Operating Water Infrastructure Using Public Private Partnerships

Overview

From the late 1990s, water corporations used public private partnerships (PPP) to deliver a number of water and wastewater treatment infrastructure projects. PPPs provide an opportunity to achieve value for money by contracting the private sector to deliver and operate facilities over an agreed period, while managing contractually allocated risks.

This audit assessed the operational effectiveness of four PPPs:

- AQUA 2000 project—managed by Coliban Water

- Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme—managed by Coliban Water

- Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant—managed by Central Highlands Water

- Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant—managed by North East Water.

There are gaps in governance and contract management in all four audited projects. The effectiveness of the water corporations’ contract management varied, however, none could demonstrate a fully effective approach. Shortcomings in the water corporations' risk management, combined with a lack of board oversight, limits the board's assurance and visibility of the operational effectiveness of each project.

Of the four audited projects, only Central Highlands Water's contract administration for the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Project substantially complied with Partnerships Victoria requirements. However, there is scope for all water corporations to improve monitoring of service providers' financial health and broader project risks.

The failure to identify risks associated with the voluntary administration of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant service provider in 2012 demonstrated shortcomings in the contract management of the PPP, and in board and Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) oversight.

The Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant projects have been effective in providing a standard of service that matches the costs incurred. Coliban Water's decision not to reduce service payments for performance failures under its two PPP contracts undermines its ability to derive the services at the contracted standards and price. This, combined with a lack of reliable project benchmarking during the procurement phase and increased costs for its customers due to contract changes, means that Coliban Water is unable to demonstrate that its PPP projects have delivered value for money.

Operating Water Infrastructure Using Public Private Partnerships: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2013

PP No 248, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Operating Water Infrastructure Using Public Private Partnerships.

Water corporations have used the public private partnership (PPP) model to deliver a number of water and wastewater treatment infrastructure projects. This was done on the assessment that value for money would be achieved by contracting the private sector to design, build and operate facilities and manage specific risks.

This audit examined the operational effectiveness of four PPP projects covering water and wastewater treatment. In summary, it found that the effectiveness of each project was limited by gaps in governance and contract management and that only two projects have provided a level of service that matched the costs incurred.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

21 August 2013

Audit summary

Demand for reliable and high-quality water has increased in the face of population growth, changing water uses and a changing climate. Managing our water resources has prompted significant investment to augment water supplies and improve water use efficiency.

From the late 1990s, water corporations used the public private partnership (PPP) model to deliver a number of water and wastewater treatment infrastructure projects. PPPs provide an opportunity to achieve value for money by contracting the private sector to deliver and operate facilities over an agreed period, while managing contractually allocated risks.

At establishment, PPP project proposals are assessed on their ability to deliver value for money by comparing the proposal to a benchmark showing the most efficient form of public sector delivery. However, realisation of that value for money depends critically on effective governance, and contract and performance management throughout the contract. PPP projects must actually deliver what was intended for the agreed price. Demonstrating that a PPP project has achieved value for money relies on reconciling the intent against actual performance throughout the operational phase.

All but two of Victoria's 12 water and wastewater PPP projects have been operating for at least four years. Therefore, it is timely to examine the operational effectiveness of a selection of these projects and to assess whether value for money has been achieved.

This audit assessed the operational effectiveness of four PPP projects:

- AQUA 2000 project—managed by Coliban Water

- Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme—managed by Coliban Water

- Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant—managed by Central Highlands Water

- Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant—managed by North East Water.

Conclusions

There are gaps in governance and contract management in all four audited projects. The effectiveness of the water corporations' contract management varied, however, none could demonstrate a fully effective approach. Shortcomings in the water corporations' risk management, combined with a lack of board oversight, limits the board's assurance and visibility of the operational effectiveness of each project.

Of the four audited projects, only Central Highlands Water's contract administration for the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Project substantially complied with Partnerships Victoria requirements. However, there is scope for all water corporations to improve monitoring of service providers' financial health and broader project risks.

The failure to identify risks associated with the voluntary administration of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant service provider in 2012 demonstrated shortcomings in the contract management of the PPP, and in board and Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) oversight.

The Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant projects have been effective in providing a standard of service that matches the costs incurred. Coliban Water's decision not to reduce service payments for performance failures under its two PPP contracts undermines its ability to derive the services at the contracted standards and price. This, combined with a lack of reliable project benchmarking during the procurement phase and increased costs for its customers due to contract changes, means that Coliban Water is unable to demonstrate that its PPP projects have delivered value for money.

Findings

Governance

There are gaps in the quality and detail of information reported to the boards of each water corporation, which diminishes their ability to appropriately monitor the operational performance of each PPP project. The absence of sufficient oversight by water corporation boards around contract performance limits the boards' assurances that project risks are being managed effectively and value for money outcomes are being achieved.

The oversight provided by DTF and the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) has been minimal on the basis that the water corporation boards are ultimately responsible for contract performance. However, the effectiveness of this approach relies on the water corporation boards exercising sufficient oversight to identify, address and mitigate risks.

The 'arm's length' oversight that is performed each month by DTF has been poorly implemented. This contributed to the failure to identify risks associated with the voluntary administration of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant service provider, despite the framework clearly aiming to identify these risks.

Contract management

Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide was first published in 2003. It sets out expected steps to be taken for each PPP project. These steps cover a number of contract management areas including:

- contract administration

- risk management

- relationship management

- monitoring financial health of service providers.

The effectiveness of the water corporations' contract management varied, however, none could demonstrate a fully effective approach.

Each water corporation has a clear focus on managing each PPP using a range of tools and processes. Central Highlands Water has the most comprehensive approach to contract administration and performance monitoring. In contrast, despite its documented processes, Coliban Water's contract management has been less rigorous.

North East Water did not have an effective contract management approach due to an incomplete and outdated contract administration manual and inadequate arrangements for monitoring the financial health of its service provider.

Each project is supported by the responsible water corporation's corporate risk register. However, none of the water corporations have effectively monitored or managed project-specific risks, with only Coliban Water documenting these. This is at odds with Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide.

Each water corporation has regularly monitored its service provider's core service delivery, however, none have effectively monitored project-specific risks or the financial health of the provider. In particular, the lack of financial monitoring of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant service provider meant that North East Water was unprepared for the voluntary administration of the provider in mid-2012. Closer financial monitoring might have identified the need to review the adequacy of existing controls associated with this risk. Despite not having done so, North East Water, in consultation with DTF, has appropriately responded to the event.

Delivering services as intended

The Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant projects have substantially complied with contracted performance standards and have been paid in line with their performance.

Coliban Water has made full service payments on its two PPP projects, despite numerous instances of non-performance across both projects amounting to nearly $4.8 million in potential payment deductions over the three-year period reviewed. This reflects the board's preference from the early stages of the project only to pursue service payment reductions where noncompliance had significant consequences, or where the service provider's response was unsatisfactory. This set an early precedent for the contract's operating period that lowered the level of service provided without service payments being adjusted accordingly. In addition, it has potentially undermined the initial procurement where unsuccessful tender bids were based on delivering specified levels of service.

Change events during the operating phase of a PPP project should not diminish value for money outcomes or inappropriately transfer contracted risk. Changes under Central Highlands Water's and North East Water's PPP projects were managed satisfactorily, and each maintained the intended level of service. In contrast, Coliban Water's approach to managing PPP projects has led it to incur up to $64 million in unplanned costs under the AQUA 2000 project contract to address financial risks faced by the service provider. Coliban Water believes that it was necessary to incur these unplanned costs to ensure continued water supply during prolonged and unforeseen drought conditions. Nonetheless, this approach undermined its ability to achieve value for money under this contract.

Demonstrating achievement of value for money

Water corporations have not assessed whether the intended value for money of their PPP projects has been achieved during the operating phase. In part, this is because DTF does not provide support or guidance material on a best-practice approach to realising intended project benefits and assessing the value for money achieved throughout the contract operating period. A model that considers whether the cost of both quantitative and qualitative outcomes reflects value for money is needed.

Despite both the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant project and the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant project producing the expected level of service, only Central Highlands Water can demonstrate that its project remains on track to achieve value for money against the project's quantitative public sector benchmark. The other three projects were approved under an earlier, less developed PPP model that led to inconsistent and unreliable benchmarking during the procurement phase. This makes the assessment of value for money challenging.

Coliban Water could not provide sufficient evidence that reliable public sector comparators had been developed during the procurement phases of the AQUA 2000 project, and Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme.

Recommendations

- The water corporations should routinely and regularly report to their boards on contract performance, including:

- realisation of anticipated benefits

- financial performance

- effectiveness of risk management

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should improve its existing public private partnership project oversight regime in the water sector to address gaps in implementation and seek ongoing assurance that water corporation boards are effectively managing contract performance.

- The Department of Environment and Primary Industries should seek assurance that water corporation boards are effectively managing public private partnership contract performance.

- The water corporations should revise their contract administration manuals to comply with Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide.

- The water corporations should improve their risk management frameworks for each public private partnership project to systematically identify, mitigate and report on risks.

- Coliban Water should reconsider its approach to applying reductions in service payments for non-performance under the AQUA 2000 project and the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme contracts.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should develop a best‑practice approach to assessing value for money throughout the public private partnership contract operating period.

Submissions and comments received

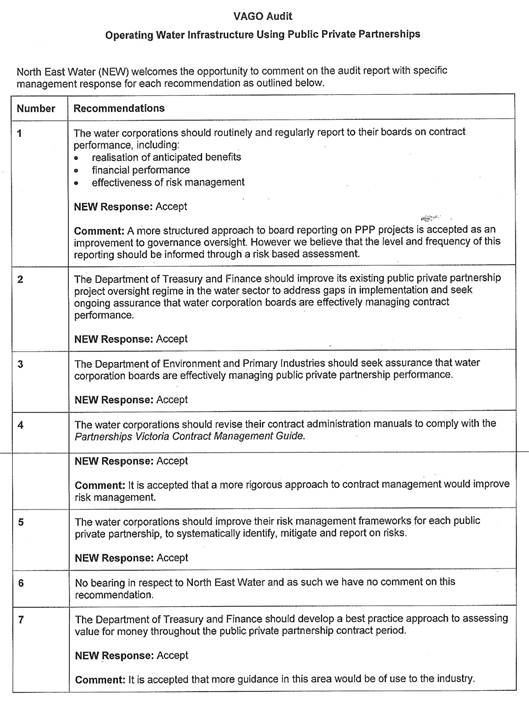

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to Central Highlands Water, Coliban Water, North East Water, the Department of Treasury and Finance, and the Department of Environment and Primary Industries with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Victorians should expect a reliable supply of water that is suitable for drinking, as well as industrial, agricultural and other domestic uses. With increasing demand for water and less certainty about natural supplies, governments have increasingly focused on approaches to better manage all water resources—rainfall, groundwater, wastewater and seawater.

Effective systems for ensuring water quality are those which deliver safe and reliable drinking water and minimise the human and environmental health risks associated with wastewater. In Victoria, meeting these demands has required significant investment over the past decade to augment water supplies and to use water more efficiently.

1.2 Water management in Victoria

Past challenges in meeting demand for water have resulted in an integrated approach to managing water resources in Victoria. This approach is reflected in the complex structure of Victoria's water sector.

Under the Water Act 1989, each of Victoria's 19 water corporations is responsible for water and wastewater treatment within their district. The facilities that perform this treatment must operate in a way that reduces risks to public and environmental health.

The water corporations are government owned with their boards appointed by the Minister for Water. Each water corporation is responsible for performing its functions as efficiently as possible—consistent with commercial practice—and reporting to the Minister for Water on performance via the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI).

Drinking water must be treated in compliance with the Australian Drinking Water Quality Guidelines and the Victorian Safe Drinking Water Act 2003, which is administered by the Department of Health.

Wastewater must be treated so that it can be reused or discharged in accordance with the Environment Protection Act 1970 and related Environment Protection Authority (EPA) guidelines. EPA licenses water corporations—and in some cases, a private provider—to control pollution. The licence sets the waste treatment, handling, discharge and disposal conditions, according to the type of operation conducted.

Under EPA guidelines, the Department of Health also has a role in assessing and endorsing schemes that involve treatment to a Class A recycled water standard, which is required for schemes where direct human contact with treated water is likely.

Special arrangements apply for managing stormwater, which is a shared responsibility between local governments and water corporations.

1.2.1 Water and wastewater treatment facilities

Water and wastewater treatment facilities are critical parts of the infrastructure required to deliver reliable and high-quality water for Victoria. Water treatment plants that produce drinking water remove contaminants from a raw water source so that it becomes fit for human consumption. Wastewater treatment plants remove contaminants from a raw water source so that it becomes fit for industrial, domestic or agricultural uses.

1.3 Use of public private partnerships in delivering water infrastructure

In alignment with government priorities in the late 1990s, regional water corporations undertook to deliver infrastructure projects to provide improved water supply and sewerage services. This led to increased use of the public private partnership (PPP) model to finance, design, build and operate new water and wastewater treatment facilities.

Under the PPP model, a private sector partner is contracted to manage specific risks and deliver improved services and innovation over the life of the project. The extent of private sector involvement varies between projects, for example the capital costs of some projects are privately financed, while under other projects the same costs have been financed publicly. Typically, around half of the costs of individual PPP projects fund the operation of the facilities over the lifespan of the partnership, which ranges from 10 to 25 years. PPPs are used when a government agency—in this case, the water corporation—can demonstrate that by assigning particular project risks and incentives to the private sector partner, the partnership is likely to deliver better value for money than could be achieved if the government carried out the project itself.

A PPP can be an effective way of delivering water infrastructure projects because it draws on the strengths of both the public and private sectors. However, realising these benefits is reliant on how well the services are delivered, whether risks are managed effectively and ensuring the costs for doing so are minimised. It also depends on having effective contracts, and contract management arrangements that ensure continued performance of the private providers.

Since 2000, water and wastewater treatment PPP projects have been delivered under the Partnerships Victoria framework. Since 2009 this framework has required compliance with the National Public Private Partnership Policy Framework, the National Public Private Partnership Guidelines and associated Partnerships Victoria requirements.

Non-metropolitan urban water corporations are exempt from the mainstream framework requirements for project development and approval, and instead follow a streamlined process. This recognises their status as government business enterprises and the lower cost of many of their projects. This exemption applies only to the procurement phase, not the operational phase, of PPP projects.

Excluding the much larger Victorian Desalination Plant project, the value of Victoria's 11 PPPs has totalled at least $450 million. Four of these projects are the:

- Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant—managed by Central Highlands Water, with the private sector partner upgrading and operating a wastewater treatment facility for 15 years. The project seeks to improve compliance with environmental regulations.

- AQUA 2000 project—which covers three water treatment plants and is managed by Coliban Water. The private sector partner was contracted to design, construct, finance and operate the plants located in Bendigo, Castlemaine and Kyneton over 25 years. The project seeks to improve water security and compliance with drinking water standards.

- Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme—also managed by Coliban Water. The private sector partner was contracted to design, build, finance and operate wastewater treatment facilities for 25 years. The project aims to improve compliance with environmental regulations.

- Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant—managed by North East Water. The project involved the upgrade and operation of an existing plant for 10 years, with the option of extending this operation over two five-year periods. The project aimed to provide increased capacity to manage domestic and trade wastewater. The contract was terminated in August 2012, after the voluntary administration of the plant's operator.

These projects cover both water and wastewater treatment services, and represent four of the five most expensive water PPPs that have been in an operational phase for at least four years. Summary details of these projects are set out in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Summary of four private public partnership projects

AQUA 2000 project |

Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme |

Ballarat North Water Reclamation Project |

Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Privately/publicly financed capital costs |

Private |

Private |

Public |

Public |

Year contract executed |

1999 |

2002 |

2006 |

2000 |

Year facility opened |

2002 |

2005 |

2008 |

2003 |

Initial operating period |

25 years |

25 years |

15 years |

10 years(a) |

Option for further operating period |

n/a |

n/a |

n/a |

2 x 5 years |

Estimated capital net present value at contract execution ($ mil) |

31 |

41 |

31 |

15 |

Estimated operational net present value at contract execution ($ mil) |

54 |

14 |

21 |

17 |

(a) The Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant contract was scheduled to end in 2013, but was terminated in 2012 after the service provider went into liquidation.

Note: Varied assumptions were used by water corporations to develop each project's estimated capital and operating net present values.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Under these four contracts, the water corporations pay the private sector partner monthly for the operation of the contracted facilities. These payments comprise fixed and variable components, with the variable component dependent on the volume of water received or treated. The contracts also provide water corporations with a mechanism to reduce the monthly payments if service standards are not met.

Excluding the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant, these contracts pre-date the introduction of Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide in 2003. However, the guide is still relevant and applicable to the management of each contract.

1.4 Responsibilities

1.4.1 Water corporations

The Partnerships Victoria framework gives the water corporations responsibility for managing and implementing PPP projects. In the operating phase, water corporations are responsible for establishing sound and effective contract management processes and achieving the project objectives.

1.4.2 Department of Treasury and Finance

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) manages the Partnerships Victoria framework. Under the framework, it has whole-of-government responsibility for:

- reviewing PPP project proposals to determine whether they represent value for money

- supporting and reviewing PPP projects, predominantly during the procurement phase

- monitoring and independently advising the Treasurer and Cabinet on significant contract management issues.

These responsibilities extend to providing guidance and support to contract managers during the operating phase of PPP projects. For example, DTF shares contract management knowledge across government and provides contract management training.

In May 2013 DTF published an update to the Partnerships Victoria Requirements to reflect lessons learnt, market feedback and reforms to the PPP model. These reforms include developing a streamlined procurement method for smaller scale PPP projects.

1.4.3 Department of Environment and Primary Industries

DEPI leads the sustainable management of Victoria's water resources. This includes implementing government policies and acting as a liaison between water corporations and the Minister for Water.

DEPI reviews business cases for water PPP projects during the procurement phase to determine whether proposals align with government policy. Operationally, water corporations must notify the minister, via DEPI, of any significant changes or problems they are facing regarding PPP projects.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to assess the operational effectiveness of the following projects:

- Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant—Central Highlands Water

- AQUA 2000 project—Coliban Water

- Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme—Coliban Water

- Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant—North East Water.

To address this objective, the audit examined the administrative practices of each of the above water corporations to determine whether:

- contracted services have been delivered as intended and represent value for money

- contractshave been managed effectively and are supported by sound governance.

The audit also examined the roles of DEPI and DTF during the operating phase of the selected PPP contracts.

The audit did not assess the procurement and construction phases of these projects.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Information analysed during the audit included:

- contracts, business cases and manuals relating to each project

- information reported on service provider performance from 2010

- board papers relating to each project

- forecast and actual expenditure

- contract management arrangements

- internalaudits and reviews.

Two consultants were engaged during the audit to provide expert advice on assessing the value for money achieved by a PPP.

The total cost of this audit was $335 000

1.7 Structure of the report

Part 2 of the report assesses the contract management and governance arrangements for each project, and Part 3 examines the delivery of contracted services.

2 Governance and contract management

At a glance

Background

Effective and efficient public private partnership delivery requires appropriate governance and a suite of strategies, plans and processes to support sound contract and performance management over the life the contract.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of water corporations' contract management varied. However, none could demonstrate a fully effective approach. Shortcomings in the water corporations' risk management, combined with a lack of board oversight, limited assurances on the operational performance of each project.

Findings

- Contract oversight by each of the water corporation boards is inadequate. There are also shortcomings in the Department of Treasury and Finance's oversight.

- Only Central Highlands Water's contract administration manual substantially complied with Partnerships Victoria requirements.

- The water corporations have sufficient information to measure compliance with water and wastewater treatment contractual standards.

- There are deficiencies in the water corporations' monitoring of service providers' financial health and broader project risks.

Recommendations

The water corporations should:

- routinely and regularly report to their board on public private partnership contract performance

- revise their contract administration manuals

- improve their risk management frameworks for each project.

The Department of Treasury and Finance should improve its oversight regime for operational public private partnerships in the water sector. The Department of Environment and Primary Industries should seek assurance that water corporation boards are effectively managing public private partnership performance.

2.1 Introduction

Public private partnership (PPP) contracts require governance arrangements that allow water corporation boards to understand whether project risks are being managed effectively, and intended benefits are being achieved.

Effective PPP contract management relies on having a suite of strategies, plans and processes to support achievement of the desired outcomes over the life of the contract. A contract administration manual is central to this, along with arrangements for managing specific areas such as monitoring performance, managing risks and improving relationships with the private sector partner.

This Part of the report assesses whether PPP contracts have been effectively managed and supported by sound governance.

2.2 Conclusion

The water corporations responsible for each of the audited PPPs have a clear focus on managing each contract using a range of tools and processes. Central Highlands Water has the most comprehensive approach to contract administration and performance monitoring, while Coliban Water's contract management practices lack rigour in their application.

North East Water did not have an effective contract management approach due to an incomplete and out-of-date contract administration manual, and inadequate arrangements for monitoring the financial health of its service provider.

None of the three water corporations have effectively managed project risks. There are also gaps in the quality and detail of project information reported to the boards of each water corporation. These gaps reduce the ability of the board to monitor the operational performance of each PPP project.

The oversight provided by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) has been limited and should be reviewed to ensure more effective management of these contracts.

2.3 Governance of water public private partnership projects

2.3.1 Governance roles of water corporation boards

The boards of the water corporations are accountable for their entity's performance, including for the delivery and operation of PPP projects. However, there is a lack of PPP project oversight by each board, limiting board assurances around risk management and the value for money achieved.

Water corporation boards need ongoing assurance that:

- PPP project risks are being managed effectively

- anticipated project benefits are being realised

- project costs are in line with original estimates.

Board reporting for each of the audited PPP projects provides insufficient detail to understand performance in these areas.

Coliban Water's and Central Highlands Water's monthly board reports highlight each facility's compliance with environmental and health requirements. Both water corporations also report certain matters to the board by exception, such as when change events require approval.

Reporting to the North East Water Board on the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant project occurred only when exceptional issues arose, which limited effective board oversight. This included when there was a request to change the plant's service provider in 2005 and when the replacement provider went into voluntary administration in May 2012. The voluntary administration of the service provider was caused by a separate legal dispute between the provider and a Queensland-based water company.

2.3.2 Governance roles of the departments of Treasury and Finance and Environment and Primary Industries

DTF and DEPI exercise minimal oversight of the operational performance of each PPP project on the basis that this is the responsibility of the water corporation boards. However, the effectiveness of this approach relies on the water corporation boards exercising sufficient oversight of contract performance to identify, address and mitigate against risks.

DTF performs an 'arm's length' oversight role of each project's operational performance, which has not been implemented effectively. This contributed to the failure to identify risks associated with the voluntary administration of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant's service provider, despite DTF's oversight regime clearly seeking to identify these risks.

DTF collects monthly reports from water corporations for individual PPP projects. The one-page reports serve as an assurance around service delivery, financial health and management quality of the service provider, as well as any other emerging risks.

There were weaknesses in DTF's implementation of this reporting regime that reduced its effectiveness:

- DTF had only collected two monthly reports from North East Water on the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant project beyond December 2004. DTF was not aware of this gap until mid-2012, when it was advised that the plant's service provider went into voluntary administration.

- The submission of monthly reports for the remaining three projects was not timely. Specifically, Coliban Water did not provide DTF with any monthly reporting for 2012 until October, while the majority of Central Highlands Water's 2012 reports were submitted in either July or November.

- DTF did not follow up on an unexplained performance issue in monthly reports regarding the AQUA 2000 project. In each report during 2012 Coliban Water had flagged contractual changes which increased the project's cost to government, but did not give an explanation for this.

Despite the flaws in its project oversight, DTF's response to the voluntary administration of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant's service provider in mid‑2012 was appropriate. DTF sought assurances that North East Water's preference to terminate the PPP contract and resume operational control of the plant was the most financially viable option, and then advised the Treasurer on how this issue was being addressed.

DEPI's involvement during the operational phase of water PPP projects is limited to being notified of significant operational issues, which complies with its A Governance Guide to the Victorian Water Industry. DEPI does not collect information on the operational performance of water corporations' PPP projects on the understanding that the Partnerships Victoria framework already does this.

2.4 Contract management arrangements

Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide was first published in 2003. It sets out expected steps to be taken for each PPP project. These steps cover a number of contract management areas including:

- contract administration

- risk management

- relationship management

- monitoringfinancial health of service providers.

2.4.1 Contract administration

Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide recommends that a contract administration manual be developed for each PPP project, comprising an up-to-date collection of all the tools and processes used in managing the contract.

The guide also requires a contract administration manual to identify:

- what needs to be done, by whom and when

- how the government's role will be performed

- the ramifications of any non-performance or default by the private party or government, and how these should be addressed.

Contract administration manuals were created for each of the four audited PPP projects. However, as shown in Figure 2A, only the manual for Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant project substantially met these requirements.

Figure 2A

Contract administration manual compliance with Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide

|

Requirement |

AQUA 2000 project (Coliban Water) |

Ballarat North Water Reclamation Project (Central Highlands Water) |

Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme (Coliban Water) |

Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant (North East Water) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

What needs to be done, by whom and when |

||||

|

Assigns obligations and accountabilities |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

P |

|

Describes how the contractor's performance will be monitored |

P |

Yes |

P |

Yes |

|

How the government's role will be performed |

||||

|

Identifies the resources, delegations and authorisations required for the water corporation to meet its obligations |

P |

P |

P |

P |

|

Ramifications of any non-performance or default by the private party or government, and how these should be addressed |

||||

|

Identifies contingency plans |

P |

Yes |

P |

No |

|

Identifies issue and dispute resolution mechanisms |

P |

Yes |

P |

No |

|

Additional requirements |

||||

|

The manual is reviewed and updated regularly |

P |

Yes |

P |

No |

Note: Yes indicates aspects of the manual that are fully compliant with Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide.

P indicates aspects of the manual which are partly compliant.

No indicates aspects that are not compliant.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Each of the four manuals had information about the resources, delegations and authorisations required to meet contract management obligations, but all lacked the detail necessary to be fully compliant.

Unlike the contract administration manual for the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant project, manuals for the AQUA 2000 project and the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme—both managed by Coliban Water—lacked detailed descriptions in key areas such as change and issue management and end-of-term arrangements.

Central Highlands Water and Coliban Water specified regular reviews of their manuals, however, only Central Highlands Water adhered to its review schedule. While Coliban Water's manuals were reviewed in March 2012, they still do not accurately reflect how the service provider's performance is monitored in practice. For example, the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme manual requires that Coliban Water and the service provider meet on a monthly basis to discuss operational performance, however, in practice these meetings occur only twice a year.

North East Water's manual for the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant did not meet good practice. The manual was never completed after a draft was prepared in 2004. Some sections remain empty or incomplete, including sections on contingency plans, change management and dispute resolution.

By not having a complete and up-to-date contract administration manual, North East Water has limited the ability of involved staff to:

- fully understand how both parties' contractual obligations should be applied—this gap is made more significant by the fact that there have been five changes in project director since the manual was drafted

- demonstrate to the board and other stakeholders that its contract management approach is effective.

2.4.2 Risk management

Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide recommends that contract managers identify, monitor and manage risks over the life of a PPP project.

None of the three water corporations has effectively managed project risks in a systematic manner.

Each project is supported by its respective water corporation's corporate risk registers. These registers identify the high-level risks relating to each project which include failure of key assets, poor service delivery, contract termination and natural events.

In addition to its corporate risk register, Coliban Water has documented project-specific risks for the AQUA 2000 project and the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme, along with internal controls for each. However, this added little value to Coliban Water's contract management because it has not systematically monitored the risks it identified.

Risks specific to the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant have not been adequately identified or managed. Specifically, Central Highlands Water and North East Water have not systematically documented or monitored project-level risks for their respective projects.

Central Highlands Water is now reviewing how it identifies and systematically manages project-specific risks.

2.4.3 Relationship management

Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide recommends that the government agency adopts ways of assessing the quality of the relationship with the private sector partner. The guide also recommends that clear processes for resolving disputes are established.

Water corporations' approaches to relationship management have varied. Nevertheless, each has maintained satisfactory working relationships with their respective service providers. These have been underpinned by sound arrangements for dealing with formal disputes.

Maintaining the health of the partnership

Figure 2B details each water corporation's arrangements for maintaining the health of the partnership.

Figure 2B

Water corporations' measures for maintaining partnership health

|

Project |

Measure |

|---|---|

|

AQUA 2000 project and Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme (Coliban Water) |

|

|

Ballarat North Water Reclamation Project (Central Highlands Water) |

|

|

Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant (North East Water) |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Each water corporation relies on monthly operations meetings and day-to-day contact with service provider staff to manage the health of the partnership. Coliban Water and Central Highlands Water have supplemented these arrangements with additional measures to manage relationships strategically. However, in each case the relationship between the water corporation and the service provider was reasonably effective.

Coliban Water also requires both parties under the AQUA 2000 project and Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme contracts to jointly survey the state of the relationship on a quarterly basis. While the relationship management approach described in Coliban Water's contract administration manuals is the most comprehensive, its effectiveness has been diminished by poor implementation. Specifically:

- operations meetings for the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme have occurred only twice a year, rather than monthly

- steering committee meetings have occurred quarterly for the AQUA 2000 project but never in relation to the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme

- the partnership surveys for the AQUA 2000 project showed that the relationship was sound, however, surveys for the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme have not been conducted.

Dispute resolution

Each contract contains reasonable processes for resolving disputes via dispute panels, expert determination or arbitration. These processes were triggered under the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant contract in 2009, after Central Highlands Water had refused to pay the service provider for additional costs claimed as part of the wastewater treatment process. The dispute was commercially resolved following meetings of the dispute panel with advice from technical experts, and Central Highlands Water did not incur any additional operational costs.

Formal dispute resolution mechanisms have not been triggered under the AQUA 2000 project, Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme or the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant project.

2.4.4 Monitoring service providers' financial health

Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide recommends that agencies monitor their service providers' cash flows and financial health, including information on financial statements, dividend payments and audited accounts.

Central Highlands Water and Coliban Water have arrangements in place to monitor the financial health of the service provider. However, neither has followed the arrangements described in their contract administration manuals:

- Central Highlands Water required a range of half-yearly and yearly financial information from the service provider, yet it has not collected any half-yearly financial information since the commencement of the contract. In addition, the service provider failed to publish an annual report in 2010, limiting Central Highlands Water's checks on the service provider's financial health. Central Highlands Water's review of the service provider's 2011 and 2012 annual reports was satisfactory.

- For both of its projects, Coliban Water required an expert review of the service provider's annual report along with a company search, and review of company controllers and stock exchange announcements.Neither of these has occurred.

North East Water had inadequate systems in place for monitoring the financial health of the service provider for the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant project. The dispute—between the service provider and a Queensland-based water supplier—that triggered the provider going into voluntary administration in May 2012 had been 'long‑standing' according to its 2011 annual report.

North East Water advised that the risks associated with a lack of financial monitoring were 'relatively low' because the level of private financing under the contract was small. However, this reasoning did not consider the risks associated with:

- potentially receiving a lower level of service from the service provider once it went into voluntary administration

- outstanding payments to local suppliers and sub-contractors.

The lack of monitoring of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant's service provider's financial health by North East Water is particularly significant as it was left unprepared for the voluntary administration of its service provider in 2012. Better financial monitoring would have identified this issue and enabled it to review the adequacy of existing controls associated with the above risks.

2.5 Performance monitoring regimes

Being assured that a PPP project is operating effectively requires the water corporation to regularly monitor important aspects of performance, including whether:

- core services are being delivered to the contracted standard

- the condition of assets is being managed effectively.

The three water corporations' performance monitoring provides sufficient information to assess whether water and wastewater treatment complies with contract standards. However, none can demonstrate fully effective regimes due to uncertainty about the quality of service providers' asset management frameworks.

2.5.1 Monitoring core service delivery

Water corporations monitor operational performance under each contract through monthly reports from the service provider that detail compliance with service standards and eligibility for service payments. This monthly reporting arrangement has been followed as intended under each contract and provides a satisfactory account of operational performance.

North East Water's validation of monthly performance reports from the service provider was less robust than that of Central Highlands Water and Coliban Water. Specifically:

- Coliban Water and Central Highlands Water had performed and documented satisfactory checks on the accuracy of the service providers' monthly performance reports and invoices.

- North East Water claims that sufficient checks on the accuracy of the service provider's performance information occurred through monthly discussions with the provider. Records of these discussions provide minimal evidence of these checks. As a result North East Water cannot demonstrate that it adequately validated performance information and invoices submitted.

2.5.2 Monitoring asset management

The monthly reports from each service provider show that regular maintenance of contracted facilities has occurred, however, doubts exist about the effectiveness of these activities.

Water corporations collect a range of additional information to verify that assets are being maintained as required under the contract. For example, Coliban Water and North East Water each receive annual condition reports for contracted facilities from their service provider, while Central Highlands Water receives annual updates to the service provider's asset management plan and requires an independent facility condition assessment every five years, the first of which is due to occur later in 2013.

These arrangements are useful and are supported by contract provisions obliging the service provider to return the assets in an agreed condition at the end of the contract period. However, doubts remain about the quality of service providers' asset management frameworks:

- North East Water commissioned a detailed condition assessment of the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant in August 2012 as part of the handover of the plant. While the assessment found that the plant was in reasonable condition, it also found that maintenance activities were not systematic but rather appeared to have been targeted on an ad hoc basis. North East Water maintains that the service provider's asset management approach was sound, although it acknowledges that there was a drop in maintenance activity at the plant after the service provider went into voluntary administration.

- Coliban Water cited concerns regarding the extent to which the AQUA 2000 project's service provider's asset management framework aligned with its own practice. It is now working with the service provider to better understand the framework and how it compares with Coliban Water's own approach.

- Central Highlands Water has noted that the service provider's asset maintenance spending regularly exceeds the forecast amount, potentially indicating gaps in its assessment of asset condition. These additional costs have been borne by the service provider. Central Highlands Water believes that there may be other reasons for this discrepancy, but is unable to provide evidence in support of this claim.

2.6 Monitoring and improving contract management

Central Highlands Water and Coliban Water have processes in place to regularly assess their contract management approaches. Reviews for the AQUA 2000 project, for example, have assessed project alignment with business needs, identified the need to improve aspects such as dispute resolution and contract management, and tracked progress in implementing improvements. North East Water has not reviewed its contract and project management approaches, limiting its opportunities to assess the value of the project and implement continuous improvements.

Only Coliban Water has used its internal audit programs to specifically assess the management of its contracts in practice. These internal audits identified areas for improvement around financial management and contract administration. Coliban Water has responded satisfactorily to these issues.

Recommendations

- The water corporations should routinely and regularly report to their boards on contract performance, including:

- realisation of anticipated benefits

- financial performance

- effectiveness of risk management.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should improve its existing public private partnership project oversight regime in the water sector to address gaps in implementation and seek ongoing assurance that water corporation boards are effectively managing contract performance.

- The Department of Environment and Primary Industries should seek assurance that water corporation boards are effectively managing public private partnership contract performance.

- The water corporations should revise their contract administration manuals to comply with Partnerships Victoria's Contract Management Guide.

- The water corporations should improve their risk management frameworks for each public private partnership project to systematically identify, mitigate and report on risks.

3 Achieving intended outcomes

At a glance

Background

Public private partnership (PPP) projects should deliver what they were intended to, and continue to demonstrate value for money throughout their operation.

Conclusion

Water and wastewater treatment services in the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant projects have largely complied with the contracted key performance indicators (KPI). Coliban Water has continued to make full service payments for its PPPs despite failures to meet KPIs, meaning that it has paid for a level of service that was not delivered. Coliban Water has also allowed changes under the AQUA 2000 project that have further undermined the value for money achieved.

Water corporations have not attempted to assess whether value for money has been achieved in their respective PPPs.

Findings

- Contracted services for the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant projects have been delivered as intended.

- Coliban Water did not pursue reductions to service payments for numerous noncompliances.

- There is no agreed approach to retrospectively assessing whether a PPP has achieved its intended value for money.

- Coliban Water's decisions to allow changes to its AQUA 2000 project contract means its customers will incur up to $64 million in additional costs.

Recommendations

- Coliban Water should reconsider its approach to applying reductions in service payments for non-performance.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should develop a best‑practice approach to assessing value for money throughout the public private partnership contract operating period.

3.1 Introduction

Like any contract, public private partnership (PPP) contracts are beneficial when they lead to the services being delivered as intended, at or below the agreed price.

PPP contracts contain performance standards that the service provider must meet to be eligible for the full service payment. If managed effectively, this arrangement gives the service provider the continued incentive to provide a desired level of service.

Achieving value for money is a key requirement of a PPP. Tracking value for money during the operating phase requires an understanding of how the outcomes achieved compared against the contract and the original project proposal, which should include a robust public sector benchmark.

This Part assesses whether services have been delivered in a way that meets contractual requirements and achieves value for money outcomes.

3.2 Conclusion

The water corporations have not attempted to assess whether value for money has been achieved in their respective PPP projects.

There is no agreed best practice approach to assessing whether a PPP project achieves the value for money intended. The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) does not provide support or guidance material on a best-practice approach to realising intended project benefits and assessing the value for money achieved throughout the contract operating period.

The Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant project and Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant project have substantially complied with contracted performance standards and have been paid in line with their performance. Events that have required changes to the PPP contracts have been managed appropriately and maintained the intended level of service.

Despite numerous instances of its two PPP projects not meeting core service key performance indicators (KPI), Coliban Water has made full service payments to them. Coliban Water has therefore paid for a level of service that it has not received, which has undermined the purpose and effectiveness of its KPI regimes. Coliban Water has also allowed changes under the AQUA 2000 project that have led it to incur up to $64 million in unplanned costs, despite the contracts making the service provider responsible for bearing these. This approach undermines the value for money achieved and diminishes the integrity of the original tender processes that established service levels and risk allocations.

3.3 Establishing public private partnership service levels

The ability to effectively deliver a PPP project depends on establishing contracts with mechanisms that drive performance to the desired standard and cost at the commencement of the project.

Each of the contracts for these four PPPs contained KPIs that, where not met, enabled the water corporation to reduce the contract payments to be made to the private sector partner. These included KPIs relating to water or wastewater treatment quality and quantity, some of which exceed the relevant environmental and health regulations. Figure 3A outlines the coverage of KPIs in each PPP contract that could trigger payment reductions.

Figure 3A

Coverage of contract key performance indicators that are linked to service payment reductions for non-performance

|

Performance area |

AQUA 2000 project (Coliban Water) |

Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme (Coliban Water) |

Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant (Central Highlands Water) |

Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant (North East Water) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Core service |

||||

|

Water/wastewater treatment quality and quantity |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Compliance with relevant laws and authorisations |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Non-core service |

||||

|

Delivery of maintenance |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

Presence of quality assurance systems |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

Handling of complaints |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

|

Adhering to monitoring and reporting requirements |

Yes |

Yes |

|

|

Note: This audit has examined KPIs that, where not met, trigger the right to reduce service payments for non-performance.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Only the AQUA 2000 project and Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme contracts contain KPIs in areas other than water quality and quantity, such as maintenance performance and handling of complaints.

While the ability to reduce service payments for failure to meet KPIs provides effective performance incentives, other contract provisions are available to be used to drive improvements in areas not covered by KPI regimes. For example, failure by the service providers of the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant to meet contractual requirements regarding maintenance could trigger a default.

3.4 Delivering the required service levels

Service providers for the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant and the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant have received service payments in accordance with their performance against contractual requirements.

In contrast, numerous noncompliances reported across Coliban Water's two projects have not led to any reductions in service payments. This approach was based on an assessment that the associated health and environmental impacts were insignificant. This undermines the value the contract provisions envisaged when the service levels and risk allocations were established and agreed to. Ultimately, Coliban Water has paid for a level of service that has not been provided.

Figure 3B compares service delivery across the four audited projects over the past three operational years, and the abatements applied for non-performance.

Figure 3B

Summary of reported contract noncompliances and payment reductions applied over the past three operational years

|

AQUA 2000 project (Coliban Water) |

Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme (Coliban Water) |

Ballarat North Water Reclamation Project (Central Highlands Water) |

Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant (North East Water) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Number of noncompliances reported |

74 |

5 |

5 |

– |

|

Number of payment reductions applied for non-performance |

– |

– |

5 |

– |

|

Total amount of payment reductions |

– |

– |

$173 238 |

– |

|

Total value of forgone payment reductions |

$3 573 161 |

$1 180 725 |

– |

n/a |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.4.1 AQUA 2000 project—Coliban Water

The AQUA 2000 project service provider failed to meet service delivery KPIs during all but three months of the three-year period reviewed. These failed KPIs included:

- 27 months with low chlorine residual levels

- 18 months with noncompliant pressure levels

- 11 months with high turbidity levels

- 10 months with high levels of total coliforms

- three months with low alkalinities recorded

- three months with noncompliant colour samples

- one month with noncompliant storage levels

- one month with low pH results.

Despite being able to reduce service payments by nearly $3.6 million due to these failures to meet KPIs, Coliban Water did not pursue any reductions in service payments, paying the full amounts to the service provider during this period.

The water treatment KPIs for the AQUA 2000 project are more stringent and numerous than the Victorian Drinking Water Quality Standards. This allows the water corporation to identify issues with water quality before they trigger notifications to the Department of Health. It also increases the likelihood that contract KPIs will remain relevant and appropriate if future changes to health regulations are made.

Coliban Water's documented reviews of the service provider's monthly performance reports and invoices assessed the risks associated with the noncompliances as minimal, and therefore did not pursue payment reductions. This reflects the water corporation board's preference only to pursue reductions where noncompliances had significant consequences, or where the service provider's response was unsatisfactory.

Importantly, the board's preference was adopted in August 2003, approximately one year after the project's operational phase commenced. This set a precedent at an early stage of the contract's operating period that lowered the level of service provided without service payments being adjusted accordingly. It also failed to recognise that in setting the abatement regime the materiality of these noncompliances had already been considered. This is reflected in the contract's payment reduction rates for these being set between 5 and 25 per cent.

Despite not representing a risk to water users, the failures to meet KPIs without any payment deductions reflects a loss of value that would otherwise be achieved under the contract. In addition, this has potentially undermined the initial procurement where unsuccessful tender bids were based on delivering specified levels of service.

Consequently, Coliban Water needs to reconsider the basis on which it determines when full service payments should be made. Ultimately this may require adjustments to the performance standards and/or the prescribed payment reduction rates.

3.4.2 Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme—Coliban Water

The service provider failed to meet contract KPIs in relation to Escherichia coli (E. coli) and total phosphorus levels in mid-2011. Much like the noncompliances reported under the AQUA 2000 project, Coliban Water assessed the risks arising from these noncompliances as low, on the understanding that:

- the noncompliant E. coli levels had no impact on the project's compliance with the Environment Protection Authority's standards for Class B recycled water

- investigations of the noncompliant total phosphorus levels revealed no environmental impacts to surrounding land.

In line with the board's preference, Coliban Water did not pursue any reductions in service payments for these five noncompliances, which would have totalled nearly $1.2 million in payment deductions. This decision is at odds with the severity of corresponding payment reduction rates under the contract, which warranted a 50 per cent monthly payment deduction for each of the five reported noncompliances.

The service provider has met contract KPIs since these noncompliances were reported. However, the lack of reductions to service payments for non-performance provides further evidence that Coliban Water has paid for a level of service that was not delivered and this undermines the original procurement.

3.4.3 Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant—Central Highlands Water

Five separate reductions in service payments for non-performance were applied under the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant contract during late 2009, when the service provider exceeded discharge limits for total nitrogen and ammonia. In accordance with the contract, the service provider's monthly service payment was reduced by 20 per cent for each noncompliance and collectively totalled $173 237.79.

Since reductions were applied in late 2009, the service provider has reported full compliance with contract KPIs and environmental regulations.

3.4.4 Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant—North East Water

The service provider for the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant reported full compliance with service delivery KPIs over the three-year period reviewed. As a result reductions in service payments were not required.

3.5 Demonstrating the achievement of value for money

There are two dimensions of value for money for PPP projects.

As infrastructure projects, the value for money of PPP projects is established in a business case which makes various forecasts and assumptions for factors such as water demand, effective capacity to supply water, rainfall, water prices, financing costs and required maintenance. Throughout a project's operational phase, these forecasts and assumptions can be tested against actual outcomes to verify if value for money is still being achieved.

Additionally, under the Partnerships Victoria framework, a PPP project quantitatively achieves value for money if the successful tender bid is priced below the project's public sector comparator (PSC). The PSC is an estimate of the total whole-of-life cost of public sector delivery, taking into account the likelihood and consequences of all potential project risks that may occur. Value for money is considered to be likely where a private sector provider is able to manage certain risks more efficiently than the public sector agency.

This comparison is made during the procurement phase, along with consideration of other qualitative factors such as the successful tenderer's expertise and innovative practices. Value for money throughout the operational phase depends on delivery of services to the required levels, whether the risk allocation is maintained as intended, and how changes to contracts are managed.

Overall, value for money in PPP projects is more complex to demonstrate in the operational phase. This is because an external event—such as a drought—does not itself affect the value for money, but may indicate whether the risk of the event was appropriately estimated and allocated to the most appropriate party.

The water corporations have not attempted to assess whether value for money has been achieved in their respective PPP projects. In part, this is because there is no agreed best-practice approach to assessing the value for money in a PPP other than during the procurement phase. DTF does not provide support or guidance material on best-practice approaches to realising intended project benefits and assessing the value for money achieved throughout the contract operating period. There is a need for a model that considers whether the cost of both quantitative and qualitative outcomes during the operating period reflects value for money.

However, even with an agreed approach, it is difficult to determine whether the intended value for money has been achieved for the AQUA 2000 project, Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme and the Wodonga Wastewater Treatments Plant projects. This is because each of these projects was approved under an early version of the PPP model that contained less material to support the development of a robust business case and PSC. Only Central Highlands Water can demonstrate that its project remains on track to achieve value for money against the project's quantitative public sector benchmark.

Coliban Water could not provide sufficient evidence to show that reliable PSCs had been developed during the procurement phases of the AQUA 2000 project and Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme. The likelihood of achieving value for money is also eroded by Coliban Water not holding service providers to their contracted service levels and by its approach to managing contract changes.

3.6 Responding to change

Achieving a project's intended outcomes and delivering value for money are affected by unforeseen events that arise during a contract. Effective change management is essential due to the long-term nature of a PPP contract. It is important that any change does not diminish value for money outcomes or inappropriately transfer allocated risk back to the state.

The contracts for each of the projects had provisions that enabled the authorisation and implementation of changes during their operational phases. Figure 3C shows the change events that have occurred during the operational phase of each contract.

Figure 3C

Change events during the operational phase of each project

|

Project |

Change |

|---|---|

|

AQUA 2000 project (Coliban Water) |

2005—modified service payment calculation methodology 2010—modifications to enable treatment of water from a new source and achieve improved manganese standard |

|

Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme (Coliban Water) |

2013—scheme connection to the Rochester system |

|

Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant (Central Highlands Water) |

2012—allowance for re-use of biosolids for agricultural purposes |

|

Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant (North East Water) |

2005—change in service provider 2004-05—minor modifications to points of supply and influent pipe sections 2012—termination of contract following the voluntary administration of the service provider |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.6.1 AQUA 2000 project—Coliban Water

Coliban Water's approach to managing PPPs has resulted in it incurring up to $64 million in unplanned costs under the AQUA 2000 project contract. It intends to pass these costs onto customers over time.

The first change occurred in 2005, when Coliban Water agreed to modify the contract's service payment calculation methodology to address increasing risks raised by the service provider about its financial sustainability. These risks resulted from a combination of:

- the ownership of the service provider changed immediately prior to the contract being signed in 1999, leading to the adoption of a more risk averse and expensive water treatment process

- the effects of drought on volumes of water treated, leading to lower than expected service payments.

This change was supported by board papers that considered two treatment options, including a 'do nothing' approach. Coliban Water considered that refusing to adjust the methodology would increase the risk of the service provider withdrawing from the contract. The change added approximately $52 million in service payments over the life of the contract.

In addressing these risks Coliban Water had failed to consider other potentially viable and cost-effective solutions. For example, no consideration had been given to negotiating an outcome that was more favourable to Coliban Water, or making a counter-offer.

The second change occurred in 2010, when Coliban Water and the service provider agreed to a series of facility modifications to address risks around untreated water quality that were contractually allocated to the provider. Specifically, the completion of the Goldfields Superpipe project in 2008 had unexpectedly brought a more variable quality of untreated water into the Coliban system, making water treatment more costly than expected.

Board papers informing this change showed that Coliban Water expected to contribute nearly $12 million towards the works on the basis that these risks could not have been foreseen by the service provider. This outcome represents a significant divergence from the contract, which allocates risks relating to untreated water solely to the service provider. Importantly, the contract states that 'Raw Water means water from any surface water catchment in any combination'. This definition gives Coliban Water the ability to input water from any surface water catchment, and brings into question its decision to contribute funding towards the works.

Coliban Water believes that its decision to incur additional costs in response to these two change events was necessary to ensure the continued supply of drinking water during a period of severe drought that could not have been reasonably foreseen.

Coliban Water also believes that the additional costs are offset by approximately $60 million invested by the service provider to address the same issues. However, it could not provide sufficient evidence to verify the service provider's investment. Additionally, this rationale does not consider the possibility of the service provider bearing all the additional costs in accordance with the original contract. In any event, Coliban Water's approach undermined its ability to achieve value for money.

3.6.2 Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme—Coliban Water

The only change event for the Campaspe Water Reclamation Scheme involved connecting the scheme to the Rochester Wastewater Treatment Plant to improve the plant's compliance with the Environment Protection Authority regulations. While this upgrade was detailed in the contract, it did not prescribe its costs. This reflected Coliban Water's preference to retain the flexibility to fund and deliver the upgrade as required. Accordingly the contract had been structured in a way that allowed the costs to be incorporated at a later date.

In December 2012, the Coliban Water board approved a proposal to provide $9.3 million to deliver the upgrade. The board also approved an increase in annual service payments to the service provider of $164 000 to cover the increased operational costs arising from the works. In July 2013, Coliban Water and the service provider contractually agreed to commence the upgrade works.

The value for money impacts of this change remain unclear due to a lack of evidence showing that a reliable PSC was in place at the procurement phase. As such, Coliban Water's claim that the project remains on track to cost less than the associated PSC cannot be verified.

3.6.3 Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant—Central Highlands Water

The single change event for the Ballarat North Water Reclamation Plant project allowed the service provider to re-use biosolids produced for agricultural purposes. It had no impact on the contract's service delivery obligations and payment arrangements. Board papers relating to this change show that it was adequately documented and appropriately authorised.

3.6.4 Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant—North East Water

North East Water responded appropriately to two significant change events under the Wodonga Wastewater Treatment Plant contract.

In 2005 the service provider requested permission to transfer operational control of the plant to a third party, after the provider's parent company decided to scale back its international operations. Before approving this request, North East Water sought assurance that the replacement service provider had the necessary technical and financial capacity, and that risk allocation would not be affected.

North East Water was unprepared for the voluntary administration of the plant's replacement service provider in 2012. Despite this, North East Water's response was appropriate and included:

- successfully negotiating with the service provider to honour its contractual obligations—at a reduced cost to North East Water—while a long-term solution was investigated

- considering the merits of a series of solutions before deciding to assume operational control of the plant