. However, in Victoria there is no central coordination or reporting in place.

In particular:

- DPC has no role in coordinating a whole-of-government approach to cyber threats, as this is the responsibility of individual departments and agencies

- agencies experiencing serious cyber incidents report these to the Australian Signals Directorate but not to DSDBI or DPC

- central agencies do not seek to be informed of external cyber incidents detected by Australian Government security agencies and do not follow up actions taken after a cyber alert is disseminated.

DSDBI and individual agencies are not managing internet protocol (IP) information to make sure correct and current information is available to help cyber threat response.

All the audited agencies had previously conducted penetration testing on their ICT systems. Some of these tests were too narrowly scoped and there were multiple instances where previously identified problems were not being remediated.

Overall, agencies had a low level of awareness of how their ICT systems would be likely to perform if subjected to a cyber attack.

Findings

Agencies to which the information security policy applies

While the content of the information security policy and standards is appropriate, it only applies to the 20 inner WoVG agencies. Information security policy and standards should also apply to outer WoVG agencies operating ICT systems that have an aggregate high transactional value critical to state revenue, systems critical to public safety, or systems holding sensitive personal data with potential value to third parties.

The lack of any specific information security guidance for outer WoVG agencies conflicts with the recommendations made in the 2009 VAGO report, Maintaining the Integrity and Confidentiality of Personal Information. These were accepted by DTF and DPC, but have not been fully implemented.

Victoria's public sector information security framework

Recommendations in VAGO's 2009 audit report were the impetus for developing a suite of Victorian information security policy and standards. These were informed by existing Australian Government information security standards.

The Victorian policy and standards were developed by DTF and released in late 2012.

The standards require inner WoVG agencies to develop their own information security management framework (ISMF), which is to be based on the policy and standards. This includes annual reporting requirements on the status of information security within the agency, and an assessment of its ability to withstand a cyber attack.

Individual agency ISMFs were reasonably well developed for inner WoVG agencies, but their annual reports were unsatisfactory and did not reflect a credible and realistic threat, partly because the report template was not exhaustive.

Compliance with standards

Central agencies do not provide any guidance to assist outer WoVG agencies and these agencies are therefore less advanced with their information security policies and frameworks.

Only one of the four outer WoVG agencies selected for this audit had considered existing government policy and standards. However, all had considered the ISO 27000 series of international information security standards as a reference when developing their respective information security policies.

Although DTF was required to oversee agency implementation of each agency's ISMF, we found little evidence of any oversight of agency standards, controls or compliance.

Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions

The Victorian Government's information security standards require inner WoVG agencies to implement the Australian Signals Directorate's Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions, which are likely to prevent at least 85 per cent of attacks.

We found that all four strategies were poorly implemented within both the inner and outer WoVG agencies examined.

All agencies had undertaken penetration testing of their ICT systems but there was little evidence that they tested all of their systems and there were multiple instances of testing being too narrowly scoped. Most commonly, agencies did not maintain software patches adequately and continued to operate unsupported and therefore vulnerable systems.

No coordinated view of cyber threats

We found that there is no central view of the overall Victorian cyber threat situation nor are there arrangements in place to brief government in the event of a multi-agency or sustained cyber attack.

Previously DPC advised that it did not have a role in coordinating a whole‑of‑government approach to cyber threats and that individual agencies are responsible for their own information security arrangements. However, DPC has subsequently advised that this will change with the Emergency Management Bill 2013 which was introduced into Parliament on 31 October 2013. The Bill confirms the establishment of the State Crisis and Resilience Council (SCRC) which was formed in April 2013 in anticipation of the Bill passing. Membership of the SCRC comprises all departmental secretaries and is chaired by the Secretary of the Department of Premier and Cabinet. Briefings on cyber threats will be made to the SCRC by DSDBI and the SCRC will in turn recommend briefings for ministers as appropriate.

Overall, awareness of how ICT systems would perform while under cyber attack was unsatisfactory.

Closer central agency involvement is critical to managing this gap until public sector agencies have achieved an acceptable level of maturity in ICT processes.

Recommendations

Many of the detailed findings arising from fieldwork for this audit are sensitive to the security of public sector ICT systems and it is therefore not in the public interest to include them in this report.

However, to make sure that agencies take appropriate steps to address observed weaknesses and breaches, the Auditor-General has issued management letters to each agency subject to this audit. The letters set out recommended actions and seek a response from the agencies indicating their acceptance, as well as their intended remediation actions and time frames.

This audit has identified 58 significant information security issues which are categorised as follows:

- Critical level—nine issues in three agencies—these are high-level information security risks which require an urgent assessment of the risk and implementation of mitigating controls.

- Medium level—49 issues in six agencies—these are moderate- or long-term information security risks which should be assessed and have mitigating controls implemented as soon as possible.

VAGO will periodically examine whether these findings are being remediated over an acceptable time frame and may, at its discretion, report to Parliament at a later date on progress.

Recommendations

The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:

- send the information security management policy to government for formal consideration

- amend information security policy and standards to include those outer WoVG agencies operating information and communications technology systems that have an aggregate high transaction value critical to state revenue, systems critical to public safety, or systems holding sensitive personal data with potential value to third parties

- require WoVG agencies to report any variations between the information security standards and their agency information security management frameworks, that have been approved by their agency head, as part of the annual information security management framework self‑assessment reporting process

- require that each agency information security management framework self-assessment report includes a statement of compliance addressing all self-assessment report deficiencies

- develop processes for outer WoVG agencies to be included in relevant briefings and information security forums, and to be provided with advice and assistance outside of the WoVG Chief Information Officers Council

- improve the current information security management framework self‑assessment report template to ensure a more comprehensive outcome.

Departments and agencies included in this audit should:

- take a more rigorous approach to completing their annual information security management framework self‑assessment report

- make sure their annual self-assessment reports reflect the true status and risk to agency business from any third party service provider they may use.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:

- confirm their respective roles and responsibilities for information security once the Emergency Management Bill 2013 is enacted

- confirm that briefings on cyber threats will be made to the State Crisis and Resilience Council by the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation as the agency with primary responsibility for WoVG information and communications technology, and that the State Crisis and Resilience Council will in turn recommend briefings for ministers as appropriate.

The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:

- arrange for a cyber alert subscription service to be available to every government agency from a suitable provider

- develop and implement a process for maintaining a register of all IP addresses in use by public sector departments and agencies.

Departments and agencies included in this audit should:

- implement appropriate action to maintain the accuracy of their IP address information with the Asia‑Pacific National Internet Centre.

All public sector agencies in Victoria should:

- review the Australian Signals Directorate Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions, and implement these practices as a matter of urgency

- retain responsibility for managing and allocating passwords if third party service providers are used

- review the patching guidelines published on the Australian Signals Directorate’s website and develop, implement or review their patching strategy.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report was provided to the following departments and agencies with a request for submissions or comments:

- CenITex

- Department of Human Services

- Department of Justice

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Department of State Development, Business and Innovation

- Department of Treasury and Finance

- State Revenue Office

- Transport Accident Commission

- Treasury Corporation of Victoria

- Victorian Funds Management Corporation

- WorkSafe Victoria.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Information security overview

Information and communications technology (ICT) has fundamentally changed the way that the public sector operates.

Today, the government and public sector relies heavily on ICT to effectively deliver services to the Victorian community and to efficiently manage its own internal activities.

However, ICT systems have inherent and significant risks, and external and internal threats to information security and privacy are increasing.

1.1.1 Information security policy and standards

Globally, information security policy and standards are based on the International Organisation for Standardisation ISO 27000 series of standards. These provide best practice recommendations on risks and controls within the context of an overall information security management system.

The Australian Government has also provided comprehensive policy and standards for Commonwealth departments and agencies:

- The Protective Security Policy Framework (PSPF) provides appropriate controls for the Australian Government to protect its people, information and assets, at home and overseas. The PSPF is managed by the Federal Attorney-General's Department.

- The Information Security Manual (ISM), which is the standard governing the security of Australian Government ICT systems and complements the PSPF. The ISM is managed by the Australian Signals Directorate.

1.2 Victorian Government cyber threat response

In November 2009, VAGO tabled a performance audit report on Maintaining the Integrity and Confidentiality of Personal Information. The findings from this report largely set the subsequent agenda for information security within the state government.

In October 2009, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) developed a new suite of Whole-of-Victorian-Government (WoVG) information security policy, standards and processes, aligned with the Australian Government framework and manual.

These new policy and standards apply to only 20 agencies and were communicated through the following key documents:

- SEC POL 01: Information Security Management Policy

- SEC STD 01: Information Security Management Framework

- SEC STD 02: Critical Information Infrastructure Risk Management.

In this audit we have referred to these 20 agencies as inner WoVG agencies.

The cyber threat to Victoria is real. According to the Cyber Security Operations Centre (CSOC) Cyber Intrusion Activity Report dated August 2013: Australian State and Territory Governments: January–June 2013:

'Between January and June 2013, there were approximately 40 cyber security incidents affecting state and territory governments. Of these 40 incidents, approximately 35 were considered serious enough to require further action and a CSOC response. The networks of the Victorian and West Australian state governments accounted for the highest proportion of cyber security incidents responded to by the CSOC between January and June 2013.'

Figure 1A Total cyber security incidents in Australia detected by or reported to the Cyber Security Operations Centre

Year |

Total incidents detected by or reported to CSOC |

Total incidents requiring a heightened response by CSOC |

|---|---|---|

2011 |

1 259 |

313 |

2012 |

1 790 |

685 |

To June 2013 |

789 |

398 |

Source: Australian Signals Directorate, 12 June 2013.

Australian Government information security frameworks require national coordination for relevant agencies to adequately understand and respond to cyber threats. This includes reporting these threats and their treatment to federal parliamentary committees.

In Victoria, the government is not provided with briefings or assessments on cyber threats affecting public sector ICT systems. Despite this, there have been recent moves to strengthen the oversight and regulation of data security and to better protect information held by the public sector.

On 20 December 2012 the Victorian Government announced that it had decided to merge two existing statutory roles—the Victorian Privacy Commissioner and the Commissioner for Law Enforcement Data Security—into a new statutory office to be known as the Victorian Privacy and Data Protection Commissioner. Legislation is expected to be introduced into Parliament in 2013 to give effect to this decision.

The new commissioner will oversee the current Victorian privacy and law enforcement data security regimes and will implement a Victorian Protective Security Policy Framework, across the Victorian public sector.

Information security will be a key element of the Victorian Protective Security Policy Framework and close cooperation will be required between the new Privacy and Data Protection Commissioner and central agencies with lead responsibilities for information security.

1.3 Governance arrangements

A restructure of the Victorian public service was announced by the Premier on 9 April 2013 and implemented on 1 July 2013. This had a direct impact on the implementation of the government ICT strategy which came into effect on 9 February 2013.

DTF was responsible for the government's ICT strategy until the appointment of the Chief Technology Advocate for Victoria in April 2013.

Until 1 July 2013, DTF was also the department responsible for developing and overseeing information security policy, standards and guidelines as well as being the operational lead agency to receive and disseminate cyber threat assessments.

From 1 July 2013, all operational ICT matters, including strategy, information security policy, standards and guidelines became a Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) responsibility.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) is responsible for coordinating a whole‑of‑government approach to critical hazards and has an interest in cyber security as part of its duty to monitor critical hazards to citizens and state assets.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

1.4.1 Objective

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of ICT security policy, standards and protection mechanisms for the state's ICT systems and data.

To address this objective, the audit examined whether:

- appropriate information security policy direction and guidance was in place to provide consistent protection to state ICT systems and data

- central agencies have oversight of, and coordinate responses to, WoVG information and system threats

- selected agencies had established and complied with information security policy, standards and processes.

1.4.2 Scope

The audit involved the following central agencies:

- the Department of Premier and Cabinet

- the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation

- the Department of Treasury and Finance.

We also tested ICT frameworks and systems in the following agencies:

- CenITex, an inner WoVG agency and the provider of ICT infrastructure services to all departments, except for the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

- three DTF portfolio agencies which have ICT systems critical to the state's revenue and financial assets:

- State Revenue Office—an inner WoVG agency

- Treasury Corporation of Victoria—an outer WoVG agency

- Victorian Funds Management Corporation—an outer WoVG agency

- IT Shared Solutions, which provides a shared ICT data centre, a network, and end‑user services for two outer WoVG agencies—WorkSafe Victoria and the Transport Accident Commission.

Two CenITex client departments were added to the audit in June 2013:

- the Department of Human Services

- the Department of Justice.

1.4.3 Review of agency compliance

VAGO appointed an independent specialist information security advisor to assist in reviewing whether agencies' policy, standards and processes comply with government policy and standards.

The advisor also conducted internal and external penetration testing of selected agency ICT systems under VAGO's supervision.

The independent specialist information security advisor assisted with the evaluation of agencies' compliance with relevant information security policy, standards and processes.

The approach used for this assessment involved:

- reviewing each agency's information security documentation

- identifying appropriate ICT systems for penetration testing by reviewing the key management and system control linkages described in the agencies' information security management frameworks (ISMF), analysis of self-assessments of these frameworks, critical information infrastructure reports and interviews with key officers

- reviewing any previous penetration test results

- conducting penetration testing of the selected system(s)

- reviewing management and system control reactions to weaknesses found with agencies' ISMFs and interviews with key officers

- developing conclusions as to how the agency would react to a credible and realistic threat situation.

1.4.4 Applicability of policy and standards

Inner WoVG agencies are required to comply with government policy, standards and guidelines, while outer WoVG agencies are not. However, each of the outer WoVG agencies audited had developed some information security policy and standards.

As part of this audit we reviewed each of their relevant documents against best practice principles, standards and controls, such as international information security standards and published frameworks.

1.5 Audit method and cost

Methods used for this audit included interviews with staff, direct observation and testing of operational ICT systems, and analysis of documents and data from agencies and other sources.

The audit was conducted under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $575 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

This report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines whether appropriate information security policy direction and guidance is in place to provide consistent protection to state ICT systems and data.

- Part 3 examines whether central agencies have adequate oversight of, and coordinate responses to, WoVG information and system threats.

- Part 4 examines whether selected agencies have established and complied with information security policy, standards and processes.

2 Appropriateness of policy direction and guidance

At a glance

Background

Victoria's information security policy, standards and processes are aligned with the Australian Government's information security frameworks.

Inner Whole-of-Victorian-Government (WoVG) agencies are required to comply with these standards by implementing their own information security management framework (ISMF) and reporting on their information security performance annually.

Conclusion

An appropriate information security policy and framework is in place, but it only applies to 20 inner WoVG agencies. Other public sector entities, including the outer WoVG agencies in this audit, are not required to conform to any specific policy or standard.

Findings

- Central agencies with a lead role in information security have adequately guided the inner WoVG agencies to implement information security frameworks, but have not overseen the adequacy of inner WoVG agency ISMF implementation.

- Outer WoVG agencies have received no central agency guidance or support on information security matters.

- Agencies need to make sure their annual ISMF reports reflect the true status of information systems, including those provided by third party shared services.

Recommendations

The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:- send the information security management policy to government for formal consideration

- mandate information security policy and standards across public sector agencies where the consequences of a security failure are significant for the state.

2.1 Introduction

Between October and December 2012, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) refreshed previous policies and standards for information security and published them in a suite of policy and framework documents.

These have been progressively implemented for inner Whole-of-Victorian-Government (WoVG) agencies but have never been considered by government or announced as official policy.

Inner WoVG agencies are required to develop an information security management framework (ISMF) based on the current standard and tailored for their particular activities.

Each agency's ISMF includes an annual self-assessment report which is consolidated with other inner WoVG agency reports. This allows the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) to oversee the information security status of agency information and communications technology (ICT) systems.

Outer WoVG agencies are not required to develop an ISMF, nor are they required to provide any reporting.

2.2 Conclusion

There is an appropriate information security framework in place for inner WoVG agencies. For these agencies, correct application of the framework would provide a satisfactory level of assurance.

However, no information security policy or framework has been presented to or endorsed by government.

Apart from certain reporting requirements for inner WoVG agencies and a program of training and briefings, there was no evidence that central agencies took any initiative to help these agencies apply the policy and framework.

Inner WoVG agencies need to be more rigorous in their self-assessment process. In particular, agencies using third party shared service providers need to be sure the report reflects both the status of their systems, and those provided by third parties.

DSDBI should review the self-assessment template and improve the questions in order to gain a more comprehensive overview of the status of Victoria's information security. Agencies should also be required to certify statements of compliance to address reported deficiencies.

2.3 Governance

DTF was responsible for developing and overseeing information security policy, standards and guidelines until 1 July 2013.

DTF developed a refreshed suite of inner WoVG agency policy, standards and processes for information security that aligned with the Australian Government Protective Security Policy Framework and Information Security Manual. The refreshed Victorian policy and standards were released progressively from October 2012.

Neither the current Victorian information security policy nor its predecessor released in 2005 has ever been presented to government. The importance of information security means that, at a minimum, a policy of this nature should be submitted for formal government consideration to avoid any ambiguity in its application.

DSDBI became responsible for implementing information security arrangements from 1 July 2013. This means that all operational ICT matters including strategy, information security policy, standards and guidelines are now a DSDBI responsibility.

2.4 Coordination and communication of policy, standards and templates

2.4.1 Inner WoVG agencies

There is effective communication of information security policy, standards and templates across inner WoVG agencies. The existence of the policy and standards is well known in these agencies because they are members of the Chief Information Officer Council, which has endorsed the information security policy.

The government has noted that the Chief Information Officer Council is the senior executive coordination and collaboration body for ICT in the Victorian public sector, responsible for ICT architectures, policies and standards, and operational ICT issues.

All inner WoVG agencies were also involved in an extensive program of information security training that DTF implemented and managed.

The current standards clearly set out inner WoVG agency responsibilities and how these are to be implemented. They document clear roles, responsibilities and accountabilities, and detail what is required of each inner WoVG agency in terms of its ISMF.

This approach provides a clear governance structure for the implementation of information security policy in the inner WoVG agencies for which it applies.

Inner WoVG agencies are required to submit certain reports annually to DSDBI that are intended to provide central oversight of the ability of these agencies' ICT systems to perform in a cyber threat environment. DSDBI is required to consolidate these reports and in turn report to the Deputy Secretary Leadership Group.

DSDBI does not critique agency ISMFs and agencies are not required to provide their ISMF to DSDBI. Given the relatively low level of maturity in information security in Victoria, this approach should be reviewed.

2.4.2 Outer WoVG agencies

There is no coordination and communication by DSDBI on information security matters with outer WoVG agencies. These agencies do not receive support from central agencies on information security matters.

There was also no expectation that agencies develop internal policy and standards, nor was there any guidance on how these agencies should address their information security requirements.

This is a significant weakness in DSDBI's overall knowledge of agency capability and visibility of risk to government services. This situation is unlikely to be unique to the outer WoVG agencies included in this audit. Outer WoVG agencies are individually responsible for determining whether their governance arrangements are adequate.

The other consequences for outer WoVG agencies are that they:

- are not required to report on the status of their ICT systems with respect to information security

- have no opportunity to share cyber alert information

- have inconsistent approaches to preparing and implementing their agency ISMF.

So, from a government and central agency viewpoint there is:

- no assurance that outer WoVG agencies are addressing information security matters

- no visibility of areas where assistance could be provided to minimise the cyber threat risk

- no ability to assess the risk posed to outer WoVG agency ICT systems in a hostile cyber threat environment

- no easy way to develop a whole‑of‑government current threat assessment and risk profile.

The current arrangements are insufficient. The four outer WoVG agencies audited are each responsible for significant sources of state revenue and control billions of dollars of financial assets.

Information security policy and standards should be mandated—not only for inner WoVG agencies, but also those outer WoVG agencies that operate ICT systems that have an aggregate high transactional value critical to state revenue, systems critical to public safety, or systems holding sensitive personal data with potential value to third parties.

2.5 Level of assurance for agencies

The current policy and standards would, if fully applied within agencies, provide a satisfactory level of assurance of an agency's ability to protect its data and reduce the risk of inappropriate release of information or unauthorised access to its ICT systems.

The lack of any specific information security guidance for outer WoVG agencies conflicts with the 2009 VAGO report recommendations previously accepted by DTF and the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

While not required to develop an ISMF, outer WoVG agencies are required to manage their information security risks in line with the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework. This requires that all departments and public sector agencies adopt a widely accepted best practice approach to make sure that their risks (including ICT risks) are being effectively managed.

While no government information security policies or standards apply to outer WoVG agencies, each outer WoVG agency selected for this audit had developed its own policy and standards.

These documents were subjected to detailed review as part of the audit process and our findings are included in Parts 3 and 4 of this report.

2.6 Information security management framework requirements

The information security standard requires inner WoVG agencies to develop an ISMF which shows progression over time towards compliance with the Australian Government Protective Security Policy Framework and Information Security Manual.

Both documents relate to ICT information, people, processes and assets including software, equipment and computer rooms.

The standard requires each inner WoVG agency ISMF to have four key documents:

- an ICT risk assessment report on the agency's ICT information, people, processes and assets

- an agency information security policy

- an ISMF self-assessment report and a compliance plan developed to address any significant non compliance issues

- an incident response plan with mandatory use of the Australian Signals Directorate online reporting application.

In April 2010, DTF briefed the Deputy Secretary Leadership Group (DSLG) that it would review each inner WoVG agency policy and their practices as part of a program of work known as DSLG 2.0. Inner WoVG agency information security policies were reviewed in 2010, but there was little evidence of any oversight of agency standards, controls and compliance since then.

Inner WoVG agencies selected for this audit said that they had not been asked to provide their policy and incident response plans and were only required to submit self‑assessment and critical information infrastructure reports.

Outer WoVG agencies were not required to have an ISMF.

2.6.1 Agency self-assessment reports

Inner WoVG agencies are required to submit an annual ISMF self-assessment compliance report in May each year from 2013 onwards, with a special first report required in December 2012 to initiate the process.

We reviewed both the December 2012 and May 2013 self-assessment reports and noted:

- not all inner WoVG agencies had provided reports

- little difference existed between the two successive reports

- the questions in the template were vague and did not provide a comprehensive status of an agency's information security.

DSDBI is required to summarise the self-assessment reports and brief the DSLG. This occurred after the December 2012 and May 2013 reports were received.

Where agencies use a shared service provider for their ICT systems, we noted significant shortcomings in the accuracy of ISMF reports. This is because there is little sharing of information on ICT systems and applications to ensure the completeness of the reports.

As a consequence, agencies were completing their ISMF without knowing the extent of any problems with ICT systems on which their applications and data were being hosted.

There is a need for inner WoVG agencies to:

- more rigorously complete their ISMF self-assessment report

- make sure agency statements of compliance reflect all non-complying issues in the ISMF self-assessment report

- make sure that, where any of their ICT services are provided by third party shared service providers, self-assessment reports include any provider problems that will have an impact on the agency's ability to deliver services.

DSDBI should improve the questions on the ISMF self-assessment report template to provide a more comprehensive overview. DSDBI should also require agencies to certify that their statements of compliance address all deficiencies in their ISMF self‑assessment reports.

Recommendations

The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:

- send the information security management policy to government for formal consideration

- amend information security policy and standards to include those outer WoVG agencies operating information and communications technology systems that have an aggregate high transaction value critical to state revenue, systems critical to public safety, or systems holding sensitive personal data with potential value to third parties

- require WoVG agencies to report any variations between the information security standards and their agency information security management frameworks, that have been approved by their agency head, as part of the annual information security management framework self-assessment reporting process

- require that each agency information security management framework self‑assessment report includes a statement of compliance addressing all self‑assessment report deficiencies

- develop processes for outer WoVG agencies to be included in relevant briefings and information security forums, and to be provided with advice and assistance outside of the WoVG Chief Information Officers Council

- improve the current information security management framework self-assessment report template to ensure a more comprehensive outcome.

Departments and agencies included in this audit should:

- take a more rigorous approach to completing their annual information security management framework self-assessment report

- make sure their annual self-assessment reports reflect the true status and risk to agency business from any third party service providers they may use.

3 Oversight and coordination of information security threats

At a glance

Background

The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) receives cyber alerts from Australian Government agencies and distributes them to relevant Victorian agencies.

Agencies are responsible for registering their internet protocol (IP) addresses with the regional registrar. The Australian Signals Directorate and other agencies use this registry to identify operators of networks facing a potential cyber threat.

Conclusion

Because agencies' reports on cyber attacks they have experienced are not consolidated, there is no central repository for government to analyse the type or incidence of cyber threats or the ability of systems to resist cyber attacks.

Cyber alerts depend on accurate IP information. DSDBI and individual agencies are not managing IP information to ensure correct and current information is available. This is essential for an effective response to detected cyber threats..

Findings

- There is neither a central, consolidated view of cyber threats, nor arrangements in place to brief government in the event of a multi-agency or sustained attack.

- DSDBI and individual agencies are not managing IP information to ensure correct and current information is available to cyber threat response agencies.

Recommendations

- The departments of Premier and Cabinet, and State Development, Business and Innovation shouldconfirm their respective roles and responsibilities.

- The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:

- establish an information security incident prevention and monitoring service for all government agencies

- maintain an accurate and current registry of IP addresses in use by government agencies to assist in effective response to cyber threats.

3.1 Introduction

All states and territories have nominated a single point of contact to receive Australian Government cyber alerts. In Victoria, the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) receives these cyber alert reports from Australian Government agencies and distributes them to relevant Victorian agencies.

Agencies experiencing serious cyber attacks are required to report these attacks to the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD) using ASD's online OnSecure incident reporting application.

Agencies are responsible for registering their internet protocol (IP) addresses with the regional registrar. ASD and other agencies use this registry to identify operators of networks which they suspect may be facing a potential cyber threat and then generate cyber alert reports accordingly.

3.2 Conclusion

Central agencies currently neither oversee nor coordinate responses to cyber threats targeted at public sector information and systems. However, as now advised by the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), this is expected to change with the formation of the State Crisis and Resilience Council (SCRC) once the Emergency Management Bill 2013 passes into legislation.

DSDBI distributes cyber alerts it receives from the Australian Government but does not coordinate any responses.

Agencies experiencing serious cyber attacks report these to ASD but not to DSDBI or DPC. As a consequence, there is no monitoring of the status of the 'live' cyber threat scenario or an understanding of systems' ability to resist cyber attack.

Further, DSDBI and individual agencies are not meeting their responsibilities to maintain correct and current IP address information. IP information is critical to cyber alert assessment because it identifies an incident and the information communications technology (ICT) systems under threat. We found a number of discrepancies between agency IP addresses in use, those registered and those included in lists.

3.3 Lack of central oversight

A significant difference between the policy and standards of the Victorian Government and the Australian Government is that federal agencies involved in information security have effective central coordination arrangements to oversee the threat and keep government informed.

A concerted attack on multiple agency ICT systems has the potential to be catastrophic, but there is no mechanism in Victoria to collect reports on such an attack beyond individual agencies reporting incidents to Australian Government agencies.

DPC is responsible for coordinating a whole‑of‑government approach to critical hazards and has an interest in cyber security as part of its oversight of critical hazards to state assets and citizens.

DPC has advised that it did not have a role in coordinating a whole‑of‑government approach to cyber threats and that individual agencies were responsible for their own information security arrangements. However, this position will change following the introduction of the Emergency Management Bill 2013 into Parliament on 31 October 2013.

The Bill establishes the SCRC which comprises all departmental secretaries and is chaired by the Secretary of DPC. Briefings on the cyber threat would be made to the SCRC by DSDBI as the agency with primary responsibility for Whole‑of‑Victorian‑Government (WoVG) ICT matters. The SCRC would in turn recommend briefings for ministers as appropriate.

3.4 Cyber alerts

3.4.1 Australian Signals Directorate cyber alert arrangements

Victoria, like other Australian states, relies on national security agencies to provide it with credible and realistic cyber alerts. DSDBI receives and distributes information and system threat alerts from the ASD Cyber Security Operations Centre (CSOC) in the form of general or specific alerts.

DSDBI distributes these alerts in accordance with Standard Operating Procedure – Distribution of Commonwealth Government Cyber Security Alerts, dated 28 March 2013. The procedure sets out the formats in which to convey cyber alert details to agencies, including distribution arrangements.

DSDBI's distribution lists include all inner WoVG agencies and certain libraries, educational institutions and museums. Surprisingly, they do not include most of the outer WoVG agencies.

DSDBI—and prior to 1 July 2013, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF)—has not been coordinating agency responses to cyber alerts or overseeing reporting arrangements by agencies, as it does not believe that there is any need for this type of oversight and coordination. DSDBI's view is consistent with the position taken by DTF.

The current procedure requires that inner WoVG agencies experiencing a cyber incident make mandatory information security incident reports to ASD in accordance with their incident response plan. These reports are submitted via the ASD's online OnSecure incident reporting application. ASD then provides a six-monthly report to DSDBI, which then submits it to the Chief Information Officer Council for consideration.

This could mean that there is no central agency oversight of serious incidents until six months after the event, and then the incident is only referred to the Chief Information Officer Council for its 'consideration'.

Victorian departments routinely experience cyber security incidents. Some agencies are detecting thousands of intrusion attempts per month, which range from minor errors when entering user names or passwords to serious attacks.

In 2012, inner WoVG agencies experienced 26 serious cyber threat incidents, of which half were reported by agencies to the CSOC. In the first six months of 2013, the Victorian and West Australian state governments accounted for the highest proportion of cyber security incidents reported to the CSOC. Common incidents included login credentials being stolen and published on websites frequented by cyber criminals and hackers, malicious code being used in online applications to trick a user or hijack a session, website defacement and malicious emails with embedded links or attachments.

3.4.2 Alternative cyber alert arrangements

In addition to the CSOC cyber alert arrangements, inner WoVG agencies and some outer WoVG agencies subscribe to a service provided by the Australian Computer Emergency Response Team, which provides updates on emerging threats and vulnerabilities, and recommendations on how to mitigate these.

The subscriber service includes continuous monitoring of external domain addresses and a response to any intrusions. A weekly report is sent to each subscriber agency.

Prior to 2011, this service was centrally funded by DTF but inner WoVG agencies now directly pay for the service. This new arrangement is unnecessarily complicated. A single arrangement for all Victorian Government ICT systems would be more practical and effective, and potentially cheaper.

3.4.3 Internet protocol address information

Accurate IP address information is critical to the cyber alert assessment process. Cyber security alerts rely on the accuracy of IP address information to identify an incident and the ICT system under threat.

The Standard Operating Procedure – Distribution of Commonwealth Government Cyber Security Alerts gives the responsibility of managing Victoria's public sector IP addresses to DSDBI. Individual agencies are responsible for maintaining correct information with the Asia‑Pacific National Internet Centre (APNIC) 'Whois' database. APNIC is the regional internet registry for the Asia‑Pacific region.

The maintenance of accurate IP address information is important because cyber security alerts relating to or based on IP addresses are validated by the Australian Government against the APNIC database.

If IP addresses are wrong then alert information will not be able to be distributed to the correct ICT system operator.

We found a number of discrepancies between agency IP addresses in use, those registered and those included in lists.

Recommendations

The Department of Premier and Cabinet, and the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:

- confirm their respective roles and responsibilities for information security once the Emergency Management Bill 2013 is enacted

- confirm that briefings on cyber threats will be made to the State Crisis and Resilience Council by the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation as the agency with primary responsibility for WoVG information and communications technology, and that the State Crisis and Resilience Council will in turn recommend briefings for ministers as appropriate.

The Department of State Development, Business and Innovation should:

- arrange for a cyber alert subscription service to be available to every government agency from a suitable provider

- develop and implement a process for maintaining a register of all IP addresses in use by public sector departments and agencies.

Departments and agencies included in this audit should:

- implement appropriate action to maintain the accuracy of their IP address information with the Asia‑Pacific National Internet Centre.

4 Agency compliance with policy, standards and process requirements

At a glance

Background

Each of the 20 inner Whole‑of‑Victorian‑Government (WoVG) agencies is required to develop its own information security management framework (ISMF), providing its agency with appropriate policy direction and guidance. There is no requirement for outer WoVG agencies to conform to any specified standard for their own agency ISMF.

Conclusion

All of the audited agencies had some information security policy and procedures in place. Compliance with these policies was better for inner WoVG agencies than outer WoVG agencies.

All examined agencies had previously conducted penetration tests—a method of testing for vulnerabilities—on their information communications technology (ICT) systems. Some of these tests were narrowly scoped and there were instances of previously identified problems not having been addressed.

Overall, there is a low level of awareness of how an agency's ICT systems are likely to perform if subjected to a cyber attack.

Findings

- The audited inner WoVG agencies have reasonably well developed ISMFs.

- Outer WoVG agencies are less advanced with their information security policies.

- Centrally sponsored training has had a positive impact on inner WoVG agencies.

- Penetration testing of ICT systems is inconsistent and too narrowly focused.

Recommendations

All public sector agencies in Victoria should:

- urgently implement the Australian Signals Directorate Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions

- retain responsibility for managing and allocating passwords if third party service providers are used.

4.1 Introduction

Currently, only the 20 inner Whole-of-Victorian-Government (WoVG) agencies are required to develop and implement an information security management framework (ISMF) that conforms to the published public sector standards.

All other Victorian outer WoVG agencies are not covered by these requirements. It is up to each of these agencies to separately develop and apply a framework to protect the systems they control or information they hold.

4.2 Conclusion

None of the agencies included in this audit has fully complied with government information security policy and standards. However, each of the audited agencies did have some information security policy in place.

The two inner WoVG agencies subjected to penetration testing for this audit had achieved partial compliance but did not have a plan in place to achieve a fully compliant ISMF.

The outer WoVG agencies had commenced using international standards as a basis for development of an ISMF but none had a complete ISMF in place.

All agencies had undertaken penetration testing of their information and communications technology (ICT) systems. Some of these tests were too narrowly scoped and there were multiple instances of previously identified problems not having been remediated. There was also little evidence that they tested all of their ICT systems.

Overall awareness of how public sector ICT systems would perform if subjected to a cyber attack is unsatisfactory. Closer central agency involvement is necessary until an acceptable level of information security maturity is reached across public sector agencies.

4.3 Developing and applying an effective information security framework

4.3.1 Inner WoVG agencies

Inner WoVG agencies had developed a range of internal standards, controls and compliance arrangements based on published Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) standards—now published by the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI).

However, there were several examples of the application of these standards being inadequate and incomplete in the audited agencies:

- An agency had not based its ISMF on the relevant mandatory standards and had no formal plans to address this. While there is a provision for agencies to seek approval for non compliance, there is no evidence that this protocol had been followed. It is difficult to understand why, in this instance, the agency did not simply conform to expected requirements instead of making a huge effort to develop their own approach.

- Another agency had principles and guidelines published as an ICT policy. The document did not clearly articulate the organisation's intent and expectations, and consequently was of limited value.

- An agency's reasonably well developed ISMF had not been effectively communicated or embedded in the organisation. During an interview with a key manager, it was clear that they were not aware of policy relating to urgent software patching requirements. When shown the agency policy, the manager stated that they had not seen the policy before.

Although the information security standards require policy deviations to be managed, none of the inner WoVG agencies had plans to manage this, and none of the examined agencies maintain registers of non compliance.

In some instances inner WoVG agencies are reliant on third parties for the provision of certain services. Agencies are required to take account of any deficiencies in the third party provider's services in completing their ISMF self-assessments. This requires close cooperation with the third party provider which was not always evident. Agencies using third party shared services should ensure that the contractual arrangements provide for the required level of cooperation to accommodate ISMF requirements and commitments.

4.3.2 Outer WoVG agencies

Outer WoVG agencies took a responsible approach to information security and were genuinely concerned about protecting their systems from cyber threats.

However, these agencies were less advanced with their information security policy implementation, in part because they are not driven and guided by the DTF framework —now DSDBI.

Only one outer WoVG agency had a documented, stand-alone ISMF. For other agencies, policy documentation was embedded within ICT procedure documentation, which was not easily accessible to agency management or staff.

Only one of the four audited outer WoVG agencies was aware of the DSDBI policy and standards, and two agencies were aware of the Australian Government documentation. All were aware of the ISO 27000 series of international information security standards.

All audited outer WoVG agencies indicated that some level of guidance and assistance from DTF, and DSDBI since 1 July 2013, would have helped these agencies apply consistent and comprehensive standards and better understand what was expected of them.

4.4 Australian Signals Directorate strategies

The DTF framework—now DSDBI—mandates that inner WoVG agencies should implement the Australian Signals Directorate's (ASD) Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions. These are a set of strategies that ASD claims prevent at least 85 per cent of targeted cyber intrusions.

The 'Top 4 Strategies' are:

- use application 'whitelisting' to help prevent malicious software and other unapproved programs from running

- maintain up‑to‑date software patches for applications such as PDF readers, Microsoft Office, Java, Flash Player and web browsers

- maintain up‑to‑date patches of operating systems

- minimise the number of users with administrative privileges.

This section examines how well these strategies have been applied, finding significant weaknesses that both inner and outer WoVG agencies need to address.

4.4.1 Application 'whitelisting'

An application 'whitelist' is a list of applications permitted to run on a device. It is designed to protect against the activation of unauthorised and malicious programs.

Two of the six audited agencies used application whitelists.

Agencies should review the whitelisting guidelines published on the ASD website and develop and implement a whitelisting strategy.

4.4.2 Patching of applications and patching of operating systems

A patch is a piece of software designed to fix security vulnerabilities and other bugs, or to improve the usability or performance of an application or operating system.

We identified:

- examples in all agencies of ineffective patching and system configuration issues, resulting in systems being exposed to risk

- a rolling three- and six‑month patching strategy in one agency that could not accommodate urgent patches

- agencies using unsupported operating systems and software

- agencies not having well developed processes to review the severity of issues and the applicability of vendor provided patches.

The audit identified patching issues at all examined agencies. The biggest impediment to patching appeared to be a lack of resources to test the impact of vendor patches on agency networks and software applications.

This practice is concerning as it does not take into account the implications of the rapidly changing cyber threat environment faced by public sector ICT systems.

Agencies should review patching guidelines published on the ASD website and develop, implement or review their patching strategy.

4.4.3 Administrative privileges

User accounts with administrative privileges are a key target for hackers because they permit high-level access to an organisation's systems, including any data the administrator can access, which generally means 'everything'.

We found that the management of privileged access by key users was poor across all agencies:

- Only one agency used an application to manage its privileged passwords.

- Management of privileged accounts was ad hoc, lacked procedures and was manually applied, if at all.

- In one agency, some 70 per cent of staff had privileged access to systems, and such access was generally allocated permanently rather than on an 'as required' basis.

- In a number of cases, passwords for privileged accounts were simple and easy to guess.

During penetration testing for this audit, a number of password lists were found and used to gain access to user accounts. Audit testing:

- found passwords in an unprotected file thatallowedaccess to an account held on behalf of the agency with an overseas financial institution

- easily hacked a local administrative password, which could have permitted access to and control of some 6000 computing devices on a network

- found some passwords to be of poor strength and low complexity.

A number of agencies included in the audit used third party service providers for some of their services. In all cases the provider was responsible for allocating passwords and for managing their ongoing use. This is a risky practice as it relies on the integrity of organisations which the agency cannot oversee. Where third party providers are used, agencies should retain management and allocation of all passwords.

4.5 Additional internal vulnerabilities

Internal vulnerabilities are typically weaknesses in security that allow attacks from insiders such as staff, contractors, vendors and hackers who have gained internal network access.

We found examples of system vulnerability that included:

- use of an unauthorised laptop on a password controlled network, allowing the penetration testing team to access a department's secure environment, which contained sensitive applications and personal information

- widespread use of memory devices such as DVD/CD burners and USB memory sticks, with no ability to detect what data had been copied onto them from the system

- widespread and uncontrolled access to social media and email websites.

To manage the social media risk, the State Revenue Office has developed an application to manage social media and email website access. The approach shown in Figure 4A could be applied across all government agencies.

Figure 4A

Managing social media and personal email access

Social media and personal webmail present a potential security threat.

Confidential information can leak through these channels, and security can be compromised through links to other sites and material entering systems through them as well.

Staff may want to use these sites while at work, in accordance with the organisation's acceptable use policy. To make this possible, and at the same time improve data security, an ICT solution was developed that would achieve both outcomes.

Regular internet access was restricted so that social media and webmail could not be accessed. Instead, a new icon was deployed on desktop computers through which staff could have access to these sites.

This icon was named the Protected Internet Access (PIA) environment. It connects to an internet browser window with no access to the internal network.

When in the PIA, staff are prevented from attaching and sending agency files, printing, or copying/pasting data from their desktop or the agency network into social networking sites and webmail. As with regular internet access, the PIA environment is monitored and controlled for acceptable use.

An unexpected benefit of implementing the PIA was a 70 per cent reduction in the use of the internet for non-business purposes.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office using State Revenue Office information.

4.6 Agency penetration testing

Penetration testing is a method of testing for vulnerabilities within an ICT system in order to gain access to critical data, simulating what an attacker might be able to do. The results expose possible security weaknesses in a system as well as testing its ability to detect and prevent attacks.

While all audited agencies conducted penetration testing in the past 12 months, we found problems with the scope of penetration testing, particularly:

- inconsistency in the nature and level of penetration testing

- multiple examples of problems identified from previous penetration testing not having been remediated

- narrow testing scopes that focus too much on systems already known to be satisfactory.

Many of the detailed findings arising from fieldwork for this audit are sensitive to the security of public sector ICT systems and it is therefore not in the public interest to include them in this report.

However, to make sure that agencies take appropriate steps to address observed weaknesses and breaches, the Auditor-General has issued management letters to each agency subject to this audit. The letters set out recommended actions and seeking a response from the agencies indicating their acceptance, as well as their intended actions and time frames.

The detailed management letters contain 58 issues resulting in 111 recommended actions. The breakdown of the recommended actions is in Figure 4B.

Figure 4B

Recommended actions in management letters agreed with agencies

|

Agency(a) |

Recommended actions |

Agreed with agency |

Critical level completed by agency |

Medium level completed by agency |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Critical‑level risk(b) |

Medium‑level risk(c) |

Total |

||||

|

Agency 1 |

– |

11 |

11 |

11 |

– |

2 |

|

Agency 2 |

3 |

12 |

15 |

15 |

3 |

4 |

|

Agency 3 |

– |

14 |

14 |

14 |

– |

6 |

|

Agency 4 |

3 |

9 |

12 |

12 |

3 |

3 |

|

Agency 5 |

6 |

35 |

41 |

35 |

2 |

2 |

|

Agency 6 |

– |

18 |

18 |

12 |

– |

– |

|

Total |

12 |

99 |

111 |

99 |

8 |

17 |

(a) Due to security sensitivities the relevant agencies have been de-identified.

(b) A critical-level risk is a high information security risk which requires an urgent assessment of the risk and implementation of mitigating controls.

(c) A medium-level risk is a moderate- or long-term information security risk which should be assessed and mitigating controls implemented as soon as possible.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

VAGO will periodically examine whether these findings are being remediated over an acceptable time frame and may, at its discretion, report to Parliament on progress at a future date.

Recommendations

All public sector agencies in Victoria should:

- review the Australian Signals Directorate Top 4 Strategies to Mitigate Targeted Cyber Intrusions, and implement these practices as a matter of urgency

- retain responsibility for managing and allocating passwords if third party service providers are used

- review the patching guidelines published on the Australian Signals Directorate's website and develop, implement or review their patching strategy.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

Introduction

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report was provided to the named departments and agencies with a request for submissions or comments.

The submissions and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

Responses were received as follows:

- Department of State Development, Business and Innovation

- CenITex

- Department of Human Services

- Department of Justice

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Department of Treasury and Finance

- Treasury Corporation of Victoria

- Transport Accident Commission and WorkSafe

- State Revenue Office

- Victorian Funds Management Corporation

Further audit comment:

Auditor-General's response to the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of State Development, Business and Innovation

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of State Development, Business and Innovation – continued

Auditor-General's response to the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation

Despite the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) accepting the finding underpinning Recommendation 15, DSDBI has proposed an alternative approach to implementing it. Since the inception of this audit (9 April 2013) DSDBI has never discussed this approach with VAGO until its response of 22 November 2013. Further, it has provided neither the rationale for this nor detail on the nature and content of this approach; including how it will address the audit finding related to password issuing controls.

VAGO remains of the view that agencies need to retain responsibility for managing and allocating passwords in order to ensure that agency data is properly protected. In order to be assured that DSDBI's proposed approach will be effective, VAGO will follow up on the specific actions that DSDBI proposes to achieve the objective of the recommendation.

RESPONSE provided by the Chief Executive, CenITex

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Human Services

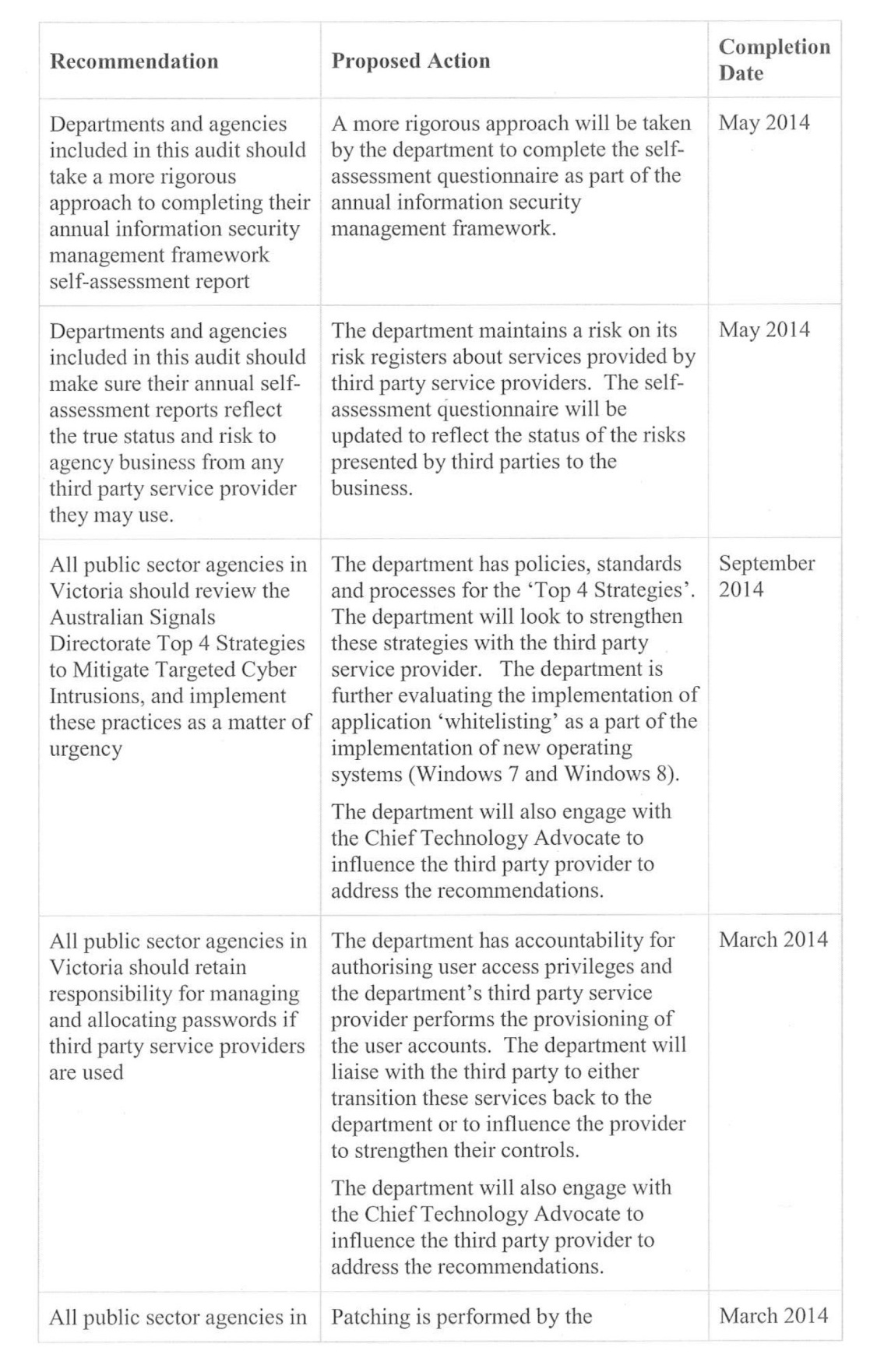

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Justice

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Justice – continued

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Justice – continued

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Premier and Cabinet

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Premier and Cabinet – continued

RESPONSE provided by the Secretary, Department of Treasury and Finance

RESPONSE provided by the Deputy Managing Director/Corporation Secretary, Treasury Corporation of Victoria

RESPONSE provided by the Chairperson, Transport Accident Commission and the Chairperson, Victorian WorkCover Authority

RESPONSE provided by the Chairperson, Transport Accident Commission and the Chairperson, Victorian WorkCover Authority – continued

RESPONSE provided by the Commissioner of State Revenue, State Revenue Office

RESPONSE provided by the Chairman, Victorian Funds Management Corporation