Ravenhall Prison: Rehabilitating and Reintegrating Prisoners

Overview

In this audit, we examined if Corrections Victoria and GEO Group have developed best practice prisoner management at Ravenhall to rehabilitate offenders and reduce recidivism. We also assessed if there are effective performance and evaluation frameworks in place to measure these outcomes.

Transmittal letter

Independent assurance report to Parliament

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2020

PP No 118, Session 2018–20

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Ravenhall Prison: Rehabilitating and Reintegrating Prisoners.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

19 March 2020

Acronyms

Acronyms

| ACSO | Australian Community Support Organisation |

| AIC | Australian Institute of Criminology |

| AOD | alcohol and other drugs |

| CJS | Corrections and Justice Services |

| CV | Corrections Victoria |

| CVRP | Corrections Victoria Reintegration Pathway |

| DJCS | Department of Justice and Community Safety |

| FISP | Funded Individual Support Package |

| GLAT | Good Lives Assessment Tool |

| GLM | Good Lives Model |

| IRP | Individual Reintegration Plan |

| KPI | key performance indicator |

| LPA | local plan agreement |

| MCM | Melbourne City Mission |

| OBP | offending behaviour program |

| RNR | Risk Needs Responsivity |

| RoGS | Report on Government Services |

| RTT | Reception Transition Triage |

| SDAC-21 | Structured Dynamic Assessment Case-Management Tool |

| SDO | service delivery outcome |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

Abbreviations

| GEO | GEO Group Australia Pty Ltd |

| Ravenhall | Ravenhall Correctional Centre |

Audit overview

A prison sentence is not enough to break the cycle of reoffending if the underlying issues that contribute to it are not addressed. For this reason, the complex process of successfully rehabilitating offenders extends beyond the criminal justice system. Factors such as social disadvantage, unemployment, homelessness, and health and wellbeing also influence a prisoner’s ability to reintegrate into the community.

Rehabilitating and reintegrating prisoners is a core principle of the criminal justice system and a strategic priority for Corrections Victoria (CV), a business unit of the Corrections and Justice Services (CJS) group at the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS).

Ravenhall Correctional Centre (Ravenhall) is Victoria’s newest prison. Privately operated by the GEO Group Australia Pty Ltd (GEO), it was designed to trial new rehabilitation methods that focus on reducing reoffending. To strengthen the prison’s focus on rehabilitation, the state included financially incentivised key performance indicators (KPI) linked to reintegration and recidivism targets in GEO’s contract. This includes KPI 15, which measures reintegration outcomes and KPI 16, which measures rates of reoffending. Among Victorian prisons, performance payments for reintegration and reoffending outcomes are unique to Ravenhall.

Running prisons is a considerable expense for the state and costs are rising. Between December 2012 and December 2019, Victoria’s prison population grew by 58 per cent. More offenders are also returning to prison after their release.

In this audit we assessed if CV and GEO have set up a strategic and operational environment at Ravenhall to help reduce recidivism. We also examined if CV and GEO have developed best practice prisoner management to rehabilitate offenders and reduce recidivism, and if they have effective performance frameworks to evaluate these outcomes.

Conclusion

Changes CV made to Ravenhall’s strategic and operational environment before and after it opened have significantly compromised its ability to achieve its prisoner rehabilitation objectives. CV’s decision to increase the number of places for remand prisoners, and the higher-than-expected proportion of short stay sentenced prisoners, has made GEO’s model for reducing recidivism less relevant to its prisoner population. As fewer prisoners are therefore experiencing the model as GEO originally intended it, it cannot be as effective at reducing Ravenhall’s reoffending rate.

Further, gaps and flaws in CV’s performance and evaluation framework for Ravenhall mean, as yet, it will not be possible for the state to properly learn about the success or otherwise of the unique features of the Ravenhall model on reducing recidivism. The design of KPI 16 means CV cannot fully attribute performance against it to GEO, and the measure for KPI 15 (which is now being revised) is unclear and impractical to implement.

CV also does not have an evaluation framework to assess the actual link, if any, between GEO’s rehabilitation interventions and its recidivism outcomes. The absence of an evaluation framework to understand Ravenhall’s results is a significant missed opportunity.

Findings

Ravenhall Correctional Centre

Contract changes

|

A remand prisoner is a person who has had a charge laid against them but has not had their proceedings finalised. Remand prisoners are not released on bail and await trial or sentencing in prison. |

CV made significant changes to Ravenhall’s contract to help ease the system wide impact of growing prisoner numbers. These changes occurred both before and after the prison opened. The changes included introducing remand prisoners, which now make up 52 per cent of Ravenhall’s population, and increasing its number of prisoner places.

As of 31 December 2019, Ravenhall has 1 300 available prisoner places. GEO is waiting for CV to finalise another contract change to increase its number of prisoner places beyond 1 300, which is its design capacity.

CV and GEO agreed in principle that Ravenhall’s focus on rehabilitation and reintegration would be preserved throughout the contract changes. However, these significant changes occurred during Ravenhall’s first two years of operation—a period in which it was still settling and developing its culture.

Rehabilitation and reintegration services

GEO uses an evidenced based model to assess and treat prisoners’ individual risks of reoffending.

GEO designed Ravenhall’s rehabilitation programs for sentenced prisoners who stay at Ravenhall for three months or longer. However:

- half of Ravenhall’s prisoners are remandees

- more than half of all prisoners, on their release, have spent less than three months at Ravenhall.

Data from January 2019 to December 2019 shows that remand, together with sentenced short-stay prisoners (who serve less than three months) made up approximately 70 per cent of Ravenhall’s prisoner population. As a result, GEO’s original model for reducing recidivism is less relevant to its current prisoner population and therefore cannot be as effective at reducing reoffending.

GEO’s post-release model is designed to identify and address prisoners’ individual requirements, particularly those with high community reintegration needs.

From November 2017 (when Ravenhall first received prisoners) to December 2019, remand and short-stay prisoners did not have access to intensive post-release and case management services. This is because CV initially believed that, as part of the contract changes, GEO should provide these services at no extra cost to the state. CV has since recognised that intensive post-release services for remand prisoners was outside of the scope of the contract change. As of December 2019, CV has funded GEO to provide these services for a period of three years.

GEO has multiple assessment tools to identify prisoners’ post release needs. When we reviewed the files of 20 Ravenhall prisoners, we found that GEO has not consistently applied its assessment tools. Some eligible prisoners did not receive timely risk assessments, while other forms of assessments were completed late, or inconsistently.

Comparison to the public system

We compared Ravenhall’s model to the public system to identify any learnings or better practice that could be shared across the system. We found that CV’s Reintegration Pathway, which is used in public prisons, and GEO’s Continuum of Care model are aligned. Both models are based on the same underlying principles and offer similar services. Alignment between these models is important to ensure that all Victorian prisons are integrated and operate as one system.

However, GEO’s Continuum of Care model has some unique features, including:

- continuity of care—former prisoners have access to the same clinicians and staff they engaged with at Ravenhall after their release

- the Bridge Centre—a community reintegration centre where former prisoners can seek post-release support and assistance

- family involvement—the Bridge Centre hosts information nights and provides specialised services to support former prisoners’ families.

It is too early to determine if these features are improving prisoner outcomes compared to the public system. We encourage CV to monitor and compare outcomes as GEO’s model progresses.

Monitoring and evaluating performance

Performance indicators

|

KPI 15 incentivises GEO to use interventions that match prisoners’ post release needs in education and training, employment, housing, alcohol and other drugs (AOD) and mental health. |

GEO will receive performance payments of up to $1 million per year for achieving the KPI 15 and 16 targets. This collective $2 million is a small percentage of the overall service payment available to GEO. While KPIs 15 and 16 measure outcomes, several of GEO’s other performance measures also directly relate to rehabilitation and reintegration services.

KPI 15 measures GEO’s success at reintegrating prisoners and KPI 16 measures the rate at which Ravenhall prisoners return to prison within two years. These KPIs are narrow and, on their own, cannot meaningfully measure the prison’s recidivism outcomes.

KPI 15 is not working as intended and has proven difficult for GEO to design and implement. Originally, CV and GEO had different interpretations of the KPI. For example, they did not agree on which prisoners are eligible to be counted. CV and GEO are finalising revisions to KPI 15 based on a new shared understanding of who should be counted and how performance is assessed. Consequently, all KPI 15 results are under review and CV may retrospectively adjust GEO’s past performance payments.

|

KPI 16 incentivises GEO to achieve a lower return to prison rate than the average rate for other prisons. GEO is aiming to achieve a 12 per cent lower rate for Ravenhall’s general prisoner population and a 14 per cent lower rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander offenders. |

KPI 16 is not an appropriate measure for determining performance payments because it does not consider the amount of time an offender spends at Ravenhall or how much of their sentence they serve there. As a result, the KPI cannot effectively link prisoners’ reoffending outcomes to Ravenhall’s unique programs and interventions.

Additionally, KPI 15 and 16 do not include or measure remand prisoners. The substantial increase in remand prisoner numbers at Ravenhall therefore limits CV’s ability to assess the success of GEO’s Continuum of Care model.

Evaluating outcomes

CV has no plan to evaluate Ravenhall’s outcomes beyond the KPI measures, despite the prison having a key objective to trial new methods to reduce reoffending. This means that if Ravenhall has a lower rate of recidivism than other prisons, CV does not have an evaluation framework capable of understanding the links between Ravenhall’s specific interventions and its results.

CV regularly conducts research and evaluation projects about reintegration and reoffending measures. However, it does not have any system wide evaluations currently planned.

Performance outcomes to date

Beyond KPI 15 and 16, a number of Ravenhall’s other service delivery outcomes (SDO) and KPIs measure outputs relating to reintegration and rehabilitation, such as education and program completion rates. Ravenhall has had mixed performance results for these other measures. As a relatively new prison, we expected that it would take time for it to embed its programs and begin meeting its performance targets. Initially Ravenhall did not meet its performance targets for:

- SDO 14—prisoner engagement in purposeful activity

- SDO 15—vocational education and training

- SDO 23—case management.

GEO has made changes to address these performance issues. While GEO did not achieve its performance targets for SDO 14 and 23 in the second half of 2019, it achieved improved outcomes. Notably, GEO has consistently passed SDO 15 from July 2019 to December 2019 after its benchmark was adjusted. CV and GEO have also revised several SDO and KPI benchmarks and definitions to ensure they are appropriate for Ravenhall’s changed prisoner cohort.

Recommendations

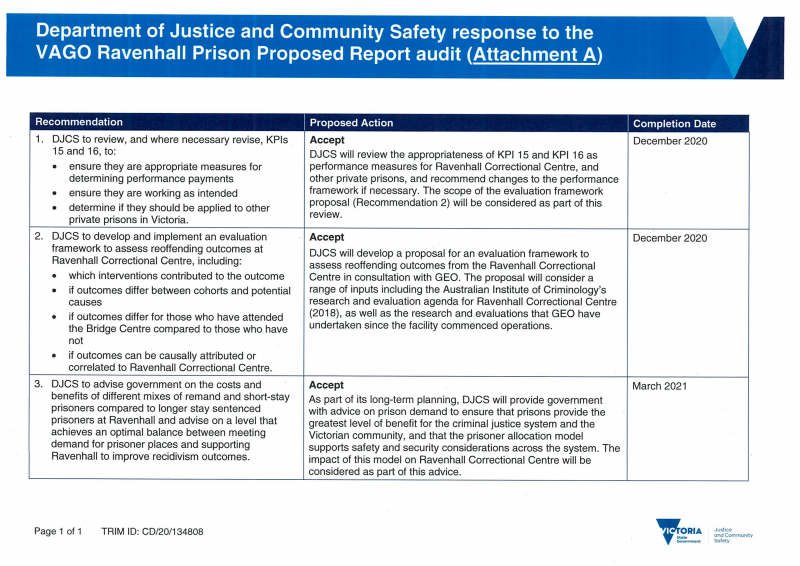

We recommend that the Department of Justice and Community Safety:

1. review, and where necessary revise, KPIs 15 and 16, to:

- ensure they are appropriate measures for determining performance payments

- ensure they are working as intended

- determine if they should be applied to other private prisons in Victoria (see Section 3.2)

2. develop and implement an evaluation framework to assess reoffending outcomes at Ravenhall Correctional Centre, including:

- which interventions contributed to the outcome

- if outcomes differ between cohorts and potential causes

- if outcomes differ for those who have attended the Bridge Centre compared to those who have not

- if outcomes can be causally attributed or correlated to Ravenhall Correctional Centre (see Section 3.3)

3. advise government on the costs and benefits of different mixes of remand and short-stay prisoners compared to longer stay sentenced prisoners at Ravenhall and advise on a level that achieves an optimal balance between meeting demand for prisoner places and supporting Ravenhall to improve recidivism outcomes (see Sections 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DJCS and GEO and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments.

We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A:

- DJCS accepted the three recommendations directed to it and provided an action plan detailing how it will address them.

- DJCS noted the context that Ravenhall’s contract changes were made in and outlined CV and GEO’s work to date to refine KPI 15.

- GEO stated that while Ravenhall’s prisoner cohort has changed, it is committed to rehabilitation and reintegration.

1 Audit context

1.1 Rehabilitation and recidivism

Over 99 per cent of people sentenced to prison in Victoria will be released, so successfully rehabilitating prisoners is in the public’s interest. Wherever possible, rehabilitation involves preparing prisoners to reintegrate and make a meaningful contribution to the community.

|

Rehabilitation aims to |

Rehabilitating offenders is complex and extends beyond the role of the criminal justice system. Many factors influence a prisoner’s ability to positively reintegrate into the community. CV focuses on the following areas:

- housing

- employment

- education and training

- independent living skills

- mental health

- alcohol and other drugs

- family and community connectedness.

Victorian prisons provide pre and post-release programs that target these areas and other risk factors.

Recidivism

|

Recidivism measures the rate at which a convicted criminal reoffends within a specified period of time after completing their sentence. |

While rehabilitation is a well-established goal for CV, measuring it is complex. One way that justice systems and researchers assess rehabilitation is to measure recidivism.

Recidivism is measured in a range of ways. Measures can be based on different types of crime and time frames after a prisoner’s release, and may be triggered by rearrest, reimprisonment, or self-reported criminal behaviour.

Contributing factors

The Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) has established that the following factors increase the likelihood of a person reoffending:

- age—young offenders are more likely to reoffend

- gender—some studies have found that males are more likely to reoffend than females

- cultural group—Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are over-represented in the criminal justice system and are more likely to reoffend than offenders from other cultural groups

- criminal history—this includes the timing and number of previous offences

- offence type—offenders who commit property offences or robbery/theft are more likely to reoffend than offenders of other crime types, including violent offenders

- demographic—unemployment, low education levels, living in low socioeconomic areas and low family attachment influence reoffending

- health—in particular, mental health problems and drug use influence reoffending.

Recidivism in Victoria

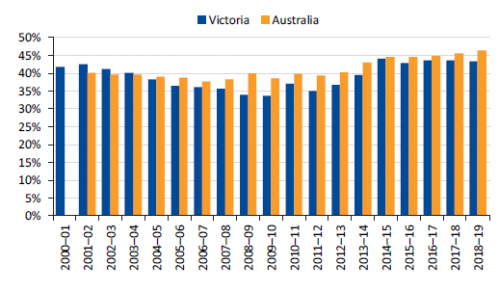

The Productivity Commission annually reports on national and state return to prison rates in its Report on Government Services (RoGS).

RoGS’s measures of reoffending rates include the proportion of adults:

- released from prison after serving a sentence who returned to corrective services (prison and community corrections measured separately) with a new correctional sanction within two years

- discharged from community corrections orders who returned to corrective services (prison and community corrections measured separately) with a new correctional sanction within two years.

Between 2001 and 2010, the rate of offenders who returned to prison within two years fell to a low of 33.7 per cent in Victoria. This change was largely consistent with national trends. Since 2010, the rate has increased, sitting above 40 per cent for the past five years. In 2018–19, Victoria’s return to prison rate was 43.3 per cent, which is slightly above its target of 41 per cent.

Figure 1A

Comparison of return to prison rates within two years

Note: Australian data for 2000–01 is unavailable.

Source: 2020 RoGS and the Department of Justice and Community Safety Annual Report 2018–19.

Increased demand on the justice system

Between December 2012 to December 2019, Victoria’s prisoner population increased by approximately 58 per cent. Over a similar period, Victoria’s population only increased by 17 per cent. While the rise in recidivism rates has contributed to this, a large proportion of this increase has come from a surge in the remand prisoner population, which has more than tripled since June 2013.

The number of remand prisoners in the Victorian system has increased due to multiple legislative and procedural changes over the past five years. These changes include reforms to bail and parole processes, changes to sentencing laws and the abolition of suspended sentences and home detention. Population growth and significant increases in police resourcing have also led to more crime being detected.

1.2 Ravenhall Correctional Centre

Ravenhall is a men’s medium-security prison that is privately operated by GEO. Ravenhall first received prisoners in November 2017. It opened with 1 000 available prisoner places but had the capacity for 1 300. This included 75 forensic mental health beds.

Service focus

The state designed Ravenhall to have a targeted focus on rehabilitation and reducing recidivism. The prison’s physical design and services were guided by this goal. Ravenhall’s seven key focus areas are shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Ravenhall’s key focus areas

Source: VAGO, based on documents provided by CV.

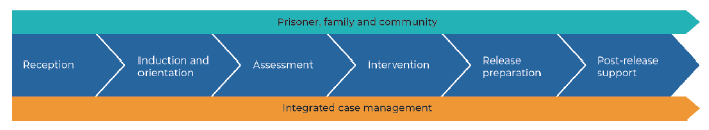

Figure 1C

GEO’s Continuum of Care model

Source: VAGO, based on GEO.

Reintegration and rehabilitation services

|

Reintegration is the process of re entering a prisoner into society. This includes the reinstatement of their freedoms. Factors that can influence the success of this process include a person’s social and cultural adjustment, lifestyle changes and if their criminal behaviours have been treated or addressed. |

GEO’s Continuum of Care model, shown in Figure 1C, integrates prisoner management with its pre and post-release support programs and services. GEO designed the model to address antisocial behaviours and help prisoners develop skills to reintegrate into society. The model includes specific treatment and service pathways for serious violent offenders, family violence perpetrators, general (non-violent) offenders and prisoners with alcohol and other drug abuse issues.

GEO provides support services within the context of its Continuum of Care model. Prisoners transition through the model from their reception at Ravenhall to their release. After their release, they can continue to access services with the same clinical staff.

Alliance Partners

GEO delivers its programs and services using in-house clinical and program staff as well as external subcontracted providers, called Alliance Partners. GEO’s Alliance Partners are YMCA, Melbourne City Mission (MCM) and Kangan Institute.

Alliance Partners work to increase prisoners’ education and vocational training, personal development and life skills and prepare them for release. To do this, Alliance Partners deliver programs including TAFE courses, and industry, social and life skills workshops.

GEO also subcontracts Forensicare and Correct Care to provide health and forensic mental health services at Ravenhall.

The Bridge Centre

The Bridge Centre is a community-based reintegration facility located in Richmond. At the Bridge Centre, prisoners can access post-release services delivered by Alliance Partners and GEO’s clinical and reintegration staff. Former Ravenhall prisoners can access services and support through the Bridge Centre for up to two years after their release.

1.3 Measuring Ravenhall’s performance

CV monitors and measures the performance of all private prisons against the SDOs and KPIs outlined in each operator’s contract with the state. These SDOs and KPIs relate to:

- safety and security

- health services

- programs and reintegration

- facility management

- availability and accuracy of performance data.

In its contract with GEO for Ravenhall, the state has developed specific KPIs to measure prisoner reintegration and recidivism outcomes.

Key performance indicator 15—reintegration services

GEO designed KPI 15, which CV approved during the Ravenhall procurement process. KPI 15 measures if Ravenhall’s interventions successfully address its prisoners’ post-release needs. As shown in Figure 1D, KPI 15 has five pathways aligned to key reintegration factors. To identify a prisoner’s post-release needs, GEO staff conduct a needs assessment within six weeks before their release. This assessment covers key reintegration factors.

Prisoners who are eligible to be included under KPI 15 are known as ‘pathway participants’. GEO reports on the percentage of its pathway participants that achieve the target outcome for each KPI pathway.

Figure 1D

KPI 15 pathways and target outcomes

|

Pathway |

Target outcome |

|

|---|---|---|

|

15.1 |

Education and training |

The pathway participant has enrolled in and attended appropriate education or training activities as defined in their Individual Reintegration Plan (IRP) within two months of their release. |

|

15.2 |

Employment |

The pathway participant has maintained stable employment (full‑time or part‑time) of 20 hours or more per week for two months following their release. |

|

15.3 |

Housing |

The pathway participant has maintained stable accommodation at a personal or public residence for two months following release. |

|

15.4 |

AOD treatment |

The pathway participant has been referred to and maintained AOD treatment as defined in their IRP or as recommended by the Australian Community Support Organisation (ACSO) for two months following their release, or for a such lesser period if recommended by ACSO. |

|

15.5 |

Mental health treatment |

The pathway participant has been referred to and maintained mental health treatment as defined in their IRP for two months following their release. |

Source: VAGO, based on documents provided by CV.

GEO began reporting its performance against KPI 15 to CV for the period of April to June 2018, which was Ravenhall’s third quarter of operation.

Key performance indicator 16—reducing recidivism

KPI 16 measures the rate at which prisoners released from Ravenhall return to any Victorian prison within two years after their release. This KPI is designed to indicate the effectiveness of Ravenhall’s rehabilitation services in reducing recidivism compared to the broader prison system.

As shown in Figure 1E, KPI 16 has two components. CV will begin calculating KPI 16 results in 2021 for prisoners released in 2018–19.

Figure 1E

Components of KPI 16

|

Component |

Measure |

|---|---|

|

16A |

Compares the difference in percentage between the rate of return to prison of:

The rate of return is measured two years after release. Each year, Ravenhall will aim to reduce its rate of return to prison by 12 per cent compared to other prisons. |

|

16B |

Compares the difference in percentage between the rate of return to prison of:

The rate of return is measured two years after release. Each year, Ravenhall will aim to reduce its rate of return for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners by 14 per cent compared to other prisons. |

Source: VAGO, based on CV documents.

Performance payments

Private prisons, including Ravenhall, are eligible for a quarterly performance payment, which is made up of six components. One of these components is the service-linked fee, which pays prisons for successfully achieving their KPIs and SDOs.

Ravenhall’s KPI 15 and 16 are incentive-based payments. This means that GEO is financially rewarded if it achieves its KPIs, but not financially penalised if it does not. GEO can receive performance payments of up to $1 million per year for each of its KPI 15 and 16 targets.

Ravenhall is the first prison in Australia to have service payments linked to its recidivism outcomes. If successful, the state can learn from Ravenhall and potentially roll out this incentive across Victoria.

1.4 Ravenhall’s prisoner cohort

While Ravenhall was initially contracted to hold 1 000 prisoner places, it was built with the capacity for 1 300 in case the state required them. These additional 300 places were activated in July 2018—nine months after Ravenhall commenced operations.

As of 31 December 2019, CV and GEO are finalising a contract variation to further increase the number of available prisoner places at Ravenhall to above its design capacity of 1 300.

Remand prisoners

Excluding its 75 forensic mental health beds, Ravenhall was intended to exclusively hold sentenced prisoners.

Before it opened, the state amended Ravenhall’s contract to hold 450 remand prisoners, which was 45 per cent of its total population at the time. CV has since increased this number. As of 31 December 2019, Ravenhall is contracted to hold up to 675 remand prisoners, which is 52 per cent of its total population.

Remand prisoners present different challenges and risks than sentenced prisoners, such as cost, transition needs, family support and facilities. Remand prisoners have ongoing legal matters and may need to be transferred to and from prison more often. This creates a more unsettled prison environment.

Based on their presumption of innocence, remand prisoners are entitled to less restrictive conditions and have different rights to sentenced prisoners. For example, remand prisoners are not required to participate in programs or work. They often have significant drug and alcohol abuse issues and a higher prevalence of physical and/or mental health issues.

1.5 Roles of agencies and associated entities

Corrections Victoria

CJS is a business unit within DJCS. It is responsible for custodial operations, offender services, security and intelligence, and sentence management. CJS also includes Justice Health and Justice Services.

CV sits within CJS and is responsible for establishing, managing and overseeing the security of Victoria’s prisons in line with their legislative requirements. CV’s key functions include:

- facilitating correctional operations across the state

- establishing standards and monitoring performance against them.

In public prisons, CV aims to rehabilitate prisoners and reduce reoffending by delivering programs and services that encourage positive behaviour changes.

CJS represents the state in all its contracts with privately operated prisons, including Ravenhall. It manages these contracts to ensure that private operators adhere to the required standards and performance expectations.

The GEO Group Australia Pty Ltd

GEO privately operates Ravenhall as part of a public–private partnership. Under its contract with the state, GEO provides accommodation services (suitable for prisoner containment) and correctional services (to maintain the safety, security and welfare of prisoners). These services must comply with the relevant state legislation and policies.

GEO also provides prisoners with education and training, employment within prison, health services, and rehabilitation and reintegration interventions and services.

1.6 Previous reviews

Our 2018 audit Managing Rehabilitation Services in Youth Detention examined how well rehabilitation services were meeting the developmental needs of children and young people in the youth detention system and reducing their risk of reoffending.

We found that young people in detention had not been receiving the rehabilitation services they were entitled to and necessary for their needs. As a result, youth detention had not been effectively reducing reoffending because correction facilities were not providing adequate services, case management and needs assessments. Correction facilities were also prioritising security over offenders’ education and health.

Other integrity bodies

The Victorian Ombudsman’s 2015 investigation into prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration in Victoria found that the current system is not sustainable. The Ombudsman found that increases in prisoner numbers had reduced the system’s ability to deliver consistent and effective rehabilitation and reintegration services.

1.7 Why this audit is important

Ravenhall is an opportunity to trial new methods to reduce reoffending. This is a core principle of the criminal justice system and a strategic priority for CV.

Ravenhall is also the first prison in Australia to have financially incentivised KPIs for reducing recidivism. It is in the state’s interest to ensure that these measures promote best practice in prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration. If this approach is effective, then it could be rolled out across Victoria to help reduce the high running costs and overcrowding of prisons.

We intend for this audit to be longitudinal and conducted in two phases.

In this first phase, we have sought to identify any early gaps or weaknesses in the design and implementation of Ravenhall’s rehabilitation initiatives. We have also examined the appropriateness and effectiveness of CV and GEO’s proposed performance monitoring and evaluation framework, including the KPIs.

The second phase of this audit will assess if GEO has achieved its proposed outcomes to reduce reoffending at Ravenhall compared to other prisons. In the second phase, we will report on the impact of GEO’s new model and assess if the state has achieved a return on investment for this innovative approach in prison management.

1.8 What this audit examined and how

In this audit we examined if CV and GEO have developed best practice prisoner management at Ravenhall to rehabilitate offenders and reduce recidivism. We also assessed if there are effective performance and evaluation frameworks in place to measure these outcomes.

To do this we:

- interviewed staff from CV, GEO, Ravenhall’s Alliance Partners and key stakeholders

- visited Ravenhall and observed how GEO manages and operates it

- reviewed key CV and GEO documents

- undertook a file review of 20 Ravenhall prisoners. We did this by selecting 20 sentenced prisoners that were discharged in December 2018 or June 2019. This is approximately 8 per cent of the 243 sentenced prisoners who were discharged in those two months.

We conducted our audit in accordance with the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $402 000.

1.9 Report structure

The rest of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the contractual changes to Ravenhall and how these impact its service delivery.

- Part 3 examines Ravenhall’s performance and how this has been monitored and evaluated.

2 Rehabilitation and reintegration at Ravenhall

Ravenhall has a focus on trialling new approaches to reduce reoffending. These approaches include GEO’s Continuum of Care model and the Bridge Centre.

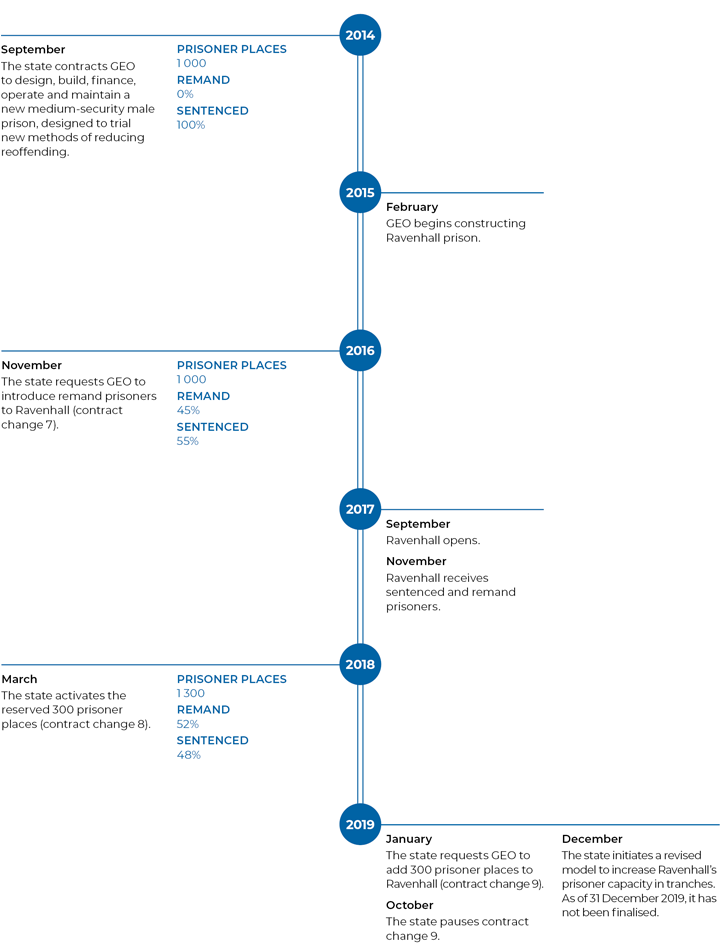

In response to growing prisoner numbers across the state, CV made changes to Ravenhall’s prisoner composition and increased its number of prisoner places. CV is progressing a contract variation to further increase Ravenhall’s prisoner places. At 31 December 2019, this has not been finalised. We outline CV’s changes to Ravenhall’s prisoner numbers and composition in Figure 2A.

In this Part, we assess the key contractual changes that CV made to Ravenhall. We also consider if Ravenhall’s service delivery model is appropriate for its current prisoner population.

2.1 Conclusion

In its first two years of operation, Ravenhall underwent significant changes to accommodate the state’s need to quickly accommodate the growing number of prisoners across the state. These changes have limited GEO’s ability to trial new approaches to reduce reoffending.

Most of Ravenhall’s prisoners are either short-stay, who typically serve sentences of three months or less, or remand. However, Ravenhall’s criminogenic programs and interventions, which aim to reduce reoffending, are designed to be delivered over longer periods to have more impact. Consequently, most of Ravenhall’s prisoners are unable to participate and benefit from these programs and interventions.

For this reason, GEO’s original model is unlikely to be as effective at reducing reoffending for its current prisoner population. This is a significant missed opportunity for the state to learn about and improve prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration.

2.2 Contract changes

CV made changes to Ravenhall’s contract to help ease system-wide capacity issues. We outline the three key contract changes that have affected Ravenhall’s rehabilitation and reintegration services in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Key Ravenhall events

Source: VAGO, based on CV and GEO documentation.

These three significant changes occurred during Ravenhall’s first two years of operation—a period in which it was still settling and developing its culture.

The impact of contract changes

In the contract negotiation documents, CV and GEO agreed in principle to preserve Ravenhall’s focus on rehabilitation and reintegration. CV requested the contract changes under its belief that:

- Ravenhall would retain its focus on rehabilitation services and deliver its Continuum of Care model to all prisoners, regardless of their sentence status

- remand prisoners have similar characteristics to sentenced prisoners and therefore, the prison’s seven key areas of focus would remain.

Despite CV’s intention, the contract changes have limited Ravenhall’s ability to reduce recidivism.

Contract changes 7 and 8—introduction of remand prisoners and increased prisoner places

In response to contract change 7, GEO developed a clinical service delivery model for remand prisoners and was able to offer remand prisoners many of its existing lifestyle programs and support services.

As remand prisoners have not been convicted of a crime, they cannot undertake programs designed to treat offending behaviour or reduce recidivism. In response to the contract change, GEO developed new programs with content and duration more suited to remand prisoners, who typically spend shorter periods in custody.

We note that contract changes 7 and 8 resulted in the following changes to Ravenhall’s rehabilitation and reintegration services:

- costs were reallocated

- clinician-to-prisoner ratios were reduced

- clinical services reached capacity

- prisoners’ out-of-cell hours were reduced

- intensive reintegration and post-release services for remand prisoners were required.

Reallocation of costs

The state requested the contract change to be cost neutral, and for GEO to implement changes by reallocating its service costs. The state acknowledged that GEO would likely divert costs from Ravenhall’s rehabilitation and reintegration services.

GEO estimates that approximately 10 per cent of Ravenhall’s rehabilitation and reintegration costs (consisting of staff and operating costs) were reallocated to custodial operations and administration.

Reduced clinician-to-prisoner ratio

Since the contract changes were introduced, Ravenhall’s clinician to prisoner ratio has reduced across the five communities it houses prisoners in. To address this, GEO recruited four remand reintegration officers. The reintegration officers are non-clinical staff who support the work of clinicians by assessing prisoners’ reintegration needs and making referrals.

Figure 2B shows the changes to Ravenhall’s clinician-prisoner ratios.

Figure 2B

Changes to Ravenhall’s funded clinician-to-prisoner ratios

|

Community |

Original ratio for 1 000 sentenced prisoners |

Ratio for 1 300 sentenced and remand prisoners |

|---|---|---|

|

Community 1: Mainstream sentenced |

1:17 |

1:25 |

|

Community 2: Youth and Aboriginal and |

1:17 |

1:25 |

|

Community 3: Remand |

1:17 |

1:26 |

|

Community 4/5: Protection |

1:23 |

1:29 |

|

Complex Needs Team |

1:16 |

1:16 |

Note: Protection refers to prisoners who need to be separated from other prisoners for their protection.

Source: VAGO, based on information provided by GEO.

Clinical services at capacity

The clinical team in each Ravenhall community delivers assessment and treatment services in line with Ravenhall’s Sentenced and Remand Clinical Service Delivery Model. In February 2019, GEO reported that with 1 300 prisoners, Ravenhall’s assessment and treatment services were at capacity and waitlists for its programs were growing. Figure 2F outlines the number of prisoners waitlisted for offending behaviour programs (OBP) and AOD programs.

Alongside reduced clinician-to-prisoner ratios, growing waitlists increase the risk that prisoners will receive less support than they would have had under Ravenhall’s original contract.

Reduced out-of-cell hours

GEO initially planned to offer Ravenhall prisoners 12 hours out of their cells each day. However, prior to the prison opening, CV approved GEO to reduce this to 11.50 hours to manage the introduction of remand prisoners. Since then, CV has approved a further reduction to 11.15 hours.

Spending time out of their cells allows prisoners to participate in rehabilitation and reintegration activities. It is also important for their mental health and wellbeing.

Requirement to provide intensive post release services for remand prisoners

Remand prisoners have always had access to Ravenhall’s reintegration and post release services. However, significant issues arose around GEO’s funding and provision of intensive pre and post-release services for remandees. Initially, CV considered that funding for these intensive services would be covered by the cost neutrality requirement. Consequently, GEO and CV had conflicting views about whether KPI 15 (reintegration) applied to remand prisoners.

CV now acknowledges that these intensive services were not funded. It has since provided GEO with three years of funding to deliver them. We discuss this further in Section 2.4.

Contract change 9—further increase to prisoner numbers

CV first initiated contract change 9 in January 2019. CV paused this change in October 2019 because statewide prisoner numbers did not increase as expected. In December 2019, CV initiated a revised contract variation to increase Ravenhall’s prisoner places in increments, rather than adding a fixed number of prisoners all at once. As of 31 December 2019, the revised model has yet to be approved and Ravenhall’s capacity remains at 1 300.

Activating prisoners in increments achieves better value for money for the state. This is because CV provides private prisons with an availability payment. This payment stream is based on the number of places a prison has available for use (regardless of whether the place is being used or not). Activating prisoner places in increments, rather than all at once, means that the state will not be paying for unused prisoner places.

If Ravenhall’s number of prisoner places increases beyond 1 300, then the previously negotiated contract change 9 provisions will apply. We identified the following issues associated with the contract change 9 process, and future increase in prisoner numbers that are likely to have negative consequences for Ravenhall’s rehabilitation and reintegration outcomes:

- double bunking

- prison infrastructure capacity and its impact on prisoners’ ability to engage in purposeful activity

- staffing uncertainty.

We discuss these issues below.

Double bunking

Double bunking is the practice of installing bunk beds for additional prisoners in cells designed to accommodate a single prisoner. In its modification request to GEO, the state acknowledged that single-cell occupancy is the preferred accommodation type in Victoria. However, in this circumstance CV was willing to accept alternative proposals, such as double bunking and other suitable alternatives, to quickly address the system-wide demand.

To prepare for Ravenhall’s planned increase to 1 600 places, GEO installed double bunks in cells designed for one prisoner. It installed double bunks in 212 single cells and a further 88 in the prison’s cottages and lodges.

Installing bunk beds allows the state to quickly accommodate additional prisoners, but it is not a preferable long-term solution. It is widely accepted among the corrections sector that bunks beds are associated with increased prisoner restlessness, disengagement, aggression and violence. An independent investigation into the 2015 Metropolitan Remand Centre riot identified double bunking as a contributor.

Infrastructure capacity and impact on purposeful activity

Ravenhall was only designed to hold 1 300 prisoners. The central areas of the prison (such as the industry buildings, community hub and kitchen) were designed for a maximum capacity of 1 300. If CV further increases its number of prisoner places, then Ravenhall will be pushed beyond its built capacity.

If prisoner places are increased, GEO and CV agreed in the initial contract change 9 to reduce Ravenhall’s benchmark for the number of hours prisoners engage in purposeful activity (such as employment, programs and education) by 2.5 hours per week. GEO had also planned to extend the opening hours of the learning hub and create additional but slightly shorter work shifts in the prison industries.

While these changes are yet to take place, they may result in prisoners spending less time participating in activities that develop life skills or contribute to their rehabilitation.

Staffing uncertainty

In addition to Ravenhall’s new process of activating and deactivating prisoner places in increments, the commencement, pause and current amendment to contract change 9 has created uncertainty about the prison’s staffing requirements.

In response to the initial planned increase to 1 600 prisoners, GEO recruited a significant number of additional staff across Ravenhall, many of whom are now surplus to its needs. Uncertainty about Ravenhall’s staffing requirements creates the risk that GEO will not be able to appropriately resource the prison, including its rehabilitation and reintegration team.

2.3 Ravenhall’s rehabilitation and reintegration services

GEO developed an evidence-based model to assess and treat each individual prisoner’s risk of reoffending. However, this model is best suited to sentenced prisoners who stay at Ravenhall for three months or longer.

Due to the contract changes, sentenced prisoners now make up only 48 per cent of Ravenhall’s population. Half of Ravenhall’s prisoners are remand, and most of the total cohort are short-stay. As a result, GEO’s model for reducing recidivism is not as relevant to Ravenhall’s current prisoner population and is unlikely to be as effective.

Did Ravenhall receive its expected prisoner cohorts?

Ravenhall’s prisoner cohorts include:

- prisoners with a mental illness

- prisoners with challenging behaviours

- young prisoners (under 25)

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners

- prisoners serving short sentences (less than 12 months).

Ravenhall has received the expected numbers of all these cohorts, except for short-stay prisoners.

Short-stay prisoners

GEO’s data shows that Ravenhall has held a significant number of short stay prisoners. While GEO expected to hold prisoners serving sentences less than 12 months, it stated that it did not anticipate the large number of prisoners serving less than three-month sentences.

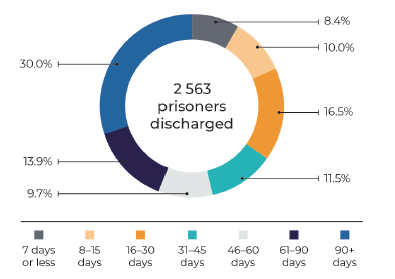

Figure 2C shows that 70 per cent of the prisoners discharged between January 2019 to December 219 spent less than 90 days at Ravenhall. This is significant because Ravenhall’s programs and interventions are designed for prisoners who serve sentences of three months or longer, which is consistent with evidence-based practices to reduce reoffending.

Figure 2C

Length of stay for sentenced and remand prisoners discharged between January–December 2019

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by GEO.

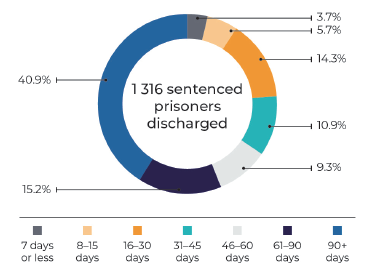

Within the sentenced cohort, only 40.9 per cent of discharged prisoners spent more than 90 days at Ravenhall, as shown in Figure 2D.

In line with Ravenhall’s Sentenced Clinical Service Delivery Model, sentenced prisoners who are serving less than 90 days are ineligible for criminogenic programs, which are designed to reduce the likelihood of them reoffending. GEO states that anything less than 90 days is not long enough for these programs to impact reoffending.

Of the 1 316 sentenced prisoners discharged between January 2019 and December 2019, only 18 spent more than 12 months at Ravenhall (1.3 per cent of sentenced discharges).

Figure 2D

Length of stay for sentenced prisoners discharged between January 2019–December 2019

Source: VAGO, based on data provided by GEO.

GEO has previously raised concerns with CV about the number of prisoners Ravenhall receives who have sentences of less than three months. The Ravenhall contract defines a short stay as a sentence of less than 12 months. It does not define a lower limit. Defining a lower limit would not be practical for CV, as it needs flexibility to manage the system-wide demand.

Is Ravenhall’s model evidence-based?

Ravenhall’s model combines two evidence-based rehabilitation models that target factors to aid reintegration. These are the Risk Needs Responsivity (RNR) model and the Good Lives Model (GLM).

The RNR model suggests that:

- criminal behaviour or risk can be predicted

- treatment should be targeted to prisoners’ needs

- application of treatment should depend on a prisoner’s responsiveness to it.

In comparison, the GLM is based on developing prisoners’ individual strengths. It encourages prisoners to develop meaningful and prosocial life goals.

By combining these two models, the Ravenhall model is designed to manage risk while developing prisoners’ individual capabilities. GEO uses these two models in its risk assessment and screening tools, which we discuss below.

Do Ravenhall’s pre-release services target its prisoners’ needs?

Assessment of prisoner risk and needs

GEO administers two risk assessment and treatment tools in addition to the ones that are used in the public system. As shown in Figure 2E, these are the:

- Structured Dynamic Assessment Case-Management Tool (SDAC-21), which is linked to the RNR model

- Good Lives Assessment Tool (GLAT), which is linked to the GLM.

These assessments apply to sentenced prisoners:

- who, through other system wide assessments, are identified as having a moderate-to-high risk of reoffending

- serving a sentence of more than six months.

Figure 2E

Risk assessment tools

| Tool |

What |

Why |

|---|---|---|

|

SDAC-21 |

Determines a prisoner’s risk factors |

|

|

GLAT |

Maps and explores what is important to each prisoner |

|

Source: VAGO, based on GEO documents.

Based on Ravenhall’s mix of remand and sentenced prisoners and length of stay data, these two assessments are now only relevant to approximately one quarter of its prisoners.

We reviewed the files of 20 Ravenhall prisoners discharged in December 2018 and June 2019. In the 20 files, only one of six eligible prisoners had a completed SDAC-21, and none had completed the GLAT. The remaining 14 were ineligible due to their sentence status or length of stay.

Prisoners also have their reintegration needs identified (including potential referrals to programs, education and support services) as part of their reintegration assessment. We discuss this further in Section 2.4.

Programs and length of stay

In Ravenhall’s operating instruction for its AOD programs and OBPs, GEO states that prisoners serving sentences of less than three months are ineligible to participate. This is regardless of their assessed risk of reoffending. This is because clinical programs need to be delivered over an appropriate length of time to have an impact. For short-stay prisoners, the focus is instead on transitional programs or services that support reintegration.

During 2019, half of Ravenhall’s sentenced prisoners served sentences of less than three months. This, alongside the fact that half of Ravenhall’s prisoners are remand, means that most of its prisoners are not eligible for criminogenic programs designed to reduce reoffending.

This was reflected in our review of prisoner files discussed later in this section and described in detail in Appendix B.

Program scheduling

GEO schedules programs to run within each of Ravenhall’s communities.

Each community has several program rooms where prisoners undertake programs with their peers. Prisoners are referred to these programs based on their individual needs.

A prisoner can only attend a program if it runs in their community during their time in custody. Some programs need minimum enrolment numbers to commence, which can affect their running frequency. In some instances, prisoners may be placed on waitlists for months before the program runs. As discussed earlier, most of Ravenhall’s prisoners spend a short time in custody. Consequently, the programs they are referred to may not be available during their time in custody.

Program waitlists

GEO reports monthly to CV on its OBP and AOD programs. In its reports, some of the AOD programs had high numbers of waitlisted prisoners. Figure 2F shows the average number of daily referrals and the average number of days prisoners are waitlisted for these programs.

Figure 2F

Average daily referrals and average number of days on waitlists for July–December 2019

|

Program |

July |

August |

September |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Referrals |

Waitlist |

Referrals |

Waitlist |

Referrals |

Waitlist |

|

Know the Score |

46 |

183 |

195 |

176 |

62 |

207 |

|

Skating on Ice |

26 |

150 |

198 |

162 |

43 |

183 |

|

Cannabis and Me |

32 |

86 |

25 |

108 |

28 |

91 |

|

Ice and Me |

77 |

43 |

47 |

48 |

66 |

55 |

|

Alcohol and Me |

16 |

52 |

27 |

44 |

33 |

58 |

|

Wised Up |

9 |

267 |

10 |

105 |

15 |

131 |

|

CBISA |

8 |

50 |

2 |

81 |

5 |

107 |

|

Program |

October |

November |

December |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Referrals |

Waitlist |

Referrals |

Waitlist |

Referrals |

Waitlist |

|

Know the Score |

45 |

151 |

56 |

177 |

25 |

181 |

|

Skating on Ice |

49 |

200 |

42 |

184 |

15 |

222 |

|

Cannabis and Me |

31 |

100 |

44 |

112 |

61 |

131 |

|

Ice and Me |

65 |

38 |

73 |

59 |

83 |

78 |

|

Alcohol and Me |

58 |

48 |

41 |

45 |

29 |

85 |

|

Wised Up |

0 |

112 |

21 |

115 |

4 |

132 |

|

CBISA |

0 |

80 |

4 |

106 |

2 |

73 |

Note: Referrals is the number of prisoners assessed and subsequently referred to a program.

Note: CBISA refers to the Cognitive Behavioural Interventions for Substance Abuse program.

Source: VAGO, based on GEO reporting to CV.

On average, prisoners experienced long wait times for the Know the Score, Skating on Ice, Cannabis and Me and Wised Up programs during this period. As contractually required, GEO creates its program schedule a year in advance. While GEO delivered its 2019 schedule, increased demand resulted in the wait times shown in Figure 2F. To address this, GEO has included additional AOD programs in the 2020 program schedule it submitted to CV.

Program completion rates

|

Gateway is GEO’s IT prison operating system. Both prisoners and staff have access to Gateway. GEO uses Gateway for prisoner movement, prisoner scheduling and case management. |

Prisoners access their daily schedule through GEO’s Gateway system. Every prisoner has access to Gateway through a secure computer built into their cell. While a prisoner may be scheduled for multiple activities at the same time, Gateway has an in-built prioritisation hierarchy. This means that prisoners only see the highest priority activity that they are scheduled for.

High priority activities include health appointments and activities that directly contribute to reducing reoffending (such as OBPs, education and vocation training or reintegration services), or activities that impact a prisoner’s eligibility for parole. Lower priority activities are those that do not count under SDO 14 (purposeful activity) or do not directly contribute to reducing recidivism (such as recreation).

In June 2019, GEO developed a comprehensive Gateway report to outline program scheduling, enrolments and completions. GEO provided us with a copy of this report covering the period from June 2019 to December 2019. We examined the number of prisoners who completed the programs they were enrolled in during this period.

Figure 2G shows that OBP and AOD programs, which are monitored by CV through SDO 18, have high completion rates. In contrast, lifestyle programs and programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners, which are not attached to SDOs, have lower completion rates. The lower completion rates for remand programs may have been influenced by the fact that remandees typically have a shorter length of stay than sentenced prisoners.

Figure 2G

Program completions rates for June–December 2019

|

Program category |

Programs scheduled |

Prisoners enrolled |

Prisoners attended |

Valid exceptions |

Category completion rates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OBPs |

751 |

5 240 |

4 544 |

141 |

89.4% |

|

OBP individual interventions |

2 534 |

2 620 |

1 808 |

95 |

72.6% |

|

AOD programs |

538 |

4 006 |

3 025 |

235 |

81.4% |

|

Aboriginal programs |

57 |

737 |

337 |

37 |

50.7% |

|

Personal development and life skills programs |

763 |

5 739 |

3 664 |

236 |

68.0% |

|

Remand programs |

264 |

2 746 |

1 781 |

238 |

73.5% |

Source: VAGO, based on GEO’s Continuum of Care report.

SDO oversight

SDO 18 measures:

- how many scheduled OBP and AOD programs prisons deliver (the benchmark is 100 per cent)

- how many prisoners enrolled in OBP and AOD programs complete them (benchmark is 85 per cent).

Ravenhall has passed SDO 18 in all quarters since it opened.

File review

We found that the Ravenhall model is best suited to mid to long-term sentenced prisoners. Their longer length of stay gives them the time to complete criminogenic programs that address their risk of reoffending.

We completed a file review of 20 Ravenhall prisoners by selecting 20 sentenced prisoners discharged in December 2018 or June 2019. This represents approximately 8 per cent of the 243 sentenced prisoners who were discharged from Ravenhall in those two months. We assessed if the 20 selected prisoners had completed programs and/or education relevant to their assessed needs.

To do this, we considered the results of these prisoners’ risk assessments and matched them to the programs and/or education they completed or were referred to. When assessing completed programs and education rates, we did not include assessments, appointments or orientation sessions.

Based on the files we reviewed, we found that:

- Short-stay prisoners (serving less than three months) did not engage in criminogenic programs to address offending behaviour. This is because, as mentioned earlier, short-stay prisoners are ineligible for Ravenhall’s criminogenic programs. We found that these prisoners did participate in other rehabilitation, reintegration and transitional services.

- Prisoners serving sentences between three to five months were more likely to complete lifestyle and personal development programs.

- Longer-stay prisoners were more likely to complete clinical programs that addressed offending behaviour and AOD programs.

- Mid and longer-stay prisoners were more likely to complete programs and education aligned with the risk areas identified during their reception.

Further details about our file review can be found in Appendix B.

Program evaluation

Each Ravenhall program has a program logic that outlines short and medium term outcomes. GEO measures these outcomes through a combination of:

- pre and post-program psychometric assessments or surveys to measure changes in participants’ behaviours, attitudes and thoughts

- participant feedback forms

- clinician feedback.

To date, Ravenhall has used this feedback to complete four evaluations for the following programs:

- Know the Score (AOD)

- Skating on Ice (AOD)

- Prison-related Harm Reduction (orientation)

- Release-related Harm Reduction (release preparation).

Ravenhall’s evaluations show that its harm reduction programs are largely meeting their objectives. Participants have reported an increased awareness of available support avenues and of the harms associated with substance use. For the AOD programs, Ravenhall reported:

- improved scores for self-esteem and decision-making and for reduced depression, anxiety and hostility

- improved awareness of the effects of substance use, and the ability to identify triggers and manage triggers and cravings

- improved confidence to abstain from using drugs and alcohol

- small increases in motivation to change, however, these were not statistically significant (potentially due to a small sample size).

GEO has identified strategies to reduce prisoners’ risk of substance harm after their release as an area of improvement for its release-related harm reduction program.

To date, GEO has only evaluated Ravenhall’s AOD programs. Sample size permitting, it would be useful for GEO to consider evaluating its other types of programs, including its criminogenic, treatment readiness or complementary programs.

Ravenhall does not evaluate the lifestyle programs that its Alliance Partners deliver, or any of CV’s OBPs.

2.4 Post-release services

Ravenhall’s post-release model has some unique features. In particular, the Bridge Centre, where prisoners can access the same GEO staff they engaged with in prison after they are released.

Ravenhall’s post-release model was designed to address its sentenced prisoners’ needs. Due to the contract changes, GEO was not initially funded to offer intensive pre and post-release case management services to its remand and short-stay prisoners. CV approved GEO’s proposal to fund these services in December 2019.

GEO uses several assessments to identify its prisoners’ post-release risks and needs. Our file review of 20 prisoners showed that GEO completed eight reintegration assessments outside of the required time frames and, in some instances, its reintegration plans were vague. Application consistency and complete records are necessary if, in future, CV or GEO undertake a causal evaluation.

Are post-release services targeted to prisoners’ needs?

Are prisoners’ needs assessed prior to their release?

GEO’s formal points for assessing Ravenhall prisoners’ post-release needs include the Reception Transition Triage (RTT), its reintegration assessment and the IRP.

Reception Transition Triage

The RTT is a common assessment tool used across the public and private prison system. It identifies the immediate transitional needs of sentenced and remand prisoners. Our file review found that all 20 prisoners had completed an RTT. Of these, 19 were completed on the day of, or day following, their reception at Ravenhall. The remaining prisoner’s RTT commenced on the day of their reception and was completed four days later.

The Ravenhall RTT has an additional section to the version used in public prisons. This section determines if prisoners have high reintegration needs relating to housing, social support, employment, education, AOD and/or disability. Based on the assessment, GEO’s Gateway system automatically refers prisoners to the relevant Alliance Partner for support.

Reintegration assessment

The reintegration assessment is designed to identify a prisoner’s reintegration needs and refer them to the appropriate services and programs. GEO reintegration officers administer the assessment for remand prisoners within 14 days of their reception, and within four weeks for sentenced prisoners.

This assessment collects the same type of information as CV’s reintegration assessment. However, it has additional questions and triggers automatic referrals to Ravenhall-specific programs and services. In our file review we found that:

- 17 prisoners had a reintegration assessment completed.

- Two prisoners had no record of the assessment in Gateway—one had refused to participate and the other was discharged before it was completed.

- One prisoner was assessed by his clinician as unable to participate due to a mental health condition and was therefore exempt.

A prisoner’s participation in this assessment depends on their consent and willingness to engage with reintegration services. If the reintegration assessment is completed late into a prisoner’s stay, then they may not be referred to the appropriate programs or services in time. Alternatively, they might not have enough time to complete the programs and services when they are eventually referred.

Of the 17 prisoners that had a completed reintegration assessment, eight did not have them completed within GEO’s set time frame. For these eight, the time for completion ranged between 4.5 to 66 weeks after their reception. Two of the prisoners who had reintegration assessments completed outside of the required time frame (including the prisoner whose plan took 66 weeks to complete) had initially refused to participate, but later consented due to continued engagement by GEO staff.

Individual Reintegration Plan

An IRP is used to identify a prisoner’s post-release goals, refer them to Alliance Partners’ reintegration services and determine if they are suitable to be included in KPI 15. The prisoner develops their IRP with the support of a GEO reintegration officer.

CV monitors GEO to ensure that all eligible prisoners have an IRP and that the required referrals to Alliance Partner services are made through KPI 24 (reintegration assessment and referral). Ravenhall has achieved 100 per cent for this KPI since opening, and we identified no issues with CV’s validation of KPI 24 results.

In our file review, the 15 prisoners who required an IRP had one. Of the remaining five, four were valid exceptions because they were remand prisoners discharged from court, and one was exempt for mental health reasons.

We also considered the quality of the IRPs. Of the 15 that were completed, we assessed 10 as sufficiently individualised and targeted to the risks and needs of the prisoner. The remaining five did have some relevant information for the prisoner but were overall vague and generic.

While CV does not have a formal quality assurance process for IRPs, GEO states that it has recently implemented one. This includes observing IRP development sessions between a prisoner and their case manager, and a formal review of all IRPs by a senior member of Ravenhall’s Transition and Reintegration team.

Are post-release services targeted to the needs of Ravenhall’s expected cohorts?

Ravenhall’s post-release services are designed around five key reintegration domains (housing, education, employment, mental health and AOD) and the individual needs of its prisoners. GEO refers prisoners to these services based on the risk assessments outlined above.

Post-release services for remand and short-stay prisoners

Due to contract change 7, half of Ravenhall’s prisoner population did not have access to intensive reintegration and post-release services.

GEO and CV proceeded with contract change 7 on the understanding that the Continuum of Care model would be provided to all prisoners, regardless of their legal status. They also agreed that all changes would be cost neutral to the state. GEO and CV later agreed that funding intensive remand and shortstay reintegration services was beyond the scope of the contract changes.

Until December 2019, Ravenhall was the only prison in Victoria that did not provide intensive pre and post-release case management services to remand prisoners. This is because other prisons receive funding for the ‘Restart’ program, which is used in the public system. This created a gap where Ravenhall prisoners were at a comparative disadvantage.

Despite this, Ravenhall’s remand prisoners have always had the same ability to access the Bridge Centre as sentenced prisoners.

In February 2019, the state formally requested GEO to submit a proposal for intensive post-release remand services. GEO submitted a proposal in March 2019 and, after refinement, this was approved in December 2019. The approved proposal is for a three-year period and is comparable to the public system. It includes the provision of intensive pre and post-release services to 225 remand and short-stay prisoners each year.

Once the service model has been finalised, CV and GEO have committed to develop new KPIs to measure Ravenhall’s remand reintegration services. Additional KPIs are appropriate if remand prisoners are excluded from KPIs 15 and 24. CV is considering if payments for a new remand prisoner KPI should be additional to the current pool of KPI payments or incorporated within the existing pool.

Funded Individual Support Packages

Ravenhall offers a fixed number of Funded Individual Support Packages (FISP) to support offenders who present with high reintegration needs to transition back into the community. Two of the FISPs are targeted towards specific cohorts—youth and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders.

Figure 2H

FISPs

|

Type of FISP |

Alliance Partner |

Description |

|---|---|---|

|

Housing |

MCM |

Provides either three-or six month’s rental subsidy for suitable prisoners so they can focus on employment. |

|

Bridge Employment |

YMCA |

Provides intensive case management and employment support for young people (25 years and under). |

|

Aboriginal post release coordination linkages |

A suitable Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation |

Provides culturally appropriate post release support. |

Source: VAGO, based on GEO’s operating instruction.

Between January 2018 and October 2019, GEO awarded 193 FISPs. Of these, 149 were for housing and 44 were for Bridge Employment. No FISPs have been awarded in the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stream due to challenges in finding suitable service providers. Instead, GEO reported that FISP funding has been used to support the delivery of post-release services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander men through alternate means.

Unique to Ravenhall, FISPs are designed for sentenced prisoners who spend a sufficient amount of time at the prison and demonstrate a willingness to engage with its services. GEO has stated that it requires approximately three months to assess a prisoner’s suitability for a FISP and undertake pre-release case management and planning.

GEO’s length of stay data for prisoners discharged between January 2019 to December 2019 shows that only 20 per cent of discharged prisoners were sentenced and served for three months or longer. Based on length of stay alone, only a small number of prisoners could have benefited from a FISP.

GEO has stated that it reallocated some of its FISP funding to custodial services due to contract change 7.

The Bridge Centre

The Bridge Centre is an administrative hub, program delivery venue and base where Ravenhall Alliance Partners and GEO reintegration staff provide post release services to former prisoners.

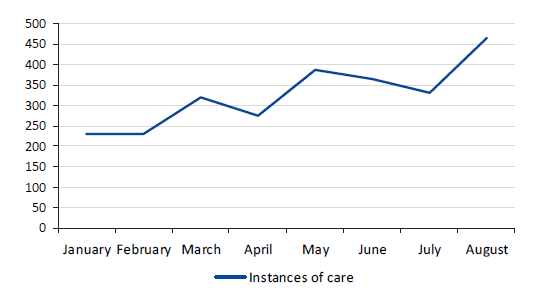

Any Ravenhall prisoner (remand or sentenced) can access services at the Bridge Centre for two years after their release. The centre gives former prisoners access to the staff and clinicians they engaged with at Ravenhall. Figure 2I shows that use of the Bridge Centre is increasing over time, as expected for a new prison and facility.

Figure 2I

Instances of care at the Bridge Centre, 2019

Note: Instances of care include appointments, phone support and unscheduled client drop-ins.

Source: VAGO, based on GEO data.

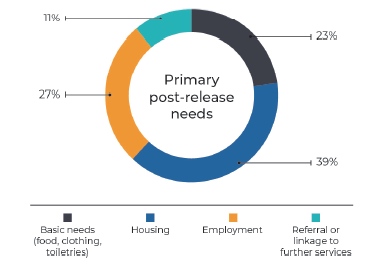

Figure 2J shows the breakdown of services that former prisoners access at the Bridge Centre.

Figure 2J

Primary post-release needs delivered at the Bridge Centre between January 2019–August 2019

Source: VAGO, based on GEO data.

2.5 Comparison to the public system

We compared GEO’s Continuum of Care model to the public model, which is known as Corrections Victoria Reintegration Pathway (CVRP). Overall, we found that the Ravenhall and CVRP models are aligned and use the same underlying principles. This is appropriate because it ensures that all of Victoria’s prisons are integrated and operate as one system.

The differences between the Ravenhall and the CVRP models are most evident in Ravenhall’s post-release services. While both models have the same purpose—to offer reintegration services to offenders with complex needs, Ravenhall’s post-release model has many unique features:

- Continuity of care—post release, former prisoners have access to the same clinicians and staff they engaged with during their custody at Ravenhall. Where a staff member is not physically present at the Bridge Centre, meetings can be arranged through the Bridge Centre’s teleconference facilities.

- FISPs—while the public system has similar support services, they are set up differently to FISPs. FISPs compliment the current public offering by providing funded packages to offenders who are motivated and willing to engage.

- Family involvement—GEO offers individual family support as well as family information nights at the Bridge Centre. Anecdotally, GEO staff have reported that this increases former prisoners’ engagement with post release services.

Compared to the public system, two weaknesses of Ravenhall’s model are the Bridge Centre’s fixed location and that it offers less assertive outreach.

1. The Bridge Centre’s fixed location

CV requested that the Bridge Centre be in a central Melbourne location. As the Bridge Centre is in a fixed location, this may not be convenient or accessible for all former prisoners. Comparatively, the public post-release service network, which has more clients, is located across metropolitan and regional Victoria.

To address the distance barrier, the Bridge Centre can provide post-release support via phone. GEO reported that it has occasionally used regional CV offices to facilitate video or teleconferences with regionally based former prisoners. GEO’s Alliance Partner MCM provides some assertive outreach services throughout Victoria.

In the public system, former prisoners are placed with a service provider in their geographic region.

2. Less assertive outreach

Assertive outreach is where case managers proactively and persistently attempt to engage offenders who have high reintegration needs and are not engaging or are having difficulty engaging with services.

Ravenhall’s Alliance Partner MCM provides assertive outreach to some former prisoners through its Emerge Program. This program provides former prisoners with funding for housing, education and employment for up to six months after their release. CV’s equivalent program offers support for up to 12 months.

Other forms of case management at Ravenhall do not include assertive outreach.

3 Monitoring and evaluating Ravenhall’s performance

Ravenhall is the first Australian prison to have key performance measures and payments linked to its reintegration and reoffending outcomes. If successful, this approach could be applied more broadly throughout Victoria’s private prison system.

In this Part, we assess if CV and GEO have designed appropriate performance monitoring and evaluation frameworks that can attribute outcomes to Ravenhall’s unique programs and interventions. We also consider GEO’s early performance outcomes.

3.1 Conclusion

While both KPIs were well-intentioned, they have design limitations that impair their ability to definitively measure Ravenhall’s reintegration and reoffending outcomes.

KPI 15 measures prisoners’ outcomes following their engagement in post release reintegration services. It is not working as intended and has proven difficult for GEO to design and implement.

KPI 16 is not a valid or useful measure to determine performance payments for recidivism outcomes because it does not measure Ravenhall’s impact on reintegration or reoffending. It does not determine if reoffending outcomes are linked to GEO’s interventions at Ravenhall or if they should be attributed to other factors, particularly where prisoners released from Ravenhall have spent time at other prison facilities.

CV has no evaluation or research projects planned to explore the relationship between Ravenhall and its reoffending outcomes. This means that if Ravenhall is successful and has a lower rate of recidivism than other prisons, CV does not have a method to determine if it was Ravenhall’s programs and interventions that caused it.

3.2 Performance indicators

GEO will receive performance payments of up to $1 million per year for achieving each of its KPI 15 and 16 targets. This collective $2 million is a small percentage of the overall service payment available to GEO. While KPIs 15 and 16 measure outcomes, several of GEO’s other performance measures also directly relate to rehabilitation and reintegration services.

KPIs 15 and 16 are stretch targets, which means that they were designed to be challenging to achieve. Like any KPI, they need to be practical, clearly defined, understood and, given the contractual arrangement, agreed to by both parties.

It is important to measure and monitor rehabilitation and reintegration outcomes. However, CV’s financially incentivised KPI 16 is not the best mechanism to do this because it does not solely describe the impact of GEO’s interventions at Ravenhall.