Meeting Obligations to Protect Ramsar Wetlands

Overview

Wetlands are a critical part of our natural environment and have environmental, cultural, social and economic value. The Ramsar Convention is an international intergovernmental treaty which provides a framework for the conservation and wise use of designated wetland ecosystems throughout the world. Australia is a signatory and has 65 Ramsar listed sites, 11 of which are in Victoria.

This audit reviewed how effectively Victoria’s Ramsar wetlands are managed and whether Victoria is meeting its national and international obligations. We reviewed the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP) and primary site managers—Melbourne Water and Parks Victoria—who all have a role in conserving and maintaining Victoria's Ramsar sites. We also reviewed selected catchment management authorities.

The audit found there is limited evidence that all Ramsar sites are being effectively managed and protected from decline. There is also evidence of potential change in the ecological character of some sites and changes at other sites cannot be fully determined due to limitations such as a lack of data. Some projects have improved outcomes for Ramsar sites but these are not clearly linked to a Ramsar management plan.

The governance, coordination and oversight of the management of Ramsar sites must improve overall for Victoria to effectively meet its obligations. Monitoring the implementation of management plans also requires improvement. The recommendations are designed to improve gaps in governance, oversight, coordination and monitoring.

Meeting Obligations to Protect Ramsar Wetlands: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER September 2016

PP No 202, Session 2014–16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Meeting Obligations to Protect Ramsar Wetlands.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

14 September 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Andrew Evans—Engagement Leader Rosy Andaloro—Team Leader Samantha Carbone—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Maree Bethel |

Auditor-General's comments

Wetlands are a vital part of the natural environment. They provide refuge, breeding sites and food to animals and plants and are an important part of the landscape. Ramsar wetlands are recognised as having international importance under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat, known as the Ramsar Convention. It is one of the first intergovernmental treaties for the conservation of natural resources. Victoria currently has 11 Ramsar listed sites.

Globally, there has been a loss of wetlands since European settlement, and Victoria is no exception. As well as threats relating to hydrology, invasive plants or animals, activities and recreational use, the impact of climate change is also an emerging threat to wetlands' ecological character. Effectively managing these threats is critical to maintaining the character of Victoria's Ramsar wetlands.

This audit assessed how effectively Victoria's Ramsar wetlands are being managed. In doing so, it looked at the role of the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP) and the primary site managers—Parks Victoria and Melbourne Water—as well as the catchment management authorities (CMA) which also have a key management role.

I found that, while there are a number of effective on-ground management outcomes, these are not clearly linked to management plan actions or risks. Overall, the governance, coordination and oversight of the management of Ramsar sites must improve for Victoria to effectively meet its obligations under the Ramsar Convention.

Monitoring of Ramsar sites also requires improvement. Some short-term output‑focused monitoring takes place, but there is limited ongoing monitoring with a focus on outcomes. As a result, management effectiveness is not systematically monitored, reviewed or evaluated. Failing to maintain the ecological character of these sites risks breaching Australia's international obligations under the Ramsar Convention.

Some of the issues in this audit have been highlighted in previous performance audits in the environment and natural resource management area. These audits have also found complicated and poorly coordinated governance arrangements, a lack of oversight and accountability and poor evaluation, compromised by limitations in data. These systemic issues still need addressing, and all environmental or natural resource management agencies should have close regard to these recurring issues.

Nevertheless, it is encouraging that, as a result of the emerging findings from this audit, DELWP is considering establishing a Victorian Ramsar forum that would bring together staff from DELWP, CMAs, Parks Victoria and Melbourne Water to share information, communicate issues and national updates, and to progress issues at a site and statewide level. This should also allow better understanding of roles and responsibilities, and the development of a shared understanding of priority values and threats at each site, as well as helping to track progress in implementing site management plans.

I would like to thank the staff from DELWP, Parks Victoria, Melbourne Water and CMAs who engaged with my office constructively and positively during this audit.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

September 2016

Audit Summary

Wetlands are a critical part of our natural environment and have environmental, cultural, social and economic value. They are important for sustaining biodiversity regionally, nationally and internationally and provide a habitat for threatened species. Threats to the ecological character of a wetland including changes in water level, flow and quality, invasive species, climate change and recreational use. These threats make conserving these sites challenging.

The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat, or the Ramsar Convention, is an international intergovernmental treaty that provides a framework for the conservation and wise use of designated wetland ecosystems throughout the world. Australia is a signatory to the agreement and has 65 Ramsar listed sites, 11 of which are in Victoria.

In designating a Ramsar site, countries agree to set up and oversee a management framework aimed at conserving and maintaining the wetland and its ecological character.

The Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP) and primary site managers— Parks Victoria and Melbourne Water—all have a role in conserving and maintaining Victoria's Ramsar sites. Site managers must monitor and detect changes and threats to a site's ecological character, implement management practices to address these, and report any actual or likely changes in ecological character to DELWP. As waterway managers, catchment management authorities (CMA) also have a role in managing Ramsar sites—most Ramsar site management plans are incorporated into the regional waterway strategies (RWS) developed by CMAs.

Our audit looked at how effectively Ramsar wetlands are being managed, including interagency collaboration, and whether Victoria is meeting its national and international obligations. We assessed:

- the adequacy of Ramsar wetlands management plans and their implementation

- whether monitoring, evaluation and reporting occurs and is used to understand the impacts of management activities, inform management practices and meet reporting obligations.

As part of this assessment, we visited three Ramsar sites to determine whether management plans were being implemented as intended. The audit did not assess the effectiveness of Commonwealth or non-government agencies.

Conclusions

There is limited evidence that all Ramsar sites are being effectively managed and protected from decline. There is also evidence of potential change in the ecological character of some sites, while changes at other sites cannot be fully determined due to limitations such as a lack of data.

Some of Victoria's Ramsar sites are better managed than others. The one managed by Melbourne Water is a good example—this has a standalone management plan with clear roles and responsibilities for implementation and monitoring. Roles and responsibilities are less clear for the sites where Parks Victoria is the primary site manager. Some projects have improved outcomes for Ramsar sites, but these activities are not clearly linked to Ramsar management plan actions or risks.

Overall, the governance, coordination and oversight of the management of Ramsar sites must improve for Victoria to effectively meet its obligations. Without this improvement, site managers will continue to be guided by their own priorities, rather than responding to key threats to Ramsar sites' ecological character.

Monitoring the implementation of management plans requires improvement. Some short-term output-focused monitoring takes place, but there is limited ongoing monitoring of plan implementation or whether actions are achieving the intended outcomes. DELWP reviews Ramsar sites every three years to detect changes in critical site elements and to inform national condition reporting. This information is provided to site managers, however, it is not intended to inform short-term site management. Management effectiveness is not systematically monitored, reviewed or evaluated.

Encouragingly, DELWP has committed to improving its outcome-based monitoring of management plans through the development of a statewide approach to monitoring Ramsar sites.

Findings

Ramsar management responsibilities in Victoria

The state, through DELWP and site managers, has certain responsibilities, however, the Commonwealth Government has overall responsibility for administering the convention nationally.

The Ramsar Convention requires that the following key documents be developed to guide the maintenance and management of the ecological character of the wetland and to set a baseline for measuring change:

- Ramsar information sheet (RIS)

- ecological character description (ECD)

- site management plan.

Ramsar information sheet

The RIS provides essential data on each designated wetland. Signatories to the Ramsar Convention commit to preparing and updating an RIS every six years or when the character of a site changes. DELWP does not comply with this requirement, as no site has a current RIS. Ten sites were last updated in 1999, and the Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands site RIS was updated in 2001. DELWP advised that updates were drafted in 2005 and again in 2016 but have not yet been finalised by the Commonwealth Government.

Ecological character description

An ECD describes the baseline condition at each site at the time of listing and provides the foundation for a management plan. Of Victoria's 11 Ramsar sites, 10 have a published ECD. The Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula ECD has been in draft since 2011, as it has not been published by the Commonwealth Government.

Final ECDs for nine wetlands formally listed in 1982 and one in 2001 were only developed between 2010 and 2012, following the development of national guidelines. The amount of time between listing and establishing the ECDs means there is limited information on the historical baseline condition of these sites.

Limits of acceptable change

ECDs must specify limits of acceptable change (LAC) for all identified critical ecological elements of a site. The Ramsar Secretariat must be notified if there has been a change in ecological character. If an LAC is exceeded, this may indicate an adverse change in the wetland's ecological character.

Victoria's ECDs identify 88 critical elements for which LACs must be determined. Currently, 118 of these have been determined. Only five of the 11 Ramsar sites have LACs for all their identified critical ecological elements. This is mainly due to knowledge gaps and poor baseline data.

Site management plans

Management plans should outline the management, monitoring and evaluation activities required to maintain the ecological character of the Ramsar site and to address emerging risks.

There are no national guidelines for the development of Ramsar site management plans. Seven of Victoria's sites have a current management plan embedded within an RWS, three have standalone plans—one of which is in draft—and one has no current management plan. None of these plans met all the Australian requirements to be considered a comprehensive management framework.

Governance, oversight, and roles and responsibilities

Governance

Due to the ecological complexity of Ramsar sites and the number of stakeholders involved, sound governance arrangements are required to manage them effectively. There is not a robust governance framework or procedures in place to help implement plans in a risk-based, prioritised manner. As a result, there is little evidence that plans have been effectively implemented.

While most of the management plans in place assign lead agencies to activities, there is limited accountability for implementation and monitoring their effectiveness. Without adequate governance, site managers mainly use their own planning priorities rather than being accountable for delivering management plan actions.

A number of management plans, including Gippsland Lakes, Kerang Lakes and Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands Ramsar sites, specify clear governance arrangements for their implementation. These should be used as examples of better practice.

Oversight

Limited oversight means management plans are not always effectively implemented. DELWP, which is responsible for promoting the wise use and conservation of Ramsar wetlands and reporting on their ecological status, has limited oversight of how plans for all 11 sites are implemented and evaluated.

Parks Victoria also poorly oversees the implementation of management plans for the 10 sites it manages. While it carries out many habitat-management activities that often improve environmental outcomes, this work is mainly implemented through projects and specifically funded initiatives. It is opportunistic and reactive, based on available funding. These activities are generally not guided by the current Ramsar management plan, and this can result in significant ecological risks not being addressed in a timely way.

Roles and responsibilities

Site managers and CMAs are generally responsible for implementing management plans, but roles and responsibilities for specific actions are not always clear or documented. This means that, while lead agencies are identified, actions are not always implemented. CMAs led the development of management plans for most Parks Victoria sites, but are they not fully responsible for implementing all actions. This results in limited accountability. This is not the case for Melbourne Water, which is the site manager for the Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands site and responsible for developing and implementing its management plan.

DELWP acknowledges that improvements should be made in governance and in better integration between agencies that have a role in Ramsar site management. It is planning to address this.

Funding for delivery

Inadequate ongoing resourcing arrangements are a major hurdle to the effective management of Ramsar sites in Victoria. Not all management plan actions are funded, so responsible agencies rely on grants, and meeting sometimes competing Commonwealth and state priorities is challenging.

Funding is provided to DELWP through the State Budget process, and DELWP allocates a large portion of these funds to CMAs to deliver the actions in their RWSs. CMAs may allocate funding to other parties, including Parks Victoria, to complete this work. In addition, there are other grant and program funding opportunities available.

Parks Victoria should be able to assess its 10 Ramsar sites and know what resources it requires to manage them, but it currently cannot do so. It is planning to collect this information as it introduces its new planning process.

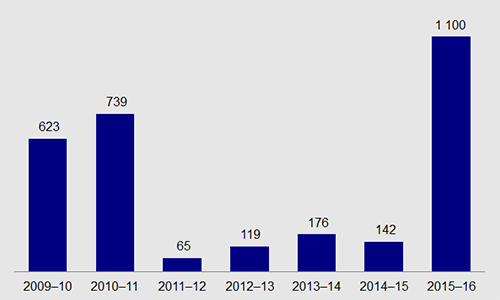

The Commonwealth Government had a Ramsar program from 2008−09 to 2011−12 that funded the development and review of ECDs and some RIS updates. It also funded the first Ramsar rolling review in 2011. It no longer provides funding for this, and DELWP funded the second round.

Monitoring and reporting against management plans

Monitoring and reporting of Ramsar site management plans is focused on implementation of actions rather than their effectiveness. That is, monitoring focuses on short-term and output-based actions—for example, hectares of fencing installed—rather than long-term, outcome-focused actions—for example, water quality changes.

Parks Victoria

Parks Victoria does not monitor and report on the implementation of management plans for the 10 sites it manages and does not evaluate its actions. Instead, it monitors actions against its own regional plans, which are not clearly linked to Ramsar management plans.

In 2013, Parks Victoria reviewed the status of its Ramsar management activities using the Ramsar management plans it prepared in 2002–03. This review identified outstanding actions but did not make further recommendations, and it is not clear how it has helped planning. The most common reason identified for not carrying out actions was a lack of funding, and there was also confusion over responsibilities. This reinforces the need to improve governance and accountability for implementing plans.

Melbourne Water

Melbourne Water monitors a number of environmental outcome indicators at its two Ramsar sites. It regularly monitors the ecological indicators outlined in the management plan for the Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands site. In the absence of a specific plan for the Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula site, Melbourne Water uses the Western Treatment Plant plan to monitor indicators such as the number of shorebirds, ibis and growling grass frogs every year.

Catchment management authorities

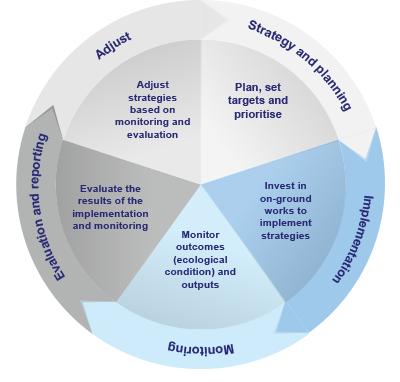

RWSs are supported by an overall monitoring, evaluation, reporting and improvement framework based on an eight-year adaptive management cycle set out in the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy. However, not all CMAs have developed plans to apply this framework. Two regional plans have been completed, with the remaining eight plans to be completed by the end of 2016. These will link activities and outputs to long‑term resource condition outcomes and regional goals.

Monitoring for adaptive management

Monitoring is important to support an adaptive management approach—the ongoing adjustment of strategies based on monitoring and evaluation. There is limited evidence of an overall adaptive management approach being applied to each of the Ramsar sites. However, we found some examples of adaptive management to address specific threats, which had resulted in improved environmental outcomes.

Reporting on site management plans

Reporting on the implementation of Ramsar site management plans or on the outcomes of monitoring occurs infrequently. As a result, reporting by site managers and CMAs is inadequate. DELWP reports the outcomes of its monitoring as part of the Ramsar 'Rolling Review' process, but this is not linked to management plans or used to inform management practices. Melbourne Water advised that it reports every seven years—when the management plans are renewed.

CMAs do not directly report on Ramsar site management, as their annual reports to DELWP are framed against agreed outputs contained in service level agreements. These outputs are not directly linked to Ramsar sites. Reporting to DELWP on the progress of RWS actions, where Ramsar management plans are embedded, is scheduled to occur in 2018 and 2022.

State-level monitoring by the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning

DELWP reviews the condition of Ramsar sites and reports to the Commonwealth Government on their status through:

- the national Ramsar Rolling Review

- a state project to improve the monitoring of Ramsar sites.

Ramsar Rolling Review

The first Ramsar Rolling Review was undertaken in 2011 and aimed to identify changes in ecological character. This was a nationally funded program coordinated by the Commonwealth Government. The Rolling Review takes place every three years to assess the status of the ecological character of each site by comparing the condition of the critical elements against the LAC. The status of the key threats is assessed at the same time. The review is not publicly available but, if there are changes to the site, these are made public.

A second state-funded review took place in 2014–15 and 2015–16 which found that some LACs were not met and, in several instances, LACs could not be assessed due to a lack of data. The results of this second round are still in draft and have not yet been endorsed by the Commonwealth Government.

Project to improve Ramsar site monitoring

In October 2015, DELWP began a project aimed at improving monitoring at Ramsar sites, which included addressing data gaps and deficiencies and improving the link between monitoring and Ramsar site management planning. The project is scheduled to be completed by 30 November 2016.

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning reporting to the Commonwealth Government

DELWP is required to advise the Commonwealth Government as soon as it becomes aware of a potential or actual change in ecological character at a Ramsar site. DELWP also reports on changes to the ecological character of Ramsar sites to the Commonwealth Government through:

- six-yearly updates to the RIS, in which DELWP reports whether there have been any changes to the area or to the ecological character of a site

- three-yearly reports to inform national reporting on changes to the ecological character of wetlands.

DELWP has not reported a change in the ecological character of Ramsar wetlands since the sites were listed. However, the draft results of the 2014–15 Ramsar Rolling Review indicate a potential change in ecological character at some Victorian sites. DELWP has advised that this will be reported to the Commonwealth Government.

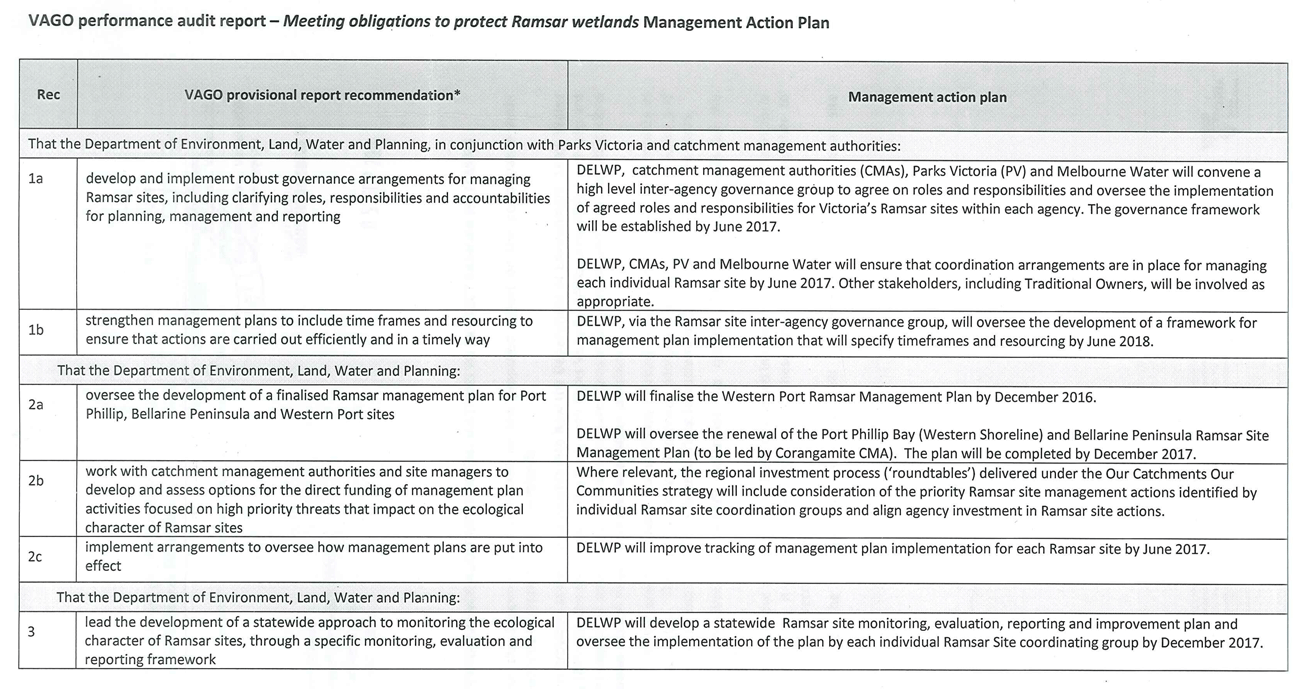

Recommendations

- That the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, in conjunction with Parks Victoria and catchment management authorities:

- develop and implement robust governance arrangements for managing Ramsar sites, including clarifying roles, responsibilities and accountabilities for planning, management and reporting

- strengthen management plans to include time frames and resourcing to ensure that actions are carried out effectively and in a timely way.

- That the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning:

- oversee the development of a finalised Ramsar management plan for the Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula and Western Port sites

- work with catchment management authorities and site managers to develop and assess options for the direct funding of management plan activities focused on high-priority threats that impact on the ecological character of Ramsar sites

- implement arrangements to oversee how management plans are put into effect.

- That the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning lead the development of a statewide approach to monitoring the ecological character of Ramsar sites, through a specific monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, Parks Victoria, Melbourne Water, Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, North Central Catchment Management Authority, Glenelg Hopkins Catchment Management Authority, East Gippsland Catchment Management Authority and West Gippsland Catchment Management Authority throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier & Cabinet.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix C.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Wetlands

Wetlands are areas that hold still or slow-moving water permanently, periodically or intermittently. They may be formed by natural processes or made by humans. Wetlands are diverse and include swamps, billabongs, lakes, mangroves, coral reefs, peatlands, mudflats, estuaries and seagrass areas.

Wetland functions and values

Wetlands are an important part of the natural environment and are culturally, socially, environmentally and economically valuable. They protect shores from wave action, reduce the impacts of floods, absorb pollutants, improve water quality and provide a habitat for diverse animals and plants. Often, they are also areas of natural beauty. Indigenous people are the traditional owners of many wetlands, which are important to them.

Wetlands provide economic benefits by supporting commercial and recreational activities, such as fishing, tourism, boating and game hunting.

Threats to wetlands

There are a range of threats to wetlands including:

- changed water regimes—alterations to the frequency, duration or season of inundation including river regulation, water extraction, drainage or changes to the catchment flow that interrupt the natural ebb and flow of the wetland system

- water quality—such as changes in salinity and increases in nutrient levels from nearby agriculture, which can trigger an algal bloom

- agricultural use—including draining, cropping and grazing of wetlands

- invasive species—invasive animals and plants competing with and degrading the environment of native animals and plants

- climate change—impacts include changes to water regimes from increased temperatures and decreased rainfall, and salinisation of coastal systems due to sea level rise

- recreational use—camping, hiking, fishing, boating, duck hunting and other recreational activities can disturb the soil, habitat and native flora and fauna.

Algal bloom at Macleod Morass, Gippsland Lakes, April 2016.

These threats make conserving wetlands challenging. A consequence of the declining health of wetlands is the decline or loss of many bird and fish species. In 2015, the University of New South Wales annual Eastern Australian Waterbirds Survey found a continuing long-term decline in water bird numbers, wetland area, breeding numbers and breeding species richness throughout Australia.

1.1.2 Victoria's wetlands

The Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP) maintains the Victorian wetland inventory, which was last updated in August 2014. The inventory contains data on 35 499 natural and artificial wetlands, covering 1 960 990 hectares. The number of wetlands occurring on public and private land is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Number of wetlands on public and private land according to wetland origin

Origin |

Completely private |

Completely public |

Both private and public |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Natural |

17 207 |

5 457 |

2 960 |

25 624 |

Artificial |

8 945 |

445 |

344 |

9 734 |

Unknown |

43 |

82 |

16 |

141 |

Total |

26 195 |

5 984 |

3 320 |

35 499 |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DELWP.

As shown in Figure 1B, natural wetlands occupy around 94 per cent of Victoria's wetland area while artificial wetlands make up less than 6 per cent.

Figure 1B

Natural and artificial wetlands in Victoria

Origin |

Area (hectares) |

Per cent of total |

|---|---|---|

Natural |

1 843 896 |

94% |

Artificial |

107 914 |

5.5% |

Unknown |

9 180 |

0.5% |

Total |

1 960 990 |

100% |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DELWP.

It is estimated that more than a quarter of Victoria's wetlands have been lost since European settlement.

1.2 Wetlands of international importance

1.2.1 Ramsar Convention

The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat, or the Ramsar Convention, is an international intergovernmental treaty. The convention provides a framework for the conservation and wise use of wetlands throughout the world.

Under the Ramsar Convention, sites containing representative, rare, unique wetlands important for conserving biological diversity may be designated as wetlands of international importance and placed on the Ramsar List of Wetlands of International Importance. Listed wetlands are known as Ramsar wetlands or Ramsar sites.

For a wetland to be included on the list, it must satisfy one or more of nine criteria. The current Ramsar criteria are listed in Appendix A.

In designating a wetland as a Ramsar site, countries agree to set up and oversee a management framework aimed at conserving the wetland and ensuring its wise use by maintaining the wetland's ecological character. These terms are defined in Figure 1C.

Figure 1C

Ramsar Convention definitions

|

Wise use—the maintenance of the ecological character of wetlands, achieved through the implementation of ecosystem approaches, within the context of sustainable development. Ecological character—the combination of ecosystem components, processes and benefits/services that characterise the wetland at a given point in time. |

Source: VAGO based on Ramsar Convention definitions.

Changes to the wetland's ecological character outside natural variations could mean that impacts on the site are unsustainable and could degrade natural processes and the wetland's ecology, biology and hydrology.

As of May 2016, there were 169 signatories to the Ramsar Convention and 2 222 Ramsar sites. Australia became a contracting party in 1974 and currently has 65 Ramsar sites, with 11 in Victoria, as shown in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

Location of Victoria's Ramsar sites

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DELWP.

The Commonwealth Environmental Water Office at the Department of Environment and Energy is responsible for Australia's Ramsar commitment. Some of its key responsibilities include:

- designating Australian sites to be added to the List of Wetlands of International Importance

- leading the development of national guidance on and approaches to implementing the Ramsar Convention in Australia

- working with state and territory governments to promote the conservation of Ramsar sites and wise use of all wetlands and to review the condition of Ramsar sites

- representing Australia at the triennial Conference of Parties and collating the national report for these meetings

- coordinating other reporting for the Ramsar Convention, including updates of Ramsar information sheets (RIS), reporting any changes to the ecological character of Australia's listed wetlands and responding to inquiries from the secretariat about reports from third parties

- providing advice on the Ramsar Convention and any agreed assistance to wetland managers.

Key documents for Ramsar management

Three key documents are prepared and maintained for each Victorian Ramsar site—the RIS, ecological character description (ECD) and the management plan.

The RIS is a requirement under the Ramsar Convention. It is a standard data sheet for each site that includes information on the criteria met, the wetland type, the wetland values and the conservation measures taken or planned. An up-to-date map and boundary description accompanies the RIS. The Ramsar Secretariat uses the RIS to populate the Ramsar information database.

The ECD is a national requirement. It provides the baseline description of the wetland at a certain time and can be used to assess ecological changes at a site. An ECD should be prepared for all Ramsar sites and should identify:

- the critical elements—components, processes, benefits and services—that form the ecological character of the site

- limits of acceptable change for each critical component of the ecological character of the site

- threats to the site

- knowledge gaps

- monitoring needs

- any change in ecological character.

The management plan is a requirement of the Ramsar Convention. It promotes the wise use and conservation of a wetland and should detail:

- the characteristics that make the wetland internationally important

- strategies to maintain the wetland's ecological character and reduce risks to the wetland

- provisions for continuing monitoring and reporting.

The management plan should be reviewed every seven years.

Site management

The site manager is the landowner or legal manager of a Ramsar site. The site manager may be the government, a community entity, traditional owners, a company or organisation, or a private owner. Site managers are encouraged to:

- manage the Ramsar site to maintain its ecological character

- have procedures in place to monitor and detect changes and threats to the site's ecological character

- where possible, create and implement strategies to reverse changes in ecological character

- report any actual or likely changes in ecological character to DELWP

- carry out site updates for the RIS and report as required

- seek approval under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 before doing anything that will, or is likely to, have a significant impact on the ecological character of the site.

Figure 1E shows the size of Victoria's Ramsar sites and their primary site managers.

Figure 1E

Victoria's Ramsar sites

Ramsar site |

Area (hectares) |

Primary site manager |

|---|---|---|

Barmah Forest |

29 305 |

Parks Victoria |

Corner Inlet |

67 193 |

Parks Victoria |

Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands |

261 |

Melbourne Water |

Gippsland Lakes |

61 151 |

Parks Victoria |

Gunbower Forest |

20 218 |

Parks Victoria DELWP |

Hattah–Kulkyne Lakes |

977 |

Parks Victoria |

Kerang Wetlands |

9 793 |

Parks Victoria Goulburn-Murray Water |

Lake Albacutya |

5 659 |

Parks Victoria |

Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula |

22 646 |

Parks Victoria Melbourne Water |

Western District Lakes |

32 671 |

Parks Victoria |

Western Port |

59 955 |

Parks Victoria DELWP |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DELWP.

There are also a number of other organisations including councils, traditional owners and other authorities with some involvement in site management.

1.3 Relevant legislation and policy

Key Commonwealth legislation relevant to protecting and managing Ramsar sites is described in Figure 1F.

Figure 1F

Key Commonwealth legislation relevant to Ramsar sites

Legislation |

|

|---|---|

Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 |

Provides the legal framework for the protection and management of nine matters of national environmental significance, including Ramsar. Other relevant matters include listed migratory species and listed threatened species and ecological communities. |

Water Act 2007 |

Establishes the Murray-Darling Basin Authority's functions and powers, including enforcement powers, needed to ensure that basin water resources including wetlands are managed in an integrated and sustainable way. Also establishes a Commonwealth Environmental Water Holder to protect and restore the environmental assets of the Murray-Darling Basin and other areas where the Commonwealth owns water. |

Source: VAGO.

State legislation does not specifically cover Ramsar sites. However, legislation that is relevant to wetland management includes:

- Catchment and Land Protection Act 1994

- Environment Protection Act 1970

- Environment Effects Act 1978

- Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988

- Water Act 1989.

Victorian Waterway Management Strategy 2013

The former Department of Environment and Primary Industries (now DELWP) prepared Improving our Waterways: Victorian Waterway Management Strategy.

The strategy sets up an integrated waterway management framework that provides:

- clear policy directions for waterway management

- specific actions to make the management of waterways more effective and efficient

- aspirational targets that summarise key regional management activities over eight years, with the aim of maintaining or improving the condition of waterways

- for adaptive management (see Part 3.3.1).

The strategy integrates wetland management into an overall waterway management framework and has policies and actions that relate to Ramsar sites (see Appendix B). It also streamlines the processes for approving, investing in and reporting on outcomes for Ramsar sites and introduces a role for catchment management authorities (CMA) in Ramsar management through their regional waterway strategies (RWS).

Regional waterway strategies

The RWS is a single planning document for river, estuary and wetland management in each region. It supports the Victorian Waterway Management Strategy.

RWS is developed by waterway managers in partnership with other regional agencies, authorities and boards, plus traditional owners, regional communities and other key stakeholders. They outline regional goals for waterway management and set out strategic regional work programs for priority waterways.

Ramsar management plans are incorporated into the RWSs for seven sites—see Figure 2A. CMAs lead the development of RWSs.

1.4 Agencies

Several bodies have a role in planning for or managing Victoria's Ramsar wetlands.

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning

DELWP is the main body responsible for legislation and policy for managing Victoria's wetlands. It aims to improve the environmental condition of waterways to ensure that Victoria has safe and sustainable water resources to meet future needs.

To comply with Ramsar and Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 requirements, DELWP must:

- adhere to national Ramsar guidelines, including management principles, management plans and the requirement to describe and report changes or potential changes to the ecological character of sites to the Commonwealth Government

- coordinate and maintain documents for Ramsar sites—including RISs, ECDs, management plans, site descriptions and maps

- together with the Commonwealth Government, lead the nomination of potential Ramsar sites.

Parks Victoria

Parks Victoria manages national, state and metropolitan parks and marine national parks, as well as having a role in managing Melbourne's bays, waterways and other significant cultural assets. It is the primary site manager for 10 of the 11 Victorian Ramsar sites. Four of these sites also have another primary site manager, because they have multiple tenures and are on different parcels of land.

Melbourne Water

Melbourne Water is a statutory authority that manages water catchments, treats and supplies drinking and recycled water, removes and treats most of Melbourne's sewage and manages waterways and major drainage systems in the Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Western Port region. It is the main site manager for the Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands site and manages the Western Treatment Plant and part of the Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula site.

Catchment management authorities

CMAs are statutory authorities set up to maximise community involvement in decision‑making and to deliver programs to effectively manage catchments. They have a lead role in developing and delivering regional programs for waterway management.

CMAs' functions include:

- developing RWSs and associated action plans

- developing and implementing work programs

- authorising works on waterways and acting as a referral body for planning applications, for licences to take and use water and construct dams, for water use and for other waterway health issues

- identifying regional priorities for environmental water management and facilitating the delivery of environmental water

- providing input to water allocation processes

- developing and coordinating regional flood plain management plans

- managing regional drainage in specified areas

- responding to natural disasters and incidents affecting waterways such as bushfires, floods and algal blooms

- undertaking community participation and awareness programs.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

This audit assessed how effectively Victoria's Ramsar wetlands are managed, including how effectively agencies are working with each other, and whether Victoria is meeting its national and international obligations.

To address these objectives, we assessed whether:

- comprehensive, reliable and current information and effective consultation with stakeholders informs the management of Ramsar wetlands

- comprehensive management plans are in place

- management plans are implemented as intended

- monitoring, evaluation and reporting occur and whether these are used to understand the impact of management activities, inform management practices and meet reporting obligations.

We audited DELWP, Parks Victoria, Melbourne Water and relevant CMAs.

We did not assess the effectiveness of Commonwealth or non-government agencies.

1.6 Audit method and cost

To test the effectiveness of Ramsar wetland management in Victoria, we reviewed relevant legislation, policies and documents, such as site management plans and ecological character descriptions. We interviewed and consulted agency staff and stakeholders.

We tested management activities at three Ramsar sites—Gippsland Lakes, Kerang Lakes and Western District Lakes

We chose these sites because they have a range of different management arrangements, site values, threats and land tenure.

The audit was carried out under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994, in keeping with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $330 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 looks at how Ramsar management plans are planned and implemented

- Part 3 looks at monitoring, evaluation and reporting on the management of wetlands using examples from selected sites.

2 Victoria's Ramsar site management framework

At a glance

Background

Sound planning and management is required to conserve the ecological character of Ramsar sites and detect any unacceptable change.

Conclusion

There is limited evidence that all Ramsar sites are managed effectively and protected from further decline. The governance, coordination and oversight of the management of Ramsar sites require significant improvement for Victoria to effectively meet its obligations under the Ramsar Convention. Without this improvement, site managers will continue to work to their own priorities rather than responding to significant threats and working to prevent ecological decline.

Findings

- The management framework for most Ramsar sites lacks accountability, as governance and oversight processes are poor, and roles and responsibilities for the implementation and monitoring of management plans are not clear.

- Current documents for sites required under the Ramsar Convention are either not up to date or are not complete.

- There are some examples of good planning and management by Melbourne Water, demonstrating effective governance and clear accountabilities.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning, in conjunction with Parks Victoria and catchment management authorities, improve implementation of management plans by improving governance arrangements, and outlining clear roles and responsibilities, time frames and resourcing.

- That the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning oversee the development of finalised management plans for the Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula and Western Port Ramsar sites.

2.1 Introduction

The Convention on Wetlands of International Importance Especially as Waterfowl Habitat, or the Ramsar Convention, obliges signatories to prepare management plans that promote the sustainable use of wetlands. Multiple organisations have a role in looking after Ramsar sites in Victoria, so effective governance arrangements that clearly assign specific roles and responsibilities are required. Such arrangements reduce the risk of overlap and service gaps, and improve accountability by clearly attributing responsibility for the implementation of management plan actions.

Robust management plans are the foundation for the wise use and conservation of wetlands. They should be based on a comprehensive understanding of the ecological character of a site and identify actions to conserve the site's ecological character by addressing emerging threats. Good management also requires continuous monitoring, evaluation and reporting to assess the effectiveness of management actions.

2.2 Conclusion

There is limited evidence that all Ramsar sites are being effectively managed and protected from decline. There is also evidence of potential change in the ecological character of some sites, while changes at other sites cannot be fully determined due to limitations such as a lack of data.

Some sites are better managed than others. The site managed by Melbourne Water is a good example—it has a standalone management plan with clear roles and responsibilities for implementation and monitoring. Roles and responsibilities are less clear for the 10 sites managed by Parks Victoria. Some projects have improved outcomes for Ramsar sites, but these activities are not clearly linked to management plan actions or risks.

Overall, the governance, coordination and oversight of the implementation of management plans for Ramsar sites must improve for Victoria to effectively meet its obligations. Without this improvement, site managers will continue to be guided by their own priorities rather than responding to key threats to Ramsar sites.

2.3 Ramsar management responsibilities in Victoria

The state of Victoria—through the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP) and site managers, including Parks Victoria and Melbourne Water—has certain responsibilities which include preparing Ramsar information sheets (RIS), an ecological character description (ECD) and a management plan for each Ramsar site.

2.3.1 Ramsar information sheet

Ramsar Convention contracting parties commit to preparing and updating an RIS every six years or when the character of a Ramsar site changes. Victoria does not comply with this requirement, as no site has a current RIS. RISs for 10 sites were dated 1999, and the RIS for the Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands site was dated 2001. DELWP advised that updates were drafted in 2005 but were not finalised by the Commonwealth Government. DELWP has updated the RIS boundary descriptions and maps to comply with national guidelines in the first half of 2016 and has provided these to the Commonwealth Government for review and endorsement.

2.3.2 Ecological character description

An ECD describes the baseline condition of a wetland at the time of its listing as a Ramsar site. An ECD provides the foundation for a management plan and is important for monitoring and assessing changes to a wetland's ecological character. In line with a national framework, an ECD must include:

- site details

- a description of the components, processes, benefits and services of the site

- limits of acceptable change (LAC)—the acceptable variation limits of an ecological characteristic or process at the time of listing

- potential threats to the site

- knowledge gaps and key monitoring needs.

Of the 11 Ramsar sites, 10 have a published ECD. The Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula ECD has been in draft since 2011 as the Commonwealth Government has not yet endorsed it.

The ECDs for Victoria's Ramsar sites identify 88 critical elements for which LACs must be determined. Currently, 118 LACs have been determined. The national framework for describing ecological character states that there may not be enough information to set LACs for some critical components and processes. In these instances, the lack of information should be described as a knowledge gap. All of the completed ECDs identify knowledge gaps.

LACs are important for determining whether a wetland's ecology has changed. They are used to measure changes in hydrology, vegetation, native fish, waterbirds or threatened species. The Ramsar Secretariat must be notified if there has been a change in ecological character. If a LAC for a site is exceeded, it may indicate an adverse change in the wetland's ecological character.

Only five of the 11 Ramsar sites assessed have LACs for all their critical ecological elements. This is mainly due to knowledge gaps and poor baseline data at the time of listing. LACs should be determined based on the condition of the wetland at the time the site was listed, to provide a baseline against which to compare changes at the site. However, as ECDs were not developed until 2010–12, LACs could not be determined at the time of listing, which was 1982 for all sites except the Edithvale−Seaford Wetlands site, which was listed in 2001.

The Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands site has no established LACs because its ECD predates the government-prepared guidance on the critical elements that characterise a wetland, which act as the base for determining LACs. Without LACs, it is difficult to determine whether a site is degrading because changes in ecological character cannot be monitored effectively.

The case study in Figure 2A outlines a notification of change in ecological character by a third party—a member of the public, non-government organisation or community group—directly to the international Ramsar Secretariat. This demonstrates the importance of baseline data and establishing LACs in a timely way.

Figure 2A

Case study: Third-party notification

|

In March 2009, concerns were raised by a third party about an increase in salinity at Lake Wellington in the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar site. The Ramsar Secretariat notified the Commonwealth Government which then informed DELWP. The Commonwealth Government led an assessment of ecological character change and, in February 2012, concluded that: Based on the best available scientific evidence, the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site had not undergone human-induced adverse alteration in the critical components, processes and benefits/services since the time it was listed in 1982. At this time, an LAC for salinity at Lake Wellington was not set. The 2015 Gippsland Lakes Management Plan indicates an increase in salinity at Lake Wellington from 1986 to 2015. In reviewing the ECD for the site, DELWP developed a draft addendum to include an LAC for salinity at Lake Wellington. In 2015–16, after a further third-party notification, the site was reassessed against this LAC. The findings will be included in the ECD addendum when this is finalised in consultation with the Commonwealth Government. |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DELWP.

DELWP is aware of several problems with ECDs, including:

- the availability of new information that may update LACs to more accurately reflect the condition of sites at the time of listing

- the absence of LACs for some critical elements

- the absence of monitoring data for some LACs and threat indicators

- methods, time frames and accountabilities for monitoring LACs and threat indicators not being generally documented in management plans or other Ramsar site documents.

To address these issues, DELWP began a project to revise and update ECDs in October 2015, including setting and reviewing LACs. The project is further discussed in Section 3.4.

Lake Albacutya, photographed in 2014, is threatened by the impact of climate change and has been dry for the last 20 years. It has contained water for only four periods in the last century: 1909–29, 1956–68, 1974–83 and 1992–94.

2.3.3 Management plans

Management plans should outline the management, monitoring and evaluation activities required to maintain the ecological character of Ramsar sites and should address current and emerging risks. ECDs should guide their development.

National regulations set out general principles for the development of Ramsar site management plans. These should contain a description of the site's ecological character, actions necessary to maintain its ecological character, and monitoring and reporting provisions. The principles recommend that management plans be reviewed every seven years.

DELWP has also developed guidance for catchment management authorities (CMA) outlining when and how Ramsar site management should be incorporated into regional waterway strategies (RWS).

Of Victoria's 11 Ramsar sites, seven have a current management plan embedded within an RWS, three have standalone plans—one of which is in draft—and one site (Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula) does not have a current management plan. DELWP advised that work to renew this plan has commenced. It has funded Corangamite CMA to lead the plan development, which is expected to be completed by December 2017.

The location and status of Ramsar management plans is shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Location of Ramsar site management plans

|

Ramsar site |

Location of management plan |

|---|---|

|

Barmah Forest |

Goulburn Broken Regional Waterway Strategy 2014–22 |

|

Corner Inlet |

West Gippsland Waterway Strategy 2014–22 |

|

Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands |

Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands Management Plan 2009 |

|

Gippsland Lakes |

Gippsland Lakes Ramsar Site Management Plan 2015 |

|

Gunbower Forest |

North Central Waterway Strategy 2014–22 |

|

Hattah–Kulkyne Lakes |

Mallee Waterway Strategy 2014–22 |

|

Kerang Wetlands |

North Central Waterway Strategy 2014–22 |

|

Lake Albacutya |

Wimmera Waterway Strategy 2014–22 |

|

Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula |

Out of date |

|

Western District Lakes |

Corangamite Waterway Strategy 2014–22 |

|

Western Port |

In draft |

Source: VAGO based on information from DELWP.

Parks Victoria and the former Department of Sustainability & Environment prepared Ramsar management plans in 2002–04 before they were embedded in RWSs. Despite being out of date, these plans remain on the Parks Victoria website and, in 2013, Parks Victoria used these plans to review the status of management actions—see Section 3.3. This audit did not assess the development of these plans.

Assessment of Ramsar management plans

Our assessment of current Ramsar management plans, based on the key Australian Ramsar management principles, is shown in Figure 2C. No one plan met all the requirements to be considered a comprehensive management framework for a Ramsar site.

Photographed in 2016, Lake Wellington's dying vegetation—phragmites reed beds— is thought to be caused by increased salinity in the lake.

Figure 2C Ramsar management planning requirements

|

Criteria |

Met |

Not met |

Partly met |

|---|---|---|---|

|

A management plan exists for the site. |

9 |

1 |

1(a) |

|

The management plan describes the ecological character of the site. |

9 |

1 |

1 |

|

The management plan states the Ramsar criteria met. |

10 |

1 |

– |

|

The management plan has management actions for the conservation and maintenance of the ecological character of the site. |

5 |

1 |

5 |

|

The management plan promotes actions for the wise use of the wetland. |

7 |

1 |

3 |

|

The plan has management actions to address threats that impact the wetland's ecological character. |

2 |

1 |

8 |

|

The development of the management plan utilised a public consultation. |

9 |

2 |

– |

|

The management plan involved people with an interest in the wetland and provides for continuing community and technical input. |

10 |

1 |

– |

|

The management plan adequately considers monitoring and reporting on the state of the wetland's ecological character on a continuing basis. |

8 |

1 |

2 |

|

The management plan will be reviewed every seven years. |

2 |

9 |

– |

(a) The management plan is in draft form and currently available for public comment.

Note: CMAs' RWSs assume an eight-year review cycle. This analysis included the draft management plan for Western Port. Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula does not have a management plan and was rated as 'not met' for all categories.

Source: VAGO based on the Australian national Ramsar management principles.

Overall, seven of the 10 plans assessed by VAGO ensured the ecological character of the site would be conserved by linking management actions to ecological values requiring conservation and protection. The draft Western Port plan also clearly links management actions and targets to the ecological character of the site. Three plans were assessed by VAGO as only partly meeting this requirement.

Eight of the plans only partly addressed the stated threats to ecological character, as they did not include management actions to address all the identified risks. Risks such as invasive animals and plants and changes in water level and flow were addressed well, but identified risks from recreational activity, changes in water quality and climate change were rarely addressed.

Recreational activities such as fishing and gaming provide social value but may pose a threat to ecological character. The impact of these threats was not identified in most management plans. Ducks are hunted at many sites, including at Lake Murdeduke and Lake Colongulac, part of the Western District Lakes site. One of the site's environmental values, identified in the management plan, is supporting waterbird habitat. However, the potential impacts of duck hunting—such as the accidental shooting of protected species and disturbances to habitat and fauna—have not been assessed.

Eight of the plans outlined requirements to monitor the effectiveness of actions, which were also identified in the ECD. These plans described what monitoring was required and the time frames and responsibility for it. The Gippsland Lakes Ramsar site management plan is an example of this approach.

Nine plans met the requirement for public consultation by issuing the draft plan/strategy for public comment, holding workshops with agencies and community groups, and indirect consultation through emails and advertisements.

2.4 Governance, oversight, and roles and responsibilities

Sound governance arrangements are required to manage Ramsar sites effectively due to the sites' complexity and the number of organisations involved. Clear roles and responsibilities and good oversight are required for the effective implementation of management plan actions. Together these reduce the risk of overlap and service gaps and increase accountability for the implementation of management plans.

Governance

Governance processes for implementing most management plans are generally poor. There is no robust governance framework, nor procedures in place to help implement plans in a risk-based, prioritised manner. As a result, there is limited evidence that plans are implemented as intended. While most management plans do assign lead agencies to activities, there is limited accountability for implementation and monitoring the impact of management activities. Without adequate governance, site managers mainly use their own planning priorities rather than being accountable for delivering management plan actions.

A number of management plans specify clear governance arrangements for their implementation and these should be used as better-practice models:

- The Gippsland Lakes plan directs agencies to prepare an implementation plan for each management action they are responsible for. East Gippsland CMA then collates these into a single plan, which also sets monitoring, evaluation and reporting requirements. The plan also specifies that a multi-agency Ramsar steering committee will be formed for the Gippsland Lakes.

- North Central CMA is developing an action plan for the Kerang Wetlands site, for which DELWP has provided $200 000. A steering committee of representatives from other agencies in the region has been set up to overcome the problem of agencies working in isolation. When completed, the action plan is expected to make clear what is required and from whom.

- Melbourne Water is both the site manager and plan owner for the Edithvale−Seaford Wetlands site. It has clear accountabilities for managing and monitoring the site and internal processes that ensure that it funds high-priority actions for Ramsar sites. Melbourne Water also tracks the implementation of its management activities. The Ramsar plan has 77 management actions. Of these, all high-priority actions have been implemented but 11 are uncompleted—these actions were not completed as they were no longer deemed a high priority.

While these examples illustrate effective operational governance arrangements, there is limited opportunity for site managers to have ongoing input into processes that impact the management of Ramsar sites. A wetland working group that includes representatives from Melbourne Water, Parks Victoria, CMAs, DELWP and the Commonwealth Government meets three times a year. The group discusses wetland management matters broadly, but Ramsar site matters are only discussed as required rather than being an ongoing agenda item. This forum shares information but lacks formal arrangements to help set priorities.

Oversight

Inadequate oversight of Ramsar site management means management plans are not always effectively implemented. DELWP, which is responsible for promoting the wise use and conservation of Ramsar wetlands and reporting on their ecological status, has limited oversight of how plans for all sites are implemented and evaluated.

Parks Victoria has poor oversight of the implementation of management plans for the 10 sites it manages. Parks Victoria carries out many habitat-management activities in these wetlands, which often result in improved environmental outcomes, and they work in collaboration with other partners to reduce threats—see Figure 2D. However, this work is mainly implemented through projects and specifically funded initiatives, so it is opportunistic and reactive to when funding is available. These activities are generally not guided by the current Ramsar management plan, and this can result in significant ecological risks not being addressed in a timely way.

Figure 2D

Examples of opportunistic management activities

|

Site |

Project |

|---|---|

|

Gippsland Lakes |

Water management at Sale Common During a dry period in 2008–10, the native plant giant rush spread throughout the Sale Common. Changes in the water created an environment that encouraged growth of the plant. The giant rush can provide excellent habitat for waterbird and colonial nesting species but can also create tall, dense stands, competing with other native vegetation and decreasing the ecological value of the wetland. The West Gippsland CMA and Parks Victoria responded by preparing a management strategy to drown the rush by artificially filling the wetland and maintaining high water levels for about three years. Rainfall filled the Sale Commons in 2010, resulting in the giant rush seedlings being drowned. Reducing the extent and density of the giant rush led to other vegetation types being restored. This management activity directly responds to a management action in the Gippsland Lakes Ramsar site management plan, which requires control of native invasive species such as the giant rush. |

|

Kerang Wetlands |

Protecting and enhancing priority wetlands This project, led by North Central CMA, aims to protect endangered and threatened flora and fauna species supported by the Kerang Wetlands site. This project ran over four years and ended on 30 June 2016, with no further funding available. It delivered land management activities within and near the wetlands including:

These activities respond to various actions in the Kerang Wetlands management plan, including controlling weeds, rabbits and foxes, mapping vegetation, and assessing the condition of the wetland. |

|

Western District Lakes |

Borrell-a-kandelop Wetland Restoration Project Between 2001 and 2014, Greening Australia, Parks Victoria and Corangamite CMA jointly carried out this project, aimed at preserving habitat for migratory birds through conservation work, including revegetation, building fencing and fox baiting. One of the major challenges at the Western District Lakes is that the site boundary abuts private land and some management activities depend on the willingness of local landowners to take part in the project. Part of this project was to stop grazing on the wetland. Parks Victoria engaged and negotiated with landowners to fence the boundary between the lake and private land. The Borrell-a-kandelop project started under the former management plan for the Western District Lakes, prepared in 2002. The name 'Borrell-a-kandelop' relates to the objective of the site's management plan—'protect and, where appropriate, enhance ecosystem services, processes, habitats and species.' Management activities for this project aligned to the priorities of the Ramsar site management plan. |

Source: VAGO based on information provided by Parks Victoria and CMAs.

In 2015, Parks Victoria introduced a new approach to improve its planning, governance and oversight processes for public parks and reserves, which includes Ramsar sites. This approach involves preparing management plans for 16 areas with similar landscapes. At present, no plan that covers a Ramsar site has been completed, so this process is not advanced enough to assess how well Ramsar sites will be catered for. The River Red Gums landscape plan, in the early stages of development, includes four Ramsar sites—Barmah Forest, Gunbower Forest, Kerang Wetlands and Hattah−Kulkyne Lakes. It is unclear how this plan will link to the relevant RWSs for these sites, which include Ramsar management plans.

Roles and responsibilities for implementation

Site managers and CMAs are generally responsible for developing and implementing management plans, but roles and responsibilities for specific actions are not always clear or documented. This means that, while lead agencies are identified, actions are not always implemented. CMAs led the development of Ramsar management plans for the Parks Victoria sites, where the plans are embedded in RWSs, but they are not fully responsible for the plans' implementation. This results in limited accountability for the implementation of management actions. This is not the case for Melbourne Water, which is the site manager for the Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands site—it is responsible for developing and implementing its management plan.

Most management plans also do not contain clear roles and responsibilities for monitoring the outcomes and effectiveness of management actions. As a result of this limited accountability, most site managers determine their own management priorities based on available funding and resources, rather than those identified through the Ramsar management planning process.

DELWP acknowledges that improvements should be made in governance and in better integrating agencies who have a role in Ramsar site management. It is planning to resource a Victorian Ramsar forum to bring together agencies with management responsibilities to share information, communicate issues and national updates, and progress issues across the state.

2.5 Funding for delivery

Inadequate resource planning is a major hurdle to the effective management of Ramsar sites in Victoria. Not all management plan actions are funded, so responsible agencies rely on grants. In addition, meeting sometimes competing Commonwealth and state priorities is challenging. DELWP advised that funds for management plans, generally in resource management, are limited.

Despite this, agencies should know what resources are required to manage these sites to avoid any change to their ecological character, and should budget appropriately.

State funding

In Victoria, funding is provided to DELWP through the State Budget process, and DELWP allocates a large portion of these funds to CMAs to deliver the actions in their RWSs. In addition, there are other grant and program-funding opportunities available.

Under its Waterway Health Program, DELWP provides CMAs with some funds for Ramsar site planning and on-ground management. DELWP also provides advice on developing Ramsar management plans to be embedded into RWSs and advice on renewal and/or development of standalone Ramsar site management plans.

CMAs apply for annual funding through the Victorian Water Programs Investment Framework, which includes a component to manage Ramsar sites. Funding is allocated through annual service level agreements (SLA) between CMAs and DELWP, covering projects related to river and estuary management, as well as wetlands. In 2015–16, only the SLA for North Central CMA had a dedicated Ramsar program for the Kerang Wetlands and Gunbower Forest Ramsar sites. The other SLAs integrated funding for Ramsar sites into general wetland projects.

With no dedicated funding for the management of Ramsar sites, CMAs also use funding from other sources, including the National Landcare Programme to plan and manage these sites. One CMA advised that the issue with this type of project-specific funding is that it is not ongoing and does not necessarily need to be spent on monitoring or maintenance activities.

Under RWSs, Parks Victoria and other agencies are assigned management actions. However, these actions do not have funds specifically allocated to them. CMAs are funded to complete management activities in priority waterways and may allocate funding to other agencies, including Parks Victoria, to complete this work.

DELWP and Parks Victoria have a management service agreement detailing arrangements for managing parks and reserves. The agreement does not make specific funding provisions for the management of Ramsar wetlands but does cover environmental management activities—threatened species, invasive plants and animals, native animal management, habitat restoration, catchment and water management, ecological fire management and marine management. Many of these activities are undertaken at Ramsar sites.

As environmental management is part of Parks Victoria's core service, it should be able to assess and know what resources it requires to manage its 10 Ramsar sites, but it currently cannot do so. Parks Victoria is aware of this is issue and intends to collect this information as it introduces its new planning process.

Figure 2E details funding spent at each Ramsar site for the last two years. However, we are not confident about the reliability and completeness of this information and had difficulty compiling this data. Parks Victoria did not have this information readily available because it tracks expenditure at a program level rather than at a Ramsar site level. Parks Victoria demonstrated that it could provide a reasonable estimate of the funds it expends at each site.

Figure 2E Funding for Ramsar sites

|

Ramsar site |

State funding ($) |

Commonwealth grants ($) |

Joint funding / TLM(a) ($) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2014–15 |

Total state |

Parks Victoria |

||

|

Barmah Forest |

67 547 |

20 047 |

553 223 |

237 872 |

|

Corner Inlet |

228 305 |

11 825 |

745 000 |

– |

|

Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands |

309 170(b) |

– |

– |

– |

|

Gippsland Lakes |

4 749 860 |

126 100 |

31 500 |

– |

|

Gunbower Forest |

15 120 |

15 120 |

747 550 |

– |

|

Hattah–Kulykne Lakes |

151 166 |

151 166 |

887 247 |

1 277 373 |

|

Kerang Wetlands |

143 000 |

32 000 |

522 440 |

– |

|

Lake Albacutya |

10 250 |

10 250 |

95 404 |

– |

|

Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula |

1 508 640(c) |

21 600 |

893 940 |

– |

|

Western District Lakes |

345 000 |

25 000 |

30 000 |

– |

|

Western Port |

726 600(c) |

40 000 |

550 000 |

– |

|

Total |

8 254 658 |

453 108 |

5 056 304 |

1 515 245 |

|

2015–16 |

Total state |

Parks Victoria |

||

|

Barmah Forest |

200 924 |

100 924 |

442 578 |

318 083 |

|

Corner Inlet |

355 699 |

16 000 |

585 385 |

– |

|

Edithvale–Seaford Wetlands |

791 615(b) |

– |

– |

– |

|

Gippsland Lakes |

1 795 606 |

149 250 |

56 000 |

– |

|

Gunbower Forest |

85 060 |

17 400 |

346 964 |

– |

|

Hattah–Kulykne Lakes |

355 794 |

157 360 |

373 638 |

1 870 455 |

|

Kerang Wetlands |

468 642 |

4 200 |

209 166 |

– |

|

Lake Albacutya |

37 107 |

14 530 |

75 534 |

– |

|

Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula |

1 230 678(c) |

31 650 |

68 975 |

– |

|

Western District Lakes |

63 000 |

7 000 |

30 000 |

– |

|

Western Port |

421 600(c) |

43 500 |

306 225 |

– |

|

Total |

5 805 725 |

541 814 |

2 494 465 |

2 188 538 |

(a) 'Joint funding' comprises funding from Victoria and the Commonwealth Government. Funding from 'The Living Murray' (TLM) initiative comprises contributions from Victoria, other state and the Commonwealth governments—see Figure 2F.

(b) Entire contribution from Melbourne Water.

(c) Includes contributions from Melbourne Water made up of:

For 2014–15, Melbourne Water contributed $1 412 040 to Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula and $686 600 to Western Port.

For 2015–16 Melbourne Water contributed $908 400 to Port Phillip Bay (Western Shoreline) and Bellarine Peninsula and $274 600 to Western Port.

Note: Parks Victoria contribution is included in the state funding column.

Source: VAGO based on information provided by DELWP, Parks Victoria, Melbourne Water and CMAs.

Commonwealth Government support

From 2008–09 to 2011–12, the Commonwealth Government had a Ramsar program that funded the development and review of ECDs, updates to some RISs, and the first Ramsar Rolling Review in 2011. While the Commonwealth Government does not currently fund these, funding from Commonwealth programs has been used for on‑ground management activities at Ramsar sites. Some of these programs are summarised in Figure 2F.

Figure 2F

Selected Commonwealth/joint programs relevant to Ramsar sites

| Caring for our Country —this natural resource management investment program was largely focused on delivering outcome targets against six national priority areas. Actions that supported the environmental Ramsar values formed a key aspect of the coastal and critical aquatic habitat priority area. These actions included restoring and protecting nationally significant threatened species and ecological communities, and controlling weeds of national significance. The first stage of the grant program ran between June 2008 and 2012. The second stage ran between 2012 and December 2015.