Prevention and Management of Drug Use in Prisons

Overview

There is a strong relationship between excessive alcohol and other drug (AOD) use with criminal activity and reoffending. Prisoners have poorer levels of physical and mental health than the general population, with excessive AOD use being a primary contributor. Therefore preventing access to AOD while in prison and effectively treating and addressing AOD problems is likely to assist in the rehabilitation of prisoners, reduce future offending and improve prisoners' health outcomes.

This audit assessed the effectiveness of the strategies and programs implemented by the Department of Justice, through Corrections Victoria and Justice Health, to reduce the supply of, demand for, and harm caused by drugs in prisons.

The audit found that despite the high numbers of prisoners entering the prison system with drug problems, Corrections Victoria is generally effective at preventing drugs from entering prisons and detecting drugs that get past its barrier controls. Both Corrections Victoria and Justice Health are also appropriately identifying and managing prisoners with drug issues. However, the Department of Justice needs to place greater emphasis on performance reporting and evaluation to be able to determine just how effective its drug-related strategies and programs are.

Prevention and Management of Drug Use in Prisons: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2013

PP No 266, Session 2010–13

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Prevention and Management of Drug Use in Prisons.

This audit assessed the effectiveness of the strategies and programs implemented by the Department of Justice—through Corrections Victoria and Justice Health—to reduce the supply of, demand for, and harm caused by drugs in prisons.

The audit found that Corrections Victoria is generally effective at preventing drugs from entering prisons and detecting drugs that get past its barrier controls. Both Corrections Victoria and Justice Health are also appropriately identifying and managing prisoners with drug issues. However, the Department of Justice needs to place greater emphasis on performance reporting and evaluation to be able to determine just how effective its drug-related strategies and programs are.

Yours faithfully,

John Doyle

16 October 2013

Auditor-General's comments

Auditor-General |

Audit team Chris Sheard—Sector Director Ryan Czwarno—Team Leader Matthew Irons—Analyst Hayley Svenson—Analyst Kristopher Waring—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Around 70 per cent of Victoria's prisoners have used drugs before entering the prison system, and many of these people enter prison without their problematic drug use being addressed. It is not surprising, therefore, that demand for prohibited drugs remains despite these secure environments.

Given the high number of prisoners entering prisons with problematic drug use, completely eliminating prohibited drugs from entering prisons is unrealistic. It would essentially mean stopping prisoner visits, which are an essential part of prisoner rehabilitation and maintaining community and family connections. It is therefore incumbent on prison managers to prevent, as far as possible, drugs from entering their prisons while also working with prisoners to address their drug use. This is consistent with the harm minimisation approach.

In this audit, I looked at how the Department of Justice, through Corrections Victoria and Justice Health, prevents drugs from entering the prison system, detects drugs that get past prison barrier controls, and manages and treats prisoners with drug problems.

I am assured that Corrections Victoria's controls are, for the most part, effective at preventing the use of and detecting prohibited drugs. I am also assured that Corrections Victoria and Justice Health identify prisoners with ongoing drug problems and that the prisoners are able to access treatment to address their drug using behaviour.

Weaknesses in performance reporting, evaluation and risk management practices mean that the Department of Justice is not appropriately positioned to know whether its prevention and detection controls, or its management and treatment programs are as effective or efficient as they could be. These are areas that the Department of Justice has recognised it needs to improve and it has started to make changes.

The challenge for the Department of Justice will be to maintain the effectiveness of its drug prevention, detection and treatment activities in light of increasing prisoner numbers and capacity constraints across Victoria's prison system—the subject of VAGO's 2012 audit, Prison Capacity Planning.

I have made six recommendations that will assist the department in determining the effectiveness and efficiency of its prevention and management of drug use in prisons. It is pleasing that the department has accepted my recommendations and committed to a reasonable timetable to implement them.

I would like to thank departmental staff for their assistance and cooperation during this audit, and I look forward to receiving updates on their progress in implementing the recommendations.

Auditor-General

Audit Summary

The link between alcohol and other drug (AOD) use and crime is well established, with a high correlation between excessive alcohol and illicit drug use and criminal activity and reoffending. A 2012 study found 54 per cent of discharged prisoners reported drinking alcohol at unsafe levels prior to their recent imprisonment, 70 per cent of prison entrants used illicit drugs during the preceding 12 months and 44 per cent had injected drugs.

Excessive AOD use is one of the primary contributors to poor health. Prisoners have poorer levels of physical and mental health than the general population, with a higher prevalence of disease and major mental illness. Preventing access to AODs while in prison and effectively treating and addressing AOD problems is therefore likely to assist in the rehabilitation of prisoners, reduce future offending and improve prisoners' health outcomes.

The Department of Justice (DOJ), through Corrections Victoria (CV) and Justice Health (JH), is responsible for the administration of Victoria's prisons, including preventing drugs from entering the prison system and managing and treating prisoners with drug problems.

The audit examined the strategies and programs implemented by CV and JH to reduce the supply of, demand for, and harm caused by drugs in prisons. It also considered CV and JH's monitoring and evaluation of the strategies and programs, and their effectiveness.

Conclusions

Despite the high numbers of offenders entering the prison system with drug problems, less than 5 per cent of prisoners have tested positive to drug use while in prison over the past 10 years. This suggests that the drug controls in Victoria's prisons have been effective in preventing drugs from entering prisons and detecting drugs that get past its barrier controls.

The processes for identifying prisoners who use drugs are generally effective and provide confidence that prisoners with ongoing drug problems are identified and their drug‑using behaviour is managed.

However, weaknesses in performance reporting and evaluation means that DOJ cannot determine the overall effectiveness and efficiency of its initiatives to manage drug use in prisons, or determine whether prevention and detection controls are as effective and efficient as they could be.

Findings

Level of drug use in prisons

The level of drug use detected through urinalysis testing randomly conducted across the prison population has remained below 5 per cent in each of the past 10 years.

There has been a marked increase in the detected use of buprenorphine—a drug used for opioid substitution therapy to treat heroin addiction. buprenorphine was the most commonly detected drug used illicitly by prisoners in 2012–13, accounting for 57.7 per cent of all positive urinalysis tests.

Preventing and detecting drug use

Effectiveness and adequacy of drug prevention and detection controls

While prison drug controls have resulted in low rates of detection for illicit drug use, DOJ is not in a position to assure itself or other stakeholders that its drug controls are as efficient or effective as they could be. This is largely because CV's framework for measuring the effectiveness of existing controls is weak. It is also unclear whether the controls are appropriately targeted at the highest risks, and informed by effective prison intelligence.

CV has reviewed its performance reporting and, during the course of the audit, has begun to implement a new reporting framework. CV has also begun work to address the specific strategic risks at each prison and to improve its intelligence capabilities.

Balancing drug controls and prisoner management

CV's aim is to balance the humane treatment of prisoners and the prevention and detection of drugs in prison. CV does not have an auditable framework to determine what constitutes the right balance, nor does it have a process to assess whether its policies or procedures too greatly favour one element over another.

CV uses random general urinalysis performance benchmarks as a proxy indicator to determine whether prisons are getting the balance right. However, anomalies between the benchmarks for each prison and the methods by which the benchmarks are set undermine the usefulness of the indicator as a proxy.

Drug prevention and detection controls

CV has comprehensive procedures that set the minimum standards that prisons and staff must comply with to prevent drugs from entering prisons, to know how to detect drugs that are inside prisons and what to do with drugs once they have been detected. The procedures are prescriptive, clear and sufficiently detailed.

CV also has sound barrier controls in place to prevent drugs from entering prisons. These controls include processes for monitoring visitors, the use of ion scanners, and conducting routine prisoner searches. CV should use the Security and Emergency Services Group (SESG)—CV's security operations staff including those that handle its drug detection dogs—more strategically. During the course of this audit, CV has begun to implement an intelligence and risk-based approach to allocating SESG searches across public prisons.

CV and prisons also have controls to detect drugs and drug use within prisons. These controls allow prison staff to seize drugs to prevent further use, and identify drug users so that they can be appropriately managed and treated. CV relies on two main controls to detect drug use and the presence of drugs in prisons—searches by prison staff and SESG, and its urinalysis testing programs. The large volume of drug tests conducted by CV provides reasonable assurance that prisons are identifying prisoners who are using drugs.

Given the prevalence of prisoners illicitly using buprenorphine, prisons also have processes to prevent prisoners from diverting prescription medications, in order to limit trafficking and misuse.

Identifying and treating drug users

Identifying and managing prisoners with drug problems

CV and JH identify prisoners with drug problems on arrival at a prison and during the course of their sentence. Assessments of prisoners' health and offending risk factors are used to identify prisoners with drug problems on arrival at a prison, while drug detection methods are used to identify prisoners with drug problems while in prison. Combined, these provide an adequate system to identify prisoners with drug problems within the prison system.

CV and JH have a broad range of evidenced-based programs to manage and treat prisoners' AOD problems, including:

- Identified Drug User program

- Drug Free Incentive Program

- AOD treatment programs

- Opioid Substitution Therapy Program

- Hepatitis C treatment.

However, neither CV nor JH can provide assurance that these programs have been effective in reducing incidence of drug use or drug-related harms due to the shortcomings of performance measurement and program evaluation.

JH's recent work on expanding hepatitis C treatment demonstrates that it is seeking to maintain the currency of its treatment regime as new evidence and treatments emerge. Despite the high rates of communicable diseases in prisons and the strong evidentiary basis for needle and syringe programs, Victoria's prisons do not have needle and syringe programs.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice:

- establish robust performance reporting frameworks to assess the effectiveness of its barrier control and drug detection initiatives

- develop and document risk management practices across all its public prisons to identify and manage prison-specific strategic risks

- develop and document a framework to guide it in determining the balance between drug prevention and detection controls, and prisoner management needs

- review and update the random general urinalysis benchmarks in light of prison-specific risks and the 'balancing' framework

- establish robust performance reporting frameworks to assess the effectiveness of its drug treatment and management programs

- evaluate the effectiveness of all alcohol and other drug programs including the Identified Drug User program, Drug Free Incentive Program and the Opioid Substitution Therapy Program.

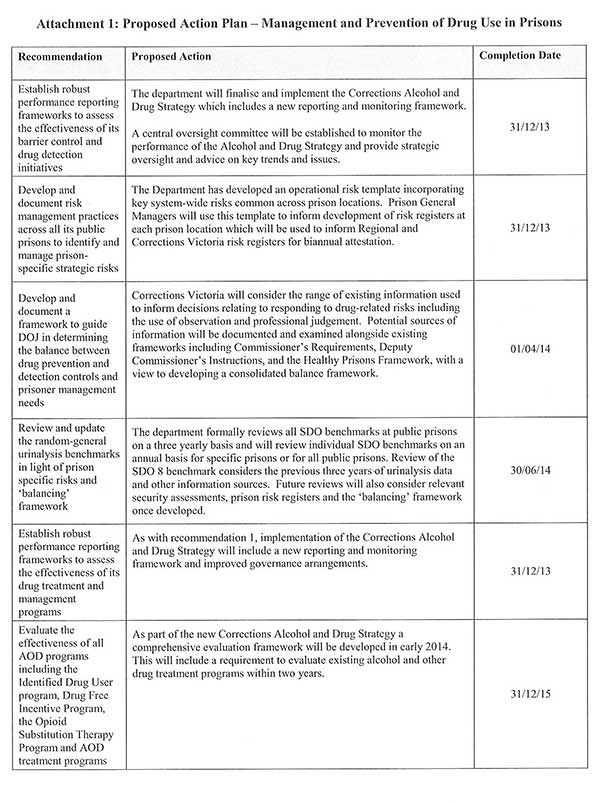

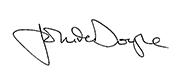

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Justice with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Drugs and prisons

Offenders with alcohol and other drug (AOD) problems are one of the criminal justice system's main challenges, with a high correlation between excessive alcohol and illicit drug use, and criminal activity and reoffending.

A study of the health of Australia's prisoners in 2012 found that 54 per cent of discharged prisoners reported drinking alcohol at unsafe levels prior to their recent imprisonment, 70 per cent of prison entrants used illicit drugs during the previous 12 months and 44 per cent had injected drugs. Research into alcohol and drug use by police detainees across Australian jurisdictions in 2009–10 found that 66 per cent of detainees who were drug tested had used at least one drug in the 48 hours prior to their arrest and 45 per cent indicated that substance use contributed to their current offences.

Based on these patterns of drug use, many prisoners start their period of imprisonment with drug problems. Untreated or undiagnosed drug problems can result in demand for drugs in the prison system, which creates a range of risks and challenges for prisoners, prison staff and the community. The use of drugs in prisons is associated with increased violence, occupational health and safety risks and corruption. Additionally, prisoners may use threats or commit acts of violence against other prisoners and staff to obtain drugs, and drug debts and withdrawal symptoms can lead to further violence.

1.1.1 Drugs and prisoner health

Prisoners have poorer physical health and a greater likelihood of disease than the general population. In addition, prisoners generally have worse mental health than the general population, with a higher prevalence of major mental illnesses such as depression, anxiety and addiction. One of the primary contributors to poor health is drug use, which can lead to both physical-health and mental-health issues.

Injecting‑drug use by prisoners is particularly unsafe, as prisoners typically have little access to safe, sterile needles. Prisoners therefore may engage in unsafe injecting practices such as needle sharing, which can lead to negative health effects including the spread of bloodborne diseases, bacterial infections, thrombosis, collapsed veins, endocarditis, tetanus and septicaemia.

The most prominent and dangerous bloodborne diseases in prisons are the hepatitis B and C viruses. Exposure to hepatitis C in Australia usually comes through sharing drug injecting equipment, while for hepatitis B it is through both unprotected sex and sharing injecting equipment. Although hepatitis C is more severe, both diseases affect the liver and can lead to liver disease, liver cancer and, ultimately, death.

The prevalence of hepatitis C infection in Australian custodial settings is estimated to be between 23 per cent and 47 per cent compared with an estimated national prevalence of 1.4 per cent. Of Australian prison entrants tested for hepatitis B in 2010, 19 per cent tested positive. In comparison, approximately 9 per cent in the general community have hepatitis B.

1.2 Amount of drug use in prisons

Corrections Victoria (CV) uses its random general urinalysis testing program to determine the extent and type of drug use at each prison and across the prison system. Each week, 3 per cent of prisoners in public prisons and 1.25 per cent of prisoners in private prisons are randomly selected and required to submit to a urine test.

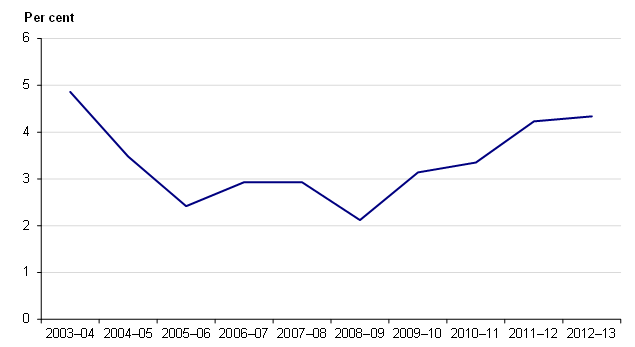

Figure 1A

Percentage of positive random general urinalysis drug tests

across the prison system, 2003–04 to 2012–13

Note: Urinalysis

drug test results for 2012–13 are provisional.

Source: Victorian

Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Justice.

The percentage of positive random general urinalysis tests across the prison system has increased each year since the lowest rate of 2.12 per cent was returned in 2008–09. The rate of positive random general urinalysis results in 2011–12 and 2012–13, of 4.23 and 4.34 per cent respectively, are the highest since 4.86 per cent of prisoners tested positive in 2003–04.

The yearly random general urinalysis results for each prison—included in Appendix A Figure A1—show that the Melbourne Assessment Prison, the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre (DPFC), and Port Phillip Prison have had the highest rates of illicit drug use among Victorian prisons over the past 10 years. These three prisons have recorded positive random general results of equal to or in excess of 5 per cent in five or more of the past 10 financial years—Melbourne Assessment Prison and DPFC were equal to or above 5 per cent in six financial years and Port Phillip Prison in five financial years. Fulham Correctional Centre's main medium security section was the only medium security prison to exceed 5 per cent in multiple years, doing so four times and with a marked increase in the past two years.

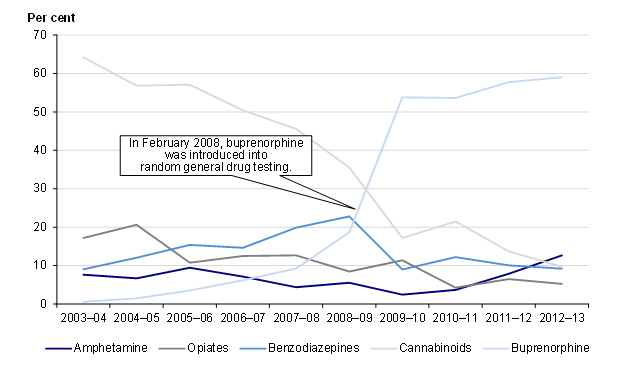

Types of drugs used

It is likely that the low positive urinalysis test results of 2006–07 to 2008–09 do not provide an accurate measure of the extent of drug use in the prison system throughout this time, as buprenorphine—an opioid substitute used to treat heroin addiction that provides the user with some analgesic and euphoric effects—was not regularly tested for during this time. The overall increase since 2008–09 can be partially attributed to the inclusion of buprenorphine in the panel of drugs tested for by CV's urinalysis in February 2008.

As Figure 1B shows, buprenorphine has been the most widely detected drug since it has been regularly tested for. This increase has coincided with decreases or steadying rates of drug use for all other drugs, including a substantial decline in the use of cannabis since 2005–06.

Figure 1B

Types of drugs detected in all positive urinalysis drug tests

across the prison system from 2002–03 to 2012–13

Note: Urinalysis

drug test results for 2012–13 are provisional.

Source: Victorian

Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Justice.

Of the 25 664 total urinalysis tests conducted in 2012–13, 6.6 per cent were positive. Buprenorphine accounted for 57.7 per cent of positive results, while amphetamines and cannabinoids were the second and third most commonly detected drugs, with 12.5 per cent and 9.8 per cent of positive urinalysis results, respectively.

1.3 Preventing and managing drugs in prisons

1.3.1 Managing drug users

General pathway

When prisoners first enter the prison system, they are received at two 'front-end' prisons—Melbourne Assessment Prison for male prisoners and DPFC for female prisoners. During the reception process, prisoners are risk assessed and a sentencing management plan is developed which includes a security classification and a determination on which prison a prisoner will be classified to based on factors such as risk, offence type and criminal history.

All prisoners are generally first classified as maximum security prisoners, with reductions in classification based on a prisoner's behaviour. For male prisoners this means beginning their sentence at one of the maximum security prisons before possibly progressing through to medium security prisons and eventually minimum security prisons before being released. For female prisoners, DPFC is the larger of the two female prisons and holds prisoners of all classification types. This means that most female prisoners are likely to spend their whole sentence at DPFC, while some prisoners will complete their sentence at the minimum security Tarrengower Prison.

The prison system has a total funded capacity of 5 525 beds across 14 prison facilities as at 30 June 2013. There are 11 public prisons, two privately operated prisons and a transition centre for male prisoners.

Figure 1C details the breakdown of the prison system, including the security classification and funded bed capacity of each prison, as at June 2013.

Figure 1C

Victoria's prisons at 30 June 2013

| Prison | Security level |

Public/Private |

Funded capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Men's prison system |

|||

Barwon Prison |

Maximum |

Public |

459 |

Melbourne Assessment Prison |

Maximum |

Public |

285 |

Metropolitan Remand Centre |

Maximum |

Public |

723 |

Port Philip Prison |

Maximum |

Private |

934 |

Fulham Correctional Centre |

Medium |

Private |

845 |

Hopkins Correctional Centre |

Medium |

Public |

388 |

Loddon Prison |

Medium |

Public |

409 |

Marngoneet Correctional Centre |

Medium |

Public |

394 |

Beechworth Correctional Centre |

Minimum |

Public |

160 |

Dhurringile Prison |

Minimum |

Public |

268 |

Langi Kal Kal Prison |

Minimum |

Public |

219 |

Judy Lazarus Transition Centre |

Minimum |

Public |

25 |

Total |

5 109 |

||

|

Women's prison system |

|||

Dame Phyllis Frost Centre |

Maximum |

Public |

344 |

Tarrengower Prison |

Minimum |

Public |

72 |

Total |

416 |

||

Prison system total |

5 525 |

||

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Justice.

Drug users' pathways

Prisoners with drug problems will generally take a similar pathway through the prison system as other offenders, depending on the type and severity of their drug use prior to entering prison and during their sentence.

Prisoners who have been taking opioid substitution therapy to treat a heroin addiction while in the community can continue that treatment in prison. Prisoners can also begin the Opioid Substitution Therapy Program (OSTP) during their prison sentence. Approximately 17 per cent of prisoners are receiving OSTP treatment. A prisoner being on OSTP will generally not influence what prison they are sent to as part of their sentence.

However, if a prisoner is identified as a drug user during their sentence, they will be given an Identified Drug User (IDU) status. Getting an IDU status may impact on a prisoners' pathway through the prison system as such prisoners will be subject to disciplinary action, which may include transfer to a different prison. Prisoners with an active IDU status will not be transferred to a minimum security prison and will be moved from a minimum security prison if they acquire an IDU status.

Prisons also have treatment programs for prisoners with drug problems. Marngoneet Correctional Centre was designed as a therapeutic treatment prison and prisoners may be transferred there to participate in its intensive drug treatment programs.

1.3.2 Roles and responsibilities

Corrections Victoria

CV is a business unit within the Department of Justice (DOJ) and is responsible for managing Victoria's prison system. CV sets the strategy, policy and standards for the management of all correctional facilities, including operating the public prisons and administering the contracts of the two private prison providers.

A key element of its prison management activities is preventing drugs from entering prisons, and detecting drugs within prisons. It does this through:

- searching visitors, prisoners and staff

- limitations on visit types

- searches of prisoner visit centres and visitor car parks

- barrier controls such as ion scanners and drug detection dogs

- intelligence operations

- searches within prisons including of prisoner cells and common areas

- randomand targeted urinalysis drug testing of prisoners.

Justice Health

Justice Health (JH) is also a business unit of DOJ and is responsible for the delivery of health services in the prison system. The health services are contracted out to health service providers and JH is responsible for setting the policy and standards for health care, managing the contracts and monitoring and reviewing service provision.

JH, through these contracted services, provides AOD treatment programs designed to manage prisoners' drug problems while they are incarcerated. Drug treatments include access to opioid substitution therapy and behavioural change programs.

1.3.3 Policy

Victorian Prisoner Drug Strategy 2002

The Victorian Prisoner Drug Strategy 2002 (VPDS) is DOJ's policy framework that guides CV and JH's approach to drugs in prisons. The aim of the strategy is to 'prevent drugs entering Victoria's prisons and to minimise the harm caused by drugs to prison staff, prisoners and society'. VPDS has four main goals—supply control, detection and deterrence, treatment, and health and safety.

VPDS signalled a shift in government policy that has occurred in other Australian jurisdictions away from 'zero tolerance' or abstinence—by reducing the level of drug use to create a drug-free prison environment through detection, deterrence and law enforcement—towards 'harm minimisation'. This change in policy approach recognised that given the entrenched drug‑using behaviours of some prisoners, it is unlikely that all prisons are going to be drug-free and that drugs do get in to prisons despite prevention efforts. Further, to operate a modern humane prison system that meets legislative and correctional standards, it is not possible to implement highly restrictive controls—such as stopping or greatly reducing prison visits—to keep drugs entirely out of the prison system.

By adopting harm minimisation as the theoretical framework of VPDS, DOJ aims to minimise 'the health, social, legal and economic harm caused by drugs by acknowledging that drug taking exists and that there is a benefit to be gained by focusing on the harm that may result'.

In putting this framework into practice, DOJ aims to manage a 'balanced' prison system that has controls and procedures to minimise the risks of drugs entering prisons, while operating a prison system that safeguards prisoners' human rights and prepares prisoners for their eventual release back into the community.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess how effectively and efficiently DOJ has prevented the supply of, demand for, and harm caused by, drugs in prisons. To address this objective, the audit assessed how effectively DOJ:

- prevents drugs from entering the prison system and detects drugs within prisons

- identifies and treats prisoners with drug problems

- evaluates, monitors and reports performance.

The audit examined the strategies and programs implemented by CV and JH to reduce the supply of, demand for, and harm caused by drugs in prisons. It considered the strategies and programs in the context of the goals and guiding principles of VPDS. It also considered CV and JH's monitoring and evaluation of the strategies and programs, and their effectiveness.

The audit examined CV's and JH's performance in relation to drugs that are prohibited in prisons, and to prescription drugs where their misuse is prohibited. Three prisons, DPFC, Dhurringile Prison, and Marngoneet Correctional Centre, were also examined as part of the audit. These prisons were selected because they represent the three different security classifications of the prison system and include a female prison—DPFC. Marngoneet Correctional Centre was also included because it has a therapeutic treatment focus that includes drug treatment.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit used a range of methods to obtain audit evidence, including document and file review and interviews at the Department of Justice and with management, prison staff and clinicians at the three prisons. The audit also included observation, particularly in relation to drug detection controls.

The audit also analysed data from all prisons to provide a statewide assessment of performance, and key controls for the prevention and management of drugs in prison.

The audit was undertaken between February and August 2013, with evidence collected throughout this period. The data contained within the report ranges from 2002–03 to June 2013.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $390 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the effectiveness of CV's activities to prevent drugs from entering prisons and to detect drugs and drug users in prisons.

- Part 3 examines the effectiveness of CV and JH's activities to identify,manage and treat prisoners with drug problems.

2 Preventing and detecting drug use

At a glance

Background

To maintain good order and minimise the harms associated with drug use, Corrections Victoria (CV) aims to prevent drugs from entering prisons and to detect drugs and drug use inside prisons.

Conclusion

All Victorian prisons use a range of drug prevention controls and drug detection controls. While they vary in their nature and frequency, they are generally effective. However, inadequacies in how CV measures performance and monitors risk within prisons mean that it cannot determine whether it has the right balance of controls for the drug-related risks faced by each public prison.

Findings

- Weaknesses in performance measurement mean that CV cannot assure itself that its strategies to prevent and detect drug use have been as effective as they could be.

- Public prisons do not have adequate risk management processes in place to manage strategic risks, including drug‑related risks. CV is working to address this.

- CV's drug prevention and management controls are influenced by its need to balance drug controls with a humane prison system. However, it does not have an effective, auditable framework to determine whether it has struck the right balance.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice:

- establish robust performance reporting frameworks

- improve risk management practices across all of its prisons

- develop a framework to guide it in determining the balance between drug prevention and detection controls, and prisoner management needs

- reviewthe random general urinalysis benchmarks in line with the risks faced by each prison.

2.1 Introduction

Over two‑thirds of prisoners have used drugs in the 12 months before being incarcerated, and over half are in prison because of drug‑related offences. Given this, the probability of prisoners seeking drugs while in prison is high. Apart from the illegality of drug use in prisons, their use is linked with increased violence, health risks for prisoners, occupational health and safety risks for prison staff, and corruption.

Two of the four goals of the Victorian Prison Drug Strategy 2002 (VPDS) are to prevent drugs from entering the prison system, and to detect drugs and drug use inside prisons.

2.2 Conclusion

All Victorian prisons use a range of drug prevention controls—at the prison 'gate'—and drug detection controls inside the prison. The controls are generally effective at keeping drugs out of prison and detecting drugs that get past existing barrier controls. This is shown in the lower than 5 per cent detection rate over the past 10 years. However, the controls vary in their nature and frequency, and there are weaknesses in how Corrections Victoria (CV) assures itself of the effectiveness and adequacy of its controls.

2.3 Effectiveness of drug controls

Effective drug prevention and detection requires adequate risk-based controls to stop drugs getting into prisons, and to find them when they do get in. It also requires robust performance reporting frameworks to provide information on the effectiveness and efficiency of the controls.

CV does not have an adequate performance reporting framework to assess the effectiveness of its drug prevention and detection controls. It cannot be assured that the controls are adequately mitigating its key drug-related risks, nor that it is appropriately balancing prisoner management needs with the need for drug control.

2.3.1 Assessing drug control performance

VPDS is the key strategy guiding CV's activities to prevent drugs entering the prison system and detect drugs inside prisons. However, the Department of Justice (DOJ) does not have a performance reporting framework to enable it to assess whether it is achieving VPDS' outcomes and objectives, and to assess whether its drug prevention and detection controls are effective and efficient.

In 2002 DOJ committed to establish a reporting framework that could measure the quality and performance of its drug‑related activities, but has only partially done so.

CV reports on its drug prevention and detection activities through its monthly Drugs in Victorian Prisons Report. The monthly reports focus on performance outputs and activities, such as the number and type of drugs seized, the number and percentage of positive random general and targeted urinalysis tests and the walk-through ion scanner results. However, CV does not assess its performance against its drug supply control, and detection and deterrence objectives, nor does it have in place key performance indicators to assist in this assessment.

In August 2012, CV began reviewing VPDS and its performance reporting, and CV has undertaken to implement a new reporting framework. In developing its new performance and reporting framework, CV should develop objectives that are clearly defined and measurable, that focus on the outcomes desired, and which are informed by relevant and appropriate key performance indicators.

2.3.2 Adequacy of drug controls

The relatively low number of detected drug users across the system indicates that drug prevention and detection controls are generally effective. However, there is less assurance around their adequacy to address key drug-related risks. This is because CV cannot demonstrate a sound understanding of prison-specific strategic risks, including drug-related risks.

Risk management

Risk management is central to effective governance and public sector management. It enables agencies to identify and manage their key operational and strategic risks, and understand the likelihood and consequences of risks arising.

Understanding the risks associated with illicit drugs entering, and being used within, the prison system, should enable CV to better target its drug prevention and detection controls.

The risks associated with each prison are likely to vary considerably based on security classification, quality and age of prison infrastructure, prison capacity pressures, and the types of prisoners held. Consequently, each prison will have different strategic and operational risks that require ongoing management and different strategies to mitigate these risks.

Each public prison manages a variety of day-to-day risks by adhering to legislation, prison standards, CV procedures and local operating procedures. While DOJ has risk management frameworks at the agency, region, and department level to support the risk management of each prison, public prisons do not have documented risk management processes. Consequently, CV and prisons cannot be assured that they are adequately identifying and managing prison-specific operational and strategic risks relating to illicit drugs, or whether current controls are adequately mitigating the risks.

CV is addressing this weakness by reviewing the specific strategic risks at each prison, with the view of each prison maintaining a register of strategic risks and the proposed treatment strategies.

Prison intelligence

Drug prevention and detection relies on sound processes linking intelligence with risk assessments and, ultimately, risk-based controls.

CV's intelligence functions have recently been the subject of five separate reviews—two reviews in 2012, a 2011 review, a 2008 review and a 2012 report by Ombudsman Victoria. The reviews were all highly critical of CV's intelligence framework, which was described as 'significantly less mature and developed' than other Australian jurisdictions. They also identified fundamental weaknesses in CV's intelligence capabilities which present 'a range of serious and unacceptable risks for DOJ and for government'.

CV has accepted the findings and recommendations from these reviews and is in the process of implementing actions to address them. CV has reprioritised $2 million per annum from 1 July 2013 to implement a new centralised intelligence model that includes:

- a restructure of intelligence functions

- greater emphasis on intelligence analysis and sharing across the prison system

- a new system-wide database

- improvedtraining and staff capabilities development.

While it is too early to assess the effectiveness of CV's new intelligence model, recent work assessing the infrastructure deficiencies and risks of each prison as well as CV's undertakings to conduct annual operational assessments relating to contraband will potentially provide CV with the opportunity to better incorporate intelligence into its management of system-wide drug-related risks and drug prevention and detection controls.

2.3.3 Balancing drug controls and prisoner management

The adequacy of drug prevention and detection controls is influenced by CV's objective of managing a 'balanced' prison system. CV's aim is to balance the humane treatment of prisoners and the prevention and detection of drugs in prison.

There is a risk that CV can get this balance wrong—being too much in favour of human rights and rehabilitation concerns creates vulnerabilities in barrier controls that increase the opportunities for drugs to enter into the prison system; placing too much emphasis on barrier controls and tougher restrictions may make prisoners more difficult to manage and reduce the effectiveness of their rehabilitation.

CV does not have in place an auditable framework to determine what constitutes the right balance, nor does it have a process to assess whether its policies or procedures too greatly favour one element over another.

CV considers that there is no ideal method to assess whether it is getting the balance right and that it can only assess this by relying on a proxy indicator—random general urinalysis testing—and operating procedures as well as on‑the‑ground experience. Neither the operating procedures nor on‑the‑ground experience provide measurable and objective performance indicators to assess whether the balance is right.

Random general urinalysis performance as a proxy

The use of random general urinalysis performance as a proxy measure relies on the performance benchmarks being set correctly. CV has a process in place to review the benchmarks—public prisons are formally reviewed every three years and were last reviewed in 2010–11, while private prisons are reviewed every five years as part of the contract review process. However, there are anomalies in some of the benchmarks that undermine the usefulness of the indicator as a proxy.

Some of the benchmarks are a result of historical decisions and, in the case of the two privately-operated prisons, the benchmarks have been contractually agreed to. However, it is unclear why some of the significant differences in the benchmarks between prisons of the same security classifications have been maintained.

As shown in Appendix A, Figure A1, the maximum security Barwon Prison has a benchmark of 5.46 per cent, while the privately run Port Phillip Prison has a benchmark of 10.5 per cent. Similarly, the medium security Loddon Prison has a benchmark of 4.97 per cent, while the privately run medium security Fulham Correctional Centre has a benchmark of 11.6 per cent—the highest of all prisons. Fulham Correctional Centre's benchmark remained at 11.6 per cent despite five years of random general urinalysis results below 5 per cent from 2005–06 to 2010–11.

While the prisoner profile for these prisons may include higher numbers of prisoners with drug-related offences, the benchmarks for all prisons need to be reviewed and revised to become realistic targets to drive performance.

2.4 Drug prevention and detection controls

2.4.1 Drug prevention and detection procedures

CV's comprehensive procedures guide prison staff on how to prevent drugs from entering prisons, how to detect drugs and what to do with drugs once they have been detected. These include minimum requirements set out in the Commissioner's Requirements and the Deputy Commissioner's Instructions (DCIs). Privately operated prisons are required to follow Commissioner's Requirements but not DCIs, and instead have their own operating procedures.

The minimum standards with which each prison must comply are based on security classification—minimum, medium or maximum—with a greater level of drug prevention and detection controls required at higher security prisons. Higher security prisons are likely to have more drug activity than lower security prisons because CV will generally not place known drug users in minimum security prisons, and will move detected drug users from minimum security prisons.

CV's policies are prescriptive, clear and sufficiently detailed for prison staff to comply with the minimum standards. They provide direction on:

- what is considered contraband

- how to conduct searches of prisoners, staff and visitors, accommodation areas and vehicles

- how to respond to the discovery of drugs

- how to store and dispose of seized items

- how drug seizures and incidents are to be reported and recorded

- when to call in Victoria Police

- how to conduct urinalysis drug testing.

Local operating procedures

The general managers responsible for operating public prisons have also developed local operating procedures that adapt the DCIs to local conditions. This practice is consistent with CV expectations. The local operating procedures at the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre (DPFC), Dhurringile Prison and Marngoneet Correctional Centre are consistent with the DCIs and modified based on the types of controls and facilities at each prison. This process appropriately allows general managers to reduce the DCIs to staff procedures that are more suited to the specific prison.

Observations by the audit team at the three prisons and reviews of seizure registers and audit registers found these prisons to be generally compliant with drug control and detection policies and procedures.

2.4.2 Drug prevention controls

Victoria's 11 public prisons, two private prisons and one transition centre each have a variety of generally effective drug prevention controls. Typically, these controls include visitor bookings and assessments, searches, detectors and scanners, detection dogs and monitoring.

Visitors

With a total of 99 291 visits across the public prison system in 2012, CV considers its prisons to be vulnerable to the introduction of drugs when prisoners are receiving visitors.

The different types of visits available present varying opportunities and vulnerabilities for visitors to attempt to smuggle drugs to prisoners. Box visits—where visitors and prisoners are kept in separate but adjacent rooms separated by a glass window—are the least vulnerable, while residential visits—where partners are permitted to stay privately with prisoners in residential settings—present the greatest opportunity because prisoners and visitors are allowed to spend time together unsupervised.

Consistent with CV requirements, Dhurringile Prison, DPFC and Marngoneet each have effective visitor management processes. At each of these prisons, visitors must register with CV in advance of their first visit, and they are assessed to identify security and drug risks. Where a visitor has been identified as a risk of introducing drugs into the prison, options available to the general manager include:

- not allowing the visit

- allowing the visit to occur but as a non-contact visit in a separated area

- allow the visit to occur but under close supervision.

Following each visit, prisoners at the three locations are strip searched before going back into the main grounds of each prison.

In addition, these prisons require visitors to empty their pockets in front of prison staff and to either lock bags away or have them searched before proceeding to visitor areas. This process is more difficult at DPFC than Marngoneet, which was built more recently and has a large reception area for visitors to be processed through. DPFC's gatehouse—used to conduct visitor inspections—is outdated and no longer fit for purpose, given that it was originally designed to service a prison of 125 prisoners and now services a prison with an operating capacity of 344. This creates additional risks in terms of introducing contraband into this prison. CV is aware of this issue and has developed a master plan to upgrade the facilities at DPFC, but to date only minor modifications have been made.

Ion scanners

Three maximum security prisons—Barwon Prison, Melbourne Assessment Prison and the Metropolitan Remand Centre—have a walk-through ion scanner and require all visitors and an allocation of staff and contractors to walk through it before entering the prison.

Ion scanners are designed to detect explosive and drug particles, but are not in themselves evidence that a person is carrying drugs. CV has clear procedures when an ion scanner detects drug particles. Actions include voluntary strip searches and refusal of the visit.

Both Marngoneet and DPFC have portable, rather than walk-through, ion scanners that can be used to scan visitors. Weaknesses in the way both prisons use their portable ion scanners were identified during the course of this audit, which CV is addressing.

Security and Emergency Services Group

CV's Security and Emergency Services Group (SESG) is responsible for security operations across the prison system and responds to critical incidents that occur in prisons. SESG coordinates and conducts searches within prisons, prisoner visits and—in coordination with Victoria Police—random and targeted searches of prison car parks.

SESG uses passive alert detection dogs and general purpose dogs on searches to identify contraband, including drugs. SESG has 15 passive alert detection dogs: 12 drug detection dogs, one to detect mobile phones and two specifically trained to detect buprenorphine.

Figure 2A shows the number of searches required and undertaken by SESG at each prison in 2011–12, excluding statistics for November and December 2011. These were not recorded due to industrial action.

Figure 2A

Required and actual numbers of prison searches by the Security and Emergency Services Group, 2011–12

|

Prison |

Number of required searches |

Number of actual searches conducted |

Difference between searches conducted (per cent) |

Requirement satisfied |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Maximum security |

||||

|

Barwon Prison |

96 |

371 |

286 |

Yes |

|

Dame Phyllis Frost Centre |

96 |

91 |

–5 |

No |

|

Melbourne Assessment Prison |

120 |

150 |

25 |

Yes |

|

Metropolitan Remand Centre |

96 |

435 |

353 |

Yes |

|

Port Philip Prison |

0 |

32 |

NA |

Yes |

|

Medium security |

||||

|

Fulham Correctional Centre |

0 |

2 |

NA |

Yes |

|

Hopkins Correctional Centre |

36 |

38 |

6 |

Yes |

|

Loddon Prison |

36 |

95 |

164 |

Yes |

|

Marngoneet Correctional Centre |

36 |

50 |

39 |

Yes |

|

Minimum security |

||||

|

Beechworth Correctional Centre |

18 |

18 |

0 |

Yes |

|

Dhurringile Prison |

18 |

35 |

94 |

Yes |

|

Langi Kal Kal Prison |

18 |

23 |

28 |

Yes |

|

Tarrengower Prison |

18 |

30 |

67 |

Yes |

Note: SESG conducts searches at the request of the Judy Lazarus Transition Centre and an additional number of random searches. This data is not recorded by CV.

Source:Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Justice.

The greater level of SESG‑required searches is appropriate at maximum security prisons given that these prisons hold the prisoners that CV considers to be of greatest risk. SESG exceeded its required number of searches for all locations excluding DPFC. However, SESG conducted more searches at the medium security Loddon Prison than DPFC and a higher ratio of searches than required at Loddon than at Melbourne Assessment Prison and DPFC. This is inconsistent with the security classification of the three prisons, which indicate that DPFC and Melbourne Assessment Prison are at higher risk of drug use and should be subject to a greater amount of searches than Loddon.

During the conduct of this audit, CV has begun to implement an intelligence and risk‑based approach to allocating SESG searches to public prisons.

Prisoner searches

Prisoners bringing drugs into the prison system remains a problem for CV, particularly if prisoners are storing drugs inside their bodies. To prevent drugs being introduced in this way, all prisons have procedures to strip search prisoners upon reception, after temporarily leaving the prison and after prisoner visits. DPFC, Dhurringile and Marngoneet all have dedicated areas within their reception facilities and visitor centres to strip search prisoners. As a minimum security prison, some of Dhurringile's prisoners work in the community. Unescorted prisoners are strip searched once they return to the prison.

2.4.3 Drug detection controls

Drug prevention controls are not able to prevent all contraband from entering the prison system. Recognising this, CV and prisons also have controls in place to detect drugs and drug use within the prison. Detecting drug use in prisons serves two purposes—it enables prison staff to seize the drugs to prevent further use, and identifies drug users so that they can be appropriately managed and treated.

The search procedures and the large volume of drug tests conducted by CV provides reasonable assurance that prisons are identifying prisoners who are using drugs. CV relies on two main controls to detect drug use and the presence of drugs in prisons—searches by prison staff and SESG, and its urinalysis testing programs. Given the prevalence of prisoners illicitly using buprenorphine, prisons also have processes to prevent prisoners from diverting prescription medications, in order to limit trafficking and misuse.

Searches and inspections

Searches and inspections within prisons are not only an important deterrent and drug detection mechanism for preventing and detecting drug use within prisons, but also help maintain the good order of prisons by identifying other contraband items.

Prison staff at the three prisons visited conduct regular random cell searches as part of their day-to-day operations. Cell search procedures at all three prisons were observed by VAGO and complied with CV requirements. All three prisons maintain search and seizure logs that document the cells and prison areas searched and any contraband that is found.

Urinalysis drug testing

CV considers urinalysis drug testing to be an essential component of its detection and deterrence goal within its Victorian Prisoner Drug Strategy 2002 and has been used in prisons since 1992. The purpose of CV's urinalysis testing includes:

- deterring prisoners from drug use

- identifying drug users for sanctions and referral to treatment

- determining the extent and type of drug use at each prison and across the prison system.

CV's key urinalysis programs aimed at preventing and detecting drug use are random general testing and targeted testing of prisoners who are suspected of engaging in drug-related activity. CV also has urinalysis programs to test known drug users participating in drug-related programs, and on reception into prisons.

Random general urinalysis

Random general urinalysis testing is used by CV to determine the extent and type of drug use at each prison and across the prison system. Each week, 3 per cent of prisoners in public prisons and 1.25 per cent of prisoners in private prisons are randomly selected and required to submit to a urine test. CV has put in place procedures to ensure that prisoners tested are randomly selected and that prisons comply with the program's requirements. Of the 25 664 urinalysis tests conducted in 2012–13, 6 618 or 25.8 per cent were random general tests.

Target testing

Prisons target-test specific prisoners based on intelligence, suspicion of drug use, or past offending history. Unlike random general urinalysis testing, the numbers of target tests each prison conducts is not linked to the prison population but is up to the discretion of prison general managers. Of the 25 664 total urinalysis tests conducted in 2012–13, 9 278 tests or 36.2 per cent were targeted tests.

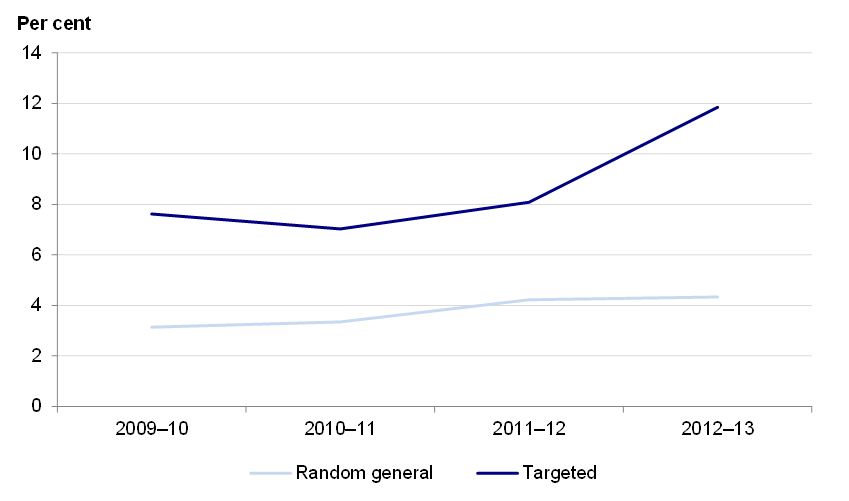

Figure 2B shows the percentage of positive random general urinalysis compared with the percentage of positive targeted tests for the prison system from 2009–10 to 2012–13.

Figure 2B

Percentage of positive random general and targeted urinalysis drug tests across the prison system,

2009–10 to 2012–13

Note: Urinalysis drug test results for 2012–13 are provisional.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Justice.

Targeted urinalysis tests across the prison system have consistently produced higher results than random general testing. The target testing results for 2012–13 of 11.85 per cent are at least 3 per cent higher than any of the previous three years, indicating that prisons are more effective at identifying prisoners who are using drugs and target-testing these prisoners to confirm suspicions of drug use.

The increase in positive target tests over the past four years can be attributed to improvements at maximum and medium security prisons, with each prison recording a higher percentage of positive tests in 2012–13 than in previous years. Higher security prisons also generally had higher rates of positive targeted tests than lower security prisons. This is consistent with CV's expectations and minimum standards that prisoners at greater risk of using drugs are held in higher security prisons.

There were, on average, substantially fewer target tests undertaken each month at maximum and medium security prisons over the past two years than in 2009–10 and 2010–11. The decrease in target testing coincides with the increase in illicit drug use across the prison system during this time.

Target testing urinalysis results for each prison are contained in Appendix A, Figure A2.

Diversion prevention strategies

Diversion of prescribed opioid substitution treatment medication by prisoners for the purpose of trafficking it to other prisoners remains a risk within prisons. Methadone, buprenorphine and suboxone are the types of medications available to prisoners through the Opioid Substitution Therapy Program.

Illicit use of methadone accounted for only 2.2 per cent of the total positive urinalysis tests conducted in 2012–13, compared with 57.7 per cent for buprenorphine. As methadone is far more widely prescribed to prisoners enrolled in the Opioid Substitution Therapy Program than buprenorphine, it is likely that the majority of buprenorphine is being introduced into the prison system rather than prisoners diverting prescribed medication.

CV and Justice Health have effective safeguards to minimise the risk of diversion. These include requirements to search prisoners pre- and post-dosage, observation of prisoners for at least 10 minutes after dosage, and disposal and observation in secure areas. The three prisons visited complied with these processes.

Given the high rates of illicit buprenorphine use by prisoners, CV and Justice Health have appropriately kept the prescription of buprenorphine to a minimum, with no more than six prisoners having been prescribed it at any one time. Instead, approximately 90 per cent of all prisoners enrolled in the Opioid Substitution Therapy Program are prescribed methadone and approximately 9 per cent are prescribed suboxone.

To further minimise the diversion of buprenorphine and suboxone, CV and Justice Health introduced buprenorphine-suboxone film in 2012 to replace tablets. The film dissolves faster under the tongue than tablets, making diversion more difficult.

2.4.4 Managing detected drugs

CV has appropriate procedures in the event that drugs are discovered outside or within a prison. Prison officers are given instruction on weighing, securing, and recording the substances in a seizure register. Prison officers are also instructed on how to preserve and document a crime scene and instructed on what is required for the continuity of evidence, including storage in the prison evidence safe.

DPFC, Dhurringile and Marngoneet all have compliance procedures associated with the seizure and storage of drugs including weekly audits of prison evidence safes.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice:

- establish robust performance reporting frameworks to assess the effectiveness of its barrier control and drug detection initiatives

- develop and document risk management practices across all its public prisons to identify and manage prison-specific strategic risks

- develop and document a framework to guide it in determining the balance between drug prevention and detection controls, and prisoner management needs

- review and update the random general urinalysis benchmarks in light of prison‑specific risks and the 'balancing' framework.

3 Identifying and treating drug users

At a glance

Background

The high proportion of prisoners who have used drugs before entering the prison system presents both challenges and opportunities. Unaddressed drug use can contribute to demand for drugs in prison as well as exacerbating the physical and mental health problems associated with drug use. Conversely, promptly identifying drug users provides opportunities to address drug use and health-related problems while under sentence.

Conclusion

Corrections Victoria and Justice Health's processes and programs provide confidence that prisoners with drug problems are being identified and prisoners are given opportunities to address their drug using behaviours. However, neither entity can determine the effectiveness of its management and treatment programs because they do not have good performance reporting frameworks, nor do they often evaluate the programs.

Findings

- Both entities have good processes to identify prisoners with drug problems upon reception and in prisons.

- Corrections Victoria has programs to manage identified drug users and to provide incentives and punishments to reduce incidents of drug taking.

- Justice Health has a range of evidence-based treatment programs for prisoners to address their alcohol and other drug-related problems.

Recommendations

That the Department of Justice:

- establish robust performance reporting frameworks to assess the effectiveness of its drug treatment and management programs

- evaluate the effectiveness of its programs for managing and treating prisoners with drug problems.

3.1 Introduction

The high proportion of prisoners who have used drugs before entering the prison system presents both challenges and opportunities. Unaddressed drug use can contribute to demand for drugs in prison, as well as contributing to associated physical and mental health issues. Conversely, identifying drug users as early as possible provides opportunities to address drug use and health-related problems during the prisoner's incarceration.

3.2 Conclusion

Corrections Victoria (CV) and Justice Health (JH) are identifying prisoners with drug problems upon reception or in prisons. They operate programs to monitor the behaviour of—and provide incentives and punishments to—those detected using drugs in prisons. They also provide treatment programs to address the behaviours that lead to drug taking. The alcohol and other drug (AOD) programs are evidenced-based and consistent with current practice. However, more could be done to prevent the high rates of hepatitis C infections among prisoners.

An ongoing challenge for both CV and JH is assessing the overall effectiveness of these initiatives.

3.3 Identifying prisoners with drug problems

CV and JH use prisoners' health and offending risk factors to identify those with drug problems upon reception and during their sentence. As discussed in Part 2, they also use drug detection methods such as searches and inspections and urinalysis testing to identify prisoners with drug problems while in prison. Combined, these strategies provide an adequate system to identify prisoners with drug problems.

3.3.1 Health assessments

When prisoners first enter the prison system, male prisoners are received at the Melbourne Assessment Prison (MAP) and female prisoners are received at the Dame Phyllis Frost Centre (DPFC). At both prisons, prisoners receive a health assessment from the contracted health services provider. JH requires assessments to be conducted within 24 hours of a prisoner's arrival and when transferring between prisons, with a key purpose being to identify any drug-related health problems for treatment. The reception assessment also seeks to identify whether a prisoner was undertaking any treatment within the community, such as opioid substitution therapy.

Figure 3A shows the total number of health assessments conducted within 24 hours of reception at public prisons, the number of assessments that were not conducted within 24 hours and the compliance percentage from January 2009 to May 2013.

Figure 3A

Health assessments within 24 hours for public prisons, 2009 to May 2013

| Year |

Assessments within 24 hours |

Missed assessments |

Compliance (per cent) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

January to June 2009 |

5 585 |

5 |

99.91 |

|

2009–10 |

12 055 |

4 |

99.97 |

|

2010–11 |

12 198 |

6 |

99.95 |

|

2011–12 |

12 805 |

12 |

99.91 |

|

July 2012 to May 2013 |

13 663 |

18 |

99.87 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Justice.

The Department of Justice has set a benchmark of 100 per cent compliance for health assessments within 24 hours of reception at a prison. Although public prisons have not achieved 100 per cent compliance in any one financial year from 2008–09 to 2012–13, the vast majority of assessments are conducted within the required time. As the main reception prison for male prisoners, MAP conducts more health assessments than any other prison—6 185 assessments in 2012–13 to May 2013.

3.3.2 Risk factor assessments

After reception, prisoners' risk of re-offending and their rehabilitation needs, including AOD treatment, are also assessed. This information is used to identify the types of programs prisoners should complete during their sentence to address the behaviours that relate to their offending.

The assessment is to be completed within six weeks of sentencing. CV has generally met these time lines, with 75 per cent of the 2 877 assessments completed within six weeks and 61 per cent within four weeks in 2012. Delays may occur due to outstanding court matters or the need to await further prisoner information, but prisoners can still be referred to the AOD service provider through other means such as the health assessment and AOD orientation. Prisoners may also self-refer at any time.

In addition, prisoners' AOD problems may be identified during the AOD orientation program, which is compulsory for all prisoners and consists of a half‑hour group session with a psychologist from the AOD service provider. Prisoners are required to attend the session within two weeks of their reception.

3.4 Evidence-based services, programs and treatments

CV and JH have a broad range of evidenced-based programs to manage and treat prisoners' AOD problems. However, due to the shortcomings of performance measurement and program evaluation, neither CV nor JH are able to demonstrate that these programs have been effective in reducing incidence of drug use or drug-related harms.

JH's recent work on expanding hepatitis C treatment demonstrates awareness of current developments in hepatitis C treatment and that it is seeking to change its treatment regime as new evidence and treatments emerge. Despite the high rates of communicable diseases in prisons and the strong evidentiary basis for needle and syringe programs, JH and CV have not supported a needle and syringe program trial in a Victorian prison setting.

3.4.1 Identified Drug User program and Drug Free Incentive Program

Drug use by a prisoner during their sentence is identified through physical searches and urinalysis testing. Any prisoner identified through searches or testing is required to attend an Identified Drug User (IDU) review with a clinician from the AOD service provider within five days. The purpose of this review is to discuss the prisoner's drug problems, treatment needs and participation in AOD programs. This is occurring in a timely manner at DPFC and Marngoneet. As prisoners with an active IDU status do not remain at Dhurringile Prison, as it is a minimum security facility, these assessments occur at whichever prison the prisoner gets transferred to.

As well as being seen by a clinician, prisoners identified as active drug users are given an IDU status. IDU-status prisoners lose their contact visitation rights for a period of time, and are subject to more urinalysis testing than the general prison population. Prisoners may also face other consequences if given an IDU status, including loss of employment or changes in their security classification.

The IDU program is a graduated system, with the length of the sanction dependent on the results of future urinalysis tests. Prisoners are able to reduce the length of the sanction by undertaking an associated program called the Drug Free Incentive Program (DFIP). In DFIP, prisoners voluntarily submit to a specified number of urinalysis tests over a set time frame, with the resumption of access to contact visits depending on test results. Other Australian jurisdictions use similar incentive-based programs to manage prisoners who have been identified as drug users.

Figure 3B shows the percentage of IDUs at prison facilities from 2009 to 2013.

Figure 3B

Identified Drug Users at prison facilities, 30 June 2009 to 30 June 2013

|

Prison |

2009 (per cent) |

2010 (per cent) |

2011 (per cent) |

2012 (per cent) |

2013 (per cent) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Maximum security |

|||||

|

Barwon Prison |

14.0 |

18.0 |

15.3 |

25.1 |

19.5 |

|

Dame Phyllis Frost Centre |

7.0 |

7.3 |

6.4 |

9.4 |

9.8 |

|

Melbourne Assessment Prison |

1.4 |

5.1 |

3.9 |

0.4 |

5.0 |

|

Metropolitan Remand Centre |

4.6 |

6.3 |

6.2 |

7.1 |

7.3 |

|

Port Philip Prison |

11.5 |

12.9 |

12.8 |

14.7 |

15.5 |

|

Medium security |

|||||

|

Fulham Correctional Centre |

5.9 |

10.3 |

10.1 |

10.3 |

10.6 |

|

Hopkins Correctional Centre |

0.5 |

2.2 |

0.8 |

1.6 |

2.3 |

|

Loddon Prison |

1.0 |

1.5 |

0.0 |

1.2 |

0.3 |

|

Marngoneet Correctional Centre |

4.9 |

6.9 |

4.0 |

6.0 |

6.5 |

|

Minimum security |

|||||

|

Beechworth Correctional Centre |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Dhurringile Prison |

0.0 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

|

Langi Kal Kal Prison |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Tarrengower Prison |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Judy Lazarus Transition Centre |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

|

Total prison population |

5.7 |

8.3 |

7.3 |

8.9 |

9.1 |

Note: Figures are a point-in-time as at 30 June of each year.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on data from the Department of Justice.

The total percentage of prisoners with an IDU status has increased from 5.7 per cent on 30 June 2009 to 9.1 per cent on 30 June 2013. This is consistent with the increasing trends of targeted and random general urinalysis drug testing.

Barwon Prison has had the highest percentage of prisoners with an IDU status in each of the past five years. This is despite having a lower rate of positive targeted and random general urinalysis results than the other prisons with high rates of IDU‑status prisoners—Port Philip Prison, Fulham Correctional Centre and DPFC. Barwon Prison manages the majority of Victoria's highest security prisoners. Prisoners may be transferred to Barwon Prison to manage continued problematic behaviour, including related drug incidents, at other maximum security and medium security prisons. As a consequence, many of Barwon Prison's IDUs are likely to have been given their IDU status at other prisons.

However, CV cannot demonstrate whether either the IDU program or DFIP are effective at reducing drug use among participants. CV does not analyse and report on the trends or outcomes of either program, nor has either program been evaluated. CV tests 5 per cent of all prisoners with an IDU status each week and target tests prisoners enrolled in the DFIP as part of its urinalysis program. However, it does not collate or analyse the results on a prison-by-prison or system-wide basis as it does for its random general and target testing urinalysis programs. Collating and analysing these results would provide a measure of the effectiveness of the IDU program and DFIP.

3.4.2 Alcohol and other drug treatment programs

The AOD service provider provides two program streams for offenders with AOD problems—a criminogenic stream, that targets offending, and a health stream, that targets harmful AOD use.

While the evidence base underlying the structure and content of AOD treatment programs has not been comprehensively evaluated since 2003, both JH and AOD service providers routinely review the evidence base and undertake ongoing activities aimed at ensuring the programs remain current.

From July 2012 to December 2012, 623 of 716 prisoners who began AOD programs had completed them, a completion rate of 87 per cent. The increasing number of prisoners held in Victoria's prisons has increased the demand for some AOD programs and JH has acted to modify the contract with the AOD service provider to meet the growing demand throughout 2013.

As with the IDU program and DFIP, evaluation of the effectiveness of AOD treatment programs remains problematic. The AOD service provider submits an annual evaluation report to JH based on psychometric testing, which measures changes in participants through a before and after program comparison. However, this information is not reported by JH to the Department of Justice as a performance measure to determine the effectiveness of AOD programs.

Further, psychometric analysis cannot measure long-term effectiveness or whether any improvements will be maintained once a prisoner returns to the community, as there has been little formal follow-up of prisoners once they are released from prison. While evaluations of this type are complex, their absence means that there is a lack of information regarding the longer-term effectiveness of programs offered in prisons. Post-release data would need careful analysis before drawing conclusions regarding efficacy due to the broad range of factors that affect the actions of ex-prisoners, however, such data would be beneficial.

JH have included an evaluation of AOD treatment programs as part of its draft Research Agenda 2013–14.

3.4.3 Opioid Substitution Therapy Program

The Opioid Substitution Therapy Program (OSTP) commenced in Victoria's prisons in 2003. OSTP allows prisoners to commence or continue treating their opiate addiction through the use of medication. Prior to this, methadone had been available since the 1980s for prisoners who were on a community program and were serving sentences of less than six months. The development of OSTP was based on research, stakeholder consultation and recognised community standards for treating opiate addiction.

In 2012, JH reviewed OSTP in preparation for a review of the Victorian Prison Drug Strategy 2002. The review provided JH with assurance that the evidence base supporting OSTP was current and consistent with better practice. However, the review found that OSTP is facing systemic pressures, with demand outstripping capacity. While JH is meeting demand, the amount of OSTP daily doses distributed to prisoners is approaching the physical limits of public prisons, with some prisons exceeding the daily number of doses that the physical infrastructure can support. As part of its review, JH identified the potential to reduce the supervision times of methadone—given low rates of diversion—from 20 minutes to 10 minutes, which is more consistent with other Australian jurisdictions. This change was implemented in May 2013 and should help alleviate some of the OSTP capacity constraints facing public prisons.

OSTP has not been evaluated since 2007 and JH does not measure and report on program outcomes. JH should evaluate the effectiveness of OSTP.

3.4.4 Hepatitis C treatment

Communicable diseases are a particularly serious issue in prisons, with hepatitis C being one of the most common and dangerous bloodborne viruses found in prisons.

JH implemented the Justice Health Communicable Disease Framework 2012–2014 in 2012 to provide a procedural framework for the treatment of bloodborne viruses and sexually transmissible infections in prisons. The framework was developed through research and expert stakeholder consultation to provide assurance that the framework is current.

All prisoners are offered testing for bloodborne viruses upon reception into the prison. This forms part of the health assessment conducted within 24 hours of reception.

Currently there are minimal places available for hepatitis C treatment—30 places each year between Marngoneet, Barwon Prison and DPFC. However, uptake by prisoners has traditionally been low—just over half of available places at DPFC are typically used. The rate of uptake can depend on a variety of factors, including prisoners' willingness and eligibility. Despite the health implications of hepatitis C, prisoners, as with the general population, can be unwilling to undertake treatment due to the severity of side effects. Those prisoners who want treatment may not be eligible to apply due to a short sentence or mental and physical health problems.

JH is currently developing a statewide hepatitis treatment program with the aim of:

- increasing access to treatment

- improvingthe outcomes for prisoners with hepatitis B and C.