Compliance with Building Permits

Overview

Victoria’s building industry is a significant component of the state’s economy, employing almost seven per cent of the work force and generating over $24 billion in domestic and commercial building work in 2010–11. The audit examined how effective the building permit system is in providing assurance that approved building works meet the required building and safety standards. Specifically, the audit examined how effectively the Building Commission regulates the activities of municipal and private building surveyors and councils enforce compliance with building permits within their municipalities.

The audit found the Building Commission cannot demonstrate that the building permit system is working effectively or that building surveyors are effectively discharging their role to uphold and enforce minimum building and safety standards.

Ninety-six per cent of permits examined did not comply with minimum statutory building and safety standards. Instead, our results have revealed a system marked by confusion and inadequate practice, including lack of transparency and accountability for decisions made.

In the absence of leadership, guidance and rigorous scrutiny from the commission, councils have adopted a largely reactive approach to enforcing the Building Act 1993 that offers little assurance of compliance within their municipalities.

Consequently, there is little assurance that surveyors are carrying out their work competently, that the Building Act 1993 is being complied with, and the risk of injury or damage to any person is being minimised.

Compliance with Building Permits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER December 2011

PP No 91, Session 2010–11

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit, Compliance with Building Permits.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

7 December 2011

Audit summary

Introduction

Victoria's building industry is a significant component of the state's economy, employing almost 7 per cent of the work force and generating over $24 billion in domestic and commercial building work in 2010–11. These works are governed by the Building Act 1993 (the Act), the Building Regulations 2006 (the regulations), and the Building Code of Australia (BCA) that aim to assure buildings are safe and meet minimum standards.

The state introduced the competitive building permit system in 1994 as part of reforms designed to speed up the building approval system which, up to that time, had been administered by local councils.

The new system removed municipal building surveyors' monopoly on issuing building permits and opened the market to private building surveyors, who have to be registered and insured to protect the public's interests. By 2009–10 they were issuing around 85 per cent of permits worth 93 per cent of the total value of approved building works.

These reforms also established the Building Commission (the commission), as a new statutory authority to oversee building control, including the competitive building permit system.

The commission's functions are to:

- enforce compliance with the Act and regulations

- participate in the development of national building standards

- monitor developments relevant to the regulation of building standards in Victoria

- monitor the building permit levy collection system

- administer the Building Administration Fund

- inform and train the industry

- resolve disputes

- advise the minister on the carrying out of its functions and powers under the Act.

It administers four statutory bodies including the Building Practitioners Board (the board) which registers building practitioners, and supervises and monitors their conduct.

Local councils are also responsible for administering and enforcing parts of the Act, and for appointing municipal building surveyors who, along with their private counterparts, authorise and oversee building works to assure they are safe and comply with requisite building standards. Municipal building surveyors also have additional responsibilities for community safety and for enforcing statutory building requirements in their municipality.

This audit assessed the effectiveness of the building permit system in assuring that approved works meet requisite building and safety standards. It examined how effectively the commission regulates the activities of municipal and private building surveyors, and how effectively councils enforce compliance with the Act. It also analysed a sample of building permits issued by private and municipal building surveyors to determine if they complied with the Act, the regulations and the BCA.

Conclusions

The commission cannot demonstrate that the building permit system is working effectively or that building surveyors are effectively discharging their role to uphold and enforce minimum building and safety standards.

The commission has failed to develop a framework to monitor the effectiveness of the building control system more than 17 years since its establishment, and notwithstanding this fundamental issue being raised over 11 years and six years ago. It also has ineffective controls for assuring all building permit levies due are collected. Additionally, its powers to audit private building surveyors who are responsible for over 85 per cent of the more than 100 000 permits issued each year have not been adequately exercised.

These shortcomings are significant and mean the commission has not adequately discharged its responsibilities under the Act, and its obligations as a regulator. This means the building control system in Victoria depends heavily on 'trust', which is neither guided nor demonstrably affirmed by reliable data on the performance of building surveyors.

Ninety-six per cent of permits examined did not comply with minimum statutory building and safety standards. Instead, our results have revealed a system marked by confusion and inadequate practice, including lack of transparency and accountability for decisions made. In consequence, there exists significant scope for collusion and conflicts of interest.

This audit highlights the need for the commission and the board to purposefully assure ongoing compliance with minimum capability standards and to appropriately educate practitioners.

In the absence of leadership, guidance and rigorous scrutiny from the commission, councils have adopted a largely reactive approach to enforcing the Act that offers little assurance of compliance within their municipalities. Together with private surveyors, they apply varying interpretations of what the Act requires of them, resulting in further confusion and ad hoc practices.

Consequently, there is little assurance that surveyors are carrying out their work competently, that the Act is being complied with, and the risk of injury or damage to any person is being minimised.

Findings

Monitoring the building permit system

The commission has statutory monitoring responsibilities relating to the building permit system, but has yet to develop a framework to evaluate its performance more than 17 years since its establishment and 11 and six years respectively since two external reviews raised this fundamental shortcoming.

Specifically, it has no defined targets, standards or documented arrangements for monitoring and assessing the system's effectiveness, including whether building surveyors effectively discharge their statutory responsibilities to enforce technical building and safety standards.

The commission's monitoring and public reporting is limited to such activities as the number of complaints received against building practitioners, the number of audits undertaken, and consumer perceptions of building practitioners and their building experience. However, these measures offer little insight into the impact of the commission's regulatory efforts, or the extent to which building surveyors adequately discharge their statutory responsibilities.

Our 2000 audit, Building Control in Victoria: Setting sound foundations concluded that the commission had not given sufficient priority at that time to monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the Act in assuring the building control system was working. This was again noted by the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC) in 2005 as part of its inquiry into Housing Regulation in Victoria: Building Better Outcomes.

VCEC similarly observed that many of the commission's indicators did not relate to its performance as a regulator and recommended it review its framework to assure it reflected how well it was performing against the outcomes sought by the Act.

Notwithstanding, this framework has yet to be established.

The commission has advised it is now in the process of developing this framework, however considerable work remains to further clarify its parameters and the implementation approach.

Review of the regulation of building surveyors

In October 2009 the commission set up a working group to identify ways of addressing problems with the operation of the Act concerning the regulation of building surveyors. By 2011, the working group produced a discussion paper summarising key issues and options for amending the Act to improve the regulation of building surveyors and the building permit system.

While positive, the commission's discussion paper demonstrates the need for more regular and comprehensive reviews of the system's effectiveness as many of the issues it identifies are longstanding in nature.

Monitoring building permit data and levies

The commission is responsible for monitoring the system for collecting building permit levies. It does not, however, have adequate arrangements for assuring it receives all levies due.

The Act requires building surveyors to calculate, collect and deposit levies in the commission's Building Administration Fund each month. The levy payable in respect of an individual building permit is determined by the building surveyor and is based on the value of the building works covered by the permit. Currently, the integrity and accuracy of levies deposited depends entirely on the vigilance of the building surveyor and there are no controls to assure the reliability and regularity of this process.

Building surveyors are not required to become qualified valuers or quantity surveyors or to demonstrate that their calculation of levies payable is soundly based. Further, their failure to report all levies owed to the commission is not an offence, except if they provide false information.

Additionally, the commission does not systematically monitor that surveyors accurately estimate the levies they do report, which means it has no assurance it is receiving all levies due.

This lack of transparency and accountability over building surveyors' decisions, coupled with the commission's inadequate monitoring and enforcement controls means that surveyors could collude with clients to minimise their exposure to fees with little risk of detection. There is also no restriction on building surveyors using collected levies as working capital, until they deposit them in the Building Administration Fund each month.

The commission's 2011 discussion paper proposes further options to address protection of revenue through amending the Act. These options could assist in minimising future losses. Nevertheless, the commission already has extensive powers to audit whether building surveyors accurately estimate the levies they do report, but has to date not done so.

Council monitoring and enforcement

Councils are responsible for enforcing the Act in relation to their municipal districts but lack clarity on how their role extends to private surveyors. Further, their monitoring is limited and reactive in nature offering little assurance that all buildings and associated works in their municipalities meet requisite standards.

Councils do not have a statutory obligation to proactively monitor compliance with the Act, but can do so at their own discretion to gain assurance it is being administered and enforced effectively within their municipal districts.

Councils do not systematically review permit documentation lodged with them by private building surveyors or inspect associated works, considering this to be the role of the commission. Councils therefore only investigate matters if there is a complaint from the public.

Feedback from the councils examined indicates that this reactive approach has arisen due to limited resources, lack of clarity over how far their powers extend to private building surveyors, and a reluctance to pursue enforcement action due to liability concerns.

Councils have access to significant information relating to building permits lodged by private building surveyors, but there are no documented arrangements in place between the commission and councils to monitor surveyors' performance and the system's overall effectiveness.

Thus significant opportunities exist for councils and the commission to work together more effectively to monitor the building permit system.

Compliance of building permits with the Act and regulations

The Act requires a building surveyor to determine if proposed works comply with all statutory requirements before issuing a permit. However, significant gaps exist in council records to demonstrate that surveyors have adequately discharged this statutory obligation, and that approved works meet requisite building and safety standards.

Specifically, there was inadequate information on file for 96 per cent of the 401 permits examined to assess compliance with these requirements.

The regulations require an application for a building permit to contain sufficient information to show that the building work, if constructed as proposed, will comply with the Act and regulations. Hence this information should be evident in the documentation lodged by the surveyor with each permit at the relevant council. A failure to lodge this information is an offence under section 30 of the Act.

However, 72 per cent of domestic permits and 76 per cent of commercial permits did not contain sufficient information to demonstrate compliance with five or more required building technical or safety standards. Similarly, approximately 12 per cent of domestic permits and 27 per cent of commercial permits failed to show compliance with respect to 10 or more requisite standards.

In addition to these critical information gaps, there was also insufficient evidence in 89 per cent of the 80 permits subsequently selected for more detailed examination to determine whether building surveyors had thoroughly assessed all lodged information.

Therefore, there is little systemic documentation that surveyors had sufficient information upon which to form a reasonable view that proposed building works complied with the Act and regulations prior to issuing the permits.

Regulating building surveyors

Approach to regulation

The absence of targeted, risk-based technical audits of building surveyors means the commission is unable to provide reasonable assurance of the integrity and reliability of the building control system.

Performance audit program

The commission's performance audit program has not provided adequate scrutiny over the effectiveness of building surveyors' work. Audits are not risk-based, targeted or sufficiently informed by rigorous analysis of reliable data on the performance of building surveyors.

The function of a performance auditor under the Act, is to examine work carried out by a registered practitioner, to ensure it has been competently carried out, does not pose any risk of injury or damage to any person, and to assure that the Act and the regulations have been complied with. However, the commission's audit program neither comprehensively examines nor explicitly concludes on such matters.

Specifically, audits primarily cover municipal building surveyors, whereas private building surveyors who issue the vast majority of permits each year are not routinely examined. Additionally, the audits focus almost entirely on administrative matters, while compliance with the more critical safety and technical issues is not systematically assessed. Hence, contrary to their intent, these audits do not comprehensively assess compliance with the Act, the competence of surveyors, or whether any safety risks have been satisfactorily mitigated.

These issues were previously raised by our 2000 audit. That audit similarly found the commission's performance audits were 'paperwork reviews focused on administrative compliance that did not meet their statutory intent and thus rarely uncovered major issues'.

In the intervening 11 years little has changed.

In 2005 VCEC similarly found the rationale for the commission's monitoring and enforcement strategy was unclear and that its effectiveness and efficiency could not be assessed based on publicly available information.

VCEC recommended the commission publish its rationale in annual reports but it has not done so.

Additionally, the commission is not meeting its public target to audit each municipal building surveyor once every two years, and has no targets for auditing private building surveyors who issue the vast majority of building permits. Its lack of focus on these latter practitioners is a very significant gap in its audit program.

During this audit the commission asserted that it audited 98 per cent of all councils in the past three years, but had no evidence to substantiate this. Information available only shows 53 per cent of councils were audited.

Late into the conduct of this audit, the commission also advised that its targets are based on its 'audit continuum' concept, which seeks to audit councils once every two‑year block, instead of once every two years. However, this concept misrepresents the commission's performance relative to its public target, because it allows for up to four years to elapse between successive audits.

Further, the commission's performance auditors are not registered building surveyors. They are generalist investigators, typically drawn from the police, who do not come with, nor are they trained in, the technical skills needed to effectively audit the competency of building surveyors. The commission also had no policy to guide these investigators on the conduct of performance audits and there are no review and quality assurance arrangements to assure the effectiveness and quality of completed audits.

The commission initiated action to enhance its audit program during this audit.

Complaints management

Although the commission has a complaints policy and documented procedures, they do not detail sufficient arrangements for prioritising complaints or for improving the complaints system. There are no quality assurance standards for handling complaints and no performance measures. Further, the roles and responsibilities for monitoring and reporting on complaints management are unclear. The computerised complaints handling system has limitations and staff cannot use it effectively.

Almost two-thirds, 64 per cent, of complaint investigations are outsourced to generalist investigators but there are no clear guidelines, documented standards or procedures to assure the investigations are effectively handled.

There is also no evidence the commission reviews completed investigations regularly against defined quality standards. While external legal reviews of active investigations typically occur in 45 per cent of cases, there is insufficient assurance this is adequate in the absence of defined quality assurance and performance standards.

The commission commenced a strategic review of its complaint management processes in 2011 following a review of its management of an investigation into a complaint, and of the board's subsequent inquiry in 2009. This review concluded that the complainant was failed by the advice received from the commission and associated investigation, and also by the board's handling of the inquiry.

Both the commission and the board have since initiated action to address these matters.

Practitioner capability, registration and renewal

The board's assessment process for registering building surveyors is extensive, but not well documented, nor is it supported by clear guidelines, criteria or quality review standards.

Specifically, while its processes for assessing surveyor competence could lead to a thorough examination, existing gaps in guidance and documentation reduce accountability for decisions, including assurance that assessments are soundly based.

The board has no documented guidelines or criteria for evaluating the practical experience of building surveyors, and similarly has no guidelines to decide a 'pass' or 'fail' in relation to the competency examination and practical assessment. The board agrees that better definition of 'pass' or 'fail' for assessment is necessary and intends to address this as a priority. The board has, however, also indicated that assessment may not always be best determined by a single threshold figure.

The Act does not require a practitioner to demonstrate they have maintained their skill and capability to the level necessary to competently discharge their duties. This is a gap in the current regulatory framework. Capability is assessed only at the initial application stage, and a surveyor will remain registered for life on payment of the annual fee and insurance cover, unless the board deregisters them or their insurance cover lapses or is withdrawn.

The Department of Planning and Community Development is currently reviewing if there is a need to introduce compulsory continuing professional development for practitioner registration. This audit provides strong evidence in support of such an approach.

Greater scrutiny of the professional conduct of building surveyors, and better adherence by them to minimum competency standards and statutory requirements is required.

Recommendations

- The Building Commission should:

- expedite development of its monitoring and evaluation framework and clarify the targets, standards and arrangements for assessing the building permit system's effectiveness, and the impact of related monitoring and enforcement efforts

- conduct a fundamental review of the building permit system's effectiveness to identify and resolve the longstanding and othersystem-wide performance issues

- develop guidance for building surveyors on the process for determining and documenting the value of building works and thus for accurately estimating the levy payable to the Building Commission

- implement controls to prevent building surveyors from using levies collected as their working capital

- systematically audit surveyors' estimates of the value of building works to gain assurance they are soundly based and that it is mitigating financial losses arising from any incorrect valuations

- develop and implement a strategy, in consultation with the local government sector, to enable more effective coordination with councils to monitor the performance of the building permit system and of building surveyors

- clarify councils' responsibilities for monitoring and enforcing the Building Act 1993 relating to private building surveyors in consultation with the Department of Planning and Community Development and relevant stakeholders.

-

Councils should review and, where relevant, strengthen their monitoring and enforcement strategies to assure:

- they are risk based, targeted and sufficiently informed by reliable data on the performance of the local building permit system and of the surveyors operating within it

- that building works and associated permits comply with the Building Act 1993, the Building Regulations 2006 and the Building Code of Australia within their municipal districts.

-

The Building Commission, in consultation with stakeholders should:

- develop standard templates and procedures to require building surveyors to adequately document their assessment approach and basis of their decisions

- require building surveyors to demonstrate, using these templates and procedures, their consideration and acquittal of mandatory safety and technical requirements.

-

The Building Commission should strengthen its performance audit program to assure:

- it meets its legislative remit to provide assurance that the work carried out by a registered practitioner has been competently carried out, does not pose any risk of injury or damage to any person, and to assure that the Building Act 1993 and the Building Regulations 2006 have been complied with

- it is informed by rigorous analysis of reliable risk-based data on the performance of building surveyors

- it includes a clear rationale and annual targets for ongoing comprehensive technical audits of both municipal and private building surveyors performed by qualified practitioners

- it offers reliable information on whether building surveyors operating in both the domestic and non-domestic sectors effectively discharge their obligations to enforce compliance with the Building Act 1993 and the Building Regulations 2006

- it regularly undertakes and clearly documents reviews of both the program's and individual audit's effectiveness against defined quality standards.

-

The Building Commission should comprehensively assess, clearly document, and target via audit all identified major risks related to surveyors' administration of the building permit system.

-

The Building Commission should strengthen its complaints handling and investigation processes to assure:

- complaints are systematically prioritised according to the risk of non-compliance with safety and technical building standards, and that this is clearly documented

- they are governed by clear standards of effectiveness and efficiency, and that adherence to these requirements is regularly reviewed and monitored by senior management

- investigators receive sufficient training to enable them to form appropriate judgments about technical building matters

- clear quality assurance standards and effective controls are established for technical reports sourced from the Building Commission's external panel to assure they have been competently prepared.

-

The Building Practitioners Board should:

- develop criteria and guidelines for evaluating the competency of applicants to be registered as building surveyors and clearly document the basis of all of its related decisions

- systematically verify a sample of the character declarations supplied by applicants for registration to gain reasonable assurance they are reliable.

-

The Department of Planning and Community Development, in consultation with stakeholders, should:

- seek approval from the Minister for Planning to introduce a system of compulsory continuing professional development for building surveyors

- seek approval from the Minister for Planning to prepare an amendment to the Building Act 1993 to make registration renewal contingent on building surveyors satisfying minimum compulsory continuing professional development requirements.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, were provided to the Building Commission, the Building Practitioners Board, the Department of Planning and Community Development, Latrobe City Council, Melton Shire Council, Mitchell Shire Council and Monash City Council with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Building activity

Building activity in Victoria has a significant economic, social and environmental impact on the community. The industry provides employment, housing, commercial and social infrastructure and contributes to community wellbeing and amenity.

In 2010–11 the industry employed about 190 200 people or 6.9 per cent of the state’s labour force. Although 2010–11 saw a 6 per cent drop in the number of building permits issued from 113 670 in 2009–10 to 106 788, their value rose 2 per cent to $24.3 billion. This represents a 25 per cent increase from 2008–09 levels.

Building permits for housing make up the majority of permits issued, and account for $13.1 billion of approvals. Victoria led all states and territories in terms of value of building activity, contributing 32 per cent of national building approvals.

1.2 Building control framework reforms

The current building permit system was introduced in 1994 as part of reforms to increase its efficiency and effectiveness by allowing competition into the market. The option for building permits to be issued by private building surveyors was introduced, enabling them to compete with municipal building surveyors on the basis of timing and cost. Prior to the reforms, all building permits were issued by municipal councils.

Compulsory insurance and a registration process for practitioners were also introduced to improve protection for the public who engaged building practitioners.

The practice of councils issuing permits was widely considered to be lengthy and inefficient. The new system was expected to improve the skills of building surveyors and the speed of the approval of building permits.

Data is not collected on the time it takes to obtain a building permit, but it is generally accepted across the building industry that there has been a significant reduction in building permit approval times.

The number of permits issued by the private sector has grown steadily. In 1997, private building surveyors issued 57 per cent of the total number of building permits, representing 73 per cent of the total value of approved building work. By 2009–10 these had increased to 84 per cent and 93 per cent respectively.

1.3 The legislative and regulatory framework

Model Building Act

The Victorian legislative framework is based on the National Model Building Act, a project initiated in 1990 through the Australian Uniform Building Regulatory Coordinating Council, now the Australian Building Codes Board. This model, completed in late 1991, was intended to serve as the basis for legislative development to facilitate best practice and uniform building regulation in the states and territories. The framework of Victorian controls, the Building Act 1993, was established as part of these national competition-related reforms.

Building Act 1993

The Building Act 1993 (the Act) sets out the legal framework for regulating building construction, building standards and the maintenance of specific building safety features. The Act requires that a building permit must be issued prior to carrying out building work and sets penalties for failing to do so.

The objectives of the Act include to:

- establish, maintain and improve standards for the construction and maintenance of buildings

- facilitate the adoption and efficient application of national uniform building standards and the accreditation of building products

- enhance the amenity of buildings and protect the safety and health of people who use buildings

- facilitate and promote the cost-effective construction of buildings

- provide an efficient and effective system for issuing building and occupancy permits.

Building Regulations 2006

The Building Regulations 2006 (the regulations) are derived from the Act and set out the requirements for building permits, building inspections, occupancy permits, regulatory enforcement and maintenance of buildings. The regulations use the Building Code of Australia (BCA) as a technical reference that must be complied with.

Building Code of Australia

The BCA is a national set of technical provisions for the design and construction of buildings and other structures. The BCA is performance based, which means that it defines the way to achieve a specified outcome without prescribing a particular method. The BCA allows states to add requirements or cater for their own community expectations.

All building work is required to comply with the Act, the regulations and the BCA unless exempted.

Other legislation

Other legislation impacts on the building control system in Victoria, including the Domestic Building Contracts Act 1995 and the Local Government Act 1989.

1.3.1 Building permit system

The building permit system is an important control for regulating the construction and maintenance of domestic and commercial building works and certifying compliance with building regulations. The purpose of the system is to ensure that all building works meet minimum standards and safety requirements.

Building permits are required for most building work such as construction, alterations, removals and demolition. Permits cover items such as the siting of most single dwellings, protection of adjoining property during construction, structural adequacy, light, ventilation and drainage. Undertaking building work without the necessary permit is a serious offence and can result in penalties of up to $10 000.

Building permits provide assurance that proposed building works comply with building legislation prior to work commencing and that:

- the building practitioners are registered and carry insurance

- adequate documentation is prepared to support construction of buildings

- independent review of building documentation occurs

- key stages of building work are independently inspected

- buildings are independently assessed as suitable for occupation.

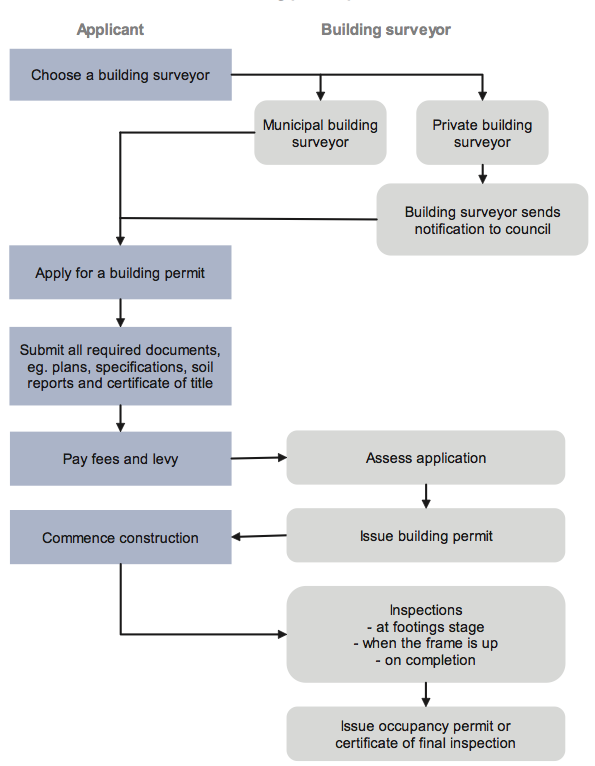

Obtaining a permit

To obtain a building permit, a property owner or their appointed agent must apply to the appointed building surveyor. The appointed building surveyor can be either a municipal building surveyor or a private building surveyor. The building surveyor is required to notify the relevant council of their appointment.

The application identifies the nature and cost of the building work and must include three sets of drawings, certificate of title, specifications, allotment plans, and any computations or reports deemed necessary to demonstrate that the building work will comply with the Act and regulations.

The building surveyor must assess the information within 15 days of receipt to determine if it complies with the regulations and lodge the documentation at the council. The building surveyor can issue a permit with or without conditions, or refuse to issue one.

The applicant pays the appointed surveyor a fee for issuing the building permit and a government levy which the building surveyor forwards to the Building Commission (the commission). When the permit is approved, building work can start.

The building surveyor must inspect the work at the end of each mandatory stage, including before footings are placed, when the frame is up, and when work is completed. The surveyor may also inspect at other times deemed necessary.

At the final inspection, the building surveyor issues either an occupancy permit or a certificate of final inspection. An occupancy permit means that the building is suitable for occupation. A certificate of final inspection is for extensions or alterations to existing buildings. The building permit process is summarised in Figure 1A.

Figure

1A

The building permit process

Source: Building in Victoria: a consumer’s guide, Building Commission and Victorian Municipal Building Surveyors Group, 2005, p.4.

1.3.2 Regulatory roles and responsibilities

Building Commission

The commission is a statutory authority established in 1994 to oversee building control in Victoria. The main functions of the commission as set out in the Act are to:

- monitor and enforce compliance with the provisions of the Act and the regulations relating to building and building practitioners

- participate on behalf of Victoria in the development of national building standards

- monitor developments relevant to the regulation of building standards in Victoria

- monitor the system of collection of the building permit levy

- administer the Building Administration Fund

- disseminate information, including to consumers, on matters relating to building standards and the regulation of buildings and building practitioners

- provide information and training to assist persons and bodies in carrying out functions under the Act or the regulations (except part 12A and the regulations under that part)

- promote the resolution of consumer complaints about work carried out by builders

- conduct or promote research relating to the regulation of the building industry in Victoria and to report on the outcomes of this research in its annual report

- advise the Minister for Planning on the carrying out of the commission’s functions and powers under this Act and on any other matter referred to it by the minister.

The commission administers four statutory bodies to provide industry leadership and regulate building quality. These are:

- Building Practitioners Board (the board)

- Building Advisory Council

- Building Appeals Board

- Building Regulations Advisory Committee.

Building Practitioners Board

The board oversees the quality and standard of professional services in the building industry. It is responsible for almost 25 000 registered builders and building professionals and for supervising and monitoring their conduct and ability to practice. The commission may refer builders who refuse to fix defective work to the board for disciplinary action. The board can suspend registration for several reasons, including when the practitioner is not insured or refuses to comply with the insurer’s reasonable direction to complete or rectify defective work.

The board can also hold an inquiry into the conduct of registered building practitioners or their ability to practice. It can do so on its own initiative, on referral by the commission, the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal, an insurer, or on the recommendation of someone it has appointed. Following an inquiry, it can discipline the practitioner with a reprimand, by awarding costs against them, or suspending or cancelling registration.

The board and the commission are central to overseeing the performance of building surveyors and their compliance with the Act. The commission conducts performance audits, investigates building practitioners based on complaints, and prosecutes legislative breaches. The board administers practitioner registration and conducts inquiries into the conduct of building practitioners.

Building Advisory Council

The Building Advisory Council is an industry-based advisory body to the Minister for Planning. It also advises the minister on the impact of the building regulatory system under the Act and regulations, the building permit levy and any other matter referred by the minister.

Building Appeals Board

The Building Appeals Board determines disputes and appeals arising from the Act and the regulations and deals with amendments to building legislation. It can determine whether a particular design or element of a building complies with the Act and regulations. It also hears appeals against decisions or actions of private and municipal building surveyors.

Building Regulations Advisory Committee

The Building Regulations Advisory Committee is a committee of building industry representatives that advises the Minister for Planning on draft building regulations and accredits building products, construction methods and systems.

Department of Planning and Community Development

The Department of Planning and Community Development is responsible for building policy and legislation. This includes development and management of the regulatory framework and implementation of national standards. The department also provides strategic policy advice on insurance and consumer protection, the national reform agenda, sustainability and national licensing relating to the building and plumbing industries.

Local government

Municipal councils are responsible for the administration and enforcement of parts 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 of the Act and the whole of the regulations within their municipal district. They are also required to appoint a municipal building surveyor responsible for administering and enforcing parts of the Act and the regulations within the municipal district. The Act provides councils with the same powers of enforcement whether a municipal or private building surveyor has issued the building permit.

Private and municipal building surveyors

Building surveyors play a pivotal role in the implementation, enforcement and monitoring of the building standards prescribed by the Act and the regulations. They authorise and oversee building work and are responsible for assuring that buildings are safe, accessible and energy efficient.

Private and municipal building surveyors have statutory obligations to administer and enforce the Act, even though private building surveyors are private businesses. Both are responsible for issuing building permits, including:

- assessing applications

- conducting mandatory inspections of building work

- making compliance orders when appropriate

- verifying that works have been completed according to permit conditions

- issuing occupancy permits and certificates of final inspection.

Municipal building surveyors have extensive extra functions related to community safety and administering and enforcing building legislation in their municipality.

Municipal and private building surveyors must collect building permit levies from building owners and forward them to the commission, basing the levy on the value of works covered by the building permit. Private surveyors also have extra reporting requirements. They must notify the relevant council of their appointment on a building project within seven days and lodge copies of building permits and associated documentation within seven days of issue. This reporting helps local government maintain a public register of all building work in the municipality to support building control.

1.4 Previous audits and reviews

VAGO’s 2000 performance audit of the building control system, Building Control in Victoria: Setting sound foundations examined the efficiency and effectiveness of aspects of the building regulatory system administered by the commission and its associated statutory bodies.

The audit identified weaknesses in the commission’s monitoring role, including its identification of building control risks and targeting of monitoring and enforcement activities. The audit also found there were opportunities for improving the rigour and suitability of registration and renewal processes and recommended the commission give greater priority to the development of an evaluation framework to measure the effectiveness of the Act.

Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission inquiry into housing regulation in Victoria

In 2005, the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC) conducted an inquiry into Housing Regulation in Victoria: Building Better Outcomes.

The inquiry found that, while the regulatory framework for housing regulation had served Victorians reasonably well, there was significant opportunity for improvement, particularly in establishing a more closely defined regulatory environment and improved performance reporting to enhance transparency and accountability. Specifically, the inquiry identified the need for the commission to improve its performance reporting obligations, and recommended that it publish the rationale behind its monitoring and enforcement strategy and performance indicators.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

1.5.1 Audit objective

This audit, first identified in our 2009–10 Annual Plan and initiated in December 2010, assessed the effectiveness of the building permit system in assuring approved works meet requisite building and safety standards. Specifically the audit examined how effectively:

- the Building Commission regulates the activities of municipal and private building surveyors

- councils enforce compliance with building permits.

To address the audit objective, the audit criteria assessed whether:

- building permits issued by municipal and private building surveyors comply with the Building Act 1993, the Building Regulations 2006 and the Building Code of Australia

- councils’ monitoring and enforcement practices provide reasonable assurance that building works and associated permits comply with the Building Act 1993, the Building Regulations 2006 and the Building Code of Australia

- the Building Commission’s monitoring and enforcement activities are risk-based, targeted and sufficiently informed by rigorous analysis of reliable data on the performance of building surveyors

- the Building Commission’s arrangements for monitoring, reporting on, and improving the performance of the building permit system are effective.

1.5.2 Scope

The audit examined the arrangements in place for monitoring and enforcement by the Building Commission and Building Practitioners Board of the performance of both private and municipal building surveyors.

The audit also examined the systems in place for monitoring and enforcing compliance with building permits and the Act at the following councils:

- Latrobe City Council

- Melton Shire Council

- Mitchell Shire Council

- Monash City Council.

1.5.3 Method

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

1.5.4 Cost of the audit

The total cost of the audit was $645 000.

2 Monitoring the building permit system

At a glance

Background

The Building Commission (the commission) is responsible for assuring that the building control system is working effectively, by monitoring and enforcing statutory building and safety standards. Councils also have statutory responsibilities to administer and enforce parts of the Building Act 1993 and the Building Regulations 2006 within their municipalities.

Conclusion

The commission cannot reliably assure the Minister for Planning or the community that the building permit system is working effectively as there is no framework in place either to evaluate the system or to assess whether building surveyors effectively enforce the Building Act 1993 or the Building Regulations 2006.

Findings

- The commission has yet to implement adequate arrangements for monitoring the effectiveness of the building permit system, 17 years since its establishment and 11 and six years respectively since two reviews raised this fundamental shortcoming.

- The commission, while responsible for the levy collection system, does not assure itself that all levies due have been received.

- Councils’ monitoring and enforcement activities are limited, reactive in nature, and offer little assurance that all building permits and associated works within a municipality meet statutory requirements.

Recommendations

The Building Commission should:

- expedite development of its monitoring and evaluation framework and comprehensively review the integrity of the building permit system in operation

- develop guidance for building surveyors for determining the value of building works and accurately estimating the levy payable to the commission

- clarify councils’ responsibilities for monitoring and enforcing the Building Act 1993 relating to building surveyors.

Councils should review and strengthen monitoring and enforcement strategies so they can assure building works and associated permits comply with the Building Act 1993 and the Building Regulations 2006.

2.1 Introduction

A measure of the building permit system’s effectiveness is how well it controls the construction of proposed buildings and assures compliance with building and safety standards. The Building Act 1993 (the Act) and the Building Regulations 2006 (the regulations) specify these standards and how they apply to buildings and the building permit process.

As the principal regulator of the building control system, the Building Commission (the commission) has a statutory responsibility to monitor and enforce the Act and the regulations relating to buildings, building practitioners and the building permit system.

Similarly, councils are required to administer and enforce the Act and the regulations as they relate to building permits within their municipal districts.

To discharge these functions effectively, both the commission and councils need access to accurate and reliable information on how well the building permit system is working to assure works comply with the Act and the regulations. They also need to know how well building surveyors are administering the building permit process and enforcing mandatory building and safety standards.

This information is core to enabling the commission to effectively target its regulatory activities concerning building surveyors, and for reliably assessing and improving its own performance as a regulator.

This Part of the report examines how effectively the commission and councils monitor the performance of the building permit system.

2.2 Conclusion

The commission cannot reliably assure that the building permit system is working effectively as it has no framework against which to reliably evaluate it, or assess whether building surveyors are effectively enforcing the Act and the regulations.

This means the commission cannot presently assure the Minister for Planning or the community that approved works meet requisite building and safety standards, that building surveyors are effectively discharging their statutory functions, or that its current approach to regulating surveyors is working.

Along with councils’ monitoring and enforcement activities, which are limited and reactive in nature, there is little assurance that all building permits and associated works meet statutory requirements.

This is a significant gap in the commission’s regulatory framework, first raised by this office in 2000 and reiterated more recently by the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission (VCEC) in 2005.

2.3 System-wide monitoring arrangements

The commission has statutory monitoring responsibilities relating to the building permit system. Specific functions under the Act include:

- monitoring and enforcing compliance with the provisions of the Act and the regulations relating to building and building practitioners

- monitoring developments relevant to the regulation of building standards

- monitoring the system of collection of the building permit levy.

However, the commission’s existing monitoring arrangements do not enable it to effectively carry out these functions. While it has procedures in place for individual audits, there are no defined targets, standards or documented arrangements for monitoring and assessing the effectiveness of the building permit system.

The commission’s monitoring is limited to public reporting of activities such as the number of complaints received against building practitioners, the number of audits undertaken, and consumer perceptions of building practitioners and of their building experience. These measures are drawn from the commission’s internal records and from its pulse database derived from ongoing surveys of consumers and practitioners. They offer little insight into the extent to which building surveyors adequately discharge their statutory responsibilities or the impact of the commission’s monitoring and enforcement effort.

Our 2000 audit, Building Control in Victoria: Setting sound foundations, concluded that the commission had not given sufficient priority to monitoring and evaluating the effectiveness of the Act for assuring the building control system promoted the design, construction and maintenance of safe, habitable and energy efficient buildings.

Subsequently, VCEC noted our conclusion in its 2005 report on its inquiry into Housing Regulation in Victoria: Building Better Outcomes, and similarly observed that many of the indicators based on the commission’s pulse data were not related to the commission’s objectives and performance as a regulator. Accordingly, VCEC recommended the commission review its reporting framework to assure it indicates how well it is performing against the outcomes sought by the Act.

This framework has yet to be developed, 17 years since the commission was established, and 11 and six years respectively since the above two reviews raised this fundamental shortcoming.

The commission asserted that because responsibility for building policy was transferred to the Department of Planning and Community Development (DPCD) in 2007, this meant that it no longer had responsibility for evaluating the Act. However, this is at odds with the commission’s current statutory monitoring functions, which clearly show that it retains primary responsibility for monitoring the Act in relation to the building control system.

The commission, however, commenced developing a monitoring framework in 2009. As outlined in Figure 2A, this is a long-term project, presently scheduled for implementation in June 2012.

Figure 2A

Proposed monitoring and evaluation system for regulatory decision-making

The commission is in the process of establishing a new integrated monitoring and evaluation (M&E) system to support its regulatory decision-making.

The new M&E system aims to assist the commission to monitor and evaluate the effectiveness and efficiency of the regulatory framework, and make improvements where necessary.

The commission intends to conduct a regulatory risk assessment as part of the system’s implementation phase. The aim of this assessment is to inform future priorities and direction for monitoring and evaluation.

The system is being designed so that it can be applied to the:

- performance of the regulations

- performance of the commission

- monitoring of industry performance.

Accordingly, the commission envisages that the M&E system will inform its future strategic and operational planning and that it will achieve the following outcomes:

- increased efficiency and effectiveness of regulation

- increased efficiency and effectiveness of commission operations

- reduced burden to business and consumers.

Source: Building Commission.

While the commission’s initiative to start developing the framework is positive, considerable work remains to further clarify its parameters and implementation approach.

2.3.1 Review of the regulation of building surveyors

In the absence of an effective performance monitoring framework, the commission is unable to reliably evaluate the operation of the building permit system, and therefore its effectiveness as a regulator is fundamentally compromised.

In October 2009, the commission set up a working group to identify ways of addressing problems with the operation of the Act in regulating building surveyors. The group produced a discussion paper in 2011 summarising key issues and options for changing the Act that could improve the regulation of building surveyors and the building permit system.

Specifically, the paper identifies a number of deficiencies in the way the Act applies to building surveyors that effect the commission’s regulatory activities:

- Building surveyors are required to assess the amount of building permit levy payable to the commission, to collect these payments and deposit them in the Building Administration Fund monthly. However, there are no provisions to enforce accurate reporting, nor sufficient guidance on how to accurately assess the levies payable to the commission.

- The commission lacks powers to enforce building surveyors’ statutory reporting obligations, which further impedes its ability to track levies and building activity reliably.

- Inadequate provisions for enabling a surveyor to take over work arising from permits ‘left open’ by the suspension and/or deregistration of the original building surveyor, exacerbated by surveyors’ reluctance to do so due to liability concerns.

- No provisions in the Act to transfer or delegate the functions of a registered building surveyor if they become temporarily unavailable, which can lead to delays in completing building works, in occupying dwellings and associated inconvenience to consumers and builders.

- The Act and regulations assume that a natural person enters into a contract for carrying out the functions of a registered building surveyor, but the widespread use of corporate structures inhibits determining the identity of surveyors responsible for projects.

- Gaps in the current framework enable suspended or deregistered building surveyors to continue accepting new appointments during the 60-day period until the cancellation of their registration takes effect.

- Difficulties in managing the safety risks and information gaps arising from incomplete and uncertified building works associated with large numbers of ‘lapsed’ building permits each year.

- Private building surveyors’ use of unregistered building inspectors to carry out inspections because of the high volume of permits, and limited capacity of surveyors to undertake inspections required.

While positive, the commission’s discussion paper exemplifies the need for more regular and comprehensive reviews of the system’s effectiveness, and of the commission’s actions to achieve this, as many of the issues it identifies are longstanding.

2.3.2 Monitoring building permit data and levies

The commission is responsible for monitoring the system for collecting building permit levies, but it does not have adequate arrangements for assuring it receives all levies due.

The Act requires building surveyors to calculate, collect and forward to the commission each month the building permit levy payable for the proposed building works for which they are the appointed relevant building surveyor. The levy depends on the value of the works covered by the permit.

The commission relies completely on the surveyor to accurately estimate the value of proposed building works. There are no controls governing this process and building surveyors are not required to become qualified valuers or quantity surveyors.

In the absence of authoritative guidance and systematic monitoring by the commission there is no assurance that surveyors are accurately estimating the value of building works and that all levies due are being recovered.

This absence of adequate controls within the levy collection system means that surveyors could collude with clients to minimise their fees. In addition, there are no restrictions on surveyors using levies as their own working capital until they deposit them in the Building Administration Fund.

At present, the integrity, accuracy and thus sufficiency of the levy collected and reported to the commission relies entirely upon building surveyors. There are no penalties for non-compliance with reporting requirements in the Act, only a general penalty for providing false information

Potential conflict of interest

Although the ‘owner’ technically engages the private surveyor, it is widely acknowledged that in practice this is usually arranged by the builder who may also have a longstanding arrangement with the surveyor. This situation introduces the potential for a conflict of interest to arise. The desire to achieve repeat business with builders, particularly large builders, may reduce the incentive for the surveyor to strictly enforce the requirements of the Act and accurately estimate the value of building works.

The commission has not given this issue adequate attention in its risk assessment and auditing program and therefore has not satisfactorily mitigated this risk.

Levy audits

The commission’s Levy and Building Information Unit reconciles and analyses data reported by surveyors to identify trends and anomalies. It uses the results to audit registered building surveyors for levies. These audits aim to resolve immediate or outstanding issues about the data reported to the commission, to improve the surveyor’s data collection system and educate the practitioner on the levy submission process.

While the levy audits are a positive initiative for resolving obvious anomalies in information reported, they are not able to detect unreported levies collected by surveyors because the commission presently has no means of ascertaining this information.

The commission’s discussion paper highlights its difficulties in collecting accurate building permit levies. These are summarised in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Challenges in collecting building permit levies

The commission’s 2011 discussion paper notes that, under the Act, building surveyors are required to report building activity information to both the commission and local councils. However, the payment of building permit levies to the commission depends entirely on self‑reporting by building surveyors based on the reported number of building permits they have issued. If building surveyors do not advise the commission of permits issued, their failure to pay levies owed to the commission is unlikely to be detected.

The discussion paper notes that previous investigations into the conduct of a number of private building surveyors highlighted failures to provide accurate building permit levy returns. In 2008 alone, more than $300 000 was unpaid to the commission in connection with building permits not reported during that year, and since 1997 more than $800 000 in levy revenue was unpaid.

The discussion paper reports that one unregistered practitioner had failed to remit hundreds of thousands of dollars in levy payments over a number of years. This data is based on known isolated cases and therefore the actual and potential financial losses to the commission are likely to be significantly higher, the full extent of which remains unknown.

A 2011 review of open and lapsed building permits conducted by the commission, further highlighted significant inconsistencies in reporting of permit data by private building surveyors based on a comparison of commission data with a sample of regional and metropolitan council databases. The discussion paper also highlights additional problems with the Act regarding the calculation of the building permit levy because the meaning of ‘cost of building work’, upon which the levy amount is calculated, is unclear.

These issues are further compounded by the lack of adequate enforcement powers. Failure of building surveyors to meet their statutory obligations for reporting permits issued, prescribed building activity data and collected levies to the commission each month, or their failure to remit all levies received are not offences.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The commission’s 2011 discussion paper proposed options to address these issues, requiring legislative amendment. Notwithstanding, the paper does not consider how the commission’s existing performance auditing powers could be used in the interim to reduce these financial losses. This is another missed opportunity to address this longstanding risk to revenue.

As discussed in Part 4 of this report, the commission’s statutory performance auditing functions give it wide discretion to examine the competency of any aspect of a building surveyor’s work. This can include the soundness of the building surveyor’s approach to determining the value of building works and therefore the accuracy of levies remitted. The commission’s lack of attention to this issue as part of its performance audit program is a significant missed opportunity.

Options canvased in the commission’s discussion paper include the commission taking administrative responsibility for issuing the building permit, or allowing building surveyors to issue permits only after it had given them a reference number. In either scenario, the appointed building surveyor would remain responsible for the permit assessment, but tracking of data and levies would be enhanced.

Another alternative identified in the paper is to transfer all prescribed reporting on levies to councils who then would periodically inform the commission. However, the paper considers this would require significant reforms to existing funding arrangements and administrative responsibilities.

The discussion paper does not identify the preferred option, which the commission advised will be determined following stakeholder consultation. The options it does canvass, however, could assist to minimise future financial losses and improve data accuracy and reliability regarding building activity in Victoria.

2.4 Council monitoring and enforcement

Under section 212 of the Act, a council is responsible for administering and enforcing parts 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 of the Act, and the whole of the regulations within its municipality, except where the Act expressly assigns responsibility to another party. While the Act does not explicitly ‘obligate’ councils to monitor building works and private building surveyors, it does enable them to monitor whether building surveyors have adequately discharged their functions without assuming their responsibilities for doing so.

2.4.1 Proactive monitoring versus reacting to complaints

For councils to effectively acquit their responsibilities to enforce the Act, knowledge of an offence is required. Receiving complaints from the public is one way a council can become aware of such circumstances, while proactive monitoring presents another option. While proactive monitoring is not a statutory obligation, it is a good administrative practice that can offer reasonable assurance to council that the Act is being administered and enforced effectively within its municipal district.

Councils advised, however, that they are limited in their capacity to undertake proactive monitoring and enforcement activities, as they are not funded from building permit levy revenues to do so. Consequently, councils’ monitoring and enforcement activities are limited, reactive in nature, and offer little assurance that all building permits and associated works within a municipality adequately meet all statutory requirements.

2.4.2 Role of councils in scrutinising private surveyors

Among the councils examined, there was also a lack of clarity on the extent to which their role to administer and enforce the Act within their municipalities extends to private building surveyors. For example, Monash expressed a belief that because municipal building surveyors in some circumstances can compete with private building surveyors, it would therefore be inappropriate for them to audit the private building surveyor in those circumstances. However, this issue is not relevant to a council’s statutory enforcement role under section 212 of the Act because this responsibility rests with the council and not with the municipal building surveyor.

Notwithstanding, the Act precludes a municipal building surveyor from competing with a private building surveyor in respect of any project to which that private surveyor has been appointed as the relevant building surveyor to administer parts 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 of the Act, and the regulations. Therefore, neither a municipal building surveyor nor council can compete with a private surveyor under these circumstances.

Monash advised that competition exists in so far as owners and their agents can choose which surveyor to appoint. It suggested that if a private building surveyor is appointed to act as the relevant building surveyor, and that surveyor’s work is scrutinised by the municipal building surveyor, the private building surveyor could perceive this as the municipal building surveyor seeking to undermine them and thereby encouraging the owner or agent to appoint the municipal building surveyor for future projects.

However, while it is possible that a private building surveyor may form such a perception, the design and operation of the building control system, including governance and operating context of councils renders this risk low and insignificant in practice.

First, councils operate within strict competitive neutrality obligations that preclude them from operating their building departments in a way that undermines the commercial practices of a private building surveyor. Second, the municipal building surveyor is an employee of council and thus is subject to greater governance, accountability and oversight provisions than a private building surveyor is. Further, the Local Government Act 1989 prohibits a municipal building surveyor from exercising any delegated powers, duties or functions of the council if they have a conflict of interest. The Building Act 1993, in affording the municipal building surveyor additional special monitoring and enforcement powers clearly envisages this. Further, as most councils do not operate their building departments commercially and for a profit, the risk of such a conflict occurring in practice is not significant.

All councils indicated that they do not have an obligation to ‘monitor’ private building surveyors, as the Act does not expressly state that they have this function. Councils contrasted their functions with the explicit powers given to the board and the commission to perform this role.

However, the Act does not exempt a council from discharging its statutory enforcement role when it is aware that a private building surveyor has not complied with his or her responsibilities under these provisions. This demonstrates the councils view is at odds with their statutory obligations.

2.4.3 Reviewing permits lodged by private surveyors

It was evident that the councils examined did not systematically review permit documentation lodged with them by private building surveyors or inspect associated works to gain assurance the Act is being administered effectively within their municipalities.

However, while the Act does not oblige councils to review lodged documentation it also does not prohibit them from doing so. Further, such a voluntary practice is not only permitted by the Act, but is also entirely appropriate for supporting a council to exercise its related statutory responsibility to administer and enforce the Act. For example, the systematic review of this information by a council at its own discretion can provide it with important intelligence on potentially non-compliant activities that may require enforcement action.

Additionally, if as the result of an examination, a council determines there is sufficient cause to believe the Act or regulations have been breached, this could present reasonable grounds for the council to seek to enact its statutory powers of entry to inspect associated works to gather evidence of an offence. Therefore, voluntary, proactive monitoring can provide important assurance to a council that the Act is being appropriately administered and enforced in its municipality.

Councils advised that they usually only investigate matters if there is a complaint from the public. It is widely acknowledged, however, that members of the public do not generally have the technical knowledge to determine whether building works comply with the Act, regulations and technical provisions of the Building Code of Australia. While the role of building surveyors is to make such determinations on behalf of the public, the Act in establishing the commission as the regulator, the board as a disciplinary body, and in affording enforcement powers to councils, also clearly envisages that building practitioners operating within municipalities may not always act appropriately. Hence relying on consumer complaints alone is not a reliable basis for detecting deficiencies with a practitioner’s conduct.

2.4.4 Issues impeding council monitoring

Feedback from the councils examined indicates that this reactive approach has arisen principally because of limited resources, their reluctance to pursue enforcement action due to liability concerns, and a general lack of clarity about how councils’ powers to administer and enforce the Act within their municipality extends to private building surveyors. Some councils advised that this indicates a need for greater clarity in the Act, including related guidance from the state on the exercise of their statutory enforcement powers.

Monitoring by councils is generally limited to specific issues such as pool safety and the periodic inspection of essential safety measures. While these activities are positive, they are not adequate as a councils’ statutory responsibility for administering and enforcing the Act extends to all buildings covered by parts 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 of the Act and associated regulations. All councils included in the audit indicated it would be difficult for them to substantially increase their current levels of proactive enforcement due to the limitations of their staffing and other available resources. Therefore, responding to complaints was effectively the only compliance action being undertaken.

In 2003, the Victorian Municipal Building Surveyors Group developed guidance, known as the Municipal Building Control Intervention Filter, for councils for responding to complaints involving private building surveyors. It advocates councils taking immediate action in respect to public safety matters, but that they refer other cases involving private building surveyors to the board and the commission.

All councils, except Mitchell, used the Municipal Building Control Intervention Filter as a risk assessment tool to assist in determining the appropriate action when investigating these complaints. The guidance is useful but the approach it advocates is limited by its over-reliance on consumer complaints rather than proactive monitoring by the council of the effectiveness of the building control system in its municipality.

Collaboration with the Building Commission

It is evident that significant opportunities exist for councils and the commission to work together more effectively to monitor the performance of private building surveyors and the overall effectiveness of the building permit system.

Councils’ statutory powers to administer and enforce the building permit system within their municipalities, coupled with their access to information lodged by private building surveyors about individual permits, present obvious opportunities for reviewing and using lodged information in consultation with the commission to improve administration of the local and broader building permit system.

There is no statutory requirement for councils to provide this information to the commission, unless requested by it during an audit. There are also no documented procedures, agreements, or arrangements in place between the commission and councils to monitor the performance of private building surveyors and the effectiveness of the municipal and broader building permit system. This situation is compounded by councils’ lack of clarity concerning how their enforcement powers apply to private building surveyors.

A more strategic approach involving better coordination between the commission’s and councils’ monitoring activities in this respect would significantly enhance system-wide monitoring and future audit activities.

Despite the absence of such arrangements, councils noted they already provide the commission with access to information it requests during audits to carry out its functions and monitor the performance of building practitioners and the building control system. Some also indicated they already liaise informally with the commission through their involvement with peak bodies representing building surveyors. There is little evidence, however, these avenues effectively inform the commission’s risk assessments and performance audit program, including broader monitoring and enforcement functions.

Recommendations

- The Building Commission should:

- expedite development of its monitoring and evaluation framework and clarify the targets, standards and arrangements for assessing the building permit system’s effectiveness, and the impact of related monitoring and enforcement efforts

- conduct a fundamental review of the building permit system’s effectiveness to identify and resolve the longstanding and other system-wide performance issues

- develop guidance for building surveyors on the process for determining and documenting the value of building works and thus for accurately estimating the levy payable to the Building Commission

- implement controls to prevent building surveyors from using levies collected for their working capital

- systematically audit surveyors’ estimates of the value of building works to gain assurance they are soundly based and that it is mitigating financial losses arising from any incorrect valuations

- develop and implement a strategy, in consultation with the local government sector, to enable more effective coordination with councils to monitor the performance of the building permit system and of building surveyors

- clarify councils’ responsibilities for monitoring and enforcing the Building Act 1993 relating to private building surveyors in consultation with the Department of Planning and Community Development and relevant stakeholders.

- Councils should review and, where relevant, strengthen their monitoring and enforcement strategies to assure:

- they are risk based, targeted and sufficiently informed by reliable data on the performance of the local building permit system and of the surveyors operating within it

- that building works and associated permits comply with the Building Act 1993, the Building Regulations 2006 and the Building Code of Australia within their municipal districts.