Administration of Parole

Overview

The audit examined whether parole is being administered effectively to achieve its intended outcomes. In particular, it examined the parole system in the wake of the reforms arising from the review of the parole system conducted by former High Court Justice Ian Callinan.

The audit found that the reforms appropriately responded to the Callinan review's recommendations, and that the operation of the parole system has improved. The Adult Parole Board is now better resourced and informed, and parole officers are better trained and supported.

However, shortcomings in the available data and insufficient performance monitoring in the past mean that it has been difficult to quantify the benefits of the parole system. It is important that the Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) fully implements its parole reform evaluation framework so that these benefits can be better understood and any weaknesses can be identified. It is also important that DJR ensure that all systemic barriers preventing suitable prisoners from receiving parole are removed so that these prisoners can receive the full benefits of the parole system reforms.

Administration of Parole: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2016

PP No 127, Session 2014-16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Administration of Parole.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

10 February 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Audit team Dallas Mischkulnig and Kristopher Waring—Engagement Leaders Matthew Irons—Team Leader Vicky Delgos—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Andrew Evans |

Parole has been a controversial issue in Victoria in recent years, with a number of high-profile crimes committed by parolees. It is not well understood that the primary purpose of the parole system is to increase community safety. The parole system aims to do this by providing support and supervision to assist prisoners to reintegrate into the community. Almost all prisoners will be released at some stage, and the alternative to parole is straight release into the community, without support or supervision.

There are three key agencies involved in Victoria's parole system. The Adult Parole Board (APB) is ultimately responsible for granting and cancelling parole, as well as overseeing parolee progress in the community. The Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) has a range of responsibilities such as preparing prisoners for parole, informing APB about prisoners' suitability for parole and supervising parolees in the community. Victoria Police also plays an integral role in the system by informing DJR and the APB when it detects breaches of parole and enforcing decisions made by the APB to cancel parole.

In 2013, former High Court Justice Ian Callinan reviewed Victoria's parole system. His findings included that the APB required reform, that there was insufficient information sharing between agencies and that the case loads of community corrections officers were too high.

A significant reform program followed, with investment of $84 million over four years. Our audit found that this has resulted in a better informed and resourced APB, better trained and supported parole officers and better information sharing between the APB and Victoria Police regarding parolee behaviour. Parolee risk to the community is now enshrined in legislation as the key consideration in APB decision-making.

However, there are still challenges that remain. There are now fewer prisoners who receive parole, and as a result, more offenders are not receiving the support and supervision during reintegration into the community that the parole system offers. In addition, inadequate information and communications technology (ICT) systems at DJR increase the risk of error and cause inefficiencies. This is because staff have to collate information from a number of databases when compiling advice for the APB or conducting data analysis. Importantly, these inadequate ICT systems hinder the monitoring and evaluation of the impact of these changes on the parole system. Accurate monitoring and evaluation is vital to enable agencies to identify areas for improvement and to determine the extent to which the parole system is increasing community safety.

As outlined in my Annual Plan 2015–16, I intend to follow this audit with one on the management of offenders on community corrections orders (CCO). I hope to find that agencies are working together to respond to emerging challenges in the CCO system as well as they have done for the parole system.

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General

February 2016

Audit summary

Parole is the conditional release of prisoners to serve the remainder of their prison sentence in the community. It is intended to provide offenders with support and supervision while they reintegrate into the community.

While the overarching purpose of the parole system is to increase community safety, there will always be the risk that some parolees will commit further offences while in the community. This risk is managed through monitoring and supervision by responsible authorities. The parole system also acts as an incentive for good behaviour in prison and encourages participation in in-prison programs. The alternative to parole is prisoners being released from prison with no support or supervision.

The parole system in Victoria has received significant media and public attention in recent years because of concerns about serious crimes committed by parolees. In 2013, the Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) began planning for the Parole System Reform Program (PSRP) in response to a government-commissioned review conducted by former High Court Justice Ian Callinan, which found a number of significant shortcomings with the system. DJR received funding of $84.1 million to be spent over the four years between 2014–15 and 2017–18 to implement the reforms.

The PSRP consisted of 13 individual projects that focused on several important areas of the parole system, including assessing prisoner eligibility for programs, in-prison preparation for parole, parole officer capacity and capability, and information and communications technology (ICT) systems. The program was planned between September 2013 and March 2014, and implementation was largely completed by April 2015. Some ICT components are still being implemented.

DJR, the Adult Parole Board (APB) and Victoria Police are the key agencies responsible for the parole system. This audit assessed the administration of the parole system following the PSRP. It examined the preparation of prisoners for parole and the management of parolees in the community. It also assessed the planning and implementation of the PSRP against its objectives and evaluated whether it appropriately responded to the recommendations in the Callinan review.

Conclusions

Several years of intense focus and reform have improved the administration of the parole system in Victoria. However, it is still too early to fully assess the impacts of the PSRP on community safety outcomes. Limitations in the data currently available mean that there are significant barriers to evaluating the outcomes of the parole system in general.

There is now a stronger focus on reducing the risk that parolees will commit further serious offences while on parole. Through the PSRP, DJR, the APB and Victoria Police systematically engaged with key issues and implemented reforms that have led to a general tightening of parole conditions—particularly for serious violent or sexual offenders. The APB is now better resourced and informed, and parole officers are better trained and supported.

However, some challenges remain that have ongoing implications for long-term community safety and the management of offenders. Fewer prisoners are being released on parole. Those who are not released on parole are not subject to parole officer supervision upon release and cannot be ordered to undertake the community-based programs offered by DJR and service providers. DJR needs to ensure that any barriers preventing otherwise suitable and willing prisoners from applying for parole are removed.

In addition, DJR's current ICT infrastructure is outdated and complex, which causes inefficiencies, increases the risk of error and inhibits effective information sharing and evaluation. Some data is either not available or not used as effectively as possible to drive improvements. DJR needs to continue monitoring and improving the parole system and to implement its evaluation framework to ensure that the long-term impacts of parole reforms are understood.

Findings

Preparation for parole

The PSRP has improved the operations of the APB. Board members now have sufficient time to consider each case, and improved ICT systems allow easier access to information and the improved recording of decisions made.

Prisoners now have to apply for parole rather than being automatically considered by the APB. This has been a positive step, but DJR needs to further review its data to ensure that prisoners are not missing out because they are unable to navigate the application process.

The APB is now better informed about prisoner suitability for parole through the new parole suitability assessment process. However, easier access to information for parole officers, through the implementation of an integrated offender information system, would improve the efficiency of the process.

DJR now has a requirement that all serious violent or sexual offenders are screened and undertake programs in prison, when required. However, it does not monitor how many serious violent offenders have not completed the required offending behaviour programs (OBP) by their earliest eligibility date for parole. The APB is unlikely to grant a prisoner parole unless they have completed all required OBPs. DJR has targets for the provision of OBPs, however, it is achieving these less than half the time.

Management of offenders on parole

Parolee case management changed significantly as a result of the PSRP. There is now a dedicated parole stream that supervises parolees and a new staffing structure.

Parole officers received appropriate training on topics such as the new risk‑assessment tool, case management and different offender groups. Their case loads are now more manageable. This is in contrast to the court stream, where case loads are increasing in number and complexity. Parole case loads are monitored at an office and operational-region level, but this information is not considered or collated centrally. This means that parole officer case loads vary significantly between different offices and regions. It is important for DJR to monitor this centrally so that it can appropriately allocate staff.

Information sharing between agencies has improved and there are now clear protocols for communication around breaches of parole. However, information sharing between DJR and community-based service providers and clinicians could be improved. Service providers and clinicians do not always have access to information such as detailed assessments and clinical information collected in prison, which inhibits their ability to support parolees. Parole officers also do not always receive appropriate information from service providers and clinicians, which hinders their ability to properly supervise parolees and inform the APB.

DJR now provides OBPs to parolees in the community as well as in prison. However, there is no evidence that DJR monitors wait times for OBPs in the community or that risk or therapeutic timing are considered when prioritising access to programs for parolees in the community.

Parole System Reform Program

The PSRP was generally well planned and implemented but did have some shortcomings. DJR did not have adequate central oversight of budgets during the implementation of the PSRP. While there was an underspend in 2014–15 across the program, some projects ran over budget. DJR will need to manage this to ensure that all projects are delivered within the overall PSRP budget over the remaining three years. While DJR consulted with key stakeholders, there was limited consultation with secondary stakeholders.

All of the Callinan review recommendations were considered and responded to. The majority of responses either fully achieved the intention of the original recommendation or were appropriately modified based on sound evidence and consultation.

The majority of the non-ICT projects within the PSRP were completed on time, while the majority of the ICT projects are either delayed or not fully complete. One of the primary reasons for this is the complexity and age of DJR's current ICT infrastructure.

An evaluation framework has been developed, which DJR plans to implement over the next four years. While the framework needs some further development, it has the potential to assess the effectiveness of the PSRP. This would be a significant improvement on current performance monitoring which does not monitor the parole system against its objectives.

Recommendations

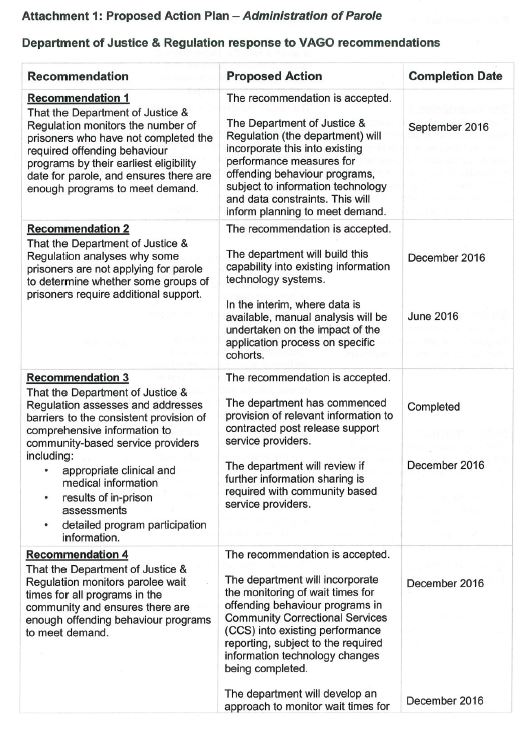

That the Department of Justice & Regulation:

- monitors the number of prisoners who have not completed the required offending behaviour programs by their earliest eligibility date for parole, and ensures there are enough programs to meet demand

- analyses why some prisoners are not applying for parole to determine whether some groups of prisoners require additional support

- assesses and addresses barriers to the consistent provision of comprehensive information to community-based service providers including:

- appropriate clinical and medical information

- results of in-prison assessments

- detailed program participation information

- monitors parolee wait times for all programs in the community and ensures there are enough offending behaviour programs to meet demand

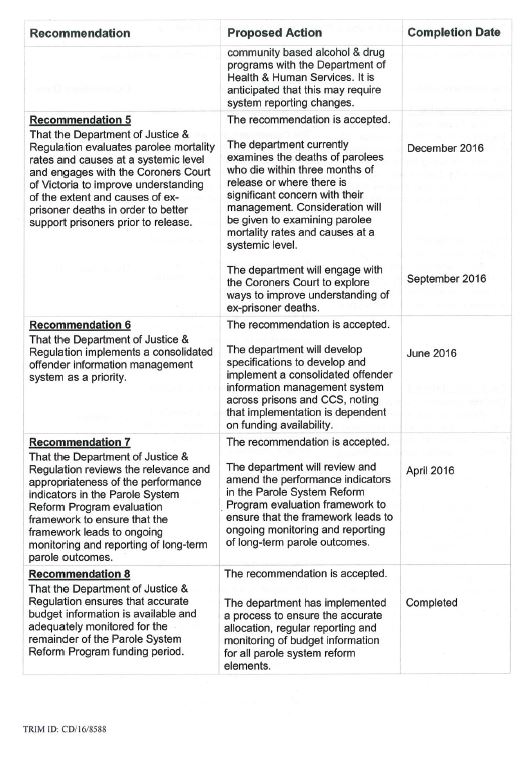

- evaluates parolee mortality rates and causes at a systemic level and engages with the Coroners Court of Victoria to improve understanding of the extent and causes of ex-prisoner deaths in order to better support prisoners prior to release

- implements an integrated offender information system as a priority

- reviews the relevance and appropriateness of the performance indicators in the Parole System Reform Program evaluation framework to ensure that the framework leads to ongoing monitoring and reporting of long-term parole outcomes

- ensures that accurate budget information is available and adequately monitored for the remainder of the Parole System Reform Program funding period.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Justice & Regulation, the Adult Parole Board and Victoria Police throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix D.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Parole is the conditional release of prisoners to serve the remainder of their prison sentence in the community. Parole is intended to provide an offender with support and supervision while they reintegrate into the community.

The overarching purpose of the parole system is to increase community safety, but there will always be the risk that some parolees will reoffend while in the community. This risk is managed through monitoring and supervision by responsible authorities. The parole system also acts as an incentive for good behaviour in prison and encourages participation in in-prison programs. The alternative to parole is prisoners being released from prison with no support or supervision.

While there is no equivalent data from Victoria, a 2014 New South Wales study found parolees were less likely to commit new offences than prisoners who were released straight from prison into the community. It also found that those who did reoffend took longer to do so and committed fewer new offences.

1.2 Parole reform in Victoria

1.2.1 2011–12 reviews of parole

Over the past five years in Victoria, the parole system has attracted significant scrutiny because of community concerns about serious offences committed by parolees. In 2011, media reports suggested that a number of offenders had committed murder while on parole. In response, the Secretary of the Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) requested that Professor James Ogloff and the Office of Correctional Services Review (OCSR) review alleged cases of murder by parolees.

At the same time, the Attorney-General requested that the Sentencing Advisory Council (SAC) review the administrative and legislative framework governing the parole system. The Ogloff and OCSR review was completed in 2011 and the SAC review in 2012. They found a number of significant issues with parole, including:

- poor communication between agencies

- insufficient management of parolees based on their risk

- a lack of access to programs in the community for parolees

- a lack of appropriate guidance around decision-making for members of the Adult Parole Board (APB).

There were a number of changes implemented in response to the reviews, including modifying the way the APB considers risk when making decisions and the processes for reviewing parole decisions.

1.2.2 2013 Callinan review of parole

Following a high-profile murder by a parolee in September 2012, the government requested former High Court Justice Ian Callinan to conduct another review of the parole system. The Callinan review raised a number of significant issues with the parole system and made 23 recommendations for its improvement. Some of these built on recommendations from previous reviews and some were new. The report's key findings included that:

- the administration of the APB required significant reform and the workload of the APB was 'intolerably heavy'

- the risk-assessment tool used in the corrections system required replacing

- there was no separate classification for the highest-risk parolees to allow for appropriate management

- the APB had limited access to some information such as Victoria Police intelligence

- the staffing structures for community corrections officers were inadequate to attract and retain personnel

- case loads for community corrections officers were too high.

1.2.3 Action following reviews

All three reviews prompted a range of legislative reforms during 2012−13 and 2013−14. Some of these reforms included:

- a second tier of review for parole decisions relating to certain serious offenders

- making the safety and protection of the community a paramount consideration in all parole decisions

- making breach of parole a new offence.

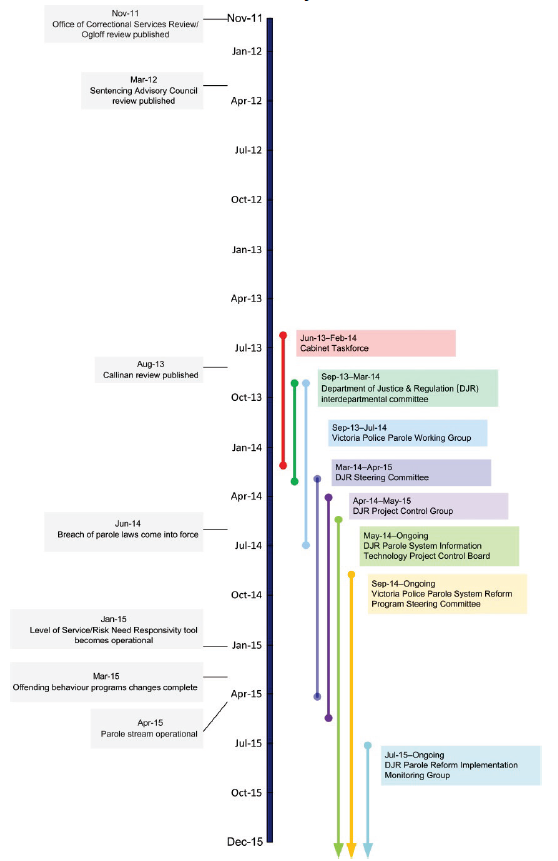

On behalf of the government, DJR implemented the recommendations from all three reviews. To address the Callinan review's recommendations, DJR received $84.1 million in funding over four years. It undertook 13 projects focusing on different components of the parole and broader corrections systems. Five of these projects were ICT projects designed to support reforms to the overall parole system.

The full suite of reforms is known as the Parole System Reform Program (PSRP). Appendix A provides an overview of the time lines of these parole reforms and some of the key changes implemented during the PSRP, as well as a summary of the operational periods of key oversight bodies.

1.3 The parole system now

Under current legislation and policy, unless the courts impose a combined imprisonment and community corrections order (CCO), the only alternative to parole is to release prisoners straight into the community at the end of their sentence, with no supervision or support.

There are three key agencies involved in the adult parole system. DJR and Victoria Police oversee the administration of parole, and the APB decides whether prisoners should be granted parole. In addition, non-government service providers in the community provide a wide range of services to support parolees.

1.3.1 Parole eligibility and conditions

Planning for parole begins when a prisoner first enters the prison system. Upon entry, all prisoners undergo an assessment to determine their risk of reoffending and to identify appropriate in-prison programs.

As they approach the end of their non-parole period, prisoners may apply to the APB for consideration of parole. DJR parole officers complete a parole suitability assessment. Parole officers provide this to the APB to inform it about key issues, such as the completion of programs, behaviour in prison and proposed accommodation in the community. The APB then decides whether to grant parole and imposes conditions on offenders.

To be eligible for parole, offenders must receive a prison sentence longer than 12 months that includes a court-imposed non-parole period, and must have served that non-parole period in prison. Prior to 1 March 2015, all eligible prisoners were considered for parole by the APB of its own accord. Since that date, only prisoners who apply to the APB are considered. Prisoners may choose not to apply for parole and instead serve their full sentence in prison.

This change, as well as others such as more stringent requirements before the APB is likely to deem prisoners suitable for parole, has meant that fewer prisoners now receive parole. As Figure 1A shows, the number of prisoners released on parole as a percentage of the total number eligible has declined by 27 per cent since 2012–13, while at the same time the percentage of those completing their sentence and being released straight into the community has increased nearly five-fold.

Figure 1A

Prisoners released on parole as a percentage of total eligible

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Prisoners |

% of all prisoners |

Prisoners |

% of all prisoners |

Prisoners |

% of all prisoners |

|

Releases on parole |

1 975 |

93 |

1 314 |

78 |

1 201 |

66 |

Straight releases into the community |

160 |

7 |

365 |

22 |

620 |

34 |

Total eligible for parole |

2 135 |

100 |

1 679 |

100 |

1 821 |

100 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on figures provided by the Department of Justice & Regulation.

Over this period, the percentage of those not eligible for parole has also increased. In 2012−13, 68 per cent of offenders being released were not eligible for parole. In 2014−15, this figure had increased to 80 per cent. Analysis by DJR shows this is mainly because more people are:

- being released after a period of remand rather than a sentenced term of imprisonment

- receiving prison sentences that do not allow for parole, such as those under 12 months in total

- receiving combined imprisonment and CCO sentences.

These figures should be considered in the context of an increasing prisoner population and, therefore, an increasing number of offenders being released from prison—from 6 608 releases in 2012–13 to 9 010 releases in 2014–15.

APB decision-making

The APB considers a range of factors when deciding whether to grant parole, with community safety the paramount consideration. Since 2012–13 the APB has increasingly denied parole to prisoners who would otherwise have been released—from 425 times in 2012–13 to 841 times in 2014–15. The APB may deny parole to the same prisoner more than once. The APB can also choose to defer making a decision pending further information, such as the immigration status of a prisoner, or the prisoner completing an in-prison program.

If the APB decides to grant parole, it must apply a set of mandatory conditions—for example, that an offender must not break any law or leave Victoria without permission. It can also choose to apply a wide range of optional conditions, such as specifying that parolees must reside each night at a specific location or submit to drug testing.

The APB can cancel parole and return an offender to prison at any time. In certain circumstances—for example, if a sex offender commits further sex offences—parole is automatically cancelled. In other circumstances, the APB's decision to cancel parole is discretionary. In 2014–15, the APB cancelled 569 parole orders, which is a decrease compared with the previous two years (761 cancellations in 2013–14 and 930 cancellations in 2012–13). This decrease is in part reflective of the APB granting significantly fewer parole orders since 2012–13.

DJR oversight of parolees

Parole officers monitor parolee behaviour and compliance with parole conditions. If parolees fail to comply with a condition of their parole order, their parole officer is required to address the issue with the parolee and, if deemed necessary, report the parolee to the APB. In some cases the parole officer must notify both Victoria Police and the APB—for example, where the parolee is deemed to pose an imminent risk to the community.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police can also charge parolees with a further offence of 'breach of parole' when a parolee is in breach of a prescribed term or condition of a parole order. The charge comes with potential sentences of up to three months' imprisonment, a fine of up to 30 penalty units ($4 550 at 1 July 2015) or both. According to SAC, in 2014–15 there were 64 people found guilty of breach of parole. Of these, 34 received a sentence of imprisonment.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to examine whether parole is being administered effectively to achieve intended outcomes. To assess this objective, the audit examined whether:

- the implementation of parole reforms was comprehensive, timely and effective

- DJR and Victoria Police effectively support the APB to fulfil its statutory functions.

The audit focus was on DJR, the APB and Victoria Police. It examined the policies, procedures, systems and arrangements established by DJR and Victoria Police to guide and inform parole assessments and decisions, and to supervise and monitor parolees. It also examined information sharing between the agencies and with service providers.

The audit did not consider decision-making by the APB. It also did not include the Youth Parole Board, the Youth Residential Board or Commonwealth parole arrangements.

1.5 Audit method and cost

DJR, the APB and Victoria Police were key sources of information for this audit. The audit team gathered evidence by:

- conducting interviews with and reviewing documents provided by DJR, the APB and Victoria Police

- undertaking visits to DJR regional offices and Victoria Police headquarters

- observing meetings of the APB

- reviewing APB and parolee files.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $460 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the preparation of prisoners for parole and the operations of the APB

- Part 3 examines the management of parolees in the community, including case management and access to community programs

- Part 4 examines the PSRP and performance monitoring of the parole system.

2 Preparation for parole

At a glance

Background

To be granted parole, prisoners must apply to the Adult Parole Board (APB). There is also an expectation that prisoners, especially serious violent or sexual offenders, complete appropriate programs. The role of the Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) is to facilitate this and inform the APB about parole suitability. APB members need to have appropriate support and access to comprehensive information about prisoners to make appropriately informed decisions.

Conclusion

Improvements to processes and systems mean that the APB is better informed and supported to make sound decisions. Prisoners now have to take responsibility for applying for parole. However, DJR needs to ensure that all prisoners receive enough support to apply and can access in-prison programs in a timely way to ensure that no prisoners are unnecessarily prevented from receiving parole.

Findings

- The APB's operations and processes have been improved.

- DJR is now better informing the APB about prisoners' suitability for parole.

- DJR does not monitor how many prisoners have not completed required offending behaviour programs (OBP) after their earliest eligibility date for parole (EED). It is achieving OBP timeliness targets less than half the time.

- DJR successfully implemented a parole application process, however, it does not know whether all prisoners who want to apply are receiving adequate support to do so.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice & Regulation:

- monitors the number of prisoners not completing required OBPs by their EED and ensures prisoners have sufficient access to programs

- analyses prisoner groups not applying for parole and provides appropriate support.

2.1 Introduction

There are a number of important factors in preparing prisoners for parole and facilitating well-informed decision-making by the Adult Parole Board (APB). The Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) needs to provide accurate, timely information to the APB about prisoners, including appropriate recommendations about suitability for parole. APB members need to be able to access this information quickly and easily and have sufficient time for discussion and decision-making. DJR should ensure that all prisoners who are motivated and eligible for parole have access to the system.

2.2 Conclusion

DJR is now better informing the APB about prisoners approaching parole and APB case loads have decreased, allowing members more time to consider parole suitability. Prisoners now have to take responsibility for accessing parole themselves by applying to the APB. The APB therefore does not spend time considering parole for prisoners who do not want it.

However, DJR needs to better understand whether barriers are preventing certain prisoner groups from applying for parole and whether all prisoners have timely access to the in-prison programs that are preconditions of their parole. Otherwise, some prisoners who are motivated and willing to go on parole may be unnecessarily prevented from doing so.

2.3 Adult Parole Board operations

The Parole System Reform Program (PSRP) has improved the operations of the APB. Both the reviews of the parole system by the Sentencing Advisory Council (SAC) and former High Court Justice Ian Callinan, found that the case load of the APB was very high, with little time to consider individual cases. There are now more board members, and each board member considers fewer cases on average per sitting day. As of 31 December 2015, there are 39 members of the board, including four full-time members and a full-time chairperson. This is a large increase from 2011–12 when there were 24 members, only one of whom worked full-time. Case loads have subsequently dropped from an average of 55 matters considered per meeting day in 2011‒12 to 33 in 2014‒15. APB members reported significant improvements in the time they have available to consider each case.

Access to electronic documentation and an electronic decision-recording system has made information easier to navigate and reduced the risk of error. Prior to 2014, each parole hearing required three copies of the master version of each prisoner's file to be manually produced. APB members each separately recorded the decisions made at the hearings, increasing the risk of inconsistent or inaccurate records. The electronic system allows APB members access to the same scanned documentation, and all decisions are centrally recorded in real-time, with members checking to make sure they agree that the recorded decision is correct. DJR and the APB are still working on a full electronic workflow system that should further improve the flow of documentation.

2.4 Parole applications

Since March 2015, prisoners have had to apply for parole to be considered by the APB. Previously the APB considered prisoners' eligibility for parole automatically as they neared the end of their non-parole periods. This change is a positive step, as prisoners have to take responsibility for accessing parole themselves and the APB does not have to spend time considering the suitability of prisoners who do not want to go on parole.

Prison officers are now responsible for guiding prisoners through the parole application process, including ensuring that eligible prisoners apply in a timely manner. It is particularly important that they support prisoners who are eligible for parole but find it difficult to apply. Without support, these prisoners would not have the opportunity to be considered for parole. However, some service providers and legal bodies identified examples where prisoners, particularly those with complex issues such as acquired brain injuries, were not always receiving the support they needed. While DJR monitors the number of prisoners choosing not to apply for parole, it has not yet done the analysis necessary to determine the reasons why they are not applying. This analysis may help determine whether prisoners from certain groups—such as those with complex issues or who do not speak English as a first language—need more assistance applying.

As Figure 2A shows, between March and November 2015, an average of 8 per cent of eligible prisoners did not to apply for parole. This includes both those who may not have received adequate support to apply and those who consciously decided not to apply. If this average continues through to February 2016, approximately 205 prisoners out of 2 450 will not apply and therefore not be considered by the APB for parole over the 12 months.

Figure 2A

Parole

applications between March and November 2015

Eligible prisoners |

Mar |

Apr |

May |

Jun |

Jul |

Aug |

Sep |

Oct |

Nov |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Applying for parole |

148 |

253 |

217 |

135 |

197 |

247 |

191 |

152 |

142 |

1 682 |

Not applying for parole |

12 |

24 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

21 |

11 |

18 |

11 |

154 |

Total |

160 |

277 |

236 |

154 |

216 |

268 |

202 |

170 |

153 |

1 836 |

Per cent not applying |

8 |

9 |

8 |

12 |

9 |

8 |

5 |

11 |

7 |

8 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on figures provided by the Department of Justice & Regulation.

2.5 Parole suitability assessments

In the day-to-day operation of the APB, the parole suitability assessment (PSA) is the most important document. It is the primary source of information APB members use to determine suitability for parole. It is therefore critical that parole officers—who are responsible for completing PSAs—are able to access comprehensive information themselves, have clear guidance on how to correctly complete PSAs and fill them out in line with this guidance and on time.

DJR revised the PSA process as part of the PSRP and introduced new PSAs on 1 April 2015. PSAs contain detailed information about prisoners including:

- their complete parole applications

- intelligence information

- any intervention orders in place

- program assessments and treatment completion reports

- drug test results—either in prison or while on parole

- their social history and information on prison incidents.

There is clear documentation outlining PSA requirements. PSAs reviewed during this audit were of a consistently high standard and contained significant relevant information about prisoners. Members of the APB interviewed during the audit unanimously attested to the comprehensive nature of these assessments. As Figure 2B illustrates, by collating information from various sources, parole officers are able to create holistic suitability assessments for APB members.

Figure 2B

Case study: Parole suitability assessments

|

Parole officers use a wide range of information available to them when completing PSAs. One parole officer reported that while completing a PSA for a prisoner named Steven, she was able to access police intelligence that he had made threats against a community member. Further, checks on the residential address Steven nominated as suitable accommodation for parole was found to have a resident facing charges of possession of stolen goods. The parole officer was able to present this information to the APB and allow them to make an informed decision on Steven's parole application. |

Note: Names have been changed.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Current PSAs are a significant improvement on the previous system used to inform the APB about prisoners. Information was often outdated and not always available when needed, and files were held in hard copy rather than electronically. However, some issues remain—in compiling PSAs, parole officers have to consult at least six different databases to gather information. This is inefficient and onerous and increases the risk of missing information. Some information, such as the status of intervention orders, is difficult to access. DJR is aware of these issues and is working on improving access to information for parole officers.

The APB advised that it does not have any concerns with the timeliness of the assessments it has received to date. As the process began on 1 April 2015, it is too early to determine whether parole officers are achieving the target submission time of five months before a prisoner's earliest date of discharge from prison. However, DJR should monitor this target to ensure that it is achieved in the future.

2.6 In-prison programs

The objective of all in-prison programs is to reduce reoffending by helping offenders to deal with the issues that led to their offending. According to the APB's Parole Manual, if prisoners are unable to complete necessary programs in prison for any reason, the APB would only consider granting parole if the risk to the community was mitigated. In practice, this means that prisoners—particularly serious violent or sexual offenders—who have not completed required programs are unlikely to receive parole. DJR therefore needs to ensure prisoners are able to complete these programs before their earliest eligibility date (EED) for parole so that program completion is not a barrier to them receiving parole.

There are two main categories of prison programs:

- offending behaviour programs (OBP) provided by DJR

- alcohol and other drug (AOD) programs provided by a private contractor.

There is also a category of programs called 'specialised offender assessment and treatment services' specifically for sex offenders or those with a disability.

2.6.1 Offending behaviour programs

The PSRP increased the number of prisoners who are required to complete programs in prison. DJR now has an internal requirement that all serious violent and sexual offenders are screened to determine whether they require programs. Those who do are then assessed for appropriate programs. Offenders who do not complete identified programs are unlikely to be granted parole by the APB.

Screening occurs at the beginning of a prisoner's sentence to ensure they have time to complete the necessary programs before their EED. As DJR does not monitor or know how many prisoners have not completed necessary programs before their EED, it is not able to ensure that prisoners are not missing out on parole because they do not have timely access to programs in prison.

DJR sets some targets about the timeliness of programs for prisoners. These are that it will:

- screen prisoners within eight weeks of referral to determine what assessments are required

- assess prisoners within eight weeks of being screened to determine what their needs are and what programs they would benefit from

- enable prisoners to begin required programs within six months of an assessment being completed.

DJR uses its Corrections Victoria Intervention Management System (CVIMS) to record information about participation in OBPs, including performance against these targets. Between July and September 2015 (Quarter 1, 2015–16), there were 213 prisoners in public prisons who were not screened, not assessed or had not begun OBPs within the target for each stage. As Figure 2C shows, this means that in September less than half of the 371 prisoners requiring OBP services had received them within target time lines. As of 30 September 2015, there were a total of 535 prisoners in public prisons who were beyond the key performance indicator targets waiting for an OBP service of some type. Note that this figure only includes those prisoners with no other issues preventing them from receiving that service, such as outstanding court appeals or significant health issues.

Figure 2C

Performance against targets for offending behaviour programs

at public prisons, July to September 2015

Screening |

Assessment |

Intervention |

Total |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Prisoners meeting target |

78 |

41 |

39 |

158 |

Prisoners not meeting target |

86 |

61 |

66 |

213 |

Total |

164 |

102 |

105 |

371 |

Per cent meeting target |

48 |

40 |

37 |

43 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Justice & Regulation data extracted from CVIMS.

DJR has stated that it set these targets as a way of driving its operational regions and program managers in those regions to take responsibility for program demand as part of its regional service delivery model. However, while performance against these targets is presented at a quarterly regional meeting, there is no evidence of any action to improve performance. Given that DJR does not monitor whether these prisoners are waiting beyond their EED for programs, it is impossible to determine the effect of these delays on eligibility for parole.

Once prisoners begin an OBP, they do generally complete them. According to DJR's data, it achieved completion rates of between 93.5 and 100 per cent every month in 2014–15, meeting its service delivery outcome target of 85 per cent.

CVIMS limitations mean that DJR cannot extract historical data or trends from the database. DJR therefore has to use manual workarounds. Moreover, DJR has to extensively modify the extracted point-in-time data before use, and the guidance around these processes is incomplete and out of date. This increases the risk of error. DJR has begun work to address these issues.

2.6.2 Alcohol and other drug programs

There are a range of AOD programs—from short-duration harm-reduction programs to long-term 'residential' programs. These are provided by an external service provider. Unlike for OBPs, DJR does not require that all serious violent offenders be screened for AOD-program suitability. However, the APB takes into account whether prisoners have completed AOD programs when determining whether to grant parole.

The AOD service provider monitors demand for AOD programs by tracking the number of program places filled. It reports this information to DJR as part of a monthly report that also contains the number of programs delivered and a narrative report for each prison. In addition, DJR receives quarterly reports and an annual report that contain information such as wait lists and psychometric testing of prisoners before and after they undertake AOD programs. Regular monitoring by DJR and the service provider through the monthly, quarterly and yearly reports means that they can quickly respond to and modify programs in response to changing demand. As shown in Figure 2D, AOD programs can be effective.

Figure 2D

Case study: Alcohol and other drug programs

|

Jonathon is a long-term offender who has had 13 prior imprisonments and over 80 criminal convictions. Jonathon's convictions were for possession of stolen goods, firearms and drug offences. These were related to his drug addiction. During his last term in prison, Jonathon completed an intensive AOD program and received individual counselling. In all, he completed 180 hours of AOD treatment. Jonathon's parole officer reported that Jonathon was determined to change his life and was making a concerted effort to not associate with anyone who may have links to drugs. Jonathon also had a parole condition to undertake community work. He expressly asked that he not serve it with other offenders because he did not want to be tempted to use drugs again. Due to Jonathon's positive attitude, his parole officer was able to find Jonathon community work for a not-for-profit organisation one day per week. Regular random drug tests confirmed that Jonathon was drug-free and, at the time of our audit, Jonathon had successfully managed to remain in the community. |

Note: Names have been changed.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice & Regulation:

- monitors the number of prisoners who have not completed the required offending behaviour programs by their earliest eligibility date for parole, and ensures there are enough programs to meet demand

- analyses why some prisoners are not applying for parole to determine whether some groups of prisoners require additional support.

3 Management of offenders on parole

At a glance

Background

Effective monitoring of parolees is important to minimise risk to the community. The Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) is responsible for providing supervision of parolees. Parole officers monitor parolees for compliance with parole conditions and assist them to reintegrate into the community.

Conclusion

It is too early to determine whether the Parole System Reform Program has improved community safety outcomes overall. Parole officers receive more effective support and guidance to allow them to effectively supervise parolees. However, better sharing of prisoner and parolee information with community-based service providers would allow them to more effectively service parolees.

Findings

- Parole officers have appropriate guidance and training.

- DJR could better monitor parole officer case loads centrally.

- There is limited information sharing about parolees with community-based service providers.

- DJR does not monitor the timeliness of access to all programs in the community.

- Parolees and released prisoners are at a much greater risk of dying than the general community.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice & Regulation:

- assesses and addresses barriers to the consistent provision of comprehensive information to community-based service providers

- monitors parolee wait times for programs in the community and ensures there are enough offending behaviour programs to meet demand

- evaluates parolee mortality rates and causes at a systemic level and engages with the Coroners Court to facilitate improved information-sharing.

3.1 Introduction

Supervision by parole officers during the parole period is important. It ensures that offenders are complying with their parole conditions, through regular monitoring. It allows parole officers to assist parolees to reintegrate into society and continue to work on any issues they may have, such as substance abuse. More broadly, effective supervision during an offender's parole period is important to minimise the risk of the parolee to the community. Reoffending is most common in the period immediately after release from prison.

3.2 Conclusion

It is too early to determine whether the Parole System Reform Program (PSRP) has improved community safety outcomes overall. However, there are now fewer parolees convicted of committing serious violent or sexual offences.

The Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) has provided training, guidance and support to ensure that parole officers have the capacity and capability to manage parolees. However, DJR could better monitor case loads of parole offices and officers centrally. Information sharing could be improved through the more comprehensive provision of information to service providers and clinicians in the community. DJR should also better monitor access to community-based programs for parolees.

3.3 Parole officer capacity and capability

It is important that parole officers have the skills required to do their job as well as the time available to effectively supervise parolees. Parole officers have regular interaction with parolees, monitor whether parolees are adhering to parole conditions and ultimately monitor the level of risk a parolee poses to the community.

A parole officer's main duty is to monitor compliance with the conditions set by the Adult Parole Board (APB) in the parole order. At the start of their parole period, parolees have to report to their parole officer twice weekly. The frequency of these appointments decreases with time and satisfactory behaviour.

3.3.1 Parole officer positions

At the time of the review undertaken by former High Court Justice Ian Callinan, community corrections officers and leading community corrections officers managed a mixed case load of around 50 parole and community corrections orders (CCO) each.

With the introduction of the PSRP, DJR separated community corrections into two streams—the parole stream, which manages offenders on parole orders, and the court stream, which manages offenders on CCOs.

It created two new positions in the parole stream and broadened the role of one:

- principal practitioners—supervise and manage parole officers, including oversight of case management

- senior parole officers—principally manage serious violent offenders

- parole officers—principally manage general offenders.

These positions are at a higher classification than the positions in the court stream. In addition, the different levels provide a career progression path for staff. Sex offenders continue to be managed separately by specialist case managers within the parole stream.

3.3.2 Case management review

Case management reviews keep DJR's regional managers informed on the progress of parolees and provide them with the opportunity to supervise parole officers. It is the role of principal practitioners to review case management by parole officers regularly.

DJR also has formal processes for case management. Each office has regular case management review meetings between the parole officer, principal practitioner and the regional general manager. They formally discuss the progress of each parolee. The frequency of these meetings depends on the parolee, but they are held every three months at a minimum. In the selection of files we reviewed, there was evidence that there were regular case management review meetings and that these conversations were documented and kept on a parolee's file.

Figure 3A

Case study: Case management

|

Carlos is on parole for eight months following a string of drug and minor violence convictions. He also has mental health issues and is seeing a number of doctors and adjusting to medication. Carlos has breached curfew once, a condition of his parole, and has told his parole officer he is struggling to adjust to his medication. This breach was reported to the APB, who issued a warning. In response to this incident and to manage the risk to the community, Carlos's parole officer has been reporting regularly to the APB and is seeing Carlos three times per week. Carlos is discussed monthly at DJR case management review meetings. |

Note: Names have been changed.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.3.3 Parole officer capacity

As of 17 July 2015, there were 140.5 full-time equivalent staff members working in the parole stream. Some of these positions were newly created as a result of the PSRP.

A number of experienced staff from the court stream moved over to the parole stream. This has depleted the number of court stream staff available, thereby increasing case loads and work pressures. It has also created challenges for DJR in managing this stream, as the number and complexity of CCOs has increased in recent times.

Parole case load

Adequate and manageable case loads are important, as too many cases can affect the time that parole officers can spend monitoring a parolee and, therefore, the quality of the service. DJR allocated parole staff according to its regional parole projections for 2017‒18.

Case loads are monitored at an office and operational region level, but this is not collated or considered centrally. This limits DJR's ability to understand and respond to changing needs at a local level. There is a risk that some parole officers may become overloaded and unable to properly supervise each parolee.

The number of cases managed varies from between six and seven per officer in four regions to almost 12 per officer in two other regions. During visits to regional community corrections offices, we also found that at the Frankston office, a senior parole officer was managing a caseload of 14 parolees, in Ringwood a senior parole officer was managing seven parolees, and in Ballarat the same position was managing four parolees.

In both Ballarat and Bendigo, parole officers were also managing offenders on CCOs due to the high number of offenders on CCOs and low number of parolees. Both offices reported a CCO case load of between 60 and 90 per officer and that there are now more high-risk offenders receiving CCOs. Staff in both offices advised that they prioritise the supervision of parolees.

While this may be an efficient use of staff resources, it has the potential to have unintended negative consequences for DJR. Maintaining the separation of the CCO and parole streams means that DJR can maintain the benefits yielded by its parole reforms while it works on the CCO stream. On a practical level, it means parole officers are working with two sets of guidelines, creating a risk of error in both streams. DJR has stated that this is a short-term measure, however, if parole case numbers do not increase in these locations, DJR will need to reconsider its longer-term resource allocation.

3.3.4 Parole officer capability

Training

With the creation of the parole stream in April 2015, all parole staff underwent an extensive training program. DJR conducted a learning needs analysis for the new positions created as part of the PSRP. It mapped the essential and optional skills required for each position—essential skills included case management, use of technology and how to manage complex offenders. For principal practitioners, the training also included management and review skills.

Training for all parole staff focused on the essential skills identified by the learning needs analysis. Training included report writing, motivational interactions, offending behaviour programs (OBP), case management and specific information on different offender groups. Training for principal practitioners built on this core training and included giving court evidence, leadership, staff supervision and quality assurance.

Following the completion of formal training, DJR evaluated each stream. Overall, feedback from trainees was positive, with 85 to 95 per cent agreeing that the training was relevant and useful to their job. However, one quarter of senior parole officers did not complete an evaluation form.

While feedback confirmed that the training package was useful, parts of the PSRP were still being developed when training was conducted. Offices visited during the audit conducted their own internal training, which was structured around meeting gaps identified by staff and managers.

DJR's risk-assessment tool

In response to a recommendation made in the Callinan review, DJR replaced its existing risk-assessment tool with a set of tools called the 'Level of Service' tools. The primary tool DJR now uses is called the 'Level of Service/Risk, Need, Responsivity' (LS/RNR) tool.

The Level of Service tools are used by other national and international jurisdictions. They target specific risks that are linked to reoffending, including education/employment, alcohol/drug problems and family/marital issues.

The Level of Service tools are used to determine the risk of reoffending. This information is then used, along with assessments from other tools and consideration of an offender's history, to allocate a priority rating score, from one to three. This priority rating determines the level of case management and guides the amount of intervention a parole officer will provide a parolee. Priority 1 and 2 parolees receive more monitoring and intervention. This approach is in line with current research.

Figure 3B

Case study: Risk-assessment tool

|

George was serving a one-year parole following almost two years in prison for drug and violence charges. This was his third time in prison but his first time on parole. Using the LS/RNR assessment as well as other information, George was categorised as a Priority 2 parolee requiring a higher level of intervention. George's LS/RNR found his risks were:

George worked with his parole officer on a case management plan that addressed the risks from his LS/RNR assessment. George's three goals for parole were to:

George had found full-time employment as a labourer after six months and was aiming to further advance his career in the future. Regular random testing has shown George continues to be substance-free. |

Note: Names have been changed.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The training for DJR's new risk-assessment tool was comprehensive and provided staff with sound information on how to administer and score the LS/RNR.

3.3.5 File review

Maintaining case files is critical to the effective management of a parolee. It allows information on parolees and their compliance to be kept and ensures that this information can be used by others. Parole officers maintain case files for each parolee typically containing:

- the parole order

- copies of LS/RNR tests administered

- results of any random drug testing

- file notes from meetings with parolees and any other service provider

- notes from case management review meetings

- any relevant correspondence, including with the APB.

DJR had a file audit program in place prior to the PSRP. The program ran quarterly and examined both parole and CCO files from all regional offices. We found evidence that findings from file reviews were disseminated to regional offices, action plans were created and regional offices reported on how they had addressed audit issues.

At the time of our audit, DJR had approved a new file audit program and was in the process of completing its first round of audits. We examined this process and found that it included examining case management, adherence to guidelines and file management.

We examined some files while visiting regional offices to check for thoroughness. Overall, parole files examined were well maintained, with all relevant documentation kept on file. Parole files are kept in hard copy, with relevant documents, such as case management notes kept electronically on DJR databases and printed for the hard copy file. This system is time consuming and creates duplication of effort. DJR should examine whether the introduction of an electronic system for parole files would be an appropriate investment.

Through our file review and discussions, parole officers demonstrated an effective understanding of frameworks, policies and procedures to effectively supervise parolees.

3.4 Information sharing

Given that DJR, the APB and Victoria Police all play a part in the parole system, information sharing between the three agencies is vital to ensure that issues with the system as a whole are identified and addressed. For the management of parolees, relevant information is exchanged by the three agencies as well as relevant service providers. Parole officers are required to monitor the behaviour and activities of a parolee and inform the APB of any issues. This means that police members and service providers must, in turn, keep parole officers informed when they come into contact with parolees.

3.4.1 Monitoring offenders on parole

While DJR is primarily responsible for monitoring parolees, Victoria Police can have pertinent information on whether parolees are adhering to the conditions of their parole.

Victoria Police

In July 2014, 'breach of parole' formally became a criminal offence. Prior to this, breaches of parole could result in parolees being returned to prison, but were not a crime in their own right. Victoria Police would communicate breaches to DJR, however, it did not communicate with the APB. DJR informed the APB if it deemed it necessary.

After July 2014, DJR and the APB introduced a clearly documented and defined breach of parole notification process. This includes a memorandum of understanding between Victoria Police and the APB around data-sharing.

Victoria Police is responsible for notifying the APB within 12 hours when it detains a parolee on suspicion of a breach of parole. The APB member then decides whether Victoria Police should release or detain the parolee. Our analysis of Victoria Police's data found that it is generally achieving this deadline, notifying the APB within 12 hours 97 per cent of the time. However, in 2014–15, 14 per cent of the 230 notifications to the APB were unnecessary. One of the most common errors made was for police members to notify the APB when a parolee had committed an offence prior to 1 July 2014, before breach of parole laws formally came into force.

The data held by Victoria Police on notifications to the APB is held manually in a spreadsheet rather than in a controlled system. We found there are a number of issues with the spreadsheet including incorrect dates, which hinders monitoring of its responsibility to the APB. While Victoria Police is using this spreadsheet only until ICT components supporting breach of parole are completed, it would be prudent to update the spreadsheet in the meantime, given that this rollout has been delayed.

There is no evidence that Victoria Police has a process for following up on occasions when it did not achieve targets. Where Victoria Police does not achieve targets, the APB is hindered from being able to act in a timely manner, and parolees may be detained longer than necessary. It would be beneficial for Victoria Police to undertake exception reporting to identify where it may need to improve processes.

We also reviewed information in Victoria Police's Law Enforcement Assistance Program to make sure that parolees were clearly identified when police members undertake name checks. We confirmed Victorian parolees could clearly be identified, however, Commonwealth parolees could not. As Commonwealth parolees are managed by DJR, parole officers should receive information from Victoria Police to determine whether their risk to the community has changed. Notifications for Commonwealth parolees are due to be automated when the remaining ICT components of the breach of parole system are rolled out.

3.4.2 Communication between DJR and other agencies

It is important that there is regular communication across the system between DJR and other agencies, such as Victoria Police and the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS). These agencies are impacted by parole reform and can provide DJR with information to effectively monitor the parole system.

DJR had ongoing communication with Victoria Police at both operational and senior management levels during the PSRP. According to DJR, Victoria Police has been invited to join DJR's current key parole oversight body—the Parole Reform Implementation Monitoring Group. This group is not due to meet again until early 2016, however, Victoria Police's inclusion would ensure ongoing senior-level engagement around parole issues in the future.

DJR has regular communication with DHHS on the three shared areas relevant to the parole system—alcohol and other drugs (AOD), mental health and housing. There is evidence of ongoing communication and work at both a senior and officer level.

3.4.3 Provision of information from DJR to service providers

DJR collects a wide range of information about prisoners when they are incarcerated. This includes information on mental and physical health, alcohol and drug issues and social history. Once released, this information is useful to service providers and clinicians who provide services in the community. These providers deliver a wide range of programs and services including those that focus on alcohol and other drugs, mental health, family and relationships, anger management and accommodation.

At present, DJR does not provide service providers with all the relevant information that it collects while offenders are in prison. Without such information, service providers in the community may have to repeat assessments and may not have all the information they need to appropriately treat and assess parolees.

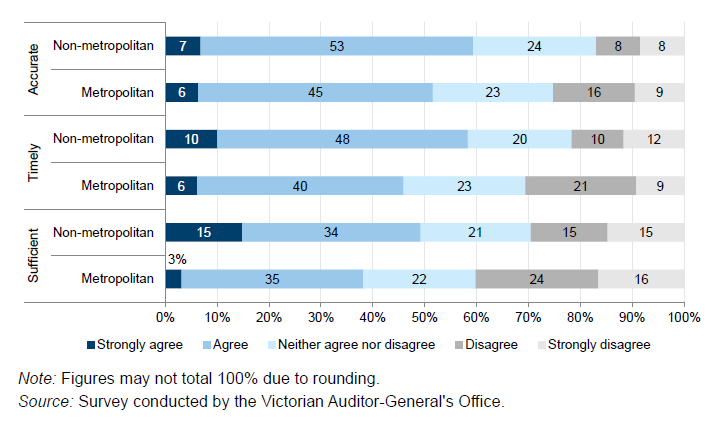

We conducted a survey of 181 service providers in the community and asked them whether they received sufficient information on parolees. Thirty-six per cent of service providers did not believe that information provided by DJR was sufficient, while 27 per cent did not believe it was timely. Figure 3C shows this data broken up into metropolitan and non-metropolitan service providers.

Figure 3C

Sufficiency, timeliness and accuracy of information

provided to service providers

Note: Figures may not total 100% due to rounding.

Source: Survey conducted by the Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Without timely and sufficient information, there is a risk that parolees are not being treated as effectively as possible, which can impact community safety.

DJR now has a process through which parole suitability assessments can be accessed by its contracted service providers. However, this does not include other service providers in the community such as mental health clinicians or some AOD service providers. Moreover, this project does not include the provision of other information such as clinical history or detailed assessments that would aid clinicians and service providers. It would be beneficial for DJR to consider the implications of expanding this further.

3.4.4 Information from service providers to parole officers

Sound communication between service providers and parole officers is important to allow parole officers to assess risk and determine whether parolees need more intervention or case management. Attending and engaging with some service providers, such as counsellors, may be a parole condition.

There are barriers to information sharing between service providers and parole officers. There can be a large number of service providers involved with parolees, as some have complex needs—for example, one parolee identified in our file review had two general practitioners, a psychologist, a psychiatrist, a housing support officer, a reintegration support provider and a drug treatment worker.

Parole officers reported that the quality of information they received from service providers, such as whether parolees were participating in programs or services, depended upon the service provider. Parole officers advised that, where service providers were familiar with the role of DJR and had been involved in the care of other parolees, information provision was better.

Our survey asked service providers whether they had experienced non-attendance or poor behaviour from a parolee, and 64 per cent reported that they had. Of these:

- 69 per cent said they always reported non-attendance or poor behaviour to DJR

- 27 per cent said in certain circumstances, they reported non-attendance or poor behaviour to DJR

- only 4 per cent did not report the behaviour.

While it is positive that very few services providers responded that they did not report inappropriate parolee behaviour, there is an opportunity for DJR to better educate service providers about DJR's role in managing and monitoring parolees.

3.5 Access to programs and services on parole

The majority of parolees are ordered to undergo assessment for treatment (93 per cent) or programs (84 per cent) in the community. Where these assessments result in referrals to programs and services, access to these in a timely way is important to promote sound therapeutic outcomes and to reduce the risk of reoffending.

DJR provides OBPs for parolees. Regional clinicians are responsible for determining when programs are run and also the timing of programs. From file reviews and discussions with parole officers, we found that OBPs were not always offered in a timely manner and some parolees could not access programs until the end of their parole period. There is no guidance for clinicians around the prioritisation of access to programs for parolees based on their risk to the community and intended therapeutic outcomes. Considering factors such as risk and therapeutic outcome as well as a parolee's earliest eligibility date for parole ensures that programs can achieve intended outcomes rather than merely fulfilling parole requirements. Figure 3D illustrates the importance of appropriate timing for undertaking programs in the community.

Since January 2015, DJR has begun collecting data on how long parolees have been waiting for OBPs in the community. It has set a target that parolees should begin OBPs within six months of assessment. DJR is waiting for a full year of data before it evaluates whether it is meeting this target. This evaluation was not available at the time of our report.

Figure 3D

Case study: Offending behaviour programs

|

Tam is on parole for four years after spending 14 years in prison for murder. Since being on parole, Tam has settled back into her family life and is starting to think about future career and study options. Tam's parole officer has been trying to get her into an OBP program, 'Maintaining Change', for almost a year. Tam's parole officer believed that, while she would complete the program before her parole completion date, she would benefit from doing the program soon to assist her to maintain her positive lifestyle. |

Note: Names have been changed.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In addition to OBPs, other programs and services are offered in the community, such as AOD and mental health programs and services. At present, DJR does not monitor wait lists or times for these programs. In particular, DJR is not currently able to monitor wait times for assessment and treatment brokered by a specific third-party DHHS‑funded service provider. As all parolees access AOD programs through this service provider, DJR should work with DHHS to monitor demand to ensure that parolees are able to access AOD programs in line with parole conditions. Finally, DJR does not maintain a centralised database of external providers. Such a database would allow parole officers to identify potential service providers more easily and enable DJR to identify where service gaps exist.

While only indicative, according to our survey, 49 per cent of service providers reported that there are not enough providers to ensure that parolees can access services quickly in their sector. Demand was reported to be higher in metropolitan areas, with 54 per cent of metropolitan respondents reporting shortages, compared with 41 per cent of non‑metropolitan respondents.

3.6 Outcomes of parole in the community

It is still too early to fully determine the impacts of the PSRP on community safety. However, there is some indication that the reforms may have reduced the risk that parolees pose to the community. Since the PSRP began, there has been a decrease in the rate of parolees being convicted of serious violent or sexual offences, from 4.5 per cent in 2013–14 to 1.9 in 2014–15. In total there were 60 parolees convicted of serious violent or sexual offences in 2013–14, and 22 in 2014–15. It should be noted that this indicator counts parolees in the year they were convicted, not the year they committed the offence. It can take several years for parolees' offences to be detected, investigated and prosecuted. Consequently, serious violent or sexual offences committed by parolees today while under the control of the current parole system are unlikely to become evident for several years.

It is difficult to evaluate whether the parole system is increasing community safety overall, as the data does not take into account serious offences committed by prisoners released straight into the community. It is possible that fewer high-risk offenders are being granted parole and are therefore serving their sentence and being released straight into the community.

3.6.1 Parolee mortality rates

Released prisoners, including parolees, are at a much greater risk of dying than others in the community. A study of Victorian prisoners released between 1990 and 1999 found that ex-prisoners were 10 times more likely to die an unnatural death upon release than other community members, while former female prisoners were 27 times more likely to die. The Coroners Court has identified at least 233 ex-prisoner deaths between 2000 and 2013. For those with dates of release recorded, the median time of death was 16 days after release. Overdoses were the cause of the vast majority of the deaths (153), followed by hanging (19 deaths).

Upon our request, DJR was able to determine that 28 parolees died in 2013–14 and 2014–15. Of these, DJR deemed that 16 died of natural causes, two died of unnatural causes and 10 could not be determined. Based on mortality rates in Victoria, it would be expected that there would be approximately three deaths per 1 000 parolees per year. However, in 2014, there were 18 deaths per 1 000 parolees. While only based on one year's data, this suggests that parolees in Victoria also have far higher mortality rates than the general population.

The Office of Correctional Services Review examines the deaths of parolees who die within three months of release, or those where there was significant concern with the management of the parolee. However, it conducts these reviews on a case-by-case basis and does not systematically monitor, evaluate and use the data.

There are several reasons why it would be beneficial for DJR to periodically analyse parolee deaths and for a coroner to be able to systematically determine whether people who have died were prisoners. First, the primary causes of death for ex‑prisoners are often the same causes of reoffending—that is, drug use and poor mental health. Analysis of mortality rates may yield useful information, such as appropriate timing of interventions and the appropriate level of parole officer support. Second, analysis of mortality rates of different groups exiting prison may provide evidence of the benefits of certain systems or processes.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice & Regulation:

- assesses and addresses barriers to the consistent provision of comprehensive information to community-based service providers including:

- appropriate clinical and medical information

- results of in-prison assessments

- detailed program participation information

4 Parole System Reform Program

At a glance

Background

The Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) implemented the Parole System Reform Program (PSRP) in response to the review undertaken by former High Court Justice Ian Callinan. A comprehensive and timely response was crucial given the issues identified and the significant public concern.

Conclusion

The timely implementation of all non-information and communications technology (ICT) projects ensured that Callinan review recommendations were promptly responded to. These responses were appropriate. However, delays to some ICT projects have required interim solutions. Project planning and implementation were generally sound, but monitoring of budgets was inadequate. Further work is required during the implementation of DJR's four-year PSRP evaluation framework to ensure comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the PSRP.

Findings

- The PSRP was well planned and implemented, with some shortcomings.

- DJR's ICT systems are outdated and complex. This contributed to difficulties completing ICT projects. Most non-ICT projects were completed on time.

- DJR has a four-year PSRP evaluation framework that, with some revision, has the potential to assess outcomes when complete. However, there is currently no cohesive performance monitoring framework in place.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice & Regulation:

- implements an integrated offender information system as a priority

- reviews the performance indicators in the PSRP evaluation framework

- produces and monitors accurate budget data for the remaining PSRP funding.

4.1 Introduction