Managing Victoria’s Native Forest Timber Resources

Overview

This audit examined whether Victoria’s native forest timber resources on public land are being managed productively and sustainably.

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI), VicForests and the Department of Treasury and Finance are managing the timber resources in a productive way that delivers socio-economic benefits to regional communities. VicForests has demonstrated that its commercial decisions balance the need for

long-term economic returns with the need to support a sustainable industry.

DEPI and VicForests demonstrate many environmentally, socially and economically sustainable practices in managing Victoria’s native forest timber resources. However, DEPI is not effectively delivering its approach to protect forest values, and needs to improve the way it documents decisions affecting where harvesting can occur. VicForests can further improve the way it estimates the sustainable harvest level.

It is not clear whether the agencies have made suitable progress or achieved the desired outcomes in sustainably managing the timber resources—such as protecting endangered species from harvesting impacts—because DEPI has not had the measures, monitoring and data to do this. It has recognised this issue and is addressing it.

Managing Victoria’s Native Forest Timber Resources: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER December 2013

PP No 289, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Managing Victoria's Native Forest Timber Resources.

This audit examined whether Victoria's native forest timber resources on public land in eastern Victoria are being managed productively and sustainably.

I found that the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) and VicForests are managing the timber resources in a productive way that delivers socio-economic benefits to regional communities and some financial payments to the state. VicForests has demonstrated that its commercial decisions balance the need for long-term economic returns with the need to support a sustainable industry.

DEPI and VicForests demonstrate many environmentally, socially and economically sustainable practices to fulfil their roles in timber resource management. However, DEPI is not effectively delivering its approach to protect forest values, and needs to improve the way it documents decisions affecting where harvesting can occur.

I could not assess whether the agencies had made suitable progress in sustainably managing the timber resources or if they had achieved the desired outcomes, such as protecting endangered species from harvesting impacts, because DEPI has not had the measures, monitoring and data in place to assess this. It has recognised this issue and is addressing it.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

11 December 2013

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Dallas Mischkulnig—Sector Director Catherine Sandercock—Team Leader Melissa Watson—Analyst Karen Pitt—Analyst Chris Sheard—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Forests provide innumerable benefits to Victorians, including conserving of flora and fauna, protecting water catchments and water supply, providing timber for sustainable forestry, protecting archaeological and historic values, and providing recreational and educational opportunities. Given that only around 50 per cent of the forests present in Victoria prior to European settlement still remain, the government has an important responsibility to manage the remaining forests for the benefit of our environment and for all Victorians, now and into the future.

In this audit, I examined how the government manages the systems in place to deliver sustainable timber resource management outcomes, how well they are operating and what they are achieving. Timber harvesting is an important and productive use of Victoria's state forest timber resource, but is accompanied by challenges and can have serious impacts on the sustainability of the forests.

The timber resource is being used productively but the environmental, economic and social sustainability of timber resource management can be further improved. The audit found weaknesses in how state forest values are protected and managed as well as weaknesses in the monitoring and measurement processes and data around sustainable state forest management. Achieving a sustainable balance between the different uses that can occur in state forests, including timber harvesting, will remain a challenge. Agencies will need to continue to appropriately evolve and respond to changing circumstances, such as future bushfires and market competition.

I am encouraged that the collaboration between Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI), Department of Treasury and Finance and VicForests is continuing to develop. Together they are reviewing and considering opportunities for the improved sustainable use of the forests and timber production. I am also encouraged by DEPI's planned way forward for threatened species and public land management, which I will be closely monitoring and may come back and review in the future.

I have made 11 recommendations that will assist the agencies in better managing Victoria's native forest timber resources. It is pleasing that the agencies have accepted and committed to implementing my recommendations, but at this stage DEPI has not advised the specific actions to be taken or time frames for implementation. I will follow this up with the department over the next three months.

I would like to thank agency staff for their assistance and cooperation during this audit, and I look forward to receiving updates on their progress in implementing the recommendations.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

December 2013

Audit Summary

Victoria aims to manage its 7.14 million hectares of native forest on public land sustainably. While over half of this land is conservation parks and reserves, around 3.14 million hectares is state forest. In addition to conservation, state forests allow for a range of uses including timber harvesting and mineral extraction, in accordance with ecologically sustainable development principles.

Around 1.82 million hectares of state forest is available for timber harvesting. Between 2007 and 2013, an average of 5 000 hectares of this was harvested each year in eastern Victoria. Native forest timber harvesting has generated around $1 billion in revenue for VicForests since 2004.

Good management of timber resources is needed to preserve both the environmental heritage of Victoria and the communities the timber industry sustain.

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) is responsible for sustainably managing all public forests, including state forests, and for regulating timber harvesting. DEPI also supports the Minister for Agriculture and Food Security in his governance responsibilities over VicForests. VicForests is responsible for managing, harvesting and selling public native timber in eastern Victoria. The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) supports the Treasurer in his role as the sole shareholder of VicForests and oversees its commercial and financial performance.

This audit examined whether DEPI and VicForests are managing native forest timber resources on public land productively and sustainably and whether DEPI and DTF are fulfilling their oversight and advisory roles adequately.

Conclusions

Victoria's timber resources are being managed productively. However, the environmental, social and economic sustainability of timber resource management could be enhanced by improving the way DEPI protects forest values, documents decisions affecting where harvesting can occur, and manages its backlog of forest regeneration from before 2004. VicForests can also improve its process for estimating sustainable harvest levels.

DEPI has not had the measures, monitoring and data to show what its activities are achieving, or how forest health and the condition of other forest values are faring over time. It is now working to address these gaps.

VicForests and DEPI need to build on the strengths of their current collaborative approach, measure progress and continue to adapt their management of Victoria's timber resources to meet and respond to foreseeable future challenges and pressures.

Findings

Is there adequate progress towards sustainability goals?

Gaps in DEPI's state forest and timber resource management performance reporting make it difficult to assess how well DEPI's and VicForests' efforts are contributing to sustainable outcomes.

There are regional goals for sustainable state forest management but no overarching goal. There are no regional objectives, performance measures and targets but these are needed so that DEPI can measure the progress and success of its state forest management activities. DEPI is developing a new approach to public land planning and intends to develop regional objectives, measures and targets as part of this process. It will also need to develop an overarching goal for state forest management.

DEPI also has goals and objectives for sustainable timber resource management. VicForests develops corporate objectives, measures and targets aligned with these. Its reporting on them demonstrates VicForests' achievements in improving sustainable timber harvesting management over time.

However, until recently DEPI's measuring and monitoring to assess progress in achieving forest and timber management objectives and goals was weak and lacked reliable data. It is taking important steps towards addressing this by establishing new forest monitoring and improved data collection.

DTF and DEPI manage their roles in supporting the Minister for Agriculture and Food Security and the Treasurer well. The Treasurer, as the shareholder of VicForests, receives regular, formal communication, and DTF reviews VicForests' corporate plans and quarterly financial reports. DEPI appropriately supports the minister in overseeing VicForests by monitoring its corporate governance, compliance with legislative obligations and commercial functions. DEPI is further clarifying the respective roles and responsibilities of the agencies involved in the native timber industry.

Is timber being harvested at a sustainable rate?

DEPI has an established process for deciding where in the forest harvesting can occur and uses its forest management zoning scheme to define these areas. However, there is limited transparency of the assessments DEPI has made when making decisions to amend the forest zoning, and it has not adequately reviewed the scheme over time. This means there is uncertainty about the extent to which the current harvesting areas are consistent with DEPI's harvesting and conservation objectives.

VicForests is harvesting at or within its estimated sustainable harvest level, and harvests less than the area that DEPI allows it to. VicForests continues to improve its largely effective approach for estimating the sustainable harvest level, although there are a number of ways it can improve its 20-year planning for where and when to harvest. It is also well placed to continue to modify its approach over time as circumstances change.

Is harvesting being managed to protect forest values?

DEPI has designed a suite of measures and plans to limit the impacts of activities such as harvesting on forest values. These include setting aside conservation areas, allowing harvesting only in a small proportion of the forest, and specific actions to manage animal and plant species threatened by harvesting and other activities.

DEPI's effectiveness in protecting forest values from harvesting is reduced because it has failed, in some cases, to develop the plans needed to do this, and in many cases it has failed to track and review the progress made and the results achieved.

Until recently, DEPI's measurement of how well forest values are being maintained over time was poor, making it difficult for it to provide assurance about how well values are being protected. The comprehensive forest monitoring program it introduced in 2010 and additional data it is currently collecting are aimed at addressing this gap.

VicForests is meeting its responsibilities to limit the potentially adverse impacts of harvesting on forest values. It has developed a system of management plans and actions to do this, in line with the purposes and principles of the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004. Its effectiveness is confirmed by external audits of its operations by DEPI, and its independent certification to the Australian Forestry Standard.

DEPI and VicForests have designed their management approaches to protect biodiversity values in a precautionary way. As part of this, they each need to improve and better document the way they assess the threats and consequences associated with biodiversity management decisions in harvesting areas and develop more transparent processes in managing the risks and trade-offs involved.

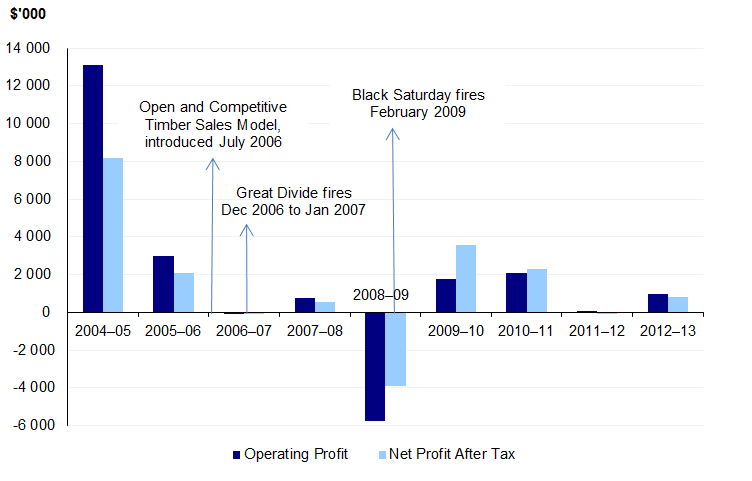

Is harvesting profitable and supporting regional communities?

VicForests' commercial activities demonstrate that it balances the need for long-term profits with the need to support a sustainable industry. It has generated profits in most years and since its inception has paid dividends to the state twice. Its activities generate considerable direct and indirect socio-economic benefits for regional communities.

DEPI and VicForests are working with the industry and other agencies to identify and respond to the current economic and environmental challenges facing the industry, particularly in East Gippsland. VicForests has also carried out strategic planning for longer-term, profitable and sustainable forest use that can continue to support regional communities, but DEPI's long-term planning is not sufficiently holistic or proactive.

Recommendations

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries:

- strengthen its sustainable state forest and timber resource performance management by:

- setting a clear goal for state forest management

- establishing regional objectives, progress measures and targets for state forests that take into account both forest and timber resource management

- reporting publicly on progress in achieving these

That VicForests:

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries and VicForests:

- improves the way it manages the forest management zoning scheme, by:

- reviewing the forest management zoning for eastern Victoria by March 2015 as planned, documenting its approach and the trade-offs made between conservation needs and productive uses

- better documenting the assessments underpinning amendment decisions and periodically reviewing how consistently it applies its zoning amendment process

- engages appropriate experts to oversee its future five-yearly audits of VicForests' sustainable harvest level planning—with expertise spanning the environmental, social, economic and commercial dimensions of sustainability

- improves the way it manages its responsibilities for regenerating forest, and monitors VicForests' regeneration compliance, by:

- prioritising the regeneration of its backlog, to the accepted standards

- collecting enough seed to meet regeneration backlog and bushfire recovery needs

- reconciling VicForests' regeneration against harvested areas

- improves its delivery of forest-related plans and strategies through timely and comprehensive planning, monitoring and review, including:

- completing, reviewing or renewing the action statements required under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988

- strengthening its business systems so that the delivery, monitoring, reporting and review of its commitments for managing forest values is consistent, thorough and timely

- uses its recent biodiversity research findings to:

- further analyse the impacts of harvesting on at-risk species to determine whether any changes to management approaches or interim measures are needed

- inform its reviews of forest management zoning and action statements and its development of the new integrated regional plans

- strengthen its auditing of VicForests' compliance by documenting the rationale underpinning its identification of the high compliance risks associated with harvesting, and mandating the audits

- more strategically and holistically assess options for addressing issues and opportunities for the industry, and continue to update this planning based on socio‑economic information relevant to the native forest timber industry sector.

- continues to improve its approach to scheduling the sustainable harvest level to address identified weaknesses

- clearly and accurately reconciles its successfully regenerated areas against the area harvested and reports this publicly.

- improve and better document the assessment of threats and consequences that biodiversity management decisions in timber production areas may have on forest environmental, economic and social values, and more transparently manage the risks and trade-offs involved.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Environment and Primary Industries, the Department of Treasury and Finance and VicForests with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Victoria has around 7.1 million hectares of native forest on public land. Native forests contain plants and animals that are endemic to the area, and provide a wealth of environmental, economic and social benefits to the state. Around 4.0 million hectares of this is forest conservation areas, also known as wilderness, state and regional parks and reserves. These areas are primarily used for conservation, supporting biodiversity, water quality, carbon storing, and provide other values such as recreation.

The remaining 3.1 million hectares is state forest. State forests must be managed to maintain forest values. These include:

- environmental conservation—e.g. biodiversity, forest health, water quality

- productive uses—e.g. timber production, honey, firewood

- social and economic values—e.g. recreation, cultural sites, employment.

There is potential conflict between some of these values—for example preserving biodiversity and allowing for productive uses that disrupt the natural environment, such as harvesting. Without effective management, timber harvesting can lead to long-term adverse impacts on the forest ecosystem. State forest management needs to balance these competing priorities.

Around 1.82 million hectares, or 58 per cent, of state forests is available for timber harvesting. As shown in Figure 1A, in recent years an average of 5 000 hectares has been harvested annually in eastern Victoria, although this has been declining.

Figure 1A Forest areas, 2013

Area of public native forest |

Total (ha) |

Percentage of public forest area |

|---|---|---|

Area of public native forest |

7 138 000 |

|

Area of state forest |

3 138 000 |

44 |

Area of state forest available for harvesting in eastern Victoria |

1 820 000 |

25 |

Area of state forest available and potentially suitable for harvest in eastern Victoria |

815 000 |

11 |

Area of state forest assessed as currently suitable for harvest in eastern Victoria |

490 000 |

7 |

Average annual harvest area in eastern Victoria |

5 000 |

0.07 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Department of Environment and Primary Industries and VicForests data.

1.2 Sustainable forest management

The aim of sustainable forest management is to manage forests in a way that maintains their biodiversity, productivity and regeneration capacity. It also aims to make forest regions healthier and more productive, taking into consideration the social, economic, environmental and cultural needs of stakeholder groups.

Under the 1992 National Forest Policy Statement, Commonwealth, state and territory governments agreed on broad goals for managing Australia's native forests. The goals support the concept of sustainable forest management. The aim is to conserve biodiversity, heritage and cultural values, and at the same time develop a dynamic, competitive and sustainable forest products industry. This is in line with the Montréal Process—the international framework established in 1994 to monitor, measure, assess and report on national forest trends and management.

Major elements of the national policy include a commitment to develop a comprehensive, adequate and representative reserve system, and implement strategies to conserve those reserve areas. Victoria's reserves system meets this commitment and has the following three components:

- dedicated reserves—forest areas established by legislation specifically for conservation purposes, e.g. national parks, state parks, flora and fauna reserves

- informal reserves—areas of multi-use state forests and other public land that are set aside for conservation through the forest management zoning scheme

- conservation values protected by management rules—areas of multi-use state forests and other public land protected from productive uses such as harvesting, including by using stream buffers and rainforest with a surrounding buffer.

The reserves system, together with harvesting regulations, establishes the basis for providing conservation, water, recreation and timber values.

1.3 Native forest timber resources

Native forests provide a timber resource that has a range of potential uses including harvested products, such as sawlogs and firewood, and unharvested products, such as carbon storage and biodiversity. In Victoria the main use is timber harvesting.

The timber industry is a valuable source of employment in many of Victoria's regional areas, employing over 21 000 people. VicForests' annual reporting states that its native forest timber harvesting in eastern Victoria has generated around $1 billion in direct economic benefits since 2004. Ineffective management of timber resources may affect employment within the sector, which has associated socio-economic impacts.

Commercial activities—mainly timber harvesting—are restricted to specific areas of state forests. Much of the timber harvesting in western Victoria ceased in the 2000s and the main timber harvesting today occurs in eastern Victoria. There is currently minimal commercial harvesting of native timber on private land.

1.3.1 Timber types and products

Victoria's native forest timber industry produces sawlogs, which are used for a variety of wood products in the furniture, flooring and construction industries. The timber industry also produces lower quality logs, which are used for pulp and paper production and firewood.

The sawlog industry depends largely on the ash forests, found at higher elevations in Gippsland and north-eastern Victoria. The other source of sawlogs is mixed-species forests, which tend to produce lower quality timber compared with ash forests. Mixed‑species forests are usually composed of at least two eucalypt species and occur widely throughout Victoria's native forests.

Mixed-species forest

When these forests are harvested for sawlogs, there are always parts of the tree that are not sawlog quality—e.g. branches and upper trunk—and trees felled that are not suitable for sawlogs either—e.g. too young or too knotty. This is referred to as 'residual timber' and equates to around two-thirds of the volume harvested. Residual timber is predominantly used for pulp and paper production, with a small amount sold for firewood.

VicForests supplies timber harvested from eastern Victoria to approximately 20 mills across Victoria for processing sawlogs. The largest 10 mills process around 90 per cent of this timber.

Residual timber is primarily processed into pulp at Australian Paper's mill in Maryvale, Gippsland. Some residual timber is also processed into woodchips for export to pulp and paper manufacturers, particularly in Japan.

1.3.2 Harvesting process

Timber harvesting involves a cycle from planning the harvest through to regenerating the harvested area so that the forest will regrow.

The planning processes estimate how much of the available forest can be harvested sustainably. The forest area to be harvested is divided up into smaller harvesting areas called coupes, which are marked and surveyed before being harvested.

The branches and upper trunk are removed at the coupe and the trunks are graded as high- or low-grade sawlogs, or pulp logs. They are then hauled to designated mills. The logs are tracked from forest to mill using a barcode system.

Once harvesting is complete, the aim is to regrow the forest to resemble the forest before harvesting. The coupes are prepared and sown with tree seeds similar to the original species composition.

1.4 Victoria's framework for sustainable forest management and timber harvesting

Most of Victoria's native forests are managed under five 20-year regional forest agreements, which cover sustainable forest management and sustainable forest industries. These agreements were established with the Commonwealth Government between 1997 and 2000 to implement the 1992 National Forest Policy Statement. They guarantee wood supply for the timber industry while also creating a system of forest conservation reserves—including national parks and other protected areas. The Commonwealth Government coordinates a national approach to environmental and industry issues, while Victoria is responsible for managing the forests.

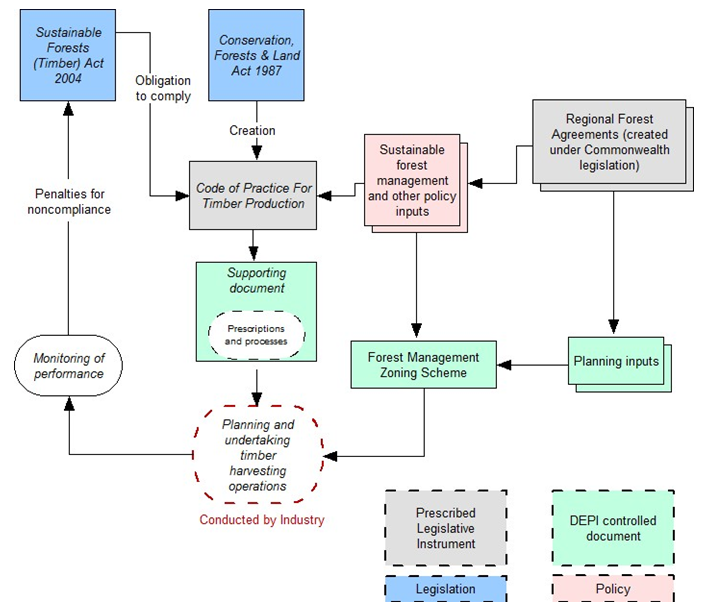

A range of state legislation governs forest management and timber harvesting in Victoria and specifies the areas of state forests that are subject to commercial activities. This legislation is supported by various guidelines that require forest management and timber harvesting to be managed sustainably—as shown in Figure 1B. The legislative focus for this audit is the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004 (the Act).

Figure 1B

Framework for sustainable forest management

and sustainable timber production

Source: Department of Environment and Primary Industries.

Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004

The Act requires the Minister for Agriculture and Food Security to allocate areas of state forest to VicForests for harvesting through an allocation order. Recent changes to the Act include:

- removing the time limit on the allocation, and allowing contracts of up to 20 years or longer under some circumstances

- no longer requiring VicForests to develop rolling five-year timber release plans that identify where it will harvest under the allocation order

- removing timber harvesting operator licence regulations, as they duplicate existing health and safety and environmental regulations.

Sustainability Charter for Victoria's State forests

Under the Act, the 2006 Sustainability Charter for Victoria's State forests binds the Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) and VicForests to meeting environmental, socio-economic and governance objectives consistent with the Montréal Process.

Regional forest management plans

For state forests in eastern Victoria, four regional forest management plans are used to manage the environmental, social and economic uses and issues relevant to each region. These plans apply three different zones to manage the types of activities allowed across the forests.

Action statements

Produced under the Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988, these statements are developed to conserve and manage threatened species and communities and can include requirements for how timber harvesting is conducted.

Environmental regulatory framework

The environmental regulatory framework consists of:

- harvesting requirements set by forest management plans, zoning and action statements

- the Code of Practice for Timber Production, which sets standards for timber production to manage environmental, social and cultural impacts from timber production and harvesting activities

- a set of management procedures providing technical standards and guidance in applying the code, forest management plans and action statements.

Timber Industry Action Plan

In addition to these legislative and regulatory instruments, the 2011 Timber Industry Action Plan (TIAP) is the Victorian Government's plan for assisting the timber industry to be productive, sustainable and meet its key challenges. These challenges include a lack of resource security, the drop in Japanese demand for woodchips, the impact of wildfires and an increased amount of forest in conservation reserves.

1.5 Roles and responsibilities

The Minister for Agriculture and Food Security is accountable for sustainable timber harvesting, and is the relevant minister overseeing VicForests. The Minister for Environment and Climate Change is responsible for sustainable forest management. The Treasurer is VicForests' sole shareholder.

This audit looked at the activities of three agencies.

VicForests

VicForests was established in 2003 and in 2004 became responsible for managing and selling native forest timber resources and delivering long-term returns to the state. VicForests manages the commercial sale and supply of timber resources from Victorian state forests east of the Hume Highway. Through the Act, its Order in Council (2003) and the TIAP, VicForests is required to:

- estimate the available timber resources

- sell the harvested wood to timber mills through an open and competitive system

- manage the contracts with harvest and haulage operators to cut and deliver the timber to the mills

- manage forest regeneration.

Department of Environment and Primary Industries

DEPI has several responsibilities, which include:

- managing the forest estate—including forest management planning, biodiversity management, and monitoring and reporting on sustainable forest management

- regulating commercial forest uses—including timber harvesting across the state

- developing policy for forest industries

- managing the allocation and vesting of timber harvest areas to VicForests

- monitoring, along with the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF), VicForests' corporate governance, compliance with legislative obligations and commercial functions

- managing the limited commercial timber operations in state forests in western Victoria

- managing public safety zones for timber harvesting operations across the state.

Department of Treasury and Finance

DTF undertakes functions on behalf of the Treasurer as the shareholder of VicForests. It monitors the financial performance of VicForests and oversees VicForests' corporate governance, compliance with financial legislative obligations and commercial functions.

Other key roles

The TIAP is predominantly delivered by DEPI, DTF and VicForests. DEPI is the lead agency responsible for delivering the plan. There are 20 other government agencies that also have some role in delivering the plan's actions.

The Native Forestry Taskforce—comprising of senior executives from DEPI, DTF, VicForests and the Chief Executive Officer of the Victorian Association of Forest Industries—is monitoring the implementation of the TIAP priorities and other native forestry election commitments, as well as any outstanding taskforce recommendations. The taskforce can elevate matters and report its findings to the Secretary of DEPI, the Minister for Agriculture and Food Security, and the Minister for Environment and Climate Change.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to determine whether native forest timber resources on public land are being managed productively and sustainably.

The audit examined whether:

- timber is harvested at a level that does not adversely affect the long-term sustainability of the timber resources and the state's native forest environment

- the management of the timber resources optimises its long-term productive and commercial use and the social and economic well-being of regional communities

- agencies responsible for timber resource management work effectively together, have appropriate governance arrangements in place, and their actions and performance are open to public scrutiny as appropriate.

This audit focused on the management of native timber resources on public land. It examined the role of DTF as shareholder, and the following agencies with responsibilities for managing native timber resources:

- DEPI, formerly the departments of Primary Industries, and Sustainability and Environment

- VicForests.

The audit focused on timber harvesting activities in eastern Victoria. The audit did not examine timber plantations or firewood management.

1.7 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted under section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

A forest science specialist was engaged during the audit to provide expert advice on the sustainable management of the timber resource.

The total cost was $490 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

Part 2 examines the performance management arrangements, including measuring and reporting on progress as well as oversight and accountability.

Part 3 assesses the processes for determining where and at what level native forest timber harvesting can occur, and for managing harvesting levels and regeneration.

Part 4 examines arrangements for minimising the potential adverse impacts of harvesting on forest values, such as biodiversity.

Part 5 considers the commercial management of the native forest timber resources, VicForests' financial management and the socio-economic impacts of harvesting.

2 Is there adequate progress towards sustainability goals?

At a glance

Background

Agencies manage performance by setting goals and objectives to describe the desired future state for a sector and how they plan to achieve it, and setting measures and targets to monitor their progress and success in achieving the goals.

Conclusion

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) has an established approach for measuring the progress and achievements of sustainable state forest and timber resource management. The approach lacks an overall goal and progress measures and targets for state forest management activities and, until recently, DEPI has not had the data to show how state forests are faring over time. As a result, it has not sufficiently demonstrated progress in sustainable timber resource and state forest management. DEPI is working to address this.

Findings

- VicForests develops objectives, measures and targets aligned with DEPI's overall approach and uses these to report on its progress and achievements in managing the timber resource sustainably.

- DEPI does not have the regional objectives, measures and targets needed to show the progress and success of timber resource and state forest management.

- DEPI's forest reporting has been hampered by poor data but it has recently introduced comprehensive forest monitoring and improved other data collection methods.

- There is appropriate oversight and accountability for VicForests, but the lack of time lines and progress measures make effective oversight of the Timber Industry Action Plan difficult.

Recommendations

That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries strengthen its state forest and timber resource management and reporting, including setting regional objectives, progress measures and targets.

2.1 Introduction

Sustainable timber resource management, which is focused primarily on timber harvesting, contributes to the sustainable management of state forests.

The Sustainability Charter for Victoria's State Forests 2006 (the sustainability charter) defines ecologically sustainable development as 'development that improves the total quality of life, both now and in the future, in a way that maintains the ecological processes on which life depends'.

Sustainability is not an absolute end point or outcome, and changes in priorities, knowledge and community perspectives will influence how sustainability goals are defined.

To demonstrate progress in both sustainable timber resource management and sustainable state forest management, agencies need to define these goals and the progress they want to achieve, and apply these over an appropriate time period. They also need to define how they will measure progress, collect data to demonstrate progress and report on it.

Responsible agencies also need to have clear roles and responsibilities and their performance should be accountable and open to public scrutiny.

2.2 Conclusion

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI) has an established approach to measuring and reporting performance for sustainable timber resource and state forest management. Complementing this approach, VicForests has set objectives, measures and targets for its sustainable timber resource management. DEPI has set sustainability objectives for state forests but does not have an overall goal describing what it aims to achieve through delivering these objectives. Nor does it have the progress measures and targets needed to demonstrate how its activities contribute to sustainable state forest management.

Until recently, DEPI has not had the monitoring processes and data to show how forest health and the condition of other forest values are faring over time. It is now working to address these gaps.

2.3 Sustainability goals and objectives

Agencies need to set measurable goals that are underpinned by appropriate objectives, and together these should reflect the agency's understanding of what it aims to achieve and how it plans to achieve it.

Sustainable state forest and timber resource management are long-term endeavours. It is important for agencies to set meaningful progress measures linked to the achievement of outcomes and accompanied by realistic time frames.

Sustainable timber resource management

DEPI has set 10-year environmental and cultural goals for timber resource management through the Code of Practice for Timber Production (the Code). The Timber Industry Action Plan (TIAP) priorities provide social and economic sustainability goals relevant to timber resource management, although there is no time frame specified for achieving these.

The sustainability charter sets objectives relevant to both state forest and timber resource management. These encompass the social, environmental, economic and governance aspects of sustainability. VicForests' corporate objectives align with the sustainable charter objectives.

DEPI's state forest management plans set the direction and actions for sustainable management in the different forest regions across the state. The eastern Victorian plans all pre-date the introduction of the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004 (the Act), the sustainability charter and the Code, and therefore do not have objectives that align with these. While the plans remain relevant, this makes it difficult to measure the extent to which VicForests' and DEPI's efforts in managing timber resources are contributing to sustainable state forest outcomes.

DEPI is developing a new, integrated approach to public land planning and has signalled that it will revise the forest management plans as part of this process, including setting regional objectives.

Sustainable state forest management

DEPI has not set an overarching goal for state forest management. Instead, the forest management plans each identify a regional goal for what the plans aim to achieve over a 10-year period. These are due for revision in the eastern Victorian regions.

DEPI should set an overarching goal for state forest management, to which the regional goals would contribute, as this would provide a clearer picture of forest management aims and how its current objectives contribute to this.

DEPI has set objectives for sustainable state forest management through the sustainability charter, although the charter does not make it clear what time frames apply to the achievement of the objectives. As with the timber resource component, the lack of regional objectives in forest management plans makes it difficult to assess how well agency efforts are contributing to sustainable state forest outcomes.

2.4 Measuring and reporting progress

DEPI and VicForests need to measure and report on what their management of the state forests and timber resources is achieving, both individually and collectively.

VicForests develops measures and targets against its corporate objectives and uses these to report on specific sustainable timber harvesting management achievements relevant to its business.

DEPI has developed criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management. However, until recently its measuring and monitoring of sustainable forest management was undermined by the lack of reliable data. This made it difficult to assess progress in achieving forest and timber management objectives and goals.

2.4.1 Sustainable timber resource management

Both DEPI and VicForests contribute to sustainable timber resource management. The Act requires VicForests to develop initiatives and targets to respond to and support the sustainability charter objectives and report on them. There is no similar obligation for DEPI.

VicForests

VicForests, through its corporate planning and sustainability reporting, transparently demonstrates how it has been, and plans to contribute to achieving relevant objectives. It has established initiatives and targets against the sustainability charter, although it does not have targets against every objective.

VicForests' public reporting includes its progress in achieving these targets and other targets it sets against its corporate objectives and sustainable forest management system performance. This reporting indicates it generally achieves good progress. However, its data is not always consistent between years or between different reports—for example, regeneration information does not reconcile between reports, and reporting does not consistently identify risks or how they have been managed.

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries

Under the Act, DEPI has established a set of criteria and indicators based on those accepted internationally for sustainable forest management. While these apply to the whole forest estate, including parks and reserves, they are also relevant to both state forest and timber resource management.

However, DEPI has not set any progress measures, targets or time lines for how it expects timber resource management activities to contribute to achieving these criteria and indicators. It has advised that its new, integrated approach to public land planning and revised forest management planning will include measures and targets in addition to objectives. It already has some of these in other regional plans—for example its water, biodiversity and cultural heritage plans—but will need to develop others.

Timber resource management should be open to public scrutiny. Public reporting on progress in implementing objectives is central to this. Progress reporting against achievement of the Code's goals for environmental and cultural management occurs via DEPI's audit program and the 10-yearly scientific review of the Code.

Measuring and reporting on the Timber Industry Action Plan

The TIAP was released in 2011 to help the industry address identified challenges to achieving native forest timber harvesting objectives. Its focus is on the economic, commercial and social aspects. The TIAP does not have any targets or progress measures describing anticipated impacts for the industry. DEPI advised that the TIAP's aim is to facilitate industry development, not to prescribe a specific direction for industry. The TIAP provides six-monthly reports to government, but there is no consolidated public reporting on progress in implementing the TIAP or on its achievements.

Sustainable state forest management

DEPI has not established progress measures, targets or time lines for how it expects state forest management activities to contribute to achieving the criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management. Its intended changes to forest management planning should address this gap.

The criteria span a range of forest environmental, social and economic values and require data from a range of sources. Some of this data comes from DEPI's own forest and related monitoring and research, covering elements such as forest health, biodiversity and water quality. The remainder, particularly social and economic data, comes from other government bodies and agencies—for example, data on tourism opportunities, Indigenous cultural values and the value of products from the forest, such as minerals, timber and honey.

Under the Act, DEPI must report against the criteria and indicators for sustainable forest management at least every five years. It does this through its State of the Forests reports.

Until recently, the data that DEPI collected to measure and report against these criteria and indicators was poor. The 2003 and 2008 State of the Forests reports were undermined by data gaps and the lack of trend information for many indicators. The 2008 report identified that none of the criteria carried enough reliable data from which to draw conclusions.

At that time some monitoring was occurring in state forests but little in forests on other public land such as parks and reserves. The department complemented this monitoring with data from its other monitoring and research programs—for example, on water quality and weed management—and from other agencies, but there were many gaps in what was measured and the time periods covered.

As a result, the reports could not show whether forest health was being maintained, enhanced or deteriorating.

In response, in 2010 DEPI introduced a new monitoring program to comprehensively measure characteristics across all forested land in Victoria. The program has been designed well and represents a significant investment.

While this will improve the reporting in its 2013 State of the Forests report, it will be several years before meaningful trend data for some data sets can be reported. For this report DEPI has also collected substantially more data from other agencies than it had previously, which should enable trends to be reported against many indicators. DEPI advised it is on track to publish the report by December 2013.

In addition to the State of the Forests reporting, agencies should report against their individual areas of responsibility. While DEPI reports on some management areas related to forests, such as weeds and pests and water quality, it does not report on its key state forest management responsibilities:

- It has not assessed or reported on how well the sustainability charter, action statements and forest management plans are being implemented, or what each is achieving.

- It does not assess and report on how it directly commits and contributes to achieving the sustainability charter objectives.

- It lacks regular review processes to ensure that significant risks to achieving its forest management objectives are being identified and addressed.

The integrated public land planning DEPI has commenced provides an opportunity to address these weaknesses in its state forest and timber resource performance management. This also provides an opportunity for DEPI to clarify and transparently articulate the links between the number of different forest planning documents and reporting requirements, and how these interact and contribute to its actions and outcomes.

2.5 Oversight and accountability

Appropriate oversight and clear accountability is needed to direct and monitor the actions and progress of the agencies.

Oversight of the sector is comprehensive and generally well delivered, principally through the following groups:

- VicForests' board—the board is making VicForests more accountable for its actions and has improved risk management, identified new business opportunities and is addressing obstacles to further development.

- DEPI's and the Department of Treasury and Finance's additional oversight of VicForests—this includes reviewing its corporate plan and financial performance, providing feedback to VicForests, and reviewing annual reports and board appointments.

- A government committee monitoring TIAP progress—the committee receives six-monthly reporting across all actions. There has been no record of its deliberations or directions for addressing areas of risk, such as those relating to indemnity and planning laws. DEPI has advised that the committee will now provide it with formal feedback and it will be asked to endorse the prioritisation of actions at risk.

- The Native Forestry Taskforce—comprised of representatives from DEPI, VicForests, the Department of Treasury and Finance and the Victorian Association of Forest Industries. It is monitoring the implementation of a selection of TIAP actions that it has identified as being high priority. However, its terms of reference do not clearly specify its oversight role as articulated by the sector agencies, and should be clarified.

Effective oversight of whether the TIAP is achieving reasonable progress and outcomes has been difficult because the plan does not identify time lines, priorities and anticipated outcomes. This makes it hard for government, the industry and the community to understand how well the plan is actually progressing, and whether the changes it is achieving in the sector are aligned with what the government wants to achieve. Individual agencies have their own plans for delivering their actions and are making progress in their own sectors.

DEPI has also recently introduced a project coordination board to oversee and integrate its forest management and related projects.

The Minister for Agriculture and Food Security and the Minister for Environment and Climate Change are jointly responsible for the success of the sustainability charter. However, there is no central oversight of whether the charter's objectives for state forests are being achieved. Nor is there any formal mechanism to oversee or report on it. This lack of oversight and reporting creates a gap for how timber resource management is monitored or managed as a component of sustainable state forest management, and how the effects of timber harvesting are taken into account in this management.

The State of the Forests reporting is not specific to state forests or harvesting impacts. Therefore it is not clear how this report is used to help oversee and adapt the native forest timber industry.

Accountability should improve further when DEPI finishes its current work under the TIAP to clarify the respective roles and responsibilities of the agencies involved in the native timber industry.

Recommendation

- That the Department of Environment and Primary Industries strengthen its sustainable state forest and timber resource performance management by:

- setting a clear goal for state forest management

- establishing regional objectives, progress measures and targets for state forests that take into account both forest and timber resource management

- reporting publicly on progress in achieving these.

3 Is timber being harvested at a sustainable rate?

At a glance

Background

For harvesting to be sustainable it needs to occur at a rate that does not exceed the rate at which the forest grows back, and in a way that allows the pre-existing forest conditions to re-establish.

Conclusion

The Department of Environment and Primary Industries' (DEPI) determination of where timber harvesting can sustainably occur has not been as thorough or responsive as needed to adapt to changes over time. VicForests continues to improve—and needs to strengthen further—its largely effective approach for estimating the sustainable harvest level, to increase confidence in the sustainability of its harvesting approach.

Findings

- DEPI has not adequately documented the assessments on which its decisions to amend the forest management zoning scheme are based.

- VicForests' approach to estimating the sustainable harvest level is accurate and reliable but it can further improve aspects—e.g. thinning and profitability estimates.

- VicForests is meeting DEPI's regeneration standards but it is not accurately reconciling its regenerated areas against its harvested areas.

- After 10 years, DEPI has still not successfully regenerated some areas it is responsible for, and its current plan only addresses around 2 per cent of the backlog.

Recommendations

- That DEPI:

- review the forest management zoning and monitor its amendments process

- use a range of expertise to oversee its audits of VicForests' sustainable harvest level planning

- better manage its responsibilities for the regeneration of harvested forest.

- That VicForests address weaknesses in the way it schedules the sustainable harvest level, and better reconcile its regeneration with its harvesting.

3.1 Introduction

With good planning and management of timber harvesting, it should be possible to harvest at a rate that does not exceed the rate at which the forest grows back, and in a way that allows the pre-existing forest conditions to re-establish, as required by the legislation and regulations.

This audit examined the Department of Environment and Primary Industries' (DEPI) processes for determining where harvesting can occur and the accuracy and reliability of VicForests' sustainable harvest level estimate. It also assessed the appropriateness of the planning and monitoring of harvesting operations and the adequacy of forest regeneration.

3.2 Conclusion

Timber is being harvested within the current estimated sustainable harvesting rate and within the allowed areas. However, some of the processes for determining the area allowed and the sustainable rate can be improved to provide better assurance that harvesting will not adversely affect the long-term sustainability of the forest and timber resource.

DEPI has an established approach to determining which areas of state forest can sustainably support timber harvesting, which it has recently improved. However, in following this approach, DEPI has not been as thorough or responsive as needed to accommodate changes over time to forest values and forest management practices.

VicForests is harvesting less than its allocated area and continues to improve its largely effective approach for estimating the sustainable harvest level. While its approach is accurate and reliable, there are some aspects that, when addressed, will further improve the environmental, economic and social sustainability of the estimate.

VicForests is regenerating harvested areas adequately but is not accurately reconciling its successfully regenerated areas against the area harvested. DEPI has failed to successfully regenerate some areas it harvested before 2004 and its forward plan to deal with this is inadequate.

3.3 Identifying where harvesting can occur

Through national agreements and state legislation and planning, the Victorian Government has committed to meeting requirements for conserving native forests and protecting the natural and other values that forests provide, while at the same time allowing timber harvesting.

To meet these requirements, DEPI needs to determine which areas, or zones, of state forest should be protected for conservation purposes, and which should be available for harvesting.

DEPI has established a forest zoning management scheme to do this, but it has not adequately documented the assessments supporting its decisions. As a result it is not clear whether the zoning continues to appropriately meet conservation and timber harvesting needs. DEPI now has a process underway to review this for eastern Victoria, as required by the Timber Industry Action Plan.

3.3.1 Establishing harvesting zones

There is limited transparency of the assessments DEPI has undertaken in making decisions to amend the forest management zoning scheme, and it has not adequately reviewed the scheme over time. This means there is uncertainty about the extent to which the current harvesting areas are consistent with DEPI's harvesting and conservation objectives.

The forest management zoning scheme is the primary management and planning tool for activities conducted in state forests and should change over time in response to new information and conditions. It divides the forests into three categories, which:

- protect identified values and preclude harvesting—such as areas of forest with valued vegetation types, animal habitat or sites with cultural importance

- allow productive and other uses—with a focus on timber harvesting

- allow harvesting only under certain conditions.

Zoning changes can occur through minor zoning amendments or through a full review of the forest management plan or zoning scheme.

DEPI's process for making amendments includes criteria for assessing and approving amendment decisions. DEPI is following the process approval steps but its amendment documents do not consistently show what considerations were made or how the assessment criteria were met. This reduces the assurance about the quality of the amendment process, and whether the amendments have been fully consistent with conservation and harvesting objectives. In addition, DEPI has not:

- periodically assessed the appropriateness of the criteria, nor the cumulative impact of the amendments

- compiled information on the number of amendments.

The original zones were established between the mid-1990s and the early 2000s. Since then, the conservation reserves have expanded by as much as 150 000 hectares (ha) in eastern Victoria—reducing the total area of state forest. DEPI estimates there have been hundreds of small changes to the zones due to other factors, including new information on sites of particular value, improved connections between forests or new tracks.

DEPI's and VicForests' analyses indicate that these successive zoning changes have reduced the area and productivity of the forests available for harvesting across eastern Victoria. The regional forest agreements allowed for increases to conservation reserves, but required no net loss of the forest's timber production capacity in terms of volume, species and quality. However, the agreements do not define how this capacity will be measured, and the areas that are considered productive vary over time—for example, depending on the market demand for different species and qualities of wood.

Forest management plans, and therefore the forest zoning they establish, were to be reviewed after 10 years but this did not happen for the East Gippsland, Central Highlands and North East plans. Plan implementation was to be monitored and reported on annually, but this did not occur.

The only zoning scheme reviewed was for the East Gippsland forest management area in 2011. The process used is summarised in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A

Summary of the process used for the East Gippsland zoning review

|

The first step in the review was zoning the protection areas needed to meet the existing mandatory conservation requirements. As far as possible, DEPI identified forest areas where multiple values could be protected in the one area, e.g. an important cultural site requiring special protection zoning could also contain a specific vegetation type requiring conservation and could contain the habitat of a threatened species. The second step created zones where harvesting was allowed, to meet timber production commitments. The third step was to use zoning to meet other requirements, such as non-mandatory conservation requirements and stakeholder needs. This process included consultation with a range of stakeholders. However, there were few 'unzoned' areas left to meet non‑mandatory conservation requirements. DEPI's analysis of the review outcomes identified that, while the changes benefited conservation objectives and the area available for timber harvesting increased slightly, there was a net loss of timber productive capacity. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The review was guided by the criteria and zoning constraints identified in regional forest agreements, forest management plans and the forest management procedures. However, it:

- did not link to a review of the forest management plan itself, even though the plan was 14 years old and the range of changes considered for the zoning suggest that the guidelines and actions in the plan did not still represent the best management approach

- did not lead to any amendment of the forest management plan either, to incorporate the changes resulting from the zoning

- included considerable new information and changes to zones, suggesting that the review should have occurred sooner than 14 years after the plan was first established.

The poor transparency of DEPI's zoning amendment assessments and its inadequate review of forest management plans and zoning over the past 15 years mean that the management of state forests has not been as adaptive or responsive as it needs to be, or was intended. The Timber Industry Action Plan called for all zoning in eastern Victoria to be reviewed, which DEPI has committed to doing by March 2015, starting with the Central Highlands zoning.

3.3.2 Allocating timber to VicForests

Under the Sustainable Forests (Timber) Act 2004 (the Act), DEPI gives VicForests legal access to sell wood from the areas of state forest it has identified as available for harvesting, through an allocation order. The order identifies the total state forest area available for harvesting in eastern Victoria, based on the zones allowing harvesting. The allocation order provides a simple and transparent way of allocating the total area for harvesting, as an initial step in ensuring sustainability.

DEPI also considers regrowth times in determining gross area harvest limits for ash eucalypt and mixed species eucalypt forests—83 years for ash and 113 years for mixed species. This supports sustainability by constraining harvesting to match the replacement rate.

The Allocation to VicForests Order 2004 gave VicForests access to a proportion of the total available area from 2004 to 2019 and set a harvest limit for each of the three, five‑year terms over this period. Following the October 2013 amendment to the Act, DEPI introduced the Allocation Order 2013, which now allocates the timber to VicForests indefinitely, rather than restricting it to 15 years. The new order still includes a similar five-year harvest area limit, based on the same regrowth considerations used in the previous order. This brings Victoria into line with other states, which do not constrain timber resource use to such limited time frames.

3.4 Identifying the sustainable harvest level

The three main steps that VicForests takes in planning the amount of timber it can sustainably harvest and sell—the sustainable harvest level—are:

- identifying what is available and suitable for harvesting

- scheduling where and when it will harvest

- forecasting the volume of timber it will make available for sale.

Since 2010, VicForests has been responsible for doing this in a way that addresses the potentially conflicting criteria for sustainable timber resource management that the Act, VicForests' Order in Council, the Sustainability Charter for Victoria's State forests, the Code of Practice for Timber Production and the Timber Industry Action Plan identify. These include:

- achieving the best economic return for VicForests and the state

- maintaining or enhancing environmental values

- ensuring that forests are left in as good or better condition than they were in before harvesting

- maintaining, as far as possible, a viable industry and dependent communities

- adapting to the risks inherent in changing markets, industry scale and technology, and catastrophic fires.

This puts significant responsibility on VicForests to achieve the right balance across these criteria as this is a critical step in making sure timber harvesting is sustainable.

VicForests has developed an accurate and reliable approach to estimating the sustainable harvest rate, demonstrating its capability to manage the risks and the environmental, economic and social sustainability issues involved—in both the short and long term. Some weaknesses in addressing the range of criteria for sustainable timber resource management remain, particularly with VicForests' scheduling method. These will need to be addressed to further improve the estimate.

3.4.1 Sustainable harvest area and yield

VicForests' estimates of the forest area and volume—or yield—of sawlogs it could sustainably and commercially harvest are based on sound rationale and accurate and reliable methods and data, although the quality of the estimate will be improved by further changes that VicForests is planning.

The amount of the allocated forest that is available and suitable for harvesting is much smaller than the total area available identified in the allocation order because some areas:

- are protected by timber harvesting regulations

- are unsuitable for commercial harvesting—for example because they have trees that are not commercially desirable species, are too distant from markets or steepness makes harvesting too costly.

State forest is 44 per cent of all public forests. In 2013, 58 per cent of state forest—1.82 million ha—was available for timber harvesting and VicForests identified that around a half of this—815 000 ha—was suitable or potentially suitable for commercial harvest. From this area, only 3 300 ha was harvested in 2013, which is less than 0.2 per cent of state forest, and 0.05 per cent of the public forest area.

VicForests' calculation of the area and yield requires reliable and current information on the volume of timber present in forest areas—called the inventory—as well as maps of forested areas and growth information obtained by monitoring a sample of trees over time. VicForests assumed responsibility for this expensive, ongoing process from the former Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) in 2010. The current inventory is accurate and reliable, and VicForests has developed a sound strategy for collecting and improving the data and information, and for checking that it is reliable, representative and regularly updated. This will provide it with better information and improve its planning for sustainable harvesting.

VicForests' calculation of the area and yield uses time frames appropriate to the regrowth rates of harvested forest types and assesses risks to forest distribution, condition and regeneration, such as fire. It also reconciles previous estimates of sustainable yield against actual harvest and regrowth data and has plans in place to better predict the yield for each of the timber grades it sells.

3.4.2 Scheduling the harvest

VicForests needs to schedule its harvest over time to even out variations in the cost of harvesting—flatter forest or areas closer to the mills will be cheaper to harvest—and likely revenue—some areas will produce more or better quality wood than others. This provides it with even revenue, and the mills and harvest and haulage contractors with steady supply. It does this over a 20-year period.

VicForests has improved the scheduling since assuming the responsibility from DSE, based on a sound prioritisation of the improvements needed. As a result, it has developed an adequate scheduling approach but can further improve this to meet the criteria for timber resource management.

It selects areas for harvesting, known as coupes, that it considers will be profitable, i.e. where it expects revenue to exceed costs. VicForests includes overheads along with operational costs in this calculation. However, the true profitability of an individual coupe can only be assessed by comparing the expected revenue with the likely operational costs that will come from harvesting that one coupe, excluding fixed costs such as overheads.

Including fixed costs such as overheads removes some coupes from the schedule too early in the planning process and, as a consequence VicForests is underestimating how much it can profitably harvest. It will need to remove fixed costs from its scheduling in future to maximise profitability, and has advised that it will address this.

There are additional weaknesses in the process, which VicForests will need to address to optimise the environmental, social, commercial and economic sustainability of its planned harvest schedule:

- It is not modelling the impact of thinning—selectively removing trees to improve the growth of those remaining—on current harvest volumes and future growth rates, even though this provides an important potential source of wood and should improve the growth rates of the remaining trees.

- It needs to pursue better data on the quality and proportion of sawlogs that will become available after 2030.

VicForests is also not using the information it has to assess whether the forest condition, biodiversity and health would be in as good or better condition at the end of the 20-year period as it was before, if it follows its preferred harvest schedule. VicForests should include this step in its process, as part of optimising the sustainability of its schedule.

3.4.3 Forecasting the volume of timber available for sale

VicForests' 20-year forecasts of how much timber it will make available for sale are based on the sustainable harvest levels identified through the area, yield and scheduling processes, as well as the volume of timber it is currently contracted to provide.

Its 2013 forecast, for 2013 to 2033, is more accurate than its previous forecasts because VicForests has improved its method and data since its first estimate in 2010. For the first time the effects of the 2009 fires have been included, following thorough analysis. VicForests has identified that the forecast is likely to change again in 2016, following updates to its forest growth data and capability to map the areas suitable for harvesting.

The 2013 forecast predicts a continuation in the overall decline in availability since 2002. The reasons for this decline include increases in conservation reserves and fire impacts, as well as VicForests' improved understanding of which forest areas can be harvested and sold profitably and sustainably. This is shown in Figure 3B.

Figure 3B

History of 20-year sawlog availability forecasts for eastern Victoria

|

Available high quality sawlog volume (m3) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Year |

Forecast source |

Central Highlands |

East Gippsland |

Total |

|

2002 |

Our Forests Our Future |

302 500 |

214 900 |

517 400 |

|

2008 |

Joint Sustainable Harvest Level Statement (DSE and VicForests) |

324 000 |

173 000 |

497 000 |

|

2011 |

VicForests(a) |

332 000/312 000 |

100 000/80 000 |

405 000 |

|

2012 |

VicForests(a) |

393 000 |

102 000/82 000 |

443 000 |

|

2013 |

VicForests(a) |

330 000/264 000 |

73 000 |

350 000 |

(a) The volume available is predicted to be higher at the start of the 20-year period but reduce to a lower level during the period. The total sums up the volumes based on the number of years it is predicted to be at each level.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by VicForests.

DEPI plans to audit VicForests' approach to estimating the sustainable harvest level every five years from 2018. DEPI would benefit from using an appropriately broad range of expertise across the environmental, social, commercial and economic aspects inherent in estimating sustainable harvest levels.

3.5 Harvesting at the sustainable level

VicForests is harvesting at the sustainable level for ash forests and within the sustainable level for mixed species forests. The range of external audits it undergoes through DEPI's audit program and its independent certification to the Australian Forestry Standard, consistently find it is planning well and harvesting within the allocated area. It is further improving some of its activities, such as controls to make sure all coupe planning steps are followed.

3.5.1 Planning for harvesting

VicForests' harvest planning process produces two types of plans:

- timber release plans—that identify which coupes it may harvest over a five-year period

- coupe plans—that detail how it will conduct the harvest for an individual coupe.

VicForests develops robust and comprehensive timber release plans and individual coupe plans, as evidenced through independent audits and certification. The coupe plans comply with requirements, and VicForests is improving its planning for these to address recommendations for further improvement.

Selecting harvesting methods

VicForests has effective processes for selecting the harvesting method most appropriate to the characteristics of the forest type present in a coupe.

Its processes use a hierarchy of decision steps for each coupe, according to factors such as the types of vegetation present, risks to successfully regenerating the coupe and seed availability. The approach is designed to guide objective and consistent decision-making between coupes. There are four harvesting options:

- Clear-fell harvesting—fells all trees in a coupe except in areas that it is required to protect for biodiversity, water protection and other requirements, such as older trees with important habitat value. This is the main method used in ash forests.

- Seed tree harvesting—retains a proportion of mature trees on a site so that these can re-seed the site after harvesting. This is used predominantly for mixed species forests.

- Selective or uneven-aged harvesting—takes only mature trees, and leaves immature trees for harvesting at a future date.

- Thinning—removes some trees, either to increase the growth rate and health of the remaining trees or to access timber from trees before they die.

Clear-fell harvesting

Selective harvesting was trialled successfully in East Gippsland coastal forests, to maintain the uneven-aged and species-rich characteristics of these forests, in 2004–05 and again from 2010, but this did not lead to VicForests using it more widely. VicForests is now further assessing the value in using this method more widely, including the environmental, economic and social implications of this approach.

VicForests has used thinning less frequently in recent years, primarily because the coupes it has been harvesting have not been as suited to thinning, but also due to fire impacts. It also had little incentive to use thinning to improve forest productivity under the 15-year allocation order, as it had no certainty about when it could harvest any thinned areas and therefore realise the financial benefits of doing this. This disincentive has been removed with the introduction of an indefinite allocation order period.

3.5.2 Harvesting within the allocated area

The area and volume that VicForests harvests have declined since VicForests was established, and even prior to this. The reasons for this include increases in conservation reserves and bushfires and better estimation processes.

Between 2002 and 2009, DSE monitored and reported on harvesting levels. An Expert Independent Advisory Panel reviewed this process and reported to the Minister for the Environment on it, including recommendations for improving DSE's process.

The panel confirmed that for the first five-year period of the allocation order (August 2004 to July 2009) the cumulative area harvested was well within the total allocated limit. However, VicForests harvested 3 per cent—86 ha—more than the permissible amount for that five-year period across two forest types in 2009. VicForests received penalties from DSE for this.

VicForests has since improved its controls over where harvesting occurs, and monitors the harvest level quarterly. The 2012 amendments to the allocation order permitted VicForests to harvest up to an additional 2 per cent of the available area for 2009 to 2014 and the subsequent period, as long as any increase was offset by reductions in the final period.

VicForests' monitoring and DEPI's audits show the cumulative area VicForests harvested in the first two years of the second five-year period—August 2009 to July 2014—is within the allocated area.

DEPI's audits since 2010 have identified that harvested areas comply with the area limits identified in the timber release plans, including special management zone and water catchment limits. Its most recent audit, covering 1 July 2009 to 30 June 2011, shows that VicForests' activities did not result in any noncompliances, or require any recommendations.

3.6 Regenerating harvested areas