Patient Safety in Victorian Public Hospitals

Overview

This audit assessed whether patient safety outcomes have improved in Victorian public hospitals. This included assessing how effectively health services manage patient safety and whether they are adequately supported by the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), as the health system manager, and the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (VMIA), which provides insurance and risk management advice to public health services.

Despite indications that certain risks to patient safety have reduced over time, neither DHHS nor the four audited health services can demonstrate whether patient safety outcomes have improved.

VAGO has conducted two previous performance audits on patient safety in 2005 and in 2008. While progress has been made by the audited health services in relation to the management of patient safety—including the strengthening of their clinical governance—further improvement is needed.

Systematic failures by DHHS—some of which were identified over a decade ago in our 2005 audit—collectively indicate that it is not effectively providing leadership or oversight of patient safety. It is failing to adequately perform important statewide functions and is not giving patient safety the priority it demands.

VMIA is also not able to provide the best support to health services as it is not receiving comprehensive data from DHHS.

Patient Safety in Victorian Public Hospitals: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2016

PP No 149, Session 2014–16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Patient Safety in Victorian Public Hospitals.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

23 March 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Michael Herbert—Engagement Leader Fei Wang—Team Leader Janet Wheeler—Team Leader Ciaran Horgan—Analyst Samantha Carbone—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Chris Badelow |

This audit, continuing my focus on patient safety and the occupational health and safety (OHS) of healthcare workers examined whether patient safety outcomes have improved in Victorian public hospitals. This included assessing how effectively public hospitals manage patient safety and whether they are adequately supported by the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), as the health system manager, and the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (VMIA), as the risk adviser to public hospitals.

The audit found that there have been systemic failures by DHHS, indicating a lack of effective leadership and oversight which collectively pose an unacceptably high risk to patient safety. Some of these issues were identified over 10 years ago in our 2005 audit. These include failing to comply with its patient safety framework, not having an effective statewide incident reporting system and not using patient safety data effectively to identify overall patient safety trends. DHHS is not giving sufficient priority to patient safety. In doing so, it is failing to adequately protect the safety of hospital patients. DHHS has also not effectively collaborated with VMIA, and this has hindered the authority's ability to optimise its support to hospitals.

While some data exist that indicate improvement in patient safety in Victorian public hospitals, such as reductions in insurance claims and infection rates, these are only indicative. This means that neither DHHS nor the hospitals can know whether overall patient safety outcomes have improved.

It is positive that the audited hospitals have improved their clinical governance frameworks since our 2005 and 2008 audits of patient safety. Hospitals are making progress in improving their patient safety culture, which helps to encourage staff to report incidents. However, there is still significant work to do to improve their incident management, including strengthening incident investigations and reviews, and evaluating the effectiveness of the recommended actions from these. As a result of these weaknesses and a lack of system-wide data from DHHS, gaining an understanding of the overall prevalence and impact of patient safety risks is not possible.

I have made 13 recommendations aimed at improving DHHS' leadership and oversight of patient safety and the management of patient safety incidents by hospitals. I intend to follow up with the audited agencies to determine whether—and how effectively—my recommendations have been addressed.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

March 2015

Audit Summary

Patient safety is about avoiding and reducing actual and potential harm. An ageing and increasing population, a constrained health budget, and increasing patient complexity—where patients present with multiple diseases or disorders—are all creating increasing challenges for hospitals to effectively manage patient safety. While patient safety is related to quality of patient care, it differs in that it focuses on potential risks, rather than on whether the care has resulted in the best outcome.

VAGO has conducted two previous performance audits on patient safety—the first in 2005 and a follow-up audit in 2008.

The objective of this audit was to determine whether patient safety outcomes have improved in Victorian public hospitals by assessing whether:

- the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) has provided leadership and supported health services to improve patient safety outcomes

- the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (VMIA) supports health services to improve patient safety

- health services have improved patient safety outcomes and have effectively managed patient safety.

The audit included site visits to four health services—three metropolitan and one regional. Two of these audited health services were also included in the 2008 audit. We chose these to maintain some continuity and allow for an assessment of how well these health services have addressed past findings and recommendations.

Conclusions

Despite indications that certain risks to patient safety have reduced over time, neither DHHS nor health services can demonstrate whether overall patient safety outcomes have improved. Systemic failures by DHHS—some of which were identified over a decade ago in our 2005 audit—collectively indicate that DHHS is not effectively providing leadership or oversight of patient safety. It is failing to adequately perform important statewide functions and is not giving patient safety the priority it demands.

VMIA, whose role is to provide insurance and risk management advice to public health services, is not able to provide the best support to health services as it is not receiving comprehensive data from DHHS.

While progress has been made by health services since our 2005 and 2008 patient safety audits, further improvement is needed. Audited health services have significantly improved their clinical governance and are building a positive safety culture. However, not all health services have a comprehensive understanding of patient safety risks. While health services have improved their performance in patient safety, systemic statewide failures have undermined their capacity to be fully effective.

A number of measures to improve patient safety—such as policies, procedures and incident reporting—have also improved. However, weaknesses in incident investigations and evaluations of implemented actions from incident investigations mean the audited health services do not have a complete understanding of the effectiveness of improvements.

Findings

System-wide understanding of patient safety

A system-wide understanding of patient safety is important for identifying whether risks in receiving care have increased, whether patient safety outcomes have improved, and whether actions taken to prevent future incidents are effective. This requires oversight and leadership, which includes having an effective statewide framework or strategy, undertaking systematic analysis of comprehensive statewide incident data, and sharing guidance and the lessons learned across health services.

While DHHS developed a key patient safety framework in 2011—the Adverse Events Framework (AEF)—it has not complied with it. It has also not implemented an effective statewide incident reporting system. This limits DHHS' ability to have a system-wide understanding of patient safety and means it cannot effectively perform its role in providing leadership and oversight of the whole safety system.

Effective use of patient safety data

Although DHHS receives patient safety information from a number of sources, it does not aggregate, integrate or systematically analyse this data to identify overall patient safety trends. It receives information on infection and mortality rates, in addition to clinical incidents of varying severity, but it cannot demonstrate that it integrates these sources to understand overall trends.

DHHS established a number of advisory committees in 2014 that consider a broad range of information related to patient safety. However, there are a number of shortcomings with these, including the information from the committees being fragmented. This means that important trends or serious issues may be overlooked.

DHHS does not have assurance that health services consistently report sentinel events, which are the most serious type of clinical incident, despite this being a key patient safety requirement. This is because the DHHS reporting process only requires health services to report when sentinel events occur but does not require them to report when no events have occurred. Requiring health services to report even when no sentinel events have occurred would provide assurance to DHHS that all sentinel events have been reported. Not having a process in place resulted in one audited health service not submitting any sentinel event information to DHHS for 18 months due to resourcing and governance issues.

DHHS does not disseminate important lessons learned from sentinel events to health services on either an individual or sector-wide basis. This practice would identify deficiencies in systems and processes and inform future prevention of serious harm. Sentinel events are relatively infrequent and clear-cut incidents not related to a patient's pre-existing condition or disease, such as death from a medication error. They are commonly caused by hospital process deficiencies.

Specifically, one of DHHS' committees, the Clinical Incident Review Panel (CIRP)—which is responsible for reviewing sentinel events—has only provided feedback to individual health services on one out of 52 root cause analysis reports in 2013–14. Across the sector, there is ongoing delayed publication of DHHS' bulletin, Riskwatch, partly due to delays with the publication of CIRP's Sentinel Event Program Annual Report. The lengthy periods of non-reporting and lack of regularity of both of these publications undermines the importance of this information and calls into question the value of sentinel event reporting.

Performance monitoring

While DHHS regularly monitors health services' patient safety performance using a quarterly performance assessment score, this framework is inadequate. The patient safety indicators that inform the performance assessment score only partially measure patient safety within a health service and do not comprehensively reflect performance. Specifically, they do not provide clear performance information to DHHS or health services on a number of important patient safety indicators, such as trends in patient illness, trends in readmission rates or trends in mortality rates.

Collaboration with other government agencies

VMIA has supported health services to improve patient safety outcomes. However, despite repeated requests over a protracted time frame, VMIA has been unsuccessful in securing a range of DHHS statewide patient safety information to optimise its role in supporting health services.

Managing and monitoring patient safety

Health services should effectively manage patient safety through a strong clinical governance framework, promotion of a positive safety culture and effective incident management. Since our 2005 and 2008 patient safety audits, positive progress has been made by the four audited health services in developing clinical governance frameworks. This included establishing a relatively high level of scrutiny and quality control for higher severity incident reports. All of the audited health services have also been accredited by meeting a national standard for appropriate clinical governance.

There are also indications that progress has been made towards a positive safety culture. However, as in other jurisdictions, under-reporting remains an issue for a range of reasons.

All the audited health services have developed well-defined policies and procedures for incident reporting, to guide management and staff in the reporting, review and evaluation of clinical incidents. However, not all clinical incidents were investigated or reviewed. Investigations and reviews also varied in quality, and there was limited evaluation of the impact of the actions recommended by these reviews. Feedback from investigations to staff who had reported the incident also needed improvement.

The audited health services use a number of data sources to monitor patient safety, identify risks and implement improvements. At the local level, health services are aware of the types of patient safety risks that can occur and the likely impact of these. However, their understanding of the prevalence of these risks could be improved through better incident reporting, investigations and evaluations of actions from investigations. Further, a lack of system-wide data from DHHS limits health services' ability to understand statewide trends and prevalence, which would allow them to compare their performance with peer health services and learn lessons. Not having a full understanding of the prevalence and impact of patient safety risks means that the highest risks may not be identified and prevented or mitigated.

Recommendations

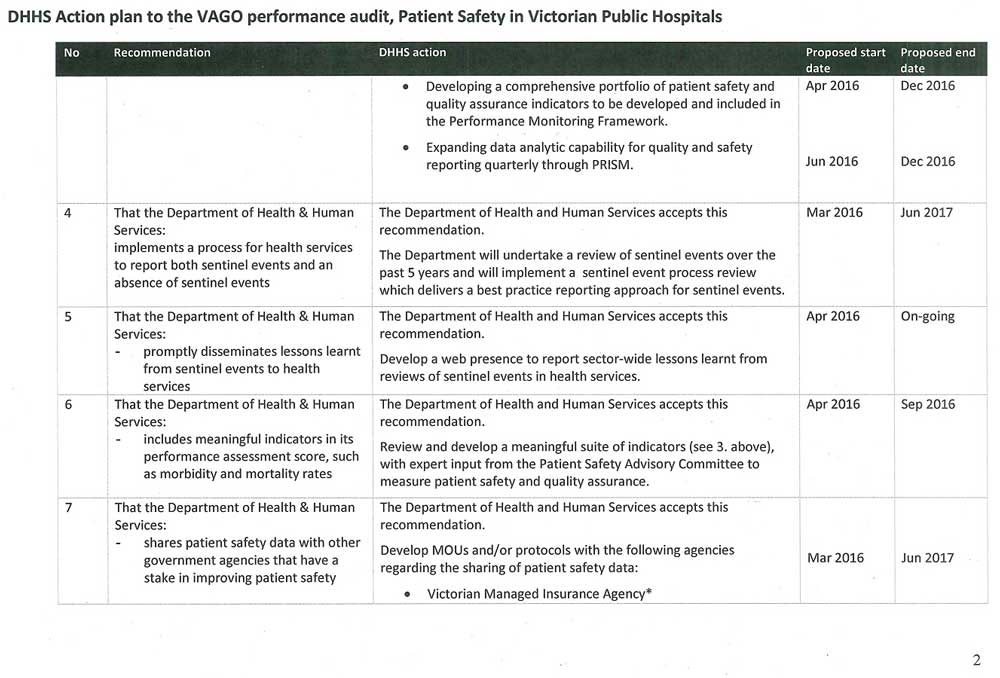

That the Department of Health & Human Services, as a matter of priority:

- reviews, updates and complies with its 2011 Adverse Events Framework, including incorporating a robust data intelligence strategy

- implements an effective statewide clinical incident reporting system

- aggregates, integrates and systematically analyses the clinical incident data it receives from different sources

- implements a process for health services to report both sentinel events and an absence of sentinel events

- promptly disseminates lessons learnt from sentinel events to health services

- includes meaningful indicators in its performance assessment score, such as morbidity and mortality rates

- shares patient safety data with other government agencies that have a stake in improving patient safety.

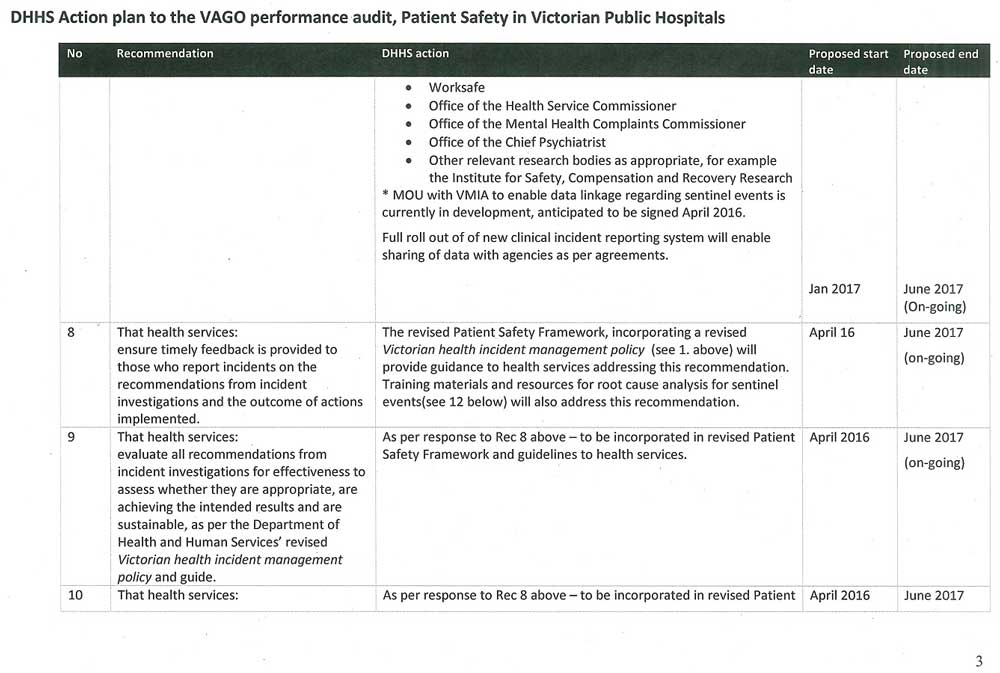

That health services:

- ensure timely feedback is provided to those who report incidents on the recommendations from incident investigations and the outcome of actions implemented

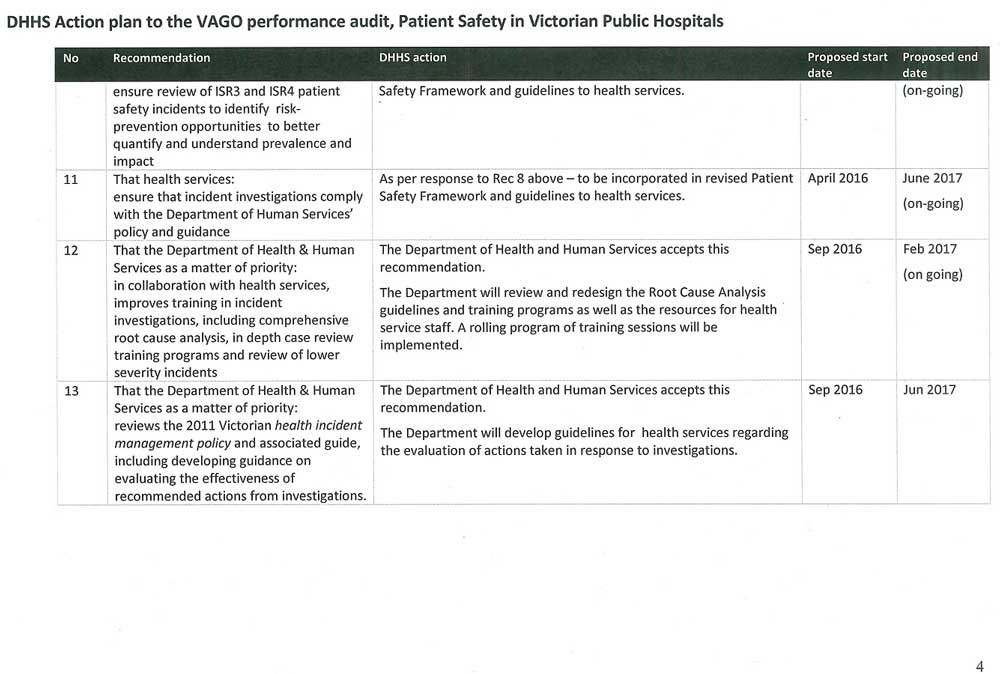

- evaluate all recommendations from incident investigations for effectiveness to assess whether they are appropriate, are achieving the intended results and are sustainable, as per the Department of Health & Human Services' revised Victorian health incident management policy and guide

- ensure review of ISR3 and ISR4 patient safety incidents to identify all risk-prevention opportunities to better quantify and understand the prevalence and impact of these incidents

- ensure that incident investigations comply with the Department of Health & Human Services' policy and guidance.

That the Department of Health & Human Services, as a matter of priority:

- in collaboration with health services, improves training in incident investigations, including comprehensive root cause analysis, in-depth case review training programs and review of lower severity incidents

- reviews its 2011 Victorian health incident management policy and associated guide, including developing guidance on evaluating the effectiveness of recommended actions from investigations.

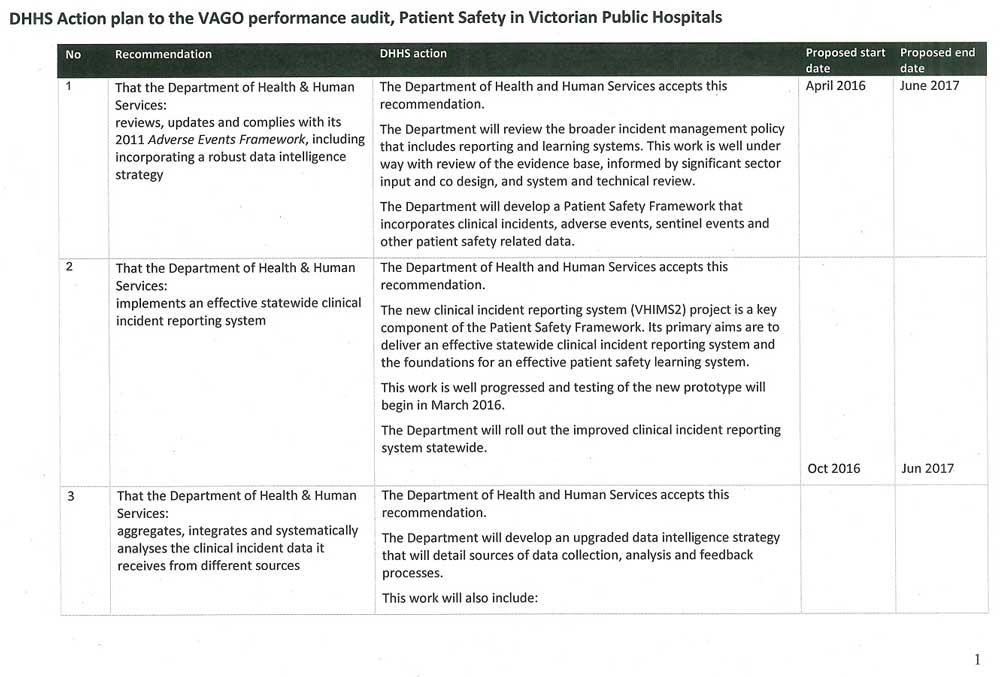

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Health & Human Services, the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority and the four audited health services throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier & Cabinet for comment.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Patient safety

Patient safety is about avoiding and reducing actual and potential harm. An ageing and increasing population, a constrained health budget, and increasing patient complexity—where patients present with multiple diseases or disorders—are all creating increasing challenges for hospitals to effectively manage patient safety. While patient safety is related to quality of patient care, it differs in that it focuses on potential risks, rather than on whether the care has resulted in the best outcome.

1.1.1 Clinical incidents

A clinical incident is any event that could have or did result in unintended harm to a patient that was avoidable. Harm can be caused by equipment failures, errors, infections acquired during the course of receiving treatment for other conditions or delays in treatment. Clinical incidents can result in longer stays in hospital, permanent injury or even death. As well as the impact on patients, this can increase costs, consume unnecessary resources and block access to beds for other patients. There can also be additional costs if compensation claims and legal action are taken against the hospitals involved.

All clinical incidents are potentially avoidable and range in severity from near misses to sentinel events leading to death.

Near misses

A near miss is a clinical incident that has the potential to cause harm but did not, due to timely intervention, luck or chance. Near misses can draw attention to risks of future events and are the most common type of clinical incident.

Adverse event

An adverse event is an incident that results in harm to a patient. Examples include:

- medication errors

- patient falls

- an infection as a result of treatment.

Sentinel event

A sentinel event is the most serious type of clinical incident. Sentinel events are relatively infrequent, clear-cut events that are not related to a patient's pre-existing condition or disease.

They are commonly caused by hospital process deficiencies and include:

- procedures involving the wrong patient or body part

- instruments left inside patient during surgery

- death from a medication error.

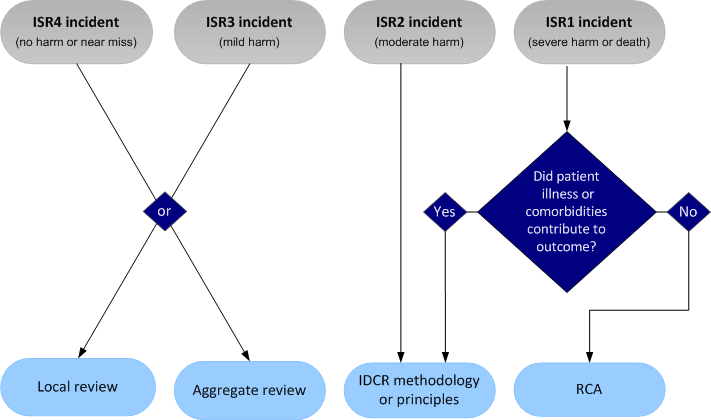

Incident severity rating

The Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) has developed an incident severity rating (ISR) scale that categorises clinical incidents according to the degree of harm, or potential harm, they cause to the person affected. The rating ranges from most severe (ISR1) to least severe (ISR4), as shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Incident severity ratings

Rating |

Severity of harm |

|---|---|

ISR1 |

Severe harm or death |

ISR2 |

Moderate harm |

ISR3 |

Mild harm |

ISR4 |

No harm or near miss |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from DHHS.

1.1.2 Prevalence of clinical incidents

It is difficult to determine the number of clinical incidents that occur in Victorian hospitals because under-reporting is common, as in other jurisdictions. However, the number of clinical incidents is an important indicator of patient safety for both hospitals and the entire health system. It is important to note that an increase in reported incidents may not necessarily mean deterioration in patient safety—it could instead indicate improvements in the reporting culture.

Higher severity clinical incidents (ISR1 and ISR2) represent only a small percentage of those reported in the health system, with lower severity incidents (ISR3 and ISR4) being much more common.

A 2006 study based on an analysis of 2003–04 Victorian hospital data for selected hospitals found that almost 7 per cent of the 979 834 sampled hospital admissions had experienced at least one clinical incident. Each clinical incident added $6 826 to the cost of treating the relevant patient, which equated to over $460 million for these hospitals. This represented 15.7 per cent of the total expenditure on direct hospital costs. The risk of in-hospital death increased as much as seven times for the patients experiencing clinical incidents, compared to other patients.

The prevalence of clinical incidents can be higher depending on the specific areas of care. For example, a 2006 study of Victorian elective surgery patients found that around 15.5 per cent had at least one clinical incident.

Photograph courtesy of DHHS.

1.2 Managing patient safety

There are several elements to the effective management of patient safety:

- Clinical governance framework—the board, managers, clinicians and staff share responsibility and accountability for patient safety, continuous improvement and fostering an environment of excellence in care.

- Incident management—reporting and investigating clinical incidents and evaluating actions to determine their effectiveness and sustainability.

- Patient safety culture—promoting an organisational culturethat places a high priority on patient safety, embraces reporting, proactively seeks to identify risks and supports improvement.

- Consumer participation—actively involve consumers in decision-making about treatment, which can improvesafety and enhance accountability.

- Open disclosure—the process of open discussion with a patient, and/or their family/support person about any incident that results in harm to that patient.

This audit examined the first three elements of patient safety management—clinical governance, incident management and patient safety culture—as these are considered central to improving patient safety outcomes in public hospitals.

We recently audited consumer participation in the health system, which is described in Section 1.5.

Department of Health & Human Services

DHHS' role in relation to patient safety is to:

- develop statewide policy

- fund, monitor and evaluate health services

- advise the Minister for Health, including collecting and analysing data, monitoring and benchmarking performance

- encourage safety and improvement in the quality of health services.

The Health Services Act 1988 requires DHHS to provide leadership and oversight of the overall health safety system.

Hospitals and health services

Victorian public hospitals are run by health services, which are incorporated public statutory authorities established under the Health Services Act 1988. One health service can manage multiple hospital campuses.

Health services, through their boards, are required under the Act to have systems in place to manage risk and care quality. All health services are required to implement locally based clinical risk management systems to identify and investigate clinical incidents in line with DHHS' Victorian clinical governance policy framework.

Victorian Managed Insurance Authority

The Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (VMIA) provides insurance and risk management advice to public health services. Hospitals may report clinical incidents to VMIA if they think there is a risk of litigation. As a risk adviser to public health services, VMIA also works with hospitals in an educational capacity around risk management and identifying system solutions.

1.3 Monitoring patient safety

Performance assessment score

DHHS regularly monitors patient safety using a quarterly performance assessment score (PAS). It is reported monthly to chief executive officers (CEO) and boards of health services, and the Minister for Health in the Victorian Health Services Performance Monitor report.

PAS is also made up of other indicators, including those that measure access and financial performance. In 2014, DHHS increased the patient safety component of PAS from 10 per cent to 30 per cent, and then to 40 per cent in 2015. The PAS patient safety component is derived from:

- preventative measures, such as staff immunisation rates and hand hygiene compliance

- Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemiainfection rates, a serious bacterial infection

- staff perceptions of care, which is sourced from the Victorian Public Sector Commission's People Matter Survey

- selected results from the Victorian Health Experience Survey, which measures patients' perceptions of care.

Program Report for Integrated Service Monitoring

DHHS also produces the Program Report for Integrated Service Monitoring (PRISM), which provides a broader view than the Victorian Health Services Performance Monitor by monitoring performance across a range of services provided by health services. It reports on a broader suite of indicators to PAS, such as hospital mortality and unplanned readmission rates. PRISM is distributed to health service CEOs and board chairs quarterly for benchmarking purposes.

Dr Foster Quality Investigator

Dr Foster Quality Investigator (Dr Foster) is an outsourced online portal provided by DHHS to the 14 largest health services to assist in improving patient safety. Development of Dr Foster began in 2013.

Dr Foster has three indicators—mortality, unplanned readmissions and length of stay. Health services can monitor these indicators over time and benchmark performance against peer hospitals.

1.4 Legislation and standards

Health Services Act 1988

The key objectives of the Health Services Act 1988 are to ensure that:

- services provided by hospitals are of a high quality

- all Victorians can have access to an adequate range of essential health services, irrespective of where they live or their social or economic status

- public hospitals are governed and managed effectively, efficiently and economically.

National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards

All Australian health services must be accredited under the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards, implemented nationally since 2013. DHHS only funds health services that are accredited. The standards cover the following 10 areas:

- governance for safety and quality in health services

- partnering with consumers

- preventing and controlling infections acquired during the course of receiving treatment for other conditions within a healthcare setting

- medication safety

- patient identification and procedure matching

- clinical handover

- blood and blood products

- preventing and managing pressure injuries

- recognising and responding to clinical deterioration in acute health care

- preventing falls and harm from falls.

1.5 Previous VAGO audits

Patient safety audits

VAGO has conducted two previous performance audits on patient safety—Managing Patient Safety in Public Hospitals, which tabled in 2005, and a follow-up audit, Patient Safety in Public Hospitals, in 2008. Both audits examined the patient safety system at the health service and state levels.

The 2005 audit identified:

- inconsistent clinical incident definition

- a lack of system-wide clinical incident monitoring

- poor governance arrangements

- no accountability framework for patient safety in the former Department of Human Services.

The 2008 audit found that some progress had been made in addressing the recommendations from the 2005 audit—for instance, the department was implementing a statewide incident reporting system and had established a clinical governance framework. However, health services had only implemented this governance framework to varying degrees.

Consumer Participation in the Health System, October 2012

This audit found that the former Department of Health had led implementation of consumer participation through strong policy direction. However, there were gaps in the department's implementation, and it needed to provide better oversight of health services' activities and evaluate the impact of its main policy. While there were sound guidelines, systems and practices in place, health services were at varying stages of embedding consumer participation in their organisational culture.

Infection Control and Management, June 2013

This audit examined the effectiveness of prevention, monitoring and control of infections in public hospitals, focusing on key activities of the former Department of Health and health services. It found that while overall Victorian hospitals have effective controls in place—with room for improvement in some areas—at the system level the department lacked appropriate data analysis and effective performance management to drive continuous improvement.

1.6 Audit objectives and scope

This audit examined whether DHHS, as the health system manager, has provided leadership and supported health services to improve patient safety outcomes.

The audit also assessed whether VMIA, as a risk advisor to public health services, has provided adequate support to health services in the areas of risk identification, prevention and management.

It also examined how effectively public hospitals manage patient safety and whether they have improved patient safety outcomes. Specifically, it assessed whether health services effectively monitor and have adequate systems in place—including appropriate clinical governance and incident management systems—to identify and learn from clinical incidents and drive improvement in patient safety.

This audit did not examine the broader framework of patient quality, which relates to whether patient care has resulted in the best outcome.

The audit included site visits to four health services—three metropolitan and one regional. Two of these audited health services were also included in the 2008 audit. We chose these to maintain some continuity and allow for an assessment of how well these health services have addressed past findings and recommendations.

1.7 Audit method and cost

The audit methods included:

- document review, including policies, procedures and previous audits

- review of patient safety governance and incident management systems

- a literature review of trends in key areas of patient safety

- review of performance information on patient safety, based on available information systems and databases

- interviews with hospital boards and senior clinical quality and safety staff

- focus groups with nurse unit managers, nurses and doctors

- analysis of incident data and trends.

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $485 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

2 Managing statewide patient safety risks

At a glance

Background

As the health system manager, the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) needs to monitor, understand and effectively respond to statewide patient safety risks. This includes supporting health services to improve patient safety.

Conclusion

Systemic failures by DHHS—some of which were identified over a decade ago in our 2005 patient safety audit—collectively indicate that DHHS is not giving sufficient priority to patient safety. It cannot demonstrate whether patient safety outcomes have improved and is failing in key system-wide functions such as oversight and leadership.

Findings

The Department of Health & Human Services:

- has not complied with its 2011 Adverse Events Framework

- has failed to implement an effective statewide clinical incident reporting system

- does not systematically aggregate, integrate or analyse patient safety data

- does not have assurance that health services report sentinel events

- does not disseminate important lessons learned from incidents to health services

- undertakes limited monitoring of health services' patient safety performance

- has not shared comprehensive data, which has limited the Victorian Managed Insurance Authority's ability to support health services.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health & Human Services, as a matter of priority:

- reviews, updates and complies with its 2011 Adverse Events Framework

- implements an effective statewide clinical incident reporting system

- aggregates, integrates and systematically analyses clinical incident data

- implements a process for reporting sentinel events and their absence

- promptly disseminates lessons learnt from incidents to health services

- includes meaningful indicators in its performance assessment score

- shares patient safety data with other relevant government agencies.

2.1 Introduction

The Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS), as the health system manager needs to monitor, understand and effectively respond to statewide patient safety risks. This includes disseminating key information and assisting hospitals to support improvements in patient safety outcomes.

The Victorian Managed Insurance Authority (VMIA), as the risk adviser to public health services, should provide adequate support to health services in the areas of risk identification, prevention and management.

2.2 Conclusion

Systemic failures by DHHS—some of which were identified over a decade ago in our 2005 patient safety audit—collectively indicate that it is not giving sufficient priority to patient safety. It cannot demonstrate whether patient safety outcomes have improved and is failing in key system-wide functions such as oversight and leadership. In doing so, it is failing to adequately protect the safety of hospital patients.

Poor sharing of DHHS data with VMIA has hindered VMIA's ability to provide the best support to health services to help them mitigate patient safety risks.

2.3 System-wide understanding of patient safety

A system-wide understanding of patient safety is important for identifying whether risks in receiving care have increased, whether patient safety outcomes have improved in health services, and whether actions taken to prevent future incidents are effective. This requires oversight and leadership, which includes having an effective statewide framework or strategy, undertaking systematic analysis of comprehensive statewide incident data, and sharing guidance and the lessons learned across health services. Providing health services with statewide data and other information allows them to compare their performance and target areas within their hospitals to improve patient safety outcomes.

While DHHS developed a key patient safety framework in 2011—the Adverse Events Framework (AEF)—it has not complied with it. It has also not implemented an effective statewide incident reporting system. This limits DHHS' ability to have a system-wide understanding of patient safety and means it cannot effectively perform its role in providing leadership and oversight of the whole safety system.

2.3.1 Patient safety framework

In 2011 DHHS developed the AEF, which is still its key patient safety framework. The core elements of the AEF are contained in a series of documents that include guidance for health services on clinical governance and incident management.

Despite the AEF being a key patient safety framework, a 2014 internal audit commissioned by DHHS found that the AEF was not being complied with. Key findings included:

- the reporting of all clinical incidents by health services through VHIMS—the Victorian Health Incident Management System, DHHS' incident reporting system—is not occurring in a systematic and consistent manner because of technical and design issues, which have resulted in variation in reporting and coding (this is contrary to the VAGO 2005 and 2008 audit recommendations, which DHHS accepted)

- clinical incident data from VHIMS is not being analysed across the health system (this is also contrary to the VAGO 2005 and 2008 audit recommendations)

- patient safety information held by DHHS is not integrated

- health services are not receiving lessons learned from critical clinical incidents

- sentinel events analysis and dissemination of the lessons learned are significantly delayed

- key AEF policy documentation has not been reviewed or updated since its creation

- VHIMS processes and resources have not been reviewed since their establishment.

DHHS accepted all the recommendations of this review, including that it:

- confirm AEF objectives, roles and accountabilities—DHHS has committed to completing this by July 2016

- document a strategy or plan to review, upgrade and maintain VHIMS—DHHS has completed a strategy and implementation plan, and a pilot is scheduled for March2016

- review and coordinate adverse event data collection and reporting processes

- improve governance arrangements for the AEF through the Patient Safety Advisory Committee (PSAC).

DHHS is yet to commit to a date when the last two recommendations will be implemented. These recommendations align with recommendations made in our 2005 and 2008 audits. That such clear and persistent shortcomings—identified by independent sources—have not been addressed reflects poorly on departmental leadership. It also calls into question the importance that DHHS places on clinical incident reporting, in particular, and patient safety generally.

2.3.2 Statewide clinical incident reporting system

While some data indicates there is improvement in patient safety in health services, without comprehensive system-wide data it is not possible to gain a full understanding. VHIMS is an ineffective statewide incident reporting system. Due to a number of limitations, it does not allow DHHS to use incident data—the primary patient safety data source—to understand the causes, prevalence, impact and trends of patient safety across Victorian health services. This limits DHHS' ability to know whether patient safety outcomes have improved in health services, if risks in receiving care have increased, and if actions taken to prevent future incidents are effective.

Such a significant shortcoming also prevents health services from comparing their performance and targeting areas within their hospital to improve patient safety outcomes. For example, collating clinical incidents within all emergency departments could enable health services to share, coordinate and evaluate responses to similar patient safety risks.

The lack of an effective statewide incident reporting system undermines key departmental roles including:

- guiding and supporting health services to manage clinical incidents

- analysing statewide incident data

- sharing statewide incident analysis and learnings with all health services

- reporting to the Minister for Health on patient safety issues

- reviewing statewide incident management processes and resources.

Our 2008 patient safety audit found that there was no statewide system to collect key clinical incident data from health services. At the time, Victoria was the only Australian jurisdiction in this position, and DHHS advised that it planned to address this recommendation as a priority. In response to our 2008 audit, DHHS developed VHIMS and, since 2011, health services have been required to report all clinical incidents on a monthly basis.

To date, VHIMS has cost over $9 million, yet none of its four objectives—outlined in DHHS' original 2008 project brief and described in Figure 2A—have been met. Overly complex and overlapping incident classification means that health services are reporting clinical incident data inconsistently. This not only undermines the integrity of the data, but means that DHHS cannot meaningfully aggregate and analyse the data.

Figure 2A

Assessment of VHIMS objectives against outcomes

|

VHIMS objective |

Assessment of achievement |

|---|---|

|

To develop a statewide, standard methodology for the way clinical incident information is reported within public health services |

Not achieved. Although VHIMS has introduced a statewide mechanism for incident reporting, inconsistencies in the classification of clinical incidents mean that there is no one standard approach used by health services to report data. |

|

To implement a mechanism that will enable statewide aggregation, analysis and trending of multi-severity level clinical incident data by the department |

Not achieved. DHHS acknowledges that it cannot aggregate clinical incident data to identify or analyse trends across the health system. It has yet to produce a meaningful statewide report detailing different severity levels of clinical incident data. |

|

To establish appropriate mechanisms for departmental representatives and in-scope health services to evaluate the clinical incident data, identify trends and share relevant information such that quality improvements can be better targeted |

Not achieved. DHHS acknowledges that it cannot evaluate clinical incident data, identify trends or share information with health services to target improvements in patient safety outcomes. |

|

To work collaboratively with the Health Services Commissioner, WorkSafe Victoria and VMIA—to whom health services must submit incident data—with the aim of streamlining reporting processes to these organisations. |

Not achieved. VHIMS has not streamlined reporting processes to the Health Services Commissioner, WorkSafe Victoria and VMIA. The Health Services Commissioner receives consumer complaints outside of VHIMS and has an ad hoc arrangement with health services in terms of receiving consumer complaints from VHIMS. Although VHIMS allows health services to notify VMIA, only 3 per cent of medical indemnity claims submitted to VMIA originate from VHIMS. DHHS has acknowledged that 'VMIA are also limited in their capacity to reduce claims due to the absence of VHIMS statewide data analysis'. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from DHHS.

DHHS has known about shortcomings with VHIMS since its implementation in 2011. A number of reviews since then have repeatedly identified data inconsistencies and poor system design and have questioned the value of VHIMS:

- A 2011 pilot reported significant data quality issues, including the complexity of incident classification, a cumbersome user interface and difficulty in generating meaningful reports.

- A 2012 DHHS VHIMS reliability audit, funded by VMIA, identified data inconsistencies and recommended strategies to simplify incident classification. It also found that users had difficulty in defining a valid clinical incident, as opposed to a near miss or an inevitable part of a patient's care.

- The 2013 VAGO audit Occupational Health and Safety Risk in Public Hospitalsfound that the system was not user-friendly, thereby hindering accurate and consistent input by the reporting staff member.

- The 2014 internal audit of DHHS' AEF found that incident classification is still inconsistently applied across hospitals, requires extensive manual manipulation and data validity cannot be assured—Figure 2B provides an example.

- The 2015 VAGO audit Occupational Violence Against Healthcare Workersalso found that there was a complex system interface. Staff members indicated that there was considerable confusion and difficulty in using the system.

DHHS has acknowledged that clinical incident reporting is not occurring in a systematic and consistent manner.

Figure 2B

Difficulty classifying incidents in VHIMS

|

The following example of a clinical incident demonstrates the difficulty in classifying incidents in VHIMS in a consistent manner in order to produce comparable data. In this incident, a patient had a fall and was entered into VHIMS as:

However, DHHS documentation demonstrates that the incident should have been classified as:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by DHHS.

DHHS is currently undertaking a VHIMS improvement project, which aims to address the issues with this system. This project includes the following key actions, which were recently completed:

- selecting 10 health services for a pilot

- conducting stakeholder forums on the VHIMS clinical incident module, with 36health services and agencies

- hiring a VHIMS specialist from within the health sector

- commissioning an adverse events literature review.

A number of actions are remaining, including a technical review by an external provider, training needs analysis and departmental evaluation. The project is expected to be finalised by May 2017. It is too early to conclude how successful the outcome of the project is likely to be.

2.4 Effective use of patient safety data

Although DHHS receives patient safety information from a number of sources, it does not aggregate, integrate or systematically analyse this data. It receives information on infection and mortality rates, in addition to clinical incidents of varying severity—from near misses through to the most serious sentinel events—but it cannot demonstrate that it integrates these sources to understand overall trends. This includes how well a particular hospital or the sector more broadly is performing in respect to patient safety.

2.4.1 Patient safety advisory committees

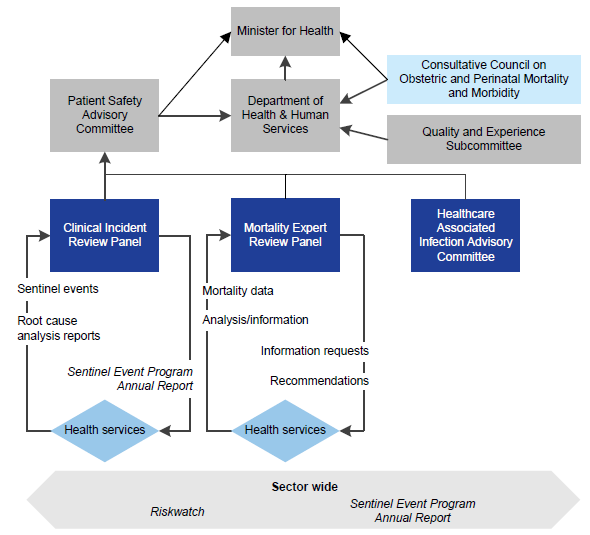

DHHS established a number of advisory committees in 2014, shown in Figure 2C. These committees consider a broad range of information related to patient safety, including mortality, sentinel events, infections acquired during the course of receiving treatment for another condition, and VHIMS issues.

However, the information from these committees is fragmented. This means that important trends or serious issues may be overlooked.

Figure 2C

The Department of Health & Human Services' current patient safety committee structure

Note: The Consultative Council on Obstetric and Perinatal Mortality and Morbidity is not a departmental committee—it is a statutory authority appointed by the Victorian Government. However, it does have a patient safety function.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by DHHS.

Patient Safety and Advisory Committee

In June 2014, PSAC was established, with three subcommittees reporting to it, as outlined in Figure 2C. PSAC's purpose is to provide leadership and strategic policy advice to the Minister for Health on:

- patient safety performance

- emerging trends

- strategies for preventable harm reduction

- innovative solutions, with a focus on overcoming inequities in care

- specific matters referred to it for consideration.

PSAC's role includes reviewing, assessing and providing recommendations to DHHS based on input from its subcommittees. However, up until September 2015, PSAC has never provided advice or recommendations to the minister, despite a significant patient safety failing outlined in Figure 2E. Ministerial reporting has recently started occurring through DHHS rather than directly to the minister.

While PSAC works with DHHS on patient safety issues, it does not integrate or synthesise data to identify overall patient safety trends. The absence of ministerial reporting—until recently—and particularly the failure to integrate and synthesise data, detracts from PSAC's ability to effectively contribute to system-wide patient safety.

Clinical Incident Review Panel

The Clinical Incident Review Panel (CIRP) is DHHS' longest serving patient safety committee. It is responsible for reviewing the most serious clinical incidents, sentinel events, but has not done so effectively or efficiently. Timely review of these events demands high priority and responsiveness, as identifying deficiencies in systems and processes can lead to the prevention of serious and avoidable harm in the future.

There were 53 sentinel events reported by health services in 2013–14, 34 in 2012–13, and 41 in 2011–12. CIRP's effectiveness has been undermined by several factors:

- On average, health services take 99 days after notifying DHHS to submit root cause analysis (RCA) reports. This does not comply with DHHS' Clinical Risk Management Policy, which requires health services to provide an RCA report within 60 days of notification. Further, DHHS does not have assurance that health services consistently comply with reporting sentinel events, despite this being a key patient safety requirement. This is because the DHHS reporting process only requires health services to report when sentinel events occur but does not require them to report when no events have occurred. This resulted in one audited health service not submitting any sentinel event information to DHHS for 18 months. The health service advised this was due to a key vacant management position and issues with its governance structure. A total of six sentinel events, which occurred between 2012 and 2014, were not reported to DHHS until May 2014. At no point did the department query this absence of sentinel events, when, typically, health services of this size and level of activity would be expected to have at least one sentinel event over such a period.

- There are prolonged delays in reviewing RCA reports submitted by health services. Health services can wait up to 16 months before CIRP reviews an RCA report—seven months on average. At 30 September 2015, CIRP had 33 unprocessed RCA reports, which represents a backlog of approximately one year of committee work. During this audit, CIRP has worked to address this backlog by scheduling an additional meeting in November 2015 and an additional meeting in 2016. The November 2015 meeting reduced the number of unprocessed RCAs awaiting CIRP review to 25. Figure 2D shows the reporting and review dates for eight sentinel events, including time elapsed.

- CIRP is failing to provide feedback on RCA reports to health services on an individual and sector-wide basis. CIRP provided feedback to individual health services on 80 per cent (61 of 76) of RCA reports received from 2011–12 to 2012–13, but only provided feedback to health services on one out of 52 RCA reports received in 2013–14.Across the sector, there is ongoing delayed publication of DHHS' bulletin, Riskwatch,partly due to delays with the publication of CIRP's Sentinel Event Program Annual Report. For instance, the latest bulletin was released in December 2014, despite it being a monthly publication. There was no annual report for the 2013–14 or 2014–15 period, and data for the 2011–12 and 2012–13 annual report was published in May 2014—almost three years after the first sentinel event included in the report. These extended periods of non-reporting and the lack of regularity of both publications undermines the importance of this information and calls into question the value of sentinel event reporting.

CIRP has clearly not been adequately resourced by DHHS to effectively deliver on its objectives. CIRP has been failing to manage its existing workload, and there was a risk that, without significant changes, it would not be in a position to review growing numbers of RCA reports in any meaningful time frame. DHHS has advised that it is currently reviewing its sentinel event reporting program but has not committed to when this would be completed.

Figure 2D

CIRP review times

|

Sentinel event |

RCA report received by DHHS |

CIRP review date |

Time elapsed |

|---|---|---|---|

|

a |

June 2014 |

November 2015 |

16 months |

|

b, c, d |

August 2014 |

November 2015 |

14 months |

|

e |

April 2014 |

June 2015 |

13 months |

|

f, g |

June 2014 |

August 2015 |

13 months |

|

h |

July 2014 |

August 2015 |

13 months |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information provided by DHHS.

Photograph courtesy of DHHS.

The Consultative Council on Obstetric and Perinatal Mortality and Morbidity

CCOPMM is not a departmental committee—it is a statutory authority appointed by the Victorian Government. DHHS supports the work of CCOPMM by providing resources to carry out its legislative functions, including data management. CCOPMM is responsible for reviewing and classifying all perinatal (i.e. foetal and infant) and paediatric deaths in Victorian hospitals to provide advice to the Minister for Health, DHHS and the health sector more broadly on how such deaths could be prevented.

CCOPMM did not alert DHHS to an abnormally high rate of perinatal deaths at a rural health service in 2013 and 2014 until March 2015. An independent investigation commissioned by DHHS found that of the 11 perinatal deaths at the health service in 2013 and 2014, seven were likely to have been avoidable and arose from deficiencies in clinical care. This investigation also found that the health service sustained a higher than expected rate of perinatal deaths, particularly for a service that was considered 'low risk'.

The chair of CCOPMM indicated that it has not been established as an early warning system for abnormally high perinatal deaths. However, it is the only committee within DHHS that receives notification of perinatal deaths, and health services are required by DHHS to alert CCOPMM to all perinatal deaths. The audit team could not fully assess its operations as CCOPMM is not obliged to provide information to any oversight body. Given the seriousness of these events and questions around the effectiveness of CCOPMM, it is concerning that it is beyond the scrutiny of the Auditor‑General.

Failures in this case by DHHS and the health service are detailed in Figure 2E. In the period prior to CCOPMM notifying DHHS, a number of credible sources communicated concerns to DHHS.

Figure 2E

Chronology of incidents at a rural health service

|

Year |

Event |

|---|---|

|

2010 |

An internal report by the rural health service's director of medical services advises that its obstetric service was under extreme risk. This was due to the rapidly increasing clinical workload and the expected growth in the health service's catchment. |

|

February 2013 |

The rural health service notifies DHHS about growing maternity demand, seeking additional funding to manage this demand. DHHS' internal emails note that the director of obstetrics at a large metropolitan health service is concerned that the rural health service does not have sufficient medical support/capacity to grow the service. The director of obstetrics at this metropolitan health service resigns as chair of the Maternity Quality and Safety Committee. The director expresses serious concerns to DHHS about the safety and quality of maternity services in that area, which includes the rural health service. |

|

The rural health service advises DHHS that is has procedures in place with the metropolitan health service to manage higher risk mothers and infants. |

|

|

March 2013 |

DHHS advises the rural health service it would consider providing additional funding subject to agreeing to a solution. |

|

June 2013 |

A memorandum of understanding between the rural health service and the metropolitan health service described above is signed. Registrars are scheduled to 'start soon'. |

|

July 2013 |

The rural health service does not meet two core national accreditation requirements:

|

|

November 2013 |

Following a standard rectification period, the rural health service passes accreditation. |

|

February 2014 |

The Australian Nurses and Midwifery Federation (ANMF) communicates concerns by letter to the director of nursing at the rural health service regarding what they viewed as 'an elevated level of clinical risk' at the health service. |

|

The nursing and midwifery workforce development coordinator at the regional office emails regional DHHS staff advising that the rural health service 'is possibly operating' outside DHHS' Capability Framework for Victorian Maternity and Newborn Services. This framework identifies the core competencies required for delivery of maternity and newborn services in funded health services. |

|

|

Mid 2014 |

CCOPMM contacts the rural health service to enquire whether certain deaths had been investigated. |

|

March 2015 |

CCOPMM alerts DHHS to the cluster of perinatal deaths at the rural health service. |

|

A midwife from a large metropolitan specialist hospital commences on site at the rural health service. |

|

|

External expert investigation of the rural health service commences. |

|

|

April 2015 |

The Minister for Health appoints a delegate to the rural health service board of directors. |

|

June 2015 |

External expert investigation report delivered to DHHS. |

|

July 2015 |

Retirement of senior obstetrician at the rural health service. |

|

August 2015 |

An interim chief executive officer is appointed to the rural health service. |

|

October 2015 |

At the request of DHHS, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare reports on its review of DHHS' management of a critical issue at the rural health service. The report concludes that, 'The department's response to each of these issues was proportional and appropriate, with the exception of the regional office response to the concerns raised by the ANMF'. |

|

The Minister for Health dismisses the board of the rural health service and appoints an administrator. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from DHHS.

Internal communication within DHHS highlighting concerns resulted in fragmented responses. The warning flags included:

- demand for maternity services outstripping clinical capacity

- professional competency issues

- maternal safety concerns raised by clinicians at the most senior levels

- reports of practice outside of DHHS' capability framework.

There was no central point where these concerns were integrated and collectively assessed. Appropriate and timely action could have averted some of the serious consequences.

Mortality Expert Review Panel

The Mortality Expert Review Panel (MERP) was established in 2014. Its function is to provide independent advice and make recommendations to DHHS and health services on reducing patient risk and mortality rates through the introduction of targeted initiatives.

MERP is reviewing, analysing and reporting on mortality outliers in accordance with its terms of reference.

Healthcare Associated Infection Advisory Committee

Established in 2014, the Healthcare Associated Infection Advisory Committee's (HAIAC) function is to provide strategic advice and support to PSAC on infections acquired during the course of receiving treatment for other conditions. It also alerts DHHS to potential opportunities for consideration regarding emerging infections and Victoria's response to these.

HAIAC is functioning in accordance with its terms of reference.

Quality and Experience Subcommittee

The Quality and Experience Subcommittee was established in February 2016. Its role includes overseeing key projects and approaches to improve safeguarding patient and client safety, with a particular focus on areas of systemic and departmental risk.

As this subcommittee was only recently formed, it is too early to assess its effectiveness.

Patient safety advisory committees prior to 2014

The only departmental patient safety committee in existence between 2011 and late 2014 was CIRP, which suggests a limited focus on patient safety at DHHS during that time. As CIRP focuses only on sentinel events, there were no committees reviewing other aspects of patient safety.

Shortcomings with DHHS' patient safety committees extend beyond the current committee structure. Departmental responsiveness to its own committees has been a persistent issue. A 2010 independent review of previous departmental safety committees concluded that from 2007 to 2009 they were not performing optimally. It also found that committee members were frustrated by issues including:

- delays in departmental action

- limitations in their ability to raise issues with DHHS.

2.5 Performance monitoring

DHHS' framework for regularly monitoring patient safety across health services is inadequate. The patient safety indicators informing the quarterly performance assessment score (PAS) do not comprehensively reflect performance. Specifically, they do not provide clear performance information to DHHS or health services on a number of important patient safety outcomes, such as trends in patient morbidity, trends in readmission rates or trends in mortality rates.

PAS is also made up of other indicators, including those that measure access and financial performance. It is positive that in 2014 DHHS increased the patient safety component of PAS from 10 per cent to 30 per cent and then to 40 per cent in 2015. This reflects an increasing recognition of the importance of patient safety in the overall performance of health services.

However, the patient safety element of PAS is derived solely from 'lead' indicators that predict future events, such as hand hygiene, worker immunisation rates and staff perceptions of safety culture. PAS does not include lag indicators, which follow an event, such as readmission and mortality rates. On its own, PAS only partially measures patient safety within a health service. In this context, it is notable that the health service discussed in Figure 2E had a high PAS despite significant failures and higher than expected mortality rates.

DHHS has information on other patient safety indicators that would, in addition to the PAS indicators, provide more meaningful performance information. It routinely collects morbidity data—specifically rates of complications and readmissions—and mortality data at the health service and patient level. This data can be readily used by DHHS to identify particular areas within a health service, such as a surgical unit that has higher rates of complications or readmissions than surgical units in similar hospitals. While DHHS monitors some of these measures through the Program Report for Integrated Service Monitoring (PRISM), this report's primary purpose is to provide benchmarking information to health services and is not an accountability tool.

A 2015 report, Managing health services through devolved governance, published by The King's Fund, noted that Victoria—and, in fact, Australia—is lagging behind a number of other jurisdictions in using timely, easily accessible and easily interpretable data on performance to support health services to identify, prevent and manage risks.

Figure 2F compares Victoria's patient safety indicators with another Australian jurisdiction. This jurisdiction represents a better practice example, using a suite of both lead and lag indicators, including rates of complications, readmissions and mortality, and investigations of patient complaints and sentinel events. All of these are integrated into one scorecard for each health service, which more comprehensively reflects patient safety in health services.

Figure 2F

Comparison of health service monitoring

|

Other jurisdiction |

Victorian PAS indicators |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Indicator |

Description |

Lead or lag |

|

|

Mortality and morbidity indicators |

|||

|

Seven surgical procedures |

|

Lag |

No |

|

Four medical complications |

|

Lag |

No |

|

Two mental health conditions |

|

Lag |

No |

|

Seven common obstetrics and gynaecology procedures |

|

Lag |

No |

|

System-wide indicators |

|||

|

Sentinel events |

|

Lag |

No |

|

Governance and patient experience |

|

Lead |

|

|

Infections |

|

Lag |

|

|

Mortality |

|

Lag |

No |

|

Mental health |

|

Lag |

|

|

Radiology |

|

Lead |

No |

Note: Victorian PAS financial and access indicators have not been included in this comparison.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on information from an Australian jurisdiction.

2.6 Collaboration with other government agencies

VMIA has three roles:

- risk management adviser to health services

- adviser to the government

- state insurer.

The audit found that VMIA has supported health services to improve patient safety outcomes. However, poor sharing of DHHS data with VMIA has hindered VMIA's ability to systematically prioritise its support to health services and optimise its role in supporting health services and DHHS to mitigate patient safety risks.

VMIA has recognised the importance of enhancing its role through better patient safety data. Its current Enterprise Data Strategy has been stalled by unsuccessful attempts to obtain access to a range of statewide datasets related to patient safety, such as the Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset, Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset, Victorian Perinatal Data Collection or incident reporting from VHIMS. DHHS cites data reliability and confidentiality concerns with regard to sharing data and no agreement has been reached. This is a lost opportunity, as data sharing between VMIA and DHHS would have benefits for both parties.

This issue is not new to the health sector—a decade ago, VAGO's 2005 patient safety audit concluded that 'greater coordination of data collection systems and collaboration between the [former] Department of Human Services and the VMIA will be needed for this system to reach its potential'. Despite repeated requests over a protracted time frame, VMIA has been unsuccessful in securing access to a range of statewide patient safety information.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health & Human Services, as a matter of priority:

- reviews, updates and complies with its 2011 Adverse Events Framework, including incorporating a robust data intelligence strategy

- implements an effective statewide clinical incident reporting system

- aggregates, integrates and systematically analyses the clinical incident data it receives from different sources

- implements a process for health services to report both sentinel events and an absence of sentinel events

- promptly disseminates lessons learnt from sentinel events to health services

- includes meaningful indicators in its performance assessment score, such as morbidity and mortality rates

- shares patient safety data with other government agencies that have a stake in improving patient safety.

3 Managing patient safety in public hospitals

At a glance

Background

Health services should effectively manage patient safety through strong clinical governance, a positive safety culture, robust incident management and response, and reliable monitoring of patient safety outcomes.

Conclusion

It is not possible to determine whether patient safety has improved in Victorian hospitals due to limitations at the local and system-wide levels. Progress has been made by health services since VAGO's 2005 and 2008 audits, however, there is still further work to be done to improve the management of patient safety.

Findings

Health services:

- have significantly improved their clinical governance

- could improve their understanding of the prevalence and impact of patient safety risks

- undertake limited evaluation to assess the effectiveness of recommended actions from incident investigations

- could improve investigation and analysis of less severe incidents.

Recommendations

That health services:

- ensure timely feedback on recommendations from incident investigations

- evaluate all recommendations from incident investigations for effectiveness

- ensure review of lower severity incidents to identify risk-prevention opportunities

- ensure that incident investigations comply with the Department of Health & Human Services' policy and guidance.

- That the Department of Health & Human Services, as a matter of priority:

- in collaboration with health services, improves training in incident investigations

- reviews its 2001 Victorian health incident management policy and guide.

3.1 Introduction

Health services should effectively manage patient safety through a strong clinical governance framework, promotion of a positive safety culture and effective incident management. They should also ensure reliable monitoring and effective use of data to identify risk and implement improvements in patient safety.

3.2 Conclusion

Despite some indications that patient safety has improved in Victorian public hospitals, it is not possible to conclusively determine if this is the case due to limitations at the health service level and a lack of system-wide data. While progress has been made by the audited health services since VAGO's 2005 and 2008 patient safety audits, there is still further work to be done in improving hospitals' management of patient safety.

At the local level, health services are aware of the types of patient safety risks that can occur and the likely impact of these. However, their understanding of the prevalence of these risks and the effectiveness of their controls to mitigate them could be improved through better incident reporting, investigations and evaluation of actions from investigations. While health services have improved their performance in managing patient safety, systemic statewide failures limit their effectiveness.

3.3 Managing patient safety

It is critical that health services have effective processes in place to manage patient safety in public hospitals to minimise the chances of clinical incidents occurring. Managing patient safety incorporates a number of key elements, including strong clinical governance, a positive patient safety culture and effective incident management.

Since our 2005 and 2008 patient safety audits, audited health services have significantly improved their clinical governance. While health services have well-defined policies and procedures for incident reporting, and reporting has improved, there is room for improvement in relation to incident investigation.

3.3.1 Clinical governance

Clinical governance establishes accountability frameworks for patient safety and quality of care at all levels of the health system—from the board and managers to clinicians and staff. The Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) requires all health services to have an effective clinical governance framework.

Positive progress has been made by the audited health services in developing clinical governance frameworks, compared to the 2005 and 2008 VAGO patient safety audit findings. All have developed frameworks and key policies and procedures to support patient safety. This includes establishing a relatively high level of scrutiny and quality control for the incidents with the highest incident severity ratings (ISR)—ISR1 (severe harm/death) and ISR2 (moderate harm). Further, all of the audited health services have been accredited by meeting a national standard that relates to appropriate clinical governance.

3.3.2 Patient safety culture

Strong clinical governance should promote a positive safety culture—one that recognises the inevitability of error, embraces reporting, proactively seeks to identify risks and supports improvement. One of the key benefits of a positive safety culture is a stronger commitment by staff to reporting clinical incidents. When staff report clinical incidents, it allows health services to identify and learn from these events and make improvements to prevent reoccurrences.

Incident management includes reporting and investigating clinical incidents, and evaluating recommended actions from investigations to determine their effectiveness. Investigations of incidents assist in identifying risks and breakdowns in systems and developing ways to reduce or eliminate the risk of reoccurrence. Feedback on the recommendations that emerge from the investigation and the outcome of the actions implemented should be provided in a timely manner to those who reported the incident.

At all of the audited health services, there are indications that progress has been made towards a positive safety culture, including an increase in reporting of clinical incidents. Health service employees attribute this rising trend to an improving culture, rather than an increase in clinical incidents. However, as in other jurisdictions, under-reporting remains an issue for a range of reasons.

We conducted focus groups of nurses, doctors and nurse unit managers—who typically manage a ward—at all audited health services to understand their perceptions of patient safety culture. These focus groups and interviews uniformly indicated that progress has been made towards an improving culture. Common themes from these focus groups are outlined below:

- Patient safety is often talked about as a priority by leadership.

- There is a 'no blame' culture when clinical incidents occur.

- There is support from the organisation's quality and safety teams to assist in the review and investigation of serious incidents.

- Despite the time-consuming nature of incident reporting and complex reporting forms, most staff stated that they would still report incidents. At one health service, junior nurses commented that they would be reprimanded if it was found that they had not reported an incident.

Reporting clinical incidents

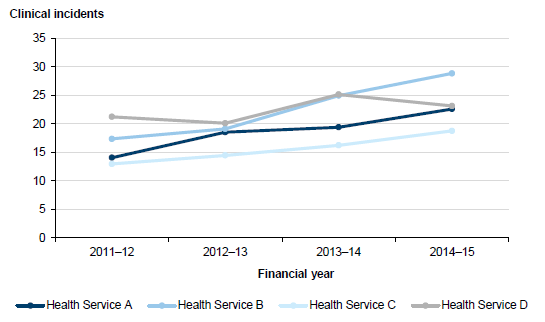

Data from the four audited health services, shown in Figure 3A, demonstrates that the rate of reported clinical incidents is increasing, although not uniformly. While the data does not on its own identify the reasons for the overall increase, all employees consulted during the audit—from clinical staff to senior executives—attributed this to a positive and improving patient safety culture, rather than an increase in clinical incidents.

However, it is clear that there are still barriers to reporting incidents—for instance, a 2013 internal audit by one of the audited health services found that there was still significant room for improvement in reporting. The internal audit compared patient medical records, in which incidents are recorded, with the number of incidents reported in the Victorian Health Incident Management System (VHIMS)—DHHS' statewide reporting system—over the same period. It found that 13 per cent of all falls, 70 per cent of pressure injuries and 90 per cent of accidental lacerations and cuts were not captured in VHIMS. The internal audit did not cover other clinical incident categories, such as medication errors. The other audited health services had not undertaken similar internal audits.

Figure 3A

Clinical incidents per 1 000 bed days at audited health services

Note: The

graph compares clinical acute incidents at the four audited health services,

but excludes mental health incidents due to counting anomalies.

Source: Victorian

Auditor-General's Office based on data supplied from the four audited health

services.

Focus group respondents and interview participants also identified a range of barriers to reporting clinical incidents. Across the four audited health services, all identified the time-consuming nature of incident reporting and the complexity of VHIMS as the two most significant deterrents, as shown in Figure 3B. Respondents from two of the audited health services also reported significant concerns in the value of reporting incidents, indicating that the culture of patient safety could still be improved in some health services. DHHS analysis of robust statewide clinical incident data, in consultation with health services, should be able to determine the reasons for underlying trends in clinical incident reporting over time.

Figure 3B

Barriers to reporting clinical incidents reported in

interviews and focus groups with the four audited health services

Barrier to reporting clinical incidents |

Reported in interviews and focus groups |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Health |

Health |

Health |

Health | |

Total responses |

12 |

16 |

15 |

14 |

Time constraint |

10 |

11 |

14 |

13 |

Complexity of VHIMS |

10 |

9 |

12 |

13 |

Lack of feedback |

5 |

9 |

8 |

5 |

No perceived value in reporting |

2 |

5 |

7 |

6 |

Note: Aggregate

numbers have been used.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's

Office based on focus groups and interviews at the four audited health

services.

3.3.3 Incident management