Planning, Delivery and Benefits Realisation of Major Asset Investment: The Gateway Review Process

Overview

Budgeted expenditure on government capital projects for 2012–13 was $8.5 billion. The community expects that this investment is well managed to deliver assets that are needed, on time and on budget.

The Gateway Review Process (GRP) was introduced in 2003 to improve project selection, management and delivery. The GRP involves short, intensive, independent reviews at six critical points or 'Gates' in the project life cycle. The GRP is a valuable concept capable of assisting better performance in project delivery and has been mandatory for all high-risk projects since 2003.

However, the implementation of the GRP in Victoria reflects a number of missed opportunities. The audit identified 62 projects valued at $4.3 billion that were not included in the GRP between 2005 and 2012. The GRP was largely applied on an opt in decision by agencies and not all high-risk projects were subject to review. As a result, the fundamental objective for the GRP to improve the management and delivery of significant projects has not been fully met. The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) has demonstrated a more rigorous approach to project identification since late 2010 under the government’s ‘High Value High Risk’ process, although shortcomings remain.

Further missed opportunities resulted from projects commencing the GRP, only to drop out after completing a few Gates, meaning that the benefits from applying the GRP have not been fully realised. DTF has also missed opportunities to use the GRP to build public sector project management and review capability.

In addition, DTF has not measured the impact of the GRP on projects. As a result, it cannot make an informed assessment of the overall contribution of the GRP to improving project delivery by agencies.

Planning, Delivery and Benefits Realisation of Major Asset Investment: The Gateway Review Process: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2012

PP No 224, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Planning, Delivery and Benefits Realisation of Major Asset Investment: The Gateway Review Process.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

8 May 2013

Audit summary

The total value of investment in government capital projects—including public private partnerships—underway in 2012–13 was around $41 billion. Budgeted expenditure on capital projects for 2012–13 was $8.5 billion. Given that renewing infrastructure is a key government priority, significant investment is expected to continue.

The community expects that this investment is well managed to deliver projects that provide the assets that are needed, on time and on budget.

The government introduced the Gateway Review Process (GRP) in 2003 to improve project selection, management and delivery. The GRP involves short, intensive reviews by a team of reviewers independent from the project at six critical points or 'Gates' in the project life cycle. The reviews provide a checkpoint that projects are on track before continuing to their next stage.

The GRP has been mandatory for all high-risk projects since 2003, and for projects that are considered high risk or high value (over $100 million) since 2011. Since the introduction of the GRP, almost 500 reviews have been undertaken on around 240 projects.

The audit examined the Department of Treasury and Finance’s (DTF) management and administration of the GRP, and the contribution of the GRP to improving the management and delivery of major asset projects.

Conclusions

The GRP is a valuable concept capable of assisting better performance in project delivery. DTF provides high-quality materials to guide participation in the GRP and has effective processes in place to select, engage and train Gateway reviewers. While participation in the GRP does not guarantee project success, agencies report that the reviews are high quality and assist in delivery of their projects.

However, the implementation of the GRP in Victoria reflects a number of missed opportunities. The audit identified 62 projects valued at $4.3 billion that were not included in the GRP between 2005 and 2012. In late 2010 the government introduced the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process to improve scrutiny of high value and high risk asset investments. DTF's management of the GRP prior to the introduction of the HVHR process did not adequately recognise that some agencies may seek to avoid the GRP.

DTF cannot demonstrate that over that period it actively and consistently identified projects that may have been candidates for the GRP. This meant the process was largely applied on an opt in decision by agencies and not all high-risk projects were subject to review. As a result, the fundamental objective for the GRP—to improve the management and delivery of significant projects—has not been fully met.

However, since the introduction of the HVHR process in late 2010, DTF has demonstrated a more rigorous approach to project identification, although some shortcomings remain.

Further missed opportunities resulted from projects commencing the GRP, only to drop out of the process after completing a few Gates. No single project has completed the full suite of Gateway reviews since its introduction in 2003. This means that the benefits from applying the GRP have not been fully realised.

DTF has not measured the impact of the GRP on projects. It has not tracked agency action taken on Gateway recommendations, which is a fundamental success indicator for the GRP, and so cannot demonstrate whether the GRP has resulted in any benefit to individual projects. This has been partially addressed for projects under the HVHR process, but the new approach covers the most significant recommendations only.

Further, DTF does not use information available to it to measure whether the GRP affects project delivery, including the impact on timing, budget and scope compared to planned outcomes and benefits. As a result, it cannot make an informed assessment of the overall contribution of the GRP to improving project delivery by agencies. DTF has estimated benefits across projects from the GRP based on extrapolated anecdotal impact measures from other jurisdictions and a model that includes a number of assumptions, including that all Gateway recommendations are actually actioned. It has not validated these assumptions nor confirmed the reasonableness of simply applying other jurisdictions' impact estimates to the Victorian GRP.

Finally, DTF has missed opportunities to use the GRP to build public sector project management and review capability. It has not done enough to capture and share lessons learned from Gateway reviews and the participation of public sector staff as Gateway reviewers is very low. The need to address these issues is consistent with a recent report from the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee (PAEC) which called for a range of changes to ensure that Victoria has the necessary expertise and capability to deliver major infrastructure projects successfully.

Findings

Compliance with the Gateway Review Process

Many projects which would have benefited from Gateway review have not been included in the process. The GRP has been mandatory for all high-risk projects since August 2003 but DTF has not been effective in making sure that this requirement was complied with.

DTF has not done enough to make sure the GRP is capturing all the projects intended. In particular, it has not systematically reviewed and verified agency self-assessments of project risk, which determine whether projects are subject to the GRP. In many cases, responsible departments and agencies have not undertaken the required GRP risk assessment. DTF has not used information available to it to identify the projects likely to be high risk. Other jurisdictions using Gateway reviews are more rigorous in this area.

The onus has been on departments and agencies to opt in to the GRP. The audit identified many projects which have avoided the GRP despite clear indications that they should have been at least assessed for review.

By definition, the opt in arrangement allowed departments and agencies to opt out. Consequently, many projects escaped review due to initial resistance from departments to the process, despite the high risk of those projects and potential benefits from the GRP. In addition, none of the projects commencing the GRP have completed all six Gates. The opt in nature of the process also allowed agencies to simply withdraw, and many withdrew after completing only the first two Gates. To date, nearly 70 per cent of projects reviewed have completed two or less Gates. Partial review is inconsistent with the GRP policy, as project risk continues throughout the project life cycle. As a result, the potential benefits of the GRP have not been realised.

Flaws in the implementation of the GRP have been significantly addressed under the newly introduced HVHR process. It has linked Gateway reviews to key project approval points and mandated that projects costing over $100 million, and/or assessed as high risk, must be reviewed at all six Gates. This has given the GRP greater status and provided DTF with more leverage to address the risk that projects under the HVHR umbrella seek to avoid review. DTF is now more rigorous in identifying projects requiring Gateway review.

However, determining whether a project is high risk still partly relies on agencies self‑assessing project risk. Continuing reliance on agency self-assessments of risk to determine which projects are subject to the GRP is a weakness that has not been fully addressed by the HVHR process. DTF is not actively requiring agencies to complete these self-assessments and it cannot demonstrate that it reviews the adequacy of the departmental self-assessments that are submitted. This is not consistent with the GRP policy intent or practice in other jurisdictions.

Management of the Gateway Review Process

DTF has comprehensive guidance material to assist agency understanding of the GRP, and coordinates Gateway reviews efficiently.

However, quality assurance processes to support the correct and consistent application of the GRP methodology are not fully effective. As a consequence, significant reliance is placed on the professionalism and expertise of the GRP reviewers who are only required to attend a one-off training program.

Governance and oversight of the GRP has weakened in recent years. The interdepartmental Gateway Supervisory Committee has been disbanded and regular reporting to government on Gateway activity has ceased.

DTF relies heavily on the availability, expertise and professionalism of external consultants to conduct Gateway reviews, and is not meeting its target for 50 per cent of all reviewers to be public sector employees. In 2011–12, only 17 per cent of Gateway reviewers were public sector employees. Participation in Gateway reviews by public sector staff is intended to contribute to the broader development of project management capability in government. There are no clear strategies to increase the utilisation of public sector officers as Gateway reviewers.

The December 2012 report by PAEC on its Inquiry into Effective Decision Making for the Successful Delivery of Significant Infrastructure Projects also highlighted the need for additional action to ensure Victoria has the necessary expertise and capability to deliver major infrastructure projects successfully. DTF has missed opportunities to use the GRP to build and support greater capability in this area.

Impact of Gateway reviews

Gateway reviews were intended to provide independent robust assessments and advice to project owners and managers, and assurance to government of improved project management and delivery.

DTF cannot demonstrate that the objectives and benefits envisaged for the GRP are being realised.

Impact on individual projects

DTF cannot demonstrate whether the GRP has contributed to improved project outcomes. It does not use information available to it to measure whether the GRP affects project delivery, including the impact on the performance of reviewed projects against approved time, budget and scope parameters, and has only recently commenced tracking agency action in response to critical Gateway recommendations.

Realising the benefits available from applying the GRP to a project over its life cycle depends largely on the level of acceptance and engagement in the process by senior departmental and agency staff. Agencies usually engage openly in the process and act on review recommendations, but this is not always the case. The impact of the GRP is limited when agencies do not adequately respond to the GRP recommendations.

DTF previously claimed cost savings directly attributable to the GRP of at least $1 billion but cannot demonstrate that these benefits were reliably measured. The reasonableness of assumptions underlying these savings estimates are questionable because they rely on Gateway reviews identifying all problems, and agencies implementing all recommendations, and on simply extrapolating anecdotal impact measures from other jurisdictions. DTF does not track the implementation of Gateway recommendations, other than critical recommendations for projects included in the relatively new HVHR process.

Participation in the GRP does not guarantee success. There are multiple examples where projects completed a series of Gateway reviews but failed to be delivered on time, on budget and/or did not deliver the outcomes and benefits expected when funding was approved.

Assurance to government

DTF has previously not made the results of Gateway reviews available to government when considering the status of major projects in order to encourage agencies to be 'free and frank' in sharing information with Gateway reviewers. This has been addressed because the new HVHR process links the GRP to key project approval points and enables government to be better informed about the results of Gateway reviews when making decisions.

Lessons learned from the Gateway Review Process

DTF’s analysis and sharing of lessons learnt through the GRP to improve the capability of project management in government has been minimal. A newly developed database of lessons learned from Gateway reviews in Victoria and other jurisdictions is overdue for release, and the version being piloted has limitations in providing access to information that is clearly relevant and useful.

Recommendations

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- systematically validate whether projects should be subject to Gateway review, by verifying that robust project risk assessments are completed for new projects

- re-establish an oversight committee for the Gateway Review Process and report regularly to government on Gateway activity and impacts

- strengthen Gateway Review Process quality assurance processes

- track and report on the impact of the Gateway Review Process on improving the outcomes of completed projects

- actively monitor agency action in response to Gateway review recommendations

- complete the database for sharing lessons learned from Gateway reviews and build case studies to better demonstrate key lessons.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Treasury and Finance and the Department of Premier and Cabinet with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The total value of Victorian Government investment in capital projects, including public private partnerships, underway during 2012–13 was around $41 billion. Budgeted expenditure on capital projects for 2012–13 was $8.5 billion. Such a substantial investment requires effective project management to deliver projects that are fit for purpose, on time and on budget.

The Gateway Initiative was introduced in 2003 to improve project selection and delivery in Victoria and comprised:

- multi-year strategies to provide a long-term view of asset investment projects

- project life cycle guidance materials

- the Gateway Review Process (GRP)

- reporting to government on major asset investments.

The GRP was promoted as an important government action to improve the management and delivery of the state’s most significant projects and programs. It involves short, intensive reviews at six critical points in the project life cycle by a team of reviewers external to the project. The reviews aim to provide confidential advice and assurance to project owners on its progress against specified criteria, and early identification of areas requiring corrective action. These review points are referred to as ‘Gates’, as a project should not proceed to its next stage until each review Gate has been completed.

The GRP is managed by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF).

In late 2010 the government introduced the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process to improve scrutiny of high value and high risk asset investments. The HVHR process builds on the GRP but has important differences. While it incorporates mandatory review of projects using the GRP, it also requires agencies to obtain approval from the Treasurer to proceed at key project decision points and to submit a Recommendation Action Plan dealing with key recommendations resulting from Gateway reviews.

1.2 The Gateway Review Process

The GRP was developed in the United Kingdom (UK) during the late 1990s. It was adapted by Victoria and introduced in 2003 to assist departments and agencies improve the management and delivery of significant projects and programs. Figure 1A shows the six review Gates that form part of the GRP.

Figure 1A

Overview of Gateway review Gates

Gate |

Description/purpose |

|---|---|

1 – Strategic assessment |

Undertaken in the early stages of a project’s lifecycle to confirm that the project outcomes and objectives contribute to the overall strategy of the organisation, and effectively interface with the broader high level policy and initiatives of government. |

2 – Business case |

Confirms the business case is robust, i.e. it meets the business need, is affordable, achievable and is likely to obtain value for money. |

3 – Readiness for market |

Confirms the business case once the project is fully defined, confirms the objectives and desired outputs remain aligned, and ensures the procurement approach is robust, appropriate and approved. |

4 – Tender decision |

Confirms the business case including the benefits plan once the bid information is confirmed, checks the required statutory and procedural requirements were followed and that the recommended contract decision is likely to deliver the specified outcomes on time, within budget, and provide value for money. |

5 – Readiness for service |

Tests project readiness to provide the required service by confirming the current phase of the contract is complete and documented, the contract management arrangements are in place and current, and the business case remains valid. |

6 – Benefits realisation |

Examines whether the benefits as defined in the business case are being delivered. |

Program review |

Designed specifically for large programs of work or interrelated projects. Provides a means of reviewing the progress of individual stages, phases and milestones of projects within the program whilst ensuring coherence and focus on the overall program outcomes. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from Department of Treasury and Finance information.

At each Gate the review is aimed at:

- assessing the project against its specified objectives at the particular stage in the project’s life cycle

- identifying early the areas that may require corrective action

- validating that a project is ready to progress successfully to the next stage.

Gateway reviews are typically undertaken over three or four days by a team of reviewers external to the project. The Gateway review teams typically examine relevant project documentation and interview project owners, project teams and other key stakeholders. DTF's policy and guidance material for the GRP provides review teams with check lists of documents that should be reviewed and questions that should be asked at each Gate.

A Gateway review is not an audit, a detailed technical review or an inquiry. It is not intended to be a substitute for rigorous project governance and management processes in departments and agencies. Gateway reviews are intended to identify and focus on issues that are critical to project success.

The product of a Gateway review is a confidential report to the Senior Responsible Owner (SRO) nominated by the agency as the person responsible for delivery of the project or program. SROs are typically not the project director, they are the senior executive to whom the project director reports. A Gateway report is intended to provide the SRO with an independent view on the current progress of the project or program and recommendations.

A Red/Amber/Green (RAG) rating is used in Gateway reports to indicate the overall assessment of the project. Until 2010, the traffic light system related to the urgency of addressing report findings. This has now changed to relate to the review team's confidence that project outcomes will be delivered. Individual recommendations in Gateway reports are also assigned a RAG status.

The confidentiality of Gateway reports has been a core principle underpinning GRP policy. Only two copies of the Gateway report are retained—one for the SRO and one for DTF so it can capture lessons learned. SRO consent is required to release Gateway reports to other parties. However, in line with developments in other jurisdictions, this principle is being gradually relaxed as the results of Gateway reviews are used more transparently to provide assurance to governments on the management of major projects.

When introducing the GRP in 2003, the then government mandated the process for all programs and projects that are assessed as high risk with a total estimated investment above $5 million, requiring these to be reviewed at all six Gates. There have been over 493 Gateway reviews on more than 240 projects and programs since 2003.

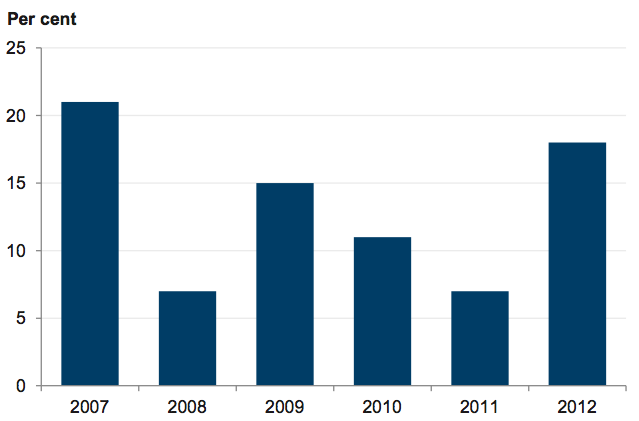

Figure 1B shows the number of Gateway reviews undertaken in each of the calendar years 2007–12 by Gate. A total of 340 reviews were undertaken over this period.

Figure 1B

Gateway reviews 2007–12 by Gate

Gate |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

Percentage of all reviews 2007–12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1. |

12 |

11 |

20 |

8 |

17 |

9 |

23 |

2. |

16 |

23 |

17 |

13 |

10 |

14 |

27 |

3. |

7 |

12 |

13 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

13 |

4. |

5 |

7 |

7 |

8 |

2 |

5 |

10 |

5. |

0 |

3 |

10 |

3 |

4 |

8 |

8 |

6. |

4 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

0 |

4 |

Program review |

9 |

12 |

4 |

13 |

7 |

5 |

15 |

Total |

53 |

70 |

74 |

53 |

46 |

44 |

100 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

DTF’s coordination of Gateway reviews includes:

- identifying projects meeting the criteria for inclusion in the GRP

- selecting, training, appointing and coordinating the Gateway Review Teams

- developing guidance to support agencies

- disseminating lessons learned from Gateway reviews.

Agencies are not required to pay for Gateway reviews but there is a time and resource cost in participating.

The UK Government provided assistance and ongoing support and advice to DTF during the initial implementation of the GRP and in 2008 formally approved Victoria as an Authorised Gateway User. This meant that the UK Government was satisfied that DTF had demonstrated its capability to deliver Gateway reviews in line with Gateway principles and standards. Victoria was the first jurisdiction granted this status.

The GRP has been introduced by a number of other Australian jurisdictions during the past decade including the Commonwealth, New South Wales, Queensland and Western Australia. International adopters of the process include New Zealand and the Netherlands. DTF has supported the introduction and ongoing development of the GRPs across jurisdictions in Australasia by providing leadership, guidance, and support.

The GRP was not initially intended to be an accountability mechanism, but rather to provide an independent assessment of project health to the department or agency responsible for delivering the project. Changes introduced as part of the HVHR process now require agencies to advise the Treasurer of actions in response to all Red-rated recommendations identified in Gateway reports on HVHR projects.

1.3 The High Value High Risk process

Concern about cost overruns on significant public sector projects, including some which had been Gateway reviewed, led the government to introduce the HVHR process in December 2010 to increase oversight and scrutiny of these investments. The HVHR process includes mandatory Gateway review at all six Gates and Treasurer's approval prior to key project decision points, including finalising the business case, releasing procurement documents, selecting the preferred bidder and signing contracts. The HVHR process is modelled on enhanced major project assurance processes introduced in the UK at around the same time.

HVHR investments are defined as projects meeting one or all of the following criteria:

- a total estimated investment of $100 million or more

- identified as high risk and/or highly complex

- considered by government to warrant greater oversight and assurance.

The only substantive difference between the initial GRP and the HVHR process is that the HVHR process requires projects costing above $100 million to go through the GRP regardless of assessed risk level, whereas the GRP would only have been required for a project if it was assessed as high risk.

Projects costing less than $100 million, but assessed as high risk, are also included in the HVHR process and are subject to mandatory review under the GRP, as was always the case. Figure 1C shows the criteria used to select projects for review under the GRP before and after the introduction of the HVHR process.

Figure 1C

Criteria used to select projects for the Gateway Review Process before and

after introduction of the High Value High Risk process

Risk level |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

Value $100 million and above |

|||

Before introduction of HVHR process |

GRP not required |

GRP mandatory for prioritised projects and optional for the other projects |

GRP mandatory |

Now |

HVHR projects (subject to the GRP) |

HVHR projects (subject to the GRP) |

HVHR projects (subject to the GRP) |

Value under $100 million and above $5 million |

|||

Before introduction of HVHR process |

GRP not required |

GRP mandatory for prioritised projects and optional for the other projects |

GRP mandatory |

Now |

HVHR not applicable |

HVHR not applicable |

HVHR applicable |

Value under $5 million |

|||

Before introduction of HVHR process |

GRP not required |

GRP not required |

GRP not required |

Now |

HVHR not applicable |

HVHR not applicable |

HVHR applicable |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The HVHR process has introduced more intensive review of projects by DTF and requires separate Treasurer’s approval at key decision points such as the final business case and release of procurement documentation. These key decision points are aligned with the relevant GRP Gates, giving Gateway reviews greater status than before the introduction of the HVHR process.

DTF is currently developing options for government consideration to amend the GRP/HVHR policies including the introduction of Project Assurance Reviews (PAR). The proposed enhancements to major project assurance processes are based on developments in the UK. The proposal to introduce PARs during the project delivery phase for HVHR projects would complement the GRP by addressing what can be a long gap between Gate 4 Tender Decision and Gate 5 Readiness for Service. The UK implemented PARs around 18 months ago.

Since December 2010, 49 Gateway reviews have been conducted on HVHR projects.

1.4 Recent assessments of the Gateway Review Process

Recent reports released by VAGO, the Victorian Ombudsman and the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee (PAEC) of Parliament have commented on the effectiveness and management of the GRP.

1.4.1 Learning Technologies in Government Schools

VAGO’s audit report Learning Technologies in Government Schools was tabled in Parliament in December 2012.

This report found that the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development’s Ultranet project received a ‘Red’ rating for four of the five Gateway reviews conducted during the planning phase. Despite this, in all instances, the project proceeded to the next phase with little evidence that issues identified were rectified and recommended actions were implemented. Specifically, the audit found that the department did not adequately address more than 60 per cent of the recommendations in the Gateway reviews for the planning phase of the project.

1.4.2 Information communication technology-enabled projects

In November 2011, the Ombudsman reported on an Own Motion Investigation Into ICT-Enabled Projects. The investigation was undertaken in consultation with VAGO.

The report found that some review recommendations were addressed but others were ignored and there was a lack of accountability by those responsible for project outcomes. The Ombudsman concluded that the effectiveness of the GRP was limited by DTF’s reliance on agencies engaging in and being supportive of the process, which often was not the case.

The Ombudsman observed that DTF seemed to view its role as simply making the GRP available, but had not capitalised on the value of the GRP as a mechanism for external oversight and accountability.

1.4.3 Inquiry into Effective Decision Making for the Successful Delivery of Significant Infrastructure Projects

PAEC released the report on its Inquiry into Effective Decision Making for the Successful Delivery of Significant Infrastructure Projects in December 2012.

PAEC found that the:

- The GRP ‘provides a mechanism for ensuring that lessons learnt are identified—however, many projects are not being comprehensively 'put through' the process…’

- failure of agencies to use the pre–HVHR GRP is an example where DTF has devolved responsibility to departments to implement best practice guidelines, but not monitored this.

PAEC identified the need for a stronger and more reliable mechanism to ensure that infrastructure projects are consistently delivered in line with the high standard articulated in policy documentation and associated guidance. PAEC noted that this requires monitoring of whether or not the guidance—including that related to GRP—is adhered to, and the required action is taken when it is not.

1.5 Audit objective and scope

This audit assessed the effectiveness and efficiency of GRP. This involved assessing:

- DTF’s management and administration of GRP

- the contribution of GRP to improving the management and delivery of major asset projects.

The audit examined the management and administration of the GRP, including the systems and processes used to identify projects for review, and the conduct, timing, cost and resourcing of reviews. It analysed data on all Gateway reviews undertaken between January 2007 and December 2012. In addition, a sample of projects reviewed over that six-year period were examined to assess whether the GRP assisted agencies to better manage projects.

The audit examined the relationship and interaction between the GRP and the HVHR project assurance framework. It also examined DTF’s broader role in developing and disseminating lessons learned from Gateway reviews.

1.6 Audit method and cost

The audit method included:

-

review of:

- the GRP policy and guidance material for Victoria and other jurisdictions

- relevant DTF files, records and information including all Gateway reports issued between January 2007 and December 2012

- relevant Cabinet-in-Confidence documents covering the period 2002–12

- evidence from departments and agencies on responses to Gateway reviews of sampled projects.

-

interviews with:

- officers from DTF and relevant departments and agencies

- a sample of Gateway review team leaders and team members

- managers of the GRPs in other Australian and international jurisdictions.

The audit was performed in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost was $400 000.

1.7 Structure of the report

- Part 2 assesses DTF's management of the GRP

- Part 3 examines the impact of the GRP.

2 Management of the Gateway Review Process

At a glance

Background

The Gateway Review Process (GRP) was introduced in 2003 and is managed by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF). It comprises project assessment at six key milestones or 'Gates', and is mandatory for all high-risk projects.

Conclusion

Not all high-risk projects have been subject to the GRP and, for those that have, not all have been assessed at all six Gates. This represents a significant missed opportunity to use the GRP to improve project delivery across government.

Findings

- DTF has not had an effective process for ensuring that every project meeting the criteria for Gateway review has been identified and reviewed. Application of the GRP has relied on an opt in decision by agencies.

- Projects commencing the GRP have dropped out of the process rather than being progressed through all six Gates. This means that the benefits from the GRP are not fully realised.

- For projects over $100 million, the newly introduced High Value High Risk process should address the issue of agencies opting out of GRP completely or not completing all six Gates. However, there remains the risk that high-risk projects below this value will not be identified for review.

Recommendations

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- systematically validate whether projects should be subject to Gateway review, by verifying that robust project risk assessments are completed for new projects

- re-establish an oversight committee for the Gateway Review Process and report regularly to government on Gateway activity and impacts

- strengthen Gateway Review Process quality assurance processes.

2.1 Introduction

The Gateway Review Process (GRP) is mandatory for all high-risk projects. Compliance with the GRP for these projects was mandated because Gateway reviews were intended to provide:

- independent robust assessments and advice to project owners and managers

- assurance to government of improved project management and delivery.

There should be appropriate processes in place to identify all projects meeting the criteria for review under the GRP.

The Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) role in managing GRP includes: identifying projects meeting the criteria for inclusion in the GRP; selecting, training, appointing and coordinating review teams; developing guidance to support agencies; and disseminating lessons learned from Gateway reviews. Gateway reviews are provided at no cost to agencies, although there is a time and resource cost in participating.

This Part of the report assesses compliance with the GRP’s intended scope and DTF's management of the GRP.

2.2 Conclusion

The GRP was one element of the Gateway Initiative introduced in 2003 to improve the delivery of government projects. The individual elements of the Gateway Initiative were not implemented in an integrated way. DTF did not actively coordinate the elements to ensure timely and comprehensive identification of projects for inclusion in the GRP. In part, this was because the various components of the Gateway Initiative were managed by different divisions within DTF, however, recent organisational changes have largely addressed this.

DTF cannot demonstrate that it has actively and consistently identified projects that may be candidates for the GRP, therefore the process has largely been applied on an opt in decision by agencies. As a result, not all high-risk projects have been subject to review, and the fundamental objective for the GRP to improve the management and delivery of significant projects has not been fully achieved. DTF has demonstrated a more rigorous approach to project identification since the introduction of the High Value High Risk (HVHR) process in late 2010, although some weaknesses remain.

Projects that commence the GRP often drop out of the process after completing only some of the Gates. No single project has completed the full suite of Gateway reviews since its introduction in 2003. This means that the benefits from applying GRP are not fully realised.

Governance and oversight of the GRP has weakened in recent years as the interdepartmental Gateway Supervisory Committee has been disbanded and regular reporting to government on Gateway activity has ceased.

2.3 Compliance with the Gateway Review Process

The extent to which the GRP is used and generates benefit is influenced by a range of factors, including:

- engagement of senior agency staff

- perception of its value

- the maturity of the agency’s governance and project management processes

- agency capacity and willingness to improve their project management and associated processes.

These factors influence the extent to which agencies engage and potentially benefit from the GRP.

Under the approved Gateway principles, departments and agencies are required to complete a Project Profile Model (PPM)—a project risk assessment tool—for all projects and programs with a total estimated investment of $5 million or more. Projects assessed as high risk under the PPM or by government must be subject to the GRP.

2.3.1 Introduction of the Gateway Review Process

The GRP commenced in August 2003 as part of the Gateway Initiative, a suite of integrated processes designed to provide a new project development, management and review framework across the public sector to deliver better value for government asset investments. The Initiative included four elements:

- forward planning on capital projects

- guidance materials on business case development

- the GRP

- regular reporting to government on the status of capital projects.

There was a transition to the GRP during preparation for the 2004–05 State Budget as project risk levels were assessed. The government decided that following the 2004–05 Budget process the GRP would be mandatory for all new high-risk projects and prioritised medium-risk projects.

2.3.2 Initial resistance to the Gateway Review Process by departments

An obvious implementation risk was that the new GRP would be actively avoided by some departments and agencies during the early stages of its implementation.

DTF's communication strategy for the introduction of the Gateway Initiative was partly successful in building understanding and acceptance across government departments. However, the implementation of the GRP met with some resistance when first implemented.

Advice from the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) to government in July 2004 indicated that:

- the level of compliance with the GRP varied across departments with some departments not utilising the GRP to a significant extent and adopting a wait and see approach

- the former Department of Infrastructure (DoI) had the largest asset investment program but was seeking exemption from the GRP on the grounds that it duplicated DoI's internal project review processes

- there was a lack of clarity around the project selection process for the GRP because the PPM used to assess risk and whether a project should be reviewed by Gateway, was not consistently applied to all projects

- a balance was required between GRP acting as a learning tool and departments being accountable for the GRP results.

In August 2004, the government confirmed the Gateway Initiative as a whole‑of‑government process that required all departments to adopt its four elements. A subsequent review in 2006 indicated that the Gateway Initiative was more broadly supported across departments than in 2003.

Reports to government from the Gateway Supervisory Committee in December 2007 and June 2008 on GRP implementation indicated that inconsistent use of the PPMs across government meant that some high-risk projects were entering the GRP after Gate 1. This was a lost opportunity because the Gate 1 review examines the alignment of planned project outcomes and objectives with government and organisational strategies and policy goals. This is considered to offer the greatest opportunity to impact on the success of projects.

Participation in the Gateway Review Process by departments

During the early years of the GRP, the Department of Human Services consistently had the highest number of projects participating in the GRP. Although the then Department of Education and Training (DET) managed the highest proportion of government projects in terms of number of projects, its projects accounted for only a small percentage of projects reviewed through the GRP. This was largely due to DET managing a significant number of lower-value projects.

Of the 21 projects reviewed under the GRP to July 2004, only two were managed by DoI (now the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure), and only one related to the Department of Justice. The level of engagement by these departments in the early stages of the GRP was disproportionately low compared with their significant shares of capital project delivery across government.

2.3.3 Weaknesses in identifying projects for Gateway review

DTF has not had an effective process for identifying projects meeting the criteria for Gateway review.

The GRP policy and guidance material has consistently indicated that, while there is an onus on agencies to self-assess project risk levels, DTF would not be a passive observer. Part of DTF's role in managing the GRP is to actively identify projects that may require review by evaluating agency completed project risk assessments.

DTF has not done this systematically and consistently. The GRP has been applied on an opt in basis by agencies. As a result, many projects have not been reviewed under the GRP because departments and agencies did not submit a risk assessment to DTF for confirmation that Gateway reviews were not required.

The HVHR process should address the issue of agencies avoiding the GRP completely or not completing all six Gates. DTF has demonstrated a more rigorous approach to project identification since its introduction. However, the continuing reliance on agency self-assessments of project risk to determine which are subject to the GRP remains a weakness that has not been adequately addressed by the HVHR process.

The Project Profile Model and its application

The GRP was intended to focus on higher value projects with high risk. Since 2003, project risk has been a key factor in determining whether a project requires review under the GRP.

Determining initial project risk relies on agencies completing the PPM, a risk profile assessment tool developed by DTF based on the project risk assessment tool used in the GRP in the United Kingdom (UK). The risk assessment is intended to reflect the anticipated complexity, criticality and level of uncertainty of a project and its delivery. Agencies are required to use the PPM to record a self-assessment of risk for all projects where the total estimated investment exceeds $5 million, and submit these to DTF.

Compliance with this process is not monitored effectively. DTF oversight is not transparent as it has not maintained comprehensive records of the PPMs received or evidence of their review. Inconsistent submission of the PPMs across government was noted as still being an issue by the Gateway Supervisory Committee as late as 2008. In practice agencies chose whether to opt in to the GRP up until the HVHR process was introduced in late 2010.

In 2006 DPC reviewed the GRP and flagged the potential for agencies to manipulate the PPM tool to avoid the GRP. DPC recommended that a senior agency executive be required to sign off on the final PPM submitted for each project. This recommendation was implemented. However, an internal review of DTF's management of the GRP in 2010 found that 70 per cent of the PPMs examined had not been signed off by a senior agency executive responsible for the project.

DTF has progressively refined the PPM and supporting guidance in response to specific reviews and feedback from users. These refinements have been designed to reduce the capacity for agencies to manipulate the PPM results, and improve user understanding, functionality and accuracy:

- In 2010 a new version of the PPM was released, superseding the PPM in place since 2003. However, this did not address the potential for manipulation and fewer projects were assessed as high risk using this new PPM.

- The PPM was reissued again in late 2012 following a review in April 2011. This PPM better addresses the potential for manipulation by hiding the project risk score from agencies.

The April 2011 review recommended that DTF develop more comprehensive guidance material with a particular emphasis on defining intermediate risk ratings. DTF did not act on this recommendation.

Determining whether a project is subject to the GRP should not be at the sole discretion of departments and agencies. GRP implementation material indicated that DTF would review and validate agency self-assessments of project risk. It also indicated that agencies would be required to submit risk assessments to DTF for all projects assessed as medium and high risk. DTF's role in reviewing and validating self‑assessments of project risk levels was still featured in training material for the GRP in 2011.

The 2006 DPC review of the Gateway Initiative indicated that DTF was validating the PPM results at that time. This practice ceased sometime after 2006 and DTF could not demonstrate any systematic, consistent review of the PPMs it received. This contrasts other jurisdictions where agency self-assessments are reviewed and amended as necessary. The Commonwealth and New Zealand actively review and validate project risk self-assessments and this results in changes to risk ratings. The New South Wales Treasury does not rely on agency self-assessments of project risk to determine whether the GRP is applied to a project.

The Australian National Audit Office audit of the Commonwealth GRP indicated that between 2006–07 and 2010–11 the Department of Finance changed agency self‑assessments of project risk levels in around 19 per cent of cases, with 73 per cent of these changes resulting in an increased risk rating. As a result, 27 (42 per cent) of the 64 projects required to participate in the GRP during this period were only included as a result of the Department of Finance's revision to the indicative self‐assessed rating of the project’s sponsoring agency.

To date, DTF has not sought assurance that the PPM risk assessments are a reliable indicator of project risk by analysing how often projects that were allocated a low or medium risk rating were not delivered in a timely and effective manner. In addition, there is no process requiring projects to be re-assessed to determine any changes in risk level during the course of the project. If project risk increases, Gateway reviews are unlikely to occur unless initiated by the agency, which is rare.

DTF cannot demonstrate that departments complete and submit a PPM assessment for all projects with a total estimated investment exceeding $5 million.

The result is that the application of the GRP has effectively relied on an opt in decision by agencies.

Other ways of identifying projects for the Gateway Review Process

The Gateway Initiative included forward planning and quarterly reporting to government on capital projects. Despite being introduced as part of an integrated package, these elements have not been actively used by DTF to assist in identifying projects for inclusion in the GRP.

The 2006 DPC review of the Gateway Initiative identified that administration of its four elements was dispersed across DTF and not centrally managed. The GRP and Business Case components were managed by the Commercial Division, and the Multi‑Year Strategy and quarterly reporting to government on capital projects, by the Budget Division. As a result DTF missed the opportunity to identify projects to, at the very least, ensure that a robust PPM had been completed and reviewed.

This audit reviewed a selection of quarterly reports to government on major asset investments between 2005 and mid–2012 to identify projects with a total estimated investment of more than $5 million that had not been reviewed under the GRP despite clear indications they should have been at least assessed for review.

This analysis highlighted 62 projects with a total value of $4.3 billion. DTF could not demonstrate that it had received and reviewed the PPMs for the vast majority of these projects. Had DTF been using the information available to it more effectively, these projects could have been identified earlier and assessed to determine whether they require review under the GRP. Figure 2A provides a breakdown by departments of the total number and value of the projects that had not been reviewed under the GRP.

DTF does not fully accept the audit analysis. It considers that there are 48 projects worth $3.9 billion which may have met the criteria for review but have not been reviewed under the GRP. However, DTF's assessment was largely based on information reported to it by departments as part of this audit, and not on information and analysis that it has consistently and systematically gathered and documented over the past seven years. DTF could not demonstrate rigorous review of the accuracy and completeness of the information reported to it by departments as part of the audit.

Figure 2A

Projects potentially bypassing the Gateway Review Process

during the period 2005 to mid-2012

Departments |

Total estimated investment $ million |

Number of projects |

|---|---|---|

Transport (previously Department of Infrastructure) |

3 438.7 |

30 |

Justice (including Victoria Police) |

272.8 |

12 |

Health and Human Services |

247.3 |

6 |

Education and Early Childhood Development |

161.1 |

6 |

Sustainability and Environment |

0 |

0 |

Planning and Community development |

86.6 |

3 |

Primary Industries |

11.7 |

1 |

Business and Innovation (previously Department of Innovation, Industry and Regional Development) |

41.0 |

2 |

Premier and Cabinet |

0 |

0 |

Treasury and Finance |

20.2 |

2 |

Total |

4 279.4 |

62 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The new High Value High Risk process

In December 2010, the HVHR process was introduced to increase oversight and scrutiny of high value and/or high-risk investments. The HVHR process includes mandatory Gateway review at all six Gates and Treasurer's approval at key project decision points.

The substantive difference between the initial the GRP selection criteria and the HVHR process is that the HVHR process requires projects above $100 million to go through the GRP regardless of assessed risk level.

The HVHR process has introduced increased review of projects by DTF and requires separate Treasurer’s approval at key decision points such as the final business case and release of procurement documentation. These key decision points are aligned with the relevant GRP Gates, giving Gateway reviews greater status than was the case prior to the introduction of the HVHR process.

Organisational changes in DTF have brought together the responsibilities for managing the GRP and preparing quarterly reports to government on the performance of major capital projects. This has improved coordination to identify projects requiring Gateway review. However, the weaknesses in the process for identifying projects requiring review under the GRP have not been fully addressed through the HVHR process due to the continuing reliance on agency self-assessments of project risk for projects below $100 million.

2.3.4 Projects not fully completing the Gateway Review Process

The principles guiding the GRP have not changed since it was introduced in 2003. One of these principles provides for projects to be subject to Gateway reviews for their entire life cycle. In other words, projects that are included in Gateway should proceed through all six Gates.

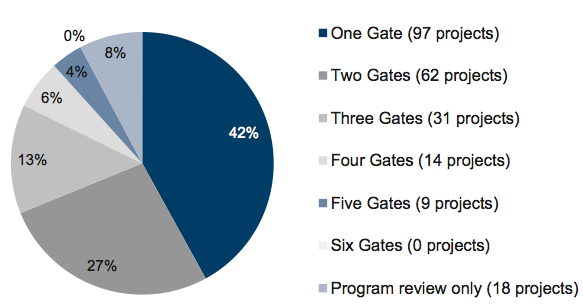

However, in practice, all projects commencing the GRP have not been assessed at all six Gates meaning that the benefits from its application have not been fully realised. To date, no single project has been reviewed at all six Gates. Only 4 per cent of projects undertaking review have completed five Gates, and 6 per cent four Gates. Nearly 70 per cent of projects reviewed have only completed either one or two Gates.

Figure 2B shows the number of Gates that projects entering the GRP have completed from its commencement in 2003 to 31 December 2012, and the percentage of projects reviewed by number of Gates completed over the period. Eighteen programs have completed one or more program reviews without going through a particular Gate review.

Figure 2B

Number of Gates completed for all projects entering

the Gateway Review Process to 31 December 2012

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on data provided by the Department of Treasury and Finance.

The data shown in Figure 2B includes projects that are still underway, which means they may progress through later Gates in future. However, the GRP has been in place for nearly 10 years and it is reasonable to expect that a greater proportion of projects would have completed four or more Gates.

In comparison, between mid-2006, when the Commonwealth Government introduced the GRP, and June 2011, around 20 per cent of the total 46 projects participating in the GRP had been reviewed at all six Gates. DTF does not keep comprehensive records on the completion status of projects that have commenced, but not completed, the full suite of Gateway reviews.

Since December 2010, projects with a total estimated investment of more than $100 million and/or projects identified as high risk through application of the Gateway PPM are required to be reviewed at all six Gates. To date, most identified HVHR projects have been reviewed at Gates 1 and 2. Some have progressed to Gate 3.

The Major Projects Performance Report to government for the June 2012 quarter identified 21 major projects requiring ongoing monitoring due to emerging risk or other issues. Of these projects:

- one project has not been reviewed at all under the GRP

- thirteen projects have missed at least one Gate

- five projects have not been reviewed in over 12 months even though the most recent GRP review rated the project Red or Amber.

2.4 Management of the Gateway Review Process

DTF established a separate Gateway Unit to manage the GRP in 2003. The Unit continues to be responsible for the implementation and ongoing administration of the GRP. During 2010–11 the Gateway Unit had an average of about seven full‐time equivalent staff. The budget for the GRP has averaged around $3 million over the past four financial years, including staff costs and the cost of engaging private sector Gateway reviewers.

2.4.1 Governance and oversight of the Gateway Review Process

There should be adequate oversight of the GRP and regular reporting to government on the GRP activities, management and impacts.

The Gateway Supervisory Committee (GSC) was established in 2003 to provide high‑level cross-departmental support and guidance for the GRP. The GSC's key terms of reference were to:

- facilitate ongoing development and refinement of the GRP

- facilitate effective targeting and resourcing of Gateway reviews

- facilitate skills transfer and communication of lessons learnt from Gateway reviews across government

- provide appropriate guidance to the Gateway Unit.

The GSC comprised a senior representative from each government department and was chaired by a person from outside the public sector. The first meeting of the GSC occurred on 18 November 2003. It was disbanded following the introduction of the HVHR policy in late 2010, with the final meeting being held in June 2011.

The Victorian Infrastructure Policy Reference Group (VIPRG) was established in September 2011. However, the VIPRG does not have a clear mandate to oversee the GRP as its terms of reference are much broader than those of the previous GSC. This has weakened strategic oversight and direction of the GRP.

Reporting on Gateway Review Process to government

As part of the approval of the GRP, government directed that the GSC report regularly to the Treasurer and the Premier on the progress of the GRP.

The GSC provided six-monthly reports to the Treasurer and government between early 2004 and the end of 2010. This reporting included information and analysis on:

- the number of reviews undertaken by Gate and department

- the incidence of Red, Amber and Green (RAG) ratings for projects reviewed, and recommendations

- the number of recommendations by lessons learned categories such as risk management, governance and stakeholder management

- the number of Gateway reviewers used, and the mix between public and private sector reviewers

- agency satisfaction levels with the GRP.

The reports did not include information on individual projects to protect the confidentiality of Gateway reviews. The reporting provided partial accountability for the GRP but did not sufficiently address compliance with the process.

In February 2011 DTF committed to continuing six-monthly reporting to government on the performance of the GRP. This commitment has not been met, and there has been no regular reporting to government since the end of 2010.

With the disbanding of the GSC, and the lack of regular reporting to government, there is now little accountability for the GRP apart from reporting within DTF.

2.4.2 Gateway Review Process policy and guidance material

A series of handbooks covering the six Gates was published as part of the initial implementation of the GRP in 2003. This material was based on the UK Gateway process guidance and DTF has periodically updated the material since 2003. In 2004, further guidance was published to assist agencies, Gateway reviewers and project teams prepare for, and participate in, Gateway reviews.

Agency feedback on the guidance material was positive. DTF is updating the GRP guidance material to reflect changes made to the implementation of Gateway since the introduction of HVHR.

DTF is currently developing options for government consideration to amend the GRP/HVHR policies, including proposing the introduction of Project Assurance Reviews (PAR) during the project delivery phase for HVHR projects. This option would complement the GRP and help address the long gap between Gates during the project delivery phase. DTF has identified that the construction or project delivery phase between Gates 4 and 5 is the time when the majority of money is invested and when major risks can emerge. The clients for a PAR will be the central agencies and government as project funder, not the agency managing the project.

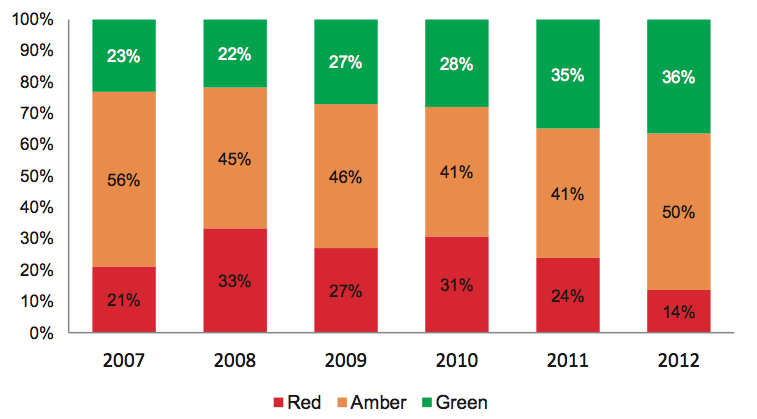

Red/Amber/Green ratings in Gateway reports

A RAG rating system has been used in Gateway reports since the GRP was introduced in 2003. This practice is consistent with most other jurisdictions. The RAG rating is used to indicate significance of issues identified in the review.

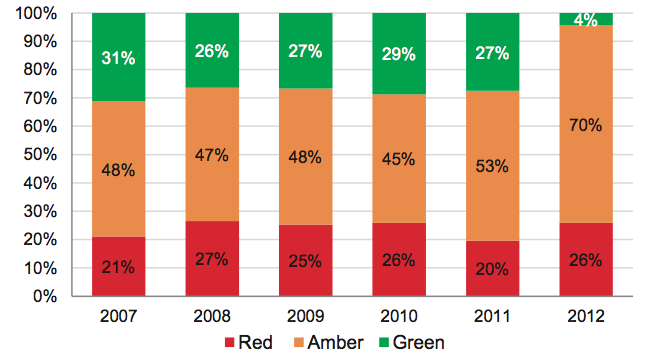

At each Gate a project is given an overall RAG rating and individual recommendations are also assigned RAG ratings. Until late 2011, the overall RAG rating for a project related to the urgency of addressing report findings. The overall rating is now based on the review team’s confidence that the project can be delivered in a timely and effective manner. Appendix A sets out the previous and current definitions for the overall project ratings. Since the change in RAG rating definition for the overall project rating in late 2011, the proportion of projects receiving Red ratings has reduced by about 50 per cent.

RAG ratings are also applied to individual recommendations in the reports on Gateway reviews. Appendix A shows the changes to RAG definitions for individual recommendations over time.

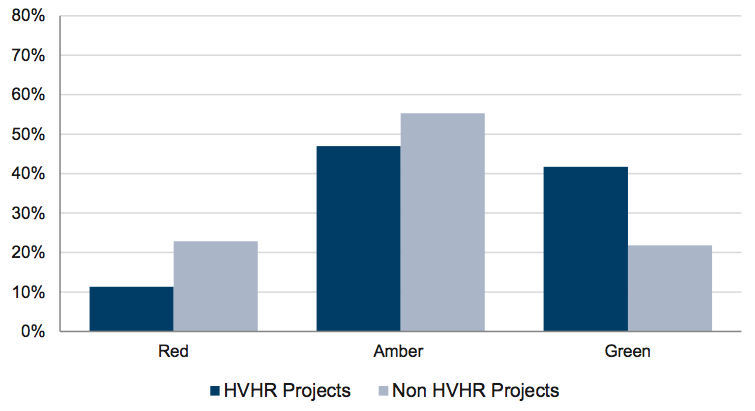

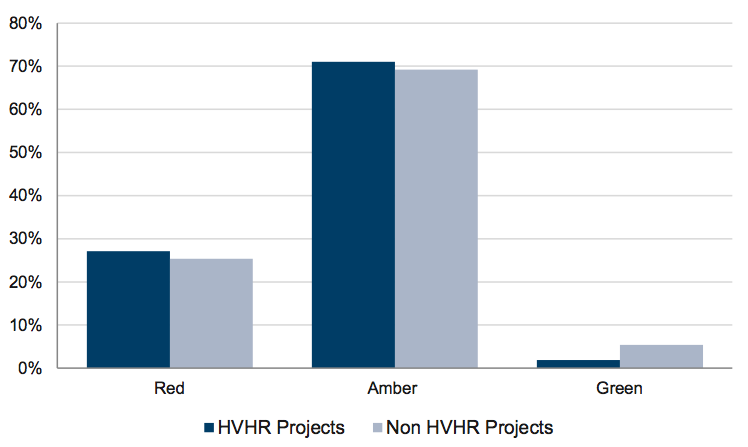

As part of the HVHR process, agencies are required to submit a Recommendation Action Plan to the Treasurer for Red-rated recommendations in Gateway review reports. Feedback provided by Gateway review team leaders indicated that there is greater sensitivity in agencies around Red-rated recommendations since the introduction of the HVHR process. Available evidence indicates that HVHR projects generally received less Red-rated recommendations than non-HVHR projects in 2011 and 2012.

2.4.3 Reviewer training, selection and engagement

In addition to cooperation from projects teams subject to review, the success of the GRP largely depends on the skills and experience of the persons engaged to lead and undertake reviews. While significant reliance is placed on the professionalism and expertise of Gateway reviewers, they are only required to attend a one-off training program to gain accreditation. There is no requirement for refresher training or professional development to demonstrate maintenance of the skills and capability to undertake reviews.

Despite having a target for 50 per cent of review team members to be public sector officers, DTF relies heavily on the availability, expertise and professionalism of external consultants to conduct Gateway reviews. During 2011–12, of the 208 reviewers used, approximately 73 per cent were consultants, 17 per cent were public sector officers and 10 per cent were from interstate or overseas. Review team leaders are almost without exception external consultants, and a small group of 12 to 14 team leaders are used frequently.

Participation in Gateway reviews by public sector officers is intended to contribute to the broader development of project management capability in government. There are no clear strategies to increase the utilisation of Victorian public sector officers as Gateway reviewers. This contrasts with other jurisdictions where strategies are evident—such as, targeting public sector officers undertaking leadership development programs for Gateway training and review participation, and including at least one public sector officer on each Gateway review team.

The December 2012 report from the Public Accounts and Estimates Committee (PAEC) on its Inquiry into Effective Decision Making for the Successful Delivery of Significant Infrastructure Projects highlighted the need for additional action to build public sector project management capacity. PAEC recommended the establishment of a new body to be a centre of excellence for project development and delivery with overall responsibility for ensuring that Victoria has the necessary expertise and capability to deliver major infrastructure projects successfully. Increasing the use of public sector staff in the conduct of Gateway reviews would also contribute to this objective.

In selecting the composition of individual Gateway review teams, including the team leader, the Gateway Unit balances a range of considerations, including:

- the experience and expertise of potential candidates

- the views of the sponsoring agency for the project

- potential conflicts of interest or other sensitivities

- relevant knowledge, skills and experience

- feedback regarding performance on previous reviews from Senior Responsible Owners (SRO) and other review team members

- a degree of continuity of review team membership

- a mix of public and private sector reviewers.

Although there are isolated examples of SROs refusing to deal with individual review team leaders or members, based on the feedback provided by agency SROs, there is generally a high level of satisfaction with the quality of the review teams conducting Gateway reviews.

The most recent review team leader’s forum was in March 2011. Review team leaders indicated a desire for more frequent forums to share knowledge, experience and challenges.

As at 31 December 2012, 1 120 people have completed Gateway training, comprising 635 from the public sector and 485 from the private sector. Only around 300 of these people are regularly used to conduct reviews.

DTF's contractual arrangements for engaging private sector reviewers are adequate.

2.4.4 Quality assurance over Gateway reviews

DTF cannot demonstrate systematic quality assurance review practices to assure that Gateway reviews are performed and reported in line with the GRP policy and guidance material.

Review of Gateway reports and discussions with both Gateway review team members and agencies, as part of the audit, indicated that compliance by Gateway review teams with the GRP policies, principles and procedures is typically strong but there is some evidence of inconsistent application of the GRP.

Other jurisdictions undertaking the GRP reported a stronger focus on quality assurance review. This includes active participation in the review process to monitor the comprehensiveness of the review and report and assessment of Gateway reports for consistency with required templates and content.

DTF's housekeeping over the GRP records and data was satisfactory with a strong records management system deployed and used. However, version and quality controls for the Gateway Unit’s long- and short-term planning databases are not sufficiently strong. This reduces the extent to which a user can be confident the data they are using is the most current or accurate. In addition, DTF lacks a unique project identifier for projects entering the GRP which makes it difficult to track some projects as their names may be changed over time.

Recommendations

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- systematically validate whether projects should be subject to Gateway review, by verifying that robust project risk assessments are completed for new projects

- re-establish an oversight committee for the Gateway Review Process and report regularly to government on Gateway activity and impacts

- strengthen Gateway Review Process quality assurance processes.

3 Impact of the Gateway Review Process

At a glance

Background

The Gateway Review Process (GRP) has been a primary element of efforts to improve the management and delivery of Victoria’s most significant public sector projects since 2003. Realisation of intended benefits depends on the quality of the Gateway reviews and the willingness of agencies to participate in the process and take appropriate actions in response to review recommendations.

Conclusion

The objectives and benefits envisaged for the GRP are not being fully realised. Although there are instances where the GRP has impacted positively on project outcomes, in other cases agencies have not adequately responded to GRP findings and recommendations to the detriment of the project.

Findings

- Most agencies were able to demonstrate sound processes to consider and act on recommendations from Gateway reviews. However, there are cases where agencies fail to act on recommendations.

- The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) has only recently commenced tracking agency action in response to Gateway recommendations.

- DTF does not measure the impact of Gateway reviews on project delivery performance against approved time and budget parameters, and so cannot demonstrate the extent to which the GRP has contributed to improved project outcomes.

- In the absence of improved tracking of projects, DTF’s estimates of significant ongoing cost savings directly attributable to the GRP are not reliable.

Recommendations

The Department of Treasury and Finance should:

- track and report on the impact of the Gateway Review Process on improving the outcomes of completed projects

- actively monitor agency action in response to Gateway review recommendations

- complete the database for sharing lessons learned from Gateway reviews and build case studies to better demonstrate key lessons.

3.1 Introduction

The Gateway Review Process (GRP) was introduced to assist with the selection and delivery of projects that are fit for purpose, on time and on budget, in accordance with their objectives and planned benefits. It was intended to assure government of effective project management and delivery, to improve project management capability across government, and identify and share lessons learned.

As manager of the GRP, the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) is responsible for measuring its impact and has claimed significant benefits and savings arising from its application. It should regularly measure the benefits and costs of projects participating in the GRP.

This Part of the report assesses the extent to which DTF can demonstrate whether the GRP has had a positive impact on individual projects, and delivered the anticipated assurance and project management capability benefits.

3.2 Conclusion

Participating in the GRP is no guarantee of successful project delivery. Many projects reviewed under the GRP were not completed on time and on budget and did not deliver the outcomes expected when funding was approved. DTF needs to better understand why this is so and use this information to improve the GRP.

DTF does not gather sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the objectives and benefits envisaged for the GRP, for both individual projects and in the public sector more broadly are being realised. It does not use information available to it to measure the extent to which Gateway reviews contribute to improved project delivery performance against approved time, budget and scope parameters. As a result, it cannot make an informed assessment of the overall contribution of the GRP to improving project delivery by agencies.

DTF’s implementation of the GRP has sought to reinforce the responsibility of individual agencies for the management and delivery of their projects. As a result, the impact of the GRP on individual projects is largely determined by the willingness of agencies to take positive action on recommendations. DTF does not track the implementation of Gateway recommendations, other than Red-rated recommendations for projects included in the relatively new High Value High Risk (HVHR) process.

DTF has not sufficiently captured and shared lessons learned from the GRP to improve the capability of project management in government.

3.3 Measuring the benefits of the Gateway Review Process

DTF identified a range of expected benefits from the GRP when it was introduced in 2003. The GRP was intended to:

- support the Senior Responsible Owners (SRO) for individual projects by providing a peer review to examine the progress and likely success of the project—this advice is intended to assist with the on time and on budget delivery of projects in accordance with their stated objectives and planned benefits

- provide broader assurance to government of improved project management and delivery within the public sector—this was to be achieved by improving knowledge and skills among public sector staff participating in reviews and sharing lessons learned.

These benefits should be reflected in positive impacts on individual projects subject to the GRP, and value through an improved project management capability across government.

DTF does not use information available to it to measure whether the GRP affects project delivery, including the impact on timing, budget and scope parameters compared to planned outcomes and benefits. However, it has claimed positive financial benefits of the GRP.

At the commencement of this audit, DTF's website included a statement that the GRP process had resulted in costs avoided of $1 billion. It subsequently removed this claim. DTF has also advised government that the GRP delivers a total cost saving of up to 29 per cent of the total investment in each project reviewed.

DTF cites value for money studies conducted in the United Kingdom (UK) and Victoria as the basis for these claims, however:

- it cannot demonstrate that it has performed any assessment of these studies to satisfy itself that they provide a sound basis for estimating the financial impact of the Victorian GRP

- the implementation of the GRP in Victoria does not fully replicate the UK Gateway process, which means it is not valid to simply extrapolate savings apparently achieved there.

There are references in a range of publications to value for money studies on the impact of the GRP in the UK that indicate that Gateway reviews deliver cost savings benefits in the order of 3 to 5 per cent per project.

In terms of the Victorian value for money studies dealing with the impact of the GRP, DTF has relied on an externally developed model. DTF acknowledges that it did not assess the soundness of this model before relying on it as the basis for advice to government in early 2011 on the impact of the GRP.

The model DTF used to estimate benefits relies on two key assumptions, and cautions against citing the estimated benefits if these assumptions are not met. The first assumption is that the benefits identified under the model refer to ideal benefits generated if all Gateway review recommendations are adopted as intended. The second assumption is that Gateway review teams are able to correctly identify all problems. DTF did not outline these assumptions when citing the benefits derived from using this model in its advice to government in early 2011.

This audit found that these assumptions are not uniformly met in practice:

- Gateway reviews are short, sharp, peer-like reviews of projects at a point in time—they are not a detailed audit and should not be relied upon to identify all significant issues and risks in a project.

- There is clear evidence that not all agencies act on all Gateway recommendations.

DTF has not initiated any further work to estimate the impact of the GRP on project delivery performance.

Overall, DTF does not gather and use sufficient evidence to demonstrate that the objectives and benefits envisaged for the GRP are being realised. Specific shortcomings are detailed below.

3.4 Measuring the impact of Gateway reviews on individual projects

DTF does not systematically record and track the impact of the GRP on the performance of projects, despite this being foreshadowed as a means of periodically assessing the progress and impact of the GRP as early as 2004.

When the GRP was introduced it was intended that its impact on individual projects would be periodically measured. The Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) developed a detailed review tool in 2004 in consultation with DTF, departments and the Gateway Supervisory Committee. This was intended to be used over time to assess the impact of the GRP against the underlying objectives.

The review tool provided a sound basis for ongoing rigorous review of the impact of the Gateway Initiative. It comprised 30 indicators to be used in measuring progress and impact in relation to the Gateway Initiative strategy, process and outcomes. The government endorsed the review tool for use in August 2004.

One of the review tool indicators was ‘A greater proportion of government capital projects delivered on time, on budget, within scope’. This was to be measured by comparing the pre- and post- Gateway scenarios, as well as comparing the performance of projects that had undergone the GRP with the performance of projects that had not.

However, this analysis has only been performed once. In 2006 DPC reported to government on its analysis of project outcomes pre and post the introduction of the GRP. The average project delay had fallen since the introduction of the GRP but the net actual overspend across all projects had increased from 10 per cent to 13.2 per cent. DPC also reported that a comparison of asset performance on a year‑by-year basis, rather than on a pre- to post-GRP period basis, showed that there had been no obvious improvement from 1999 to 2006.