Withdrawal from 2026 Commonwealth Games

Audit snapshot

What we examined

We examined the cost of securing, planning for and then withdrawing from the 2026 Commonwealth Games (the Games) and the quality of agencies' advice to the government.

We examined the Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions (DJSIR), Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF), Department of Transport and Planning, Visit Victoria, the Victoria 2026 Organising Committee also known as Victoria 2026 Pty Ltd, Development Victoria and 5 local councils.

Why this is important

In April 2022 the Victorian Government signed the contract to host the Games in regional Victoria based on an expected gross cost of around $2.6 billion.

Host cities typically have 7 or 8 years to prepare for the Commonwealth Games. But Victoria only had 4 years to deliver the event. This included building sports venues and athletes' villages.

In July 2023 the government decided that the Games no longer represented value for money and withdrew. It said the cost of hosting had increased to more than $6 billion.

There is significant public interest in understanding the amount of public money spent on the Games, the reasons for the increased cost and the quality of advice the public service gave to the government.

What we concluded

The total cost of the Games to Victorians is over $589 million. This waste would have been avoided if agencies had worked together better to give frank and full advice to the government before it decided to host the Games.

The government relied on DJSIR's business case when it decided to host the Games and determined the budget. The business case raised the risks associated with hosting the Games. But it underestimated the costs and overstated the benefits. DJSIR, DPC and DTF knew this but did not advise government to delay a decision on hosting until a fit for purpose business case could be provided.

DPC and DTF consistently raised cost and other risks during 2022 and early 2023. But they did not advise government that hosting the Games might be unfeasible until June 2023.

The cost estimate for the Games that the government publicly released in August 2023 of $6.9 billion was overstated and not transparent. It added significant amounts for industrial relations and cost escalation risks. But it did not disclose that the budget already included $1 billion in contingency allowances to cover these and other cost risks.

After the government decided to withdraw from hosting, DPC quickly settled the state's liabilities.

What we recommended

We made 2 recommendations to DPC and DTF about:

- reviewing the issues with advice to the government that we identified in this report

- further supporting and guiding the public sector in providing frank, full and timely advice to the government.

Video presentation

Key findings

Source: VAGO.

Our recommendations

We made 2 recommendations to address the issue we identified. The relevant agencies have accepted one of these recommendations in part.

| Key issue and corresponding recommendations | Agency response(s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue: Agencies did not work together effectively to give frank, full and timely advice to the government | ||||

| Department of Premier and Cabinet, and Department of Treasury and Finance | 1 | Work with the Victorian Public Sector Commission to conduct a review into why the public sector's advice to the government on the 2026 Commonwealth Games did not always meet the standards required by the Public Administration Act 2004 and key guidance documents. This should include identifying what changes are needed, including behavioural, to enable the public sector to make sure this is not repeated in similar circumstances in the future (see Section 3). | Not accepted | |

| 2 | As part of this review:

Key documents include, but are not limited to the:

| Accepted in part | ||

What we found

This section summarises our key findings. Sections 1, 2 and 3 detail our complete findings, including supporting evidence.

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

Why we did this audit

In April 2022 the government signed the contract to host the 2026 Commonwealth Games (the Games) in the regional cities of Geelong, Ballarat, Bendigo, Latrobe and Shepparton.

Typically, Commonwealth Games hosts have 7 or 8 years to prepare. But Victoria committed to hosting the Games in 4 years.

In July 2023 the government announced its withdrawal from hosting the Games due to unexpected cost increases. The state finalised its withdrawal in August 2023. At the time we finalised this report, the government had not announced what the cost of bidding for and then withdrawing from the Games was.

We did this audit to make the cost of the Games transparent. We also wanted to understand if public sector agencies gave comprehensive advice about the Games to support the government's decision-making.

Our key findings

Our findings fall into 4 key areas:

| 1 | The Games cost Victoria over $589 million. |

| 2 | The Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions' (DJSIR) business case for the Games was inadequate to support an informed decision by the government on the likely costs and benefits of hosting. |

| 3 | Agencies did not always work together effectively to give frank, full and timely advice to the government. |

| 4 | The original Games budget was unrealistically low, but the $6.9 billion cost estimate the government publicly released when it withdrew from the Games was overstated. |

Key finding 1: The Games cost Victoria over $589 million

Overall cost

The decisions to bid for, plan and then withdraw from the Games have cost Victoria over $589 million with no discernible benefit.

This waste of taxpayer money on an event that will not happen is significant, especially considering the state’s recent sustained operating deficits and rising debt levels.

The costs fall into 4 major areas, with most related to withdrawing:

| Of the $589 million … | Was or will be incurred by ... | On … |

|---|---|---|

| $112 million (19%) | DJSIR | employee and operating costs, including fees paid to the Commonwealth Games Federation (the Games Federation) but excluding payments to Development Victoria for venues and athletes' villages. |

| $38 million (6%) | the Victoria 2026 Organising Committee (the Organising Committee) | employee and operating costs. |

| $42 million (7%) | Development Victoria | detailed planning and delivery cases for venues and villages, including due diligence, design work, site investigations, early works planning, employee costs and professional services. |

| $380 million (64%) | the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) on behalf of the state | settling the cancellation of the host contract with the Games Federation. |

Settling the withdrawal from the host contract

In August 2023 Victoria agreed to pay $380 million and signed a settlement agreement with the Games Federation, Commonwealth Games Australia (CGA) and the Commonwealth Games Federation Partnerships.

We refer to these 3 bodies collectively throughout the report as the Commonwealth Games parties.

The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) led the settlement negotiations on behalf of the state. It achieved a quick settlement that resolved the state's liabilities from the decision to withdraw.

Key finding 2: DJSIR's business case for the Games was inadequate to support an informed decision by the government on the likely costs and benefits of hosting

Weaknesses in the Games business case

DJSIR's business case did not make a convincing argument that the benefits of hosting the Games outweighed the costs and risks.

DJSIR highlighted that its cost estimates required significant further work.

Due to time constraints from deciding to host the Games later than usual, the business case did not include all the steps required by DTF's Investment Lifecycle and High Value High Risk Guidelines. Despite this, DJSIR still recommended hosting the Games.

DJSIR based its costings on desktop research and information about how much previous Commonwealth Games cost. There was no consultation with the regional councils that controlled most of the venues that would be required for the Games.

This approach was not reasonable given that a regional, multi-city delivery model had never been used before and would have to be delivered in an extremely short timeframe.

The costings also assumed that the government would receive funding from the Australian Government and local councils, despite having no firm commitments from either.

Due to these limitations DJSIR presented its cost estimates in 'ranges' from best to worst case scenarios rather than providing a best estimate, which is the standard format for a business case.

Presenting different options to the government

DTF's guidelines say that a business case should include analysis of different options to deliver a project. However, DJSIR only considered 2 options: to host or not to host.

The business case did not analyse any other possible and potentially lower-cost options, such as:

- holding some events in Melbourne, which CGA had proposed, where the required sports venues and accommodation already existed

- a model with most events in a single regional city.

While the idea of Victoria hosting the Games was first suggested by CGA, Visit Victoria developed the regional multi-city concept.

It was the government's decision to support this concept. And DJSIR should have presented a range of delivery options. DJSIR told us it did not do this because the government provided a clear direction that it was only interested in a regional Games.

Overstating the benefits of hosting the Games

DJSIR's business case presented a high-level preliminary assessment of the benefits of hosting the Games.

Major predicted benefits for regional cities included increased tourism and converting the athletes' villages into social or affordable housing.

DJSIR also estimated that around 20 per cent of the benefits would come from avoided health costs due to increased physical activity and civic pride in regional areas. DTF assessed these benefits as speculative and overstated and advised DJSIR to remove them just before the government considered the business case. But DJSIR included them in its benefit–cost ratio.

DJSIR told us it did not have time to consider and respond to DTF's concerns and that it estimated the benefit–cost ratio using established practices and it stands behind its analysis.

DJSIR accurately predicted risks to the delivery costs

The Games business case identified a range of risks that eventuated and contributed to cost pressures.

These risks included:

- a lack of time to build venues and athletes’ villages

- supply chain constraints

- limited availability of labour and resources in regional areas

- limited accommodation in regional areas for visitors and the Games workforce

- a lack of time to undertake due diligence before signing the binding host contract.

The business case acknowledged these risks. But it only presented very high-level suggestions on how to mitigate them.

Given the preliminary nature of DJSIR's analysis it is not clear how it ultimately determined that delivering the Games within 4 years was ‘high risk but achievable’.

DJSIR told us it based this advice to government on its professional judgement and experience delivering other infrastructure projects.

Missed opportunity to improve the business case

In February 2022 the government announced that Victoria was in exclusive negotiations with the Games Federation for a regional-led Games. This gave DJSIR an opportunity to refine the business case.

Before this, DJSIR was not able to consult widely because the fact that Victoria was considering a bid was not public knowledge.

DJSIR could have used the announcement to do more detailed work and consultations to improve the accuracy of the business case's budget and delivery timelines.

This would have been consistent with the government's decision when it first considered the draft business case at the end of January 2022 that DJSIR would further refine it in consultation with DTF. This could have included engineering site inspections for proposed sports venues.

DJSIR also could have consulted with local councils about how they could contribute to the Games.

The updated business case provided to the government in March 2022 was largely the same as the draft. However, Figure 1 shows that the updated business case did include a higher budget range and a lower benefit–cost ratio.

Projects with a benefit–cost ratio of less than 1.0 do not usually proceed.

Figure 1: Estimated benefit–cost ratio and net cost in the draft and updated business cases

| Draft business case (January 2022) | Updated business case (March 2022) | |

|---|---|---|

| Estimated benefit–cost ratio | 1.2–1.8 | 0.7–1.6 |

| Estimated net cost | $1.4–$1.6 billion | $1.5–$2.5 billion |

Source: VAGO, based on information from DJSIR.

Despite these changes, there is no evidence that the revised figures were more accurate.

This is because the updated business case used the same assumptions and disclosed the same limitations about it being preliminary as the January 2022 draft.

Differences between DJSIR's advice to the Minister and the Minister's advice to the government on costs

In early March 2022 DJSIR briefed the Minister for Tourism, Sport and Major Events (the Minister) and recommended that they seek approval from the government for a gross budget of up to $3.2 billion.

This reflected the high-cost scenario in the business case. The Minister accepted DJSIR's advice and approved the submission recommending this funding amount on 10 March 2022.

However, the final submission, which was dated the same day, recommended that the government approve a Games budget consistent with the low-cost option, which was a gross budget estimate of $2.7 billion.

DJSIR has given us evidence that suggests this change was made at the request of the Minister’s office. The 2022–23 state Budget, which was released in May 2022, disclosed $2.6 billion of approved funding for the Games.

This was slightly less than the $2.7 billion approved in March 2022 because the government agreed to remove funding of around $51 million allocated for additional sports that had not been selected yet.

Key finding 3: Agencies did not always work together effectively to give frank, full and timely advice to the government

Delays in sharing information

DTF and DPC told us that throughout the planning for the Games, DJSIR did not always:

- work cooperatively with them to make sure they had enough time to review key briefings and submissions

- provide requested information.

This limited DTF and DPC's ability to provide timely and comprehensive advice to the government on the risks and cost of the Games.

These departments raised their concerns with DJSIR. DJSIR's responses indicated that its approach reflected the Minister for Commonwealth Games Delivery's (minister for Games delivery) wishes.

Victoria’s system of government requires departments to respond to and implement government policies, priorities and decisions in a manner consistent with the public sector values set out in the Public Administration Act 2004. This includes implementing reasonable directions from ministers.

The Public Administration Act 2004 requires public officials to provide frank, impartial and timely advice to the government. This will sometimes require public officials to give the government advice that it may not want to receive.

Public sector agencies can give advice in a range of ways, including by:

- preparing briefs

- developing business cases

- drafting submissions for ministers to present for the government's consideration.

It is standard practice that an agency seeks input from DTF and DPC when it drafts a submission.

DTF and DPC’s role is to consider the quality and accuracy of the draft submission, highlight any risks and state if they support the agency's recommendations.

It is important that agencies give DTF and DPC enough time to review their work and incorporate feedback into their draft submission.

DPC and DTF told us that DJSIR's engagement, collaboration and information sharing improved from April 2023.

Weaknesses in DTF's and DPC's advice about the Games

DTF’s and DPC’s advice to the government about the Games was clear about the risks. But their advice was not always sufficiently comprehensive and frank.

This is because, at key stages, both departments formally recommended that the government proceed with the Games despite significant and unresolved concerns.

For example, in March and April 2022, before the state signed the host contract, DTF identified material concerns and risks for the state relating to the reliability of DJSIR's estimated costs for the Games.

DTF suggested that the actual costs were likely to exceed the quantifiable benefits from the Games. This meant that the benefit–cost ratio for the Games was likely below 1.0.

Despite these concerns DTF:

- supported recommendations that the state host the Games and underwrite the costs

- recommended that the Treasurer support signing the host contract.

DPC had similar concerns about the reliability of the Games costs. But it placed no emphasis on these concerns when it briefed the Premier in April 2022 in support of the state signing the host contract.

Despite consistently raising risks, DTF and DPC did not advise the government that hosting the Games might be unfeasible until June and July 2023.

Managing time pressure

All agencies involved in the Games were under extreme time pressure, especially between February and April 2022. This is when the government considered the business case and signed the host contract.

However, as Victoria was the sole bidder for the Games, the government (through DJSIR) could have used its position to seek more time from the Games Federation to conduct comprehensive due diligence. The Games Federation faced pressure of its own because it had not identified a host yet.

Instead, DJSIR, with the government's agreement, worked within the Games Federation's stated timeframe, even though DTF advised DJSIR that there were serious delivery risks and unresolved issues with the host contract.

Key finding 4: The original Games budget was unrealistically low, but the final estimated cost of $6.9 billion was overstated

Increases in cost estimates

As planning and delivery work for the Games progressed, agencies refined their budget estimates to more accurately reflect the expected costs.

In April 2023 the minister for Games delivery advised the government that delivering the Games would require an increased gross budget of $4.5 billion, up from $2.6 billion. They based this advice on a submission prepared by DJSIR.

This advice indicated that the revised gross budget excluded around $240 million in transport costs and $300 million in policing costs. Including these costs meant the Games was projected to cost around $5 billion.

The $2.6 billion gross budget the government approved for the Games in 2022 included provisions for transport and some police costs.

The submission overstated the level of funding the state could reasonably expect from the Australian Government and local councils. This meant the net cost of the Games to the state was also understated.

DJSIR's revised budget assumed the Australian Government would contribute $1.3 billion towards the Games even though:

- the Australian Government had not committed to this

- DTF had advised DJSIR and the government that the Australian Government's contribution would likely not exceed $300 million.

In its brief for a June 2023 submission to the government, DJSIR advised the minister for Games delivery that it was 'highly possible' the Australian Government would not contribute $1.3 billion.

DJSIR said that $200 million to $600 million was a more likely contribution based on previous events.

The minister for Games delivery's submission to the government noted that funding from the Australian Government was not confirmed and the net cost of the Games would increase if it was not secured. However, the submission did not mention the high likelihood it would not be obtained.

When the government announced that Victoria was withdrawing from hosting the Games in July 2023 it said the cost of hosting was certain to exceed $6 billion.

In August 2023 the government released budget information that indicated the final cost could have been around $6.9 billion.

Unrealistic costs in the business case

The business case made key assumptions about how much various aspects of the Games would cost.

Some of these assumptions, including assumptions about costs for venues, temporary infrastructure and athletes' villages, were unrealistic even at the time the government agreed to host the Games.

Other expected costs increased over time due to more detailed planning work and government decisions, including its decision to add more sports.

| The business case assumed that … | But ... | This meant that the expected cost of … |

|---|---|---|

| the Games would include at least 16 sports and up to 5 more sports to be decided. | an additional 4 sports and 3 cycling disciplines were added in October 2022, which required changes to villages and venues. | the Games increased by $247 million. |

| private developers would build the villages and sell the dwellings after the Games. | there was not enough time to find, negotiate with and appoint developers. So the state needed to develop the villages itself (and take on the risk of selling them after the Games). | villages increased from $212 million to a net cost of $576 million, based on a total cost of $1.0 billion to build the villages. |

| the scope for the athletics venue at Eureka Stadium was expanded to provide more lasting benefit to the community. The government decided to build 2 new separate venues for aquatics and gymnastics. | major competition venues increased by $220 million from $222 million to $442 million. |

| temporary infrastructure, such as portable buildings and temporary grandstands, would cost around $283 million. | this initial estimate was unrealistic and additional sports and venue changes increased costs. | temporary infrastructure increased by $216 million to an estimated $499 million when the government withdrew from the Games. |

The government approved a revised gross budget of up to $3.6 billion in April 2023

On 5 April 2023 the government discussed the Games budget and agreed in principle to a revised gross target budget of $3.6 billion.

The government asked the minister for Games delivery to prepare options to achieve this.

On 20 April 2023 the minister for Games delivery presented a submission to the government that DJSIR drafted to inform the government about the Games budget and expected costs. This submission sought approval for a revised gross budget of $4.5 billion.

The government did not accept this request and agreed to a revised gross budget of $3.6 billion. It requested further advice from the minister by June on how the Games could be delivered in regional Victoria for that budget.

DJSIR prepared a draft submission for the minister in June 2023 and sought approval for a revised gross budget of at least $4.2 billion. But DPC and DTF did not support this draft submission and it did not proceed to the government for consideration.

Unsubstantiated risks in the July 2023 budget estimate

In July 2023 the minister for Games delivery made a submission to the government that advised the Games could not be delivered for $3.6 billion without abandoning the principle of a wholly regional Games or significantly reducing the number of sports, venues and villages.

The minister sought approval for a revised budget of $4.2 billion to host the Games.

This submission included advice on what DJSIR described as significant 'black swan' risks, including industrial relations issues and what was described as 'hyper-cost escalation', which had not been identified in previous advice to the government.

Black swan risks are generally understood as risks with extreme impacts that could not have reasonably been predicted based on past experience. The risks DJSIR identified did not meet this accepted understanding of a black swan risk because industrial relations issues and the potential for cost escalation are routinely considered when planning and delivering any government-funded project.

DJSIR's advice in the minister's submission in relation to these risks was not comprehensive because it did not clearly outline:

- how it calculated the risks' financial impact

- the extent to which contingency allowances already built into the budget could mitigate the risks' potential financial impacts.

DTF told us that it did not have enough time or information supporting the costed risks to verify what DJSIR based them, and the estimated cost impacts, on.

The final cost estimate was overstated

In August 2023 the government suggested that the Games could cost around $6.9 billion.

This figure is overstated because it double counts costs relating to industrial relations risks and cost escalation risks.

The $6.9 billion estimate included:

- a $1 billion contingency allowance, including $551 million of estimates for individual cost items and a project-wide contingency provision of $450 million

- $2 billion for additional cost pressures primarily relating to industrial relations risks and cost escalation risks.

The contingency amounts were intended to cover risks, including industrial relations risks and cost escalation risks. But these risks were also costed and included in the $2 billion estimate for additional cost pressures as part of the total budget estimate of $6.9 billion.

The total contingency allowance in the overall cost estimate of $1 billion should have been deducted from the total estimate of potential cost pressures.

Fairly presenting the contingency allowance and additional costs would have resulted in a gross estimated cost of around $5.9 billion instead of around $6.9 billion.

The minister for Games delivery's July 2023 submission to the government noted that with additional police and transport costs and the potential for emerging risks to be realised, the total gross cost to deliver the Games was likely to be between $5 billion and $6 billion.

DJSIR advised us that:

- it did not provide the advice that the Games could cost around $6.9 billion, which the government publicly released. It understands that DPC and DTF prepared this advice

- DPC and DTF did not consult with DJSIR or seek its advice on the accuracy of the July 2023 cost estimate in the document the government publicly released

- the cost estimates for individual risks comprising the $2 billion for additional cost pressures identified as part of the July 2023 cost estimate of around $6.9 billion were not necessarily mutually exclusive and were not intended to be added together.

DJSIR did not make it clear in the July 2023 submission to government that it did not intend for the additional cost pressures to be added together. DPC and DTF relied on this submission to compile the final cost estimate for the Games. This resulted in the cost estimates for individual risks being added together despite DJSIR's intentions.

1. Context

The Commonwealth Games is an international multi-sport event involving athletes from Commonwealth nations and territories. It was first run in 1930 and has taken place every 4 years since 1950. Victoria was selected as the host for 2026.

Background to Victoria’s bid for and withdrawal from the Games

The need for a 2026 host

The Games Federation, which oversees the Commonwealth Games, selects the host cities and controls the sports program.

Host cities typically have 7 or 8 years to plan for the Commonwealth Games:

- The bid to host the 2018 Commonwealth Games at the Gold Coast was launched in 2010 and was announced as successful in November 2011.

- In 2015 the South African city of Durban was awarded the 2022 Commonwealth Games.

In 2017 the Games Federation removed Durban as host for the 2022 Games. Birmingham and the UK government stepped in to host the 2022 Games. Birmingham had intended to bid for the 2026 Games.

Birmingham hosting the 2022 Games meant the Games Federation needed to identify a host for the 2026 Games.

During 2019 CGA was working with the Government of South Australia and City of Adelaide on a possible bid for the 2026 Games.

The Games Federation was expected to announce the 2026 host city in 2019. But the decision was postponed until 2020, and further to 2021 and finally to 2022.

These circumstances meant that Victoria had less time than usual to plan for the Games.

Visit Victoria’s regional Games concept

CGA approached Visit Victoria in the first half of 2021 to discuss a potential bid for the 2026 Games.

CGA put 2 proposals to Visit Victoria – one in June and the other in July 2021. These proposals included options for events in regional Victoria with Melbourne and Geelong as co-host cities.

Visit Victoria did not formally respond to either of these proposals. But it saw the potential to host the Games in regional Victoria. It began working on this concept in mid-2021 without involving CGA.

Visit Victoria approached the Games Federation with a proposal to host the Games in regional Victoria in November 2021 after discussions with the Minister, Premier, Treasurer and DPC.

In early December 2021 the Minister wrote to the Games Federation authorising Visit Victoria to engage directly with it to present the proposal and indicating an intent to ask for an exclusive negotiation period.

Visit Victoria presented the proposal to the Games Federation in London on 8 December 2021.

On 15 December 2021 Visit Victoria signed an agreement with the Games Federation and CGA to secure an exclusive negotiation and due diligence period for the regional Games concept.

Host contract negotiation and Games budget

The government did not formally consider a potential bid for the Games until it received a draft business case in January 2022.

On 15 February 2022 the government signed a heads of agreement with the Games Federation and CGA. The next day the government announced that it was in exclusive negotiations to bring the Games to regional Victoria.

In March 2022 the government considered an updated version of the business case and approved a gross cost estimate of around $2.7 billion for the Games budget. This was subsequently reduced slightly and the 2022–23 state Budget disclosed a budget of $2.6 billion.

In April 2022 the Games Federation awarded the Games to Victoria and the state signed the host contract.

Withdrawal and termination

On 14 July 2023 the government considered, but did not support, a submission from the minister for Games delivery that:

- requested a revised gross budget of $4.2 billion

- highlighted that additional police and transport costs and the potential impact of emerging risks meant the total gross cost to deliver the Games would be between $5 billion and $6 billion.

The next day the government decided that it would seek to terminate its host contract with the Commonwealth Games parties.

On 17 July 2023 the government agreed to a regional support package of investments worth $2.0 billion comprising of various housing, tourism, sporting and development initiatives to deliver legacy benefits for the state, support Victorian communities and affected local councils and deliver wind-up activities required to conclude the Games planning activities.

On 18 July 2023 the Premier publicly announced that the government had decided not to proceed with hosting the Games based on the estimated cost exceeding $6 billion. The Premier said the costs were too high, at more than double the estimated economic benefits for Victoria.

The Premier said the government:

- had told the Games Federation and CGA about its decision to terminate the host contract

- was seeking to quickly and amicably resolve the contract and settle costs.

The Premier simultaneously announced the regional support package.

As we discuss in Section 2, the government also publicly released a document that detailed the budget increases between the March 2022 business case and July 2023, which prompted its decision to withdraw.

On 19 August 2023 the government and the Commonwealth Games parties issued a joint statement.

The statement said they had confidentially negotiated and reached an agreement, with the assistance of mediators, to settle all disputes relating to the cancellation of the multi-hub regional Victoria Games.

The State of Victoria agreed to pay the Commonwealth Games parties $380 million to settle all remaining liabilities.

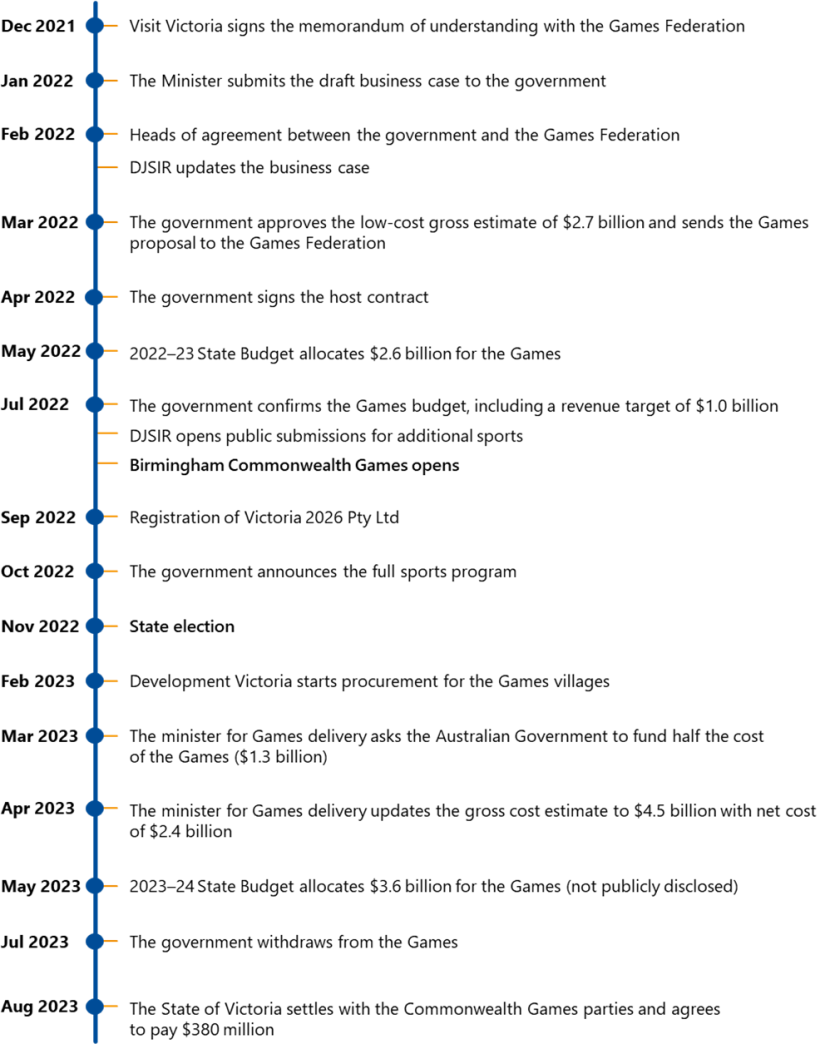

Timeline of key events

Figure 2 highlights key events from the date the memorandum of understanding was signed by Visit Victoria to the date the State of Victoria settled with the Commonwealth Games parties.

Figure 2: Timeline of key events

Source: VAGO.

Roles and responsibilities

Key agencies

Figure 3 shows the key agencies involved in planning the Games and their roles and responsibilities.

Figure 3: Agencies involved in the Games

| Agency or body | Key role and responsibilities for the Games |

|---|---|

| Commonwealth Games Australia (CGA) | CGA is an Australian membership-based, non-government organisation. It represents the sports that participate in the Games. The state’s bid for the Games required CGA’s endorsement. |

| Commonwealth Games Federation (the Games Federation) | The Games Federation is an international, London-based organisation that holds the rights to, and is responsible for directing, the Games. |

| Department of Jobs, Skills, Industry and Regions (DJSIR) | DJSIR was the main agency tasked with delivering the Games. It was established on 1 January 2023 and took over the work of the former Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions. For consistency we refer to DJSIR in this report when referring to both the current and former department. A new secretary was appointed to DJSIR at the end of March 2023. DJSIR seeks to support a strong and resilient Victorian economy by supporting businesses and industries to grow and build vibrant communities and regions. The Office of the Commonwealth Games (the Games Office) was established within DJSIR to lead coordination and oversight of the Games planning and budget. Sport and Recreation Victoria was part of DJSIR during the planning for the Games. |

| Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) | DPC leads whole-of-government policy and performance. It supports the government to achieve its objectives and effective public administration. DPC provided advice to the government about the Games and reviewed advice prepared by other agencies. |

| Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) | DTF provides economic, financial and resource management advice to help the government deliver its policies. DTF provided advice to the government about the Games, particularly its financial impact, and reviewed advice prepared by other agencies. |

| Department of Transport and Planning (DTP) | DTP is responsible for transport and land use planning. It was the lead agency responsible for planning and delivering transport for Games spectators and the Games workforce, including trains, buses, and park and ride or walk sites, and managing the road network. |

| Development Victoria | Development Victoria is a property developer for the government. It seeks to deliver homes and communities and revitalise major activity centres and urban precincts. Development Victoria led the planning and delivery for the Games villages and major competition venues. |

| Victoria 2026 Pty Ltd, which is known as the Victoria 2026 Organising Committee (the Organising Committee) | The Organising Committee was established to deliver the Games event. It was previously part of DJSIR but was transferred to the government-controlled company Victoria 2026 Pty Ltd on 5 December 2022. It was responsible for:

The Organising Committee's board included representatives from the Games Federation and CGA. |

| Visit Victoria | Visit Victoria is a not-for-profit, government-controlled company. The Premier is its sole member. It has a board of directors and delivers tourism marketing and event procurement for Victoria. DJSIR funds Visit Victoria and has portfolio responsibility for the company. But it is not involved in its operational decision-making. Visit Victoria approached the Games Federation in November 2021 about a potential bid for Victoria to host the 2026 Games in regional cities. It was also involved in early feasibility work and preparing marketing strategies for the Games. |

Local councils:

| The government engaged these local councils after the state made its bid public. They were expected to help the government plan and deliver the Games in their local municipalities and make financial contributions. |

Source: VAGO.

2. The cost of the Games

In March 2022 the government approved a gross cost budget of $2.7 billion for the Games with an estimated net cost of $1.6 billion.

When the government announced that Victoria would withdraw from hosting the Games in July 2023, it stated that the cost of hosting was certain to exceed $6 billion.

But both of these cost estimates were unreliable – the first estimate was understated and the final one was overstated.

There were better cost estimates available that should have been used development when making the case for the Games and for subsequently withdrawing.

Government projects with a benefit–cost ratio of less than 1.0 usually do not proceed. The business case provided to the government in March 2022 said the Games had benefit–cost ratio of between 0.7 in the worst case and 1.6 in the best case.

However, if all of the speculative benefits and questionable cost reductions were removed, the benefit–cost ratio would have been 0.59 to 0.95.

Background

Our analysis

In this section we analyse the estimated and budgeted gross and net incremental costs of the Games from a public finance perspective. We also evaluate the actual costs incurred using this framework so that we are comparing like with like.

Importance of net incremental cost

In the context of the state Budget, the cost of hosting the Games is best understood and evaluated in terms of the net incremental cost to public finances.

The net incremental cost is the additional (gross) operating and capital outlays required to deliver the Games minus:

- the externally generated revenue that flows to the state directly from the Games

- any funds contributed by other governments.

In other words, the net incremental cost is how much the state needs to spend to host the Games compared to not hosting them.

This can then be compared to the incremental benefits expected from the Games to determine if the benefits exceed the costs.

The Commonwealth Games Value Framework, which was published by the Games Federation in December 2019, also recommends using the net incremental cost approach.

Operating costs

The Commonwealth Games Value Framework notes that games-related operating costs are driven primarily by factors such as the:

- number of sports

- number of participating athletes and officials

- security requirements, which impact police and security costs

- desired service levels, such as:

- the standard of venues

- the experience of athletes, media and the Games Family, which includes officials, dignitaries and guests accredited by the Games Federation

- sport presentation

- the standard of the opening and closing ceremonies.

Operating costs can be examined and usefully compared over time and between Commonwealth Games. This is because differences in gross and net costs can be reasonably attributed to and understood in terms of the decisions the host makes in relation to these factors.

Capital costs

Games-related capital spending, primarily on venues and villages, is generally not comparable between Commonwealth Games.

This is because the scale of capital expenditure varies significantly depending on the extent and quality of host cities’ existing infrastructure, their objectives and their appetite to invest.

Estimated gross and net costs

2022–23 state Budget

In March 2022 the government approved a gross cost estimate of $2.681 billion and a net cost of $1.638 billion for the Games.

It did this knowing that these figures were presented to it as the best possible scenario. The worst case scenario assumed comparatively higher costs and lower revenue.

The government used the best-case estimate, with a minor adjustment, for the 2022–23 state Budget.

The basis on which the numbers were estimated, and the cost ranges provided, was severely constrained by both:

- the time available for DJSIR to compile them

- a lack of consultation and necessary detailed planning.

This meant that using the best-case estimate reflected, at best, an unwarranted optimism bias. At worst it was simply unrealistic and misleading.

That these estimates were unreliable and likely to change was made clear in the advice provided to the government by DJSIR, DPC and DTF at the time. The risk was only in one direction – higher costs and lower revenue.

2023–24 state Budget

By April 2023 the government was told that the most likely gross cost of the Games would be $4.5 billion with a net cost of $2.4 billion.

By this time the higher operating cost estimates were more reliable because DJSIR and other delivery agencies had done a more thorough and considered analysis.

The higher estimated capital costs also were more reliable. But these costs were not directly comparable to the March 2022 estimates.

This was largely because:

- the delivery model for the villages had changed to the state being the developer and taking on all the costs and revenue risks

- of decisions the government made about increasing the number of sports and changing the location of venues.

The 2023–24 state Budget included an updated gross output cost estimate of $3.6 billion.

This estimate was not shown separately in the budget papers because it formed part of a general contingency allowance in the state Budget. It also was not referred to in evidence given to the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee in its May and June 2023 hearings into the Budget.

July 2023 estimates

By July 2023 the estimated gross cost had increased to $4.86 billion and the net cost to $3.76 billion. This was driven mainly by increases in operating cost estimates for security and transport, which had been significantly underestimated.

When it compiled the final Games budget for public release in August 2023, DPC added another $2.005 billion to these estimates for 'additional cost pressures' based on advice to the government from DJSIR in July 2023. But this amount was not allocated to specific line items. This brought the gross cost estimate to $6.865 billion and the net cost to $5.764 billion.

Changes to budget estimates

Figure 4 shows how agencies' advice to the government on the Games budget changed during 2022 and mid-2023.

We analyse the reasons for changes in each major line item in this section.

Figure 4: Changes to the Games budget estimates between March 2022 and July 2023 ($ nominal)

| March 2022 | April 2023 | July 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Worst case ($ million) | Best case ($ million) | DJSIR revised ($ million)* | DTF advice ($ million) | |

| Capital costs | 1,069 | 680 | 1,710 | 1,674 |

| Athletes' villages | 265 | 212 | 1,024 | 1,024 |

| Major competition venues | 455 | 222 | 442 | 442 |

| Community competition venues | 339 | 237 | 244 | 208 |

| Other – public domain | 10 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Operating costs | 2,160 | 2,001 | 2,798 | 3,186 |

| General operations – the Organising Committee and the Games Office | 1,142 | 1,116 | 1,475 | 1,357 |

| Temporary infrastructure – villages and venues | 321 | 283 | 519 | 499 |

| Transport | 120 | 120 | 68 | 306 |

| Police and security | 219 | 219 | 204 | 492 |

| Games fees | 85 | 85 | 82 | 82 |

| Contingency | 273 | 178 | 450 | 450 |

| Total (gross) costs | 3,229 | 2,681 | 4,508 | 4,860 |

| Operating revenue | 254 | 268 | 176 | 176 |

| Broadcast rights and sponsorship income | 140 | 140 | 92 | 92 |

| Ticket sales | 69 | 83 | 74 | 74 |

| Other sources of funding | 249 | 775 | 1,925 | 925 |

| Australian Government | 217 | 229 | 1,300 | 300 |

| Victorian Government sport infrastructure funding | 0 | 227 | 0 | 0 |

| Development Victoria debt to be recouped by selling village dwellings | n/a | n/a | 447 | 447 |

| Victorian Government social housing funding | 0 | 211 | 71 | 71 |

| Local councils | 32 | 108 | 107 | 107 |

| Total operating revenue and funding | 503 | 1,043 | 2,101 | 1,101 |

| Net incremental cost to the state Budget | 2,726 | 1,638 | 2,407 | 3,759 |

Note: The cost estimates for the athletes' villages are not directly comparable between 2022 and 2023. The 2022 estimates assumed that the state would only need to pay to construct the affordable and social housing dwellings planned in each location, with private developers funding the villages' construction cost. The 2023 estimates assumed that the state would fund the full cost of constructing the villages.

In April 2023 DJSIR reported lower budget figures for transport and security because they were to be partly funded under other funding requests to the government. DTF's advice added these costs back in to give the government a more comprehensive whole-of-government cost estimate. In July 2023 DJSIR also reduced the villages budget by $39 million based on the government charging reduced land tax for village sites. Again, DTF saw this as cost shifting and added the cost back in its advice to the government.

Figures may not add due to rounding.

Source: VAGO, based on information from DJSIR, DTF and DPC.

Major changes in estimates

Between March 2022 and April 2023 DJSIR's estimates for the Games:

- total gross capital costs for competition venues and public domain improvements increased by 46.2 per cent from a best-case estimate of $469 million to $686 million

- total operating revenue fell by 34.3 per cent from $268 million in the best-case estimate to $176 million. The biggest decline was in broadcast rights and sponsorships

- other external (non-state) funding sources fluctuated. But these changes were not based on any negotiations or substantive agreements with either the Australian Government or local councils.

Capital costs and funding offsets for the villages

Contractual obligations

Under the host contract, the state needed to provide accommodation for 7,000 athletes, para-athletes and teams officials during the Games in March 2026.

To satisfy these requirements the government planned to build villages in 4 host hubs – Ballarat, Bendigo, Geelong and Morwell – consisting of approximately 1,300 dwellings.

This would have involved a mix of permanent and relocatable dwellings.

Private developer model

In the March 2022 business case DJSIR assumed that private developers would finance the villages and recover their costs by selling the dwellings afterwards.

This was like the model used in the Melbourne 2006 Commonwealth Games.

The Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games used a public–private partnership model where the state gave additional support to private contractors.

However, the March 2022 model was not informed by market soundings. Specific sites had not been identified and secured and no other options had been explored.

The model was cost neutral from the perspective that it would not require additional government funding.

The business case assumed that the state would only need to pay to construct the affordable and social housing dwellings planned in each location as part of its legacy program.

The initial Games budget assumed that Homes Victoria would fund these costs, which were estimated to be between $212 and $265 million, from its budget allocations under the Big Housing Build program.

The business case treated these funds as offsets when arriving at the net cost of the Games.

State developer model

Development Victoria started planning work for the athletes' villages in June 2022. It found that there was not enough time before the Games to find, negotiate with and genuinely transfer risks to private developers before construction needed to start.

Instead, the state would need to fund the whole cost of building the villages and seek to recover the cost by selling the dwellings after the Games.

There were a number of constraints specific to the Games, which do not typically apply to conventional housing developments, that affected the commercial feasibility of the village developments. The state developer model was implemented to manage these constraints and emerging risks, including:

- market demand risks, including risks relating to the types of dwellings to be constructed for the villages, that created the potential for development revenue to be lower than forecast

- site-specific risks, including obtaining planning approvals and managing latent conditions, contamination, and flora and fauna

- timeline risks, with the state having a shorter timeframe than previous Commonwealth Games to plan and construct the villages while also delivering them across 4 sites and against an immovable deadline.

Incomparable changes to estimated gross cost of athletes' villages

In April 2023 DJSIR advised the government that the estimated gross cost under the state developer model to build the villages would be $1.024 billion. It said this would be financed by:

- Development Victoria borrowing $448 million

- Homes Victoria contributing $71 million for social and affordable dwellings

- $505 million in output funding added to the state Budget.

The apparent significant increase to the estimated development cost is not comparable with the cost in the Games business case because the delivery model changed.

For comparative purposes only, in the 2023 figures DJSIR included an estimate of $489 million for construction costs, which would have been financed by the private sector under the private developer model assumed in the March 2022 business case and initial Games budget.

When we add in the $212 million assumed in the initial Games budget for social housing costs, this implies that the total development cost was originally expected to be around $700 million.

The villages delivery case that Development Victoria prepared for the government in 2023 listed factors that contributed to the cost increases, including:

- 55 per cent of the village dwellings would be temporary due to site and timeframe constraints. Temporary dwellings would:

- cost 10 per cent more to build per square metre than permanent dwellings

- sell for 50 per cent less

- provide reduced legacy benefits to communities

- village dwellings would be higher density than commonly found in regional areas, which would likely lead to slower sales

the tight timeframes reduced the state's bargaining power and meant that Development Victoria embedded 17.5 per cent contingency into its estimates for the cost of building the villages (13.7 per cent of the total project cost) when similar projects delivered to more standard timelines would have a 10 per cent contingency.

Athletes' villages estimated incremental cost to the state

The state originally estimated that it would need to pay between $212 million and $265 million for village dwellings that would be used for affordable and social housing.

This was shown as a revenue offset from Homes Victoria in the best-case estimate. But it should not have been.

This is because the site locations and the number and configuration of the dwellings were determined by the host contract requirements. This means it may have not aligned with Homes Victoria's strategic priorities, plans and timelines under the Big Housing Build.

In comparison, after accounting for social and affordable housing, the incremental cost to the state under the state developer model was $505 million, which Figure 5 shows. This was the additional amount that the government needed to subsidise. When considering the net cost of the Games, it is this amount and Homes Victoria's costs of $71 million that are relevant, which add up to $576 million, not the gross development cost.

Figure 5: Estimated incremental cost to the state and funding sources for athletes' villages under state developer model

| March 2022 | April 2023 | July 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletes' villages | Worst case ($ million) | Best case ($ million) | DJSIR ($ million)2 | DTF advice ($ million) |

| Construction cost | 265 | 212 | 1,024 | 1,024 |

| Funded by: | ||||

| n/a | n/a | 447 | 447 |

| 0 | 212 | 71 | 71 |

| 265 | 0 | 505 | 505 |

Note: Figures may not add due to rounding.

Source: VAGO, based on information from DJSIR, DTF and DPC.

Figure 6 shows the number and types of dwellings during and after the Games and Development Victoria's expected loss from sales of dwellings.

Figure 6: Development Victoria's expected net proceeds from selling dwellings

| Dwellings during the Games | After the Games (permanent dwellings only) | Nominal ($ million) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Total | Relocatable | Affordable/social | Market | Cost | Sales | Loss |

| Geelong | 487 | 202 | 72 | 213 | 397.91 | 239.64 | −158.26 |

| Ballarat | 456 | 456 | 0 | 0 | 321.45 | 160.46 | −160.99 |

| Bendigo | 232 | 9 | 56 | 167 | 197.18 | 107.11 | −90.07 |

| Morwell | 136 | 56 | 10 | 70 | 106.99 | 51.28 | −55.71 |

| Total | 1,311 | 723 | 138 | 450 | 1,023.53 | 558.49 | 465.03 |

Note: Development Victoria expected to sell 450 dwellings to the market and 138 to Homes Victoria at a loss of $465.03 million. It based this on combined sales proceeds of $558.49 million. The sales price to Homes Victoria was estimated to be $71 million excluding GST.

Sales revenue for relocatable dwellings did not include transport or site preparation costs and was estimated to be just their direct construction costs with no margin.

Figures may not add due to rounding.

Source: VAGO, based on the villages delivery case considered by the government in April 2023.

On a like-for-like basis, the increase in the incremental cost to the state between the original private developer model and the state developer model is around $364 million based on the projected sales income.

However, this cost may have increased because of uncertainty about future sale proceeds due to low buyer demand in regional areas for the types of housing in the villages.

This uncertainty prompted Development Victoria to seek assurance from DTF that the state would cover any shortfall.

Future plans for the athletes' villages

Before the government withdrew from the Games Development Victoria began several procurement processes to appoint contractors to construct the villages.

These processes were at different stages. They involved selecting potential contractors to prepare sites and build the dwellings.

The procurements have been paused since July 2023.

Capital costs and funding offsets for competition venues

Major and community competition venues

The original business case for the Games distinguished between the estimated capital costs for major competition venues and community competition venues.

A major competition venue was a venue that required a total estimated investment of more than $50 million.

The government planned 3 major competition venues to host 4 sports – athletics, aquatics, gymnastics and weightlifting.

The capital costs for the community competition venues were largely for 10 of the 16 remaining sports – badminton, boxing, Twenty20 cricket, hockey, lawn bowls, netball, Rugby Sevens, squash, table tennis and shooting.

Incremental cost of venues

The March 2022 business case included a low-cost estimate of $458.5 million for all competition venues and a high-cost estimate of $794.2 million.

The low-cost scenario comprised $222.0 million for major competition venues and $236.5 million for community competition venues. This included $194.5 million for up to 21 sports, plus an additional $41.9 million for other venues.

The approved low-cost scenario also included an assumed 'revenue' offset of $227 million, which was to be funded from state sporting infrastructure programs delivered by Sport and Recreation Victoria. This appeared to reduce the net cost of the Games by $227 million.

However, this was misleading because Sport and Recreation Victoria was not going to fund this revenue offset from its existing programs. Instead, it was expected to seek additional funding from the state Budget.

In April 2023 DJSIR advised the government that Sport and Recreation Victoria had not requested any additional funding for this purpose and had no unallocated funding available.

This led to DJSIR removing the revenue offset from the Games cost estimates.

Changes to the estimated cost of major competition venues

The approved low cost estimate of around $222.0 million for major competition venues involved:

- hosting athletics at Eureka Stadium in Ballarat for a capital upgrade cost of $10.6 million

- co-locating gymnastics and aquatics at Kardinia Park in Geelong, with an estimated investment of $211.4 million.

In October 2022 DJSIR submitted draft delivery cases to the government with recommendations that it expand the scope for the major competition venues and note that this scope had an estimated cost of $442.1 million.

The increased costs were driven by the government's decisions to approve venue scope and location changes to boost their legacy benefits to the community. These changes included:

- more extensive and higher-cost improvements to Eureka Stadium, which were expected to cost around $150 million

- moving gymnastics and aquatics from Kardinia Park to new venues in Waurn Ponds and Armstrong Creek respectively at a total cost of around $292 million, despite a lack of support from the local council.

The relevant councils still expect the government will invest in these major competition venues.

This is due to commitments the government made when it announced it was withdrawing from hosting the Games.

Operating costs

General operating expenses

General operating expenses related to operating costs that are not included in other budget line items for temporary infrastructure, transport, police and security, Games fees and contingencies.

Costs in this category included the costs to run the Organising Committee and Games Office and for:

- opening and closing ceremonies

- event workforces

- sports equipment

- marketing

- broadcasting.

The Games Office and the Organising Committee split the responsibility for these costs.

When the government approved the Games budget in March 2022 it approved the low-cost estimate for general operating costs, which was $1.116 billion.

This estimate was primarily based on the costs of the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games, adjusted for inflation and the multi-site regional delivery model.

On 6 March 2023 DJSIR briefed the minister for Games delivery and indicated the need to seek an increased budget to deliver the Games. In April 2023 DJSIR advised the government that the original estimate for general operating expenses was insufficient to deliver the Games.

DJSIR's revised estimate was $1.475 billion. This was an increase of $360 million, or 32 per cent, from March 2022.

Increase to general operating expenses for the Games Office

The Games Office's general operating costs increased by around $79 million from the $234 million approved by the government as part of the Games budget in March 2022 to $313 million in April 2023.

The main increase was $32.9 million for additional staff to bring resourcing in line with the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games.

DJSIR advised the government that the initial budget for Games Office staffing was based on incorrect information about staffing levels for the 2018 games.

Increase to general operating expenses for the Organising Committee

The Organising Committee's estimated general operating expenses increased by $281 million from the $882 million approved by government as part of the Games budget in March 2022 to $1.16 billion in April 2023.

The Organising Committee followed an original budget that was higher than the cost estimate approved by the government in March 2022. This is because the committee's budget was based on the host contract, and was $1.26 billion, not $882 million. The $1.26 billion also included temporary infrastructure, police and security costs.

In February 2023 the Organising Committee advised the Games Office that it needed $1.94 billion for gross operating costs. This was an increase of $678 million from its original budget of $1.26 billion.

The Organising Committee considered this the minimum amount it needed to meet its obligations in the host contract and deliver the government's vision and risk appetite.

The Organising Committee told the Games Office that the increased costs were because:

| The original cost estimate … | This meant the Organising Committee needed … |

|---|---|

| did not include sufficient provision for inflation. | to include higher provisions for inflation between 2022 and 2026 in its cost estimates. |

seemed unreasonable after detailed budget work.

| more funding to:

|

| did not fully reflect the complexity of delivering the Games across 5 regional areas. | more funding to run multiple villages and non competition venues, such as media centres and Games headquarters. |

| did not consider the additional sports added to the Games program. | more funding for broadcasting, the Games workforce and other costs, such as technical officials and sport equipment. |

Cost reductions

Alongside the request for increased funding for the Games Office and Organising Committee, the minister for Games delivery's April 2023 submission to the government also proposed scope reductions to reduce the overall cost of the Games. The government agreed to scope reductions that reduced the Games Office's and Organising Committee's general operating costs by $134.5 million.

In July 2023 the minister for Games delivery proposed a further $100 million reduction in general operating costs, but did not specify which areas this reduction would impact. The minister committed to report back to government on this later in 2023.

DTF's advice to government correctly identified that these savings could end up increasing cost pressure because the Organising Committee was responsible for delivering critical Games services.

Temporary infrastructure costs

Changes to temporary infrastructure costs

Temporary infrastructure, or overlay, was required to support new and existing competition venues and villages during the Games. It included seating, broadcast lighting and portable buildings that would be removed after the Games.

The budget for temporary infrastructure also included the cost to restore permanent facilities back to their original state.

When the government approved the Games budget in March 2022 it approved the low-cost estimate for temporary infrastructure in the business case, which was $283.4 million.

The original budget for temporary infrastructure was based on the cost for the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games adjusted for the multi-site model.

In April 2023 DJSIR provided high-level cost estimates to government. It said that the cost for temporary infrastructure would increase to around $519 million.

DJSIR's advice indicated that the reasons for the cost increase included:

- the estimate in the business case was too low because it underestimated the type, extent and cost of temporary infrastructure required to deliver the Games

- extra temporary infrastructure was needed to support additional sports that were not originally planned.

When the government decided to withdraw from the Games in July 2023 the estimated cost for temporary infrastructure was $499 million.

Impact of adding sports to the Games

In its 2026/30 Strategic Roadmap, which it published in October 2021, the Games Federation recommended that approximately 15 sports feature at the Commonwealth Games. This was to provide continuity and certainty for hosts and athletes. It also expanded the list of core sports to choose from.

The program of sports included in each edition of the Games is one of the many elements a host negotiates and agrees on with the Games Federation.

When the government signed the host contract in April 2022 it agreed to run 16 sports across multiple disciplines and events, with up to 5 more sports to be decided.

In October 2022, the government added 4 additional sports and 3 more cycling disciplines. This followed an open submission process where all sports with a recognised international federation were invited to submit an expression of interest.

The sports added to the Games program were assessed by a panel that included representatives from the Organising Committee, the Games Office, Sport and Recreation Victoria and Visit Victoria. The panel assessed submissions received against criteria that addressed:

- Games Federation requirements including universality and quality of competition and alignment with the Federation's values

- economic impacts

- community impacts

- deliverability issues including costs, timelines and athlete numbers.

CGA and the Games Federation were also consulted on the selections, which the host contract required.

The panel recommended the selected sports, which were then endorsed by the government and the Games Federation board.

The government's decision to expand the sporting program added an estimated $247.4 million to the expected cost of the Games.

These extra costs related to venue and temporary infrastructure changes. This included building a temporary velodrome for track cycling, which would provide no legacy benefits for the community. By April 2023 the estimated cost of the temporary velodrome was $54.9 million.

In comparison, the high-cost scenario in the March 2022 business case included $105.9 million for a new permanent velodrome in regional Victoria, which did not have any suitable existing venues for track cycling.

In its media release responding to the government's decision to withdraw from the Games the Games Federation said:

‘Since awarding Victoria the Games, the Government has made decisions to include more sports and an additional regional hub, and changed plans for venues, all of which have added considerable expense, often against the advice of the Commonwealth Games Federation (CGF) and Commonwealth Games Australia (CGA)’.

Operating costs for transport and security

What the transport and security budget was based on

The Games business case and budget considered by the government in 2022 both included provisions for transport and police costs on a net additional outlays or net incremental costs basis.

This meant the approved Games budget was intended to cover the additional or non business as usual costs that Victoria Police and DTP expected to incur to provide Games related police and transport services.

This was confirmed in:

- DJSIR's advice to the government in March 2022 about the business case and budget

- the April 2022 host contract, which said the Organising Committee's budget allowances for transport and security included Victoria Police and DTP costs based on net additional outlay assumptions consistent with the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games.

The minister for Games delivery, who was appointed in June 2022, made a submission to the government on the Games budget in July 2022.

This submission included broad implications about the transport and security budget allocations. It also recommended that the government agree that activities supporting the Games, which were not specifically funded in the Games budget, would be funded from relevant departments' and agencies' existing budgets through business-as-usual activities, reprioritisations and leveraging planned activities.

This recommendation was not based on DJSIR's advice. The minister added it to the final submission when they lodged it.

This meant DTF and DPC were not consulted on the recommendation. The Treasurer's private office advised DTF that:

- neither it nor the Premier's private office were consulted about the recommendation

- it had requested the minister's office to remove the recommendation.

The recommendation was not removed from the submission.

DTF did not support the recommendation because, in its view, the original budget presented to the government in March 2022 was intended to represent the total cost of hosting the Games, including the costs of additional activities for departments and agencies supporting the Games.

DTF proposed an alternative recommendation. The government:

- noted that the original budget presented to the government, including the budget in the business case, represented the total cost of hosting the Games across all departments and agencies

- agreed that wherever possible, contributions from relevant departments and agencies would be funded by business-as-usual activities, reprioritisations and leveraging other planned activities. If further resources were required in exceptional circumstances, the government would consider funding them through discussion with the minister for Games delivery.

The government did not fully approve the minister's recommendation. But this decision opened the door to shift responsibility for costs that were initially intended to be covered by the Games budget, such as non-business-as-usual costs for DTP and Victoria Police, onto other relevant departments and agencies.

From March 2023 DJSIR sought to:

- keep most of the funding approved in previous Games budget allocations for transport and security

- have most of the Games-related transport and police costs covered by separate funding bids from DTP and Victoria Police rather than from the Games budget.

Operating cost estimate for transport

Under the host contract, the state was responsible for providing Games-related transport to all participants, including spectators.

Transport expenses related to:

- providing a reliable, secure and efficient transport system for all participants, including spectators, athletes, officials, media, sponsors, the workforce and the Games family

- managing event traffic.

The March 2022 business case clearly said that the transport cost estimate was based on the government meeting the full costs of these expenses.

The business case also explicitly said that the cost estimate included DTP's expected costs for planning and supporting the Games.

DJSIR's business case indicated that the cost estimate considered transport-related issues associated with a regional multi-hub model. These issues included:

- longer travel distances

- limited accommodation in the regional areas, which meant that officials and media may need to travel to and from Melbourne

- buses would need to be brought from other locations to the hubs.

Both versions of the business case had the same operating cost estimate of $120 million for transport in the best and worst-case scenarios.

The government approved this estimate as part of the Games budget in March 2022. The Organising Committee allocated $48.2 million from this amount to cover transport costs for spectators and the Games workforce.

DJSIR changed its position on the estimate by mid-2023 and sought to:

- retain around $66 million from the Games budget allocation for transport to cover transport costs for athletes, officials and the Games family

- have the costs of transporting spectators and the Games workforce covered by a separate funding submission to the government of around $239 million from DTP.

This equated to a total transport budget of around $306 million, which was more than double the estimate in the business case and original approved budget.

DJSIR calculated the revised estimated budget using the same conceptual basis – net additional outlays.

DJSIR's advice to the government about the increased transport costs claimed that it was not appropriate to use the 2018 Gold Coast Commonwealth Games as a benchmark in the business case and to set the original budget due to the regional multi-hub model.

However, the business case clearly indicated that the multi-hub model had been considered when the cost estimates were developed.

The key reasons for the higher expected transport costs should have been foreseen when DJSIR developed the business case, including:

- the need to procure a very large volume of Games-specific bus services to supplement existing public transport services

- Victoria's franchise-based public transport system, which meant that the additional and extended public transport services needed to support the Games would require significant additional payments to franchisees.

Operating cost estimate for security and police

Security and police expenses were for providing police and private contractors for physical security, protecting assets, access control, public safety, and protecting athletes and VIPs during the Games to meet the state's obligations under the host contract.

Both versions of the business case had the same operating cost estimate of $219 million for security in the best and worst-case scenarios.

The business case said this estimate was based on the following assumptions:

- Costs for the Victoria Police would involve additional operational costs during the Games, including additional wages, allowances and accommodation costs, as well as the cost to set up and run security command centres.

- The state-funded salaries and on-costs of police working during the Games would be a normal or business-as-usual cost for Victoria Police and were not included in the Games operating expenses.

These assumptions indicated that the business case's cost estimate was developed on a net additional outlays basis where:

- the standard salary costs for police working during the Games were not funded from the Games budget but were a value-in-kind contribution by Victoria Police

- the Games budget would only meet the additional costs associated with allowances, travel and accommodation for police assigned to the Games.

The March 2022 version of the business case had attachments with advice on security and other issues from a consultant who specialised in major sporting and other events. The business case confirmed that the consultant was not a specialist in major event security planning.

The Games budget that the government approved in March 2022 was consistent with the business case. It included amounts for security that were intended to cover the additional costs for police officers assigned to the Games, including overtime, accommodation and meals and the non business-as-usual costs for Victoria Police command associated with supporting the Games policing response.

However, by mid-2023 DJSIR adopted a similar approach to the one it had for transport. It sought to:

- retain $142.7 million of the allocation in the original Games budget for security and police to use on private security

- have Games-related police costs covered by a separate and additional funding allocation of at least $300 million from the government for Victoria Police.

This approach was not consistent with the business case or the budget that the government approved in 2022. DTF raised this concern in advice to the government between April and July 2023.

The estimates of how much additional funding Victoria Police would seek ranged from $300 million to $358.6 million.

DTF's final estimate of $492 million for police and security costs included around $349 million for police. We have seen no evidence that the government formally considered a separate funding submission in relation to the Games from Victoria Police in 2023.

DJSIR's advice to the government in July 2023 indicated that the Victoria Police submission sought funding for:

- additional police and non-sworn Victorian Public Service FTE staff to form a dedicated Commonwealth Games command to design, develop and oversee the policing operation across 5 regional hubs

- costs associated with the command's operations

- regional hub infrastructure and logistical requirements

- information technology requirements to facilitate inter‐agency data sharing and counter surveillance capability to deliver the Games.