Personnel Security: Due Diligence over Public Service Employees

Overview

In this audit, we examined personnel security measures at all eight government departments, and the Victorian Public Service Commission. We specifically assessed agencies’ employment screening practices and how they are managing conflict of interest risks during recruitment.

Transmittal letter

Independent assurance report to Parliament

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2020

PP No 130, Session 2018–20

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Personnel Security: Due Diligence over Public Service Employees.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

21 May 2020

Acronyms

Acronyms

| ACIC | Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission |

| COI | conflict of interest |

| DELWP | Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| DJCS | Department of Justice and Community Safety |

| DJPR | Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions |

| DoT | Department of Transport |

| DPC | Department of Premier and Cabinet |

| DTF | Department of Treasury and Finance |

| HCM | Human Capital Management |

| IBAC | Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission |

| PAS | professional advisory services |

| PROV | Public Record Office Victoria |

| SPC | state purchase contract |

| SS | staffing services |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VDP | voluntary departure package |

| VPS | Victorian public service |

| VPSC | Victorian Public Sector Commission |

| VO | Victorian Ombudsman |

| VSB | Victorian Secretaries Board |

| WoVG | whole of Victorian Government |

| WWCC | Working with Children Check |

Abbreviations

| the Standard | Australian Standard 4811—2006 Employment screening |

Audit overview

The Victorian public service (VPS) relies on employees, contractors and consultants who are appropriately qualified, competent and act in the public interest.

To achieve this, VPS agencies and departments must have effective personnel security measures, including employment screening. If properly implemented, these measures help to control fraud and corruption risks during recruitment and maintain the integrity of the VPS.

This audit examined personnel security and conflict of interest (COI) measures at all eight government departments and the Victorian Public Sector Commission (VPSC) and undertook detailed file reviews at three agencies—the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) and the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF).

Our audit objective was to determine whether fraud and corruption controls regarding personnel security are well-designed and operating as intended at the audited agencies.

Conclusion

Government agencies have well-designed policies and procedures that operate to minimise the risk of recruiting unsuitable employees from outside the VPS, and from hiring a former VPS employee with an undisclosed history of misconduct. However, the same controls are not in place for contractors or consultants, nor are they operating effectively for candidates who are existing VPS employees.

There are also gaps in how agencies identify and reduce the risk of conflicts of interest during recruitment.

These weaknesses unnecessarily expose the VPS to fraud and corruption risks and increase the risk that unsuitable individuals may work in the VPS.

VPSC’s pre-employment screening policy is a positive first step towards a consistent, better practice approach to employment screening in the VPS. However, the policy does not cover all key employment screening activities and VPSC has not integrated its other guidance material to provide comprehensive instruction for agencies on employment screening.

Findings

Screening VPS employees

VPS-wide pre-employment screening policy

In December 2019, VPSC released its VPS Pre-employment Screening Policy, combining two previous versions. The policy sets a minimum standard for pre employment screening in the VPS.

The policy is a positive step towards achieving a consistent approach to employment screening that aligns with better practice. However, it primarily focuses on a candidate’s misconduct history, and does not cover all aspects of employment screening. VPSC publishes additional guidance on some aspects of employment screening, such as police and reference checks, but these do not provide a consolidated source of guidance for hiring agencies that is fully consistent with Australian Standard 4811—2006 Employment screening (the Standard).

We acknowledge VPSC’s ongoing work with agencies to review and improve the policy.

Police checks

National police checks identify a candidate’s criminal history, which in Victoria includes both findings of guilt and charges. Police checks provide critical information about a candidate’s suitability for work in the VPS.

All audited agencies have policies and processes that are adequate for completing criminal history checks for candidates new to the agency (external candidates), which includes confirming their identity.

However, no audited agency periodically rechecks the criminal history of existing employees to assess ongoing suitability for their role. Only the Department of Education and Training (DET) requires a mandatory police check for candidates who are existing employees (internal candidates) and the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS) requires a mandatory police check for employees working directly with offenders. This means the ongoing suitability of VPS employees, who may have access to sensitive information or work in high-risk roles supporting vulnerable people, is not checked. This practice is not consistent with the Standard, which recommends a risk-based approach to employment screening for both external and internal candidates.

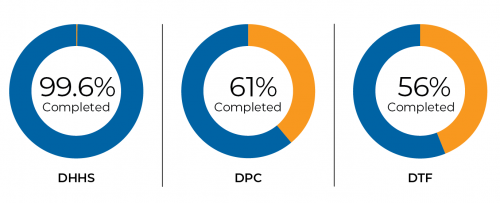

Compliance with police checks

We examined whether DHHS, DPC and DTF completed police checks of external candidates in 2017–18 and 2018–19. Figure A shows high levels of compliance across all three departments.

Figure A

Police check compliance rates, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019

Note: See Appendix B Data analysis methodology for details.

Source: VAGO.

Candidates with a criminal history

Agencies do not automatically exclude candidates with a criminal history. While we found some inconsistency in practices, all agencies had fair and thorough processes for assessing a candidate’s criminal history. Agencies provide the candidate with an opportunity to respond to the police check outcome, and appropriately assess the risk the past criminal conduct may pose to the agency and the services it provides.

We examined the assessment processes at DHHS, DPC and DTF and found the agencies hired 66 per cent (19 of 29) of the candidates with a criminal history. All three agencies have well-designed processes for assessing a candidate with a criminal history, although DHHS’s poor record keeping practices meant we could not verify if staff conducted thorough assessments in 35 per cent (6 of 17) of the files we reviewed.

Reference checks

Reference checking is a longstanding, fundamental requirement for all VPS recruitment. It confirms a candidate’s employment history and past performance and conduct.

All agencies have policies and procedures that require mandatory reference checks for external candidates. They provide clear instructions and templates for hiring managers to conduct reference checks.

However, not all agencies include specific questions about candidates’ past misconduct and performance concerns.

Agencies also are not consistently conducting reference checks for internal candidates:

- DHHS and DJCS have policies and procedures that require two mandatory reference checks.

- DTF and VPSC require one reference check.

- Other agencies have limited or no documented guidance in relation to internal candidates.

These gaps mean that hiring managers may not have all the relevant information to assess a candidate’s suitability.

Compliance with reference checks for external candidates

We examined whether DHHS, DPC and DTF completed the two mandatory reference checks for external candidates in 2017–18 and 2018–19 and found that compliance varied across the three departments, as shown in Figure B.

Figure B

Completion of reference checks (external candidates), 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019

Note: Reference checks that were marked as complete in the selection report, but had no evidence attached were considered as incomplete.

Note: See Appendix B Data analysis methodology for details.

Source: VAGO.

The low compliance rates were likely caused by poor record keeping practices rather than the reference checks not being done. We found that:

- DHHS's and DPC’s selection report templates instruct hiring managers to attach reference checks, but this is not being done consistently.

- DPC instructs hiring managers to keep records of reference checks but does not specify how or where to keep them.

Screening misconduct history

Agencies need accurate information about a candidate's past conduct, including any involvement in misconduct, to make sure they recruit suitable candidates.

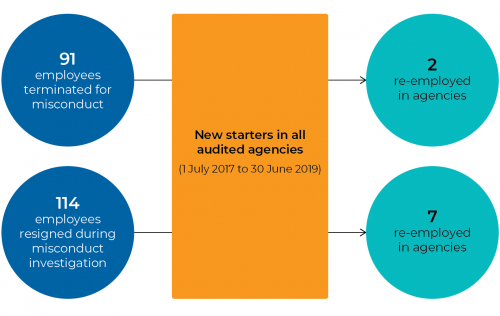

We used agencies' misconduct and payroll data to determine whether VPS staff with misconduct histories are being re-employed in the VPS. This involved:

- identifying employees that had been terminated for misconduct or resigned during a misconduct investigation between 1 July 2015 and 30 June 2019

- comparing this to payroll data to determine if they were re-employed in agencies between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2019.

Only 4 per cent (9 of 205) of the VPS employees that were terminated for misconduct, or resigned during a misconduct investigation, were re-employed in the agencies. This indicates that controls are working to minimise the risk of employing candidates with potentially unsuitable misconduct histories.

COI policies and procedures

All agencies have COI policies that acknowledge recruitment as a high-risk activity. However, this had not led to effective recruitment policies and procedures that control the risk of COI.

All agencies, aside from the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning (DELWP), DJCS and VPSC, do not have thorough processes to ensure selection panels identify, declare and manage COI during short listing. Rather, they consider COI at the end of the recruitment phase, which is too late. We also found that the level of instruction and training for hiring managers on COI risks during recruitment varies, and in some instances does not exist.

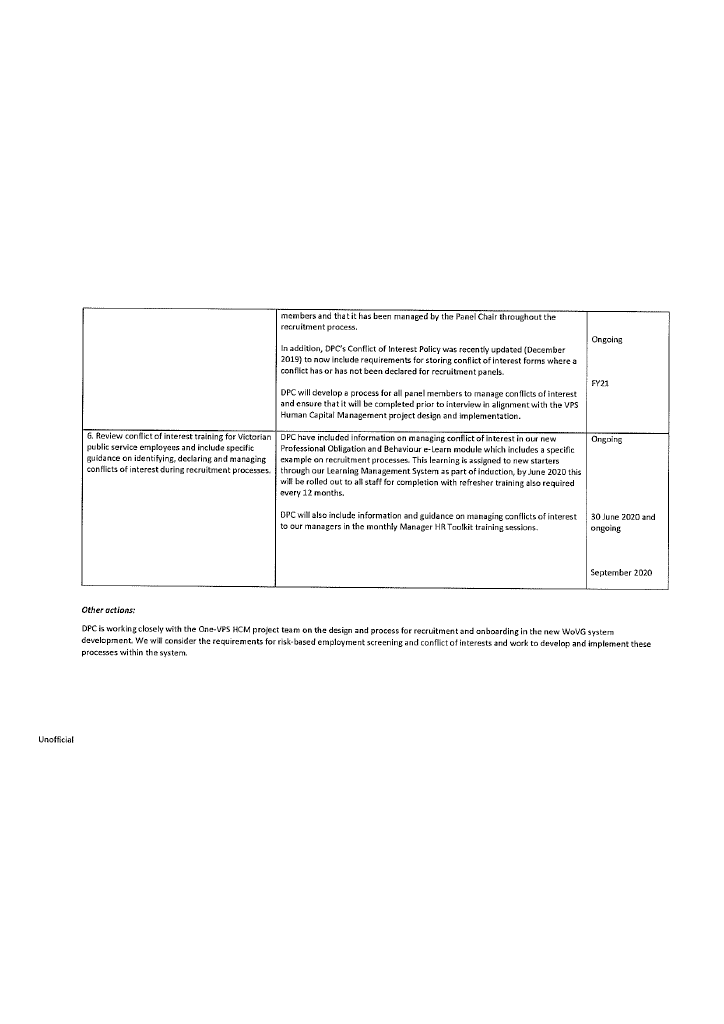

During the audit, DPC and DHHS reviewed and improved their COI processes for recruitment. DPC now requires the selection panel chairperson to document that COI have been declared and managed throughout the recruitment process. DHHS improved its instructions to hiring managers emphasising the requirement to declare COI early in the recruitment process.

Screening contractors and consultants

Government agencies can engage contractors and consultants by using whole of Victorian Government (WoVG) purchasing agreements, or by using their own procurement processes.

|

Consultants are engaged primarily to provide expert analysis or advice. Contractors provide works or services but are not directly employed by the agency. WoVG purchasing agreements include state purchase contracts and supplier registers. They aim to provide common goods and services to departments at a lower price and standardise the way the government buys from suppliers. |

We examined the following three WoVG agreements:

- staffing services state purchase contract (SPC)

- professional advisory services SPC

- eServices register.

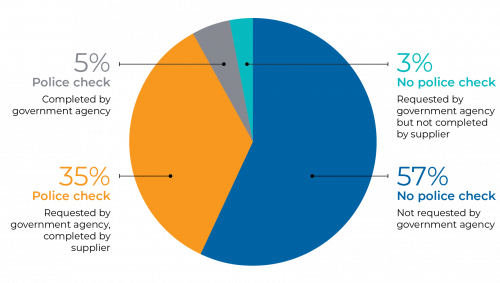

These agreements include broad obligations for suppliers to provide suitable staff, but no specific obligations to conduct basic screening. For example, all audited agencies conduct police checks for new employees, but there is no mandatory requirement for contractors or consultants who may be filling a similar role. Instead, government agencies must specifically request any screening for each contractor or consultant engagement.

This approach is not working. We examined a sample of 299 staffing services SPC engagements from 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019 and found that 60 per cent did not have a police check. Our analysis showed that during this period, up to 3 430 contractors worked in the VPS without being checked for a criminal history.

We also found that the audited agencies do not fully understand their obligation to request screening for each contractor or consultant. The current guidance and templates, both for WoVG agreements and direct procurement processes, do not clearly instruct and prompt hiring managers to consider what screening is required for consultants and contractors.

Record keeping

We found that agencies’ record keeping policies and practices for employment screening are inconsistent and not always compliant with the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) standards. Many agencies use a combination of the VPS online recruitment system and their own record management systems, spreadsheets and paper files.

This creates the risk that agencies cannot find an employment screening record that demonstrates a candidate’s suitability. If a recruitment decision is challenged, agencies would not be able to provide evidence to support their decision.

In particular, ineffective record keeping practices at DHHS, DPC and DTF meant that they could not locate copies of reference checks and therefore could not be sure that they were done.

This emphasises the importance of the proposed VPS-wide Human Capital Management (HCM) project, which aims to implement a single system for recording all information for recruitment processes across the VPS, including employment screening.

A consistent VPS human resources system

In January 2019, the Victorian Government launched the One VPS initiative, designed to make it easier for the VPS to work together. One VPS was responsible for the development of the HCM system, a shared human resources system for all eight government departments and Victoria Police. On Friday 1 May 2020, the government announced One VPS would cease, but the Enterprise Services Branch in DPC would continue to oversee the HCM project.

The HCM project team is in the design phase, with implementation planned to start in 2020–21, initially at the Department of Transport (DoT). Previously, One VPS and VPSC co-chaired the project steering committee and DPC intends to continue this arrangement, which is important to ensure the success of the HCM project.

There is considerable work for agencies and the project team to understand the HCM's potential risks and benefits. If it is successfully implemented as a single source of information on VPS employees’ work history, it has the potential to reduce ineffective record keeping practices and improve the effectiveness of employment screening in the VPS.

Recommendations

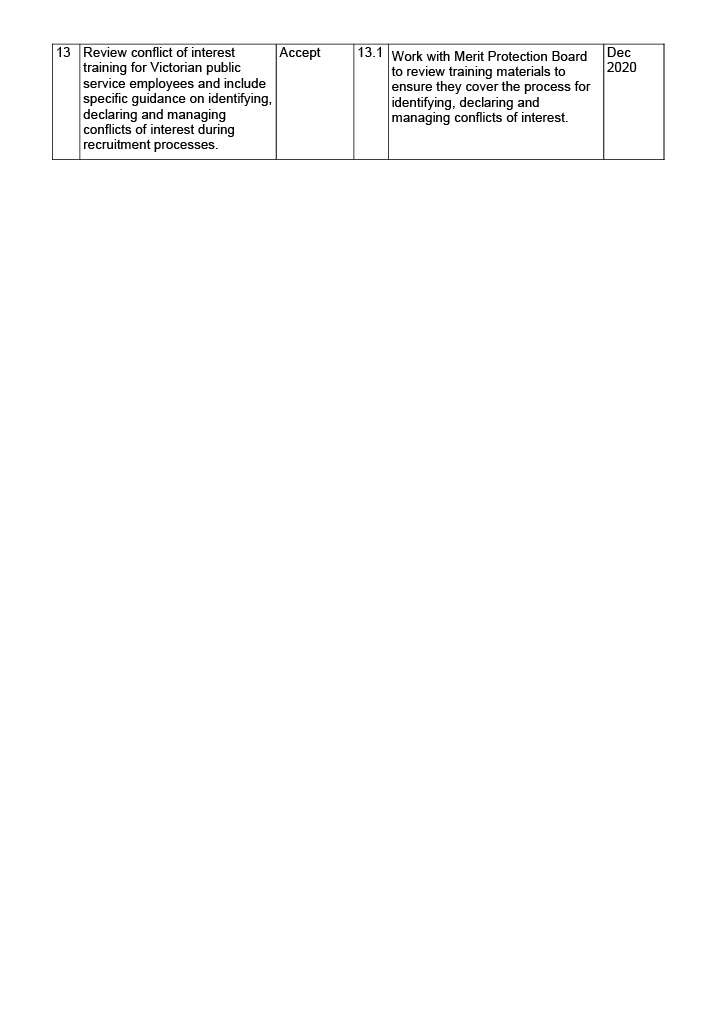

Our 13 recommendations fall under five key topics, with specific recommendations for VPSC, DPC and DTF, as well as recommendations that apply to all audited agencies.

We recommend that the Victorian Public Sector Commission:

1. Update, and consolidate into a single location, the Victorian public service pre employment screening policy and other guidance on employment screening, which aligns with Australian Standard 4811—2006 Employment screening.The policy and guidance material must provide clear instruction for agencies on risk based employment screening practices, which allow for variation in agencies’ workforce risk profiles. The policy and guidance should cover all aspects of employment screening, including but not limited to:

- police checks

- reference checks

- eligibility to work checks

- qualifications check

- role-specific checks (see Section 2.4)

2. Update the Victorian public service pre-employment screening policy to provide clear guidance on employment screening requirements for candidates who are existing Victorian public service employees (see Section 2.4).

3. Review and update recruitment guidelines and toolkits to ensure that all recruitment guidance material incorporates employment screening and conflicts of interest (see Section 2.4).

4. Continue to work with the Human Capital Management project team to ensure that the system incorporates Victorian public service-wide employment screening practices (see Section 2.5).

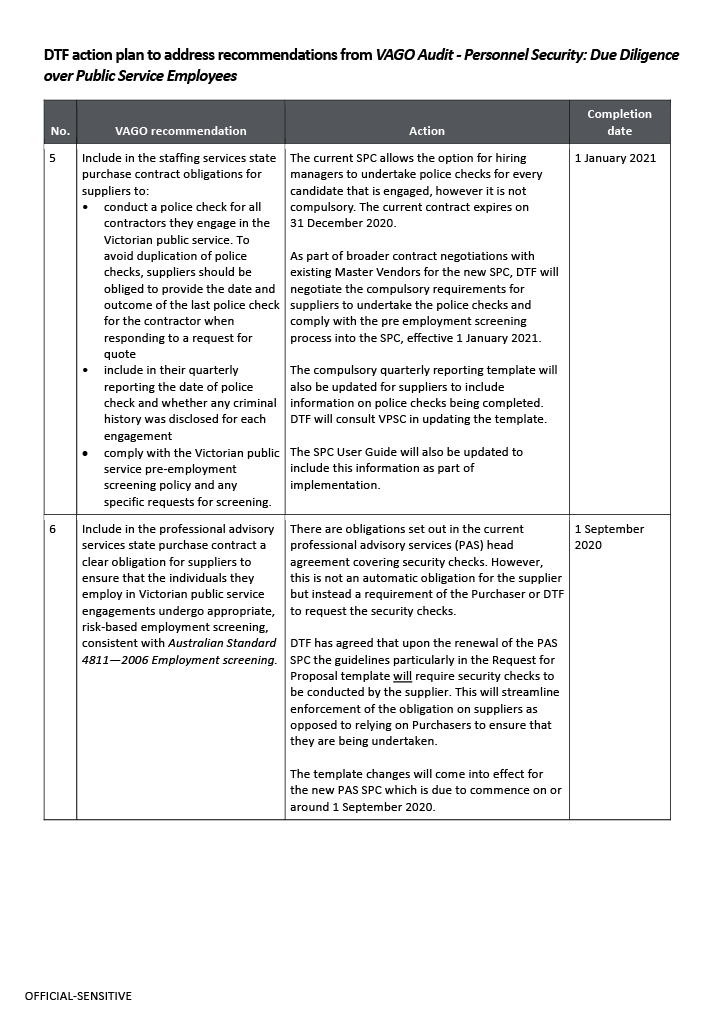

We recommend that the Department of Treasury and Finance:

5. Include in the staffing services state purchase contract obligations for suppliers to:

- conduct a police check for all contractors they engage in the Victorian public service. To avoid duplication of police checks, suppliers should be obliged to provide the date and outcome of the last police check for the contractor when responding to a request for quote

- include in their quarterly reporting the date of police check and confirm their suitability for the engagement

- comply with the Victorian public service pre-employment screening policy and any specific requests for screening (see Sections 3.3, 3.4 and 3.6)

6. Include in the professional advisory services state purchase contract a clear obligation for suppliers to ensure that the individuals they employ in Victorian public service engagements undergo appropriate, risk-based employment screening, consistent with Australian Standard 4811—2006 Employment screening (see Section 3.3).

7. Review and improve the user guides and templates for the staffing services agreement and professional advisory services agreement to:

- ensure they clearly define the contractual obligations for suppliers and government agencies in relation to screening contractors or consultants

- prompt hiring managers to document specific screening requirements based on the risk of the contractor/consultant role at the start of the procurement process

- require suppliers to document the screening completed prior to the engagement starting (see Section 3.5).

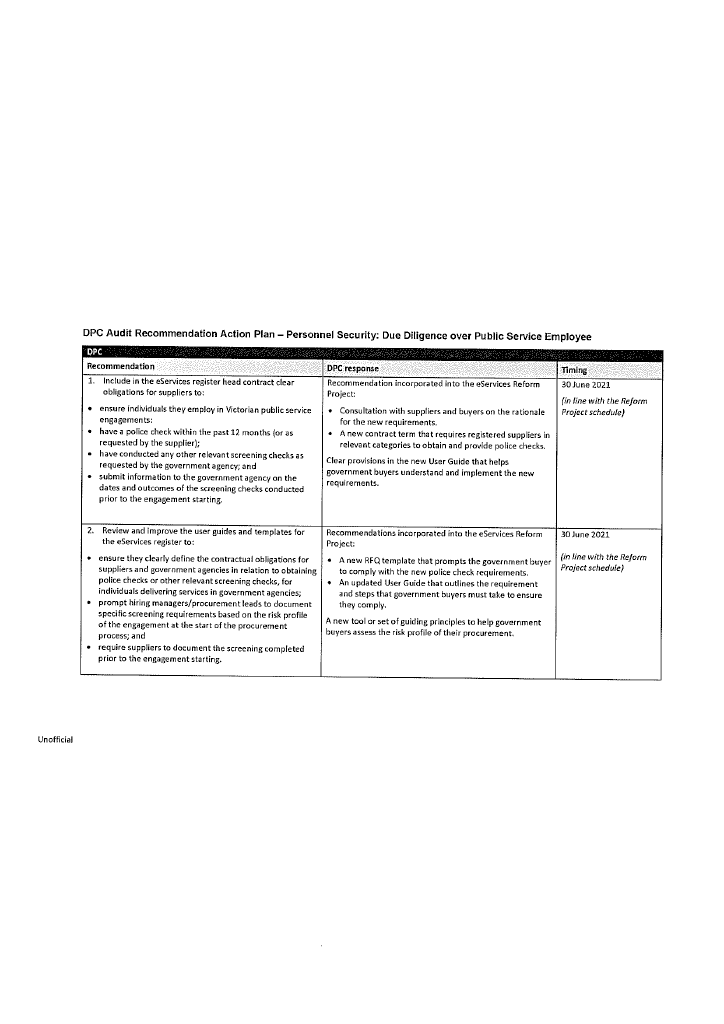

We recommend that the Department of Premier and Cabinet:

8. Include in the eServices register head contract clear obligations for suppliers to:

- ensure individuals they employ in Victorian public service engagements:

- have a police check within the past 12 months (or as requested by the government agency)

- have conducted any other relevant screening checks as requested by the government agency

- submit information to the government agency on the dates and outcomes of the screening checks conducted prior to the engagement starting (see Section 3.3).

9. Review and improve the user guides and templates for the eServices register to:

- ensure they clearly define the contractual obligations for suppliers and government agencies in relation to obtaining police checks or other relevant screening checks, for individuals delivering services in government agencies

- prompt hiring managers/procurement leads to document specific screening requirements based on the risk profile of the engagement at the start of the procurement process

- require suppliers to document the screening completed prior to the engagement starting (see Section 3.5).

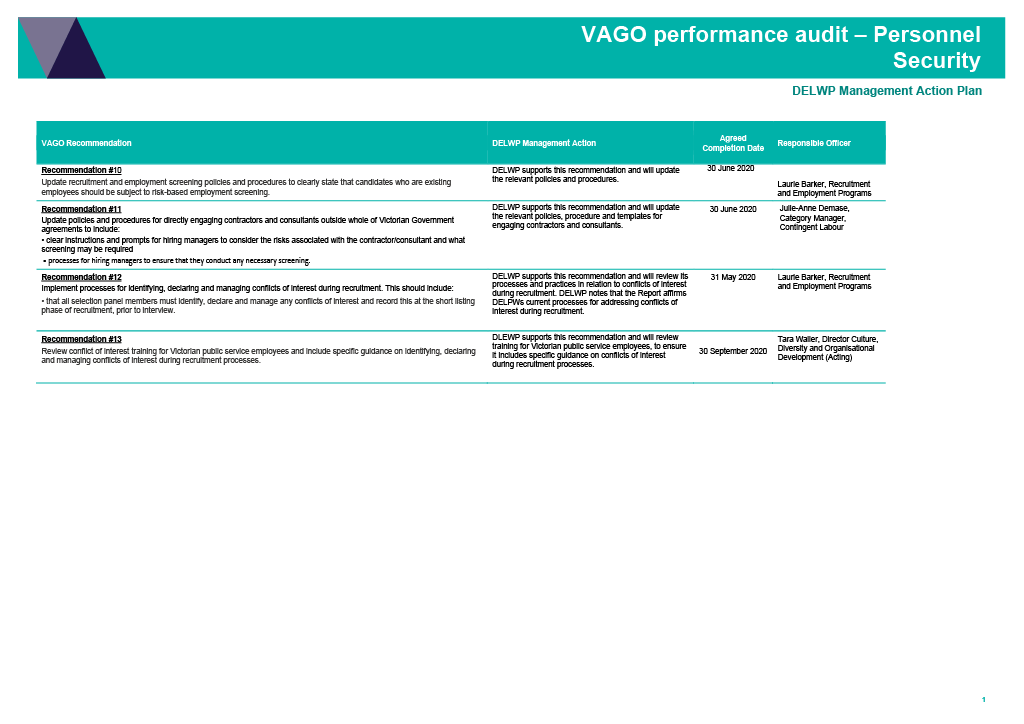

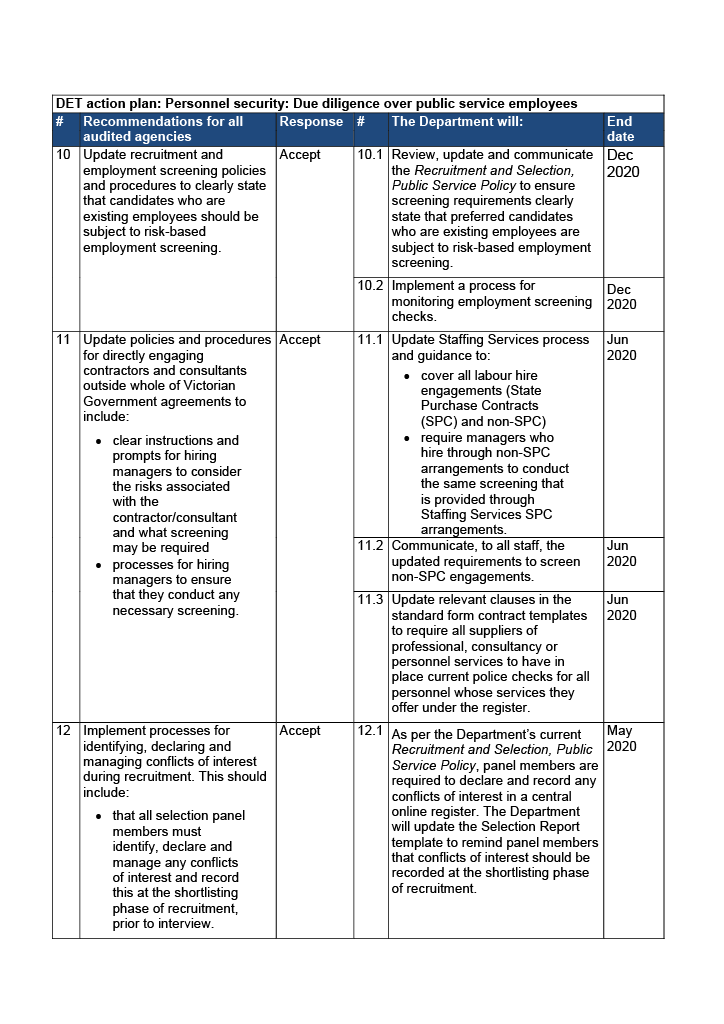

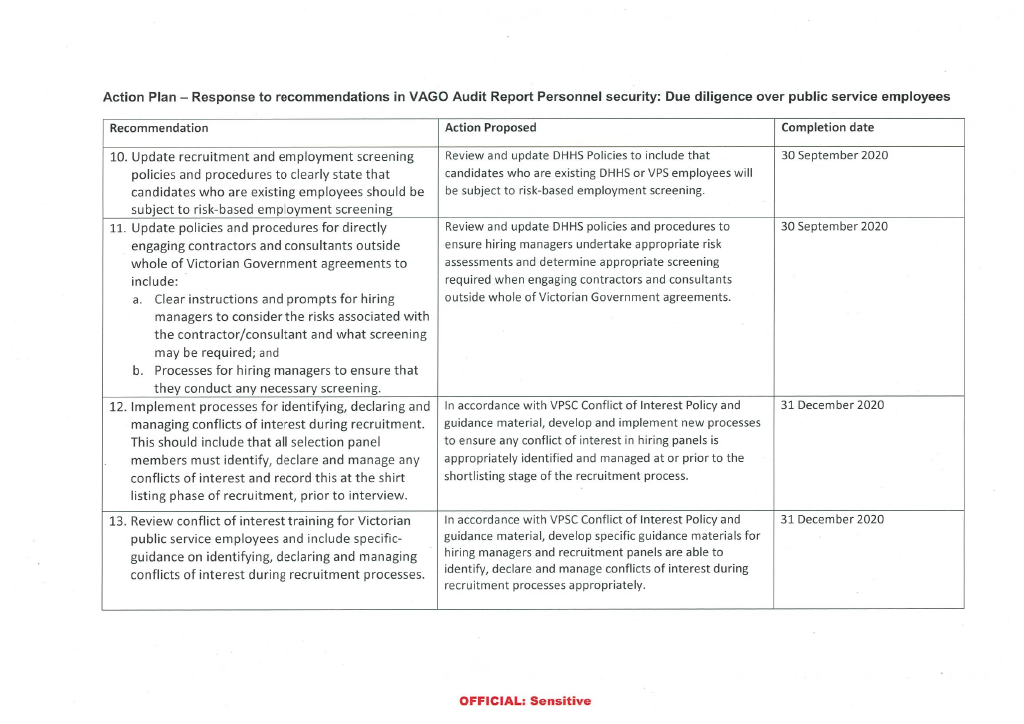

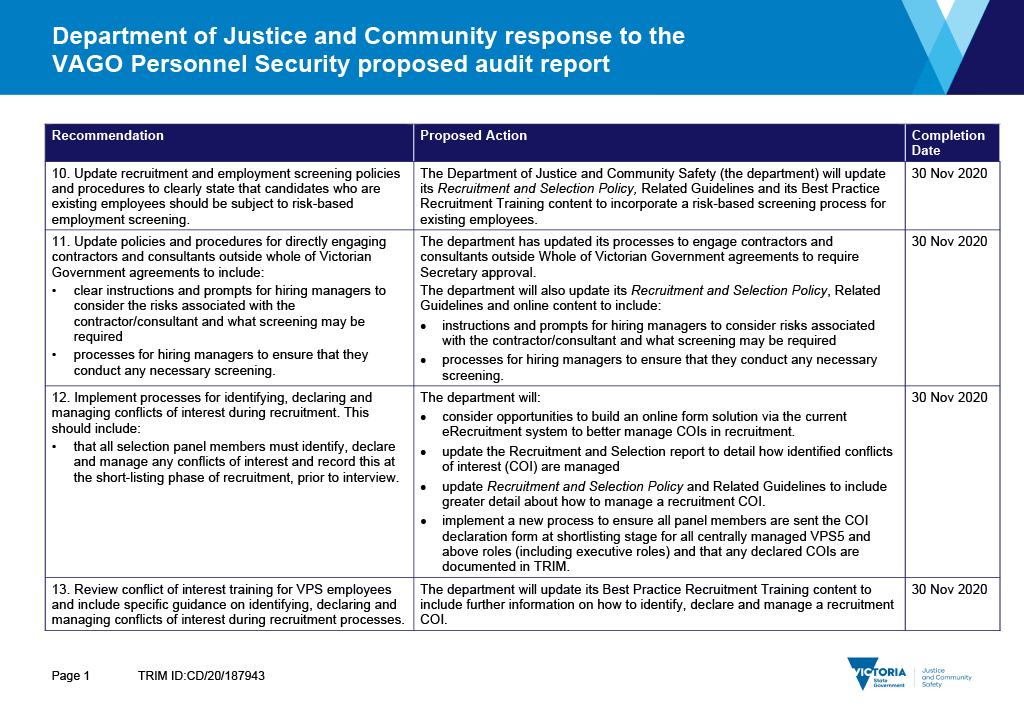

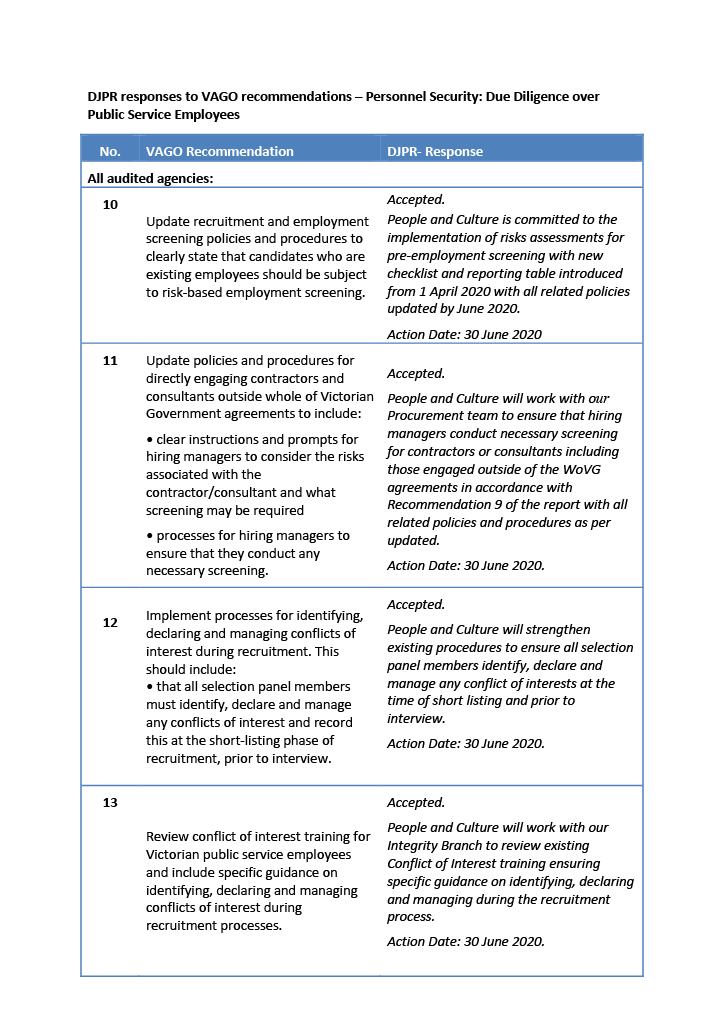

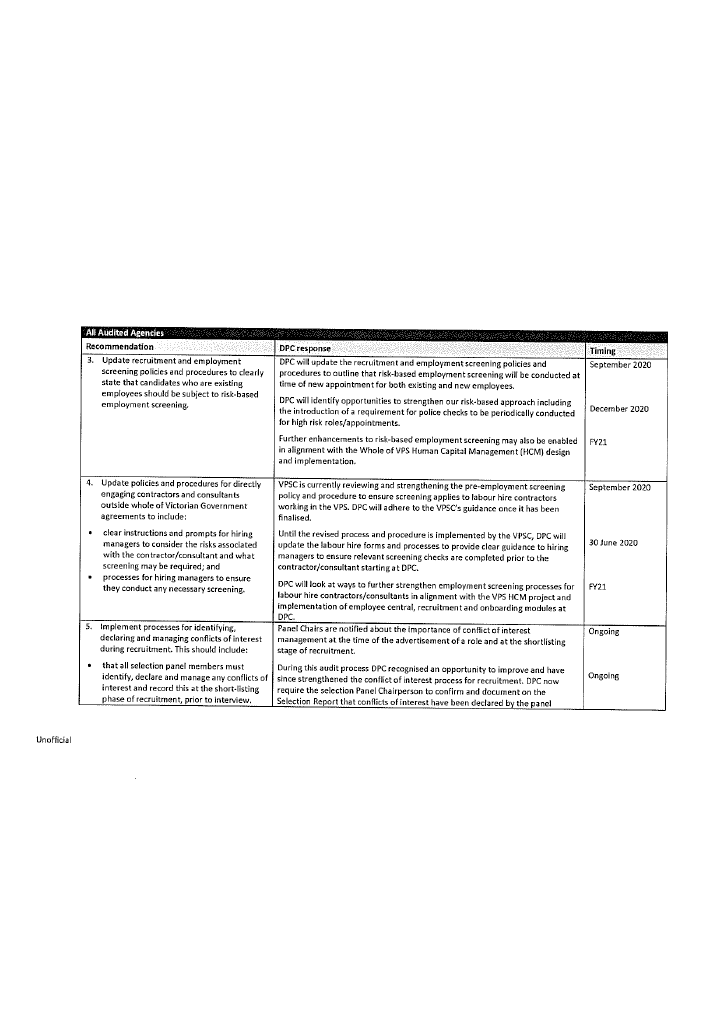

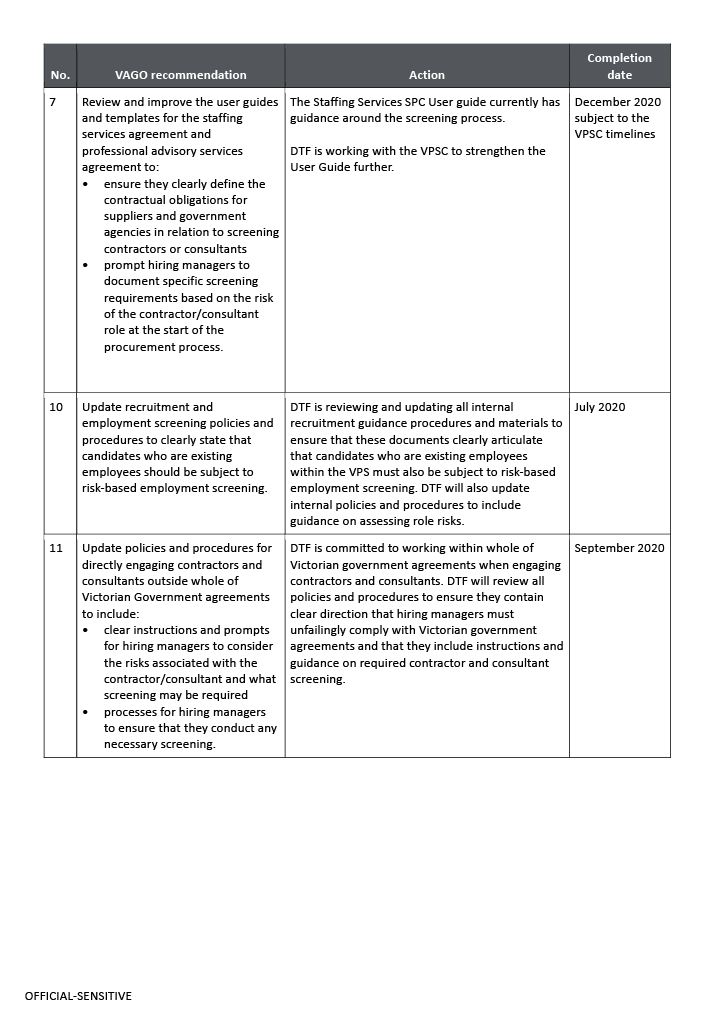

We recommend that all audited agencies:

10. Update recruitment and employment screening policies and procedures to clearly state that candidates who are existing employees should be subject to risk based employment screening (see Section 2.2).

11. Update policies and procedures for directly engaging contractors and consultants outside whole of Victorian Government agreements to include:

- clear instructions and prompts for hiring managers to consider the risks associated with the contractor/consultant role and what screening may be required

- processes for hiring managers to ensure that they conduct any necessary screening (see Section 3.7).

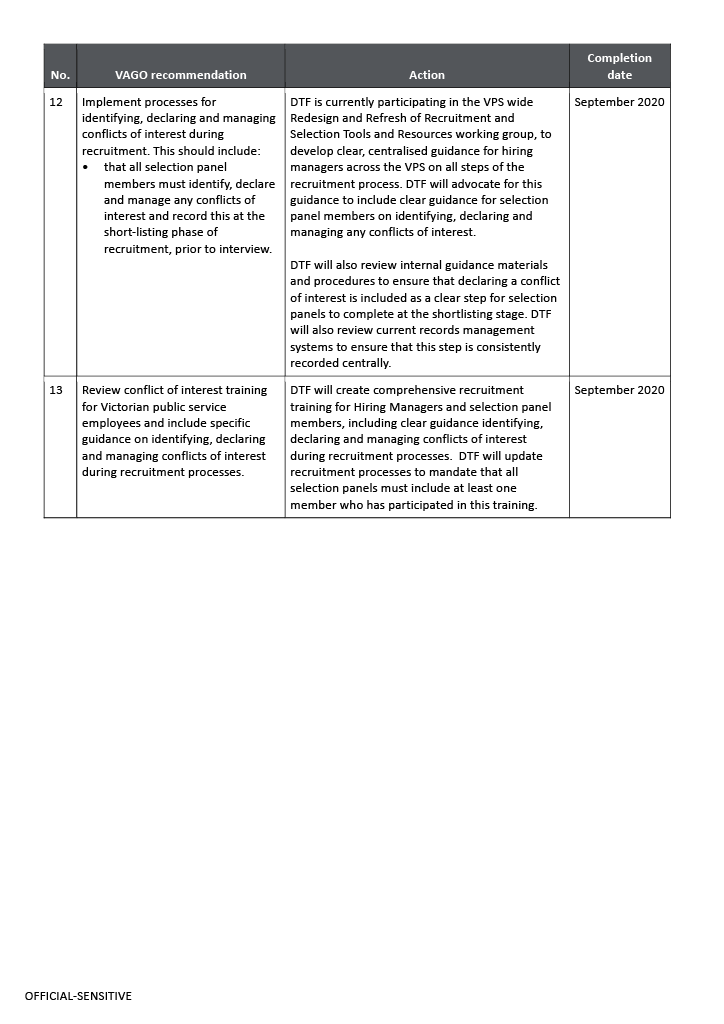

12. Implement processes for identifying, declaring and managing conflicts of interest during recruitment. This should include:

- that all selection panel members must identify, declare and manage any conflicts of interest and record this at the short listing phase of recruitment, prior to interview (see Section 2.7).

13. Review conflict of interest training for Victorian public service employees and include specific guidance on identifying, declaring and managing conflicts of interest during recruitment processes (see Section 2.7).

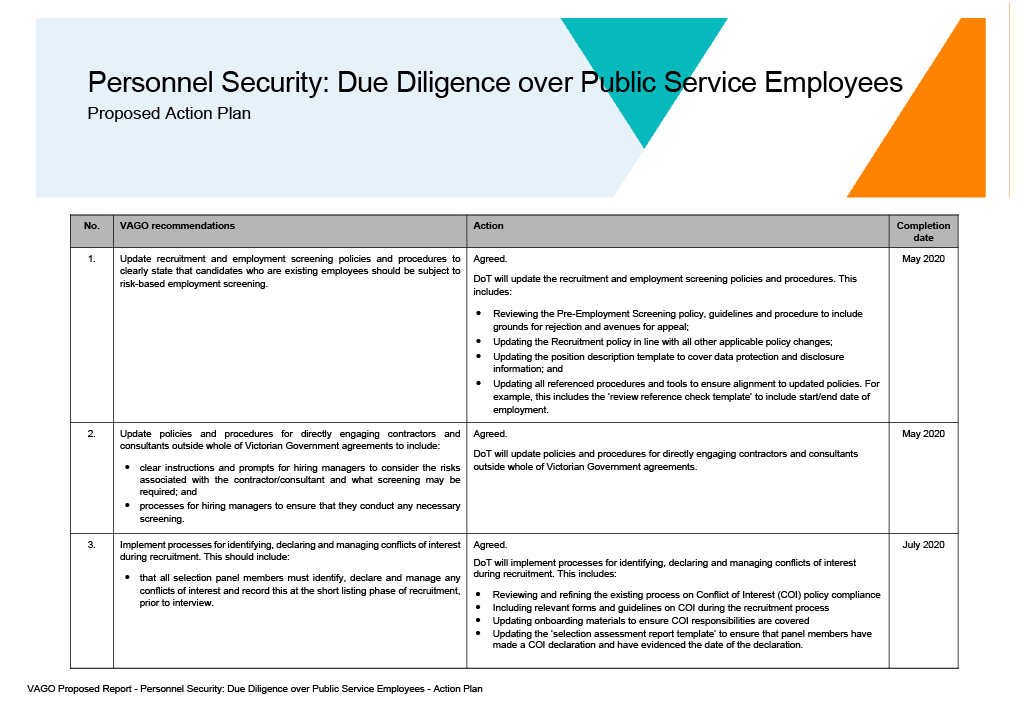

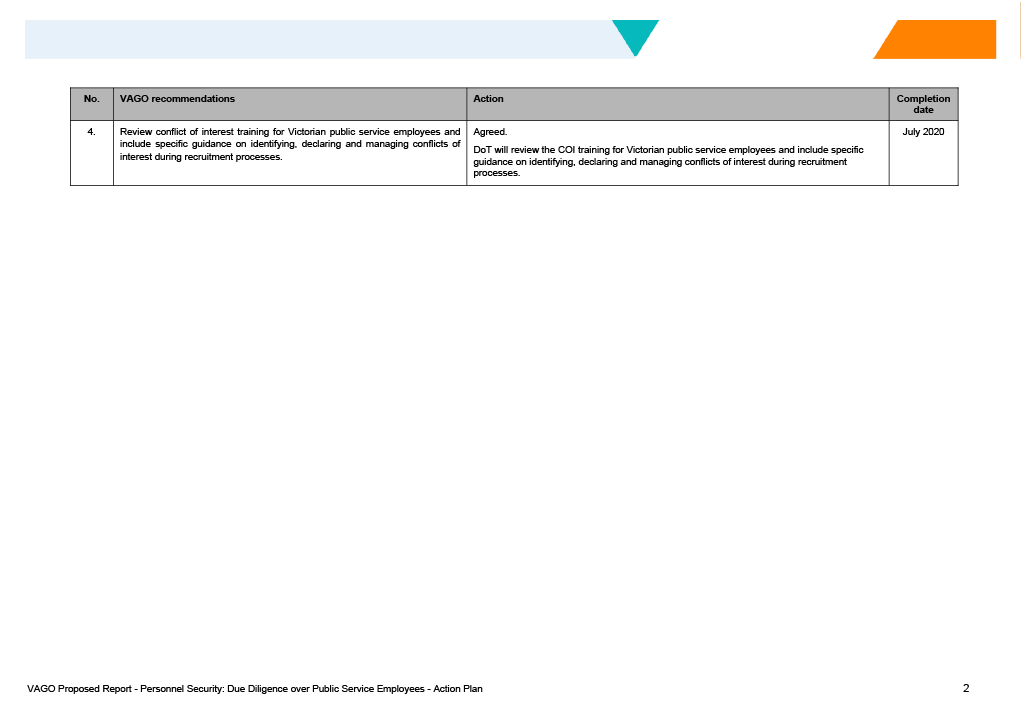

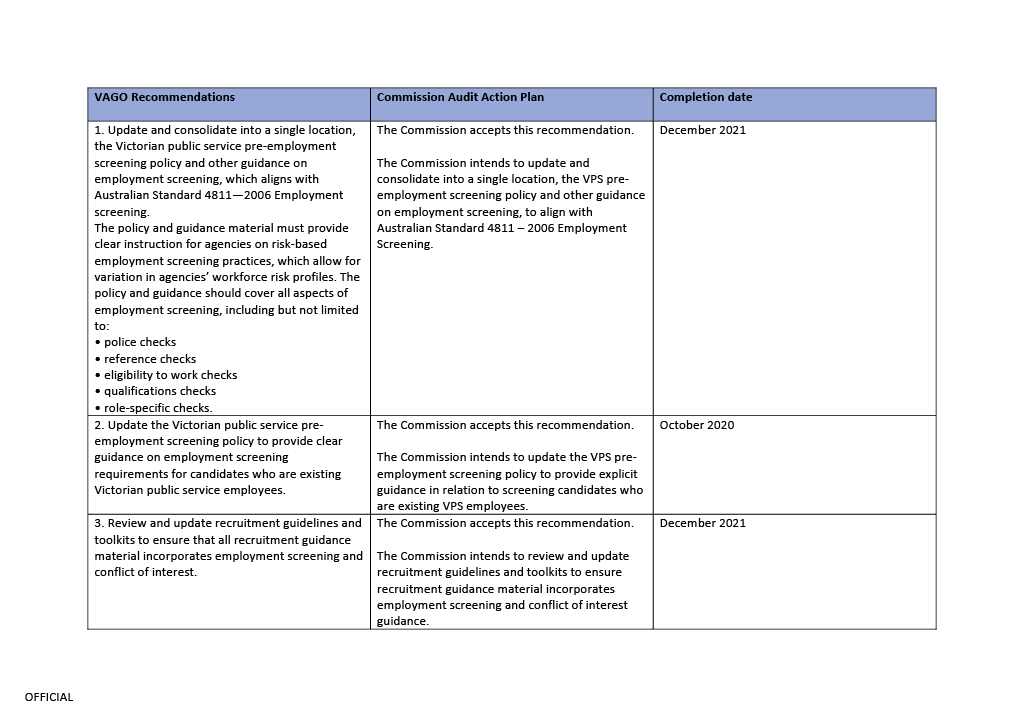

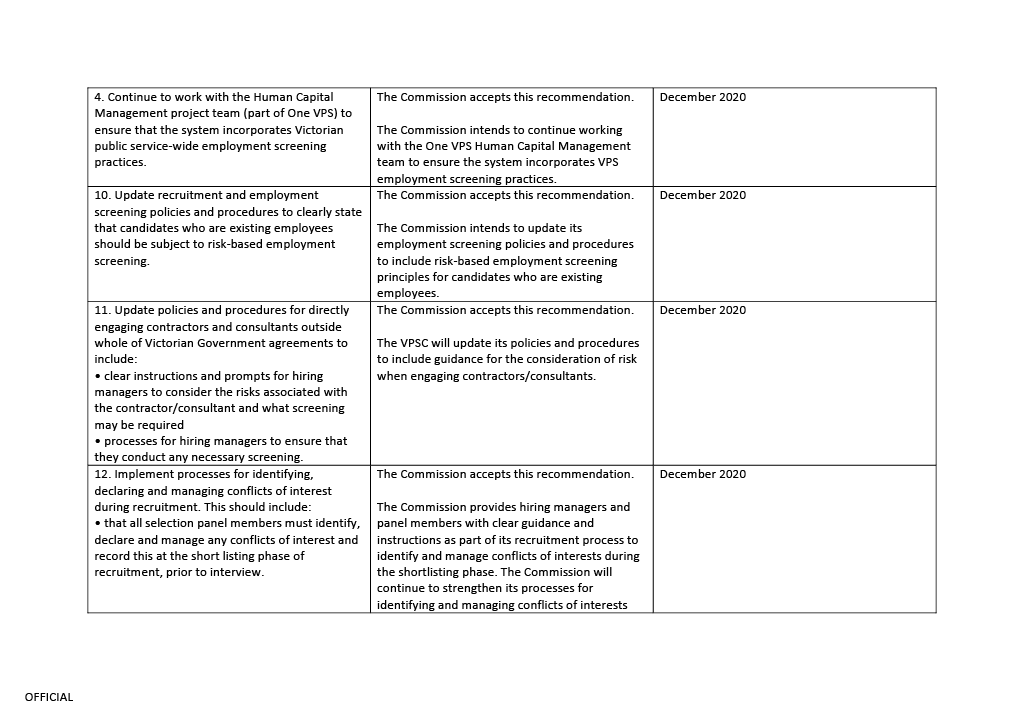

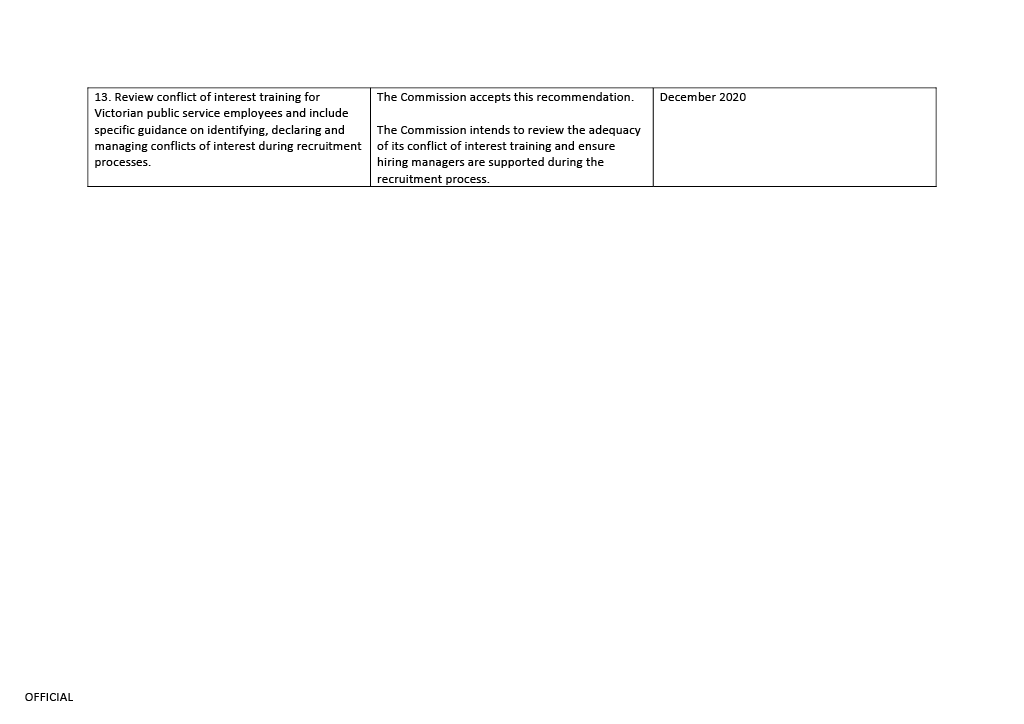

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with VPSC, DTF, DPC, DHHS, DELWP, DJCS, the Department of Jobs, Precincts and Regions (DJPR), DET, and DoT and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions.

As required by the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments. All agencies responded to the proposed report, accepted all the audit recommendations, and provided a detailed action plan to address them. Appendix A includes these responses and plans.

1 Audit context

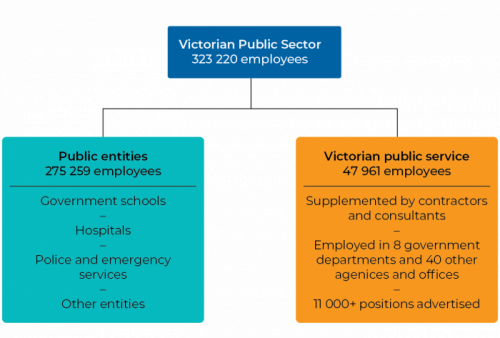

In 2018–19, the VPS employed 47 961 people. Personnel security—including employment screening—is a critical part of managing this workforce.

1.1 Why this audit is important

VPS employees hold positions of trust, with responsibility for administering Victoria’s finances and assets, and providing a wide range of services to the community, including vulnerable Victorians.

The public expects that VPS employees are competent and appropriately qualified, and that they act in the public interest.

Employment screening helps to safeguard the integrity of the VPS, reduce the risk of fraud and corruption, and maintain the quality and safety of government services.

1.2 The VPS workforce

Figure 1A shows the composition of the VPS workforce and how it fits into the broader Victorian public sector.

Figure 1A

VPS workforce 2018–19

Source: VAGO, based on VPSC data.

1.3 Recruiting the right people

The integrity of the VPS relies on recruiting the right people.

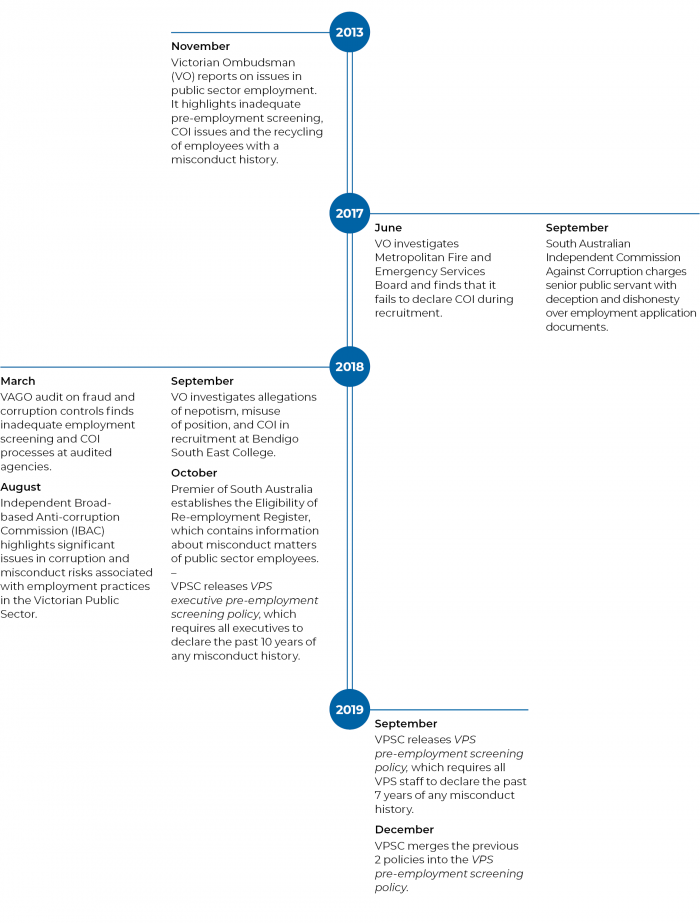

Integrity bodies in Victoria and interstate have repeatedly highlighted public sector recruitment as a high-risk area for fraud and corruption.

|

Fraud is dishonest activity involving deception that causes actual or potential financial loss. Corruption is dishonest activity in which an employee acts against their employer’s interests and abuses their position to achieve personal gain or advantage. |

Fraud and corruption risks

The VPS is susceptible to fraud and corruption risks during recruitment, including:

- false information on a resume

- false references

- failure to disclose a criminal record or past misconduct

- failure of hiring managers to to declare and manage a COI.

Figure 1B summarises relevant audits and investigations that have exposed these weaknesses across Australia, and recent policy changes in Victoria related to employment screening.

Figure 1B

Key investigations, audits and policy changes relating to employment screening

Source: VAGO, based on published reports and integrity bodies.

Employment screening requirements

Employment screening includes a range of pre-employment checks and, where appropriate, ongoing monitoring of employees.

Figure 1C summarises key employment screening activities in the VPS, based on better practice guidance from the Standard and relevant policies issued by VPSC. These are described further in Section 1.4.

Figure 1C

Key employment screening checks in the VPS

|

Type of check |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Identification |

To verify a candidate’s identity using the ‘100 points’ formula and sighting some form of photo identification. |

|

Criminal history check (police check)

|

To identify whether the candidate has a criminal record. Shows any findings of guilt and, in Victoria, also includes intent to summons and charges. An international police check may be warranted if an applicant has lived overseas for a substantial period of time. |

|

Qualifications |

To confirm currency and accuracy of any mandatory qualifications and professional memberships. |

|

Employment references |

To verify the candidate’s employment history and past conduct, including any performance concerns or misconduct matters. |

|

Declarations and consent |

For the candidate to disclose any misconduct history within the last 10 years for VPS executives and seven years for VPS employees. Provide candidate consent for the prospective employer to verify the candidate’s employment history with current and past employers. |

|

Eligibility to work |

To confirm:

|

|

Other—role specific |

To comply with any other role-specific requirements, for example, Working with Children Checks (WWCC). |

Source: VAGO, based on information from the Standard and VPSC policy guidance on employment screening.

Screening potential contractors and consultants

An agency can engage contractors and consultants using WoVG purchasing agreements, which includes SPCs and supplier registers. They can also use their own procurement processes.

Like VPS employees, contractors and consultants can hold positions of trust and, where necessary, they should be subject to the same screening.

WoVG agreements

State purchase contracts

DTF is responsible for managing and monitoring the following SPCs that we included in this audit:

- staffing services (SS) SPC—provides government agencies with fixed-term, permanent and executive staff for the administration, information technology and specialised recruitment categories

- professional advisory services (PAS) SPC—provides professional advice and consultancy services in relation to commercial and financial matters, tax, and probity.

eServices register

DPC is responsible for maintaining the eServices register. This register includes multiple suppliers for the public sector to engage across a broad range of information technology-related services, including the provision of software and equipment solutions and maintenance services.

Direct engagement of contractors and consultants

Government agencies can also use their own procurement processes when engaging contractors and consultants. This can occur when the hiring agency has resource needs outside the scope of the WoVG agreements or has tried unsuccessfully to find a suitable resource through WoVG agreements.

COI during recruitment

| A COI is where a person has private interests that could improperly influence, or be seen to influence, their decisions or actions in the performance of their public duties. Conflicts may be actual, potential or perceived. |

Recruitment is a high-risk area for COI. Employees involved in recruitment must identify, declare and appropriately manage any COI early in the recruitment process, for example if a candidate is a family member, friend or business associate.

In August 2018, VPSC released a model COI policy and guidance material for the Victorian public sector. It designed this to help government agencies assess their COI risks and implement their own COI policy, or align it with the new VPSC policy. The VPSC guidance clearly states that government agencies must ensure selection panels are aware of their obligation to declare and manage any COI during recruitment.

1.4 Legislation, policy and guidance

Australian employment screening standards

The Standard provides good practice guidance for employment screening. It is not mandatory but provides a foundation for VPS agencies to develop their employment screening policies and procedures. The Standard seeks to:

- reduce the risk of a security breach

- ensure the integrity of personnel within an organisation.

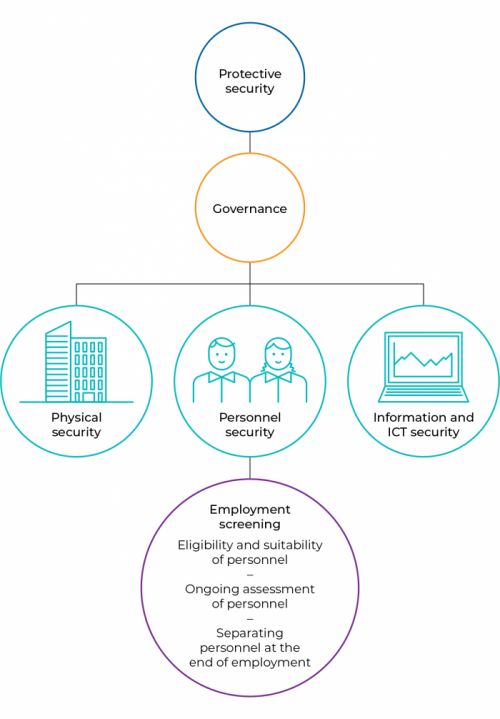

Protective security framework

The Australian Government’s Protective Security Policy Framework—issued by the Australian Attorney-General and mandatory for all Australian Government entities—states that personnel security is one of the three domains for protective security.

The Victorian Government does not have an equivalent whole-of-government protective security policy or framework. Instead, each VPS department and agency has its own approach.

Figure 1D shows how employment screening fits into an organisation’s protective security measures.

Figure 1D

Australian Government Protective Security Policy Framework 2018

Source: VAGO, based on information from the Protective Security Policy Framework.

Victorian employment-related legislation

The Public Administration Act 2004 and the Code of Conduct for Victorian Public Sector Employees 2015 set out the values and expected behaviours of VPS employees.

Under Part 3 of the Public Administration Act 2004, the Secretary of each department is responsible for employing VPS employees in their department. Part 2 obliges each Secretary, and in turn all VPS employees, to follow a set of employment principles, including that all recruitment decisions must be based on merit.

All employees must comply with the code of conduct, which includes demonstrating integrity and impartiality in all aspects of their role, including recruitment processes.

Each department must also take reasonable steps to minimise and manage the risk of fraud, corruption and other losses as per the Standing Directions of the Minister for Finance 2018, under the Financial Management Act 1994.

Victorian Protective Data Security Framework

Established under the Privacy and Data Protection Act 2014, and issued by the Office of the Victorian Information Commissioner, the Victorian Protective Data Security Framework Version 2, February 2020, aims to monitor and ensure the security of public sector information. The framework includes the Victorian Protective Data Security Standards October 2019, which are 12 high-level mandatory requirements to protect public sector information, covering:

- governance

- information security

- personnel security

- information technology security

- physical security.

These standards mandate that all agencies establish, implement and maintain personnel security controls. These actions help to ensure employees’ suitability to access public sector information and mitigate agencies’ personnel security risks.

VPSC policy

VPSC aims to strengthen public sector efficiency, effectiveness and capability, and to help maintain public sector integrity. VPSC is also responsible for developing Victorian public sector policies and procedures.

VPSC leads the development of VPS-wide pre-employment screening policies, which are mandatory for all VPS roles and aim to minimise the risks of employing unsuitable candidates. Figure 1E summarises the policies.

Figure 1E

VPS pre-employment screening policies

|

Date of release |

Policy |

Details |

|---|---|---|

|

30 October 2018 |

VPS Executive Pre-employment Screening Policy (rescinded) |

This policy stated that VPS executives must:

|

|

13 September 2019 |

VPS Pre-employment Screening Policy (rescinded) |

Introduced the same requirements for VPS employees as executives, except that they must disclose misconduct matters from the past seven years instead of 10. |

|

23 December 2019 |

VPS Pre-employment Screening Policy |

This policy replaced the previous two policies and covers both executives and VPS employees. It maintains the different time frame for past misconduct disclosures for VPS employees and executives. |

Source: VAGO, based on information from VPSC policies and guidelines.

Human Resources Systems Statement of Direction

In 2016, the Victorian Secretaries Board (VSB) issued the Human Resources Systems Statement of Direction for the VPS. It aims to uplift, modernise and deliver consistent human resources services across the VPS. Effective recruitment practices, including employment screening, are an important part of a human resources system.

| The VSB includes the secretaries of each department, the Chief Commissioner of Police and the Victorian Public Sector Commissioner. It aims to coordinate policy initiatives, promote leadership and information exchange information in the public sector. |

In January 2019, the VSB endorsed the establishment of One VPS as a branch within DPC. The One VPS initiative was designed to make it easier for the VPS to work together. Its remit included developing a shared human resources IT system for all government departments and Victoria Police, known as the HCM system. The HCM system is a critical part of the Human Resources Systems Statement of Direction for the VPS.

On 1 May 2020, the VSB announced that One VPS would cease, but the HCM project would continue as part of DPC's Enterprise Services Branch. The HCM project team is in the design phase, with implementation planned to start in 2020–21.

1.5 What this audit examined and how

We examined whether the audited agencies’ fraud and corruption controls regarding personnel security are well-designed and operating as intended. To do this, we:

- analysed the recruitment and employment screening policies and procedures at all VPS departments and VPSC

- compared policies and practices against the Standard, and VPS-wide policies and guidelines.

We then selected DHHS, DPC and DTF and performed detailed testing to determine how well they implement their policies and procedures and control personnel security risks.

We reviewed workforce and recruitment data and examined a sample of recruitment files from between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2019. We focused on whether these agencies had completed the following employment screening for successful candidates:

- police checks prior to their start date

- reference checks

- mandatory statutory declaration and consent forms for new executives.

We did not test the implementation of the VPS pre-employment screening policy, as it has only been effective since 1 October 2019.

We examined the screening practices for contractors and consultants engaged through three WoVG agreements, and the audited agencies policies and procedures for engaging contractors and consultants outside the WoVG agreements.

We also examined policies and procedures relating to COI during recruitment across all audited agencies.

We used data to examine whether:

- agencies hired ex-VPS employees between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2019, who had been terminated for misconduct or had resigned during a misconduct investigation between 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2019

- staff engaged through the SS SPC between 1 July 2017 and 30 June 2019 had a police check prior to starting work.

We conducted our audit in accordance with the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements.

The cost of this audit was $490 000.

1.6 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines employment screening of VPS employees.

- Part 3 examines screening of contractors and consultants.

2 VPS employee screening

Employment screening is a critical part of personnel security because it helps to ensure that candidates are suitable for VPS roles.

In this Part, we examine all audited agencies’ employment screening policies and procedures, and how DHHS, DPC and DTF implement them.

We also examine if audited agencies are managing COI risks during recruitment.

2.1 Conclusion

All audited agencies have employment screening policies and procedures that minimise the risk of recruiting external candidates who would be unsuitable VPS employees. However, the agencies do not apply this same rigor to candidates who are existing VPS employees. In particular, agencies are not undertaking and/or documenting reference checks for these candidates.

We also found that agencies do not sufficiently focus on identifying and managing COI during recruitment, with panel members not routinely declaring and managing any conflicts prior to interviewing candidates.

These gaps increase the risk of hiring unsuitable candidates and exposes the VPS to fraud and corruption.

VPSC’s VPS-wide pre-employment screening policy is a positive step towards a consistent, better-practice approach. However, it does not cover all employment screening activities detailed in the Standard and it does not provide clear instruction for agencies on all aspects of employment screening.

2.2 Employment screening policies and procedures

Police checks

Policies, procedures and guidance

All audited agencies recognise that police checks, including identity checks, are a key component of employment screening. Agencies can use a third-party provider to conduct police checks or seek accreditation with the Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission to conduct police checks themselves.

Figure 2A summarises the policies, procedures and guidance on police checks for each agency against the Standard’s key recommended elements.

Figure 2A

Policies, procedures and guidance on police checks

|

Key recommended elements from the Standard |

DELWP |

DET |

DHHS |

DJCS |

DJPR |

DoT |

DPC |

DTF |

VPSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

General information |

|||||||||

|

Authorised body conducts police checks |

Third-party |

DET |

DHHS |

DJCS and VicPol |

Third-party |

Third-party |

Third-party |

Third-party |

Third-party |

|

Consent obtained from candidate prior to police check |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Who requires a police check? |

|||||||||

|

External candidates |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔(a) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔(b) |

✔ |

|

Internal candidates |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔(c) |

Partial(d) |

Partial(d) |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

|

International candidates(h) |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Partial(e) |

✘ |

✔ |

Partial(e) |

|

Timing of police checks |

|||||||||

|

Complete check before start date(f,g) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Periodic police checks throughout employment |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

Partial(d) |

Partial(d) |

✘ |

✘ |

✘ |

(a) For engagements longer than six weeks.

(b) For staff engaged longer than eight weeks and for executive officers engaged for longer than six months.

(c) Mandatory for specific high-risk roles only, such as prison employees.

(d) Not mandatory but may be requested by hiring manager or required for some roles.

(e) Checks done but not documented in policy/procedure.

(f) Except for international police checks.

(g) The Standard recommends completing checks before offer of employment (not the start date) and recognises this is preferable but not always possible.

(h) Police check completed for candidates who have resided overseas for a substantial period of time.

Source: VAGO.

Using third-party providers for police checks

All agencies, except DTF, use the same third-party provider to conduct police checks. Each agency has individual contracts with varying conditions and rates.

Adopting a risk-based approach

The Standard recommends that agencies base employment screening on the level of risk associated with the role. High-risk roles require more extensive screening. This applies equally to external and internal candidates.

However, as shown in Figure 2A, only DET and DJCS’s recruitment policies specifically state that police checks should be conducted for internal candidates. This means that an employee may have a police check at the start of their employment then never have one again, regardless of the time they have worked in the VPS or the various positions they may hold. During the employee’s career, there may be some changes to their criminal history that may result in them being unsuitable for their current role.

DJCS’s policy states that it does not accept previously completed police check certificates from other agencies. This is appropriate, because police certificates are only valid for six months and DJCS has high-risk roles, such as prison officers, that require more detailed checks.

The Standard also recommends that agencies take a risk-based approach by periodically screening employees. This includes conducting periodic police checks throughout a staff member’s employment. We found that no audited agencies are currently doing this.

Keeping records of police checks

VPSC refers to the PROV standard titled Retention and Disposal Authority for Records of Common Administrative Functions, which authorises the disposal of police checks. The PROV standard outlines that police checks may be destroyed six months after they recruit a new employee. PROV provided advice to VAGO that like all disposal actions in their Standards, the six-month time frame is a minimum requirement, meaning that agencies can choose to destroy police check records any time after this period.

We found that agencies have inconsistent practices for disposing of police check records. For example:

- DET, DHHS and DJCS destroy police check records after three months for roles that are not direct client services

- DELWP, DJPR, DOT and VPSC’s internal procedures do not specify when to dispose of police check records.

The Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission (ACIC) has accredited DHHS, DET and DJCS to conduct their own police checks. While their practice of destroying police check records after three months complies with the ACIC’s requirements, it is not consistent with the PROV standard. VPSC has agreed to consult with PROV and update their guidelines to provide clear instructions for agencies.

Compliance with police checks at DHHS, DPC and DTF

We examined DHHS, DPC and DTF’s recruitment files and payroll data to determine if these departments complete police checks for new employees in line with their policies and procedures. As shown in Figure 2B, DHHS did so for all new employees, while DPC and DTF did so for the vast majority.

Figure 2B

Police checks for new employees, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019

Note: Incomplete police checks include those where the selection report or other records did not provide a reason for not requiring a police check.

Note: Analysis of DHHS data included all new employees. DPC and DTF analysis was based on a random sample. See Appendix B Data analysis methodology for details.

Source: VAGO.

Timing of police checks at DHHS, DPC and DET

Completing a police check before a new employee starts ensures that an agency knows the employee’s criminal history before they can access information and resources, and potentially service vulnerable clients. This minimises the agency’s exposure to financial, information and reputational risks, as well as any risks to client safety.

Figure 2C summarises the percentage of police checks completed before an employee's start date at DHHS, DPC and DTF.

Figure 2C

Police checks completed before employee start dates

Note: Testing period was 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019. See Appendix B Data analysis methodology for details.

Source: VAGO.

DHHS’s high rate reflects its strong policy and procedural controls. For example, DHHS will not put new employees on the payroll system if they do not have a police check date and receipt number. This is appropriate given that many DHHS jobs are high-risk, such as roles in child protection.

DPC’s results reflect its recruitment policy and procedures, which do not specify that police checks should occur before new employees start.

While this may be appropriate for low-risk roles, it is not consistent with the Standard and should only occur if there is a valid exception. However, DPC has a new draft policy that requires police checks to begin before it sends offers of employment, which should address this issue.

DTF’s policy states that new employees should finalise their police check prior to their start date. However, as shown in Figure 2C, this is often not occurring.

Reference checks

Reference checks allow agencies to confirm the accuracy of a candidate’s employment history and identify any issues with their previous conduct. They also help hiring managers better understand and assess a candidate’s suitability.

Figure 2D summarises the audited agencies’ reference check policies and procedures. All agencies have reference checks as part of their employment screening requirements, although requirements for internal candidates are not always clearly stated. This means that hiring managers may not be aware of an existing employee’s performance and suitability for a role.

Figure 2D

Policies and procedures on reference checks

|

|

DELWP |

DET |

DHHS |

DJCS |

DJPR |

DoT |

DPC |

DTF |

VPSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

General information |

|||||||||

|

Reference checks required |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

At least one referee is a current or recent direct manager/supervisor |

Partial(a) |

Partial(a) |

Partial(b) |

✔ |

✔ |

Partial(a) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Agency may contact non-nominated referees (with the candidate’s consent) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Not stated(c) |

Not stated(c) |

✔ |

Not stated(c) |

✘ |

|

Reference check template includes a specific question/s on conduct issues |

Partial(d) |

Partial(d) |

✔ |

Partial(d) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Number of reference checks required |

|||||||||

|

External candidates |

2 |

Not stated(c) |

2 |

2 |

2(a) |

2(a) |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

Internal candidates |

Not stated(c) |

Not stated(c) |

2 |

2 |

2(a) |

2(a) |

Not stated(c) |

1 |

1–2(e) |

(a) Documented in the reference check template or guide, but not in a policy/procedure.

(b) Preferred but not mandatory.

(c) Not documented in employment screening policy/procedure or recruitment and selection policy/procedure.

(d) No specific question on conduct issues but includes questions on professionalism or if the referee would employ them again and why.

(e) At the discretion of VPSC. Depends on how long candidate has been working at VPSC.

Source: VAGO.

Compliance with reference checks at DHHS, DPC and DTF

We examined a sample of recruitment records at DHHS, DPC and DTF to determine if they complete reference checks in line with their policies and procedures.

We found that overall there is poor compliance with reference checks, as shown in Figure 2E.

Figure 2E

Completion of reference checks, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019

Note: Reference checks that were marked as complete in the selection report but had no evidence attached were considered incomplete.

Note: See Appendix B Data analysis methodology for details.

Source: VAGO.

The low compliance rate in Figure 2E is likely caused in part by the poor record keeping practices we found for reference checks at all three agencies:

- DPC relies on hiring managers to store copies of reference checks, but it does not provide instructions on how to do this.

- DTF’s reference check template instructs hiring managers to attach reference checks to the selection report. However, this is not occurring, and the new version of the template does not include this prompt.

- DHHS also instructs hiring managers to attach reference checks to the selection report. While DHHS’s regional divisions complied with this requirement in 94 per cent of our sample files, the central division only complied 7 per cent of the time.

This means reference checks cannot always be found, which is a problem if a candidate challenges a recruitment decision, or if questions arise about an employee’s suitability. It is also likely that at least some of these hires occurred in the absence of reference checks, which misses a vital opportunity in the recruitment process to not only ensure the best candidate is hired but also avoid introducing security risks into the agency.

Role-specific checks

Qualification, accreditation and professional membership checks

Qualification, accreditation and professional membership checks help hiring managers determine if a candidate has the appropriate knowledge and skills to perform a role. We found inconsistent practices across the agencies for these checks. DTF and DELWP did not have a process in place at all, which increases the risk of hiring unqualified staff.

Figure 2F summarises the agencies’ policies and procedures for conducting qualification, accreditation or professional membership checks.

Figure 2F

Policies and procedures for checking qualifications/accreditations/professional membership

|

Policy requirement |

DELWP |

DET |

DHHS |

DJCS |

DJPR |

DoT |

DPC |

DTF |

VPSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Requires qualifications check |

Partial(a) |

✔(b) |

✔(b) |

✔(b) |

✔(b) |

✔(b) |

✔(b) |

✘ |

✔(b) |

|

Requires accreditations/ professional membership check |

✘(c) |

✔(b) |

Partial(d) |

✔(b) |

✔(b) |

✘ |

✔(b) |

✘ |

N/A(e) |

|

Requires candidate to provide proof of qualifications/ accreditations/ professional membership |

✘(c) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Verifies qualifications/ accreditations/ professional membership by contacting issuing body |

✘(c) |

✔ |

✔(f) |

Partial(d) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

(a) May be required for mandatory qualifications/accreditations/professional memberships.

(b) Required for mandatory qualifications/accreditations/professional memberships only.

(c) Agency advised is done in practice, but not documented in employment screening policy/procedure or recruitment and selection policy/procedure.

(d) Required or conducted but not documented in employment screening policy/procedure or recruitment and selection policy/procedure.

(e) Does not have roles with mandatory professional accreditations/registrations/memberships.

(f) Risk-based; only if there are concerns about the qualification.

Source: VAGO.

Working with Children Checks

The Working with Children Act 2005 aims to prevent harm to children by ensuring appropriate checks of people who work or volunteer with children. A WWCC involves checking a person’s:

- criminal history relating to serious sexual, violent and drug offences

- professional conduct, by checking with registration schemes and panels.

Unlike a police check, a WWCC provides certification of suitability to work with children. It is valid for five years. The WWCC unit at DJCS continuously monitors the status of everyone with a WWCC and notifies employers if they identify any relevant updates or changes to an individual’s criminal history.

The WWCC process involves the following steps:

- Employees must provide a WWCC receipt number before starting work, as evidence they have applied for a WWCC.

- Employees must list all organisations they currently work or volunteer for on their WWCC application.

- Organisations must keep records of the original receipt number and the final assessment notice.

- Employees must apply for a new WWCC before their current check expires.

We reviewed policies and procedures for audited agencies that have employees who work with children, summarised in Figure 2G.

Figure 2G

WWCC procedures

|

|

DELWP |

DET |

DHHS |

DJCS |

DJPR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Requires current WWCC prior to beginning roles that involve child-related work |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

Partial(a) |

|

Requests employees to register the agency as their employer with the WWCC unit |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

|

Requests employees to register the agency as their employer with the WWCC unit |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

(a) Required but not documented in employment screening policy/procedure or recruitment and selection policy/procedure.

Source: VAGO.

Agencies with many employees in child-related work have thorough policies and procedures. We did not see the same strong processes at agencies with small numbers of child-related roles. This is concerning given the potentially serious consequences of unsuitable employees working with children.

We examined DHHS’s processes in more detail and found strong controls to ensure that, where necessary, staff complete or renew WWCCs prior to working with children. DHHS:

- records WWCC details on its payroll system and employment cannot progress without this information

- has a dedicated safety screening coordinator, who monitors the status of all WWCCs and conducts monthly compliance reporting.

Eligibility to work checks

Right to work in Australia

All candidates applying for a role in the VPS must be an Australian citizen, permanent resident, or hold a valid work permit or visa. Candidates must declare their right to work in Australia in their application.

Agencies collect a preferred candidate’s proof that they are able to work in Australia as part of the identity and police checks. When a candidate is not an Australian or New Zealand citizen, all agencies, except for DJPR and DTF, have clearly documented procedures to verify visa status through the Australian Department of Home Affairs’ Visa Entitlement Verification Online system. DJPR and DTF do not specify this requirement in their recruitment processing, which increases the risk it will not be done.

Voluntary Departure Package

Victorian public sector agencies can offer a voluntary departure package (VDP) to employees when they require large-scale structural change or employee reductions. Employees who accept this agree to a three-year restriction on re employment in the Victorian public sector.

All candidates applying for a role in the VPS must declare if they have received a VDP in the past three years.

There is currently no WoVG register or checking mechanism for agencies to confirm whether candidates’ attestations on VPDs are correct. Agencies rely on the candidate to accurately disclose this in their application. If fully implemented, the VPS-wide HCM system will help to address this issue by maintaining a single record of a candidate’s past VPS employment.

Instruction and training for hiring managers

Many hiring managers do not routinely engage in recruitment. Agencies must provide detailed, consistent instructions and, where necessary, more formal training to ensure that hiring managers follow the recruitment process, including employment screening.

We found that all agencies provide sufficient instructions online, or in guidance material, to prompt hiring managers to conduct employment screening and reference checks in line with the agency’s policy.

DET, DJCS, DJPR and DPC provide formal recruitment training that includes reference checks. However, only DJPR’s formal training educates hiring managers on employment screening, a critical step in the recruitment process.

All agencies rely on their human resource teams to provide instruction and advice as needed to hiring managers during the recruitment process.

Only DPC provides guidance to its employees on providing a reference for current or past employees. Although it is not a requirement under the Standard, this signals DPC’s expectations of its staff when acting as a referee, including what information they can disclose.

Monitoring compliance

Monitoring compliance with employment screening helps identify risks and assure an agency that its processes are working.

Most agencies have strong controls to monitor compliance with police checks, but not for other important employment screening activities. In particular, agencies lack monitoring over role-specific checks, such as mandatory qualification checks and executive officer declarations.

Agencies do not have risk-based compliance and quality assurance processes, such as periodic reviews of recruitment files, that cover all aspects of employment screening.

No agency has a comprehensive checklist or process that requires hiring managers to confirm they have completed all relevant employment screening checks.

Without the ability to detect candidates who have not completed all relevant employment screening checks, agencies may employ candidates who are not suitable.

2.3 Managing adverse screening outcomes

The audited agencies do not automatically exclude candidates with an adverse employment screening check result. All agencies, excluding DELWP, have a documented process for assessing an adverse screening outcome, which primarily relates to a candidate with a criminal history.

To assess an adverse employment screening check, agencies use a panel that typically includes a representative from human resources, an executive director and potentially the hiring manager. The panel assessment considers:

- the nature, severity and frequency of the offence

- the length of time since the offence took place

- whether the candidate committed the offence as a juvenile or as an adult

- any mitigating or extenuating circumstances

- the type and severity of any penalty imposed

- the relevance of the offence to the role they have applied for (for example, an information, financial and safety risk to the agency or the agency’s clients)

- the candidate’s character since the offence (for example, a steady employment record and favourable references from recent employers).

Based on this assessment, the Secretary, Commissioner or a delegated authority, such as a Deputy Secretary or Executive Director, decides whether the candidate is suitable for employment. At DELWP, DET and DJCS, policies and procedures relating to adverse screening outcomes do not clearly state who is responsible for deciding whether the adverse screening outcome prevents employment. Figure 2H summarises agencies' processes.

Figure 2H

Policies and procedures for managing adverse screening outcomes

|

Policy requirement |

DELWP |

DET |

DHHS |

DJCS |

DJPR |

DoT |

DPC |

DTF |

VPSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Documented process to assess adverse screening outcome |

Partial(a) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Responsibility for conducting assessment and making a recommendation is clear |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Decision-making responsibility clearly stated |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

Avenues of appeal available to internal and external candidates |

✘ |

✔ |

Partial(b) |

✔ |

✔ |

Partial(c) |

✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

(a) Process exists but not documented in policy/procedure.

(b) Documented in the Safety Screening Assessment Form, but not in a policy/procedure.

(c) Request for re-confirmation and further checking available if initial result disputed but avenues of appeal for assessment decision not stated in policy/procedure.

Source: VAGO.

Managing adverse screening outcomes at DHHS, DPC and DTF

We examined whether DHHS, DPC and DTF comply with their policies and procedures relating to adverse screening outcomes.

Figure 2I shows that DHHS deviated significantly from its procedure in six of the 17 files we reviewed (35 per cent). These files did not have a completed assessment form, which means there is no record of what factors the panel considered, the reason for the final decision and ultimately whether the candidate was suitable for the role. Of these six, five resulted in the candidate not being employed. This creates a risk for DHHS if a candidate contests a decision, or if concerns arise about a hired candidate’s suitability.

DPC followed its procedure in eight out of 10 files we reviewed (80 per cent). In the other two files, DPC’s assessment panel only included two of the three required members.

Figure 2I

Compliance with procedures for managing adverse screening outcomes, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019

Note: For DHHS we randomly selected a number of files due to a large number of files available. DTF and DPC had smaller numbers of adverse screening outcomes, so we examined all files.

Source: VAGO.

The departments employed some, if not all, of the candidates with an adverse screening outcome, as shown in Figure 2J.

Figure 2J

Adverse screening outcome and employment, 1 July 2017 to 30 June 2019

Note: For DHHS we randomly selected a number of files due to a large number of files available. DTF and DPC had smaller numbers of adverse screening outcomes, so we examined all files.

Source: VAGO.

2.4 VPS-wide employment screening policies

If consistently implemented, VPSC’s VPS-wide pre-employment screening policy will help ensure consistent practices and reduce fraud and corruption risks during recruitment. We outline the key features of the policy below.

|

Key policy feature |

Details |

|

Candidate statutory declaration |

This requests the candidate to disclose:

|

|

Candidate consent form |

This allows the prospective employer to:

|

|

General employment screening guidance |

Guides agencies to:

|

We found that while the policy intends to set a minimum standard for pre employment screening, it focuses primarily on a candidate’s misconduct history. This is not consistent with the pre-employment screening detailed in the Standard, which covers all aspects of pre-employment screening, such as police, reference and qualification checks.

VPSC publishes other guidance material related to employment screening, such as its online Guidance for conducting police checks March 2015. However, this guidance, along with VPSC’s recruitment policies and procedures, does not provide an integrated, comprehensive source of information on pre employment screening for agencies.

We also found that agencies often misinterpret the intent and scope of the policy. We summarise the key gaps and issues with the policy requirements below.

|

Policy requirement |

Gap/issue |

|

Application of policy to internal candidates |

The policy clearly states that pre-employment screening requirements are based on the risks and requirements of a position. However, it does not explicitly state that pre-employment screening applies equally to internal and external candidates |

|

Minimum standard for pre-employment screening in the VPS |

The policy aims to set a minimum standard for pre-employment screening but focuses primarily on misconduct. Other VPSC guidance on some aspects of pre-employment screening has not been integrated into the policy. |

|

Declarations of past misconduct history |

Agencies can use employment termination agreements, known as deeds of release, which can include confidentiality clauses. These clauses can prevent a candidate from disclosing a past misconduct matter. VPSC acknowledges that this can present integrity risks for future employers. Currently, candidates can select ‘do not know/cannot answer’ on declarations, but there is limited practical guidance for agencies on how to manage this type of declaration, aside from ensuring they maintain confidentiality. |

|

Validating misconduct declarations This involves contacting the candidate’s previous employer to make sure their declaration is correct |

The revised VPS pre-employment screening policy clearly instructs agencies to take a risk based approach to validating misconduct declarations. However, it does not specify that this includes validating declarations where no history of misconduct has been disclosed. |

|

Candidate’s consent to contact past employers to substantiate employment history and past conduct and performances |

Guidance is not clear as to whether this allows prospective employers to contact non nominated referees, or if the consent only relates to validating misconduct declarations. |

In September 2019, VPSC established the VPS pre-employment screening implementation working group, to consult with VPS agencies and generate best practice solutions for operational issues related to the policy. The working group has established a central contact point for each agency, which prospective employers can contact to validate a misconduct declaration. This streamlines the process and helps maintain the privacy of individuals involved.

Implementing the VPS executive pre-employment screening policy

We examined if agencies had implemented the VPS executive pre employment screening policy. At the time of our audit, the policy had been mandatory for all VPS departments for 10 months.

Only DET, DoT, DPC and VPSC have clearly defined the executive pre employment screening requirements in their recruitment policy and procedures. This creates the risk that the other agencies will not fully implement the executive pre-employment screening policy and they may not know about a candidate’s misconduct history before employing them.

Compliance with the policy at DHHS, DPC and DTF

We analysed implementation of statutory declaration and consent forms at DHHS, DPC and DTF from 30 October 2018, when the policy began, to 30 June 2019. This involved reviewing 14 recruitment files at DHHS, 17 at DPC and two at DTF.

The departments varied in their level of compliance, as shown in Figure 2K. Overall, 48 per cent of new executives did not complete the statutory declaration and consent form. Of these, more than half were internal candidates. This highlights our finding that the scope of the policy was not clear, as it did not explicitly state that pre-employment screening applied to internal candidates.

Figure 2K

Executives’ completion of statutory declarations and consent forms, 30 October 2018 to 30 June 2019

Source: VAGO.

2.5 VPS HCM system

The proposed HCM system, which is in the early design phase and scheduled to start implementation in 2020–21, aims to incorporate employment screening requirements into the recruitment process.

If successfully implemented, agencies could use the HCM system to access relevant employment-related information about current and former VPS employees. This could reduce duplication of checks as employees move between agencies. For example, the HCM system could provide a central record of an employee’s:

- police check date and receipt number

- reference checks

- reason for departure

- eligibility for employment

- role-specific checks, such as mandatory qualifications and WWCC.

It is important that DPC and the HCM project team continues to work with the VPSC and VPS agencies to ensure the HCM system improves employment screening practice, is consistent with the Standards and VPS-wide policies, and does not create information privacy risks.

2.6 VPS employees with misconduct history

Having accurate information about a candidate’s past performance and conduct is critical to recruiting the right person. This includes information about any involvement in misconduct investigations.

We assessed the risk of the audited agencies re-employing ex-VPS employees with a misconduct history by:

- obtaining misconduct data from each audited agency from 1 July 2015 to 30 June 2019. This included employees who were:

- terminated for misconduct

- resigned during a misconduct investigation

- comparing this data against payroll data for each audited agency in 2017–18 and 2018–19 to identify if any of these employees were re employed in this period.

We found that nine of 205 employees (4 per cent) were re-employed in the VPS after being terminated for misconduct or resigning during a misconduct investigation. Figure 2L summarises this.

Figure 2L

VPS employees re-employed after being terminated for misconduct, or resigning during a misconduct investigation

Source: VAGO, from data provided by audited agencies.

These findings do not prove that the employees involved provided false or misleading information during recruitment. It is important to note that:

- until recently, candidates did not have to declare past misconduct matters

- the candidate may have disclosed their misconduct history during recruitment, and the hiring manager may have assessed that this did not affect their suitability for the role

- resignation during a misconduct investigation is not prohibited and does not mean that the employee was guilty of the alleged conduct.

Agency-specific practices

Reference checks and the mandatory statutory declarations of misconduct history are the main ways a hiring manager can identify a candidate’s past misconduct. The following agencies have taken further steps to reduce the risk of employing a candidate without identifying any past misconduct.

DET

DET’s employment limitation policy allows it to restrict an individual’s eligibility for employment with DET. It applies employment limitations on former employees dismissed for substantiated misconduct and those who resign during a misconduct investigation. An employment limitation check can provide an additional layer of assurance that a preferred candidate is suitable for employment.

DET records employment limitations in its payroll system. Preferred candidates cannot be entered into the payroll system if they have an employment limitation. It is the hiring manager’s responsibility to check with payroll to ensure that a preferred candidate does not have an employment limitation.

DHHS and DJCS

DHHS and DJCS have the following processes to check the misconduct history of current or former employees:

- DHHS’s referee check template prompts hiring managers to contact the relevant People and Culture team to check for misconduct history.

- DJCS’s Recruitment Services crosschecks the workplace relations database weekly to identify all candidates who are current or former DJCS employees with instances of misconduct and poor performance recorded.

These processes help hiring managers determine a candidate’s suitability for the role.

2.7 Conflicts of interest during recruitment

Identifying, declaring and managing a COI is necessary to ensure a fair and transparent recruitment process. If recruitment panel members do not declare a COI, their decisions may not be objective. Recent investigations from IBAC and other integrity bodies around Australia have highlighted recruitment as a high risk area for COI.

COI policy and procedures

We reviewed the COI policies and procedures in all audited agencies. We found that all nine agencies had a COI policy that required employees to avoid wherever possible, or identify, declare and manage any COI.

While all agencies identified recruitment as a high-risk activity in their COI policies, we found that aside from DELWP, this did not translate into thorough recruitment and selection policies and practices that reduce the COI risk. Figure 2M summarises our findings.

Figure 2M

Incorporating COI risks into recruitment and selection process

|

Policy requirement |

DELWP |

DET |

DHHS |

DJCS |

DJPR |

DoT |

DPC |

DTF |

VPSC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

COI risks incorporated into recruitment and selection policies |

✔ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

Partial(a) |

Partial(a) |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

|

Clear process for selection panels to identify, declare and manage any COI prior to interview stage |

✔ |

✘ |

Partial |

✔ |

✘ |

✘ |

✔ |

✘ |

✔ |

(a) Recruitment policy states processes must be conducted in line with the COI policy but provides no other guidance.

Note: During the audit, DHHS and DPC improved their process for selection panels to identify, declare and manage COI, and they are implementing this revised process.

Source: VAGO, based on information provided by agencies.

Agencies that do not have a clearly documented process for selection panels to follow, increase the risk that a COI will not be identified or declared. Of particular note, only DELWP, DJCS, DPC and VPSC require the selection panel to declare a COI prior to the interview process commencing. The lack of COI controls during recruitment poses a critical integrity risk and is particularly concerning for agencies involved in commercial decisions or large projects.

We were unable to audit compliance with COI policies and procedures at DHHS, DPC and DTF. This is because the three agencies do not have clearly documented processes for selection panels to declare, record and manage any COI.

COI training

Training and instruction provided to managers

We found inconsistent practices across the audited agencies for training managers about COI in recruitment.

While all nine agencies made their COI policy available online, only DET and DJCS provide COI training that has a focus on recruitment risks. In both these agencies, training modules include specific examples for selection panels to identify, declare and manage any COI during recruitment. These agencies also require at least one member of the selection panel to have received the training and DET requires that each panel member indicate on the selection report whether they have received the training.

DPC is currently reviewing its COI training to include specific recruitment risks and the other agencies either do not provide any formal COI training, or the training does not include a focus on recruitment.

3 Screening contractors and consultants

Contractors and consultants contribute significantly to the VPS. They provide a broad range of services, both onsite and remotely. Like VPS employees, they can hold positions of trust and, where necessary, should be subject to the same screening as employees.

3.1 Conclusion

The audited agencies do not have processes to make sure that contractors and consultants undergo risk-based screening prior to working in the VPS. This creates a significant risk that agencies are engaging unsuitable contractors and consultants.

The WoVG agreements for engaging contractors and consultants do not clearly specify screening obligations for suppliers. Audited agencies do not understand their obligations to request screening from suppliers when engaging contractors and consultants. However, DTF and DPC are considering how to rectify these gaps and strengthen screening requirements as they renegotiate the WoVG agreements.

3.2 Engaging contractors and consultants

Government agencies can engage contractors and consultants directly through their own procurement processes or through WoVG agreements, including SPCs and supplier registers.

We assessed contracts, user guides and templates for three of the most commonly used WoVG agreements to determine if they include screening requirements for contractors. These are summarised in Figure 3A.

Figure 3A

WoVG agreements in audit scope

|

Central agreement |

Details |

Supplier services |

Overseen by |

Approximate 2017–18 and 2018–19 spend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

SS SPC |

Contractors providing services from eight master vendors (suppliers) Includes fixed-term, permanent and executive contractors |

|

DTF |

$784 million |

|

PAS SPC |

Consultants providing professional advice and consultancy services from 199 suppliers |

|

DTF |

$173 million |

|

eServices register |

Contractors providing a broad range of services from 1 376 suppliers |

|

DPC |

$235 million |

Source: VAGO, based on information provided by DPC and DTF.

We also considered direct engagement of contractors and consultants outside the WoVG agreements.

3.3 Screening consultants and contractors

Contractual obligations

WoVG agreements are designed to streamline procurement processes and provide consistent engagement terms and conditions.

The three WoVG agreements we looked at include general supplier obligations—such as providing suitably qualified contractors and consultants—and obligations to conduct any security requirements specified by the government agency. They do not include mandatory screening obligations for the supplier.