Access to Public Housing

Overview

Providing access to public housing is an important way that the government assists those in housing need. This audit examined how effectively the Department of Human Services (the department), through its Housing and Community Building division (the division), plans for and maintains public housing assets, to support current and future access for eligible tenants.

The situation for public housing is critical. The current operating model and asset management approach places the long-term provision of this vital public service at risk.

The operating model, with costs increasingly exceeding revenues, is unsustainable and the division is forecast to be in deficit in 2012–13. The department has not implemented longer-term strategies to address this, instead using short-term approaches such as reducing acquisitions and preventative maintenance. The division now has an estimated 10 000 properties, 14 per cent of the portfolio, nearing obsolescence and a significant maintenance liability.

There is no current asset management strategy for the public housing portfolio and past strategies do not meet Department of Treasury and Finance guidelines or established asset management practices. The department lacks basic information, such as accurate property condition data, to inform strategic asset decisions.

The department is now working to develop a new Housing Framework and has commenced financial modelling of new approaches and an update of property data. As cost and demand pressures are unlikely to abate, and the current model is not working, change is necessary. New directions must innovate so that access to public housing can be better managed and sustainable into the future.

Access to Public Housing: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2012

PP No 118, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Access to Public Housing.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

28 March 2012

Audit summary

Safe, secure housing is essential for good health, employment, education and community wellbeing. Without access to affordable housing, some people risk homelessness or struggle to meet utility, food and other basic living costs. Public housing is an important way that government assists those in housing need.

The Housing and Community Building Division (the division) of the Department of Human Services (DHS) is responsible for the management of public housing, which is generally government owned and managed. At June 2011, there were 65 352 dwellings and 127 357 tenants in public housing, and 38 244 eligible households on the public housing waiting list.

Public housing is facing significant challenges. Against a background of finite government resources, demand has grown due to reduced housing affordability and demographic changes such as population ageing, and more and smaller households. Increased targeting of public housing has changed the tenant profile to those with more complex needs and lower incomes. Public housing infrastructure is also ageing, requiring significantly increased maintenance. These challenges highlight the importance of effective asset management that not only delivers portfolio value but also provides access to housing that allows people to live, work and thrive.

Providing access to public housing, now and into the future, requires a sustainable asset base that meets community need. Careful planning using accurate information, for example, about housing demand, the current and projected tenant profile, and the asset condition, is a prerequisite. Long-term direction detailing service outcomes, comprehensive asset management strategies that consider the full life of assets, opportunities for innovation, and adequate performance measures to track progress are also vital.

This audit examined how effectively the division plans for, and maintains public housing assets, to support current and future access for eligible tenants.

Conclusions

The situation for public housing is critical. The current operating model and asset management approach places the long-term provision of this vital public service at risk. Despite a growing need for housing support in our community, DHS has not set overarching direction for public housing or taken a strategic, comprehensive approach to managing this $17.8 billion property portfolio.

The operating model for public housing, with costs increasingly exceeding revenues, is unsustainable. By using short-term strategies, such as reducing acquisitions and preventative maintenance, the division is deferring the problem. However, this cannot continue indefinitely. The seriousness of the situation is expressed in a 2011 report, for the Minister for Housing, that forecasts cash running out in 2012–13 and the division in deficit.

It is unclear why the division has not introduced longer-term strategies to address this acute situation given that it has developed over at least a decade. Since at least 2006, other departments, including the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and the Department of Premier and Cabinet, have also been aware of the deteriorating state of public housing, yet this has not spurred action.

There are no clear long-term objectives for public housing. Long-term objectives are important to guide management of an asset base with a long life span that requires substantial lead times for redevelopment or renewal. Now that public housing is nearing a crisis, it will be all the more challenging to address.

The division's lack of comprehensive asset management has meant missed opportunities to more strategically position the public housing portfolio. The division has an estimated 10 000, or 14 per cent of properties nearing obsolescence and a significant mismatch of properties to tenant need. Yet, there is no asset management strategy in place. Past strategies fall well short of DTF and other established asset management guidelines, and the division lacks basic information, such as accurate property condition data, to inform decisions. These failings expose a serious deficit in asset management skills within DHS, which must be addressed. Effective asset management is fundamental to supporting current and future public housing provision.

Work is underway to develop a new housing framework for the future direction of public housing. While developing a sustainable operating model is a central goal of the framework, at the time of the audit the division had yet to fully assess the financial impact of policy options under consideration. Accordingly there is no evidence at this point that the framework will address sustainability. The current operating approach is not working, and cost and demand pressures are unlikely to abate, so change is necessary. New directions must explore innovative options for providing public housing and should consider the future role of the division, so that access to public housing can be better managed and sustainable into the future.

Findings

An unsustainable operating model

Public housing rents are set at no more than 25 per cent of tenant income. Prioritisation of public housing to those in greatest need has increased the proportion of unemployed tenants who are receiving benefits. In turn, this decreases the division's rental revenues. At the same time, the division's operating costs have substantially increased. Despite this, the division has never reviewed its efficiency.

In 2011, the Minister for Housing commissioned a review of the financial position of public housing. The review found that 2011 operating costs exceeded rental revenue by 42 per cent, up from 30 per cent in 2002. The review forecasts the division's deficit to more than double from $56.4 million in 2011 to $115.1 million in 2015 and that all cash reserves will be exhausted in 2012–13. To date, the division has used short-term strategies to address the financial situation. These strategies include reducing acquisitions, deferring preventative maintenance, and funding deficits by utilising cash meant for long-term programs. This only compounds the issue, particularly the growing maintenance liability. The public housing portfolio is now in a seriously deteriorating condition with the division estimating that 10 000 properties, 14 per cent of the total, will reach obsolescence over the next four years.

Planning for the future

Apart from increased prioritisation of public housing to people in greatest need, there has been little change in public housing policy regarding the operating model over the past decade. Pursuing growth of community housing and initiatives under national partnership agreements through time-limited Commonwealth funding has been the main focus.

Over this period, the division has not articulated long-term objectives for the public housing portfolio, or undertaken long-term planning. This is problematic as changes to these fixed assets require substantial lead time. Stock turnover is slow, given the long life span of houses, and new builds and redevelopments take years from concept to completion. Challenges which emerged a decade ago, such as the increase in demand for one-bedroom properties and the increasing operating deficit, continue not to be addressed. The division has not adequately explored alternative models to manage public housing sustainably or reassessed its own role in the provision of public housing.

The new housing framework is under development and due to go to public consultation in the first half of 2012. However, financial modelling of proposed policy options is not complete, and so it is not yet clear how the framework will address the unsustainable operating model.

Poor asset management

Such a large property portfolio warrants comprehensive asset management, yet there is no current asset management strategy. The division's past asset management strategies lacked basic elements such as annual updating, consideration of the full life cycle of assets, and comparison of current to desired stock, in terms of size or location. The last asset management strategy, which expired in 2011, neither aligned with overarching DHS strategic plans and objectives, nor articulated any desired future for public housing. There was no gap analysis or any articulation of how planned activities would meet future need. The strategy also did not analyse options for portfolio management or identify where or how value could be extracted from the property portfolio.

Past asset management strategies were not reviewed and updated regularly. The division uses no performance measures for its asset management, and as such, its performance in this area has not been evaluated.

Poorly informed decision-making

Effective asset management decisions require a reliable evidence base. The division collects information on tenant characteristics and preferences from waitlist and census data, and affordable housing supply information that it applies to individual asset decisions. However, the division does not have accurate, up-to-date property condition data, does minimal forecasting of future need, and obtains limited input from important stakeholders such as its regional offices and tenants. It does not apply this information systematically, for example to a broader asset strategy or future plan.

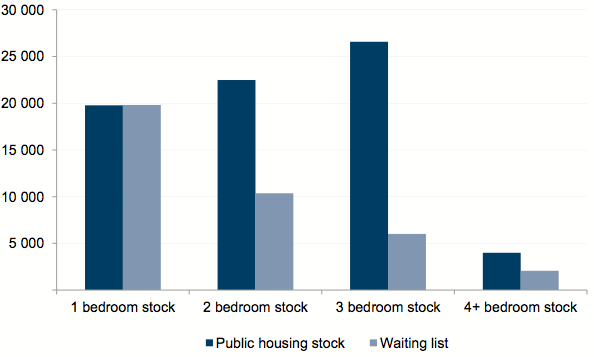

While the division can demonstrate progress in the better matching of housing stock to tenant needs, there is still a substantial mismatch between public housing property types and tenant requirements. The portfolio contains too many large properties, while current demand is for single bedroom accommodation. Earlier system-level forecasting of future need, linked to asset strategies, would have helped mitigate this. Better property condition data would also have highlighted maintenance issues earlier.

The rationale for the division's investment decisions is also unclear, with no clearly documented and communicated decision-making criteria. This is particularly difficult for regional offices that do not understand, and therefore can only provide limited input into, central office decision-making.

Recommendations

The Department of Human Services should:

- develop and apply options to overcome the unsustainable operating model

- assess its operational efficiency and role in public housing

- develop a long-term plan for public housing with clear objectives

- develop a comprehensive asset management strategy and vigorously monitor performance

- at the regional level, capture local knowledge and communicate investment criteria

- update and strengthen property condition data across the portfolio

- apply relevant data and medium- and longer-term forecasts to asset management strategies.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Human Services with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Safe, secure housing is essential for good health, employment, education and community wellbeing. Without access to affordable housing, some people face homelessness or struggle to meet utility, food and other basic living costs.

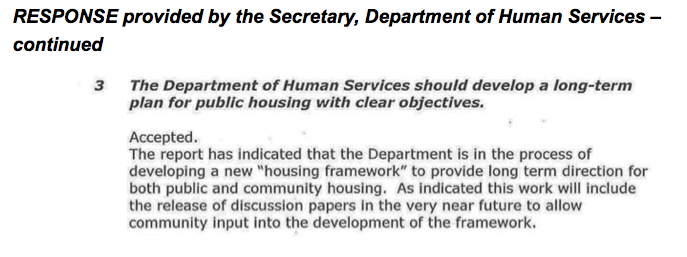

Victoria is experiencing a shortage of available affordable housing as population growth exceeds housing supply, intensifying demand and increasing costs in the private rental market. In turn, this has driven demand for government-supported housing. Figure 1A illustrates the range of social housing programs, which includes public and community housing.

Figure 1A

State government supported housing options

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

This audit focuses on public housing. Public housing is government owned or leased, and managed. It provides affordable rental accommodation, at less than market rates, with rent no more than 25 per cent of the tenant’s income. It also offers secure tenure. In contrast, community housing is partly funded by the government and managed by not-for-profit organisations. These rents are determined as a percentage of market rates and may be more than 25 per cent of the tenant’s income.

Community housing was the focus of the 2010 VAGO performance audit Access to Social Housing. Crisis housing and homelessness responses will be the focus of a future VAGO performance audit currently planned for 2012–13.

1.2 Public housing in Victoria

Public housing is the main source of social housing in Victoria. At June 2011, there were 82 927 social housing dwellings in Victoria, 65 352 (78.8 per cent) of which were public housing, owned and managed by the Department of Human Services (DHS). Figure 1B shows the total number of public housing dwellings by type at 30 June 2011.

Figure 1B

Department of Human Services owned and managed public housing by dwelling type and region

|

Separate house |

Semi-detached house |

Medium density |

Flat, low‑rise |

Flat, high-rise |

Movable unit |

Other |

Total |

Per cent of total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Barwon South West |

||||||||

|

2 718 |

147 |

1 115 |

1 039 |

0 |

92 |

4 |

5 115 |

7.8 |

|

Gippsland |

||||||||

|

1 859 |

143 |

831 |

726 |

0 |

75 |

6 |

3 640 |

5.6 |

|

Grampians |

||||||||

|

1 635 |

110 |

446 |

800 |

0 |

69 |

1 |

3 061 |

4.7 |

|

Hume |

||||||||

|

2 422 |

215 |

696 |

791 |

0 |

169 |

24 |

4 317 |

6.6 |

|

Loddon Mallee |

||||||||

|

2 286 |

189 |

1 049 |

1 073 |

0 |

105 |

16 |

4 718 |

7.2 |

|

Eastern Metro |

||||||||

|

1 963 |

335 |

2 286 |

1 182 |

0 |

263 |

13 |

6 042 |

9.2 |

|

North West Metro |

||||||||

|

5 864 |

1 696 |

5 346 |

5 719 |

5 625 |

518 |

37 |

24 805 |

38.0 |

|

Southern Metro |

||||||||

|

3 926 |

544 |

3 542 |

3 671 |

1 542 |

411 |

18 |

13 654 |

20.9 |

|

Total |

||||||||

|

22 673 |

3 379 |

15 311 |

15 001 |

7 167 |

1 702 |

119 |

65 352 |

100 |

Legislative framework

The Housing Act 1983 (the Act) establishes the role and responsibilities of the Director of Housing, the largest landlord in Victoria, and a role currently filled by the Executive Director of the Housing and Community Building Division (the division) of DHS. The first objective of the Act is to ensure that every person in Victoria has adequate and appropriate housing at a price within his or her means. Other objectives include:

- the provision of well-maintained public housing of suitable quality and location

- the promotion of cost-effectiveness in the provision of housing

- the integration of public and private housing

- the promotion of security and variety of tenure

- the participation of tenants and other community groups in the management of public housing.

The Act gives powers to the Director of Housing to purchase, develop, lease and sell property.

Public housing policy

Previous governments released two policies relevant to public housing. In 2003, the Strategy for growth in housing for low income Victorians aimed to increase the provision of affordable housing options through partnerships with community housing associations. In 2010, the Integrated housing strategy was, among other things, designed to provide better public housing through an asset regeneration plan for inner‑city public housing estates, and the construction of 800 new public housing units. The government is developing a housing framework due for release in 2012.

Funding for public housing

Funding for the division in 2011–12 is $401.9 million, with $168.8 million for social housing activity. This funding covers community and public housing and comes from three sources:

- state and Commonwealth funds under the National Affordable Housing Agreement and supporting agreements such as Social Housing and Nation Building partnership agreements

- additional state funds

- internally generated funds from owning and operating rental properties, such as rental income and proceeds from asset sales.

DHS central office allocates funds to the regional offices as described in each financial year’s Housing Policy and Funding Plan.

1.3 Role of the Department of Human Services

Within DHS, the division is responsible for public housing, including the management of applications, allocations, asset management and procurement, and tenancy management. The role of the division is to:

- provide more and better affordable rental housing

- upgrade and improve public and social housing to be environmentally sustainable and better integrated with the whole community

- support those most in need with more training and employment opportunities, provide crisis accommodation and tackle the causes of homelessness in Victoria.

Asset management

Maintaining, improving and growing public housing assets is an essential function of the division. Good asset management means applying plans that deliver public housing over the lives of these assets in a way that is cost-effective.

In 1994, the Department of Treasury and Finance set down principles that guide public sector asset management, and they remain true today. They include:

- following an integrated approach—aligning asset management requirements and service outcomes to overarching plans and objectives

- focusing on service delivery—all planning, decisions and reporting should focus on the type and quality of services the community needs

- making evidence-based asset decisions—by relying on rigorous information about the costs, benefits and risks of alternatives across the asset life cycle.

Making these principles operational involves:

- setting clear and comprehensive targets for levels of service

- forming a long-term plan and annual priorities, showing how agencies will make best use of assumed levels of funding to achieve these targets

- regularly measuring performance and forecasting how current decisions and agencies' long-term plans are likely to affect levels of service.

1.4 Public housing challenges

Demand

The demand for public housing has exceeded supply over the audited period of the past ten years. The cost of living and household numbers have increased and the availability of affordable housing has decreased.

The demand for public housing is measured as the number of households that have applied for public housing and are on the public housing waiting list. At June 2011, there were 38 244 households on the waiting list. Once applicants are approved for public housing, they still have to wait to be housed. In 2009–10, applicants who had received a priority allocation waited an average of 8.5 months for housing. Non-priority applicants wait several years.

A changing tenant profile

The tenant profile of public housing has changed substantially. Many of the larger estates built in the 1960s were intended for working families on low to moderate incomes, as a transitional measure, before they moved into the private housing market. Public housing today serves those most in need, with an increasing proportion of elderly, single and economically and socially disadvantaged tenants. As a result, public housing has increasingly been allocated to people with complex needs, including mental health, drug and alcohol issues, a disability, and people with very low incomes. This shift has increased the cost of housing requirements and tenancy management and services. It has also resulted in lower rental returns and turnover of dwellings.

Ageing and inappropriate infrastructure

Forty-two per cent of housing stock is over 30 years old. Properties of this age generally require more frequent and larger scale repairs, maintenance and upgrades. Most properties were also built to meet the needs of families as opposed to an increasingly single and older tenant group.

1.5 Audit objective, scope and method

The audit objective is to examine how effectively DHS plans for, and provides access to, public housing by assessing whether:

- plans and strategies are in place to support the provision and maintenance of public housing

- plans and strategies are evidence based

- plans and strategies are implemented, and performance against objectives is reviewed and acted on.

The audit examined the central office of the Housing and Community Building Division, along with two metropolitan and two rural/regional offices. Public housing tenants were consulted as stakeholders through interviews and forums.

Part 2 of the report examines outcomes and future direction for the public housing portfolio and Part 3 looks at DHS’s management of public housing assets.

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

The audit cost was $270 000.

2 The state and future of public housing

At a glance

Background

Public housing is facing major challenges, including growing demand due to reduced housing affordability, more tenants with complex needs, ageing infrastructure and high maintenance costs. Meeting these challenges to provide access to public housing now and into the future requires decisive direction and a sustainable operating model.

Conclusion

Public housing is operating unsustainably and without direction. The Department of Human Services’ (DHS) Housing and Community Building Division (the division) has been slow and short-sighted in responding to a changing operating environment. Despite DHS and the departments of Treasury and Finance and Premier and Cabinet awareness of the problem for at least six years, sustainable solutions are yet to materialise. New directions now being developed through the housing framework must innovate and unlock portfolio value to assure viable public housing in the future.

Findings

- Public housing’s operating model is unsustainable. Costs are outstripping rental income and the division is forecast to be in deficit in 2012–13.

- The division’s short-term strategies to address the financial position have deferred and compounded the problem.

- The asset base is deteriorating, with an estimated 10 000 properties reaching obsolescence.

- The division has not articulated long-term objectives or plans for public housing.

- A housing framework is being developed but it is not yet clear how it will support public housing sustainability.

Recommendations

The Department of Human Services should:

- develop and apply options to overcome the unsustainable operating model

- assess its operational efficiency and role in public housing

- develop a long-term plan for public housing with clear objectives.

2.1 Introduction

Public housing is facing major challenges, including growing demand driven by reduced housing affordability, an increasing percentage of tenants with complex needs, ageing infrastructure and high maintenance costs. These challenges require a long‑term vision and clear direction, and the application of a secure and sustainable operating model, to enable those in need to access public housing, now and into the future.

2.2 Conclusion

Public housing is operating unsustainably and without strategic direction to address this. This puts the long-term provision of this vital public service at risk and, in the short-term, the Housing and Community Building Division (the division) of the Department of Human Services (DHS) is forecast to run out of cash in 2012–13. The unsustainable operating model is the result of reduced revenue, because of a greater percentage of very low‑income tenants, and increased operating costs.

The current situation has been developing over an extended period. DHS and other government departments, including the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC), have been aware of the problem for at least six years. Despite this, no remedies have been put in place.

The division has addressed its financial position through short-term measures such as deferring acquisitions and preventative maintenance, which only compound its significant maintenance liability. The division now estimates that 10 000, or 14 per cent, of its properties are near obsolescence. The division has also never reviewed its efficiency, despite significantly increased administrative costs.

The division has not articulated long-term objectives or plans for public housing. Housing assets have a long life span, and so change requires substantial lead time. The division’s lack of forward thinking makes acute problems, such as the mismatch between dwelling types in the portfolio and tenant need, more challenging to address. The division has not adequately explored alternative models to manage public housing sustainably, or assessed what future role it should play in providing public housing.

At March 2012, the division had not yet completed work to evaluate the financial effect of policy options being considered under the new housing framework, and so, at this stage, it is unclear how it will address the underlying structural deficit. New direction in public housing must innovate to provide ongoing access to public housing.

2.3 The public housing operating model

2.3.1 Financial non-viability

The division has not operated in a focused and outcome-oriented manner to sustainably manage public housing. The public housing operational model is not financially viable, as it has a structural deficit. The division’s costs exceed revenue, as rental income is increasingly less than the outgoing costs for services such as maintenance, rates, security and insurance.

Revenue growth is extremely constrained. Rents are significantly below market rates and set at no more than 25 per cent of the tenant’s income. Calculations of tenant income also exclude or limit the inclusion of some Commonwealth payments and recent pension increases. This assists people on very low incomes to meet other costs such as food and transport. Greater prioritisation of public housing to those of highest need has increased the percentage of tenants without employment and receiving government benefits, and has consequently decreased rental income.

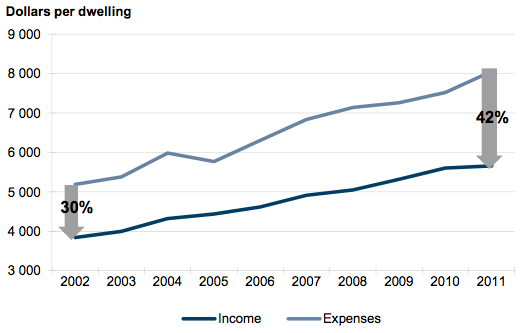

Increased operating costs are exacerbating this revenue reduction, resulting in a ballooning deficit. While rent and other property income has increased by 6.8 per cent (in nominal terms by $24.1 million between 2007 and 2012), operating costs have increased by 26.9 per cent (in nominal terms by $91.9 million) over the same period. Figure 2A shows that across the portfolio, the gap between rental income and operating costs has increased from 30 per cent in 2002, to 42 per cent in 2011.

Figure

2A

Growing gap between public housing rental income and expenses 2002–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Department of Human Services data.

A 2011 review, commissioned by the Minister for Housing, forecasts the deficit to more than double from $56.4 million in 2011, to $115.1 million in 2015. The review states that the division is ‘facing a cash crisis with all cash reserves expected to be exhausted during the 2012–13 financial year based on current budget estimates’.

The division cannot pinpoint when the operational model for public housing became unsustainable. This is because the division has funded deficits by deferring acquisitions and maintenance and using cash received in advance for long-term programs, along with unspent cash from capital programs. Figure 2B lists the short‑term strategies the division has used to address its financial position.

Figure

2B

Divisional short-term strategies to address financial position

Action to date |

Short-term impact on cash |

Long-term impact on sustainability |

|---|---|---|

Deferring capital construction / acquisition |

Short-term reduction in cash outflows |

Impact on long-term ability to supply accommodation |

Disposal of stock |

Short-term reduction in cash outflows |

Generally, these funds would be reinvested back into capital projects. Instead they are used to subsidise programs and rental operations and this impacts long-term ability to supply accommodation. |

Deferring renewal maintenance and physical improvement expenditure |

Short-term reduction in cash outflows |

Reduces the useful life of existing stock and increases the number of un-tenantable properties. This effects the future supply of accommodation and worsens the maintenance backlog. |

In April 2005, as a part of Budget processes, the Housing Resource Allocation Review was established to review housing assistance. In 2010, this was renamed as the Housing Review Board, and comprised senior officials within DPC, DTF, the Department of Planning and Community Development and DHS.

In its April 2006 report, the board found that the division’s financial position was unsustainable over the forward estimates period, given current policy and revenue settings. The board determined no immediate risk to financial operations as the public housing program was able to be funded using short‑term measures. In its 2007 report, the board noted that the division’s underlying financial position has been deteriorating since 1998–99.

An additional 2007 review commissioned by DTF to look at options for managing public housing stock also highlighted the declining rental income, ageing and diminishing property portfolio and deteriorating financial position of the division. It made a range of recommendations for asset management and investment alternatives.

Despite these reviews, neither the board, the division, nor the government, developed or acted upon any long-term strategies to address the deteriorating financial position. The division is unable to demonstrate any evidence that it pursued alternative operating models to put public housing back on a sustainable footing. DTF, in a March 2012 report to the steering committee for a DHS-wide funding review, acknowledge that the work of the Housing Review Board has not ‘substantively addressed the division’s financial sustainability’.

Financial management and transparency

The division has not reviewed, either recently or over time, the efficiency of its service delivery. This fundamentally compromises the division’s capacity to understand and improve operational efficiency. This is despite previous DTF recommendations to do this, and a $28.6 million increase in divisional administration costs between 2007 and 2011.

The composition of the division’s remaining cash balances and forecast cash flows is also unclear. The division needs better delineation between committed funding, contracted expenditure and cash reserves. For example, although all cash reserves are expected to be exhausted during 2012–13, they could be exhausted earlier due to funding commitments under existing programs. The division does not know exactly when the cash reserves will be exhausted under the current operational model. External consultants, commissioned by the division, are currently investigating this.

Accrued maintenance costs

Due to the continuing operating deficit, there is an increasing, unfunded maintenance liability, which has led to deterioration of the asset base. A 2011 Budget submission by the division, states that substantial maintenance is ‘required to avoid the closure of approximately 10 000 properties’ over the next four years, approximately 14 per cent of the portfolio. The amount requested for portfolio maintenance over a three-year period is $600 million, which does not include anticipated maintenance costs past the three-year period.

Further, the division acknowledges that the full extent of the maintenance liability is unknown because:

- the division has not accounted for, or recognised, the extent to which public housing has been under-maintained as a liability

- property condition data is poor, preventing a more accurate forecast of accrued maintenance across the portfolio.

Excepting the recent Budget submission, the division has not vigorously pursued options to reduce, or remove, this asset liability.

2.4 Strategic direction for public housing

2.4.1 Previous housing policies

Over the past decade, policy guiding the division has focused on the growth of community housing through non-profit housing associations, new builds funded through time-limited Commonwealth funds, and specific redevelopments. The introduction, in 1999, of the prioritised waiting list that, while targeting housing to need, has greatly affected public housing by decreasing its revenue. Figure 2C summarises previous policies.

Figure 2C

Housing policies 2000–2010

Year |

Policy |

Description |

|---|---|---|

2003 |

Strategy for growth in housing for low income Victorians |

This policy aimed to increase the supply of affordable housing through regulated housing associations. This represented a shift away from the traditional model of social housing provision of government being the primary supplier. |

2010 |

Victorian Integrated Housing Strategy |

Under development since 2004, this strategy proposed to increase community housing supply through housing associations, deliver 800 new public housing units and provide better public housing through estate redevelopments. |

The 2010 policy does not articulate the intended target group for public housing or outcomes for this group. Further, while committing to growing housing stock, neither policy addressed the underlying financial non-viability of the public housing portfolio.

2.4.2 Divisional planning

The division has not articulated long-term objectives for public housing. In the absence of any decisive direction, as shown in Figure 2B, the division has used short-term measures to meet policy commitments to increase housing supply. This has only exacerbated the increasing operational deficit. Over the past ten years, the division has also not undertaken any long-term planning to direct the management of public housing. Such planning, considering at least a 10-year period, is particularly important given:

- the fixed nature of the asset base

- the high cost of structural alterations

- the relatively long life span of housing stock, with industry benchmarks at 40years or more for residential housing stock

- long lead times for redevelopments and new builds

- external pressures, such as decreasing housing affordability

- constrained revenue growth from rental income.

This lack of long-term planning hinders decision-making and effective asset management. For example, regional offices visited during the audit, report that their inability to articulate a long-term plan makes prioritising effort and working effectively with stakeholders, such as local councils and tenants, difficult.

For the first time, in 2011–12, the division developed a business plan for its Property and Portfolio Branch. The plan links to overarching DHS and government plans, and sets clear objectives and supporting strategies. The division’s next asset strategy should then provide the practical road map to implement this plan.

2.4.3 The new housing framework

The government is currently developing a housing framework. It aims to provide long‑term future direction for public housing, including intended outcomes and to address current and future housing challenges. To inform the framework, the division plans to release public discussion papers on the challenges facing public housing by April 2012. At March 2012, the division had commenced, but not yet completed work to model the financial impact of policy options being considered or to articulate ways the framework might address the unsustainable operating model. This work is necessary to set realistic parameters for public discussions.

2.4.4 Extracting greater value from the portfolio

Despite long-standing knowledge of public housing’s unsustainable operating model, the division has not adequately explored alternative options to fund public housing. The division has not questioned the role it should play in delivering public housing, compared or benchmarked against other providers, modelled alternative funding approaches, or evaluated outcomes where the division has innovated.

The division’s role compared to other providers

The division’s traditional role is to finance, own and operate the majority of its assets. While this is not inappropriate, the division has not evaluated whether it performs each element efficiently and effectively, or whether benefit can be gained by taking a more flexible approach and contracting out some of these functions. This is despite the 2007 DTF review that recommended a range of alternate approaches the division should explore.

For example, the Defence Housing Association, which provides housing services to defence force personnel, operates with no ongoing grants through a different model—owning and maintaining some properties while constructing, selling and then leasing back others in its portfolio. Although there are clear differences in tenant profile and funding, the Defence Housing Association model shows that different operating models can successfully manage a large housing portfolio. There are other property providers, such as community housing associations and other state housing authorities, against which the division can benchmark its efficiency in tendering and construction, asset maintenance and tenancy management. The division needs to make sure that it meets its service delivery obligations in the most cost‑effective manner.

Mixed redevelopments

The division has trialled alternatives for funding capital works, such as attracting private investment through the mixed redevelopment of existing public housing stock. The division has done this in Kensington and Carlton, with Kensington almost complete. Despite the Kensington redevelopment beginning in 1992, the division has not evaluated the effectiveness of this option or how it might, if more broadly utilised, influence the financial viability of public housing.

Recommendations

The Department of Human Services should:

- develop and apply options to overcome the unsustainable operating model

- assess its operational efficiency and role in public housing

- develop a long-term plan for public housing with clear objectives.

3 Public housing asset management

At a glance

Background

Effective asset management requires long-term planning linked to strategic objectives and whole‑of‑life cycle asset management. Decisions should be based on comprehensive, reliable evidence and, in the case of public housing, should meet community needs.

Conclusion

The Housing and Community Building Division’s asset management approach does not support the legislative objective of providing ‘well-maintained public housing’. There is no current asset management strategy for public housing and past strategies did not clearly link to objectives, properly consider the asset life cycle, or support the division to meet public housing need. The evidence base used to inform decision‑making is incomplete and out-dated. A $17.8 billion property portfolio, housing 127 357 Victorians, requires far more informed, cohesive and comprehensive asset management.

Findings

- Asset management strategies have lacked necessary detail, and the division has not monitored or evaluated performance against asset strategies.

- The division does not apply a strategic approach across the life of the asset base.

- Investment decision criteria are unclear and not understood by regional offices.

- Property condition data are inaccurate and incomplete.

- There is a mismatch between housing stock and tenant need.

- The division can benefit from greater input from regional offices and tenants.

Recommendations

The Department of Human Services should:

- develop a comprehensive asset management strategy and vigorously monitor performance

- at the regional level, capture local knowledge and communicate investment criteria

- update and strengthen property condition data across the portfolio

- apply relevant data and medium- and longer-term forecasts to asset management strategies.

3.1 Introduction

Effective asset management is vital to the success of the public housing portfolio. It should cost-effectively guide service delivery over the life of the asset base. Planning for, and managing, a large asset portfolio requires:

- a strong evidence base to inform decisions and forecast service need

- comprehensive asset management strategies that consider the asset life cycle

- performance measures and monitoring to track progress and identify opportunities for improvement.

3.2 Conclusion

Public housing is an essential part of meeting the legislative objective that ‘every person in Victoria has adequate and appropriate housing at a price within his or her means’. A $17.8 billion property portfolio, that houses 127 357 Victorians, warrants rigorous asset management of the highest standard. The Housing and Community Building Division (the division), of the Department of Human Services (DHS), has much to improve in its management of this valuable asset base.

The division is not following standard asset management principles. Asset strategies are not aligned to overarching plans and objectives, do not articulate and link actions to desired service outcomes, and are not sufficiently evidence-based. The division does not have a current asset management strategy and past strategies have not adequately accounted for asset life cycles or considered ways to achieve greatest value from the portfolio. The division does not compare current stock to its desired portfolio to guide future direction, and does not assess its performance. These significant gaps expose a serious deficit in asset management skills within DHS.

Decisions made in the management of public housing assets affect the lives of tenants, and the ability to meet future public housing need. Such decisions, therefore, require a strong evidence base. However, the division’s evidence base for asset decision-making is inadequate. Property condition data is unreliable, and the division does not adequately forecast service levels in the longer term or effectively obtain input from important stakeholders such as its regional offices and tenants. Better information and performance monitoring may have helped the division identify problems such as the significant maintenance liability and the current mismatch between housing types and tenant needs earlier.

3.3 Asset management principles

Based on Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and publicly available better practice guidance on asset management, a comprehensive asset management strategy should:

- follow an integrated approach—align asset management requirements and service outcomes to overarching plans and objectives

- focus on service delivery—all planning, decisions and reporting should focus on the type and quality of services the community needs

- make evidence-based asset decisions—by relying on rigorous information about the costs, benefits and risks of alternatives across the asset life cycle.

A comprehensive asset management strategy is then supported by:

- an acquisition plan that defines the type and timing of asset requirements and provisioning options, including financing and cash flows, and considers property cycles and market fluctuations

- a maintenance plan that details expected life cycle costs and requirements, regardless of whether they will be met, to enable a better understanding of accrued maintenance liability

- an operations plan that sets out operating policies and the resources required to manage the asset, including a breakdown of administrative costs by business unit

- a vacancy management plan that outlines a strategy to measure and minimise property vacancies

- a disposal and risk management plan.

A comprehensive asset management strategy puts these principles into practice by directing activity and resources in a coherent and justifiable way.

3.4 Public housing asset management

Asset management strategies for public housing should have clear objectives, align with overarching DHS strategies, carefully consider options, and plan activities to achieve optimal service outcomes.

Purpose and direction

The division developed consecutive four-year asset management strategies. One covered the period 2003–04 to 2006–07, and the second from 2007–08 to 2010–11. There was no finalised asset management strategy prior to 2003, and the division is yet to develop a strategy for 2011–12 onwards.

No strategy linked clearly with the DHS asset strategy or detailed what success would look like for the asset portfolio. The strategies do not state desired service outcomes and objectives, meaning the purpose of the asset strategies, and direction for the portfolio is unclear.

Options and stock analysis

Neither of the asset management strategies compares existing stock, broken down by asset type and location, to forecast need over the forward period. The division uses information on tenant profile, location preferences, and housing supply, to inform asset decisions as they arise. However, the division does not apply this information or broader factors like demographic trends, amenity profile, or information on the ability to buy back in a location once an asset is disposed of, to forecast need. The division, therefore, cannot readily identify its desired stock mix and has no ‘gap analysis’ to inform future asset decisions.

The division is not using its asset management strategies to identify and articulate an evidence-based approach for where and how it will focus its efforts to maximise benefit. The past strategies do not contain assessments of options to extract greater value from the portfolio. Assets are not categorised by redevelopment potential or other strategic benefits, and neither strategy identifies, or analyses, possible alternative options for funding capital and operating costs. A comprehensive asset management strategy considers more than just a business-as-usual approach and details options for achieving the portfolio objectives, including evaluation of service outcomes, costs, benefits and risks for each option.

Life cycle approach

The two asset management strategies do not apply a systematic and comprehensive life cycle approach across the housing portfolio. DTF’s 1994 Asset Management Series establishes the requirement to prepare five-year forward asset strategies covering acquisition, maintenance, upgrades and disposal, together with capital and operating costs. The 2003 asset management strategy does not address these phases of the asset life cycle or detail capital and operating costs across the portfolio. The 2007 asset management strategy has sections on most of these phases, but has no information on the maintenance program or operating costs, and details only one year of the acquisition program.

The division’s asset management strategies do not detail expected life cycle costs or requirements such as cyclical upgrades of bathrooms and kitchens. It is not possible to determine from the strategies:

- the useful life of an asset, or what the division expects this to be

- projected time lines and costs of planned upgrades for each asset type

- the costs and types of maintenance, whether for planned, responsive or preventive maintenance.

This lack of detail prevents the division from understanding and meeting the needs of the portfolio across its life cycle.

Acquisition

Neither asset strategy has an assessment of the various methods of acquisition, such as the costs and benefits of spot purchase, leasing, construction, redevelopment, joint ventures or land swaps with other government agencies. There is also no explanation of cash flow management.

The method of acquiring properties is important as it determines the financing model and delivery time. For example, new constructions and redevelopments require substantial lead times compared with leasing or spot purchases, and cash flows for each acquisition method are different. Acquisition should also consider property cycles and market fluctuations, and neither strategy accounts for this.

Asset intent and disposal

The strategies do not give a clear assessment of portfolio condition, by classifying or prioritising properties across the public housing portfolio to support strategic decision‑making. Good asset management identifies and groups properties with ideal attributes, such as proximity to public transport, which the division could then manage differently to lower quality stock of less strategic importance to the portfolio.

The division does have a property rating system, the Housing Assistance Lease Plan (HALP). However, divisional asset management strategies do not apply HALP rating information at a system level to direct asset planning in the public housing portfolio.

Vacancy management

Management of vacant properties, even for a few days or a week, is prudent as this ‘down’ time adds up across a large portfolio such as public housing. While the division has effective vacancy management practices and low vacancy rates, these are not reflected in the asset management strategies or plans to measure and minimise property vacancy. Further, as an efficiency measure, management of vacancies across the portfolio could be linked to, and scheduled with, planned maintenance, revaluations and property condition audits whenever possible.

Evaluation and performance monitoring

The division does not assess or monitor its asset management strategies. Other than reference to tenant satisfaction surveys, the division does not include performance indicators within its asset management strategies. The 2003 asset management strategy acknowledges that ‘the model does not currently provide assessment of the range of factors appropriate to major improvement proposals or long-term maintenance regimes’. It goes on to state that ‘the financial model should be reviewed and modified to provide total asset management financial assessments’. The 2007 strategy does not refer to the suggested review and incorporates no performance measures, financial or otherwise.

It is therefore unclear:

- whether planned decisions were implemented

- whether available resources were used effectively or efficiently

- how the portfolio is performing financially, such as the number of tenants housed as a proportion of total asset value

- whether the division is achieving good return on investment, given the timing and method of acquisition

- if there are opportunities for improvement.

The performance of a $17.8 billion property portfolio deserves regular and careful monitoring. This lack of evaluation is particularly concerning given the financial pressures within the portfolio, the long lead times needed to create change and the importance of being able to account for the performance of this crucial public service.

3.5 Evidence-based decision-making

Good public housing asset management requires a reliable evidence base using accurate, up-to-date information on asset condition and performance as well as an understanding of external housing pressures and demand.

Investment decision-making

In 2011, the division established the Investment Review Committee (IRC) to assess, prioritise, and standardise a process for proposed major redevelopments and new builds across public housing. Before then, the division did not have a clear investment framework to prioritise its constrained discretionary funding for capital works.

An external consultant chairs the IRC, and the committee consists of senior divisional staff. The IRC has developed a clear, stepped process to appraise project development activity on a case-by-case basis, and make recommendations to the Director of Housing. This is an improvement on past practice. However, the IRC has not documented the criteria on which it bases its recommendations and staff at the four audited regional offices do not understand the decision-making process. Regional staff report that this makes it difficult to plan at the regional level and assist head office to identify redevelopment opportunities. Specifically, it is unclear how the IRC:

- assesses each proposal’s value-for-money, and what criteria are used

- established, and uses non-financial criteria and weighting, and what criteria are used

- established, and uses cost and profit benchmarks.

Property condition data

The effective management of public housing assets requires accurate property condition data to target funding appropriately. This data should capture both asset condition and maintenance costs to inform the asset management strategy and correctly prioritise works across the portfolio.

Regional field officers should undertake property condition audits (PCAs) every three years to provide an estimate of property condition. The division uses PCA data to determine annual maintenance and capital works. In a 2011 Budget submission, the division states that ‘there is insufficient operational funding to maintain accurate data on the entire portfolio at any point in time’. Reviews, both internal and commissioned, undertaken since 2007, have identified a number of issues with the PCA system, resulting in inaccurate and unreliable data. For example, if maintenance costs for a property are set at $20 000, and only $12 000 of the repairs are completed, the maintenance costs recorded against the property are reset at $0, despite outstanding works remaining. Other problems include that:

- in 2011, 14 321 dwellings (24.9 per cent) had not been assessed for over three years, with 2 400 of these not inspected for over five years, despite divisional policy to assess all properties at least three-yearly

- field officers have inconsistent skills, experience and methods.

A 2011 PCA pilot audit, aimed at better understanding the integrity of current PCA data, found further limitations:

The division also estimates that, due to limitations within the PCA system, maintenance costs of $298 million across the portfolio are, on average, understated by 138 per cent for each property.

- data focuses on the three years following the inspections, with work after that period often uncosted

- inaccurate costing of work within the three-year period, with maintenance costs for over half the audited properties varying by more than 100 per cent from the external expert estimate.

Asset management service improvement strategy

The division has identified the need to improve its property condition data and, in 2011, developed a service improvement strategy for asset management. The strategy focuses on improving property condition data through a comprehensive audit. This will assist the division to:

- determine the priority, scope and funding required to address the current maintenance backlog and short-term future capital works required

- identify assets that are inefficient to maintain

- establish a one to 30 year property life cycle program for each asset

- determine the annual maintenance and capital funding required to implement an adequate asset management program.

In addition, the division aims to use the updated property condition data as one input of many, including locational attributes and demand information, to assign each property an ‘asset intent’ to classify properties as either ‘hold and improve’, ‘redevelop’ or ‘dispose’. The division will then use this information to inform future asset strategies.

The property condition update will improve decision-making and allow for better asset management and forward planning across the portfolio.

3.5.1 Research and forecasting

Research and analysis into trends influencing public housing demand and supply, and affordable housing in general, is necessary to inform long-term planning. This is particularly important for an asset base that requires long lead times to change due to its fixed locations, high cost to modify, and long life span, with residential properties estimated to have at least a 40-year life. Construction and redevelopment also takes considerable time, which in turn limits the speed of response to changing service need. Figure 3A outlines key factors affecting public housing supply and demand to demonstrate the kinds of information needed to forecast public housing demand.

Figure 3A

Supply and demand pressures on public housing

|

Key information areas |

|---|

|

Location and property type: Locational amenity and attributes, and the structure and size of dwellings in an area, influence the affordability of the private rental market. Shortages of a particular type of dwelling can place pressure on existing public housing stock. |

|

Tenure: Tenure is an important indicator of the availability or proportion of public housing as well as the balance between rental housing stock, stock that is owned and stock that is being purchased within a particular area or region. |

|

Low priced rental stock and residential development: Tracking trends in rental stock and residential development helps to monitor housing demand and future supply. |

|

Land supply: Shortages of land for new residential development can significantly affect the availability and pricing of dwellings in an area, increasing pressure on public housing. |

|

Demographic data: The age of the population influences household formation and, with population size, housing need. There are important age ‘cohort’ effects in relation to tenure preference and housing demand as well as vulnerability and the likelihood of public housing need. |

|

Household formation: Increasing household formation rates means that there will be a steady demand for dwellings (as the number of households grows) even in areas where there will be no overall population growth. |

|

Housing stress: Housing stress refers to the impact of high housing costs on low and moderate income households. Housing stress refers to ‘households in the bottom 40 per cent of income distribution paying more than 30 per cent of their gross household income on housing costs’. Increasing housing stress places pressure on public housing. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Matching housing stock to tenant need

The division combines public housing waiting list data, by local government area, with data on affordable housing to determine localised demand. An indicator of supply is determined by combining public housing allocations with affordable private rentals in the area. The resulting Composite Needs Distribution gives a relative need for public housing by location and bedroom number across the state, and assists in asset planning over the medium term. It cannot, by itself, be used to model future public housing stock requirements over the longer term. Partly for this reason, a significant mismatch now exists between public housing stock and the needs of current and future tenants.

The 2010 Victorian Parliamentary Inquiry into the adequacy and future directions of public housing in Victoria found that ‘while the need for more stock suitable for single person households has long been acknowledged, this has not been supported by well‑developed modelling which provides an indication of how many properties are required to meet the needs of this tenant group’.

The tenant profile of public housing has changed substantially over time. Large estates, built in the 1960s, were intended for working families on low to moderate incomes as a transitional measure before moving into private housing. Public housing now serves an increasing proportion of elderly, single and economically and socially disadvantaged tenants. The need for one-bedroom dwellings has increased as the need for larger dwellings has decreased. Bigger properties have larger operating expenses and, given modern density allowances, underutilised sites represent a missed opportunity.

Figure 3B shows the mismatch between public housing stock, and demand as reflected by the public housing waiting list. As shown, it would require almost 100 per cent turnover of households in one-bedroom properties to meet waiting list demand, compared to only 25 per cent for three-bedroom properties.

Figure 3B

Public housing stock and waiting lists by bedroom size as at 30 June 2011

Source: Victorian Auditor-Generals Office based on Department of Human Services data.

The division has recently undertaken analysis of housing trends and stress, through:

- mapping Australian Bureau of Statistics data on the circumstances of all Victorians within the home ownership, private, rental, and social housing segments, and those that are homeless

- identifying undesirable and acceptable housing circumstances, and events that may result in movement from one to the other, for example factors such as level of housing stress and employment status

- mapping the Victorian population against undesirable housing circumstances to identify population and target groups for potential policy interventions

- identifying barriers preventing Victorians from achieving acceptable circumstances.

This information assists the division to understand factors that create public housing need, and therefore assists in identifying the target group for public housing and developing ways to support people to move into, or stay in private housing arrangements. The 2011 overarching DHS asset management strategy states that, ‘...long-term program planning....should reflect the changing profile of people in housing need’. Additional analysis will have to build on this initial work to forecast service demand into the future for those who do need public housing assistance.

3.5.2 Stakeholder input

Regional input

Regional input into asset planning is not consistently captured, meaning local knowledge is not always leveraged. Asset planning is centralised, with the division’s central office developing annual work plans and budgets for the regional offices. Regions then review these work plans and can suggest changes. The four audited regions, covering metropolitan and rural areas, report differing extents to which they can influence their respective work plans, with one region not actively participating in the planning process at all. Each region varies in regards to whether they have a dedicated position for asset management.

The division’s central office recognises the need to improve interaction with, and consistency in, asset management within regions to better capture local knowledge and increase regional participation in asset management.

Tenant participation

Under the Housing Act 1983, government is required to:

- seek the participation of tenants and other community groups in the management of public housing

- promote consultation on major policy issues with all persons and groups of persons involved in housing.

The division’s tenant participation framework aims to increase opportunities for public tenants to contribute to decisions affecting them. Activities include:

- funding the Victorian Public Tenants Association, the peak body for public tenants and tenant groups

- funding volunteer public tenants groups under the Tenants Group Program

- tenant satisfaction surveys

- statewide and regional tenant forums

- local housing office meetings.

Despite these initiatives, our consultation with public housing tenants identified that tenants do not feel genuinely engaged or consulted on public housing management or policy issues. Rather, they perceive current participation as ‘tokenistic’. In three regions, regional tenant forums are not operating. Public housing tenants report that while there are many avenues for input, they are not coordinated to provide a unified tenant view. Tenants also feel that the division does not provide sufficient, timely information, particularly concerning the mix of community, private and public housing that is occurring on redeveloped estates.

Recommendations

The Department of Human Services should:

- develop a comprehensive asset management strategy and vigorously monitor performance

- at the regional level, capture local knowledge and communicate investment criteria

- update and strengthen property condition data across the portfolio

- apply relevant data and medium- and longer-term forecasts to asset management strategies.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Human Services with a request for submissions or comments.

The submission and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

Auditor-General’s response to the Department of Human Services – recommendation 2

As referenced at 2.3.1 of this report, VAGO is aware of the review of the Housing and Community Building Division’s cash flows by external consultants. VAGO is also aware of the current base review of the broader Department of Human Services by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF).

DTF note, in a March 2012 report to the Steering Committee for the base review, that they have made recommendations to the division to review and improve efficiencies ‘for several years’ and that the need to do this is now ‘urgent’. The intent of the recommendation is that a specific assessment of the efficiency and role of the Housing and Community Building Division in delivering public housing is needed, given the increase in administration costs and clear gaps in asset management practice. It is not evident that either the external consultant review, or the broader DTF base review, will focus on this.