Major Infrastructure Program Delivery Capability

Snapshot

Are relevant public sector agencies strategically planning the material and human resources needed to deliver Victoria’s major infrastructure projects?

Why this audit is important

Victoria’s major projects pipeline has expanded dramatically since 2016, particularly for transport projects. Coinciding with this, the infrastructure boom on Australia’s east coast has led to competition for workers and material resources.

To deliver projects cost-effectively and on time, public sector agencies need to identify resource gaps and strategically address any shortages.

Who we examined

- Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and its Office of Projects Victoria

- Department of Transport (DoT) and its Major Transport Infrastructure Authority

- Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR).

What we examined

We examined if agencies:

- have assessed the resources needed across the pipeline

- have addressed resource shortages and risks

- collaborate with each other and the relevant industries to plan for resources.

What we concluded

The audited agencies are not sufficiently strategic in planning for the material and human resources they need to deliver major government infrastructure projects. The consequence of this is that the risk of cost overruns and delays will be higher than it needs to be.

The agencies have identified potentially critical resource shortages and risks. However, there are significant gaps in the information they use to assess and address these shortages and how they coordinate this work.

As a result, no agency fully understands the construction industry and public sector's ability to deliver the government’s pipeline, or how effective their work to mitigate resource shortages is. The audited agencies' advice to government does not consistently disclose the extent of these knowledge gaps. This reduces the reliability of their advice to the government about these risks.

What we recommended

We made 11 recommendations to the audited agencies. Nine of these apply to DTF, four to DoT and three to DJPR.

Six relate to the need for the agencies to determine the size and timing of resource shortages and risks for the government and transport pipelines.

Five are about strengthening the agencies’ advice to government and their planning on how to address shortages and risks.

Video presentation

Key facts

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A. We use the audited agencies’ current names throughout the report for simplicity. Section 1.4 identifies their former names for reference.

Assessing resource shortages and risks

Extractive materials are quarry products, such as rock, gravel and sand.

To support the delivery of major infrastructure projects, the audited agencies need to understand the human and material resources required. We focused on how they assess four key aspects of these resources:

- the construction industry workforce

- the public sector workforce

- the construction market, which includes construction firms and supply chain businesses

- the building materials used, such as the supply of extractive materials and disposal of contaminated earth removed during construction.

Contaminated spoil is the earth that tunnelling and construction activities dig up that does not meet standards for ‘clean’ waste. The level of contamination influences whether it can be re-used, treated or sent to landfill.

If an agency finds or predicts a shortage, it needs to design and implement strategies to address it to mitigate the potential impact on project delivery. However, the audited agencies' current ability to advise the government about shortages and mitigation strategies is limited because their resource assessments are outdated and there are gaps in their data.

Identifying shortages and risks

Except for the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions’ (DJPR) forecasts about extractive materials, the audited agencies' assessments of resource shortages and risks lack quantitative data. They also lack accurate and current detail about the size and timing of most identified shortages. In particular:

|

Audited agencies have assessed the … |

and have identified shortages and risks, such as … |

But the accuracy of these assessments is reduced because … |

|

industry workforce |

in 2020, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF), working with other departments and audited agencies, identified that 17 construction skill areas have a high risk of shortages. |

national data classifications are limited to certain occupation types, which makes it hard for DTF, the Office of Projects Victoria (OPV) and the Major Transport Infrastructure Authority (MTIA) to quantify the size and timing of shortages in many specific occupation types, such as ‘tunnelling engineer’ and ‘road constructor’. |

|

in 2020, MTIA assessed that 98 per cent of high-skilled construction occupations will have some level of shortage between 2022 and 2025. |

||

|

public sector workforce |

in 2016 and 2017, DTF and MTIA determined that departments and delivery agencies were concerned about the high risk of shortages in project leadership, commercial and legal expertise and technical skills. |

DTF, OPV and MTIA have not updated their assessments since 2017 or collected the data they need to quantify the size of any shortages. |

|

construction market |

in 2020, DTF, OPV and MTIA identified the risk that the small pool of domestic tier 1 construction firms may not be able to take on new major projects. |

DTF, OPV, MTIA and the Department of Transport (DoT) do not collate data on how many domestic tier 2 and 3 firms and international tier 1 firms could participate in the government and transport pipelines. |

|

building materials |

in 2016, DJPR forecast shortages in the extractive materials needed for future construction in the state (not just the government pipeline) by 2026. It predicted that these shortages would further increase by 2050. |

due to commercial confidentiality issues, DJPR has had difficulty getting reliable data from quarry operators and the construction industry on the volume of materials that can potentially be supplied from existing and planned quarries and what the demand from major projects is likely to be. DJPR is working to improve its data collection, for example introducing new regulations requiring quarries to report on their available resources from July 2021. Since the 2016 forecasts, DJPR has implemented actions to address forecast shortages. However, the government pipeline has continued to expand significantly since then. These factors are changing both supply and demand for extractive materials. |

|

in 2020 DoT, working with other departments and audited agencies, assessed that Victoria does not have enough re-use, treatment or landfill sites available to manage the rapidly increasing volumes of contaminated spoil that the government pipeline is generating. |

DoT has not yet quantified the state’s capacity to re-use, treat or dispose of contaminated spoil but is planning to do this. It has not estimated how much spoil upcoming projects, such as the Suburban Rail Loop, are likely to generate. |

Tier 1 construction firms are firms that typically manage Victoria’s larger infrastructure projects, such as projects worth over $1 billion.

Tier 2 firms typically work on major projects up to $500 million or contribute to tier 1 consortiums on larger projects.

Tier 3 and below firms typically work on projects below $100 million and are part of the supply chain for larger projects.

While most of these assessments are recent, some of the extractive materials and public sector workforce assessments date back to 2016 and 2017.

DTF, OPV and MTIA continue to rely on outdated information about risks to the public sector’s ability to deliver the government pipeline. This is despite the government’s annual infrastructure investment more than doubling from $9.1 billion in 2016–17, when these agencies last assessed the workforce, to a forecast $24.2 billion in 2021–22. While the public sector workforce is a smaller component of major projects than the industry workforce, it is still critical to ensuring projects are scoped, procured and managed well.

DTF and OPV are the central agencies that oversee the government pipeline’s delivery. However, they have not consolidated information about shortages from all of the audited agencies' assessments. As a result, they do not have a holistic understanding of the size and timing of shortages for the entire government pipeline.

This lack of a holistic understanding, and knowledge gaps about the size and timing of shortages, mean the audited agencies do not have the information they need to:

- prioritise which shortages to address first to support the government pipeline's delivery

The government pipeline is the program of all major government infrastructure projects. The transport pipeline is the transport sector subset of the government pipeline.

Major projects are projects valued at $100 million or more. These include megaprojects, which are valued at $2 billion or more.

- determine the type and scale of actions that they or other departments and agencies need to deliver to increase the capability and capacity of the industry and public sector workforces, market and materials

- accurately advise the government about the likely impacts of shortages on the delivery of the government pipeline and the actions required to mitigate these risks.

Modelling resource capability and capacity

DJPR, OPV and MTIA each use technically reliable models to forecast specific aspects of the construction industry workforce:

- DJPR models employment demand for the whole state, across all industries.

- OPV models the demand for construction industry workers for major projects.

- MTIA has modelled the supply and demand for industry workers for the transport pipeline.

In this report, capability refers to the skills and experience that the industry and public sector workforces need to deliver a major project.

Capacity refers to the availability of construction firms that can bid for a major project contract and the quantity of human and material resources required to deliver it.

DJPR and OPV also work with the Department of Education and Training (DET) when developing their forecasts. DET models industry workforce supply for the state as part of its work managing the technical and further education (TAFE) and training system. DJPR and DET's statewide models predate OPV's new workforce modelling for government major projects.

DJPR also models the supply and demand for extractive materials.

Constraints to the modelling

DJPR, OPV and MTIA designed their industry workforce models to meet specific but separate information needs. They did not design them to also integrate with each other. The differences in their forecasting methods, assumptions, constraints and outputs mean DJPR and OPV cannot join their models together or with DET's in their current forms. As a result, DJPR and OPV's models do not provide consistent and reliable information about the size and timing of skill shortages. The lack of integration is a missed opportunity for these agencies to better understand:

- the human and material resources that the industry needs to deliver the government pipeline

- how supply and demand for resources across the government pipeline influences the transport pipeline.

DJPR and OPV’s models also do not consider macro economic factors that influence labour supply, such as government policies that impact workforce capability.

The ANZSCO system is a framework for classifying occupations. The classifications identify broader groups of construction occupations but do not list all individual occupations in the construction industry. For example, while there is a classification for civil engineers, it does not separately identify some subtypes, such as tunnelling engineers.

Additionally, DJPR's workforce modelling does not include the distribution of skills across the occupations and industries under the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO). This means DJPR only forecasts employment by industry, and not by occupations within industries.

OPV's workforce model only forecasts demand for individual projects and subsets of projects. It cannot model demand for the entire government pipeline, even though this would improve its understanding of potential shortages for individual projects.

OPV and MTIA’s models do not distinguish between ‘relative’ shortages, which occur when there are enough people who want employment but need training or incentives to enter the industry, and absolute shortages, which occur when there are simply not enough people wanting work. When the government decides how to overcome a shortage, this distinction is fundamental because it determines the types of actions that it can take.

Improvements to models

DJPR, OPV and MTIA are updating their models to address some of these limitations. DJPR is also developing a new model to improve its 2016 assessment of supply and demand for extractive materials.

In 2020, DTF and DET jointly led the Skills Interdepartmental Committee (IDC), which included all of the audited agencies. The Skills IDC, which ceased operating in December 2020, aimed to coordinate and develop actions to build the industry workforce. It identified the need for OPV and DJPR to integrate their models with DET’s to understand supply and demand in the construction market.

OPV and DJPR have started work to better share and align results and analysis between their separate models, and with DET's. However, OPV and DJPR are not planning to revise and integrate their models. Without this they cannot address the differences in their modelling approaches and provide reliable information to government about skill shortages that may impact the government and transport pipelines.

Recommendations about assessing resource shortages and risks

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Treasury and Finance, including the Office of Projects Victoria Department of Transport, including the Major Transport Infrastructure Authority |

1. to the extent possible, collect and collate comprehensive, accurate, quantitative information, research and analysis to annually estimate and monitor the size and timing of resource shortages and risks across the government pipeline (see sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, 2.4 and 2.5) | Accepted by: Department of Treasury and Finance Department of Transport |

| Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions | 2. in consultation with the Department of Treasury and Finance and its Office of Projects Victoria, the Department of Education and Training and other relevant agencies, leads the development of an integrated, aggregate, macro-economic model of the Victorian economy that can determine key drivers of the labour market (see Section 2.6) | Accepted in principle by: Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions |

| 3. ensures that the state's employment demand modelling includes the distribution of skills across occupations and industries under the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations and works with other agencies as needed to do this (see Section 2.6) | Accepted in principle by: Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions | |

| Department of Treasury and Finance, including the Office of Projects Victoria | 4. revises its major projects industry workforce demand modelling to enable it to:

|

Partially accepted by: Department of Treasury and Finance |

| 5. works with the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions and the Department of Education and Training to ensure its revised major projects workforce demand model integrates with their state macro-economic and industry workforce models to identify potential skills shortages across the government pipeline (see Section 2.6) | Accepted by: Department of Treasury and Finance | |

| Department of Transport, including the Major Transport Infrastructure Authority | 6. uses results from government pipeline modelling by the Department of Treasury and Finance and its Office of Projects Victoria and the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions to understand its workforce forecasts for the transport sector and revises its forecasts to make the differences between absolute and relative shortages clear (see Section 2.6). | Accepted by: Department of Transport |

Addressing resource shortages and risks

The audited agencies are acting to address resource shortages and risks. However, except for DJPR’s planning for extractive materials shortages, they have been slow to coordinate and deliver this work following the government pipeline’s rapid growth since 2016.

This delayed response poses risks to delivering the government pipeline within the intended timeframes, budgets and quality standards, particularly for the biggest and most complex projects.

Sequencing projects across the pipeline

In 2015, DTF advised the government of the need to strategically schedule major projects both within the government pipeline and with other states and territories to help reduce competition for resources.

In 2019, DTF advised the government that separate investment decisions for individual projects across the pipeline has led to ‘un-strategic scheduling’. This has exacerbated shortages and risks, rather than helping to reduce them.

DTF has committed to working with agencies to manage peaks in construction activity. Despite this, DTF and OPV do not advise the government or delivery agencies on project timing and sequencing options to help alleviate shortages and risks when projects compete for resources. DoT and MTIA do not do this for the transport pipeline either.

Planning strategies and actions to build capability and capacity

Collectively, the audited agencies have six key strategies underway or in draft to respond to the resource shortages and risks they have identified across the government and transport pipelines. Figure A lists these strategies and the resourcing aspects that they address. Appendix D contains information on the strategy actions and IDC members.

Figure A: Agencies’ key strategies to address delivery capability and capacity needs

| Agency | Strategy | Year | Resourcing aspects focused on | |||

| Public sector workforce | Industry workforce | Construction market | Building materials | |||

|

OPV |

Major Infrastructure Capability and Capacity Strategy (major infrastructure strategy) |

2017 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/a |

|

DTF |

Optimising Victoria’s Infrastructure Investment reform strategy (investment reform strategy) |

2019 |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | N/a |

|

Skills for Major Projects IDC strategy (Skills IDC strategy)(a) |

2020 |

N/a | ✓ | N/a | N/a | |

|

DJPR |

Helping Victoria Grow: Extractive Resources Strategy (extractives strategy) |

2018 |

N/a | N/a | N/a | ✓ |

|

MTIA |

Industry Workforce Strategy (draft) |

2020 |

N/a | ✓ | N/a | N/a |

|

DoT |

Spoil Management Strategy IDC Spoil Management Strategy (draft) |

2020 |

N/a | N/a | N/a | ✓ |

Note: N/a denotes not applicable.

Note: (a)DTF jointly led the Skills IDC strategy with DET.

Source: VAGO.

The audited agencies can also deliver actions outside of their strategies. For example, MTIA delivers additional actions for industry skills, such as supporting the Victorian Tunnelling Centre and the MetroHub training centre for the Metro Tunnel Project. For this audit, we focused on assessing the actions that agencies are delivering through the six key strategies.

Content in agencies' strategies

Except for DJPR, the audited agencies cannot consistently show that their strategies:

- target the causes of shortages and risks

- prioritise which causes to address

- have a clear rationale that supports the actions they select.

For example, OPV knows there is a risk that Victoria does not have enough skilled public sector leaders to deliver the government pipeline. However, it does not know if this is because there are not enough leadership development, recruitment and retention programs across departments and delivery agencies or because the existing programs do not work, or both.

DTF does not have a transparent rationale for how it prioritised shortages and risks and selected actions to mitigate them in its 2019 investment reform strategy. This means it is not clear if its strategy addresses the highest priority issues and its actions are the best ways to address risks.

MTIA could not show us how it uses its knowledge of workforce shortages and their causes to determine what size its training programs need to be.

Coordinating strategies and actions

The audited agencies do not effectively coordinate with each other to fully address capability and capacity risks across the government and transport pipelines.

In 2015 and 2016, DTF, OPV, MTIA and DJPR identified that concurrent, expanding infrastructure pipelines across Australia’s east coast were triggering intense competition for human and material resources. DTF and MTIA’s reviews at that time recommended that departments and agencies coordinate their work to help make the resources needed to deliver the government pipeline available.

Introduced by the Victorian Government in 2016, the Major Projects Skills Guarantee requires construction projects valued at $20 million or more to use Victorian apprentices, trainees and cadets for at least 10 per cent of total estimated labour hours. It is now included as part of Victoria's Local Jobs First Policy.

The audited agencies took several steps in response, including:

- establishing OPV in 2016

- introducing the Major Projects Skills Guarantee in 2016

- commencing OPV's major infrastructure strategy in 2017

- joining New South Wales (NSW) and the industry to form the NSW–Victoria Construction Industry Leadership Forum in 2017.

In 2015, DJPR established its Extractives Strategy Taskforce (which was then called the Extractive Industries Taskforce) and started assessing supply and demand for extractive resources.

However, DTF and OPV did not begin major efforts to coordinate their approaches until late 2018. By then, Victoria’s average annual government infrastructure investment had almost doubled. DoT and MTIA made little progress in coordinating planning across the transport sector until 2020.

The audited agencies have formed eight state-based committees, including both formal committees and taskforce arrangements, to coordinate their actions since 2015. This started with DJPR’s Extractives Strategy Taskforce in 2015. DTF, OPV, DoT and MTIA formed the other seven committees from 2017, although they did not establish two of these until 2019 and the final two until 2020.

Only four of the eight committees have delivered at least some of the coordinated actions they committed to under their terms of reference. Three of the four had an action plan to identify tasks and monitor their progress, which was central to their success.

The audited agencies have all responded quickly to collaboratively assess and address the impact of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on planning and delivering major projects.

Engaging with the construction industry

DTF and OPV do not have an engagement strategy to guide and communicate how departments and agencies will work with the construction industry to deliver the government pipeline. Despite this, DTF, OPV, MTIA and DJPR do engage with the industry and have actions underway or planned to build the industry's capability and capacity. For example, DTF, OPV and MTIA have been members of the NSW Victoria Construction Industry Leadership Forum since they joined with industry representatives and their NSW counterparts to form it in 2017.

The Local Jobs First Commissioner advocates for local industries and checks if agencies and contractors comply with the local content and job commitments they make in government infrastructure contracts.

While valuable, much of this work is not specific to the government pipeline, does not include all major projects or is specific to individual projects. DTF, OPV, DoT and MTIA also do not regularly consult on whole-of-pipeline resourcing with Victoria’s Local Jobs First Commissioner or with the local, smaller suppliers that support the pipeline's delivery.

These gaps in whole-of-pipeline engagement limit the audited agencies’ ability to:

- understand delivery risks to the government pipeline

- identify emerging issues

- prioritise and plan which issues need a government response

- keep the industry informed about their work.

While OPV has recognised the need for an industry engagement strategy since 2018, it has not introduced one. In December 2019, MTIA and DTF advised the government that they would develop a state engagement strategy. They did not set a timeline for completing this work and advised us that their work is on hold while their response to the COVID-19 pandemic takes precedence.

Planning for the public sector workforce

DTF and OPV have cross-agency actions underway to build the public sector workforce’s capability. These actions include training programs that OPV introduced in 2018 and 2019 to develop project leadership and commercial skills, such as contract management. While DoT and MTIA do not coordinate their actions to build workforce capability across public sector transport agencies, MTIA’s five project offices each have actions underway to build their workforce's capability.

DTF, OPV and MTIA have not reviewed how well their actions are addressing the capability shortages and risks that DTF and MTIA identified in 2016 and 2017, despite recognising the need to do this. For example, OPV has been responsible to the Treasurer since 2017 for ensuring the public sector has access to the skills it needs to deliver the expanding government pipeline. It does not have the data and monitoring required to provide this assurance.

DTF, OPV, DoT and MTIA’s lack of coordination and planning reduces their ability to identify capability shortages and risks. It also limits their ability to efficiently align their actions to build the public sector's capability with the separate work that other departments and delivery agencies do.

Coordinating resources for the transport sector

As the portfolio department for the transport sector, DoT, with support from MTIA, advises the government on the need for new transport infrastructure, including options and timing for delivering projects.

DoT’s business cases do not accurately advise the government on the feasibility of its recommended options, timeframes and costs for new projects. This is because DoT does not know the cumulative resourcing impacts of new projects and projects underway across the entire transport pipeline.

DoT does not have consolidated information about all aspects of delivery capability and capacity across the transport pipeline. DoT advised us that it is not funded to produce or consolidate this information, and its focus is on individual projects’ scopes and costs. It instead relies on construction firms to secure the necessary resources required to deliver the projects.

Individual transport agencies deliver actions to build capability and capacity, such as assessing the market’s capacity and developing project leaders in the public sector. However, they do not use a strategic sector-wide approach to coordinate and align this work. Our 2021 Integrated Transport Planning audit found that DoT is yet to establish an integrated approach to transport investment that is informed by relevant plans.

This leaves the government exposed to a range of risks across the pipeline, such as the risks that:

- there will not be enough suitable firms available or willing to deliver the work

- competition for stretched resources will lead to increased construction costs or delays

- transport agencies do not have the experience and skills needed to develop, procure and oversee the projects.

DoT and MTIA have started work to fill some gaps in their knowledge of the resources needed across the sector and started work on coordinated actions to build capability and capacity. However, their work is still draft. In 2020:

- DoT convened the Spoil IDC, and with the other departments and agencies, drafted the Spoil Management Strategy to respond to the identified risk of shortage of disposal sites for contaminated soil from major projects.

- MTIA drafted its Industry Workforce Strategy to support the industry workforce needed to deliver the transport pipeline.

Monitoring building materials and equipment needs

None of the audited agencies or their committees monitor supply and demand for the main materials or equipment needed for the government pipeline, such as steel, extractive resources and options for managing contaminated spoil. As a result, they cannot identify and prioritise any emerging issues in material and equipment supply and advise the government of any significant risks. DJPR engaged with DoT and MTIA in 2020 and 2021 to get data on the transport pipeline’s demand for extractive materials. It is jointly planning with MTIA to survey the construction industry contractors involved in transport major projects.

Delivering strategies and actions

Across their six strategies, the audited agencies have over 80 actions underway to help support or build delivery capability and capacity in the four resourcing aspects that we audited. They have made variable progress in delivering these actions. Their need to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the audited agencies' progress during 2020.

DTF has completed two-thirds and OPV less than a quarter of the actions they committed to in their respective 2019 and 2017 strategies, even though none of the actions had completion dates later than December 2019. While DTF has started all 11 of the actions in its 2019 investment reform strategy, OPV has still not started three of the 11 actions under its major infrastructure strategy, which aim to help plan and build the public sector workforce and broaden market participation in major projects.

DTF and other departments jointly completed three of the five actions that the Skills IDC’s strategy was able to deliver. They could not complete two actions or start the sixth action due to their additional work responding to the pandemic.

DoT’s 2020 draft spoil management strategy and MTIA’s 2020 draft Industry Workforce Strategy are still not finalised.

DTF, OPV, DoT and MTIA's lack of detailed planning for how to deliver their projects has contributed to delayed progress in delivering their strategies and actions.

DJPR is largely on track to deliver its 2018 extractives strategy by 2023. This includes significant progress to address its actions and recommendations from the Commissioner for Better Regulation’s 2017 report Getting the Groundwork Right: Better regulation of mines and quarries. Despite this, DJPR did not complete these actions by June 2020 as planned.

Delaying these actions presents a risk to the government pipeline’s successful delivery.

Measuring the impact of strategies and actions

None of the audited agencies have the performance measures, indicators and targets needed to show if their efforts are reducing capability and capacity shortages and risks as intended.

DTF, OPV, DoT and MTIA also do not assess if their capability and capacity strategies and actions help departments, other transport agencies and contractors to successfully deliver major projects within their planned scopes, costs and timelines.

The agencies’ failure to measure the impact of their capability and capacity strategies and actions also increases the risk that they are wasting resources, effort and time.

Recommendations about addressing resource shortages and risks

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Treasury and Finance, including the Office of Projects Victoria | 7. use aggregated information on Victoria’s ability to deliver the government pipeline to inform their decisions and advice to the government on the state Budget and infrastructure investments, including:

|

Accepted by: Department of Treasury and Finance |

| 8. make the aggregated information on resource shortages and risks available to departments and delivery agencies to inform their decisions and advice to the government about major infrastructure investments and actions needed to build and support resources (see sections 2.1 and 3.4) | Accepted by: Department of Treasury and Finance |

|

9. engage regularly with the construction and associated industries about the resources needed to deliver the government pipeline by:

|

Accepted by: Department of Treasury and Finance |

|

| Department of Transport | 10. leads coordinated planning to assess and manage delivery capability and capacity risks for the transport sector (see sections 2.1, 3.3 and 3.4) | Accepted by: Department of Transport |

| Department of Treasury and Finance, including the Office of Projects Victoria Department of Transport, including the Major Transport Infrastructure Authority Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions |

11. coordinate, deliver and complete their strategies, actions and the committee work they lead by:

|

Accepted by: Department Department Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions |

1. Audit context

Victoria's annual infrastructure investment is four times higher than it was in 2015–16, and other states are also boosting their investment in major projects.

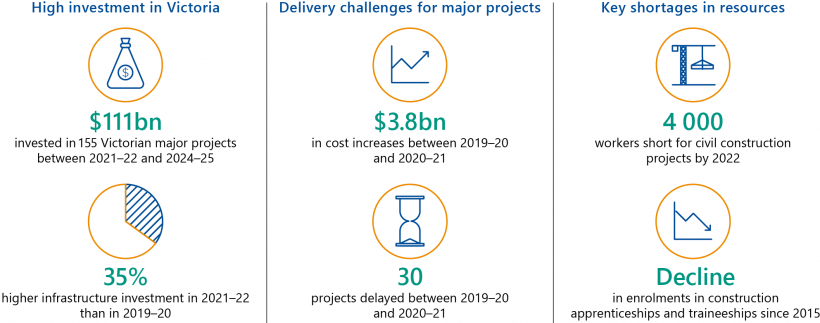

Victoria's 2021–22 state Budget noted that the state has $144 billion of new and existing projects funded and underway, up 35 per cent from the 2019–20 state Budget. Of these, $111 billion are major projects. This has led to pressure on the market’s capacity and shortages in skills and resources, which makes it harder for the government to deliver projects on time and on budget.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 Major projects in Victoria

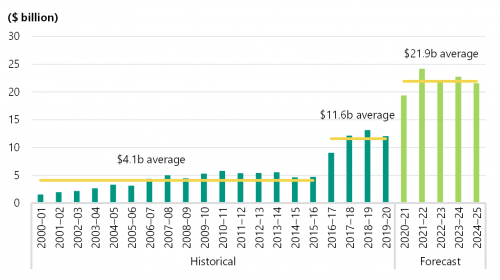

As Figure 1A shows, the Victorian Government’s annual spending on infrastructure has grown significantly since 2016. The 2021–22 state Budget forecast that this spending will average $21.9 billion a year between 2020–21 and 2024–25.

FIGURE 1A: Victoria's infrastructure investment

Source: VAGO, using DTF data.

Most of this spending is on major projects, and an increasing proportion is on megaprojects, which we define as projects that cost over $2 billion. Victoria's leading megaprojects are:

- North East Link Project ($15.4 billion total estimated investment)

- Level Crossing Removal Project (LXRP) ($13.3 billion)

- Metro Tunnel Project ($12.3 billion)

- West Gate Tunnel Project ($6.3 billion).

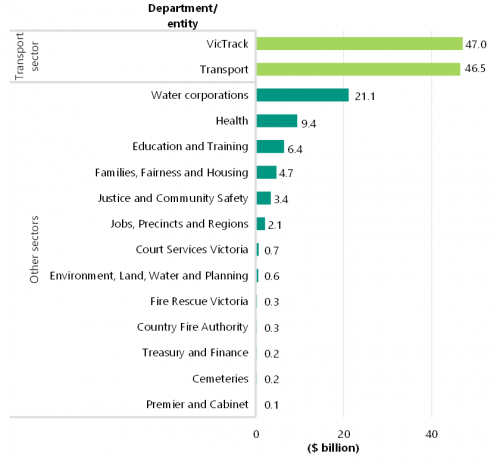

In addition to these, the government is planning new major projects and megaprojects, including Melbourne Airport Rail, Geelong Fast Rail and Suburban Rail Loop. As Figure 1B shows, most government infrastructure spending is on transport projects, which is why our audit focuses on this sector.

FIGURE 1B: Victorian Government infrastructure program by department/entity, 2021–22

Note: Only includes departments/entities with infrastructure programs valued at around $100 million or more.

Source: VAGO, using DTF data.

1.2 National infrastructure demand

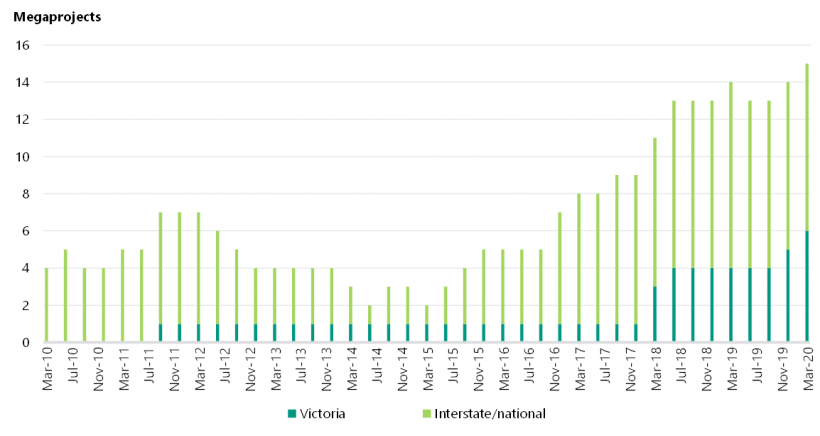

Government investment in major projects has grown significantly across Australia since 2016. Figure 1C shows the nationwide growth in megaprojects since 2010. All of these projects are transport projects.

FIGURE 1C: National growth of megaprojects under construction

Source: VAGO, based on The rise of megaprojects: counting the costs, Grattan Institute, 2020, using Grattan Institute data.

This boom in infrastructure spending across Australia is increasing the demand for contractors to deliver the projects and the materials needed to build them. This has led to shortages in labour and materials. In the 2021–22 state Budget papers, DTF noted that the costs for 117 major projects had a net increase of 4 per cent or $3.8 billion between 2019–20 and 2021–22, while 30 projects were delayed.

Cost overruns

As projects become larger, cost overruns also become larger. In its November 2020 report, The rise of megaprojects: counting the costs, the Grattan Institute found that since 2001, more than a third of cost overruns on major projects across Australia came from just seven projects. It also found that projects estimated to cost over $1 billion have an average cost overrun of at least another $1 billion. Since 2015, the average nationwide road or rail project has doubled in value to $1.1 billion.

1.3 Capability and capacity shortages

Construction market

Tier 1 construction firms predominantly lead megaprojects because they have the required people, experience and finances. Multiple tier 1 firms usually form a consortium to deliver the more complex and higher-value megaprojects. They also typically join with, or subcontract parts of the work to, smaller tier 2 or tier 3 firms.

Australia has three tier 1 firms—CPB Contractors, John Holland Group and Acciona—but has more tier 2, tier 3 and smaller firms. Infrastructure Australia advised us that its research shows that the number of tier 1 and tier 2 firms has stayed stable over the last 10 years and is not keeping pace with the growth in demand.

The infrastructure boom is stretching the domestic market’s capacity to deliver projects. Infrastructure Australia’s Australian Infrastructure Audit 2019 reported that some larger firms are also less willing to take on megaprojects because of the greater risks and in some cases, financial losses, that accompany the increasing size and complexity of these projects.

As a result, some major projects face a lack of market interest. Infrastructure Australia and other industry analysts have reported that nationwide, some megaprojects have received just one response to an expression of interest or had to be repackaged and re-tendered to attract a greater range of bidders.

Industry workforce

About 40 000 Victorians work in civil construction. As the number of major projects has increased, the demand for skilled workers and managers has exceeded supply. In early 2020, the Victorian Skills Commissioner estimated that the sector will need an additional 4 000 workers by 2022. They also forecast that the rail construction sector, which currently employs up to 7000 Victorians, will need up to 800 more workers by 2022.

The Victorian Skills Commissioner and MTIA have reported the following jobs as critically needed:

|

The civil construction sector needs more … |

The rail construction sector needs more … |

|

|

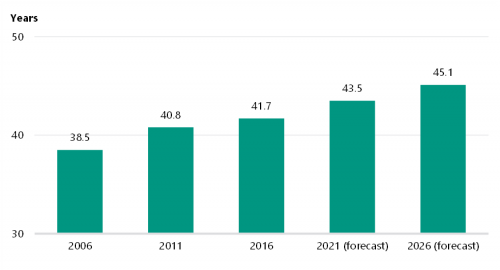

As Figure 1D shows, general shortages may worsen because the average age of the Victorian infrastructure workforce is rising and there are fewer new workers entering the industry.

For example, the Victorian Skills Commissioner found that in the rail construction sector, the need for signal technicians is critical because the current gap of around 60 workers is likely to worsen due to an ageing workforce leaving the sector.

FIGURE 1D: Average age of the Victorian infrastructure workforce

Source: MTIA, based on data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Skills training

Labour hire involves contracting workers to a specific project for a set period of time.

The Victorian Skills Commissioner reported that despite an increase in the civil construction workforce of 71 per cent between 2015 and 2018, training enrolments declined by 73 per cent. Employers noted that this is due to increased use of labour hire and financial incentives for completing work, which provides work-based experience rather than qualifications. The Victorian Skills Commissioner noted that as businesses continue to prefer labour hire rather than developing the skills of their own workforce, this increases their dependence on subcontractors and competition for skilled labour, which may intensify skill shortages.

Our 2021 report Results of 2020 Audits: Technical and Further Education Institutes found that commencements across all government-funded TAFE courses were volatile in 2019 and 2020. Commencements increased in 2019 in response to the government’s Free TAFE program but then decreased in 2020 due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Free TAFE covers tuition costs for eligible students studying priority courses determined by the government.

Public sector workforce

While the industry workforce builds the government’s major projects, the public sector plans and oversees them. A public sector team for a major infrastructure project typically has:

- project leaders, who lead, plan, direct and control the project through its life cycle

- technical staff, such as specialist engineers and statutory planners

- commercial and legal staff, who manage procurement processes and contracts

- project managers, who deliver the project according to its plan and schedule.

In its Australian Infrastructure Audit 2019, Infrastructure Australia identified that the competitive construction market is straining the public sector’s capability and capacity to deliver major projects in larger cities. It found that this poses risks to government agencies’ ability to identify the best way to deliver a project, select the right contractors for the job and oversee the contractors’ progress.

There is no publicly available information on Victorian Government departments and delivery agencies’ capability and capacity to deliver the pipeline.

Materials

In addition to skilled labour and public sector capability, major projects need physical resources. This includes heavy equipment, such as tunnel boring machines; extractive materials, such as hard rock, gravel and sand; and landfill space. For example, a lack of existing landfill capacity to dispose of soil from tunnel boring has contributed to delays on the West Gate Tunnel megaproject.

Extractive materials

According to a study commissioned by DJPR in 2016 titled Extractive Resources in Victoria: Demand and Supply Study 2015–2050, demand for extractive materials in Victoria is expected to reach almost 90 million tonnes by 2050, which is more than double the demand in 2015. Transport, energy and utilities projects are expected to make up 30 per cent of the demand for extractive materials in 2050, up from 22 per cent in 2015.

The 2016 study also found that in 2026, the supply of extractives would fall short of what the estimated demand would be and by 2050, the state would have exhausted many quarries and rock types. DJPR estimated that by 2050, 34 per cent of extractive resources would have to be sourced from new quarries.

Major projects typically source extractive resources from quarries close to their site to save on transport costs. As most major projects are in metropolitan Melbourne and the inner regions, quarries near these areas will be exhausted first.

1.4 Agencies’ responsibilities

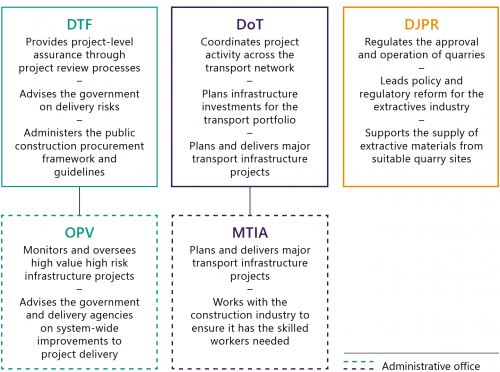

We audited three departments that have responsibilities for major infrastructure project capability and capacity, which Figure 1E summarises. We also focused on the administrative offices within DTF and DoT that have primary responsibilities in this area.

FIGURE 1E: Departments with key responsibilities for major infrastructure project capability and capacity and their relevant administrative offices

Source: VAGO.

MTIA, which is DoT’s delivery agency, formed in January 2019. It comprises the Office of the Director-General and five project offices that manage some of Victoria's largest megaprojects. The project offices are:

- North East Link Project

- LXRP

- West Gate Tunnel Project

- Rail Projects Victoria

- Major Road Projects Victoria.

DoT and DJPR also formed in January 2019. Our audit discusses the audited agencies' actions since 2015, which was when DoT and DJPR were both part of the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources. Prior to 2019, MTIA’s six offices were also part of that department. We refer to these agencies by their current names throughout this report.

While other government departments and agencies have roles in supporting skills development and training, including DET, we did not include them in this audit because their focus is not specific to the government’s major infrastructure projects.

1.5 Actions to improve capability and capacity

In October 2015, Parliament created Infrastructure Victoria and tasked it with drafting a 30-year infrastructure strategy for the state, which it did in December 2016. However, the strategy does not identify actions to address skills or other capability and capacity shortages that impact the government pipeline.

The government created OPV in September 2016 to support major project delivery. The government has also started new initiatives to attract people to the construction industry, including the Free TAFE program that DET oversees. This program, which began in 2019, includes five apprenticeship pathways and 10 courses in construction related qualifications. In addition, the government began the Major Project Skills Guarantee in 2016, which requires construction projects valued at $20 million or more to use Victorian apprentices, trainees and cadets for at least 10 per cent of total estimated labour hours. Now included under the Local Jobs First Policy, this initiative has created employment for nearly 4 000 apprentices.

The 2020–21 state Budget funded the Big Build Apprenticeships training pathway. This aims to expand employment and training opportunities for apprentices and trainees on major infrastructure projects. DET established its Apprenticeships Victoria division in 2020–21 to coordinate the new pathway in partnership with major project employers and the TAFE and training system.

On 1 July 2021 the government established the Victorian Skills Authority. This new entity aims to ensure Victoria has enough workers with the right skills to meet demand. It will engage with relevant industries to develop an annual skills plan, to better guide training delivery in the state.

The audited agencies have taken numerous actions to address capability and capacity risks, including many actions in partnership with the construction and extractives industries.

As the sector responsible for managing most major projects, the transport sector has some substantial programs underway. For example, MTIA introduced the Victorian Tunnelling Centre in partnership with Holmesglen, a TAFE provider, to meet tunnelling skill needs for the Metro Tunnel Project. This centre has the capacity to train 5 000 students each year. Over time, MTIA also intends the centre will support the skills needed for the West Gate Tunnel, North East Link and the planned Suburban Rail Loop.

In addition to the Victorian Tunnelling Centre, MTIA and its agencies have many other programs to support industry jobs, including:

- seven programs to support skills development

- seven programs to help attract talented employees

- nine programs to support social procurement targets.

This audit considered agencies’ strategic and coordinated planning to assess and address capability and capacity risks, as detailed in chapters 2 and 3. We did not assess the effectiveness of individual programs that directly train and deploy workers or build capability and capacity in other ways.

2. Assessing resource shortages and risks

Conclusion

DTF, OPV, DoT, MTIA and DJPR have assessed the human and material resources needed to deliver the government's pipeline of major infrastructure projects. However, their assessments are not complete or accurate due to limitations and data gaps in the models they use. While all agencies can address many of their limitations―and OPV and DJPR have work underway to do this―significant gaps remain.

These gaps mean that the agencies’ advice to the government about resource related risks to delivering major projects on time and on budget is not comprehensive or complete. This introduces risks about the reliability of the agencies' advice because they have not fully disclosed the gaps to the government.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Overview of shortages and risks

Each audited agency has identified shortages and risks across different resourcing aspects of the government and transport pipelines. Figure 2A highlights the key shortages they have identified.

FIGURE 2A: Audited agencies’ knowledge of resource shortages and risks

| Key aspect | Agency and year of most recent assessment | Identified shortage and risks | Size and timing of shortages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industry workforce | DTF (2020) with DET, OPV and the Skills IDC | 17 skills at the highest risk of shortage, including construction managers, plumbers and engineering production workers | Not determined |

| MTIA (2020)(a) | Shortages between 2022 and 2025 in:

|

Not determined, except for a shortage of 2 000 engineers between 2022 and 2025 | |

| Public sector workforce | DTF (2016) | Shortages in:

|

Not determined |

| Construction market | DTF, OPV and MTIA(a) (2020) | Risk that there will not be enough local tier 1 construction firms to lead major project consortiums | Not determined |

| Materials: extractive resources | DJPR(b) (2016) | DJPR forecast in 2016 that without new quarries, there would be a shortage of quarry products used in construction, such as rock, gravel and sand. Its separate supply and demand assessments in 2019 and 2020 showed changes since 2016, but DJPR does not yet know if any shortages are now likely | Average potential shortage across all extractive materials:

|

| Materials: contaminated spoil | DoT (2020) | Shortage of sites capable of re-using, treating or disposing of contaminated spoil from major projects | Not determined |

Note: (a)Shortages identified by MTIA are for the transport pipeline only.

(b)Shortages identified by DJPR for extractive materials were for all private and public construction. DJPR estimated that in 2015 the government pipeline's demand for extractive materials was around 20 per cent of the total demand across all construction.

Source: VAGO.

As Figure 2A shows, DJPR forecast the size and timing of shortages for extractive resources in 2016. It is now updating these forecasts.

Figure 2A also shows that gaps in DTF, OPV and MTIA’s workforce assessments mean they cannot readily identify the size and timing of predicted shortages. Without this information, these agencies cannot give the government accurate and comprehensive advice about the urgency of any workforce shortages and prioritise actions to address them.

In addition to these assessments, DTF, OPV, DoT and MTIA identify workforce and materials shortages and risks for individual projects, particularly when they are developing the business case for a new project. However, the focus of this work is only at the individual project level and does not consider the impact of other projects that may compete for the same resources. This means they do not know the true extent of workforce shortages for the government pipeline.

2.2 Industry workforce shortages

DTF, OPV and MTIA have identified widespread industry workforce shortages for the government and transport pipelines. However, their analyses about these shortages lack specific quantitative information about the timing of shortages, how big they will be and which occupations are likely to be affected. As a result, the agencies do not know the size and the timing of the shortages they have identified.

Through the Skills IDC in 2020, DTF, OPV and DJPR identified 17 vocational education and training (VET) related occupations that have the highest risk of immediate shortage across the government pipeline following the COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on the construction industry. These shortages include four occupations that employ high volumes of workers: plumbers, construction managers, structural steel and welder trades, and painters.

While the Skills IDC did not identify how many workers are lacking, it estimated that over 1 200 construction managers would be needed for 17 major projects due to start in 2020 and 2021. It also identified that 6 100 to 8 000 carpenters and joiners needed to be trained in 2020 to meet the current demand for these roles across the pipeline.

To identify the risk of immediate shortages, DTF, OPV and DJPR used available supply and demand data to identify and rank the construction occupations that have the highest risk of shortages. The Skills IDC was planning to do a detailed analysis to determine the size of the skills gaps. However, it could not complete this due to the way that the pandemic disrupted employment in some occupations.

Instead, the Skills IDC modified its approach to focus on how COVID-19 is expected to impact the supply and demand for particular occupations and its resulting risk of workforce shortages. This was a 'point in time' assessment and did not also evaluate the medium or longer-term risks of shortages related to the expanding government pipeline. This makes it difficult to determine the full extent of future shortages.

OPV’s workforce demand forecasts informed the Skills IDC’s work. However, its forecasts do not contain enough data about:

- the annual variation in project costs and staffing to enable OPV to model peaks and troughs in workforce demand over a project’s life

- past staffing for some sectors and occupation profiles for all sectors to accurately predict future workforce needs for different infrastructure types.

This reduces OPV’s ability to forecast demand across all phases of a project and limits its ability to assess workforce demand across different infrastructure types.

Transport sector

MTIA’s 2019 and 2020 capability assessments of the industry workforce included both supply and demand for major transport infrastructure projects. Stakeholders from the construction industry advised MTIA that they are confident the industry can deliver the pipeline in the short term. However, MTIA’s assessments indicate that shortages driven by strong demand for both high and medium-skilled occupations are likely to emerge by 2025.

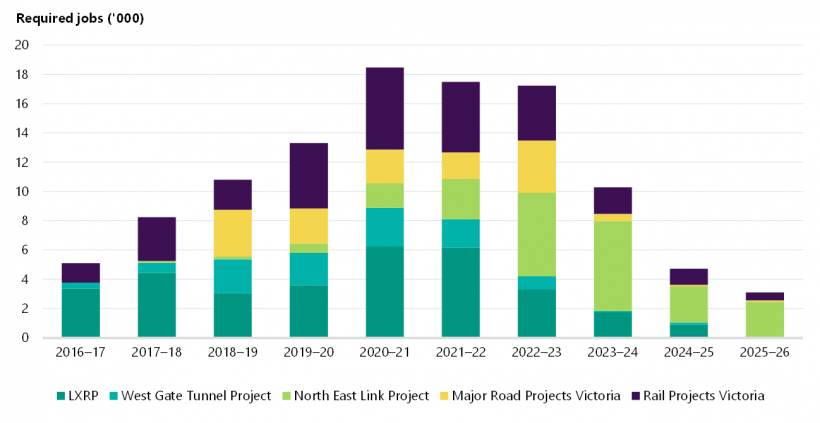

As Figure 2B shows, MTIA estimated in its 2020 assessment that the average number of construction jobs needed for major transport projects would more than double from around 8 000 in 2017–18 to over 18 000 from 2020–21 and remain high until 2022–23. We note that these forecasts are based on knowledge at the time of the assessment and do not include new projects, such as the Suburban Rail Loop.

FIGURE 2B: Forecast industry workforce demand across projects being delivered by MTIA's project offices for 2016–2017 to 2025–2026

Source: MTIA.

MTIA’s assessments also found that the following five occupations will make up 36 per cent of all roles needed during the construction peak:

- civil engineers

- plant operators

- construction managers

- labourers

- architects.

MTIA's assessments demonstrate declining numbers of apprentices in training and university enrolments in civil engineering. This means that the supply of these occupations is unlikely to keep up with demand.

As Figure 2A shows, while MTIA’s assessments quantified shortages for engineering professions, they did not provide information about:

- the skills that will be in shortest supply

- the size or timing of shortages in specific occupations.

Instead, MTIA's recent assessments only report the proportion of shortages across groups of occupations and not the number of workers needed. For example, it found there will be shortages in 68 per cent of civil construction occupations.

MTIA’s 2020 industry workforce assessment noted that a lack of data on the total size of the Victorian construction workforce and the lack of detail in the ANZSCO workforce data meant it could not pinpoint specific occupation shortages. For example, occupations such as tunnelling engineer or road constructor either have no ANZSCO classification or the classification only reflects part of what the specific occupation does. This means that MTIA does not have a clear picture of the supply and demand for specific critical roles in the transport sector.

2.3 Public sector workforce shortages

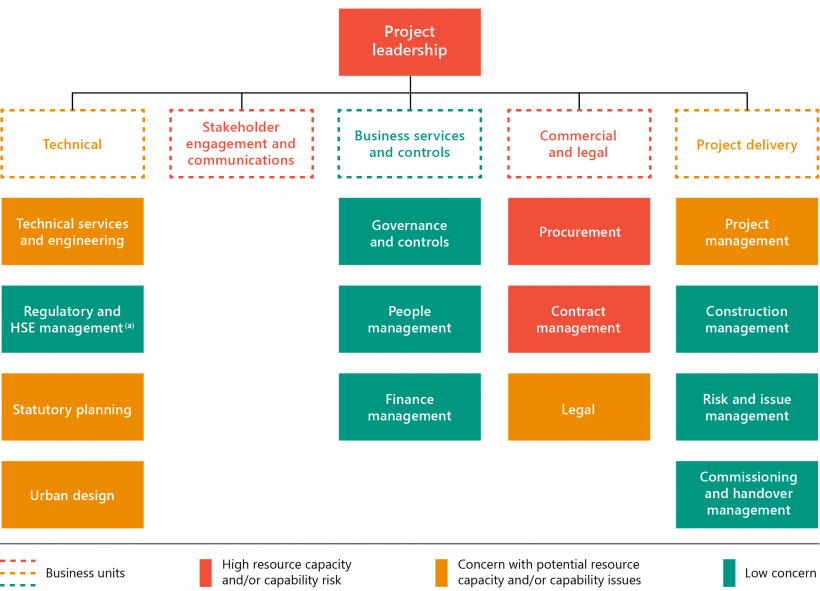

DTF’s most recent assessment of whole-of-pipeline public sector shortages was in 2016. As Figure 2C shows, this review identified project leadership, commercial and legal expertise and stakeholder communication skills as key high-risk capability gaps across Victorian Government departments and delivery agencies.

FIGURE 2C: Risks for public sector workforce capacity and capability skill areas identified by DTF in 2016

Note: (a)HSE stands for health, safety and environment.

Source: VAGO, based on DTF.

DTF based the findings from this review on department and delivery agencies’ self assessments of their capacity to respond to the government pipeline. The lack of objective, quantifiable data means that DTF does not know the actual size and timing of public sector capability gaps across the pipeline.

DTF and OPV have not followed up on the 2016 analysis to quantify the size of public sector shortages at a statewide level. Public sector data captured by the Victorian Public Sector Commission does not reveal specific project occupations, and DTF and OPV do not collect this information from agencies to analyse public sector capability and capacity. This is despite the government’s annual infrastructure investment more than doubling from $9.1 billion in 2016–17 to a forecast $24.2 billion in 2021–22. While the public sector workforce is a smaller component of major projects than the industry workforce, it is still critical to ensuring projects are scoped, procured and managed well.

DTF classifies major infrastructure projects and major information and communications technology projects as HVHR investments if:

- DTF’s risk assessment process rates them as high risk

- the Victorian Government decides they warrant the rigour applied to HVHR investments.

MTIA analysed workforce planning and capability gaps in transport agencies in 2017. However, it advised us that it did not consider this assessment to be reliable because the forecasted shortages did not align with its in-house observations about workforce changes. MTIA and DoT have not made any further attempts to assess or aggregate their knowledge of public sector capability in the transport sector since 2017.

2.4 Construction market risks

Since 2015, DTF, OPV and MTIA have regularly identified market capacity constraints as a risk to delivering major projects, particularly megaprojects. The main risk they identify is that there will not be enough contractors available with the size, experience, financial backing and risk appetite to deliver the government pipeline. This can lead to contractors charging more for their services due to reduced competition, or there being no firms available to bid for new projects.

Tier 1 firms

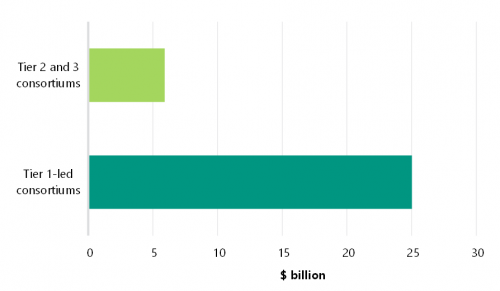

DTF, OPV and MTIA have identified that tier 1 firms’ existing commitments may limit their ability to take on more major projects. For example, in 2020, OPV identified that four tier 1-led consortiums were delivering over 75 per cent of high value high risk (HVHR) projects by value, which Figure 2D shows. This is up from 69 per cent in 2019.

FIGURE 2D: Value of Victorian HVHR projects by contractor type, 2020

Source: VAGO, using OPV data.

OPV has also identified that the tier 1 firms delivering the major projects face the greatest delivery challenges. For example, for one tier 1 firm, almost two thirds of the work it is delivering, as measured by value, faces significant delivery risk. This is primarily through the firm's involvement in two high-value megaprojects.

Tier 2 and tier 3 firms

DTF, OPV and MTIA have highlighted concerns that there not enough tier 2 and tier 3 firms participating in major projects. This is because:

- there is a lack of certainty about what projects will become part of the government pipeline

- the large size of many major project tenders.

These issues are limiting tier 2 and 3 firms’ involvement in major projects at a time when greater participation could reduce the reliance on tier 1 firms.

Infrastructure Australia advised us that its research shows that the number of tier 1 and 2 firms, which has stayed stable over the last 10 years, has been far outpaced by the growth in demand.

International firms

DTF, OPV and MTIA have also determined that allowing international firms to participate in major projects can help overcome the shortage of local tier 1 firms. International firms are part of the consortiums delivering some of Victoria’s biggest projects, such as the Metro Tunnel Project. However, recent analysis from the Grattan Institute’s 2021 Megabang for megabucks: Driving a harder bargain on megaprojects report shows that NSW has been more successful at this than Victoria. Since 2006, 28 per cent of NSW’s transport contracts worth $1 billion or more have involved international participants, compared to 11 per cent in Victoria.

Data

DTF, OPV, DoT and MTIA do not collate data on the number of tier 2, tier 3 and international firms that could participate in delivering the government and transport pipelines. They also do not know if participation by these types of firms is changing over time and how significant or urgent the risk of decreasing participation is.

These agencies' market assessments focus on identifying firms available to participate in individual projects or types of projects, such as MTIA's assessments for road projects.

While DTF collects data about the market’s capacity, it does not use it to assess capacity to deliver the pipeline or monitor participation. In some cases, this is because the data is incomplete. For example:

2.5 Building material shortages

Extractive materials

DJPR's 2016 forecasts indicated that there was enough extractive material in the ground to meet future demand. However, DJPR also estimated that the costs of extracting and supplying the material would rise over time as available materials in existing quarries become depleted and new quarries are established further away from construction locations. DJPR forecast that without new or expanded quarries, supply shortages would arise by 2026 and become more acute over time. For example:

- in 2026, based on existing and planned quarry locations, the average supply shortfall of extractive materials as a proportion of demand would be 13 per cent, growing to 30 per cent by 2050

- by 2050, 34 per cent of demand would need to be sourced from quarries not built or planned in 2018.

Key changes since 2016 mean that these forecasts are likely to be outdated. For example:

- DJPR has been working to support supply and mitigate the risk of shortages in the short and long term through its 2018 extractives strategy, as we discuss in Section 3.5

- the government pipeline has expanded significantly, which is likely boosting demand for the extractive materials needed to build roads, tunnels and other infrastructure.

DJPR updated its demand forecasts in 2019, which showed that demand was 20 per cent higher than its 2016 baseline forecasts. Its 2020 supply data shows that the annual volume of extractive materials produced by quarries increased approximately 25 per cent between 2014–15 and 2019–20.

Limitations in DJPR's data and modelling mean it cannot identify:

- the root cause of any supply and demand imbalances and when they are likely to occur

- potential actions the government could take to minimise the risk of shortages disrupting the government pipeline's delivery.

DJPR is working on its planned five-yearly update of the supply and demand forecasts. It is due to report on its updated forecasts in the second half of 2022. However, it currently lacks accurate data for its new forecasts, related to:

- the capacity that existing and planned quarries have to supply materials

- the demand from the government pipeline.

DJPR is aware that incomplete and unreliable data limits the accuracy of its forecast shortages. It is working to improve the quality of its data on quarry capacity, demand from the government pipeline and the costs of transporting extractive materials.

Quarry capacity

Individual quarries have data on how much extractive materials they supply, where they supply it to and how much remains in their reserves. The construction firms delivering major projects have data on how much extractive materials their projects use and where the materials come from. DJPR has difficulty accessing this data because quarries and firms keep it confidential. This impedes DJPR’s ability to accurately forecast the volume of materials firms need to deliver major projects.

DJPR has introduced new regulations that require quarries to annually report on their available resources by stone type from July 2021. This is important because as DJPR has acknowledged, the lack of regulation in the industry on this type of reporting has limited its ability to respond to demands and prevent shortages.

Demand from the government pipeline

DJPR, OPV, DoT and MTIA do not all regularly share information on the pipeline and individual projects’ supply and demand for extractive materials. DJPR engaged with DoT and MTIA in 2020 and 2021 to source this information and is jointly planning with MTIA to survey the construction industry contractors involved in transport major projects.

DJPR does not assess the supply and demand for extractive materials for the government or transport pipelines, which make up around a third of the state’s demand for extractive resources, separately from other non-government demand. This means that while DJPR can advise the government about overall demand risks, it cannot specifically advise where the demand comes from or how to best respond to it.

Cost of transporting extractive materials

As existing quarries become depleted and it becomes necessary to source materials from more distant quarries, the cost of some materials will go up. For example, in 2016 DJPR estimated that for every additional 25 kilometres materials have to travel, an extra $2 billion in extractive transport costs would be incurred across the government pipeline between 2015 and 2050.

However, DJPR has not yet been able to quantify how much the costs per tonne will progressively rise as more material is supplied to the market. This is a critical gap because without this information, DJPR cannot assess if extractive material costs will exceed the budgets of major projects across the government pipeline. It has work underway to do this, which we discuss in Section 2.6.

Contaminated spoil

In leading the Spoil IDC’s work, DoT has identified that the unprecedented volume of spoil being generated across the pipeline is unsustainable. It expects that current transport infrastructure projects alone will generate almost four million tonnes of contaminated spoil. This estimate does not include upcoming projects, such as the Suburban Rail Loop.

The average volume of spoil with low levels of contamination generated annually in Victoria more than doubled from 336 000 tonnes a year in 2007 to 2017 to 707 000 tonnes in 2018 to 2019. Currently, 95 per cent of this contaminated spoil is sent to landfill.

While DoT has forecast the increasing volumes of spoil that major infrastructure projects will generate, it has not yet quantified the state’s capacity to re-use, treat or dispose of it, although it plans to do this. This means it does not know the size and timing of the related shortages it anticipates.

The new Environment Protection Regulations 2021, which started on 1 July 2021, may affect the state’s future spoil management capacity by potentially expanding opportunities to re-use low-level contaminated spoil. However, the companies that manage contaminated spoil have limited capacity to respond quickly to changing regulations because it takes time to establish new spoil sites.

2.6 Modelling resource capability and capacity

The audited agencies’ information on industry workforce and extractive material shortages comes from models that OPV, DJPR and MTIA use to forecast supply and demand. OPV, DJPR and MTIA all model demand for the industry workforce. DJPR models supply and demand for extractive materials. Figure 2E summarises the purpose of each agency's modelling activity.

FIGURE 2E: Audited agencies’ modelling activities for industry workforce and materials

| Agency | Model focus | Modelling activities |

|---|---|---|

| DJPR | Statewide employment demand |

|

| DJPR | Statewide extractive materials supply and demand |

|

| OPV | Industry workforce demand for government major projects |

|

| MTIA | Industry workforce supply and demand for the transport pipeline |

|

Source: VAGO.

We also looked at how OPV and DJPR integrate with DET's modelling when developing their forecasts. DET models VET workforce supply and demand across the state's economy to help it manage the TAFE and training system. It uses DJPR's statewide employment modelling to do this. DET does not model supply specific to the government pipeline although its supply and demand analyses include the construction industry.

DJPR and DET's models are designed to assess statewide employment. These models predate OPV's workforce forecasting for major projects.

Constraints to modelling approaches

While DJPR, OPV and MTIA's workforce models are technically reliable for their different purposes, they have not ensured the separate models also work together in an integrated way. As a result, they do not have a comprehensive understanding of the supply and demand of the industry workforce for the government pipeline. Forecasting limitations in their modelling approaches also reduce their ability to assess how the government can best address supply shortages and risks.

Integrating workforce models

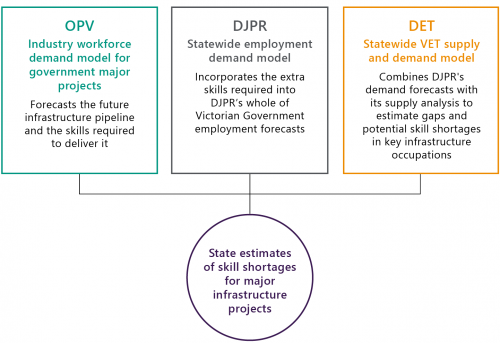

In 2020, the Skills IDC identified the need for OPV and DJPR to work with DET to integrate their models to understand supply and demand for the industry workforce needed for the government pipeline. They developed a concept for this integration, which Figure 2F shows. At that time, OPV was still developing its model.

FIGURE 2F: Concept for integrating OPV, DJPR and DET’s industry workforce capability modelling

Source: VAGO, based on information from DTF.

OPV and DJPR are working to enact the concept through better sharing and aligning the results and analysis from their existing separate models and DET's. However, OPV and DJPR do not aim to revise and integrate their models, which they need to do to provide consistent and reliable information to government about the extent of skill shortages in the labour market.

OPV and DJPR cannot integrate their models to forecast supply and demand and identify potential workforce shortages for the government pipeline because:

- they did not design their modelling approaches from the outset to work in an integrated way

- their models use different forecasting methods, assumptions and constraints and produce different outputs, which means they cannot be joined together or with DET's modelling in their current forms

- their models do not adequately consider how the Victorian labour market functions because they do not include factors that affect labour supply, such as changes to migration rules.

Additionally, MTIA has not considered how its modelling of supply and demand in the transport sector for industry workforce skills aligns with the statewide modelling that DJPR and DET do.

Without integration and alignment, OPV, DJPR and MTIA's models cannot provide accurate information about the size and timing of skill shortages that may impact major project delivery. These gaps and uncertainties mean DTF, OPV and MTIA cannot give the government reliable advice about priority shortages for the government and transport pipelines and approaches to alleviate them, such as through training, increased skilled migration and/or coordinating the timing and sequencing of projects.

Limitations of OPV and DJPR’s workforce modelling

OPV and DJPR’s workforce models have mostly achieved their original purposes, which Figure 2E outlines. However, OPV and DJPR’s models do not consider the relationships between Victoria’s labour market and other macro economic variables, such as competition from other states for workers. This means that the forecasts that these models generate are not based on all of the available information and therefore do not give a complete estimate of the government pipeline's workforce needs.

OPV and DJPR’s models also do not identify how new government policies may impact the supply of workers. This means, for example, that while the models can estimate how many workers will be needed by occupation type at a certain year, they cannot predict how a new policy to subsidise a training course may impact the supply of workers.

OPV's workforce model aims to model demand and estimate employment impacts for major infrastructure projects. However, the model has two significant limitations.

Firstly, it does not have the capacity to model demand for the entire government pipeline. The model can only do this for individual projects and groups of projects. This is a significant limitation because demand for the total pipeline is likely to rise due to supply constraints that cannot be identified and quantified by modelling individual projects or subsets. This is because as more investment is injected into the economy, multiple industry sectors start competing for workers and materials. This can change when and where shortages are likely to occur across different industry sectors.

Secondly, OPV's model cannot differentiate between ‘absolute’ and ‘relative’ shortages. This distinction is fundamental to how the government decides to address shortages:

- relative shortages can be fixed through policies and incentives that use the existing labour pool

- absolute shortages, for example, the inability of the labour market to supply enough skilled workers in the short to medium term, need different solutions, such as importing more labour from other states or overseas.

DJPR's workforce modelling does not include the distribution of skills across occupations and industries under ANZSCO. This means it only forecasts employment by industry, and not by occupations within industries. Both OPV and DJPR are aware of other models that address these limitations. They are working to improve their own modelling tools to consider these factors.

Limitations of MTIA’s workforce modelling for the transport sector

The modelling that MTIA uses to identify critical industry workforce shortages cannot differentiate between absolute and relative shortages either. Its modelling also does not consider the additional impact that forecast shortages across the whole pipeline will have for transport projects. This means that MTIA does not have all of the information it needs to plan transport infrastructure projects within the context of the wider government pipeline.

Limitations of DJPR’s extractives modelling

DJPR’s extractive materials modelling is the most developed of the audited agencies’ supply and demand models.

DJPR is now developing a new modelling approach to overcome the limitations it identified in its 2016 modelling. For example, its previous modelling approach could not distinguish between:

- absolute shortages in supply due to approved quarries becoming depleted

- relative shortages caused by constraints, such as restricted quarry operating hours or inadequate road networks for transporting quarry products.

DJPR’s new approach aims to show how different government actions and regulations could improve supply and mitigate rising cost pressures, including:

- fast-tracking approvals for quarry expansions in strategic locations

- extending operating hours for some quarries.

DJPR aims to improve its estimates of how supply costs will change over time for different major projects. However, its planning does not include enough detail for us to confirm that it will quantify how the cumulative demand for extractive materials across the government pipeline will affect the unit cost per tonne of extractive materials for individual projects.

3. Addressing resource shortages and risks

Conclusion

All audited agencies have strategies and actions that target human and material resource shortages and risks. However, many of these actions are behind schedule and agencies do not know if they are effectively reducing delivery risks to the state’s infrastructure pipeline.

Gaps in how DTF, OPV, DoT, MTIA and DJPR coordinate with each other and relevant industries on strategies and actions mean they cannot advise the government on how well they are addressing different shortages and risks or which actions to prioritise. This reduces their ability to achieve cost-effective interventions across the pipeline and avoid time and cost overruns.

This chapter discusses:

3.1 Scheduling projects

DTF’s 2015 advice to the government about establishing OPV recognised the need to strategically sequence major projects both within the government pipeline and with other states and territories to optimise delivery benefits. An MTIA review in 2017 also identified this as a gap.