Biosecurity: Livestock

Overview

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources’ (DEDJTR) responses to recent livestock disease events—including a suspected case of foot-and-mouth disease in 2015, a sporadic case of anthrax in 2015, and an outbreak of low pathogenic avian influenza in 2012—have been successful. However, these recent events have been small in scale and have not fully tested the capability and capacity of Victoria’s livestock biosecurity system.

DEDJTR’s capacity to effectively detect, prepare for and respond to an emergency livestock disease outbreak has been weakened by a decline in financial and staff resourcing for core biosecurity functions. This has resulted in a significant drop in surveillance coverage and the increased likelihood of a major disease outbreak going undetected until it has become established. This would increase the scale and complexity of an emergency response. The potentially severe economic and health impacts of such an outbreak in Victoria highlight the urgent need to address this risk.

To DEDJTR’s credit, it has developed plans and commenced work within its own resourcing levels to enhance its livestock disease preparedness. However, these initiatives are incapable of restoring the diminished capacity of Victoria’s livestock biosecurity system.

Biosecurity: Livestock: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2015

PP No 74, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Biosecurity: Livestock.

This audit assessed the effectiveness of Victorian biosecurity practices that relate to livestock disease management and the associated risks to primary production, animal welfare and human health. It focused on exotic livestock diseases, as well as other emergency animal diseases, such as anthrax.

I found that a decline in financial and staff resourcing for core biosecurity functions has weakened the state's capacity to detect, prepare for and respond to emergency livestock disease outbreaks. This increases the potential for a major disease outbreak going undetected until it has become established.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle MBA FCPA

Auditor-General

19 August 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Dallas Mischkulnig—Engagement Leader Chris Badelow—Team Leader Andy Jin—Analyst Susan Stevens—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Steven Vlahos |

Victoria's enviable biosecurity status yields significant benefits for the state. In addition to benefiting public health, it has helped to provide its agricultural industries with access to premium export markets, which has generated significant revenue for the state, with the value of food and fibre exports totalling $11.4 billion in 2013–14.

Despite this advantageous position, exotic and other emergency livestock diseases remain ongoing threats to this advantageous position, the complexity of which is increasing in line with growing international trade and travel, changing agricultural practices and the impact of climate change.

Past outbreaks in other jurisdictions have shown the devastating effect that a large-scale livestock disease outbreak could have here in Victoria. The 2001 foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak in the United Kingdom resulted in economic losses totalling US $12 billion and the slaughter of more than six million sheep and cattle. While Australia is currently free of FMD, the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences estimates that a large scale, multi-state FMD outbreak would result in economic losses totalling $52 billion over a 10-year period.

In this audit I assessed the effectiveness of Victorian biosecurity practices that relate to exotic and other emergency livestock diseases and the associated risks to primary production, animal welfare and human health. The audit focused on the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) as the agency with primary responsibility for livestock biosecurity. It also included the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) in so far as its collaboration with DEDJTR into the management of zoonotic livestock disease threats.

This audit found Victoria's livestock biosecurity system to have been weakened by a decline in financial and staff resourcing. While this is consistent with a wider government initiative to achieve greater resourcing and operational efficiency, in effect it reduced DEDJTR's on-ground capacity to detect an exotic livestock disease outbreak before it spreads and becomes established.

Ultimately these trends place the future of the state's substantial livestock industries and their economic potential at greater risk. Even in the absence of a significant disease outbreak, shortfalls in frontline biosecurity resources can limit the state's ability to demonstrate its livestock health status.

I note that the reduction in biosecurity resourcing is a not a challenge unique to Victoria. For example, Queensland's ongoing review of biosecurity capability has been partly informed by similar resourcing challenges. These circumstances are likely to further increase Victoria's exposure to exotic and other emergency livestock disease threats.

It is therefore critical that biosecurity agencies are able to perform core functions aimed at preventing and preparing for disease outbreaks. There should also be extensive participation in livestock biosecurity prevention and preparedness activities by both the private veterinary sector and livestock industries.

My recommendations reinforce the need for improved disease surveillance capacity and capability, as well as enhanced traceability of sheep and goats throughout the livestock chain. I also recommend that DEDJTR adopts more strategic and systematic approaches to a number of livestock biosecurity functions. Lastly, I recommend that a more collaborative approach be adopted to manage the significant biosecurity risks posed by illegal swill feeding of pigs. I am pleased that these recommendations have been accepted and plans have been put in place to implement them.

I would like to thank the staff of DEDJTR and DHHS for their assistance and cooperation throughout this audit.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

August 2015

Audit Summary

The Intergovernmental Agreement on Biosecurity defines biosecurity as 'the management of risks to the economy, the environment, and the community, of pests and diseases entering, emerging, establishing or spreading'.

Victoria remains free of many pests and diseases. This has provided its agricultural industries with a significant competitive advantage and helped maintain access to premium export markets. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Victoria's food and fibre exports totalled $11.4 billion in 2013–14, while the gross value of agricultural commodities—including meat, milk derived products, eggs, hides, skins and animal fibre—was $12.7 billion.

Biosecurity measures also provide significant public health benefits. This is because a number of animal diseases can be transmitted to humans. These are known as zoonotic diseases.

Despite Victoria's advantageous animal biosecurity status, exotic and other emergency animal diseases remain an ever-present threat to Victoria's livestock industries. The Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences estimates that the impact on Australia's economy of a large scale, multi‑state outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) would be $52 billion over a 10-year period. Of all Australian states and territories, Victoria is considered most at risk of an FMD outbreak due to its temperate climate and intensive livestock production systems.

Conclusions

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources' (DEDJTR) responses to recent livestock disease events—including a suspected case of FMD in 2015, a sporadic case of anthrax in 2015, and an outbreak of low pathogenic avian influenza in 2012—have been successful. Its responses were swift, comprehensive and effective in mitigating risks to primary production, human health and animal welfare.

However, these recent events have been small in scale and have not fully tested the capability and capacity of Victoria's livestock biosecurity system.

DEDJTR's capacity to effectively detect, prepare for and respond to an emergency livestock disease outbreak has been weakened by a decline in financial and staff resourcing for core biosecurity functions. This decline has resulted in a significant drop in surveillance coverage and the increased likelihood of a major disease outbreak going undetected until it has become established. This would increase the scale and complexity of an emergency response. The potentially severe economic and health impacts of such an outbreak in Victoria highlight the urgent need to address this risk.

To DEDJTR's credit, it has developed plans and commenced work within its own resourcing levels to enhance its livestock disease preparedness. However, these initiatives are incapable of restoring the diminished capacity of Victoria's livestock biosecurity system.

Ultimately, the success of any future response to concurrent small scale or medium to large scale outbreaks will depend heavily on input from other agencies, jurisdictions, organisations, private veterinary practitioners and Victoria's livestock industries, as well as reactive funding allocations from government.

Findings

Prevention and early detection

Risk management

DEDJTR's past approach to identifying and assessing livestock disease risks has often been informal and undocumented. This limits assurance that its resources and initiatives have been well targeted. It is now developing a tool to assess animal disease threats to Victoria which, once completed, will be used to prioritise future surveillance and preparedness activities. This tool may impact on future risk management at a business level and to a lesser extent may influence risk management at the state level.

Surveillance

DEDJTR collects livestock disease data from a variety of sources, including its own staff, private veterinarians, farmers, laboratories, knackeries, saleyards and abattoirs. In particular, private veterinarians are central to the success of livestock disease surveillance programs, as they perform the majority of disease investigations in Victoria.

DEDJTR's livestock disease surveillance activities have decreased by 39 per cent since 2011–12 in line with a decline in staffing levels. Over the same period there has been a 7 per cent decline in surveillance investigations by private veterinary practitioners. This constrains the state's capacity to detect livestock diseases at an early stage.

DEDJTR's Significant Disease Investigation program encourages private veterinary practitioners to investigate and report unusual disease events by subsidising a portion of the investigation and laboratory costs. While the program plays an important role in maximising private veterinary participation, its effectiveness has been undermined by weaknesses in its coverage and uptake, as well as the time consuming nature of the investigation process. DEDJTR is taking action to address these issues through its $4.7 million project, Improving Victoria's Preparedness for Foot and Mouth Disease, as well as the Systems for Enhanced Farm Services project.

In addition to routine disease investigations, DEDJTR also performs targeted surveillance through a range of state and national programs. However, the lack of a formal, documented approach to identifying, assessing and prioritising disease threats, limits DEDJTR's ability to demonstrate that these programs focus on the areas of greatest risk and need.

This information gap makes it difficult for DEDJTR to justify the absence of poultry from its targeted surveillance activities. While its surveillance in the wild bird population provides it with some information on risks to the poultry sector, DEDJTR currently does not have sufficient assurance that the industry-led disease surveillance of poultry is effective.

DEDJTR's livestock disease surveillance system is sophisticated and has contemporary functionality. However, the effectiveness of this system has been impaired by a decline in the number of disease surveillance investigations undertaken, and issues with data quality and timeliness.

Preventing illegal swill feeding

One activity creating a particularly high risk for livestock health and primary production in Victoria is the illegal feeding of swill—food waste containing meat, imported dairy products and other mammalian products or by-products—to pigs. Feeding swill to pigs is illegal in Australia because it may contain exotic disease agents including but not limited to FMD. It presents the most likely opportunity for an FMD outbreak in Australia.

DEDJTR's past efforts to manage swill feeding risks included audits of approximately 600 food outlets in both 2009 and 2013. It has also provided information to raise awareness of swill feeding risks to food outlets and pig producers. DEDJTR is working to improve in this area by developing a dedicated communication strategy and action plan to better integrate its swill feeding activities and promote awareness of swill feeding issues among food outlets and small scale pig owners.

While this work is valuable, there remains a need for DEDJTR, the Department of Health and Human Services and local government to work together to establish a more effective method for monitoring the food disposal practices of food outlets. Specifically, environmental health officers—who are employed by local councils and regulate food outlets—are currently not required under legislation to monitor food disposal practices. DEDJTR has identified that expanding environmental health officers' powers to include the monitoring of outlets' food disposal practices would significantly improve regulatory oversight of illegal swill feeding.

Preparedness to respond

Response plans and procedures

DEDJTR currently has 180 standard operating procedures and 46 manuals of procedures covering a wide range of diseases and activities. Many of these procedures are to be used during emergency animal disease responses. These procedures are fragmented, difficult to follow and largely out of date. DEDJTR has recognised this issue and is working to update and streamline access to its manuals of procedures and standard operating procedures.

DEDJTR has undertaken detailed planning for FMD through its Improving Victoria's Preparedness for Foot and Mouth Disease project. This planning focus is beneficial and justified considering the significant risks FMD poses to Victoria's economy. Importantly, this project aims to yield benefits beyond FMD to Victoria's livestock biosecurity preparedness more broadly.

The delivery of this project fell behind schedule during 2013–14, with approximately $1 million of the $2.3 million annual project budget carried forward to 2014–15. Project delivery has improved since a dedicated project manager and project control board was established in mid‑2014, however, the project was not fully delivered by 30 June 2015 as originally planned. In particular, one key project initiative—to develop a state response plan for an FMD outbreak—will not be finalised until mid-2016. DEDJTR advised that this is due to new requirements arising from Victoria's reformed emergency management arrangements.

Response capability

DEDJTR has tested its preparedness and capability to respond to a major livestock disease through a wide range of emergency animal disease simulation exercises. Departmental reviews of these exercises found that they were effective in achieving their objectives. However, DEDJTR has not selected, planned for and delivered these exercises in a strategic manner. It is therefore unclear whether past exercises have combined to focus on the areas of greatest need.

DEDJTR has also provided and participated in a variety of other livestock biosecurity training programs. These programs have made a valuable contribution to disease preparedness among departmental staff and the private veterinary sector. Despite this, it is unclear whether the programs collectively have the coverage and content needed to provide staff and private veterinarians with sufficient technical skills to respond to an emergency animal disease outbreak.

DEDJTR's simulated and real life disease responses are routinely evaluated and key lessons learned have been captured in evaluation reports. Even so, DEDJTR has recognised the need for a more robust approach to evaluating these activities. It is now working to develop a biosecurity evidence framework to provide a consistent approach to measuring, evaluating and reporting performance against desired outcomes.

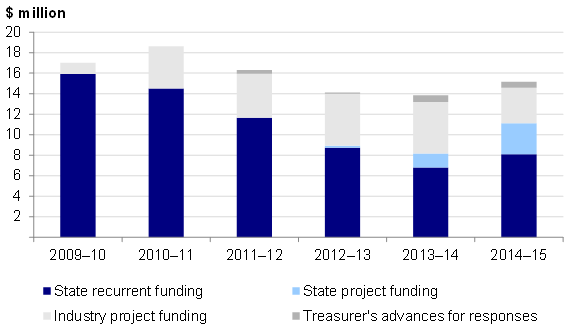

Response capacity

Recurrent state funding for core livestock biosecurity activities reduced by 49 per cent between 2009–10 and 2014–15. The funding stream covers a range of critical functions that include, but are not limited to, veterinary services, surveillance and tracing livestock movements. This trend increases Victoria's reliance on reactive funding allocations to protect its livestock industries from emergency animal diseases. It represents a diminished return on investment for the state compared to preventative and preparatory activities.

Additionally, the total number of veterinary and animal health officer positions in DEDJTR has decreased by 42 per cent since 2010. DEDJTR's December 2014 Biosecurity Budget Strategy highlights the implications of its staff resourcing constraints. In its strategy DEDJTR reports that its existing veterinary and animal health staffing levels are insufficient to meet the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE) expectation that a jurisdiction is able to manage one medium or two concurrent small animal disease outbreaks from within its own staff resources. While Victoria is not directly a member of the OIE, this is a useful benchmark for comparison.

Response systems

DEDJTR has an adequate response information system in place with wide-ranging functionality. However, the effectiveness of this system is undermined by a decline in surveillance activity over time.

DEDJTR is taking a leading role to address known weaknesses in the national system for tracing sheep and goat movements during a major disease outbreak. This work could potentially lead to significant improvements in livestock disease prevention, preparedness and responses in Victoria and other jurisdictions.

Stakeholder engagement

DEDJTR's engagement with government bodies involved in livestock biosecurity has been satisfactory and has occurred through:

- national biosecurity arrangements

- Victoria's Emergency Management Framework

- its memorandum of understanding with the Department of Health and Human Services for jointly managing the threat of zoonotic diseases

DEDJTR engages extensively with non-government stakeholders on livestock biosecurity matters. However, this engagement has not occurred in line with an overarching strategic approach. The needs of, and risks to, non-government stakeholder groups—including livestock industries and private veterinary practitioners—have not been systematically assessed. DEDJTR advised that it has commenced work on an overarching stakeholder engagement strategy to address this gap.

DEDJTR's newly developed risk-based approach for targeting livestock biosecurity compliance and enforcement activities is adequate, but yet to be implemented. The successful application of this new approach will be challenged by the growing demand for animal welfare investigations. Combined with a decline in staff resourcing, this growing demand places pressure on DEDJTR's capacity to perform other forms of animal health fieldwork.

Livestock disease responses

The audit examined DEDJTR's responses to the following livestock disease incidents:

- low pathogenic avian influenza outbreak, 2012

- anthrax case, 2015

- suspected FMD incident, 2015.

While some areas for further improvement are identified, DEDJTR's responses to these small-scale and suspected outbreaks have been managed well overall. However, these incidents have been small in scale and have not tested the state's ability to respond to larger or more complex disease outbreaks. As a result the full capacity or capability of Victoria's livestock biosecurity system is unclear.

Recommendations

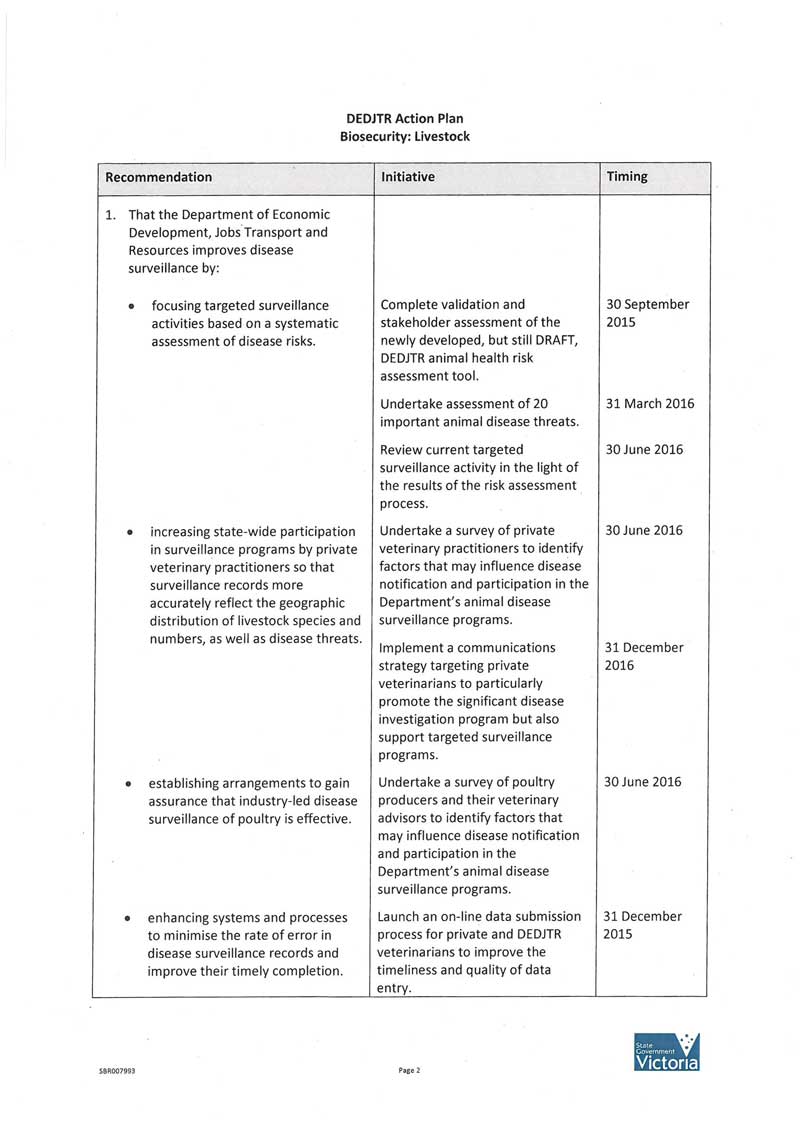

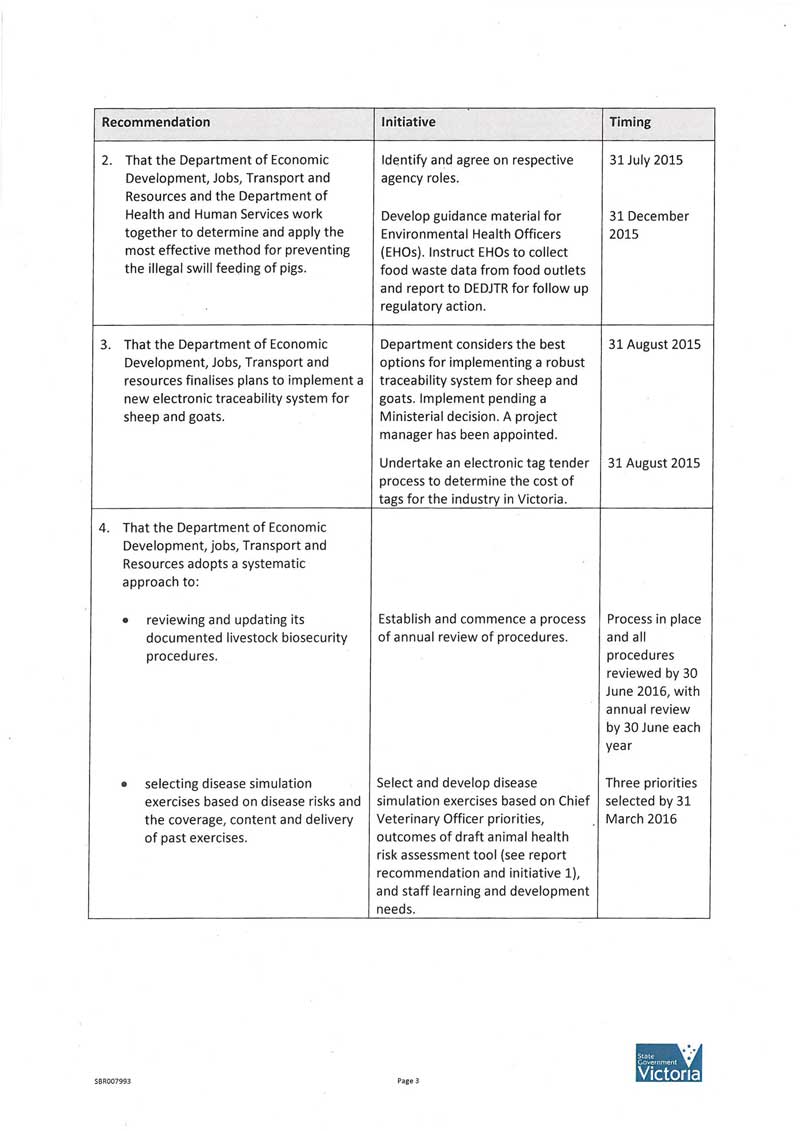

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources improves disease surveillance by:

- focusing its targeted surveillance activities based on a systematic assessment of disease risks

- increasing statewideparticipation in surveillance programs by private veterinary practitioners so that surveillance records more accurately reflect the geographic distribution of livestock species and numbers, as well as disease threats

- establishing arrangements to gain assurance that the industry-led disease surveillance of poultry is effective

- enhancing systems and processes to minimise errors in disease surveillance records and improve their timely completion.

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources and the Department of Health and Human Services work together to determine and apply the most effective method for preventing the illegal swill feeding of pigs.

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources finalises plans to implement a new electronic traceability system for sheep and goats.

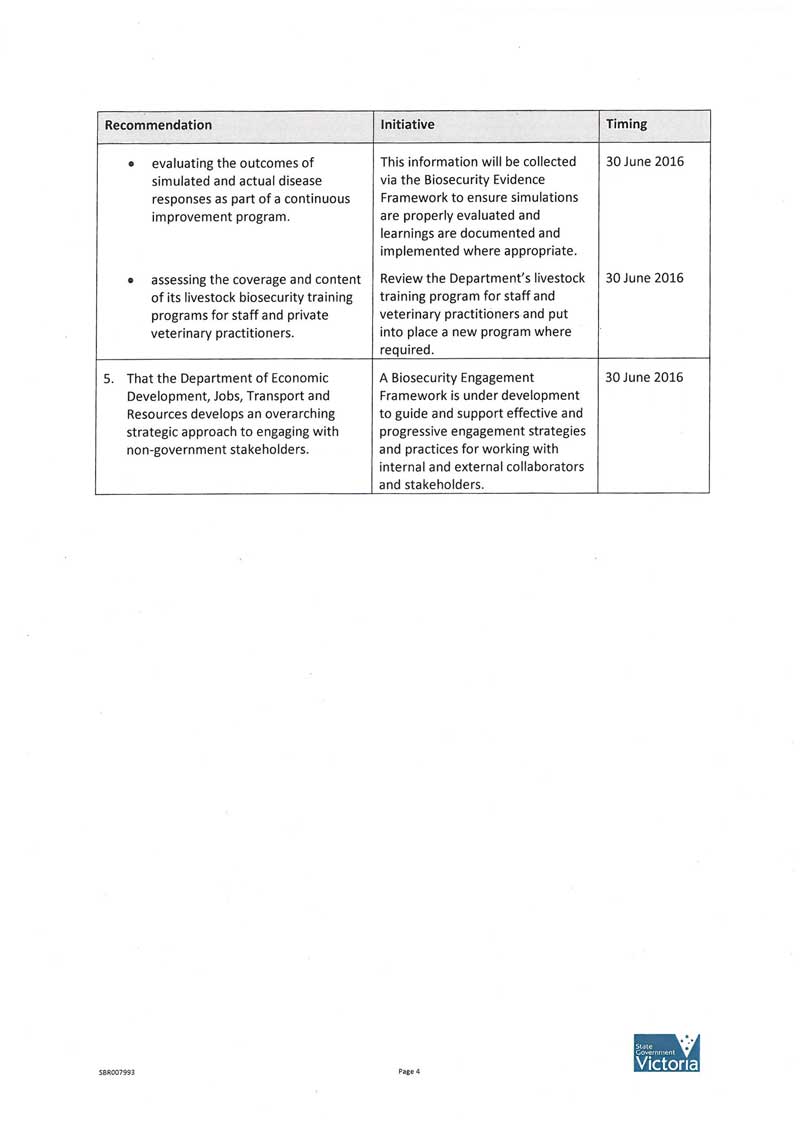

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources adopts a systematic approach to:

- reviewing and updating its documented livestock biosecurity procedures

- selecting disease simulation exercises based on disease risks and the coverage, content and delivery of past exercises

- evaluating the outcomes of simulated and actual disease responses as part of a continuous improvement program

- assessing the coverage and content of its livestock biosecurity training programs for staff and private veterinary practitioners.

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources develops an overarching strategic approach to engaging non-government stakeholders.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources and the Department of Health and Human Services throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The Intergovernmental Agreement on Biosecurity defines biosecurity as 'the management of risks to the economy, the environment, and the community, of pests and diseases entering, emerging, establishing or spreading'.

Victoria remains free of many pests and diseases. This has provided its agricultural industries with a significant competitive advantage and helped maintain access to premium export markets. It also supports sustainable growth and increased employment in the livestock industry sector. According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics, Victoria's food and fibre exports totalled $11.4 billion in 2013–14, while the gross value of agricultural commodities—including meat, milk derived products, eggs, hides, skins and animal fibre—was $12.7 billion.

Biosecurity measures also provide significant public health benefits. This is because a number of animal diseases can be transmitted to humans. These are known as zoonotic diseases. People in close contact with high numbers of livestock animals, such as farmers, shearers and veterinarians, are at a higher risk of contracting a zoonotic disease that could then be transferred to the general population.

Despite Victoria's advantageous animal biosecurity status, exotic and other emergency animal diseases remain an ever-present threat to Victoria's livestock industries. The 2001 outbreak of foot-and‑mouth disease (FMD) in the United Kingdom is estimated to have caused more than US$12 billion in losses and the slaughter of more than six million sheep and cattle to eradicate the disease.

The Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences estimates that the impact on Australia's economy of a large scale, multi-state outbreak of FMD would be $52 billion over a 10-year period. Of all Australian states and territories, Victoria is considered most at risk of an FMD outbreak due to its temperate climate and intensive livestock production systems.

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's (CSIRO) 2014 report Australia's Biosecurity Future flags a number of global trends and highlights the significant change and growing complexity of Australia's biosecurity challenges. These trends cover:

- agricultural expansion and intensification

- urbanisation and changing consumer expectations

- global trade and travel

- biodiversity pressures

- declining resources.

The CSIRO reports that these trends could lead to a future where existing biosecurity processes and practices are not sufficient. The report identifies 12 potential biosecurity 'megashocks' to illustrate the challenges that Australia may face in the future, such as a nationwide outbreak of FMD or an epidemic of a zoonotic disease.

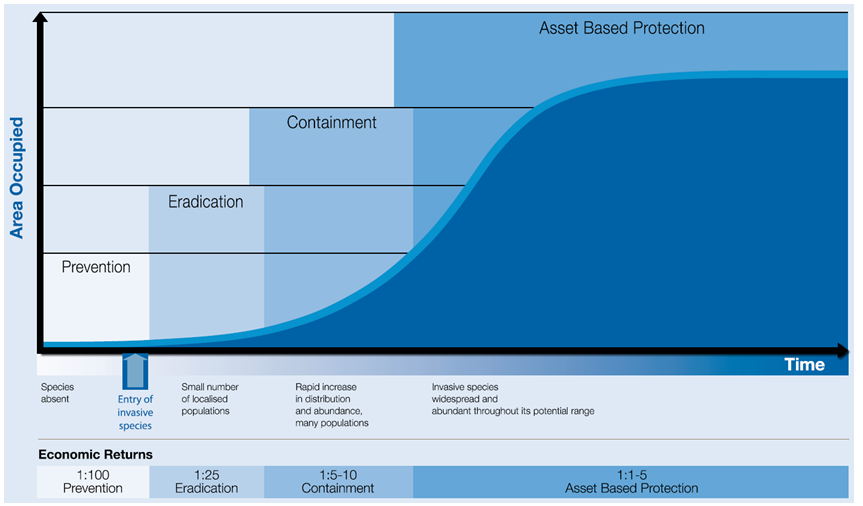

The 2009 Biosecurity Strategy for Victoria used a generalised invasion curve to show the return on investment for different stages of disease control activity. This curve shows that the greatest return on investment is achieved by investing in prevention and early intervention.

Figure 1A

Generalised invasion curve showing actions appropriate to each stage

Source: Biosecurity Strategy for Victoria, 2009.

There are many diseases that have the potential to impact Victoria's livestock industries, a number of which are transmittable to humans. Some of the better known livestock diseases are outlined in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

High profile livestock diseases

|

Anthrax An acute infectious bacterial disease that can affect humans and a wide range of domestic and wild animals. It is caused by the bacterium Bacillus anthracis. Anthrax typically causes three types of infection affecting the lungs, the digestive tract, or the skin. Avian influenza A highly contagious viral infection, primarily in birds. Clinical signs range from not being apparent in waterfowl to a rapidly fatal condition characterised by gastrointestinal, respiratory and/or nervous signs in chickens and turkeys. Avian influenza has the capacity to infect humans. There are two types of the virus: highly pathogenic and low pathogenic. Equine influenza An acute, highly contagious viral disease that can cause rapidly spreading outbreaks of respiratory disease in horses. Other equine species are also susceptible. Australia and New Zealand are the only countries with significant equine industries that are free from equine influenza without vaccination. Foot-and-mouth disease An acute, highly contagious viral disease of domestic and wild cloven-hoofed animals. The disease is clinically characterised by the formation of vesicles and erosions in the mouth and nostrils, on the teats, and on the skin between and above the hoofs. FMD can cause serious production losses and is a major constraint to international trade in livestock and livestock products. There have been no reported outbreaks of FMD in Australia since the 1870s. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan disease strategies.

1.2 Livestock biosecurity framework

Livestock biosecurity in Australia is jointly managed by Commonwealth, state and territory governments in partnership with industry and private veterinary practitioners.

1.2.1 Commonwealth framework

The Commonwealth Department of Agriculture manages quarantine controls at Australia's borders. It also provides import and export inspection and certification to help retain Australia's advantageous animal health status and wide access to overseas export markets.

Figure 1C outlines the key national instruments that have implications for state and territory government roles in relation to livestock biosecurity.

Figure 1C

National instruments for livestock biosecurity

|

Intergovernmental Agreement on Biosecurity The Commonwealth, state and territory governments—excluding Tasmania—entered into this agreement in January 2012. It aims to strengthen the working partnership between the Commonwealth, state and territory governments, and to improve the national biosecurity system by defining the roles and responsibilities of governments and outlining the priority areas for collaboration. Emergency Animal Disease Response Agreement (EADRA) The EADRA was signed in 2002 and brings together Commonwealth, state and territory governments and livestock industry groups to prepare for, and respond to, emergency animal disease outbreaks. Animal Health Australia is the custodian of the EADRA. Australian Veterinary Emergency Plan (AUSVETPLAN) AUSVETPLAN comprises a series of manuals setting out the roles, responsibilities and policy guidelines for agencies and organisations involved in responding to an emergency animal disease outbreak. AUSVETPLAN includes nationally agreed disease strategies and response policy briefs for all diseases listed in the EADRA. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2.2 Victorian framework

While the Commonwealth biosecurity framework focuses on quarantine control at borders and on import and export inspection and certification, state and territory governments are responsible for preventing the establishment of livestock diseases and responding to outbreaks within their own borders.

The Victorian livestock biosecurity system comprises producers, processors, saleyards, stock agents, transporters, veterinary practitioners, veterinary laboratories and government agencies.

Key agency roles

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) is responsible for developing policy, standards, delivery systems and services aimed at protecting animals from pests and diseases, protecting the welfare of animals and preserving market access for Victoria's livestock industries.

DEDJTR works closely with other Australian, state and territory government agencies to support their detection and management of outbreaks of pests and diseases, and to support verification and certification activities for agriculture and food products.

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) is responsible for managing zoonotic threats from a human health perspective. This includes responding to and controlling zoonotic disease outbreaks. DEDJTR also has a role in protecting public health through controlling zoonotic diseases.

DEDJTR and DHHS collaborate in planning, surveilling, managing, responding to and controlling zoonotic diseases. This is managed through a 2010 memorandum of understanding between the former departments of Health and Primary Industries.

Private veterinary practitioners

Private veterinary practitioners perform the majority of the disease investigations in Victoria. Their regular contact with industry and feedback to DEDJTR makes them a critical part of livestock disease surveillance and preparedness in Victoria.

Veterinary practitioners are registered by the Veterinary Practitioners Registration Board of Victoria. Registered practitioners must be able to diagnose animal diseases including those that are economically important and/or zoonotic. Practitioners are required to promptly report potential cases of exotic and other emergency livestock diseases to DEDJTR.

Livestock industries

DEDJTR works with a range of stakeholder groups to protect and enhance Victoria's livestock industries. This occurs through a number of industry consultative committees that deal with disease control, welfare standards, livestock traceability and emergency animal disease preparedness.

DEDJTR also interacts with individual livestock producers, stock agents, saleyard managers and livestock transporters to educate, monitor and enforce activities in line with agreed livestock health and welfare standards.

Legislation

The Livestock Disease Control Act 1994 is the key act governing livestock biosecurity in Victoria. The Act provides the legislative framework for the prevention, monitoring and control of livestock diseases and is designed to protect domestic and export markets and public health. A key function of this Act is to provide powers and mechanisms to combat exotic disease outbreaks. It also covers compensation, licences and registrations, and enforcement.

Other relevant acts include the:

- Livestock Management Act 2010

- Stock (Seller Liability and Declaration) Act 1993

- Impounding of Livestock Act 1994

- Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986

- Emergency Management Act 1986 and Emergency Management Act 2013

- Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 and Public Health and Wellbeing Regulations 2009.

1.2.3 Emergency management governance arrangements

Responses to livestock disease outbreaks fall within the Victorian Emergency Management Framework, which is coordinated by Emergency Management Victoria. (EMV). EMV maintains the Emergency Management Manual Victoria, which outlines the different roles agencies have during emergency incidents. The manual appoints DEDJTR's Chief Biosecurity Director as the state controller for livestock disease outbreaks and the Chief Veterinary Officer as the deputy state controller. This arrangement is currently under review by DEDJTR.

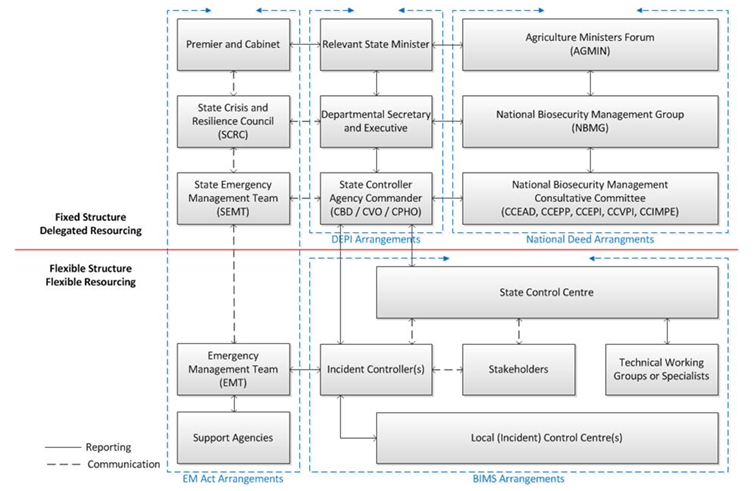

The governance arrangements supporting an emergency animal disease outbreak in Victoria are complex and involve input from Commonwealth and state governments, as well as livestock industry stakeholders. This is illustrated in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

Commonwealth and Victorian emergency management arrangements

Note: Fixed Structure Delegated Resourcing—the components of an emergency response with a predefined structure and resourcing model.

Flexible Structure Flexible Resourcing—the structure and resourcing of these components varies depending on the response.

BIMS—Biosecurity Incident Management System.

DEPI—the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries, whose biosecurity functions are now performed by DEDJTR.

Source: Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources.

1.3 Livestock welfare

The World Organisation for Animal Health defines animal welfare as how an animal is coping with the conditions in which it lives, both physically and emotionally.

Livestock welfare is an area of increasing public concern. There is a growing community expectation that livestock industries will treat their animals humanely, while market access is becoming more contingent on demonstrating that sound animal welfare practices are in place.

Livestock welfare is also a key consideration when responding to a disease outbreak. For example, it is widely expected that any culling of animals undertaken to prevent a livestock disease from spreading will be performed in a humane manner.

Rising animal welfare concerns have led to changing practices in the management of livestock. This includes large numbers of poultry and egg layers being reared under free range systems, which can pose increased biosecurity risks by exposing animals to wild birds carrying diseases. Retail sales of free range eggs have doubled since 2000 and a quarter of eggs produced in Australia are now free range.

In Victoria, livestock producers are responsible for the health and welfare of livestock and must comply with the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals Act 1986, which is administered by DEDJTR. The Act aims to prevent animal cruelty, encourage the considerate treatment of animals and raise community awareness about preventing animal cruelty.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess the effectiveness of Victorian biosecurity practices that relate to livestock disease management and the associated risks to primary production, animal welfare and human health.

To address this objective, the audit assessed DEDJTR's and DHHS's:

- activities to prevent the establishment of livestock diseases, including those that are zoonotic

- arrangements for responding to a serious livestock disease outbreak.

The audit focused on exotic livestock diseases, as well as other emergency animal diseases, such as anthrax.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit examined livestock biosecurity measures through document reviews and interviews with DEDJTR and DHHS.

The audit was conducted under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994, and was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Total cost of the audit was $455 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the prevention and early detection of livestock biosecurity threats

- Part 3 examines preparedness to respond to a livestock disease outbreak

- Part 4 examines stakeholder engagement.

2 Prevention and early detection

At a glance

Background

Preventing and swiftly detecting livestock disease outbreaks is critical to maintaining Victoria's advantageous animal health status and the economic benefits it provides.

Conclusion

A decrease in suitable staff and financial resourcing has increased the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources' (DEDJTR) reliance on Victoria's network of private veterinary practitioners to identify livestock disease threats. However, the rate of private veterinary participation in surveillance has also decreased. This has impaired Victoria's capacity to detect an emergency livestock disease before it becomes widespread.

Findings

- DEDJTR lacks a systematic approach to its disease-level risk management but is working to address this gap.

- Since 2011–12 DEDJTR's livestock disease surveillance activities have decreased by 39 per cent. Over the same period there has also been a 7 per cent decline in surveillance investigations by private veterinary practitioners.

- Surveillance systems are adequate but undermined by the above weaknesses and issues with data quality and timeliness.

- DEDJTR has a particular focus on preventing illegal swill feeding of pigs but requires support from the Department of Health and Human Services to be fully effective in this area.

Recommendations

- That DEDJTR improves disease surveillance systems, processes and participation.

- That DEDJTR and the Department of Health and Human Services work together to determine and apply the most effective method for preventing the illegal swill feeding of pigs.

2.1 Introduction

Preventing and swiftly detecting livestock disease outbreaks is critical to maintaining Victoria's advantageous animal health status and the economic benefits it provides. Success in this area relies on:

- a robust, systematic approach to identifying, assessing and prioritising disease threats, and using this to inform decision-making

- a comprehensive passive disease surveillance network that utilises the expertise of private veterinary practitioners to provide timely detection and reporting of disease threats and outbreaks

- targeted surveillance programs that support passive surveillance activities by focusing on high-risk areas

- contemporary systems to record and analyse disease surveillance information.

2.2 Conclusion

A decrease in suitable staff and financial resourcing has increased the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources' (DEDJTR) reliance on Victoria's network of private veterinary practitioners to identify livestock disease threats. However, the rate of private veterinary participation has also decreased. This has impaired Victoria's capacity to detect an emergency livestock disease before it becomes widespread.

DEDJTR's recent work to enhance its surveillance systems, improve non-government participation in surveillance programs and address the significant risks posed by the illegal swill feeding of pigs is encouraging. DEDJTR is also working to develop a disease risk assessment tool that aims to improve the effectiveness and transparency of its decision-making. However, these initiatives are incapable of fully restoring the diminished capacity of Victoria's livestock disease surveillance system.

This situation needs urgent attention to ensure protection of Victoria's advantageous animal health status, the considerable economic benefits it provides, and the health of Victorians.

2.3 Risk management

Livestock diseases pose significant risks to Victoria's economy. For example, the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences estimated that the economic impact of a large-scale foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) outbreak in Australia would be $52 billion over a 10-year period. With limited resourcing available and numerous emergency animal disease threats, a robust and systematic risk management approach is essential.

We have examined risk management for livestock biosecurity at the following levels:

- disease level

- business level

- state level.

DEDJTR is now working to apply a systematic approach to its disease-level risk management. This may impact on future risk management at a business level and to a lesser extent may influence risk management at the state level.

2.3.1 Disease-level risk management

DEDJTR's past approach to identifying and assessing livestock disease risks has often been informal and undocumented. This limits assurance that its resources and initiatives have been well targeted.

This issue was also identified in the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries' (DEPI) 2014 review of its animal health service, which acknowledged that 'formal, documented risk assessment does not underpin planning or decision-making' with respect to animal health risks. The review found that there was also insufficient risk assessment capability within the department's animal health service.

DEDJTR is now developing a tool to assess animal disease threats to Victoria. Once completed, this tool will be used to prioritise future surveillance and preparedness activities. Figure 2A outlines DEDJTR's approach to developing this tool, which was due for completion by 30 June 2015.

Figure 2A

Development of DEDJTR's animal disease risk assessment tool

|

Stage |

Task |

Status |

|---|---|---|

|

Stage 1 |

Review current literature on animal disease risk assessment methods using sources within and outside of DEDJTR. |

Complete |

|

Stage 2 |

List disease threats and develop a test panel of 10 diseases to validate the risk assessment process. |

Complete |

|

Stage 3 |

Develop the risk assessment process, tools and metrics and test these using the test panel diseases. |

Not yet completed |

|

Stage 4 |

Assess high priority animal disease threats. |

Not yet completed |

|

Stage 5 |

Develop an implementation plan to assess the remaining listed animal disease threats. |

Not yet completed |

Note: This Figure reports progress as at 15 July 2015.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

While this project has the potential to address weaknesses in DEDJTR's identification and prioritisation of livestock disease threats, DEDJTR needs to support this work by:

- regularly reviewing and updating both the risk assessment process and its results

- consulting with relevant stakeholders on the risk assessment process and results, including by working with the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) to ensure that risks to human health posed by livestock diseases are sufficiently integrated into the tool.

Part of DEDJTR's disease-level risk management is its newly developed risk-based approach to monitoring and enforcing compliance with legislation, including the Livestock Disease Control Act 1994. This approach, developed in 2014, is yet to be adopted. DEDJTR intends to use it to better align risks with its compliance responses. Part 4 of this report provides further detail on DEDJTR's compliance and enforcement activities.

2.3.2 Business-level risk management

Prior to machinery-of-government changes in late 2014, the former DEPI had included the outbreak of a major livestock disease in its strategic risk register. The former DEPI's Biosecurity Division supplemented this with an operational risk register that identified and assessed 11 operational risks relating to livestock biosecurity. These risks covered, among other things, ineffective surveillance systems, a lack of staff accountability, inadequate approaches to animal welfare and poor compliance and enforcement. Since the Biosecurity Division was moved into DEDJTR in late 2014, it has continued to apply the same approach to its business-level risk management for livestock biosecurity.

The division's operational risk management had:

- assessed the likelihood and consequence of operational risks

- identified controls for each risk that were regularly monitored by the division

- regularly reviewed the division's risk profile through divisional meetings and risk workshops.

While DEDJTR's business-level risk management is not disease-specific, its planned systematic assessments of individual disease threats may impact on how livestock biosecurity risks are reflected in strategic and operational risk registers.

DEDJTR could further improve its business-level risk management by formally defining a tolerance level for each of its operational risks, particularly given that it would be unrealistic to have the funds and staff to comprehensively deal with all potential livestock biosecurity risks.

2.3.3 State-level risk management

State-level risk management for livestock biosecurity occurs primarily through the Victorian emergency management system coordinated by Emergency Management Victoria (EMV). The EMV published the Emergency Risks in Victoria report in 2014 that documents the results of a 2012–13 state-level risk assessment. This report identified an emergency animal disease outbreak as a serious risk to the economy, public health and the environment. DEDJTR actively contributes to identifying and assessing risks at the state level through its membership of the State Crisis and Resilience Council and the State Emergency Management Team.

DEDJTR's planned improvements to its disease-level risk management are unlikely to have a significant impact on how livestock biosecurity risks are broadly identified and assessed in the Emergency Risks in Victoria report.

2.4 Disease surveillance

Livestock disease surveillance plays a critical role in:

- demonstrating the absence or occurrence and distribution of infection

- detecting exotic or emerging diseases as early as possible

- monitoring disease trends

- facilitating disease management

- supporting claims for freedom from a disease

- providing data for use in biosecurity risk analysis and decision-making.

DEDJTR collects livestock disease data from a variety of sources, including its own staff, private veterinarians, farmers, laboratories, knackeries, saleyards and abattoirs. In particular, private veterinarians are central to the success of livestock disease surveillance programs as they perform the majority of disease investigations in Victoria.

Livestock disease surveillance programs take one of two forms:

- Passive surveillance involves the routine reporting of livestock disease events to DEDJTR. It is underpinned by disease notifications mandated by the Livestock Disease Control Act 1994.

- Targeted surveillance focuses on specific species, diseases and/or locations within the livestock supply chain.

2.4.1 Surveillance trends

Figure 2B shows the total number of livestock disease investigations performed under each surveillance program between 2011–12 and 2014–15. It also shows the number of these investigations undertaken by DEDJTR and private veterinary practitioners.

Figure 2B

Livestock disease surveillance investigations 2011–12 to 2014–15

|

Surveillance program |

Type |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Disease investigations(a) |

Passive |

2 166 |

1 971 |

1 901 |

1 815 |

|

Anthrax surveillance |

Targeted |

9 |

67 |

63 |

18 |

|

Early Detection of Emerging or Exotic Disease in Sheep and Goats |

Targeted |

197 |

184 |

176 |

144 |

|

Knackery Surveillance Project (Cattle) |

Targeted |

325 |

315 |

308 |

243 |

|

Lamb and Kid Mortality Surveillance Project |

Targeted |

188 |

91 |

96 |

87 |

|

Victorian Pig Health Monitoring Scheme |

Targeted |

40 |

81 |

22 |

1 |

|

Total investigations |

2 925 |

2 709 |

2 566 |

2 308 |

|

|

Private veterinarian subtotal |

1 634 |

1 728 |

1 609 |

1 522 |

|

|

Departmental subtotal |

1 291 |

981 |

957 |

786 |

(a) Includes the Significant Disease Investigation program and all disease and clinical case investigations undertaken on farms.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from DEDJTR.

Importantly, between 2011–12 and 2014–15:

- the total number of surveillance investigations performed by DEDJTR decreased by 39 per cent

- the total number of surveillance investigations performed by private veterinary practitioners decreased by 7 per cent

- the proportion of investigations performed by private veterinary practitioners increased from 56 per cent to 66 per cent

- the total number of investigations performed by both private veterinary practitioners and the department decreased by 21 per cent.

These trends reflect a decline in departmental staff resourcing to perform animal health fieldwork. Specifically, the total number of veterinary and animal health staff within DEDJTR decreased by 42 per cent between 2010 and 2015. The impacts of DEDJTR's resourcing constraints are discussed further in Part 3.

Ultimately, DEDJTR's surveillance coverage and capacity to detect an emergency animal disease before it becomes widespread has been weakened, with no corresponding increase in private veterinary surveillance activity to offset this gap.

2.4.2 Maximising participation in surveillance

DEDJTR's Significant Disease Investigation (SDI) program is an important driver for maximising participation in livestock disease surveillance by private veterinary practitioners and livestock producers. The SDI program encourages private veterinary practitioners to investigate and report unusual disease events by subsidising part of the investigation and laboratory costs. In relation to cattle, sheep, goats and pigs the SDI program also provides subsidies to livestock producers for engaging a private veterinary practitioner to investigate these events. Where there is genuine suspicion of an exotic or emergency animal disease, DEDJTR leads and pays for the investigation.

Figure 2C details the number of SDIs performed between 2009–10 and 2013–14.

Figure 2C

Number of significant disease investigations, 2009–10 to 2013–14

|

Species |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Cattle |

67 |

197 |

240 |

211 |

209 |

|

Sheep |

9 |

118 |

100 |

124 |

82 |

|

Horse |

5 |

278 |

25 |

4 |

4 |

|

Bird |

1 |

7 |

13 |

12 |

17 |

|

Goat |

2 |

15 |

11 |

5 |

8 |

|

Camel |

– |

1 |

1 |

6 |

1 |

|

Pig |

– |

1 |

4 |

1 |

3 |

|

Wildlife |

1 |

– |

1 |

– |

3 |

|

Rabbit |

– |

2 |

2 |

– |

– |

|

Mixed |

– |

– |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

Total |

85 |

619 |

398 |

364 |

328 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from DEDJTR.

The former DEPI completed a review of the SDI program in September 2014. The review found that 359 private veterinary practitioners across 146 practices had participated in the program during the review period, leading to a total of 1 794 investigations being recorded. However, the review identified a number of weaknesses in the program's coverage and uptake, as well as the time consuming nature of the investigation process. These included:

- only 12 veterinary practices accounted for over 50 per cent of investigations

- poor program uptake in Gippsland and north west Victoria

- a lack of frequent users of the program

- pigs and poultry were poorly represented in the program

- the process for approving, undertaking and reporting an SDI is time consuming and involves an excessive amount of paperwork

- the majority of completed disease investigations were not recorded on time.

The review made recommendations to streamline the SDI program's process and improve program awareness and uptake among private veterinarians and livestock producers. DEDJTR is now working to address these recommendations through its $4.7 million project, Improving Victoria's Preparedness for Foot and Mouth Disease, as well as the Systems for Enhanced Farm Services project. This includes initiatives to:

- develop a website for private veterinarians to report significant disease events and access surveillance data

- provide animal health staff with mobile access to surveillance systems and records

- survey private veterinarians and industry stakeholders on their surveillance needs

- conduct weekend workshops for private veterinarians to assist their detection and response to emergency animal diseases

- continue providing subsidies to private veterinarians and livestock producers for disease investigations under the SDI program.

The decline in departmental surveillance coverage and capacity significantly increases the importance of these initiatives.

Figure 2D

Case study—anthrax in 2015

|

In February 2015 DEDJTR was notified of a case of anthrax in a dairy cow in the Tatura area of the Goulburn Valley following an initial disease investigation by a private veterinary practitioner. Once the diagnosis was confirmed, DEDJTR immediately initiated a disease response. DEDJTR placed quarantine restrictions on the farm with livestock movements being prohibited, and the farm was decontaminated. The carcass of the dead animal was destroyed and compulsory vaccination was implemented on the farm with the disease and adjacent properties. There were no further cases of the disease. DEDJTR's review of the response found that it was effective in controlling the disease and preventing further cases. It acknowledged that it has been very difficult to determine contributing factors for anthrax outbreaks and recommended annual vaccination to be implemented in the herd in which this anthrax case arose to prevent potential future outbreaks. In managing this isolated case, DEDJTR undertook prompt actions, and effectively controlled the disease, preventing its spread. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4.3 Targeting surveillance activities

In addition to the targeted surveillance programs listed in Figure 2B, DEDJTR also performs targeted surveillance through national programs, including:

- the Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy Freedom Assurance Program

- the National Arbovirus Monitoring Program

- the National Sheep Health Monitoring Project

- animal product residue monitoring.

DEDJTR advises that these state and national programs are targeted based on national biosecurity requirements and export market access requirements. However, the lack of a formal, documented approach to identifying, assessing and prioritising disease threats, limits DEDJTR's ability to demonstrate that these programs focus on the areas of greatest risk and need. DEDJTR's current work to develop a tool to assess and prioritise animal disease threats provides an ideal framework to address this issue.

This information gap makes it difficult to justify the absence of poultry from targeted surveillance programs. DEDJTR advised that targeted surveillance in the poultry industry would not be as effective as that for pastoral livestock due to the nature of poultry diseases, which are heavily influenced by the wild bird population. It also advised that the self-regulated nature of the poultry industry means that it is able to perform its own surveillance. However, the results of this industry-led surveillance are not shared with DEDJTR for commercial reasons.

DEDJTR advised that it has employed a poultry specialist to manage the risks posed by not undertaking targeted surveillance within the poultry industry. In addition, DEDJTR's surveillance in the wild bird population provides it with some information on risks to the poultry sector. Despite this, DEDJTR still lacks assurance that the poultry industry is adequately monitoring disease threats.

2.4.4 Surveillance systems

The 'MAX!' epidemiology system is DEDJTR's central repository for animal health surveillance data. It was launched in 2009 and contains over 10 000 recorded disease events in Victorian livestock.

The system itself is sophisticated and has contemporary functionality. It allows recording of a wide range of important investigative information, including staff attending, location, details on the animals being investigated, clinical signs, lesions found, samples taken, preliminary and final diagnoses, source of the outbreak, and treatments administered. The system also has flexible query building functionality that allows searching of disease events using various criteria. Data from the system can be exported into spatial maps, graphs and other tabulated formats.

While DEDJTR's surveillance system is adequate overall, its effectiveness has been undermined by:

- a decline in the coverage and capacity of DEDJTR's livestock surveillance network

- weaknesses in the length of time taken to complete the SDI process.

- data quality issues—DEDJTR estimated in July 2014 that over 70 per cent of surveillance records contain mistakes due to either human error or incomplete data, which are routinely rectified by DEDJTR staff.

DEDJTR's improvement initiatives listed in Section 2.4.2 show that it is working to address the latter two issues.

2.4.5 Reporting surveillance

DEDJTR reports the livestock disease surveillance data it collects through the:

- annual publication Animal Health in Victoria

- monthly newsletter for DEDJTR animal health staff, Eyes Wide Open.

- monthly online newsletter for private veterinarians, VetWatch.

These reports combine to provide DEDJTR animal health staff, private veterinarians and the livestock industry with relevant information relating to livestock health issues in Victoria and in other jurisdictions.

Access to surveillance records for livestock producers and private veterinarians is expected to improve through the Improving Victoria's Preparedness for Foot and Mouth Disease project.

2.5 Preventing illegal swill feeding

One activity creating a particularly high risk for livestock health and primary production in Victoria is the illegal feeding of swill—food waste containing meat, imported dairy products and other mammalian products or by-products—to pigs.

Feeding swill to pigs is illegal in Australia because it may contain exotic disease agents including but not limited to FMD. This practice is believed to have caused FMD outbreaks overseas—including the 2001 outbreak in the United Kingdom—and provides the most likely opportunity for an FMD outbreak in Australia.

The growth in small scale pig ownership has increased the risks associated with illegal swill feeding. Unlike registered food outlets and piggeries, this group is a difficult demographic for DEDJTR to identify, monitor and engage with.

DEDJTR has made several efforts in the past to manage swill feeding risks:

- Audits of food outlets were done during 2009 and 2013 to identify those supplying swill to pig producers. The 2013 audit of 613 food outlets identified 71 pig owners that had received food waste from the outlets. Of these, five owners were found to be feeding illegal swill and DEDJTR sought prosecution against these people. An additional seven owners were found to have previously fed illegal swill to their pigs but had since stopped. Warning letters were issued to pig owners and food outlets where the supply and feeding of illegal swill may have occurred but could not be proven.

- Targeted audits of approximately 10 high-risk piggeries are done each year.

- Information to raise awareness of swill feeding risks has been provided to food outlets and pig producers. This has included, but is not limited to, fact sheets, seminars at regional field days and engaging with pig farmers through stakeholder groups.

In early 2015 DEDJTR formed a working group to better integrate and prioritise its work in this area. This includes developing a:

- 'prohibited food waste and pigs' communication and engagement strategy that aims to:

- link up actions across government, industry and DEDJTR

- work with food outlets to stop the provision of food waste to pig owners

- promote measures to identify and track small scale pig owners

- reinforce key messages to the commercial pig industry and registered pig owners

- separate communications plan to promote swill feeding awareness among two high risk groups—food outlets and small scale owners.

This recent work is a positive development, however, DEDJTR, DHHS and local government need to improve cooperation in relation to swill-feeding risk management. Environmental health officers—who are employed by local councils and regulate food outlets—are currently not required under legislation to monitor food disposal practices. DEDJTR has identified that expanding environmental health officers' powers to include the monitoring of outlets' food disposal practices would significantly improve regulatory oversight of illegal swill feeding. Such a change would require changes to the Food Act 1984, which is administered by DHHS.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources improves disease surveillance by:

- focusing its targeted surveillance activities based on a systematic assessment of disease risks

- increasing statewide participation in surveillance programs by private veterinary practitioners so that surveillance records more accurately reflect the geographic distribution of livestock species and numbers, as well as disease threats

- establishing arrangements to gain assurance that the industry-led disease surveillance of poultry is effective

- enhancing systems and processes to minimise errors in disease surveillance records and improve their timely completion.

- That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources and the Department of Health and Human Services work together to determine and apply the most effective method for preventing the illegal swill feeding of pigs.

3 Preparedness to respond

At a glance

Background

The outcome of any emergency livestock disease response is heavily influenced by the responsible agency's level of preparedness.

Conclusion

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources' (DEDJTR) capacity to prevent, prepare for and respond to an emergency livestock disease outbreak has been weakened by a decline in financial and staff resourcing. This increases the risk of the detection of an emergency livestock disease being delayed and impedes DEDJTR's ability to promptly respond to and control the spread of a disease.

Findings

- DEDJTR's livestock biosecurity procedures are neither current nor sufficiently accessible, but it is working to address this gap.

- DEDJTR's focus on dedicated planning for foot-and-mouth disease preparedness is positive and is expected to provide broader benefits to livestock biosecurity.

- DEDJTR has undertaken a range of training programs, simulations and evaluations that have helped to support disease preparedness.

- There has been a decline in financial and staff resourcing for core livestock biosecurity activities such as veterinary services, surveillance and tracing.

- DEDJTR has an adequate response information system in place with wide-ranging functionality.

Recommendations

That DEDJTR:

- finalises plans to implement a new electronic traceability system for sheep and goats

- adopts a systematic approach to reviewing its procedures, selecting simulation exercises, evaluating responses and assessing the coverage of its training programs.

3.1 Introduction

The outcome of any emergency livestock disease response is heavily influenced by the control agency's level of preparedness. Being well prepared requires:

- effective livestock biosecurity plans and procedures that focus on high-risk areas

- sufficient capability and capacity to effectively prepare for and respond to livestock disease outbreaks

- contemporary disease response information systems with wide-ranging functionality, including the capability to track livestock and deploy resources.

This part examines the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources' (DEDJTR) preparedness to respond to an emergency livestock disease outbreak.

3.2 Conclusion

DEDJTR's preparedness to respond to an emergency livestock disease outbreak has been supported by a wide range of training programs and simulation exercises. It is also supported by an adequate response information system that has wide-ranging functionality. DEDJTR is working to further improve in this area through its $4.7 million project, Improving Victoria's Preparedness for Foot and Mouth Disease, as well as planned revisions to its documented procedures. The success of these initiatives will depend on their effective implementation.

However, DEDJTR's disease preparedness has been weakened by a decline in financial and staff resourcing for core functions such as veterinary services, surveillance and livestock traceability. This trend increases the risk of an outbreak of an emergency livestock disease going undetected until it is widespread. It also increases DEDJTR's reliance on reactive funding allocations from government in the event of an outbreak. This is a less effective and efficient means of protecting Victoria's primary industries compared to resourcing preventative and preparatory measures.

Ultimately, the success of any future response to a medium to large scale outbreak will depend more heavily on input from other agencies, jurisdictions, private veterinary practitioners and Victoria's livestock industries.

3.3 Response planning

Until recently, DEDJTR's numerous response-related procedures have been fragmented, difficult to follow and largely out of date. DEDJTR has recognised this issue and is working to update and streamline its procedures.

DEDJTR's focus on dedicated planning for foot-and-mouth disease (FMD) preparedness is positive as it aims to improve livestock biosecurity preparedness more broadly. The project fell behind schedule during 2013–14, however, improvements in DEDJTR's project management arrangements have increased its rate of delivery during 2014–15. It is important that DEDJTR completes this project as a priority.

3.3.1 Livestock biosecurity procedures

DEDJTR currently has 180 standard operating procedures (SoPs) and 46 manuals of procedures (MoPs) covering a wide range of diseases and activities. Many of these procedures are to be used during emergency animal disease responses.

DEDJTR's review of its seizure of livestock in response to animal welfare issues in Gippsland during 2014 highlighted some key weaknesses in the way MoPs and SoPs have been managed. These included:

- procedures were fragmented and difficult to follow

- some procedures had been amended and released as working drafts during 2013 but had not been finalised

- procedures were difficult to find and often confused with previous versions that had not been removed from DEDJTR's information systems

- animal health staff were not made sufficiently aware of changes to procedures.

Additionally, in 2015 DEDJTR reviewed its MoPs and SoPs and found that:

- 46 per cent of MoPs had not been reviewed in the past two years

- 90 per cent of SoPs had not been reviewed in the past two years

- 51 per cent of SoPs had not been reviewed in the past four years.

The 2015 review acknowledged the need to improve DEDJTR's management of procedures and make it easier for staff to find relevant procedures. To achieve this DEDJTR has committed to streamline its MoPs and SoPs by the end of 2015. Figure 3A shows how DEDJTR's animal health procedures will be structured once this work is complete.

Figure 3A

Planned changes to DEDJTR's livestock biosecurity procedures

|

Existing procedures |

Revised procedures |

|---|---|

|

46 MoPs |

|

|

180 SoPs |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

This work aims to improve the currency, accessibility and understanding of disease response procedures. DEDJTR will also need to develop a method for regularly assessing:

- the currency and relevance of its procedures

- compliance with procedures, as this does not currently occur.

3.3.2 Foot-and-mouth disease planning

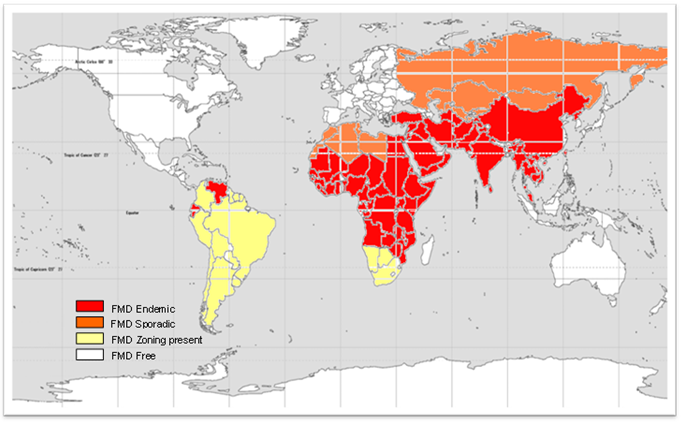

Figure 3B shows that, while Australia is free of FMD, the disease is established in numerous other countries. Considering it is estimated that a the economic impact of a large-scale, multi-state FMD outbreak is estimated to be $52 billion over 10 years, dedicated and comprehensive planning to enhance Victoria's preparedness for this disease is vital.

Figure 3B

Global status of foot-and-mouth disease, 2014

Source: Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

In 2013–14 DEDJTR was allocated $4.7 million over two years to deliver the Improving Victoria's Preparedness for Foot and Mouth Disease project. The project aims to address Victoria's high-risk issues as identified in the 2011 national review of FMD preparedness—Matthews report. These risks included:

- the effectiveness of swill feeding prohibitions

- Australia's national capacity to sustain a large scale FMD response

- traceability arrangements in the sheep industry

- the possibility that FMD may not be detected readily and speedily.

The project includes a wide range of actions to address these risks by enhancing disease surveillance, information systems, staff and private veterinary practitioner training, stakeholder engagement and the traceability of sheep and goats. Importantly, these actions provide benefits beyond FMD to Victoria's livestock biosecurity preparedness more broadly.

DEDJTR's delivery of this project fell behind schedule during its first year. About $1 million of the $2.3 million project budget for 2013–14 was not spent during that financial year and was carried forward to 2014–15. In June 2014 DEDJTR established a dedicated project manager position and a project control board to monitor the progress more closely. The board collects bimonthly reports detailing progress against project time lines and budgets.

Since establishing the project manager position and a project control board, DEDJTR has increased its rate of progress in delivering this project. However, further work is required to finalise project delivery. Some key deliverables will not be completed by their original deadlines:

- The development of a state response plan for FMD was originally due for completion by 30 June 2014. This plan will outline the manner in which an FMD outbreak will be managed in Victoria. A draft of this plan was not completed until 30 June 2015 and will not be finalised until mid-2016. DEDJTR advised that this is due to new requirements arising from Victoria's reformed emergency management arrangements.

- Targeted surveillance activities at saleyards, knackeries and abattoirs were originally due for completion by 30 June 2015 but are now due by 30 September 2015.

Additionally, there are isolated instances where project deliverables have been cancelled or abandoned:

- DEDJTR had allocated $35 000 to develop automated tools to detect aberrations in surveillance data that may be indicative of an emerging disease threat such as FMD. In March 2015 DEDJTR cancelled this work after the responsible staff member left. The documentation supporting this decision does not consider alternative methods for completing this work.

- The original project plan committed to developing separate communications strategies for FMD preparedness and responses by 30 June 2015. However, the FMD preparedness communications strategy was not developed and is no longer reflected in DEDJTR's progress reporting.

DEDJTR's adoption of more rigorous project management arrangements is positive. It is critical that DEDJTR now completes the delivery of this project as a priority to maximise Victoria's preparedness for FMD.

Figure 3C

Case study—suspected case of foot-and-mouth disease

|

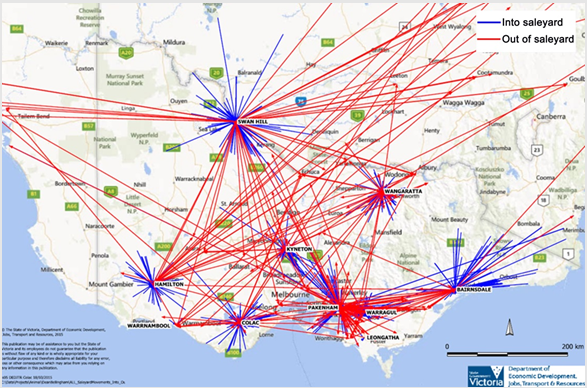

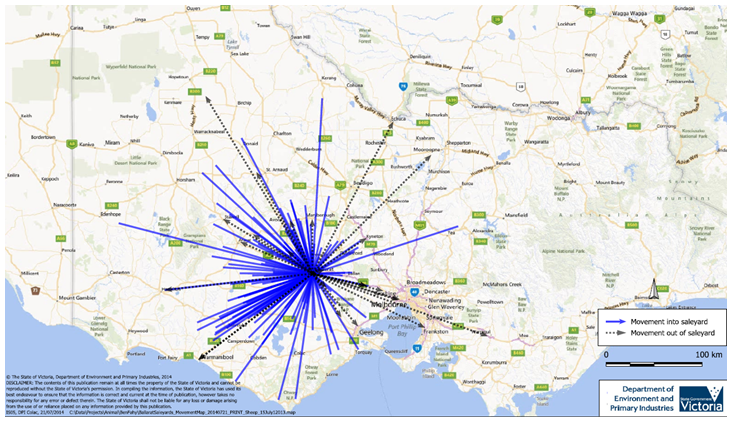

On 28 January 2015 DEDJTR was notified of a suspected case of FMD by a local veterinary practitioner in Echuca. On the same day, DEDJTR sent a veterinary officer to undertake a field investigation and collected biological samples for testing. As a precaution, a quarantine notice was placed on the property shortly after the departmental staff's initial visit. The samples were provided to the Australian Animal Health Laboratory at 10 pm on that day and tested overnight. Negative test results were confirmed at 4 am the following morning, and the quarantine was revoked later that day. Investigation of this suspected case and resolution of the FMD status of the property was completed by DEDJTR within 24 hours. DEDJTR's response to this suspected FMD case was prompt, laboratory testing was responsive and communication within DEDJTR was timely and effective. The following map shows the movements of cattle and sheep into and out of saleyards on 29 January 2015, the day after the suspected FMD case was reported. Echuca's central location among these movements highlights the potential for a confirmed case of FMD to spread rapidly within and outside of Victoria. Sheep and cattle movements into and out of saleyards on 29 January 2015

Map courtesy of Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.4 Response capability

Staff and stakeholder capability to effectively respond to a livestock disease outbreak is influenced by:

- exercises that simulate a response to a major disease outbreak

- training of agency staff and private veterinary practitioners

- evaluations of both simulated and real life disease responses.

DEDJTR has undertaken a range of activities across these three areas that have helped to support the state's livestock disease preparedness. However, there is room to improve how these activities are coordinated and evaluated.

3.4.1 Simulation exercises

Figure 3D shows that DEDJTR has conducted and participated in wide-ranging emergency animal disease simulation exercises, at both the national and state level. The focus of these exercises has been to test preparedness and capability to respond to a major livestock disease outbreak, as well as the strategies, plans and systems of government agencies and industry stakeholders.

Figure 3D

National and state simulation exercises undertaken in Victoria since 2009

|

Exercise |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Exercise Diva, 2009 |

Improve FMD response preparedness and capability. Various government agencies and industry peak bodies participated. Covered a wide range of preparedness issues across the areas of industry engagement, operational plans and communications. |

|

Exercise Flapdoodle, 2009 |

Develop Victorian epidemiologists' ability to deal with rapidly developing disease outbreaks. Participants monitored a hypothetical disease outbreak and made projections about the disease's progress. |

|

Exercise Wombat, 2012 |

Simulated an avian influenza outbreak in the Gippsland region. |

|

Leongatha Exercise, 2013 |

Test the SoP for visiting farms or livestock facilities. |

|

Maffra Exercise, 2013 |

Test the SoP relating to detection of suspected vesicular disease at a saleyard. |

|

Bairnsdale District Exercise, 2013 |

Test the SoP for securing a property that has a suspected or confirmed emergency animal disease. |

|