Fraud and Corruption Control

Overview

The community expects—and the law requires—that public sector employees act with integrity, accountability, impartiality, fairness, equity and consistency, and in the public interest.

Fraud and corruption can undermine trust in government, damage the reputation of the public sector, and waste public resources. Fraud is dishonest activity involving deception that causes actual or potential financial loss. Corruption is dishonest activity in which an employee acts against the interests of their employer and abuses their position to achieve personal gain or advantage for themselves or for others.

In this audit we examined the Melbourne Metro Rail Authority (MMRA), Public Transport Victoria (PTV) and the now defunct Major Projects Victoria (MPV), as examples of an administrative office, a statutory authority, and a business unit under the auspices of the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR).

We assessed whether their fraud and corruption controls were well designed and operating as intended.

We also assessed whether PTV took sufficient, appropriate and timely action to address issues identified by the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission’s Operation Fitzroy October 2014.

We made 11 recommendations for DEDJTR, and we made six further recommendations for PTV. All recommendations have been accepted.

Transmittal letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2018

PP No 385, Session 2014–18

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Fraud and Corruption Control.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

29 March 2018

Acronyms

| ABN | Australian Business Number |

| CMS | Contract management system |

| CSR | Construction Supplier Register |

| DEDJTR | Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources |

| DSDBI | Department of State Development, Business and Innovation |

| IBAC | Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission |

| MMRA | Melbourne Metro Rail Authority |

| MPV | Major Projects Victoria |

| MTIP | Major Transport Infrastructure Program |

| PTV | Public Transport Victoria |

| SPC | State Purchase Contracts |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VGPB | Victorian Government Purchasing Board |

| VPSC | Victorian Public Sector Commission |

| VSB | Victorian Secretaries' Board |

Audit overview

The community expects—and the law requires—that public sector employees act with integrity, accountability, impartiality, fairness, equity and consistency, and in the public interest.

Fraud and corruption can undermine trust in government, damage the reputation of the public sector, and waste public resources. Fraud is dishonest activity involving deception that causes actual or potential financial loss. Corruption is dishonest activity in which an employee acts against the interests of their employer and abuses their position to achieve personal gain or advantage for themselves or others.

The Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) has exposed instances of corruption in the Victorian public sector. In response, the Secretaries of all Victorian government departments committed to improving integrity.

In this audit, we examined the Melbourne Metro Rail Authority (MMRA), Public Transport Victoria (PTV) and the now defunct Major Projects Victoria (MPV), as examples of an administrative office, a statutory authority, and a business unit of the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR). The nature of MPV, MMRA and PTV's operations, including high levels of procurement activity and close ties to the private sector—which can operate differently to the public sector—serve to elevate the risk of fraud and corruption.

We assessed whether their fraud and corruption controls were well designed and operating as intended. DEDJTR designed and operated some of these controls for the whole department, while MMRA and MPV implemented other controls at the administrative office or business unit level. We also assessed whether PTV took sufficient, appropriate and timely action to address issues identified by IBAC's Operation Fitzroy October 2014 (Operation Fitzroy).

At MPV, MMRA and PTV we focused on fraud and corruption detection, prevention and response activities, particularly for the high-risk areas of procurement and human resources. We also assessed the DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit's oversight role and coordination of some relevant integrity processes for MPV and MMRA. The period of review for this audit was January 2015 to April 2017, when MPV ceased operations.

Conclusion

While senior executives are endeavouring to build the right culture, more remains to be done to prioritise fraud and corruption control, and to ensure that the fraud and corruption controls in place operate as intended.

Unduly protracted delays to finalise and approve Fraud and Corruption Control Policies and Plans, areas of noncompliance with policies, and inadequate record keeping are undermining management's efforts. They also serve to lessen assurance that major fraud and corruption cannot occur, or will be detected.

PTV was subject to public hearings as part of IBAC's Operation Fitzroy and agreed to address the issues identified by that investigation. PTV made considerable progress in implementing many of these initiatives, however in some cases implementation was slow, or did not occur, as PTV elected over time to take alternative action. Gaps remain in certain areas, meaning work is still required to further reduce the risk of fraud and corruption.

Findings

Fraud and corruption control framework

The Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance 2016 (Standing Directions) under the Financial Management Act 1994 require DEDJTR and PTV to take all reasonable steps to manage fraud and corruption risks. This includes developing a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses management and prevention policy (Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy) that details prevention, detection and response activities. The Australian Standard 8001—2008 Fraud and Corruption Control (Australian Standard) also recommends a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan be developed. An effective fraud and corruption control framework will also increase staff awareness and focus internal audits on vulnerable areas.

Fraud and Corruption Control Policies and Plans

A Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy has been mandatory for agencies since 1 July 2017. DEDJTR only recently finalised its Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy and Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. DEDJTR's policy and plan had been in draft form since October 2015, and while they were reviewed and revised during this time and reflect some controls already in place, they were only approved in late February 2018.

While DEDJTR's policy and plan was in draft form, MPV and MMRA developed their own plans, which they intended would also incorporate the requirements of a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy. MPV's plan also remained in draft form and was incomplete, as it did not include response procedures.

PTV developed a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan, which incorporated the requirements of a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy in accordance with the Standing Directions.

MPV, MMRA and PTV all conducted fraud and corruption risk assessments when developing their Fraud and Corruption Control Plans. However, in a small number of instances (three for MPV, one for MMRA and one for PTV) they identified a risk in their assessment but did not detail it or any associated controls in their Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. PTV was controlling for this risk in practice, however including it in its plan would make the plan stronger by detailing how PTV is mitigating risks specific to its operating environment.

Staff training and awareness

IBAC has repeatedly highlighted the need to develop a culture of integrity and notes that public sector officers are 'best placed' to identify and report corruption.

MMRA and PTV provided integrity training to their staff, while MPV as a business unit, received integrity training from the DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit.

From our work within MPV, we identified that DEDJTR more broadly was not taking sufficient steps to ensure that all of its staff know how to identify and respond to fraud and corruption.

For example, DEDJTR does not consistently maintain records of attendance at integrity training. There is no record to demonstrate, or readily check, that all staff in positions exposed to high risks of fraud and corruption have received integrity training.

While the DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit maintains records of completion of online integrity modules, these modules are mandatory only for new starters in DEDJTR.

MPV, MMRA and PTV all delivered training that provides a general awareness of fraud and corruption and how staff should respond to suspected incidents, as recommended by the Australian Standard. All made this training compulsory, however, only MMRA and PTV maintained records of attendance to track compliance with this requirement.

DEDJTR and PTV provide information to staff on the Protected Disclosure Act 2012 (which provides critical protections to individuals reporting improper conduct) during induction sessions and integrity training. They also have dedicated intranet pages, which guide staff about making a protected disclosure.

However, the effectiveness of this has been called into question by the results of the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC) People Matter Survey. In 2017 only 27 per cent of DEDJTR staff who responded, reported that DEDJTR had promoted the Protected Disclosure Act 2012. This compares with 29 per cent of DEDJTR respondents to the 2016 VPSC survey and 48 per cent of PTV respondents.

Internal audits

Under the Standing Directions, internal audit plans must include audits of business processes or units likely to be vulnerable to fraud, corruption and other losses.

MMRA and PTV's internal audit functions have provided appropriate coverage of fraud and corruption risks, with almost half of their audit activity in 2016–17 focusing on potentially vulnerable areas.

As a business unit within DEDJTR, MPV was subject to DEDJTR's internal audit program. We observed that the level of internal audit activity within MPV in 2016–17 was significantly lower than in MMRA and PTV. Following the government's decision to merge MPV and create a new statutory authority, DEDJTR advised us that it did not consider MPV a high-risk area warranting internal audit activity.

These management judgements and resource allocation decisions about MPV were made against a background of significant organisational change. In our opinion, this change would only have increased the risks inherent in a business unit that was continuing to manage large procurements, working closely with the private sector and maintaining processes that were separate to those of its department, DEDJTR.

Human resource practices providing fraud and corruption controls

Human resource practices that contribute to fraud and corruption controls include screening potential employees, and having processes to manage conflict of interest and offers of gifts, benefits and hospitality.

Such practices enhance transparency, facilitate external scrutiny and reinforce an integrity culture. As an administrative office and statutory authority respectively, MMRA and PTV have their own human resources functions. MPV, as a business unit received this service through DEDJTR.

Employment screening

Employers conduct employment screening to identify potential integrity concerns, and associated fraud and corruption risks, when hiring or promoting staff.

MMRA, PTV and DEDJTR's Human Resource functions are not fully implementing employment screening policies and procedures. Our testing highlighted deficiencies, including the failure to complete and document police checks, reference checks and qualification checks—or to respond appropriately when checks highlight anomalies. The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit initiated an audit into DEDJTR's employment screening practices, which confirmed our findings. The audit has been finalised and all the internal audit's recommendations have been accepted.

The Victorian Public Sector Code of Conduct and the declaration of private interests process require certain staff to self-declare criminal activity. Aside from these obligations there are currently no processes that identify existing staff who commit a criminal offence and do not self-declare. There are also no processes to identify existing staff who do not hold a required qualification.

Conflict of interest

Public officers have a conflict of interest if they have a private interest that could improperly influence, or be seen to influence, their decisions or actions in the performance of their public duties. Employees in certain positions must outline their private interests to agencies through an annual declaration of private interest process. In response, action plans must be developed and monitored to manage potential conflicts of interest.

We identified deficiencies in conflict of interest processes, specifically in the management of conflicts and potential conflicts. We identified instances where individuals had declared conflicts, but these conflicts were not actively managed, and action plans were not enforced.

PTV and DEDJTR, incorporating MPV and MMRA, maintain conflict of interest registers. In some instances data within these registers were poor, which could limit the ability of managers to monitor declared interests and enforce action plans.

MMRA, PTV and DEDJTR Human Resources functions were not consistently using declarations of conflicts of interest during recruitment processes to guard against hiring based on factors other than merit, as required by VPSC guidance endorsed by the Victorian Secretaries' Board (VSB). This left them open to risks of fraud and corruption when hiring.

Gifts, benefits and hospitality

VPSC requires agencies to develop policies governing how their staff should respond to offers of gifts, benefits and hospitality to ensure they remain impartial when making decisions. Public sector staff must not accept gifts, benefits and hospitality from current or potential suppliers. MPV, MMRA and PTV all maintained gifts, benefits and hospitality registers and DEDJTR maintained a central register, which incorporated MPV and MMRA.

Gifts, benefits and hospitality policies were in place, however, these policies were not always operating as intended, and therefore not providing the protections they should.

Of particular concern were the high proportion of gifts, benefits and hospitality accepted by MPV staff from their suppliers with the endorsement of MPV management. Of the total offers accepted by MPV staff, 74 (46 per cent) were from suppliers.

The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit oversaw MPV's gifts, benefits and hospitality processes and did not provide any evidence of action to remedy this situation, despite knowing of these practices. DEDJTR has advised that it has strengthened its processes in relation to gifts, benefits and hospitality over the past few months.

Fraud and corruption control in procurement practices

Procurement is a high-risk activity for fraud and corruption requiring strong controls. Controls should include a well-designed procurement framework and processes to manage conflicts of interest in procurement activity. To prevent and detect fraud and corruption, there must be vetting of potential suppliers and monitoring of procurement data.

Procurement framework

The strength of procurement frameworks for controlling fraud and corruption varied across MPV, MMRA and PTV.

MMRA has a procurement framework with strong controls for fraud and corruption. MPV's procurement controls had significant weaknesses such as poor conflict of interest processes during procurements and a lack of appropriate procurement monitoring. This was concerning given MPV's status at the time as the Victorian Government's specialist project delivery agency.

PTV has made progress in improving its procurement controls after Operation Fitzroy, but in some instances, these improvements occurred slowly or PTV implemented them inconsistently. In particular, PTV's procurements under $25 000 are not subject to conflict of interest controls, or central monitoring of spend. This lack of oversight, means that PTV is more vulnerable to fraud and corruption for these lower value transactions.

Supplier vetting

At the time of the audit, MPV, MMRA and PTV had not developed or consistently implemented guidelines to vet suppliers. We acknowledge the varying levels of use of suppliers on the Construction Supplier Register (CSR) and State Purchase Contracts (SPC), where suppliers are subject to whole of government vetting checks. DEDJTR estimates that up to 95 per cent of MPV's procurement was done through the CSR or SPC.

MPV, MMRA and PTV's Fraud and Corruption Control Plans all listed activities that could make up a program to vet suppliers. However, MPV, MMRA and PTV had not implemented supplier vetting guidelines that outlined which checks they would conduct beyond simple Australian Business Number (ABN) checks. This gap means they were missing a basic opportunity to reduce fraud and corruption risks associated with procurements involving third parties.

Conflict of interest processes in procurement

MPV staff only completed a conflict of interest declaration for each project they worked on, which could span a number of years and include multiple procurement activities. This practice did not comply with DEDJTR's procurement policy or VPSC guidance, which requires a separate declaration specific to every procurement and vendor.

MMRA has strong documented conflict of interest controls, which apply to all officers involved in any procurement over $2 000.

We found instances of noncompliance with conflict of interest management plans at both MPV and MMRA, demonstrating that even when employees declared relationships, senior management did not effectively manage these conflicts.

For example, we found one instance where an executive endorsed the decision to award a $3.9 million contract to a supplier for whom they had previously worked and in which they held shares. The executive had previously declared this conflict but the management plan was not enforced.

There has been a clear improvement in compliance under PTV's new procurement framework. PTV has demonstrated full compliance with conflict of interest controls for procurements under their new framework since March 2017. PTV could only produce four of eight conflict of interest forms for procurements tested under their old framework.

Monitoring fraud and corruption indicators

Monitoring procurement activity helps detect fraud and corruption. A strong monitoring and reporting program can also deter potential perpetrators of fraud and corruption, as it increases the chance of detecting irregular and inappropriate activity.

MPV, MMRA and PTV all had weaknesses in their monitoring and reporting of fraud and corruption indicators associated with procurement.

They provided evidence that they monitored and reported to their executive on generic procurement trends to varying degrees. However, monitoring activities for fraud and corruption indicators were less consistent, with MPV and MMRA unable to provide any evidence of such monitoring.

DEDJTR is developing a data analytics program, which is currently being trialled by MMRA. When fully implemented, this program will significantly improve reporting capacity.

PTV had reported on fraud and corruption indicators in procurement, although poor data quality in the contract management system (CMS), and PTV's inability to retain skilled data analytics staff, resulted in unreliable data and inconsistent monitoring. PTV does not currently monitor procurements worth less than $25 000, placing such procurements at a higher risk of fraud and corruption.

Response to fraud and corruption

To maintain public trust, the public sector must respond actively to instances of suspected fraud and corruption. Keeping records, including action taken in response to incidents, is a mandatory legislative requirement under the Standing Directions.

Better practice outlined in the Australian Standard recommends that an entity maintain a fraud and corruption register. Legislated external reporting to integrity agencies such as IBAC and the Victorian Auditor-General's Office (VAGO) provides a level of external scrutiny and enables systemic analysis. The Australian Standard recommends establishing a response team to coordinate activities. After fraud and corruption has occurred, entities should take steps to recover public funds and property that have been lost.

Fraud and corruption registers and response teams

MMRA and PTV both maintain detailed registers that outline how they have considered each alleged fraud and corruption incident and the action taken in response. As a business unit MPV was considered by DEDJTR's register.

The Integrity Services Unit at DEDJTR maintains a central register of integrity matters ranging from complaints to fraud and corruption allegations. However, the information is uncategorised, outdated and in some instances inaccurate, which limits this register's usefulness.

When reviewing the register, we were not able to consistently determine which entries related to fraud and corruption allegations, what action DEDJTR had taken and whether a financial loss had occurred.

MMRA and PTV have established response teams to coordinate response activities and recording, with appropriate senior representation. The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit acts as the response team for DEDJTR as a whole and includes senior staff at the executive level.

Investigations

Internal investigations need to be timely, transparent, clearly documented and able to withstand external scrutiny. Poor investigations can diminish stakeholder confidence in an organisation's ability to effectively manage and respond to incidents of fraud and corruption.

DEDJTR decided to outsource investigations into fraud and corruption as it recognised that investigations required specialised resources and expertise. A sample of the investigations conducted by external contractors showed appropriately conducted investigations, which resulted in detailed investigation reports with key findings and recommendations.

We found investigations conducted by MMRA and PTV to be timely, thorough, well documented and conducted by suitably qualified external contractors where appropriate. MMRA and PTV also demonstrated how they had learned from the investigations and strengthened their controls.

MPV identified no instances of fraud and corruption, and hence conducted no investigations in 2014–15, 2015–16 and 2016–17.

Reporting

The Victorian government established IBAC in 2012 to identify, expose and investigate corruption. Under legislation, certain prescribed public sector body heads were required to notify IBAC of corrupt conduct, while others, including DEDJTR and PTV, had discretion to notify IBAC of such matters.

We identified one instance for PTV in 2013 and one instance for DEDJTR in 2016 where they did not report relevant matters to IBAC. At the time both had discretion over whether to report such matters.

Parliament strengthened the legislation in December 2016 to remove discretion and create a mandatory requirement for public sector agency heads to notify IBAC of suspected corruption. Parliament changed the legislation to ensure that all significant matters of corrupt conduct are brought to IBAC's attention.

Under the Standing Directions, agencies are now required to notify external parties, such as IBAC and VAGO, of incidents of significant or systemic fraud and corruption. DEDJTR has reported low levels of losses due to fraud and corruption under the Standing Directions. These low levels may be partly attributable to DEDJTR's treatment of missing assets. DEDJTR labels assets that cannot be located as 'disposed' in its accounts, without considering whether they were stolen. In response, DEDJTR has advised that it will ensure that policies and procedures for identifying and reporting lost assets include referring matters to the Integrity Services Unit to assess the possibility of fraud.

Recovery efforts following fraud and corruption

The Australian Standard recommends entities have a policy that considers recovering funds lost to fraud and corruption. Government entities should clearly document decisions on taking recovery action when public funds are lost to fraud and corruption, including decisions not to take action.

We identified examples where DEDJTR and PTV did not attempt to recover losses due to fraud and corruption, but did not document their decision-making process or rationale.

PTV did not document why it did not seek to recover significant funds lost due to fraud and corruption identified by Operation Fitzroy, estimated by IBAC to have involved $25 million of corrupted procurement, or a myki ticketing fraud in which PTV incurred losses of $4.8 million.

Following concerns identified by the former Department of State Development, Business and Innovation, DEDJTR found in 2015 that an organisation had obtained grant funding of more than $65 000 and was not able to demonstrate that it had provided the services for which the funding had been given. DEDJTR also found that the organisation had submitted documentation in support of the services, which was of questionable authenticity. DEDJTR also concluded that the organisation had demonstrated systemic noncompliance with a number of grant conditions. DEDJTR gave the organisation an opportunity to submit evidence of other services provided to acquit the funding already obtained, instead of seeking recovery.

In this matter, DEDJTR determined that it had not incurred any financial loss that required reporting under the Standing Directions. This position fails to account for DEDJTR's initial conclusion that it had paid more than $65 000 for services that could not be validated, and relies on the organisation's agreement to provide other services to the amount paid as detailed above. DEDJTR's handling of this matter failed to acknowledge the likelihood that fraud had occurred and consider fully the need to recover public funds.

There are complexities to potential recovery activity in some of the examples we considered. However, the failure to adequately document decision-making processes and rationales about public funds inhibits transparency.

PTV's response to Operation Fitzroy

Following IBAC's Operation Fitzroy, PTV committed to a broad range of reform initiatives, including:

- developing new policies and procedures

- appointing new specialist positions

- procuring new systems

- implementing an extensive program of fraud and corruption specific training.

PTV made significant progress in implementing its reform agenda to develop a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan, establish a response team and conduct an extensive fraud and corruption training program for staff. However, PTV implemented important procurement and financial control reforms slowly, with some still outstanding. Existing gaps in controls fail to reasonably minimise PTV's fraud and corruption risks.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources:

- fully implement its Fraud and Corruption Control Policy and Plan (see Section 2.3)

- identify all staff working in areas with the highest risk of fraud and corruption; and:

- develop and implement a strategy to provide them with integrity training and

- track completion of the training to ensure appropriate coverage and awareness (see Sections 2.4 and 2.5)

- work collaboratively with its agencies to support them in meeting Victorian Public Sector Commission requirements for conflict of interest practices in recruitment panels (see Section 3.4)

- through its Integrity Services Unit, continue to scrutinise declarations of private interest and related management plans and work collaboratively with its agencies to ensure consistency and active management of declared conflicts (see Section 3.3 and 3.4)

- through its Integrity Services Unit continue to scrutinise agency gifts, benefits and hospitality registers, and work collaboratively with agencies to proactively address noncompliance while working towards having a single register to improve oversight (see Section 3.5)

- develop and implement appropriate supplier vetting guidelines (see Section 4.3)

- work collaboratively with its agencies to develop appropriate fraud and corruption indicators and procurement reporting processes (see Section 4.5)

- formalise information sharing processes between its Integrity Services Unit and its agencies to facilitate appropriate feedback on integrity matters that are referred to agencies for action or information (see Section 5.4)

- ensure that it documents decision-making regarding efforts to recover losses due to fraud and corruption and collaboratively works with its agencies to support them to do the same (see Section 5.5)

- improve the reporting capacity of its Integrity Services Unit's integrity register to capture whether allegations are substantiated, losses are incurred and action taken, and ensure that the register captures all matters reported to it (see Section 5.2)

- finalise its review of the treatment of missing assets to ensure that there is consideration of whether losses are caused by fraud and corruption (see Section 5.4).

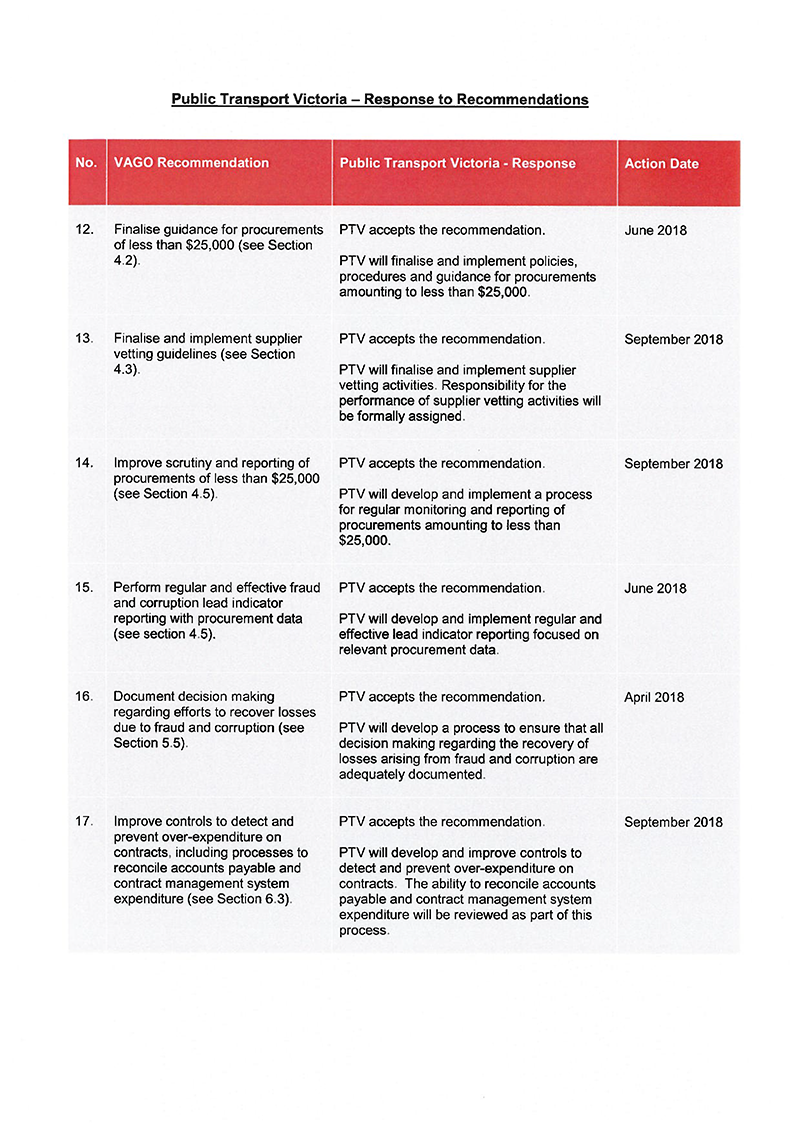

We recommend that Public Transport Victoria:

- finalise guidance for procurements of less than $25 000 (see Section 4.2)

- finalise and implement supplier vetting guidelines (see Section 4.3)

- improve scrutiny and reporting of procurements of less than $25 000 (see Section 4.5)

- perform regular and effective fraud and corruption lead indicator reporting with procurement data (see Section 4.5)

- document decision making regarding efforts to recover losses due to fraud and corruption (see Section 5.5)

- improve controls to detect and prevent over-expenditure on contracts, including processes to reconcile accounts payable and contract management system expenditure (see Appendix B).

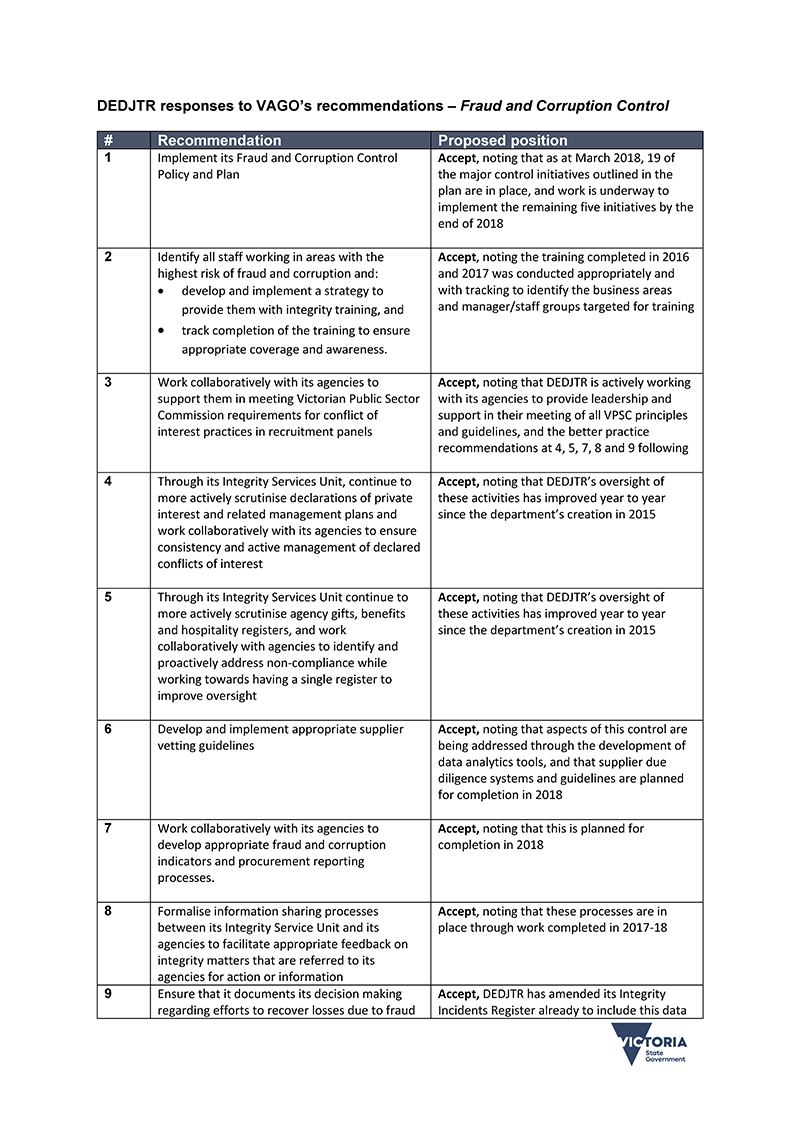

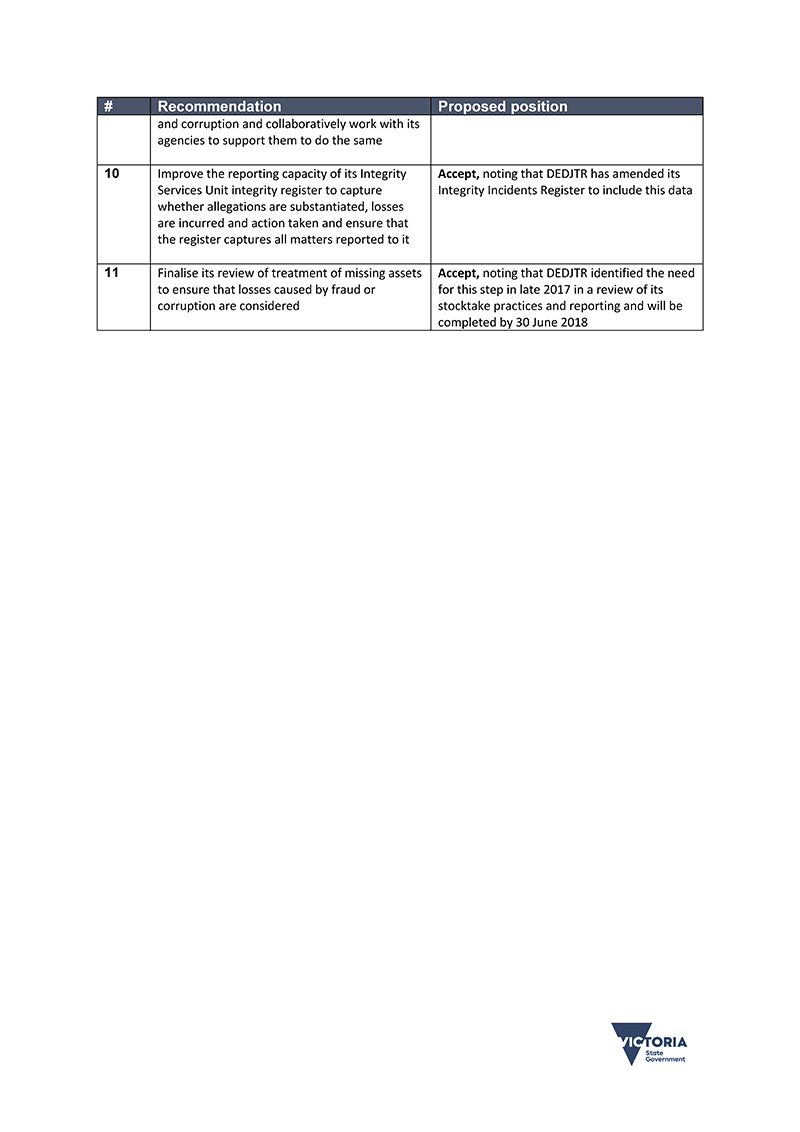

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DEDJTR and PTV and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

DEDJTR noted it is deeply committed to developing and maintaining a strong integrity culture. DEDJTR accepted the recommendations, noting that the recommendations reflect activities already in progress and due for completion in 2018.

PTV noted its efforts since Operation Fitzroy to create an ethical culture that does not tolerate fraud and corruption. PTV advised that it will continue to endeavour to further improve its framework, processes and controls for managing fraud and corruption. PTV accepted the recommendations and stated it intends to address them all by September 2018.

1 Audit context

The community entrusts public sector employees to make decisions that affect the lives and interests of all Victorians. They handle personal information, provide services and support, and manage, spend and account for public funds. The community expects—and the law requires—that they do this with integrity, accountability, impartiality, fairness, equity and consistency, and in the public interest.

Citizens need to have a level of trust and respect for their public institutions and the rule of law for society to function cohesively. The financial value of reported fraud and corruption in the Victorian public sector, including corruption exposed by IBAC, is minor relative to overall agency budgets. However, fraud and corruption can undermine trust in government and damage the reputation of the public sector. If left unchecked, it can affect the quality of services provided and can waste resources.

1.1 What are fraud and corruption?

Fraud is dishonest activity involving deception that causes actual or potential financial loss. Examples of fraud include:

- theft of money or property

- falsely claiming to hold qualifications

- false invoicing for goods or services not delivered or inflating the value of goods and services

- theft of intellectual property or confidential information

- falsifying an entity's financial statements to obtain an improper or financial benefit

- misuse of position to gain financial advantage.

Corruption is dishonest activity in which employees act against the interests of their employer and abuse their position to achieve personal gain or advantage for themselves or for others. Examples of corruption include:

- payment or receipt of bribes

- a serious conflict of interest that is not managed and may influence a decision

- nepotism, where a person is appointed to a role because of their existing relationships rather than merit

- manipulation of procurement processes to favour one tenderer over others

- gifts or entertainment intended to achieve a specific outcome in breach of an agency's policies.

1.2 Losses resulting from fraud and corruption

It is difficult to measure total losses due to fraud and corruption. As well as financial losses, there are also indirect losses, including damage to the community's trust in government and losses to productivity. There are no precise figures, but in 2005 the Australian Institute of Criminology estimated that fraud cost the Australian economy $8.5 billion across the private and public sectors.

Under the Standing Directions, public sector agencies in Victoria are required to report to VAGO instances of fraud, corruption and other losses above $5 000 in cash and $50 000 in property. Reports made to VAGO for 2015–16 record about $19 million lost to fraud and corruption. However, these figures do not capture indirect losses, and any loss due to poor integrity is significant for public sector agencies and the communities they serve.

Figure 1A shows that IBAC investigations published between 2014 and 2017 revealed procurement and tendering processes totalling up to $275 million had been impacted by corruption. IBAC uncovered a further $2 million in improperly obtained personal benefits.

Many of the cases of fraud and corruption exposed by IBAC had gone undetected for some years.

Figure 1A

IBAC investigations: Approximate financial values of corruption

|

Date |

Investigation name |

Agency subject to investigation |

Impact of corruption |

|---|---|---|---|

|

April 2017 |

Operation Nepean |

Department of Justice and Regulation |

Impacted $1.6 million worth of payments |

|

March 2017 |

Operation Liverpool |

Department of Health and Human Services |

Resulted in $101 000 of personal benefits being obtained |

|

January 2017 |

Operation Dunham |

Department of Education and Training |

Impacted a project worth $127−240 million |

|

October 2016 |

Operation Exmouth |

Places Victoria |

Impacted $8 million worth of payments |

|

April 2016 |

Operation Ord |

Department of Education and Training |

Resulted in $1.9 million of personal benefits being obtained |

|

October 2014 |

Operation Fitzroy |

Former Department of Transport and PTV |

Impacted $25 million worth of contracts |

Source: VAGO based on information from IBAC.

1.3 Legislation and guidance

In Victoria, legislation and guidance material support public sector agencies to develop and implement fraud and corruption control frameworks, as Figure 1B outlines.

Figure 1B

Legislation and guidance for fraud and corruption control frameworks

|

Instrument |

Requirements |

|---|---|

|

Public Administration Act 2004 |

Mandatory compliance Details Victorian public sector values and employment principles. Its purpose is to provide a framework for good governance and outline the responsibilities of departmental heads. |

|

Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees |

Mandatory compliance VPSC issues the Code of Conduct, which is binding for employees. It prescribes standards of required behaviour and includes provisions on:

|

|

Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance 2016 |

Mandatory compliance Sets the standards for financial management by Victorian Government agencies, and requires the responsible body to:

Instructions supporting the Standing Directions require agencies to develop policies and procedures that apply the minimum accountabilities set out in the VPSC Gifts, Benefits and Hospitality Policy Framework. |

|

Protected Disclosure Act 2012 and Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 |

Mandatory compliance The purpose of the Protected Disclosure Act 2012 is to encourage and facilitate disclosures of improper conduct by public officers, public bodies and others, and to provide protections for people who make disclosures. If a body can receive protected disclosures, it must have effective procedures to facilitate the making of disclosures, including notifications to IBAC. Changes to the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 require that from 1 December 2016, all relevant principal officers of public sector bodies must notify IBAC of any matter they suspect on reasonable grounds involves corrupt conduct. |

|

Australian Standard 8001—2008 Fraud and Corruption Control |

Better practice guidance Provides general guidance on controlling fraud and corruption by Standards Australia, a peak not-for-profit organisation, independent of government, which develops standards in Australia. This includes the development of a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. The Standing Directions and guidance issued by IBAC use the definitions outlined in the Australian Standard. |

Source: VAGO.

Departmental Secretaries must ensure that their department's 'relevant public entities' meet legislative responsibilities. Under the Public Administration Act 2004, Secretaries are responsible for:

- the general conduct and management of the functions and activities of the department and any administrative offices existing in relation to the department

- working with and providing guidance to each relevant public entity on matters of public administration and governance.

1.4 Why this audit is important

IBAC's Operation Fitzroy investigation into the conduct of two officers of the former Department of Transport and PTV found that these officers and their associates corrupted $25 million worth of public contracts to benefit themselves. To minimise the waste of public funds and reassure the Victorian public of the public sector's integrity, it is important that public sector entities appropriately address weaknesses that increase the risk of fraud and corruption, including those identified by Operation Fitzroy.

1.5 Audited agencies and their responsibilities

DEDJTR

Government established DEDJTR in January 2015, and its responsibilities include transport and ports, investment attraction and facilitation, trade, innovation, regional development, small business, and key services to sectors including agriculture, the creative industries, resources and tourism. It employs over 3 000 people and operates from 96 sites across Melbourne and regional Victoria, and 22 international offices.

DEDJTR is the portfolio department for PTV. The Secretary of DEDJTR has responsibilities under the Public Administration Act 2004 for its portfolio agencies.

DEDJTR established an Integrity Services Unit in October 2015 to build its integrity capability, with specialist external resources providing supplementary skills when required. The unit is responsible for implementing the DEDJTR Integrity Framework, which applies to all DEDJTR employees in administrative areas, and to agencies for whom the Secretary is the employer. The unit is also responsible for developing and maintaining policies and systems that directly support integrity. Staff from the unit also sit on panels that act as an escalation point for certain integrity policies, and report to the Secretary and the audit, risk and integrity committee on systems that support integrity. Responsibilities of the Integrity Services Unit include:

- managing gifts, benefits and hospitality processes

- managing protected disclosures

- managing a declarations of private interest process

- drafting the Fraud and Corruption Control Plan

- implementing the Integrity Framework

- developing data analytics capability.

The Australian Standard recommends that entities complete data mining and real-time computer system analysis to detect potential instances of fraud and corruption. DEDJTR's Integrity Framework states that the DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit will develop and maintain a data analytics program.

MPV

MPV was the Victorian Government's in-house project delivery agency, and was a business unit in DEDJTR. It provided project delivery services and advice to Victorian Government departments. MPV ceased operating on 1 April 2017 following a merger with Places Victoria to form Development Victoria, which is a statutory authority within the DEDJTR portfolio.

MMRA

MMRA's objective is to deliver the $10.9 billion Metro Tunnel by 2026. MMRA is responsible for all aspects of the project, including planning and development, site investigations, stakeholder engagement, planning approvals and procurement, construction and project commissioning. MMRA is an administrative office within DEDJTR. The Coordinator-General sits within DEDJTR and has responsibility for overseeing the Major Transport Infrastructure Program (MTIP), of which MMRA is part.

PTV

Government established PTV in 2012 to plan, coordinate, operate and maintain Victoria's public transport system. PTV is a statutory authority in the DEDJTR portfolio. Following changes to the Transport Integration Act 2010, government disbanded the PTV board in April 2017 and transferred management powers to the PTV chief executive officer.

1.6 What this audit examined and how

This audit examined whether MMRA and PTV have, and MPV did have, well‑designed fraud and corruption controls that operate as intended.

We considered the role of the DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit in overseeing and supporting the practices outlined in DEDJTR's Integrity Framework, while testing the practices in MPV, MMRA and PTV. We also considered DEDJTR's role when performing certain functions, such as internal audit for MPV, reporting actual or suspected fraud, corruption or other losses, and safeguarding resources and assets under the Standing Directions.

MMRA and MPV were included in this audit because their work involves high‑risk factors for fraud and corruption, including:

- high levels of procurement

- use of contractors

- partnerships with the private sector.

PTV was included so we could assess whether it has taken sufficient, appropriate and timely action to address the issues identified by IBAC's Operation Fitzroy.

The Standing Directions and guidance issued by IBAC use definitions outlined in the Australian Standard. The Australian Standard outlines a suggested approach for entities to control for the risk of fraud and corruption. It describes key risk areas for fraud and corruption, and includes guidance for the development and implementation of a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. The Australian Standard includes minimum acceptable standards for entities seeking to fully comply.

The Australian Standard divides activities into three main elements—prevent, detect and respond—as detailed in Figure 1C.

Figure 1C

Fraud and corruption control activities

Source: VAGO.

We assessed the effectiveness of the controls at the audited agencies across these three elements, with a focus on two high-risk areas—procurement and human resources.

Our areas of focus considered legislative obligations, better practice outlined in the Australian Standard, and guidance from VPSC.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $740 000.

1.7 Report structure

Figure 1D

Structure of this report and areas of focus in this audit

|

Structure |

Audit focus |

Activities and controls examined |

|---|---|---|

|

Part 2 |

Fraud and corruption control framework |

Risk assessment to inform Fraud and Corruption Control Plan Fraud and Corruption Control Policies and Plans Staff training in fraud and corruption risks Staff awareness, including protected disclosures Internal audits focus on areas vulnerable to fraud and corruption Data analytics |

|

Part 3 |

Fraud and corruption prevention and detection in human resources practices |

Employment screening Declarations of private interests Recruitment panel members declare conflicts of interest Management of gifts, benefits and hospitality |

|

Part 4 |

Fraud and corruption prevention and detection in procurement practices |

Procurement framework design Supplier vetting Conflict of interest processes in procurement Monitoring fraud and corruption indicators in procurement |

|

Part 5 |

Response to fraud and corruption |

Fraud and corruption incident register and response teams Investigations Reporting Recovery efforts following fraud and corruption |

Source: VAGO.

Appendix B looks at whether PTV has taken sufficient, appropriate and timely action to address the issues identified by IBAC's Operation Fitzroy.

2 Fraud and corruption control framework

To achieve better practice in managing fraud and corruption, the Australian Standard suggests that entities develop a framework that includes:

- risk assessments to inform fraud and corruption controls

- a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan outlining the entity's approach to controlling the risk of fraud and corruption, from prevention through to detection and recovery

- training and other activities to develop staff awareness of fraud and corruption risks and how to respond.

The Standing Directions under the Financial Management Act 1994 require agencies to establish a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy, implemented across the agency.

We assessed whether fraud and corruption frameworks were in place to govern the activities of MPV, MMRA and PTV. We also considered if the frameworks were consistent with Standing Directions requirements and better practice principles set out in the Australian Standard.

2.1 Conclusion

MPV and MMRA would have been subject to DEDJTR's Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy and Fraud and Corruption Control Plan as a business unit and administrative office. However, DEDJTR only finalised its policy and plan in late February 2018. DEDJTR's protracted delay in finalising and approving these documents meant it was not compliant with the Standing Directions under the Financial Management Act 1994, which required a policy to be in place from 1 July 2017, or better practice requirements of the Australian Standard.

Without a final approved DEDJTR policy and plan, MPV and MMRA developed their own Fraud and Corruption Control Plans. They intended these to also incorporate the elements of a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy, as required under the Standing Directions. PTV developed a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan compliant with the Australian Standard. This plan also included the requirements of a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy under the Standing Directions

DEDJTR can do more to assure itself that all of its staff know how to identify and respond to fraud and corruption. DEDJTR does not consistently maintain records of attendance at integrity training. There are limited records to demonstrate, or readily check, that all staff in positions exposed to high risks of fraud and corruption have received integrity training. While DEDJTR Integrity Services maintains records of completion of online integrity modules, these modules are mandatory only for new starters in DEDJTR.

In addition, DEDJTR staff are reporting poor promotion of the Protected Disclosure Act 2012, and DEDJTR's internal audit program has given insufficient attention to high-risk activities undertaken by MPV, including procurement. These gaps undermine messages from DEDJTR's leadership that preventing, detecting and responding to fraud and corruption is an organisational priority.

PTV provided extensive mandatory fraud and corruption training to its staff, and its internal audit activity has appropriately considered fraud and corruption risks.

2.2 Risk assessment

The Australian Standard recommends that entities complete a preliminary assessment of fraud and corruption risks to inform the development of a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. This risk assessment should consider risks inherent in the entity's industry and core business and should help determine the scope of controls outlined in the plan.

We examined whether MPV, MMRA and PTV had conducted risk assessments to inform their Fraud and Corruption Control Plans.

MPV

MPV conducted fraud and corruption risk assessments in early 2014 and December 2015. The 2015 assessment identified multiple risks and proposed steps for mitigation, but did not outline who was responsible for mitigating risks. There is little evidence to confirm how the mitigation strategies were considered or implemented. One undated document provided by DEDJTR listed the 12 risks identified and noted a number were complete and a number were estimated for completion in mid-2016. The risk assessment identified accounts payable fraud and poor contract management as high-priority risk areas. Proposed steps to mitigate these risks, included:

- regular analysis of contract variations

- exception reporting

- computer-assisted techniques to identify procurement splitting (where contracts are split into parts of lesser value, so that certain controls do not apply) and instances where vendors were consistently engaged by the same project manager.

MPV's Fraud and Corruption Control Plan did not reference the identified risks of low-value procurement fraud, accounts payable fraud and the manipulation of project management data. The plan also did not include the mitigation controls suggested by the risk assessment.

We note that a large number of the recommendations made in the risk assessment referred to the use of data analytics, and we discuss DEDJTR's progress in implementing a data analytics program in Section 2.7. We also note that DEDJTR would have captured MPV in this program had it remained as a business unit in DEDJTR.

We identified concerns with the comprehensiveness of the risk assessment. MPV identified the risk of abuse of power as unlikely. The assessment identified staff accepting inappropriate gifts as an indication of the intent to corruptly influence. As detailed in Section 3.5, MPV staff accepted gifts, benefits and hospitality from suppliers. We confirmed that 46 per cent of accepted offers of gifts, benefits and hospitality came from contractors and vendors. MPV's mitigation strategy was running fraud and corruption awareness training to acquaint staff with the available avenues to report fraud and corruption, but as detailed in Section 3.5, it did not take sufficient action to avoid the general risks associated with public sector officers accepting offers from suppliers.

MMRA

MMRA's master risk register confirms that fraud and corruption risks have been considered and rated within the broader risk program. The register assigns identified risks to owners with detailed mitigation strategies and includes an implementation status.

MMRA has implemented the mitigation strategies suggested in the risk assessment. For example, the assessment identified the inappropriate access of information as a significant risk. A suggested strategy was conducting an internal cyber-security audit, which commenced in mid-2017.

MMRA's risk assessment reflects fraud and corruption risks that were not identified in the MPV or PTV risk registers, although they would be equally relevant—for example, 'kickbacks' for existing employees assisting candidates to secure roles at MMRA. However, this particular risk did not flow through to the Fraud and Corruption Control Plan and, as discussed in Section 3.4, MMRA was not controlling for this risk by using conflict of interest declarations for recruitment panel members.

PTV

PTV has conducted thorough fraud and corruption risk assessments. The assessments include detailed mitigation strategies and assign identified risks to owners. We noted one instance where an identified risk did not flow through to the Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. PTV identified cyber security threats as a high-level risk and detailed potential causes, consequences and controls, but did not reflect this in the Fraud and Corruption Control Plan.

Although PTV is managing the risk, including this information in the plan would make the plan stronger by detailing how PTV is mitigating risks specific to its operating environment.

2.3 Fraud and Corruption Control Policies and Plans

Under the Standing Directions, DEDJTR and PTV must establish a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy. The Australian Standard suggests the development of a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan that outlines an entity's approach to controlling fraud and corruption.

We assessed whether Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policies and Fraud and Corruption Control Plans compliant with the Standing Directions and consistent with the Australian Standard had been developed and implemented to support MPV, MMRA and PTV.

MPV and MMRA

As a business unit and administrative office, MPV and MMRA would have been subject to the policy and plan of their portfolio department, DEDJTR. DEDJTR only finalised its Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy and Plan in 2018. The plan and policy had been in draft form since October 2015, and while they had been reviewed and revised during this time, they were not approved and finalised until late February 2018. As these documents were not finalised, DEDJTR did not have an agency-wide policy to prevent and manage fraud and corruption, and did not comply with the mandatory Standing Directions under the Financial Management Act 1994, which required a policy to be in place from 1 July 2017, or better practice under the Australian Standard.

Prior to the finalisation of the policy and plan, DEDJTR had reported that it relied on its 2015 Integrity Framework to give effect to its fraud and corruption control activities. The DEDJTR Integrity Framework is a valuable high-level document outlining a strategic approach for promoting a culture of integrity in DEDJTR and, as a new department, where it intended to direct its efforts to implement integrity structures, processes and resources. While the Integrity Framework is a positive indication of the culture that DEDJTR wants to develop, it does not provide the focus and detail of a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy or Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. As the Integrity Framework does not provide the necessary detail on preventing, detecting and responding to fraud and corruption, it is not compliant with the Standing Directions or consistent with the Australian Standard. The Integrity Framework describes a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan as a first line of defence and in October 2015 stated that DEDJTR was drafting such a plan.

During the course of this audit, the DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit acknowledged the delay in finalising its policy and plan. DEDJTR advised us, when the documents were in draft form, that it expected the finalised policy and plan would largely formalise controls that were already in place. However, DEDJTR is yet to fully implement certain controls, including a suite of due diligence policies and a data analytics program. DEDJTR has committed to finalising these controls in 2018.

The case studies in Figures 2A and 2B reflect the sophistication of fraud attempts faced by DEDJTR.

In March 2016, although unsuccessful, DEDJTR was subject to an attempted phishing attack seeking payment of $400 000. A year later, in April 2017, DEDJTR was subject to another phishing attack, this time successful.

Figure 2A

Case study: Attempted phishing scam in 2016

|

In March 2016, DEDJTR was subject to an attempted phishing attack that was successfully blocked. An external party sought payment of $400 000. The scam took the form of an email from an executive officer seeking urgent payment of an invoice. The request was feasible, based on the executive's business area, but a senior finance officer declined to process the request as the amount exceeded the executive's financial delegation and there was no purchase order. DEDJTR investigated the matter and found that the email was from an external party using a 'masked' email address. DEDJTR also found that most of the information used to construct the invoice and emails to make them look plausible was available on DEDJTR or whole-of-government websites. The attack was successfully blocked but DEDJTR reviewed and strengthened its controls after it concluded that it could have succeeded if:

|

Source: VAGO based on DEDJTR information.

Figure 2B

Case study: Successful phishing scam in 2017

|

In April 2017, DEDJTR was the victim of a second phishing scam and made four payments totalling more than $294 000 to a bank account falsely represented as belonging to an existing supplier. The existing supplier alerted DEDJTR that it had not received payment and that DEDJTR may have been the victim of a phishing scam. DEDJTR contacted its bank and the bank recovered nearly $290 000. DEDJTR wrote‑off about $4 600. An employee did not comply with internal controls, and processed a request to change bank account details without first verifying the information provided. In response to this incident, DEDJTR strengthened its controls. DEDJTR now requires vendors to complete a form and provide supporting documentation to change bank details. An authorised officer then reviews and assesses the request against publicly available information about the vendor. A memorandum to the Secretary in July 2017 regarding this incident noted that DEDJTR's Fraud and Corruption Control Plan would be finalised in 'the coming weeks'. The plan was finalised in February 2018. DEDJTR's internal audit function has reviewed the revised controls and is currently auditing their effectiveness given they have been in place for six months, which is a positive indicator of DEDJTR's efforts to manage ongoing phishing attempts. |

Source: VAGO based on DEDJTR information.

IBAC has noted that leadership is key to creating an ethical culture and the 'tone from the top' is essential. These case studies highlight the importance of strengthening the culture and awareness of fraud and corruption risks. While DEDJTR's Integrity Framework is a positive step towards building and maintaining an integrity culture, a finalised Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy and Fraud and Corruption Control Plan, which are communicated to staff, could have significantly reinforced these efforts at the time. Without a final approved DEDJTR policy and plan, MPV and MMRA developed their own Fraud and Corruption Control Plans.

MPV

MPV developed a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan but it remained in draft form. The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit advised that MPV's director of governance and business was responsible for the plan, but this director left MPV in December 2016. MPV continued to operate until 31 March 2017.

The MPV draft Fraud and Corruption Control Plan did not reference key aspects that we would expect in a plan compliant with the Standing Directions and consistent with the Australian Standard, including:

- policies or procedures to report fraud and corruption to external agencies

- how matters would be investigated

- internal reporting requirements.

MPV's failure to finalise and review its Fraud and Corruption Control Plan, and develop associated procedures, is concerning given it managed significant projects on behalf of the government.

MMRA

MMRA applied the Australian Standard by developing a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. This was superseded in February 2017 by a plan that MTIP developed to cover all of its entities. This plan also meets the requirements of a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy under the Standing Directions

The MTIP plan references relevant internal policies and procedures, as well as external resources, including IBAC's Investigation Guide. The plan also highlights management's commitment to fraud and corruption control, with reference to mandatory annual fraud and corruption awareness training for all staff. MTIP tailored the plan to reflect its business context.

PTV

PTV developed a Fraud and Corruption Control Plan in September 2014, which is consistent with the Australian Standard and has been subject to regular reviews. This plan also meets the requirements of a Fraud, Corruption and Other Losses Policy under the Standing Directions. PTV also developed a separate and detailed Fraud and Corruption Response Procedure. Access to this procedure is restricted to safeguard PTV's investigative approach when responding to fraud and corruption. PTV's plan and response procedure demonstrate its commitment to this initiative after Operation Fitzroy.

Fraud and Corruption Control Plans

The Australian Standard provides a detailed template for use by entities and the plans we reviewed strongly align with this. The plans describe:

- roles and responsibilities for the management of fraud and corruption in the agency

- relationships with other agency procedures and policies

- mechanisms for the communication and awareness of fraud and corruption

- terms and definitions.

However, we found one significant example where the plans did not reflect the agencies' specific risks or practices—the MPV, MMRA and PTV plans all had identical sections for supplier vetting, copied directly from the Australian Standard. None had tailored this section to reflect their specific procurement environments, risks or actual practices. This raises the risk that there may not be adequate controls in this area—see Section 4.3 for further information.

2.4 Staff training

The Australian Standard suggests that entities train staff to be aware of fraud and corruption, and educate them on how to respond.

The Australian Standard notes that employees do not identify a significant proportion of fraud and corruption at an early stage because they are unable to recognise warning signs, are unsure how to report concerns or lack confidence in the available reporting systems. Various IBAC investigations have found that corrupt conduct went undetected for a number of years, highlighting the importance of training as a preventative activity.

We assessed the training provided to MPV, MMRA and PTV staff to determine whether it was consistent with recommendations in the Australian Standard.

MPV, MMRA and PTV

The MPV, MMRA and PTV training material is consistent with the Australian Standard. It includes:

- definitions, costs and examples of fraud and corruption

- IBAC's role and investigations

- warning signs for fraud and corruption and internal controls

- references to the Victorian Public Sector Code of Conduct and relevant policies

- reference to the DEDJTR Integrity Framework

- details on how to make a protected disclosure and use DEDJTR's 'report a concern' mechanism (an online portal that allows for anonymous reporting).

The training was mandatory for MPV, MMRA and PTV but only MMRA and PTV were able to provide records of attendance to confirm compliance.

The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit provided training to MPV staff, which the Chief Executive Officer mandated. DEDJTR has advised that records of attendance were completed but they could not be located for the purposes of this audit. By not maintaining documentation, DEDJTR could not provide assurance that MPV staff had received sufficient information to respond effectively to fraud and corruption.

In response to Operation Fitzroy PTV committed to changing the culture and encouraged and equipped staff to identify, report and act on integrity matters. In the two years following the investigation, PTV ran an extensive mandatory training program on fraud and corruption risks, including specialised training for those involved with the management of contracts and procurements, and for members of the fraud and corruption control response team. PTV subsequently developed online training modules with a dedicated focus on fraud and corruption. PTV's ongoing training program reflects good practice and demonstrates PTV's commitment to fraud and corruption control.

DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit

The training material we reviewed is consistent with the Australian Standard. The material described vulnerable areas in DEDJTR, referenced relevant policies, provided opportunities for discussing integrity dilemmas and encouraged staff to contact the Integrity Services Unit if they had concerns.

Documentation provided by the DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit shows that its staff frequently conduct integrity training to raise awareness and education across DEDJTR. The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit delivers three types of face‑to-face integrity training:

- integrity conversations delivered to senior staff which consist of information sharing on key integrity matters

- integrity training sessions which are scenario-based and engage participants in more formal learning

- induction sessions.

In instances where business units requested the training, the business unit kept attendance records. The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit has not consistently maintained records of staff who completed face-to-face training. As a result, DEDJTR cannot demonstrate or readily check that staff in positions exposed to high risks of fraud and corruption have received integrity training.

The DEDJTR Integrity Services Unit has introduced online integrity modules, which include a fraud and corruption component. DEDJTR has designed the modules for staff to complete each year. However, completion is mandatory only for new employees who are completing induction. DEDJTR has provided records that show 728 new staff completed the online modules as part of their induction program in 2016–17, and 34 managers have completed training since a manager's integrity toolkit was launched in late 2017.

DEDJTR can improve its preventative approach to fraud and corruption by ensuring wider reach of its training offerings, such as mandatory online modules, and recording staff completion of training to identify gaps.

2.5 Staff awareness, including protected disclosures

Fraud and corruption is secretive and difficult to detect. IBAC describes public sector employees as 'best placed' to identify suspicious conduct by their colleagues or concerns about external parties, such as contractors and suppliers. Public sector employees need to know how to report concerns and have confidence that their employer will protect them from any reprisals. Promotion of key integrity polices and processes, including the Protected Disclosure Act 2012, is vital. This increases the capacity of staff to detect and report possible instances of fraud and corruption.

We assessed VPSC survey results for DEDJTR (including MPV and MMRA) and for PTV staff to determine if key integrity polices and processes are promoted effectively.

VPSC People Matter Survey

There has been communication with staff by PTV, MMRA and DEDJTR, on behalf of MPV, about broad integrity issues, in the form of emails, staff bulletins, forums and training. However, levels of staff awareness of certain integrity policies and procedures, reported in the VPSC People Matter Survey, do not always reflect these efforts.

DEDJTR and PTV provide information to staff on the Protected Disclosure Act 2012 (which provides critical protections to individuals reporting improper conduct) during induction sessions and integrity training. They also have dedicated intranet pages, which guide staff about making a protected disclosure. PTV has information regarding disclosures in its Fraud and Corruption Control Plan. DEDJTR has recently established a new workplace conciliator role. DEDJTR anticipates that this role will promote staff awareness of a range of avenues for reporting issues or concerns, including protected disclosures. The role will work collaboratively with the Integrity Services Unit.

Every year, VPSC runs the People Matter Survey, which asks, among other things, if participants have seen or heard communication about particular policies in the past 12 months.

Figure 2C shows the results for 2016 and 2017. The data reflect particularly low awareness by DEDJTR and PTV staff of the promotion of processes to support the Protected Disclosure Act 2012 and reporting of improper employee conduct. Results for DEDJTR include MMRA and MPV staff. As the results also reflect the wider department, and MMRA and MPV only make up a small proportion of the total DEDJTR staffing numbers, the survey results are not necessarily reflective of MMRA or MPV staff responses.

Figure 2C

Reported promotion of integrity policies

|

Policy |

DEDJTR |

DEDJTR |

PTV |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Code of Conduct |

73% |

77% |

67% |

|

Public sector values |

71% |

74% |

49% |

|

Processes for reporting improper employee conduct |

51% |

49% |

71% |

|

Processes to support the Protected Disclosure Act 2012 |

27% |

29% |

48% |

|

Policy on giving and receiving of gifts and benefits |

88% |

83% |

88% |

|

Policy to assist employees to avoid conflicts of interest |

70% |

69% |

76% |

Note: PTV did not participate in the People Matter Survey in 2017 and MPV was no longer in existence.

Source: VAGO based on VPSC data.

These results show good levels of reported promotion of certain policies, such as gifts and benefits and the Code of Conduct. However, these results call into question the effectiveness of promotion activities and training provided to staff by DEDJTR in relation to protected disclosures.

For PTV, the results may reflect that it cannot receive protected disclosures, though this does not negate the need for its staff to know how to make one. Comparing DEDJTR's 2017 People Matter Survey results with like departments shows that its promotion of processes for reporting improper employee conduct and processes to support the Protected Disclosure Act 2012 are below the departmental averages of 64 per cent and 37 per cent respectively.

If protected disclosure policies are not effectively promoted, staff are less likely to use this mechanism. This reduces the ability to detect fraud and corruption and means that individuals wishing to report improper conduct may not receive the protections available to them under the Protected Disclosure Act 2012.

2.6 Internal audit

Internal audits are an important part of an effective control environment for fraud and corruption. Internal audits can monitor controls, detect weaknesses and make recommendations to strengthen controls. Under the Standing Directions, internal audit plans must include audits of business processes or units likely to be vulnerable to fraud, corruption and other losses.

We assessed whether internal audits in MPV, MMRA and PTV were considering fraud and corruption risks.

MPV

As a DEDJTR business unit, MPV was included in DEDJTR's internal audit activities, which cover a large and varied portfolio. Despite being responsible for complex projects and undertaking high levels of procurement, MPV was not subject to the same levels of internal audit activity as MMRA and PTV, which maintain their own internal audit functions.

In 2016–17, DEDJTR's internal audit program included only one audit with a specific focus on MPV. This was a follow-up audit to determine whether MPV had implemented the outstanding recommendations highlighted in our 2015 performance audit Follow up of Managing Major Projects. It did not assess fraud and corruption controls.

Although DEDJTR has conducted internal audits into vulnerable areas, these audits have not covered processes that MPV, as a business unit, maintained separately to DEDJTR. For example, DEDJTR completed an internal audit of accounts payable, but the audit did not include MPV's accounts payable system, which was separate to DEDJTR's.

In addition to DEDJTR's internal audit function, in late 2015, MPV engaged a contractor to complete data analytics work to assess fraud and corruption risks. Further discussion of MPV's response to the findings of this assessment are contained in Section 2.2. The contractor identified the following risks:

- procurement splitting

- variations to contracts being inaccurately reflected

- opportunity for bank account details to be manipulated in the electronic payment file

- opportunities for MPV staff to authorise payments which exceeded their financial delegations.

DEDJTR advised that as MPV would merge to become a statutory authority, it was not considered a high-risk area for DEDJTR's internal audit program, which also had to consider resourcing and budget constraints. DEDJTR also advised that as a relatively new department, it focused its internal audit program on core business processes affecting the whole department at this time.

We consider that MPV was a risk area for fraud and corruption, due to MPV undergoing significant organisational change, continuing to manage large procurements, working closely with the private sector and maintaining separate processes to DEDJTR.

MMRA

MMRA operates its own internal audit function and conducted more than 30 internal audits during 2016–17. Fraud and corruption risks were appropriately covered, with almost half of the 2016–17 audits focusing on potentially vulnerable areas, including:

- contract management

- gifts, benefits and hospitality

- contractor and staff recruitment

- the fraud and integrity control environment

- conflicts of interest and confidentiality.

MMRA clearly linked internal audit activity to the risks it identified in risk assessments. MMRA identified the inappropriate access of information as a significant risk. Controls for this risk include internal audits, the development of security plans, and the maintenance of usage and access logs. MMRA is currently conducting an internal audit on cyber security, which includes assessing the physical security of data, and having the internal auditors try to use deception and non-standard testing methods to gain access to data, systems and applications.

PTV

PTV's internal audit program is appropriately considering fraud and corruption risks. PTV's 2016–17 internal audit program planned 10 audits, with five considering vulnerable areas including:

- delegations of authority

- payroll processes

- asset management.

PTV operates an outsourced internal audit model, with PTV's internal audit division managing the contract. In an outsourced internal audit model, it is important that the team that manages the contract is properly resourced. This includes representation at a senior level to ensure audit teams properly rate the seriousness of audit findings and that business units appropriately respond.

During Operation Fitzroy, IBAC was concerned about the ad hoc auditing processes of PTV's outsourced internal audit provider. IBAC also questioned the effectiveness of PTV's audit and risk management function. IBAC did not fully explore this issue in its investigation, but we found evidence to support this concern. The case study in Figure 2D describes a 2013 internal audit conducted prior to IBAC's investigation and is an example of improperly classified audit findings that PTV did not act on appropriately at that time.

Figure 2D

Case study: Inappropriate rating of audit findings

|

In August 2013, PTV's outsourced internal audit function completed a report on procurement. The report identified a lack of controls over information in the vendor master file as a low-level finding. Internal audit testing at PTV found:

The internal audit concluded that a 'lack of controls over the vendor master file creation and maintenance activities increases the risk of fictitious vendors being set up, which may potentially lead to fraudulent activities and financial losses. Inaccurate, incomplete, duplicated or outdated information in the supplier master file increases the risk of payments made to inaccurate or inappropriate suppliers and reduces the effectiveness of expenditure tracking and reporting.' According to the report, a low-level audit finding: