Financial Systems Controls Report: Information Technology 2014–15

Overview

This report summarises the results of our audits of 45 public sector entities' IT controls performed in support of VAGO's 2014–15 financial audits. This report is in its second year and builds on the inaugural ICT controls report 2014–15 to provide additional insight and increase visibility of our IT audit findings. It also summarises reviews undertaken over two areas—identity & access management (IDAM) and software licensing practices.

Sixty-five key financial IT applications and their infrastructure were audited, with 462 associated audit findings used as the basis for this report’s analysis.

Most IT audit findings identified were rated medium and high risk, with one audit finding rated as an extreme risk. Along with the specific IT audit findings, this report draws out the following three clear emerging themes:

- management of controls at outsourced IT environments requires improvement

- use of IT systems that are no longer supported or at their end-of-life

- IT security controls need improvement.

Notwithstanding some deficiencies in IT controls, VAGO was able to rely on these controls for financial reporting purposes because other mitigating controls were identified and tested.

Financial Systems Controls Report: Information Technology 2014–15: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2015

PP No 98, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit the Financial Systems Controls Report: Information Technology 2014–15.

This report builds on VAGO's previous inaugural Information and Communications Technology Controls Report 2013–14 and aims to provide additional insight and increased visibility of IT related audit findings. The report is intended to provide decision-makers with relevant information to help them address IT audit findings and improve processes and controls.

For this audit, 45 entities with a financial year-end date of either 31 December 2014 or 30 June 2015 were selected for analysis. Sixty-five key financial IT applications and their infrastructure were audited, with 462 associated audit findings used as the basis for this report's analysis. Additionally, we have performed maturity assessments of selected entities' IT environments and examined two focus areas—identity and access management, and software licensing.

Most of our IT audit findings were rated medium and high risk, with one audit finding rated as an extreme risk. Along with the specific IT audit findings, this report also draws out three clear emerging themes.

The recommendations aim to assist public sector agencies address the identified IT audit findings and improve their IT control environments.

As part of our work this financial year, we have provided an update on the prior year high-level recommendations made as part of the Information and Communications Technology Controls Report 2013–14.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

7 October 2015

Auditor-General's comments

Each financial year VAGO undertakes a number of information technology (IT) audits to verify whether key financial systems are managed appropriately to support financial reporting process.

A total of 462 IT audit findings were found at the 45 entities selected for this report. Similar to last year, management at these entities continue to be slow to act on our findings, especially our high-risk findings. This demonstrates the need for more focused attention and oversight of IT issues by accountable officers and governance bodies, including audit committees. As a result, we intend to increase the level of accountability over the recommendations that are raised with management, especially at those entities that are not addressing our findings adequately or on a timely basis.

While there have been positive developments in the governance of outsourced IT arrangements, more effort is required by entities to enhance their visibility and accountability over outsourced activities and to assess the impact these activities have on entities' control environments. This year, inadequacies in assessing the reliability and quality of the audits conducted over their outsourced IT environments led to delays in finalising the financial reports of a number of entities, as well as additional audit costs and delays in finalising this report.

Alarmingly, each year VAGO is finding a large number of IT systems and software which are either no longer supported or fast approaching the end of support by the vendor. This poses IT security and operational risks to the entities IT environment, as well as unnecessary added costs.

Disappointingly, IT security-related audit findings continue to be raised and again account for the majority of our audit findings. It is also disappointing that our recommendation for a whole-of-government disaster recovery framework has not been addressed since it was first made in 2012–13.

This year we analysed two areas of focus—identity and access management, and software licensing. While software licensing was generally well controlled, controls to reduce the risk of inappropriate access to IT systems require significant improvement.

We have previously raised concerns regarding the Auditor-General's outdated mandate which restricts examination of public sector services undertaken by the private sector. These concerns continue and in the current year, VAGO was explicitly denied audit access by a private sector IT service provider. Consequently VAGO was unable to complete an audit of a public sector entity's IT environment and was forced to adopt a less efficient and more costly audit approach.

In the coming months VAGO will publish a better practice guide to enhance the IT control environment at public sector entities. I encourage all public sector entities to assess their IT control environment against this better practice guide.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

October 2015

|

|

Audit team Karen Phillips—Engagement Leader Ian Yaw—Team Leader Tonderai Nduru—Team member Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Paul Martin |

Audit Summary

This report summarises the results of our audits of selected public sector entities' information technology (IT) controls, performed in support of VAGO's 2014–15 financial audits. This report also summarises our reviews of two focus areas—identity and access management (IDAM), and software licensing practices.

IT controls are policies, procedures and activities put in place by an entity to assist and maintain the confidentiality, integrity and availability of its IT systems and data. IDAM consists of frameworks, policies and practices established to reduce the risk of inappropriate access to information systems and data. Software licensing controls are policies and practices implemented to manage the procurement and deployment of software, as well as ongoing compliance with vendor agreements.

This report is in its second year and builds on the inaugural Information and Communications Technology Controls Report 2013–14 to provide additional insight and to aggregate our IT audit findings. This report is also intended to provide decision-makers with relevant information to assist them to address IT audit findings, improve processes and controls, and to enhance accountability across the public sector.

For this audit, 45 entities with a financial year-end date of either 31 December 2014 or 30 June 2015 were selected for analysis. The audit findings relating to 65 IT applications relevant to financial reporting and associated IT infrastructure are analysed in this report.

The audit findings give a high-level view of IT general controls and weaknesses, and identify broad trends that may not be covered in reports we make to an entity's management during the course of a financial audit.

Conclusions

Our financial audits continue to identify a large number of IT control deficiencies, which have the potential to impact the confidentiality, integrity and availability of public sector financial data and IT systems.

Most of the IT audit findings identified were rated medium and high risk, with one rated as an extreme risk. Notably, the number of high-risk audit findings increased from 69 in 2013–14 to 134 in 2014–15. The key reason for this significant increase is related to IT security and the risks associated with using IT systems that are past or approaching their end-of-life. These were two of the three themes identified this year.

More focused attention and oversight by accountable officers and governance bodies is required to address our IT audit findings from previous years and to ensure sustainable process improvements are implemented to prevent future recurrence. Forty-one percent of our IT audit findings from previous years have not been addressed, many of which were rated high-risk.

Despite the identified IT control deficiencies, entity's control environments were reliable for financial reporting purposes, as satisfactory mitigations were in place, such as compensating management controls or alternative audit procedures.

For the 2014–15 financial year, there are three clear emerging themes. These are detailed in our Findings.

Findings

The three themes identified by our 2014–15 IT audits:

- The management of controls at outsourced IT environments requires attention—outsourced IT environments are in place for a number of in-scopeentities, with the state's IT shared services body, CenITex, being such an example. While there have been overall improvements during the year in how outsourced IT environments are managed, additional improvements are still required. There is a need to increase awareness of ownership and obligations relating to these outsourced environments, including assessing the reliability and quality of audits conducted over an entity's outsourced environment and assessing the impact of any control weaknesses on the entities' control environment. Contracts with service providers should not limit the ability of the entity to review the outsource providers' controls environment.

- The use of IT systems that are at their end-of-lifeneeds to be addressed—some of the software used to support financial systems are nearing their end‑of‑support dates or are past the support dates, and may result in increased risks and maintenance costs to in-scope entities.

- IT security controls need improvement—IT security control weaknesses account for 68 per cent of all IT audit findings. There is poor management of IT security, particularly relating to user access and alignment with Victorian Government IT security standards.

A total of 462 IT audit findings were reported. Of the 134 high-risk IT audit findings, 91 per cent relate to:

- managing access to IT applications and data

- authenticating users to IT systems, such as password controls

- assurance obtained by entities over IT general controls performed by external organisations

- entities using IT systems, which are no longer, or soon not to be, supported by vendors.

Recommendations

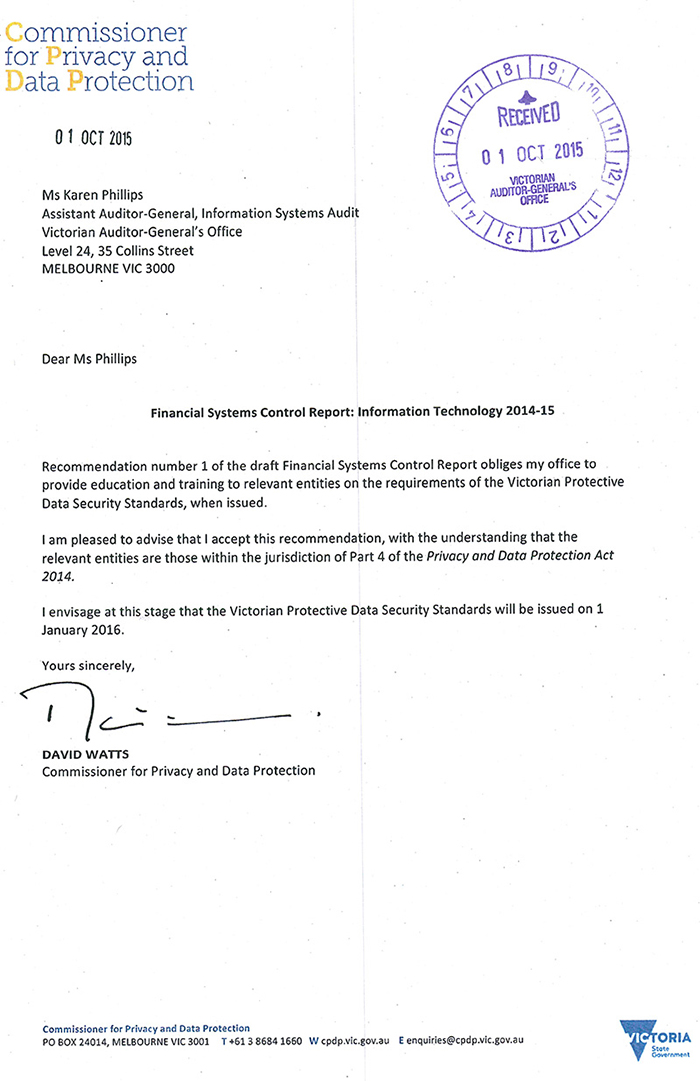

That the Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection:

- provides education and training to relevant entities on the requirements of the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards—once issued.

That the Department of Premier & Cabinet:

- monitors and reports the status of information technology obsolescence risks at departments and public sector agencies

- monitors and reports the status of the implementation of disaster recovery frameworks and plans by shared services boards. These frameworks and plans should:

- prioritise information technology systems recovery in the event of a disaster impacting a number of departmentsand agencies

- cover financial and non-financial systems.

That public sector entities' governing bodies and management:

- enhance management's understanding of their Financial Management Act 1994 and Standing Directions obligations, and ensure:

- assurance reports received for outsourced information technology environments are reliable and fit-for-purpose

- exceptions raised in assurance reports are assessed for the impact they may have on the entity's control environment

- manage the continuity of vendor support for systems approaching end-of-life, including its upgrade or migration to fully supported solutions. Where possible, entities should work collaboratively to address information technology obsolescence risk across the public sector

- implement appropriate governance and monitoring mechanisms to ensure:

- information technology audit findings are addressed by management

- sustainable process improvements, to prevent future recurrence

- align information technology control frameworks to relevant Victorian Government information technology security standards.

That public sector entities' governing bodies and management:

- ensure that, where relevant, shared service providers implement disaster recovery frameworks which prioritise information technology systems recovery in the event of a disaster impacting a number of departments and agencies. The framework and plans should cover financial and non-financial systems

- enhance identity and access management, and software licensing policies and procedures by addressing control weaknesses reported in management letters

- implement processes to periodically monitor the effectiveness of identity and access management, and software licensing processes and controls.

Submissions and comments received

We have engaged with the Deputy Secretary, Governance Policy and Coordination within the Department of Premier & Cabinet, the Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection, the Deputy Secretaries of the portfolio departments and the Chief Information Officer Council throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we provided a copy of this report to the audited agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. The full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix C.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

When planning a financial audit, VAGO seeks to understand and evaluate an entity's information technology (IT) environment and any related risks to the reliability of financial reporting.

This report summarises the results of this work on selected public sector entities' IT general controls as part of the 2014–15 financial audits. This is the second report of its kind and aims to provide extra insight into VAGO's IT audit findings, and identify wider trends that may not be covered in reports to an entity's management.

The report also summarises the outcomes of reviews performed over the focus areas of identity and access management, and software licensing.

1.2 Internal control framework

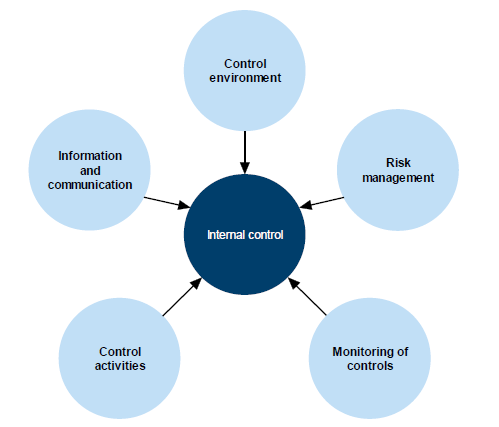

An entity's governing body and its accountable officer are responsible for developing and maintaining an internal control framework. Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures which help an entity to reliably and cost effectively meet its objectives, as well as minimise risk and fraud.

The components of an internal control framework are shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Components of an internal control framework

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In Figure 1A:

- Control environment—provides the fundamental discipline and structure for controls and includes governance and management functions as well as the attitudes, awareness and actions of those charged with governance and management of an entity.

- Risk management—involves identifying, analysing, mitigating and controlling risks.

- Monitoring of controls—involves observing the internal controls in practice and assessing their effectiveness.

- Control activities—policies, procedures and practices issued by management to help meet an entity's objectives.

- Information and communication—involves communicating control responsibilities throughout the entity and providing information in a form and time frame that allows staff to discharge their responsibility.

An annual financial audit enables the Auditor-General to form an opinion on an entity's financial report. An integral part of this process, as well as a requirement of Australian Auditing Standard ASA 315 Identifying and Assessing the Risk of Material Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and its Environment, is to evaluate the strengths of an entity's internal control framework and governance processes as they relate to its financial reporting.

While the auditor considers the internal controls relevant to financial reporting, there is no requirement for the auditor to provide an opinion on their effectiveness. Consequently, an unmodified audit opinion on the financial report is not an opinion on the adequacy or otherwise of the entity's internal control environment as any control inadequacies are mitigated by additional audit work. The ultimate responsibility for the effective operation of the internal control at all times remains with the entity's management.

Significant internal control deficiencies identified during an audit are communicated to the entity's governing body and management so that they may be rectified in the management letter. Such deficiencies or weaknesses in controls will usually not result in a qualified audit opinion as often an entity will have compensating controls in place that aid in mitigating the risk of a material error or misstatement in the financial report, or the auditor may be able to obtain evidence through performing substantive procedures.

However, for entities that use highly automated IT systems to initiate and process financial transactions, the IT system is the sole repository of the record of transactions. A significant internal control weakness in the IT system may result in a qualification if it prevents the auditor from obtaining sufficient evidence about the accuracy, completeness and reliability of the financial information being reported.

1.2.1 The importance of IT systems and IT general controls

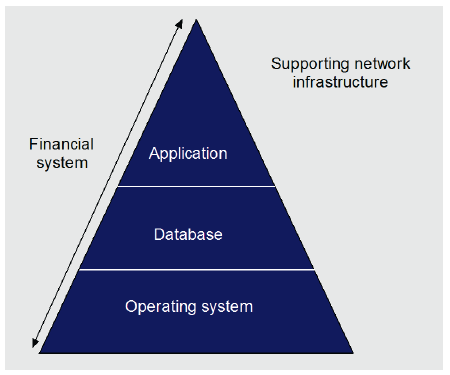

An IT system is a collection of computer hardware and programs that work together to support business or operational processes. IT systems are generally made up of three components:

- Operating system—core programs that run on the IT hardwarethat enable other programs to work. Examples of operating systems include Microsoft Windows, Unix and IBM OS/400.

- Databases—programs that organise and store data. Examples of database software include an Oracle database and Microsoft SQL Server.

- Applications—programs that deliver operational or business requirements. There are various types of IT applications, which are described in Section 1.5.

These components are supported by an entity's network infrastructure. A typical VAGO scope for an IT general controls audit covers all three IT system components for in‑scope key financial systems. This is shown in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Typical scope for an IT general controls audit

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

IT general controls are policies, procedures and activities put in place by an entity to assist and ensure the confidentiality, integrity and availability of its IT systems and data.

Auditing Standard ASA 315 Identifying and Assessing the Risks of Material Misstatement through Understanding the Entity and Its Environment states that IT benefits internal control by enabling an entity to:

- consistently apply predefined business rules and perform complex calculations in processing large volumes of transactions or data

- enhance the timeliness, availability, and accuracy of information

- reduce the risk that controls will be circumvented

- enhance the ability to achieve effective segregation of duties by implementing security controls in applications, databases, and operating systems.

An example of an IT general control is whether access requests to IT systems are properly reviewed and authorised by management. The objective of this control is to ensure only authorised users have access to the entities' IT systems.

Ineffective IT general controls may have an impact on the reliability and integrity of the system's underlying financial data and programs and may impact the ability of VAGO to rely on underlying business and process controls.

Auditing Standard ASA 265 Communicating Deficiencies in Internal Control to Those Charged with Governance and Management requires the auditor to:

- communicate, in writing, all significant deficiencies in internal control and their potential effects to those charged with governance, and where appropriate, management

- communicate to management other identified deficiencies in internal control that the auditor considers to be of sufficient importance to merit management's attention.

Weaknesses identified by VAGO during an IT audit are brought to the attention of the entity's accountable officer and chair of the governing body, as well as the chief financial officer, chief information officer and audit committee, by way of a management letter. We also seek management's comments on remediation plans and time frames for addressing any audit observations or recommendations.

1.3 Recent key changes to the sector

Recent changes within the public sector have impacted the scope of our IT audits.

1.3.1 Machinery-of-government changes

Following the Victorian state election on 29 November 2014 and the formation of a new state government, machinery-of-government changes were made in January 2015 to restructure key departments and agencies.

From an IT perspective, most notable was the transition of responsibilities for whole‑of‑Victorian‑Government (WoVG) IT strategy, policy, and operations from the former Department of State Development, Business & Innovation (DSDBI) to the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC).

There were several other impacts:

- The governance and leadership roles of Minister for Technology and Chief Technology Advocate were abolished.

- Following the transition of the whole-of-public-sector IT portfolio to DPC, the Digital Government Branch was renamed the Enterprise Solutions Branch and its coverage includes:

- WoVG Projects Reporting Assurance—coordinates briefs, audit responses, correspondence and other content for the branch.

- Business Systems, Policy and Standards—defines standards for the procurement of new business systems, plus WoVG policies for IT and business systems. Also responsible for the development of the WoVG IT strategy.

- Shared Services Governance and Assurance—develops the governance framework for shared services operations and provides progress reports on the implementation of the shared services agenda.

VAGO consulted with DPC as the lead agency for this report.

1.3.2 CenITex

CenITex is an IT shared services agency, set up as a state body by the Victorian Government in July 2008 to centralise IT services for government agencies.

As a key service provider of IT services to a number of government departments and agencies, a number of this audit's findings are associated with CenITex, and the IT infrastructure and processes that it manages.

In recent years, there have been uncertainties over CenITex's future with a number of projects initiated to evaluate potential options, including outsourcing to the private sector.

On 30 June 2015, the government announced that it would implement a new approach to the establishment and management of shared business support services. The announcement also clarified that CenITex would continue to provide IT services that are specific to government and that the other services provided by CenITex, that are readily available in the market, would be market tested over the next year.

It should be noted that work performed as part of our financial audits does not assess the effectiveness or efficiency of CenITex.

1.3.3 Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection

The Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014 came into effect on 17 September 2014. This legislation significantly changes the regulatory landscape for privacy and data protection in the Victorian public sector.

The Act sets out three main areas of focus:

- Part 1: Information Privacy

- Part 2: Data Protection

- Part 3: LawEnforcement Data.

In July 2015, the draft Victorian Protective Data Security Standards were released for stakeholders comments. Given the significant role of the Commissioner, VAGO will monitor standards and guidelines issued by the Commissioner and the impact on IT control requirements across government.

1.4 Departments and agencies in scope

This report summarises the results of the audits of IT general controls conducted as part of the annual financial audits of 45 selected entities, with a financial year-end date of either 31 December 2014 or 30 June 2015—the audited agencies are listed in Appendix B.

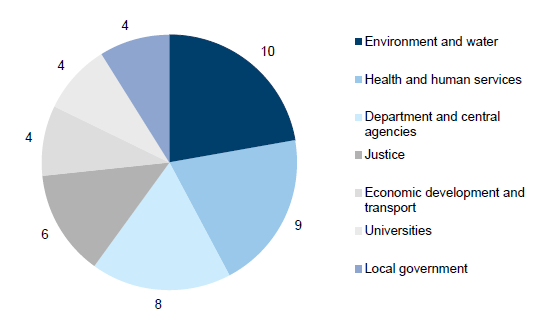

The selected entities are summarised by sector in Figure 1C.

Figure 1C

Selected in-scope entities by sector

Note: For the purposes of this report, departments are grouped with central agencies.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The most represented sectors are:

- environment and water—10 entities

- health and human services—nine entities

- department and central agencies—eight entities

- justice—six entities.

This report will largely focus on these four sectors, which represent about 74 per cent of our in-scope entities. The characteristics of the entities within these sectors are found in Part 3.5.

1.5 IT systems in scope

Within the 45 selected entities, we audited IT general controls relating to 65 IT applications and associated IT infrastructure. These applications are a combination of financial and operational applications that support key financial processes.

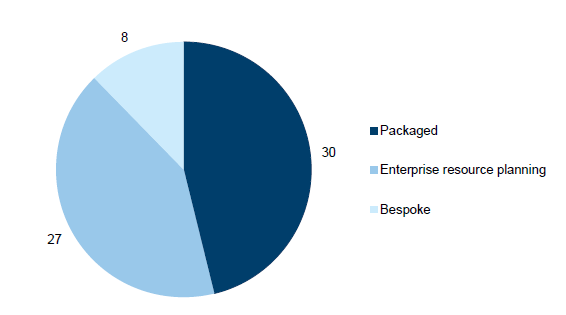

The types of IT applications in scope are summarised in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

In-scope IT applications by type

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

A description of the IT applications follows:

- Bespoke software—includes custom developed applications that are purpose built with a specific need in mind, e.g. the myki system used by Public Transport Victoria.

- Enterprise Resource Planning—complex applications that deliver a wide range of business processes across the organisation. For example, the Oracle E‑business suite is used to support financial reporting in a number of departments and agencies.

- Packaged applications—also known as commercial 'off-the-shelf' packages, are usually designed to support a specific process. This software will typically function without extensive customisation, although there have been some instances of customisation. For example, the Chris21 application is used to support payroll processes in a number of entities.

1.6 Reliance on the work of others

To reduce duplication of audit effort and to maximise audit effectiveness and efficiency, as part of VAGO's audit methodology, the audit team considered the work performed by other parties where a similar scope of work was performed during the audit period.

From an IT perspective, reliance on work performed by others can be grouped into two categories:

- Internal audit—an effective internal audit function will often allow a modification in the nature and timing, and a reduction in the extent of procedures performed by VAGO, but cannot entirely eliminate the need for independent testing. When we intend to rely on specific internal audit work, we evaluate and test that work to confirm its adequacy for our purposes.

- Service assurance reports—these reports typically relate to shared service providers for IT or data processing services and external investment managers. CenITex is an example of such an arrangement. Where such organisations are used to support controls over key processes, we seek to obtain a service assurance report that describes the control environment. These reports provide independent assurance to management that an effective internal control environment had been maintained, which allows them to meet the requirements under the provisions of the Financial Management Act1994pursuant to the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance.

Where the work of others can be used to support our audit testing of IT processes and controls, VAGO assesses the scope and findings for impact on our financial audit approach. This would, in turn, guide any additional testing that may be required.

For the purposes of this report, where VAGO has relied on the work of others in our financial audits, relevant findings identified by the service auditor have been consolidated with our work.

1.7 Audit conduct

The audits of the 45 entities were undertaken in accordance with Australian Auditing Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of preparing and printing this report was $215 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the top three themes or trends noted during the course of the IT audits

- Part 3 provides a summary of the IT audit findings noted as part of the 2014–15 audits and an IT general controls maturity assessment conducted by VAGO

- Part 4 examines the two focus areas—identity and access management, and software licensing.

2 Themes from IT audits

At a glance

Background

Key information technology (IT) audit themes are drawn from testing performed as part of each entity's annual financial audit, as well as discussions with management and analysis of our IT audit findings. These themes are prepared to provide insight and actionable recommendations for public sector entities.

Conclusion

For the 2014–15 financial year, we identified three clear emerging themes from IT audits, and have made a number of recommendations to address them.

Findings

- The management and oversight of IT controls by external service providers requires improvement.

- Entities are continuing to use IT applications and systems that are approaching the end of the vendor's support cycle.

- Alarge number of our IT audit findings relate to IT security control weaknesses.

Recommendations

- That the Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection provides education and training to relevant entities on the requirements of the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards—once issued.

- That Department of Premier & Cabinet monitors and reports the status of information technology obsolescence risks at departments and public sector agencies.

- That public sector entities' governing bodies and management:

- enhance management's understanding of their Financial Management Act 1994and Standing Directionsobligations

- manage the continuity of vendor support for systems approaching end-of-life

- implement appropriate governance and monitoring mechanisms to ensure IT audit findings are addressed by management to prevent futurerecurrence

- align IT control frameworks to relevant Victorian Government IT security standards.

2.1 Introduction

This Part discusses:

- the top threethemes noted during the information technology (IT) audits conducted for the 2014–15 financial year

- the root cause analysis and insights into the IT audit themes

- the strategic implications and recommendations for possible future action plans.

2.2 Top three themes noted in 2014–15

Based on our analysis of the IT audit findings noted during 2014–15, there were three top themes:

- The management ofcontrols at outsourced IT environmentsrequires attention—the management and oversight of IT controls undertaken by external service providers requires improved governance and oversight.

- The use of IT systems that are at their end-of-life needs to be addressed—entities are continuing to use IT applications and systems that are approaching the end of the vendor's support cycle.

- IT security controls need improvement—a large number of our IT audit findings relate to IT security control weaknesses.

2.2.1 Management of controls at outsourced IT environments

Our observations

When a public sector entity relies on an outsourced provider or 'cloud' service providers to operate and maintain their IT environment, management needs to obtain assurance that the controls implemented and managed by the outsourced provider are operating effectively. Typically, cloud service providers provide their services to the organisation—in the form of software, infrastructure and platform—over the Internet. By using an outsourced IT arrangement, the entity's management does not forego its duty to ensure that controls are adequate and that the entity's data and information is protected.

The effectiveness of controls at these outsourced IT environments is typically reported to a public sector entity through a service assurance report such as ASAE 3402 Assurance Reports on Controls at a Service Organisation or AUS 810 Special Purpose Reports on the Effectiveness of Control Procedures. Public sector entities need to request that the outsourced IT provider engage an auditor to perform this work and report back to them. This enables entities to certify their annual financial report and complete the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance certification.

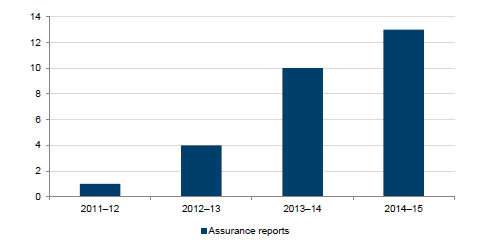

Consistent with the inaugural Information and Communication's Technology Controls Report 2013–14 (ICT Controls Report 2013–14), there continues to be a noticeable upward trend in the number of service assurance reports being obtained by public sector entities. These reports are relied upon by the public sector entity for attesting to the overall strength of the external providers controls environment and are relied upon by VAGO for our financial audits.

In 2014–15, 13 assurance reports for the IT general controls at outsourced IT environments were provided to VAGO. This compares to 10 in 2013–14, four in 2012–13 and one in 2011–12. This trend is shown in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Number of assurance reports relied upon by VAGO for financial audits

Note: Where multiple service assurance reports are prepared for a shared

service IT provider such as CenITex, this is counted as one report.

Source: Victorian

Auditor-General's Office.

For 2014–15, VAGO actively discussed the control weaknesses identified in these reports with management and audit committees. As part of their obligations of maintaining a sound control environment, VAGO has encouraged management to review these assurance reports with greater rigour and to acquit and take ownership over the weaknesses.

As part of this and as committed to in last year's ICT Controls Report 2013–14, VAGO has commenced reporting on relevant weaknesses arising from assurance reports with the aim of:

- improving overall accountability

- driving the tracking of these weaknesses by management and audit committees

- enhancing remediation of the weaknesses.

Insights and implications

Since first highlighting this theme in the ICT Controls Report 2013–14, there have been some notable changes.

Policy guidance

The Financial Management Act 1994 and the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance require an entity's management to maintain an effective internal controls environment.

In our ICT Controls Report 2013–14, we recommended that further policy guidance was required at the whole-of-government level, as a number of agencies did not currently obtain any form of assurance over outsourced controls. During 2014–15, VAGO consulted with the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) which led to the publishing of the Key advice update No 1, 2015 - Managing outsourced financial services to provide further guidance to entities utilising such arrangements. Guidance specific to managing outsourced IT arrangements is not available.

Improved management accountability

As described in our ICT Controls Report 2013–14, there was a perception among some public sector entities that in an outsourcing arrangement the risks associated with the control environment are also transferred, which is not the case. In our interactions with the management of those entities this year, there has been a growing awareness and acceptance of management's responsibilities. This has directly resulted in an increase in the number of service assurance reports received, or other instruments used to obtain assurance.

Worryingly, there remain pockets of limited awareness and acceptance, including high‑risk entities, of the risks and responsibilities associated with outsourced arrangements. As a result we will continue to encourage a culture of ownership and responsibility across the public sector.

While there has been a marked improvement in available policy guidance and management accountability over service organisation assurance, these areas still require improvement.

Access to review controls at private sector entities

The current Audit Act 1994 limits the Auditor-General's ability to directly follow up on the activities and controls of private sector entities, which are increasingly delivering cloud services and outsourced arrangements to the public sector. The Audit Act's limitations have been a recurring concern, and during 2014–15 VAGO was explicitly denied audit access by a private sector service provider. Figure 2B highlights why there is an urgent need to amend the Audit Act 1994.

Figure 2B

Case study: Audit

Act 1994 limitations

During the 2014–15 audit of a public sector entity, the entity's payroll process was evaluated to be material to the financial report. The entity's payroll process utilised a cloud-based application ('software-as-a-service'). The cloud-based application vendor had not provided the public sector entity with an assurance report and there was no 'right of audit' embedded within the contract between the entity and the vendor. Management similarly did not have any visibility over most of the controls implemented by the vendor. While the vendor was willing to provide a portion of the information requested to enable VAGO to undertake the audit, key audit evidence, such users access listings to the entity's data, was deemed by the vendor to be commercial-in-confidence, or too sensitive to be released. Because of the current mandate limitation, we were unable to access the information required to assess the operating efficiency of the controls that prevent and detect payroll errors from occurring. As a result, VAGO was unable to complete an audit of the IT environment and a less efficient approach was undertaken, resulting in unnecessary higher audit costs. This issue was raised in our management letter as management does not have visibility over, and has not received assurance over, controls operating in this outsourced IT environment as required by the Financial Management Act 1994. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Entities review of the reliability and results of assurance reports

To ensure entities are meeting their obligations under the Financial Management Act 1994, an increased emphasis is needed on assessing the reliability of assurance reports and understanding the impact the issues raised may have on their control environment. Figure 2C details a case study where greater rigour over an assurance report was required during 2014–15.

Figure 2C

Case study: CenITex Service Assurance Program

CenITex is a key provider of IT services to a number of in-scope departments and agencies. In addition to the operational activities that it delivers, CenITex also coordinates and manages a service assurance program, which aims to deliver assurance reports prepared in accordance with auditing or assurance standards, dependent on the department or agencies requirements. During 2014–15 VAGO raised concerns about the quality and reliability of these assurance reports. As a result, we did not place full reliance on these assurance reports and for the purposes of our 2014–15 financial audits, we conducted independent audit testing. This led to delays in finalising the financial reports of the affected departments and agencies, as well as additional audit costs and a delay in finalising this report. Concerns over the reliability of the assurance reports also led to concerns about whether departments and agencies had sufficiently met their obligations under the Financial Management Act 1994. VAGO requested that management at the departments and agencies undertake additional procedures to assess the overall operation of IT controls, including the reliability of the assurance reports, their findings and any control areas not assessed by the CenITex auditor. This finding was raised in our management letters to the relevant departments and agencies as these entities have not implemented a sustainable process to ensure that management assesses the reliability of assurance reports and understands the impact of the issues raised in these reports. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Remediation of service organisation control weaknesses

While there has been an increase in public sector entities obtaining service assurance reports, there has been limited monitoring undertaken to ensure that the service organisations are remediating the controls weaknesses identified in a timely manner. As a result, commencing in 2014–15, we are summarising the relevant audit findings in our management letters and will regularly check that activities to address these control weaknesses are monitored by management.

We identified one instance where a public sector entity was able to hold their service organisation to account and influence it to strengthen certain aspects of its IT control environment—access controls to IT systems and financial data by the vendor's staff have been strengthened.

2.2.2 Use of IT systems that are end-of-life

Our observations

It is essential that public sector entities ensure that their IT systems have appropriate vendor support. 'End-of-life' generally refers to when a vendor intends to stop marketing or supporting a piece of IT software or an application. For example, Microsoft Windows XP's extended support ended in April 2014. Vendors typically indicate to their customers in advance when such support arrangements will cease, to enable a smooth transition to current software prior to a programs end-of-life.

Since 2011–12, as part of our audits, VAGO has reported to in-scope entities which of their financial systems are either approaching end-of-life or past their end-of-life. We inform the entities of the risks posed by continuing to utilise such applications, including new security weaknesses not being fixed by the vendor. Due to the length of time required to implement large scale IT systems, VAGO's approach has always been to flag such issues early and to encourage awareness and proactive remediation activities.

Of particular concern, in 2014–15, was the limited progress by entities in upgrading end-of-life systems. We found audit findings relating to IT systems approaching end‑of‑life or past their end-of-life at 53 per cent of our in-scope entities. The majority of these 34 end-of-life audit findings were related to key financial systems, including Oracle Financials. Findings also related to software on users' desktops computers, such as Windows XP.

Insights and implications

Our analysis of these findings identified the following issues.

Whole-of-Victorian-Government enterprise resource planning re‑implementation

Following the November 2014 change of government and subsequent January 2015 machinery-of-government changes, a project to review and implement a whole‑of‑Victorian-Government enterprise resource planning (ERP) system was suspended. As a result, the financial systems for many in-scope entities are either approaching end-of-life or are past their end-of-life. Given the current situation and the time required to implement an ERP system, this issue is expected to remain unresolved for some time.

Cost of maintaining obsolete software

As an interim measure, a number of public sector entities have entered into customised contractual arrangements with vendors for the support of obsolete IT software. These arrangements typically come at a significant cost and some vendors increase the cost over time as the use of the program declines globally. As an example, a one-year custom support arrangement for Microsoft Windows XP was renewed by a department in April 2015 at a cost of $2.37 million.

2.2.3 IT security controls need improvement

Our observations

Our IT security findings relate to the following IT general controls categories:

- user access management

- authentication controls

- audit logging and monitoring of IT environment

- patch management

- other IT general controls, including malware protection, penetration testing, physical and environment controls, security and architecture and end-of-life.

IT security issues account for 68 per cent of our 2014–15 audit findings. This is a nominal increase of 1 per cent on the prior year and once again highlights the need for a continued focus on remediating IT security weaknesses.

Most notably, in 2014–15 we have reported an extreme-risk rated audit finding relating to authentication and password controls at one entity. This is detailed in Figure 2D.

Insights and implications

User access management

As described in Part 3 of this report, user access management is the most prevalent issue, accounting for nearly 30 per cent of all our findings. Nearly all in-scope entities have user access management audit findings, which is consistent with the findings of our ICT Controls Report 2013–14.

Public sector entities need to continuously improve the process of managing system access. There are three root cause of user access management control weaknesses:

- Poor understanding of access provided—it is common for VAGO to find user accounts for terminated staff not being disabled or removed. While this can be categorised as an oversight, it is ultimately due to a poor understanding or poor documentation of the access provided to the user, or is due to poor process design. 'Single sign-on' systems can help reduce such issues, and are in place at many in-scope entities, but our findings indicate that this does not solve the problem. A process of systematically recording account ownership and all the system accessible to each staff member is key to ensuring that they are subsequently removed when no longer required.

- The 'human factor' and manual intervention—human oversights are likely the reason why access remained on systems after a staff member resigns or no longer requires that access. Such oversights are often related to appropriate parties not being notified when a user changes roles. While it is not possible to completely eliminate the 'human factor', how user access is managed can be heavily influenced by well-defined policies, procedures and processes, by an organisation's culture and tone from the top, and by monitoring controls.

- Inadequate periodic reviews—the intent of periodic reviews is to validate user access to systems on an ongoing basis and ensure that this is aligned with business needs. Where not aligned, the access should be modified accordingly. This often works as an independent control in combination with existing process controls. More often than not, periodic reviews are conducted by management but are not sufficiently effective to eliminate instances of excessive access provided. In some instances, periodic reviews only focused on certain elements of the IT infrastructure, resulting in control limitations.

Victorian Government IT security standards

In November 2013, a number of IT security standards were published to take effect from 1 January 2014. Some of these standards relate to identity and access management (IDAM), providing specific guidance on password controls and bringing the overall Victorian IT control framework into alignment with better practices and applicable Commonwealth standards such as the Australian Government Information Security Manual.

While compliance with the Victorian Government's Identity and Access Management (IDAM) Standard 03 – Strength of Authentication Mechanism v1.0 is mandatory for all departments and 11 audited agencies, our IT audits found a large number of issues related to password controls. Typical audit findings include:

- entities which have not updated their password policies and procedures to reflect the standard's requirements

- password settings implemented on in-scope systems did not comply with the standards.

This is disappointing given that the Victorian Government IT security standards have been in effect for the full financial year, and agencies have had time to develop an implementation plan.

Through our interaction with management, we believe that there is a general lack of awareness of the Victorian Government IT security standards. Going forward and recognising that there may be changes introduced by the Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection, VAGO intends to further assess entities compliance with the Victorian Government IT security standards.

At one of our audited entities, we found an extreme risk surrounding authentication controls, which is not consistent with Victorian Government IT security standards. This example is detailed in Figure 2D.

Figure 2D

Case study: Extreme risk surrounding authentication controls

A public sector entity was found to have password management policies and configurations that are not consistent with Victorian Government IT security standards. Ordinarily, such an audit finding would be rated as high risk, however, this case was rated as an extreme risk based on the sensitive and confidential nature of the data that is stored by the entity. Our review identified that the entity's password management policies are either silent on a number of key password requirements, or the requirements were not strong enough. Audit testing identified numerous instances where the system password configurations were neither aligned with the Victorian Government IT security standards, nor aligned with approved internal standards. We have highlighted these audit findings for the attention of IT senior management and the audit committee, with responses from both parties being positive and encouraging. Given its risk rating, management expedited the implementation of our audit recommendations. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Recommendations

- That the Commissioner for Privacy and Data Protection provides education and training to relevant entities on the requirements of the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards—once issued.

- That the Department of Premier & Cabinet monitors and reports the status of information technology obsolescence risks at departments and public sector agencies.

That public sector entities' governing bodies and management:

- enhance management's understanding of their Financial Management Act 1994 and Standing Directions obligations, and ensure:

- assurance reports received for outsourced information technologyenvironments are reliable and fit-for-purpose

- exceptions raised in assurance reports are assessed for the impact they may have on the entity's control environment.

That public sector entities' governing bodies and management:

- manage the continuity of vendor support for systems approaching end-of-life, including its upgrade or migration to fully supported solutions. Where possible, entitles should work collaboratively to address information technology obsolescence risk across the public sector

- implement appropriate governance and monitoring mechanisms to ensure:

- information technology audit findings are addressed by management

- sustainable process improvements, to prevent future recurrence

3 Results of IT audits

At a glance

Background

For each of the 45 entities selected for this report, we prepared management letters highlighting any control weaknesses identified by our information technology (IT) audits. For this report, these management letters were analysed to identify the overarching themes and key messages that may have a broader impact.

Conclusion

Our financial audits continue to identify a large number of IT control deficiencies. Most of the IT audit findings identified are rated medium and high risk. The number of high‑risk findings has increased from 69 in 2013–14, to 134 in 2014–15. One audit finding was rated an extreme risk, to reflect its importance to the entities control environment.

Despite the identified IT controls deficiencies, entities' control environments were reliable for financial reporting purposes, as satisfactory mitigations were in place, such as compensating management controls or alternative audit procedures.

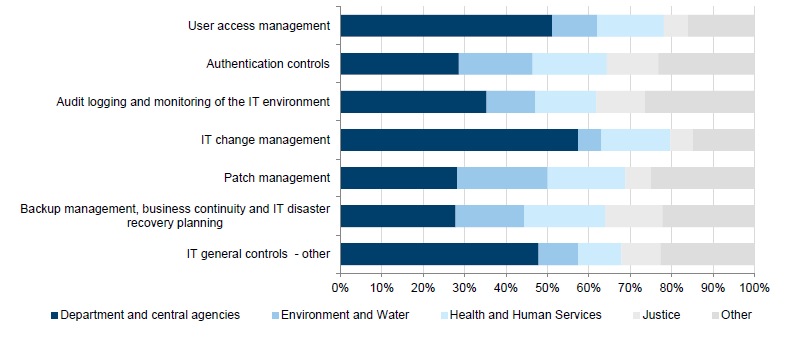

Findings

- User access management and authentication controls continue to be frequently reported high-risk findings,highlighting the need for improvement in this area.

- Other prominent high-risk findings related to:

- patch management

- backup management, business continuity and IT disaster recovery planning

- other IT general controls, namely, third-party assurance and high‑risk systems either past, or approaching their end-of-life.

Recommendations

- That public sector entities' governing bodies and management ensure that, where relevant, shared service providers implement disaster recovery frameworks which prioritise IT systems recovery in the event of a disaster impacting a number of departments and agencies.

- That the Department of Premier & Cabinet monitors and reports the status of the implementation of disaster recovery frameworks and plans by shared services boards.

3.1 Introduction

This Part provides a high-level analysis of our 2014–15 information technology (IT) general controls audits.

The audit findings were analysed according to:

- ratings and categorisation—extreme, high, medium and low, as explained in Part 3.3, with further detail in Appendix A

- IT general controls category—for example, user access management and authentication controls

- sector—the sector analysis within this report will largely focus on four sectors; environment and water, departments and central agencies, health and human services and justice.

These audit findings are also used for our maturity assessment of the IT controls environment at the in-scope entities, as reported in Section 3.6.

3.2 2014–15 IT audit results

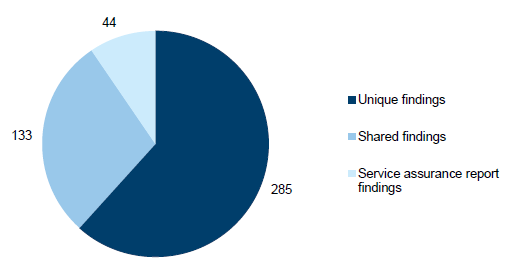

For the 45 selected entities for the 2014–15 financial year, 462 new and previously identified IT audit findings were reported. This represents an increase of 27 per cent compared with the prior year, however there was a 15 per cent increase of in‑scope entities.

As shown in Figure 3A, of these audit findings:

- 133 were shared findings as a result of IT environments being shared across entities

- 44 were identified from outsourced IT service assurance reports, which are discussed as a theme in Part 2 of this report.

Figure 3A

Total new and prior-year audit findings not addressed

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

3.3 IT audit findings ratings and categorisation

3.3.1 Introduction

All VAGO IT audit findings are assigned a risk rating. The rating reflects our assessment of both the likelihood and consequence of each identified issue and assists management to prioritise remedial action.

Audit findings for 2014–15 are rated extreme, high, medium and low risk, further details are found in Appendix A. Through the reporting process, ratings for audit finding are subject to review by management of the in-scope entities.

For the purposes of the Financial Systems Controls Report 2014–15, audit findings are also categorised into the following categories for analysis:

- user access management

- authentication controls

- audit logging and monitoring of the IT environment

- IT change management

- patch management

- backup management, business continuity and IT disaster recovery planning

- other IT general controls.

- Other IT general controls are a collection of audit findings that do not necessarily correspond with the above groups. Controls in this category are detailed in Section 3.4.7 of this report.

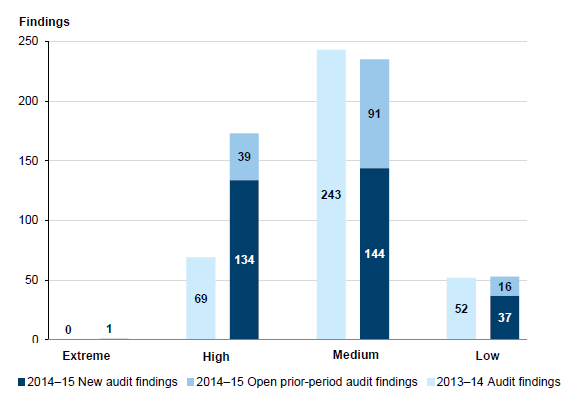

Analysis of audit findings by risk rating

Figure 3B show an analysis of findings by risk rating and whether the findings were new or prior-year findings.

Figure 3B

Findings by risk rating—new and prior year audit findings not addressed

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

As Figure 3B shows:

- consistent with prior years, most audit findings were rated as medium risk.

- one extreme-risk rated audit finding was identified during 2014–15, in contrast to 2013–14 when no extreme-risk rated audit findings were raised

- despite the 27 per cent increase in the total number of audit findings as compared with prior years, the total number of medium- and low-risk findings have remained relatively stable with the biggest increase being high-risk audit findings, from 69 in 2013–14 to 134 in 2014–15. This is due to an increased number of audit findings in areas such as user access management, IT change management and systems approaching their end-of-life, which are elaborated on, later in this Part.

Analysis of audit findings by category

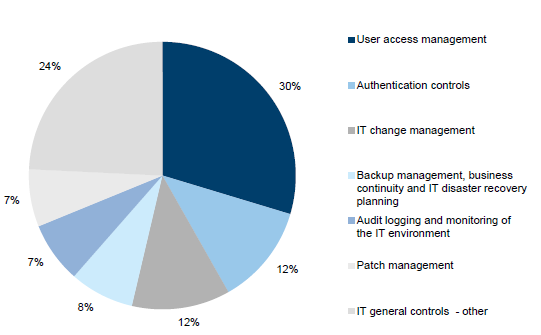

Figure 3C highlights the percentage of IT audit findings in each IT general controls category.

Figure 3C

Findings by IT general controls category

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In 2014–15, an analysis of audit findings by category noted that:

- consistent with the prior year, our findings mostly related to theuser access managementand authentication controls categories

- while findings related to IT change management only increased 4 per cent against all IT audit findings, this category registered a marked increase from 28 findings in 2013–14 to 54 in 2014–15

- there is a marginal increase in audit findings categorised under the 'other' category (refer to Section 3.4.7), which is attributable to slight variations in VAGO's overall audit approach:

- there was an increased coverage of our areas of focus; identity and access management, and software licensing, as discussed in Part 4 of this report

- there was a reduced focus on controls related to penetration testing, physical and environmental controls.

The user access management, authentication controls and other categories account for 66 per cent of all reported findings in 2014–15.

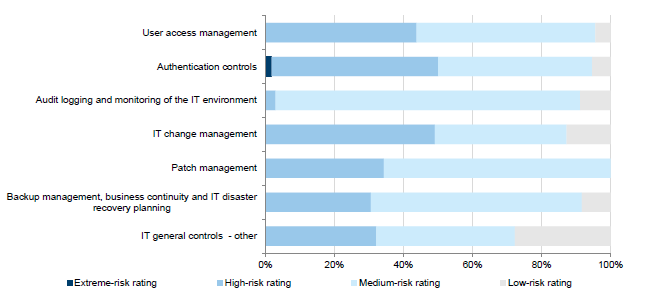

Analysis of audit findings by category and risk rating

Figure 3D shows the distribution of risk ratings within each category.

Figure 3D

Audit findings by risk ratings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In 2014–15:

- an extreme-risk rated audit finding was identified in the authentication controlscategory, but no other categories had an extreme-risk audit finding

- the categories of authentication controls, user access management, IT change managementand other are more likely to have high-risk audit findings. Findings relating to these areas include:

- password controls do not comply with leading practices or government IT standards

- excessive numbers of users having administrator access to systems

- financial systems in use that are either past or approaching their end-of-life and may not be supported by the vendor.

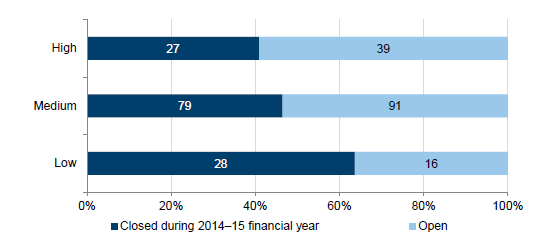

3.3.2 Remediation of prior-period IT audit findings

For each of our audit findings the entity's management is required to commit to a date to implement remedial actions. As part of our IT general controls audit, VAGO tracks the audit findings raised and the status of management's remediation.

In 2013–14 VAGO raised 280 IT audit findings and 84 were identified from outsourced IT service assurance reports. Of these 364 IT audit findings 218 (59 per cent) are now considered 'closed'.

Prior to 2014–15, audit findings from assurance reports were not re-reported in VAGO's management letters. These findings were, however, included in the Information and Communications Technology Controls Report 2013–14 (ICT Controls Report 2013–14). As VAGO has now started to report relevant weaknesses arising from assurance reports, all prior-period findings related to assurance reports have been closed and where relevant, new findings raised.

Figure 3E shows the remediation status of the 280 findings raised by VAGO in 2013–14. Forty-eight per cent of prior-period findings have been remediated, this is consistent with 41 per cent of the high-risk findings having been remediated.

Figure 3E

Prior year audit findings closed during the financial year

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

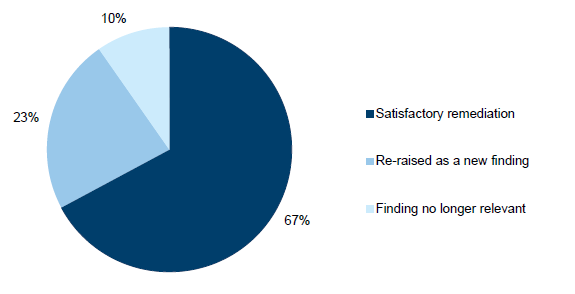

As shown in Figure 3F, findings have been closed for three reasons:

- Satisfactory remediation—management has acted on the recommendation and VAGO had not noted similar findings in 2014–15. These closed findings account for 67 per cent of the audit findings closed.

- Re-raised as a new finding—VAGO identified a similar finding in 2014–15, which demonstrates that management have not sufficiently remediated the problem. The practice of closing an audit finding and re-raising a new finding enables reporting to be streamlined by not having multiple audit findings relating to the same or similar control weakness. These findings account for 23 per cent of the audit findings closed.

- Finding no longer relevant—as a result of changes in an entity's organisation structure or IT environment, prior year audit findings may no longer be relevant or require any further remediation. For example, an IT system may have been decommissioned during the financial year and therefore all findings related to this system are no longer relevant. These findings account for 10 per cent of the audit findings closed.

Figure 3F

Insights on closed audit findings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In 2014–15, while in-scope entities made some progress in remediating prior year audit findings, the following areas still require improvement:

- Fixing symptoms rather than implementing process improvements—by not implementing process improvements, new control weaknesses may be introduced. For example, if a process that covers multiple IT systems is not improved, entities may only remediate the systems in-scope for our audit, rather than all IT systems.

- Ineffective governance—in-scope entities with strong governance structures are more likely to be proactive and successful in addressing the audit findings and preventing future recurrence. Those with poor governance structures are more likely not to remediate control weaknesses in a timely manner and have recurring audit findings.

3.4 IT general controls categories

3.4.1 User access management

Introduction

User access management relates to the process of managing access to applications and data, including how access is approved, revoked and periodically reviewed to ensure it is aligned with staff roles and responsibilities. User access management's primary objective is to maintain the confidentiality and integrity of IT systems and data.

This category also involves a review of the appropriateness of 'super users', who have wide-ranging authorisation within applications and systems, including the ability to create other users.

Weaknesses in user access management controls may result in inappropriate and excessive system and data access, which could affect the completeness and accuracy of transactions.

Audit procedures performed

We examined the policies and procedures governing this process, and evaluated the controls implemented by management to ensure access to systems and data is restricted to authorised users who require it for a legitimate business purposes.

Audit findings

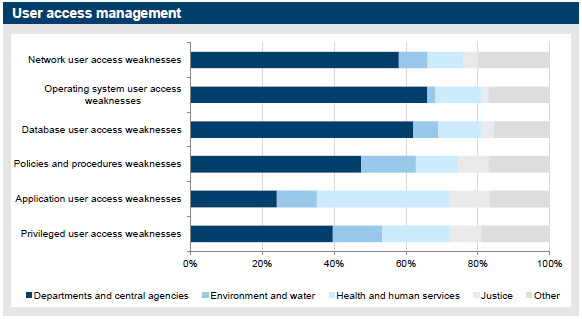

A total of 137 user access management findings were reported in 2014–15, representing 30 per cent of total findings and 33 per cent of high-risk audit findings, making this the category with the highest percentage of high-risk findings.

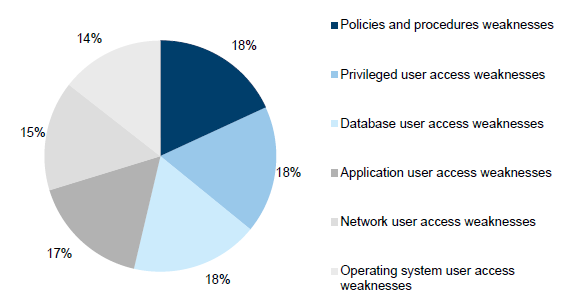

Figure 3G shows an even distribution of audit findings across the IT environment—database, application and operating system—which suggests that improvements are required at all levels.

Figure 3G

User access management audit findings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The 2014–15 results are consistent with last year's results. User account administration findings account for around 80 per cent of the control weaknesses, which is consistent with the prior year. User account administration typically covers matters such as:

- absence of appropriate approval prior to access being granted

- non-removal of user's system access following their termination

- non-review by management to ensure system access rights are aligned to the users role and responsibilities.

3.4.2 Authentication controls

Introduction

Authentication controls assist in determining whether a user attempting to access a system is who they claim to be.

Authentication is commonly performed through the use of passwords, and through the use of two-factor authentication in more tightly managed environments. Two-factor authentication includes something the user knows—i.e. a password—and something the user has—i.e. a security token.

Weaknesses in authentication controls may increase the risk of breaches in the confidentiality, integrity and availability of systems and data.

Audit procedures performed

We examined policies and procedures over password controls, and evaluated the password controls implemented by management to restrict access to in-scope IT applications and support infrastructure.

Audit findings

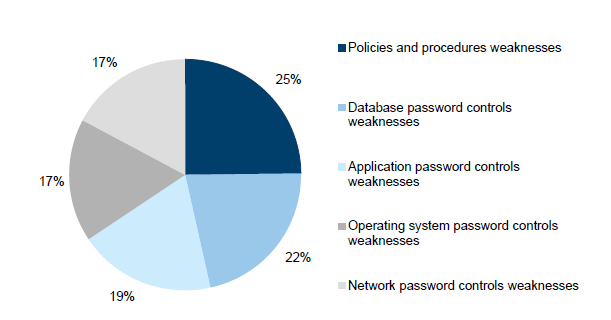

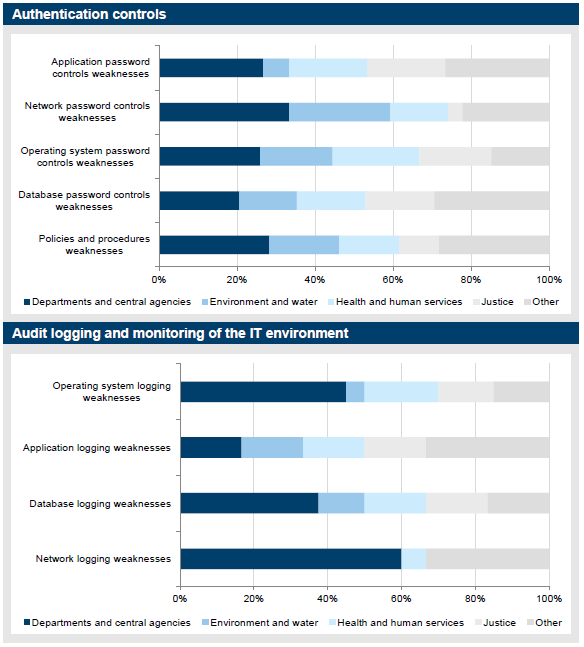

Authentication controls weaknesses accounted for 56 audit findings, or 12 per cent of the total. They accounted for 16 per cent of high-risk audit findings, with one finding rated as an extreme risk. As shown in Figure 3H, authentication controls audit findings are evenly spread across policy and procedure related weaknesses and password control weakness, across all IT components, namely the database, application layer, operating system and network.

Figure 3H

Authentication controls audit findings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In November 2013, a number of IT security standards were published by the former Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI) to take effect from 1 January 2014. One of the published standards—the Victorian Government's Identity and Access Management (IDAM) Standard 03 – Strength of Authentication Mechanism v1.0—provides specific guidance on password controls and aligns the overall Victorian IT control framework with the applicable Commonwealth standards and better practices, such as the Australian Government Information Security Manual. This standard is mandatory for all departments and 11 audited agencies.

Due to this development, in 2014–15 we noted a 20 per cent increase in findings related to entities' password controls that did not comply with these standards.

3.4.3 Audit logging and monitoring of the IT environment

Introduction

Audit logging and monitoring of the IT environment involves the recording and analysing of system and user activities in order to detect and mitigate unusual events within financial systems.

Weaknesses in audit logging and monitoring of the IT environment may lead to an increased risk that inappropriate or unauthorised activities could go undetected by management. Where inappropriate activities have occurred, management may not be able to trace the origins of the event due to incomplete or missing audit trails.

Audit procedures performed

We examined audit logging and monitoring policies and procedures, and evaluated the audit logging and monitoring controls implemented by management.

Audit findings

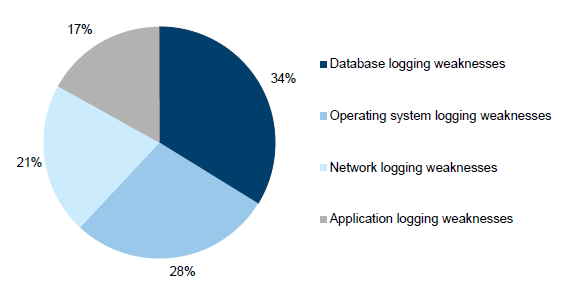

Audit logging and monitoring of the IT environment control weaknesses accounted for 34 audit findings, or 7 per cent of all findings. There was one high-risk audit finding, with most findings rated medium risk.

Figure 3I

Audit logging and monitoring audit findings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

As shown in Figure 3I, most audit logging and monitoring audit findings, accounting for 83 per cent of all audit findings raised, relate to the IT infrastructure level (database, operating system and network), with application logging and monitoring being generally stronger. This result is consistent with prior year.

3.4.4 IT change management

Introduction

The objective of IT change management is to make sure that changes to an IT environment are appropriate and preserve the integrity of underlying programs and data.

Weaknesses in IT change management may lead to unauthorised changes being made to systems and programs. This could impact the integrity of the data of underlying financial systems.

Audit procedures performed

We examined the policies and procedures governing IT change management. Where appropriate, we performed sample testing of changes to in-scope IT applications to validate whether the changes were appropriately authorised, tested and approved.

Audit findings

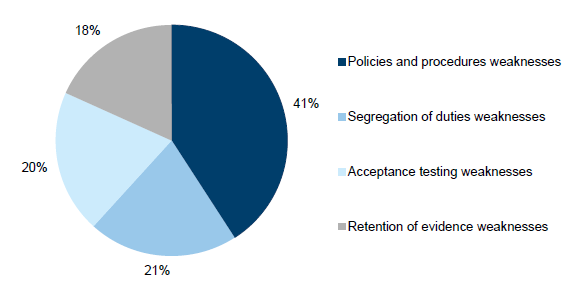

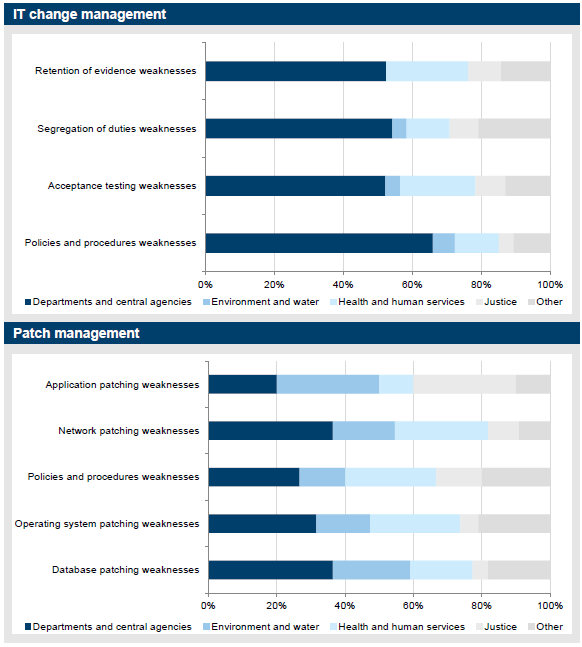

IT change management control weaknesses accounted for 55 audit findings, or 12 per cent of the total identified findings.

Figure 3J

IT change management audit findings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

As shown in Figure 3J a significant percentage (41 per cent) of IT change management findings relate to improvements required to policy and procedures. Change management policy and procedures drive operational processes. The other audit findings relating to change management were fairly evenly distributed among the following control activities:

- segregation of duties—change management staff have access to both production and non-production environments, such as development and test environments, increasing the risk that staff may both develop changes and implement them without appropriate oversight

- acceptance testing—inadequate levels of testing performed as part of the change process

- retention of evidence—insufficient documentation is retained to demonstrate that key controls are being performed.

3.4.5 Patch management

Introduction

A patch is an additional piece of software released by vendors to fix security vulnerabilities or operational issues. Periodic patching aims to reduce the risk of security vulnerabilities in systems and enhance the overall security profile of the IT infrastructure.

Where patches are not applied on a periodic basis, security vulnerabilities remain exposed. This may result in unauthorised access to systems and data, and increases the risk of financial, operational and reputational loss.

Audit procedures performed

We examined policies and procedures over patch management, and validated that in‑scope IT applications have been patched by management in accordance with policies and recommended industry practices.

Audit findings

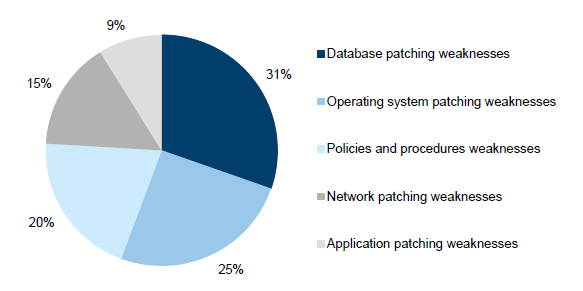

Patch management control weaknesses accounted for 32 audit findings, or 7 per cent of the total identified findings. These audit findings account for 6 per cent of our high‑risk findings. Figure 3K shows most IT change management findings related to database patching, operating system patching and policy and procedures. Collectively, these accounted for 76 per cent of all our patch management findings.

Figure 3K

Patch management audit findings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Patching was highlighted as one of the themes in last year's ICT Controls Report 2013–14, as an area requiring improvement. While we have seen improvements in 2014–15, the number of findings in this area has increased slightly from 26 last year. This increase is due to:

- entities who have done little to improve patch management processes

- new entities or systems subjected to IT audits.

In certain instances, where the process had not improved sufficiently, VAGO had elevated the risk rating to ensure management pays adequate attention to the matter.

3.4.6 Backup management, business continuity and IT disaster recovery planning

Introduction

Backup management, business continuity and IT disaster recovery planning involves the identification of the entity's business continuity requirements and data backup needs.

A business continuity plan details the response strategy of an organisation in order to continue operations and minimise the impact in the event of a disaster. An IT disaster recovery plan is a documented process to assist in the recovery of an organisation's IT infrastructure in the event of a disaster.

Weaknesses in backup management, business continuity and IT disaster recovery planning may impact the ability of an organisation to recover its critical systems and transactions in a complete and timely manner.

Audit procedures performed

We examined each organisation's policies surrounding data backups and the framework for business continuity and disaster recovery planning. Testing involved:

- examining whether backups are performed as intended, and whether data is periodically tested and recoverable

- examining if business continuity and disaster recovery plans exist, are updated, and are periodically tested by management.

Audit findings

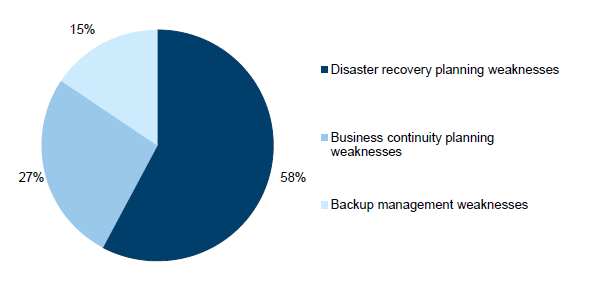

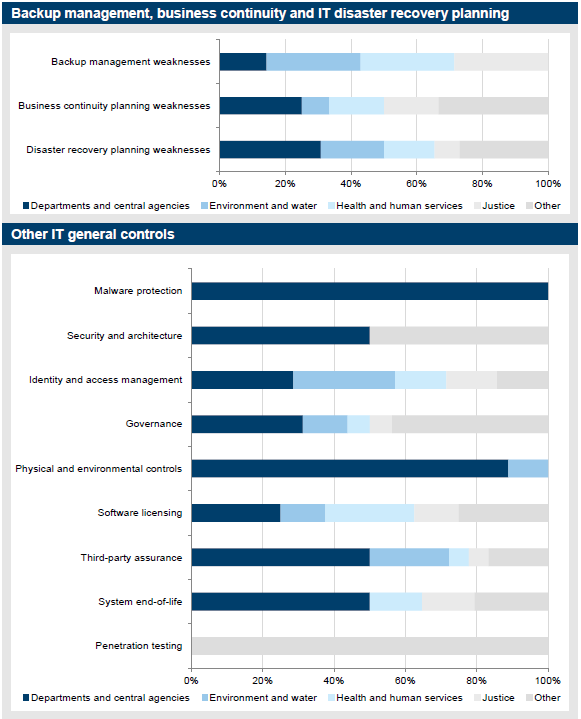

Collectively, backup management, business continuity and IT disaster recovery planning accounted for 36 audit findings, or 7 per cent of the total findings. Weaknesses in this category represent 6 per cent of our high-risk findings.

Figure 3L

Backup management, business continuity and IT disaster recovery audit findings

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 3L shows consistent results to the prior year, with the absence or limitations in disaster recovery planning accounting for 58 per cent of our findings, compared to 57 per cent the prior year. Fewer findings are raised in relation to backup management indicating this is better managed by entities, and this can act as a compensating control.

Disaster recovery planning was highlighted as a theme in last year's ICT Controls Report 2013–14 and while not reported as a key theme in this report, it still remains a significant concern. There continues to be no formalised framework in place at the whole-of-Victorian-government level which prioritises IT systems recovery in the event of a disaster impacting a number of departments and agencies. This is of particular concern where a number of department and agencies are dependent on the one IT service provider, as there may be resource challenges and differing views on priorities if such an event were to occur.

Specifically, the following had been noted:

- The service provider does not have sufficient IT disaster recovery capability to respond to a significant event.

- Departments and agencies are not informing themselves adequately about the service provider's IT disaster recovery capability.

- Because it is unassessed and unmanaged, the potential risk of IT failure after a significant event can be significant and unacceptable.

- Although the service provider had advised the departments and agencies in its annual attestations that it does not have an IT disaster recovery plan to address significant failures, there had been no action by the service provider to address the risk.

An inability by the departments and agencies, and their IT service providers, to react and respond appropriately could result in an interruption to the delivery of services to the community and reputational damage to the state and the entities involved.

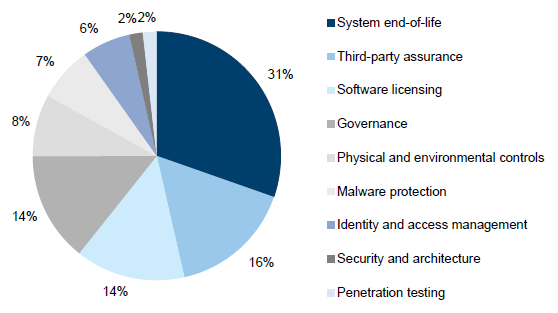

3.4.7 Other IT general controls

All the remaining IT audit findings have been included in the category 'other'. These findings include:

- IT systems at their end-of-life—relates to cases where the system vendor has, or is intending to stop or limit support for its product in the near future.

- Controls at outsourced IT environments—relates to the assurance that third‑party service providers are designing and operating appropriate controls over outsourced financial systems.

- Software licensing—relates to controls implemented to manage the purchasing and deployment of software and ongoing compliance throughout its use.

- Governance—relates to entity-level controls including overarching frameworks, policies and standards.

- Physical and environmental controls—relates to physical access to the IT infrastructure and environment controls, such as appropriate temperature and humidity controls, and continuity of power supply.

- Malware protection—relates to protection of network and computer systems from malicious software designed to cause disruption or damage to systems.

- Identity and access management—relates to how individuals are provided with an appropriate level of access to data and information, and aims to reduce inappropriate access.

- Security and architecture—relates to vulnerabilities or limitations in the organisation's network security configuration or management framework.

- Penetration testing—relates to the process and outcomes of a technical evaluation of the internal and external vulnerabilities of IT systems.

In 2014–15, changes in VAGO's IT audit methodology resulted in the areas of physical and environmental controls, security and architecture, and penetration testing being a lesser focus.

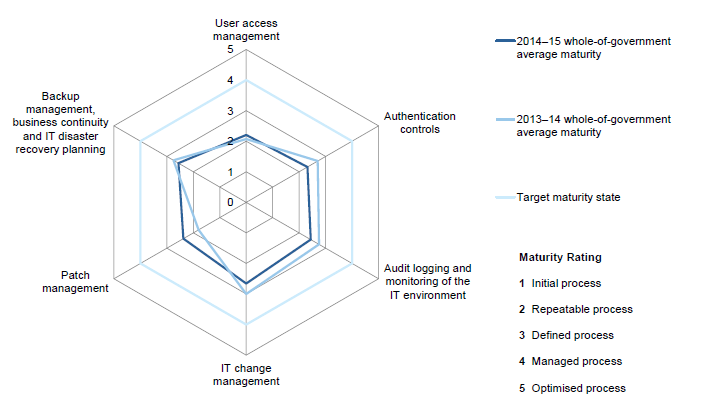

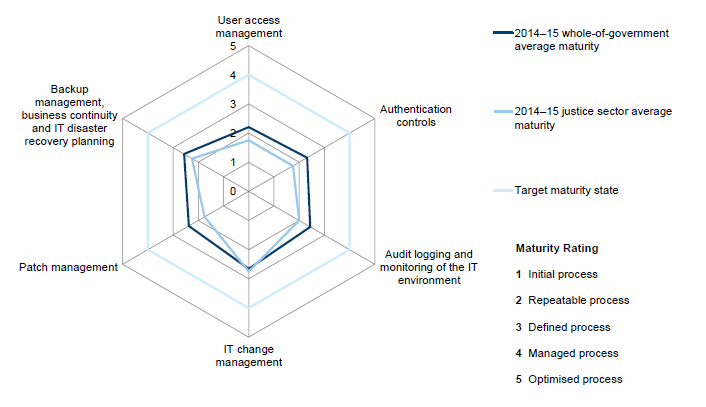

Audit findings