Effectiveness of the Navigator Program

Snapshot

Is the Navigator program effectively re-engaging students in education?

What we examined

- Department of Education and Training (DET’s) management of Navigator

- Delivery of Navigator in four DET areas by service providers Jesuit Social Services, Berry Street, Mission Australia, and the Northern Mallee Local Learning and Employment Network

- student outcomes.

Why this audit is important

Students who are disengaged from learning are at high risk of leaving school early. The Navigator program is designed to support Victoria’s most disengaged students aged 12–17 years. These students are often highly vulnerable with complex barriers to re engaging with school.

The program aims to reduce disengagement for students whose attendance was below 30 per cent in the previous school term, and to re-engage most of them in mainstream education with sustained attendance above 70 per cent.

DET contracts specialist youth services with expertise and resources not available in schools. These providers work with young people and their families to return students to education or training.

A Navigator pilot commenced in 2016 and it was rolled out statewide in 2021.

What we concluded

DET cannot demonstrate Navigator is an effective intervention at a program level or that it is delivered equitably.

DET’s data collection means that it cannot clearly demonstrate Navigator’s effectiveness over time. This can be improved through better data linkage and analysis.

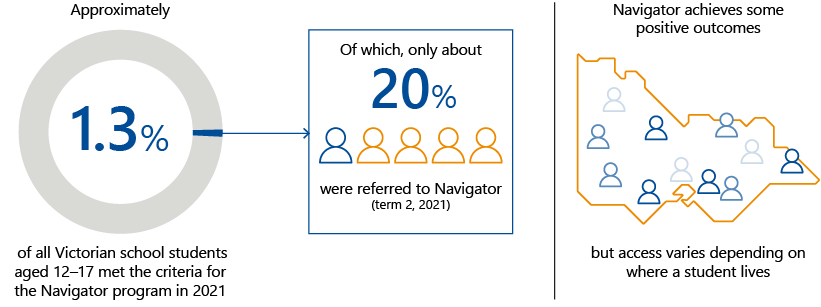

Students do not have equitable access to Navigator. Students' access to Navigator varies depending on where they live—referrals of eligible students vary across the state, as does the support students receive at school before being referred to Navigator.

Our recommendations

We made four recommendations to DET:

- three about access to the Navigator program

- one about improving the program’s effectiveness.

Video presentation

Key facts

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited agency (Department of Education and Training) and associated entities and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. Their full responses are in Appendix A.

Not all students have equitable and timely access

Referrals to Navigator vary across Victoria

Some areas refer about 40 per cent of eligible students and some refer less than 15 per cent. Statewide, the proportion of eligible students referred to Navigator is about 21 per cent.

This indicates inconsistent school practice in referring students to Navigator.

However, DET does not communicate to schools whether it expects them to refer all eligible students. DET also does not monitor referral rates to help it understand this variation.

Only a quarter of students received specialised DET support before referral

DET expects that schools will support students who disengage from their learning. It provides guidance and resources to schools to do this.

DET expects that schools will increase their support as a student’s absences increase. By the time a student is eligible for Navigator, DET expects that they have been given individualised support. Schools can use their own wellbeing resources or DET's area based and specialised support, including Student Support Services, to do this.

We found that for students referred in 2019, three-quarters had not received individualised support from DET's Student Support Services, which includes social workers, visiting teachers, psychologists and other allied health professionals. This indicates that not all schools make full use of DET’s student support programs and workforces.

It is likely Navigator is less effective when students do not receive earlier individualised support for their disengagement.

DET does not manage Navigator to meet variation in demand

Not all referred students receive timely access to Navigator. Demand for Navigator exceeds the number of available places in the program across Victoria and some students wait longer for services, depending on where they live.

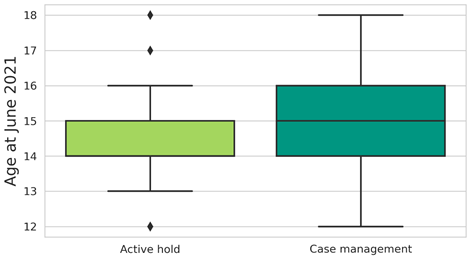

Active hold means that a student is on a wait list and receiving limited support.

Areas with much higher student numbers and with higher prevalence of chronic absenteeism have more demand for Navigator. When areas have a high number of referrals, students wait longer for their referrals to go to the service provider. It can take up to six weeks for a referral to be finalised. Once the service provider receives the referral, students in areas of high demand can be on active hold for between four and six months.

This means that students may wait a very long time before they receive Navigator’s intensive case management services. Navigator representatives at schools reported in our survey that long wait times reduce the effectiveness of Navigator and its ability to meet the needs of students. This wait time may affect a school's decision about whether to refer a student to Navigator.

DET does not use data on demand and service provider capacity to identify likely demand for Navigator or to adjust substantially how many students Navigator can support in each area.

Recommendations about access to Navigator

| We recommend that the Department of Education and Training: | Response |

|---|---|

|

1. develop a Navigator engagement strategy so that:

|

Accepted |

|

2. improve oversight and follow-up of schools to ensure consistent application of the Department of Education and Training's tiered system of support and referral practices (see Part 2) |

Accepted |

|

3. monitor program demand and uses this information for continuous program improvement, including to:

|

Accepted |

DET is not able to demonstrate how effective Navigator is at returning students to education

Very few students achieve the program target of a return to education at 70 per cent attendance for two terms. However, many Navigator students do re-engage with education at attendance rates lower than the program target and achieve a range of other positive outcomes.

We used a range of data to test Navigator’s effectiveness. Limited data collection over time and no linking between Navigator participant data and DET’s record of student attendance and achievement meant that we could not clearly assess Navigator’s effectiveness.

Limited historical data means DET does not capture all the positive outcomes Navigator students achieve

Navigator achieves other positive outcomes. These include students who increase their attendance at a lower attendance rate than Navigator's target, or older Navigator students who may exit the program to a positive pathway of training or work.

The service providers who support Navigator students see other improvements in students' wellbeing. Service providers observe that students improve their social and emotional wellbeing and have the support they need to manage difficult circumstances. They see that students who were not able to leave their bedrooms or connect with family and friends are able to socialise and begin attending school.

DET's data collection for Navigator has not been able to capture all these outcomes in detail.

DET can do more to monitor and evaluate Navigator’s effectiveness

DET does not have a clear monitoring and evaluation framework for Navigator or performance benchmarks for service providers. This means that DET also does not have a way to review program implementation to ensure that it is consistent across schools.

DET does not routinely link data from its Navigator Data Management System (NDMS) with its student attendance and achievement data. This means that DET does not have a detailed understanding of program performance over time. It also means that DET does not understand the characteristics of students more likely to be referred to Navigator and those more likely to be helped by it.

DET did not have an efficient way to collect information about student progress and outcomes before December 2019. It introduced the NDMS in 2020 but while this increased oversight it still did not capture all relevant outcomes, such as increases in attendance below the 70 per cent target.

DET has recently upgraded the NDMS and it now collects more information about students' progress and the different outcomes they achieve. This means it can better understand what Navigator is able to achieve.

It is important for DET to understand Navigator service delivery and program performance over time. It can do this by regularly analysing the full range of data collected by the NDMS and linking data with its student attendance and achievement data.

Recommendations about Navigator's effectiveness

| We recommend that the Department of Education and Training: | Response |

|---|---|

|

4. develop and implement a monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework that:

|

Accepted |

1. Audit context

Students with extremely low school attendance are at high risk of not completing their education. These students often experience many barriers to attending school and engaging with learning. They need help to overcome these barriers and stay in education.

DET provides resources and programs to schools to provide support so that disengaged students can stay at school. DET offers Navigator as a program for students when they need intensive and tailored support and have very low attendance.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 The Navigator program

Navigator is a program to reduce disengagement for students aged 12–17 years whose attendance is below 30 per cent in the previous school term. It is a program of last resort where earlier intervention for a student’s disengagement has not succeeded.

A Navigator pilot program commenced in 2016 and was rolled out statewide in 2021. Navigator is open to all students in government and non-government schools in Victoria.

Intended outcomes

Navigator aims to achieve the following outcomes:

- Re-engaging young people with education.

- Developing students with greater social and emotional capabilities.

- Supporting schools to be better equipped to engage all young people.

Outcome targets for Navigator students are defined by DET in October 2021’s Navigator Operating Guidelines (the Guidelines). Of the students who receive services:

- seventy per cent increase their attendance rate or newly enrol in an education setting, and of these 50 per cent achieve educational re-engagement

- seventy per cent report an increase in social and emotional capabilities, resilience and personal skills after receiving tailored program support.

Re-engagement is defined as 70 per cent or more attendance for two school terms or equivalent.

DET updated its Guidelines recently to state that some Navigator students may not meet the attendance target but still achieve a positive outcome of education re engagement. This may include flexible learning options and other education settings such as TAFEs or Virtual Schools Victoria where the approved curriculum is delivered.

1.2 Who Navigator is for

The Navigator program works with the most severely disengaged students in Victoria.

DET categorises students’ risk of disengagement from school according to absence patterns. Figure 1A shows how DET defines categories of student absence in its Student Attendance Guidance 2021.

FIGURE 1A: DET's categories of student absence

| Category of student absence | Days of school missed per year |

|---|---|

| Regular attendee | Up to 10 days |

| At risk of chronic absence | 10–19.5 days |

| Chronically absent | 20–29.5 days |

| Severe chronic absence | More than 30 days |

Source: DET.

Severe chronic absence (more than 30 days per year) averages to an absence of eight days or more per term. Based on an average term length of 50 days, this means the student has been absent for at least 16 per cent of the term.

Students become eligible for Navigator when they have been absent for at least 70 per cent of the previous school term. This is 27 more days in a term over and above DET's criteria for severe chronic absence.

The result of applying the absence criteria is that students eligible for Navigator are severely disengaged learners with complex barriers to education engagement. They are highly likely to need significant mental health support, disability assessment and family support services. Some Navigator students need support for trauma, family violence, sexual abuse and alcohol and other drugs.

1.3 How Navigator is delivered

DET delivers Navigator through a partnership with contracted service providers, schools and other education providers.

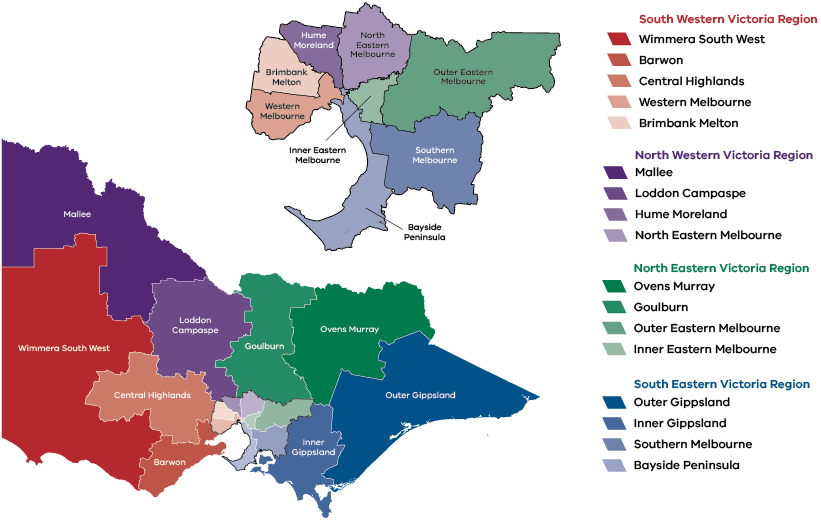

DET has a central team that manages Navigator plus Navigator coordinators who work in each of DET's 17 geographic areas. See Appendix D for a map of DET areas. The Navigator coordinator is the primary contact for service providers and manages the relationship between service providers, schools, student wellbeing area teams and other key services.

Navigator contracts specialist youth services that have expertise and resources not available within schools. There are 10 service providers delivering Navigator across Victoria, selected by DET through a competitive tender process.

Funding

DET funds Navigator based on a fixed and equal amount per area. This means that there is base funding for service delivery and a Navigator coordinator in each area. There is a central DET program management team.

DET adopted a differentiated funding model to distribute additional Navigator funding it received from government for 2021 and 2022. This funding was provided in response to COVID-19 impacts on students. DET used this to increase the number of students Navigator could support, and for extra mental health support and loadings for certain student cohorts.

DET distributed this additional funding based on average service demand for the previous two quarters and on characteristics associated with increased risk of chronic absence, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status, youth justice involvement and the number of disengaged learners in the area.

Augmented Navigator is an additional $460,000 over two years to support disengaged young people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds in southern and western Melbourne and is focused on young people at risk of offending. Because of this additional funding, these two areas receive slightly less differentiated funding.

Figure 1B shows the base and differentiated funding components, their amounts and areas for the calendar years 2021 and 2022.

FIGURE 1B: Navigator funding components per calendar year: 2021 and 2022

| Funding component | Funding amount ($) | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Base funding | 666,793 | Per area service provider (17 areas) |

| 2021 and 2022 funding boost (capacity) | 112,378 | Areas with established service provision (14 areas) |

| 53,530 | Newly expanded areas in 2021 (3 areas) | |

| 2021 and 2022 funding boost (mental health support) | 45,500 | Areas with established service provision (14 areas) |

| 21,000 | Newly expanded areas in 2021 (3 areas) | |

| 2021 and 2022 funding boost (cohort) | 100,000 | Western Melbourne Southern Melbourne |

| 116,500 | Brimbank Melton Bayside Peninsula Loddon Campaspe, Barwon, Goulburn North Eastern Melbourne |

|

| 34,625 | Hume Moreland | |

| Augmented Navigator | 215,250 | Western Melbourne Southern Melbourne |

| TOTAL funding per calendar year | 14,235,738 |

Source: DET. Difference between category subtotal and total funding is due to rounding.

Referral to Navigator

Navigator has an open referral system. This means that anyone concerned by a student's low attendance can refer them to Navigator. In practice, most referrals to Navigator come from schools.

Navigator coordinators assess the referrals and ensure that students meet the program's eligibility criteria. They also consider whether the student is ready to receive services. Students do not have to participate in Navigator; case managers must have consent from the student's parent or carer—or the student if they are a mature minor—before providing services.

Sometimes, students are in a crisis situation when they are referred to Navigator. This may affect whether they are ready and willing to respond to Navigator's support. When this happens, Navigator coordinators put in place follow-up plans so they reassess students later. Navigator coordinators confirm these deferred referrals with area-based managers.

Case management and re-engagement

Service providers use their specialist staff to connect with young people and their families where schools are unlikely to have the capacity or skills to do so.

Service providers develop a re-engagement plan for each Navigator student. This is based on the student’s learning goals and describes the school and service provider support they need to achieve those goals.

When a student is about to exit Navigator, service providers and Navigator coordinators agree on an exit plan. This plan describes the support the student has received through Navigator and the kind of school-based support they will continue receiving. This is so the student will have ongoing support to maintain their connection to education.

When a service provider receives a referral from DET, they establish contact with the student and their family or caregivers, obtain consent to participate in the program and assess the student’s needs. DET expects that service providers will be assertive in making this contact.

The core services provided by Navigator are assertive outreach and intensive case management

- Assertive outreach means that the service provider seeks out the Navigator student using its expertise in youth and family engagement to establish contact with the young person and build a relationship with them. This contact is persistent and may take different forms (phone calls, messages, home visits) until they have established contact. If multiple attempts at contact (between 4–6 occasions) are unsuccessful, the service provider advises the Navigator coordinator of this.

- Service providers deliver intensive case management services based on a young person’s needs and goals. This means that a case manager assesses and supports each Navigator student. The case manager refers students to additional services according to their needs and works closely with students to identify their education goals. Case managers advocate for students and work with schools to implement each student’s re-engagement plan.

Students may be supported with active hold services when the service provider is at case management capacity. This means that the student receives initial assessment and ongoing contact with the service provider. The provider may refer the student to other services before bringing them into their intensive case management service when capacity allows.

DET requires service providers to review students on active hold regularly. It does not specify a time limit for active hold, but Navigator coordinators work closely with service providers to monitor this.

Some service providers also offer a brief intervention service for students on active hold. This means they offer tailored and specific support to the student including counselling. This support is usually time-limited and it is not the same scope of support available through intensive case management.

1.4 DET support for student wellbeing and engagement

DET expects that schools will provide students at risk of disengaging from education with support. This means that DET requires schools to identify students with decreasing attendance and provide individualised support. This support may change over time if earlier support and interventions are not effective.

DET uses a three-tiered system of support (TSS) to categorise its student health, wellbeing and inclusion programs and interventions. At each tier, DET's area-based student wellbeing and engagement teams offer advice and resources to schools.

Navigator is a tier-three program because it provides participants with specialist and one-to-one support from community service organisations. DET expects that students referred to Navigator have previously received individualised school-based support under its tier-one and tier-two TSS services.

The tiers are:

|

Tier … |

Is … |

With these characteristics … |

|

One |

applicable to all students and based on preventative and health promoting activities |

|

|

Two |

cohort-specific, with supports and interventions including some individualised support |

|

|

Three |

highly targeted |

|

Appendix A. Submissions and comments

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix A. Submissions and comments.

Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| NDMS | Navigator data management system |

| TSS | Tiered system of support |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General’s Office |

Appendix C. Scope of this audit

| Who we audited | What the audit cost |

|---|---|

| DET, Jesuit Social Services, Berry Street, Mission Australia, Northern Mallee Local Learning and Employment Network | The cost of this audit was $685,000 |

What we assessed

The audit followed the following lines of inquiry and criteria:

| Line of inquiry | Criteria |

|---|---|

| DET’s planning, management and oversight supports service providers to deliver Navigator to eligible students | 1. DET's program design and funding model is based on a sufficient understanding of demand for Navigator and the needs of its target cohort so that eligible students have timely access to the program. 2. DET's service agreements have clear funding guidelines, deliverables, performance measures and targets to achieve Navigator's intended outcomes. 3. DET's program and service agreement monitoring, evaluation and reporting enables assessment of the achievement of Navigator’s intended outcomes and supports continuous improvement. |

| DET and service providers’ delivery of Navigator results in students re-engaging with education or training | 1. Service providers deliver intensive case management tailored to the needs of each Navigator student and identify and access additional services where needed. 2. DET and service providers involve schools in preparing student re-engagement plans and schools implement these as intended. 3. DET and service providers provide schools with guidance and support them to improve whole-of-school practices that reduce student disengagement and sustain re-engagement. 4. Navigator is achieving its stated outcomes. |

Audit scope

This was a follow-the-dollar performance audit, which means we audited DET and agencies that provide services to Victorians on behalf of DET. The audit examined DET's implementation of the Navigator program and the extent to which it is achieving its intended outcomes.

In addition to DET, we selected four of ten service providers who receive funding from DET to deliver Navigator. We chose these four services providers, listed in the table above, based on their geographic location, service provider types and the likely factors contributing to student disengagement in their area.

Our methods

As part of the audit we:

- analysed data from DET and four service providers to assess Navigator’s effectiveness

- reviewed DET’s policies, procedures and plans and assessed whether they were effectively supporting Navigator delivery

- surveyed school staff with experience of Navigator

- surveyed DET’s Navigator Coordinators

- interviewed key staff in the department and service providers.

Compliance

We conducted our audit in accordance with the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements.

Unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

Appendix D. Map of DET areas

FIGURE D1: Map of DET areas

Source: DET Region Map.