Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits

Overview

This report presents the results from the 2012–13 financial audit of the 11 portfolio departments and 197 associated entities which make up the core of the public sector, and are responsible for delivery of key public services and community support programs.

The financial reports prepared by the portfolio departments and associated entities were both timely and accurate, and can be relied on by Parliament and the public.

Of the 208 entities, 47 are self-funded as a majority of their revenue is generated from operations. Five self-funded entities were assessed as having a high financial sustainability risk in each of the past five years. They face financial challenges that, if not addressed, may reduce the service potential of their assets, and affect the services they offer to the community.

We reviewed the use of contract and temporary staff by portfolio departments. We were unable to analyse their spending on contract staff over time, due to a lack of data and inconsistencies in definitions used by the portfolio departments, and so were unable to determine if spending patterns had changed in response to the Sustainable Government Initiative to reduce Victorian Public Sector staff numbers. Our review of the data available showed some contract and temporary staff had been engaged for extended periods of time, some for more than 10 years.

A business continuity plan sets out how an entity will respond if its operations are interrupted by an event such as a natural disaster or equipment failure. While all portfolio departments had business continuity plans in place, seven had no overarching plan to prioritise, manage or co-ordinate their response and recovery in the event of more than one division being impacted by an event.

As part of the business continuity review we looked at disaster recovery planning by portfolio departments. While all had a disaster recovery plan, CenITex, the information technology shared service provider for 10 of the 11, does not. This means that the ability of the 10 portfolio departments to recover operations and provide essential public services is at risk. Such a risk should be unacceptable to Parliament and the public.

Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER November 2013

PP No 280, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits.

This report presents the outcomes and observations from the 2012–13 financial audit of the 11 portfolio departments and 197 associated entities. The report finds that financial reports were reliable and prepared in a timely manner.

However, our reviews of controls over contract and temporary staff, business continuity and disaster recovery have raised issues that warrant attention. In particular, the ability of portfolio departments to recover operations and provide essential public services in the event of a business disruption is at risk. Such a risk should be unacceptable to Parliament and the public.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

27 November 2013

Audit summary

This report presents the outcomes and observations from the financial audits of the 11 portfolio departments and 197 associated entities that are not reported in our other sector based reports.

These 208 entities make up the core of the public service and are responsible for delivering key public services and community support programs. It is important that they prepare high quality financial reports in a timely manner so that Parliament and the public can see the revenue, expenses, assets and liabilities required to provide public services and programs.

An effective internal control framework supports portfolio departments and associated entities to operate and report reliably and accurately, and in a timely way. There are many facets of an internal control framework and annually we select areas on which to focus and provide comment. In this report we make comment on the use of contract and temporary staff, and the business continuity and disaster recovery planning frameworks at the 11 portfolio departments and the shared service providers upon which they rely.

Conclusion

Financial reports prepared by portfolio departments and their associated entities are both timely and accurate, and their contents can be relied on by Parliament and the public.

Five of the six self-funded agencies that have been rated as having a high risk to their financial sustainability in each of the past five years have financial challenges that, if not addressed, may reduce the service potential of their assets, and affect the services they offer to the community.

There are weaknesses in the engagement and management of contract and temporary staff, and business continuity and disaster recovery planning by portfolio departments that need to be addressed in order to mitigate the risk of not achieving value-for-money outcomes and continuity of service delivery to the community.

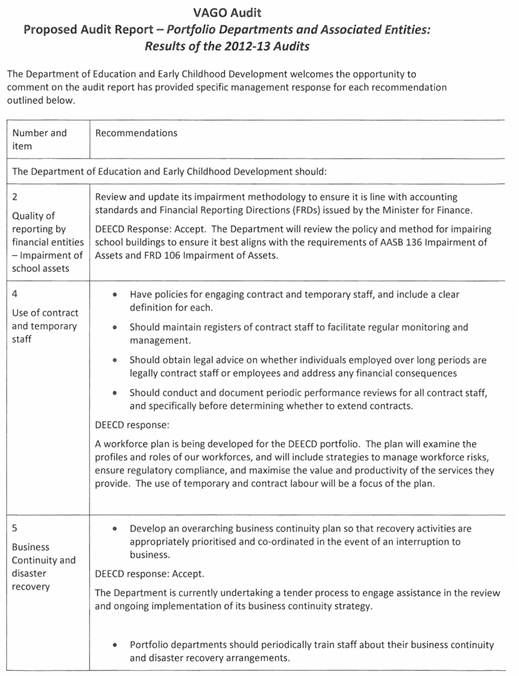

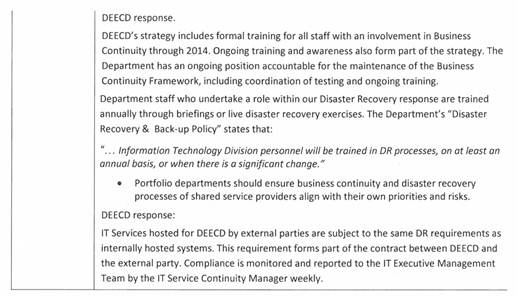

Quality of reporting by financial entities

A clear audit opinion confirms that an entity's financial report has been prepared according to the requirements of relevant accounting standards and legislation and presents the financial results of the entity's operations and its assets and liabilities fairly in all material respects. Clear opinions were issued for each of the 203 entities audited at the time of preparing this report. Five audit opinions are still to be issued at the date of reporting.

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) reported school buildings in its balance sheet at 30 June 2013 with a value of $6 630 million. DEECD has a policy whereby school assets are impaired annually if the size of a school's buildings exceeds the school's 'entitlement' by more than 10 per cent.

During the period 2007–08 to 2012–13, $4 400 million was invested in school buildings by the Commonwealth and state governments for new facilities and refurbishments including the Building the Education Revolution program. Over the same period, school enrolments did not increased at the same rate as the spending. As a consequence of the impairment policy, school buildings were assessed as impaired and $1 274 million was written off.

We have requested DEECD to review its impairment policy because we consider that the school buildings that may be in excess of need are still capable and available for providing educational outcomes and for community use. DEECD has formed a working group and we expect DEECD to resolve this matter by the end of 2013.

Financial sustainability of self-funded public sector entities

Of the 208 entities audited, 47 are classified as self-funded, because the majority of their revenue is generated from their operations. As a broad rule, self-funded entities should aim to generate sufficient revenue from operations to meet their financial obligations, and to fund asset replacement and new asset acquisitions, if they are to be financially sustainable over the long term.

Thirty of the 47 self-funded entities have been subject to our financial sustainability analysis in each of the past five years. This year we analysed the five year trend for each of the 30 and noted no change in their sustainability ratings over that period. It is concerning that six of the 30 have been assessed as having a high sustainability risk in each of the five years. The six entities are:

- Docklands Studio Melbourne Pty Ltd

- Federation Square Pty Ltd

- Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Centre Trust

- Port of Melbourne Corporation

- State Sports Centre Trust

- Victorian Arts Centre Trust.

Our further analysis identified that for all of these entities, with the exception of the Port of Melbourne Corporation, there are financial challenges that, if not addressed, may lead to a reduction in the service potential of their assets and consequentially reduce the services they are able to offer to the community.

Under the current funding model, self-funded entities have a limited ability to improve their financial sustainability.

Over the past five years, we have recommended that the Department of Treasury and Finance resolve the conflict between the funding model and accountabilities for self‑funded entities. At the date of publishing this report, no changes had been made.

Use of contract and temporary staff

Contract and temporary staff may be used by portfolio departments to procure specialist skills not available within the department or the Victorian public service, or to fill temporary vacancies or short-term roles.

Portfolio departments should have controls to effectively manage and oversee contract and temporary staff so that value-for-money outcomes are achieved.

We set out to analyse portfolio departments' spending patterns on contract or temporary staff over time, but we were unable to do so due to the lack of data or central records, and inconsistencies in the data due to differing definitions used by portfolio departments.

The ability of individual portfolio departments to monitor the numbers of, and spending on, contract staff is limited. In particular, three portfolio departments were unable to determine the number and cost of contact staff engaged in 2012–13.

Despite the lack of centralised data, our assessment of the data that could be provided showed instances where contract and temporary staff had been engaged for extended periods of time. Contract staff were also often re-engaged once their contracts had finished, with some being employed for more than 10 years in the same portfolio department. Temporary staff were also employed for extended periods and not always on a short-term basis. For example, 69 individual temporary staff had been engaged by portfolio departments for more than three years.

Extensions of contract and temporary staff engagements occurred in all portfolio departments. Documented performance reviews were available for only 14 per cent of contract and temporary staff engagements audited. It was unclear if performance assessments were routinely conducted when extending or renewing contract and temporary engagements.

The engagement of temporary staff on short-term contracts can justify the premium paid to labour hire firms, when judged against the alternative, that is, the cost of employee benefits payable to ongoing staff. However, where temporary staff have been engaged for long periods, an assessment of the situation should be conducted to determine whether value for money is being achieved compared with the cost of engaging ongoing staff.

Our analysis suggests that contract and temporary staff are being used by portfolio departments to replace employees rather than to fill short-term vacancies. Engaging contract and temporary staff in the manner demonstrated by our analysis increases the risk that the individuals involved become legally akin to employees, and attract the same employment benefits afforded to ongoing staff.

In times of fiscal restraint, there is a risk that contract and temporary staff may be used to create a perception of compliance with the requirement to downsize the public service. Due to the lack of contract staff data that could be provided by the portfolio departments, we were unable to determine if spending patterns on contract staff changed in response to the Sustainable Government Initiative staff reduction targets.

Management responsibilities taken up by contract staff

Portfolio departments are required to disclose all members of staff with significant management responsibilities, in their financial statements annually, in accordance with Financial Reporting Direction 21B Disclosures of Responsible Persons. At 30 June 2013 there were 21 instances where contract staff were disclosed as having significant management responsibilities. These staff were engaged across five portfolio departments.

Of the 21 staff, two had been delegated financial responsibilities within one portfolio department. In neither case had the appropriate authorisation from the Minister for Finance to receive such delegation been obtained, in breach of the Financial Management Act 1994. Corrective action is now being undertaken by the portfolio department concerned.

Business continuity and disaster recovery

Business continuity plans (BCP) set out how a portfolio department will respond in the event of an interruption to its operations from events such as natural disasters, equipment failures or other causes. A BCP should outline how a portfolio department will restore its systems, processes and services in an efficient manner in order to resume operations. This is particularly important in the public sector, where the disruption of services, such as support payments or provision of water to households, can have a detrimental impact on the community.

While all portfolio departments had BCPs in place for specific business units, seven had no overarching BCP to prioritise, manage or coordinate response and recovery in the event of more than one division being impacted by an event. This could significantly affect their orderly and timely recovery.

Most portfolio departments rely on shared service providers to provide essential services such as information technology systems and support, and payroll. The key providers of these services to portfolio departments are CenITex and Business Services Technology (BST). Both CenITex and BST have a BCP however, portfolio departments had not considered these plans, nor assessed any gaps or risks between the service providers' plans and their own.

In the event of a disruption to services, it is unclear what the priorities of CenITex and portfolio departments would be for recovering services or whether the priorities are complementary. There is a risk that there will be unnecessary delays in the restoration of the public services most important to the community, should a disruption occur.

Information technology disaster recovery

A BCP should include a disaster recovery plan (DRP) that deals with the restoration of critical business information systems after a disruption. While most portfolio departments have a DRP, the effectiveness of these plans is uncertain as CenITex does not have sufficient disaster recovery capability to respond to a significant event. This means that for the 10 portfolio departments whose information systems are supported by CenITex, the ability to recover operations and provide essential public services is at risk. Unassessed and unmanaged, this risk should be unacceptable to Parliament and the public.

It is a further concern that portfolio departments are not informing themselves adequately as to the disaster recovery capabilities of CenITex. While CenITex has been advising portfolio departments that it does not have a disaster recovery plan in annual attestations, there has been no action by portfolio departments or CenITex to address the risks that arise.

CenITex and portfolio departments must work together to assess, manage and mitigate disaster recovery risks. In not doing so they are failing in their roles by exposing the public to an unacceptable risk of being unable to recover after a significant event. As the role of CenITex changes in the future to brokering and managing services, portfolio departments will be further removed from the service delivery provider which may increase this disaster recovery risk further.

Recommendations

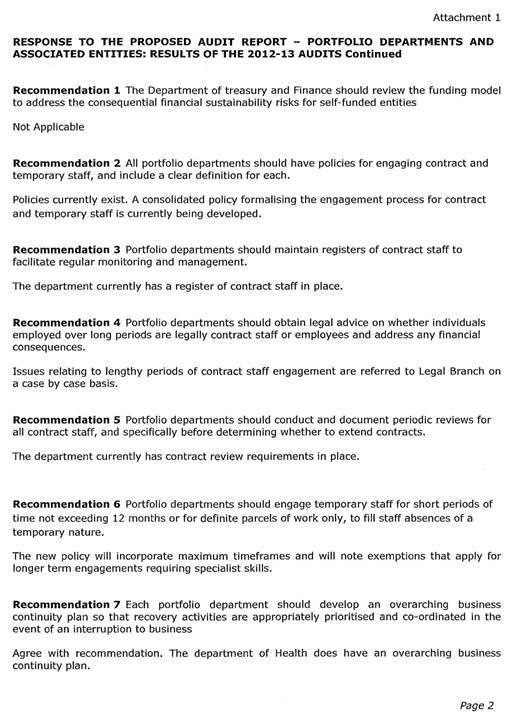

- The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the funding model to address the consequential financial sustainability risks for self-funded entities.

- All portfolio departments should have policies for engaging contract and temporary staff, and include a clear definition for each.

- Portfolio departments should maintain registers of contract staff to facilitate regular monitoring and management.

- Portfolio departments should obtain legal advice on whether individuals employed over long periods are legally contract staff or employees and address any financial consequences.

- Portfolio departments should conduct and document periodic performance reviews for all contract staff, and specifically before determining whether to extend contracts.

- Portfolio departments should engage temporary staff for short periods of time not exceeding 12 months or for defined parcels of work only, to fill staff absences of a temporary nature.

- Each portfolio department should develop an overarching business continuity plan so that recovery activities are appropriately prioritised and coordinated in the event of an interruption to business.

- CenITex should lead the development and regular testing of a disaster recovery plan.

- Portfolio departments should periodically train staff about their business continuity and disaster recovery arrangements.

- Portfolio departments should ensure business continuity and disaster recovery processes of shared service providers align with their own priorities and risks.

- CenITex and portfolio departments should clarify and agree their respective responsibilities for disaster recovery management.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to all portfolio departments and named agencies with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix F.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

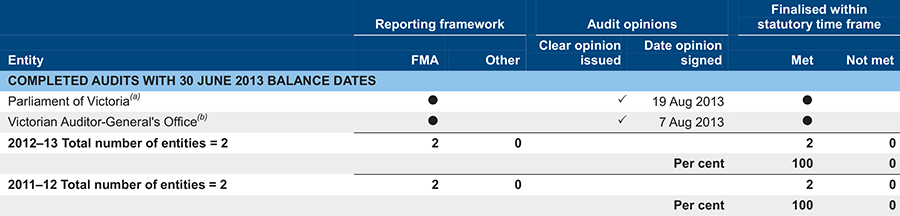

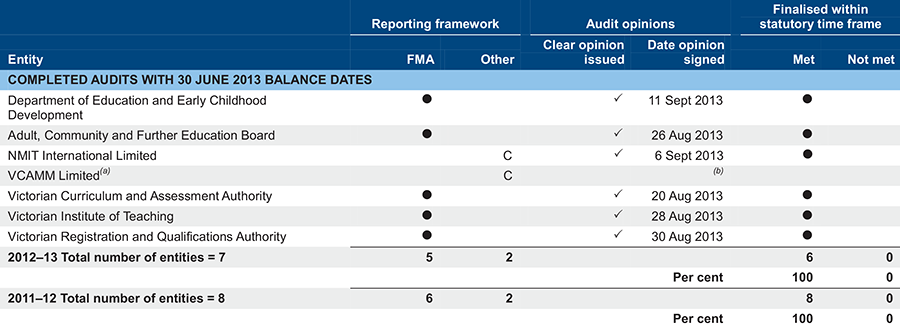

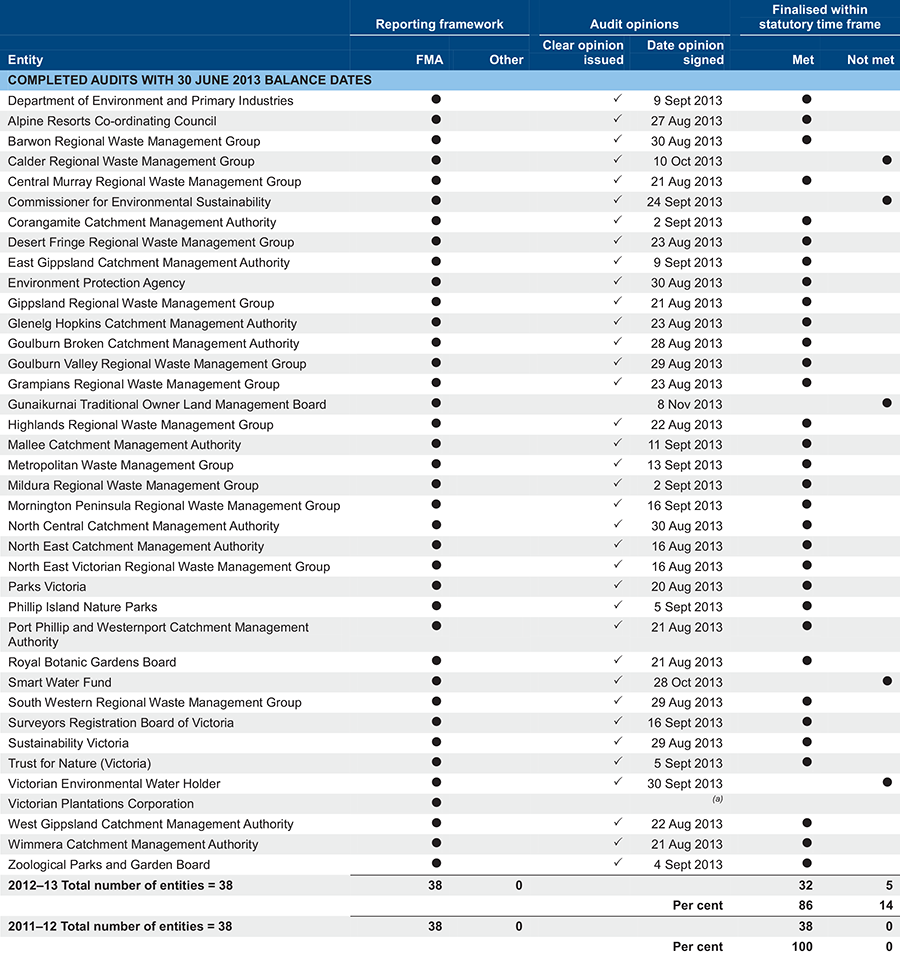

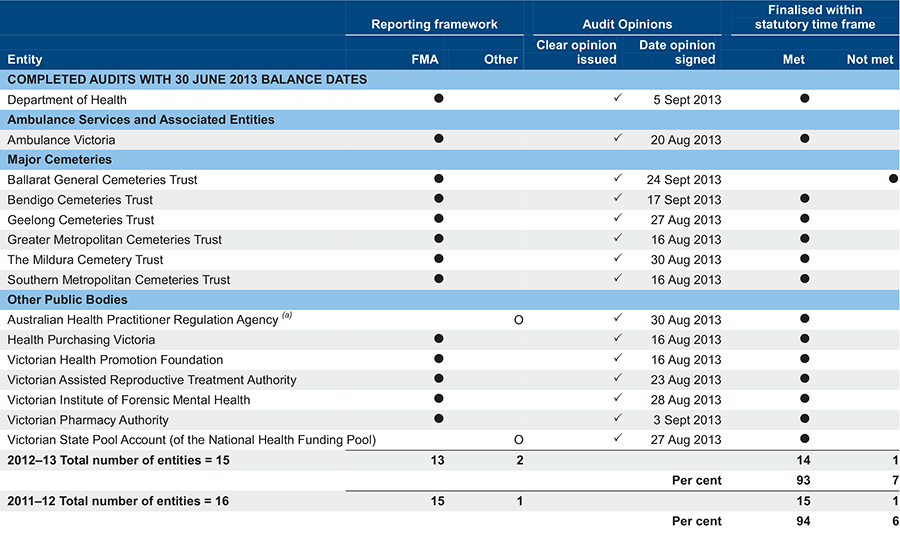

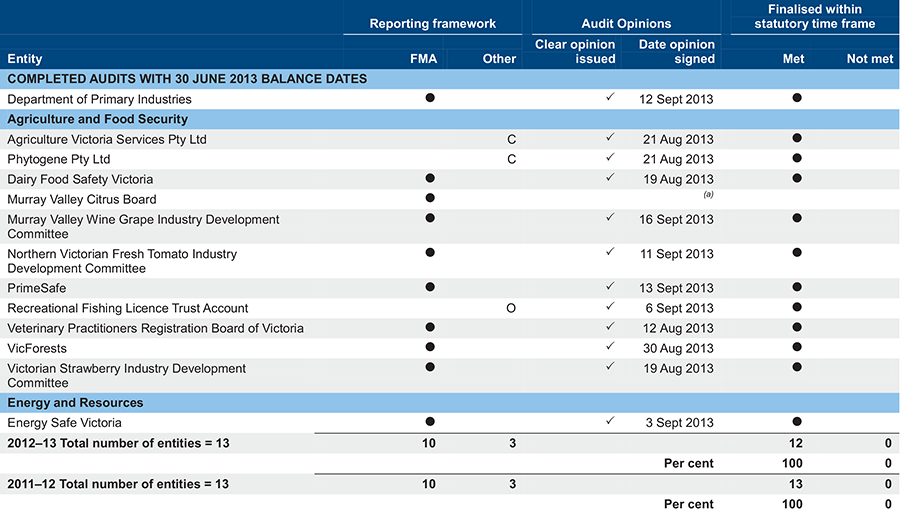

This report covers the 11 portfolio departments and 197 associated entities with 30 June 2013 balance dates. The most common reporting frameworks for these entities are the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) and the Corporations Act 2001. Figure 1A shows the number of entities per portfolio and legislative reporting framework.

Figure 1A

Entities by portfolio and legislative reporting framework

Financial Management Act |

Corporations Act |

Other |

Total |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portfolio |

2012–13 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

2011–12 |

| Parliament | 2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

2 |

| Education and Early Childhood Development | 5 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

8 |

| Environment and Primary Industries | 38 |

38 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

38 |

38 |

| Health | 13 |

15 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

1 |

15 |

16 |

| Human Services | 3 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

| Justice | 27 |

26 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

31 |

30 |

| Planning and Community Development | 13 |

13 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

14 |

14 |

| Premier and Cabinet | 11 |

11 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

12 |

12 |

| Primary Industries | 10 |

10 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

13 |

13 |

| State Development, Business and Innovation | 7 |

7 |

4 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

11 |

12 |

Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure |

11 |

10 |

6 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

17 |

17 |

| Treasury and Finance | 15 |

15 |

7 |

7 |

23 |

18 |

45 |

40 |

| Total | 155 |

155 |

25 |

27 |

28 |

22 |

208 |

204 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The number of entities audited and covered in this report increased by four in 2012–13. A list of the changes is provided in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

Changes to audited entities in 2012–13

Merged with another entity |

|

|---|---|

Legal Services Board and the Legal Services Commission |

Composite report prepared showing the financial results and financial positions of the two entities as a single reporting entity. |

State Owned Enterprise for Irrigation Modernisation in Northern Victoria |

Merged into Goulburn Valley Rural Water Corporation from 1 July 2012 pursuant to State Owned Enterprises Act 1992. |

New audits |

|

Commission for Children and Young People |

Established on 1 March 2013 pursuant to the Commission for Children and Young People Act 2012. |

Gunaikurnai Traditional Owner Land Management Board |

Established in October 2010 pursuant to the Conservation,

Forests |

Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission |

Established on 1 July 2012 pursuant to the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011. |

Public Transport Development Authority |

Reported as a composite entity of Department of Transport at 30 June 2012. Reported as a separate entity at 30 June 2013. |

Resident's Trust Fund |

2012–13 was the first year VAGO provided an opinion on this audit. Opinion previously issued by an alternative auditor. |

State Trustees Australia Foundation |

2012–13 was the first year VAGO provided an opinion on this audit. Opinion previously issued by an alternative auditor. |

State Trustees Australia Foundation Open Fund |

2012–13 was the first year VAGO provided an opinion on this audit. Opinion previously issued by an alternative auditor. |

VFMC Enhanced Cash Trust |

Established 27 July 2012.. |

VFMC Fixed Income Trust |

Established 26 November 2012. |

VFMC Opportunistic Strategies Trust |

Established 20 September 2012. |

Victorian Inspectorate |

Established 1 July 2012 under Part 8 of the Victorian Inspectorate Act 2011. |

Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation |

Established 1 July 2012 as a body corporate under the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation Act 2011. |

Victorian State Pool Account (of the National Health Funding Pool) |

Established on 28 September 2012 pursuant to the Victorian Health (Commonwealth State Funding Arrangements) Act 2012. |

Wound up |

|

Australian Synchrotron Company Ltd |

Ceased on 19 June 2013. Deregistered due to its function being transferred to the Synchrotron Light Source Australia Pty Ltd (a Commonwealth entity). |

Chinese Medicine Registration Board of Victoria |

Ceased on 30 June 2012 pursuant to the Statute Law Amendment (National Health Practitioner Regulation) Act 2010. Operations passed on to the National Board under the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. |

Medical Radiation Practitioners Board of Victoria |

Ceased on 30 June 2012 pursuant to the Statute Law Amendment (National Health Practitioner Regulation) Act 2010. Operations passed on to the National Board under the Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency. |

Metlink Victoria Pty Ltd |

Ceased on 21 June 2012. Responsibility passed to Public Transport Victoria. |

VicFleet Pty Ltd |

Deregistered as a company on 13 October 2012. Responsibility passed to DTF. |

Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation |

Wound up 5 Feb 2012. Responsibility passed to Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation pursuant to the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation Act 2011. |

Victorian Skills Commission |

Ceased on 31 December 2012 pursuant to the Education Legislation Amendment (Governance) Act 2012. Operations passed to the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.2 Machinery-of-Government changes

Machinery-of-Government (MoG) changes amend the administrative structure of government agencies. These can be small, such as the transfer of a function from one portfolio department to another, or significant, for example the merging of portfolio departments.

On 9 April 2013, the Premier announced MoG changes that affected some of the 11 portfolio departments and included:

- changes to structure

- new Departmental Secretaries

- changes to ministerial allocations.

On 12 April 2013, an Order in Council was issued under the Public Administration Act 2004. It renamed three existing departments with immediate effect:

- the Department of Transport was changed to the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure

- the Department of Sustainability and Environment was changed to the Department of Environment and Primary Industries

- the Department of Business and Innovation was changed to the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation.

The Department of Planning and Community Development and the Department of Primary Industries, ceased to exist effective from 1 July 2013.

On 3 June 2013, the Premier made a declaration under section 30 of the Public Administration Act 2004that transferred staff and functions between portfolio departments on that day, to effect the MoG changes.

For 30 June 2013 financial reporting, no transfer of assets, liabilities, revenues or expenditures was made. A disclosure was included in the notes of each effected portfolio departments' financial report that identified the changes and the potential impact. The financial impacts of the MoG changes will be recognised in the 2013–14 financial statements for portfolio departments.

1.3 Reporting framework

Financial statements are required to be prepared in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards, Interpretations and legislated reporting frameworks. Under the FMA, the Minister for Finance has the authority to issue directions in relation to finance administration and reporting issues.

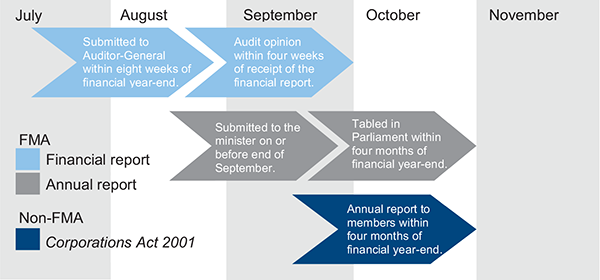

The FMA requires annual reports to be submitted to the relevant minister and tabled in Parliament within four months of the end of the financial year. These reports should include financial reports for the entity and any controlled entities, and are required to be prepared and audited within 12 weeks of the financial year end.

Entities reporting under the Corporations Act 2001 are required to report to their members within four months of the end of the financial year. A summary of the FMA and Corporations Act 2001 reporting time frames is provided in Figure 1C.

Figure 1C

Legislated financial reporting time frames

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.4 Internal controls

Internal controls are systems, policies and procedures that help an entity to reliably and cost-effectively meet its objectives. Sound internal controls enable the delivery of reliable, accurate and timely external and internal reports. An entity's governing body is responsible for developing and maintaining its internal control framework.

In addition to reviewing general internal controls, a cyclical approach to reviewing internal controls relating to significant annual financial report balances and disclosures is adopted at portfolio departments, consistent with Australian Auditing Standards.

The annual financial audit enables the Auditor-General to form an opinion on an entity's financial report. In our annual financial audits, we focus on the internal controls relating to the preparation of the financial report and assess whether entities have managed the risk that their financial statements will not be complete and accurate. Poor controls diminish management's ability to achieve strategic objectives and to comply with relevant legislation. They also increase the risk of fraud, misstatements, omissions and errors.

Internal control weaknesses we identify during an audit do not usually result in a 'qualified' audit opinion because often an entity will have compensating controls that mitigate the risk of a material error in the financial report. A qualification is warranted only if weaknesses cause significant uncertainty about the accuracy, completeness and reliability of the financial information being reported.

Weaknesses in internal control found during the audits of an individual entity are reported to its Secretary, board or chief executive officer and audit committee in a management letter.

Our reports to Parliament raise systemic or common weaknesses identified during our assessments of internal controls over financial reporting and selected focus areas, across a sector. This report includes the results of our cyclical reviews of the management framework for contractors and temporary staff, and the framework for business continuity and disaster recovery planning.

1.5 Audit conduct

The audits were undertaken in accordance with Australian Auditing Standards.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of preparing and printing this report was $225 000.

1.6 Structure of this report

The structure of this report is set out in Figure 1D.

Figure 1D

Report structure

Parts |

Description |

|---|---|

Part 2: Quality of reporting by financial entities |

Comments on the quality of financial reports prepared by portfolio departments and associated entities. |

Part 3: Financial sustainability of self-funded public sector entities |

Provides insight into the financial sustainability on self‑funded state entities based on an assessment of four indicators that consider both short- and long-term sustainability. |

Part 4: Use of contract and temporary staff |

Comments on the policies, management practices and governance and oversight regarding the use of contractors and temporary staff across the portfolio departments. |

Part 5: Business continuity and disaster recovery |

Comments on the policies, management practices and governance and oversight relating to business continuity planning and information systems disaster recovery across the portfolio departments. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2 Quality of reporting by financial entities

At a glance

Background

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing assurance that the information reported is reliable. This Part covers the results of the 2012–13 audits of 11 portfolio departments and 197 associated entities, and our observations regarding the quality of agency financial reporting.

Conclusion

Clear audit opinions were issued for each of the 203 audits completed, meaning that the 2012–13 financial reports of the audited entities were reliable and fairly presented the results of the entities' operations for the year, and their assets and liabilities as at 30 June 2013.Findings

- Two entities received emphasis of matter paragraphs in their audit opinions, drawing attention to particular circumstances about the basis on which the financial statements were prepared.

- The audit opinions for nine entities were not issued within the applicable reporting time lines.

- Five audit opinions were still to be issued at 20 November 2013.

- As a result of the current impairment methodology applied by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), about a third of the $4 400 million invested in school buildings over the past six financial years has been written off as an impairment adjustment. We have asked DEECD to review their impairment methodology.

- The Auditor-General undertook four financial audits by invitation in 2012–13. Spending of public funds by these agencies should be required to be subjected to audit scrutiny. In this respect, the Audit Act 1994 needs amending so that audit scrutiny is mandated.

2.1 Introduction

This Part covers the results of the 2012–13 audits of 11 portfolio departments and 197 associated entities, and our observations regarding the quality of agency reporting.

2.2 Conclusion

Financial reports prepared for portfolio departments and their associated entities for 2012–13 were of a high standard. At the date of preparing this report, 203 clear audit opinions had been issued, however, nine of the opinions were issued after the statutory reporting time frames.

2.3 Reliability

2.3.1 Audit opinions

Independent audit opinions add credibility to financial reports by providing assurance that the information in the reports is reliable and presents the entities' results fairly. A clear audit opinion confirms that the financial report has been prepared according to accounting standards and legislation and that the report presents fairly, in all material respects, the financial position of the entity.

At the date of preparing this report, 203 clear audit opinions on financial reports had been issued.

Emphasis of matter

An auditor can draw a reader's attention to a matter or disclosure in the financial report to provide important context. Financial reports that include an 'emphasis of matter' paragraph in the audit opinion still present the entity's financial information fairly and can be relied upon by users.

In 2012–13 two entities received an audit opinion containing an emphasis of matter. Figure 2A lists the entities and the reason for adding an emphasis of matter paragraph in the audit opinion.

Figure 2A

Opinions with emphasis of matter paragraphs, 2012–13

Entity |

Reason |

|---|---|

Legal Services Board and the Legal Services Commissioner |

The financial report was prepared to present the composite financial result and financial position of the two entities as a single reporting entity. The auditing standards require an emphasis of matter in such circumstances. |

VFMC Ontario |

Management determined that the going concern basis was inappropriate for the preparation of the financial statements for the period ending 30 June 2013, due to the intended wind up of the company. The financial report was prepared on a basis to reflect the orderly winding up of the company. The auditing standards require an emphasis of matter in such circumstances. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4 Quality of reporting

The quality of an entity's financial reporting can be measured by the accuracy and timeliness of the preparation and finalisation of its financial report.

2.4.1 Accuracy

The frequency and value of errors in draft financial reports are direct measures of the quality of the reports submitted for audit. Ideally, there should be no errors or adjustments required as a result of an audit. When errors are detected in draft financial statements, we raise them with management.

Material errors identified during the financial report preparation and audit need to be corrected before a clear audit opinion can be issued. Other errors should also be corrected. While some errors may appear immaterial in isolation, in aggregate, a series of small errors may have a significant impact on the financial statements or an entity's operating result.

Our expectation is that all entities will adjust errors identified during an audit, other than those errors that are clearly trivial as defined under the auditing guidelines. This expectation is consistent with our principle that the public is entitled to expect that financial statements that bear the Auditor‑General's opinion are accurate and of high quality.

Impairment of school assets

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) has a significant investment in school buildings with the value carried in its balance sheet at 30 June 2013 being $6 630 million.

Australian Accounting Standards require entities to consider annually whether there is an indication that their assets may be impaired. An asset is impaired if the value of the assets in an entity's financial records is greater than the economic benefit that can be generated from those assets. In the case of not-for-profit entities, assets are held to provide an outcome or community benefit, not an economic benefit. In the case of DEECD's school buildings the core outcome is to provide education to Victoria's children.

In 2006, the implementation of the Australian International Financial Reporting Standards required the department to assess schools assets for impairment. DEECD adopted a policy whereby school assets are impaired annually if the size of a school's buildings exceeds the school's 'entitlement' by more than 10 per cent. The school's entitlement was calculated based on the number of school enrolments and an area entitlement for each student. If, for example, a school has 30 per cent floor space over and above its entitlement, the value of all that school's assets are impaired by 23 per cent.

In line with its impairment methodology, DEECD has impaired the value of its school buildings at each subsequent year end. Figure 2B shows the value of school buildings impaired by DEECD since 2006. The cumulative impairment charge against school buildings was $1 336 million, or 20 per cent of the building balance at 30 June 2013.

Figure 2B

Impairment adjustments 2005–06 to 2012–13

Portfolio |

2005–06 ($mil) |

2006–07 ($mil) |

2007–08 ($mil) |

2008–09 ($mil) |

2009–10 ($mil) |

2010–11 ($mil) |

2011–12 ($mil) |

2012–13 ($mil) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buildings balance at 1 July | 3 627 |

4 051 |

4 014 |

4 271 |

4 244 |

4 538 |

5 440 |

6 383 |

| New building assets | 127 |

132 |

214 |

383 |

634 |

1 430 |

1 857 |

587 |

| Impairment adjustment | (29) |

(33) |

(82) |

(39) |

(116) |

(315) |

(615) |

(107) |

| Other items(a) | 326 |

(136) |

125 |

(372) |

(224) |

(213) |

(299) |

(233) |

Buildings balance at 30 June |

4 051 |

4 014 |

4 271 |

4 243 |

4 538 |

5 440 |

6 383 |

6 630 |

| Impairment adjustment as a percentage of balance at 30 June | 0.72% |

0.82% |

1.92% |

0.92% |

2.56% |

5.79% |

9.63% |

1.61% |

(a) 'Other

items' includes building disposals, building depreciation, building

revaluations and buildings transferred to held for sale.

Source: Victorian

Auditor-General's Office.

During the period from 2008–09 to 2011–12 the Commonwealth Government provided more than $2 500 million for new facilities and refurbishments in Victorian Government Schools, under the Building the Education Revolution program (BER). The BER was part of the Commonwealth's stimulus package aimed at protecting the Australian economy from the effects of the Global Financial Crisis. BER funding was allocated to most schools and was not tied to a demonstrated need for capital investment. A key condition of BER funding was that the built assets were to be available for community use.

During the period 2007–08 to 2012–13 the state government also invested around $1 900 billion in Victorian school buildings through the Victorian Schools Plan program.

The two programs significantly increased the size and capacity of school buildings. However, school enrolments have not increased at the same rate over the period. As a result, under DEECD's methodology, about a third of the amount invested over the past six financial years has been written off as an impairment adjustment. There were particularly large write-offs in 2010–11 to 2011–12 at the height of the BER.

Application of the impairment methodology means that assets that are still capable and available for providing educational outcomes and for community use are not currently recognised in the state's financial statements. Further, by reducing the asset base of the state, there is a risk that funding for maintaining 'as new' assets may not be provided leading to their physical deterioration, and an increased health and safety risk to children, school staff and community members.

Given this situation, VAGO has recommended that DEECD review and update its impairment methodology to ensure it is in line with accounting standards and Financial Reporting Directions issued by the Minister for Finance.

In response to our recommendation, DEECD has formed a working group including representatives from the Department of Treasury and Finance. We expect DEECD to have resolved this matter by the end of 2013.

2.4.2 Timeliness

Timely financial reporting is key to providing accountability to stakeholders and enabling them to make well‑timed and informed decisions. The later a financial report is produced and published after year end, the less useful it is.

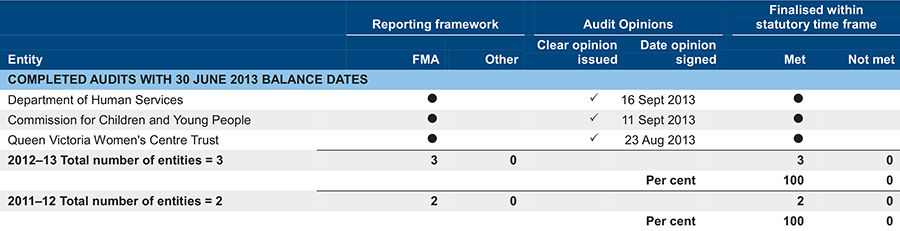

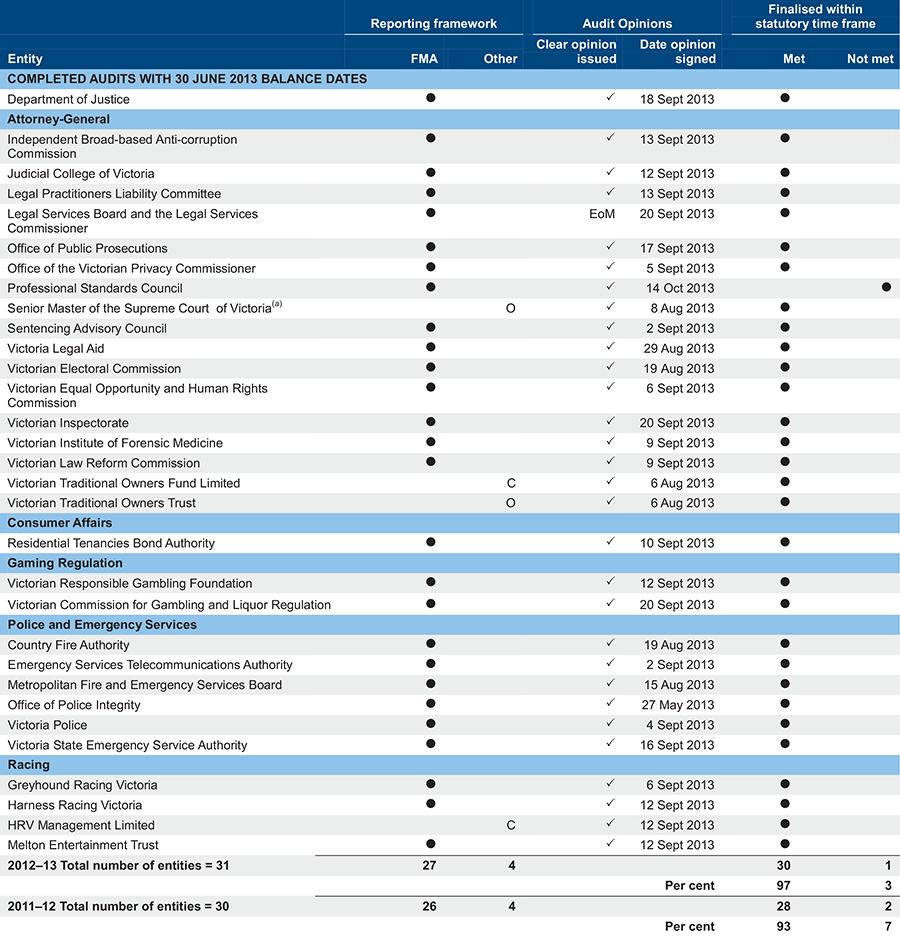

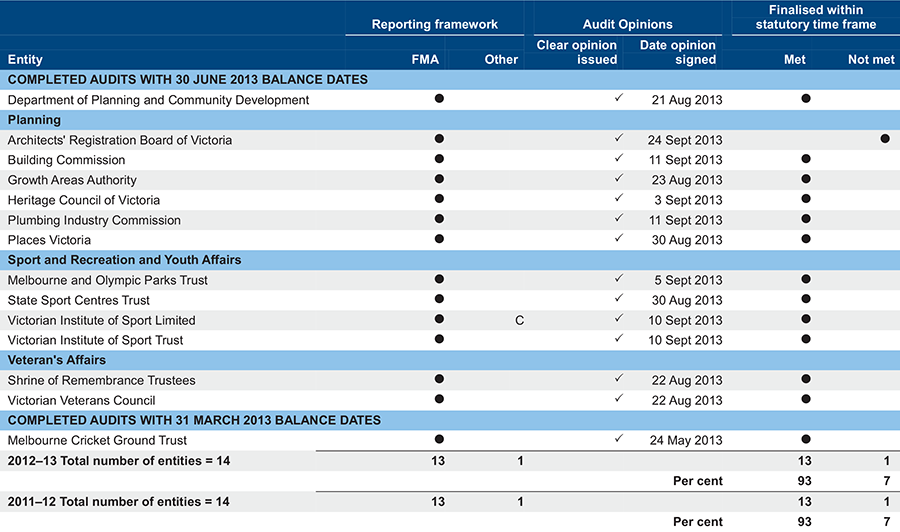

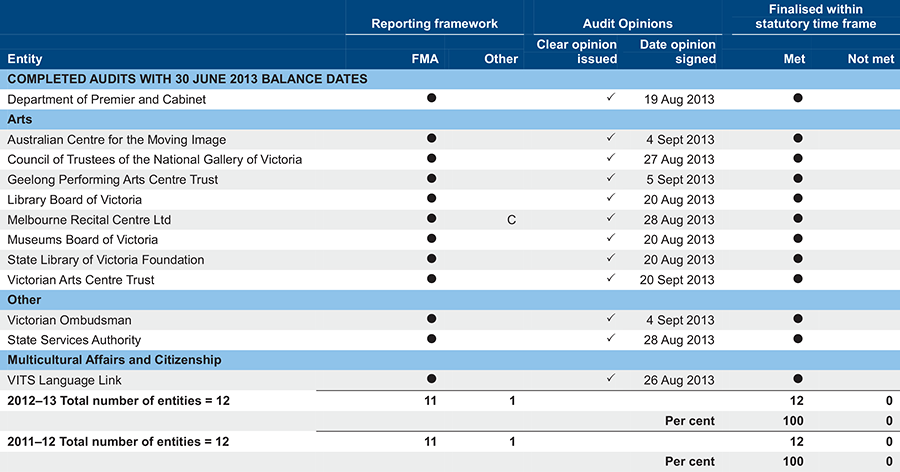

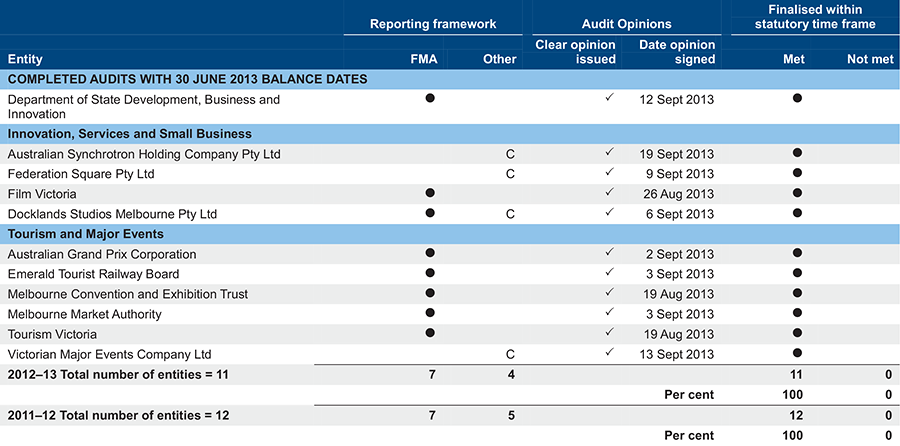

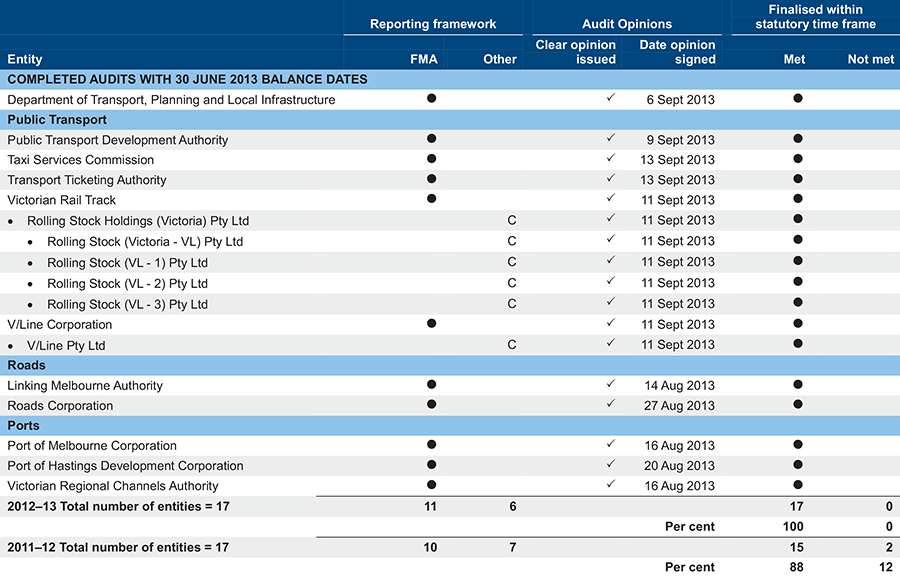

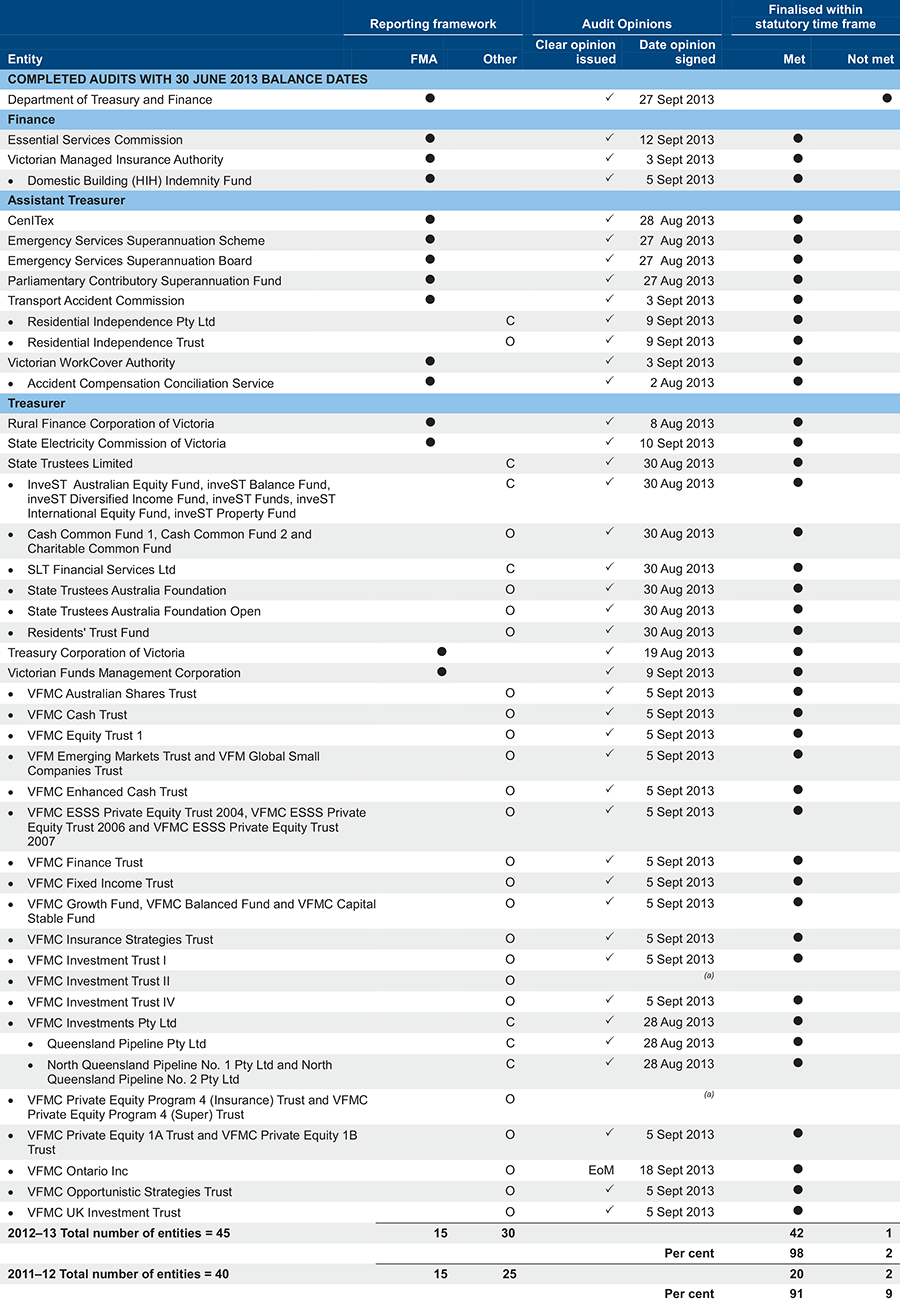

Appendix C details the dates audit opinions for the 11 portfolio departments and 197 associated entities were signed for 2012–13. Of the 208 entities listed, nine (4 per cent) did not receive an audit opinion within their statutory deadlines. Another five had not received an opinion at 20 November 2013.

While there are no immediate consequences for these entities in not reporting within the time frames, the delays means that their stakeholders were not provided with key information on the entities' performance within a reasonable period after year end.

2.5 Audits by invitation

An entity that does not meet the definition of an authority under the Audit Act 1994 (the Act) is not required to have the Auditor-General conduct its financial audit. However, under section 16G of the Act, the Auditor-General can accept an invitation to conduct the financial audit of an entity that is not an 'authority'.

Before accepting such an invitation, the Auditor-General must be satisfied that the person or body exists for a public purpose and that it is practicable, and in the public interest, for the Auditor-General to conduct the audit.

The Auditor-General conducted financial audits of four entities by invitation in 2012–13:

- Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency

- Parliament of Victoria

- Senior Master of the Supreme Court of Victoria

- VCAMM Limited.

When conducting financial audits under section 16G, the Auditor-General is precluded from considering issues of waste, probity and lack of financial prudence—considerations that are required for all other financial audits conducted by the Auditor‑General, and are generally expected aspects of public sector audits.

The spending of public funds should be required to be subjected to audit scrutiny, both for what is spent and the way it has been spent. The audits currently performed by invitation should be mandated, and in this respect the Act needs amending.

For 2012–13, the opinions issued for audits conducted under section 16G articulated that no consideration was given to matters relating to waste, probity or the lack of financial prudence.

3 Financial sustainability of self-funded public sector entities

At a glance

Background

In this Part we review the financial sustainability of 47 self-funded entities, that is, entities that generate the major part of their revenue from their operations, rather than depending upon government funding.

The self-funded entities should aim to generate sufficient revenue from operations to meet their financial obligations, and to fund asset replacement and asset acquisitions.

Conclusion

There has been little improvement in the financial sustainability ratios of the 30 self‑funded entities on which we have reported each year for the past five years. Over the long term, a lack of depreciation funding and insufficient revenue to be self‑sustaining may lead to the service potential of assets reducing and a consequential reduction in the services that can be provided to the community.Findings

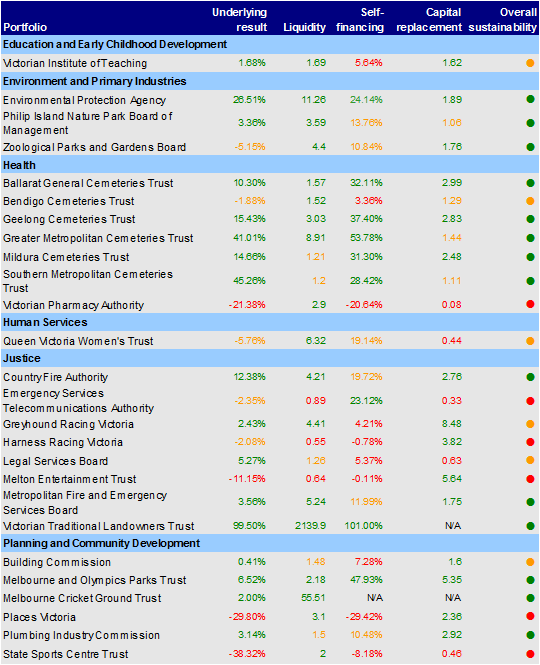

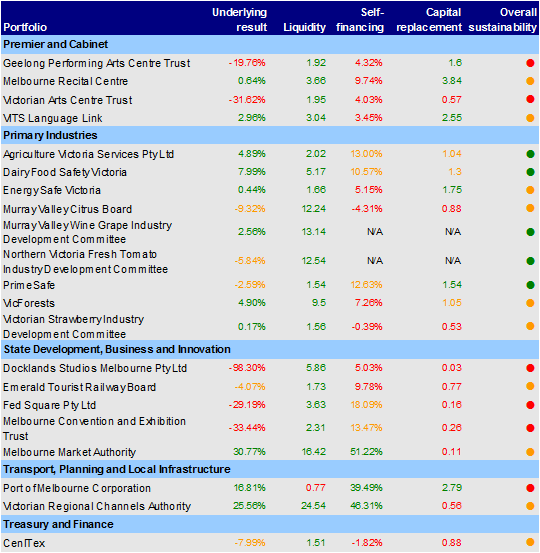

- Twelve of 47 entities received a high-risk rating for financial sustainability at 30 June 2013.

- Six of the 30 self-funded entities that have had their financial sustainability assessed in each of the past five years, have been assessed in the high-risk category in each of the five years. Five of the six have financial challenges that need to be addressed.

- Previous recommendations for the Department of Treasury and Finance to resolve the conflict between the funding model and accountabilities for self‑funded entities have not been addressed.

Recommendations

The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the funding model to address the consequential financial sustainability risks for self-funded entities.

3.1 Introduction

In this Part we review the financial sustainability of entities that primarily generate their own revenue from their operations, rather than depend upon government funding. In 2012–13, 47 entities have been identified as being self-funded.

The 11 portfolio departments and other entities predominantly funded through the state's budget have been excluded from the assessment. We have also excluded public hospitals, water and tertiary education entities from the assessment as their sustainability is assessed and reported to Parliament in our sector-specific reports, the details of which can be found in Appendix A.

Self-funded entities should aim to generate sufficient revenue from their operations to meet their financial obligations, and to fund asset replacement and asset acquisitions. Their ability to do this depends largely on their expenditure and revenue management practices, which are reflected in the composition and rate of change of their operating revenue and expenses.

3.2 Conclusion

There has been little improvement in the financial sustainability ratios of the 30 self‑funded entities on which we have reported each year for the past five years. State agencies do not receive funding for depreciation and are, in some cases, not generating sufficient revenue on their own to meet obligations, fund new assets and renew existing assets. Over the long term, such financial challenges may lead to the service potential of assets reducing and a consequential reduction in the services that can be provided to the community.

3.3 Financial sustainability

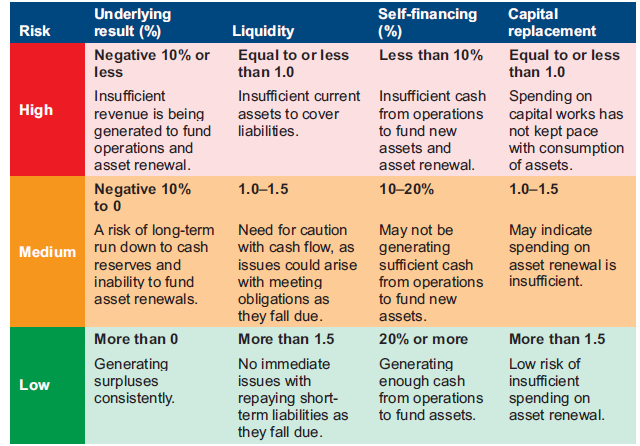

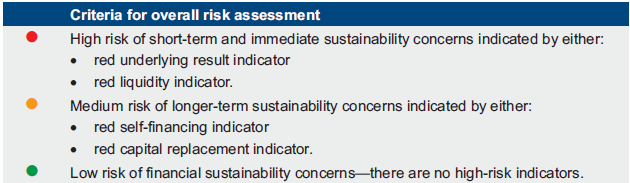

We analysed the financial trends and patterns of the self-funded entities by examining four core indicators over a five-year period. The indicators used were the underlying result, liquidity, self-financing and capital replacement, as they reflect an entity's funding and expenditure policies, and indicate whether the policies are sustainable.

Financial sustainability should be viewed from both the short- and long-term perspective. The short-term indicators, in this case, the underlying result and liquidity indicators, measure an entity's ability to maintain a positive operating cash flow and adequate cash holdings, and to generate an operating surplus over time. The long‑term indicators, that is, the self-financing and capital replacement indicators, signify whether adequate funding is available and being spent on asset renewal to maintain the quality of service delivery, and to help meet community expectations and the demand for services.

Appendix B describes the sustainability indicators, risk assessment criteria and the benchmarks we use in this report. Figure B4 in Appendix B provides the results of our analysis for each of the 47 self‑funded entities as at 30 June 2013.

3.4 Financial sustainability 2008–09 to 2012–13

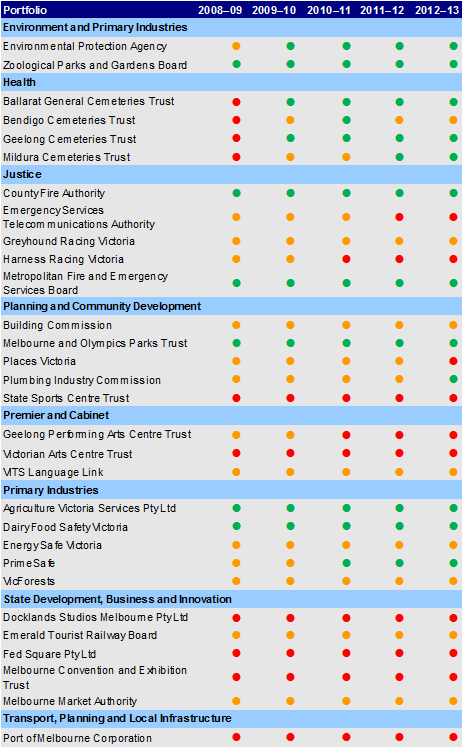

We have published a financial sustainability analysis for self-funded entities annually since 2008–09 in our Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of Audits reports.

Figure 3A provides a summary of the results for the 30 self-funded entities for which financial sustainability was assessed in each of the five years since 2008–09. Entities assessed in only some of the five years have been excluded from the data.

The data shows that there has been no improvement in the financial sustainability of the 30 self-funded entities across the five years, with 10 being rated as high risk in 2012–13, as was the case in 2008–09.

The detailed results by entity are provided in Appendix B, Figure B5.

Figure 3A

Financial sustainability risk assessment summary of results

for self-funded entities, 2008–09

to 2012–13

| Risk rating | 2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2012–13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 10 |

6 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

| Medium | 14 |

15 |

11 |

10 |

8 |

| Low | 6 |

9 |

11 |

11 |

12 |

| Total | 30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

30 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The lack of improvement is partly due to the funding model which does not give entities control over depreciation equivalent funding. As a result, the entities' governing boards and trusts have limited ability to improve their financial sustainability.

We have previously reported on this conflict between the funding model and accountabilities of self-funded entities and recommended that the Department of Treasury and Finance work to address it. At the date of publishing this report no changes to the model or accountability arrangements had been made. This means that the underlying issues impacting self-funded entities' financial sustainability are not being addressed.

3.5 High-risk entities

The following six entities have been rated as having

a high financial sustainability risk in each of the five years since

2008–09:

- Docklands Studios Melbourne Pty Ltd

- Federation Square Pty Ltd

- Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Trust

- Port of Melbourne Corporation

- State Sports Centre Trust

- Victorian Arts Centre Trust.

Excluding the Port of Melbourne Corporation, all high-risk entities fail to generate enough revenue to cover their depreciation costs, which means that insufficient funds are available for asset maintenance and renewal. This factor has the potential to impact on their financial sustainability over the long term and to decrease their ability to provide services.

A more detailed analysis of each of these entities' financial sustainability issues is provided below.

3.5.1 Docklands Studios Melbourne Pty Ltd and Federation Square Pty Ltd

Both Docklands Studios Melbourne Pty Ltd (Docklands Studios) and Federation Square Pty Ltd have been rated as a high financial sustainability risk for the past five years due to unfavourable underlying results and capital replacement ratios.

Both entities reported deficits at 30 June 2013, driven by depreciation costs. Federation Square Pty Ltd reported a deficit of $6.8 million, which included a depreciation expense of $11.5 million. Docklands Studios reported a deficit of $1.5 million, including $2 million in depreciation expenses.

Insufficient revenue to undertake asset maintenance and renewal may lead to long‑term challenges for Federation Square Pty Ltd and Docklands Studios to continue operating and to provide services at the current level.

3.5.2 Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Trust

The Melbourne Convention Centre opened in 2009 and is a public private partnership (PPP). The private sector has designed, constructed and financed the centre, and will maintain it for 25 years, after which the asset will return to the state. The Melbourne Convention and Exhibition Trust (MCET) is responsible for operating the centre, along with the Melbourne Exhibition Centre.

Since 2009, MCET has continued to have a high financial sustainability risk rating, due to unfavourable underlying result and capital replacement ratios. MCET reported a deficit of $28.7 million for the year ended 30 June 2013, which included depreciation expense of $27.0 million and interest expense of $16.8 million.

In the Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2010–11, we reported that MCET was required to meet half the cost of the PPP by repaying a $227.7 million loan to the Department of State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI). The loan is to be repaid over the 25-year period of the PPP. As at the 30 June 2013, MCET has repaid $17.4 million to DSDBI.

While noting that MCET generated $11.1 million in cash flows from operating activities for the year ended 30 June 2013, the requirement to service this loan is an additional financial challenge for MCET, as they need to both repay the loan and invest in asset renewal from cash flow surpluses.

3.5.3 Port of Melbourne Corporation

The Port of Melbourne Corporation (PoMC) achieved a high financial sustainability risk rating for each of the past five years due to its unfavourable liquidity ratio.

At 30 June 2013, PoMC held current assets of $72.6 million and current liabilities of $122.3 million. This suggests that the entity could potentially not meet its obligations as they fall due. The current liabilities include a provision of $18.5 million relating to the Port of Melbourne defined benefits superannuation fund.

Unlike other entities, which have longer-term financial sustainability issues relating to the maintenance and renewal of assets, PoMC's financial sustainability ratios indicate a short-term issue, based on the liquidity ratio. While this liquidity issue has existed in each of the past five years, the risk has been mitigated by PoMC generating significant annual net operating cash inflows that have enabled it to meet commitments as and when they fall due. This includes using its surplus cash to pay down debt, and the first payment to the state of an annual Port Licence Fee of $75 million in 2012–13.

At 30 June 2013, PoMC reported an operating surplus after income tax equivalent of $65.9 million. It generated $344.8 million in revenue and had operating expenses of $278.9 million, including $75.8 million of depreciation. Over the long term, our indicators of financial sustainability (self-financing and capital renewal ratios) show a low financial sustainability risk.

3.5.4 State Sports Centre Trust

In our report Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2010–11 Audits, we reported that the State Sports Centre Trust (SSCT) held property, plant and equipment valued at $247 million at 30 June 2011, but did not have the ability to generate sufficient revenue to maintain and renew its asset base.

At 30 June 2013, SSCT's financial sustainability had not improved. It reported a deficit of $6.7 million, which included a depreciation expense of $7.5 million. SSCT's non‑current asset base had grown to $323 million at 30 June 2013 principally because of the transfer of new assets to SSCT on that date.

With the acquisition of the new assets in 2012–13, SSCT's unfavourable financial sustainability is likely to be exacerbated as the limited funds it has for asset renewal and maintenance will need to cover more assets. This increases the risk that services provided by SSCT, or access by the community to the centre, will be affected.

3.5.5 Victorian Arts Centre Trust

The Victorian Arts Centre Trust (VACT) has had a high financial sustainability risk rating each of the past five years due to unfavourable indicators for underlying result, capital replacement and self-financing. In July 2012 the redeveloped Hamer Hall was opened, and VACT took over responsibility for running the food and beverage facilities within the hall. This has had an adverse effect on VACT's cash flow.

VACT's financial sustainability reached a critical point in 2012–13, with immediate action required to enable it to remain financially viable, and meet its obligations as and when they fall due. These financial challenges were acknowledged in the VACT Annual Report, which reported a deficit of $22.6 million for 30 June 2013, including a depreciation expense of $15.4 million. In its 2012–13 Annual Report, VACT noted that:

'Arts Centre Melbourne faces a major challenge in that over many years it has generated and received insufficient funds to meet basic maintenance and infrastructure costs and has needed to draw on its reserves to fund the expenditure. A major restructuring of recurrent expenditure has been undertaken and the 2013–14 budgets have been developed on this scaled back process.'

Recommendation

1. The Department of Treasury and Finance should review the funding model to address the consequential financial sustainability risks for self-funded entities.

4 Use of contract and temporary staff

At a glance

Background

Portfolio departments engage contract and temporary staff, in addition to ongoing staff, to deliver public services and generate economic benefit. In this Part we report on the use of contract and temporary staff across the 11 portfolio departments during 2012–13.

Conclusion

Portfolio departments engage contract and temporary staff for extended periods of time, potentially understating workforce size and increasing costs, in a time of budget constraint and downsizing. Controls over the appointment and management of contract and temporary staff need to be robust and numbers actively monitored.Findings

- Portfolio departments were unable to provide complete and accurate information on the number and cost of contract staff engaged across the 11 portfolio departments, reducing the ability of the state, or individual portfolio departments, to monitor the use of contract staff.

- It is unclear whether individuals employed as contract staff for extended periods, are legally 'employees' entitled to accrue employee benefits.

- Temporary staff engaged in excess of 12 months may be replacing permanent staff and reducing employee numbers to meet the Sustainable Government Initiative staff reduction targets.

Recommendations

- All portfolio departments should have policies for engaging contract and temporary staff, and include a clear definition for each.

- Portfolio departments should obtain legal advice on whether individuals employed over long periods are legally contract staff or employees and address any financial consequences.

- Portfolio departments should conduct and document periodic performance reviews for all contract staff, and specifically before determining whether to extend contracts.

4.1 Introduction

Portfolio departments use a variety of employment arrangements to deliver services to the public and generate economic benefit. In addition to permanent or ongoing staff, they engage consultants or contract and temporary staff, including staff sourced through labour hire firms.

In December 2011, the government announced the Sustainable Government Initiative aimed at delivering an efficient, responsive and sustainable public service. The initiative required the reduction of 3 600 employees across the Victorian public sector, including 2 815 full time equivalent positions from the 11 portfolio departments.

Reducing staff numbers increases the risk that portfolio departments may look to increase the use of contract and temporary staff in order to deliver the services for which they are funded. Such practices can give the appearance that staff numbers are being cut and savings achieved. It is therefore important that adequate controls exist over hiring practices, the engagement and remuneration of contract and temporary staff, and the monitoring of their performance.

In this Part we report on the use of contract and temporary staff during 2012–13, focusing on the policies, management practices, and governance and oversight of the 11 portfolio departments. Our examination includes the Department of Planning and Community Development and the Department of Primary Industries, both of which ceased to exist on 1 July 2013.

4.1.1 Key definitions

To enable meaningful comparison of data and practices across the 11 portfolio departments, we used the definitions of contract and temporary staff included in Figure 4A.

The use of consultants is not addressed in this report, and so the definition of consultant is provided for information purposes only. Consultants were excluded from our analysis because they typically provide services involving skills or perspectives that would not normally reside within a portfolio department. For this reason consultants are less likely to be used to take the place of staff made redundant under downsizing initiatives.

Figure 4A

Key definitions used in this report

|

Term |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Contract staff |

An individual engaged:

The daily work undertaken by the individual is under the direct management and control of the portfolio department. |

|

Temporary staff |

An individual engaged through a labour hire firm on behalf of the portfolio department usually at short notice to fill a gap, or for a specific skill for a short- or long-term project. |

|

Consultant |

An arrangement where an individual or organisation is engaged:

|

Source: Guidance note for Financial Reporting Direction 22C Standard Disclosures in Report of Operations and the Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

4.2 Conclusion

We were unable to obtain complete and accurate information on the number and cost of contract staff engaged across the 11 portfolio departments, because of the lack of data and centralised records, and inconsistencies in the data due to differing definitions used by portfolio departments. The ability of the state and individual portfolio departments to monitor the numbers of, and spending on, contract staff is therefore reduced. Three portfolio departments were unable to determine the number and cost of contact staff they engaged in 2012–13.

Contract and temporary staff were engaged for extended periods, suggesting that these resources were being used to fill permanent roles. This has legal and cost implications for portfolio departments, is not consistent with the government's policy aims, and understates the size of the public sector workforce. In a time of budget constraints and downsizing of staffing, controls over the appointment and management of contract and temporary staff need to be robust.

4.3 Framework for managing contract and temporary staff

An effective framework should enable portfolio departments to manage their use of contract and temporary staff. Drawing on the Victorian Government Purchasing Board (VGPB) polices, related Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) guidelines and reporting requirements, and the Financial Reporting Directions issued under the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA), Figure 4B outlines the key elements for effectively managing contract and temporary staff.

Figure 4B

Key elements for effectively managing contract and temporary staff

|

Component |

Key Elements |

|---|---|

|

Policy |

A policy exists for contract and temporary staff and:

The policy is reviewed and approved by the Secretary or a delegate. |

|

Management practices |

Contract and temporary staff are monitored and authorised in line with policy and procedures. Declarations of interest are assessed. A complete and accurate list of contract and temporary staff is maintained. Extensions for contract and temporary staff are approved, consistent with policy and procedures and VGPB guidelines. Performance against contract targets are assessed and action is taken if performance is below expectations. Regular reports are provided to senior management, the Secretary or a delegate. |

|

Governance and oversight |

Compliance with policy requirements is monitored. Senior management are directed to areas of concern. Risks associated with contract and temporary staff are assessed and mitigating action is taken. Contract and temporary staff policies are periodically reviewed and approved. Internal auditors are engaged to review compliance with policy and processes, and recommend opportunities for improvement. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

We analysed the practices at the 11 portfolio departments against the elements in Figure 4B. The results of our analysis are presented below. The results for contract and temporary staff are reported separately because of the different approaches we found to their appointment and management.

4.4 Contract staff

4.4.1 Policy

Seven of the 11 portfolio departments had a policy which addressed the engagement of contract staff. These policies could be strengthened by including details on:

- time parameters for the engagement of contract staff

- the nature and regularity of reporting on the performance of contract staff

- conflicts of interest declarations to be made by contract staff

- the frequency of policy updates and review.

The departments of Health, Human Services, Justice, and Treasury and Finance did not have policies on engaging and managing contract staff. This increases the risk that contract staff may be engaged where not required, potentially costing the portfolio department more than another solution. It could also lead to contract staff being appointed through processes that are not transparent or appropriate, or are inconsistent with procurement rules.

Definition of contract staff

A review of the definition of 'contract staff' across the 11 portfolio departments revealed that:

- there was not a consistent definition

- the definition was at times ambiguous

- only two portfolio departments applied the definition set out in the Minster for Finance's Financial Reporting Direction 22C Standard Disclosures in Report of Operations (FRD 22C).

The lack of a consistent definition across the portfolio departments contributed to them being unable to identify how many contract staff they had. Further, because they are unable to clearly define 'contract staff' it is likely that disclosures required to be made by portfolio departments about consultants under FRD 22C, do not comply with those requirements.

4.4.2 Management practices

List of contract staff

A central list or register of contract staff is a key tool to record and track contract staff engaged by a portfolio department. Only the departments of Health and Justice maintained a central register of all contract staff for the period reviewed. A further three portfolio departments maintained registers covering part of their organisations.

Eight portfolio departments were able to provide complete lists of contract staff for auditing. However, the departments of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), Environment and Primary Industries (DEPI), and Primary Industries (DPI) were unable to do so.

This means that neither the number of contract staff engaged, nor the total amount spent on them, could be identified across the 11 portfolio departments. The ability of the state as a whole, or of individual portfolio departments, to monitor spending on contract staff, or the number engaged, is therefore limited.

Due to the lack of information, we were unable to analyse the pattern of related spending, and cannot draw any conclusions on the trends in contract staff use, or determine whether the numbers have increased following the recently imposed reductions in Victorian public sector employees.

Engagement of contract staff

We reviewed the records for 35 individuals engaged under contract across the eight portfolio departments able to provide a list of contract staff. Sixteen (46 per cent) of the 35 were engaged to assist with information technology projects, and 14 (40 per cent) assisted on major projects such as the development of hospital and transport infrastructure. The total value of current contracts for the 35 individuals totalled $16.6 million. These contracts may span more than one financial year.

The contract staff had been engaged by portfolio departments for periods ranging from one day to 15 years, with:

- 10, or 29 per cent, engaged for less than a year

- 15, or 43 per cent, engaged for between one and five years

- six, or 17 per cent, engaged for between five and 10 years

- four, or 11 per cent, engaged for more than 10 years.

Over half of the 35 had had contract extensions, some for significant periods, and had become akin to members of portfolio department staff rather than contract staff. This suggests that contract staff are being used to replace employees, rather than for specific purposes.

In our reports Payments to Visiting Medical Officers in Rural and Regional Hospitals, tabled in May 2012, and Managing Major Projects, tabled in October 2012, we raised the need for agencies to properly assess contract and employee relationships. Employees are entitled to benefits such as sick leave, long service leave and redundancy payments. Such benefits are not available to contract staff.

It is important for portfolio departments to ensure that individuals are appropriately remunerated and receive employment benefits commensurate with their employment status and that the appropriate taxation provisions are applied. The Fair Work Act 2009 (Commonwealth) provides for civil remedies where an employer misrepresents employment as independent contracting.

Accordingly, portfolio departments should review individuals employed under contract to ascertain if they should be more correctly classified as employees and entitled to employee benefits. This action is especially important where staff have been engaged under contracts for long periods of time.

Reviewing contract staff performance

Our review of the 35 contract staff revealed that performance reviews had not always been documented by the eight portfolio departments. Documented performance reviews were sighted for only five individuals.

Portfolio departments indicated that verbal feedback is often provided, particularly around project milestones. However, in the absence of documentation, there is no evidence that portfolio departments penalise poor work or missed milestones, or consider performance when making decisions about extending contracts.

Conflicts of interest declarations

Only nine of the 35 contract staff (26 per cent) had signed a conflict of interest declaration relating to their engagement with the portfolio department. It is unclear how, or whether, portfolio departments had satisfied themselves that no perceived or real conflict of interest existed, or whether there was a risk that needed to be managed, as a result of engaging the individual.

4.4.3 Governance and oversight

The portfolio departments with policies relating to contract staff reviewed the policies periodically and updated them when required.

Risks around the engagement of contract staff were considered by senior management at most portfolio departments, the most common risk being that a former employee who received a voluntary departure package would return to work as a contract staffer. Other risks identified and managed included:

- monitoring spending against the contract

- tax compliance.

It is encouraging that senior management are engaged in identifying and mitigating the risks associated with engaging contract staff. However, without an overall understanding of the number and value of the contract staff utilised by the portfolio department, management's ability to mitigate these risks is limited.

4.4.4 Contract staff with significant management responsibilities

Of the 11 portfolio departments, five disclosed in their financial statements that they had contract staff with significant management responsibilities at 30 June 2013, in accordance with Financial Reporting Direction 21B Disclosures of Responsible Persons. A total of 21 contract staff in this category were disclosed.

Two contract staff engaged by the Department of Health (DH) during the 2012–13 financial year have been appointed in positions that were allocated financial delegations. Contract staff must have authorisation from the Minister for Finance before becoming a financial delegate. Neither of the two contract staff had such authorisation, and the portfolio department was therefore in breach of the FMA, although neither had approved payments. Action to correct this breach is underway by the portfolio department.

4.5 Temporary staff

Temporary staff may be engaged by portfolio departments, usually at short notice, to fill a gap or to provide a specific skill for a short period. Unless exemptions apply, portfolios departments are required to source temporary staff from the labour hire firms listed on the State Purchase Contract established by DTF. Temporary staff are paid directly by the labour hire firm from whom they are engaged and are not employees of the portfolio department.

The portfolio departments pay a fee to the labour hire firm for the use of temporary staff. The fee covers the direct labour cost as well as a premium or a loading. Portfolio departments do not accrue employee benefits, such as long service or annual leave, for temporary staff. Employee costs such as superannuation payments or payroll tax are paid for by the labour hire firm, with these costs charged to the portfolio department as part of the premium.

4.5.1 Cost of labour hire contracts

In 2012–13, a total of $160.1 million was spent on labour hire firms across all portfolio departments, a decrease of 14.8 per cent, from the $187.8 million spent in 2011–12. In both years, the expenditure on labour hire firms was equivalent to 2 to 2.5 per cent of portfolio departments' employee related expenditure. On-costs, such as commissions to the labour hire firm account for 24.6 per cent of the payments made to firms.

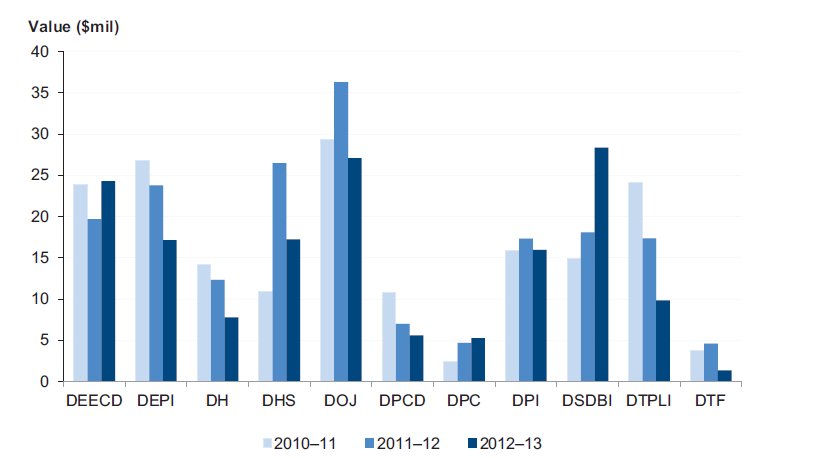

Figure 4C shows the total amount paid by portfolio departments to labour hire firms between 2010–11 and 2012–13.

Figure 4C

Total amounts paid by portfolio departments to labour hire firms, 2010–11 to 2012–13

Note: The costs for DEECD and the Department of Transport, Planning and Local Infrastructure (DTPLI) exclude the cost of temporary staff associated with capital projects for each of the three years. In 2012–13, this type of temporary staff cost an additional $13.7 million for DEECD and $6.7 million for DTPLI.

Note: DOJ – Department of Justice, DPC – Department of Premier and Cabinet, DSDBI – Department of State Development, Business and Innovation.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 4C shows that most portfolio departments spent less on labour hire in 2012–13 than for the preceding two financial years. The three exceptions were DEECD, the departments of Premier and Cabinet and State Development, Business and Innovation (DSDBI). These increases relate to temporary staff engaged on major projects during the financial year, such as the Ultranet and the Enterprise online assessment system at DEECD, and the Global Engagement Management System at DSDBI.

It is positive that, with the exception of one case identified at DH, all portfolio departments engaged temporary staff using the State Purchase Contract. In the DH case, corrective action has been taken.

4.5.2 Policy

Guidance on the use of labour hire firms is contained within the DTF guidelines related to VGPB policies. However, relying on this guidance alone is not sufficient as it is not tailored to the particular circumstances and needs of the individual portfolio departments.

Five portfolio departments had no policy specific to their engagement and management of temporary staff. The five had no basis for providing consistent guidance about the use of temporary staff, leaving decisions about their engagement and use to individual work teams. This may result in temporary staff being appointed inappropriately and inconsistent practices.

To address this issue an entity's policy, as a minimum, should encompass:

- the documentation to be completed and information to be obtained at the time of engaging temporary staff, including information about the individual, the terms of the engagement and the roles and responsibilities of the labour hire firm, the portfolio department and the individual

- authorisation and approval requirements

- notification to the portfolio departments' human resources unit so that key information can be collected or disseminated

- induction requirements

- data security requirements and access controls

- actions to be taken on departure of the individual from the portfolio department.

4.5.3 Management practices

Six portfolio departments were able to provide a temporary staff listing for auditing. The remaining five experienced difficulties, as they had no central area of responsibility or listing for recording the temporary staff engaged within the portfolio department.

Under DTF guidelines related to VGPB policies, portfolio departments are required to nominate a staff member to manage the engagement of temporary staff across the organisation. The staff member has the responsibility to:

- distribute a quarterly report from the seven labour hire firms, provided by DTF, to relevant staff within the portfolio department

- be the main point of contact with DTF and a conduit for communications with the portfolio department

- communicate State Purchase Contract operating arrangements to users.

DTF, as the lead portfolio department for the State Purchase Contract, formally reviews the contract each quarter with each labour hire firm and a liaison from each portfolio department. This provides the state with central oversight of temporary staff expenditure.

As part of this process, a quarterly report detailing all temporary staff engaged is provided to the portfolio departments for review. However, we found that this report was not always utilised by portfolio departments to assist with the management of their temporary staff.

Engagement of temporary staff