Integrated Transport Planning

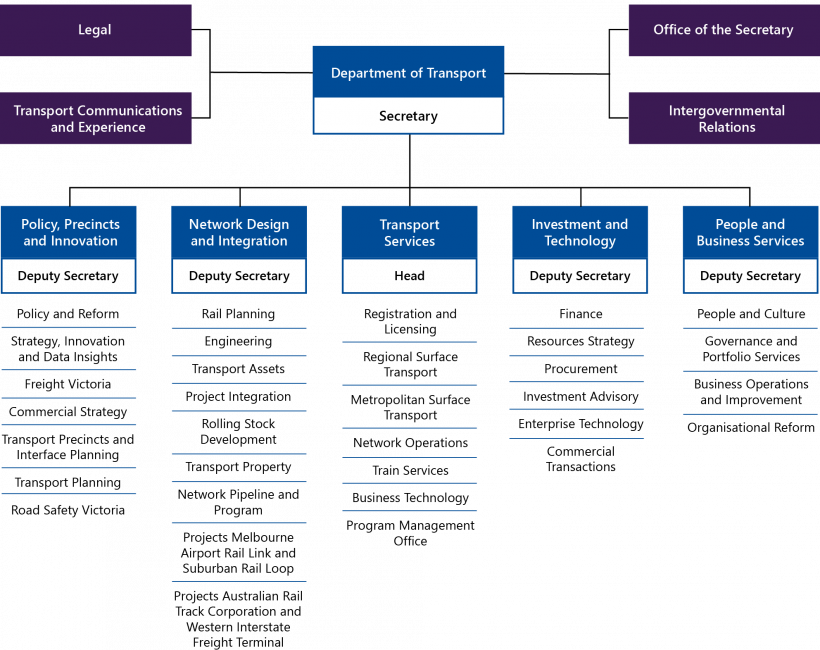

Snapshot

Is the Department of Transport (DoT) demonstrably integrating its transport planning?

Why this audit is important

The Transport Integration Act 2010 (the Act) requires DoT to prepare and periodically revise the transport plan for Victoria.

The Act seeks integrated planning and management of the many transport modes, networks and services that make up the state's transport system, so they best meet user needs.

Who and what we examined

We examined whether DoT:

- meets the Act's requirements for the transport plan

- is integrating its transport planning.

What we concluded

DoT and its predecessors have not, over the past decade, demonstrably integrated transport planning and are yet to meet the Act’s requirements for the transport plan.

Since DoT’s establishment in 2019 though, it is evidently committed to realising these aims, and is making steady progress towards them.

However, DoT’s assertion that its 40 separate plans and strategies presently meet the Act's integrated transport plan requirements does not withstand scrutiny.

The absence of a transport plan as required by the Act, during a decade of unprecedented investment in transport infrastructure, creates risks of missed opportunities to sequence and optimise the benefits of these investments to best meet Victoria's transport needs.

What we recommended

We made seven recommendations to DoT, covering:

- improved transparency for the current transport plan

- establishing completion timelines for plans in development

- completing Victoria's Living Transport Network framework and related guidance

- focusing on governance and leadership to deliver integrated transport planning

- advice to government on transport investment priorities needing to reflect the results of integrated planning.

Video presentation

Key facts

What we found and recommend

We consulted with DoT and considered its views when reaching our conclusions. DoT's full response is in Appendix A.

Victoria's Integrated Transport Plan

Compliance with the Transport Integration Act 2010

The Act requires DoT to prepare and periodically revise the transport plan for Victoria. It specifies mandatory content and considerations for this plan, as Figure A sets out.

FIGURE A: Legislative requirements of the transport plan

| Transport plan requirements specified in Section 63 of the Act |

|---|

| Sets the planning framework for transport bodies to operate in |

| Sets out the strategic policy context for transport |

| Includes medium or long-term strategic directions or actions |

| Prepared with regard to the Act’s vision statement, transport system objectives and decision-making principles |

| Prepared with regard to national transport and infrastructure priorities |

| Demonstrates an integrated approach to transport and land-use planning |

| Identifies the challenges the transport plan seeks to address |

| Includes a regularly updated short-term action plan |

Source: VAGO, from the Act.

DoT asserted to Parliament and to VAGO that it meets the Act's requirements through multiple plans and strategies taken together, rather than in a single transport plan. In advice to the Parliament's Public Accounts and Estimates Committee (PAEC) in June 2019, DoT listed 11 published documents as evidence of its integrated transport planning work, and as part of the transport plan required by the Act.

An integrated transport system provides users with convenient access to timely, efficient services that are coordinated and linked within and across transport modes for seamless and reliable end to end journeys.

We assessed these 11 published documents and a further 21 documents that DoT identifies as part of the transport plan against the specific requirements of section 63 of the Act. The documents we assessed comprise:

- two broad whole-of-government plans relevant for transport: Plan Melbourne, Metropolitan Planning Strategy (2017) and the Victorian Infrastructure Plan (2017)

- 18 plans for specific transport modes including train, tram, bus, road and cycling

- nine location-specific plans covering regional Victoria and two of six metropolitan Melbourne sub regions

- three miscellaneous plans and strategies.

We could not assess more than 10 other plans and strategies DoT identifies as part of the transport plan as it is yet to finalise them.

The documents DoT identifies as comprising the transport plan do not fully meet legislative requirements. This collection of documents does not provide a coherent and comprehensive transport plan because:

- the plans have been developed over a nine-year period and do not explain or demonstrate how they are part of a collection of documents that form the transport plan as required by the Act, or how they are related to, link with, or build on other plans

- the collection is yet to include completed plans that address all areas of Victoria and all transport modes

- modal plans were largely developed before, rather than after, area-based plans, which runs counter to integrated planning principles and is inconsistent with national transport planning guidance

- individual plans are highly varied in detail and focus, ranging from high-level strategies to single-mode or location-based plans and policy documents communicating initiatives underway or committed to.

A modal plan is a plan for a particular mode of transport, while an area-based plan should consider all modes of transport in a certain area.

The absence of the transport plan as required by the Act during a decade of unprecedented investment in transport infrastructure creates risks:

- of missed opportunities to sequence and optimise the benefits of these investments to meet Victoria's transport needs

- that DoT's day-to-day operational decisions are narrowly focused and perpetuate the lack of integration in the state's transport system.

DoT is also not complying with the requirement in the Act that the transport plan have a short-term action plan that it regularly updates. Of the 32 plans we assessed, 15 do not include a short-term action plan.

The Act also requires the DoT Secretary to provide the transport plan to the Minister. DoT could only provide evidence of ministerial briefings for two of the plans referenced at PAEC, Delivering the Goods—Victorian Freight Plan and the Victorian Cycling Strategy 2018–2028. Neither briefing explains how the plans are part of the transport plan nor how they contribute to compliance with section 63 of the Act.

Transparency

There is a lack of transparency around what the transport plan is. Most of the documents DoT refers to as forming part of the plan required by the Act are not available to the community. Nor are they accessible to other agencies and stakeholders involved in, reliant on, or affected by the transport system.

Only 14 of the 29 completed plans DoT identifies as part of the transport plan are published. In addition, DoT's public webpage on transport plans and strategies only lists three documents and makes no reference to the Act’s requirement for a transport plan.

In April 2021, DoT updated its public website to include the six Victorian Transport Strategic Directions approved by government in late 2020. DoT has also recently added Victoria’s Bus Plan to its public website.

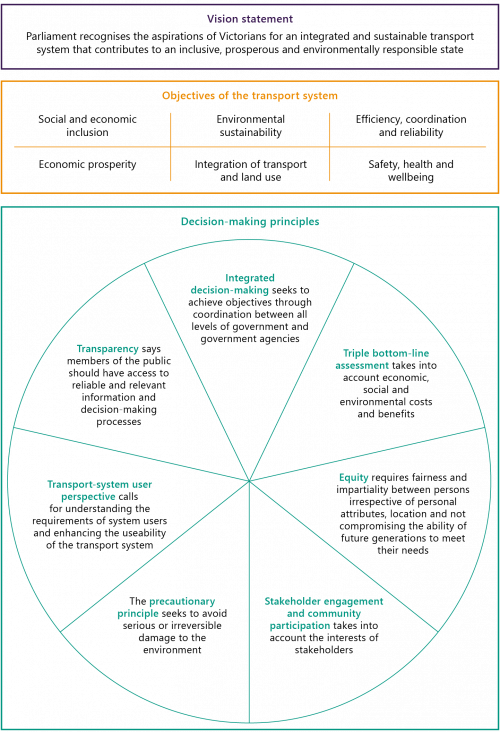

The Act's decision-making principles

The Act does not require the transport plan to be published and provides the minister with discretion over its publication. As such, DoT argues that its unpublished plans are part of an 'internal transport plan for DoT'. However, as shown in Figure B, the Act includes decision-making principles that emphasise transparency, integration, coordination and stakeholder engagement.

FIGURE B: The Act's decision-making principles

| Principle | Key text from the Act |

|---|---|

| Integrated decision making | The principle of integrated decision making means seeking to achieve Government policy objectives through coordination between all levels of government and government agencies and with the private sector. |

| Transparency | The principle of transparency means members of the public should have access to reliable and relevant information in appropriate forms to facilitate a good understanding of transport issues and the process by which decisions in relation to the transport system are made. |

| Transport system user perspective | The transport system user perspective means— (a) understanding the requirements of transport system users, including their information needs; (b) enhancing the useability of the transport system and the quality of experiences of the transport system. |

| Stakeholder engagement and community participation | The principle of stakeholder engagement and community participation means— (a) taking into account the interests of stakeholders, including transport system users and members of the local community; (b) adopting appropriate processes for stakeholder engagement. |

Source: VAGO, from the Act.

DoT's administration of the Act would be more consistent with these principles if it provided the public and other stakeholders with full disclosure about the information on the many documents it considers provide the comprehensive transport plan required by the Act, and an explanation of how these documents are linked and work together to satisfy the Act. Specifically, providing stakeholders such as planners in other departments, local and Commonwealth governments, and industry with more information on the transport plan documents would support the Act's principles on integrated decision making and transparency.

The principles about understanding the information needs of transport-system users and engaging with the community would also be advanced if the transport plan were made public in an easily understood format.

The Network Development Strategy

DoT's predecessor, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR), identified the absence of a single document to communicate a transport plan for Victoria as a gap. It began working on a single integrated transport plan, known as the Network Development Strategy (NDS), in early 2015.

DEDJTR changed the nature and purpose of the NDS in mid-2015. The strategy shifted from being a standalone transport plan to a planning approach focused on areas and outcomes rather than on specific transport modes, such as roads or rail. This approach involved identifying transport needs and priorities across metropolitan and regional areas by assessing current and predicted transport system performance against desired outcomes.

Transport for Victoria (TfV) began operating in 2017 and continued to develop the NDS approach. TfV progressed area-based planning to inform broader network and modal planning. This was intended to ensure an integrated whole-of-network view and good advice to government on investment priorities. Government endorsed the NDS approach in 2016 and 2017.

DoT informed us that in November 2017, DEDJTR and TfV determined that the transport planning results collated in a partially completed NDS compendium document essentially fulfilled the requirements of section 63 of the Act. However, the NDS compendium:

- does not include any explicit reference to section 63 of the Act

- does not fully meet the requirements of section 63 of the Act

- is incomplete, as specific plans for some transport modes had not been developed

- was not shared with other stakeholders intended to benefit from integrated planning under the Act, including government departments and local councils.

DoT is yet to fully complete all the NDS planning documents promised to government in 2017. Specifically, plans for some transport modes, plans for networks, ports, airports and theme-based plans and strategies that were to be finalised and incorporated into the NDS have not been completed.

In addition, we have seen no evidence of further specific advice to government on progress in applying the NDS approach—or changes to it—after November 2017. DoT has not reviewed the NDS approach despite its commitment to government to refresh the approach annually and undertake a major review every three years.

DoT’s progress developing integrated transport plans

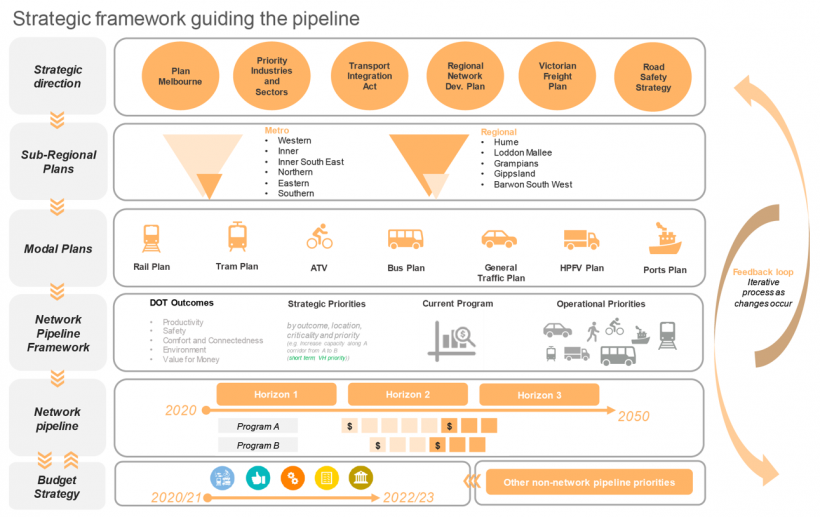

DoT is developing a new integrated transport planning framework and multiple plans and strategies that show progress towards better integrated transport planning. Positively, while the plans DoT has developed since 2019 are yet to fully meet the requirements of the Act, they demonstrate greater compliance than earlier plans. Figure C shows the key transport strategies, plans and frameworks DoT is working on.

FIGURE C: DoT's progress towards developing an integrated transport system

| Plan/strategy | Description | Progress | Commentary |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Transport strategy |

Intended to set the long-term vision for Victoria’s transport system. Includes six strategic directions to guide transport planning, endorsed by government in late 2020. |

Commenced in 2018 Progress stalled in 2019 due to staff and organisational changes. Work recommenced in 2020 but no completion date has been set. DoT published the six strategic directions to guide transport planning in April 2021. |

DoT has been developing this strategy for nearly three years and provided evidence on its intended purpose and content, but could not provide a draft for our review. |

|

Victoria’s Living Transport Network (VLTN) |

Consolidates and integrates all strategic and network plans. Clarifies how planning fits together. Establishes practice notes to guide ongoing network planning coordination. Identifies and prioritises transport network needs. |

Commended in early 2020. DoT completed the VLTN strategic framework, which shows how transport planning legislation, strategic directions, plans and investment and service programs fit together, in mid-2021. DoT completed three practice notes in mid-2021, to drive greater consistency and alignment across transport plans. |

The VLTN strategic framework is important because it provides a coherent overarching architecture or hierarchy within which individual streams of transport planning work can occur and be linked. The DoT Executive group endorsed the framework in mid July 2021. |

|

Metropolitan and regional or sub regional integrated transport plans |

Multi-modal plans that are intended to link statewide policy objectives with place specific network priorities. DoT is developing a plan for each of Victoria’s five regional and six metropolitan regions. |

Commenced in 2019. Seven of 11 plans have been completed but only two have been approved by DoT’s Network Planning and Engineering Committee (NPEC). Completion expected by June 2022 with annual updates. |

DoT identifies regional and sub regional integrated transport plans as critical to achieving integrated transport planning, but is yet to complete them. Plans completed to date do not include all of the content required by section 63 of the Act or clearly align with the transport strategy. |

|

Modal plans |

Individual plans for transport modes including rail, pedestrians, bus, general traffic, freight, ports and interchanges. These plans are intended to translate priorities identified in regional integrated transport planning into modal, network wide plans. |

Appendix E shows DoT’s progress in developing modal plans. |

Modal plans completed and in development only partly meet the requirements of section 63 of the Act. The plans do not refer to a consistent planning framework for transport and have been developed in the absence of overarching and area-based plans. DoT lacks target completion dates for some plans under development and advised us that it is not responsible for setting completion dates. |

Note: The description is VAGO's based on information provided by DoT.

Source: VAGO, from DoT information.

DoT's progress towards more integrated planning includes developing the VLTN framework during 2020 and 2021 to consolidate and coordinate all transport planning for Victoria. The framework sets out an approach and program of work to integrate transport planning. However, some of the plans DoT is developing, which should flow from the VLTN, lack explicit attention to meeting the requirements of section 63 of the Act. They also do not reference the new VLTN framework and approach.

In addition, DoT is yet to fully standardise its approach to area-based transport planning. This is leading to inconsistency in draft regional plans that may compromise the extent to which these plans can be integrated. DoT finalised detailed practice notes in mid-2021 to address this and support DoT staff to develop plans using consistent methodology, definitions and practice guidance.

Recommendations about the transport plan

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Transport | 1. clarify and publish a definitive listing and explanation of the documents and resources that contribute to the transport plan required by the Transport Integration Act 2010 and how these documents are linked and work together to satisfy the Act (see sections 2.2 and 2.3). | Partially accepted |

| 2. establish completion timelines for all outstanding priority transport plans and start tracking progress against them (see section 2.5). | Not accepted | |

| 3. ensure any advice to ministers on whether individual transport plans or strategies should be published addresses and conforms with the Transport Integration Act 2010's principles on transparency and integrated decision-making (see section 2.3). | Accepted | |

| 4. complete the Victoria’s Living Transport Network framework and underlying practice guidance to drive a consistent approach to integrated transport planning (see section 2.5). | Accepted |

Challenges and progress in delivering integrated transport planning

The Act aims to establish an integrated approach to planning across all transport modes and agencies. However, DoT and its predecessors have not delivered this. VAGO performance audits since 2012 identify a failure to address systemic issues with the integration of transport planning, operations and services.

Institutional barriers to integration

DoT and its predecessors have commissioned multiple reviews of organisational arrangements and transport planning since early 2015. These reviews identified complex institutional arrangements as the primary barrier to achieving integrated transport planning.

The reviews found institutional arrangements perpetuated a focus on individual transport modes, rather than an integrated approach. Though agencies with a specific focus on transport modes, such as VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria (PTV), have legitimate roles in transport planning, they have little incentive to take a system-wide view.

DoT and its predecessor departments acted on this external advice by recommending to government incremental institutional changes, such as the creation of TfV in 2017. Such changes are yet to deliver fully integrated transport planning. This indicates institutional change needs to be accompanied by strong leadership and governance that supports and drives cultural and behavioural changes to deliver a coordinated and integrated approach across transport modes without losing essential mode specific expertise.

DoT has the opportunity to—and is making progress to—finally deliver integrated transport planning. Its creation in early 2019 and the transfer of PTV and VicRoads into DoT in mid-2019 has largely removed transport sector agencies focused on specific transport modes.

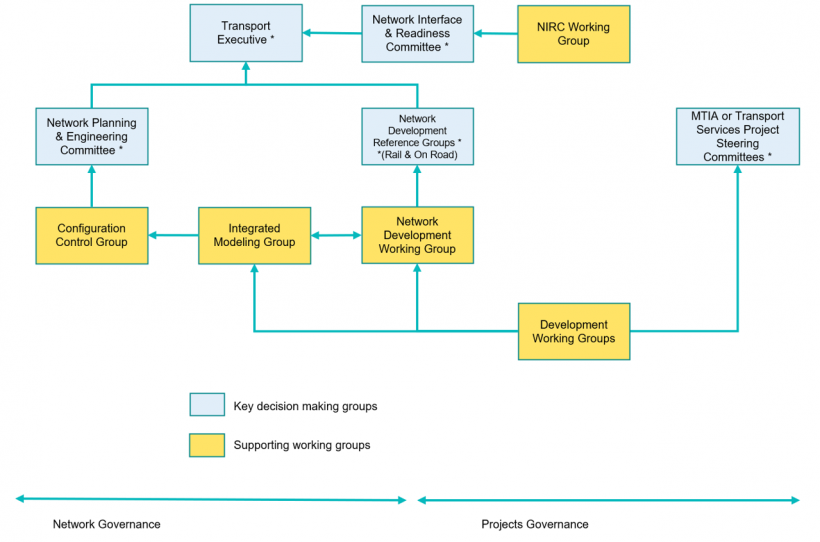

Governance and accountability

Reviews commissioned by DoT and its predecessors since early 2015 have consistently found that governance and accountability problems in the transport portfolio contributed to a lack of integration. These problems included a lack of role clarity due to overlap and duplication of roles, responsibilities, accountabilities and reporting lines.

An early 2018 review on the organisational and operational issues impeding the realisation of TfV's vision found that despite the intentions communicated at TfV's creation, senior leaders across the sector rarely met. It also found governance models were ineffective due to a lack of clear decision rights.

Institutional changes since early 2019, creating the new DoT and absorbing PTV and VicRoads into DoT, presented an opportunity to address governance related barriers to integrated transport planning.

Over the last two years, DoT has established and refined clear governance and accountability arrangements that should support the coordination and delivery of integrated transport planning activities across the portfolio.

Critically, DoT's new governance arrangements address issues raised by previous external reviews about the lack of role clarity and decision-making authority. For example, the NPEC, created in May 2020, has clear responsibility for strategic leadership of integrated transport planning across the state and decision-making authority for area-based and modal plans.

DoT demonstrated a significant commitment to training programs during 2020 to address acknowledged transport planning and other capability gaps. Importantly, the scope of this training extends beyond technical skills to cover leadership and management skills. It also emphasises capabilities and strategies intended to underpin and support engagement. DoT expects this training to foster a collaborative approach across the department.

Informing government investment priorities

There is little evidence that DoT used an integrated, whole-of-transport system planning approach when proposing investment priorities to government for the 2020–21 budget process. Instead, individual modal transport plans and other criteria informed advice to government on investment priorities.

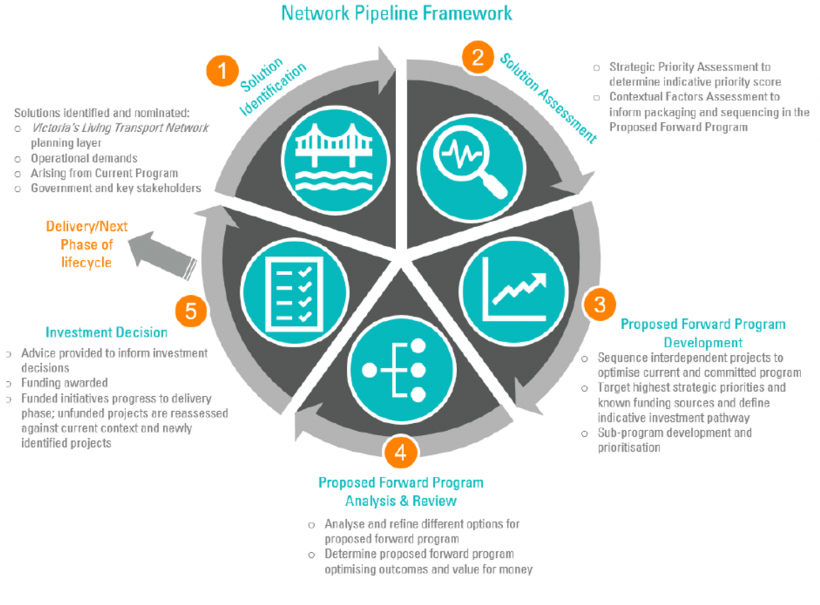

DoT completed its new transport network investment pipeline framework in mid 2021 to provide a clear basis for the investment priorities it proposes to government.

Recommendations about delivering integrated transport planning

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Transport | 5. periodically review governance arrangements for transport planning to assess whether they remain fit for purpose in supporting integrated transport planning (see section 3.2). | Accepted |

| 6. continue to emphasise, embed and monitor leadership and cultural change as it moves towards more integrated transport planning (see sections 3.1 and 3.2). | Accepted | |

| 7. ensure its approach to formulating advice to government on transport investment priorities demonstrates the results of integrated planning for the transport system (see section 3.3). | Accepted |

1. Audit Context

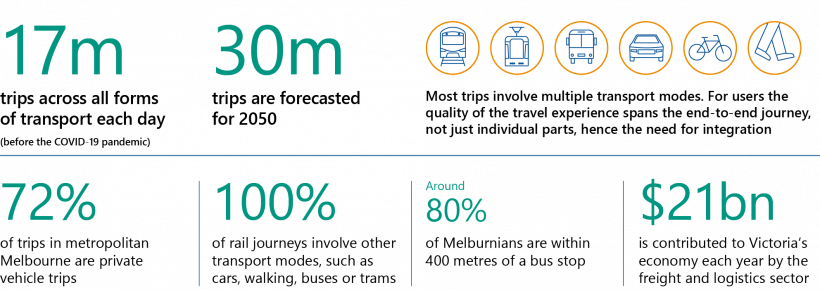

Transport systems link people to family, work, education and recreation, and are critical enablers of economic activity. DoT estimates that the current 17 million trips across all forms of transport in Victoria each day will grow to more than 30 million by 2050.

The state's transport system is made up of multiple modes and networks, spanning roads used by private, commercial and freight vehicles, public transport delivered by trains, trams, and buses, and active transport, such as cycling and walking.

Many people use more than one mode on their journeys. This requires integrated transport planning and services that are coordinated across modes to best meet user needs. The Act supports this by requiring a transport plan that demonstrates an integrated approach.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 Victoria's transport system and legislation

Victoria’s transport system is complex and comprises multiple modes and networks. The Act defines the following transport system components as all contributing to moving people and goods around Victoria:

- physical components, such as roads, railways, cycling paths, trains, trams, private and commercial vehicles, stations, stops and signals

- management components, such as strategic and operational planning, timetabling and ticketing, licensing and regulation

- labour components, such as the people involved in planning, regulating and operating the physical and management components of the transport system

- services components, such as the passenger, freight and other transport services that move people and goods around the state.

Planning and operating this system to best meet user needs requires DoT to coordinate with other state and local governments, multiple franchisees and transport operators, business and the community.

The Act provided the first universal framework (shown in Figure 1A) to guide planning, decisions and actions impacting the transport system. It sets out the vision, transport-system objectives, and decision-making principles for use by state and local government agencies. It requires all decisions affecting the transport system to be made within its integrated decision-making framework and in support of transport system objectives.

FIGURE 1A: Framework established by the Act

Source: VAGO, based on information from the Act.

1.2 Transport planning requirements and guidance

When the Act was introduced in Parliament in 2010, the second reading speech described it as a 'watershed in the evolution of transport policy and legislation in Victoria and Australia'.

The Act was intended to shift the planning and operation of the transport system away from a focus on individual modes in isolation, towards:

'a system in which each and every transport activity—public transport on road and rail, commercial road and rail transport, private motor vehicles, commercial and recreational water transport, walking and cycling—works together as an integrated whole'.

Requirements for the transport plan

The Act makes DoT the lead portfolio body in planning, coordinating, and managing an integrated transport system. It requires the DoT Secretary to prepare and periodically revise the transport plan for the relevant minister.

Section 63 of the Act sets out content that must be included in the transport plan and what DoT must consider when developing it. Figure 1B shows these requirements, which include the need for the plan to set the planning framework within which transport bodies are to operate, provide strategic policy context, and demonstrate an integrated approach to transport and land-use planning.

FIGURE 1B: Section 63 of the Act

| Subsection | Requirements |

|---|---|

| (1) | The Secretary must prepare and periodically revise the transport plan. |

| (1A) | The Secretary must provide a copy of the transport plan to the Minister. |

| (2) |

The transport plan must— (a) set the planning framework within which transport bodies are to operate; (b) set out the strategic policy context for transport; (c) include medium to long term strategic directions, priorities, and actions; (d) be prepared having regard to the vision statement, transport system objectives and decision making principles; (e) be prepared having regard to national transport and infrastructure priorities; (f) demonstrate an integrated approach to transport and land use planning; (g) identify the challenges that the transport plan seeks to address; (h) include a short term action plan that is regularly updated. |

| (4) | The Minister may publish the transport plan. |

Source: VAGO, from the Act.

Single or multiple transport plans

The explanatory memorandum provided to Parliament with the Bill to establish the Act in 2010 indicated that the transport plan should be treated as a single plan that is continually updated rather than as a series of plans. However, the Act does not explicitly require the transport plan to be set out in a single document.

DoT seeks to fulfil the requirements of section 63 through multiple plans taken together. DoT advised us it has not sought legal advice on its interpretation of the Act because that interpretation is consistent with the principle of statutory interpretation which states that references to the singular also include the plural.

Transport planning guidance

Transport planning can be undertaken at many levels, including across different geographic areas, transport modes, networks and timeframes. These transport system aspects or layers are not static as user needs and preferences, and technology, are constantly evolving.

There is national guidance on how best to approach transport planning. The Australian Transport Council's National Guidelines for Transport System Management in Australia (2006) were revised and reissued by the Transport and Infrastructure Council in August 2016 as Australian Transport Assessment and Planning (ATAP) guidelines. ATAP guidelines include a framework with processes, methods and tools to guide transport planning and decision-making.

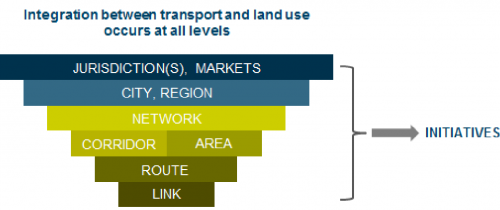

ATAP guidelines suggest transport planning and assessment should be integrated and multi-modal. They include a hierarchy of integrated transport-system planning levels, as Figure 1C shows.

FIGURE 1C: ATAP hierarchy of integrated-system planning levels

Source: Transport and Infrastructure Council, ATAP guidelines (2016).

The top two levels are focused on whole jurisdictions, markets or an entire city or region. At these levels, planning addresses land use, infrastructure and services. Such plans can produce broad strategies and complementary transport strategies at the jurisdiction, market, metropolitan or regional level.

Planning also occurs at the transport-network level. Traditionally, network planning focused on planning for individual modes, such as roads or rail, with work done within mode-specific agencies. DEDJTR obtained advice from external consultants in 2015 that this can lead to suboptimal outcomes for integrated planning across multiple networks and modes of transport if mode-specific agencies lack a 'joined-up' approach.

ATAP guidelines emphasise the need for multi-modal planning based on the philosophy that modal planning should be replaced—or preceded—by multi-modal planning. Multi-modal planning focuses on serving people and freight rather than focusing on individual transport modes.

Tactical or systems planning addresses matters such as the service delivery model for transport, including contract design and management, and system pricing, ticketing, and marketing.

More detailed planning then occurs at corridor, area, route and link levels. There is also a need for tactical or systems planning and detailed day-to-day operational planning.

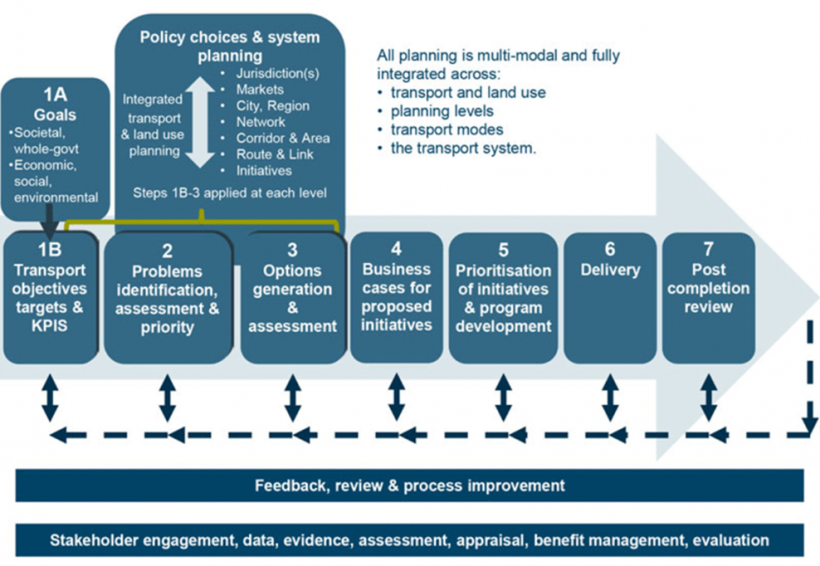

Figure 1D shows where ATAP guidelines position transport system planning in the overall transport planning, investment and delivery cycle.

FIGURE 1D: ATAP guidance on transport planning cycle

Source: Transport and Infrastructure Council, ATAP guidelines (2016).

1.3 Victoria's published transport plans

Victoria has a history of transport and land-use planning strategies that demonstrate varying degrees of integration.

In May 2006, the state government released Meeting Our Transport Challenges: Connecting Victorian Communities. This transport plan promised more than $6 billion to public transport over a 25‐year period.

In 2008, the state government commissioned the report Investing In Transport: East West Link Needs Assessment (also known as the Eddington report) to investigate transport solutions to connect Melbourne’s eastern and western suburbs.

The government released The Victorian Transport Plan in December 2008 as a 30‐year integrated transport plan that replaced Meeting Our Transport Challenges: Connecting Victorian Communities. It included responses to recommendations in the Eddington report.

When the Act was introduced in July 2010, The Victorian Transport Plan was recognised as fulfilling the requirements of section 63. An election in November 2010 led to a new government and The Victorian Transport Plan ceased to be government policy.

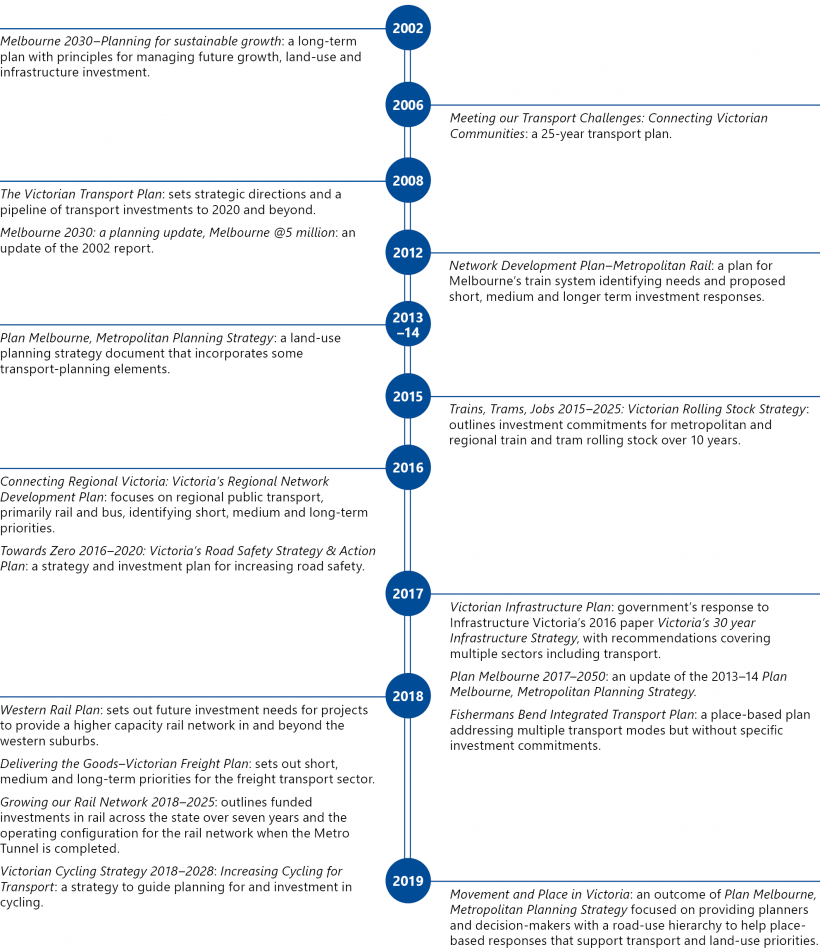

Figure 1E shows plans and strategies published since 2000 that relate directly or indirectly to the transport system.

FIGURE 1E: Timeline of Victorian transport plans and strategies published since 2000

Source: VAGO.

In Chapter 2 of this report, we assess the transport plans and strategies published since 2010. We also look at many other plans developed by DoT and its predecessors that were not published.

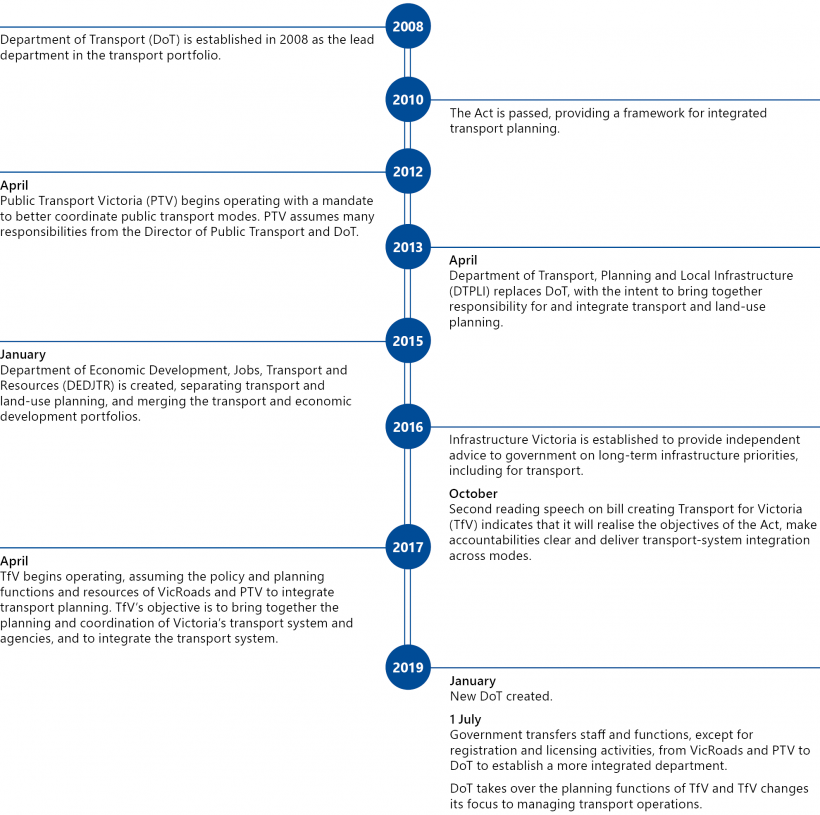

1.4 Changes in institutional arrangements since 2010

Since 2010, there have been ongoing changes to transport portfolio arrangements, moving the transport planning function between different organisations. It is now consolidated within DoT. Figure 1F shows the key changes.

FIGURE 1F: Timeline of key institutional changes impacting the transport portfolio since 2010

Source: VAGO, based on information from DoT.

1.5 Previous attempts at integration

The previous DoT (2008–13) began work on a multi-modal coordination policy and strategy for the public transport network after The Victorian Transport Plan stopped being government policy in late 2010. DoT intended the strategy to set out a coordination framework and service specification for public-transport planners. They were to use the strategy for integrated network-wide planning and scheduling across all modes of public transport.

However, VAGO’s April 2014 Coordinating Public Transport performance audit report found the multi-modal coordination policy and strategy was not complete despite being in draft since August 2011. We recommended that its scope be extended to regional services and it be finalised. PTV responded that it was developing separate network development plans for the metropolitan rail network and on-road public transport. This seemed to indicate that the multi-modal coordination policy and strategy would not be finalised.

The next significant attempt to deliver an integrated transport plan was in 2015, when DEDJTR began coordinating development of an integrated transport plan referred to as the NDS. DEDJTR informed Parliament and the community in its 2015–16 Annual Report that the government had endorsed its approach to transport planning through the NDS.

The NDS approach specified long-term directions and strategic principles that were to be used in area-specific transport planning across the state to inform modal plans. The NDS was not completed. We discuss the progress made using the NDS integrated planning approach in Chapter 2 of this report.

1.6 Past VAGO audits of transport planning

VAGO has completed a number of performance audit reports since 2010 that identify issues with planning and integration in the transport system. The issues include:

- the lack of a clear statewide plan for the transport system that meets the Act's requirements

- the lack of clarity, coordination and integration across the transport portfolio

- transport agencies acknowledging that they need to broaden their planning beyond individual modes to take a system-wide view.

Appendix D lists the relevant audits and summarises their findings.

2. Transport plans

Conclusion

The published plans and strategies DoT identifies as forming the transport plan do not meet the requirements of the Act as they do not provide a comprehensive, integrated transport plan.

DoT is developing new plans and strategies that show progress towards greater integration of transport planning. However, the evidence available indicates that they also do not fully meet the Act's requirements.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Do transport plans meet legislative requirements?

The Act requires the DoT Secretary to prepare and periodically revise the transport plan for Victoria and to provide it to the minister. The Act specifies mandatory content for the plan. It also sets out matters that must be considered and demonstrated as the plan is prepared.

The Act does not explicitly require the transport plan to be set out in a single document and DoT asserts that it meets its legislative obligations through multiple plans taken together. However, the documents DoT identifies as comprising the transport plan do not fully meet legislative requirements.

Assessing DoT's transport plans

In June 2019, DoT advised the PAEC inquiry into the 2019–20 Budget Estimates that it is continually undertaking and updating its strategic integrated transport planning to meet the requirements of section 63 of the Act. DoT informed PAEC that this work is published externally in a variety of documents.

The documents DoT highlighted to PAEC include the following 11 publications that set out transport strategies and plans across the state:

- Network Development Plan—Metropolitan Rail (2012 and updated in 2016)

- Trains, Trams, Jobs 2015–2025: Victorian Rolling Stock Strategy (2015)

- Connecting Regional Victoria: Victoria's Regional Network Development Plan (2016)

- Towards Zero 2016–2020: Victoria's Road Safety Strategy & Action Plan (2016)

- Victorian Infrastructure Plan (2017)

- Plan Melbourne 2017–2050 (2017)

- Fishermans Bend Integrated Transport Plan (2017)

- Western Rail Plan (2018)

- Delivering the Goods—Victorian Freight Plan (2018)

- Growing our Rail Network 2018–2025 (2018)

- Victorian Cycling Strategy 2018–2028 (2018).

DoT advised us that in addition to these published plans and strategies, it has developed and is drafting multiple location-specific and transport mode-specific plans that fulfil the requirements of the Act. Appendix E lists the more than 40 documents DoT advised us form part of the transport plan required by the Act. These documents comprise:

- two broad whole-of-government plans relevant for transport—Plan Melbourne 2017–2050 (2017) and the Victorian Infrastructure Plan (2017)

- 22 plans relating to specific transport modes, including train, tram, bus, road, cycling and walking

- 12 location-specific plans covering regional Victoria and metropolitan Melbourne sub-regions

- four types of precinct, corridor and area based plans

- four miscellaneous plans and strategies.

Fragmented plans

DoT cannot demonstrate how its large collection of transport plans and strategies meet the specific requirements of the Act, nor can it show how they provide a coherent and comprehensive transport plan.

This is partly because DoT developed the plans at different points in time over a nine year period, and in the absence of a consistent, overarching framework. This makes it difficult for anybody to aggregate the content of the collection of plans in a way that provides continuity about how they link with—or build on—other plans to provide a system-wide transport plan for Victoria.

Further, the collection is yet to include completed plans that address all areas of metropolitan Melbourne and cover all modes of transport. Finally, DoT developed most of its modal plans before, rather than after, area-based plans which runs counter to integrated planning principles and is inconsistent with national transport planning guidance.

Even where plans do contain some of the requirements set out in section 63, most focus on a specific mode or a place. They do not provide an integrated plan.

The plans are highly varied in focus and detail, ranging from high-level strategies with a scope extending beyond transport, to mode or location-specific plans with varying levels of detail, and policy communication documents that list initiatives already underway or committed to. Individually or collectively, these documents do not convey a coherent, comprehensive statewide plan for integrating transport.

DoT has moved to address these issues in the last 12 months by developing the VLTN framework to clarify how transport strategies and plans fit together across DoT and to guide its current and future transport planning.

Compliance with the Act

We assessed the 32 plan or strategy documents DoT made available to us for review, against the content and development requirements for the transport plan set out in the Act (see Figure 1B). We could not assess more than 10 other plans and strategies as DoT is yet to finalise them.

Individually, none meet all the requirements. Specifically:

- nothing in the plans and strategies identifies them as being part of a collection of documents that form the transport plan required under section 63 of the Act

- only five plans explain how their content responds to and addresses the vision statement, transport-system objectives and decision-making principles of the Act, but the content of these plans is not directly applicable to all other plans and strategies

- only two of the plans, the Victorian Infrastructure Plan and Delivering the Goods—Victorian Freight Plan, explain how they were prepared with regard to national transport and infrastructure priorities, and the content of these plans is not directly applicable to all other plans and strategies

- most plans and strategies do not articulate and demonstrate clear links with one another, although DoT has improved this in plans it has developed since 2019

- the Act requires the transport plan to have a short-term action plan that is regularly updated. If all documents DoT identifies are collectively the transport plan, then it follows that each should have a short-term action plan. Of the 32 plans we assessed, 15 do not include a short-term action plan. These include plans such as the Victorian Cycling Strategy (2018-2028), Western Rail Plan and Growing our Rail Network 2018-2025, that should include short-term actions and these are not specified in any other plans or strategies.

Providing the transport plan to the minister

The Act requires the DoT Secretary to provide the transport plan to the minister. We sought evidence of advice to the relevant ministers for each of the documents DoT identifies as part of the transport plan. We expected this advice to explain how individual documents form part of the transport plan required under the Act.

DoT was able to demonstrate that it provided a ministerial briefing for only two of the plans it references as part of its integrated transport planning documents—Delivering the Goods—Victorian Freight Plan and the Victorian Cycling Strategy 2018–2028. Neither briefing explains how the plans are part of the transport plan or contribute to compliance with section 63 of the Act.

We also saw documentation on advice to government about eight of the other plans DoT identifies as part of the transport plan. None of this advice included specific reference to individual documents forming part of the transport plan required under section 63 of the Act.

2.2 Absence of a single document

The Act's substantive requirement for a transport plan can be met with multiple documents if certain conditions are met. Figure 2A shows that DoT is not meeting any of these conditions for multiple documents to meet the legislative requirements for the integrated transport plan.

FIGURE 2A: Multiple documents do not meet the legislative requirements

| Multiple documents would satisfy the Act if | Is DoT meeting the condition? | Reason |

|---|---|---|

| A transparent and definitive account of all plans, strategies and other resources that contribute to the transport plan exist | No | DoT does not have a formal, definitive catalogue of documents that make up the transport plan, showing a lack of transparency |

| DoT demonstrates how the collection of documents comprising its transport plan relate to each other, are linked and work together to provide a comprehensive transport plan that covers all system components | No | The individual plans do not satisfy this test and DoT has not released an overarching document |

| DoT explains how updated and new plans and strategies fit with, and build on, the existing transport plan documents | No | DoT is yet to publish a new or updated plan that explains how it builds on previous plans and strategies |

Source: VAGO.

The absence of a single document to communicate a transport plan for Victoria has been identified as a gap by DoT and its predecessors.

Advice from external consultants to DEDJTR during 2015 clearly and repeatedly identified the requirement in the Act for a transport plan. It said that 'there is currently no integrated transport plan in place for the state'.

Further external advice to DoT in March 2019 noted that DoT staff had identified the absence of an overarching integrated transport plan. Staff noted that this needed to be addressed to help agencies identify the strategy, objectives and priorities for the state. They also noted that an integrated transport plan would show agency roles in, and responsibility to deliver against, the plan. The advice noted that the:

'ad hoc nature of project development and implementation, without an integrated transport plan to drive investment decisions, undermines a whole-of-lifecycle perspective to network planning.'

DoT developed a current state report in mid–2019 to capture and map roles and functions across DoT, VicRoads and PTV. It was intended to inform the reorganisation of these agencies into DoT. The report states that:

'Consultations have highlighted the paramount need for the department to develop an agreed Network Development Strategy to establish long-term priorities and a strategic framework for an integrated and coordinated approach to planning, design, delivery and operation of the transport network and to meet legislative requirements.'

This highlights views within DoT that an overarching transport plan and strategy is necessary.

2.3 Transparency about the transport plan

The Act provides the minister with discretion to publish the transport plan.

DoT is not transparent to external stakeholders about what constitutes Victoria’s transport plan because:

- it has not made available to the public a definitive account of all the documents that contribute to the plan

- only 14 of the 32 plans available for review that DoT identifies as part of the transport plan have been published (refer to Appendix E for details)

- it did not refer to any completed but unpublished plans when advising PAEC about what constitutes the transport plan.

This means most of the documents DoT refers to as forming part of the plan required by the Act are not available to the community or other agencies. They also cannot be seen by other stakeholders involved in, reliant on, or affected by the transport system. In addition, DoT's webpage on transport plans and strategies makes no reference to the Act’s requirements for a transport plan. It also lists only three documents.

In April 2021, DoT updated its public website to include the six Victorian Transport Strategic Directions approved by government in late 2020. DoT has also recently added the new Victoria’s Bus Plan to its public website.

DoT completed a number of modal and area-specific transport plans between 2019 and mid-2021, including regional integrated transport plans and the tram, rail and bus plans. DoT has only made Victoria’s Bus Plan available to Parliament and the public.

DoT argues that the Act does not stipulate a need or requirement for publicly accessible transport plans. It says the unpublished plans are part of an internal transport plan for DoT. However, transparency about Victoria's transport plan is important because the Act envisages the benefits of integrated transport planning extending beyond DoT to other stakeholders.

The Act includes the following decision-making principles that emphasise integration, transparency, coordination and stakeholder engagement:

|

Under the Act's decision-making principle of … |

Which covers … |

Publishing transport plans is consistent with the principle as … |

|

Integrated decision making |

Coordination between all levels of government and government agencies and with the private sector to achieve policy objectives |

Other levels of government, departments and agencies, and the private sector would be more informed and better positioned to coordinate their planning and decision-making related to or affected by transport issues. |

|

Transparency |

Access to information by the public so it can understand transport issues and how decisions about the transport system are made |

It would provide the public with greater access to information on transport issues and decisions about planned investments and service enhancements. |

|

Transport-system user perspective |

Understanding transport system user needs to make the system more useable and create quality travel experiences |

It is reasonable to suggest that the information needs of transport system users include a need to understand what Victoria’s transport plan is. |

|

Stakeholder engagement and community participation |

Taking the interests of stakeholders such as transport-system users and local community members into account and undertaking stakeholder engagement |

The community and other stakeholders would be better engaged with—and positioned to provide input on—transport system issues if they had greater access to all documents forming part of the transport plan. |

DoT's administration of the Act would be more consistent with these principles if it provided the public and other stakeholders with transparent and easy access to:

- information on the many documents it considers provide the comprehensive transport plan required by the Act, and an explanation of how these documents are linked and work together to satisfy the Act

- the published plans and strategies. Currently, DoT's webpage on transport plans and strategies lists only three documents.

Providing stakeholders with access to the transport plan documents would support the Act's principles on integrated decision-making and transparency. These stakeholders include land-use and other planners in other departments, and local and federal governments, as well as industry.

2.4 The Network Development Strategy

In early 2015, DEDJTR started to develop a single integrated transport plan, called the NDS. Evidence clearly shows that, at the time, ministers had indicated to DEDJTR that the integrated transport plan required by the Act should be developed and be known as the NDS.

Purpose of the NDS

DoT advised us that the NDS was initially intended to be a traditional transport strategy. However, DEDJTR decided in mid-2015 to change its function from a single transport plan to a new strategic methodology to guide integrated transport planning. DEDJTR informed Parliament and the community in its 2015–16 Annual Report that the government had endorsed its approach to transport planning through the NDS.

The NDS approach involved:

- a primary focus on regions and transport-system outcomes to avoid a narrow focus on only planning for specific transport modes

- identifying transport needs and priorities across five metropolitan and five regional areas by assessing current and predicted transport-system performance through the lens of desired outcomes

- using area and corridor spatial planning to inform network and modal planning to ensure an integrated, whole-of-network view.

DEDJTR intended the NDS to identify priority initiatives over the short, medium and long term to inform advice to government on investment priorities.

There is evidence that DEDJTR and TfV intended the NDS to be the way to achieve integrated transport planning, as required under the Act. Advice to government in early 2016 seeking endorsement of the NDS approach noted that:

'As the Transport Integration Act 2010 commenced in 2010, there may be criticism that it has taken five years to develop integrated transport planning as prescribed in the Act.'

Progress in developing the NDS

Government endorsed the NDS planning approach and a program of engagement with industry and stakeholders to gain buy-in and input in March 2016.

TfV took over development of the NDS from DEDJTR during 2017 and provided further advice on progress to government in November 2017. This advice included a snapshot of baseline findings on transport challenges for each of the 10 regions in the state. It also indicated investment options and pathways or sequences for tackling strategic issues facing the transport system.

TfV’s advice to government in November 2017 highlighted that the NDS was to be:

- iterative, and updated to include public-facing mode-focused strategies

- refreshed on an annual basis and subject to a major review every three years

- used to provide advice to government on the preparation of budgets, and on responses to Infrastructure Victoria’s reports and market-led proposals for transport investment.

Government considered and endorsed the report on NDS progress in November 2017. It noted that work was continuing on a number of modal, network and thematic strategies arising from the NDS planning, including public-facing strategies. It also said that these would be progressively incorporated into an overall planning document. These government decisions endorsed the ongoing use of the NDS approach, and its name as a central integrated transport planning document.

DoT provided us with an NDS transport planning compendium document dated October 2017. It is a more detailed version of the document presented to government in November 2017.

In addition to baseline data for Victoria’s 10 regions, the compendium includes sections on various transport modes. However, these sections were not all complete or prepared to the same level of detail. The document had placeholders for yet-to-be-completed plans for specific transport modes, networks, ports and airports. It also had placeholders for theme-based plans and strategies that were to be finalised and incorporated into the NDS.

DoT informed us that, in November 2017, DEDJTR and TfV determined that the integrated transport planning work in the NDS compendium essentially fulfilled the requirements of section 63 of the Act and that this planning would be used to inform externally published plans and strategies.

However, the NDS compendium:

- does not make explicit reference to section 63 of the Act

- does not fully meet the requirements of section 63 of the Act because it does not include any specific commentary on how it was prepared with regard to the Act’s vision statement, transport-system objectives and decision-making principles

- is incomplete as plans for some transport modes had not been developed

- was not shared with other stakeholders intended to benefit from integrated planning under the Act, including other departments and local councils.

We have seen no evidence of any further specific advice to government on progress in applying, or proposing changes to, the NDS approach after November 2017.

Completion of the NDS

An external consultancy report to TfV in February 2018 identified the NDS as being of material benefit because it was a new way of developing the transport system. It involved a structured, integrated approach to designing, planning, building and operating the system.

The report noted the NDS's effective rollout was expected to help break down modal silos and ensure the right transport solutions were delivered.

However, despite considerable transport planning activity during 2016 and 2017 to progress the NDS analysis and approach, DoT has not completed key deliverables, nor has it fully implemented the approach.

DoT is yet to produce a finalised suite of NDS planning documents comprising all the elements promised to government in 2017. Specifically:

- DoT is yet to complete the integrated transport plans for all metropolitan Melbourne sub-regions or the airport strategy

- there is limited evidence of the annual refresh of plans for regional areas that DoT promised under the NDS methodology

- there has not been any major review of the NDS approach despite DEDJTR’s commitment to government that it would refresh it annually and do a major review every three years.

DoT has incorporated the NDS approach and analysis into its integrated transport planning since DoT's creation in 2019.

2.5 DoT's current transport planning work

DoT is developing a new integrated transport planning framework and multiple plans and strategies that show progress towards better integrated transport planning. Positively, DoT now has a clear framework showing how the various plans fit together. While the plans developed since 2019 are yet to fully meet the Act's requirements, they generally demonstrate greater compliance than earlier plans.

Figure 2B shows DoT’s progress on key transport strategies, plans and frameworks.

FIGURE 2B: Transport strategies, plans and framework under development

| Plan or strategy | Description | Timelines and progress |

|---|---|---|

|

Transport strategy |

This strategy is intended to set the vision for Victoria’s transport system for 2021 to 2051. It includes six strategic directions to guide integrated transport planning. The government endorsed these strategic directions in late 2020. |

Commenced in 2018 Progress stalled in 2019 due to staff and organisational changes. Work recommenced in 2020 but no completion date has been set. DoT published the six strategic directions to guide transport planning in April 2021. |

|

VLTN |

This framework is intended to:

|

Commenced in early 2020 DoT completed the VLTN framework, which shows how transport planning legislation, strategic directions, plans and investment and service programs fit together, in mid 2021. The DoT Executive group endorsed the framework in mid-July 2021. DoT completed three practice notes in mid-2021 to drive greater consistency and alignment across transport plans. |

|

Metropolitan and regional or sub-regional integrated transport plans (ITPs) |

These plans have a multi-modal focus and are intended to link statewide policy objectives with place-specific network priorities. DoT is developing a plan for each of Victoria’s five regional and six metropolitan regions, as defined in Plan Melbourne, Metropolitan Planning Strategy. |

Commenced in 2019 Seven of 11 plans have been completed but only two have been approved by DoT’s NPEC Completion expected by June 2022 with annual updates. |

|

Modal plans |

Individual plans for transport modes including rail, pedestrians, bus, light vehicles (general traffic), freight, ports and interchanges. These plans are intended to translate priorities identified in regional integrated transport planning into modal, network-wide plans. |

Appendix E shows DoT’s progress in developing modal plans. DoT lacks target completion dates for some plans under development and advised that it is not responsible for setting completion dates. |

Source: VAGO, based on information from DoT.

Compliance with the Act

The transport strategy has been in development for nearly three years, but DoT could not provide a draft for our review. This means we could not assess the strategy against the Act's requirements.

The plans DoT has developed since 2019 generally demonstrate greater compliance with the requirements of the Act than earlier plans.

However, while DoT is demonstrating progress towards more integrated planning, it still lacks explicit attention to meeting the requirements of section 63 of the Act. Some plans are yet to reference the new strategic directions, framework and approach.

DoT has identified metropolitan and regional ITPs as critical to achieving integrated transport planning. While the regional ITPs completed to date generally explain how they link with or are informed by other relevant plans, they:

- do not include all of the content required by section 63 of the Act and many lack specific references to the Act

- do not clearly refer to or align with the strategic directions approved for the transport strategy

- do not consistently reference the VLTN strategic framework, with four of the five plans for regional Victoria referencing the superseded NDS

- are not fully consistent in form and content, making it harder to bring together the information in these plans and see how they realise the intention of the VLTN and demonstrate an integrated and consistent transport planning approach

- have not been approved by the DoT Executive group or published.

Four plans covering areas of Melbourne are still to be completed. The ITPs recently completed for the Southern and Western regions of metropolitan Melbourne:

- include specific references to the Act and most of the content required by section 63 of the Act

- clearly refer to and align with the strategic directions approved for the transport strategy

- reference the VLTN strategic framework

- are consistent in form and content

- have been approved by NPEC but not DoT’s Executive group, and are not published.

Modal plans completed and under development by DoT:

- only partly meet the requirements of section 63 of the Act

- generally lack specific references to the Act's transport system objectives and decision-making principles

- with one exception (the bus plan), do not refer to a consistent planning framework for transport bodies

- do not refer to the transport strategy strategic directions, the VLTN or the sub regional integrated transport plans as critical inputs to their development

- are not transparent because two of the three recently completed and approved plans have not been made public.

Some of the issues identified with these plans reflect timing differences as the plans were developed before the transport strategy strategic directions and the VLTN framework were endorsed. DoT advised that shifting priorities, including the need to develop metropolitan sub-regional plans, has contributed to the protracted development and unclear completion dates for some modal plans.

DoT also said it would update references to relevant strategic directions and the VLTN. This is expected to help DoT achieve better consistency and alignment between ITPs and modal plans as it completes and refreshes the plans.

As it completes this work, DoT also needs to ensure that the next phase of development of regional and modal plans also meets the requirements for the transport plan in section 63 of the Act.

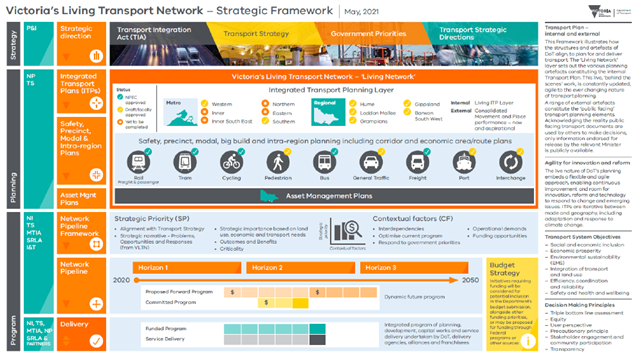

The VLTN framework

DoT's progress towards more integrated planning included developing the VLTN framework during 2020 and 2021. It aims to consolidate and coordinate all transport planning for Victoria. The VLTN framework, which Figure 2C shows, sets out an approach and program of work that has the potential to deliver significant benefits in driving more integrated transport planning across regions and modes.

FIGURE 2C: DoT's Victoria's Living Transport Network strategic framework

Note: DoT's NPEC recently approved the ITPs for the Southern and Western regions of metropolitan Melbourne.

Source: DoT.

The VLTN framework is important because it provides a coherent overarching architecture or hierarchy within which individual streams of transport planning work can occur and be linked. The term 'living' reflects the intention for this work to be updated and amended as an evolving resource rather than a static, point in time document, and should drive consistency.

The VLTN planning hierarchy is broadly consistent with ATAP guidelines and the approach developed under the NDS. Similar to the NDS, planning under the VLTN will include ITPs for each of the 11 regions across the state. These ITPs will inform modal plans.

The DoT Executive group noted but did not explicitly endorse progress and proposed next steps on the VLTN in late November 2020.

In June 2021, NPEC:

- endorsed an updated VLTN strategic framework, which Figure 2C shows, for submission to DoT’s Executive group for approval in July 2021

- approved the VLTN practice note providing a template for and guidance on preparing ITPs subject to the inclusion of a preface explaining the purpose of ITPs and how they interact with modal plans

- approved the VLTN practice note on the Living Transport Network language to provide the authors of DoT’s Living Network plans and other artefacts with common terminology, language and structure to ensure consistency across planning products

- approved the VLTN practice note developed to provide direction to transport planning teams on how to approach integrated transport planning in rural transport corridors

- approved the next steps in the VLTN program of work, including further development of practice notes and governance review processes.

The DoT Executive group endorsed the updated VLTN strategic framework in mid-July 2021. DoT advised us that it verbally briefed the minister on the VLTN, with further briefings to follow the second DoT executive briefing in July 2021.

DoT is supporting VLTN implementation by establishing a virtual knowledge resource called the Network Planning Hub. This hub will collate all planning resources in a single location and allow for plans to be represented geographically or thematically. DoT is making progress on the technical system solution for the Network Planning Hub and expects to finalise it during 2021. DoT advised us that it has recently started to upload plans onto its Network Planning Hub as they are completed and approved for internal publication.

The VLTN framework

Planning efforts across DoT have proceeded in the absence of a fully rolled out VLTN approach. This means DoT faces challenges in making sure its planning work—and the outputs of this work—are developed and presented using a consistent approach. DoT is addressing several challenges as it seeks to roll out and fully embed the VLTN approach.

|

A challenge for DoT is … |

So far DoT … |

This means … |

|

Timely completion and approval of plans and strategies |

Has drafted five ITPs covering regional Victoria during 2019 and 2020. Has completed two of six ITPs for metropolitan Melbourne. |

None of the completed regional ITPs have been approved by the DoT executive. DoT expects to complete all ITPs for metropolitan Melbourne by June 2022, over two years after it commenced the first ITP. |

|

Properly sequencing planning work |

Has indicated that it will complete modal plans before the regional and sub-regional ITPs for metropolitan Melbourne are completed and approved. |

That where overarching area-based plans are not completed, modal and network plans may not address the challenges and needs of specific geographical areas. |

|

Not using a consistent methodology and guidance for planning |

Is still finalising practice notes and guidance for ITPs and modal plans. The practice notes and guidance will not be completed before many of the plans are finalised. |

Despite the recent completion and approval of three important practice notes, DoT did not develop existing ITPs for regional areas and modal plans under the same methodology. Inconsistency in the completed draft regional plans could compromise the extent to which these plans achieve integration. |

DoT is aware of and is demonstrating progress in responding to these challenges. It has made significant progress since November 2020 in developing formal practice notes to guide consistent transport planning work across DoT and is completing area based plans.

3. Integration challenges and progress

Conclusion

Since 2015, multiple external reviews have identified that the primary barrier to integrated transport planning is institutional arrangements that perpetuate a focus on specific transport modes. Past, incremental institutional changes failed to address this issue. DoT now has the opportunity to deliver integrated transport planning because it has consolidated key transport sector entities into one department.

It is too early to say whether DoT will deliver the integrated approach to transport planning required by the Act. However, it has established clear governance and accountability arrangements that should support coordination of integrated transport planning.

This chapter discusses:

3.1 Barriers and challenges identified in external reviews

The Act aimed to establish an integrated approach to planning across all transport modes and agencies. Yet, neither DoT nor its predecessors have delivered integrated transport planning. VAGO performance audits and multiple reviews commissioned by DoT have identified systemic issues with the integration of transport planning and operations. However, neither the audits nor the reviews have prompted effective actions to address these matters.

Relevant past VAGO audits

Appendix D lists all relevant VAGO performance audit reports since 2010 that identify issues with planning and integration in the transport system. Taken together our reports highlight:

- the absence of a clearly articulated plan for the transport system as a whole that meets the Act's requirements

- a lack of clarity, coordination and integration across the transport portfolio despite regular changes to institutional arrangements intended to deliver just that

- a clear acknowledgement by transport departments and agencies that they need to plan beyond individual modes to take a system-wide view

- that departments and agencies have made commitments and started acting to address these issues, but their actions have been delayed, overtaken by events or not completed

- that lack of planning coordination and information gaps make it difficult to budget and understand where to invest

- gaps in minimum service standards and network technical standards to inform system planning and service and project delivery

- staff capability and capacity gaps and an erosion of corporate memory across the portfolio.

When these issues are considered in the context of an unprecedented and increasing level of investment in transport infrastructure since 2015–16, there are risks that the state may have missed opportunities to optimise the benefits of these investments and best meet the community's transport needs. This is not to suggest that investments in individual projects have lacked merit. Rather, there may have been missed opportunities to better sequence, coordinate and integrate these investments.

DoT and its predecessor agencies largely accepted the findings and recommendations arising from VAGO's previous audits.

During this audit, we have seen evidence that DoT acknowledges and is seeking to address these issues. DoT is, for example, developing the VLTN as a framework and program of work to consolidate, coordinate and integrate transport planning for all areas and modes.

DoT is also demonstrating a significant commitment to training staff to address capability gaps. This extends beyond technical training to cover leadership and management skills, and capabilities and strategies to underpin and support a collaborative approach across the department.

It is too early to assess the extent to which its actions are effective.

External reviews

Over the past six years, DoT and its predecessors commissioned the following external reports that highlight the need for—and barriers to—integrated transport planning:

- March 2015 report to DEDJTR on design options for integrated transport planning

- July 2015 report to DEDJTR on organisational structures for Victorian transport agencies

- February 2018 report to TfV on organisational and operational issues impeding the realisation of the vision for TfV

- January 2019 advice to DoT on a reform strategy for it to deliver more integrated transport planning and operations

- March 2019 report on an operating model for a more integrated DoT.

Figure 3A summarises the common issues identified in these reviews.

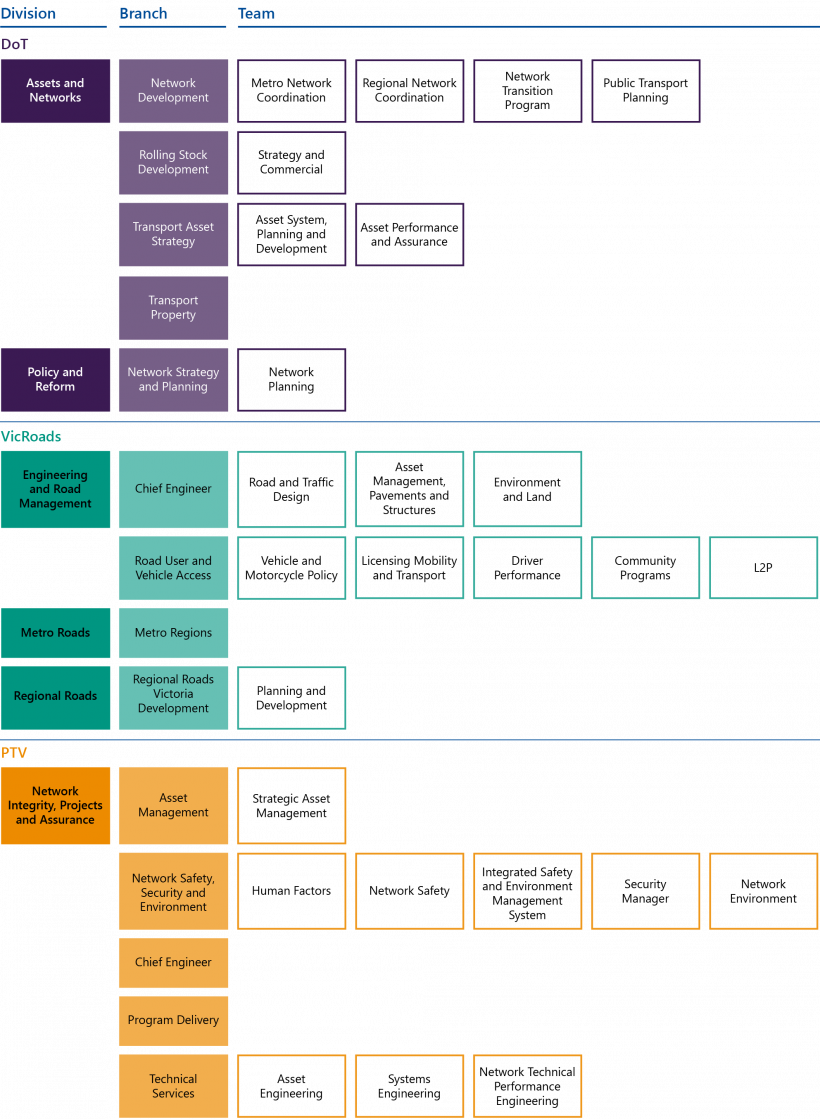

FIGURE 3A: DoT, VicRoads and PTV organisational units involved in planning in June 2019

| External reviews commissioned by DoT and its predecessors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Issue | Mar 2015 | July 2015 | Jan 2018 | Jan 2019 | Mar 2019 |

| The transport plan | |||||

| The Act requires an integrated transport plan | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Victoria does not have an integrated transport plan | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Institutional complexity and dysfunction | |||||

| The transport department is not leading an integrated system | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Governance and accountability issues due to lack of clarity, overlap and/or duplication around roles, responsibilities, accountabilities, and reporting lines | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Portfolio structure perpetuates a narrow focus on individual transport modes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lack of collaboration and coordination | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Fragmented rather than integrated planning | |||||

| Lack of collaboration and coordination across modes | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Lack of integrated transport strategies at network, corridor and local-area levels | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Fragmented planning effort across the portfolio | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| People issues | |||||

| Need for stronger leadership | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Need for cultural and behavioural change to support an integrated approach | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Staff capability gaps, including in transport planning | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Technology and systems issues | |||||

| Aging technology and systems | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Overlap or duplication in systems | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Data access and sharing | ✓ | ✓ | |||

Source: VAGO, from reports from external consultants to DEDJTR, TfV and DoT since early 2015.

The external advice summarised in Figure 3A consistently identifies that underlying institutional arrangements have perpetuated a focus on individual transport modes, preventing an integrated approach to planning and managing the system. The advice suggests that institutional changes:

- do not necessarily produce the collaborative behaviours and practices required for a truly integrated plan and approach across organisations and groups responsible for planning and managing individual transport modes

- need to be supported with leadership, cultural change and behaviours that actively deliver an integrated approach without losing essential mode-specific expertise.

Acting on external reviews to address institutional barriers

DoT and its predecessors used the external reviews summarised in Figure 3A as the basis for advice to government that institutional changes will deliver the integrated transport planning required by the Act. The government has accepted and approved a series of recommended institutional changes since 2015. However, these changes are yet to deliver the integration promised. TfV is the most recent example of such failure.

Transport for Victoria's efforts

The government approved the creation of TfV in mid-2016 based on advice from DEDJTR. It announced that:

'Like Transport for London and major cities around the world, TfV will bring together the planning, coordination and operation of Victoria’s transport system and its agencies, including VicRoads and Public Transport Victoria. This is the next evolution of the world-class transport system we are building for Victoria — a single, central, strategic body that coordinates our transport network and plans for its future. We need to stop thinking in terms of a road network and a train network and a tram network — we have a transport network, and we need a single transport agency to oversee it.'

TfV began operating in April 2017 with a clear mandate and powers to integrate transport system design, planning and service outcomes. It absorbed policy and planning functions and resources from PTV and VicRoads to deliver this.

TfV committed to centrally perform transport planning so transport agencies could focus on their operational roles. Nearly 200 (about 43 per cent) of its full-time equivalent staff were given the task of undertaking strategic transport policy, analysis, network planning and reforms. TfV aimed to develop an integrated transport plan in line with the NDS.

The February 2018 external report on the organisational and operational issues impeding TfV's vision found that it struggled to deliver on these commitments. The reasons for this included:

- a lack of leadership alignment around a common purpose and behaviours

- a complex institutional model with multiple interfaces and unclear boundaries across the department and agencies driving additional costs and slowing effective decision-making

- poor governance and accountability

- fragmented planning efforts with significant planning resources sitting outside TfV in mode-specific transport agencies, including PTV and VicRoads

- inconsistent ways of working and collaboration between agencies

- fragmented and disjointed user focus due to systemic, cultural and physical barriers that impeded effective collaboration

- ineffective enablers, including an inflexible sector workforce, disjointed and not fit-for-purpose technology, and limited access to, and analysis of, data.

DoT advised us that DEDJTR and TfV did not implement the recommendations in this report at the time due to:

- ongoing organisational changes

- the state election in November 2018

- further institutional changes that occurred after that election, including the creation of the new DoT in 2019.

Failure to address the recommendations immediately was a wasted opportunity. TfV and DEDJTR knew the timing of the state election when they commissioned the review, and the caretaker period began seven months after they received the report. In addition, many of the issues raised and recommendations made did not require decisions from government or ministers to address.

A more integrated DoT