Managing the Transition to Renewable Energy

Audit snapshot

Is Victoria on track to achieve its renewable energy objectives?

Why we did this audit

Electricity generation is the largest contributor to Victoria's greenhouse gas emissions. Managing an orderly transition to renewable energy is crucial to reaching net zero while avoiding major disruptions to the Victorian economy and community.

The Victorian Government's 2024 publication Cheaper, Cleaner, Renewable: Our Plan for Victoria's Electricity Future lays out its plan to transition away from fossil fuels and deliver a reliable electricity system.

The Victorian Government has also set renewable energy targets in the Renewable Energy (Jobs and Investment) Act 2017 (the Act). Under the Act, Victoria must generate 25 per cent of its electricity from renewable sources by 2020, 40 per cent by 2025, 65 per cent by 2030 and 95 per cent by 2035.

The Act also sets progressive, multi-year targets for offshore wind generation capacity and energy storage capacity.

Victoria is due to achieve its 40 per cent target by the end of 2025. We did this audit to see if Victoria is on track to meet its renewable energy targets, and to assess the government's plans for achieving future targets while meeting Victoria’s electricity needs.

Key background information

Source: VAGO, based on the Act and information from the Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action.

What we concluded

Victoria is on track to meet its renewable energy target in 2025, but meeting future targets will be more difficult.

In the Australian Energy Market Operator’s ‘committed and anticipated developments’ reliability assessment, Victoria has enough energy supply to meet its needs out to 2030.

But this depends on key projects being completed on time. While new projects will increase energy generation and storage capacity, many projects face delays. This also does not allow for demand that is higher than forecast or incorporate other known risks. This includes gas shortages, which are expected from 2026, as well as planned power plant maintenance and adverse weather conditions.

If these risks are not successfully managed, Victoria would be more likely to face electricity shortfalls after Yallourn coal-fired power station closes in mid-2028.

The Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (the department) has not fully considered risks in its planning, nor has it factored in contingencies should risks arise.

To meet Victoria’s future targets and make sure electricity supply meets demand, the department should develop contingency plans to address known risks.

Video presentation

1. Our key findings

What we examined

Our audit followed 2 lines of inquiry:

- Is progress towards the government’s renewable energy and storage objectives on track?

- Is the government's plan designed to achieve its renewable energy and storage objectives, and electricity obligations?

To answer these questions, we examined:

- Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action (the department)

- SEC Victoria (SEC).

Identifying what is working well

In our engagements we look for what is working well – not only areas for improvement.

Sharing positive outcomes allows other public agencies to learn from and adopt good practices. This is an important part of our commitment to better public services for Victorians.

Units of energy

Gigawatt (GW): A unit of power equal to one billion watts, which measures how fast energy is produced or consumed.

Gigawatt hour (GWh): Represents the amount of energy produced or consumed at a given rate of power over a period of time. GW are converted to GWh by multiplying GW by the number of hours the power was used.

Megawatt (MW): One-thousandth of a GW, or one million watts.

Megawatt hour (MWh): MW are converted to MWh by multiplying MW by the number of hours the power was used.

Terawatt hour (TWh): One thousand GWh.

Terajoule (TJ): A unit of energy equal to one trillion joules.

Background information

Figure 1: Key commitments and events timeline

Source: VAGO, based on the Renewable Energy (Jobs and Investment) Act 2017 (the Act) and information from the department.

Victoria's targets and obligations

The Victorian Government legislated the state’s renewable energy targets in the Act, which Figure 2 shows. The targets cover how much energy:

- is generated from renewable sources

- offshore wind farms can produce

- can be stored and dispatched.

Figure 2: Victoria’s renewable energy targets

| Year | Renewable energy | Offshore wind energy | Energy storage |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 25% | no target | no target |

| 2025 | 40% | no target | no target |

| 2030 | 65% | no target | 2.6 GW |

| 2032 | no target | 2 GW | no target |

| 2035 | 95% | 4 GW | 6.3 GW |

| 2040 | no target | 9 GW | no target |

Source: VAGO, based on the Act.

Victoria’s electricity network must also meet technical reliability and security requirements under the National Electricity Rules. This includes the reliability standard, which requires that states have enough electricity supply to meet 99.998 per cent of expected demand over a financial year. Breaching the standard increases the risk of blackouts.

The National Electricity Market

The Victorian electricity network is part of the National Electricity Market (NEM). The NEM is a wholesale electricity market covering Victoria, New South Wales, Queensland, South Australia, Tasmania and the Australian Capital Territory.

The Australian Energy Market Agreement outlines NEM governance. It separates responsibility for:

- energy policy

- regulation

- system operation

- enforcement and compliance.

The Energy and Climate Change Ministerial Council oversees 3 key market bodies (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: NEM bodies

| Body | Role |

|---|---|

| Australian Energy Regulator | Regulates the wholesale and retail energy markets and networks to ensure consumers have access to a reliable, secure and affordable market. |

Australian Energy Market Commission

| Develops the rules by which energy markets must operate. This includes setting reliability and security standards for the NEM.

|

Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO)

| Manages the day-to-day operations of NEM systems (and gas market systems) to meet security, reliability and prudential requirements. AEMO's operational and system planning roles include:

|

Source: VAGO, based on information from AEMO, the Australian Energy Market Commission and the Australian Energy Regulator.

Responsibility for Victoria’s energy transition

Under the Australian Energy Market Agreement, the Victorian Government sets the direction of Victoria's renewable energy transition. So far this has mostly involved setting targets and developing policy and legislation (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Responsibility for Victoria's energy transition

| Agency | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

The department

| Lead agency for Victoria's transition to renewable energy. The department:

|

AEMO

| In Victoria, AEMO (as AEMO Victorian Planning) also planned and directed upgrades to the Victorian transmission network.

|

VicGrid

| VicGrid assumed responsibility for planning the Victorian transmission network in late 2025, which includes:

|

SEC

| Government-owned renewable energy company that invests in delivering new infrastructure. This includes delivering 4.5 GW of new renewable energy capacity by 2035, including at least 1 GW of new storage capacity.

|

Generators

| Generators make offers to sell electricity into the market. AEMO schedules the lowest-priced generation available to meet demand.

|

Private developers and investors

| Private developers and investors including listed energy companies respond to price signals and seek to maximise profits for shareholders, including in asset investment decisions. This includes:

|

Source: VAGO.

Responsibility for the reliability and security of Victoria’s electricity supply

Sufficient investment in electricity generation, storage and demand response is a fundamental requirement for maintaining a reliable energy supply.

The NEM Framework sets out the rules, governance and institutions to facilitate this investment and allow the NEM to operate safely, reliably and efficiently.

Under the National Electricity Law and National Electricity Rules, the 3 NEM bodies (see Figure 3) and energy ministers share responsibilities set out in the NEM Framework.

AEMO has statutory functions including regulatory responsibilities and operational responsibility for electricity reliability and security across the NEM. This means:

- ensuring the electricity system operates within secure and reliable limits

- forecasting electricity supply and demand to estimate the level of future unserved energy (which is energy demand the network is not able to meet)

- maintaining the system so the expected level of unserved energy does not exceed reliability standards.

Although state and territory governments do not have an operational role in managing electricity reliability and security, they influence reliability and security through:

- sending investment signals, such as setting energy policy and targets

- addressing market failures through infrastructure investments, funding, regulation and market reform

- licensing and regulating retailers and generators

- input into national reliability mechanisms

- supporting emergency and back-up mechanisms to return supply to users.

In Cheaper, Cleaner, Renewable: Our Plan for Victoria's Electricity Future, the Victorian Government committed to delivering an affordable, reliable and secure electricity system for all Victorians.

The department’s outputs contribute to this through state-based programs focused on facilitating new investment and renewable energy development, energy efficiency and affordability.

Under the Victorian Government Risk Management Framework, the department is also the lead agency for managing 2 state-significant and strategic risks related to energy reliability (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: State-significant and strategic risks related to energy reliability

| Risk theme | Risk description | Risk rating |

|---|---|---|

| Disorderly energy transition | A disorderly transition to renewable energy could result in job losses, supply disruptions, price volatility for households and businesses and community resentment | Significant (severe/almost certain) |

Reliable, sustainable and affordable energy

| Ability to meet demand and deliver reliable, sustainable and affordable energy services

| Significant

|

Source: VAGO, based on State Significant Risk Interdepartmental Committee and Audit and Risk Management Committee papers.

The exit of coal-fired power stations

Coal-fired power stations are still critical to Victoria's electricity network, accounting for 59.2 per cent of electricity generation in 2023–24. Coal-fired power stations generate less of Victoria's electricity supply when wind and solar generation is high, but around 70 per cent of overnight electricity supply when wind and solar generation is low. Coal-fired power stations also stabilise the frequency and voltage of the network.

Victoria has 3 remaining coal-fired power stations:

- Yallourn Power Station (Yallourn)

- Loy Yang A

- Loy Yang B.

The government has signed agreements to close:

- Yallourn by 30 June 2028

- Loy Yang A by 1 July 2035.

There is currently no agreement to close Loy Yang B. Its scheduled closure date is 2047, but its owner, Alinta Energy, has said that it may close earlier if it is not needed.

What we found

This section focuses on our key findings, which fall into 3 areas:

1. Victoria is on track to meet its 2025 renewable energy target but it will be more difficult to meet future targets.

2. Key projects have been delayed, risking electricity shortages.

3. Victoria's reliability outlook to 2030 has improved but more investment and risk management are needed as coal-fired power stations close.

The full list of our recommendations, including agency responses, is at the end of this section.

Consultation with agencies

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views. You can read their full responses in Appendix A.

Key finding 1: Victoria is on track to meet its 2025 renewable energy target but it will be more difficult to meet future targets

Victoria is on track to meet its 2025 renewable energy target

Victoria is on track to meet its 2025 renewable energy target. Under a range of plausible scenarios, Victoria’s renewable energy share for the 2025 calendar year exceeds the 40 per cent target.

It will be more difficult for Victoria to meet its 2030 renewable energy target

The Australian Government's Capacity Investment Scheme (CIS) will be crucial for Victoria to meet the 65 per cent renewable energy target by 2030. This will require private investors to build and connect Victoria's full CIS allocation of renewable energy and storage projects in the next 4 years, plus additional Victorian Government support.

Meeting the 2030 target will also require fast-tracking 2 major new transmission upgrade programs under the Victorian Transmission Plan.

The achievement of the 2030 target also requires:

- that electricity demand does not grow faster than anticipated

- a managed closure of Yallourn including the successful management of any reliability and security issues.

Working well: Australian Government–Victoria Renewable Energy Transformation Agreement

The CIS is an Australian Government revenue-underwriting scheme to reduce financial risk for investors and accelerate investment in renewable and clean energy.

The Australian Government–Victoria Renewable Energy Transformation Agreement sets out capacity allocations under the CIS. Victoria has been allocated at least:

- 5 GW or 11 TWh of renewable generation capacity

- 1.7 GW or 6.8 GWh of 4-hour duration equivalent storage capacity.

The agreement aims to keep Victoria’s electricity system reliable and help the Victorian and Australian Governments meet their renewable energy generation and storage targets.

Transmission constraints and electricity demand growth remain significant risks to achieving the 2030 renewable energy target.

Victoria is likely to meet its 2030 storage target

There is enough new battery capacity planned that Victoria is on track to meet its 2.6 GW storage target by 2030.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding, we made one recommendation to the department about:

- collaborating with the Victorian transmission planner to facilitate enough transmission capacity to connect CIS supported projects to the grid and help Victoria to achieve its 2030 renewable energy targets.

Key finding 2: Key projects have been delayed, risking electricity shortages

Victoria will not meet its 2032 offshore wind target

The Victorian Government’s offshore wind program will not deliver the legislated 2 GW offshore wind energy target by 2032. There is still no port to support wind turbine assembly and construction. The government has also delayed offshore wind auctions, previously scheduled to commence in quarter 3 of 2025, until at least 2026.

The Victorian Government's original plan was to develop the Port of Hastings to support offshore wind development. But the Australian Government rejected this proposal on environmental grounds. The Victorian Government resubmitted a revised proposal in June 2025.

As an alternative to the Port of Hastings, the department is negotiating a multi-port strategy with Victorian and interstate ports.

Under an optimistic scenario Victoria could build 2 GW of offshore wind capacity by the end of 2033. But there is a risk of further delays.

Key transmission projects have been delayed

AEMO and the Victorian Government have planned projects to increase Victoria’s access to firm energy from other states to help offset the impact of closing coal-fired power stations in Victoria.

Access to firm energy is important when weather conditions are unfavourable for wind and solar generation.

Firm energy

Energy that is continuously available and can be readily dispatched to meet demand. Firm energy is also known as firming or dispatchable energy.

The VNI West and the Western Renewables Link are delayed from their original schedule. It is now expected that these projects will not be in service until at least 2030, 2 years after Yallourn closes.

This means that Victoria will not have expanded access to electricity from the planned hydro power station, Snowy 2.0, when Yallourn closes. Without access to long-duration storage, Victoria may not always have enough electricity available during periods of peak demand if weather conditions are unfavourable for wind and solar.

Long-duration storage

Energy storage with a duration longer than 8 hours. This is to cover long periods of lower-than-expected renewable energy availability and seasonal smoothing over weeks or months. Long-duration storage projects include hydro-electric and pumped hydro-electric storage.

Battery storage projects are on track for completion before Yallourn closes

Battery storage is a key part of the government’s plan to replace coal.

Under the agreement with the government to close Yallourn, EnergyAustralia committed to develop a 350 MW, 4 hour duration battery by 30 June 2027. Construction has started and the battery is scheduled to be operational in December 2027.

SEC has committed to invest in 4.5 GW of new renewable electricity generation and storage capacity by 2035, including 1 GW of storage by 2028. SEC is on track to meet its storage target with investments in the Melbourne Renewable Energy Hub and the SEC Renewable Energy Park – Horsham. These will deliver 600 MW and 100 MW of short-duration battery storage respectively before the end of 2027. SEC is also doing due diligence on investment opportunities with a total storage capacity of around 1 GW.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding, we made one recommendation to the department about:

- monitoring and advising government if there will be enough electricity to meet future daily needs.

Key finding 3: Victoria's reliability outlook to 2030 has improved but more investment and risk management are needed as coal-fired power stations close

AEMO forecasts that Victoria will have enough electricity to offset the exit of coal if major risks are managed

AEMO forecasts show that Victoria's reliability outlook has improved. Under the 'committed and anticipated developments' reliability assessment, AEMO no longer expects electricity shortfalls until 2030.

Working well: Investment in renewable energy projects is increasing

Continued private and government investment in renewable energy projects is improving Victoria's reliability outlook. Over 2024–25, an additional 807 MW of generation capacity and 2.3 GWh of utility storage capacity were committed or anticipated for development, according to AEMO.

As the end of 2029 is the target commercial operating date for several CIS-supported projects, a share of these projects should also be online to help address potential electricity shortfalls by the start of 2030–31.

If Australian and Victorian Government renewable energy developments proceed as planned, Victoria should have enough generation and storage for a smooth transition from coal. However, AEMO forecasts substantial electricity shortfalls beyond 2030 in the absence of continued private and government investment.

Peak demand has exceeded forecasts in recent years. In addition, AEMO's committed and anticipated developments reliability assessment assumes supply constraints including gas shortfalls and drought conditions will not limit gas-powered or hydro-electricity generation, and that planned power plant maintenance will occur outside periods of tight supply.

Key issue: Ensuring the reliability of Victoria's electricity supply will require careful risk management

Changes in electricity use, including higher-than-expected peak winter demand, are presenting challenges to the NEM. In June 2025 there was record winter peak electricity demand – around 7 per cent higher than AEMO forecast in its 'high-demand’ scenario.

If forecast gas shortfalls persist or south-eastern Australia experiences prolonged drought conditions, Victoria will face constraints on gas-powered and hydro-electric generation respectively.

There could also be constraints on electricity supply during periods of high demand if the observed scheduling of planned power plant maintenance continues.

There is little buffer in Victoria's current electricity generation and storage pipeline in the period immediately after Yallourn closes.

Victoria could face electricity shortfalls to meet peak demand if these risks materialise, which could result in load shedding (planned electricity reduction to selected areas) and blackouts.

AEMO has operational responsibility for monitoring and maintaining the reliability and security of the NEM. If there is not enough electricity generation or storage capacity, AEMO may have to intervene to meet future peak demand requirements. This will place upwards pressure on electricity prices.

Planning for Victoria’s energy transition has not adequately considered risks and uncertainties

Transitioning Victoria’s electricity supply to renewables is complex and uncertain. Although the department’s modelling has considered different scenarios, the department has not demonstrated that it considered the full extent of project delays, weather variation and contingencies in its advice.

For example, prolonged high-pressure systems, which reduce wind speeds and rainfall, are frequent over Australia’s south-east from May to October. These could reduce Victoria's onshore and offshore wind outputs for multiple days, limit battery charging and limit other states’ capacity to export electricity to Victoria. AEMO has stated that these extended still weather conditions could pose significant challenges to electricity supply in winter.

Also, the Victorian Transmission Plan’s ‘delay’ scenario assumes that new transmission projects will face no more than one year delays out to 2040. But delays could be longer. AEMO recently announced that the Western Renewables Link and VNI West transmission projects face 2-year delays and Victoria's offshore wind target is at significant risk of further delay.

AEMO and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission are also concerned that there will not be enough gas to meet Victoria's gas-powered electricity generation needs. This could mean that the current pipeline of generation and battery projects will not be enough to offset Yallourn’s closure from mid-2028.

The department has limited short-term options to address potential electricity shortfalls and guarantee reliability in Victoria’s power supply. It expects Victoria’s allocation under the CIS to strengthen supply by 2030. But in the interim from 2028, Victoria will need to rely on AEMO to safeguard Victoria's electricity supply until enough CIS projects become operational.

Addressing this finding

We made one recommendation to the department about:

- strengthening how guidance on planning under risk and uncertainty is applied to Victoria's renewable energy transition.

We also made one recommendation to the department and SEC about:

- taking steps to address forecast firm energy gaps and maintain a reliable electricity supply as coal-fired power stations close.

See Section 2 for the complete list of our recommendations, including agency responses.

2. Our recommendations

We made 4 recommendations to address our findings. The relevant agencies have accepted all recommendations in full.

| Agency responses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finding: Victoria is on track to meet its 2025 renewable energy target but it will be more difficult to meet future targets | ||||

| Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action | 1 | Collaborate with the Victorian transmission planner to facilitate the development of enough transmission capacity to connect Capacity Investment Scheme projects to the grid and enable Victoria to achieve its 2030 renewable energy and storage targets (see Section 3). | Accepted | |

| Finding: Key projects have been delayed, risking electricity shortages | ||||

| Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action | 2 | Monitor and advise government on an ongoing basis whether there is likely to be enough electricity to meet future daily needs under different peak demand, weather and project delivery scenarios (see Section 4). | Accepted | |

| Finding: Victoria's reliability outlook to 2030 has improved but more investment and risk management are needed as coal-fired power stations close | ||||

| Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action | 3 | Strengthen the application of Department of Treasury and Finance guidance on planning under risk and uncertainty to Victoria's renewable energy transition over the short and medium term. This includes planning to avoid worst-case scenarios and factoring risks and uncertainties into option analysis (see Section 5). | Accepted | |

Department of Energy, Environment and Climate Action SEC Victoria | 4 | Take steps to address forecast firm energy gaps and maintain a reliable electricity supply as coal-fired power stations close, factoring in risks and uncertainties in line with Department of Treasury and Finance guidance (see Section 5). | Accepted | |

3. Meeting Victoria's 2025 and 2030 targets

Victoria is on track to meet its target of 40 per cent of the electricity generated in the state to come from renewable sources by the end of 2025.

The pathway to 65 per cent renewable energy generation by 2030 is less certain. Achieving the target will depend on the CIS delivering all of Victoria's renewable energy and storage allocation, plus additional Victorian Government support.

Reaching the 2030 target also requires on-time investment in transmission infrastructure so enough new projects can connect in time and supply electricity to the grid.

Victoria is likely to meet its target for 2.6 GW of storage capacity by 2030.

Covered in this section:

- Victoria is on track to meet its 40 per cent renewable energy target in 2025

- It will be more difficult to achieve future renewable energy targets

- Victoria is on track to meet its energy storage targets

Victoria is on track to meet its 40 per cent renewable energy target in 2025

2025 renewable energy target

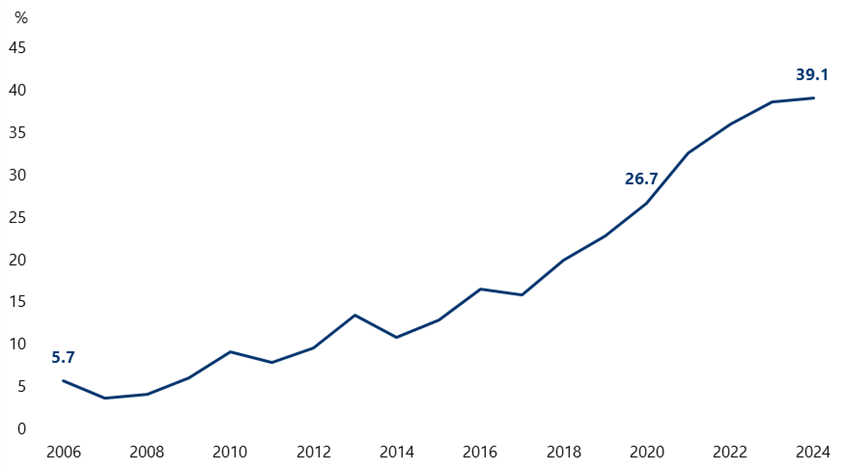

The Act sets a target that 40 per cent of the electricity generated in Victoria will come from renewable sources by 2025. The department reported that Victoria achieved a renewable energy share of 39.1 per cent across the 2024 calendar year (see Figure 6).

Figure 6: Percentage of renewable energy out of the total energy generated from 2006 to 2024

Source: VAGO, based on department data.

The department’s reporting is based on publicly available NEM data from AEMO and statistics from the Australian Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water for data AEMO has not reported.

These are reputable sources and the data is high quality.

The department also subjects renewable energy target progress reports to external review. The latest external review validated the accuracy of the Victorian Renewable Energy Target 2023/24 Progress Report, which included renewable energy target values for 2013–14 through to 2023–24.

Using the same data and the department’s methodology, we were able to reproduce the department’s reported renewable share for 2020 and 2024. This gives reasonable assurance that the department’s renewable energy target progress reporting is reliable.

We extended our modelling to estimate whether Victoria is on track to achieve a 40 per cent renewable share across 2025 under different demand and electricity generation scenarios.

Based on our analysis, there is a range of plausible scenarios for which Victoria’s renewable energy share for 2025 exceeds the renewable energy target (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Our renewable generation share modelling, under different scenarios, for 2025

| Electricity generation | Capacity growth assumption | Renewables share |

|---|---|---|

| 5% increase | The department | 41.5% |

| Less than 1% increase | 44.9% | |

| 3% increase | 43.9% | |

| Less than 1% increase | AEMO NEM generation information

| 43.5% |

| 3% increase | 42.5% | |

| Less than 1% increase | The department, assuming:

| 43.8% |

| 3% increase | 42.6% |

Note: AEMO’s assumptions for wind and solar farms are more conservative than the department’s. The Golden Plains wind farm is the largest renewable energy project scheduled in Victoria for 2025.

Source: VAGO, using data from AEMO and the department.

It will be more difficult to achieve future renewable energy targets

2030 renewable energy target

The pathway to meeting the 2030 renewable energy target is less certain than for 2025 and will rely on the CIS.

The Australian Government–Victoria Renewable Energy Transformation Agreement sets out capacity allocations under the CIS. Victoria has been allocated at least:

- 5 GW or 11 TWh of renewable generation capacity

- 1.7 GW or 6.8 GWh of 4-hour duration equivalent storage capacity.

In 2024, the department advised the government that Victoria was tracking towards a 58 per cent renewable energy share in 2030 following the closure of Yallourn in 2028. The department also advised that Victoria's full CIS allocation could increase Victoria's renewable energy share to 61 per cent. However, additional Victorian Government support will be necessary to reach 65 per cent.

In its advice, the department estimated that Victoria will require the completion of $1.2 billion in transmission upgrades by 2030 to reduce network curtailment and improve the economic viability of proposed CIS projects.

VicGrid is proposing to fast-track new transmission projects under the Victorian Transmission Plan, including the:

- Western Victoria reinforcement program, which will support the connection of onshore wind and solar generation across western Victoria

- Eastern Victoria reinforcement program, which will ensure the connection and security of supply in eastern Victoria, including the Gippsland offshore wind area.

This is in addition to the already-committed Western Renewables Link and VNI West projects.

Greater-than-expected growth in demand for electricity could be a significant risk to meeting the 2030 target. Increased electricity demand leads to an increased reliance on generation from existing assets, including coal and gas generation.

Victoria is on track to meet its energy storage targets

2030 energy storage target

Victoria has enough battery capacity planned to make it likely that it will meet its target to achieve 2.6 GW of energy storage by 2030.

AEMO data showed 1 GW of battery storage capacity in service before July 2025, with up to 4.7 GW in new capacity scheduled to come online by 2030.

If completed on time, this means up to 5.8 GW of one-hour to 4-hour battery projects may be online by 2030 – more than double the 2.6 GW target.

4. Renewable energy infrastructure

Victoria will not meet its target for 2 GW of offshore wind energy by 2032.

It will take until at least the end of 2033 to deliver 2 GW of offshore wind due to delays finding a suitable port and opening offshore wind auctions. These delays also place the 2035 and 2040 offshore wind targets at risk.

Battery storage is a key part of the government’s plan to replace coal. SEC is on track to meet its target to deliver 1 GW of battery storage by 2028. Another 350 MW, 4-hour duration battery is also on track to be completed before Yallourn closes.

The Victorian Government included 3 key transmission projects in its plan to move away from coal while maintaining a reliable electricity supply. But 2 of these projects are off track.

Covered in this section:

- Victoria will not meet its first offshore wind target

- Key battery storage projects are on track to be completed before Yallourn closes

- Victorian Renewable Energy Target auction projects are off track

- Key transmission projects have been delayed

Victoria will not meet its first offshore wind target

Delays to offshore wind targets

Victoria will not meet its target for 2 GW of offshore wind energy by 2032. This is because of delays confirming a suitable port to support the construction of offshore wind farms and delays opening offshore wind auctions.

It will take until at least the end of 2033 for Victoria to build 2 GW of offshore wind capacity, but there is a risk of further delays due to port issues and funding uncertainty.

Offshore wind port options

The Victorian Government's original strategy was to develop an offshore wind port, known as the Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal, at the state-owned Port of Hastings. Construction was due to start in February 2026 and finish by December 2028.

In October 2023 the Port of Hastings Corporation, which manages the port, referred the proposed Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal to the Australian Minister for the Environment and Water.

The Port of Hastings Corporation needed the Minister’s approval because of the terminal’s potential impact on nearby Ramsar-protected wetlands. In January 2024 the Minister rejected the referral due to unacceptable impacts on the wetlands.

The department and the Port of Hastings Corporation are now pursuing 2 port strategies simultaneously (see Figure 8).

Figure 8: The Victorian Government’s offshore wind port strategies

| Strategy | Details | Indicative schedule |

|---|---|---|

| Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal (Port of Hastings) | The Port of Hastings Corporation has redesigned the proposed Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal and has referred its design to the Australian Government. | The department has assessed that the Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal could be ready for operation by the end of 2030, subject to a successful second referral and further analysis of infrastructure upgrades. |

| Multi-port solution | The department is negotiating with Victorian and interstate ports, with a view to different ports delivering different components. | The department has assessed that a multi-port solution could be operational in 2029, subject to the government confirming its port strategy and reaching agreements with port operators. |

Source: VAGO.

The Port of Hastings Corporation submitted a revised proposal for the Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal in June 2025.

The department has informed offshore wind developers that it will provide details of the government’s preferred port strategy before opening auctions, originally scheduled for quarter 3 of 2025. But the Australian Government is yet to decide if it will allow the revised Victorian Renewable Energy Terminal to proceed. The department has also not yet negotiated multi-port agreements.

The government has delayed opening the auctions until at least 2026.

Further delays finalising a port solution and opening auctions will reduce the achievability of 2 GW by the end of 2033 (and 4 GW by 2035) given the department assumes a maximum feasible construction rate of 1 GW per year.

Key battery storage projects are on track to be completed before Yallourn closes

SEC battery storage projects

SEC is committed to investing in 4.5 GW of new renewable electricity generation and storage capacity by 2035, including 1 GW of storage by 2028.

SEC is on track to deliver its 2028 storage target. It has committed to investments in 700 MW of electricity storage capacity across 2 projects, which it plans to deliver by 2027.

It is also identifying and assessing new investment opportunities. As of March 2025, it was undertaking due diligence on opportunities with a total storage capacity of around 1 GW.

| The … | aims to deliver … | by … | The delivery date is … | which means … |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Melbourne Renewable Energy Hub | 3 battery energy storage systems totalling 600 MW or 1.6 GWh | December 2025. | on track | the batteries will be online to help meet peak summer demand in 2025–26. |

| SEC Renewable Energy Park – Horsham | a 118.8 MW solar farm and a 100 MW or 200 MWh battery energy storage system | November 2027. | on track | the project will be online to help meet demand when Yallourn closes. |

The Wooreen battery

In March 2021, the state entered into a structured transition agreement with EnergyAustralia to manage the scheduled Yallourn closure by 30 June 2028.

Under the agreement, EnergyAustralia committed to procure, construct and operate a 350 MW, 4 hour duration battery (known as the Wooreen battery). The Victorian Government and EnergyAustralia agreed that it would be operational by 31 December 2026 but later agreed to a revised date of 30 June 2027.

Construction has started; however, the Wooreen battery is not expected to be online until December 2027. This will still be before the scheduled closure of Yallourn.

Victorian Renewable Energy Target auction projects are off track

VRET2 projects progress

The second Victorian Renewable Energy Target auction (VRET2) is off track. It will not contribute as expected to:

Victoria meeting its 2025 renewable energy target

- realising the Victorian Government's commitment to source 100 per cent renewable energy for all government operations by 2025.

- The department also expected VRET2 battery projects to help offset the estimated firm energy gap after Yallourn’s closure. But this is at risk.

The department’s original plan was that VRET2 would support 6 privately developed renewable energy projects to start operating by the end of 2024. But Glenrowan Solar Farm was the only VRET2 project to start operations by the end of 2024.

Two other VRET2 projects now have target operating dates in 2027, including the SEC Renewable Energy Park – Horsham. The remaining 3 projects have no confirmed target operating dates (see Figure 9).

Figure 9: Status of VRET2 projects

| Announced project | Status |

|---|---|

Glenrowan Solar Farm

|

|

Fulham Solar Farm

|

|

Horsham Solar Farm

|

|

Derby Solar Farm

|

|

| Frasers Solar Farm | |

| Kiamal Solar Farm |

Source: VAGO, based on information from the department.

Key transmission projects have been delayed

Additional transmission infrastructure

Victoria requires significant expansion in renewable electricity generation and storage to meet its electricity needs as coal-fired power stations close. Extensions and upgrades to Victoria’s transmission network are necessary to enable this expansion.

The government’s plans to close Yallourn and Loy Yang A assumed the timely completion of key transmission projects to ensure a reliable electricity supply.

| The … | This will … |

|---|---|

|

|

| Marinus Link will run from Victoria to Tasmania. | expand Victoria’s access to long-duration storage from Tasmania’s hydro-electric resources. |

AEMO, AusNet and Marinus Link Pty Ltd are managing these projects in consultation with the Victorian Government.

As well as existing projects, the Victorian Transmission Plan proposes around a $1.2 billion investment in new transmission capacity by 2030 to facilitate new projects under the CIS.

Delays to transmission infrastructure

The department assumed the following completion dates for these transmission projects:

- Western Renewables Link by 2025, later revised to 2027

- VNI West by June 2028

- Marinus Link Stage One by 2031–32 and Stage Two by 2034–35.

But both the Western Renewables Link and VNI West face delays (see Figure 10).

Figure 10: Transmission project timelines

| Project | Construction stage | Expected completion date (as of 2021) | Updated completion date (as of July 2025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Western Renewables Link | not started | 2025 | 2029 |

| VNI West | not started | 2027–28 | 2030 |

| Marinus Link Stage One | not started | 2031–32 | 2030 |

| Marinus Link Stage Two | not started | 2034–35 | 2032 |

Source: VAGO, based on public construction timelines.

The Western Renewables Link timeline now expects construction to start in quarter one of 2027 and finish in quarter 4 of 2029. The project requires a planning scheme amendment before construction can start. The timeline expects the Minister for Planning to finalise this amendment in late 2026.

VNI West’s commissioning depends on the Western Renewables Link coming online first. As of July 2025, the expected completion date for VNI West is late 2030.

Marinus Link’s 3 shareholders – the Victorian, Tasmanian and Australian Governments – issued a final investment decision to proceed with Marinus Link Stage One in August 2025. Pending the timely completion of further financial and regulatory steps, construction should start in 2026.

5. Meeting Victoria's electricity needs

Victoria's reliability outlook out to 2030 has improved since 2024. However, indicative forecasts beyond 2030 show widening reliability gaps if Australian and Victorian Government schemes do not deliver their intended generation and storage capacity.

With risks such as forecast gas shortages, uncoordinated power plant maintenance and adverse weather conditions, the state still faces a risk of electricity shortfalls immediately after Yallourn closes.

The CIS should address these risks by 2030, but if the balance between supply and demand worsens beyond what is currently projected, then AEMO may need to step in to safeguard reliable electricity.

The department’s planning has allowed little margin for error in demand forecasts and lacked contingency measures for significant project delays. The Victorian Transmission Plan addresses some of these shortcomings but still relies on some optimistic assumptions.

Covered in this section:

- Victoria's reliability outlook to 2030 has improved but there is still a significant risk of electricity shortages after Yallourn closes

- Planning for Victoria’s renewable energy transition has not adequately factored in risk and uncertainty

Victoria's reliability outlook to 2030 has improved but there is still a significant risk of electricity shortages after Yallourn closes

Reliability standards

A reliable electricity system has enough generation, demand response and network capacity to meet consumer demand in all conditions. It is about ensuring there is enough generation capacity and that the transmission and distribution networks can reliably deliver electricity to customers when they need it.

An electricity shortfall can lead to load shedding or blackouts.

Load shedding

Planned electricity reduction to selected areas to protect the electricity network from long-term damage and widespread consumer outages.

There are 2 standards to understand the reliability of the NEM. Both are based on the amount of demand that the electricity network is forecast to be unable to meet. This is known as unserved energy.

Reliability standard

Forecast unserved energy should not be more than 0.002 per cent of energy demanded in any financial year. This is equivalent to an annual system-wide 7-minute outage at peak demand.

Interim reliability measure

Forecast unserved energy should not be more than 0.0006 per cent of energy demanded in any financial year. This standard applies until 30 June 2028.

AEMO’s reliability forecasts

AEMO publishes annual forecasts for unserved energy in its annual ESOO. These forecasts inform the department’s advice on electricity reliability risks. The department is responsible for assessing risks and uncertainties associated with AEMO’s forecasts and assumptions and appropriately advising the government on the implications.

To produce its forecasts, AEMO simulates a wide range of future operating conditions based on different levels of demand, historic weather, power station outages and supply assumptions. AEMO uses these simulations to forecast unserved energy in future years using probability weighted annual averages, including under a committed and anticipated developments scenario.

Committed and anticipated developments scenario

This reliability assessment includes electricity supply projects that are sufficiently progressed to meet at least 3 of AEMO’s criteria relating to planning, construction, land, contracts and financing.

In the committed and anticipated developments reliability assessment in the 2024 ESOO, AEMO forecast that Victoria would face electricity shortfalls against the interim reliability measure from 2027–28 and against the reliability standard from 2028–29, increasing after Yallourn closes.

But in the 2025 ESOO, AEMO forecasts that under the same assessment electricity shortfalls against the reliability standard will not occur until 2030–31 (see Figure 11).

Under the committed and anticipated developments assessment, AEMO forecasts that 1.7 GW of new generation capacity and 7 GWh of new battery projects will be delivered by mid-2028. It expects this to outweigh the negative effects of forecast higher electricity demand and delays to transmission projects.

These figures do not include new CIS-supported projects that have not yet met AEMO’s criteria.

While Victoria’s reliability outlook to 2030 has improved, the outlook is sensitive to key supply and operational risks.

In the 2025 ESOO, AEMO modelled the impact of risk sensitivities and reported:

| If either ... | then ... |

|---|---|

| the current pattern of planned generator maintenance continues during high demand periods | Victoria could face modest breaches of reliability standards, from 2025–26, which could significantly worsen from 2028–29 with Yallourn’s closure (see Figure 11). |

| forecast gas shortages occur, limiting peak gas-powered electricity generation | |

| drought conditions limit hydro electric generation |

Figure 11: Forecast unserved energy under committed and anticipated developments scenario 2025–26 to 2034–35

Note: Gas shortfalls and drought sensitivities build on the generator maintenance sensitivity.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO’s 2025 ESOO workbook.

In the 2025 ESOO, AEMO also forecasts unserved energy under a government schemes and actionable developments scenario.

Government schemes and actionable developments scenario

This reliability assessment assumes the on-time and in-full delivery of government schemes, including all Victoria’s CIS-supported projects, Victorian Government schemes, actionable transmission projects and committed and anticipated projects. The scenario also includes AEMO’s projections of rising household and behind-the-meter battery adoption.

This scenario forecasts that the risk of electricity shortfalls will be within the reliability standards to 2034–35 (see Figure 12).

But it assumes all government schemes and projects meet target dates. In some cases, target dates may reflect optimistic scenarios and may not reflect the latest information. For example, this scenario assumes 2 GW of offshore wind capacity will be available by 2032. But this will take until at least 2033, if there are no further delays.

Figure 12: Forecast unserved energy under government schemes and actionable developments scenario 2025–26 to 2034–35

Note: Gas shortfalls and drought sensitivities build on the generator maintenance sensitivity.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO’s 2025 ESOO workbook.

So while Victoria’s reliability outlook has improved, there is still a risk of near-term electricity shortfalls when Yallourn closes.

The extent of risk will become clearer as the progress of CIS-supported projects becomes evident. Importantly, the Australian Minister for Climate Change and Energy announced Victorian projects for:

- 0.6 GW of 4-hour duration equivalent storage in December 2024

- 1.6 GW of renewable generation capacity in December 2024

- 1.3 GW of 4-hour duration equivalent storage capacity in September 2025

- 1.2 GW of renewable generation capacity in October 2025.

Projects that are targeting commissioning in the 2030s are less likely to meet AEMO’s criteria relating to planning, construction, land, contracts and financing, to qualify as a committed and anticipated development. However, AEMO’s forecasts for 2030–31 to 2034–35 predict substantial electricity shortfalls against reliability standards under the current committed and anticipated developments pipeline of projects, as Figure 11 shows. These shortfalls exceed those AEMO published in its 2024 ESOO because of an upwards revision to forecast electricity demand (see Figure 13).

This highlights the need for continued private investment and government action to secure Victoria's electricity supply as coal-fired power stations close. These forecasts do not yet reflect the scheduled Loy Yang A closure by 1 July 2035.

Figure 13: Forecast electricity shortfall under the committed and anticipated developments reliability assessment in the 2024 and 2025 ESOOs

Note: The ESOO provides a 10-year outlook. There is only one bar in 2034–35 as the ESOO 2024 only provided forecasts to 2033–34.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO's 2024 and 2025 ESOO workbooks.

Coal’s exit

The Victorian Government negotiated structured transition agreements with the operators of Yallourn and Loy Yang A to close by 30 June 2028 and 1 July 2035 respectively.

As part of its advice on the timing of the closures, the department commissioned modelling to give assurance that new renewable energy projects would offset the closures.

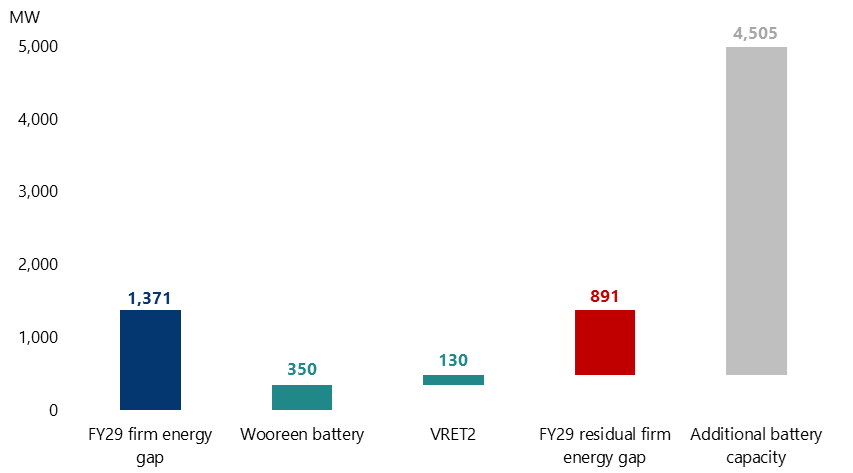

Advice in 2020 estimated that closing Yallourn would lead to a firm energy gap of 1.37 GW during a summer peak demand event lasting longer than 2 hours.

The advice made several assumptions about new infrastructure and future demand and how these factors may offset the closure of Yallourn.

| The advice assumed that … | which would … | But … |

|---|---|---|

| VNI West and the Western Renewables Link, the Wooreen battery and VRET2 projects would be operational before Yallourn closes | reduce the shortfall to a firm energy gap of 476 MW and help ensure a reliable electricity supply. |

|

We replicated the department’s 2020 analysis using the same method and current information on proposed projects.

We estimate a firm energy shortfall of 891 MW against the department’s advice (see Figure 14).

AEMO data indicates there could be up to 4,505 MW (or 10,453 MWh) of additional battery storage capacity available in Victoria by winter 2028. This includes phase one of the Melbourne Renewable Energy Hub, which will deliver 600 MW (or 1,600 MWh) of storage capacity. These projects will add to the Wooreen battery and VRET2 batteries.

With a 2-hour window as per the department’s analysis, this battery capacity will more than offset Yallourn's closure.

Figure 14: Estimated firm energy gap after Yallourn closes

Note: Based on a summer peak demand event lasting longer than 2 hours. FY29 means financial year 2028-29.

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s methodology, analysis of the Yallourn structured transition agreement and AEMO data.

Demand may exceed supply for periods longer than 2 hours. During these periods, the pipeline of 2-hour and 4-hour batteries might not be enough to offset Yallourn's closure and other sources of electricity may be required to ensure a reliable electricity supply.

In 2021, the department commissioned modelling to examine the impact of closing Loy Yang A and Loy Yang B during a summer peak demand event lasting longer than 2 hours. The report estimated the:

- firm energy gap in 2035 if both or either plant closes

- added capacity needed to ensure reliability.

The report found that forecast growth in renewable electricity generation and the completion of VNI West and Marinus Link Stage One and Stage Two can offset Loy Yang A's 2035 closure.

It is still too early to assess if the assumed growth is likely and when Marinus Link will be in service.

Weather variation

AEMO has stated that weather variation, such as extended dark and still weather conditions, will pose significant challenges to electricity supply.

AEMO has stated that a reliable electricity system needs to have an extra level of reserve energy, over and above the level of electricity demand at any given time, to act as a buffer to meet challenging conditions.

We requested that the department provide analysis of potential electricity supply issues during unusually prolonged dark and still periods in winter. The department did not provide this analysis.

Therefore, we used data from 29–30 July 2024 as an indicative case study to understand the possible impact on electricity supply of severe dark and still weather conditions after Yallourn closes.

On these days there was a high-pressure system over south-eastern Australia, resulting in low wind. Solar output was also low given the time of year. Victoria relied heavily on coal, gas, hydro electric and batteries to meet demand. This infrastructure ran close to full capacity but there was still tight supply, particularly during the evening peak.

As it is reasonable that these conditions will recur, we modelled whether the electricity system could meet Victoria’s demand under identical conditions immediately after Yallourn closes.

This differs from AEMO’s modelling approach. AEMO conducts simulations, based on its supply assumptions, to estimate probability-weighted average unserved energy for a year.

We considered 2 demand growth scenarios:

- the 2025 ESOO forecast for 5.5 per cent growth in demand

- a 10 per cent probability of exceedance winter demand.

Probability of exceedance

The probability, as a percentage, that maximum demand will happen in a particular period (for example, due to weather conditions). A 10 per cent probability of exceedance forecast is expected to happen one year in 10 on average. A 50 per cent probability of exceedance maximum demand forecast is expected to happen one year in 2 on average.

We examined if potential projects with a start date prior to July 2028 and an expansion in generation from existing assets would offset Yallourn’s closure and address overnight gaps (see Figure 15).

There are up to 11,400 MWh of committed, anticipated and proposed battery projects that may come online by July 2028 and around 3,000 MWh of electricity could come from other states overnight. If there is enough gas supply, gas-powered electricity generation could run at high capacity overnight.

But hydro-electric generation already ran all day, meaning that water supply, pumping and downstream constraints could limit the ability of hydro-electric to address the overnight gap.

If all other things are held constant, this results in an estimated overnight gap of around 2,720 MWh or an average firm capacity gap of around 182 MW under the ESOO demand forecast and around 11,240 MWh or 700 MW under the 10 per cent probability of exceedance scenario.

Figure 15: Estimated supply and demand in winter under cold, dark and still wind conditions

Note: This is an indicative case study for the purpose of examining the risk of demand exceeding supply – i.e., a capacity gap – should similar conditions to those experienced in the past be experienced in the future. It is not intended to replace detailed modelling undertaken by the department or others.

Figure 15 does not display the second 10 per cent probability of exceedance winter demand scenario. *Assumes sufficient capacity interstate to import electricity overnight. **Assumes delays to planned battery projects are limited and battery capacity is optimally discharged to minimise firm capacity gaps.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO NEM data from 29–30 July 2024, AEMO’s 2024 Integrated System Plan and NEM Generation Information July 2025.

We have assumed significant growth in gas generation in response to supply issues. If a further sustained increase in gas generation is feasible, this may address or lessen the gap. However, it is not clear this is feasible given the age of Victoria’s gas plants and forecast gas supply issues.

Our analysis does not factor in supply issues such as asset outages, project delays or higher demand than forecast. These could contribute to larger firm capacity gaps.

But our analysis shows that Victoria faces tight electricity supply as coal exits, even under an optimistic scenario of new project entry. In overnight, still periods when renewable generation is low, this could mean electricity demand exceeds supply.

Addressing firm capacity gaps

In our case study example in Figure 15, we assume that:

- gas-powered electricity generation output peaks at 1.5 GW

- hydro-electric generation peaks at 1.5 GW

- Victoria imports an hourly average of 200 MW of electricity from interstate.

Victoria currently has up to:

- 2.4 GW of gas-powered electricity generation capacity

- 2.3 GW of hydro-electricity generation capacity

- 2.9 GW of transmission import capacity.

But operational constraints mean it is unlikely that these sources will be able to operate near their maximum capacity by 2028. They are unlikely to deliver the firm energy Victoria may need under overnight cold and still weather conditions.

Addressing firm capacity gaps

Between 29 and 30 July 2024, an outage at Yallourn and low renewable electricity generation led

to increased gas-powered electricity generation, which produced 21.7 GWh of electricity over the

24-hour period to 9 am, 30 July 2024.

This reflected an afternoon average of 760 MW, increasing to a peak of 1.5 GW from 6 pm to

9 pm. Gas-powered generation then fell to an average of 770 MW from 10 pm to 6 am.

In our case study, we assumed that gas-powered electricity generation could maintain an

overnight average of 1.4 GW. But by 2028 Victoria’s gas-powered electricity plants will, on average,

be 30 years old. In recent years the plants’ maximum sustained overnight output has been 1.4 GW,

which happened under stressed market conditions from 26 to 27 June 2025.

By 2028, AEMO forecasts that gas supply in Victoria will fall 15.6 per cent while demand for

gas-powered electricity generation in Victoria could double.

AEMO forecasts suggest that on high-demand days in 2028, gas demand could exceed supply by

45.5 per cent or 498 TJ per day (see Figure 16).

Figure 16: Actual and forecast peak day gas demand and supply in Victoria

Note: Chart displays AEMO peak day forecasts for high-demand days from the Victorian Gas Planning Report. AEMO has noted that seasonal peak gas generation has the potential to coincide with a peak system demand day, especially during winter.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO actual data and forecasts from the Victorian Gas Planning Report.

AEMO has an obligation to ensure gas demand does not exceed supply. This is to meet pipeline pressure and safety standards and to avoid extended gas pipeline restart processes. If the gas supply was interrupted, it could take days before access is returned and gas can be used again.

It is difficult for AEMO to limit household and business gas usage. If there is a gas shortage AEMO may need to limit gas-powered electricity generation by up to 498 TJ per day to balance supply and demand.

This could mean that Victoria’s gas-powered electricity generators can only operate at 6 per cent of the required capacity on high-demand days.

Even in a lower-demand scenario and a mild winter, forecasts suggest that gas-powered electricity generators could only be able to operate at 26 per cent of the required capacity at peak times.

AEMO forecasts suggest gas supply could get worse in 2029, leading to more firm energy capacity gaps. AEMO may need to undertake significant load shedding and a substantial proportion of electricity customers could experience overnight blackouts.

This also does not factor in higher-than-anticipated household and business gas use. AEMO assumes that households and businesses will reduce their peak gas usage by 12 per cent (140 TJ per day) by 2029. This reflects government interventions to reduce gas demand under the Gas Security Statement and Gas Substitution Roadmap and their potential impacts, including:

- new requirements for new homes and government buildings to be all-electric from 2024, with no gas connection

- changes to the Victorian Energy Upgrades program from 2023, including removing gas appliances, and new incentives for switching from gas to electric appliances.

But AEMO forecasts that gas supply will fall 31.7 per cent (400 TJ per day) by 2029 because of a fall in gas supply from Gippsland. This means forecast gas supply is significantly less than demand.

While the department has advised the government on gas supply risks, it is not clear to what extent responses will address forecast shortages.

National energy ministers are currently considering a potential amendment to AEMO's powers to bolster east-coast gas supply.

Hydro-electricity constraints

On 29 July 2024, Victoria’s hydro-electricity output reached one of its highest levels. The total output was 18.1 GWh from 9 am to 9 am between 29 and 30 July 2024, with maximum output reaching 1.5 GW.

In our scenario, we did not assume more hydro-electricity output than 18.1 GWh because of operational and water-licensing constraints at Victoria’s largest hydro-electricity power stations, Murray 1 and 2.

These stations provided 89.7 per cent (16.2 GWh) of Victoria’s hydro-electricity supply from 9 am to 9 am between 29 and 30 July 2024.

Murray 1 and 2 rely on pumping water from Lake Jindabyne to Geehi Reservoir before releasing it downstream to power the stations’ turbines. On any given day, hydro-electricity output from Murray 1 and 2 production is limited by:

- pumping limits under the Snowy Water Licence

- the total water volume available in Geehi Reservoir and downstream capacity.

When Geehi Reservoir is full, Murray 1 and 2 can operate at maximum capacity for around 14 to 16 hours under normal conditions.

Up to 13 GWh of additional electricity could be provided overnight if AEMO directed Murray 1 and 2 to run overnight at their maximum output and there was sufficient downstream capacity. It would also need to be allowed under the Snowy Water Licence.

This level of output would be significantly higher than the highest water use and generation previously delivered by Murray 1 and 2.

But it would only address around 43 per cent of the estimated overnight firm capacity gap under the 10 per cent probability of exceedance winter demand scenario (30 GWh). Fully covering the gap in 2028 would still require:

- gas-powered electricity to be generated overnight at its highest level (providing an added 6 GWh)

- sufficient electricity to import from other states overnight (providing 3 GWh)

- planned battery projects commissioned before 30 June 2028 operating at high capacity to deliver 9 GWh overnight.

This would also reduce water storage in the Geehi Reservoir. While additional water could be pumped from Lake Jindabyne during the day, lower water storages would limit the capacity of Murray 1 and 2 compared to the previous night.

If Victoria experienced a second night of similar low-wind conditions, it would have lower hydro electric capacity and its dependence on already constrained gas-powered electricity generation and interstate electricity imports would increase.

Other factors that could limit overnight hydro-electricity output include:

- below-average seasonal rainfall or changes in channel capacity

- network security issues

- any planned or unplanned maintenance and outages.

Electricity import constraints

On 29 July 2024, Victoria exported electricity interstate despite constrained supply, including overnight (1.7 GWh).

During winter nights where there has been one or more coal unit outages in Victoria, the state has continued to export electricity overnight 82.8 per cent of the time.

During these nights, Victoria was a net overnight importer of electricity from interstate only 17.2 per cent of the time. On only 6.5 per cent of these nights, has Victoria imported more than 4 GWh net overnight (see Figure 17).

Figure 17: Histogram of net overnight electricity imports during winter coal outages May 2023 to August 2025

Note: Columns represent the frequency that net overnight imports fell within specific ranges, denoted on x-axis labels that display the midpoints of those ranges. For example, the 2 GWh column displays the % of the time that net overnight electricity imports ranged from 0 to 4 GWh, while the right-most column includes all outcomes greater than 8 GWh.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO NEM data.

In our scenario, after Yallourn’s scheduled closure, we assumed that Victoria could import 3 GWh overnight to help address firm capacity gaps.

Victoria’s transmission assets’ maximum import capacity is 2.9 GW. In theory, if other states have enough electricity, Victoria could import up to 44 GWh overnight. This would be more than enough to address our estimated firm capacity gaps.

But Victoria’s net overnight imports during winter outages only exceeded 10 GWh one per cent of the time with a 12 GWh maximum. There is no guarantee Victoria will be able to rely on high overnight imports during cold, dark and still conditions.

Other states could face similar conditions, which could limit electricity generation across south eastern Australia. This would limit other states’ electricity export capacity.

For example, in winter, high-pressure systems often pass over south-eastern Australia. This means New South Wales, South Australia and Tasmania experience reduced wind speeds at the same time as Victoria (Figure 18).

Wind turbines do not generate electricity at speeds below 10 kilometres per hour. In 2024, Victoria faced 35 days from 1 June to 31 August with afternoon wind speeds below 10 kilometres per hour.

Victoria also faced a 27-day stretch of low-wind conditions in May 2024 and an 11-day stretch in April 2024.

Figure 18: Average wind speed in south-eastern Australia at 3 pm between 1 May and 31 July 2024

Note: Chart presents Bureau of Meteorology average wind speeds recorded by weather stations at 3 pm.

Source: VAGO, based on Bureau of Meteorology data for Melbourne, Adelaide, Canberra (proxy for New South Wales wind farm conditions) and Hobart stations.

Figure 18 shows that other states also experienced low-wind conditions between 29 and 30 July 2024, leading to overnight demand for imports from Victoria during this time.

This means that Victoria's ability to import electricity will depend on the overall availability of dispatchable power resources across south-eastern Australia.

However, low wind or solar could also reduce battery storage and output. Low rainfall could reduce hydro electric imports from Tasmania and New South Wales.

AEMO and the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission have also forecast gas shortages across all south-eastern states, which could limit gas-powered electricity generation outside of Victoria (see Figure 19).

Figure 19: Forecast peak day gas demand and supply across Victoria, New South Wales, South Australia and Tasmania

Note: Chart displays AEMO peak day forecasts for high demand days from the Gas Statement of Opportunities. AEMO has noted that seasonal peak gas generation has the potential to coincide with a peak system demand day, especially during winter.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO forecasts from the Gas Forecasting Data Portal and the 2025 Gas Statement of Opportunities.

The upcoming closure of coal and gas-powered electricity plants in New South Wales and South Australia could also mean that these states face tight electricity supply, which would constrain their export capacity.

Despite New South Wales and South Australia bringing on additional battery capacity, several plants will stay open beyond their originally planned retirement dates. This includes the Eraring coal-fired power station in New South Wales and the Torrens Island gas-fired power station units in South Australia, which account for 2.9 GW and 600 MW of firm capacity respectively (see Figure 20).

Overall, the closure of key coal and gas-fired power stations in New South Wales and South Australia will reduce their firm capacity by 4 GW by Yallourn’s scheduled closure date.

Figure 20: Closures of coal and gas-fired power stations in New South Wales and South Australia, over 50 MW

| Power station | Capacity impact | Previous scheduled closure | Current scheduled closure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Eraring (New South Wales) | -2,880 MW | 19 August 2025 | 19 August 2027 |

| Torrens Island B unit 1 (South Australia) | -200 MW | 30 June 2026 | 30 June 2026 |

| Torrens Island B units 2, 3 and 4 (South Australia) | -600 MW | 30 June 2026 | 30 June 2028 |

| Osborne (South Australia) | -180 MW | 31 December 2023 | 31 December 2027 |

| Snuggery (South Australia) | -84 MW | 30 June 2026 | 1 January 2028 |

| Port Lincoln Gas Turbine (South Australia) | -74 MW | 1 July 2024 | 1 January 2028 |

| Total | -4,018 MW |

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO NEM Generation Information and Generating Unit Expected Closure.

Victoria’s CIS allocation

Under the Australian Government–Victoria Renewable Energy Transformation Agreement, Victoria has secured an allocation under the CIS to fund at least:

- 11 TWh of variable renewable electricity generation projects, comprising 3.5 GW of wind and 1.5 GW of utility-scale solar projects

- 1.7 GW or 6.8 GWh of 4-hour equivalent battery storage projects.

Tender guidelines state a preference for projects that can be operational by 31 December 2029.

The department has calculated that Victoria’s CIS allocation accounts for most of the required additional generation to meet Victoria’s 2030 65 per cent renewable energy target.

The department’s advice indicates that the additional generation and storage will maintain electricity reliability in 2030. The department has indicated that this is robust for different scenarios that it has modelled, including gas supply uncertainty and asset outages.

Project delays remain a risk. The commercial operating date for several CIS-supported projects is the end of 2029. However, renewable energy projects in Victoria have faced delays, including because of challenges connecting to the transmission network.

Safeguarding near-term reliable electricity in Victoria

Potential reliability gaps in Victoria's near-term electricity supply are the result of Yallourn closing, higher-than-expected electricity demand and insufficient action by private investors and the department to bring on new supply.

AEMO’s government schemes and actionable developments scenario forecasts that Victoria’s allocation under the CIS and other government and transmission projects will contribute to reliability if projects come online in 2028–29 and 2029–30. If projects face delays, AEMO may need to safeguard reliable electricity in Victoria.

Under the National Electricity Law and National Electricity Rules, AEMO has operational responsibility for electricity reliability across the NEM. In managing forecast reliability gaps, AEMO can:

- request the Australian Energy Regulator to trigger the Retailer Reliability Obligation (RRO) to require energy retailers and large energy consumers to enter contracts to cover their portion of peak demand in advance of periods with a forecast reliability gap

- procure and activate emergency out-of-market electricity reserves through the Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader mechanism when the RRO is insufficient

- direct generators and other NEM participants to take actions to maintain power system security and reliability.

At AEMO’s request, the Australian Energy Regulator triggered an RRO to address shortfalls it forecast for 2027–28 in the 2024 ESOO. However, as AEMO did not forecast these shortfalls in its 2025 ESOO, the RRO may be revoked.

The RRO aims to encourage electricity retailers to support investment in new electricity projects. However, there are constraints that increase the likelihood that retailers will need to purchase from existing generators.

| If there is not enough … | or … | then … |

|---|---|---|

| new dispatchable electricity projects that can be brought online in time | peak demand is higher than standard operating conditions | the RRO might not be enough to increase electricity supply and address electricity shortfalls on its own. |

| transmission capacity | ||

| time to bring on new electricity generation projects |

AEMO and the Australian Energy Market Commission have stated that the current design of the RRO is unlikely to promote the required new investment in electricity generation capacity.

The first trigger under the RRO is the T-3 instrument, which alerts electricity providers to purchase enough wholesale supply to cover a forecast gap. The Australian Energy Regulator issues a T 3 instrument 3 years before the forecast reliability gap period.

Three years is not likely to be a sufficient length of time to signal new investment in many types of capacity. This is because pre-construction activities, such as reaching the final investment decision and finalising contracts, and construction and commissioning, generally take longer than 3 years.

The RRO and Reliability and Emergency Reserve Trader mechanism also place upwards pressure on electricity costs, which retailers or AEMO pass on to consumers. This would be in tension with the Victorian Government's commitment to provide affordable electricity for all Victorians.

Planning for Victoria’s renewable energy transition has not adequately factored in risk and uncertainty

Planning for risk and uncertainty

Department of Treasury and Finance guidelines for high-value and high-risk investments state that agencies should factor risks and uncertainties into problem definition, analysis and modelling.

This helps agencies to understand the nature of a problem, identify options, and estimate costs and benefits. It also provides flexibility to respond to risks and uncertainties.

Demand uncertainty

Energy forecast accuracy is important for developing policies that allow for a smooth transition to renewable energy. The department relies on AEMO's forecasts to understand future demand.

AEMO’s forecasting method meets requirements under the National Electricity Rules and its forecasting safeguards meet the Australian Energy Regulator's Forecasting Best Practice Guidelines.

AEMO assesses and reports the accuracy of its prior year’s forecasts over the most recent year.

AEMO does not report on the long-term accuracy of its forecasts but regularly updates them to improve accuracy.

For example, AEMO’s 2022 Integrated System Plan forecast that electricity demand in Victoria would fall by 1.8 per cent in 2024–25. But demand grew by 3.5 per cent annually. AEMO revised its forecasts in recent years based on electricity demand growing faster than expected and the latest information (see Figure 21).

Figure 21: AEMO’s revised electricity demand forecasts

Note: ISP stands for Integrated System Plan. NEFR stands for the National Electricity Forecasting Report.

Source: VAGO, based on AEMO’s Integrated System Plan and National Electricity Forecasting Report documents.

AEMO's revisions improve the department’s and investors' understanding of long-term electricity demand in Victoria. But significant demand revisions make it difficult for long-term planning to ensure that enough generation and storage capacity is in place while minimising cost.

For example, when the department advised the government on setting renewable energy targets in 2017, it relied on AEMO’s flat electricity demand forecast to 2030. The department then extended this out to 2050. Since then, AEMO has forecast that Victoria’s electricity demand will grow 84.3 per cent by 2050.

Even between 2024 and 2025, rising demand forecasts led AEMO to widen forecast reliability gaps under the committed and anticipated pipeline of energy projects from 2030–31. This is despite more renewable generation and storage capacity being added to the system.

While AEMO expects government renewable schemes and developments to cover reliability gaps, this highlights how there is little margin for error. It is important that planning ensures a buffer for higher-than-expected demand.

AEMO also reported inaccuracy in its forecasts of peak winter demand in Victoria. For example, in June 2025 there was record winter peak electricity demand – around 7 per cent higher than AEMO forecast in its high-demand scenario in the 2024 ESOO.

Planning for Victoria's renewable energy transition

AEMO has reported a forecast risk of a reliability gap coinciding with Yallourn’s exit since 2021.

Current forecasts show that private investment and the department’s planning and market facilitation are on track to address the gap but there is little margin for risk.