Managing Community Corrections Orders

Overview

A community correction order (CCO) is a sentence imposed by a court that allows offenders to complete their sentences in a community setting. Offenders on CCOs may have to comply with specific conditions imposed by the courts, such as mandatory drug or alcohol treatment, and significant restrictions such as curfews and judicial monitoring. In this audit, we examined how effectively Corrections Victoria (CV) manages CCOs.

We also looked at:

- the Department of Health and Human Services to assess how well it coordinates court-ordered programs with CV

- Victoria Police, to examine how well it exchanges information with CV about offenders on CCOs.

Twelve recommendations are made in this report for CV, and one each for Victoria Police and the Department of Health and Human Services.

Managing Community Corrections Orders: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2017

PP No 225, Session 2014–17

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Managing Community Correction Orders.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

8 February 2017

Audit overview

A modern justice and corrections system aims to balance the community's desire to punish and denounce offenders with a pragmatic need to reform and rehabilitate individuals so they can return to a law-abiding life after they have served their sentence.

Prisons are Victoria's most intensive form of punishment in the hierarchy of available sentencing options. As an alternative to imprisonment, the practice of managing some offenders in the community offers significant cost savings and social benefits.

A community correction order (CCO) is a sentence imposed by a court that allows offenders to complete their sentences in a community setting. Offenders on CCOs may have to comply with specific conditions imposed by the courts, such as mandatory drug or alcohol treatment, and significant restrictions such as curfews and judicial monitoring.

In 2014–15, the cost to manage someone on a CCO was $27.55 per day, or just over $10 000 per year. This is much lower than the $360.91 per day—or more than $131 700 per year—that it costs to manage a prisoner.

A social benefit of CCOs is that sentenced offenders have the opportunity to maintain and improve their social and economic support networks in a community setting, while they make amends for their offences and undergo any court-ordered rehabilitation.

Offenders who receive community-based sentences also tend to have much lower rates of reoffending. This correlation is in part expected, as many of those on CCOs are from a relatively lower-risk cohort.

Corrections Victoria's (CV) data reports that 24.9 per cent of offenders who have been on CCOs returned to corrective services in 2014–15. This compares favourably to prisoners, 53.7 per cent of whom returned to prison or to community corrections.

CV is part of the Department of Justice and Regulation (DJR) and is responsible for directing, managing and operating Victoria's adult correctional system.

Since 2012, there have been a number of changes to legislation and sentencing practices:

- suspended sentences have been abolished

- the maximum period of imprisonment was extended from three months to two years when combined with a CCO, but recent legislative changes have reduced this period to one year

- CCOs have become a sentencing option for more serious crimes, although recent legislative changes limit their use for very serious crimes.

These changes have triggered an increase in the number of offenders on CCOs, almost doubling from 5 871 in 2013 to 11 730 in 2016.

CV recently conducted a major internal review of one of its divisions, Community Correctional Services (CCS), in response to this increase. The review identified a number of urgent challenges in the CCO system including:

- system challenges in managing unexpected growth

- legislative changes driving higher-risk offender profiles

- broadening expectations of the services that CCS delivers—community corrections being seen asbothone step away from prisonandan early intervention option for offenders

- constrained CCS resources and access to community treatment options

- challenges in recruiting and training appropriately qualified staff

- case management roles for managing serious offenders being filled by inexperienced staff.

The review proposed extensive reforms to human resources, work processes, facilities and technology to address these issues.

In the latest State Budget, the government invested $233.4 million in the community corrections system over the next four years. This includes funds to deliver most of the reforms proposed in the review, which are expected to be fully implemented by January 2019.

In this audit, we examined how effectively CV manages CCOs. We also looked at:

- the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), to assess how well it coordinates rehabilitation and support programs with CV

- Victoria Police, to examine how well it exchanges information with CV about offenders on CCOs.

Conclusion

CV's reform program is comprehensive and addresses the key challenges arising from the rapid overall increase in offenders on CCOs, including the fast-growing cohort of high-risk offenders. If implemented effectively, the reforms, along with CV's significant recruitment exercise, should reduce high case loads and improve overall management of offenders.

However, current practices for managing offenders on CCOs are not effective, and much of the effort to fully implement these reforms lies ahead. There is a shortage of adequately trained staff to meet the increase in offenders on CCOs, business processes are inefficient, and the fragmented information management environment impedes timely decision-making and effective coordination.

To better manage risks to community safety, CV needs to review its process for managing offenders who do not comply with their CCO conditions, especially the process for taking offenders back to court for breaches of conditions.

The growing number of higher-risk offenders on CCOs has added extra complexity to a system that is already struggling with high growth and high case loads. CV needs to better understand these more challenging cohorts and improve its risk assessment completion rates. It also needs to improve its communication with Victoria Police about higher-risk offenders.

The Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC) provides a highly integrated model for effective management of offenders. This includes collocation of a range of services at court (including CCS), active judicial monitoring and effective integration of all support and services. CV is trying to incorporate elements of this model into its services, but there is no active collaboration between CV and Court Services Victoria to further explore potential synergies in the two offender management models.

Findings

More higher-risk offenders

As a result of changes to legislation and sentencing practices, more offenders with a higher risk of reoffending are now serving their sentences in the community.

CV's risk assessment tools show that the percentage of offenders on CCOs with a high risk of reoffending is currently 27 per cent (at 30 June 2016) of total offenders on CCOs. Comparable historical data is not available due to possible under-assessment of high reoffending risks in the past.

Almost 40 per cent of offenders on a CCO at 30 June 2016 have had one or more terms of imprisonment, which increases the complexity of managing this cohort.

Recruitment and training

CV will grow from approximately 563 full-time equivalent staff in 2014–15 to around 963 full-time equivalent staff in 2016–17—an increase of about 71 per cent—to manage the greater numbers of offenders on CCOs.

CV has been addressing historical understaffing exacerbated by the recent growth in case loads. CCS has recorded high staff turnover for more than a decade—at an average of around 20 per cent per year between 2005 and 2015. At present, the turnover rate for entry level staff is around 43 per cent, with an overall attrition rate of almost 21 per cent. In 2015, a consultant contracted by CV estimated that this rate of attrition added $1.2 million annually to CV's employment costs.

CV has multiple recruitment strategies in place and is applying lessons learnt from the recent parole system reforms, where there were not enough suitable external candidates. CV acknowledges that it may not be able to achieve the planned expansion of CCS within its expected time lines because of a limited pool of 'work ready' external candidates.

The 2015 internal review of CCS identified that employees were unprepared and overwhelmed due to the lack of training before they entered the field. CV has now started a pre‑service training module as part of its reform program.

Information management systems

CV's information management systems are inefficient and fragmented, with no single source of accurate data about offenders. Case managers must access multiple systems to extract the information they need to do their job.

The CV reforms proposed to introduce a modern, consolidated information technology system to manage offenders. However, this project was not separately funded in the last State Budget.

CV continues to seek funding for a more robust information management system as a strategic priority. In the meantime, it is working to increase the capacity and performance of its legacy systems.

Contingency planning for the reform program

CV has set itself challenging deadlines to deliver its reform program.

However, CV has limited contingency plans in place, and there is a risk that it may not be able to implement the reforms by the planned deadlines. There are early positive signs that CV is fixing any implementation issues when they occur.

Risk assessments of offenders

Robust risk assessments of offenders in the community are the foundation for effective supervision and management of offenders. CV uses a suite of tools to determine an offender's risk of reoffending.

However, CV is not consistently completing full risk assessments within the required six-week time frame. A recent CV internal report notes that only 55 per cent of risk assessments are being completed on time, which means that potential risks to the community are not understood or managed.

Support programs and services

Some of the rehabilitation conditions that the courts may attach to a CCO include participation in support programs. These include alcohol and other drug (AOD) programs, offending behaviour programs (OBP), and use of mental health services.

In 2014–15, almost 74 per cent of offenders had at least two conditions on their CCO. In 2015–16, almost 85 per cent of CCOs had AOD conditions attached. The number of CCOs with rehabilitation conditions is increasing due to there being more offenders in the system and more CCOs with multiple conditions.

This has led to increasing demand for support programs and services which, in turn, has led to offenders facing significant wait times when trying to access programs—such as an average of 20 business days for AOD programs. Almost 40 per cent of serious risk offenders on the OBP screening priority list waited more than three months for a pre‑assessment screening.

For mental health conditions, some offenders on CCOs may have to make a gap payment for their treatment, which can prevent or discourage them from participating.

CV's business plan indicates that excessive wait times can increase the risk that an offender poses to the community as the offender's underlying situation has not yet been assessed and is therefore unmanaged.

CV is working to reduce wait times by increasing the capacity of existing programs. CV is also working with DHHS to improve access to mental health programs.

Managing breaches of CCOs

Victoria's rate for offenders completing CCOs is the second lowest for all Australian jurisdictions at 66.5 per cent, with the lowest in Western Australia at 61.2 per cent. The highest rate of completion is in Tasmania at 87.6 per cent, and the national average is 72.9 per cent.

Case managers use their skills, networks and experience to help offenders complete CCOs. However, CV admits that significant workloads for case managers—more than 60 offenders per officer in some locations—hamper prompt management of offenders who do not comply with the conditions of their CCO.

CV's reform program plans to bring this case load down to between 25 and 40 offenders per case manager, depending on the risk and complexity of the offenders.

Better practice in managing offenders

Collingwood's NJC has been an innovative model for managing offenders since its establishment in 2006. It uses a holistic and integrated approach to managing offenders, with close coordination of support services and effective judicial monitoring.

Although the NJC model has been externally assessed as effective—and CV has tried to incorporate some elements of the model in its offender management practices—CV is not working strategically with Court Services Victoria to more fully apply this model to other parts of the corrections system.

Monitoring and reporting framework

Staffing problems and heavy case loads affect how well CV can supervise offenders. CV's current performance measures mostly focus on compliance and outputs, but it is planning to improve these measures as part of its reform program.

CV will find it difficult to achieve this objective without an integrated information system to generate reliable data.

Evaluation activities

The 2015 review of CCS is a good example of a robust organisational evaluation, and its recommended reforms are based on identified problems.

CV is planning to evaluate the effectiveness of the reforms and expects to have an evaluation plan in place by February 2017. To date, however, CV has not effectively evaluated its support programs and services.

Recommendations

We recommend that Corrections Victoria:

- include community safety as a key strategic principle for managing offenders on community correction orders, in line with the approach used for offenders on parole (see Section 2.2)

- monitor and review the implementation of planned reforms of the community corrections system, to make sure they are achieving their objectives (see Section 2.5.4)

- develop a robust contingency plan for the reforms program, to address all time‑critical stages (see Section 2.5.4)

- monitor and evaluate staff training to make sure it is sufficient and fit for purpose (see Section 2.5.3)

- ensure risk assessments are completed within required time frames, and validate the current risk assessment tools to make sure they are effective (see Section 3.3)

- improve information technology systems to enable case managers to manage offenders on community corrections orders more effectively and to provide a single source of accurate data about offenders (see Section 2.6)

- work with Court Services Victoria and other relevant stakeholders to explore effective and innovative models for managing offenders in the community, including applying elements of the NJC model (see Section 3.6)

- reduce wait times for support programs and services by making sure that enough programs are available to offenders on community correction orders (see Sections 3.4.3, 3.4.4 and 3.4.5)

- review the way it shares information with Victoria Police to make this process more effective and timely (see Section 3.5.3)

- review the way it manages offenders who breach the conditions of their community correction orders and, where needed, provide advice to government on making the breach process faster and more effective (see Section 3.5.2)

- regularly evaluate support programs and services for offenders on community correction orders, to make sure they are achieving their objectives (see Section 4.3.2)

- develop more strategic monitoring and reporting of support programs and services for offenders on community correction orders, to provide better-quality information for decisions about future programs (see Section 4.3.1).

We recommend that Victoria Police:

- develop an effective mechanism, in coordination with Corrections Victoria, to improve monitoring of offenders on community correction orders, particularly offenders who present a higher risk to the community (see Section 3.5.3).

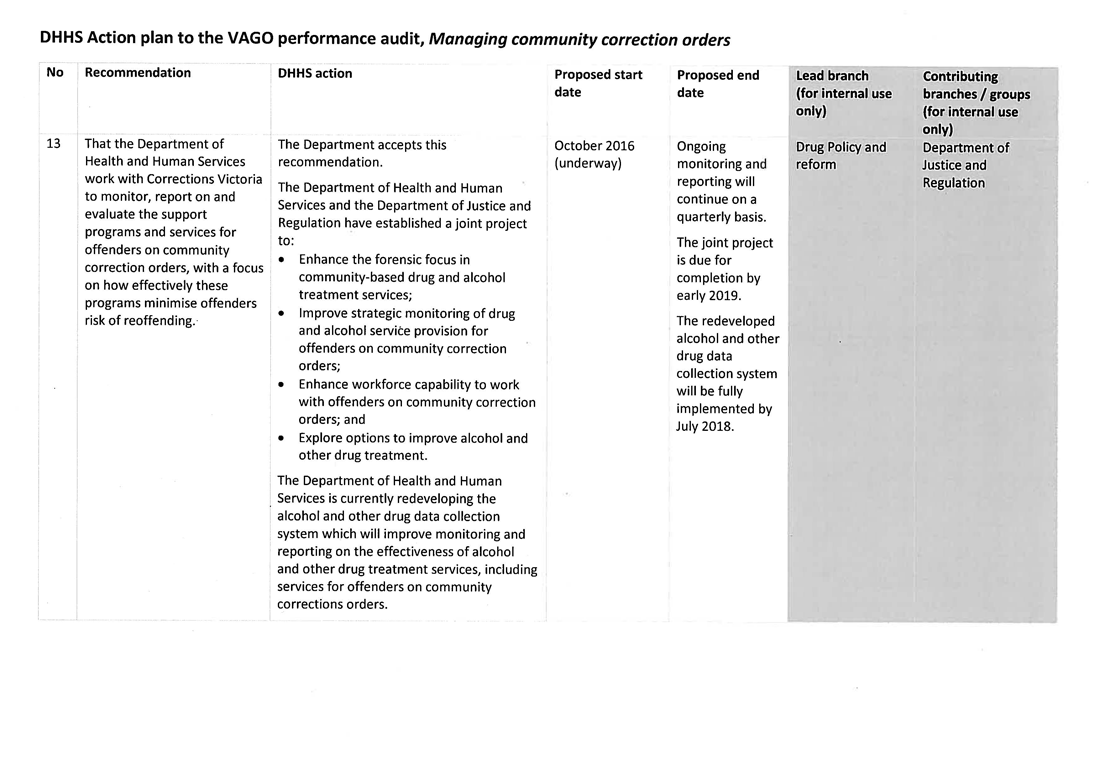

We recommend that the Department of Health and Human Services:

- work with Corrections Victoria to monitor, report on and evaluate the support programs and services for offenders on community correction orders, with a focus on how effectively these programs minimise offenders' risk of reoffending (see Sections 4.3.1 and 4.3.2).

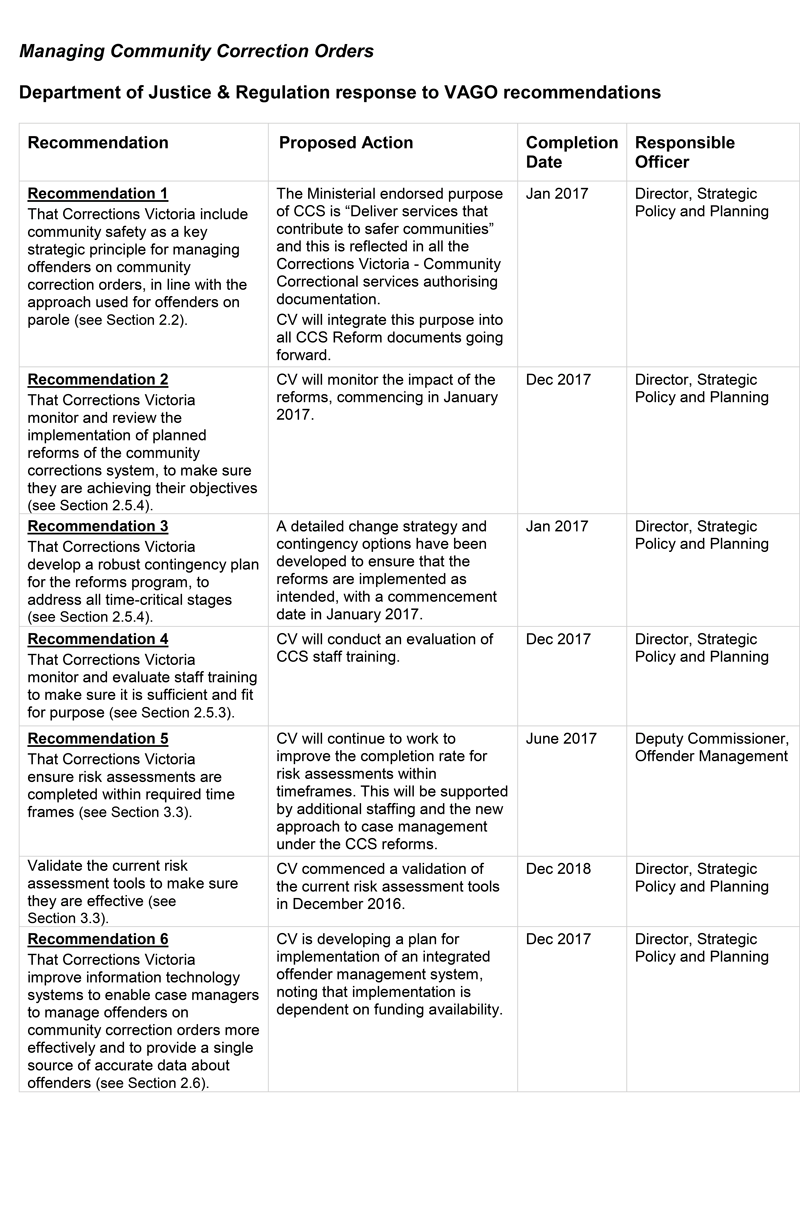

Responses to recommendations

We have professionally engaged with Corrections Victoria (within the Department of Justice and Regulation), the Department of Health and Human Services, and Victoria Police throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report or relevant extracts to those agencies, and requested their submissions and comments.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

The Department of Justice and Regulation (Corrections Victoria) accepted all of our recommendations and provided a detailed action plan on how it plans to address them. We noted that Corrections Victoria has already commenced acting on a number of our recommendations. The Department of Health and Human Services and Victoria Police also accepted the recommendations addressed to them. Victoria Police committed to working with Corrections Victoria to develop more effective information sharing to assist Corrections Victoria to monitor offenders on community correction orders. The Department of Health and Human Services responded with a commitment to work with Corrections Victoria to monitor, report on and evaluate the support programs and services for offenders on community corrections orders.

1 Audit context

1.1 About community correction orders

A community correction order (CCO) is a sentence imposed by a court that allows offenders to complete their sentence in the community, rather than going to prison.

CCOs aim to both punish and rehabilitate offenders by addressing the circumstances and underlying causes of offenders' behaviour, as well as minimising the risk of them reoffending. Offenders on CCOs may have to comply with significant restrictions while they are completing their sentence in the community.

Restrictions ordered as part of a CCO can include:

- curfews

- specifying where an offender must live

- restricting an offender from nominated places or zones

- stopping an offender from consuming alcohol

- periodic monitoring of an offender's progress by the courts.

Conditions included in CCOs

CCOs always include one or several conditions that the offender must comply with—these conditions are made by judicial officers who take into account the type of crime that the offender has committed, as well as the offender's individual needs. The conditions of a CCO may require offenders to:

- do unpaid community work

- be supervised while they are completing their sentence

- undertake treatment and rehabilitation programs designed to help offenders get their lives back on track and stop them from committing further crimes.

Types of CCOs

There are two basic types of CCOs:

- unsupervised CCOs—which involve unpaid community work and are also known as reparation orders

- supervised CCOs—which may have a supervision condition attached to them and may include other restrictive conditions and participation in support programs.

CCO imprisonment orders

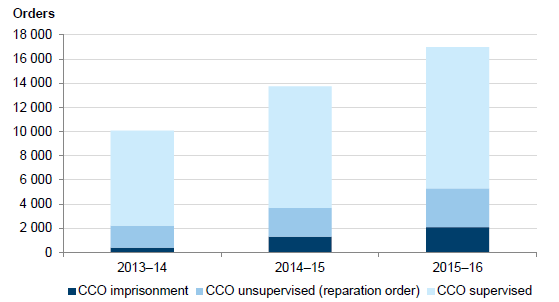

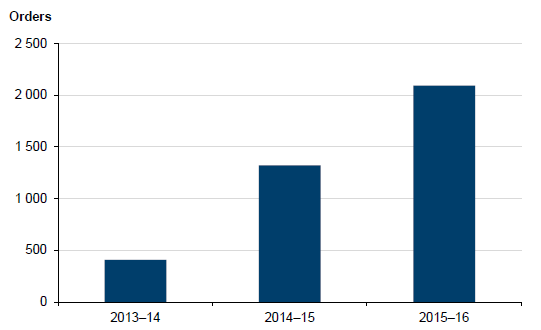

A CCO imprisonment order is a combined order that includes a period of imprisonment followed by a CCO. Under previous legislation, the maximum prison term for a CCO imprisonment order was two years, but new legislation passed by Parliament in November 2016 has reduced this period to a one-year maximum.

Between 2013–14 and 2015–16, the number of CCO imprisonment orders imposed on offenders increased by more than 400 per cent.

1.1.1 Advantages of CCOs

Research shows that imprisonment generally has negative impacts for both the offender and the wider community. Prisons are expensive to run and compete with other social services for scarce public resources.

Reducing the risk of reoffending

Because CCOs can include conditions that address an offender's specific needs, they can help to reduce the risk of an offender committing further crimes, which improves community safety.

When compared to people who go to prison, those on CCOs have a significantly reduced risk of reoffending, although they do tend to come from a lower-risk cohort so the link may not always be causal. According to data from the Department of Justice and Regulation (DJR) for 2014–15:

- 24.9 per cent of offenders on CCOs reoffend and go back through the correctional system within two years

- 53.7 per cent of offenders who have been to prison reoffend and either return to community corrections or prison within two years of release.

Providing benefits for the community

CCOs can also have a range of social benefits, such as maintaining and improving social and economic support networks for a sentenced offender, while they undergo rehabilitation and make amends for their offences in a community setting.

In addition, many CCOs have a condition that requires offenders to perform unpaid work in the community as a form of punishment that allows them to make amends to society. More than a thousand organisations are involved in the community work programs used by the community corrections system. DJR estimates that in 2015–16 this unpaid work was equivalent to $24.3 million in value for the Victorian community.

Offenders serving sentences within the community can pose some risk to society. However, effective management of offenders in the community can minimise these risks.

Reducing the cost of managing offenders

The 2016–17 Victorian Budget estimates the cost of prisoner supervision and support to be $1.1 billion each year. The Victorian Ombudsman's September 2015 report Investigation into the rehabilitation and reintegration of prisoners in Victoria commented that 'prison is also the most expensive response we have to criminal behaviour' and that 'some alternatives work'.

CCOs are a cost-effective alternative to imprisonment. The Productivity Commission's 2016 Report on Government Services showed that, in 2014–15, the daily total cost of managing someone on a CCO was $27.55 (or just over $10 000 per year). This is much lower than the $360.91 per day (more than $131 700 per year) that it costs to manage someone in prison.

1.2 Changes to legislation

Since 2011, changes in legislation and sentencing practices have increased the number of offenders on CCOs.

Abolishing suspended sentences

The Sentencing Amendment (Community Correction Reform) Act 2011 changed the range of sentencing options that courts can use.

The changes replaced several existing sentencing options—such as suspended sentences, intensive correction orders and community-based orders—with a single comprehensive and flexible order, the CCO. These changes allow courts to include restrictive conditions in CCOs.

Before the legislation was updated, offenders who had received a suspended sentence could continue to live in the community with no supervision or monitoring. During 2010–11, there were 7 408 wholly or partially suspended sentences orders made, but this number had declined to 3 105 orders made in 2014–15.

Reforming the parole system

In 2013, the government commissioned the Review of the Parole System in Victoria (known as the Callinan Review). This review recommended reforms that have significantly changed the corrections system. Community Correctional Services (CCS), a division of Corrections Victoria (CV), was divided into two streams—one dedicated to offenders on parole and the other focusing on offenders on CCOs. As a result of the reforms, a number of senior staff from the CCO stream moved to the parole stream.

The government invested $84.1 million over a four-year period to reform the parole system in line with the recommendations from the Callinan Review. Under the reforms, breach of parole became a criminal offence and the eligibility criteria for granting parole became more stringent.

Clarifying the purpose of CCOs

The Sentencing Amendment (Emergency Workers) Act 2014 introduced stronger penalties for violent offences against emergency workers on duty.

The amendment also clarified the purpose of CCOs. It states that a court must not sentence an offender to time in prison if the same sentencing outcome could be achieved through a CCO with one or more restrictive conditions. The amendment also extended the maximum time that an offender can be sentenced to prison if they had a combined CCO, increasing it from three months to up to two years.

Broadening the use of CCOs

In December 2014, a judgment by the Victorian Court of Appeal in the cases Boulton v The Queen, Clements v The Queen and Fitzgerald v The Queen (2014) found that CCOs were different from the range of community-based sentencing options that had previously been available.

The Court of Appeal stated that CCOs give courts a sentencing option that may address the underlying causes of an offender's behaviour. The Court of Appeal also stated that CCOs could be used for more serious crimes, which has broadened the range of offenders who may receive CCOs.

Amending legislation

On 12 October 2016, the Premier of Victoria announced that the government would amend legislation to stop the use of CCOs for some serious crimes. The Sentencing (Community Correction Order) and Other Acts Amendment Bill 2016 was passed by Parliament in late October, receiving Royal Assent on 11 November 2016.

The amended legislation also:

- reduces the maximum prison sentence for an offender on a combined CCO, from 24 months to 12 months

- prevents non-parole periods being included in a combined CCO, which means that offenders must serve their full sentence in prison before beginning their CCO

- limits the maximum length of a CCO to five years.

1.3 Sentencing trends

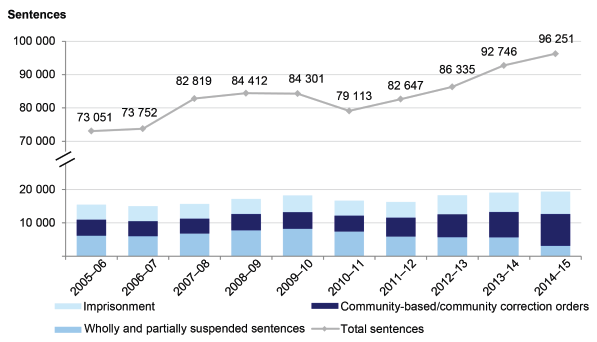

Changing legislation has affected sentencing trends in Victoria. Figure 1A shows the current trends in sentencing in Victoria.

Figure 1A

Sentencing trends in Victoria, 2005–06 to 2014–15

Note: The total number of sentences includes other types of penalties such as fines, training programs and dismissals.

Source: VAGO, based on data from the Sentencing Advisory Council.

As shown in Figure 1A, between 2005–06 and 2014–15:

- the overall number of sentences increased by approximately 32 per cent

- the number of imprisonment sentences increased by 49 per cent

- the number of CCOs, including community-based orders made before the 2011 changes to legislation, increased by 99 per cent

- the number of wholly and partially suspended sentences decreased by 50 per cent.

At the time of this audit, the Sentencing Advisory Council had not published data for 2015–16.

Increase in CCOs

The new legislation introduced in 2011 has resulted in more CCOs. Since 2013–14, the total number of CCOs registered has grown by approximately 68 per cent. Figure 1B shows the growth trend for all types of CCOs.

Figure 1B

Growth in registered CCOs, 2013–14 to 2015–16

Source: VAGO, based on data from CV.

Figure 1B shows the total number of orders, because offenders might have multiple orders in place. The number of offenders on a CCO has increased from 5 871 on 30 June 2013 to 11 730 on 30 June 2016—an increase of almost 100 per cent.

1.4 Roles and responsibilities

While CV has overall responsibility for managing offenders on CCOs, a number of agencies are involved in the process.

Corrections Victoria

CV is responsible for directing, managing and operating Victoria's adult correctional system. It sets standards, policy and strategy for the management of prisoners and offenders.

One of CV's strategic priorities is to provide a correctional system that delivers 'the highest standards for the safe and secure management of offenders'.

Within CV, CCS is the division responsible for managing and supervising offenders on CCOs. CCS is overseen by CV's Deputy Commissioner Operations.

Department of Health and Human Services

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) oversees the delivery of alcohol and drugs assessment and treatment programs for offenders on CCOs.

DHHS uses the Community Offender Advice and Treatment Service to assess and broker alcohol and drug treatment programs through a network of community-based providers.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police detects breaches of CCO conditions by reoffending as part of its policing activities. It shares relevant law enforcement data with CV.

By sharing data, police officers can find out if a person they are dealing with is on a CCO, and CCS case managers can then see that an offender under their supervision has been in contact with the police.

Court Services Victoria

Court Services Victoria (CSV) provides administrative services to Victoria's courts, including scheduling hearings, maintaining court buildings and allocating space for other services within court buildings.

CSV also funds the Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC), which operates as a venue of the Magistrates' Court of Victoria. The NJC was established in 2006 and uses an integrated model to manage offenders, involving magistrates, Victoria Police, CCS, Victoria Legal Aid, Fitzroy Legal Service and a range of other government and community service providers.

Sentencing Advisory Council

The Sentencing Advisory Council (SAC) is an independent statutory body established under the Sentencing Act 1991. SAC gathers statistics about sentencing practices and advises the Attorney-General on sentencing issues. It acts as a link between the community, the courts and government.

From July 2016, SAC must report annually on the number of people on CCOs who have been convicted of a serious offence while on a CCO. SAC's first report is due in 2017.

1.5 Previous performance audits

Our 2009 audit Managing Offenders on Community Corrections Orders examined how effectively CCS manages offenders on community orders. It found that CCS had a robust, evidence-based framework for managing offenders. However, the outcome measures were not directly relevant and there was no meaningful way to measure the effectiveness of the program.

The audit was conducted before the 2011 legislative amendments changed the way CCOs are structured, allowing for more serious offenders to be given CCOs.

1.6 Why this audit is important

While it is clear that CCOs can provide a range of benefits for offenders and for the community, they also present some risks. Effective management of CCOs requires cooperation from a number of agencies. In addition, recent legislative changes have resulted in more offenders with complex needs being put on CCOs.

If the CCO system is not effectively managed, offenders may not benefit from the rehabilitative aspect of their sentence and the community's safety may be put at risk.

1.7 What this audit examined and how

In this audit, we examined how effectively CV and the other agencies involved manage CCOs. We assessed whether they are effectively:

- planning the strategy for and operations of CCOs

- managing offenders on CCOs

- monitoring, reporting on and evaluating the outcomes of CCOs.

CCS within CV was the primary focus of the audit. We also looked at DHHS and Victoria Police to assess how they coordinated and exchanged information about offenders on CCOs.

We did not audit CSV, but we did use the NJC model as a case study—see Part 3.

This audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards, and cost $470 000.

1.8 Report structure

The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 looks at planning for change within the correctional system

- Part 3 examines the management of offenders

- Part 4 discusses the monitoring, reporting and evaluationof CCOs.

2 Planning for change

Since 2011, legislative changes have significantly reformed Victoria's correctional system, including how community correction orders (CCO) are managed. To successfully implement these reforms, Corrections Victoria (CV) and the other agencies involved in managing CCOs need to identify and understand issues, communicate effectively with stakeholders throughout the CCO process, and allocate sufficient resources.

This Part looks at how effectively CV has planned to manage changes in the community corrections system.

2.1 Conclusion

CV's reform program is comprehensive and aims to address the key management issues arising from the growing number of high-risk offenders on CCOs who require attention. Looking ahead, CV's plan to recruit significant numbers of new staff should reduce case loads, making effective offender management more likely. However, the reform program is in the early stages of implementation, so we were not able to assess it as part of this audit.

CV's previous training regime for new staff was not effective—it resulted in a poorly trained workforce which, in turn, had a negative impact on CV's delivery of community correctional services. CV is now focusing on training staff before they start their jobs. If this training is delivered effectively, staff will be more job-ready and will develop the requisite skills. There is still a risk that CV's training programs will be disjointed because multiple business units are responsible for training, and there is limited strategic monitoring and reporting.

CV's management of information is inefficient. There is no single source of accurate data on offenders, which increases the chance of error. CV has not been able to secure funding to develop an integrated offender management system, which means the current information and technology management problems will continue.

CV's stakeholder engagement has generally been good, although CV did not involve the courts during the early stages of planning for its revised service delivery model. CV is now taking more concrete steps to engage with the courts on this matter.

The schedule for implementing reforms to the management of CCOs has an ambitious time line, with limited contingency plans for any unexpected issues or events. However, CV is adapting its plans to manage unexpected issues.

2.2 Setting strategic priorities

CV has a clear overall purpose—'delivering effective correctional services for a safe community'—but its guiding principles only state this goal explicitly for the management of parolees, not for offenders on CCOs.

CV's strategic plan 2015–18 identifies its guiding principles:

- Parole—CV will administer a parole system that has community safety as the paramount consideration.

- CCOs—CV will build the capacity of Community Correctional Services (CCS) tosupport the CCO and community work program to reduce reoffending and enhance rehabilitation.

As part of its current reform program, CV has adopted and internally communicated the new purpose and objective statement of 'deliver services that contribute to community safety'.

However, CV needs to more explicitly include community safety as an important strategic guiding principle for CCOs, especially given the increasing risk and complexity posed by the range of offenders on CCOs. CV acknowledges the need to further integrate its purpose into all relevant documents in the future.

2.3 Managing offenders

Recent changes to Victorian legislation have changed the type and number of offenders on CCOs. In particular, offenders with more complex criminal backgrounds may now be sentenced to a CCO rather than serving time in prison.

Almost 40 per cent of offenders on CCOs have previously spent time in prison. Figure 2A shows the data for prior terms of imprisonment by offenders on CCOs as at 30 June 2016.

Figure 2A

Prior terms of imprisonment for offenders on CCOs, 30 June 2016

|

Number of prior terms of imprisonment |

Number of offenders |

Per cent of cohort |

|---|---|---|

|

0 |

7 082 |

60.4 |

|

1 |

2 158 |

18.4 |

|

2 |

994 |

8.5 |

|

3–4 |

810 |

6.9 |

|

5–9 |

502 |

4.3 |

|

10–19 |

167 |

1.4 |

|

More than 20 |

17 |

0.1 |

|

Total |

11 730 |

100.0 |

Source: VAGO, based on data from CV.

2.3.1 Managing more complex cases

As a result of the increased use of CCOs and the wider range of offences that can be sentenced to a CCO, more complex offenders are completing their sentences in the community. These offenders are on either:

- a standalone CCO

- a CCO imprisonment order, where the CCO is served after a term of imprisonment.

The number of offenders on CCO imprisonment orders has significantly increased in the last three years, as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Number of combined orders (CCOs with imprisonment) registered, 2013–14 to 2015–16

Source: VAGO, based on data from CV.

The increasing number of combined orders means that more offenders are being released from prison to CCS supervision. This highlights the need for CCS staff to have the relevant experience and skills to manage the transition needs of these types of offenders.

2.3.2 Offenders' risk profile

CV is managing a significant proportion of high-risk offenders in the community, as shown in Figure 2C.

Figure 2C

Proportion of high-risk offenders, 2013 to 2016

|

Year |

High-risk offenders |

Total offenders |

High-risk offenders as a percentage of total |

|---|---|---|---|

|

2013 |

285 |

5 871 |

4.9 |

|

2014 |

128 |

7 009 |

1.8 |

|

2015(a) |

1 032 |

9 660 |

10.7 |

|

2016(a) |

3 180 |

11 730 |

27.1 |

(a) CV changed its risk assessment tool in January 2015.

Source: VAGO, based on data from CV.

In January 2015, CV replaced its previous risk assessment tool, the Victorian Intervention Screening Assessment Tool (VISAT), with the Level of Service (LS) suite of tools. CV told us that results from VISAT cannot be compared to risk distributions produced by LS because they are different risk assessment tools. CV had identified issues with the application and robustness of VISAT in August 2014, including 'possible under-assessment of high-risk offenders in the community'. The tools are further discussed in Part 3.

CCOs are being used for more serious crimes, which is indicative of higher-risk offenders being managed on CCOs.

As part of the planned reforms discussed in Section 2.4, CCS has developed a new model for the way it delivers its services to manage more complex offenders. This model includes:

- CV staff doing more focused court assessments

- treating offending behaviour while in prison

- using a more effective case allocation model to ensure that more senior staff manage complex offenders

- making more effective arrangements to manage offenders' transition from prison into the community, using a tailored case management approach for complex offenders

- increasing oversight by operations managers.

CCS's new model is similar to the reformed parole stream model. However, increased workloads at CCS, a lack of experienced staff and inefficient processes have made it more difficult to manage complex offenders. Addressing these issues will help CV to realise the full benefits of the planned reforms.

2.4 CCS internal review and reforms

Because of changing legislation and the complex nature of its work, CV needs to quickly respond to changes in sentencing and plan ahead to address risks.

CV has recognised these issues—in an internal briefing, it stated that unexpected growth in offender numbers and reduction in the number of prisoners on parole are some of its key challenges.

The recommendations from the Department of Justice and Regulation's 2015 Review of Community Correctional Services: CCS review and reform program (CCS internal review) will reform the way CV manages CCOs. Many of the planned reforms are similar to the parole system reforms that CV recently introduced.

The key findings of the CCS internal review included:

- overall CCS system challenges in managing unexpected growth

- legislative changes driving higher-risk offender profiles

- broadening expectations of the services that CCS delivers—community corrections being seen as both one step away from prison and an early intervention option for offenders

- constrained CCS resources and access to community treatment options

- challenges in recruiting and training appropriately qualified staff

- case management roles for serious offenders being filled by inexperienced staff

- a 45.3 per cent attrition rate for entry-level staff, including fixed-term positions

- a lack of appropriately skilled CCS staff working on court assessments.

The reform program includes actions such as:

- hiring 161 extra staff, funded by recent budget commitments

- providing better training for existing and new staff

- paying staff better wages and giving them more specific position descriptions, confirmed in the latest enterprise bargaining agreement

- developing infrastructure, such as more field offices

- implementing a new service delivery model

- introducing a pre-service induction training module

- improving business processes

- addressing information technology issues

- working with educational institutions and other stakeholders.

The reforms also create specialised work streams within CCS to better manage distinct operational activities.

The planned service delivery model uses a case management approach based on risk and needs. This should allow CCS to more effectively supervise higher-risk offenders.

These are significant changes, but some of the current proposed reforms address problems that were first identified in a 2007 organisational review. Although CV has a good understanding of its business and capacity to plan, it has not yet been able to effectively address some longstanding problems. CV told us that it considered the workforce classification structure as the major constraint. This has now been resolved by making CCS staff remuneration comparable to remuneration for similar services.

2.5 Staff recruitment and training

CV has not identified and implemented effective strategies for managing its workforce.

The 2015 CCS internal review identified several problems with CCS's workforce planning, including:

- the lack of an overall strategy for recruiting new staff

- a centrally planned workforce strategy with little involvement from field offices

- a rigid resource allocation model (RAM), disconnected from forecasting processes, which did not incorporate location-specific needs

- not specifically identifying case management as a required capability for CCS staff

- using identical position descriptions in both the court and community work streams.

In response to the recommendations from the review, CV is planning to replace the RAM with a new workforce distribution model. This model is in the final stages of development.

CV has also updated position descriptions for various roles and has included case management capability as a requirement for different work streams. CV has recently developed a draft recruitment strategy for CCS and an overarching workforce strategy that addresses previously identified issues.

2.5.1 Staffing levels

CV was not well prepared for the unexpected increase in workloads that has occurred over the last few years. As an example, CV's response to an incident shows the impact of this lack of preparation: '[We] did not anticipate that court stream staff would need to manage such large case loads, often in excess of 60 cases, and as a result the intensity of case management is likely to be affected.'

CV will grow from approximately 563 full-time equivalent staff in 2014–15 to around 963 full-time equivalent staff in 2016–17—an increase of about 71 per cent—to manage the growth in offenders on CCOs.

During our visits to field locations, we observed that case managers had very high case loads due to the high growth in CCOs as well as staff shortages.

Staff turnover

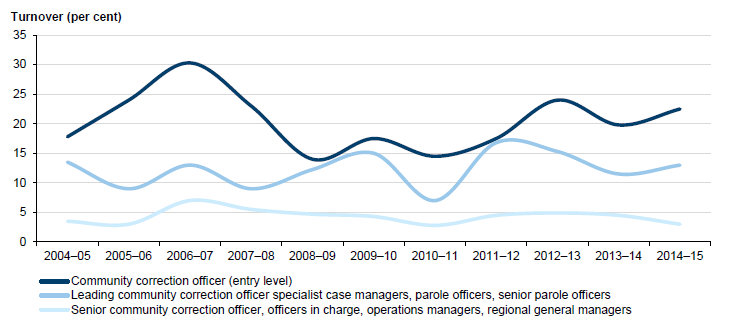

CCS has had very high staff turnover for more than a decade—approximately 20 per cent per year, particularly for entry-level roles. This is shown in Figure 2D.

Figure 2D

CCS staff turnover, 2004–05 to 2014–15

Source: VAGO, based on data from CV.

An external consultant estimated the cost of this high staff turnover at $1.2 million per year.

A staff survey identified the main reasons for staff turnover, including:

- career prospects (identified by 44.3 per cent of staff)

- pay (38.8 per cent)

- work environment/pressure (32.3 per cent).

The survey showed that almost 20 per cent of staff were looking to leave within one year. Another 15 per cent planned to leave in one to two years. Our site visits confirmed that work pressures significantly affect retention.

In August 2016, CV negotiated a new enterprise bargaining agreement that allows for specialised work streams and an upgrade of positions. The reduced case loads planned under the new agreement are likely to reduce work pressures and improve staff satisfaction. This would lead to better retention of staff.

As part of the budget submission, CV assumed 25 per cent attrition of CCS staff in its modelling.

CV will need to carefully monitor and evaluate changes in offender numbers and staff case loads to ensure that the proposed reforms achieve the desired impact.

2.5.2 Recruiting new staff

CV intends to have 161 newly hired and trained staff on board by April 2017. This is a very challenging task, as 101 of these staff will be advanced case managers. These new positions will deal with complex cases, including sex offenders and offenders on CCO imprisonment orders. These new case managers are expected to have a lower case load of approximately 20 complex cases per case worker.

As well as recruiting in Victoria, CV is looking for prospective staff from other Australian states and overseas.

As part of the parole reforms, CV used a similar approach to recruit for new positions, but it was unsuccessful, particularly for regional and rural staff. CV states that because it has a relatively small pool of prospective employees, it may not be able to recruit the large number of external candidates it requires. An October 2016 report shows CV has hired 60 per cent of the 101 advanced case managers, with 49 per cent of these being external candidates. The recruitment process is ongoing.

2.5.3 Training

The complex nature of CCS's work means that its staff require an effective training program to prepare them for their challenging roles.

In the past, unlike most other jurisdictions, CV did not train staff before putting them in the field. Induction would take place at field offices, including completion of mandatory e‑learning modules. This was followed by further on-the-job training. The CCS internal review confirmed that this lack of pre-service training left employees 'unprepared and overwhelmed'.

CV has recently started giving six weeks of training to new employees before they work in the field. New employees must complete this training as part of their contract. CV told us it plans to evaluate this pre-service training in the future.

Various jurisdictions require employees to complete different periods of training before working in the field, as shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Comparing pre-service training across jurisdictions

|

Jurisdiction |

Pre-service training |

|---|---|

|

Queensland |

5 weeks |

|

Victoria(a) |

6 weeks |

|

New South Wales |

8 weeks |

|

Australian Capital Territory |

9 weeks |

|

Northern Territory |

12 weeks |

|

New Zealand |

12 weeks |

|

Western Australia |

6 months |

|

United Kingdom |

15 months |

(a) Pre-service training was recently started in Victoria following the reforms.

Note: Tasmania currently does not have any pre-service training.

Source: VAGO.

New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia have dedicated correctional services training academies. CV is in early planning stages for a similar facility in Victoria.

Fragmented learning

Responsibility for training CCS staff is currently distributed across different business units with no single point of accountability. Staff evaluate their own training needs and managers guide them. If staff are managing significant case loads, completing training becomes a greater challenge due to time demands.

Making a specific business unit responsible for training would enable CCS to plan and manage staff training requirements more effectively and offer a clearer picture of training needs.

Once CV has implemented the reforms, it will also need to check that training modules are effective and achieving the desired objectives.

2.5.4 Implementing reforms

CV received funding in the 2015–16 Budget for most of the initiatives recommended in the 2015 CCS internal review. CV has started to implement these initiatives.

CV has set itself challenging deadlines for a significant amount of work and has limited contingency plans in place if it misses important milestones. However, there are early signs that CV is taking corrective measures when implementation problems occur. CV is also adjusting planned time lines for the project based on how the reforms are progressing.

CV has begun recruiting new staff, although a lack of sufficient and appropriate candidates has prompted CV to extend its staff commencement deadlines from January to April 2017.

CV has started work to create more office space for these new staff members. CV also told us that projects are underway to expand the E-Justice case management system's ability to support more users, and enhance its data storage and processing capacity.

One of CV's medium-term recruitment strategies is to attract graduates with social work degrees and other related disciplines. This is expected to provide a steady supply of suitably qualified case managers, who will have the required understanding of the role and be able to start work quickly.

The initial planning date for this was January 2019. However, as the project progresses, CV has revised the planned start date for graduate recruits to January 2020. This is still challenging as it only gives CV a little more than three years to put a curriculum in place and develop relationships with tertiary institutions to achieve this objective.

2.6 Information management systems

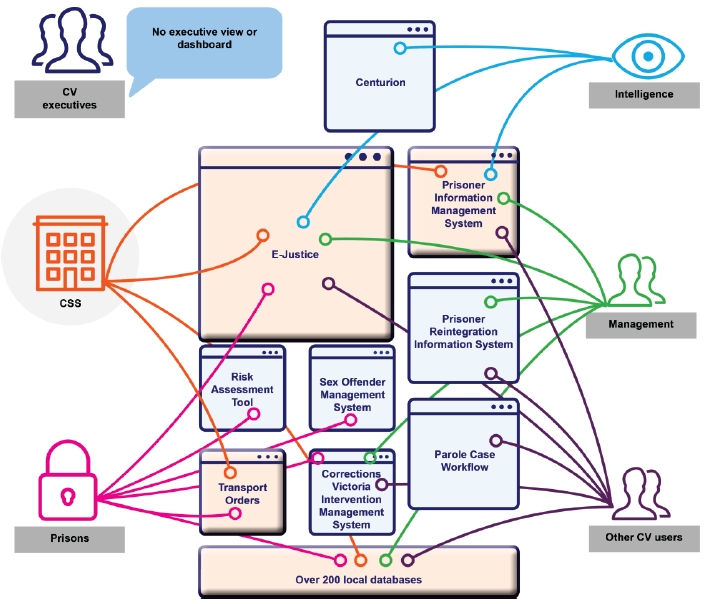

To make timely and effective decisions, case managers and CV require quick access to accurate information. We found that information is not easily accessible because of the fragmented and complex information systems in place.

2.6.1 Current information systems environment

CV's existing information systems are highly fragmented and complex, and there is no single source of accurate information about offenders.

We observed that case managers must use multiple systems to extract the information they need. These systems include a tool for assessing offender risks, two different systems to manage and oversee offender support programs, and separate systems for understanding sentencing requirements and managing cases.

The CCS internal review found several problems with the way CV managed its information technology (IT) systems:

- some IT systems are past their functional life

- CV's IT systems cost $16.5 million a year to maintain, and this cost is expected to be $21 million by2020

- more than 200 shadow systems are used at prisons and CCS locations

- the various systems result in information being duplicated, increasing the risk of error

- documents are not being efficiently digitised

- existing systems cannot be updated to support mobile applications or devices

- data must be analysed manually to identify trends and offender profiles

- the E-Justice case management system is operating significantly over its intended capacity.

We observed during our field visits that many staff find it easier and more effective to manage paper-based files because of the complexities and unreliability of the IT systems.

Figure 2F shows the complexity of the current information management environment at CV.

Figure 2F

Existing CV information management environment

Source: VAGO, based on information from CV.

2.6.2 Planned IT reforms

Under the proposed reforms, CV planned to replace old and inefficient IT systems with an Integrated Offender Management System (IOMS). This system was intended to help case managers work more efficiently and allow CV to rationalise and then decommission its fragmented IT systems.

The preferred option for an IOMS was an off-the-shelf product that is being used in other jurisdictions. It was intended to act as a single source of accurate data about offenders that could be quickly accessed, updated and shared.

However, CV did not secure funding for the IOMS so it is now taking steps to update the legacy E-Justice system. CV will continue to seek funding for the IOMS in future budget rounds.

2.7 Improving CV's business processes

A 2014 study of CV's internal processes showed that 28 per cent of staff time was spent on activities that added 'no value'. CV has taken steps to improve its efficiency, by reducing paperwork, but further work is needed.

CV advised us that it will engage a contractor in March 2017 to examine its new service delivery model and identify ways it could improve its processes.

The CCS internal review also recommended that CV review its processes to allow staff to use more professional judgement in their work. CV developed new practice guidelines in January 2017 that will remove unnecessary administration. Training for new and existing staff will use these streamlined guidelines, in preparation for the new service delivery model.

2.8 Engaging stakeholders

CV works with a range of other agencies—including the courts, the Department of Health and Human Services, Victoria Police and community agencies—to ensure the safety of the Victorian community. CV has engaged well with most of its stakeholders, and it uses multiple forums to coordinate and communicate with them.

Working with the courts

CV is changing the way it delivers its services to reduce unnecessary interactions with low-risk and some moderate-risk offenders. However, there is no evidence that CV specifically consulted with the courts when it planned this new approach. This was a missed opportunity for CV to receive input from an important stakeholder.

CV is now engaging with the courts to develop its court assessment and prosecution training sessions, as part of the CCS reform program. CV is also working with the Chief Magistrate to discuss potential reforms to its services.

More effective consultation with the judiciary by CV, particularly while planning its activities and implementing projects, would be an opportunity to:

- identify potential problems and strategic solutions

- eliminate misunderstandings

- manage stakeholders' expectations

- minimise risks.

Expanding the Neighbourhood Justice Centre model

In recent years, Court Services Victoria (CSV) has sought government support to incorporate elements of the Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC) model into other locations in the state. The benefits of the NJC model are further discussed in Part 3 of this report.

CV was not involved in this proposal, even though it may have had an impact on CV's operations, because CV is a service provider to the NJC at other proposed sites. CV's reason for not getting involved was because CSV is an independent entity and is not part of the Department of Justice and Regulation. CV told us that as NJCs are standalone courts with 'wraparound' services that are not part of the general CCS service system. However, this was a lost opportunity to share innovation across the corrections system.

3 Managing offenders

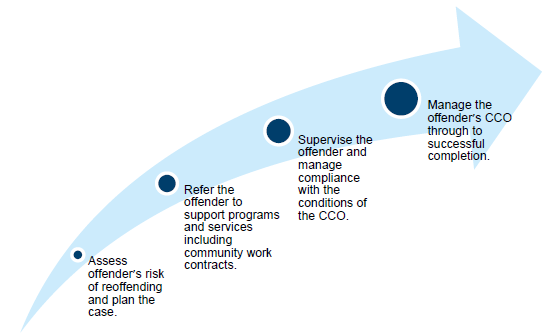

Effectively managing offenders who are serving sentences in the community starts with an accurate and timely assessment of their risk of reoffending, as well as the factors that contribute to their criminal behaviour.

Case managers work with offenders to address these risks by providing support and supervision, addressing underlying issues, and ensuring compliance with the conditions of their community correction order (CCO). This support includes timely access to rehabilitation and community work programs if they are ordered by the courts.

If offenders do not comply with their CCO conditions, there needs to be an efficient process to encourage compliance and completion of the CCO. This process needs to include an option to send offenders back to court, especially when risks of reoffending are high.

Various stakeholders are involved in managing offenders—including case managers, service providers, the courts, police and community organisations—who all work together with offenders to reduce risks of reoffending.

This Part outlines the current shortcomings in managing offenders on CCOs.

3.1 Conclusion

Current practices for managing offenders are not effective due to the overwhelming number of offenders and the lack of trained staff. Inefficient business processes and a poor information environment further worsen the situation.

Because Corrections Victoria (CV)

is not assessing offenders'

CV could minimise these issues by effectively implementing the reforms program recommended in the Department of Justice and Regulation's 2015 Review of Community Correctional Services: CCS review and reform program (CCS internal review) and by validating its risk assessment tool. CV is in the early stages of a validation exercise, which is expected to be completed by December 2018.

To minimise risks to the safety of the community, CV needs to review the process for managing offenders who do not comply with the conditions of their CCO, in particular, the process for sending offenders back to court. This is particularly important because of the growing number of high-risk offenders on CCOs. CV needs to improve its communication with Victoria Police about offender risks.

The Neighbourhood Justice Centre (NJC) provides a highly integrated model for effectively managing offenders on CCOs. This includes collocation of a range of services at court including CCS, active judicial monitoring and effective integration of all support and services. CV is trying to incorporate elements of the model into its services, but there is no collaboration between CV and Court Services Victoria (CSV) to further explore potential synergies in the two offender management models.

3.2 Case management

More high-risk offenders on CCOs, an increasing number of offenders on CCOs overall, and a lack of resources have meant that CV is under intense pressure and has not been able to effectively manage all offenders on CCOs.

CV's current case management of offenders is not effective. CV's case management process is outlined in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A

Case management of offenders

Source: VAGO, based on information from CV.

3.2.1 Staffing issues and inefficient information environment

As discussed in Part 2, CV is significantly understaffed, which means case managers are dealing with excessive case loads. Having staff who lack work experience or sufficient training before they begin working with offenders has also compromised the quality of CV's case management work.

CV's complex, fragmented and inefficient information systems reduce the effectiveness of case management by giving case managers a further administrative burden. The reforms recommended in the Department of Justice and Regulation's 2015 Review of Community Correctional Services: CCS review and reform program (CCS internal review) aim to address understaffing, but there is no funding to improve CV's information system, meaning the current inefficiencies will continue.

3.3 Assessing offenders' risk of reoffending

Effective management of offenders relies on robust risk assessments. The way an offender's case is planned and managed is based on this risk assessment, making it critically important that risk assessments are timely and accurate.

3.3.1 Compliance and quality of risk assessment tools

CV uses a suite of risk assessment tools to determine an offender's risk of reoffending. However, it only completes full risk assessments within the required six-week time frame in 55 per cent of cases, which increases potential risks to the community. There are also concerns about CV staff using the risk assessment tool effectively for appropriate risk assessments.

CV uses the Level of Service (LS) suite of tools, which are used throughout the corrections system. The LS tools replaced the Victorian Intervention Screening Assessment Tool (VISAT) in January 2015. Due to various shortcomings, the VISAT tool was under-assessing offender risks.

The LS tools are described in Figure 3B.

Figure 3B

Purpose and application of LS suite of risk assessment tools

LS Inventory— Revised: Screening Version (LSI-R:SV) |

Purpose—to provide a quick initial risk assessment. Process—CCS staff complete an LSI-R:SV when the offender is being assessed in court, unless the court requests a full pre-sentence report. Compliance—97 per cent of required LSI-R:SV risk assessments are completed. |

|---|---|

LS—Risk Need Responsivity (LS/RNR) |

Purpose—to provide a detailed risk assessment following the initial screening. Process—CCS staff complete an LS/RNR for medium‑ and high-risk offenders or when a court requests it. For medium- and high-risk offenders, the LS/RNR is repeated annually. Compliance—only 55 per cent of required LS/RNR risk assessments are completed. |

Note: This process applies to offenders who received a court order on or after 20 January 2015, including Commonwealth and interstate orders.

Source: VAGO, based on information from CV.

CV's Offender Management Development Branch reviews the ongoing quality of risk assessments. CV plans to introduce a requirement for internal reporting on risk assessments to help improve the rate of completion.

A recent internal management report at CV raised concerns about the accuracy of risk assessments and the consistency of how the tools are applied. CV continues to educate staff responsible for risk assessments to improve the way they use the risk assessment tools.

3.3.2 Validation of the risk assessment tool

CV is in the early stages of a two-year project to validate the accuracy of the LS risk assessment tools. CV has developed a plan for this proposed project.

Completion of this validation project will help CV assess the accuracy and consistency of risk assessments done by staff and assess whether the LS‑RNR tool is fit for purpose and helps in reducing risks to community safety.

3.4 Support programs and services

Increasing demand for support programs and services means that offenders may face significant wait times before they can access support. This is concerning, as timely access to support programs and services reduces the risk of offenders on CCOs committing further crimes.

Increasing demand for rehabilitation and treatment

CCS faces a difficult task in meeting the growing demand for support programs and services, in an environment of constrained resources, particularly when offenders on CCOs have to compete with other members of the community to access services.

As part of a CCO, courts may specify that offenders participate in treatment for mental health problems, attend alcohol and other drug (AOD) programs, attend offending behaviour programs (OBP), do unpaid community work, or a combination of these.

Government and non-government providers deliver these services. Figure 3C shows the conditions imposed on offenders as part of their CCOs in 2015–16.

Figure 3C

Conditions included in CCOs, 2015–16

Condition |

Number of orders |

Percentage of total orders |

|---|---|---|

Community work |

11 835 |

69.7 |

AOD treatment |

14 476 |

85.1 |

Mental health |

8 727 |

51.4 |

OBPs |

9 602 |

56.5 |

Supervision |

10 455 |

61.5 |

Note: These figures show the total CCOs registered for 2015–16 and not data at a certain date. One CCO can include multiple conditions.

Source: VAGO, based on data from CV.

There has been a significant increase in the number of conditions attached to CCOs over the past few years, with the AOD condition now attached to more than 85 per cent of all CCOs.

3.4.1 Mental health programs

The Victorian Government's 10-year Mental Health Plan, released in November 2015, acknowledged the over-representation of people with mental health problems in the justice system—as offenders, victims, and people in need of assistance.

Currently, mental health treatment available for offenders tends to focus on improving their personal mental wellbeing, but it does not necessarily address their criminal behaviour. Most offenders are referred to a mental health specialist by their family doctor. If eligible, they are entitled to 10 visits to a psychologist that are subsidised by Medicare.

This approach is problematic because some offenders are not eligible for referral to a specialist—when they are referred for further treatment, they may not be able to afford the cost so they do not take part in the program.

The CCS internal review proposed two recommendations to address this issue:

- Use senior mental health clinicians at court to properly assess the need for a mental health condition on a CCO, to inform CCS court assessments and advise the judiciary. This pilot has run in two Magistrates' Courts—Sunshine and Melbourne—and early indications are that it has substantially reduced the number of CCOs with a mental health treatment condition. The average reduction over the nine-month period was approximately 44 per cent compared to the control sites.

- Partner with the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) and community health services to develop referral pathways and priority access to bulk-billed care and mental health plans delivered by psychologists with forensic experience. This program did not receive funding in the most recent State Budget, so it is currently on hold.

CV and DHHS are also developing the Forensic Mental Health Implementation Plan to better align elements of the criminal justice and mental health systems. The plan will consider ways to give more timely and effective assessment and treatment to offenders with mental illness and people whose behaviour has led to, or could lead to, criminal offences.

Lack of access to services to enable offenders to fulfil the conditions of their CCOs is a significant concern. Further steps are needed to develop a permanent and viable solution to meet this gap in service provision.

3.4.2 Alcohol and other drug programs

According to the Sentencing Advisory Council, in 2015, 74.3 per cent of all CCOs imposed by the Magistrates' Court and 87.9 per cent imposed in the higher courts included a condition for AOD assessment and treatment.

We observed that average wait times for a suite of AOD programs were quite high, ranging from 13 to 22 days—with maximum wait times ranging from 56 to 218 days.

The increasing complexity in the range of offenders on CCOs is also increasing the demand for AOD treatment, with 1 200 of the total 8 355 forensic referrals—or 14.4 per cent—being sex offenders or violent offenders, or both. Only 46 per cent of forensic clients completed an episode of treatment in 2015–16. CV told us that an offender may fail to complete one episode of treatment but may complete a subsequent episode of treatment. However, CV did not have data available to demonstrate this.

The Australian Community Support Organisation (ACSO) is contracted by DHHS to monitor and track offenders' attendance and treatment progress in AOD programs. ACSO refers offenders to service providers, who record attendance and case information, which CCS case management staff can access. Every three months, ACSO also gives aggregate data to CV and DHHS to help them make decisions about AOD services.

As part of the reforms recommended in the CCS internal review, CV and DHHS have established a joint project to:

- increase the focus on addressing criminal behaviour in AOD treatment programs to meet the needs of offenders on CCOs

- explore options to improve integration between AOD and mental health treatment pathways.

Funding of $4.7 million in 2015–16 and $5.25 million in 2016–17 was allocated to expand these assessment and treatment programs. The 2016–17 funding also includes the rollout of a three-hour AOD education program for low-risk offenders, which is consistent with CCS's approach of focusing more intensive services on those identified with a medium or high risk of reoffending.

Wait times for alcohol and other drug programs

DHHS uses the Community Offender Advice and Treatment Service (COATS) to arrange AOD treatment programs through a network of community-based providers. The average wait times for treatment through the COATS are shown in Figure 3D. There are no benchmarks or targets associated with these programs, but longer wait times increase the risks of reoffending, especially in the case of high-risk offenders.

Figure 3D

Wait times for AOD programs and services, 30 June 2016

| Programs | Wait time (business days) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

Average |

Minimum |

Maximum |

|

Care and recovery coordination |

19 |

5 |

61 |

Counselling |

21 |

2 |

218 |

High Risk Offenders Alcohol and Drug Service (HiROADS) |

22 |

6 |

76 |

Koori community AOD programs |

17 |

1 |

70 |

Outreach and care coordination |

17 |

1 |

61 |

Residential rehabilitation |

13 |

1 |

56 |

Withdrawal |

15 |

2 |

77 |

Other |

21 |

1 |

68 |

Source: VAGO, based on data from CV.

3.4.3 Offending behaviour programs

Courts can order offenders to attend OBPs run by CV in prison or in the community. OBPs are delivered by both in-house staff and contracted service providers.

Wait times for offending behaviour programs—initial screening

The current CV OBP service delivery model requires that all serious violent offenders and 80 per cent of general offenders receive a service—which range from OBP screening only (in instances where the offender is found unsuitable for further assessment) to intervention and completion of OBPs. A recent OBP monitoring report highlighted long wait times:

- In March 2016, 1 803 CCS offenders were on the priority wait list for initial screening.

- Of these, 281 were serious violent offenders and 40 per cent of them had been on the screening priority list for more than three months.

- More than half of the assessments (including both prisons and CCS) take longer than 40 days to complete from the date of the initial screening.

Excessive wait times could also result in offenders receiving no intervention at all as they become ineligible for OBPs if they have less than six months remaining on their CCOs.

3.4.4 Community work

Unpaid community work is one of the most common conditions that courts impose on offenders on CCOs. CV manages a large community work program and it has some innovative programs run in different locations. However, many offenders are waiting to be given a community work placement.

Community work gives offenders an opportunity to make recompense to the community affected by their offences. Work can be done as part of a work crew, with tasks such as painting over or removing graffiti, maintaining parks and gardens, helping with repairs following natural disasters, or participating in programs tailored to an offender's interests or that can help them to develop vocational skills.

Coordinating the community work program is challenging, because the nature of some offenders' criminal behaviour makes them unsuitable for certain programs. Another challenge is getting the right mix of people within a work crew—the benefit of working and contributing to the community can easily be lost if offenders working together are extending or consolidating their criminal networks.

The proposed CCS reforms include making the community work function a specialist work stream, to attract job applicants with a background in community development.

Community work placements

Before offenders can complete community work, they need to be given a placement. Currently, a significant number of offenders do not have a placement for their community work. CV told us that the reasons for not having a placement include:

- lack of available contracts or service providers

- competition with other programs such as the Australian Government's Work for the Dole scheme

- lack of CCS staff to manage offenders

- offenders not having reported to CCS yet

- offenders being previously contracted but having withdrawn for some reason

- medical issues.

A report from early November 2016 showed that 12.3 per cent of offenders had not been contracted to a community work placement and another 12.6 per cent of placements for offenders on CCOs were cancelled or withdrawn without a reason being recorded.

Providing sufficient and appropriate opportunities for the growing number of offenders on CCOs is an ongoing challenge for CV.

3.5 Managing compliance with CCOs

Compliance requirements for offenders on CCOs are outlined in the Sentencing Act 1991 and also in each offender's individual order conditions.

3.5.1 Completion rates

The completion rate for CCOs in Victoria is the second lowest in all Australian jurisdictions as shown in Figure 3E.

Figure 3E

Completion of CCOs, by type of order, 2014–15 (per cent)

Type of order |

NSW |

Vic |

Qld |

WA |

SA |

Tas |

ACT |

NT |

Aust |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Reparation |

79.0 |

72.7 |

81.6 |

66.4 |

51.8 |

81.8 |

60.4 |

73.9 |

76.6 |

Supervision |

75.0 |

59.9 |

69.6 |

59.4 |

72.9 |

92.1 |

82.2 |

66.4 |

70.9 |

All orders |

75.8 |

66.5 |

75.6 |

61.2 |

67.5 |

87.6 |

79.9 |

69.0 |

72.9 |

Source: VAGO, based on data from Report on Government Services 2016, Productivity Commission.

We observed that case managers use their skills, networks and experience to help offenders complete their CCOs.

However, significant workloads make it difficult for case managers to make sure they promptly manage offenders who do not comply with their CCO conditions. An internal brief written after a CCO offender committed a serious crime highlighted that 'extreme case load pressures could lead to delays in initiating contravention proceedings'.

3.5.2 Managing noncompliance

CV's options for managing offenders who do not comply with CCOs are described in Figure 3F.

Figure 3F

Options for managing noncompliance with a CCO

Source: VAGO, based on information from CV.

The process for managing offenders who have not complied with a CCO is a court process based on principles of procedural fairness and rules of evidence. This means that any allegations of noncompliance need to be proven beyond reasonable doubt. This process requires significantly more time than the equivalent process for parolees who breach their parole conditions—because they are still under a prison sentence, they can be swiftly returned to prison.

CV told us that it expects its new service delivery model and case management approach to improve the timeliness of noncompliance procedures, despite the court process being the most time-consuming aspect of managing noncompliance.

While we were conducting this audit, CV was developing options for the government to speed up noncompliance hearings in cases where the risk of the offender reoffending posed a risk to the safety of the community.

CV needs to rigorously review the overall noncompliance process to make it more timely and efficient, which will reduce the risk to the community.

3.5.3 Sharing information with Victoria Police

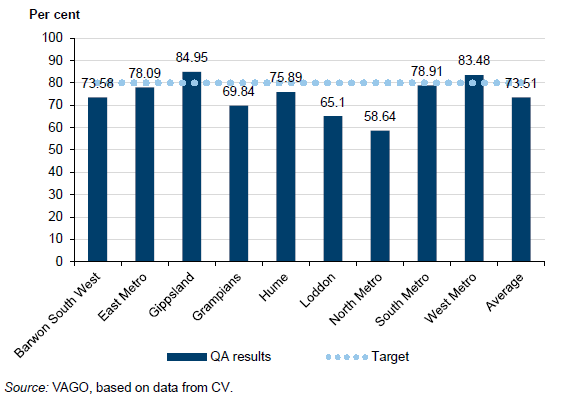

CV's multiple information technology (IT) systems make managing information a complex process. Sharing information with Victoria Police about offenders is essential for effectively managing offenders who have not complied with their CCOs.