Effectiveness of Support for Local Government

Overview

The local government sector faces significant challenges and the needs of individual councils vary greatly. This audit assessed the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the support provided to councils by Local Government Victoria LGV and the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV). Support includes any activity undertaken to assist councils to carry out their duties and obligations to the community, and to facilitate more efficient and effective council operations.

LGV supports local councils to ensure they are responsive, accountable and efficient, and that they comply with the Local Government Act 1989. MAV advocates for local government interests, builds the capacity of councils, initiates policy development and advice, supports councillors and promotes the role of local government.

Both LGV and MAV have established methods for identifying council support needs. However, except in a few instances, neither is able to demonstrate whether their support activities are contributing to the effective and efficient operation of councils. LGV and MAV have worked together to deliver a number of council support initiatives, but there is scope to formalise how they will work together in the future.

Legislative and broader governance arrangements compromise the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of support to councils. MAV is not subject to the range of legislation that applies to many other public sector entities. Weaknesses in MAV's procurement practices also bring into question whether MAV's support activities provide councils with value for money. While MAV has some external accountability requirements, there has been little or no independent scrutiny of its activities. MAV has committed to address the gaps in governance identified through this audit.

PDF of further correspondence from the Municipal Association of Victoria – 1 May 2015

Effectiveness of Support for Local Government: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2015

PP No 9, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Effectiveness of Support for Local Government.

This audit assessed the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of support activities undertaken to assist councils to carry out their duties and obligations to the community. I focused on the activities of Local Government Victoria (LGV) and the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) as they are key entities providing support to councils.

I found both LGV and MAV have established methods for identifying support needs. However, with some exceptions, neither is able to clearly demonstrate how their support activities contribute to the effective and efficient operation of councils. Both LGV and MAV need to strengthen their focus on outcome reporting and evaluation. While there are examples of LGV and MAV working together to support councils, there is scope to document and formalise how they can work together in the future, including under the new Victorian State-Local Government Agreement.

Legislative and broader governance arrangements compromise the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of support to councils. MAV operates in a unique legislative environment and has not been subject to the range of legislation applicable to many other public sector entities and bodies. I have made recommendations to the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning to review the Municipal Association Act 1907 and to improve oversight of MAV. Prompt action is needed by both LGV and MAV to address the governance issues identified in this report.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

26 February 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Andrew Evans—Engagement Leader Charles Tyers—Team Leader Sophie Fisher—Analyst Sheraz Siddiqui—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Michele Lonsdale |

The community relies on Victoria's 79 councils to provide a range of important infrastructure and services. Councils face a range of critical challenges in relation to their financial sustainability, resources, capability and the increasing expectations from their communities. Any support councils receive to address these challenges is therefore crucial to enable them to operate effectively, efficiently and economically.

The Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) and Local Government Victoria (LGV) are two key bodies that provide support to councils. While the nature of support each provides differs, both have established methods for identifying the support needs of councils. However, with only some exceptions, neither can clearly demonstrate whether their support activities are making a difference to Victoria's councils. In particular, their monitoring, evaluation and reporting on support activities is not sufficient to provide assurance that intended outcomes are being achieved. My audit found that while MAV and LGV have worked together to support councils, they need to clearly identify when and how they should work together in the future. The Victorian State-Local Government Agreement potentially provides a mechanism for both LGV and MAV to identify and provide support more effectively to address council support needs.

MAV's conduct during this audit has been disappointing. It has been marked by repeated challenges to my mandate, the scope of the audit, its inability to provide evidence in a timely fashion, and sometimes its refusal to provide certain information.

For over 100 years, MAV has been a legislated public body, with much of its revenue, nearly $60 million in 2012–13, derived either directly or indirectly from taxpayers, councils or ratepayers. This audit of MAV is clearly within my mandate and it is appropriate for me to audit MAV; just like any other public body in Victoria. MAV does not appear to acknowledge or accept that it is not only accountable to its members but that it also has broader responsibilities and obligations for the efficient, effective and economic use of public funds. It is my hope that this report provides an impetus for change.

MAV claims it is unique and that my office has applied an 'agency of government lens' which is not appropriate given that it is an independent membership organisation. My office has not erred in its assessment of MAV. To the contrary, it is entirely appropriate for me to assess whether MAV's support activities are effective, efficient and economical and we set out and consulted with MAV early in this audit on our approach.

The fundamental issues about MAV are clear. Its legislation is outdated and has not kept pace with contemporary standards of good governance. This needs to be promptly addressed. In the absence of clear and comprehensive legislative arrangements, MAV has not itself sought to bridge this gap by establishing and maintaining a robust set of governance arrangements, policies and procedures. MAV also undertakes a broad range of support activities, but it is not clear whether all of its existing functions are within its legislated mandate. I note MAV's assertion that its Board is responsible for the conduct of MAV's activities. My assessment in this audit is that the Board has failed to fulfil its obligations to provide appropriate oversight of the operations, governance and performance of MAV, to the detriment of Victoria's 79 councils, Parliament and the community.

This underscores the need for a comprehensive review of MAV's role and legislation, and a clear set of expectations around MAV's role and governance in providing support to councils needs to be established. Such a review is well overdue and might well consider whether the original intent of the Municipal Association Act 1907 is still appropriate in the 21st century.

I also found that the independent oversight and scrutiny applied to MAV is well below the level that most statutory public bodies face. There is limited scrutiny of MAV's Rules, limited independent review of its performance beyond its annual reporting, and no clear understanding of whether MAV is delivering value for money. Indeed, my audit provides a rare independent and transparent assessment of MAV's performance. I have recommended that Local Government Victoria takes a much more proactive role in its oversight and monitoring of MAV's activities and performance, and advice to the minister on its performance. MAV seems to have misconstrued the need for appropriate oversight and monitoring to support the Minister's accountability for the Municipal Association Act 1907 as implying the need for the minister to direct or control MAV. However, my report is clear that overseeing MAV's performance and compliance with the Act does not require the minister to have the power to direct or control.

The tenor of MAV's response is indicative of an organisation that has not been subject to the sort of independent oversight and scrutiny of its performance and operations that the public and Parliament expect and are entitled to, and one that lacks a culture of best practice and accountability for its performance. It is not unreasonable to expect the highest standards of governance, accountability and transparency from MAV. The body charged with promoting the efficient carrying out of municipal government and watching over councils' interests, rights and privileges should be an exemplar in everything it does, and provide value for money to its members, and ultimately the people of Victoria.

I am pleased that the Department of Environment Land Water and Planning and LGV has acknowledged that my recommendations will strengthen support for local government, and has accepted all recommendations and committed to actions to address them. While I am disappointed that MAV has not clearly accepted my recommendations or outlined how it will address them, I will be monitoring developments closely in relation to these and intend to follow up with both the department and MAV to ensure that my recommendations are addressed. My office has also commenced undertaking financial audits of MAV, and will routinely assess and report on MAV's financial performance, along with the rest of the local government sector in Victoria.

I would like to thank the many council chief executive officers and Mayors who took part in my survey and participated in consultations throughout the audit. Lastly, I urge all Victorian councils to consider my report and its findings, conclusions and recommendations, and ensure that they play their part in holding MAV to account for its performance in future.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

February 2015

Audit Summary

Victoria's 79 councils are responsible for providing a wide range of services to their communities. These include child and family day care services, waste collection, home and community care, planning and recreational services. Councils also build and maintain community assets and infrastructure—such as roads, footpaths and drains—and enforce various laws.

Local Government Victoria (LGV) supports local councils to ensure they are responsive, accountable and efficient, and that they comply with the Local Government Act 1989 (LG Act). The Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) advocates for local government interests, builds the capacity of councils, facilitates effective networks, initiates policy development and advice, supports councillors and promotes the role of local government. This audit assessed the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the support provided to councils by LGV and MAV.

The local government sector faces significant challenges and the needs of individual councils vary greatly. In this audit we have defined 'support' as any activity undertaken to assist councils to carry out their duties and obligations to the community, and to facilitate more efficient and effective council operations.

Conclusions

LGV and MAV both have established methods for identifying what support councils need. However, except in a few instances, neither is able to demonstrate whether their support activities are contributing to the effective and efficient operation of councils.

LGV's support programs are generally aligned with identified needs, but are also determined by government policy objectives and linked to the requirements of the LG Act. While LGV internally monitors and reports on projects and initiatives, it could further strengthen the focus on outcomes reporting and program evaluation. Similarly, MAV's support programs are based on an understanding of needs and generally have clear objectives. However, its monitoring, evaluation and reporting is primarily focused on outputs and activity-based information, not outcomes.

While LGV and MAV have worked together to deliver a number of council support initiatives there is scope for them to work more closely to identify council needs, and decide who is best placed to provide support to councils and how. The new Victorian State-Local Government Agreement provides an opportunity to document and formalise how they can work together in the future.

The effectiveness, efficiency and economy of support to councils is significantly compromised by a lack of appropriate legislative and broader governance arrangements applying particularly to MAV. The MAV Board of Management is responsible not only for its own governance but for the good governance of the organisation. The MAV Board needs to take prompt action to address all governance gaps and deficiencies identified in this report.

MAV currently performs a broad range of support functions and it is not clear if all of these functions are within its remit or align with its intended purpose. MAV operates in a unique legislative environment and it is not subject to the range of legislation that applies to many other public sector entities and bodies. The MAV Board has not ensured there are appropriate alternative governance arrangements in place.

MAV does not have sufficiently detailed policies, procedures and processes in place to manage fraud and corruption, conflicts of interest or records. It also lacks formal systems for project management and monitoring staff performance. Weaknesses in MAV's procurement practices not only increase the potential of fraud or corruption, but also bring into question whether these support activities provide councils value for money.

While MAV has some external accountability requirements, there has been little or no independent scrutiny of its activities. This has likely contributed to MAV expanding its focus and service provision to a wide range of activities, without appropriate scrutiny and assurance.

Although it was not intended under the Municipal Association Act 1907 (MA Act) that the minister would have the power to direct MAV, the minister is nevertheless still responsible for the MA Act's administration. LGV does not actively oversee MAV's performance or compliance with the MA Act, nor proactively provide advice to the minister, except when requested to do so. LGV does not monitor whether requirements associated with exemptions granted to councils under the LG Act by the minister have been met.

Findings

Municipal Association of Victoria's legislative and governance framework

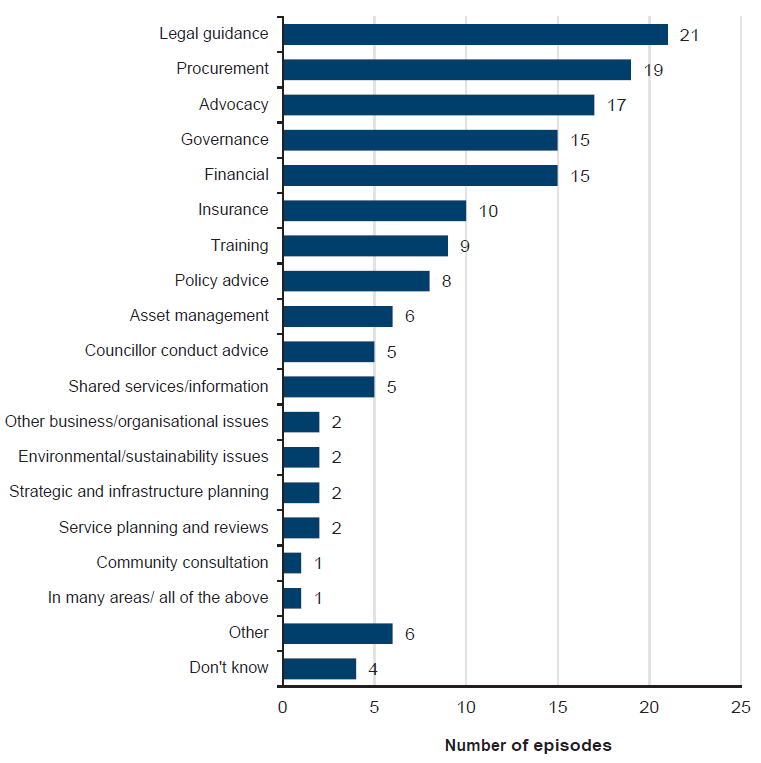

The MA Act is outdated and contains few explicit powers. It is not clear if all of MAV's current functions are within its remit or align with its intended purpose. MAV currently performs a broad range of functions, including providing procurement and insurance services, governance and legal advice, professional development and advocacy. These are predominantly provided to Victoria's 79 councils, although MAV also currently provides insurance services to Tasmanian councils and water authorities.

The MA Act enables MAV to make Rules that relate to its internal management. The MAV Rules have been used to carry out certain support activities. MAV's recent legal advice, however, suggests that it is arguable that at least one of the Rules may be outside the MA Act. The Rules also contain provisions that are traditionally only found in legislation.

The Rules can be revised at any time with the endorsement of members and the approval of the Governor in Council. Beyond this there is limited external scrutiny or monitoring of the Rules.

MAV is a public statutory authority and in a 2004 case the Supreme Court of Victoria determined that it was a body established for public purposes. There are several Acts that would ordinarily apply to public bodies including the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA), Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) and the Public Records Act 1994 (PRA). In the absence of clear and robust statutory oversight, it is the responsibility of the MAV Board to ensure that strong and transparent governance arrangements are in place.

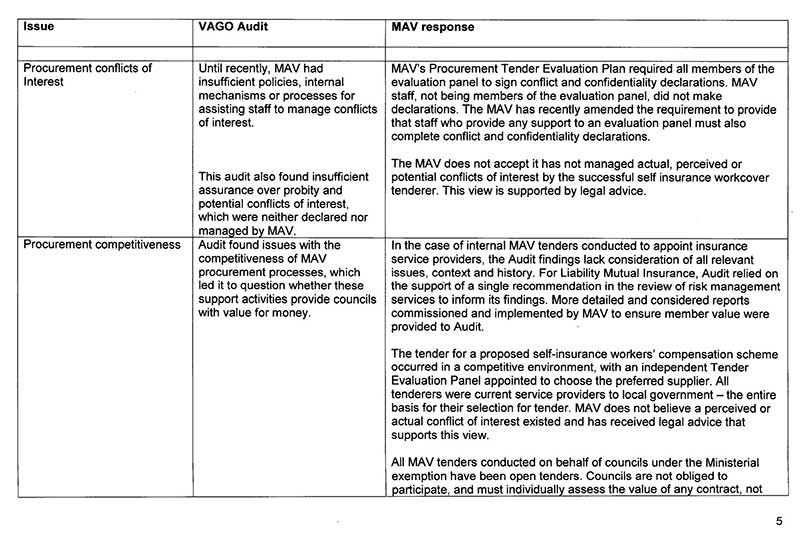

Until recently, MAV had insufficient policies, internal mechanisms or processes for assisting staff to manage conflicts of interest. In the absence of a conflict of interest policy it is not clear how MAV could have effectively managed any conflicts of interest in the past. This audit also found insufficient assurance over probity and potential conflicts of interests, which were neither declared nor managed by MAV.

MAV provided fraud awareness training for all staff for the first time in October 2014, and drafted a fraud and corruption policy at the same time. The absence of any training or guidance previously is concerning given MAV manages large procurements and contracts both for itself and on behalf of councils. Concerns over a potential conflict of interest have been addressed in Part 3.

MAV's Gifts, Benefits and Hospitality Policy is marked as having been established in June 2014. MAV advised it had a previous policy, but did not provide a copy to verify this. In any case, a March 2014 internal audit report found that the requirements of the policy were not being followed. It is important to appropriately manage these, particularly where they may relate to support activities delivered for or on behalf of councils.

From 2006 until 2014 MAV relied on an interim document management policy. While a formal records management policy has now been endorsed, MAV had difficulty locating some documents requested by VAGO as part of the audit, and was unable to provide some key documents it relied on to support its claims.

There is no formal performance management system in place for any MAV staff other than the chief executive officer, so it is not clear how staff or managers are held to account for their performance.

MAV also does not have an overarching project management framework. In relation to the delivery of grant funded activities on emergency management, project management was inconsistently applied and—while financial reporting and acquittal to LGV were completed for the projects we reviewed—reporting on project activities was limited.

MAV governance

There is no process in place for assessing the MAV Board's performance. The MAV Board is ultimately responsible for MAV's governance framework, and inadequacies in MAV's governance found in this audit, and previously, are ultimately the MAV Board's responsibility.

MAV established an audit committee in 2004 to monitor internal and external audit activities and advise the MAV Board on its governance framework. As discussed in Parts 2 and 3, internal audit activity has been limited in addressing the gaps in policy and process identified through this audit.

Municipal Association of Victoria's support for local government

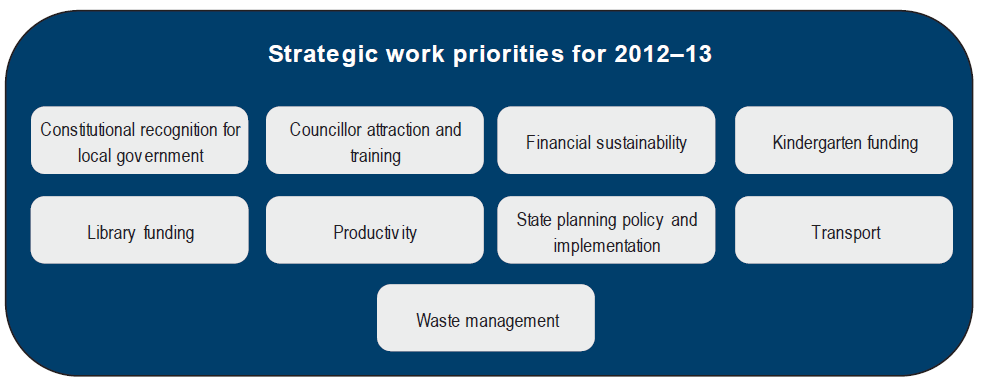

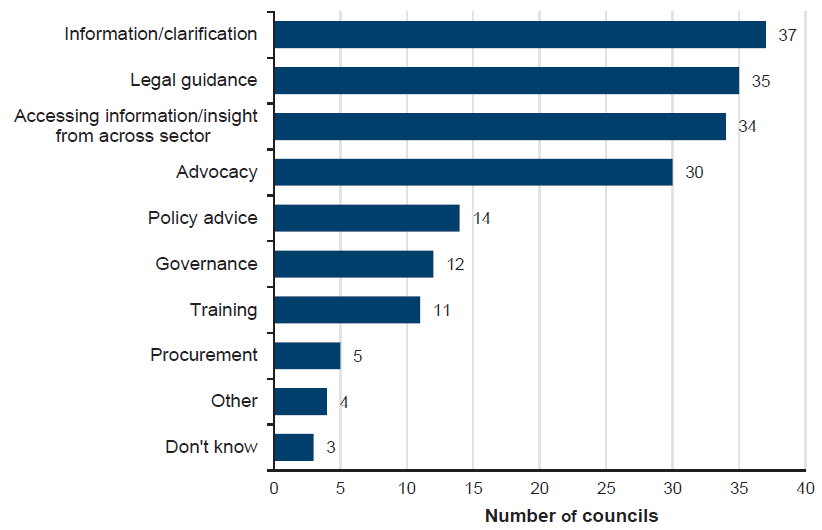

MAV has well established processes to capture feedback and identify council support needs. Over the past five years, MAV's Strategic Work Plan has identified between nine and 11 priority areas and there has been carryover from year to year of issues—including kindergarten funding, emergency management, climate change, library funding and transport and planning.

In our survey of councils, 58 per cent gave MAV a good rating, and 25 per cent a moderate rating for how they identified the type of support needed, suggesting councils are satisfied with MAV's identification of their support needs.

We assessed a cross-section of support activities.

Training and events

Councillor development, training and events have been a long standing MAV support activity. MAV delivers an extensive array and large number of events and training activities, and collects feedback on these. It cannot, however, clearly demonstrate its performance against its objective of building the capability of elected members to effectively fulfil their roles.

Emergency management

Emergency management has been identified in strategic work plans for MAV for over 10 years. Focus on this increased in response to the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires. A $2 million program of work funded by LGV was developed and delivered over four years to assist the government response to the findings of the 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission. No assessment of program impact was undertaken so value for money cannot be determined. Anecdotal feedback provided to MAV at the time of our audit, however, indicated council satisfaction with the work of MAV in relation to their delivery of emergency management projects.

Procurement

MAV Procurement is an administrative unit within MAV managing tenders for the procurement of goods and services for local councils. However, the procurement of insurance services including Liability Mutual, Commercial Crime and Self Insurance for workers compensation, which are examined in this report, are managed through separate internal processes. MAV is not subject to legislative or other and whole-of-government requirements related to procurement, and it does not have a formal procurement policy in place to guide its procurement activities. Consequently there is limited formal guidance for staff in applying probity standards consistent with established better practice.

A 2013 internal audit report found that controls in place in procurement were generally adequate but that policies and procedures governing the tendering process needed updating and revision. It also called for a formal fraud and corruption policy framework, and training for staff in this area. MAV has not completed nearly half of the recommendations detailed within the report. MAV is not undertaking procurements consistent with the standards required of councils under the LG Act, despite acting on their behalf.

Monitoring, evaluation and reporting

While MAV undertakes a wide range of reporting on support activities to members—and almost half of councils were satisfied with this reporting—it does not provide sufficient information to demonstrate the achievement of intended objectives, outcomes and continuous improvement.

MAV primarily relies on membership levels and participation rates in support programs, as well as member endorsement of its strategic work plans, to determine council satisfaction with its support provision. This is not a reliable or appropriate measure of whether objectives or intended outcomes are being achieved. MAV has acknowledged this deficiency in some areas, and is revising its approach.

In addition—with the exceptions of MAV Procurement, MAV Insurance, grants and events—MAV cannot link sources of funding with its work activities. Therefore it is difficult to determine how effectively funding has been applied to its intended purpose.

Local Government Victoria's support for councils

LGV has a range of consultation methods in place to inform the development of its support programs and initiatives for councils. Its program of sector guidance is detailed in its business plan, and linked to the relevant objective.

As well as specific programs and guidance, LGV also intervenes where council issues arise, for example, where councillors request administrative support, or where ministerial intervention is required, such as financial administrators, or dismissal of councils.

Thirty-one per cent of councils surveyed as part of this audit rated LGV as good, 43 per cent as moderate, and 12 per cent as poor, in terms of the way they identify the type of support their council needs. A question about LGV's assessment of the level of support needed indicated a similar pattern—with 28 per cent of councils providing a good rating, 20 per cent a poor rating, and 37 per cent moderate.

Main support programs

LGV has funded and delivered programs and initiatives under the Local Government Reform Strategy focused on assisting the local government sector to be more efficient and productive. It also provides additional programs and initiatives aimed at building capacity within the sector.

Our survey found a high level of satisfaction with LGV's:

- knowledge of policy and legislative frameworks—more than 80 per cent

- relevance of guidance material—80 per cent

- technical advice—more than 70 per cent.

Councils were less satisfied with LGV's engagement with councils about the effectiveness of support programs during delivery and after program completion, and the relevance of capacity building programs—all less than 40 per cent.

Objectives

LGV has objectives, project and task delivery targets in its latest Business Plan 2014–15 and reports under the State Government Budget Papers. However a strengthened focus on outcome measures beyond the limited Budget Paper reporting is required to better understand whether LGV's objectives and outcomes are being achieved.

Monitoring, evaluation and reporting

LGV does not formally report against or measure achievement of its objectives and does not have established and consistent reporting on all of its support programs and guidance. Without this, LGV cannot be assured that it is on track to achieve its objectives and outcomes.

While LGV has established practices for reviewing the progress of individual initiatives and programs, it does not have a formal outcome evaluation framework that it applies to all initiatives. While evaluations report outcomes in some cases, others consist of mainly output-based reporting. Although monitoring occurs as a component of weekly management processes, LGV should enhance the evaluation of its support programs to ensure robust analysis of outcomes and the effectiveness of support activities is understood.

Collaboration to support councils

There have been numerous instances where LGV and MAV have worked collaboratively to deliver support programs in areas such as procurement, planning and reporting, and asset management. Despite these collaborations, there are no established mechanisms to identify opportunities for collaboration.

Past VAGO audits have identified overlap in LGV and MAV support for councils. Our survey of councils found a significant number of councils—23 of 70—believed LGV and MAV duplicated each other's work, suggesting there is potential for them to be more effective by adopting a more collaborative and coordinated approach.

In September 2014, the Minister for Local Government signed the Victorian State‑Local Government Agreement. The agreement commits to the delivery of an agreed annual work plan which provides an opportunity to document and formalise how and on what initiatives LGV and MAV will work together in the future.

Monitoring of the Municipal Association of Victoria

LGV does not proactively monitor MAV's performance or compliance with the MA Act, or advise its minister on their accountability for the administration of the MA Act. LGV has advised it would only do so at the request of the minister, or in relation to a program delivered by MAV which has been funded by the state. LGV advised it limits its support to briefing the minister in relation to rule changes and the tabling of annual reports, as MAV is considered an independent entity governed by its own MAV Board. The lack of proactive monitoring of MAV means that MAV has essentially had no government scrutiny of its activities.

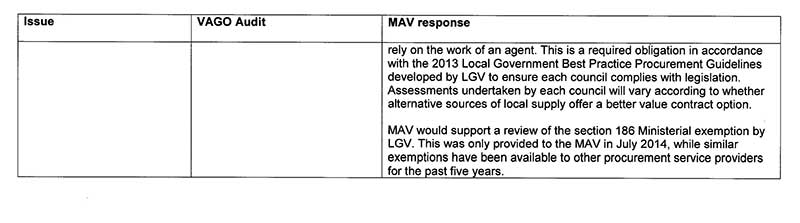

The Minister for Local Government granted an approval to councils for an exception under section 186(5)(c,) of the LG Act for contracts entered into through MAV Procurement on the basis that economies of scale and a competitive process would be achieved by them on the councils behalf. There was no monitoring of the basis on which this exception was granted, nor whether it would be achieved.

LGV recommended that the minister approve this on the basis that the contract through MAV Procurement will provide councils access to suppliers selected through a competitive process, and that leveraging the combined purchasing power of councils will result in economies of scale and savings. However, LGV does not monitor or seek assurance over MAV's procurement activities on the basis it is the responsibility of councils. Our audit found issues with the competiveness of its procurement processes, which also bring into question whether value for money is being achieved.

Recommendations

That the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning:

- as a priority, reviews and determines the Municipal Association of Victoria's functions, roles, responsibilities, powers and obligations through an analysis of its existing legal framework and:

- ensures this is reflected in the Municipal Association Act 1907

- ensures contemporary standards of governance and accountability are met, including the role, function and make‑up of the Municipal Association of Victoria's Board

- consults with relevant departments to consider whether the Public Administration Act 2004, Financial Management Act 1994 and Public Records Act 1973 should apply to the Municipal Association of Victoria either directly or through its enabling legislation

- assures itself, following any review, that all activities undertaken by the Municipal Association of Victoria are clearly within its power.

That the Municipal Association of Victoria:

-

reviews its policies and controls relating to conflict of interest, corruption and fraud, and gifts, benefits and hospitality to align with better practice, and trains its staff accordingly and proactively monitors the application of these policies and controls

-

develops and implements a performance management framework for its Board and staff that is aligned with better practice

-

develops and implements a project management framework aligned with better practice covering all project phases from initiation to completion

-

reviews and updates its records management policy to align with better practice

-

reviews its internal audit program and ensures it routinely covers all key procedures and controls associated with all aspects of procurement, conflict of interest and fraud and corruption.

-

as a priority, reviews and updates its procurement policies and procedures, so that:

- they comply with better practice

- high probity standards and appropriate controls around conflicts of interest are applied to all phases of procurements

- it actively monitors compliance with updated policies and procedure

- improves the monitoring, evaluation and reporting of its support activities, including developing relevant and appropriate performance measures, and publicly report its progress and performance

- improves councillor development, training and events evaluations to clearly measure and demonstrate their impact on participants and on council performance.

That Local Government Victoria:

-

improves its monitoring, evaluation and reporting on support activities to demonstrate the achievement of intended objectives and outcomes, including in relation to its business plan, and ensures it has relevant and appropriate performance measures, and publicly reports its progress and performance

-

develops processes to seek feedback from councils on the use of its guidance material and website information to identify opportunities for continuous improvement.

That Local Government Victoria and the Municipal Association of Victoria:

-

review and document how and when they should work together to ensure the efficient, effective and economic delivery of support to councils, including clarifying roles and responsibilities for support activities, and communicate this to councils

-

undertake regular joint strategic planning to:

- share knowledge and intelligence on council needs

- agree on council support priorities and areas of collaboration

- agree on a program of work to be reflected in the agreed annual work plan between state and local government, and local government peak bodies.

That Local Government Victoria:

-

routinely monitors the performance of the Municipal Association of Victoria including its compliance with the Municipal Association Act 1907, and advises the Minister for Local Government accordingly

-

actively monitors entities that have been granted approvals under section 186 of the Local Government Act 1994, to ensure they comply with any requirements specified in the approval, and advise the Minister for Local Government accordingly.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning and the Municipal Association of Victoria throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report, or relevant extracts to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Victoria's councils

Victoria's 79 local councils are responsible for providing a wide range of services to their communities. These include child and family day care services, waste collection, home and community care, planning and recreational services. Councils also build and maintain community assets and infrastructure—such as roads, footpaths and drains—and enforce various laws. The local government sector faces significant challenges and the support individual councils need varies according to factors such as location, size, demographics, capability and capacity.

In Victoria, there are five types of councils. There are 17 inner metropolitan councils, 14 outer metropolitan councils, 11 regional councils, 16 large shire councils, and 21 small shire councils. As of 1 July 2015, a new municipality—Sunbury City Council—will be in place.

1.2 Support for local government

For the purpose of the audit, 'support' is defined as any activity undertaken to assist councils to carry out their duties and obligations to the community, and to facilitate more efficient and effective council operations. Support may include providing advice, advocacy, guidance, and services such as training.

This audit focused on support provided to Victoria's councils by Local Government Victoria (LGV) and the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV).

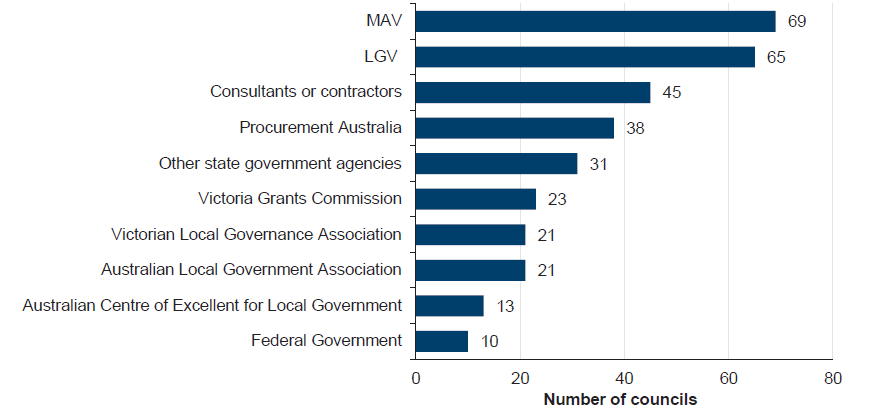

However, councils also receive support from a range of other bodies in Victoria and nationally, including various government departments, local government peak bodies and specialist organisations providing training and support in areas including procurement, planning, financial and asset management, and local government service delivery.

1.3 Local Government Victoria

1.3.1 Role and purpose

LGV is now part of the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning. It works cooperatively with Victoria's 79 local councils to ensure that Victorians enjoy responsive and accountable local government services, and aims to improve business and governance practices that maximise community value and accountability.

LGV provides policy advice to the Minister for Local Government, who is responsible for administering the following principal Acts:

- Local Government Act 1989 (LG Act)

- Local Government (Rural City of Wangaratta) Act 2013

- Local Government (Brimbank City Council) Act 2009

- City of Melbourne Act 2001

- City of Greater Geelong Act 1993

- Libraries Act 1988

- Victoria Grants Commission Act 1976

- Municipalities Assistance Act 1973

- Municipal Association Act 1907(MA Act)

- Prahran Mechanics' Institute Act 1899.

The minister also acts as an advocate for local government issues within government and, through LGV, supports and monitors the system of local government. The minister is not directly involved in the detailed management of individual councils.

Figure 1A

LGV's structure

|

LGV is made up of three business areas, with 32.5 full time equivalent staff in 2014–15, and total funding of $56.34 million. Sector Development Provides policy advice relating to sector effectiveness and relations between state and local government in order to benefit communities. Governance and Legislation Supports good governance by providing contract and procurement guidelines, as well as providing policy advice to the minister and overseeing local government elections, and preparing legislative proposals and conducting investigations. Funding Programs Responsible for policy and funding advice for public libraries, National Competition Policy compliance and the management of the Victoria Grants Commission. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on a review of LGV materials.

1.3.2 Main types of support

LGV supports councils to ensure that the system of local government is responsive, accountable and efficient, and that councils comply with the LG Act. The LG Act sets out the basis for local government in Victoria and the primary objective of councils, which is to endeavour to achieve the best outcomes for the local community while considering the long-term and cumulative effects of decisions.

Support is delivered through government programs, grants, better practice guidelines and templates as well as direct instructional circulars and responses to queries and requests for information. LGV also supports the minister with advice on the administration of the LG Act and other Acts the minister is responsible for. LGV's support activities are discussed further in Part 4.

1.4 Municipal Association of Victoria

1.4.1 Origins, role and purpose

MAV was established in 1879 as a membership association and incorporated under the MA Act. MAV's role and purpose is defined in the MA Act as promoting efficient local government throughout Victoria and watching over and protecting the interests, rights and privileges of councils. Under the MA Act, MAV is required to represent all Victorian councils, regardless of whether they are financial members of MAV. However, as MAV has advised, its relationship as a peak organisation with its members is not defined by statute. The MA Act provides for MAV to be constituted by representatives of all Victorian councils who may be appointed by their councils from time to time. Council membership with MAV is discretionary, as is participation in the insurance schemes, financial and procurement arrangements MAV facilitates for the sector and in events and training activities. Incorporation enabled MAV to insure councils through the Municipal Officers Fidelity Guarantee Fund (fidelity fund). This provides insurance to indemnify councils against fraudulent or dishonest acts committed by an employee or third party acting alone or in collusion with others.

The MA Act provided for MAV to make Rules for the management of MAV, regulation of its proceedings, fixing annual subscriptions to MAV and for fixing the contribution rate to the fidelity fund. The second reading speech for passing the legislation through Parliament in 1907 noted that the minister would not have the power to direct MAV.

There have been a number of amendments to the MA Act which amended or expanded MAV's legislated mandate in relation to insurance for water and sewage authorities and local government.

MAV provides public liability and professional indemnity insurance through its Liability Mutual Insurance (LMI) Scheme which was established in 1993. The LMI established and maintained by MAV is approved under section 76A(3) of LG Act which requires that councils take out and maintain insurance cover. The fidelity fund is now known as the Commercial Crime Fund (CCF). Both the LMI and CCF are non-discretionary mutual insurance schemes that are intended to exist solely for the purposes of their members. MAV is currently working to become a self-insurance licence holder and has sought the assistance of a third party with the application process.

1.4.2 Current activities

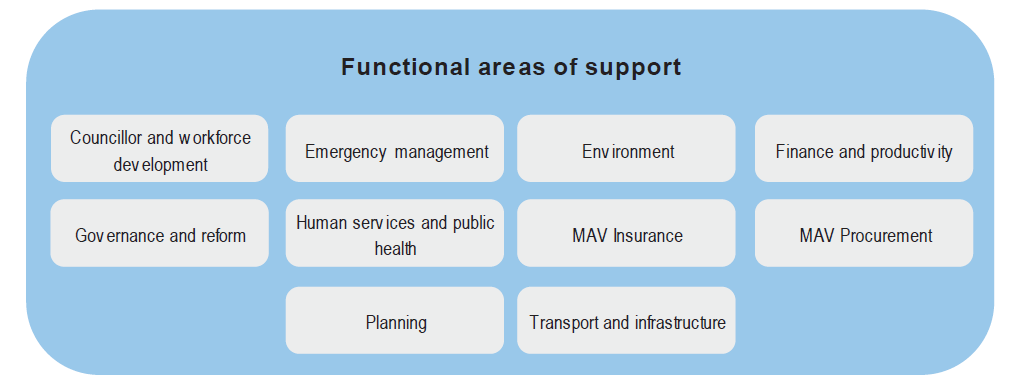

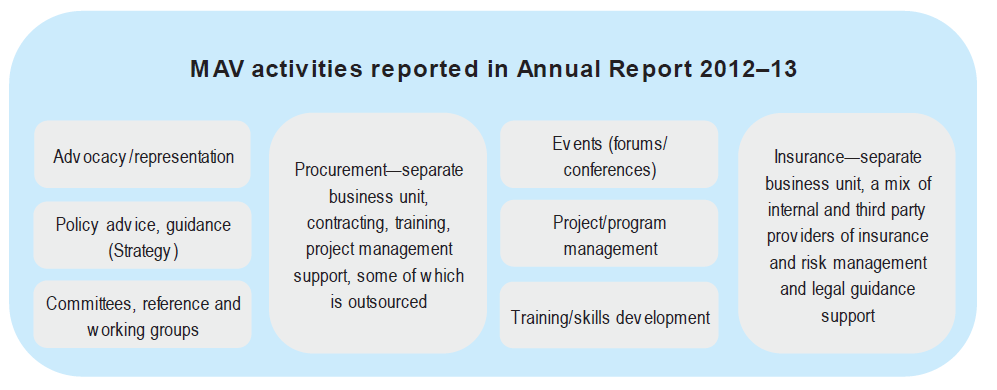

MAV provides a wide range of services across a range of portfolios and interests. These are outlined in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

MAV's stated role and services

|

MAV's stated role

MAV's services as listed on its website

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.4.3 MAV structure and governance

Management

The MAV Rules provide for the creation of a CEO position, to be appointed by the MAV Board of Management. The CEO's role is to manage the association, deliver its strategic work plan, and to be responsible for the day to day management of MAV. The CEO is subject to direction from the MAV Board, and has approximately 30 staff. MAV also engages a range of consultants and contractors. Work is structured into the numerous business areas identified in Figure 1C.

MAV Board

The MAV Board is comprised of a president, elected by State Council members, and 12 representatives elected by their respective MAV regional groupings. MAV advised that the MAV Board is elected for a term of two years. The MAV Board is empowered by the MAV Rules to set service standards and publish codes of practice and protocols. The MAV Board is made up entirely of elected councillors.

State Council

The State Council is a body consisting of all the representatives of councils that are financial members of MAV. The State Council meets twice annually and its powers include:

- determining the MAV Rules

- electing the president and other members of the MAV Board

- determining MAV's strategic direction

- appointing an auditor.

MAV's legislative and governance framework is discussed further in Part 2.

Figure 1C

MAV's structure

|

Legal Governance and Corporate Includes the Deputy CEO and General Counsel, Governance and Legislation Adviser, MAV Insurance Counsel and corporate services functions. Insurance Manages MAV insurance activities and claims services. Commercial services Includes MAV Procurement—which undertakes some procurements for MAV itself and group procurements on behalf of Victorian councils—and Events and Training—which provides training for councils and manages MAV events, such as conferences. Policy Includes policy areas which support councils including social policy, emergency management, planning, building and infrastructure, environment and economics. Policy areas vary depending on the priorities of MAV. Communication Responsible for MAV communication activities such as council communications and website administration. Hosted organisations Provides support to organisations including the Public Libraries Victoria Network, Association of Bayside Municipalities, Local Government Information Communications and Technology, and Rural Councils Victoria. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on a review of MAV materials.

1.4.4 Overview of funding and financial position

MAV's financial report comprises the economic entity of MAV and its controlled entities—the LMI, the Commercial Crime Fund and MAV Procurement.

Figure 1D provides details of MAV revenue, expenditure and financial position for the combined entity and MAV General—which excludes insurance operations—for the two financial years ending 30 June 2013 and 30 June 2012.

Figure 1D

MAV's combined financial details for the 2012–13 financial year

|

MAV combined financial details |

Combined $ million |

MAV General $ million |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2012–13 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2011–12 |

||

|

Revenue |

59.199 |

48.482 |

18.019 |

15.461 |

|

|

Expenses |

64.521 |

52.508 |

17.709 |

18.206 |

|

|

Net surplus (deficit) |

(5.322) |

(4.026) |

0.309 |

(2.745) |

|

|

Current assets |

91.341 |

84.682 |

10.274 |

8.822 |

|

|

Non-current assets |

48.806 |

54.473 |

0.574 |

0.723 |

|

|

Current liabilities |

58.791 |

49.790 |

5.545 |

4.696 |

|

|

Non-current liabilities |

76.308 |

78.996 |

1.000 |

0.855 |

|

|

Total equity |

5.047 |

10.369 |

4.304 |

3.994 |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on published MAV financial statements.

Figure 1E shows the components of MAV's revenue and expenses.

Figure 1E

MAV combined financial details for the 2012–13 financial year

|

2012–13 |

2011–12 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

MAV revenue |

59.199 |

48.482 |

|

MAV general activities |

16.892 |

14.356 |

|

Commonwealth and state grants |

8.293 |

4.951 |

|

Council subscriptions |

2.540 |

2.411 |

|

MAV Insurance revenue |

||

|

Premiums from scheme members for policy cover |

24.187 |

21.924 |

|

Reinsurance and other recoveries related to insurance claims |

15.941 |

8.834 |

|

MAV General Fund expenses |

17.709 |

18.206 |

|

Grants payments and expenditure on various projects |

7.711 |

7.160 |

|

Salary costs |

5.746 |

6.022 |

|

MAV Insurance expenditure items |

||

|

Payments for insurance claims |

26.749 |

14.406 |

|

Reinsurance expenses |

13.509 |

13.327 |

|

MAV General |

||

|

Surplus (deficit) on its operations |

0.309 |

(2.745) |

|

Combined entities overall position |

||

|

Operating loss |

(5.322) |

(4.026) |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on published MAV financial statements.

In 2012–13, MAV General achieved a surplus on its operations of $0.309 million, while the combined entities incurred an operating loss of $5.3 million. The difference between the results is mostly from the LMI component. The revenue from LMI was enough to cover its expenses with a surplus of $0.2 million, however, this was not enough to cover the administration and general expenses of $7.7 million. For the three years from 2009–10 to 2011–12 the MAV combined entities had operating losses of around $4.6 million, $0.6 million and $4.0 million respectively. Similar to 2012–13, this is a result of the insurance activities and other income not covering the administration and general expenses. In addition, for 2011–12 MAV General incurred a $2.7 million deficit, largely due to the decreased grant income in comparison to preceding and subsequent years.

1.4.5 Main types of support

Support from MAV to local government is delivered through policy and governance advice, advocacy, training, insurance and procurement across a range of portfolios and interests. MAV's support activities and projects vary from year to year and priority areas are informed by consultation with MAV member councils. Two areas have dedicated business units within MAV—procurement and insurance.

A selection of MAV support activities are discussed further in Part 3.

1.5 Other support organisations

In addition to LGV and MAV, a range of other organisations provide support to local councils in Victoria. These organisations have been consulted in the early stages of this audit but are not subject the subject of this audit.

1.5.1 Local Government Professionals

Local Government Professionals (LGPro) is the peak body for local government professionals in Victoria. LGPro provides advocacy and influences policy direction to the local government sector. LGPro is governed by a Board comprising of 10 officers who are elected by the members for a three-year term. LGPro has collaborated on procurement support with LGV, and produced the Good Governance Guide in conjunction with LGV, MAV, and the Victorian Local Governance Association.

1.5.2 Local Government Finance Professionals

Local Government Finance Professionals (FinPro) is the peak body for finance professionals within the local government sector in Victoria. It has over 400 members from various local government councils, regional library corporations and other organisations. FinPro is affiliated with Certified Practicing Accountants (CPA) Australia and represented on its Public Sector Committee.

FinPro aims to improve standards of accounting and financial management in local government by providing education and training. FinPro also represents its members in policy making fora and advocates on their behalf.

1.5.3 Victorian Local Governance Association

The Victorian Local Governance Association (VLGA) is a peak body linking local government, councillors and community leaders to build and strengthen local governance and democracy through increased collaboration. VLGA's members include local governments, community organisations and individuals. Created in 1994 and incorporated in 1995, the VLGA advocates for democracy and governance at the local government level. It also provides training and advice to the sector through various programs and projects. The VLGA Board manages the overall affairs of the association.

1.5.4 Australian Centre for Excellence for Local Government

The Australian Centre for Excellence for Local Government (ACELG) is a national local government research and policy institution funded by the Commonwealth Government. ACELG's mandate is to enhance professionalism and skills in local government, showcase innovation and facilitate policy debate. It provides support in a broad range of areas including research and policy foresight, innovation and best practice, governance and strategic leadership, organisation capacity building, rural-remote and Indigenous local government, and workforce development.

1.5.5 Institute of Public Works Engineers Australasia

The Institute of Public Works Engineers Australasia (IPWEA) is an association of council engineering professionals and provides guidance and training in asset management, sustainability, road safety, land development, and fleet and plant management.

1.6 Previous VAGO audits

VAGO has undertaken 10 audits over the past five years that have focused specifically on issues in the local government sector. These have highlighted weaknesses in current local government arrangements, and opportunities for councils to receive additional support to assist them in achieving their objectives.

Shared Services in Local Government, May 2014

This audit found that LGV had delivered shared services grant programs, and provided a range of support and guidance to the sector to facilitate shared services initiatives, mainly in relation to procurement. Procurement activities had generally been positive and promoted collaboration among councils. The audit also found that LGV could build on its existing work to assist the sector to realise the benefits of shared services. The audit recommended that LGV should continue to improve the evaluation of its programs and the collection and sharing of information.

Asset Management and Maintenance by Councils, February 2014

This audit found that LGV provides a range of guidance to assist councils in asset management practices. LGV guidance on asset management was found to be out of date, and did not address common challenges. The audit recommended that LGV should review and update its guidance and supplement it with other initiatives and types of support. It found that LGV and MAV could improve their joint work in asset management.

Organisational Sustainability of Small Councils, June 2013

This audit found that LGV provided a range of general guidance and support to councils, and it had implemented actions to assist small councils at high risk of sustainability issues. It found that LGV monitors and reports on the sustainability of councils and has implemented actions to address specific issues at small councils that are in critical situations, and although it provides a range of guidance and support related to sustainability, it could more proactively target small councils with appropriate support and advice before their situation becomes critical.

Rating Practices in Local Government, February 2013

This audit found that LGV did not proactively support councils on their rating practices, or monitor and report on their performance in this area, including their compliance with the LG Act. While LGV provided a range of guidance on rating practices, it required updating. The audit found that there was not a good understanding of the role of LGV on the behalf of councils, and clearer communication was needed. Since this audit LGV has revised its guidance material and in 2014 published revised guidance in the form of the Local Government Better Practice Guide – Revenue and Rating Strategy.

1.7 Audit objective and scope

The objective of this audit was to assess the effectiveness, efficiency and economy of support provided to councils. Specifically whether LGV and MAV:

- have governance arrangements that clearly identify roles, responsibilities and accountabilities for providing support to councils, and that these are consistent with their organisational purpose

- effectively identify and assess the needs of councils, and this informs the planning and delivery of support programs and activities

- effectively coordinate the development and delivery of support programs and activities, where appropriate

- effectively monitor, evaluate and report on the performance of support programs and activities to demonstrate the achievement of intended objectives and outcomes.

1.8 Audit method and cost

The audit included interviews with LGV and MAV staff, and a review of business planning, project planning and implementation documents, the relevant legislation and Budget Papers. A survey of all of Victoria's 79 councils focusing on the effectiveness of support provided by LGV and MAV was also undertaken. The survey had an 89 per cent response rate. Appendix A provides an overview of the survey results.

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of this audit was $540 000.

1.9 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines MAV's legislative and governance framework

- Part 3 examines MAV's support for local government

- Part 4 examines LGV's support for local government

- Part 5 examines collaboration and oversight

- Appendix A provides an overview of the statewide survey results.

2 Municipal Association of Victoria's legislative and governance framework

At a glance

Background

Governance relates to how organisations are directed, controlled and held to account. The Municipal Association Act 1907 (MA Act) is the statute governing the Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV). To effectively, efficiently and economically support councils, MAV needs a governance framework that is aligned with its legislative requirements and contemporary better practice principles and standards. It is the MAV Board's responsibility to ensure that there are appropriate governance arrangements.

Conclusion

MAV currently performs a broad range of support activities but it is not clear if all of these are within its remit or align with its intended purpose. The MA Act is outdated and does not provide sufficient detail and clarity about governance arrangements. The effectiveness, efficiency and economy of the support provided to councils is significantly compromised by a lack of appropriate legislative and broader governance arrangements applying to MAV. MAV does not have adequate systems and processes for good governance consistent with contemporary standards of public administration.

Findings

- The MA Act has not been comprehensively reviewed since it was introduced.

- It is not clear whether all of MAV's existing functions are within its legislated powers.

- It is arguable that at least one MAV Rule is not within the power set out in the MA Act.

- MAV has poor controls for fraud, corruption and conflicts.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning reviews MAV's functions, roles and responsibilities and routinely monitors MAV's compliance with the MA Act.

- That MAV reviews and updates policies and controls for fraud, corruption and conflicts of interests.

2.1 Introduction

Good governance assists public sector organisations to perform their roles effectively and efficiently and to respond to a changing environment. The Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC) defines governance as:

'processes by which organisations are directed, controlled and held to account. That is, the processes whereby decisions important to the future of an organisation are taken, communicated, monitored and assessed. It refers to the authority, accountability, stewardship, leadership, direction and control exercised in the organisation.'

To be effective, efficient and economical in its provision of support to councils, Municipal Association of Victoria (MAV) needs a governance framework based on contemporary better practice principles and standards.

The Municipal Association Act 1907 (MA Act) is the statute governing the responsibilities and powers of MAV. The MA Act also gives MAV the power to make Rules covering a range of governance issues, such as regulating its proceedings and fixing its subscription rates.

MAV has had a role in promoting good governance in the local government sector, and in 2012 it produced a Good Governance Guide to assist councils to govern better, with Local Government Victoria (LGV) and the Victorian Local Governance Association and the Local Government Professionals. The guide outlines the characteristics of good governance:

- accountable

- transparent

- following the rule of law—decisions are consistent with relevant legislation and common law

- responsive to needs

- equitable and inclusive.

2.2 Conclusion

The MA Act has not been comprehensively reviewed since its inception in 1907. MAV currently performs a broad range of functions and it is not clear if all of these functions are within its remit or align with its intended purpose. While the intent for MAV to support councils is clear in the MA Act, the scope is open to interpretation. MAV operates in a unique legislative environment and its governance model is unusual in that it is not subject to the range of legislation that applies to many other public sector entities and bodies. While MAV has some external accountability requirements, there has been little or no scrutiny of its activities. This has likely contributed to MAV expanding its focus and service provision to a wide range of activities which may be outside its remit and intended purpose, as discussed in Part 5.

MAV does not have adequate systems and processes for good governance consistent with contemporary standards of public administration. The absence or underdevelopment of these systems and processes undermines MAV's ability to efficiently and effectively support councils. Until recently, MAV did not have formal policies, procedures and processes in place to manage fraud and corruption or conflicts of interest, increasing the risk of fraud or corruption associated with MAV activities, including procurement.

The MAV Board of Management is responsible for MAV's governance and conduct. A lack of good governance is ultimately the responsibility of the MAV Board.

2.3 Municipal Association Act 1907

2.3.1 Requirements under the Act

MAV currently performs a broad range of functions, however, is not clear if all its functions are within its remit or align with its intended purpose. Under the MA Act, MAV's functions can be derived from three sources:

- Explicit powers—for example, section 2(3) in the MA Act which allows MAV to lease property, section 4 enabling MAV to establish a Fidelity Guarantee Fund and section 14 to establish and keep a local government investment service fund.

- Implicit powers—for example, powers arising from the context of the passage of the MA Act such as the preamble in the MA Act, and the 1907 second reading speech to the Municipal Association Bill.This would include the power to act as a representative of the municipal councils to protect their rights and interests.

- Other implicit powers—for example, powers that are implied as necessary to enable the MAV to carry out its explicit functions under the MA Act.

The MA Act contains few explicit powers, except for requiring MAV to establish and manage public liability and professional indemnity insurance, a Fidelity Guarantee Fund and to establish and keep the Local Government Investment Service Fund. There is no explicit power under the MA Act for it to undertake a range of its existing activities. It therefore becomes necessary to consider whether individual activities fall within the statutory objects of the MA Act, which can be a difficult question of characterisation. For example, in order to be valid, any professional development activity undertaken by MAV must have the purpose of building local government capacity or improving efficiency.

The MA Act sets out the objectives of MAV in the preamble which itself forms part of the Act rather than in a separate 'objects' clause of the Act as is now standard drafting practice. Section 3(1) of the MA Act allows MAV to establish Rules that relate to its internal management, and these Rules include a statement of the MAV's objectives. The objectives of MAV as described in Rule 1 include such activities as to 'promote local government and improve community awareness of the capacity of local government throughout Victoria to act effectively and responsibly' (Rule 1.1.1). MAV also aims to provide 'targeted advocacy to governments and relevant organisations' (Rule 1.1.4.1). It is not clear how many of these objectives in the Rules fall within the power in the MA Act which is discussed in Part 2.3.2 of this report.

The MA Act requires the separation of accounts for MAV's insurance scheme and fidelity fund, the certification of all accounts by the treasurer of MAV—a position abolished in 1996 by a change to the Rules—and the independent audit of those accounts. MAV's only external reporting requirement is tabling these accounts in Parliament, although MAV has chosen to table an annual report covering all of its activities in Parliament each year. From our evaluation of MAV support activities, the current reporting provided does not provide a measure of performance against its stated objectives.

MAV also currently provides insurance services to Tasmanian councils and water authorities, and this role is not explicitly defined in the MA Act. MAV has advised that it believes the provisions in the MA Act are broad enough to cover this function.

In response to this audit, MAV sought written legal advice in November 2014 about whether its existing support activities and 2013 Rules are within the powers set out in the MA Act. It has not sought general advice on the MA Act, its role, purpose and activities since 1998, despite taking on a range of new functions, including group procurement. For example, MAV recently established a $240 million Local Government Funding Vehicle to establish a municipal bond market in Australia which provides councils access to fixed rate, interest only loans.

MAV received written legal advice in December 2014, which raised doubts about whether some of MAV's specific activities are authorised under the MA Act. The advice suggests that this may be an error in amending the Act. Prior to 1971, there was a general power in the Act. This power was removed by amendments that year. The advice further recommends that MAV take steps to seek amendment to ensure all of its current activities are expressly provided for within the MA Act.

In April 2013, LGV provided advice to the government that noted that MAV had taken on additional and wider functions that are not included in the current MA Act, including:

- providing group commercial services, including for procurement

- providing the sector with policy positions supporting council priorities and needs

- providing capacity building for councillors

- facilitating communication and networking between councils, and between councils and other tiers of government.

This advice also noted that the MA Act has never been comprehensively reviewed since its enactment and that it was therefore outdated in both its drafting and key content around MAV's role and functions. This advice was not provided to or discussed with MAV.

2.3.2 Rules

Section 3 of the MA Act enables MAV to establish Rules that can cover:

- the management of MAV (section 3(2)(a))

- the regulation of its proceedings (section 3(2)(b))

- fixing the amount to be paid for subscription annually to MAV by each municipality (section 3(2)(c))

- the regulation and management of, and fixing the rate of contributions to, the Municipal Officers Fidelity Guarantee Fund and the terms and conditions upon which the benefit of such fund shall be available (section 3(2)(d))

- generally all matters whatsoever affecting the management of MAV so long as it is not inconsistent with the laws of Victoria (section3(2)(e)).

These Rules have been used to amend MAV's governance structure in the past and the current version is endorsed through the State Council. The most recent amendments to the Rules were in 2013, 2008 and 2006. Through the Rules the role of State Council, positions of MAV Board representatives and chief executive officer (CEO) have been established.

The Rules can be revised at any time with the approval of a 60 per cent majority of council members at State Council and become Rules of the Association following Governor in Council approval. There is otherwise limited external scrutiny or oversight of the Rules as they are neither 'statutory Rules' nor 'legislative instruments' and therefore not of a legislative character. For example, changes to MAV's Rules are not required to be reviewed by the Parliament's Scrutiny of Acts and Regulations Committee which is responsible for scrutinising bills introduced into Parliament, as well as regulations and other legislative instruments to ensure that they meet certain minimum standards. These instruments must be within power and not adversely impact certain rights. Subordinate legislation is ordinarily reviewed by this committee. MAV's written legal advice from December 2014 states that the Rules do not fall within the meaning of 'statutory Rules' or 'legislative instruments' and that the requirements, as detailed above, of the Subordinate Legislation Act 1994 do not apply to the MAV Rules.

MAV's legal advice also suggests the MAV Rules are unique, and are not of a legislative character as they relate to the internal management of MAV. This advice also suggests that Rule 1.2, which allows MAV to 'exercise functions and powers which are necessary or convenient for it to carry out its objectives', may go beyond the management of MAV and may arguably be outside the MA Act.

Rule 1.2 is a type of power usually found in legislation, rather than in an instrument such as the MAV Rules.

Some of MAV's existing support activities are found in the objectives set out in the Rules, such as its role to 'act as the representative body of local government for the purpose of promoting effective inter-government cooperation'. MAV's legal advice states that whether a particular activity is within the MA Act depends on its character. The advice also confirms that the Rules cannot confer additional powers where they are otherwise absent from the MA Act.

Given MAV's limited external accountability and reporting requirements, it is important that LGV provide effective support and advice to the Minister for Local Government regarding responsibility for the MA Act. LGV's role in monitoring compliance with the MA Act is discussed in Part 5.

2.4 Applicability of other relevant Acts

MAV is a public statutory authority and a 2004 case in the Supreme Court of Victoria determined that it was a body established for public purposes. There are several Acts that would ordinarily apply to public bodies but most of these do not appear to apply to MAV. MAV has not sought written formal legal advice on this matter. Regardless, MAV should be subject to similar best practice governance arrangements, either in its legislation or its own established governance arrangements.

Public Administration Act 2004

A key purpose of the Public Administration Act 2004 (PAA) is to provide a framework for good governance in the Victorian public sector and in public administration generally in Victoria. The PAA does not apply to MAV as it does not fall within its definition of a 'public entity'. As such, MAV Board members are nominated from among the elected representatives of member councils. Alternatively, under the PAA at least half of these positions, equivalent to a Board of Directors, would be nominated by either the Governor in Council or the minister.

Financial Management Act 1994

The purposes of the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) are to:

- improve financial administration of the public sector

- make better provision for the accountability of the public sector

- provide for annual reporting to Parliament by departments and public sector bodies.

Of particular note, the FMA requires particular entities to prepare, and have audited general-purpose financial statements in accordance with applicable Australian Accounting Standards. These financial statements provide an acquittal of an entity's stewardship of its finances. Although not required, MAV annual reports have been prepared in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards. MAV also reports compliance with Australian financial services licence requirements as a business providing financial services. MAV Insurance is not subject to the Insurance Act 1993 or the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). Consequently it is not subject to the oversight which ordinarily applies to insurance companies.

MAV has not sought written formal legal advice as to whether it is subject to the FMA. LGV should liaise with the Department of Treasury and Finance to consider whether MAV should be subject to the FMA.

Public Records Act 1973

In August 2005, MAV sought advice from the Public Record Office of Victoria (PROV) as to whether it was required to comply with the Public Records Act 1973 (PRA). PROV advised that MAV is not considered to be a public office in accordance with the PRA and therefore falls outside the jurisdiction of PROV.

In 2014 MAV established a records management policy. Prior to this, a documentation policy and procedures manual was in place from 2006. Throughout this audit MAV has been unable to locate and provide information on a timely basis.

2.4.1 MAV governance

MAV Board

The MAV Board's key responsibilities include:

- defining the detail of policies, objectives and strategies determined by State Council

- setting and evaluating directions, priorities and performance standards

- appointing the CEO and monitoring his or her performance

- liaising with MAV representatives from their regions.

The Rules also state that the MAV Board is responsible for conducting the affairs of MAV in accordance with the Rules.

While the PAA does not apply to the MAV Board it is an indicator of best practice. It requires relevant public sector Boards to have adequate procedures in place for:

- assessing the performance of individual directors

- dealing with poor performance by directors

- resolving disputes between directors.

MAV has no policy or procedures to assess the MAV Board's performance. The MAV Board is not subject to any external oversight of its performance more broadly.

MAV established a code of conduct for the MAV Board, last reviewed in November 2014, which commits members to behaviours that will 'enhance the leadership and governance of the organisation'. We assessed the MAV Management Board Code of Conduct against the Victorian Public Sector Commission's Directors Code of Conduct and Guidance Notes, and found it addresses most elements of better practice.

Common law

As a public body with a governing Board, MAV Board members are subject to a range of common law duties—to act honestly and in the best interests of MAV—and they can incur liability for decisions as a Board. In addition, Board members are ultimately responsible for major decisions around employment, finance, and audit and risk management which may expose MAV to liability. As one of MAV's income sources is public funds, good governance and accountability for the MAV Board's actions is paramount.

MAV audit committee

MAV established an audit committee in 2004 responsible for monitoring financial and risk controls, internal and external audit activities and organisational performance, and for advising the MAV Board on its governance framework. The MAV Board is ultimately responsible for MAV's governance framework.

The MA Act requires MAV to appoint a registered company auditor to undertake an audit of the financial report on its fidelity (crime) insurance scheme. This obligation was extended in 1961 to require all MAV accounts to be certified by the treasurer of MAV and the auditor. MAV's external audit activities have addressed these provisions in the MA Act. The MAV 2012–13 Annual Report states that in addition to the requirements of the MA Act and Rules, MAV must comply with relevant regulations and obligations applicable to statutory and public bodies. This includes provisions of its Australian Financial Services Licence, and compliance is audited annually by the MAV's independent, external auditor with findings reported to both the MAV Insurance Committee and the MAV Board. MAV's internal audit function has focused on the internal control environment and targeted risks associated with MAV's business performance.

Figure 2A

Internal audit coverage

Audit topics |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

MAV procurement |

✔ |

✔ |

|||

Risk assessment—MAV Insurance Committee |

✔ |

✔ |

|||

Grants |

✔ |

||||

Events and training |

✔ |

||||

Event credit card payments security |

✔ |

||||

Local government health plan |

✔ |

||||

Records management |

✔ |

||||

Procurement |

✔ |

||||

Business continuity planning |

✔ |

||||

Conflict of interest management |

✔ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from MAV.

The resources, coverage and scope of the internal audit activity have been limited in addressing the gaps in policy and process identified through this audit. There is scope for MAV to improve its coverage of risks and controls relating to the governance and management issues highlighted in this report, which as a public statutory entity are fundamental to MAV. This would also provide assurance that MAV is effectively and economically supporting councils.

Conflict of interest

Conflict of interest, whether actual, potential or perceived, can undermine good governance and the effective and economical provision of support to councils, through perceptions of unfair treatment and a lack of process transparency. In extreme cases it may constitute corruption or other criminal behaviour. Although the PAA does not apply to MAV, section 81(1)(f) provides useful guidance, which includes some basic requirements for managing conflicts of interest. Similar requirements are included in Managing Conflicts of Interest, a guide developed in consultation with the Victorian Ombudsman, VAGO and the Independent Broad-based Anti-Corruption Commission (IBAC).

In March 2014 MAV's internal audit recommended a review of the employee Code of Conduct policy, which they referenced as a draft copy dated September 2011. An MAV Staff Code of Conduct policy, marked as established in June 2014 refers to procedures for conflicts in relation to personal interests. There has been a single conflict of interest declaration by MAV staff since the code was developed. The code of conduct does not address potential conflicts of interest. MAV's internal audit of conflict of interest earlier in 2014 relied on the 2011 code of conduct and noted the absence of formal conflict of interest training for staff.

In the absence of a policy or procedure prior to the 2011 references in the code of conduct, it is not evident how MAV could have effectively managed any potential conflicts of interest in the past, including any related to activities designed to benefit councils. MAV advised it has a range of practices and controls in place to manage the risks of conflicts, fraud and corruption including:

- covering these issues in staff induction

- segregating duties such as accounting and payroll functions

- having internal controls for managers regarding financial approval limits

- controls around sponsorship for organisations tendering for services to MAV