Rehabilitating Mines

Snapshot

Is the state effectively managing its exposure to liabilities from the rehabilitation of mines on private and public land?

Why this audit is important

Since Victoria’s gold rush in the 1850s, the state’s mining and quarry industries have boosted our economy. They help deliver electricity, underpin building and construction, create jobs, and attract investments for the state.

Mining and quarrying can also cause environmental damage. Recognising this, the Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990 (the Act) aims to achieve a balance. It encourages mineral exploration and operations, while ensuring risks to the environment and community are identified and eliminated or minimised.

Site rehabilitation is a key part of minimising risks to the public, the environment, property or infrastructure. Rehabilitation aims to make mine and quarry sites safe, stable and sustainable. Mine and quarry operators are responsible for rehabilitation works, with the anticipated cost secured by a bond. However, if the operator defaults on their rehabilitation responsibilities, the cost to restore the land may fall on the state.

What and who we examined

The Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR) regulates mining rehabilitation through its Earth Resources Regulation (ERR) unit. This audit examined whether its work minimises the state’s exposure to rehabilitation liabilities. We also examined how DJPR and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP) identify and manage rehabilitation liabilities from abandoned and legacy sites.

We also considered DJPR’s coordination with relevant agencies, including DELWP, the Environment Protection Authority Victoria (EPA), the Latrobe Valley Mine Rehabilitation Commissioner (LVMRC) and the Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority (GBCMA).

What we concluded

DJPR is not effectively regulating operators’ compliance with their rehabilitation responsibilities. This exposes the state to significant financial risk because some sites have been poorly rehabilitated or not treated at all. If not addressed, these sites also present risks to Victorians and the environment.

Systemic regulatory failures encompass:

- using outdated cost estimates

- not periodically reviewing bonds for their sufficiency—including a four-year bond review ‘moratorium’ for which there is no documentary evidence that it was duly authorised

- failure to assure that site rehabilitation had actually occurred before returning bonds

- approving inadequately specified rehabilitation plans

- lack of enforcement activities.

Further, while some changes to address conflicts of interest were made following Parliament’s Independent Inquiry into the EPA in 2016, ERR—the primary mining regulator—still resides within DJPR, which seeks to foster and develop the mining industry.

ERR acknowledges that it has not effectively discharged its responsibilities and is working to rectify identified issues. Following the recommendations of the 2014 and 2016 inquiries into the Hazelwood mine fire, ERR began improving its regulatory performance. However, its early reforms were broad, and it was not until mid-2018 that ERR started specifically addressing rehabilitation issues.

Video presentation

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

Rehabilitation liabilities

Rehabilitation bonds held by the state

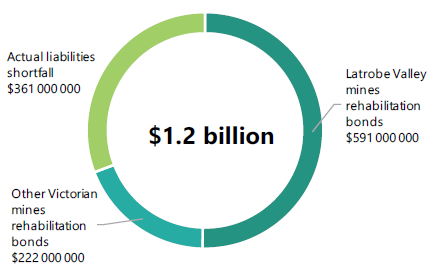

ERR holds $813 million in rehabilitation bonds. This comprises:

- $591 million (73 per cent) for the three coal mines in the Latrobe Valley—the largest mines in Victoria

- $222 million (27 per cent) for the other 1 391 mines and quarries across the state.

ERR acknowledges that bonds for many Victorian mines and quarries do not cover actual rehabilitation costs.

To scope and plan future regulatory actions, ERR did a preliminary assessment of how much it would cost to rehabilitate Victoria’s mines and quarries. It found that the $813 million figure may be $361 million short. ERR advised that this is an estimate only and that it will conduct further reviews to more accurately determine total rehabilitation costs.

It is likely that $361 million is a low estimate because the assessment was done largely as a desktop analysis. It automatically applied:

- $10 000 as the estimated restoration cost for over 500 mines and quarries that currently have less than $10 000 in rehabilitation bonds

- a modest 10 per cent increase in restoration costs for over 800 sites that currently have at least $10 000 in rehabilitation bonds.

Low-value rehabilitation bonds

According to available ERR data, there are 1 394 mines and quarries across the state that should have rehabilitation bonds.

Nearly 89 per cent of these, or 1 239, have rehabilitation bonds of less than $200 000. For 526 of these (covered by mining licences and work authorities), the bond value is $10 000 or less.

This is not sufficient to cover rehabilitation costs.

ERR’s 2010 Establishment and Management of Rehabilitation Bonds for the Mining and Extractive Industries (Bond Policy) requires a standard bond rate of $4 000 per hectare for small and low-risk quarries. These are defined as less than five hectares in area, less than five metres in depth, and not requiring blasting or native vegetation clearance.

However, we identified 275 mining licences and work authorities—whose operations do not meet the definition of ‘small and low risk’—with bond amounts below the $4 000 per hectare rate. These include 100-hectare gold mines.

ERR contests this comparison and maintains that for sites larger than five hectares, the $4 000 per hectare rate should only be applied to the disturbed area and not the entire licence area. However, applying the $4 000 per hectare rate on the disturbed area—instead of the whole site—still reveals significant shortfalls.

Rehabilitation bonds are meant to ensure that the state has funds to restore sites if operators do not. The fact that many sites have bonds that are less than what is deemed sufficient means that the state is potentially exposed to significant financial risk.

Lack of rehabilitation bonds

According to available ERR data, 578 mining and quarry sites have no rehabilitation bonds.

Within this group, we were able to identify 24 sites that are actively operating and 14 inactive sites that are no longer operating but are yet to be rehabilitated. This means that ERR has breached its regulatory responsibilities, because the Act requires mines and quarries to have rehabilitation bonds before:

- obtaining their quarry work authorities

- beginning ground operations for mines.

For the remaining 540 sites, ERR said that reasons for the lack of a bond include:

- that the bond had been returned to the operator at completion of rehabilitation

- the sites are not yet operating.

However, ERR was unable to provide documentation to show this. ERR acknowledged that its limited record keeping and information management systems contribute to its inability to confirm why there are no recorded bonds for these sites.

The state’s contingent liability

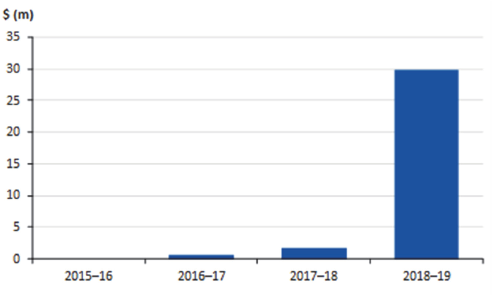

Contingent liability (CL) is the cost the state could become responsible for if operators fail to rehabilitate their mine or quarry sites. DJPR reported in its 2018–19 Annual Report that this stood at $29.8 million as at 30 June 2019.

This is significantly higher than the $1.7 million CL reported as at 30 June 2018 in the then Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources' (DEDJTR) 2017–18 Annual Report. The difference is not due to increased risks, but to ERR’s earlier lack of rigour in determining the state’s position.

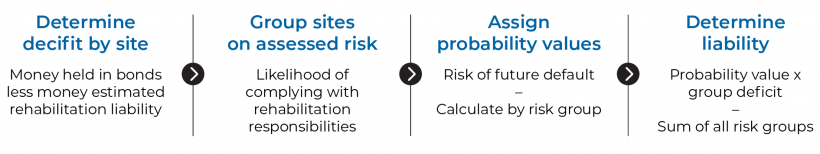

ERR’s 2019 Rehabilitation Bond Review Operational Policy informed its determination of the state’s mining rehabilitation CL for 2018–19. In estimating the $29.8 million CL, ERR considered the:

- difference between current rehabilitation bond value and estimated actual rehabilitation liability (the preliminary assessment referred to earlier)

- the likelihood of an operator defaulting on their rehabilitation obligations (financial standing and resource depletion), and

- the consequences of an operator defaulting.

ERR is working to further refine its assessment of the state’s potential mining liabilities. In November 2019, it advised us that the state’s CL could be $50 million for all Victorian earth resources sites.

It is expected that DJPR will again report on the state’s mining CL in its 2019–20 annual report.

Regulating rehabilitation bonds

ERR’s ineffective regulation of rehabilitation bonds means that the state is financially exposed to significant costs.

Setting the rehabilitation bond amount

ERR has not effectively calculated and set rehabilitation bonds to cover the full cost of rehabilitating mines and quarries.

ERR last updated its rehabilitation bond calculator in September 2010. Therefore, its input rates do not reflect the 19.8 per cent increase in the consumer price index from 2010 until 2019.

ERR’s calculator also does not account for factors that affect rehabilitation costs such as:

- site remoteness

- potential resources required for rehabilitation, such as water

- operations in areas of high environmental sensitivity.

ERR is aware of these issues and advised it is on track to release an updated bond calculator by December 2020. However, due to the economic uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, ERR postponed its March 2020 stakeholder consultations on the revisions to the bond calculator.

Process for returning rehabilitation bonds

ERR cannot demonstrate that it ensures a mine or quarry site has been rehabilitated before returning the bond to the operator. This includes ensuring that the state has no remaining liability.

Inconsistent application of ERR’s bond return process, and limitations in its record keeping, mean that ERR is unable to provide assurance that it undertakes assessments to ensure satisfactory rehabilitation in all cases. While we sighted some field entry reports evidencing site inspections, these vary in detail and do not include all the required rehabilitation information.

This means that even though ERR complies with the requirement to consult with the landowner, council and the Crown land manager, where appropriate, it cannot assure that these sites have been rehabilitated as required, and that the state therefore has no remaining liability.

ERR advised that it is developing an updated version of the bond return process to align with its assignment of staff responsibilities for site rehabilitation and other process improvements.

Conducting bond reviews

ERR conducted bond reviews for the Latrobe Valley coal mines following the findings of the 2016 Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry Report Volume IV—Mine Rehabilitation. However, it has not reviewed most rehabilitation bonds for Victoria’s mines and quarries in accordance with the Bond Policy.

The Bond Policy requires ERR to periodically review all rehabilitation bonds to ensure that the financial security remains at an appropriate level. The Bond Policy’s recommended frequency for bond reviews is set out in Figure 1G.

Available data shows that:

- ERR is on track with its review of 8.3 per cent of rehabilitation bonds

- 91.7 per cent are not on track, of which:

- 68.6 per cent are overdue for review, by up to 23 years (and nine years on average).

- 23.1 per cent do not have a scheduled next review. ERR records suggest that nearly half of these have not been reviewed since their licences and work authorities were first granted between 1988 and 2015.

This failing means ERR cannot assure that bond values reflect what it would cost to undertake rehabilitation if an operator defaults.

Bond review moratorium

ERR acknowledges that a bond review moratorium was in place from 2013 to 2017, but cannot provide documentary evidence about its:

- approval in 2013

- announcement to ERR staff and stakeholders

- guidance to staff on its implementation

- termination in 2017.

A moratorium is an allowed period of time to suspend the performance of a task or obligation.

A moratorium is not consistent with the Bond Policy’s requirement that ERR periodically review rehabilitation bonds.

The lack of documentation to demonstrate when, why and by whom the moratorium was approved and later lifted, breaches the principles of transparency and accountability. Clear documentation of the rationale and approval process is important, as the decision clearly benefited mine and quarry operators, potentially to the detriment of the environmental protections that are intended by the Act and the Bond Policy.

Conflict of interest

The 2016 parliamentary Independent Inquiry into the EPA raised concerns about the conflict of interest in having ERR—the primary mining regulator—as a unit within DJPR, the department responsible for fostering and developing the mining industry. It noted that ERR had not regulated the environmental and public health risks associated with mining operations to the same level as other industries with similar environmental risk profiles.

To address these concerns, the inquiry recommended that EPA play a greater role in mining regulation. The government supported this in principle and amended the Act to provide for the mandatory referral of mining work plan applications to EPA from 1 July 2019.

However, EPA’s additional role to review work plans is unlikely to be sufficient to address the conflict of interest. This is because most of the regulatory responsibilities continue to lie solely with ERR, particularly the compliance and enforcement of environmental conditions.

Regulating rehabilitation

ERR’s regulation of mining rehabilitation does not meet its responsibilities under the Act, relevant regulations and policies. Until regulation is effective, ERR will not be able to:

- incentivise operators’ compliance with their rehabilitation responsibilities

- limit the government’s exposure to rehabilitation liabilities.

One consequence of ERR’s failure to monitor operators’ compliance with their rehabilitation responsibilities is that some mining licences become inactive before rehabilitation works are finished or even begun.

This increases the risk of the state needing to take on a rehabilitation liability due to a mining operator not acting as required by the Act.

Rehabilitation plans

A rehabilitation plan documents potential risks to the environment and public safety, and how these risks could be minimised through progressive and final rehabilitation.

Comprehensive and unambiguous rehabilitation plans are therefore the first step to effective rehabilitation. However, the rehabilitation plans we reviewed were not written with sufficient detail.

ERR generally complies with requirements to consult with the landowner, council, local community, catchment management authorities and Crown land managers, where appropriate, when assessing work plans and their associated rehabilitation plans. However, of the 18 plans we reviewed, 13 (72 per cent) do not have the detail required by the Act, Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) (Mineral Industries) Regulations 2019 (MRSDMIR) and Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) (Extractive Industries) Regulations 2019 (MRSDEIR). Statistically, this indicates that it is highly likely that more than half of all approved rehabilitation plans are non compliant.

If ERR continues to approve rehabilitation plans that do not meet the requirements of the Act and regulations, then the associated rehabilitation bonds will not cover the true cost of rehabilitation.

|

Of the 18 rehabilitation plans reviewed ... |

Meaning ... |

|

Four have rehabilitation plans that are vague and do not have the required information. For example, one plan references itself: ‘Rehabilitation Plan: Progressive and final rehabilitation must be undertaken in accordance with the approved rehabilitation plan and any additional requirements as and when directed by the Inspector’. This is the entire rehabilitation plan. |

Neither the operators nor ERR has a clear understanding of the cost required to complete rehabilitation. This makes it difficult to set effective rehabilitation bonds. |

|

Nine have some, but not all of the required information. |

These plans provide high-level information and are unclear on important aspects of the rehabilitation plan, such as how progressive rehabilitation will be carried out and what final landform is proposed. |

|

Five have all the details required by the Act and the regulations. |

28 per cent of our sample is fully compliant. |

DELWP also noted that ERR has not always strictly enforced the rehabilitation plan requirements of the Act, MRSDMIR and MRSDEIR.

Consequently, DELWP, which manages Crown land, advised us that it has often been left with unrehabilitated or poorly rehabilitated mine and quarry sites.

Monitoring rehabilitation

ERR is unable to provide evidence of the extent to which operators comply with their rehabilitation obligations. This is because its monitoring program has not prioritised determining whether operators are:

- progressively rehabilitating mining sites during operations, or

- completing rehabilitation after operations.

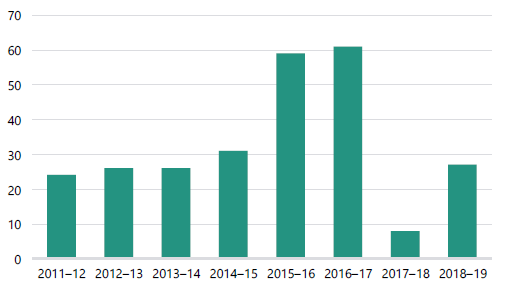

While ERR’s annual statistical reports say that it conducts inspections and audits every year, less than 10 per cent of these check operators’ rehabilitation activities. Moreover, ERR's rehabilitation-specific checks have not been appropriately informed by risk considerations.

Annual reporting of rehabilitation information

Mining operators submit annual expenditure and activities return reports to ERR. However, while ERR checks whether operators submit these, it does not assess whether the responses are complete or reasonable. ERR advised us that this is because it does not have the resources to do so.

This is a missed opportunity, because the information provided in annual returns— rehabilitation works, expenditure and liabilities—could help ERR identify non-compliance with rehabilitation requirements. Information from annual returns could also better inform ERR’s rehabilitation risk rating of mines and quarries.

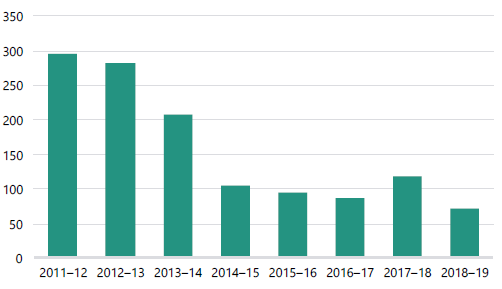

Enforcement

None of the 262 enforcement notices that ERR issued from 2011–12 to 2018–19 relate to operators’ breaches of their rehabilitation responsibilities.

Since 2016, ERR has begun court proceedings against five mine and quarry operators for breaches of the Act and regulations. However, it has not prosecuted any rehabilitation-specific breach or non-compliance.

Outcomes of poor rehabilitation regulation

Without effective monitoring, mining licences and work authorities may become inactive with rehabilitation works not having been completed or even started.

This increases the state’s risk of absorbing rehabilitation liabilities, which the Act requires mine and quarry operators to bear.

Inactive mines and quarries

ERR categorises licences and work authorities as either ‘Active’ (current, not expired, not suspended, ongoing), ‘Inactive’ (expired, suspended, surrendered, not renewed but not yet rehabilitated), and ‘Fully released/Called in’ (final rehabilitation completed and bond is returned, or not rehabilitated and the bond was called in).

As at 30 September 2019, available ERR data suggests that there were 231 inactive mines and quarries across the state. These are unrehabilitated sites that are no longer operating but still have an operator on record.

ERR does not have processes to effectively guide staff on how to regulate inactive mines and quarries. This results in sites remaining ‘inactive’ for an indeterminate amount of time with little or no rehabilitation taking place.

ERR advised us that while these 231 inactive sites are within its scope of regulation, it does not have adequate resources to inspect them and compel rehabilitation. Its inspectors’ workloads are taken up with overseeing active sites.

Abandoned mines and legacy mines and quarries

The 2019 Australian Senate Inquiry into the Rehabilitation of Mining and Resources Projects said that there are an estimated 19 000 locations across the state where evidence of previous mining or quarrying activities, such as a mine shaft, have been identified. DELWP advised us that the actual number is significantly higher.

ERR classifies vacated, unrehabilitated sites—where the responsibility for rehabilitation can no longer be allocated to any individual or company—as either legacy or abandoned based on when mining operations ceased. Those that stopped mining activities after the Act came into effect in 1990 are classified as abandoned. Those that stopped before 1990 are legacy.

ERR is unable to advise us on the number of abandoned sites. DELWP also does not have reliable and comprehensive records on legacy and abandoned sites on Victorian Crown land.

There is no statewide approach to managing abandoned and legacy sites to reduce their environmental, public health and safety risks.

As a result, there has been an ad hoc, uncoordinated and reactive approach to managing abandoned and legacy sites across the state.

To address this issue, DELWP and DJPR advised us that:

- DELWP is responsible for legacy mines and quarries on Crown land.

- The Minister for Resources may take action to rehabilitate land if they are not satisfied that rehabilitation has been appropriately undertaken and the licence holder or former licence holder has failed to do so in a reasonable time.

- Going forward, DJPR, in partnership with DELWP, will typically lead rehabilitation works on abandoned sites on Crown land.

- DELWP would not immediately take on responsibility for all abandoned mines and quarries on Crown land as there may be bonds or other consolidated funds available to DJPR to rehabilitate the site.

DELWP and ERR are working on a joint departmental statement regarding their shared position on managing legacy and abandoned sites on Crown land. They advised that this statement will be published by 31 December 2020.

Better-practice management of abandoned and legacy mines

Victoria is not as well placed as other jurisdictions to manage the risks from abandoned and legacy mines. DELWP and DJPR acknowledge that the state does not have the following components of better practice found in other jurisdictions:

- abandoned and legacy mines and quarries policy

- risk assessment matrix and risk register

- established database for abandoned and legacy sites

- dedicated funding for rehabilitation

- designated responsible agency branch or unit.

No comprehensive record on rehabilitation works and costs

Other than for rehabilitation of the Benambra mine in East Gippsland at the cost of $5.6 million as at November 2019, ERR is unable to provide information about other instances when the state rehabilitated mines or quarry sites under the Act.

When we requested this information, ERR provided a list of 19 mines and quarries whose bonds were allegedly called in to finance the sites’ rehabilitation. However, the list does not include information on whether rehabilitation was completed or even begun. Moreover, ERR’s rehabilitation bonds data shows that it has in fact not called in any of these bonds.

ERR acknowledges that it has not prosecuted any licence holder to enforce rehabilitation or to recoup additional costs of rehabilitation incurred by the state.

Also, DELWP does not centrally record rehabilitation work conducted by its regional offices, or the corresponding expenditure. We found that DELWP regional offices record this information in varying level of detail.

DELWP action on legacy mines and quarries

DELWP has no centralised approach to manage legacy sites on Crown land. This means that regional offices’ management of legacy sites is reactive, uncoordinated and not uniform.

However, DELWP actively manages known legacy sites with immediate risks to the environment or public safety. DELWP advised us that its officers come across legacy sites in the course of other work, such as managing bushfire risks, implementing weed and pest programs or providing recreational services. In these cases, if the site poses a risk to human health and the environment, DELWP officers work to manage the risks through methods such as fencing, backfilling, capping or grate installation.

DELWP’s new approach to managing contaminated land

DELWP advised us that it is developing a new approach to better manage risks associated with contaminated land, including abandoned or legacy sites.

This work is in response to the introduction of the Environment Protection Act 2017 (as amended), which imposes a duty on DELWP, as Crown land manager, to manage contaminated land and minimise risks to human health and the environment as far as reasonably practicable.

Regulator readiness

ERR acknowledges the need to improve the regulation of mining rehabilitation and is working to rectify identified issues.

ERR’s policies and guidance documents do not support its effective regulation of rehabilitation liabilities as required by the Act. They do not enable ERR to effectively oversee the sector or set enforceable requirements to encourage mining operators to comply with their rehabilitation obligations.

Further, ERR has no integrated information management system. Where information is available, it holds it in fragmented systems. There is no easy way to collate or retrieve information to provide an auditable trail of rehabilitation compliance.

These factors have resulted in ineffective compliance and enforcement, leaving the state at risk of taking responsibility for poorly rehabilitated mining and quarrying sites.

Finally, despite recent changes to address it, the conflict of interest remains in having the primary mining regulator—ERR—reside within DJPR, which seeks to foster and develop the mining industry.

Policies and procedures

While ERR has a number of policies and guidance documents to manage rehabilitation liabilities, these are fragmented, often outdated and inconsistently applied. They are also used infrequently, as staff are often unaware of them.

This has resulted in blurred accountabilities, inconsistent application across regions and weak oversight, which inhibits ERR from effectively implementing the Act’s requirements.

To address this, ERR developed standard operating procedures (SOP) to support consistent and compliant regulatory practices. However, other than the 2019 Rehabilitation Bond Review Operational Policy and the 2020 Preparation of Rehabilitation Plans: Guideline for Mining and Prospecting Projects, ERR’s SOPs do not provide sufficient guidance on managing rehabilitation responsibilities.

None of the completed policies and procedures provide guidance on how to:

- set and review rehabilitation bonds

- monitor and enforce progressive rehabilitation

- assess compliance with final rehabilitation requirements.

ERR is continuing work on addressing the gaps in its operational policies and process documents. On 7 February 2020, the Minister for Resources approved ERR’s Regulatory Practice Strategy for the Rehabilitation of Earth Resources Sites.

This document outlines ERR’s rehabilitation responsibilities throughout the mine or quarry life cycle. It should help ERR better manage its mining rehabilitation regulatory responsibilities.

ERR resourcing

ERR advised us that lack of staff is a significant hurdle in performing its rehabilitation responsibilities. Only one staff member is responsible for rehabilitation liability assessments and ERR staffing has not increased despite its increased workload.

ERR belongs to DJPR's Resources Branch. In 2019, the branch commissioned a review of its workforce capabilities and capacity to inform future resource planning for its various units. The November 2019 report for this review noted that:

- ERR’s workload has sharply increased due to high demand for quarry materials and more mineral production. The increased workload has resulted in capacity issues in mining rehabilitation, regulatory compliance, investigations, assessments and risk management.

- The ratio of inspectors to sites and active issues does not allow for effective regulation and compliance, and the backlog of work is growing.

To determine its staff requirements, ERR’s Senior Management Committee conducted a workshop to consider current and anticipated future workload requirements. The workshop identified the need for additional 25.1 full-time equivalents (FTE) to address resourcing gaps in regulating rehabilitation.

Information management system

ERR has no centralised information management system for mining rehabilitation information.

Where information is available, it is held in fragmented and disparate systems across ERR offices. Other issues include:

- ERR’s electronic document management solution:

- is not compliant with the Public Records Act 1973, the Evidence Act 2008, Financial Management Act 1994, and the Electronic Transactions Act 2000, as identified in its 2017 internal audit

- is not fit for document retention and management, given the lack of validation controls, business continuity and disaster recovery planning

- inconsistent and siloed document management practices across the regions, as there is no ERR-wide SOP for document management and retention

- inadequate physical security for hard copy documents, leading to missing documentation and increased risk of information being fragmented, incomplete, inaccurate or out of date.

In December 2019, ERR approved a digitisation plan to make hard copy files available electronically and incorporate them in its electronic data management system.

In February 2020, ERR approved a project to develop its Resources Management System Victoria—a replacement for its current electronic data management system. ERR advised us that subject to funding availability, the project is scheduled for completion by 31 December 2021.

Roles and responsibilities across agencies and within ERR

Following ERR’s implementation of recommendations from the 2016 EPA Inquiry and the 2014 Hazelwood mine fire report, responsible agencies have a clearer understanding of their roles and responsibilities in the earth resources sector.

ERR’s 2019 Assignment of Rehabilitation Responsibilities clarified the roles and responsibilities of the various units in ERR.

However, ERR still needs to address issues with its memoranda of understanding (MoU) with DELWP and EPA, and its coordination with LVMRC and catchment management authorities.

MoUs with DELWP and EPA

Figure A lists the issues with ERR’s MoUs with DELWP and EPA.

FIGURE A: ERR’s MoUs with DELWP and EPA

| MoU | Issues |

|---|---|

| DELWP | The 2011 MoU between ERR and DELWP expired in 2016 and needs to be updated to reflect recent changes in legislation and regulations. The MoU is also silent on responsibilities including for:

|

| EPA | The 2018 MoU with EPA does not reflect the Act’s requirement to refer mining work plans to EPA, where a planning permit is required. ERR and EPA began implementing this on 1 July 2019, as required by the Act, and are now updating the MoU to incorporate the mandatory referral. |

Source : VAGO, based on ERR, DELWP and EPA documentation.

Latrobe Valley Mines Rehabilitation Commissioner

LVMRC advised us that the bond calculator for Latrobe Valley coal mines does not consider water-related and research costs, which are relevant for successful rehabilitation work.

LVMRC also noted that some site inspectors do not have the required technical capability to effectively inspect and assess sites.

ERR advised that it is working to enhance the technical skills of its inspectors. It has an in-house Technical Services team to support its inspectors’ compliance activities. The Technical Services team includes a mine engineer, a geotechnical engineer and hydrogeologist, as well as external technical specialists when needed.

Goulburn Broken Catchment Management Authority

ERR refers work plan applications to GBCMA when the proposed mining or quarrying site is covered by council planning schemes’ floodway zones or overlays.

There is no MoU between ERR and GBCMA, nor with other catchment management authorities.

GBCMA advised that while it believes that roles and responsibilities are clear, ERR procedures do not enable it to appropriately assess applicants’ preliminary work plans for their proposed mining and quarrying activities. For example, GBCMA believes that having access to preliminary plans before the onsite consultation meeting with the licence or work authority applicant would clarify potential environmental issues.

GBCMA noted that having this information at this stage of the process could assist the parties to better identify and discuss environmental concerns.

Quarries in GBCMA’s jurisdiction

DJPR has identified most of the floodplain of the Goulburn River as a source of gravel for Melbourne. GBCMA is concerned that sustained quarrying in the area will have significant environmental implications for the Goulburn River, and pose risk to people, land and infrastructure.

Pit capture occurs when streambank erosion, channel migration or overflowing floodwaters breach the natural buffer separating a mining pit from a river.

GBCMA advised us that pit capture is a genuine concern for the nine quarries in its jurisdiction. A July 2015 assessment commissioned by GBCMA revealed that the scale of quarrying operations and their close proximity to the Goulburn River and key infrastructure mean that significant physical and infrastructure impacts are highly likely to occur.

However, as at December 2019, ERR has only assessed two of these quarries—one as a high rehabilitation risk, and the other as medium. The rehabilitation bonds for these quarries, ranging from $8 000 to $511 000 do not reflect the significant rehabilitation risks that GBCMA has identified.

Remedial actions in progress

ERR is taking serious and considerable effort to address issues identified by various reviews to improve its oversight of its regulatory responsibilities.

Following the 2014 Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry, a 2015 internal audit commissioned by the then DEDJTR highlighted deficiencies in ERR’s regulatory practice and governance arrangements. These included:

- unclear governance arrangements

- inconsistent decision-making

- ineffective information management

- insufficient capability

- weak quality assurance.

DJPR accepted the report’s recommendations and ERR began a series of reforms, including a 2016 restructure which established a regulatory governance team within ERR.

Internal audits

An ERR-commissioned 2017 internal audit found that ERR had developed ‘fit-for-purpose processes and controls to oversee mine and quarry rehabilitation’.

Not satisfied with the findings of this audit, ERR commissioned another internal audit in 2018. The March 2019 report of this second internal audit found that:

- ERR did not have a policy framework to effectively manage its rehabilitation responsibilities.

- ERR's bond calculator and information management system are not fit for purpose.

ERR accepted the findings of the March 2019 report and committed to developing an implementation plan by September 2019.

Rehabilitation Improvement Project Plan

ERR’s September 2019 Rehabilitation Improvement Project Plan outlines actions to address key areas for improvement identified by the 2019 internal audit.

These initiatives are at various stages of implementation. Completed items include the finalisation of the 2020 Regulatory Practice Strategy for the Rehabilitation of Earth Resources Sites and the 2020 Preparation of Rehabilitation Plans: Guideline for Mining and Prospecting Projects.

However, the Rehabilitation Improvement Project Plan does not include action items to address:

- abandoned or inactive sites

- processes and procedures for addressing site closure or post-closure issues, including the return of rehabilitation bonds.

These matters are ERR’s responsibilities as the state’s primary mining regulator and need equal attention.

Recommendations

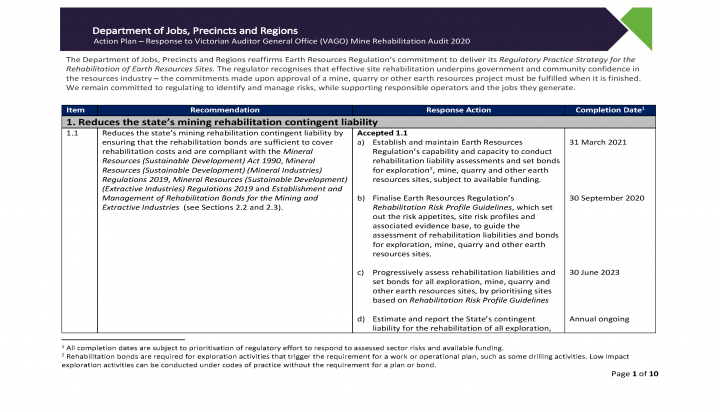

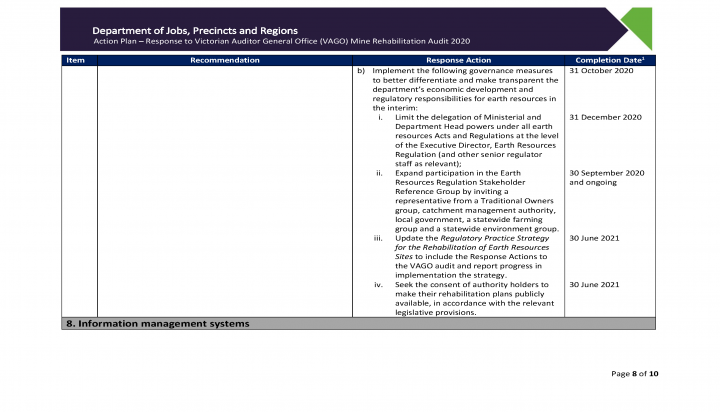

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

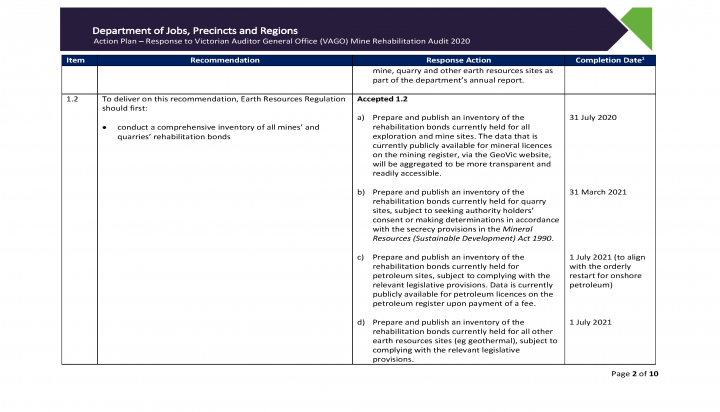

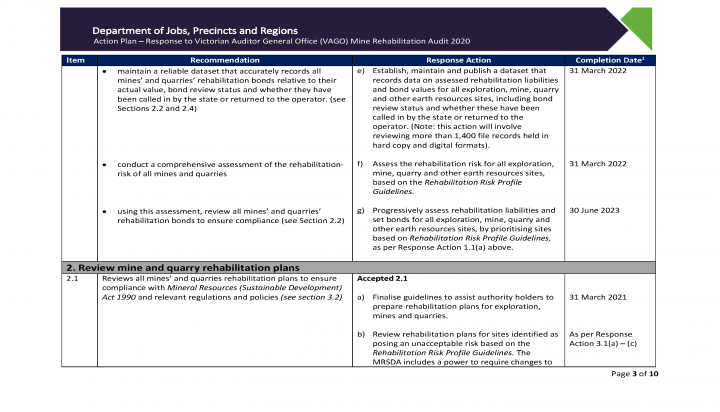

| The Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions | 1. reduces the state’s mining rehabilitation contingent liability by ensuring that the rehabilitation bonds are sufficient to cover rehabilitation costs and are compliant with the Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990, Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) (Mineral Industries) Regulations 2019, Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) (Extractive Industries) Regulations 2019 and Establishment and Management of Rehabilitation Bonds for the Mining and Extractive Industries (see Sections 2.2 and 2.3). To deliver on this recommendation, Earth Resources Regulation should first:

|

Accepted |

| 2. reviews all mines’ and quarries’ rehabilitation plans to ensure compliance with the Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990 and relevant regulations and policies (see Section 3.2) | Accepted | |

| 3.consults with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning, Environment Protection Authority and Latrobe Valley Mine Rehabilitation Commissioner’s successor agency on the definition of ‘unacceptable risk’ under the Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990 with a view to requiring operators of sites posing unacceptable risk to transition to risk-based work plans and rehabilitation plans (see Section 3.2) | Accepted | |

| 4.develops and implements a rehabilitation-specific inspection and monitoring program (see Section 3.3) | Accepted | |

5. develops and implements policy and guidance documents for:

|

Accepted | |

| 6. develops and implements an evaluation and reporting framework for its 2020 Regulatory Practice Strategy (see Section 4.2) | Accepted | |

| 7. provides advice to the Minister for Resources and the Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change on options to eliminate the conflict of interest that exists due to the location of the mining regulator, responsible for ensuring appropriate environmental controls, residing within the department responsible for supporting and developing the mining industry. This should include options to remove this regulatory function from within the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (see Section 2.5) | Accepted in principle | |

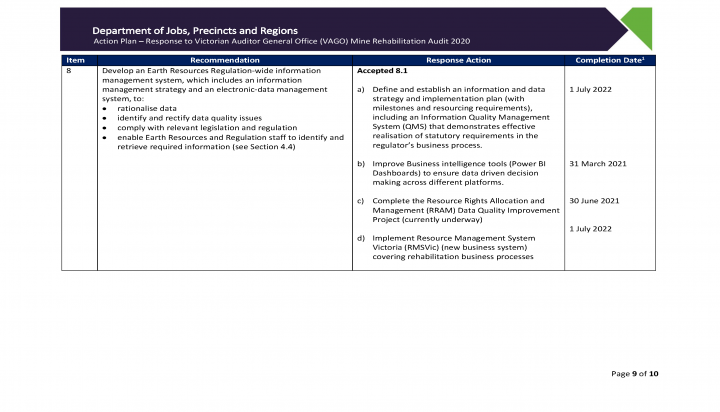

8.develops an Earth Resources Regulation-wide information management system, which includes an information management strategy and an electronic-data management system, to:

|

Accepted | |

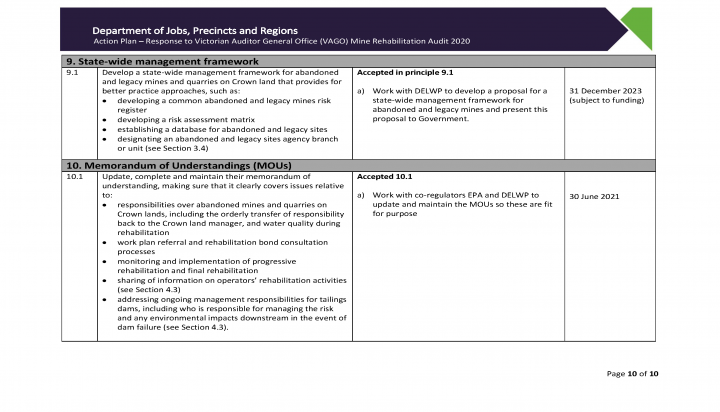

| The Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions and the Department of the Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

develop a state-wide management framework for abandoned and legacy mines and quarries on Crown land that provides for better-practice approaches, such as:

|

Accepted |

update, complete and maintain their memorandum of understanding, making sure that it clearly covers issues related to:

|

Accepted |

1. Audit context

Victoria has a long history of mineral and quarry exploration. Since the Ballarat gold rush started in 1851, Victoria has produced over 2 400 tonnes of gold. This accounts for 32 per cent of all gold mined in Australia and almost 2 per cent globally.

Victoria is also rich in other minerals, such as coal, silver, gemstones and heavy mineral sands, and in extractive resources, including rock, gravel, limestone and clay.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 Why this audit is important

The state’s mineral and quarry industries help grow our economy. These sectors underpin building and construction, deliver electricity, attract investments for the state, and create many jobs, including in regional Victoria.

However, these activities can also damage the environment by negatively impacting biodiversity, eroding soil, contaminating waterways, and posing risk to people, land, and infrastructure.

Once mining has finished at a site, it is important that the land is made safe, stable and sustainable. Under Victorian legislation, the operator must do this. However, if an operator defaults on this commitment, it falls to the state to rehabilitate the land. This can be very costly.

This audit provides an opportunity to assess the regulator’s progress in overseeing the rehabilitation of mines and quarry sites, and to identify any shortcomings in the process.

1.2 Mining in Victoria

In Victoria, the extraction of minerals and quarry resources falls under the Act.

Mineral licences and work authorities

The Act defines:

- ‘mining’ as the extraction of minerals from land for the purpose of producing them commercially

- ‘quarry’ as the extraction of stone, or any place or operation involving the removal of stone from land

- ‘mine’ as any land on which mining is taking place or has taken place under a licence

- ‘licence’ as an exploration, mining, prospecting or retention licence granted under the Act

- ‘work authority’ as a work authority relating to an extractive industry granted under the Act.

|

With a ... |

the land covered by the licence ... |

and the licence holder is entitled to ... |

|

Mining Licence |

may be any size |

mine the land and explore for minerals and construct mining facilities related to the mining operation. |

|

Prospecting Licence |

may be an area of less than five hectares |

explore or mine the land (this licence type is for prospectors and small-scale miners). |

|

Exploration Licence |

may be any size |

exclusive rights to explore for specific minerals, including:

|

|

Retention Licence |

will previously have been subject to an Exploration or Mining Licence |

retain rights to a mineral resource:

|

|

Work Authority |

can be used for a quarry |

extract or remove sand, stone or other quarry materials. |

Licence types and minerals extracted

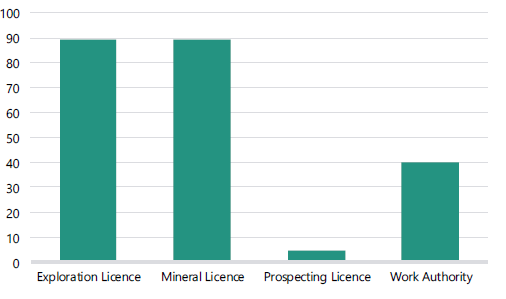

The minerals and quarry resources taken from mining sites are referred to as extractions. Figure 1A shows the relationship between licence types and different extractions.

FIGURE 1A: Licence types and extractions

| Activity type | Licence | Extractions |

|---|---|---|

| Mining | Mining Prospecting Exploration Retention |

Metals: Include gold, silver, iron and zinc Industrial minerals: Include bauxite, bentonite, diatomite, salt and talc Mineral sands: Zircon, rutile and ilmenite Coal |

| Quarrying | Work Authority | Construction materials: Hard rock, natural gravel and construction sand Dimension stone: Include bluestone, sandstone and granite Limestone and dolomite Peat |

Source: VAGO.

Contributions to the Victorian economy

Mining operations contribute significantly to the Victorian economy. The Victorian Government’s Mineral Resources Strategy 2018–2023 estimates that in 2016–17, the broader mining equipment, technology and services sector:

- accounted for 121 000 jobs

- provided $13.6 billion in direct and indirect contributions to the state’s economy.

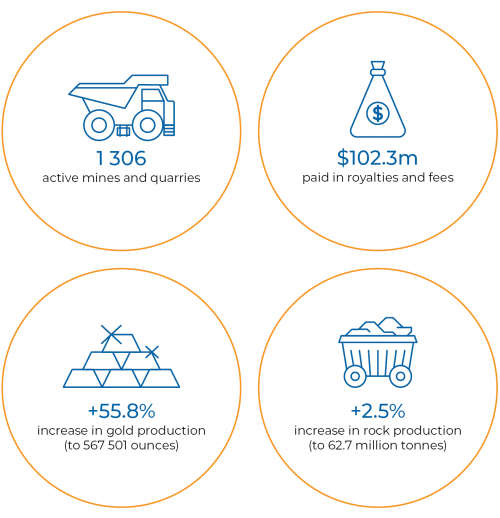

Figure 1B shows statistics for the 2018–19 financial year.

FIGURE 1B: Contributions to the Victorian economy in 2018–19

Source: VAGO, based on ERR’s 2018–19 Annual Statistical Report.

1.3 Environmental impacts

While mining brings many economic benefits, there are also downsides. In Victoria, some mining activities have resulted in severe impacts on and around the disturbed land, posing environmental, economic and safety risks to the community.

Latrobe Valley mine fire

The Latrobe Valley is home to three open-cut brown coal mines. Open-cut coal mines are particularly vulnerable to fire that spreads quickly and is difficult to extinguish.

On 9 February 2014, a fire started in the Hazelwood mine in the Latrobe Valley, and burned for 45 days. The fire caused significant environmental damage around the mine, with smoke and ash blanketing the sky for over a month. Residents experienced adverse health effects and local businesses suffered financial impacts over the fire period.

The 2014 Hazelwood Mine Fire Inquiry Report found that although it is impossible to quantify the full cost of the fire, the total cost borne by the Victorian Government, the local community and the operator of Hazelwood mine exceeded $100 million.

Risk from tailings

Tailings are waste mineral, stone or other materials left over after separating the desired mineral product from a natural rock or sediment. Tailings often consist of fine particles that have the potential to damage the environment by releasing toxic metals and contaminating soil and water supplies.

The high-risk contaminants in tailings include:

- arsenic—this naturally occurring compound is found in rock and is extremely toxic to humans, wildlife and vegetation. Gold mine tailings can hold high levels of arsenic due to the similar solubility of arsenic and gold in the ore forming fluids

- mercury—this binds to organic particles and is easily transformed into stable and highly toxic methylmercury. In this form, it can contaminate rivers and other waterways.

Other risk to groundwater and waterways

Contamination of groundwater and surface water systems by acidic water, heavy metals and other chemicals can occur when:

- tailings are discarded or a tailing dam leaches

- exposed sulphur-bearing rocks in open pit mines or underground workings oxidise and cause acid mine drainage

- water and oxygen come into contact with exposed mineralised rocks, generating water pollution

- there is other leaching from a processing plant site.

Ground movements induced by mining

Extraction activities, groundwater pressures and wall instability in open-cut mines and quarries may induce ground movements that lead to visible cracks on roads, ground surfaces and building walls.

In 2011, heavy rainfall triggered movements in the area surrounding the Latrobe Valley’s Hazelwood mine. Cracks appeared in an area near the Princes Highway and immediately north of the mine. As a result, the Princes Highway was closed for more than seven months.

In 2007, the north-east face of the Yallourn mine’s 80-metre-high wall collapsed, sliding 250 meters across the open-cut mine floor. The collapse took with it six million cubic meters of coal and earth, a mine road and two major conveyor belts.

1.4 The mining life cycle

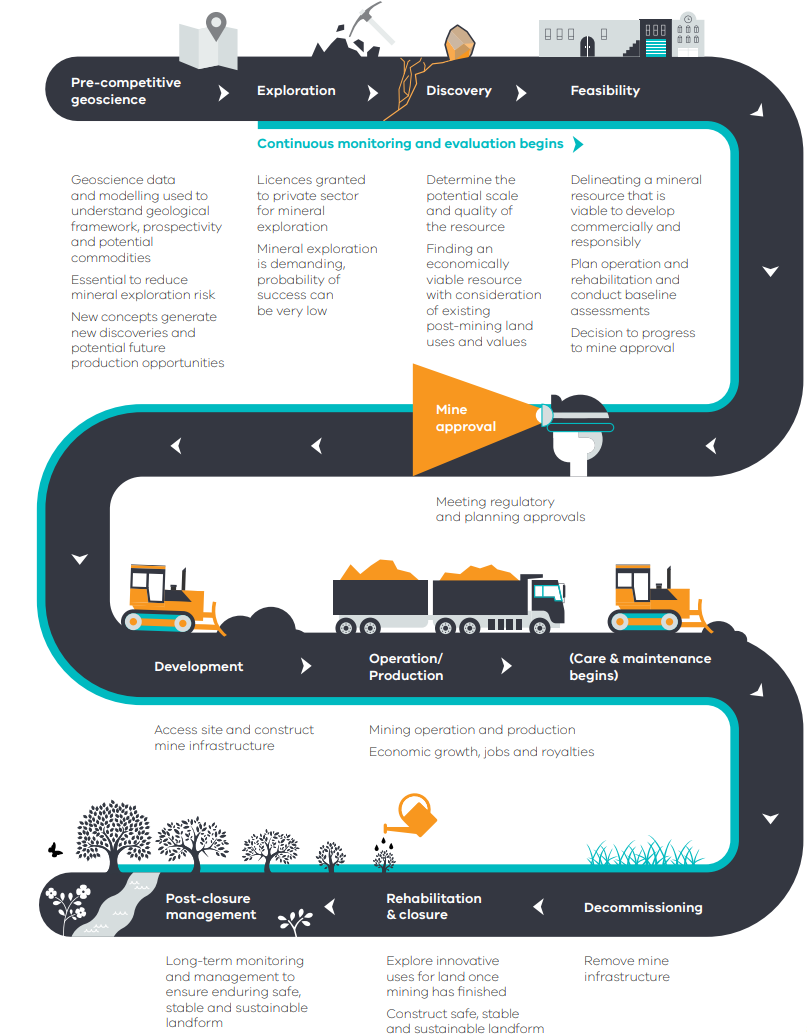

A mine’s life cycle typically runs from pre-competitive geoscience exploration to post closure management. Figure 1C shows a mine life cycle.

FIGURE 1C: Mine life cycle

Source: DJPR’s State of Discovery: Mineral Resources Strategy 2018–2023.

Status of mines and quarries

Mining licences provide rights to explore for and extract the minerals in the land and may authorise the construction of facilities associated with the mine. A work authority permits the holder to carry out quarrying activities. ERR describes mining licences and work authorities as tenements.

Figure 1D shows the main characteristics of the four states of tenements: active, inactive, abandoned and legacy.

FIGURE 1D: Characteristics of active, inactive, abandoned and legacy tenements

Source: VAGO.

1.5 Rehabilitating mines and quarries

The possibility of serious impact to the environment, people, land and infrastructure means it is vital to ensure mining operators fulfil their obligation to rehabilitate the land. This means returning land that has been disturbed to a safe, stable and sustainable condition.

Although the Act does not define rehabilitation, where applicable, it requires a rehabilitation plan to address:

- concepts for end utilisation of the site

- proposals for progressive rehabilitation and stabilisation of extraction areas, road cuttings and waste dumps

- any proposals for end rehabilitation of the site, including final security of the site and removal of plant and equipment.

Roles and responsibilities

Rehabilitation typically aims to:

The Australian Leading Practice Sustainable Development Program for the Mining Industry 2016 specifies rehabilitation as ‘the design and construction of landforms as well as the establishment of sustainable ecosystems or alternative vegetation, depending upon desired post-operational land use’.

- make the site safe and stable, ensuring the site does not pose a future environmental risk

- create a landscape that supports future land uses.

Earth Resources Regulation

While operators are required to rehabilitate the areas they have mined, the state may have to take on rehabilitation liabilities if an operator defaults. It is ERR’s responsibility to make sure the state does not end up with this liability.

ERR is responsible for approving mining licences and work authorities, authorising work plans and rehabilitation plans, setting and reviewing rehabilitation bonds, monitoring rehabilitation activities and returning the bond to the operator post rehabilitation.

In 2019, ERR completed its Assignment of Rehabilitation Responsibilities. Figure 1E summarises this.

FIGURE 1E: ERR’s Assignment of Rehabilitation Responsibilities

| Business unit | Role | Key responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Governance | Develop rehabilitation framework, strategies, policies and procedures | Manage rehabilitation improvement projects Develop rehabilitation framework (life cycle model and strategy) Develop/maintain operational policies (e.g. risk appetite framework for setting bonds |

| Assessment | Specify site rehabilitation requirements | Assess and approve/refuse rehabilitation plans Provide guidance to applicants on: (1) the preparation of rehabilitation plans; (2) onsite rehabilitation requirements Provide advice to Rehabilitation Liability Assessment and Bonds Team |

| Rehabilitation liability assessment and bonds | Assess site rehabilitation liabilities and set bonds | Update/maintain bond calculator Develop methodology and calculate the state’s contingent liabilities for site rehabilitation Prepare guidelines on the preparation of rehabilitation liability self-assessments Issue notices requiring: (1) initial liability assessments and bonds; (2) updated liability assessments and further bonds Authorise return of bonds Provide advice to Assessments Team on: (1) preparation of rehabilitation plan guidelines; (2) potential liabilities associated with proposed rehabilitation plans, including options to minimise liability risks |

| Technical services | Inform rehabilitation requirements and liabilities | Provide technical advice to Assessments Team on: (1) common risks/controls relating to site rehabilitation plans; (2) key risks/controls for specific sites relating to rehabilitation plans (such as geotechnical stability and groundwater factors) Provide technical advice to Rehabilitation Liability Assessment and Bonds Team on: (1) rehabilitation liability assessments for specific sites; (2) any residual technical issues post rehabilitation |

| Regulatory compliance | Ensure operators complete rehabilitation works | Provide field-based knowledge to inform the Assessments and Rehabilitation Liability Assessment and Bonds teams, as relevant Ensure operators’ compliance with approved rehabilitation plans, including issuing notices directing works and conducting investigations into alleged breaches |

| Licencing | Assess fit and proper status and provide administrative support | Register bonds Manage bond transfers and surrenders Return bonds on authorisation of completed works by Rehabilitation Liability Assessment and Bonds Team |

| Business management | Administer financial requirement | Manage storage of rehabilitation bonds Manage bond call-in process |

| Stakeholder and community engagement | Let people know what ERR is doing to improve site rehabilitation

|

Disseminate materials to stakeholders Coordinate responses to public inquiries |

Source: VAGO, based on ERR documentation.

Rehabilitation plans

Under the Act, an operator proposing to do work under a mining, prospecting or exploration licence must include a rehabilitation plan in its work plan application.

Since 2013, the Act has required varying levels of information on rehabilitation for each of the four mining licences.

The Act also requires a prospective quarry operator to submit a rehabilitation plan before obtaining a work authority.

The level of detail required in rehabilitation plans has changed over the years as the Act and regulations have been amended. In general, the Act requires rehabilitation plans to account for:

- the surrounding environment

- the need to stabilise the land

- any potential long-term degradation of the environment.

Rehabilitation bonds

Rehabilitating sites can be a long and expensive process. Because of this, the Act requires operators to provide a rehabilitation bond as financial security before commencing work. This is to ensure the state can rehabilitate the site should the operator default.

A rehabilitation bond is calculated to cover the full amount required to achieve the final rehabilitation outcome as specified in the rehabilitation plan.

Forms of security

Operators provide rehabilitation bonds in the form of unconditional bank guarantees by way of a letter of credit from a banking institution. However, the 2019 Rehabilitation Bond Policy for the Latrobe Valley Coal Mines provides that specifically for the Latrobe Valley mines, the Minister may consider bonds in a hybrid form—where the bank guarantee is complemented by a security in the form of a parent company guarantee.

A bank guarantee ensures that the liability of a debtor will be paid if the debtor fails to settle a debt.

From December 2015, licence and work authority holders were able to pay a cash bond if the assessed rehabilitation liability was $20 000 or less.

Bond consultation process

The Minister for Resources determines the amount of a rehabilitation bond. However, under the Act, the Minister must consult with the local municipal council and landowner, where relevant, for both mining and quarrying. ERR does this on behalf of the Minister.

Figure 1F shows a consultation matrix for bond management.

FIGURE 1F: Bond Management Consultation Matrix

| Exploration licence | Mining licence | Work authority | |||||

| Crown land | Private land | Crown land | Private land | Crown land | Private land | ||

| Bond setting | LM | LM | Owner Council |

LM | Council | ||

| Bond review | LM Licensee |

LM Licensee |

Owner Council Licensee |

LM Work authority holder |

Work authority holder | ||

| Bond return | LM | Owner | LM | Owner Council |

LM | Owner Council |

|

Note: LM refers to the Crown land manager responsible for managing the Crown land area.

Source: Bond Policy.

Bond reviews

The Bond Policy requires that ERR periodically review bonds during the life and towards the end of operations. This is to assess whether the current bonds reflect the cost required to deliver final rehabilitation.

The Bond Policy also provides ERR guidance on the frequency and timing of bond reviews per a risk-based schedule as set out in Figure 1G.

FIGURE 1G: Recommended frequency of bond reviews

| Consequences | Likelihood | |||

| HIGH | MEDIUM | LOW | NEGLIGIBLE | |

| HIGH | 2 years e.g. large mining licence—Gold |

3 years e.g. large mining licence—other metals, mineral sands |

6 years e.g. large mining licence—non-metallic (other than coal for power generation) |

10 years Coal (major power generation) |

| MEDIUM | 3 years e.g. small mining licence—Gold small mining licence—other metals |

6 years e.g. work authority—regional significance |

10 years e.g. work authority—state significance |

10 years |

| LOW | 7 years e.g. small mining licence—non-metallic |

10 years e.g. work authority—local significance |

10 years | 10 years |

Source: Bond Policy.

Rehabilitation-specific risk assessment framework

ERR’s 2019 Rehabilitation Bond Review Operational Policy provides for rehabilitation-specific risk criteria which consider the:

- likelihood of the operator defaulting on rehabilitation responsibilities and therefore the rehabilitation bond being called in

- risk that the value of the bond is inadequate to rehabilitate the sites.

Assessment criteria falls into two groups:

|

Rehabilitation risk assessment factors may be... |

For example... |

|

Primary |

Estimated bond shortfall |

|

Secondary |

Alignment between the rehabilitation plan and likely rehabilitation requirements |

This is ERR’s first framework that directly considers rehabilitation-specific risks of Victorian mines and quarries.

Return of bonds

ERR returns a bond once the land has been rehabilitated to a satisfactory level, as determined by the Minister for Resources, following the completion of a rehabilitation assessment report and the required consultation process.

Stages of rehabilitation

There are two key parts to rehabilitation—progressive activities and the final activities. Prior to final rehabilitation, operators may undertake interim rehabilitation works to manage hazards such as fire and ground erosion.

ERR plays an important role in making sure that rehabilitation is properly undertaken, beginning from the approval of a mining licence. This includes monitoring progressive rehabilitation activities, reviewing rehabilitation bonds, assessing final rehabilitation outcomes and returning rehabilitation bonds.

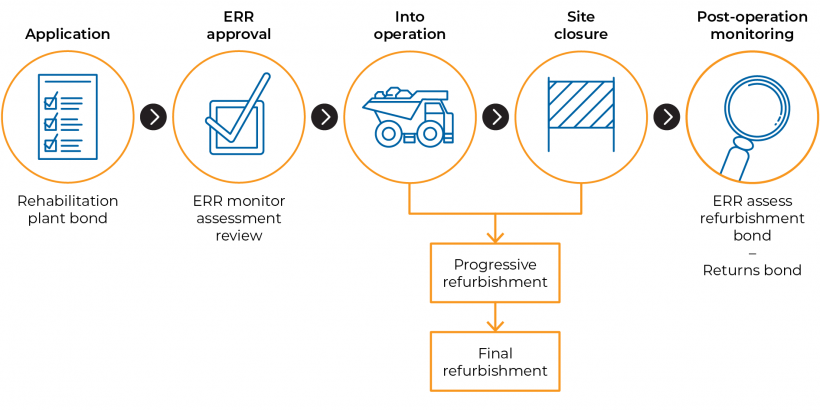

Figure 1H gives an overview of ERR’s role in managing mining rehabilitation.

FIGURE 1H: ERR's roles

Note: *For mining licences, bonds may be lodged after licence approval but before operations start.

Source: VAGO.

Progressive rehabilitation

Since the introduction of the Mineral Resources (Titles) Regulations 1991, the Act and its regulations have required operators to include progressive rehabilitation proposals in their mining rehabilitation plans.

Progressive rehabilitation should consider the timing, sequence of and benchmarks for the rehabilitation works. These include but are not limited to:

- native vegetation

- productivity of rehabilitated agriculutral land

- final slopes of pits

- tailing dams.

The progressive plan may cover the life of the licence or a shorter period, with updates required in the later stages of a mine’s or quarry’s life cycle.

Final rehabilitation

Final rehabilitation occurs after mining or quarrying operation ceases and prior to site closure and its return to the landowner. The operator undertakes work to rehabilitate the land to a safe, stable and sustainable form for future land use.

1.6 Legislative framework and other policies

The Minister for Resources directly delegates their regulatory power to the ERR Executive Director and other senior staff in ERR.

Legislation and regulations

Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) Act 1990

The Act is the primary legislation for regulating mineral and the extractive resources sector.

The Act aims to:

- encourage and facilitate exploration for minerals

- establish a legal framework to ensure risks posed to the environment and the public are minimised as far as reasonably practicable.

Mineral Resources (Sustainable Development) (Mineral Industries) Regulations 2019

The MRSDMIR was the first regulation introduced in Parliament that regulates the mineral resources sector under the Act. It has had subsequent amendments over the years and the new requirements for rehabilitation plans took effect on 1 July 2020.

Environment Protection Act 2017

The Environment Protection Act 2017 (as amended) establishes EPA and provides the foundation to protect Victoria’s environment. It also set EPA as a mandatory referral authority for mining work plan applications and variations, where a planning permit is required, from 1 July 2019.

Ministerial Statement of Expectations

The Minister for Resources’ Statement of Expectations 2018–20 outlines key areas of governance and operational performance that ERR should work on to reduce regulatory burden and improve its regulatory practice.

None of the Minister’s 14 specific expectations in the statement relate directly to rehabilitation. The focus is to implement the recommendations of the Commissioner for Better Regulation’s 2017 Getting the groundwork right: Better regulation of mines and quarries, which was triggered by perceived delays and uncertainties in ERR’s approval processes.

In September 2018, DJPR committed to implementing the 14 specific expectations.

Mineral Resources Strategy

The Victorian Government developed the Mineral Resources Strategy 2018–2023 to help grow investment and jobs in Victoria’s minerals sector by:

- building community confidence in social, environmental and economic performance of mineral exploration and development

- improving the state’s attractiveness for minerals investment

- strengthening the state’s position as a global mining and mining services centre.

Extractive Resources Strategy

The government developed the 2018 Extractive Resources Strategy to ensure that high-quality extractive resources continue to be available at a competitive price to support the state’s growth. Its objectives include:

- providing secure and long-term access to extractive resource areas of strategic importance to the state

- maintaining and improving Victoria’s competitiveness and providing greater certainty for investors in the extractives sector

- encouraging leading-practice approaches to sustainability, environmental management and community engagement.

The Bond Policy

The Bond Policy s provides that ERR is responsible for setting, reviewing and returning the rehabilitation bonds for mines and quarries in Victoria.

Regulatory Practice Strategy for the Rehabilitation of Earth Resources Sites

In February 2020, ERR released the Regulatory Practice Strategy for the Rehabilitation of Earth Resources Sites, which outlines the approach and actions underway to improve how it plans and manages rehabilitation of mines and quarries over their life cycle.

It sets out the strategic objectives of:

- protecting people, land, infrastructure and the environment

- ensuring land can be returned to a safe, stable and sustainable landform

- minimising the state’s exposure to rehabilitation liabilities

- being a best-practice regulator.

1.7 Relevant agencies

Figure 1I lists relevant agencies’ responsibilities.

Figure 1I: Mining rehabilitation responsibilities

| Agency | Responsibility |

|---|---|

| DJPR (ERR) | Administers the Act and the MRSDMIR, including approving rehabilitation plans, monitoring and enforcing operators’ compliance with mining rehabilitation responsibilities, and setting, reviewing and releasing rehabilitation bonds. |

| EPA |

Regulates offsite discharges of water from earth resources sites. Sets discharge standards that ERR requires operators to comply with. Approves licensing for landfills and other regulated waste facilities when not regulated by the Act. A mandatory referral authority for mining and quarrying work plans, and variations, where a planning permit is required—which includes rehabilitation plans. Participates in Environment Effect Statement process by providing technical expertise to relevant decision makers. Other than as indicated above, EPA has no direct role in managing/regulating/commenting on rehabilitation works. However:

|

| DELWP |

Manages land use planning and environmental assessments in the state. As a referral authority, DELWP comments on work plans including rehabilitation plans and manages legacy/historic sites on Crown land. In general, has no direct role in managing/regulating/commenting on rehabilitation works. Exceptions include:

|

| Catchment Management Authorities |

Manage regional waterways, floodplains, drainage and environmental water reserves under the Water Act 1989. They are also referral authorities for mining and quarrying work plans when proposed land involves floodplains. In general, they have no direct role in managing/regulating/commenting on rehabilitation works. |

| LVMRC | LVMRC was established in May 2017 as a statutory office to monitor and audit Latrobe Valley mine rehabilitation. Although the audit scope excludes the regulation of the Latrobe Valley coal mines, as DJPR and DELWP were developing the Latrobe Valley Regional Rehabilitation Strategy(a) during the audit, we consulted LVMRC(b) on the current rehabilitation regulatory practice. |

Note: (a) The Minister for Resources released the Latrobe Valley Regional Rehabilitation Strategy on 26 June 2020.

Note: (b) The new Mine Land Rehabilitation Authority superseded the roles and functions of the LVMRC on 30 June 2020.

Source: VAGO, based on ERR Compliance Strategy 2018─20, and the Environment Protection Act 2017 (as amended), Planning and Environment Act.

2. Rehabilitation liabilities

Conclusion

ERR has not effectively regulated rehabilitation bonds, meaning the state is financially exposed to significant costs for site rehabilitation. The amount ERR holds in bonds is likely to be at least $361 million short of the estimated cost of rehabilitating Victoria’s existing mines and quarries.

ERR cannot demonstrate that it ensures sites have been rehabilitated, as required, before returning the bond to operators. This includes ensuring that the state has no remaining liability.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Overview

Rehabilitation bonds ensure that the government has sufficient funds to rehabilitate mine and quarry sites if operators do not or are unable to do so.

ERR’s Bond Policy explains that rehabilitation bonds are calculated to fully cover rehabilitation costs. As such, rehabilitation bonds ensure that:

- rehabilitation costs do not fall to Victorian taxpayers

- mines and quarry sites are appropriately rehabilitated and closed.

2.2 Rehabilitation bonds

Current rehabilitation bonds held by ERR

Available ERR data suggests that as at December 2019, ERR holds $813 million in rehabilitation bonds for 1 394 mines and quarries across Victoria.

The bonds for the three coal mines in the Latrobe Valley account for $591 million, or nearly 75 per cent, of the total. The remaining $222 million secures the remaining 1 391 mines and quarries across the state.

Difference between bonds held and actual rehabilitation liability

Actual rehabilitation liabilities for Victoria’s mine and quarry sites are considerably higher than what is held in these bonds. It is not clear exactly how much more.

ERR’s preliminary assessment in November 2019 suggests that there is a shortfall of at least $361 million. Figure 2A illustrates this.

FIGURE 2A: Rehabilitation bonds and rehabilitation liabilities

Source: VAGO.

ERR advised us, however, that this preliminary estimate is only intended for scoping and planning future regulatory actions and should not be considered as an accurate estimate of actual rehabilitation liabilities. ERR further advised that this estimate is an initial assessment and that it will conduct further reviews to accurately determine total rehabilitation costs.

Low estimate

$361 million is a low estimate.

ERR’s determination of the rehabilitation liabilities for some of the sites was informed by various factors including the operators’ self-assessment of actual liabilities. However, for most of the 1 394 mines and quarries, ERR acknowledges that its assessment was completed largely as a desktop analysis. It applied:

- $10 000 as the estimated rehabilitation cost for mines and quarries having less than $10 000 in rehabilitation bonds (over 500 sites)

- a modest 10 per cent increase in rehabilitation cost for sites with bonds of at least $10 000 (over 800 sites).

Prior to this assessment, ERR had not attempted to determine the liability. This is ERR’s first serious effort to estimate the difference between the rehabilitation bonds it holds and the actual rehabilitation liability for mines and quarries across the state.

ERR advised us that it will conduct further reviews to accurately determine total rehabilitation costs. However, it is not clear whether ERR will do site inspections or require further evidence from operators to achieve this. It is also not clear when ERR will conduct these reviews.

Low-value rehabilitation bonds

According to available ERR data, as shown in Figure 2B, 1 239 mines and quarries have rehabilitation bonds above $0 and below $200 000. For 526 of these (covered by mining licences and work authorities), the bond value is $10 000 or less.

This is not sufficient to cover rehabilitation costs.

FIGURE 2B: Rehabilitation bonds by value range as at December 2019

| $500K | $200K–500K | Under $200K | No bond—$0 | No bond on record |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 65 | 52 | 1 239 | 36 | 2 |

Source: VAGO, based on ERR documents.

ERR’s Bond Policy provides a standard bond rate of $4 000 per hectare for small and low-risk quarries. It defines these as being less than five hectares in area and less than five metres in depth, and not requiring blasting or native vegetation clearance.

Small and low-risk quarries are operated under ERR’s Code of Practice and as such are not subject to all the requirements of the Act. For example, because of their relatively low rehabilitation risk, a rehabilitation plan is not required. Their operators, however, still need to rehabilitate the site post operation.

However, we identified, in ERR’s data listing:

- 224 sites of five hectares or less, with rehabilitation bonds less than $4 000 per hectare

- 275 sites of greater than five hectares, with rehabilitation bonds less than $4 000 per hectare. Within this group, there are 100-hectare gold mines.

Given $4 000 per hectare is considered necessary for small, low-risk operations, it is unlikely that a lesser value represents a suitable rehabilitation bond rate for larger and more complex sites.

ERR contests this comparison and maintains that for mine and quarry sites larger than five hectares, the $4 000 per hectare rate should only be applied to the disturbed area and not the entire site.

We requested data on the disturbed area for these 526 mines and quarries. ERR was able to provide information for 11. For six of these sites, considering the size of the disturbed area only, the rehabilitation bonds significantly fell short of $4 000 per hectare, while the remaining five only just met the standard rate.

Rehabilitation bonds are meant to ensure that the state has funds to restore sites if operators do not. The fact that many sites have bonds that are less than what is deemed enough for basic quarry operations means that the state is potentially exposed to significant financial risk.

Mines and quarries with no rehabilitation bonds

The Act requires an authority holder to enter a rehabilitation bond sufficient to cover full rehabilitation costs before commencing operations:

- For mining licence holders, the bond needs to be lodged prior to carrying out any work on the land.

- For quarry operators, a bond needs to be in place before ERR grants a work authority.

When we reviewed ERR’s data on mining licences and work authorities, we identified 578 mines and quarries with no rehabilitation bond noted:

- 24 sites, we were able to confirm are operating and therefore should have bonds in place.

- 14 sites have licences or work authorities that are no longer valid but are yet to be rehabilitated, and therefore should have bonds in place.

- 168 mines according to ERR have not started ground operations and therefore do not require bonds. However, ERR was unable to provide documentation to support this claim.

- 372 mines and quarries according to ERR have had their bonds either returned to operators or called in for rehabilitation works. However, ERR was unable to provide documentation to support this claim.

ERR acknowledges that limitations in its record keeping and information management systems mean it cannot assure that these sites do not require rehabilitation bonds.

ERR is in breach of its regulatory responsibility to ensure that mines and quarries have rehabilitation bonds as required by the Act.

2.3 Contingent liability

If operators default on their obligation to rehabilitate their site, the state may be liable to do this.

DJPR’s reported contingent liability

DJPR’s 2018–19 Annual Report recorded a $29.8 million state government CL for mining site rehabilitation.

How CL is calculated

To estimate the state’s CL for mining rehabilitation, ERR used its rehabilitation risk assessment framework. This is the first time ERR has developed and implemented a risk assessment framework specific to rehabilitation liabilities. Section 2.4 further discusses the framework. ERR calculated the state’s $29.8 million CL as shown in Figure 2C.

FIGURE 2C: Calculating CL

Source: VAGO.

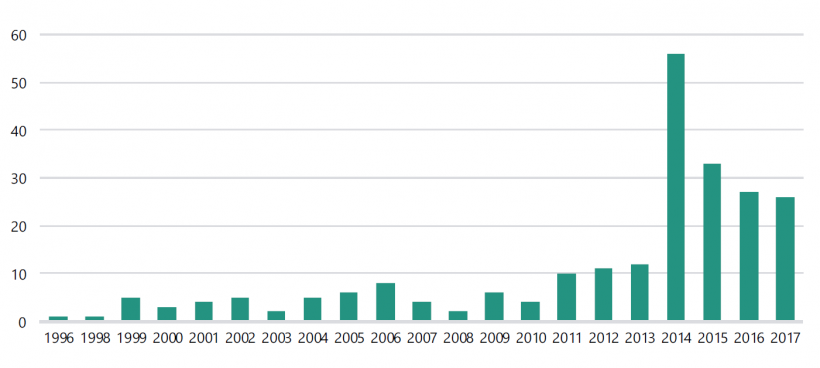

Figure 2D shows DJPR’s reported mining rehabilitation CL since 2015–16.

FIGURE 2D: Mining rehabilitation contingent liabilities reported by DJPR

Source: VAGO, based on DJPR annual reports.

It is unclear why the amount of CL reported was $0 as at 30 June 2016. The then DEDJTR’s 2015–16 Annual Report did not explain this.

Low CL estimate

The $29.8 million CL reported in 2018–19 is significantly higher than the $1.7 million that the then DJPR reported in its 2017–18 Annual Report.

This difference is not due to increased risks in 2018–19, but rather to ERR’s previous lack of rigour in determining the state’s potential rehabilitation liability.

ERR acknowledges that the $29.8 million figure is still an underestimate. As at November 2019, ERR advised that the state’s CL could be $50 million for all Victorian earth resources sites.

It is expected that DJPR will again report on the state’s mining CL in its 2019–20 annual report.

ERR’s plan to better calculate CL

ERR advised that it will review its assessment of the state’s CL against a number of risk factors, including:

- the difference between current rehabilitation bond values and estimated actual rehabilitation liability

- public, land, infrastructure and environmental risks at each site

- the operator’s financial position.

ERR is yet to determine the timeline for completing this as it is subject to resourcing.

2.4 Regulating bonds

Setting the rehabilitation bond

ERR’s process of setting rehabilitation bonds does not ensure the calculated bond value covers the full cost of rehabilitation.

Rehabilitation bond calculator

ERR’s March 2019 internal audit identified limitations in its rehabilitation bond calculator.

|

ERR's bond calculator... |

For example... |

|

is outdated—it was last updated in September 2010 |

input rates have not been adjusted to reflect changes to the consumer price index, which has increased by 19.8 per cent (2019) since 2010. |

|

does not take into consideration factors that affect rehabilitation costs |

it does not take into account the remoteness of sites and operations in areas of high environmental sensitivity. |

|

cannot be adequately tailored for varying operations—a single calculator is used for all types of operations |

the calculator does not have inputs for extractive industries that require specific rehabilitation techniques. |

Our consultation with industry stakeholders and ERR staff confirmed these issues remain.

ERR is now revising its calculator. It commissioned a specialist service provider to inform the required changes with this work including a comparative analysis of the bond calculators used in New South Wales and Queensland.

ERR advised that it was on track to release the updated bond calculator by December 2020 but due to the economic uncertainty caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, it has postponed its March 2020 stakeholder consultations. This might mean that ERR will not meet its planned timeline for the release of the calculator.

Bond setting consultation

The Act and regulations require ERR to consult councils and DELWP, as Crown land manager, when setting the initial value of rehabilitation bonds. We reviewed a random selection of 10 mineral licences and work authorities with mixed risk ratings.

Two files had no recorded evidence that ERR undertook the necessary consultation to inform their bond setting. In the other eight instances, consultation did take place, but the stakeholders’ input does not appear to have been useful in setting bonds.

ERR is not obtaining the information needed from bond setting consultations because:

- most council officers do not have the technical skills to provide meaningful comments on rehabilitation bonds

- ERR does not guide councils on what they need to consider in the bond setting process

- DELWP’s regional officers are often not presented with sufficient information on proposed rehabilitation works, potential environmental impacts and related rehabilitation costs to allow them to properly contribute.