Management of Unplanned Leave in Emergency services and safety

Overview

Operational staff at Ambulance Victoria (AV), the Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board (MFESB) and Victoria Police (VicPol) are more likely to suffer injuries and emotional stress, and have higher rates of unplanned leave, than other public sector staff.

AV, MFESB and VicPol have each recognised the importance of managing unplanned leave. However, there are significant differences in how effectively and efficiently they are each managing the issues.

Both AV and VicPol have been generally effective and efficient in managing unplanned leave, although AV recognises the need to reduce the personal unplanned leave levels of paramedics and other operational staff.

AV and VicPol have effective management oversight, supported by sound and practical data that enables their frontline managers to manage and support staff. They are aware of the causes of unplanned leave and have either implemented, or are developing actions to address these.

However, MFESB needs to improve considerably. Compared to its peer agencies it has the poorest unplanned leave performance. MFESB's management has been aware of the causes of personal unplanned leave since 2000 but it has not adequately addressed them. There is a lack of frontline management accountability for unplanned leave, and a lack of regular data on firefighters’ unplanned leave available to managers.

Management of Unplanned Leave in Emergency services and safety: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2013

PP No 212, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Management of Unplanned Leave in Emergency Services.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

6 March 2013

Audit summary

Background

Victoria’s public sector provides its staff with a range of leave benefits. These benefits include annual leave, parental leave and study leave, which are typically planned in advance with the employer.

Public sector staff are also provided with personal leave benefits to manage incidents such as illness, or the need to care for an ill family member. Additionally, staff injured at work have access to worker’s compensation leave. These types of leave are typically unplanned and occur unexpectedly.

All organisations experience some degree of unplanned leave which, given its nature, can create management and budgeting challenges. Unplanned leave can create significant financial costs, disrupt service delivery and compromise the achievement of organisational objectives. Attendance at work can be affected by:

- health and fitness problems

- barriers such as caring responsibilities or personal emergencies

- motivation.

Excessive unplanned leave can be a symptom of larger problems within an organisation, including poor occupational health and safety management, an unfavourable organisational culture, or insufficient controls over access to entitlements such as sick and carer’s leave. Operational staff in emergency services agencies, such as Ambulance Victoria (AV), the Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board (MFESB) and Victoria Police (VicPol) are more likely to suffer injuries and emotional stress compared to their non-operational counterparts due to their high-risk work environment.

Conclusions

Victoria’s emergency service agencies—AV, MFESB and VicPol—have each recognised the importance of managing unplanned leave. However, there are significant differences in how effectively and efficiently they are each managing the issues.

Both AV and VicPol have been generally effective and efficient in managing unplanned leave, although AV recognises the need to reduce the personal unplanned leave levels of paramedics and other operational staff. AV and VicPol have effective management oversight, supported by sound and practical data that enables their frontline managers to manage and support staff. They are aware of the causes of unplanned leave and have either implemented, or are developing actions to address these.

However, MFESB needs to improve considerably. Compared to its peer agencies it has the poorest unplanned leave performance, which has been caused by ineffective management over the past decade.

MFESB’s management has been aware of the causes of personal unplanned leave since 2000 but it has not adequately addressed them. There is a lack of frontline management accountability for unplanned leave, and a lack of regular data on firefighters’ unplanned leave for managers at the station level. This needs to be addressed as a matter of priority.

Findings

Unplanned leave performance

In 2011–12, the number of shifts lost due to unplanned leave for operational staff at AV, MFESB and VicPol was 10.6, 11.6 and 9.6 per full-time equivalent (FTE) respectively.

Long average shift durations at AV and MFESB—11.77 hours and 12 hours—result in average time lost to unplanned leave of 124.6 hours and 139.5 hours per FTE respectively. VicPol’s shorter average shift length of 7.6 hours results in time lost to unplanned leave of 72.9 hours per FTE.

The level of unplanned leave at AV reflects a slight decline compared to 2010–11. While MFESB achieved a slight reduction in 2011–12, its unplanned leave has increased steadily since 2000. Unplanned leave for VicPol has remained constant and substantially below AV and MFESB.

Senior agency management oversight

Effective management of unplanned leave relies on the commitment and oversight of senior management. Senior managers set expectations by establishing policies, practices and the responsibilities of staff and managers. Sustained management attention is required to effectively identify and address the underlying causes of unplanned leave.

Each agency’s senior management is briefed on the types and levels of unplanned leave and the contributing factors, however the nature and extent of oversight and effective action varies.

Both AV’s and MFESB’s senior management regularly consider unplanned leave. AV’s senior management receives regular information on unplanned leave and enforces responsibilities at all levels of operational management. However, MFESB’s senior management has only strengthened its oversight of unplanned leave since 2010, and this has delayed its response to the issues it faces.

VicPol conducts reviews of operational groups every six months. These reviews provide senior executives with the opportunity to examine police managers’ operational performance and request specific action, including managing unplanned leave. However, the frequency of these reviews may limit VicPol’s ability to respond to systemic unplanned leave issues in a timely way.

Industrial constraints on decision-making

MFESB and the United Firefighters’ Union (UFU) entered into an enterprise agreement for firefighters in 2010. The agreement is legally binding on MFESB and UFU. It contains provisions that constrain MFESB’s ability to effectively and efficiently implement initiatives to manage unplanned leave.

The provisions in the enterprise agreement effectively require that any change affecting MFESB’s relationship with its staff be agreed upon with UFU. This has the potential to contribute to difficulty and delay in introducing reasonable mechanisms to hold firefighters, and their managers, accountable for personal unplanned leave that is not justified by illness or injury.

Identifying the causes and impacts of unplanned leave

Identifying the causes of unplanned leave provides agency management with the information it needs to develop appropriate responses. All agencies have undertaken work to identify the causes and impacts of unplanned leave, although the extent to which this has informed management actions varies.

AV, MFESB and VicPol all regularly monitor service levels, overtime costs and unplanned leave to identify trends and patterns that may point to local causes of unplanned leave. In addition, MFESB has commissioned two reviews to gain a greater insight into the causes of personal unplanned leave.

However, only AV and VicPol have taken effective action to address the underlying causes of unplanned leave. While MFESB has had the necessary information over the past decade, it has not taken appropriate action until recently.

Frontline management practices

Effective frontline management is a key part of unplanned leave management. Frontline managers are in a position to positively influence motivation, reinforce staff understanding of their responsibilities, and deal directly with staff taking high levels of personal unplanned leave.

Frontline management of unplanned leave

Frontline management of unplanned leave is sound at both AV and VicPol, with clear responsibilities for managing personal unplanned leave, and generally consistent follow-up with staff after periods of unplanned leave.

AV faces challenges embedding good practices in rural branches where team managers are primarily allocated to paramedic duties but also have a significant number of staff to manage. The importance of enabling these managers to better manage their staff is highlighted by the rate of personal unplanned leave in AV’s rural areas, which exceeded that in metropolitan areas by 2.6 shifts per full-time operational staff member in 2011–12.

In contrast, MFESB’s commanders have primary responsibility for managing unplanned leave but do not have direct relationships with their firefighters. This limits their capacity to effectively work with firefighters to address personal unplanned leave issues. While senior station officers and station officers are in the best position to manage unplanned leave, they do not play an active role in doing so.

Accountability of frontline managers

To effectively perform the role of a frontline manager, accountability for managing unplanned leave should be clear and managers should have access to support, advice and appropriate professional development. Accountability was strongest at both AV and VicPol, and again was weakest in MFESB.

AV’s team managers have primary responsibility for managing the unplanned leave of operational staff. Line management practices include regular reviews of unplanned leave and the actions of managers to address individual cases. Managers’ performance plans and appraisals reinforce their responsibility for effectively managing unplanned leave.

VicPol places responsibility for unplanned leave with senior sergeants who manage police stations. As with AV, line management practices include regular monitoring of unplanned leave, with senior sergeants expected to closely monitor cases of high unplanned leave.

MFESB is strengthening the role of firefighter commanders for managing unplanned leave. However, MFESB has not established the means to hold commanders, senior station officers or station officers, who manage individual fire stations, accountable for the unplanned leave of their teams.

Services and guidance for frontline management

The causes of unplanned leave are complex and managing it can be equally complex. Access to robust guidance and assistance from human resource experts is essential in providing effective management responses.

Frontline managers at AV and VicPol are well supported with advice on human resource management matters and unplanned leave data. This enables managers to confidently deal with staff issues in compliance with organisational policies.

However, MFESB does not have sufficient internal human resources expertise to assist managers to confidently interpret the firefighters’ enterprise agreement and handle staff matters in MFESB’s industrial relations environment. Further, it does not provide its frontline managers with data on the unplanned leave of individual firefighters. This is a significant weakness in MFESB’s approach to managing unplanned leave.

Human resource policies and processes

Effective management of unplanned leave requires agencies having clear policies and procedures that are regularly communicated, monitored and applied. Processes and systems for managing shift work should have the ability to respond to changes in staff availability, including changes resulting from unplanned leave.

Staff responsibilities

Each agency has sound procedures for recording and approving unplanned leave. However, the extent to which these procedures are effectively implemented varies across the agencies. Ineffective implementation diminishes the purpose and value of having these controls in place, and does little to encourage staff to account for their absences, or to deter discretionary unplanned leave.

AV has generally sound procedures for reporting and recording unplanned leave. AV’s operational staff are required to contact one of two state duty managers so that unplanned leave can be recorded and replacement staff rostered. Unplanned leave is initially recorded as ‘uncertified’ and is only changed after staff submit evidence to support the absence.

MFESB has two inconsistent sources of information for firefighters on the requirements for reporting and recording unplanned leave. In addition, MFESB’s procedures for validating evidence to justify unplanned leave are unreliable. Documentary evidence supporting unplanned leave recorded as ‘certified’ was not held on MFESB’s personnel files in 23 per cent of instances involving firefighters with high levels of unplanned leave. MFESB does not apply controls to reinforce staff members’ responsibility for providing evidence in support of unplanned leave.

VicPol has a consistent approach to reporting and recording unplanned leave. VicPol policy only requires that managers sight evidence of unplanned leave, rather than retain copies of evidence. While this creates some risk of inconsistency in applying procedures, VicPol has adequate controls that compensate for this risk.

Operational resource management

AV’s systems and processes for operational resource planning and management provide the capacity for AV to reduce the factors causing unplanned leave. It has thorough processes for planning the resources it requires to deliver ambulance services. AV has centralised call-taking and dispatch, and has recently introduced a statewide rostering system that provides for the efficient deployment of ambulance resources. However, central controls over rostering, while improving the efficiency of operational staff management, have reduced the flexibility previously available to staff in rural regions. Team managers report that this contributes to unplanned leave.

MFESB and VicPol management are aware of the need to improve rostering and are taking steps to address weaknesses. VicPol’s rostering is conducted on a station‑by‑station basis with effectiveness dependent on the officer managing the roster. The lack of centralised controls over rostering and the large number of individual worksites create the risk that poor rostering contributes to unplanned leave. As part of its planned corporate actions for 2012–15 VicPol is conducting a trial of practices to improve aspects of rostering. Contingent on the outcomes of the trial, VicPol will consider wider application of the practices.

MFESB is working to improve the operational management of firefighters to reduce the costs arising from unplanned leave. However, the extent to which it is able to manage these costs is limited by a provision in the firefighters’ enterprise agreement that specifies the minimum number of firefighters required for each shift. As unplanned leave and the transfer of firefighters into training and special projects reduce the number of rostered firefighters available to work, firefighters must be recalled to work overtime in order to meet the minimum number required.

Initiatives to reduce unplanned leave

AV has been proactive in developing initiatives that address unplanned leave but has been slow to extend these initiatives to all parts of the organisation. Between 2007 and 2011, AV successfully implemented alternative arrangements that strengthened the capacity of frontline managers of large teams to lead, manage and support paramedics and other operational staff.

While AV also provided development training for managers of smaller non-metropolitan teams, comprehensive development for these team managers has been delayed until 2012–13 because of financial constraints. This delay is likely to have contributed to the difficulty of reducing the level of unplanned leave in rural areas, which remains higher than in metropolitan locations.

MFESB is also committed to developing its firefighter managers’ leadership and management skills, so as to increase firefighters’ commitment to MFESB’s strategic goals, and reduce their personal unplanned leave.

AV, MFESB and VicPol have embarked on strategies to reduce workplace injury. AV is concentrating on reducing the incidence of the two largest sources of claims—manual handling and psychological stress. Lifting equipment will be provided in 2012–13 and individual psychological plans for 1 000 operational staff are to be completed by June 2013.

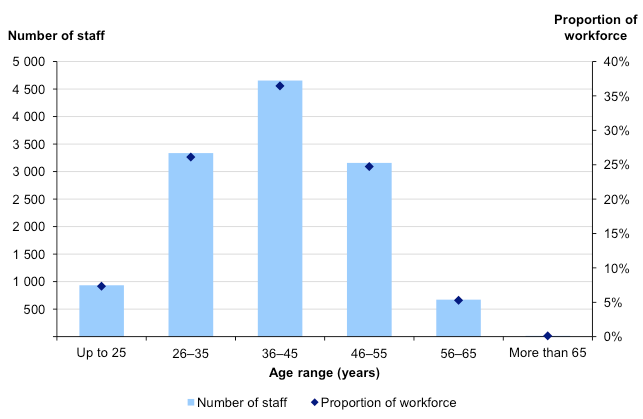

MFESB is focusing on strengthening the physical resilience of firefighters, recognising that approximately 60 per cent of its WorkCover claims result from manual handling, slips and falls. MFESB is also placing emphasis on firefighters’ health awareness as 60 per cent of its firefighters are aged over 45 years.

Similarly, VicPol has given a high priority to reducing workplace injury, with claims declining by 40 per cent between 2006–07 and 2011–12. However, psychological injuries that generally involve longer-term absences have declined at around two-thirds the rate of all workplace injury claims.

VicPol has a strategy to address these issues, part of which is the development of frontline managers whose role includes identifying and intervening when staff show indications of psychological stress, including unusual levels of unplanned leave.

Recommendations

Ambulance Victoria should:

- review support for team managers who also perform paramedic duties and implement improvements to maximise team managers’ ability to perform their roles

- review processes for managing personal unplanned leave evidence to reduce the risk that personal unplanned leave is incorrectly recorded

- closely monitor in rural regions the outcomes of its strategy to strengthen team management and adjust the strategy to address gaps or underperformance.

The Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board should:

- review the impact of its enterprise agreements on the efficiency of frontline management, and on the implementation of audit recommendations, in preparation for enterprise agreement discussions in 2013

- strengthen performance management of firefighter managers and reduce the financial disincentive to more effectively manage personal unplanned leave

- provide operational commanders, senior station officers and station officers with regularly updated information on the personal unplanned leave of firefighters in their teams

- improve specialised human resources support to frontline managers

- provide one comprehensive source of information on policies and procedures for managing personal unplanned leave

- review and strengthen controls over staff fulfilling their responsibilities for providing evidence to support personal unplanned leave

- continue to strengthen human resource management processes and controls to reduce avoidable overtime costs.

Victoria Police should:

- improve the management of police members undergoing performance and discipline procedures

- monitor the use of online tools for accessing unplanned leave data, to make sure that the tools are accessible and meet the needs of police managers

- adequately train all frontline police managers to handle complex personal matters involving staff.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to Ambulance Victoria, the Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board and Victoria Police with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Unplanned leave

Victoria’s public sector provides its staff with a range of leave benefits including annual leave, parental leave and study leave, which are typically planned in advance with the employer.

Public sector staff are also provided with personal leave benefits to manage incidents such as illness, or the need to care for an ill family member. Additionally, staff injured at work have access to worker’s compensation leave. These types of leave are typically unplanned and are unexpected.

1.1.1 Cost of unplanned leave

All organisations experience some degree of unplanned leave, which given its nature can create management and budgeting challenges. Unplanned leave can create significant financial costs, disrupt service delivery and compromise the achievement of organisational objectives. The costs to an organisation include:

- direct costs covering salaries, overtime payments, replacement staff costs and increased workers’ compensation insurance premiums

- indirect costs covering disruption to service delivery, lost productivity and adverse impacts on the physical or psychological health of other staff, particularly those who have to perform additional duties due to staff absence.

Victoria’s State Services Authority (SSA) estimates that in 2011–12 the direct cost of sick and carer’s leave was $605.9 million across the Victorian public sector.

1.1.2 Factors influencing unplanned leave

Personal—paid sick and carer’s—leave and worker’s compensation leave are the most common types of unplanned leave. Research indicates that attendance at work is affected by:

- health and fitness problems

- barriers such as caring responsibilities or personal emergencies

- motivation.

Excessive unplanned leave can be a symptom of larger problems within an organisation, including poor occupational health and safety management, an unfavourable organisational culture or insufficient controls over access to entitlements such as sick and carer’s leave. Workforces that have a higher proportion of older workers or staff with dependents are likely to have higher levels of unplanned leave.

1.2 Unplanned leave in the Victorian public sector

According to the SSA, in 2011–12 the average number of sick and carer’s leave days taken per full-time equivalent (FTE) staff across the Victorian public sector was 9.6 days, and in Victorian police and emergency services agencies, 10 days.

Operational staff in emergency services agencies, such as Ambulance Victoria (AV), the Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board (MFESB) and Victoria Police (VicPol), are more likely to suffer injuries and emotional stress compared to their non‑operational counterparts due to their high-risk work environment.

As these staff work shifts of up to 14 hours, a single absence can result in time lost being nearly double that of a standard working day of 7.6 hours. In addition, work arrangements where a minimum number of staff are required for each shift show higher levels of unplanned leave, as absences are generally filled by staff paid at overtime rates.

Figure 1A shows the average number of hours, with corresponding number of standard working days and shifts, of personal unplanned leave taken by operational staff at AV, MFESB and VicPol in 2011–12.

Figure 1A

Personal unplanned leave taken by operational staff in 2011–12

|

Agency |

Hours per FTE |

Standard working days per FTE |

Shifts per FTE |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ambulance Victoria |

124.6 |

16.4 |

10.6 |

|

Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board |

139.5 |

18.4 |

11.6 |

|

Victoria Police |

72.9 |

9.6 |

9.6 |

Note: Paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office, based on agency data.

1.3 Emergency services agencies

1.3.1 Ambulance Victoria

AV provides medical transport to hospital and emergency response and care for patients before admission to hospital. Its paramedic staff have specialised medical skills required to manage injuries and sustain life, and to operate AV’s vehicles and equipment.

AV’s ambulance operations are organised into seven regions, each of which comprises between three and four groups. Ambulance groups comprise several rostered teams of paramedics and other operational staff working from one or more branches.

Teams comprise between two and 30 staff and are managed by a team manager. In large branches team managers are dedicated to managing paramedic and other operational staff and ambulance operations. In smaller branches team managers perform paramedic duties in addition to managing staff and operations.

In 2011–12 AV had 3 448.6 full-time equivalent (FTE) staff comprising 2 854.7 operational staff, 274.5 operational support and managerial staff and 319.4 other corporate staff.

AV’s operations are divided into two Melbourne metropolitan regions and five regions covering other parts of the state. Fifty-nine per cent of AV’s operational workforce is located in Melbourne and 41 per cent in areas outside Melbourne.

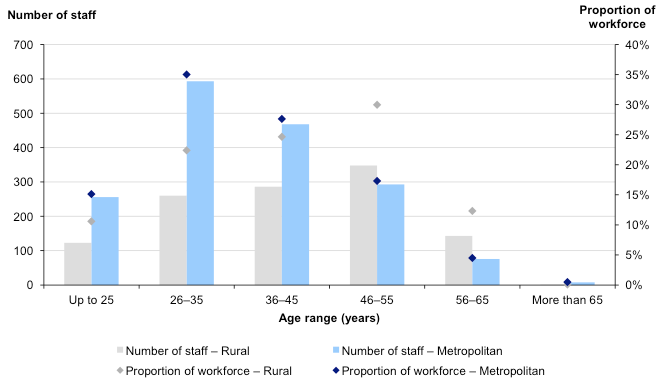

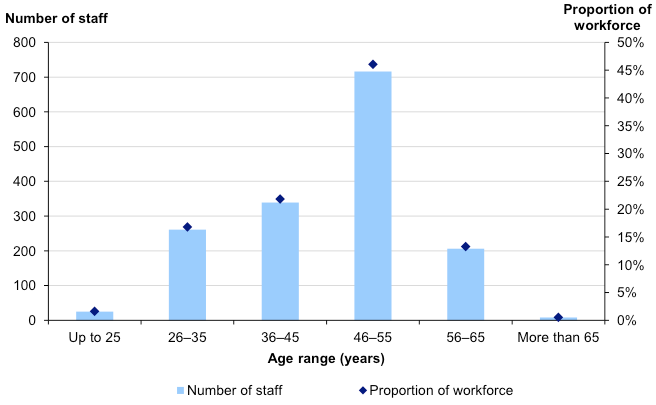

Figure 1B shows that 77.7 per cent of AV’s Melbourne metropolitan operational workforce is aged 45 years or under, while outside Melbourne the age distribution is more evenly spread, with 57.6 per cent aged 45 or under. Only 5 per cent of AV’s Melbourne workforce is aged over 55 years, compared with 12.4 per cent of its rural workforce.

Figure 1B

Ambulance Victoria operational workforce demographic profile

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Ambulance Victoria data.

1.3.2 Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board

MFESB provides fire and emergency management services, works to improve fire safety in building design, develops fire prevention programs and provides operational support to major events in Australia and Asia-Pacific nations. MFESB provides services within the metropolitan fire district as defined under the Metropolitan Fire Brigades Act 1958.

MFESB’s services are organised into two regions, comprising five districts and 47 fire stations. Firefighters are attached to a fire station and one of four platoons. One platoon is rostered for duty across all MFESB’s fire stations at any time. MFESB’s stations range in size, rostering between three and 14 firefighters per shift.

Senior station officers generally manage MFESB’s larger stations, with station officers managing smaller stations. Senior station officers’ duties include the frontline management of firefighters, while reporting to an operational commander. Commanders’ roles include coordinating firefighters across MFESB’s stations and districts, and managing attendance.

MFESB had 2 108.4 FTE staff comprising 1 804.5 operational firefighters, and 303.8 corporate and technical staff as at 30 June 2012. MFESB’s firefighter workforce is ageing, with 59.8 per cent of firefighters aged over 45 years and 40.2 per cent 45 years or under.

Figure 1C

Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board firefighter workforce demographic profile

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board data.

1.3.3 Victoria Police

VicPol provides policing services across the state. It is responsible for public safety, crime prevention, responding to petty, serious and organised crime, increasing road safety, enforcing road laws and responding to and managing incidents and emergencies.

VicPol’s general policing is organised into two metropolitan and two non-metropolitan regions. Regions are broken into divisions and police service areas. Each police service area contains one or more police stations. VicPol operates a total of 346 police stations.

Police members assigned to general policing duties are attached to a police station. Stations are managed by senior sergeants and range in size between one and 132 police members. Inspectors have responsibility for police service areas comprising a number of stations. Inspectors report to a superintendent who has responsibility for a division.

At 30 June 2012, VicPol had 15 624 FTE staff, including 12 478 sworn police members and 2 726 public servants. Sworn police members work in a range of areas including general policing, crime, intelligence and support. Of VicPol’s 12 478 sworn police members, 8 737 work in general policing units—4 619 in VicPol’s metropolitan regions and 4 118 in non-metropolitan regions.

VicPol’s sworn police comprise 70 per cent aged 45 years or under and 30 per cent over 45 years.

Figure 1D

Victoria Police sworn police workforce demographic profile

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Victoria Police data.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess whether AV, MFESB and VicPol are effectively and efficiently managing unplanned leave. To assess the objective, the audit examined whether these agencies:

- collect, analyse and report comprehensive and accurate data on leave

- oversee and manage unplanned leave in a timely and systematic manner.

WorkSafe Victoria, the Department of Health and the Department of Justice were consulted during the audit.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit was performed in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $375 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

Part 2 of the report assesses Ambulance Victoria’s management of unplanned leave, Part 3 the Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board and Part 4 Victoria Police.

2 Ambulance Victoria

At a glance

Background

Personal unplanned leave of Ambulance Victoria’s (AV) operational staff in 2011–12 was 124.6 hours per full-time equivalent (FTE); a slight reduction from an average of 130.9 hours in 2010–11. Personal unplanned leave in rural areas was 143.5 hours per FTE in 2011–12 compared to 111.3 hours in metropolitan regions.

Conclusion

AV has a sound approach to unplanned leave management. However, the level of unplanned leave is considerably higher than the average for Victorian police and emergency service agencies. Improved performance has been largely limited to metropolitan regions.

Findings

- AV maintains close oversight of personal unplanned leave and workplace injuries and understands their causes and costs.

- AV has developed systems and processes that provide operational management with the capacity to manage unplanned leave.

- AV has sound staff policies for personal unplanned leave, but its management of staff evidence of unplanned leave needs improvement.

- AV has developed and implemented evidence-based strategies to reduce unplanned leave.

Recommendations

Ambulance Victoria should:

- review support for team managers who also perform paramedic duties and implement improvements to maximise team managers’ ability to perform their roles

- review processes for managing personal unplanned leave evidence to reduce the risk that personal unplanned leave is incorrectly recorded.

2.1 Introduction

The nature of work performed by Ambulance Victoria’s (AV) paramedics and other operational staff, with long inflexible shifts, frequent manual handling and routinely stressful situations, means that this group of staff are likely to have higher rates of unplanned leave than other public sector staff.

AV’s operational staff generally work 40–42 hours each week in rostered shifts of 8–14 hours, across all days of the week and public holidays. As penalties are averaged and included in their base salaries, operational staff do not receive specific payments for working particular shifts, such as at night or weekend.

Operational staff annual leave is rostered in advance and must be taken in four-week blocks. Operational staff are not able to take additional annual leave, including single days’ annual leave, outside their rostered leave period. Operational staff are entitled to three days’ personal unplanned leave without evidence each year. Personal unplanned leave entitlements are shown in Figure 2A.

Figure 2A

Operational staff unplanned leave entitlements

|

Leave category |

Entitlement |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Paid sick and carer’s leave |

Annual entitlement |

96 hours in first year of employment 112 hours second to fourth year of employment 168 hours fifth year of employment and onwards An additional 40 hours accrues for every five‑year period where there was no uncertified single day absence during that period |

|

Uncertified allowance |

Three days without medical certificate or statutory declaration |

|

|

Other unplanned leave |

Special leave |

Subject to management approval |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Ambulance Victoria data.

2.2 Conclusion

AV has a sound approach to personal unplanned leave management. It has improved rostering and control of operational staff overtime, but it has yet to achieve reductions in personal unplanned leave.

AV has established clear policies and procedures for personal unplanned leave, and managers have clear responsibilities for monitoring and following-up staff taking high levels of unplanned leave. It has also developed initiatives to improve the capability of frontline managers to manage personal unplanned leave and to reduce workplace injuries.

However, the level of personal unplanned leave is higher than the average for Victorian police and emergency service agencies. Improved performance has been largely limited to Melbourne metropolitan regions. While AV has strengthened operational management, reduced overtime costs and reduced risks to service availability in rural regions, its strategies have yet to show reductions in unplanned leave in these areas.

2.3 Unplanned leave performance

The absence of an operational staff member for a single shift results in a loss of between 8 and 14 hours, compared with the time lost in one standard working day of 7.6 hours.

While AV collects a range of performance data around its personal unplanned leave, it does not currently use a benchmark for management comparisons. It is in the process of developing a benchmark based on leave per full-time equivalent (FTE) staff.

2.3.1 Time lost due to unplanned leave

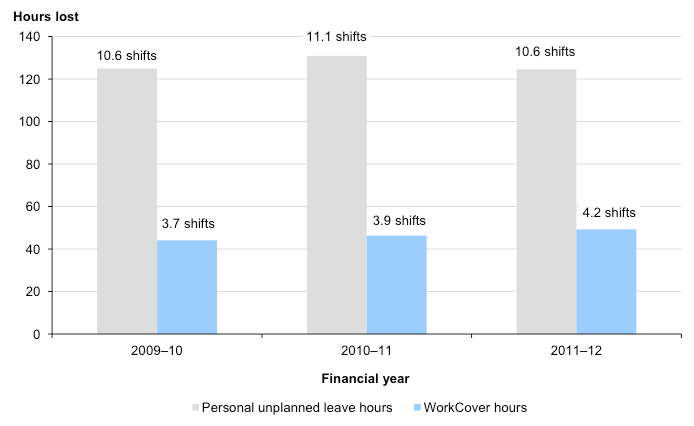

Time lost due to operational staff personal unplanned leave remained steady over the period 2009–10 to 2011–12.

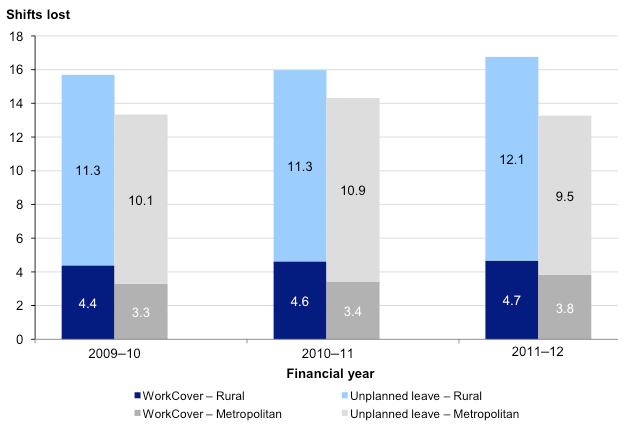

Figure 2B shows that operational staff time lost due to personal unplanned leave averaged 124.6 hours per FTE in 2011–12, a slight reduction from the average of 130.9 hours per FTE in 2010–11 but back to the levels of 2009–10. Operational staff average personal unplanned leave of 124.6 hours per FTE in 2011–12 is equivalent to 10.6 shifts per FTE.

Operational staff time lost due to workplace injuries shows an increase from 44.1 hours per FTE in 2009–10 to 49.2 hours per FTE in 2011–12, equivalent to 4.2 shifts.

Figure 2B

Average time and shifts lost due to unplanned leave per FTE operational staff member

Note: Personal unplanned leave includes paid sick and carer’s leave only. Ambulance Victoria data only available for 2009–10 to 2011–12.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Ambulance Victoria data.

Figure 2C shows AV’s operational and non-operational staff time lost due to personal unplanned leave was 120.2 hours per FTE in 2011–12. This is significantly above the average for operational and non-operational staff in Victorian police and emergency services agencies of 76.0 hours per FTE in 2011–12.

AV’s average time lost for all operational and non-operational staff is also considerably higher than South Australia Ambulance Service (65.4 sick and carer’s leave, including unpaid)—the only other state ambulance service regularly providing public performance information. In 2010–11, Queensland Ambulance Service’s[1] unplanned leave for operational and non-operational staff, including personal and workers’ compensation leave, was 89.7 hours per FTE.

[1]Managing employee unplanned absence, Queensland Audit Office, June 2012

Figure 2C

Lost time due to unplanned leave in ambulance services and the public sector, 2011–12

|

Agency |

Leave types |

Hours |

Standard working days |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ambulance Victoria operational staff |

Sick and carer’s |

124.6 |

16.4 |

|

Ambulance service organisations(a) |

|||

|

Sick and carer’s |

120.2 |

15.8 |

|

Sick and carer’s, including unpaid |

65.4 |

8.6 |

|

Victorian public sector(a)(b) |

|||

|

Sick and carer’s |

76.0 |

10.0 |

|

Sick and carer’s |

73.0 |

9.6 |

(a) Includes operational and non-operational staff.

(b) Excludes staff not employed for the whole year.

Note: Includes paid leave only unless otherwise noted. Standard working days represents time lost not actual number of absences, for example Ambulance Victoria’s average working day is 11.77 hours for operational staff.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Victorian State Services Authority data and South Australian Public Sector Workforce Information, June 2012.

2.3.2 Characteristics of unplanned leave

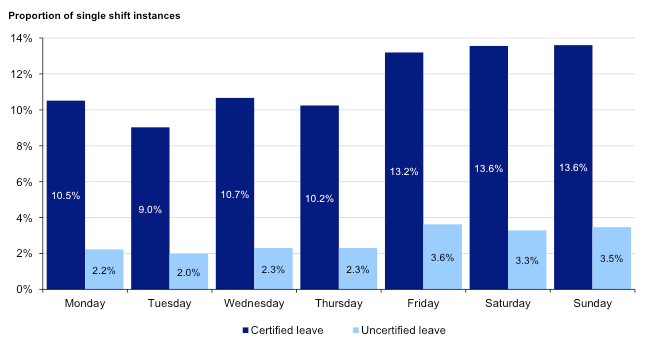

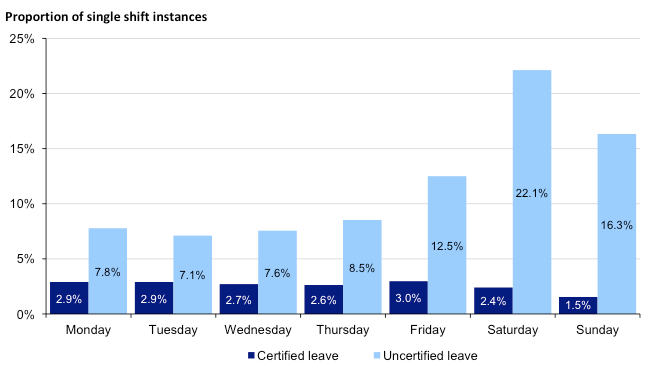

Figure 2D shows that operational staff take single shifts of personal unplanned leave at a higher rate on weekends than on weekdays. In 2011–12, between 16.8 and 17.1 per cent of all single shift absences occurred on each of Friday, Saturday and Sunday compared with 11 to 13 per cent between Monday and Thursday.

Figure 2D

Single shift personal unplanned leave by day of the week, 2011–12

Note: Includes paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Ambulance Victoria data.

Certified leave is used by operational staff at approximately three times the rate of uncertified leave. While operational staff are entitled to three days’ personal unplanned leave without evidence, they are able to provide statutory declarations in support of unplanned leave, as an alternative to medical certificates.

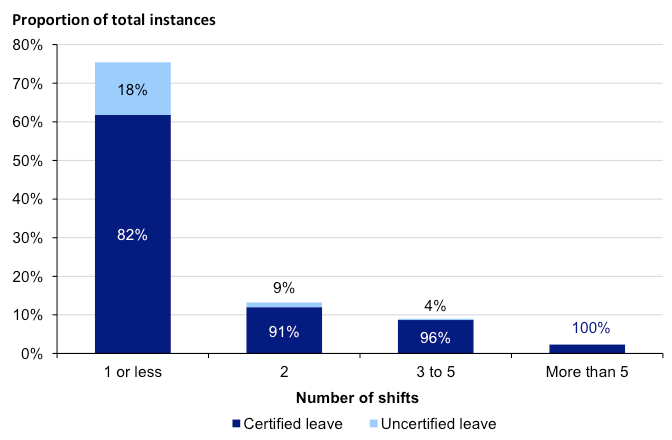

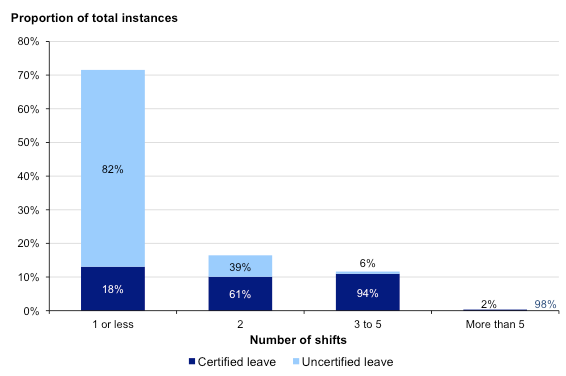

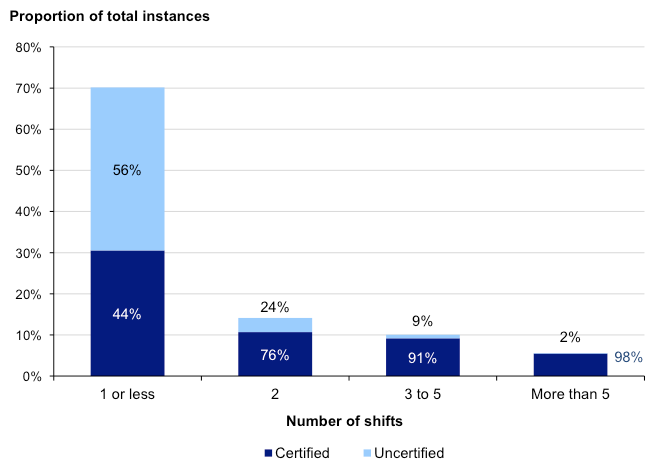

Figure 2E shows that single shift unplanned leave comprises up to 75 per cent of the unplanned absences of operational staff. Of these instances, 82 per cent are supported with medical evidence or statutory declaration.

Figure 2E

Breakdown of personal unplanned leave by length of absence and whether supported by evidence, 2011–12

Note: Includes paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Ambulance Victoria data.

Unplanned leave of operational staff in AV’s rural regions has recently exceeded unplanned leave in AV’s metropolitan regions.

Figure 2F shows that in 2011–12, operational staff in AV’s rural regions took 12.1 shifts per FTE personal unplanned leave compared to 9.5 shifts per FTE in metropolitan regions. Personal unplanned leave in rural and metropolitan regions was similar in 2009–10 and 2010–11.

In 2011–12, WorkCover leave was also higher in AV’s rural regions at 4.7 shifts per FTE compared with 3.8 shifts per FTE in metropolitan regions. Since 2009–10 WorkCover leave in rural regions has been approximately one shift per FTE higher than in metropolitan regions.

Figure 2F

Unplanned leave shifts per FTE operational staff member in rural and metropolitan regions, 2011–12

Note: Includes paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Ambulance Victoria data.

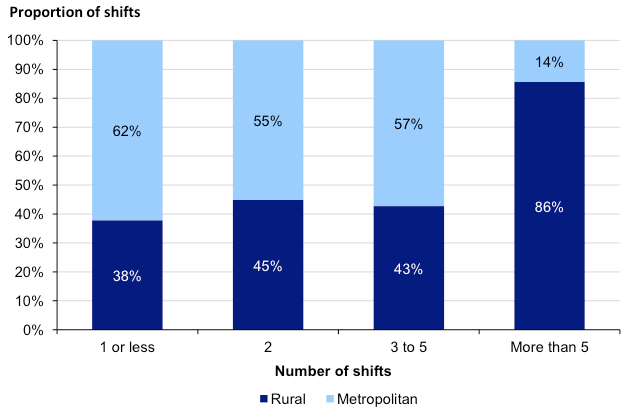

Figure 2G shows that operational staff in rural regions take long periods of personal unplanned leave at a far greater rate than those located in metropolitan regions. While comprising 41 per cent of AV’s operational staff, paramedics and other operational staff in rural regions took 86 per cent of AV’s personal unplanned leave periods of five or more consecutive shifts.

This is consistent with Figure 1B, which shows AV’s rural regions have considerably more operational staff aged over 45 than its metropolitan regions, and with AV’s analysis that indicates its older workers experience higher rates of illness and injury.

Figure 2G also shows that the rate at which operational staff take shorter periods of personal unplanned leave is similar in metropolitan and rural regions. Operational staff in metropolitan regions take 62 per cent of single shift unplanned leave and comprise 59 per cent of AV’s operational workforce. This indicates effective management of single shift personal unplanned leave is equally important in AV’s metropolitan and rural regions.

Figure 2G

Breakdown of unplanned leave by number of shifts and region, 2011–12

Note: Includes paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Ambulance Victoria data.

2.4 Oversight and monitoring

AV maintains close oversight of unplanned leave, including the operational and strategic factors that cause high levels of unplanned leave.

2.4.1 Senior management oversight

AV’s board receives monthly reports of sick leave, workplace injury, overtime and WorkCover costs, and information on the handling of emerging issues. This allows the board to monitor the management of resources and the effectiveness of strategies to reduce unplanned leave.

AV’s senior managers, with responsibility for operations and central services, regularly monitor levels and trends in unplanned leave. Senior managers closely monitor initiatives to reduce personal unplanned leave as part of their management of wider improvement strategies. AV’s approach recognises the role of both operational and service groups in managing unplanned leave.

2.4.2 Identifying the causes and impacts of unplanned leave

AV has a thorough approach to identifying and analysing the causes of unplanned leave and developing solutions. It undertakes detailed analyses of personal unplanned leave, workplace injury, rosters and the attitudes and demographic characteristics of its workforce.

AV has identified that unplanned leave is influenced by:

- fatigue that arises from factors including night shifts being extended due to service demands, or operational staff accepting high overtime hours

- morale issues due to the inflexibility of rosters, high workloads and a perceived lack of operational support

- serious illness and injury, particularly among older workers.

AV effectively monitors the costs and impacts of unplanned leave. It separately reports overtime arising as a result of unplanned leave, and monitors the number of shift positions that are not staffed and result in reduced services. AV’s monitoring of workplace injury enables it to identify the major types of injury, their costs and the priorities for prevention.

In 2011–12, AV has developed initiatives to reduce manual handling and psychological injuries. Manual handling comprised 66 per cent of WorkCover claims, and 56 per cent of costs, and psychological injury comprised 14 per cent of claims, and 29 per cent of costs.

AV has a systematic approach to developing and evaluating initiatives. It has conducted pilot projects and evaluations of team management, the use of equipment to reduce workplace injury and a program to increase operational staff ability to manage workplace stress. AV’s approach provides detailed information about the issues and the effectiveness of proposed solutions before significant resources are committed.

AV also regularly brings together senior managers with responsibilities for operations and operational services, people, education, planning, research and evaluation to consider operational performance issues, including unplanned leave. Involving managers from across functions provides the basis for AV to fully appreciate the causes of unplanned leave and its impacts.

2.5 Frontline management of unplanned leave

AV’s approach to managing the personal unplanned leave of operational staff is sound. We found that team managers and group managers are undertaking the actions required to effectively manage operational staff personal unplanned leave.

2.5.1 Frontline management of operational staff

AV’s team managers have direct responsibility for managing operational staff including personal unplanned leave, WorkCover and performance management. Managers of large AV branches may have responsibility for up to 40 operational staff. Managers of smaller teams continue to perform paramedic duties and have limited time for team management duties.

AV’s team managers are required to speak with staff returning from personal unplanned leave and those taking high levels of unplanned leave. We found team managers are generally fulfilling these responsibilities and that their regular contact helps them identify and manage issues that may prevent operational staff from attending work.

In cases of high levels of unplanned leave, we found that team managers’ conversations with staff lead to improved performance. However, some team managers in rural regions who also perform paramedic duties have more difficulty maintaining contact with staff within the time allocated for management duties.

In the case of staff repeatedly taking uncertified personal leave, team managers or group managers are responsible for informally discussing this with the staff member. This generally results in changed behaviour where the leave taking is discretionary. AV has in place, but avoids the use of, formal performance management procedures unless a staff member has used all entitlements. In the case of staff suffering long-term illness or injury, AV’s preferred approach is to provide alternative duties applicable to the staff member’s work capacity, or to support them to seek employment outside AV.

2.5.2 Accountability of frontline managers

AV effectively enforces operational managers’ accountability for managing unplanned leave.

Team managers’ performance goals require them to effectively manage personal unplanned leave and constructively engage with staff. Effective management of personal leave requires that managers maintain positive and supportive, yet firm, relationships with their staff.

Group managers have responsibility for a number of operational teams. Group managers’ performance goals focus on their responsibility for implementing AV’s strategies to reduce workplace injury, reduce risks to psychological health, and improve fatigue management.

Regular meetings of senior and mid-level operational managers are informed by personal unplanned leave data, including levels and trends for all AV’s regions and groups. Financial reports include the actual cost of sick leave and overtime. An emphasis on unplanned leave at senior levels reinforces the attention given by operational managers to the unplanned leave of their teams.

2.5.3 Services and guidance for frontline management

Data on unplanned leave

AV supports frontline managers to manage unplanned leave by regularly providing them with data on the personal unplanned leave of staff in their teams.

Team managers in AV’s large branches receive daily emails listing the staff on personal leave. This is required as shift patterns prevent team managers from having constant contact with their teams. Group managers and team managers of large branches also receive monthly reports including the identity of the staff member, date and type of the unplanned leave, and the staff member’s recent history of unplanned leave. Staff history of personal unplanned leave may show patterns that indicate personal or health issues.

We found that team managers of large branches and their group managers receive and actively monitor monthly leave data, and follow up with staff. Team managers in some smaller branches, who perform paramedic duties in addition to team management, are less well supported. We found that these team managers have less capacity to monitor their staff. However, AV will soon commence providing unplanned leave data directly to team managers in rural regions. This will help rural team managers more effectively manage the unplanned leave of operational staff in their teams.

AV should continue to monitor the support for team managers who also perform paramedic duties to maximise their ability to perform their management roles.

Support and development for frontline managers

AV’s team managers are well supported with specialised advice on human resource management. In 2011, AV restructured its central human resources unit to improve services to operational managers. Regular contact with human resources specialists enables managers to confidently deal with staff issues in compliance with organisational policies.

AV has committed to providing training to its operational team managers in 2012–13. AV’s training will draw on its experience in developing the management capability of team managers over the period 2007 to 2011. The training will also reflect AV’s increasing emphasis on team managers’ responsibility for monitoring the welfare of operational staff and responding proactively to indicators of psychological stress. Effective monitoring and management of staff welfare plays a key role in reducing unplanned leave and psychological injury.

2.6 Human resource policies and processes

2.6.1 Staff responsibilities

AV has comprehensive policies for personal unplanned leave that are clearly communicated to staff and provide the basis for effective management of unplanned leave. They provide staff with clear guidance on AV’s expectations and the responsibilities of staff and managers for unplanned absences.

Operational staff taking personal unplanned leave are required to contact one of two state duty managers who record the absence and request the rostering of alternate staff. When staff return from leave, team managers are required to check on their welfare and discuss any issues that may be contributing to personal unplanned leave. These procedures provide sound control over the recording of absences, so that managers regularly monitor operational staff welfare, and reinforce staff members’ understanding of their responsibilities.

AV’s systems are configured to initially record personal unplanned leave as uncertified, with the status changed once the staff member provides medical evidence or a statutory declaration in support of the leave. This reinforces staff responsibility for providing the required evidence.

AV’s controls over staff responsibilities provide confidence that their responsibilities are adequately met. However, we found that evidence of unplanned leave was not present in 20 per cent of cases in a small sample of personnel files and leave instances. The absence of staff evidence in personnel files indicates there is a risk that personal leave recorded as certified may be incorrectly recorded. AV should review its processes for managing evidence to reduce the risk that personal unplanned leave is incorrectly recorded.

2.6.2 Operational human resource management

AV’s systems and processes for operational resource management provide the capacity to effectively manage AV’s workforce of paramedic and other operational staff and minimise the factors causing unplanned leave. However, AV needs to continually monitor and improve resource management to reduce the impact of unplanned leave on service delivery.

AV has a comprehensive approach to workforce planning. Annual planning takes account of historic demand for services, levels of unplanned leave and staff turnover to calculate the mix of operational staff and overtime resources, and new staff recruitment required in each operating area. AV schedules training and annual leave each year, allocating replacement staff or overtime to meet service requirements.

AV is steadily improving the rostering of operational staff. Annual leave is rostered in four-week blocks to maintain staffing and service levels. AV provides for operational staff to accrue time and request time off to meet personal needs. Staff are required to provide seven days’ notice and AV only grants requests for time off where service requirements allow. However, team managers report that inflexibility of rostering leads to some operational staff using unplanned leave to meet personal needs.

In June 2012, AV completed implementation of a rostering system that will allow paramedic groups to have additional control of their rosters, within statewide rostering policies. AV expects that an increase in local control over rosters would reduce any personal unplanned leave caused by current limitations in roster flexibility, particularly in rural areas.

AV has reduced the number of call-taking and dispatch centres from six to two, over the past three years. This provides the basis for AV to strengthen control over ambulance resources, including managing unplanned absences and the deployment of operational staff.

2.7 Initiatives to reduce unplanned leave

2.7.1 Developing frontline managers

AV has committed significant resources over several years to developing the role and capability of its frontline managers. In 2012–13, AV will extend a consistent program of management development to its team managers in all regions.

From 2006, the Metropolitan Ambulance Service and Rural Ambulance Victoria implemented measures to improve the capacity of team managers to effectively lead, manage and support operational staff. After amalgamation in July 2008, AV continued these measures, which involved trialling expanded roles, the development of metropolitan team managers and development training involving 90 rural team managers.

Differences between the structure of AV’s operations in metropolitan and rural regions have prevented AV adopting a common approach to developing team managers. In AV’s large metropolitan branches its team managers devote the majority of their time to managing staff and operations. This has allowed AV to progressively shift team managers into expanded management roles, with a period of intensive support and mentoring during the transition. In branches with a small number of operational staff, AV is unable to relieve team managers of paramedic duties while maintaining service levels. This has limited the options for developing team managers in small branches located outside metropolitan areas.

AV has now recognised the need to develop a single approach to team managers’ roles to reduce the differences between metropolitan and rural regions, and between ambulance and other AV services. As a result, and due to financial constraints, AV ceased further restructuring of metropolitan team manager roles in early 2011. AV has now developed a single framework for the role requirements of team managers. This provides the basis for the professional development that AV hopes to commence in 2013.

AV expects to have a program in early 2013 for managers in all regions that can be delivered in a financially sustainable fashion. The program is based on a common role structure and covers the management of performance, staff welfare, health and safety, and leave management.

AV has committed significant effort to developing its frontline managers. However, there is a risk that delays in providing comprehensive development to team managers outside Melbourne, many of whom continue on shift rosters, has increased the difficulty in dealing with the long-standing factors causing higher levels of unplanned leave in rural regions.

2.7.2 Reducing workplace injury

AV is implementing soundly-based strategies in 2012–13 to reduce the risk of manual handling and psychological injuries, which together resulted in 80 per cent of AV’s WorkCover claims in 2011–12, and 85 per cent of the estimated total cost of these claims.

Measures to reduce manual handling injuries are based on the results of a pilot program conducted in 2011 that found new equipment and work methods would reduce operational staff risk of injury. AV has recognised that uptake will depend on effective communication and training, and is addressing these requirements during implementation. Lifting and other manual activity resulted in 66 per cent of AV’s WorkCover claims and 56 per cent of the estimated total cost of claims in 2011–12.

AV is reducing the risk of operational staff suffering psychological injury by complementing its psychological services with assistance to help staff more actively manage their own stress and fatigue.

In 2011, AV trialled a program to provide operational staff with a personal welfare plan based on a voluntary psychological assessment. The trial responded to two internal audits conducted in 2010 that identified the need for a more integrated approach to managing psychological risks to operational staff. The trial identified a number of staff at high risk of psychological injury and assisted them to seek appropriate assistance. A majority of operational staff involved in the trial valued the assistance they received in better managing stress and fatigue.

Based on the results of the trial, AV will provide stress and fatigue assessments and personal welfare planning for 1 000 operational staff by June 2013. Psychological injury is the most costly form of workplace injury, and can result in staff being absent from work for considerable periods. Psychological injuries are the cause of 14 per cent of AV’s WorkCover claims and 29 per cent of the estimated total cost of claims in 2011–12.

Recommendations

Ambulance Victoria should:

- review support for team managers who also perform paramedic duties and implement improvements to maximise team managers’ ability to perform their roles

- review processes for managing personal unplanned leave evidence to reduce the risk that personal unplanned leave is incorrectly recorded

- closely monitor in rural regions the outcomes of its strategy to strengthen team management and adjust the strategy to address gaps or underperformance.

3 Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board

At a glance

Background

Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board (MFESB) firefighters’ time lost due to personal unplanned leave in 2011–12 was 139.5 hours per full-time equivalent (FTE); similar to the average of 136.4 hours per FTE, per year, over the period 2006–07 to 2011–12. This represents a slight reduction in 2011–12. Unplanned leave is significantly higher on weekends than weekdays.

Conclusion

Firefighters’ time lost due to personal unplanned leave has steadily increased since 2000. MFESB’s enterprise agreement with firefighters constrains management decisions. MFESB’s systems and processes are also inefficient and contribute to the costs of unplanned leave.

Findings

- Senior management has been aware since 2000 of the major causes of high levels of personal unplanned leave but has not taken effective action until recently.

- Management decisions concerning staff can only be implemented with agreement of the union.

- Operational managers are not held accountable for personal unplanned leave and are not adequately supported to manage unplanned leave.

- There are weaknesses in the control of resources, information for firefighters on the requirements for personal unplanned leave, and controls over the provision of evidence for personal unplanned leave.

Recommendations

The Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board should:

- review the impact of its enterprise agreements on the efficiency of frontline management, and on the implementation of audit recommendations, in preparation for enterprise agreement discussions in 2013

- strengthen performance management of firefighter managers and reduce the financial disincentive to more effectively manage personal unplanned leave.

3.1 Introduction

Firefighters’ work entails long, inflexible shifts and periods of intense activity in hazardous situations with a high potential for injury. These factors are likely to result in this group of staff having higher rates of unplanned leave than other public sector staff.

The Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board’s (MFESB) firefighters work two 10-hour day shifts and two 14-hour night shifts and then have four days off. Weekends and public holidays are included in the eight-day cycle.

They receive specific penalty and overtime payments in addition to their base pay, with overtime paid at double the rate of base pay. Firefighters are required to take their entitlement of 65.06 days recreation leave in blocks of 28 days at the same time each year, but are able to take single days of annual or long-service leave at short notice.

Firefighters are also entitled to eight days unplanned leave without evidence each year. Their unplanned leave entitlements are shown in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A

Firefighters’ unplanned leave entitlements

|

Leave category |

Entitlement |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Paid sick and carer’s leave |

Annual entitlement |

144 hours |

|

Uncertified allowance |

Eight days consisting of:

|

|

|

Other unplanned leave |

Pressing necessity leave |

Maximum of four shifts |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board data.

3.2 Conclusion

Personal unplanned leave at MFESB has remained high over the period 2006–07 to 2011–12, particularly when compared with Victoria’s other emergency services. Successive senior management groups have failed to take effective action to manage unplanned leave. While MFESB’s current management is placing strong emphasis on reducing personal unplanned leave, it will take some time to determine whether recent improvements can be sustained.

Management decisions affecting staff can only be implemented with the agreement of the United Firefighters Union (UFU) due to provisions in the enterprise agreement between MFESB and UFU. Consequently, managers experience difficulty and delays in progressing operational and administrative improvements.

3.3 Unplanned leave performance

The absence of a firefighter for a single shift results in up to 14 hours lost time, nearly double the time lost in one standard working day of 7.6 hours.

While MFESB collects a range of performance data around its unplanned leave, it does not currently have a benchmark against which to assess its performance in managing personal unplanned leave.

3.3.1 Time lost due to unplanned leave

Firefighters’ personal unplanned leave has remained high, compared to Victoria’s other emergency services, and has increased steadily over the past six years.

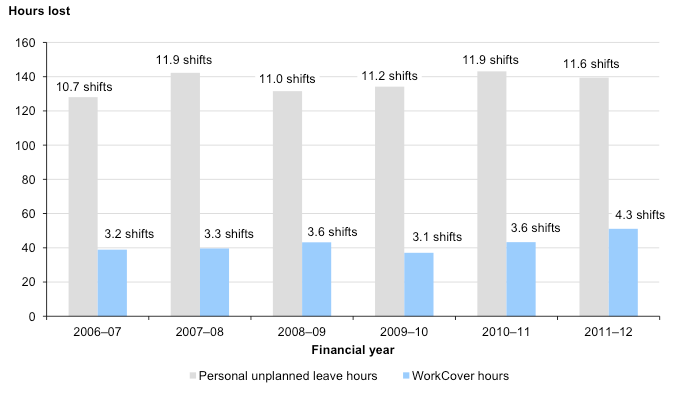

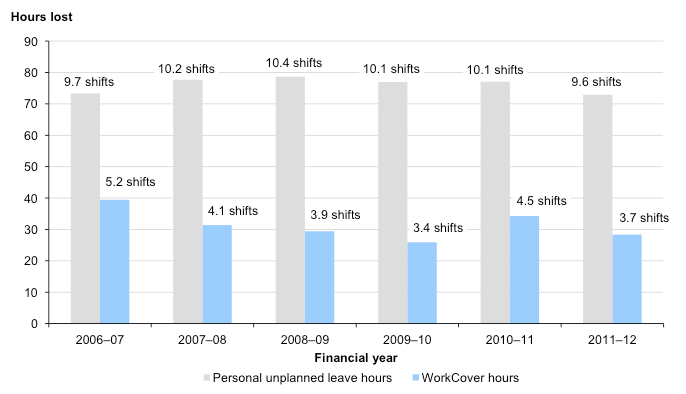

Figure 3B shows that in 2011–12 time lost due to firefighters’ personal unplanned leave averaged 139.5 hours per full-time equivalent (FTE), a slight reduction from 143.1 hours per FTE in 2010–11. Personal unplanned leave over the period 2006–07 to 2011–12 averaged 136.4 hours per FTE. Firefighters’ personal unplanned leave in 2011–12 averaged 11.6 shifts per FTE.

Figure 3B also shows that time lost due to workplace injury increased from an average of 38.9 hours per FTE to 51.1 hours per FTE over the period 2006–07 to 2011–12. The average for the period was 42.2 hours per FTE per year.

Figure 3B

Average time and shifts lost due to unplanned leave per FTE firefighter in operational roles

Note: Personal unplanned leave includes paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board data.

Figure 3C shows that MFESB’s operational and non-operational staff lost time due to personal unplanned leave of 125.6 hours per FTE in 2011–12. This is significantly above the Victorian police and emergency services average for operational and non‑operational staff of 76.0 hours per FTE.

MFESB’s average time lost for all operational and non-operational staff (125.6 hours per FTE) also compares unfavourably with other state fire services’ being significantly higher than those fire services with comparable public performance information—Tasmania (41.8, sick leave only) and South Australia (101.8, sick and carer’s leave).

Figure 3C

Lost time due to unplanned leave in fire services and the public sector, 2011–12

|

Agency |

Leave types |

Hours |

Standard working days |

|---|---|---|---|

|

MFESB firefighters |

Sick and carer’s |

139.5 |

18.4 |

|

Fire service organisations(a) |

|||

|

Sick and carer’s |

125.6 |

16.5 |

|

Sick and carer’s, including unpaid |

101.8 |

13.4 |

|

Sick and carer’s, including unpaid |

41.8 |

5.5 |

|

Victorian public sector(a)(b) |

|||

|

Sick and carer’s |

76.0 |

10.0 |

|

Sick and carer’s |

73.0 |

9.6 |

(a) Includes operational and non-operational staff.

(b) Excludes staff not employed for the whole year.

Note: Includes paid leave only unless otherwise noted. Standard working days represents time lost not actual number of absences, for example MFESB’s average working day is 12 hours for operational staff.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Victorian State Services Authority data, the South Australian Public Sector Workforce Information, June 2012 and the Tasmanian State Fire Commission Annual Report 2011–12.

3.3.2 Characteristics of unplanned leave

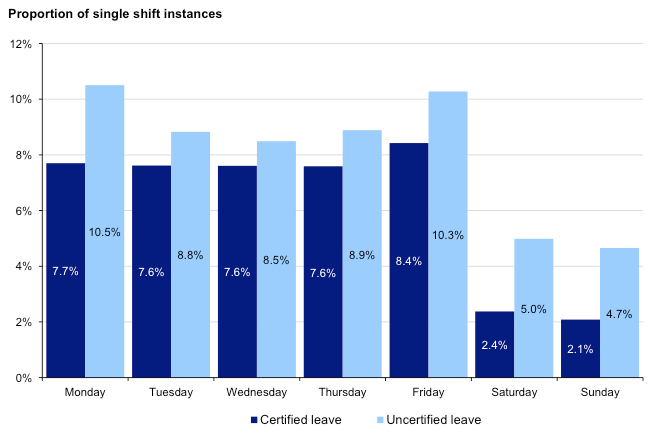

Figure 3D shows that firefighters’ take personal unplanned leave without medical evidence on weekends at twice the rate of weekdays. Twenty-two per cent of uncertified single shift absences are taken on Saturdays and 16 per cent on Sundays, compared with an average of 8.7 per cent per day on Mondays to Fridays. In contrast, personal unplanned leave supported with medical evidence is relatively stable across days of the week. This indicates a component of personal unplanned leave is discretionary and is not due to the staff member’s incapacity to attend work.

Figure 3D

Single shift personal unplanned leave by day of the week, 2011–12

Note: Includes paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board data.

Figure 3E shows that single shift absences comprise up to 72 per cent of firefighters’ periods of personal unplanned leave. Of these instances, 82 per cent are not supported with medical evidence.

Figure 3E

Breakdown of personal unplanned leave by length of absence and whether supported by medical evidence, 2011–12

Note: Includes paid sick and carer’s leave only.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office from Metropolitan Fire and Emergency Services Board data.

3.4 Oversight and monitoring

MFESB has recently improved its oversight of unplanned leave. However, management groups at MFESB have been aware of the level of firefighters’ high personal unplanned leave since 2000, but have not taken effective action to address its main causes.

MFESB’s current senior management is seeking to reduce the overtime costs resulting from personal unplanned leave and to strengthen the management of firefighters. However, the enterprise agreement contains provisions that potentially constrain MFESB’s ability to effectively manage personal unplanned leave.

3.4.1 Senior management oversight

MFESB is strengthening its oversight and reporting of unplanned leave. Its board and senior management receive regular, detailed information on firefighters’ personal unplanned leave, workplace injuries and the costs arising from unplanned leave. The MFESB’s Strategy, Planning and Resources Committee assists the board by monitoring initiatives to reduce unplanned leave and overtime costs.

MFESB commenced public reporting of unplanned leave in its 2011–12 annual report, and also plans to monitor its unplanned leave against other emergency services from 2012–13. However, current board reports show that rostered firefighters’ absences increased by over 10 per cent on average between 2000 and 2011–12.

While MFESB’s senior management is implementing strategies to address personal unplanned leave and its impacts, the gradual increase in rostered firefighters’ absences since 2000 indicates senior management groups over that period have not effectively addressed the underlying causes.

3.4.2 Industrial constraints on decision-making

MFESB entered into an enterprise agreement for firefighters, to the level of commander, with the UFU in 2010. It is legally binding on MFESB and UFU, and expires in September 2013. MFESB also has an agreement with the UFU for assistant chief fire officers, the superior officers of commanders. While government approved the firefighters’ enterprise agreement, it was not consistent with government’s wages policy and led to a review of MFESB’s funding in 2011–12.

The agreement contains provisions that cause difficulty and delays for MFESB in implementing initiatives to manage personal unplanned leave in a way that is effective and efficient.

The agreement requires that MFESB consult UFU on any change pertaining to the enterprise agreement or the employment relationship. Consultation is not limited to changes having a substantial impact on staff. Recent matters subject to consultation have included:

- arrangements for scanning and electronically communicating staff evidence of personal unplanned leave to district administration centres

- changing leave application forms from paper to electronic

- creating position descriptions for firefighters to relieve commanders during periods of long service leave

- the introduction of human resource policies and guidance notes.

MFESB is required to consult when it wishes to introduce change, rather than when a definite decision is made. The enterprise agreement requires that a consultation committee comprising an equal number of management and union representatives make decisions by consensus. The breadth of matters subject to consultation has led to MFESB and UFU establishing seven subcommittees. Matters referred to a subcommittee may be discussed over a period of months.

The agreement specifies that the only source of initiatives to improve firefighters’ attendance will be a working party comprising representatives of MFESB and UFU. Firefighters are not permitted to implement or participate in any activities to reduce unplanned leave other than those being considered by the working party.

While the working party is not currently operating, absenteeism strategies developed between 2004 and 2008 by a similar working party under a previous enterprise agreement did not result in any reduction in firefighters’ personal unplanned leave. The strategies included implementation of systems to allow firefighters to swap shifts, manage the recalling of firefighters for overtime, disseminate attendance data, and allow firefighters flexibility in taking long service leave.

The agreement provides for a dispute to be raised in relation to the enterprise agreement, the employment relationship, or the relationship between MFESB and UFU. Disputes must be resolved through steps defined in the agreement. Changes that are the subject of a dispute cannot proceed until the dispute is resolved. Recent disputes have involved two administrative actions aimed at improving MFESB’s staff records and procedures for recording temporary staff transfers.

3.4.3 Identifying the causes and impact of unplanned leave

MFESB senior managers have a good understanding of the factors causing firefighters’ high personal unplanned leave and its financial impact. However, over the past decade, little effective action has been taken to address the underlying causes.

MFESB commissioned external reviews in 2000 and 2010 that identified the causes of personal unplanned leave. The reviews arrived at similar conclusions as to the causes of personal unplanned leave:

- There are negligible penalties for firefighters taking personal unplanned leave and no positive incentives such as pay or promotion to maintain consistent attendance.

- There is a lack of pressure from colleagues to attend work because individual workloads do not increase as a result of absences. Unfilled shift positions are often filled by recalling firefighters to work overtime at double pay, creating a financial benefit for firefighters accepting the additional work.

- Firefighter managers do not have clear responsibilities and incentives to manage personal unplanned leave. Firefighter managers may avoid managing attendance because they lack clear disciplinary authority and risk conflict in confronting firefighters over attendance. Senior firefighter managers also benefit disproportionately from overtime as they are recalled more often due to their smaller numbers.

The similarity of findings from these reviews indicates there was little change in the management of personal unplanned leave, including actions to address the causes, between 2000 and 2010.

A review of MFESB’s organisational structure in 2010 identified unclear accountability throughout MFESB—a contributor to poor management of personal unplanned leave. MFESB has implemented changes recommended by the review that provide a starting point for strengthening accountability.

MFESB closely monitors overtime and the reasons for overtime. Over the period 2006–07 to 2011–12, overtime costs for firefighters rose by 30 per cent from $13.2 million to $17.2 million. MFESB estimates that personal unplanned leave accounts for approximately 50 per cent of the overtime worked by firefighters. This amounts to an average of $4 781 in overtime payments per firefighter as a result of personal unplanned leave in 2011–12.

3.5 Frontline management of unplanned leave

MFESB is improving operational management and leadership, having restructured the roles of commanders and introduced broad-based training for commanders, senior station officers and station officers.

However, firefighter managers are not held accountable for personal unplanned leave and are not provided with adequate support to effectively manage unplanned leave in their teams.

3.5.1 Frontline management of firefighters

MFESB’s operational commanders have primary responsibility for personal unplanned leave under MFESB’s enterprise agreement.

However, commanders oversee up to 13 stations and 70 firefighters and do not have direct management relationships with firefighters. While commanders intervene directly in individual cases of high personal leave, the absence of direct management relationships limits commanders’ capacity to effectively work with firefighters to address personal unplanned leave issues.

As the direct managers of firefighters, senior station officers and station officers are in the best position to manage personal unplanned leave. However, they do not play an effective role in managing unplanned leave and MFESB does not have a strategy to improve their effectiveness.

3.5.2 Accountability of frontline managers

MFESB has not created the means to hold firefighter managers accountable for their performance in managing personal unplanned leave.

Regular meetings between commanders and their superiors do not include systematic reporting on the management of individual firefighters with high levels of personal unplanned leave. Such a reporting requirement would encourage commanders to more actively work with senior station officers, station officers and firefighters to identify and resolve cases of high levels of unplanned leave.

Commanders, senior station officers and station officers are not required to undergo annual appraisals of their performance. Performance appraisals are not provided for in the firefighters’ enterprise agreement. Consequently there is little incentive for these managers to improve their management of personal unplanned leave.

Overtime payments resulting from personal unplanned leave reduces still further the incentive for firefighter managers to effectively manage personal unplanned leave.

MFESB should strengthen the performance management of firefighter managers and reduce the financial disincentives to firefighter managers reducing personal unplanned leave.

3.5.3 Services and guidance for frontline management

Data on unplanned leave

MFESB has not established systematic monitoring of personal unplanned leave by regularly providing firefighter managers with information on the personal unplanned leave taken by individual firefighters.

Without this data, commanders, senior station officers and station officers are unable to effectively identify and work with individuals to address the reasons for their high levels of leave. Commanders are also unable to monitor senior station officers’ and station officers’ management of personal unplanned leave.

To increase effectiveness in managing personal unplanned leave, MFESB should regularly provide commanders, senior station officers and station officers with data on the personal unplanned leave history of firefighters in their teams.

Support and development of frontline managers