Operational Effectiveness of the myki Ticketing System

Overview

In July 2005, the state committed almost $1 billion to develop myki to replace the ageing Metcard system. The myki system was expected to deliver significant benefits to Victorians including more efficient, attractive and reliable transport services, and the best value solution at the lowest whole-of-life cost. Public Transport Victoria (PTV) is currently planning to retender the myki contract which expires in 2016.

This audit examined myki's operational effectiveness, and whether the outcomes and benefits expected from its introduction are being achieved. The audit found that that myki experienced significant delays and related cost increases that have compromised achievement of its original business case objectives and benefits.

Poor initial planning resulted in myki's original scope and contract being vaguely specified and overly ambitious. This produced significant delivery risks that were poorly managed because of shortcomings in the state's initial governance and oversight of the project.

Since its creation in 2012, PTV has improved oversight and management of the myki contractor. However, significant risks to the state remain due to weaknesses with the contract’s performance regime and the compressed time frames for the myki retender.

PTV needs to urgently address these issues to avoid perpetuating past mistakes.

Operational Effectiveness of the myki Ticketing System: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2015

PP No 40, Session 2014–15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Operational Effectiveness of the myki Ticketing System.

The audit examined the operational effectiveness of the myki ticketing system. It assessed whether the arrangements in place for the system's implementation and ongoing management are effective and whether the expected outcomes and benefits from the introduction of myki for users, operators and the state have been, or are on track to being, achieved.

I found that the myki system has experienced significant delays in implementation and cost increases, largely as a result of deficiencies in the original governance, project planning and contractual arrangements. This has resulted in a poor outcome for Victoria's public transport system and users, which has compromised achievement of myki's original business case objectives and related benefits.

Since its creation in 2012, Public Transport Victoria has improved oversight and management of the myki contractor, however, significant risks to the state remain due to weaknesses with the contract's performance regime and the compressed time frames for the myki retender.

Public Transport Victoria needs to urgently address these issues to avoid perpetuating past mistakes.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

10 June 2015

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Steven Vlahos—Engagement Leader Tony Brown—Acting Engagement Leader Rocco Rottura—Team Leader Hayley Svenson—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Dallas Mischkulnig |

A well designed and implemented ticketing system is crucial for the effective and efficient functioning of Victoria's public transport system. It enables commuters to easily access services, and provides important usage information for agencies to plan and manage the system effectively.

In 2005, the state committed almost $1 billion to develop myki by 2007 to replace the ageing Metcard system, and operate myki for 10 years. It justified the investment on the premise that myki would deliver significant benefits to Victorians including more efficient, attractive and reliable transport services, and because it was the best value solution at the lowest whole-of-life cost. Public Transport Victoria (PTV) is currently planning to retender the contract for myki's continued operation which expires in 2016.

In this audit, I examined myki's operational effectiveness, and whether the outcomes and benefits expected from its introduction are being achieved. I found that myki experienced significant delays and related cost increases that have compromised achievement of its original business case objectives and benefits.

The time taken to develop and implement myki more than quadrupled from the initial expectation of two years, to in excess of nine years. Consequently, the state has incurred significant, additional unanticipated costs with myki's budget increasing by around $550 million, or 55 per cent.

Poor initial planning resulted in myki's original scope and contract being vaguely specified and overly ambitious. This produced significant delivery risks that were poorly managed because of shortcomings in the state's initial governance and oversight of the project.

While PTV has since improved oversight of the myki contractor and related contractual arrangements, significant risks to the state remain. Specifically:

- PTV does not yet possess a complete and reliable picture of myki's operational performance, due to shortcomings in performance monitoring

- the benefits and outcomes sought from the myki retender have not been clearly defined

- none of the agencies responsible for myki have assessed if it has achieved any of its expected benefits—despite previous commitments to the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee in 2012 that this would occur

- compressed time frames for the myki retender risk exposing the state to significant additional costs.

PTV needs to urgently address these issues and assess the residual benefits achievable from myki going forward, to optimise value from the state's significant and ongoing expenditure. However, I am concerned that current Cabinet-in-confidence conventions pose a barrier to this work. These prevent agencies from accessing the full business case for myki needed to conduct a benefits review, and for all other current and major state investments that were approved by former governments.

This is impeding the effective governance of both myki, and all other major investments by the state in projects whose life cycle usually extends beyond the term of Parliament and any government. It is also compromising the effectiveness of the state's Gateway Review and High Value High Risk framework.

I note that in 2012 the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) wrote to the Department of Premier and Cabinet—the custodian of these conventions—recommending that they be amended to exempt full business cases for all major projects approved by Cabinet. However, this has yet to be resolved.

It is nevertheless encouraging that the government recently dispensed with these conventions to release the full East West Link business case in the public interest. There is a need to extend this practice to all business cases for major state investments approved by current and former governments.

Urgent action is required to address this issue as it risks reducing the role of any business case to simply being a hoop that agencies must jump through to get the initial approval, which can then be disregarded following a change of government. It also heightens the risk, particularly in the case of myki, of history repeating itself.

The challenges identified by my audit are longstanding and reflect recurring issues previously highlighted by successive audits of public transport and related ticketing systems undertaken by my office.

Our 1990 audit Met Ticket, and 1998 audit Automating Fare Collection: a major initiative in public transport, both found that fast tracking the development of ticketing systems led to poor planning, successive delays and blowouts in implementation which exposed the state to significant cost.

Additionally, my 2014 audit Coordinating Public Transport and 2015 audit Tendering Metropolitan Bus Contracts found recurring shortcomings in performance data and related monitoring activities, which offer little assurance the state is achieving adequate value from these services.

I made five recommendations which reinforce the need for PTV to strengthen its monitoring of myki prior to awarding the new contract. I have also recommended that central agencies advise the government on the impact of current constraints to accessing full business cases posed by existing Cabinet conventions.

I intend to monitor implementation of these recommendations.

I wish to thank the staff at PTV, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources and DTF for their constructive engagement throughout the audit process.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

June 2015

Audit Summary

Background

In July 2005, the state entered into a contract to develop myki, a smartcard public transport ticketing system to replace the ageing Metcard system.

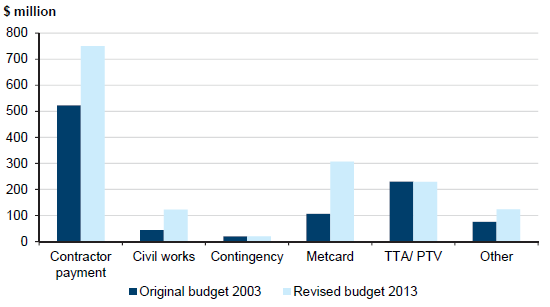

Just over half of myki's almost $1 billion initial budget—around $520 million—was for establishing the system by 2007 and operating it for 10 years. The remainder was for operating Metcard in parallel with myki during the transition, and to cover the former Transport Ticketing Authority's (TTA) related costs for managing Metcard and its replacement.

Metcard was switched off in December 2012 following the completion of myki's rollout across metropolitan services. Public Transport Victoria (PTV) has since assumed responsibility for all of TTA's related functions and finalised myki's rollout across selected regional services in February 2014.

It was expected that myki would deliver around $6.3–$10.8 million per year in economic benefits to the state and its objectives included:

- enhancing the community's image of public transport

- providing the best value-for-money solution at the lowest whole-of-life cost

- being operational at, or shortly after, Metcard's expiry in 2007.

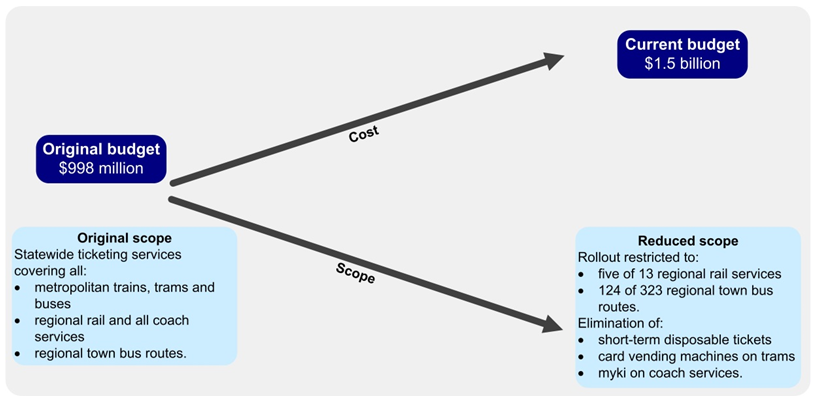

However, there have been significant implementation issues with the system. Specifically, the time taken to design and deliver it more than quadrupled from the original expectation of just two years, to in excess of nine years. This has led to significant unanticipated additional costs—resulting in a $550 million, or 55 per cent, increase on the project's original budget.

The operational performance of myki has also attracted significant complaints and criticism from users. In particular, overcharging has been, by far, the single most common complaint from users about myki since its rollout.

In response to these challenges, the former government commissioned a review of myki in late 2010 to determine its future. It decided to proceed with implementing myki, but with modifications. The resulting changes substantially reduced myki's initial scope, further extended its delivery time frames, and fundamentally changed the way the state pays for the system.

The current myki contract is due to expire in June 2016, with an option to extend it for a further six months to December 2016. PTV is currently planning the myki retender, which it expects to complete by November 2016.

Objectives of the audit

The audit examined the operational effectiveness of the myki ticketing system. It assessed whether the arrangements in place for the system's implementation and ongoing management are effective and whether the expected outcomes and benefits from the introduction of myki for users, operators and the state have been, or are on track to being, achieved.

Conclusions

The implementation of myki experienced significant delays and related cost increases, due largely to deficiencies in the original contract and governance arrangements.

This has resulted in a poor outcome for Victoria's public transport system and users, which has compromised achievement of myki's original business case objectives and related benefits.

The overly ambitious and vaguely specified initial project scope and contract for myki contributed to this outcome.

These deficiencies meant the state was not in a position to assure it was paying for a ticketing system that met clearly articulated and agreed performance standards—particularly during the initial build and rollout.

Shortcomings in both cross-agency coordination and oversight of the initial project conspired with these issues to produce significant delivery risks that were not well managed. Collectively, these challenges undermined the viability of the original contract.

PTV has since improved its oversight and management of the myki contractor by strengthening related governance and contractual arrangements.

However, significant risks to the state remain. Specifically:

- PTV does not yet possess a complete and reliable picture of myki's operational performance due to weaknesses with the contract's new performance regime and its implementation

- the benefits and outcomes sought from the myki retender have not been clearly defined, which reduces transparency and accountability for myki's future performance

- compressed time frames for the myki retender, caused by previous delays and the imminent expiration of the current contract, risk exposing the state to significant additional costs.

PTV needs to urgently address these issues to avoid perpetuating previous mistakes, and to ensure that the state can maximise value from the future operation of myki.

Findings

Governance and contractual arrangements

The original myki governance arrangements were previously examined by:

- the Victorian Ombudsman's 2011 Own motion investigation into ICT-enabled projects jointly conducted with VAGO

- the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee's 2012 Inquiry into Effective Decision Making for the Successful Delivery Of Significant Infrastructure Projects

- related internal reviews undertaken by the Department of Treasury and Finance in 2011 and 2014.

These reviews consistently found that the roles and responsibilities of key agencies initially charged with myki's development were neither well defined nor effectively implemented. This led to uncertainty and delays in decision-making, particularly during myki's initial build and rollout.

Critical weaknesses highlighted by these reviews include:

- a lack of clarity regarding whether the former Department of Transport (DOT) or TTA was the ultimate decision-maker on myki matters

- ineffective communication between DOT and TTA impeded TTA's implementation of DOT's ticketing policies and TTA's capacity to meet prescribed deadlines

- poor engagement between the myki contractor and public transport operators

- TTA did not possess the capacity and capability needed to effectively manage the project.

In combination with myki's ambitious initial scale and poorly defined functional performance requirements, these issues contributed to significant delays in implementing the new ticketing system and compromised the viability of myki's initial contract. This precipitated six major contractual amendments as the project encountered significant difficulties.

These amendments strengthened the contract's viability but at the cost of substantially reducing myki's scope, increasing its total cost to the state, and extending its delivery time frames by a further seven years. Collectively, these issues have compromised the achievement of myki's originally intended benefits.

PTV's establishment in April 2012, as the new authority responsible for managing myki and Victoria's public transport system, has led to improvements in the governance and contractual arrangements in place for myki.

This has resolved the previous disconnect in responsibilities for public transport ticketing policy development and implementation that hampered TTA's management of myki. The new arrangements have also clarified PTV's role, decision-making authority and accountability for managing the myki contractor.

Monitoring myki's operational performance

The performance regime in the initial myki contract was complex, onerous and, with 81 measures, difficult to apply in practice. Further, the performance measures only applied once myki was fully operational.

The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) raised concerns with the initial performance regime in successive briefings to the former Treasurer in 2012 and 2013 noting that the performance measures were 'difficult to interpret and apply' and that a new regime was needed to drive 'appropriate behaviours' from the contractor.

PTV subsequently developed a new performance regime which it implemented in April 2013. The new regime has:

- introduced incentives for the contractor to promptly address faults with myki devices and related software upgrades that previously disrupted system operations

- increased the contractor's focus on assuring the accuracy of financial information recorded by the system.

However, fundamental issues remain. Specifically:

- current measures in the contract's new performance regime do not address all key aspects of performance

- there is no framework for assessing myki's overall effectiveness, efficiency and benefits

- PTV does not adequately assure the reliability of results, reported by the contractor, that underpin incentive payments.

PTV needs to urgently address these issues as they are impacting on the effectiveness and integrity of the performance regime.

Despite PTV not being able to adequately assure the reliability of the contractor's performance data, it has paid $1.4 million in performance-linked incentives and has applied abatements totalling $325 000, between April 2013 and December 2014.

Assessing the achievement of myki's benefits

None of the agencies responsible for myki have assessed whether it has achieved any of its expected outcomes and benefits, including providing value for money.

Consequently, there is no evidence myki has satisfactorily achieved any of its original business case objectives.

In 2012, DOT, TTA and DTF advised the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee that a review assessing the extent to which myki's benefits have been realised would be undertaken following the completion of its rollout. This has not yet occurred.

While DTF subsequently prepared a 'lessons learnt review' in 2014 which identified valuable insights into the issues affecting myki's delivery, including the appropriateness of governance and contractual arrangements, the review did not assess whether any benefits had been achieved.

Instead DTF sought, and received, an exemption from the former Treasurer in 2013 from performing the benefits review required by the Gateway Review process. It justified this on the grounds that the business case had not been updated since the project was first approved, and because it was unable to access it, given it was a Cabinet document of the former government.

This advice was deficient. While DTF correctly noted the constraint to accessing the business case posed by existing Cabinet conventions, it did not advise the Treasurer that this impedes:

- the effective governance of myki, and of all major state investments requiring a full business case to be approved by Cabinet

- DTF's oversight of these projects under the High Value High Risk framework.

Urgent action is required to address this issue as this risks diminishing the value and role of a business case. It reduces it to simply being a hoop agencies jump through to get the initial approval, which they can then disregard following any change of government.

The original business case committed almost $1 billion of taxpayer funds on the premise that myki would deliver significant benefits to Victorians. It is therefore critical that PTV and DTF assess the benefits achieved to understand the nature and extent of any benefits that remain achievable going forward. This will help assure full accountability for and transparency of the achievements from this significant expenditure of taxpayer funds.

While the current time lines may mean that it will be difficult to undertake a post-implementation review against the business case in time to inform the retender, such a review would provide PTV with important insights on the actions it should take to optimise achievement of benefits in the current retender and next iteration of myki.

Notwithstanding, as noted earlier, the substantial reduction in myki's scope over time, coupled with significant increases in the original project time line and budget, mean that it is almost certain that myki has failed to satisfactorily achieve its original business case objectives and assumed benefits.

Planning for the myki retender

The myki retender is occurring under significant time pressure due, in part, to previous delays in implementing myki.

These delays have forced PTV to commit to exercising its option to extend the current contract for a further six months to December 2016 in order to accommodate the retender evaluation and transition period. This has virtually eliminated any contingency in the retender schedule.

Consequently, there is a significant risk that the tender outcome will not be finalised before the current contractual term expires. If this occurs, it may seriously worsen the state's negotiating position and expose it to significant additional costs.

The current contract provides no option for further extensions. This means there is no certainty that this can feasibly occur. Any significant extension of the transition and handover period beyond December 2016, if a new contractor is appointed, is likely to require extensive negotiations with the incumbent operator and substantial additional funds to cover unanticipated costs.

PTV is taking steps to mitigate the risk of this occurring and, in so doing, is considering the relevant lessons from the previous myki contract. However, to achieve this PTV needs to effectively manage the retender and related schedule.

PTV is yet to clearly define the expected outcomes and benefits from the retender process and the new contract. This reduces the transparency of the new contract's impact, and accountability for PTV's related performance.

PTV needs to address this issue as a matter of urgency as it has the potential, yet again, to compromise the achievement of planned outcomes from this critical system.

Recommendations

That Public Transport Victoria:- strengthens its performance monitoring arrangements for myki prior to awarding the new contract by:

- assessing the adequacy of existing performance measures and standards for driving improvements in performance

- developing new measures addressing how well the equipment operates as distinct from the length of time for which it is available

- reviewing on at least an annual basis and, where necessary, adjusting performance incentives to support further improvements in performance or achievement of emerging service priorities

- developing a broader framework to assess myki's efficiency and effectiveness and its impact on improving performance and management of the public transport system

- uses its right under the contract to audit and verify the performance data provided by the contractor

- seek access to the original myki business case in consultation with the Department of Premier and Cabinet and:

- conduct a post-implementation review of the myki project against its original objectives and benefits

- incorporate relevant lessons into the new myki contract as soon as possible and in any future subsequent procurement of public transport ticketing services.

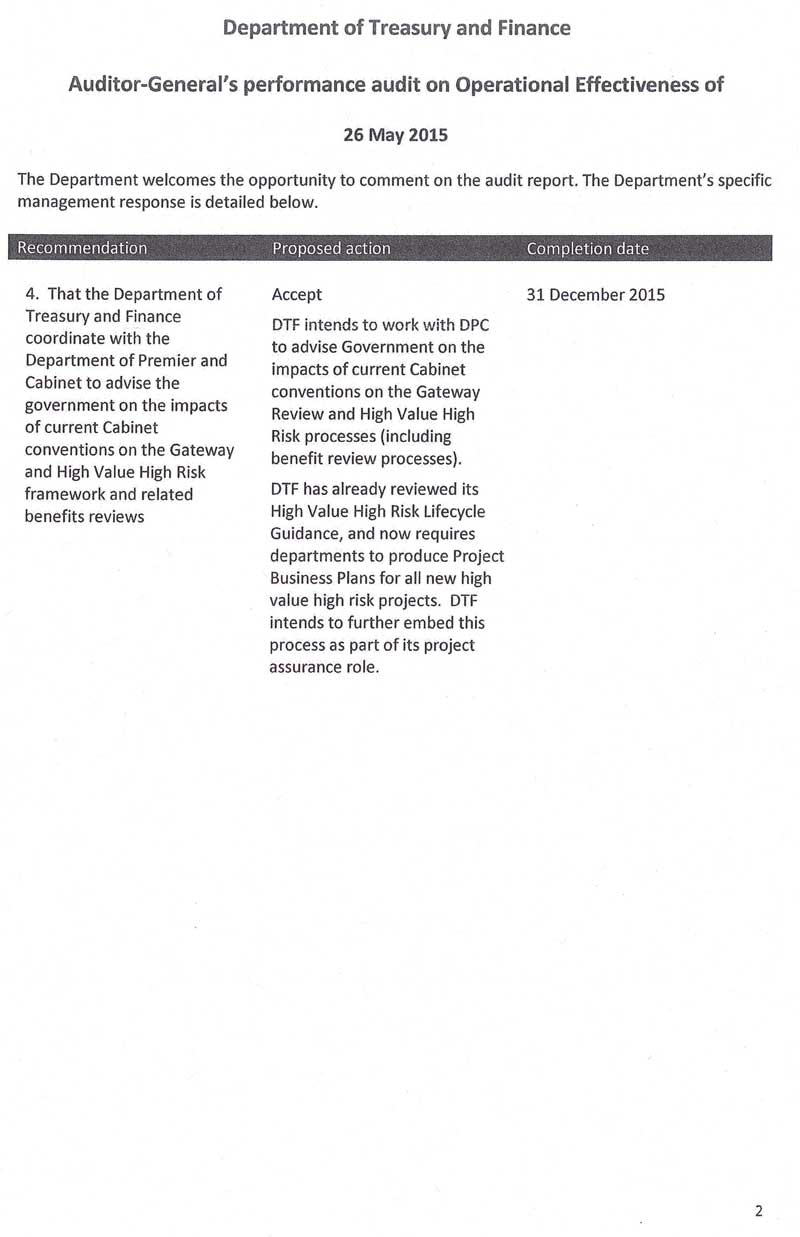

That the Department of Treasury and Finance coordinate with the Department of Premier and Cabinet to:

- advise the government on the impacts of current Cabinet conventions on the Gateway Review and High Value High Risk framework and related benefits reviews.

That Public Transport Victoria:

- clarifies the retender benefits and intended outcomes and develops measurable associated indicators.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with Public Transport Victoria, the Department of Treasury and Finance, and the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Public transport ticketing systems

Modern public transport ticketing systems are much more than simply fare collection tools. They provide the key interface with customers and, with smartcard technology, can assist strategic planning for the public transport system, through the collection of valuable usage data. A well designed and implemented system should be easy for commuters to use, and benefit transport operators by streamlining fare collection and providing access to important data on travel behaviour.

Smartcard systems are the new standard in transport ticketing internationally due to their convenience and efficiency. Tickets can be purchased and 'topped up' using automated processes, they allow rapid movement through stations and easy interchange between different travel modes.

However, international experience has also shown that developing reliable and effective public transport ticketing systems is both difficult and expensive.

1.2 Overview of myki

In Victoria, public transport ticketing depends on which service a passenger uses:

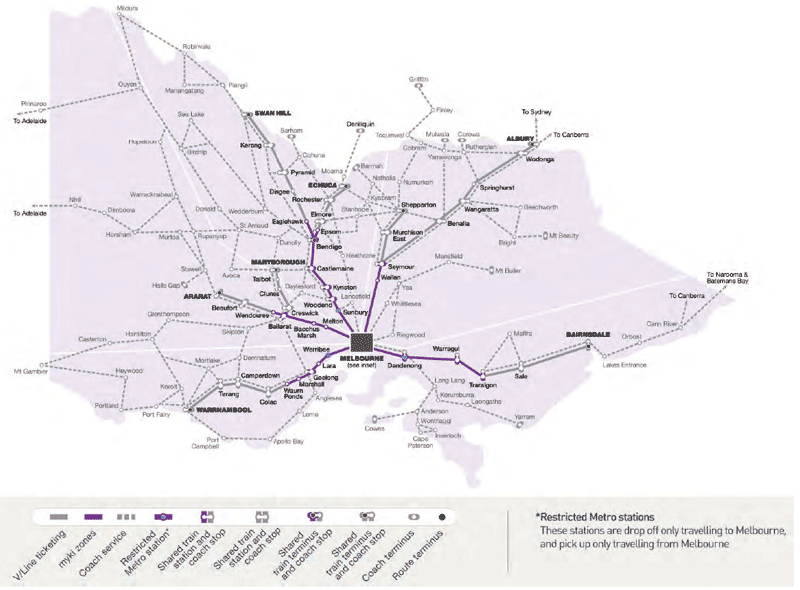

- myki for metropolitan trains, trams and buses, V/Line commuter trains and some regional town buses—Appendix A in this report contains a map showing the regional train and coach network and a list of regional town bus networks included in the myki ticketing system

- paper tickets for V/Line coach and long distance train services

- paper tickets for some regional town buses.

myki smartcard

In July 2005, the state entered into a contract to develop a smartcard public transport ticketing system, known as myki, to replace the former Metcard system, which expired in 2007.

Under the terms of the original contract, myki was to be fully operational by July 2007. The initial whole-of-project budget was $998.9 million and included $177.1 million for delivering myki and $345.5 million for operating it for 10 years. The remaining budget included funds for operating the Metcard system in parallel with myki during the transition, and related operating costs for the former Transport Ticketing Authority (TTA). TTA was established in 2003 to manage Metcard, and the procurement and rollout of the new ticketing system, now known as myki. TTA was abolished in 2013 following the establishment of Public Transport Victoria (PTV) which has since assumed responsibility for all of TTA's functions.

The myki system includes the following components:

- myki smartcard—used to pay for travel on public transport. The myki smartcard technology enables a money value—myki money—and/or a travel pass—myki pass—to be stored on the card. Public transport users that 'top up' with myki money need to touch on and off for each trip so that the myki system can automatically calculate and deduct the lowest fare for the travel taken.

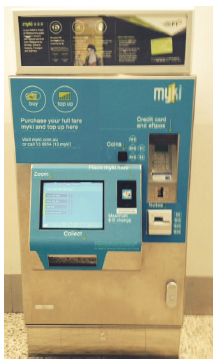

- Devices—the system currently has around 23 500 operational devices. These include card vending and top-up machines, fare payment devices, bus and tram driver consoles, station gates and hand-held devices. These devices read and translate information stored on smartcards and transmit information to and from the back office.

- The back office and related systems—these support the operation of the myki system.

Card vending and top-up machine

It was expected that myki would deliver a range of benefits for users, transport operators and the state including:

- ease of use

- convenient purchase and payment options

- efficient operations in terms of boarding

- high-quality information for transport planning

- increased flexibility to change and drive user patterns through differential pricing and fare structures.

myki is an open-architecture system, meaning it allows the flexibility of adding, upgrading and swapping components over time without limiting the state to using a single vendor.

1.2.1 Implementation of myki system

Despite their clear benefits for commuters and transport system operators, smartcard ticketing systems are challenging to design and implement due to:

- the complexity involved in designing and delivering a solution that meets the needs of a unique transport system, such as Victoria's, with multiple modes and zones of travel

- the need to properly inform and assist commuters as they adapt to the new system.

There are few examples of the ambitious approach taken in Victoria, which sought to introduce a statewide smartcard ticketing system across all public transport modes and zones. The Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) 2011 Project review of the myki ticketing system noted that most smartcard ticketing systems were initially introduced in the metropolitan area only—as in Perth, London, Hong Kong and Singapore—or a metropolitan area plus adjacent region—as in South East Queensland. There are considerable challenges in bringing together a range of different fares across metropolitan, regional and rural areas, different public transport operators, and various types of customers.

Figure 1A compares myki to other smartcard systems operating in Perth, South East Queensland, and London by initial scope and key functions. It shows that myki is the only smartcard ticketing system that was initially integrated across metropolitan and regional areas, and possessed a wider range of functions than the ticketing systems in other jurisdictions.

Figure 1A

Ticketing system comparisons

|

Victoria's myki |

South East Queensland's go card |

Perth's SmartRider |

London's Oyster card |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Scope |

||||

|

Devices |

20 000 |

8 000 |

4 000 |

25 000 |

|

Metropolitan transport modes |

|

|

|

|

|

Regional transport modes |

|

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

Key functions |

||||

|

Time-based |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Zone-based |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Auto top up |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Online top up |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Pass and money |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on the Project Review of the myki ticketing system, February 2011, Department of Treasury and Finance.

The myki system covers:

- 15 train lines with 208 stations in metropolitan Melbourne

- 24 tram routes with 500 trams in metropolitan Melbourne

- 346 bus routes with 1 753 buses in metropolitan Melbourne

- 5 regional train lines with 51 stations

- 127 regional bus routes.

The myki system also offers a complex range of ticketing fares, with both zoned and time‑based charging and a variety of concessions and discounts. The system executes 150 business rules each time a card is scanned, which constitutes around 1.07 million fare transaction‑type permutations, making it one of the most complex smartcard ticketing solutions in the world.

As at December 2014, more than 13.4 million myki cards had been issued with the system processing around 7.8 million 'touch on' transactions per week from 9.9 million active cards. In 2013–14 the total farebox collected by myki across all transport modes was around $800 million.

1.2.2 Implementation of myki

Time line in implementing myki

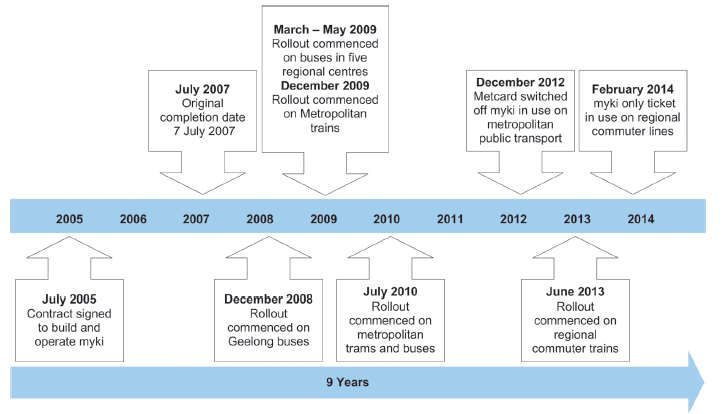

The myki system was due to be operational by July 2007. However, there have been multiple delays, scope changes and cost increases. Figure 1B illustrates these delays.

Figure 1B

Delays in implementing myki

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Initially myki was implemented on regional buses in Geelong in December 2008. The system was extended to bus services in five other regional centres from March 2009. It began running on metropolitan trains in December 2009, and was extended to metropolitan trams and buses in July 2010. In December 2012, myki became the only form of ticket valid on Melbourne public transport and the previous ticketing system, Metcard, was switched off. In February 2014, myki replaced paper tickets on V/Line services across selected services in Victoria.

The total time of the design and delivery phase has more than quadrupled from the original expectation of two years, to in excess of nine years. This is more consistent with smartcard projects in other cities, where it usually takes five or more years.

Figure 1C illustrates the time taken to implement public transport ticketing systems in other jurisdictions.

Figure 1C

Delivery time frames for public transport ticketing systems

|

Region |

Card name |

Delivery time frame |

|---|---|---|

|

Hong Kong |

Octopus |

3 years |

|

Perth |

SmartRider |

4 years |

|

South East Queensland |

go card |

5 years |

|

Los Angeles |

TAP |

5-plus years |

|

Houston |

Q-Card |

5-plus years |

|

Minneapolis |

Go-to-card |

5-plus years |

|

Ireland |

ITS |

5-plus years |

|

London |

Oyster |

6 years |

|

Holland |

OV-Chipkaart |

7-plus years |

|

Victoria |

myki |

9 years |

|

Paris |

Navigo |

10-plus years |

|

San Francisco |

Translink/Clipper |

12-plus years |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on the Victorian Government submission to the Legislative Council Select Committee on Train Services, former Department of Transport.

Cost

At 30 June 2014, the revised capital and operating budget for myki until 2016 was $1 550.5 million, an increase of 55 per cent on the initial budget of $998.9 million.

Significant additional costs of approximately $200.1 million, over the budgeted amount of $106.8 million, were incurred for operating the Metcard system in parallel with myki beyond its contracted termination date in 2007.

Issues with implementing myki

There were a number of implementation issues with myki—including slow card reader response times, intermittent technical failures particularly on trams and buses, and concerns with the accuracy of data for measuring patronage.

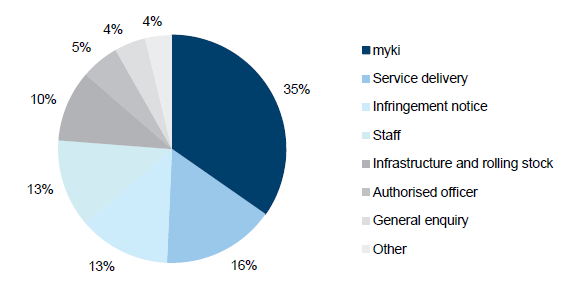

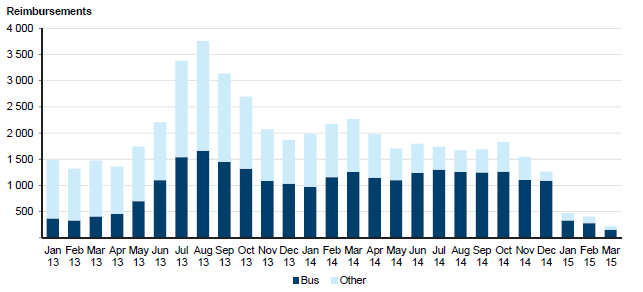

The Public Transport Ombudsman received over 5 450 complaints about myki between July 2010 and June 2014. Most of the issues raised were associated with account charges and refunds and reimbursements.

Data maintained by PTV shows that during the same period it received in excess of 200 000 complaints and enquiries relating to myki.

Our 2012 audit, Fare Evasion on Public Transport, also noted a significant increase in metropolitan fare evasion between 2009 and 2011 due to the decline in effective enforcement during the transition to myki. However, the estimated fare evasion on Melbourne's public transport network has since dropped to its lowest level since 2008.

Given the significant delay, additional costs and challenges in delivering myki, the former government commissioned a review of the system in late 2010 to determine its future. Following this review it decided to proceed with implementing myki but with a reduced scope. The contract with the myki operator was subsequently amended in November 2011 and March 2013 to reflect the revised approach.

The current myki contract service term is due to expire on 30 June 2016. PTV is currently planning to retender the operation of the myki system.

1.3 Reviews of public transport ticketing

Previous performance audits

Our 1990 audit Met Ticket, and 1998 audit Automating Fare Collection: A major initiative in public transport, examined the state's previous public transport ticketing solutions.

Both of these audits found that fast tracking the development of these ticketing systems led to successive delays and cost blowouts in implementation, which exposed the state to major risks of not achieving system objectives.

Specifically, our 1990 audit Met Ticket found that a compressed time frame for implementing Met Ticket meant that certain desirable project management principles were bypassed. Specifically, multiple variations to the initial proposal occurred during the rollout, which complicated implementation and resulted in delays. The audit also found that, consequently, substantial effort and cost was incurred with only minimal benefit to public transport users and the government.

Despite the lessons from the Met Ticket experience noted in our 1990 report, in 1998 we identified similar weaknesses with the implementation of Met Ticket's successor, Metcard. In particular this audit found that the decision to fast track Metcard's implementation resulted in a failure to properly analyse the system's costs and benefits, and set unrealistic milestones, leading to delays.

Our 2007 audit New Ticketing System Tender examined the tender process for myki, including the lessons arising for the future management of major tenders. The report concluded that TTA established an 'innovative tender process and largely achieved its objectives for the procurement phase' of the project. It also identified some areas where probity management could be improved, in particular, ensuring that the probity protocols work to minimise the risk of actual or perceived conflicts of interest.

Other reviews of myki

State agencies, Parliament and the Victorian Ombudsman have also previously reviewed the status and implementation of myki. Key reviews include:

- Project review of the myki ticketing system, DTF, February 2011

- Own motion investigation into ICT-enabled projects, Ombudsman Victoria, November 2011, conducted in conjunction with VAGO

- Inquiry into Effective Decision Making for the Successful Delivery Of Significant Infrastructure Projects, Public Accounts and Estimates Committee, December 2012

- Lessons learned review of the myki ticketing system, DTF, April 2014

These reviews have all identified significant issues with the governance and contractual arrangements that were established:

- The roles and responsibilities of key governance bodies were not clearly defined. Consequently, this made it difficult to determine which agencies were responsible for different aspects of the project and this resulted in ineffective communication between key parties.

- The original contract was large, complex and outcomes-based. This meant that the functional performance requirements of the system were not clearly defined. This ultimately led to confusion over the responsibilities of the contractor, incurring delays and budget increases.

1.4 Institutional arrangements and responsibilities

Transport Ticketing Authority

The TTA was established in June 2003 to manage the Metcard ticketing system and to procure and manage a new replacement ticketing system, now known as myki. The TTA completed its role in the delivery of myki and the management of the Metcard system in December 2012, with PTV assuming responsibility for all TTA functions from January 2013.

Public Transport Victoria

PTV's primary objective under the Transport Integration Act 2010 is to plan, coordinate, provide, operate and maintain a safe, punctual, reliable and clean public transport system consistent with the vision statement and transport system objectives contained in the Act. This includes providing and operating a public transport ticketing system, managing the public transport ticketing system contract, and the collection and distribution of farebox revenue.

Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (DEDJTR) is responsible for leading strategic policy, planning and improvements relating to the transport network.

DEDJTR is currently a member of the myki Ticketing Advisory Group—which advises the PTV board on myki matters—and the myki Ticketing Services Retender steering committee—which provides advice and guidance relating to the retender of myki.

Department of Treasury and Finance

DTF's role and involvement in the project has varied over its life cycle. This has included observer membership of the former TTA board, current membership of the Ticketing Advisory Group, participation in the Ticketing Services project steering committee and reviewing associated progress reports. From 2010 DTF expanded its monitoring and review function as the project is now monitored under the High Value High Risk framework. DTF also led negotiations with the vendor following the review of the project, which was initiated by the former government and completed in 2011.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to examine the operational effectiveness of the myki ticketing system by assessing whether:

- arrangements in place for the system's implementation and ongoing management are effective

- expected outcomes and benefits from the introduction of myki for users, operators and the state have been, or are on track to being, achieved.

The audit focused on how well PTV is managing and operating the myki ticketing system. Specifically, it examined whether governance and contractual arrangements including frameworks for monitoring and evaluation, assure myki's operational effectiveness. It also included DEDJTR due to its role in working with PTV on future contract planning, and DTF due to its role in overseeing and monitoring the project.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $415 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

The report has three further parts:

- Part 2 examines whether governance and contractual arrangements support effective implementation and operation of myki.

- Part 3 examines:

- the performance of the myki system and adequacy of arrangements for monitoring the contractor's performance

- whether expected outcomes and benefits from the introduction of myki for users, operators and the state have been, or are on track to being, achieved.

- Part 4 examines whether planning for the retender for managing myki's ongoing operation is soundly based and designed to deliver a value-for-money outcome.

- Appendix A shows the extent of myki use on the regional train, coach and town bus network.

2 Governance and contractual arrangements

At a glance

Background

The myki project has been complex and large-scale from its conception and through its development and procurement. For such projects sound governance and contract management arrangements are essential for assuring key risks to delivery are effectively managed, and that intended benefits are achieved.

Conclusion

The myki system experienced significant delays and cost increases largely due to deficiencies in the original governance, project planning and contractual arrangements. Subsequent changes to the contract, including strengthened governance arrangements, have largely addressed these deficiencies.

Findings

- The original myki governance structure was poorly defined and implemented—hampering the project's management.

- Revised governance arrangements established following Public Transport Victoria's creation in 2012 have substantially addressed the previous deficiencies.

- Implementation difficulties arose from critical deficiencies in the design of myki's initial contract that compromised it's viability, including:

- poorly defined functional performance requirements

- a lack of flexibility to address contractor underperformance

- unrealistic delivery time frames.

- Amendments to the contract since myki's initial development and rollout have addressed unrealistic delivery time lines, and have improved the contract's financial viability.

2.1 Introduction

The myki project has been complex and large-scale from its conception and through its development and procurement. Sound governance and oversight of such projects is essential for assuring risks to delivery are effectively managed, and that intended benefits are achieved.

This requires effective mechanisms for project monitoring and risk management to support timely decision-making in response to emerging issues.

It also requires clearly defined deliverables and responsibilities, and effective contract management to ensure responsible parties meet their respective obligations and achieve the contract's objectives.

This Part of the report examines whether myki's governance and contractual arrangements support its effective implementation and operation.

2.2 Conclusion

The myki system has experienced significant delays and cost increases. This is largely due to deficiencies in the original contract and governance arrangements.

The roles and responsibilities of key agencies initially charged with myki's development were neither well defined nor effectively implemented. This led to uncertainty and delays in decision-making—particularly during myki's initial build and rollout.

The ambitious initial scale and poorly defined functional performance requirements for myki also contributed to significant delays in its implementation. Collectively, these challenges compromised the viability of myki's initial scope and contract, and precipitated six major contractual amendments as the project encountered significant difficulties.

While these amendments strengthened the contract, they also substantially reduced myki's scope and extended its delivery time frames by seven years. This compromised achievement of the project's original objectives and expected benefits.

Since it was established in April 2012, Public Transport Victoria (PTV) has improved governance and contractual arrangements to support the oversight and operation of myki.

2.3 Governance arrangements supporting the delivery and operation of myki

The governance arrangements for the myki project have been scrutinised by several reviews over the past four years. These reviews consistently identified significant weaknesses that needed to be addressed.

Department of Treasury and Finance's 2011 Project review of the myki ticketing system

This review examined the initial myki contract and rollout, including the government's options for proceeding with or discontinuing myki.

The review found that myki's original communication, decision-making and accountability arrangements were 'troublesome'. In particular, it noted there was a lack of clarity regarding whether the former Department of Transport (DOT) or the Transport Ticketing Authority (TTA) was the ultimate decision-maker on issues, and that poor engagement between the myki contractor and public transport operators contributed to a difficult working relationship that negatively impacted the project.

The review also found that:

- the TTA board and public transport operators were excluded from the governance arrangements

- TTA did not have clear accountability and authority to directly manage the contractor

- the role and authority of all project-related groups was unclear and lacked integration.

The review noted that these arrangements needed to be clarified and strengthened if the state decided to proceed with the project.

Victorian Ombudsman 2011 Own motion investigation into ICT‑enabled projects

This investigation examined 10 major ICT-enabled projects, including myki, to determine whether they were on budget and on time, and if they met the needs for which they were designed.

The Ombudsman was critical of the fact that TTA's board initially did not include a representative from DOT, given that DOT had policy responsibility for ticketing issues and TTA was reliant on it for promptly addressing its requests. The Ombudsman also questioned if the board had the requisite experience and skills to implement an ICT project of the size and complexity of myki.

Similarly, our 2007 audit New Ticketing System Tender found that, for most of the tender period, the board consisted of only two members and that a larger board was warranted given the size and complexity of the tender.

Public Accounts and Estimates Committee's 2012 Inquiry into Effective Decision Making for the Successful Delivery Of Significant Infrastructure Projects

The Public Accounts and Estimates Committee's (PAEC) 2012 inquiry into the decision-making underpinning successful infrastructure projects examined six projects, including myki, to identify lessons learned.

The inquiry found myki lacked continuity in project management and governance, and that TTA did not possess the capability and capacity needed to effectively manage the project. It also noted that significant changes to key personnel exposed the project to greater risks than if there had been a consistent, high-quality team running it.

Department of Treasury and Finance 2014 Lessons learned review of the myki ticketing system

This review examined critical issues affecting myki's delivery within the originally approved time frame and budget.

The review found that the original governance structure made it very difficult to identify which agency had overall accountability for the project and what aspects of the project each agency was responsible for. Consistent with the Ombudsman's 2011 investigation, the review noted that the relationship between TTA and the former DOT was not clearly defined. Specifically, while DOT had policy responsibility for ticketing issues, it did not have a representative on the TTA board and therefore no visibility of policy implementation.

The review further noted that ineffective communication between the two agencies compounded the structural deficiencies—with TTA having to wait for DOT to respond to policy enquiries that may have had time-critical implications. Because of this reliance on DOT to clarify policy issues, TTA did not have complete control over meeting prescribed project deadlines. DTF therefore concluded that the design and operation of the governance arrangements was ineffective. DTF also noted that, had there been a closer working relationship between DOT and TTA, or if DOT had membership on the board, TTA's functioning with regard to policy issues may have been greatly improved.

Revised governance arrangements

The governance arrangements for the myki project were revised following PTV's establishment in 2012. The new arrangements have substantially addressed the previous deficiencies. In particular, PTV has now assumed the functions of managing the public transport system and myki, which were formerly separate functions under DOT and TTA respectively.

This fundamental change has, in effect, resolved the previous disconnect in responsibilities for public transport ticketing policy development and implementation that hampered TTA's management of myki. It has also clarified PTV's role, decision‑making authority and accountability for managing the myki contractor.

PTV's updated governance structure for myki includes arrangements designed to strengthen:

- cross-agency coordination

- engagement between PTV, the myki contractor and public transport operators

- PTV's expertise and capability for managing the contract.

Figure 2A outlines the revised governance arrangements.

Figure 2A

Current governance arrangements

Name |

Description |

|---|---|

Ticketing Advisory Group Established January 2013 |

Membership—chaired by PTV and made up of senior management staff from PTV, the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport and Resources (DEDJTR), DTF and the Department of Premier and Cabinet. Purpose—to advise the PTV board on the operations of the myki ticketing system with a focus on service to customers and to the operators. |

Operational Control Group Established March 2013 |

Membership—jointly chaired by PTV and the myki contractor and made up of three senior members from PTV and three from the contractor. Purpose—reports to the Ticketing Advisory Group and is responsible for overseeing and/or approving business planning, cost saving initiatives, major budget or cost variations, performance of the system, and the forward capital works program. |

Change Advisory Board Established March 2013 |

Membership—comprises senior PTV managers and subject matter experts who are invited to attend, if necessary, in an advisory capacity to provide technical input. Purpose—to review, assess and approve contract variation requests related to the myki contact. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In addition to these arrangements, Figure 2B outlines other initiatives recently introduced by PTV to improve its engagement with public transport operators and the myki contractor.

Figure 2B

Operator engagement initiatives

Initiative |

Description |

|---|---|

Fortnightly Ticketing Services meetings Established 2013 |

Membership—comprised of PTV staff, the myki contractor and public transport operators. Purpose—a forum to raise, discuss and resolve issues with myki. |

Metropolitan and Regional Bus Ticketing Services Group Established August 2014 |

Membership—chaired by PTV and comprised of metropolitan and regional bus operators and PTV representatives. Purpose—to meet and discuss operational matters relating to myki, including identifying systemic and emerging myki device issues. |

Network Development Partnerships Established 2012 |

Membership—PTV and public transport operators. Purpose—its main purpose is to discuss public transport performance issues, progress and emerging issues. However, issues with myki are also raised on occasions. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4 Contractual arrangements for myki

Previous reviews of myki have also found significant problems with the original contractual arrangements. These problems impacted the build, initial implementation and operation of myki and were linked to:

- poorly defined functional performance requirements

- a lack of flexibility in the initial contract to address underperformance

- unrealistic time frames

- poor financial viability of the initial contract.

Poorly defined functional performance requirements

The Ombudsman's 2011 investigation noted that the original myki contract was large and complex with over 13 000 pages and 40 schedules. It also found that the contract was difficult to manage as it was outcomes rather than requirements based, meaning it was unclear whether certain functional requirements were within or outside the scope of the contract. This led to disputes with the contractor about costs and priorities.

DTF's 2014 review similarly found that the contract lacked sufficient specificity as the required functional performance of the system was not clearly defined.

Additionally, PAEC's 2012 inquiry noted that the state and contractor would have been better served 'if more time had been invested in the beginning' to explore and get a common understanding of the requirements.

Lack of flexibility to address contractor underperformance

DTF's 2014 review found that the structure of the contract covering the project's build and operations phase did not provide the flexibility to suspend or exit the contract to address underperformance. This complicated the system's rollout, including the state's relationship with the contractor, as the operations phase was allowed to commence before the build was complete and related issues were resolved.

In particular, this meant that outstanding build issues had to be managed by the contractor in parallel with the commencement of operations which compromised the contractor's capacity to meet prescribed milestones and, ultimately, the project's delivery.

Unrealistic time frames

Early decisions in the planning phase of the myki project caused subsequent challenges that necessitated contractual amendments. In particular, the expiration of the former Metcard contract in 2007 was the catalyst for introducing myki and seeking to implement it within the ambitious time frame of two years.

This time line, stipulated in the initial contract, proved to be unrealistic and affected the contractor's ability to meet milestones and receive milestone delivery payments. Since myki commenced operating in 2009, contract payments of $27 million were withheld from the contractor for its failure to achieve milestones.

TTA advised the 2012 PAEC inquiry that the time frame had 'been the biggest single cause of project difficulties' with the contractor consistently failing to meet milestones during the initial build phase of the project. The contract was subsequently amended, which reset the project's milestones.

The complexity of the project was significantly underestimated and DTF's 2014 review noted that, 'no other jurisdiction in the world had developed and delivered a ticketing procurement strategy that included an outcomes-based specification through an open architecture approach in the two year time frame committed. The initial project planning did not take into account international experience on the implementation of new ticketing systems'. According to the review, if the contract had been appropriately benchmarked against projects around the world, which were similar in complexity, size, budget and time, the majority of changes subsequently incorporated in the contract may not have been necessary.

Financial viability of the contract

The 2011 DTF review noted that neither the contractor nor TTA felt the operating phase of the contract was commercially viable. Scope extensions in multiple areas including cash collection, card distribution and system maintenance had increased costs beyond what could be borne by the contractor. The contractor also highlighted that there were cost implications stemming from commencing operations in parallel with the delivery phase in 2009, rather than at the end of delivery.

A further issue affecting the commercial viability of the contract was its failure to accommodate the increased operating costs for the system arising from the 30 per cent growth in public transport patronage that occurred during its implementation. Contractual amendments had addressed the increased capital costs associated with patronage growth, but not the operations and maintenance costs.

Key themes

These issues with the myki project identified by the Ombudsman and PAEC are consistent with the key themes emerging from their related examination of other major ICT projects. These themes highlight that:

- poorly defined governance structures with unclear roles and responsibilities have hampered project management

- inadequate planning has led to significant delays, cost increases and failures to achieve original objectives

- overly-ambitious and poorly-scoped projects have unnecessarily heightened project complexity and risk

- inadequate ICT capability within agencies has contributed to poor project management.

2.4.1 Contractual amendments

Since the initial contract was awarded, there have been numerous variations and six major contractual amendments directed at addressing these issues. Figure 2C summarises the contractual amendments agreed between the parties.

Figure 2C

Summary of major amendments to the myki contract

Title and date of amendment |

Major amendments incorporated in the contract |

|---|---|

Delivery phase |

|

Amending Deed 1 (December 2006) |

Finalised various matters not concluded at contractual close, including the definition of card ordering processes, the key performance indicator regime and phase completion conditions. |

Amending Deed 2 (January 2008) |

Gave TTA new rights in the event that the contractor did not complete the Regional Bus Pilot Trial by the set date. This included the repayment of $20 million and the ability to terminate the contract if this was not achieved. |

Amending Deed 3 (June 2008) |

Settled previously disputed scope claims to enable full delivery of myki. Reset the project time lines and payment schedule, and increased liquidated damages in the event the new time line was not met. |

Amending Deed 4 (June 2009) |

Changed the process of ordering and payment for smart cards. TTA agreed to pay for smartcards as soon as they received them. Prior to this amendment, TTA would pay for smartcards when they were sold to customers. |

Amending Deed 5 (November 2011) |

Resolved outstanding scope issues relating to the build phase, reset the project schedule to 2019 including related milestones and payments. Scope changes as part of this amendment as recommended by DTF's review included:

|

Operating phase |

|

Amending Deed 6 (March 2013) |

Set the parameters for the operation of myki including:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from Public Transport Victoria.

The extent of changes to the contract indicates that the initial planning underestimated the complexity of implementing a new ticketing system. It also suggests that more time should have been spent developing the contract to more clearly define requirements and critical milestones.

Impact of key amendments

The most significant contractual changes were Amending Deeds 5 and 6, which addressed the unrealistic time lines and financial viability of the contract.

Amending Deed 5 ensured the deliverability of myki by reducing its scope to enable it to be rolled out by the revised due date of December 2012 when Metcard was to be switched off.

Amending Deed 6 was implemented to address the risk that the contractor may minimise or discontinue support for the system because the project was financially unviable. This amendment fundamentally changed the contract and how the state would pay for myki. The key changes included:

- the adoption of a 'cost plus' reimbursement model, rather than a fixed price arrangement—this meant the total cost of the system under the contract is no longer capped and ensured it was financially viable for the contractor

- a redefined scope of services, with some services no longer performed by the contractor—including call centre operations

- changed key performance indicators, encompassing financial incentives and abatements.

The introduction of the 'cost plus' reimbursement model and financial incentives for sustained good performance has improved the commercial viability of the contract. However, shortcomings with PTV's approach to verifying the contractor's performance data are compromising its capacity to assure the integrity of performance-based payments. This is further discussed in Part 3 of the report.

3 Performance monitoring and benefits realisation

At a glance

Background

Public Transport Victoria (PTV) needs an effective performance measurement and reporting framework in order to ensure that myki operates effectively, and delivers the intended benefits.

Conclusion

PTV has enhanced the quality of performance measures and incentives in the myki contract. However, the effectiveness and integrity of the new performance regime is compromised by critical shortcomings in PTV's approach to verifying the accuracy of related results reported by the contractor.

Findings

- The performance measures in the initial myki contract were difficult to interpret and apply, and impeded effective contract management.

- Although newly developed measures have improved in clarity and focus, fundamental issues remain. Specifically:

- current metrics in the contract's new performance regime do not address key aspects of operational performance

- there is no framework for assessing myki's overall effectiveness, efficiency and benefits.

- Performance data indicates that the contractor has met most performance targets, however, PTV cannot assure the accuracy of this information.

- Current Cabinet conventions preclude access to the original myki business case, which is needed to facilitate a post-implementation and benefits review.

Recommendations

- That PTV reviews and strengthens its performance monitoring framework for myki prior to awarding the new contract.

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance coordinate with the Department of Premier and Cabinet to advise the government on the impacts of current Cabinet conventions on the Gateway Review and High Value High Risk framework and related benefits reviews.

3.1 Introduction

Public Transport Victoria (PTV) needs an effective performance measurement and reporting framework in order to ensure that the system operates effectively, and delivers the intended benefits.

Such a framework depends on the availability of sufficient, appropriate and reliable performance data and on PTV regularly monitoring critical aspects of performance. This includes monitoring whether services are being delivered in accordance with the contractual standards so that timely action can be taken to address emerging issues.

This Part of the report examines:

- the operational performance of myki and adequacy of arrangements for monitoring the contractor's performance

- whether expected outcomes and benefits from the introduction of myki for users, operators and the state have been, or are on track to be, achieved.

3.2 Conclusion

PTV has enhanced the quality of the performance measures and incentives in the myki contract, and their potential to drive improved performance.

However, the effectiveness and integrity of the new performance regime is currently compromised by critical shortcomings in PTV's approach to verifying the accuracy of related results reported by the contractor.

PTV needs to urgently address these issues as they reduce assurance that current incentive payments are appropriate and justified.

Further, the absence of arrangements for monitoring myki's overall effectiveness, efficiency and achievement of benefits, means there is currently no evidence to demonstrate its impact on the performance and management of the public transport system. However, the significant delays, budget increases and substantial reductions in myki's scope over time strongly indicate that it has failed to fully meet its original objectives.

3.3 Measuring myki's performance

3.3.1 Issues with previous monitoring arrangements

The performance regime in the initial myki contract was complex, onerous and, with 81 measures, difficult to apply in practice. Further, the performance measures only applied once myki was fully operational. The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) had raised concerns with the performance regime in a number of ministerial briefings. For example, a 2012 DTF briefing to the Treasurer noted that the performance measures in the contract were 'difficult to interpret and apply' and that a new regime was needed to drive 'appropriate behaviours' from the contractor. A subsequent 2013 DTF briefing to the Treasurer similarly noted that 'more measurable and enforceable key performance indicator targets' were needed.

A contractual amendment introduced in March 2013—Amending Deed 6—sought to address these shortcomings by establishing a new performance regime. Key changes to the contract included:

- deleting obsolete measures relating to services that were removed from the contract—this substantially reduced the measures from 81 to 27

- establishing an incentive and abatement regime to drive improvements in customer service and system reliability, by linking the contractor's performance against defined standards to financial incentives and penalties.

3.3.2 New performance measures

The new performance regime includes 27 measures aligned with seven service categories specified in the contract:

- distribution services—the supply, distribution and stock management of smartcards

- cash collection—the collection of cash from card vending machines and ticket offices and the replenishment of cash, smartcards and consumables

- scheme administration—the administration and maintenance of data and products

- device management—the implementation, updating, operation and maintenance of devices

- financial management—the time lines of financial settlement, reconciliation and investigation of associated discrepancies

- technical support—the management of the operational, functional and performance aspects of the back office systems, and system connectivity with devices

- operational support—response to queries from transport operators, myki retailers and PTV.

The new regime has improved the clarity and focus of performance measures in the contract, and its potential to drive improved performance. In particular, the new regime has heightened the focus on service aspects that previously emerged as critical performance issues. Specifically, new measures have introduced incentives for the contractor to promptly address faults with myki devices and related software upgrades, which previously disrupted system operations. The new regime has also increased the contractor's focus on assuring the accuracy of the financial information recorded by the system.

3.3.3 Limitations of the current performance regime

Limited focus on equipment availability

While the contract amendments improved the performance measures in the original contract, fundamental issues remain.

Specifically, the performance regime is focused on availability rather than performance. That is, it does not adequately measure how well the equipment operates as distinct from the length of time for which it is functioning and available. For example, the speed of transaction processing—the response times of myki fare readers, including entry/exit gates—is not measured.

This is a critical omission given that a key intended benefit of myki is fast and convenient ticketing for the travelling public. PTV's testing of transaction speed at entry and exit points on all device types during the implementation of myki reinforces the importance of such measures, as it showed that this ranged from 1.8 to 4.2 seconds against a design target of 1.2 seconds.

Current measures also fail to distinguish performance problems with equipment at busy train stations during peak periods, an obviously critical performance issue, from similar issues with equipment at infrequently used stations during off peak periods.

Lack of system-wide and benefits monitoring

There is no overarching framework for monitoring the effectiveness and efficiency of the myki ticketing system.

The new performance regime is limited to monitoring the contractor's performance and does not enable assessment of the extent to which myki's broader intended benefits and value for money have been achieved.

This issue is discussed further in Section 3.7.

3.3.4 Limitations of other monitoring activities

PTV produces a number of monitoring reports that supplement the performance information about myki it derives from the contract's performance regime. While these reports provide useful insights, they do not provide a complete view of myki's performance, nor are they sufficient to verify all the performance information submitted by the myki contractor.

Specifically, these reports include:

- operational performance monitoring reports which focus on myki device availability, transaction capture by the system, the condition of selected devices and the status of maintenance works

- device management dashboard reports which focus on the status of maintenance works for all myki devices

- operator dashboard reports for trains and trams which similarly focus on maintenance issues as well as tracking the number of card sales and 'touch-ons'

- metro trains device downtime reports, which focus exclusively on the myki system's 'availability' across the train network.

A key limitation of the above reports is that, like the contract's performance regime, they mainly focus on the 'availability' and condition of myki devices, rather than on how well the system performs.

While PTV's operational performance monitoring reports examine aspects of myki's performance, this is limited to assessing a sample of bus, tram and train card vending machines and if they are functioning, and the responsiveness of selected myki card readers on a sample of trams and buses.

Other limitations of the operational performance monitoring reports include:

- they make no reference to the standard used for assessing the responsiveness of devices and only describe changes in performance relative to previous reports, meaning the basis of the assessment is unclear

- they do not assess the performance of myki entry/exit gates and card readers across the train network, despite initial PTV testing during the rollout showing the system performed worse than the contractual standard

- the reports do not provide up-to-date intelligence on how the system is currently performing

- the reports do not cover the range of measures reported on by the contractor for determining incentive payments and abatements, meaning they cannot be reliably used to verify all monthly results reported to PTV by the contractor.

PTV also advised that it maintains a register of incidents, such as equipment faults, that have impacted the myki system which it considers when assessing the contractor's performance in relation to the incentive and abatement scheme. However, the information in this register is limited as it depends on the vigilance of staff and customers to report such incidents to PTV. Unless PTV is informed, it is unlikely to be aware of and record the incident. Consequently, there is a risk that the real level of equipment faults may be understated.

3.3.5 Incentives and abatement regime

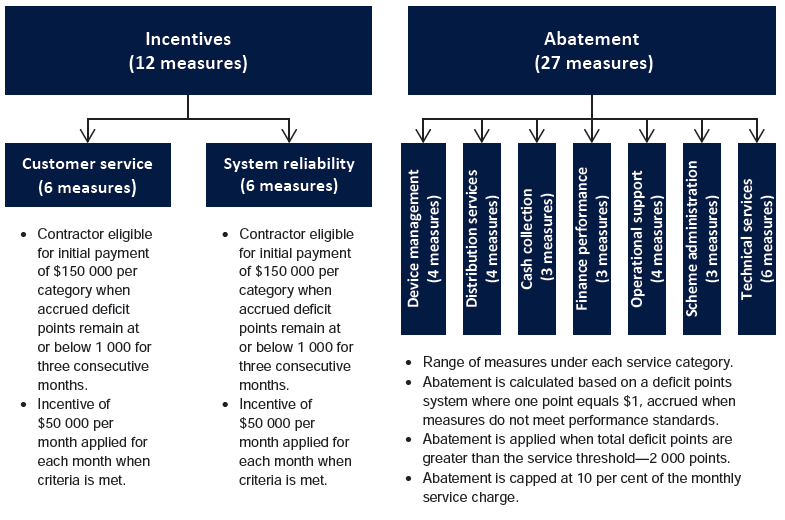

The new performance regime now incorporates performance-based payments linked to 12 of the 27 performance measures. The contractor has the opportunity to receive incentive payments for sustained positive performance against these measures. The incentive scheme is separated into two categories—customer service and system reliability. Incentive payments are calculated separately for each category.

The performance regime also provides for abating the contractor's monthly service charge for sustained poor performance across 27 measures. Figure 3A provides an overview of the incentive and abatement regime.

Figure 3A

Overview of the incentive and abatement regime

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from Public Transport Victoria.

A deficit point system is used to determine whether the contractor is eligible to receive an incentive payment or if the contractor's monthly service charge should be abated. Deficit points are accrued when the contractor does not meet a measure's target. Each measure has a different method for calculating how deficit points are accrued.

Under the regime, the contractor is eligible for an initial incentive payment of $150 000 per category when the total number of accrued deficit points for the category remain at, or below, 1 000 for three consecutive months. For each subsequent month that deficit points remains below the threshold, a further incentive payment of $50 000 per category is awarded. If the number of deficit points exceeds the threshold in a particular month, no incentive is awarded for the category, and the three-month period is reset. This means the contractor will need to achieve another three months of sustained good performance to qualify for an incentive payment.

The contractor's monthly service charge can be abated for poor performance. The abatement figure is calculated from the deficit point system, with each deficit point equalling $1. If the number of deficit points accrued across all 27 measures within a month is below 2 000, no abatement is applied. However, once this threshold is exceeded, the full abatement amount is enforceable. This abatement amount cannot exceed 10 per cent of the monthly services charge of approximately $5 million.

The contractor is able to receive an incentive payment for one or both service categories and still be liable for an abatement if performance in one or more of the 27 measures is poor.

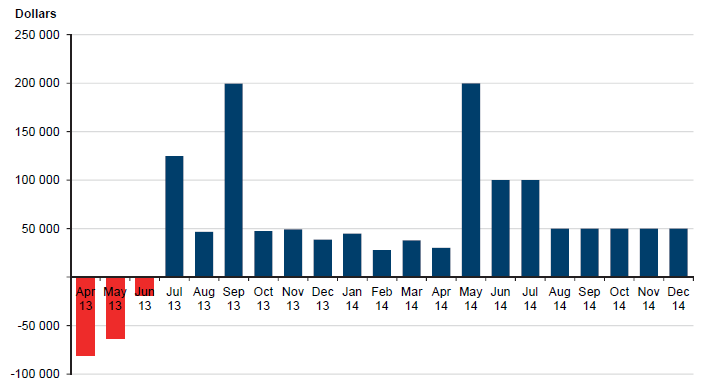

As at December 2014, PTV had paid $1.4 million in performance-linked incentives, and had applied abatements totalling $325 000 since the regime commenced in April 2013. Figure 3B shows the net incentive payment for each month during this period.

Figure 3B

Net incentive payment, April 2013 to December 2014

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from Public Transport Victoria.

Our analysis of data supplied by PTV shows that apart from the first three months of the new incentive and abatement regime, the contractor has consistently received incentive payments for meeting or exceeding performance requirements.

Although these results indicate sustained good performance, it is not possible to assess whether current standards—including incentives and abatement thresholds—have been set appropriately, as PTV did not document the rationale underpinning current performance benchmarks and how they equate to satisfactory performance.

PTV needs to review these measures prior to awarding the new myki contract, including whether the standards and related financial incentives are set at appropriate levels.

3.4 Monitoring of myki's performance