Payments to Visiting Medical Officers in Rural and Regional Hospital

Overview

Independently contracted, fee-for-service visiting medical officers (VMOs) are a common feature in public rural and regional health services. In 2010–11, health services spent $108 million on VMOs. This audit examined the appropriateness and transparency of payments to VMOs, including the adequacy of contractual arrangements.

Payments to VMOs by rural and regional health services are appropriate and transparent. Testing of a statistically significant sample of VMO payments at the four audited health services found no material errors or evidence of inappropriate VMO billing. Rural and regional health services, with feedback from review work by the Department of Health (the department), have improved their VMO payment systems. The department's implementation of an IT payment system for small rural hospitals will also assist.

Health services now need to focus on achieving the best possible outcomes through contracted VMO arrangements. None of the audited health services were assessing VMO performance against their contracts, and only one was strategically considering their use of VMOs compared to other employment options. Given the essential nature of medical services, these contracts should be closely managed.

Rural and regional health services also lack clarity about the legal implications of their VMO arrangements. Aspects of VMO arrangements, for example where lump sum payments to VMOs are processed through payroll, and VMOs are given access to salary packaging, imply that they are employees of the health services rather than independent contractors. Health services need clear advice about the employment status of VMOs and the arrangements needed to meet the definition of that status.

Payments to Visiting Medical Officers in Rural and Regional Hospital: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2012

PP No 132, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Payments to Visiting Medical Officers in Rural and Regional Hospitals.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

23 May 2012

Audit summary

Independently contracted, fee-for-service visiting medical officers (VMO) are a common feature of medical service delivery in rural and regional health services. Metropolitan and larger regional hospitals have shifted mainly to salaried medical staff. However, the reliance of rural health services on local general practitioners to provide hospital-based services, and the tighter labour market and lower service volumes in these areas, mean contracted VMOs remain the predominant model in rural health services.

The use of VMOs requires health services to establish and manage effective contractual arrangements, and to make accurate and appropriate payments. Past Ministerial and Parliamentary inquiries, and audits by this office, have repeatedly identified problems with the adequacy of payment systems and monitoring, and with information gaps that prevent proper checking and accuracy. This continues to cast doubt on VMO billing and payment practices, for an expenditure that totalled $108 million in rural and regional health services in 2010–11.

This audit examined the appropriateness and transparency of payments to VMOs by rural and regional health services including whether:

- contractual arrangements for VMOs are adequate

- health services use robust systems and processes to manage VMO arrangements.

The audit included four rural or regional health services and the Department of Health (the department).

Conclusions

Payments to VMOs by rural and regional health services are appropriate and transparent. Rural and regional health services have improved their systems and processes for paying VMOs. The department is also assisting by reviewing systems at each health service, and by implementing an IT payment system for small rural hospitals.

Increasingly, health services are adopting better practice approaches. All of the audited health services take advantage of the automated checks offered by IT payment systems, and two of the four health services provide VMOs with service sheets, used to generate invoices, to make sure they are accurate. Three of the four health services had adequate audit processes in place.

While there are still gains to be made, particularly by VMOs clearly documenting the services they provide, our testing of a statistically significant sample of VMO payments at each health service found no material errors or evidence of inappropriate VMO billing.

Health services now need to focus on achieving the best possible outcomes through contracted VMO arrangements. Effective contract management requires regular reviewing of whether the contract is properly met, and whether that model continues to best meet the purchaser's needs. None of the audited health services were assessing VMO performance against their contracts, and only one was strategically considering their use of VMOs compared to other employment options. Given the essential nature of medical services, these contracts should be closely managed.

Of greatest concern, however, is the lack of clarity rural and regional health services have about the legal implications of their VMO arrangements. Aspects of VMO arrangements, for example where lump sum payments to VMOs are processed through payroll, and VMOs are given access to salary packaging, imply that they are employees of the health services rather than independent contractors. Recent case law in other sectors, and examples of VMOs in Victoria achieving settlements through claims against health services for employee benefits, demonstrate that this matter does pose a financial risk to health services. Health services need clear advice about the employment status of VMOs and the arrangements needed to meet the definition of that status.

Findings

Contracting visiting medical officers

VMO contracts are consistent; they set out VMO and hospital obligations and payment arrangements, and employ the standard contract template, jointly developed by the Victorian Hospitals Industrial Association and the Australian Medical Association. However, testing a sample of contracts at four health services still found examples of unsigned, out-of-date contracts.

Rural and regional health services need to work more proactively and cooperatively to address their medical staffing needs. Across the four sites there was only limited evidence of analysis of the composition of medical staff, and whether the use of VMOs, rather than formalised salaried arrangements, best met the health services' needs. Competition between health services to secure VMOs also deters information sharing on rates paid, limiting the ability of health services to assure they are getting the best value for public funds.

Whether a VMO's employment status is more akin to an independent contractor or an employee depends on the arrangements in place. For example, factors such as lump sum payments for teaching and training paid through payroll, and salary packaging for VMOs at one audited health service, indicate that the VMO is more likely to be an employee. Health services have no clear legal guidance on either the boundaries between contractor and employee arrangements, or on the employment status of VMOs. This poses a risk to health services if VMOs seek access to employee entitlements, like leave or redundancy, and may raise other legal compliance risks—for example, tax contributions.

Health services do not actively manage their VMO contracts to assure the quality of services purchased with public funds. None of the audited health services include performance monitoring in their VMO contracts, or complete annual performance reviews. Yet, Department of Health policy requires health services to implement annual performance reviews for all senior medical staff, including contracted VMOs, by October 2012. The policy, however, treats contracted VMOs as salaried staff, with instructions, for example, to address professional development. As independent contractors, performance assessment should occur specifically against the contract. While departmental policy should be revised to reflect this, it will still be important for the department to assess health service compliance in undertaking VMO performance assessments.

Paying visiting medical officers

Payments made to VMOs by rural and regional public hospitals are accurate. Health services have adequately responded to recommendations from the multiple reviews at Parliamentary and departmental levels, and Victorian Auditor-General's Office audits, over the past twenty years.

Three of the four audited health services have instituted routine audit processes for VMO payments, and no significant errors were found at any of the four sites on testing of payments. No evidence was found of inappropriate billing by VMOs. VMOs can, however, continue to improve the clarity and comprehensiveness of their documentation of the services provided, to better support payment processes.

Work by the department has, and continues to contribute to these improvements. Its review of VMO payment systems in all rural and regional health services assisted health services to identify and focus on their individual areas for improvement. In addition, a recent project to support small rural health services to access IT payment systems will further enhance payment accuracy in the sector.

Recommendations

That health services:

- assure contracts are signed and current

- proactively review and plan their need for visiting medical officer services

- include performance expectations in visiting medical officer contracts and conduct annual reviews

- obtain advice on visiting medical officer contractor arrangements.

That the Department of Health:

- facilitate the development of guidance on contracted visiting medical officer arrangements, by coordinating relevant stakeholders

- revise the Partnering for Performance policy to clarify performance assessment processes for contracted visiting medical officers and monitor health service compliance.

- That health services complete routine audits of visiting medical officer payments.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Health and the four audited health services with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1. Background

1.1 Introduction

Medical staff employed in the public health system are either salaried medical officers or contracted private practitioners. The latter are referred to as visiting medical officers (VMO). In 2010–11, public hospitals paid in excess of $139 million to VMOs. Over $108 million, or approximately 78 per cent, of this was spent in rural and regional hospitals. Given this expenditure, it is important that health services have sound contracts and effective systems in place to assure that payments to VMOs are accurate and appropriate.

1.2 Visiting medical officers

Health services engage VMOs through fixed contracts on a fee-for-service basis. Fee‑for-service means the health service pays the VMO for each individual medical service provided. Services are generally coded according to the Commonwealth Medical Benefits Schedule. VMOs may also receive a payment for participation in teaching, administration or on-call roster activities.

The health sector uses the term VMO more broadly than the definition above. Historically, the public health sector employed the majority of medical staff as VMOs. Over time, metropolitan Melbourne and large regional health services have converted most VMO positions to fractional salaried positions. The sector, however, still commonly applies the term VMO to these salaried positions. This audit focuses only on contracted VMOs as earlier described.

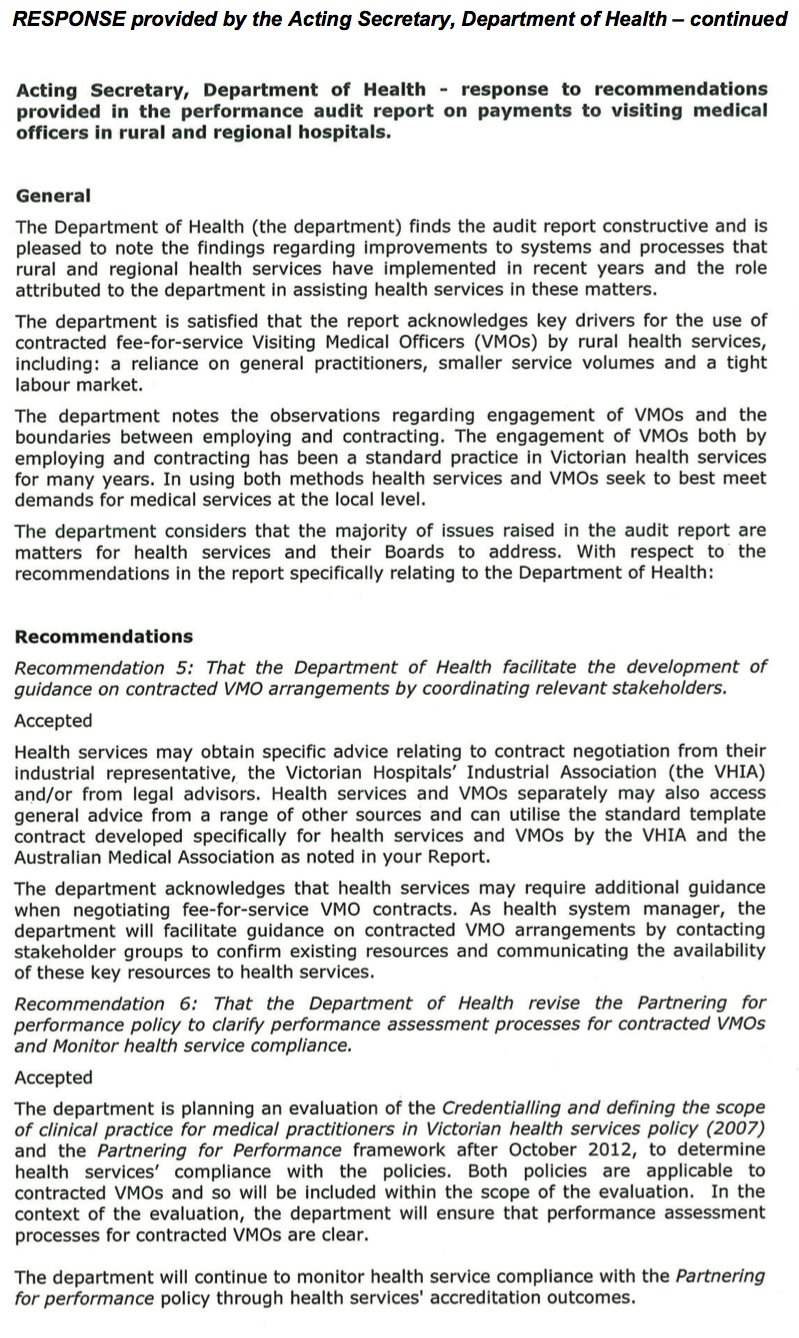

There are relatively few VMOs now in metropolitan Melbourne or large regional public hospitals. However, VMOs remain common in rural and regional health services. Figures 1A shows the percentage of expenditure on VMOs by health service type for 2010–11.

Figure 1A

Percentage of visiting medical officer expenditure by health service type, 2010–11

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Managing visiting medical officer arrangements

The management of VMO arrangements requires health services to have robust systems and processes in place to provide assurance and accountability for funds spent.

Contracts with VMOs should be current and clearly identify expectations and remuneration rates.

Processes for submitting, checking and paying VMO claims should make sure payments are accurate and give health services confidence that payments are for appropriate services. Factors that are important in paying VMO claims include:

- clear and complete claim documentation

- clear and complete medical record documentation, to allow verification of claims

- the use of suitable staff and systems to check and process claims

- data capture that allows audit and review of claims and payments

- the regular audit of payments.

Health services should also review the performance of VMOs against their contract to assure purchased services are properly provided.

1.2.1 Visiting medical officers in rural and regional health services

There are 71 rural and regional health services in Victoria ranging from large regional hospitals with similar services to major metropolitan facilities, through to very small rural health services. A 2010 report commissioned by the Department of Health (the department) found that, at 30 June 2008, 1 630 VMOs were employed across the 71 rural and regional health services on a fee-for-service basis.

Rural and regional health services employ a greater percentage of VMO staff than other health services for a range of reasons. A main factor is that rural and regional health services often rely on local doctors in private practice, for example local general practitioners, to also provide services to the hospital. Other reasons include difficulty attracting staff to a salaried position, not enough work to offer a salaried position, and the preferences of the local workforce or health service.

Rural and regional health services can face challenges in administering and managing VMO arrangements. Smaller administrative staff teams can limit the health services’ capacity to monitor and manage VMO payments and contracts. Rural hospitals are also less likely to have IT systems to streamline claims processing. The department’s report found that, in 2008, of the 71 rural and regional health services, 45 (63 per cent) used manual VMO payment processes. Manual systems increase the administrative burden and likelihood of errors.

1.3 Role of the Department of Health

Under the Health Services Act 1988 (the Act), the secretary of the department has no specific functions concerning the management of VMO arrangements. Contracting and payment of medical staff is the responsibility of individual health service boards.

However, as health system manager, the department has an interest in how effectively health services manage VMO arrangements and has powers under the Act, and through funding agreements, to influence health services.

The Act allows the department to ‘evaluate and review publicly funded or purchased health services’ and to give written, compulsory directions to health service boards. Such directions may relate to:

- ‘the number and type of persons the hospital should employ, or from whom it should obtain services, and their conditions of employment or service’

- ‘the accounts and records that should be kept by the hospital and the returns and other information that should be supplied to the secretary’.

The department has yet to provide any directions to health services concerning VMO arrangements.

However, the department has used its powers to conduct reviews of VMO arrangements in rural and regional health services, and has provided its findings to health services. Since 2003–04, the department has also included a requirement in its conditions for funding that health services establish and maintain appropriate accountability procedures for payments to VMOs.

The 2011–12 policy and funding guidelines allow health services flexibility in the accountability measures they use depending on the size of the health service and the extent of VMO usage. The department suggests that accountability measures include:

- using purpose-specific software to monitor and audit claims

- conducting a regular manual audit of fee-for-service claims and/or

- reviewing guidelines and procedures governing the administration and payment of fee-for-service costs to make sure:

- that contractual agreements are current for all providers who are remunerated on a fee-for-service basis

- that contracts clearly specify applicable rates and conditions of payment

- reviewing trends in service delivery and outputs for patient care provided on a fee-for-service basis.

The policy and funding guidelines also note that the department can require health services to report on the nature and extent of fee-for-service claims, and the accountability measures in place to monitor claims.

1.4 Past audits and inquiries

Payments to VMOs have received ongoing attention from Parliament, government and this office since the mid-1980s. Figure 1B lists these reviews and their focus.

Figure 1B

Reviews of visiting medical officer arrangements

|

Year |

Review title |

Agency |

Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

|

1985 |

Report of the Inquiry into the method of Remuneration for visiting medical staff at Public Hospitals |

Economic and Budget Review Committee (EBRC) |

To determine the most appropriate method of remuneration for visiting medical staff |

|

1993 |

Special Report Number 21: Visiting Medical Officer Arrangements |

Victorian Auditor‑General’s Office (VAGO) |

Examine the administration of VMO arrangements and follow‑up EBRC recommendations |

|

1994 |

Victorian Public Hospitals – Arrangements with Contracted Doctors |

Parliamentary Accounts and Estimates Committee |

Follow-up EBRC and VAGO reviews |

|

1995 |

Ministerial Review of Medical Staffing in Victoria’s Public Hospital System (Lochtenberg report) |

Panel established by the Minister for Health |

Broad review of medical staffing in public hospitals |

|

1996 |

Report on Ministerial Portfolios |

VAGO |

Follow-up of 1993 VAGO audit |

|

2002 |

Report of Public Sector Agencies |

VAGO |

To assess the adequacy of controls associated with VMO arrangements at rural hospitals |

|

2007 |

Ministerial review of Victorian Public Health Medical Staff |

Panel established by the Minister for Health |

To review the recruitment, retention and administration of medical staff in the public sector |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

These reviews have made a number of consistent findings and recommendations, including that:

- health services require better data and documentation to assess and determine VMO payments

- controls in payment processes need improvement

- a more consistent and thorough approach to monitoring VMO payments is needed

- claims information should be better used to assess the appropriateness of services provided by VMOs, including potential inappropriate claiming for private patients treated in public facilities.

1.5 Audit objective, scope and cost

The audit objective is to examine the appropriateness and transparency of payments to VMOs by rural and regional health services including whether:

- contractual arrangements for VMOs are adequate

- health services use robust systems and processes to manage VMO arrangements.

A sample of four rural and regional hospitals were assessed, representing nearly a third of VMO expenditure among the 71 rural and regional health services. The Department of Health’s role as system manager was also examined.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of this audit was $190 000.

2 Contracting visiting medical officers

At a glance

Background

The reliance of rural and regional health services on visiting medical officers (VMO) for the provision of clinical services places significant importance on the appropriateness of these arrangements. Contractual arrangements should be sound and support the best use of public funds and service outcomes for patients.

Conclusion

The audited health services have clear, consistent contracts, which, with minor exceptions, are current. However, health services are not actively managing their VMO arrangements in terms of considering whether the model best meets their needs, or monitoring and managing VMO performance against contracts. Health services also lack the necessary guidance to determine whether their VMO arrangements truly constitute independent contractor, rather than employee arrangements.

Findings

- The audited health services have consistent contracts, which are current with only minor exceptions.

- Rural hospitals do not strategically assess or plan in relation to the use of VMO versus salaried employees.

- Health services are unclear about the employment status of VMOs.

- Rural health services are not monitoring VMO performance.

Recommendations

That health services:

- assure contracts are signed and current

- proactively review and plan their need for VMO services

- include performance expectations in VMO contracts and conduct annual reviews

- obtain advice on VMO contractor arrangements.

That the Department of Health:

- facilitate the development of guidance on contracted VMO arrangements, by coordinating relevant stakeholders

- revise the Partnering for Performance policy to clarify performance assessment processes for VMOs and monitor health service compliance.

2.1 Introduction

Visiting medical officers (VMO) provide services to rural and regional health services under a contractual arrangement. To work effectively, both parties should clearly understand the arrangement, and the health service should seek assurance that it best serves the needs of the health service and its patients. The arrangement therefore, should be underpinned by a clear and comprehensive contract that is current and actively managed by the health service. Such active management includes confirming that the VMO is effectively performing against the contract, and that the independent contractor model is the best option for the health service in obtaining medical services.

2.2 Conclusion

VMO contracts at the audited health services are consistent, clearly delineate service expectations and payments, and demonstrate use of the standard contract template jointly developed by the Victorian Hospitals Industrial Association (VHIA) and the Australian Medical Association (AMA). With minor exceptions, tested contracts were current.

Further opportunities for improvement remain. Health services do not actively manage their VMO contracts to assure the quality of the services they purchase. None of the audited health services include performance monitoring in their VMO contracts or complete annual performance reviews. Department of Health (the department) policy requires health services to implement annual performance reviews for all senior medical staff, including contracted VMOs, by October 2012. It will be important for the department to follow up compliance with this policy.

Rural and regional health services also need to work more proactively and cooperatively to address their medical staffing needs. Only one health service demonstrated documented planning for its medical workforce, including VMOs. The other sites provided no evidence of analysis of medical staff composition, or whether current VMO arrangements best met their needs in obtaining medical services. Competition between health services to secure VMOs also deters information sharing on rates paid, limiting their ability to assure they are getting the best value for public funds.

Whether a VMO's employment status is more akin to an independent contractor or an employee depends on the arrangements in place. For example, factors such as lump sum payments for teaching and training paid through payroll, and salary packaging for VMOs at one audited health service, indicate that the VMO is an employee. Health services have no clear legal guidance on either the boundaries between contractor and employee arrangements, or on the employment status of VMOs. This poses a risk to health services should VMOs seek access to employee entitlements, like accumulated leave or redundancy, and may raise other legal risks, for example tax contributions. The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office is aware that Victorian VMOs have made claims against health services for employee benefits resulting in settlements paid.

2.3 Contracting visiting medical officers

Rural and regional health services contract VMOs, using public funds, to meet their core function—treating patients. The success of this contractual relationship is therefore intrinsic to the effectiveness of the health service, and health services should actively manage these contracts.

2.3.1 Using fee-for-service visiting medical officers

The use of contracted, fee-for-service VMOs by public hospitals has declined since the 1995 Ministerial review of medical staffing in Victoria’s public health system, or the Lochtenberg report. This report recommended the transfer of VMOs to ‘fractional’ or part-time salaried employment. Salaried employment can provide benefits to both parties, with health services gaining cost certainty and greater integration of the doctor into the health service, and doctors gaining access to entitlements such as leave.

However, VMOs are still a dominant feature of rural health services. The reliance of rural health services on general practitioners to provide hospital services is a main driver. Smaller service volumes and a tight labour market limit the ability of rural health services to offer attractive salaried arrangements. However, health services also report that younger doctors are increasingly seeking the security that entitlements such as sick and maternity leave provide.

To respond to changes in the employment market, health services should routinely review their workforce arrangements and plan how best to meet their needs. One of the audited health services developed a business plan in relation to their medical staffing, identifying opportunities for the recruitment of salaried rather than VMO staff. This is proving to be an effective approach, with the health service having successfully transferred individual VMOs to salaried arrangements in two clinical areas. The other three sites did not provide evidence of documented medical workforce plans that assess their use of VMOs. Instead, recruitment of VMOs is considered and managed on an as needs basis. While there are challenges to medical recruitment in rural areas, these health services would benefit from a more proactive and strategic approach to looking at their medical employment models.

2.3.2 Contracts

Content

The contract is the basis for the relationship between the health service and the VMO. It should clearly set out:

- services and activities required of the VMO

- dispute resolution, termination and renewal processes

- insurance arrangements

- right of audit by the hospital

- rules around billing, e.g. concerning public and private patients

- payment rates.

The creation of a VMO contract template by VHIA and the AMA has assisted health services to cover each of these points. VHIA states that the majority of health services use the template with minor changes. This was evident at the four audited health services, whose contracts were consistent with the template, with small variations to suit the health service or medical speciality of the VMO position, e.g. to specify clinical obligations related to the timing of ward rounds or theatre sessions.

Currency

In 2008–09, the department commissioned a review of VMO arrangements in all 71 rural and regional health services. The review found that 39 per cent of contracts needed improvement, with contracts unsigned, out-of-date and/or lacking required information on pay rates. This creates ambiguity in the relationship between the health service and the VMO. We reviewed a sample of 10 VMO appointments at each of the four health services (approximately 20 per cent of the VMO staff at each health service) to check whether a current, complete contract was on file.

Of the 40 appointments reviewed, only one did not have a contract on file, three contracts were unsigned and one had missing information on payment rates. Seven contracts had expired. Lapses in contract coverage often related to protracted negotiations or delays by the VMO in signing the contract.

Negotiations

VMOs contracts generally extend for three to five years. Two of the audited health services use schedules to identify when contracts are coming up for renewal, which assists them to start work early to assure continuity.

The audited health services and the VHIA report variable experiences of contract negotiation. This can be a smooth process where health services and VMOs have worked together to develop and maintain good relations. One of the audited health services had helped achieve this by establishing a VMO Consultative Committee—a sub-committee of the board. The committee provides an opportunity to discuss not only day-to-day matters concerning VMOs and the health service, but also to facilitate understanding of issues and developments within the health service between both parties.

Fee negotiation is a challenge across the audited health services. Health services access advice from VHIA to identify whether rate requests from VMOs are within a reasonable range. The limited medical labour market in rural Victoria, however, creates a competitive environment where specific information on VMO rates is guarded. Fee schedules reviewed in the audited health services show standard rates ranging from 100 to 130 per cent of the Commonwealth Medical Benefits Schedule, with some health services maintaining consistent rates within VMO speciality groups, and others varying rates by individual VMO.

While the labour market clearly influences rates paid, public health services use public funds to pay VMOs and have a responsibility to achieve the best value-for-money. This is difficult without transparent information about pay rates for these public positions.

2.4 Contractor or employee

The employment status of VMOs is unclear. Health services consider VMOs to be independent contractors. The VHIA and AMA contract template and all VMO contracts examined at the audited health services, include the following clause:

‘The Parties hereby agree that this Contract creates the relationship of principal and contractor between them and thereby state that it is not their intention to create the relationship of employer and employee, partnership or any other relationship. The Practitioner agrees that he/she will meet all or any legal obligations, liabilities, and expenses in respect of sick leave, annual leave and long service leave relevant to the Practitioner’.

This clause itself cannot determine the VMO's employment status. Multiple factors contribute to the legal determination of whether a person is an independent contractor or an employee, despite any contractual clause. Getting the relationship right is important because employees are entitled to benefits, including sick and long service leave and redundancy, that independent contractors cannot claim. The Fair Work Act 2009 (Commonwealth) provides for civil remedies where an employer misrepresents employment as independent contracting.

The Victorian Auditor-General’s Office is aware that the financial risk to health services has eventuated. The AMA report that Victorian VMOs have made claims against health services for employee benefits, with these claims being settled, and payments made to VMOs. At April 2012, the AMA advised that they are currently supporting a member in relation to such a claim.

The Federal Court of Australia’s April 2011 decision for On Call Interpreters and Translators Agency versus Commissioner of Taxation (No.3) [2001] FCA 366, is informative. The decision states that, ‘A genuine independent contractor providing personal services will typically be: autonomous rather than subservient in its decision‑making; financially self-reliant rather than economically dependent upon the business of another, and chasing profit (that is a return on risk) rather than simply a payment for time, skill and effort provided’ (at para. 214). Figure 2A lists a range of indicators, referred to in the ruling, for whether a person is an employee or an independent contractor.

Figure 2A

Indicators of employee or contractor relationship

Is the person performing the work an entrepreneur who owns and operates a business?

- Does the person promote their business to the public through advertising and other promotional means?

- Does the person's business engage with multiple purchasers in a repetitive and continuous manner?

- Does the business have tangible assets such as buildings and equipment?

- Do the activities of the business involve the taking of risk in pursuit of profits?

- Does the business employ or engage persons other than the owner/operator to carry out its business activities?

- Is goodwill e.g. name, brand, reputation, being created by the economic activities of the business?

- Does the business have basic business systems e.g. invoicing, financial records, business bank accounts?

- Are the regulatory requirements of a business being met e.g. business name registration and Goods and Service Tax and Australian Business Number registration and compliance.

In performing the work, does the person represent their own business, rather than the purchasing business?

- Does the provision of the economic activity provide an opportunity for profit and a risk of loss?

- To what extent is the reward for the provision of the activity negotiable and negotiated commercially?

- Who controls and directs the manner of the activities being carried out?

- Are the economic activities represented or portrayed as those of the person's business or of the purchasing business?

- Who benefits from the name, brand identification or reputation generated through the economic activity?

- Is the person's business paid for a result, rather than the time they spend on the activity?

- Is the person economically dependent on the purchasing business?

- How integrated is the person's business with the purchasing business?

Source: On Call Interpreters and Translators Agency versus Commissioner of Taxation (No.3) [2011] FCA 366 at paras. 217–220.

For arrangements between health services and VMOs, the answers to many of these questions point to an employer/employee relationship. For example:

- health services have significant control over how VMOs provide services, as is necessary in a healthcare environment

- VMOs are often very integrated into the business, providing teaching and training, and contributing to policy development and recruitment decisions

- the VMO generally represents the health service and their work contributes to the health service's reputation

- the VMO uses health service facilities and equipment

- risk to the VMO is minimal, as they receive insurance coverage for services to public patients, through the department's contract with the Victorian Managed Insurance Agency

- VMOs are prevented from maximising their profits through controls on over‑servicing, as is ethically appropriate.

In addition, health services commonly pay VMOs annual lump sums for activities like teaching and training. These sums, often between $10 000 and $25 000, are paid as salary through payroll, with tax and superannuation applied. Such examples were seen at the audited health services. One of the audited health services also provided VMOs with salary packaging arrangements, which, while not seen at the other three audited sites, is common among rural health services. These features also add to the argument that VMOs more closely resemble employees rather than independent contractors.

Conversely, other aspects of VMO arrangements support their status as independent contractors. Some VMOs, particularly general practitioners, can satisfy indicators showing they have their own business. In a 2006 case, ACT Visiting Medical Officers Association v Australian Industrial Relations Commission [2006] FCAFC 109, the Federal Court decided that four VMOs applying for employee status were not employees as:

- their VMO contracts were integral to their professional practice as a whole

- the doctors performed work for others

- they could delegate work to locums and the health service could not unreasonably withhold approval to do this

- they had no PAYG tax withheld from their payments

- they were not provided with paid holidays or sick leave.

The audited health services have failed to obtain written legal advice on VMO arrangements. Health services need guidance, as current arrangements pose genuine risks if VMOs seek access to employee benefits.

2.5 Monitoring performance

An integral part of any contract arrangement is monitoring performance against the contract. This is especially important for VMO contracts where performance relates to more than just service volume, but also the quality of care provided to patients.

Partnering for Performance

In April 2010, the department released Partnering for Performance, a policy document outlining requirements for performance development and management for senior medical staff. It provides processes and tools to assist in the review of a senior doctor’s performance, including their work achievement and professional behaviours. The department requires all health services to have a process for annual performance reviews for all senior medical staff, by October 2012. Health services may use Partnering for Performance or an equivalent process to fulfil this departmental requirement. The department clearly states that the policy includes contracted VMOs.

Under an independent contractor relationship, VMO monitoring should occur specifically in relation to performance against the contract. Other elements referred to in the policy, such as reviewing professional development, infer an employer/employee relationship. Full application of the policy by health services to VMOs would further strengthen the argument that VMOs are employees.

Nevertheless, from a procurement perspective, health services should assess VMO performance against their contract. None of the audited health services currently undertake routine reviews of VMO performance against their contract and performance review is not included in contracts. Contracts are only reviewed when due for renegotiation and then generally only in terms of fees and working arrangements. Processes for addressing VMO performance are reactive and are triggered only when the health service becomes aware of poor performance, often through informal channels.

Health services report that the main barrier to reviewing VMO performance is that their VMOs report to a single, in some instances, part-time, Director of Medical Services who has limited capacity to complete the reviews. Another identified barrier is that VMOs often have multiple contractors and may be resistant to undergoing multiple reviews.

Regardless of these challenges, health services and VMOs have an obligation to undertake effective reviews to assure public funds are purchasing quality services. Genuine performance assessments will assist to assure VMO contracts are achieving the best possible outcomes for the health service, the VMO and their patients.

Recommendations

That health services:

- assure contracts are signed and current

- proactively review and plan their need for visiting medical officer services

- include performance expectations in visiting medical officer contracts and conduct annual reviews

- obtain advice on visiting medical officer contractor arrangements.

That the Department of Health:

- facilitate the development of guidance on contracted visiting medical officer arrangements, by coordinating relevant stakeholders

- revise the Partnering for Performance policy to clarify performance assessment processes for contracted visiting medical officers and monitor health service compliance.

3 Paying visiting medical officers

At a glance

Background

Payments to visiting medical officers (VMO) have been subject to multiple reviews and Victorian Auditor-General Office audits, over the past twenty years. In 2010–11, rural and regional public hospitals paid over $108 million to contracted VMOs. It is important that these public funds are spent appropriately.

Conclusion

VMO payments by rural and regional public hospitals are accurate. Overall, health services have adequately responded to recommendations from past examinations. The Department of Health (the department) has assisted in achieving these improvements.

Findings

- The department's review of VMO payments in all rural and regional health services has facilitated improvements.

- Rural health services have improved VMO payment systems though require better documentation of services provided by VMOs.

- The department's project to implement IT payments systems for small rural hospitals will help them process VMO payments.

- Only one of the four health services had not instituted routine audits of payments.

- Audit testing found no instances of inappropriate VMO payments.

Recommendation

That health services complete routine audits of VMO payments.

3.1 Introduction

As health services pay visiting medical officers (VMO) on a fee-for-service basis, they need administrative systems to check claims and process these payments. Systems that support accurate and accountable payment are important, as rural and regional health services spend significant amounts on VMO services, $108 million in 2010–11. Health services need payment systems with controls to prevent and detect errors, clear documentation to support payment claims and routine audits to confirm that the systems are working.

3.2 Conclusion

Payments made to VMOs by rural and regional public hospitals are accurate and transparent. Health services have largely responded to recommendations from the multiple reviews at Parliamentary and departmental levels, and Victorian Auditor‑General’s Office audits, over the past twenty years.

Three of the four audited health services have instituted routine and satisfactory audit processes for VMO payments and, on testing of payments, no significant errors were found at any of the four sites. No evidence was found of inappropriate billing by VMOs.

The Department of Health (the department) has, and continues to, contribute to the improvements through its review of VMO payment systems in all rural and regional health services, and a project to support small hospitals to access IT payment systems.

3.3 Paying visiting medical officers

Health services have had the benefit of recommendations from multiple reviews and audits that have identified control gaps and errors in the payment of VMOs. Most recently, the department commissioned a review, over 2008 and 2009, of VMO payments in all health services. While the review found no systemic issues, it did identify examples of insufficient data capture to allow proper checking of VMO claims and payment errors. Each health service received individual feedback from this review.

It is expected that all health services, at this stage, should be able to demonstrate robust payment processes leading to accurate and transparent payments.

3.3.1 Adequacy of systems and controls

Health services need systems and processes in place to prevent VMO payment errors. Important elements of a VMO payment system include:

- clear documentation of VMO services provided and claimed for

- manual and automated checks to prevent payment errors

- routine auditing of payments.

Documentation and invoicing

A fee-for-service payment system relies on accurate identification of services provided in order to make the right payment. Two different invoicing systems were in place at the four audited health services.

Two of the health services demonstrated better practice by using standard ‘billing’ or ‘service’ sheets to create the VMO’s invoice. Service sheets are forms kept in the patient record that support consistent capture of the clinical and patient information, including the fee schedule item codes needed to generate an accurate invoice. The health service then uses the sheets to create the invoice, known as a ‘Recipient Created Tax Invoice’, which the VMO confirms. In a 2006 letter, the department recommended this method to all health services. Despite this recommendation, two of the audited health services still allow VMOs to submit their own invoices. This risks VMOs providing invoices with missing information, thus increasing administration and the chance of payment errors.

Good clinical documentation is necessary for more fundamental reasons than accurate VMO payments. It is essential to allow communication between multidisciplinary health teams and support best possible patient care. However, the clinical record does have a valuable role in assuring accurate VMO payments by providing source information from which to check the accuracy and appropriateness of VMO invoices or payments.

To support good clinical documentation, all of the audited health services provide clear instruction and guidance to VMOs regarding expectations for documentation, through requirements in their contracts and medical documentation policies.

Processing payments

All of the audited health services demonstrated sufficient systems controls for processing VMO payments.

One of the health services demonstrated better practice by having a policy to outline their VMO payment processes, providing clear instructions to staff, and promoting consistent practice.

All of the audited health services use IT systems to facilitate VMO payments. Specialist medical payment IT systems assist accurate payments by providing controls over who can access the system, blocking or warning against entries that contravene business rules, and providing reporting functions. Each of the audited health services was using IT system controls, including automated checking of claim dates against patient admission dates and blocks or warnings to prevent staff from entering duplicate item codes or claims for patients who were not admitted publicly.

The 2008–09 review commissioned by the department found that only 37 per cent of the 71 rural and regional health services were using IT systems for VMO payments. Cost and a lack of critical mass present a barrier to some smaller health services implementing IT payment systems. To address this, in June 2011, the department provided $160 000 for a project to implement a shared IT payment system across small rural health services in the Barwon South West Region. Testing was due to commence in April 2012, with project completion due April 2013.

In addition to IT system controls, all of the audited health services undertake some form of manual checking of VMO claims as they are processed. For example, clerical staff checking for duplicate item numbers, and the Director of Medical Services checking the ‘reasonableness’ of claims, e.g. that the amount is not unusual.

Auditing visiting medical officer payments

Within annual policy and funding guidelines, the department requires ‘health services that have engaged medical practitioners on a fee-for-service basis’ to ‘establish and maintain appropriate accountability procedures over these payments’. The department suggests regular audit of fee-for-service claims as an appropriate accountability measure.

Three of the four audited health services undertake auditing of VMO payments.

One of the health services demonstrated better practice. They have a policy to communicate and guide their audit approach for VMO claims, and a rotating audit program where they audit at least two VMOs each month and all VMOs at least once a year. The audit program additionally targets atypical accounts and VMOs with prior billing errors. This health service also commissioned an external audit in November 2011, which found nothing to suggest payment processes were inadequate, and only detected minor payment errors.

Another health service has a clerk audit 20 payments each week and refers any exceptions to the Director of Medical Services for review.

In November 2011, a third health service began analysing three years of data from the Victorian Admitted Episode Database, which holds patient admission data; their VMO payment IT system; and their operating theatre data, to look for claim discrepancies. This project is not yet complete and the health service plans to repeat the exercise yearly. This is an example of an automated audit system that could be used by smaller health services that have limited capacity to complete routine manual audits.

One of the health services does not audit VMO payments. The health service acknowledges this gap but does not have immediate plans to address it. The department could assist with the establishment of ‘appropriate accountability procedures’ over VMO payments by making routine audits a requirement, rather than a suggestion, within the policy and funding guidelines.

3.4 Outcomes of testing

Across the four audited health services, we tested a random sample of 46 VMO payments at each site, allowing a 95 per cent confidence level. Appendix A includes further information about the testing methods. The test checked that:

- claim dates matched patient admission

- the patient was publicly admitted

- claimed services were identifiable in the patient record

- multiple procedures were correctly claimed

- item code prices on payments, invoices and fee schedules matched

- consultations claimed on the day of surgery were appropriate

- item codes claimed were consistent with acceptable clinical practice.

The testing found that VMO payments were appropriate across all four sites. Figure 3A shows the findings at each audited health service.

Figure 3A

Outcomes from visiting medical officer payment test at health services 1–4

|

Test |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Claimed item code matches to a patient and medical record |

46 |

46 |

46 |

46 |

|

The date of the claim is within the admission/discharge dates |

46 |

46 |

46 |

46 |

|

The patient is classified as a public patient |

46 |

46 |

46 |

46 |

|

The paid item code matches the item code documented in the VMO service or billing sheet/invoice |

46 |

13 |

46 |

46 |

|

The paid item code price matches the claimed item code price |

46 |

45(a) |

46 |

45 |

|

Item codes not claimed for consultations on the same day as an elective surgery procedure(b) |

46 |

46 |

46 |

46 |

|

Item code claimed is in accordance with acceptable practice(c) |

43 |

46 |

44 |

43 |

(a) One error detected with an item not included on the invoice.

(b) This test relates to appropriate practice – a surgeon would not usually have a consultation with a patient on the day of surgery.

(c) A medical doctor reviewed VMO claims and payments against medical records to check for any claims inconsistent with accepted medical practice.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

One area for improvement identified through the testing concerns the completeness and legibility of documentation by VMOs to allow accurate checking of services rendered. Of the total 184 payments tested, eight payments could not be verified regarding the appropriateness of the claim in relation to acceptable medical practice. This was due to gaps in medical record documentation. For health service 2, 33 payments in the sample could not be matched to an item code in the VMO service sheet. This was because the VMOs had recorded ‘consultation’ as an item. However, there are various item codes for different consultations, e.g. during or after hours. While the health service can infer the appropriate code where information on consultation timing and duration is documented, VMO recording of the specific item code is better practice.

As discussed in section 3.3.1, service sheets within patient records that promote clear documentation of services and item codes, especially for anaesthetics due to the complexity of the fee structure for this service, assist in addressing this problem.

Another barrier to auditing VMO claims concerns documentation of fee schedules agreed for individual VMOs. In some cases, health services had not clearly documented changes to fee schedules, which hinders the accurate matching of claims against agreed fees.

Recommendation

- That health services complete routine audits of visiting medical officer payments.

Appendix A. Testing methods

Contract sampling and testing

A judgemental sampling approach was used to select our sample of ten contracts for testing at each health service. Visiting medical officer (VMO) listings for the period ending 30 June 2011 contained on average 50 VMOs per site, therefore we ensured approximately 20 per cent coverage across the VMO population for each hospital.

The judgemental sampling approach was chosen to ensure a representative selection covering a range of variables, including:

- medical speciality

- whether the VMO was contracted to undertake ‘higher duties’

- type of contract template used

- type of payment type (i.e. VMO paid via accounts payable, payroll or a combination of both).

We did not select our sample and provide it to the health service prior to the visit. We requested access to all VMO contracts while on site, and selected our sample during the visit.

For each of the sampled contracts, we undertook the following tests:

- Did the contract exist on the VMO file?

- Was the contract current for the period of examination, i.e. 2010–11?

- Was the contract signed by the VMO and the health service representative?

- Did the contract contain clear, agreed remuneration rates for the period of examination, including the nature of after-hours payments?

- Did the contract contain clear obligations and responsibilities of the VMO?

- Did the contract contain other allowances/provisions (such as meeting attendance, reimbursement of travel, coverage of insurances)?

Visiting medical officer payment sampling and testing

For each health service the total number of VMO payments in the 2010–11 financial year exceeded 1 000. Based on a 95 per cent confidence level and 2 per cent error rate, a sample size of 46 payments at each health service was sufficient. The sample was then randomly selected using a random numbers generator.

The following data and information sources were utilised to conduct testing of the VMO payment samples:

- IT payments systems and VMO listings at each health service

- theatre IT systems

- accounts payable extracts

- Victorian Admitted Episode Dataset, 2010–11 data

- Victorian Emergency Minimum Dataset, 2010–11 data

- Commonwealth Medical Benefits Schedules 2008–11

- VMO contracts and fee schedules

- VMO service sheets and patient medical records.

The following tests were applied to the sampled VMO payments:

- Did claim dates match patient admission dates?

- Was the patient publicly admitted?

- Were claimed services identifiable in the VMO service sheets/patient record?

- Were multiple procedures correctly claimed?

- Did item code prices on payments, invoices and fee schedules match?

- Were consultations inappropriately claimed on the day of surgery?

- Were claimed item codes consistent with acceptable clinical practice?

The audit team included a qualified doctor/medical administrator.

IT payment system testing

At each health service, the following tests were conducted on IT systems used for processing VMO payments:

- Can you enter a duplicate item without an automated warning?

- Can you enter an item for a date outside the patient admission without an automated warning?

- Does the system correctly calculate fees for multiple procedures, e.g. where a second procedure attracts a percentage payment of the first?

- Can you allocate an item number and generate a payment for a private patient?

Appendix B. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Health and the four audited health services with a request for submissions or comments.

The submission and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.