Occupational Health and Safety Risk in Public Hospitals

Overview

Occupational health and safety (OHS), which covers staff health, safety and welfare in the workplace, is particularly important in public hospitals because of the major hazards that exist in these environments. Such hazards can lead to musculoskeletal injuries, acute traumatic injury, infections such as hepatitis and potentially even death. The impact of poor OHS is felt not only by the affected staff, but also by the patients they are treating.

The audit found that while there are examples of better practice among the audited public hospitals, there are also significant shortcomings which put staff at unnecessary risk. Among the key findings are that insufficient priority is being given to OHS in public hospitals by senior management and the Department of Health (the department). Managers within public hospitals need to be held more accountable for the OHS performance of areas under their control.

Neither the department, as the health system manager, nor WorkSafe, as the OHS regulator, has a comprehensive understanding of sector‑wide OHS risks or emerging trends in public hospitals. Collaboration between the department and WorkSafe until recently has been poor with missed opportunities to collectively reduce sector-wide OHS risk. Wide variability between public hospital OHS management practices—such as quality assurance of safety management systems and safety inspections—highlight the need for stronger sector-wide leadership.

Occupational Health and Safety Risk in Public Hospitals: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2013

PP No 283, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Occupational Health and Safety Risk in Public Hospitals.

This audit assessed the effectiveness of managing occupational health and safety risk in public hospitals.

The main finding is that public hospital staff face unnecessary risks while at work. More needs to be done by the boards of public hospitals in their role as employers, WorkSafe in its role as regulator, and the Department of Health in its role as health system manager, to reduce the unacceptably high risks to staff.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

28 November 2013

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle

Auditor-General |

Audit team Michele Lonsdale—Acting Sector Director Michael Herbert—Team Leader Aina Anisimova—Analyst Dallas Mischkulnig—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

The hospital working environment is complex and demanding and can pose significant risks to staff safety. The impact of poor occupational health and safety (OHS) is felt not only by affected staff but also by the patients they are treating. Therefore it was important for my office to examine whether public hospitals in Victoria are effectively managing OHS risk.

Public Hospital staff are being put at unnecessary risk. I found significant shortcomings in the daily management of OHS in public hospitals visited during this audit. Key issues include inadequate incident reporting systems, inconsistent follow up and investigation of OHS incidents, and superficial analysis of root causes. A more systematic approach which integrates all aspects of safety management is needed.

Sustained improvement in the safety culture is not likely to occur without a renewed focus from senior hospital management and clear accountability by managers for OHS performance of areas under their control.

WorkSafe, as the OHS regulator, and the Department of Health, as the health system manager, can assist public hospitals to reduce sector-wide OHS risk. Yet I found that neither had a good understanding of sector-wide OHS risk.

Collaboration between WorkSafe and the department has been poor until recently, despite the cost and injury claims to public hospital staff being substantial for over a decade. WorkSafe cannot demonstrate that its project activity effectively decreases OHS risk in public hospitals. The department has not been in a position to respond to service-wide OHS risk. Variable OHS management practices between public hospitals I audited further highlight the need for stronger sector-wide leadership.

I am pleased to note that during this audit WorkSafe and the department have acknowledged the need for greater collaboration. I intend to revisit this issue to assess whether the level of protection for public hospital workers has improved.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

November 2013

Audit Summary

Occupational health and safety (OHS) covers staff health, safety and welfare in the workplace. OHS is particularly important in public hospitals because major hazards exist—such as exposure to infectious and chemical agents, manual handling of patients and materials, slips, trips, falls, and occupational violence. These hazards can lead to musculoskeletal injuries, acute traumatic injury, infections such as hepatitis and potentially even death. The impact of poor OHS is felt not just by affected staff, but also by the patients they are treating.

Hospitals are the single largest sub-sector in the public sector workforce. At 30 June 2013, there were 84 public hospitals in Victoria with 98 446 employees. From 2007–08 to 2011–12, public hospital workers made 10 621 WorkCover claims. Only manufacturing and construction industry workers made more claims over this period. The WorkCover premium paid by Victorian public hospitals is substantial, with over $80 million paid in 2012–13 alone.

There have been few external reviews or audits of OHS in hospitals. However, the 2011 Parliamentary Inquiry into Violence and Security Arrangements in Victorian Hospitals, and in particular, Emergency Departments, recognised that hospital management faces complex challenges because of the working environment. The majority of public hospital staff surveyed during this audit expressed concern about being injured at work.

This audit assessed the effectiveness of managing OHS risk in public hospitals. In particular, it examined whether:

- public hospitals, as employers, demonstrate comprehensive OHS management of public hospital worksites

- the Department of Health (the department), as manager of the Victorian public health system, effectively carries out its role of responding to OHS-related risks to health service delivery, or major risks to public hospital staff and the community

- WorkSafe appropriately targets efforts to decrease OHS risk in public hospitals.

The audit focused on public hospitals as workplaces—health services often manage more than one public hospital. In this report, the term 'public hospitals' refers to both health services and public hospitals, and reference to boards includes both health service and public hospital boards. Recommendations are made to both health services and public hospitals to avoid confusion.

Conclusions

Public hospitals present hazardous challenges that demand OHS management of the highest standard. The audit found that while there are instances of better practice among the audited public hospitals, there are also significant shortcomings which put staff at unnecessary risk. In addition, weaknesses identified with the role of the department as the health system manager, and with WorkSafe as the OHS regulator, have contributed to the failure to achieve better management of OHS risk by public hospitals.

There is insufficient priority given to, and accountability for, OHS in public hospitals. Staff safety needs to be given a higher priority by senior management and the department, and managers within public hospitals should be held to account for the OHS performance of areas under their control. Sustained improvement in the public hospital safety culture is not likely to occur without greater priority and clear accountability.

Neither the department nor WorkSafe has a comprehensive understanding of sector‑wide OHS risks or emerging trends in public hospitals. WorkSafe cannot demonstrate that its project activity reduces OHS risk in public hospitals. Collaboration between the department and WorkSafe has been poor, with missed opportunities to reduce sector-wide OHS risk. Wide variability between public hospital OHS management practices—such as quality assurance of safety management systems and safety inspections—highlight the need for stronger sector-wide leadership.

These issues collectively warrant a future review of public hospital OHS risk to assess whether the level of protection for public hospital workers has improved.

Insufficient priority and accountability for occupational health and safety in public hospitals

Several indicators collectively suggest that OHS is not given sufficient priority in public hospitals. Indicators include:

- a culture of accepting OHS risk

- resources not always available for hospital staff to consistently comply with OHS policy and procedures, and work safely

- inadequate OHS information provided to staff

- insufficient training provided to staff and managers

- the department, as manager of the Victorian health system, not requiring assurance from public hospital management that staff are adequately protected from OHS risk.

Although policy at each of the four audited public hospitals states that the board of the public hospital, as employer, is ultimately accountable for OHS, there is a breakdown in the chain of accountability below the board:

- Unit managers who are responsible for the day-to-day management of work units are not held accountable for OHS performance—this is also the case for the executive directors of public hospital departments. While there is a policy commitment that managers are responsible for maintaining a safe working environment, there are no mechanisms or targets to hold these managers to account for OHS performance.

- Ownership of OHS risk does not reside with the manager where the risk occurs. At an organisational level, risk registers identify the corporate services area as the owner of OHS risks, despite OHS risks presenting predominantly in clinical departments.

Hospital management is not fully informed of occupational health and safety risks

A combination of lead and lag (proactive and reactive) indicators is necessary to capture OHS performance and identify gaps in the safety culture of an organisation. Significant gaps exist not only in the OHS information that is made available to management but also in how this information is integrated to inform decision-making.

Information on OHS incidents and risks is incomplete:

- The OHS incident reporting system used by public hospitals is not fit-for-purpose—leading to inconsistent reporting that is of questionable value to management. There is also evidence of under-reporting of incidents and 'near misses'.

- Safety inspections by hospital staff varied widely in frequency, and in the number and type of hazard identified, despite public hospital worksites sharing common OHS risks.

- Assessment of OHS information in public hospitals was lacking, particularly analysis of the factors causing OHS incidents and evaluation of the effectiveness of controls.

Different sources of information on OHS risk are not routinely integrated or prioritised. This makes it difficult to have an overall understanding of a public hospital OHS risk profile or to clearly prioritise effort.

Understanding sector-wide occupational health and safety risks and emerging trends

No single agency has a comprehensive understanding of sector-wide OHS risk because no agency currently monitors OHS incidents and emerging trends. The department does not routinely monitor or review OHS performance of public hospitals apart from one risk, which it requires public hospitals to report—occupational violence against nurses. It does not analyse this data or provide feedback to public hospitals.

While WorkSafe is fulfilling its monitoring role under the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004, it is only required to be notified of serious OHS incidents and OHS injury claims. There are limits to its ability to monitor all incident data across over 246 000 Victorian worksites.

Monitoring this data is important as upward trends in incidents and near misses can indicate that controls are failing and more serious injuries are likely to occur. Monitoring across the sector also allows interventions to be developed efficiently to control or eliminate systemic OHS risks.

WorkSafe projects

WorkSafe conducted 18 projects from 2007 to 2012, which focused on major OHS risks in public hospitals, such as manual handling and occupational violence. Despite significant investment, WorkSafe does not know which project is most effective or whether any of these activities are effective in reducing OHS risk in public hospitals.

WorkSafe's management of these projects was inadequate as:

- its approach to selecting hospital worksites for projects was not based on clear criteria and was not systematic

- project objectives were not clear

- project contingencies were not planned to ensure they were completed

- performance during the project was not measured regularly against stated indicators.

During this audit, WorkSafe acknowledged shortcomings with its current project management framework and is changing its approach. WorkSafe is developing a new model to target risk across all industries, with an ongoing program focus on the top OHS risks. WorkSafe will fully implement this new approach by June 2014.

WorkSafe has also indicated a willingness to confirm annually with the department the assessed compliance of public hospitals with OHS laws. When WorkSafe assesses that the public hospital industry OHS risk is reduced to the average system level then these reviews could become less frequent.

Recommendations

- That public hospitals and health services give higher priority to, and ensure accountability for, the management of occupational health and safety.

- That the Department of Health requires public hospitals and health services to annually assure it that they:

- manage occupational health and safety through a systematic approach in accordance with relevant legislation and standards

- provide workers with the highest level of protection against risks to their health and safety that is reasonably practicable in the circumstances.

- That WorkSafe provides support to the boards of public hospitals and health services on occupational health and safety leadership and requirements to raise awareness of their responsibilities to comply with occupational health and safety laws, so that public hospital staff receive the highest practicable level of occupational health and safety protection.

- That public hospitals and health services implement a systematic and integrated approach to occupational health and safety that complies with the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001, or an equivalent standard.

- That while public hospital industry occupational health and safety risk remains significant compared to other industries, WorkSafe annually confirms to the Department of Health that public hospitals and health services:

- comply with occupational health and safety legislation

- have in place a systematic approach to the control of occupational health and safety risks, and that effective risk control mechanisms exist.

- That WorkSafe identifies sector-wide occupational health and safety risks in public hospitals and provides this information to the Department of Health, public hospitals and health services.

- That the Department of Health and WorkSafe collaborate to assist public hospitals and health services to control the highest occupational health and safety risks.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Health, WorkSafe and four audited health services with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Occupational health and safety

Occupational health and safety (OHS) covers employee health, safety and welfare in the workplace. A fundamental principle in the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (the OHS Act) is that an employer such as the board of a public hospital, 'must so far as is reasonably practicable, provide and maintain a working environment that is safe and without risk to health'. An employee must also take reasonable care for his or her own health and safety, and for the health and safety of others.

Major hazards exist in hospitals—exposures to infectious and chemical agents; lifting and repetitive tasks; slips, trips, and falls; occupational violence; and risks associated with poor design of the workspace. These can lead to infections such as hepatitis, musculoskeletal injuries, stress and serious injury such as fractures from exposure to occupational violence, acute traumatic injury and even death.

1.2 Public hospitals

This audit focused on public hospitals as workplaces—larger health services often manage more than one public hospital.

Hospitals are the largest employer group in the public sector. At 30 June 2013, there were 84 hospitals in Victoria employing 98 446 people—including ongoing, fixed term and casual staff. Over the past five years, the WorkCover premium paid by public hospitals totalled $387 million, $80.5 million for 2012–13.

1.3 WorkSafe

WorkSafe Victoria operates under the mandate of the Accident Compensation Act 1985 and the OHS Act. It is the regulator of Victoria's workplace safety system, and has statutory obligations to assist in reducing OHS risks and injuries. Its role includes monitoring and enforcing compliance with the OHS Act, and promoting OHS education and training. These activities extend beyond the scope of the projects examined during this audit.

1.4 Devolved governance

Managing a public hospital is a complex and challenging undertaking, with involvement from various levels of government, and public and private sectors.

The devolved governance model for public hospitals is designed to allow decisions to be made that are most appropriate and effective at a local community level. It recognises that an approach to service delivery in one public hospital—with a unique combination of patients and service demand, culture and workforce—may not be the most effective solution in a different public hospital.

The Department of Health (the department) is the health system manager, and is responsible for monitoring the performance of public hospitals, on behalf of the Minister for Health.

1.4.1 Occupational health and safety management framework model

The Department of Human Services—Public Hospital Sector Occupational Health and Safety Management Framework Model, 2003 was developed in response to the 2001 Victorian Government's Occupational Health and Safety Improvement Strategy.

The framework is designed to assist public hospitals to develop a comprehensive approach to managing health and safety. It is based on commonly accepted health and safety management system standards, such as the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001 and SafetyMAP, an audit tool designed by WorkSafe to help workplaces improve their OHS management.

The framework is not meant to be in addition to existing systems a public hospital may already have in operation—rather it allows an assessment of current performance to ensure that all elements are satisfactorily addressed.

1.5 Australian occupational health and safety standards

The Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001, is relevant to all organisations and provides general guidance on how to implement, develop and improve a safety management system.

The emphasis in the OHS legislation and in this standard is for organisations to develop and implement control actions which, wherever possible, eliminate workplace hazards or isolate people from the hazard. Where this is not possible, work activities should be planned and controlled to prevent injury and illness. In order to achieve these objectives an organisation should implement the best practicable methods and technology.

1.6 Reviews and inquiries

1.6.1 Victorian Taskforce on Violence in Nursing

In its 2005 report the Victorian Taskforce on Violence in Nursing (the taskforce) identified and reviewed existing systems, procedures and policies in place in Victorian public hospitals and recommended strategies to reduce the incidence of violence.

The taskforce found that a significant barrier to addressing nurse violence is a lack of clarity around OHS incident definitions, as well as under-reporting. The taskforce concluded that a plan of action endorsed by senior management should improve risk management and OHS reporting. It found that a readily accessible, simple reporting procedure and appropriate follow-up by managers should encourage reporting.

1.6.2 Parliamentary inquiry into violence and security arrangements

The Parliamentary Inquiry into Violence and Security Arrangements in Victorian Hospitals and, in particular, Emergency Departments, 2011 found that hospital management faces a complex challenge in reducing occupational violence.As a result of the taskforce review and the Parliamentary inquiry, the department developed a policy—Preventing occupational violence: A policy framework including principles for managing weapons in Victorian Health Services, 2011.

1.7 Audit objectives and scope

This audit examined the effectiveness of the employer, and oversight and regulatory roles, in the management of OHS risk in public hospitals. The main focus was on the employer. Four health services were audited—two large metropolitan services at multiple hospital sites, a large regional service, and one rural hospital. The four services represent organisations of varied size and patient demographics with services offered in different regions. The selected health services include a mixture of high, medium and low ratios of WorkCover claims to full-time equivalent data.

In this report the term 'public hospitals' refers to both health services and public hospitals.

1.8 Audit method and cost

The audit team conducted extensive site visits at four health services covering 11 public hospital sites. It assessed each of the organisations against the core elements of an OHS safety management system, based on the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001. This standard covers policy, consultation, communication and reporting, hazard identification, assessment and control, and monitoring and evaluation.

Evidence gathered from each of the public hospital sites was reinforced by a range of other sources including:

- a safety climate survey of staff at the four sites, using a census approach and based on a validated tool which measured:

- management commitment—including priority of OHS and communication

- culture—such as the supportive environment and staff involvement in OHS

- personal priorities and personal appreciation of risk

- the work environment

- interviews with public hospital staff and managers of work units in a variety of settings within the four selected public hospitals—emergency departments, mental health, aged care and environmental services—focusing on elements of the OHS safety management system, as above

- a benchmarking survey of OHS directors across 11 of the 12 major metropolitan, and all five large regional public hospitals to collect baseline information on how key OHS elements are being managed—including OHS incident reporting and key performance indicators, workplace injuries, training, dedicated OHS resources and accountability

- a review of departmental governance documents, and WorkSafe documents relating to its risk prioritisation framework, claims, premium data and project management over the past five years.

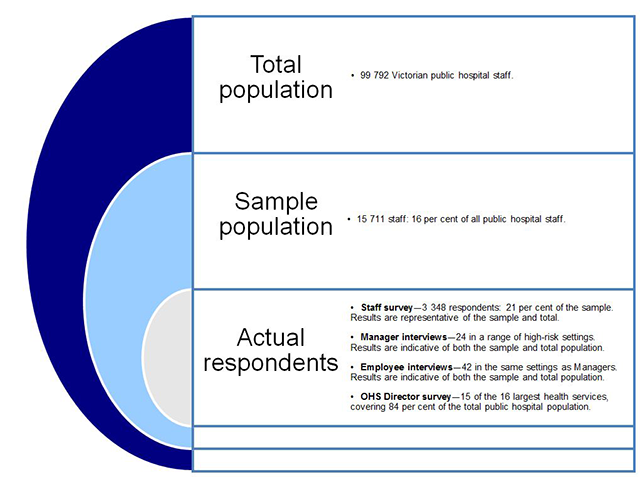

Figure 1A illustrates the scale of the surveys and interviews undertaken to support the site visits.

Figure 1A

Surveys and interviews undertaken during this audit

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $407 000.

1.9 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines two key organisational drivers—priority and accountability—and how they impact the management of OHS in public hospitals.

- Part 3 examines the adequacy of safety management systems in public hospitals.

- Part 4 examines the roles of WorkSafe and the Department of Health in monitoring sector-wide OHS risk.

2 Occupational health and safety priority and accountability

At a glance

Background

A strong safety culture constantly places a high priority on worker safety in a hazardous environment such as a hospital. Leadership commitment and clear accountability also underpin strong occupational health and safety (OHS) performance.

Conclusion

There is insufficient priority given to, and accountability for, OHS in public hospitals. Staff safety needs to be given a higher priority by senior management and the Department of Health (DH), and managers within public hospitals should be held to account for the OHS performance of areas under their control. Sustained improvement in the public hospital safety culture is not likely to occur without greater priority and clear accountability for, worker health and safety in public hospitals.

Findings

- There is a culture in public hospitals of accepting OHS risk.

- There is insufficient OHS information provided to public hospital staff.

- There is insufficient training provided to public hospital staff and managers.

- DH does not require assurance from public hospitals that staff safety is adequate.

- Managers are not held to account for OHS performance of their workplace.

- Neither OHS reporting nor target setting was found at the work unit or clinical department level in the audited public hospitals.

Recommendations

- That public hospitals and health services give higher priority to, and ensure accountability for, the management of OHS.

- That DH requires public hospitals and health services to annually assure it that they manage OHS systematically and in accordance with relevant legislation and standards and provide workers with the highest level of protection against risks to their health and safety that is reasonably practicable in the circumstances.

- That WorkSafe provides support to the boards of public hospitals and health services on OHS leadership.

2.1 Introduction

Making occupational health and safety (OHS) a high priority, and leadership commitment to this, have long been identified in studies as key factors in improving staff safety. The Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (the OHS Act) states that staff should be given the highest level of protection practicable against risks while at work.

In hospitals, it is the board, as the employer, that is ultimately accountable for providing a safe workplace. However, managers of areas where risks present also need to be held to account for OHS performance.

2.2 Conclusion

OHS needs to be given a higher priority by the Department of Health (the department) and public hospitals. Improving OHS performance is undermined by a breakdown in the chain of accountability in the boards of public hospitals. Managers at each level within these organisations need to be held to account for the OHS performance of areas under their control. Sustained improvement in OHS is unlikely without greater priority and clear accountability for, worker health and safety in public hospitals.

2.3 Insufficient priority for staff health and safety

The hospital workplace is hazardous and unpredictable. It requires a strong safety culture that demands the safety of both patients and staff be given the highest priority. Evidence gathered during the audit suggests that insufficient priority is currently being given to OHS in public hospitals. For example:

- there is a culture of accepting OHS risk

- resources are not always available for hospital staff to consistently comply with OHS policy and procedures to work safely

- OHS information provided to public hospital staff is not sufficient

- training provided to staff and managers across the health system is insufficient

- the department does not require assurance from public hospitals that staff safety is adequate.

2.3.1 A culture of accepting workplace risk

Making safety an organisation-wide priority is only achievable when it is part of a hospital's culture. Taken together, responses to several questions in the safety climate survey and interviews with staff and managers, point to an acceptance of preventable workplace risk.

All staff at the four public hospitals audited were invited to participate in the safety climate survey, which was based on a validated tool, and measured:

- management commitment—including priority of OHS and communication

- culture—such as the supportive environment and staff involvement in OHS

- personal priorities and appreciation of risk

- the work environment—such as access to equipment and other resources.

Over 3 300 staff from all major occupations in public hospitals responded, including nurses, doctors, patient service attendants (orderlies), allied health professionals and environmental service staff. The results are statistically representative of both the public hospitals audited and the total public hospital workforce in Victoria.

In addition, interviews were conducted with public hospital staff and managers of work units in emergency departments, mental health, aged care and environmental services within the four selected public hospitals. Questions focused on core elements of worker safety, such as OHS policy, staff consultation, communication, OHS incident reporting and hazard identification, assessment and control.

The majority—68 per cent—of public hospital staff who were surveyed stated that they are concerned about being injured in their current job. Nearly a third—29 per cent—of staff surveyed stated that their safety is not the most important aspect of their jobs. This is concerning given that an employee has a duty, under the OHS Act, to take care of his or her own health and safety while at work.

Strong safety cultures—typically found in industries such as the airline and nuclear power industries—strive to capture all incidents and 'near misses', regardless of the consequences of such incidents. This is because these events are ideal opportunities to learn how to improve in the local setting and to avoid major incidents. However, just over half—22 of 42—of staff interviewed during the audit stated that they had not reported an OHS incident. The main reason given was that it takes too much time to report an incident in the current system. As a result, near misses and incidents considered insignificant—such as a minor assault—are more likely not to be reported compared with other more serious incidents.

Forty-four per cent of staff survey respondents believe that the health and safety representative role is not effective at all or is only partially effective. This is concerning as the role of the health and safety representative, as defined in the OHS Act, is to represent the views of the work group. It was not possible to confirm this finding from other data sources during this audit.

2.3.2 Resource constraints can lead to unsafe work practice

Surveyed staff reported that working conditions and having enough resources were the most critical factors in determining the adequacy of their workplace safety. However, responses to questions about resource constraints were the lowest scoring of all responses in the survey. Of note, 42 per cent of respondents report they cannot routinely get the equipment or resources needed to work safely.

While staff survey respondents overwhelmingly—90 per cent—stated it was unsafe not to follow OHS procedures, 17 per cent of these staff reported that it was sometimes necessary to ignore OHS procedures due to time pressure—20 per cent believe that OHS procedures are not always practical. These responses indicate that at times staff may feel pressure to do what they know is not safe.

It was not possible to confirm whether resource constraints were in fact causing unsafe working conditions in the audited public hospitals as there are no evaluations of trends or factors causing OHS incidents. Part three of this report examines evaluations and analysis of staff safety in more detail.

2.3.3 Occupational health and safety information provided to public hospital staff is not sufficient

Staff survey respondents who rated communication of OHS issues highly also had a positive rating for overall safety. However, several issues were identified by staff, including that OHS information is either not provided at all in some public hospitals or is provided irregularly. For example, over a third of respondents stated that their manager either does not pass on—or only passes on some—OHS information. Fourteen per cent of staff surveyed stated they do not participate in OHS discussions. Under half—20 of 42—of the staff interviewed reported receiving no information at all on OHS incidents, and a quarter of the staff who did receive information reported receiving it irregularly.

These results indicate substantial room for improvement, particularly given the importance of regular communication on OHS issues, such as the trends and causes of OHS incidents in the workplace. No public hospital visited during this audit provided OHS incident reports to the work units. Part 3 section 21 and Part 4 of the OHS Act explicitly require that information that enables staff to perform their work safely and without risks to health is communicated to them. Communication is also an integral part of better practice as detailed in the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001.

The Department of Human Services—Public Hospital Sector Occupational Health and Safety Management Framework Model (OHS Management Framework) reinforces this by making communication and consultation key elements that must be in place for a health and safety system to work effectively. It states that 'consultation improves the operation of the documented system because it gives people information on health and safety activities and gives them a chance to contribute their thoughts and ideas'.

2.3.4 Occupational health and safety training in public hospitals is insufficient

Staff training is an important organisation-wide intervention aimed at preventing OHS injuries and controlling OHS risk. As part of this audit, a benchmarking survey was conducted with the OHS managers of 16 of the 17 largest public hospitals in Victoria—including five regional public hospitals. Over 84 per cent of the public hospital workforce is employed by these 16 public hospitals.

All public hospitals surveyed had in place extensive training programs which targeted key OHS risks such as manual handling of patients and materials and occupational violence. However, there was variation in the extent of training provided to frontline staff between public hospitals. For example:

- Training to manage occupational violenceis offered in 10 of the 16 public hospitals, even though this is consistently rated as a top three risk by the unit managers interviewed. Occupational violence also carries the greatest severity of all OHS risks.

- Nine of 16 public hospitals do not provide training to managers to assist them in managing occupational violence.

- Five of 16 public hospitals do not provide training to managers to assist in safe manual handling of people, despite this being the leading cause of WorkCover claims. It is pleasing to note, however, that all public hospitals did offer staff training in the manual handling of people.

The same survey found gaps in annual competency assessments:

- Only half—eight of 16—of the public hospitals offered competency assessments of occupational violence training.

- Eleven of the 16 public hospitals offered competency assessments of manual handling of people training.

Systems supporting and recording staff training were found to be inadequate. During site visits no public hospital could clearly map staff training and competency records to up-to-date staff training needs at that location. This means that although extensive training is offered, it is not possible for the public hospitals visited to demonstrate that all frontline staff have the initial training and ongoing competency assessments required to work safely. Adequate training of staff to enable them to work safely and without risk to health is required under Part 3 section 21(2)(e) of the OHS Act. A safety management system integrated with the public hospitals' human resources system could address this gap.

2.3.5 No assurance that public hospital staff safety is adequate

Under the OHS Act, the public hospital boards, as employers of staff, are responsible for OHS. Although the department is not responsible for the daily safety of public hospital staff, it is the manager of the Victorian health system and, therefore is responsible for the performance of public hospitals. The department does not require assurance from the boards of public hospitals that staff safety is of an acceptable standard.

2.4 Accountability for staff health and safety

Under the devolved governance model, described in Part one of this report, the board and Chief Executive Officer of a public hospital play key roles in providing a safe and healthy workplace.

OHS roles and responsibilities under this management structure need to be clear to effectively manage the safety of many hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of staff in a hazardous environment such as a public hospital. Those assigned responsibility need to understand what is required and be held to account so that gaps can be identified, and improvements in OHS performance achieved and sustained.

2.4.1 Responsibility is clearly identified and communicated

OHS policies and procedures at the four audited public hospitals were appropriate for the organisation and OHS risks, but did not establish measurable objectives and targets to reduce OHS injuries. Apart from this, policies were found to be:

- clear in setting out responsibilities

- inclusive of a commitment to comply with the OHS Act

- clearly documented, maintained and communicated to all staff

- reviewed periodically so that they remained relevant and appropriate to the organisation.

2.4.2 Managers are not accountable for occupational health and safety performance

Although OHS policies at each public hospital did state that the board, as employer, is ultimately accountable for occupational health and safety, there is a breakdown in the chain of accountability below the board:

- managers of clinical areas, where OHS risks predominantly present, are not held to account for the OHS performance of that unit or department

- ownership of OHS risk does not reside with the manager where the risk occurs.

None of the four audited public hospitals could demonstrate that mechanisms were in place to hold unit managers to account for OHS performance. For example, even though the position descriptions of nurse unit managers (NUMs)—who have direct responsibility for frontline staff and daily tasks—allocate them responsibility for overseeing OHS at the work unit level, half of the NUMs interviewed were not sure of their OHS responsibilities. Even those who understood their OHS responsibilities were not required to demonstrate how they fulfilled those responsibilities.

Managers to whom NUMs report are also not held to account for OHS performance. Position descriptions of executive directors, who are responsible for the day-to-day management of the clinical departments, assign responsibility for OHS in these areas. However, there was no evidence that they were ever held to account at the four audited public hospitals. The OHS Management Framework states that 'performance of OHS responsibilities is part of established job performance assessment process'.

The audit team did find some examples of better practice at public hospitals that were not part of this audit. For instance, one public hospital requires NUMs to report on OHS incidents and control measures in their unit. NUMs at this public hospital are also required to develop an action plan where gaps have been identified, and these action plans form part of their annual performance review.

2.4.3 Lack of occupational health and safety reporting against set targets

Managers need to receive regular reports against the targets set on OHS performance in the workplaces under their control if they are to be held to account. Neither reporting nor target setting was found at the work unit or department level of the public hospitals audited. Unit managers and clinical executive directors do not receive regular reports or trend data of OHS incidents in the work units for which they are responsible. As there are several unit managers rostered on during any month, without aggregated reporting it is difficult for each manager to know whether OHS performance is deteriorating or improving, or how their unit compares with other workplaces in the organisation. The OHS Management Framework emphasises that 'Health and safety performance is regularly reported'.

Similar to the absence of identified targets at the organisational level, there were no targets or performance setting processes to drive improvements at the work unit level. Better practice, as set out in the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001, emphasises that 'the organisation shall establish, implement and maintain documented OHS objectives and targets, at each relevant function and level within the organisation'. The OHS Management Framework also states that 'targets need to be set for the health and safety system so that system activity is directed towards specified achievements and performance in managing health and safety can be measured'.

2.4.4 Ownership of occupational health and safety risk

The Health Services Act 1988 requires boards of public hospitals to ensure that effective and accountable risk management systems are in place. The devolved governance model also expects that the board is fully informed in order to discharge its functions effectively and to ensure appropriate action is taken to manage and remedy issues as they arise.

OHS risk is one category of risk that has to be managed in the hospital environment. Organisational risk registers did include OHS risks, however, the risk registers at the four audited public hospitals identified the corporate services area as the owner of OHS risks despite OHS risk presenting predominantly in clinical departments. The disconnect between the owner of the risk and the line manager who can most influence staff who are exposed to—or even cause—the risk creates uncertainty and makes it difficult to drive improvements.

WorkSafe has acknowledged the need to provide more targeted training for boards of public hospitals to be able to comprehensively identify and manage OHS risks.

Recommendations

- That public hospitals and health services give higher priority to, and ensure accountability for, the management of occupational health and safety.

- That the Department of Health requires public hospitals and health services to annually assure it that they:

- manage occupational health and safety through a systematic approach in accordance with relevant legislation and standards

- provide workers with the highest level of protection against risks to their health and safety that is reasonably practicable in the circumstances.

- That WorkSafe provides support to the boards of public hospitals and health services on occupational health and safety leadership and requirements to raise awareness of their responsibilities to comply with occupational health and safety laws, so that public hospital staff receive the highest practicable level of occupational health and safety protection.

3 Hospital safety management systems

At a glance

Background

The management of staff safety in public hospitals should be systematic, and core safety elements—such as incident reporting, hazard assessment and control, and monitoring and review—should be integrated. This enables occupational health and safety (OHS) risks to be controlled effectively, particularly in a large and complex working environment such as a hospital.

Conclusion

Poorly integrated elements of safety management, and incomplete OHS information, undermine effective OHS management in public hospitals. A lack of analysis and evaluation further hinders improvement in OHS performance. Public hospitals should take a more systematic and comprehensive approach to OHS if sustained improvements to staff safety are to occur.

Findings

- The OHS incident reporting system used by public hospitals is not fit-for-purpose.

- OHS safety inspections vary widely between public hospitals and the structure and application of inspections could be improved.

- Assessment of OHS information, including factor analysis of OHS incidents, and evaluation of the effectiveness of controls, is lacking or inconsistent.

- Existing information of OHS risk is not routinely integrated or prioritised.

Recommendations

- That public hospitals and health services implement a systematic and integrated approach to OHS that complies with the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001, or an equivalent standard.

- That while public hospital industry OHS risk remains significant compared to other industries, WorkSafe annually confirms to the Department of Health that public hospitals and health services:

- comply with OHS legislation

- have in place a systematic approach to the control of OHS risks, and that effective risk control mechanisms exist.

3.1 Introduction

An occupational health and safety (OHS) management system includes the core elements of policy and procedures, staff consultation, communication of OHS information, reporting of incidents, hazard identification, assessment and control, and monitoring and evaluation.

The reasons that organisations use a safety management system include legal imperatives, ethical concerns, and financial returns through improved OHS injury and incident management. However, implementation of an effective safety management system should primarily be about improving staff health and safety.

It is important that the management of safety is systematic and core safety elements are integrated so that OHS risks can be controlled effectively in a large and complex working environment.

3.2 Conclusion

Poorly integrated elements of safety management, and incomplete OHS information, undermine effective OHS management in public hospitals. A lack of analysis, review and evaluation further hinders OHS performance. Public hospitals need to take a more systematic and comprehensive approach to OHS if sustained improvements to staff safety are to occur.

WorkSafe has agreed to provide support to the boards of public hospitals and public hospitals to assist board members to fully understand and comply with their OHS obligations.

3.3 Information on occupational health and safety incidents and risks

Multiple sources of information are critical to achieving and maintaining a strong safety culture. A combination of lead and lag (proactive and reactive) OHS indicators is necessary to capture OHS performance, identify gaps in the safety culture of an organisation and help in preventing major OHS events in the future.

A robust incident reporting system captures meaningful data about 'near misses' and OHS incidents so that OHS risks across the organisation can be analysed, and trends identified. Safety inspections aim to identify OHS hazards before an incident has occurred. Analysis of OHS data is necessary to understand the likely consequences of OHS hazards and incidents and whether risk controls are effective.

3.4 Incident reporting system

The incident reporting system used by public hospitals in Victoria is called the Victorian Health Incident Management System (VHIMS) and is licensed to the Department of Health (the department). Incident reporting is a key element of a safety management system. Over 2 500 OHS incidents were reported annually by around 16 000 employees of the four public hospitals visited.

During the site visits, VHIMS was found to be not fit-for-purpose as an OHS incident reporting system. It does not enable, as the Department of Human Services—Public Hospital Sector Occupational Health and Safety Management Framework Model (OHS Management Framework) states, 'a formal process by which accidents, incidents, near misses or potentially unsafe situations are reported to people with the responsibility to investigate and institute any required corrective actions'. Issues with the VHIMS system include:

- Some mandatory fields—such as whether the OHS incident was disclosed to visitors of patients—are of no relevance to OHS incidents as they are designed for clinical incidents. Repeatedly filling in irrelevant fields makes reporting unnecessarily time consuming, which can deter staff from reporting minor incidents and near misses.

- There are no fields to capture vital OHS information, such as:

- signs and triggers leading to frequent occupational violence incidents—for example, assaults—which carry the most severe consequences for public hospital staff

- OHS training of the staff member who reported the OHS incident.

- Staff interviews and site visits showed that categories to classify OHS incidents are complicated, unclear, too numerous—124 to choose from—and sometimes irrelevant or overlapping. For example, occupational violence can be classified as 'inappropriate contact' or 'physical aggression'. This limits the usefulness of aggregated management reports, and hinders accurate and consistent input by the reporting staff member.

- The incident severity rating is also of questionable value as it:

- is based on clinical risk and is inappropriate for OHS incidents. For example, a patient needing medical attention as a consequence of a patient safety incident is rightly seen as significant and is assigned a high severity rating. On the other hand, staff needing medical attention after an OHS incident may not necessarily be given such a high rating.

- Does not capture probable consequences if the incident occurred again, or the likelihood of a repeat occurrence. A near miss arising from faulty equipment could have much graver consequences next time.

Interviewed staff report—and site visits confirm—that training in the incident reporting system is inadequate, with brief overviews given during staff induction and no follow-up training offered at any of the public hospitals visited. The system complexity requires a more in-depth approach, particularly for workers who may not be computer proficient.

Of the 42 staff interviewed, 36 reported that the incident reporting system was not user friendly. All 16 OHS directors surveyed stated that they believe there is under-reporting of both OHS incidents and near misses.

Code blacks are called in public hospitals when staff are physically threatened, and each is recorded in a security log. Comparison at one public hospital between this log and occupational violence incidents in VHIMS found that 70 per cent of incidents where staff were physically threatened and a code black was called were not reported in VHIMS. This is a systemic and longstanding issue, as both the 2005 Victorian taskforce on violence in nursing report and the 2011 Parliamentary Inquiry into Violence and Security Arrangements in Victorian Hospitals and, in particular, Emergency Departments found that the incident reporting system was difficult for staff to use, and that under-reporting of OHS incidents was a significant issue.

Reporting was also not timely, which means that staff may be exposed to an OHS risk several times before control measures can be put into place or management is aware of the hazard. At one site, 87 per cent of OHS incidents were not entered into VHIMS within seven days of the incident occurring. No reason was given for this, although staff report that entering an OHS incident into VHIMS often has to wait until a shift is finished or a computer is available.

The VHIMS used by hospitals has been designed to capture clinical patient safety incidents and has not been appropriately modified to readily capture OHS incidents. This undermines the stated departmental VHIMS project objective to 'develop a statewide, standard methodology, for the way incident information is reported within publicly-funded health services'. Figure 3A illustrates shortcomings in VHIMS for one particular OHS risk—occupational violence.

Figure 3A

Gaps in reporting occupational violence incidents

|

Element |

Example |

|---|---|

|

Accurate |

Comparison at one public hospital between the security log, which records each time assistance is provided to a threatening situation, and occupational violence incidents in VHIMS found that 70 per cent of incidents where staff are physically threatened were not reported in VHIMS. |

|

Comprehensive |

Available fields do not capture necessary OHS information—for example the signs or triggers, and previous staff training, leading up to an occupational violence incident. Public hospitals report that this information is vital to improving the response to occupational violence. |

|

Meaningful |

Some mandatory fields are of no relevance to occupational violence incidents as they relate to clinical incidents, for example, whether visitors were informed of the OHS incident. |

|

Consistent |

Occupational violence can be classified in different ways which leads to inconsistency of reporting. Staff were found to report the same type of incident as:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The department has acknowledged the shortcomings with VHIMS. It has indicated it is committed to improving the data but has not yet set out which specific shortcomings will be addressed and how these will be addressed.

3.5 Safety inspections

Regular and planned checks of the workplace are essential to make sure risk controls are effective and new hazards have not arisen. The OHS Management Framework states that inspections should be documented and corrective actions identified and implemented.

All public hospitals visited had an ongoing program of safety inspections. Figure 3B summarises the elements of the safety inspections found at the four public hospitals. Safety inspections varied widely in terms of frequency, compliance of work units in completing the inspections, follow up of actions identified during an inspection, and the type of hazard or risk that was required to be assessed.

Figure 3B

Safety inspections

|

Public |

Public |

Public |

Public |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Twice yearly |

Monthly |

Quarterly |

Monthly |

|

|

Number of OHS risks covered |

8 |

9 |

6 |

2 |

|

Completed at all work units |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Implementation of controls checked |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✓ |

|

Categories of risk and hazard identified |

||||

|

Physical work environment |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Manual handling |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Fall/trip hazard |

✓ |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

|

Occupational violence |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

|

Infection/sharps |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

|

Fire and evacuation |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Equipment/electrical hazard |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

|

Hazardous substances |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

|

Radiation |

✗ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

OHS safety inspections conducted by public hospitals could be improved by:

- targeting areas of higher risk within the hospital—such as the emergency departments

- completing scheduled safety inspections

- implementing risk controls identified through the safety inspection process

- integrating information gained from safety inspections with other OHS risk information.

3.6 Analysis, assessment and evaluation

The value of incident reporting and safety inspections goes beyond information gained in individual reports—sustained improvement in the safety culture derives from analysing, investigating, identifying and implementing controls, and monitoring the effectiveness of controls. Assessment and review can reveal trends and allows an organisation to learn from OHS incidents and improve.

There is little evidence of such analysis being undertaken by the audited public hospitals. Specifically:

- Only one audited public hospital could provide any evaluations of OHS initiatives or interventions. This is contrary to the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001, which clearly states that hazard identification, risk assessment and control measures should be regularly evaluated.

- There was little or no evidence of routine root cause analysis, a key step in understanding the causal factors underlying OHS/workplace risk. The only circumstance where full investigation was undertaken by an audited public hospital was after an injury had occurred and a WorkCover claim made.

- Public hospitals did not undertake a training needs analysis, where the type and frequency of training and assessment for different roles is determined based on exposure to OHS risk. The OHS Management Framework states the need for 'a process for identifying health and safety needs and for meeting these needs'.

Investigation and follow up of OHS incidents did not routinely occur in the four audited public hospitals. One public hospital demonstrated better practice by following up over 98 per cent of OHS incidents reported. However, another public hospital only followed up 35 per cent of the 586 OHS incidents reported over a twelve-month period. Incidents should be followed up to understand and, if possible, eliminate the cause of the incident to minimise the likelihood of future injury. The OHS Management Framework states that 'Managers receive incident reports, carry out investigations to identify why an incident happened and decide on corrective action to ensure it doesn't happen again'.

The depth of analysis was also questionable. Only six of the 24 nurse unit managers (NUMs), who are responsible for investigations, stated that these investigations identified the root cause of the incident. Three of the 24 NUMs leading the investigations did not know how to conduct a root cause analysis or how to establish causal factors.

3.7 Quality assurance and review

Quality assurance of the safety management system is important to demonstrate whether the system is operating effectively and efficiently and is meeting organisational objectives. A survey of OHS directors across 16 major public hospitals indicated wide variation in assuring the quality of safety management systems. From 2010 to 2012, six public hospitals did not audit their safety management system at all, four were internally audited and six were externally audited against the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001. This standard emphasises the importance of periodic audits and management review of the safety management system.

A major national accreditation body for public hospitals, the Australian Council on Healthcare Standards (ACHS), reviewed performance of public hospitals from 2007 to 2010, and found that one of seven areas most in need of improvement nationally was 'robust safety management systems'. This is consistent with the findings of this audit.

3.8 Integration of occupational health and safety risk information

There was little evidence of an integrated approach to OHS risk management that combined a proactive hazard analysis with reactive controls and review of OHS outcomes, including incidents and injuries. Only one of the four audited public hospitals attempted to integrate all the OHS risk information collected into a single risk register, but not all relevant information was taken into account. This makes it difficult to have an overall view of the organisational OHS risk profile or a clear prioritisation of effort.

Figure 3C illustrates the variability in the OHS information reported to senior management and the board. Incomplete information can make it difficult for the board to adequately fulfil its responsibility in providing a safe and healthy environment for staff. An OHS safety management system would assist public hospitals to readily integrate the broad range of information necessary to manage a challenging OHS environment.

Figure 3C

Variability in the occupational health and safety information reported to senior management and the board

|

Public |

Public |

Public |

Public |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

OHS-specific risk register |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

|

Sources of OHS information integrated in management reporting |

||||

|

OHS injury data |

✗ |

✓ |

✓ |

✓ |

|

Safety inspections |

✓ |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

|

OHS incident data |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

|

Staff observations |

✓ |

✗ |

✗ |

✗ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Poor integration of risk information appears to be a common shortcoming of hospitals nationally, according to a review by ACHS—a major national accreditation body for public hospitals. ACHS reviewed performance of public hospitals from 2007 to 2010, and found the second most prevalent challenge nationally to be the 'integration of organisation-wide risk management policy and system to ensure corporate and clinical risks are identified, minimised and managed'.

Recommendations

- That public hospitals and health services implement a systematic and integrated approach to occupational health and safety that complies with the Australian Standard on occupational health and safety management systems, AS/NZS 4801:2001, or an equivalent standard.

- That while public hospital industry occupational health and safety risk remains significant compared to other industries, WorkSafe annually confirms to the Department of Health that public hospitals and health services:

- comply with occupational health and safety legislation

- have in place a systematic approach to the control of occupational health and safety risks, and that effective risk control mechanisms exist.

4 Managing sector-wide occupational health and safety risk

At a glance

Background

Collecting and analysing sector-wide information on existing occupational health and safety (OHS) risks and emerging trends is important in a hazardous workplace such as a public hospital. Regular monitoring can identify upward trends which can indicate risks are not being controlled and that staff are being placed at unnecessary risk while at work. Responding at a systemic level may be necessary where an OHS risk presents at many hospital worksites.

Conclusion

Neither the Department of Health nor WorkSafe has a comprehensive understanding of sector-wide OHS risk in public hospitals. This gap in knowledge hinders their ability to know, or appropriately respond to, OHS risks systematically. This is unacceptable given the hazardous hospital workplace and the size of the public hospital workforce, which is the largest workforce in the public sector.

Findings

- The only sector-wide monitoring of public hospitals' OHS risk is that conducted by WorkSafe on injury claims and premiums made to it. On its own, this does not capture underlying OHS incidents or emerging trends in the hospital workplace.

- WorkSafe cannot demonstrate that its projects targeting public hospitals worksites are effective in reducing OHS risk.

- Collaboration between the Department of Health and WorkSafe has been poor over the past five years.

Recommendations

- That WorkSafe identifies sector-wide OHS risks in public hospitals and provides this information to the Department of Health, public hospitals and health services.

- That the Department of Health and WorkSafe collaborate to assist public hospitals and health services to control the highest OHS risks.

4.1 Introduction

Collecting and analysing sector-wide information on existing occupational health and safety (OHS) risks and emerging trends is important in an extensive health system of 84 public hospitals. Regular monitoring can identify upward trends which can indicate risks are not being controlled and that staff are being placed at unnecessary risk while at work. Responding at a systemic level may be necessary and more efficient where an OHS risk presents at many hospital worksites.

Without adequate monitoring and a sector-wide response, more frequent and more serious OHS injuries can occur. This has the potential to affect not only the public hospital workforce but the quality of care patients receive. An increase in frequency or seriousness of OHS incidents can also place an additional burden on the health budget through increased WorkCover premiums and an increase in the temporary replacement of injured staff across the sector.

4.2 Conclusion

Neither the Department of Health (the department) nor WorkSafe has a comprehensive understanding of sector-wide OHS risk in public hospitals. This gap in knowledge hinders the ability of the department and WorkSafe to know, or appropriately respond to, OHS risks systematically. This is unacceptable given the hazardous hospital workplace and the size of the public hospital workforce—which is the largest workforce in the public sector.

4.3 Monitoring sector-wide occupational health and safety risk

4.3.1 Public hospitals

The Health Services Act 1988 makes it clear that while the boards of public hospitals are ultimately accountable for the governance of the staff they employ, the daily management of OHS is a responsibility of the chief executive officer. The devolved governance model in the Victorian health system is designed to allow decisions to be made that are most effective for an individual health service, and appropriate for the local community.

The board members and chief executive officer have a clear legislative responsibility to monitor OHS risks in the organisation they serve. However, boards are not responsible for monitoring sector-wide trends and emerging OHS risks.

4.3.2 The Department of Health

The department does not monitor or review OHS performance of public hospitals. It does require public hospitals to report on one OHS risk—occupational violence against nurses. However, no analysis is undertaken of the occupational violence data and no feedback is provided back to public hospitals that employ the nurses. There is no reporting requirement for other, more costly OHS risks, such as manual handling of people and material.

Under the Occupational Health and Safety Act 2004 (the OHS Act) and devolved governance model, the department does not have an operational role in OHS risk management and it does not believe it has a role in responding to incidents that have occurred in hospitals, with the exception of disaster responses.

The Victorian health services governance handbook states that the department plays a key system-level role in the performance of health services. This involves 'shaping and enabling health services to function effectively'. The Health Services Act 1988 states that part of the department's role is to encourage safety and improvement in the quality of health services provided by healthcare facilities.

However, the exact role of the department—as the health systems manager—in worker health and safety is not clear. Key documents governing the relationship between the department, the Minister for Health and public hospitals make no mention of OHS management in public hospitals, or outline the department's expectations. Figure 4A summarises the key documents governing the relationship between the department, the minister and public hospitals.

Figure 4A

Relevant governance documents published by the department

|

Guidance |

Purpose |

Relevance to OHS |

|---|---|---|

|

The Victorian health services governance handbook |

Assists public hospital board members and other parties to better understand the operating environment of public health services |

Does not mention OHS management or the department's expectations |

|

Victorian health service performance monitoring framework (2012–13) |

Describes the mechanisms the department uses to formally monitor health service performance |

Does not prescribe any OHS performance indicators for public hospitals |

|

Victorian health policy and funding guidelines (2012–13) |

Part one: Key changes and new initiatives. Outlines budget areas of focus and significant policy or program changes |

No part mentions OHS management or the department's expectations |

|

Part two: Health operations. Explains how public hospitals are expected to operate, including key legal, reporting, financial and operational obligations |

||

|

Part three: Technical guidelines. Sets out the technical aspects of hospital operations |

||

|

Statements of Priorities |

Annual accountability agreement between each public hospital and the Minister for Health |

Does not mention OHS management |

|

Victorian health incident management policy |

Provides guidance to public hospitals for a structured incident management review process |

Incident management system is used by public hospitals to report OHS incidents, but OHS is not identified in the policy—it focused on patient safety |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The department receives notification of individual public hospital annual WorkSafe premiums for the purposes of cash flow adjustments which enable public hospitals to pay the required premiums in one lump sum and to take advantage of available discounts. However, the department does not monitor variations in premiums from one year to the next as a measure of performance in this field. This is a missed opportunity to both drive improved performance and contain costs associated with WorkSafe premiums. Over the past five years, the WorkCover premium paid by Victorian public hospitals totalled

$387 million, with $80.5 million paid in 2012–13 alone.

4.3.3 WorkSafe

WorkSafe monitors the OHS performance of the hospital sector and all other industries in Victoria primarily through WorkCover serious injury claims and premiums. This is because WorkSafe is only notified of serious injuries and when claims are made to WorkSafe. Employers pay an annual premium to WorkSafe, which is determined by the employer's industry and its claims performance and total remuneration relative to other employers in that industry group.

On its own, this data does not capture emerging OHS risks and underlying OHS incidents which do not result in a workplace injury or affect an employer's premium. Yet the minor OHS incidents are important as they can indicate whether existing risk controls are failing before a serious OHS incident occurs. However, there are practical limits to WorkSafe's ability to monitor all incident data across over 240 000 Victorian worksites.

4.4 Responding to sector-wide occupational health and safety risk

4.4.1 WorkSafe

WorkSafe, with inspectors appointed under the OHS Act, is in the best position to respond to sector-wide OHS risks. WorkSafe use approximately 40–50 per cent of its inspector resources to fulfil mandatory functions required under the OHS Act—such as emergency response services. The remainder of its inspector resources go towards projects that aim to reduce OHS risks and injuries in all Victorian workplaces.

This audit focused on those WorkSafe projects that target public hospitals. Projects have used WorkSafe inspectors to provide guidance, assistance and enforcement activities including completing compliance checklists, identifying safety issues and issuing improvement notices, and providing information to educate and raise awareness within the hospital sector of risks such as occupational violence.

Projects to reduce occupational health and safety risk

WorkSafe does not know which project is most effective or whether these activities and investment are effective in reducing OHS risk in public hospitals. This is because WorkSafe has not objectively evaluated its projects to determine what outcomes have been achieved. WorkSafe's project management framework is inadequate as the majority of projects do not have clear objectives, justifiable selection criteria of hospital worksites, contingency planning or monitoring of performance indicators.

Inadequate project management

The audit team examined all 18 WorkSafe projects from 2007 to 2012 that targeted public hospitals. These projects focused on OHS risks such as manual handling, occupational violence, slips, trips and falls.

WorkSafe's management of these 18 projects is inadequate:

- Selection of hospital worksites for project activity is not based on clear criteria and is not systematic. Public hospital worksites with a higher standard claim rate, perfull-time equivalent staff, did not consistently receive a greater number of project visits than hospitals with lower claim rates.

- Project objectives are not clear in 14 of the 18 projects.

- WorkSafe does not adapt project activities to ensure projects are completed. There is no contingency planning despite the changing demands on its inspectors, who are primarily responsible for project implementation. Just over half—10 of 18—of the projects never reached completion.

- Performance during a project is not measured regularly against stated indicators. It was not clear how much of a target—such as achieving an 8per cent reduction in the number of claims per 1 000 staff—could be attributed to an individual project, or when such an outcome could be reasonably expected to be realised.

WorkSafe cannot demonstrate that it appropriately targets efforts to decrease OHS risk in public hospitals. Robust evaluation of projects was absent. It was not possible to assess whether project activity was effective, or to establish the links between resources and project inputs and a reduction in workplace risk at the targeted hospital worksites. This means that, although projects may have been effective, improvements arising from them cannot be identified, substantiated or incorporated into WorkSafe's operations. Further, recommendations are not documented or identified for future action, and findings from projects are not routinely communicated back to public hospitals.

WorkSafe's new approach

During this audit, WorkSafe has acknowledged shortcomings with its project management framework. It is developing a new model for targeting risk in all industries, with an ongoing program focus on the top OHS risks, rather than discrete projects of shorter duration. A time line for this new approach, approved in principle by WorkSafe, is shown in Figure 4B. WorkSafe has committed to fully implementing this new approach by July 2014.

Figure 4B

WorkSafe's new program approach to reducing OHS risk

|

Date |

Stage |

|---|---|

|

September 2013 |

Review current project management framework and develop an integrated risk prioritisation framework |

|

February 2014 |

The draft risk prioritisation framework completed and the transition process for existing projects to the new program approach completed |

|

March 2014 |

Finalise risk prioritisation framework and confirm new program areas |

|

July 2014 |

Commence new programs |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

4.4.2 The Department of Health

The department, as the health system manager, needs to be able to respond to systemic OHS risks. It acknowledges this responsibility, but is hindered in fulfilling this role as it does not have the information available on sector-wide OHS risks.

Over the past decade, the department has put in place some initiatives to assist OHS management in hospitals. For example, it has:

- facilitated OHS forums from 2005 to 2011, which brought together WorkSafe, the department and OHS practitioners at public hospitals

- published policy on one OHS risk, occupational violence in 2007

- developed the Public Hospital Sector Occupational Health and Safety Management Framework Modelin 2003