Public Safety on Victoria's Train System

Overview

Public transport services, and in particular trains, play a significant role in the community. Passengers should feel safe as they use these services regardless of the time of day or night. The protective services officers (PSO) program was established to reduce crime and improve perceptions of safety on Melbourne’s train system.

Perceptions of the safety of the metropolitan train system at night have improved since the start of the PSO program, but the extent to which this can be attributed to the presence of PSOs is unknown. It is also not possible to assess whether PSOs have had any impact on crime on the metropolitan train system.

Advice provided to government to support decisions on the establishment and deployment of the PSO program was comprehensive, however, performance monitoring has been limited. Victoria Police does not have an effective performance monitoring regime in place to support ongoing development or future advice on the program's efficiency or effectiveness.

Additionally, there is an opportunity to drive greater awareness of the presence of PSOs, further improving perceptions of safety and increasing patronage.

Public Safety on Victoria's Train System: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2015

PP No 129, Session 2014-16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Public Safety on Victoria's Train System.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

24 February 2015

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Dallas Mischkulnig—Engagement Leader Helen Lilley—Team Leader Rosy Andaloro—Team member Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Andrew Evans |

All Victorians should be able to expect to not only feel safe, but also be safe when using our public transport system. However, this is unfortunately not always the case, particularly at night.

In 2011, the former government established a program to deploy two Victoria Police protective services officers (PSO) to every metropolitan and selected regional train stations from 6 pm until after the last train. The PSO program was intended to reduce crime and improve public perceptions of the safety of the train system.

I found that while there is evidence that PSOs have increased perceptions of the safety of Melbourne's train network at night, it is not possible, on the available data, to determine if their presence has had an impact on crime.

Successive governments have sought to improve the personal safety of Victorian commuters by adding more and more police to the train network. The original commitment was for 940 PSOs. By late 2016, there will be 1 145 PSOs operating at train stations. This is despite there being no measures in place to determine whether the PSOs are having the effect the policy intended. So, while 1 145 PSOs may make people feel safer, it is not clear whether safety has actually improved.

Improving perceptions of the safety of the train system is an important objective, as multiple surveys report that less than half of Victorians feel safe catching our trains at night, even after the addition of PSOs. If people feel that their trains are safe, then they are more likely to use them. This is particularly relevant with the commencement of the Night Network.

This audit found that the state is not fully capitalising on the presence of PSOs and other safety and security personnel to improve patronage on the train network. Awareness of the presence of PSOs has contributed to increased feelings of safety and patronage, particularly among regular night-time train users, but it remains low among other commuters. If the state is to increase night-time patronage, then people who are not regular night-time train users need to be made aware of PSOs and the role that they play. However, there has been no campaign to increase public awareness.

The focus of the agencies throughout the establishment of the PSO program was to meet government's recruitment and deployment milestones. Little attention was paid to establishing a performance reporting regime, or giving considerations to how the PSO program would best operate in the long term.

Agencies now need to turn their focus to how PSOs can be used most effectively and efficiently, and to ensure they are in a position to be able to provide government with comprehensive, evidence-based advice on the future of the PSO program.

While my report focuses on the PSO program, I believe that it is important to recognise that PSOs are just one of many personnel aiming to ensure the safety and security of train commuters. Several government agencies, as well as several commercial entities, share commuter safety and security responsibilities. Despite this, strategic‑level coordination at the executive level is lacking.

I am pleased that Victoria Police, the Department of Justice & Regulation and Public Transport Victoria have accepted my recommendations, and will take action to address the underlying issues raised in this audit.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

February 2015

Audit Summary

Public transport services and, in particular, trains play a significant role in connecting people to a range of social and economic opportunities, such as employment, education and services. Passengers should feel safe as they use these services regardless of the time of day or night.

Public perceptions of safety on the train system can impede patronage. Several studies have found that perceptions of safety have a greater influence on community behaviour than the actual crime rate. Public perceptions may be influenced by personal opinions, media reporting of incidents, poorly lit areas and vandalism and graffiti. In 2014, approximately half of all criminal offences recorded on the train system occurred after 6 pm.

In 2011, the former government committed $212 million over four years to recruit 940 protective services officers (PSO) for deployment at 212 metropolitan rail stations and four regional stations, every night from 6 pm until after the last train. This was intended to:

- deter crime, violence and antisocial behaviour on the train system

- improve perceptions of safety for commuters on the train system

- enhance opportunities for local crime prevention and intelligence gathering to assist broader policing initiatives and ensure public safety and confidence within railway precincts.

Victoria Police is the primary agency responsible for the practical implementation, monitoring and reporting on the progress and effectiveness of the initiative. Public Transport Victoria (PTV) is responsible for making sure the necessary train station infrastructure is in place to support PSOs' functions.

The objective of this audit was to determine the effectiveness of PSOs deployed across Victoria's train system by assessing if:

- PSOs have reduced crime on the metropolitan train system and improved public perceptions of safety of train travel, particularly at night

- appropriate advice supports key decisions on the deployment of PSOs

- governance arrangements for personal security and safety initiatives across the train system support and leverage the work of PSOs.

Conclusions

Community perceptions of the safety of the metropolitan train system at night have improved since the start of the PSO program, but the extent to which this can be attributed to the presence of PSOs is unknown. It is also not possible to assess whether PSOs have had any impact on crime rates on the metropolitan train system.

The full value of the PSO program is yet to be realised. Greater awareness of the presence of PSOs has the potential to improve perceptions of safety and increase patronage. There is also the potential for PSOs to be used more efficiently and effectively.

However, until Victoria Police improves its approach to monitoring the performance of the PSO program, it will not have the evidence necessary to inform future government decisions about their deployment and utilisation.

In addition, a formal framework is needed to support strategic cross-agency coordination and to maximise the community benefit of the current suite of personal safety and security initiatives in place across the public transport system.

Findings

Perceptions of safety

Community perceptions of personal safety on the metropolitan train system have increased since PSOs were first deployed in February 2012. However, it is not possible to fully isolate the effect of PSOs on public perceptions of safety from the impact of other factors, including increases in the number and patrol frequency of authorised officers (AOs) and transit police, station improvements and increases in train service frequency. Additionally, the presence of PSOs alone may not be enough to improve perceptions of safety, particularly at large, multi-platform stations where PSOs may not be visible at all times.

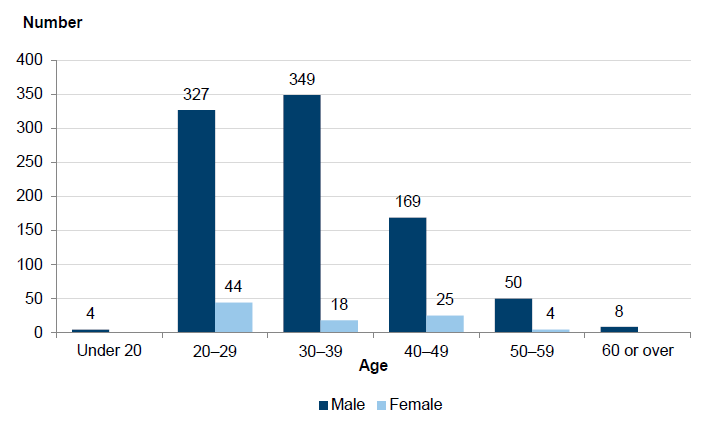

There has only been one study in which a change to perceptions of safety can be directly attributed to PSOs—the PSO Evaluation Study, commissioned by PTV and the Department of Justice & Regulation, specifically measured the effect of PSOs on commuters' perception of safety. This was a one-time study consisting of a survey of commuters at selected train stations in 2012—prior to PSO deployment—and then again a year later, once PSOs had been deployed to these stations. The study found perceptions of safety at night at these selected stations increased by approximately 8 per cent during that first year. However, the absence of a performance target means it is not possible to assess if this is a satisfactory increase.

Two further sets of data have been used to measure changes in train commuters' perception of safety. However, each has limitations that reduce its usefulness:

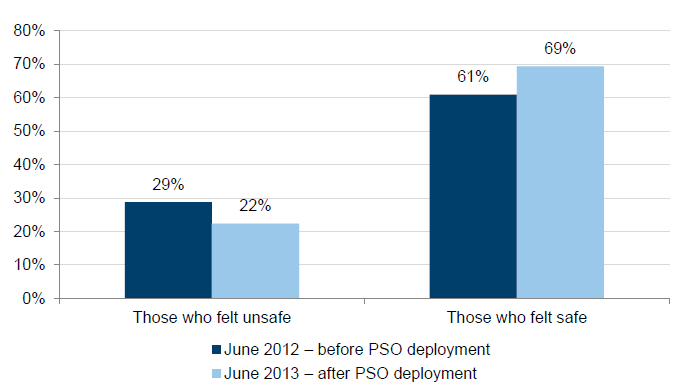

- PTV's Customer Satisfaction Monitor measures train customers' satisfaction with a number of network factors, including personal security at train stations at night. This has shown that satisfaction has increased approximately 10 per cent since the start of the PSO program. However, the Customer Satisfaction Monitor measures customer perception rather than the impact of specific initiatives. It therefore does not contain the information needed to determine the extent to which the rise in perception of safety can be attributed to the presence of PSOs.

- The National Survey of Community Satisfaction with Policing (NSCSP) measures the percentage of the population who feel safe on public transport at night. NSCSP data has also recorded a 10 per cent increase in the number of Victorians who feel safe using public transport at night. However, NSCSP data is not specific to trains, as it encompasses all modes of public transport.

Despite the fact that increasing commuters' perception of the safety of the metropolitan train system at night is a policy objective for the PSO program, government did not set any targets and, other than NSCSP reporting, there has been no attempt to routinely assess whether this objective has been achieved.

Impact on crime

Another policy objective of the PSO program is to reduce crime and antisocial behaviour on the train network at night. However, there has not been any formal evaluation of whether the PSO program has had this intended impact.

Victoria Police's systems and processes for recording crime at train stations do not require police members to record the name of the station where the crime was committed. Consequently, 13 per cent of the offences recorded at train stations since 2010 were not attributable to a particular station. This means it is not possible to accurately assess the impact of PSOs, as it is not possible to compare the crime rates at a particular station before and after PSO deployment.

Increasing police numbers typically leads to an increase in recorded crime. This is because more police members are available to detect more crime. The incidence of reported crime also increases due to the increased accessibility of police. Our analysis of the first 11 stations to have PSOs deployed shows a sharp increase in the number of offences coinciding with the rollout of PSOs during their first year of operation. This is followed by a gradual reduction in reported offences, as criminal behaviour is either displaced or deterred.

Public awareness

The lack of a PSO public awareness strategy means that agencies are not capitalising on the presence of PSOs to improve perceptions of safety and increase patronage on trains after 6 pm.

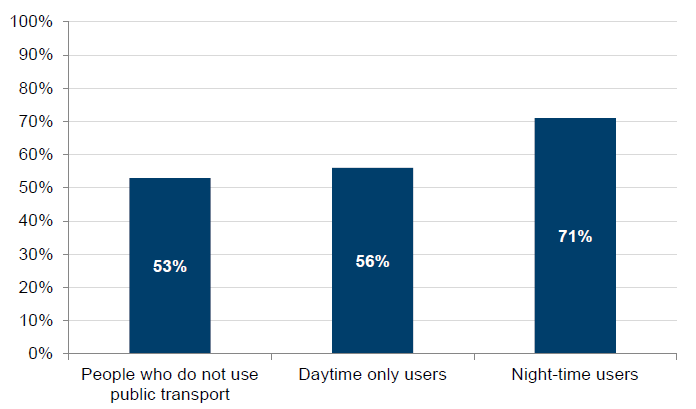

Lack of awareness of the presence and role of PSOs impacts on perceptions of safety. Knowing PSOs are present and observing them patrolling platforms increases commuters' perceptions of safety. Just over half of Melbourne residents who do not use public transport or who only use public transport during the day were aware of PSO patrols. By comparison, 71 per cent of regular night-time train users were aware that PSOs patrol most metropolitan train stations, indicating that community knowledge of PSOs is mostly due to direct interaction.

A key priority for PTV is to improve perceptions of safety on the network as this is one of the most effective ways to increase patronage. During 2015, PTV scoped an information campaign to increase public awareness of PSOs and their duties, however, plans for this campaign were abandoned in late 2015.

Advice to government

Advice provided to government to support decisions on the establishment and rollout of the PSO program was comprehensive. The report back to government following the first 18 months of the program was focused on the government's priorities at the time, but it also advocated for changes to the PSO program in order to improve efficiency and effectiveness and to reduce costs. While government chose not to follow this advice, the options presented were comprehensive and soundly based.

Performance monitoring

Performance monitoring for the PSO program has been limited to providing government with feedback on its specific areas of interest:

- progress against recruitment and deployment targets

- cost pressures

- PSO impact on the perceived safety of the train system.

Victoria Police does not have an effective performance monitoring regime in place to support ongoing development or future advice on the program's efficiency or effectiveness.

Key performance indicators established in 2013 were not underpinned by sufficient reliable data to enable the assessment of PSO performance and were selected primarily to minimise the cost and administrative burden of reporting. This data has proven insufficient to enable reporting, negating the efficiency Victoria Police was aiming to achieve.

Furthermore, Victoria Police did not pursue performance reporting of the efficiency or effectiveness of the PSO program beyond late 2013, due to a lack of staff resources. There has been no monitoring of the efficiency or effectiveness of the PSO program since then.

PSO operations and training

Victoria Police's focus since the start of the PSO program has been on PSO training and operations to ensure its personnel have the knowledge, support and resources needed to carry out their duties. It has sufficient processes in place to ensure that PSOs' training and operations are continuously improved.

Operational policies and processes for PSOs are documented, readily accessible to all PSOs and regularly reviewed. Adherence to operational processes is continuously monitored by PSO supervisors from Victoria Police's Transit Safety Division. The PSO training regime has been consistently reviewed and modified since the start of the initiative.

Cross-agency coordination

Cross-agency coordination on personal safety and security is generally effective at both the operational and agency levels, but insufficient at the strategic level.

Current strategic coordination between agencies on personal safety and security initiatives is lacking. There is no overarching strategy to guide agencies' decision‑making. The absence of an executive-level committee is an impediment to establishing strategic cross‑agency initiatives to improve personal safety and security on the train network.

Improved governance arrangements are required at all levels to ensure that coordination is maximised and that the available knowledge, resources and capabilities are efficiently and effectively used.

Operational information sharing between Victoria Police and the train operator is effective. There is direct and regular contact between the train operator's safety and security personnel and Victoria Police to share information on incidents that have occurred on the train network.

Night Network

The Night Network initiative is a 12-month trial of 24-hour public transport on Fridays and Saturdays throughout 2016, covering metropolitan trains, along with selected tram and bus routes. Commuter safety and security is a key aspect of the Night Network initiative and will therefore involve PSOs.

Plans for the Night Network trial mean there will be a change in the usual deployment of PSOs. On Friday and Saturday nights, PSOs will be deployed to the 78 premium stations that will be operating during the Night Network, with the capacity to provide PSOs to either four additional stations or to provide extra personnel to support major stations. An evaluation of the Night Network trial is scheduled to occur during June 2016, to determine whether to extend the Night Network in 2017.

Agencies are likely to find it difficult to fully evaluate the effectiveness of the trial unless relevant key performance indicators, backed by reliable data, are put in place.

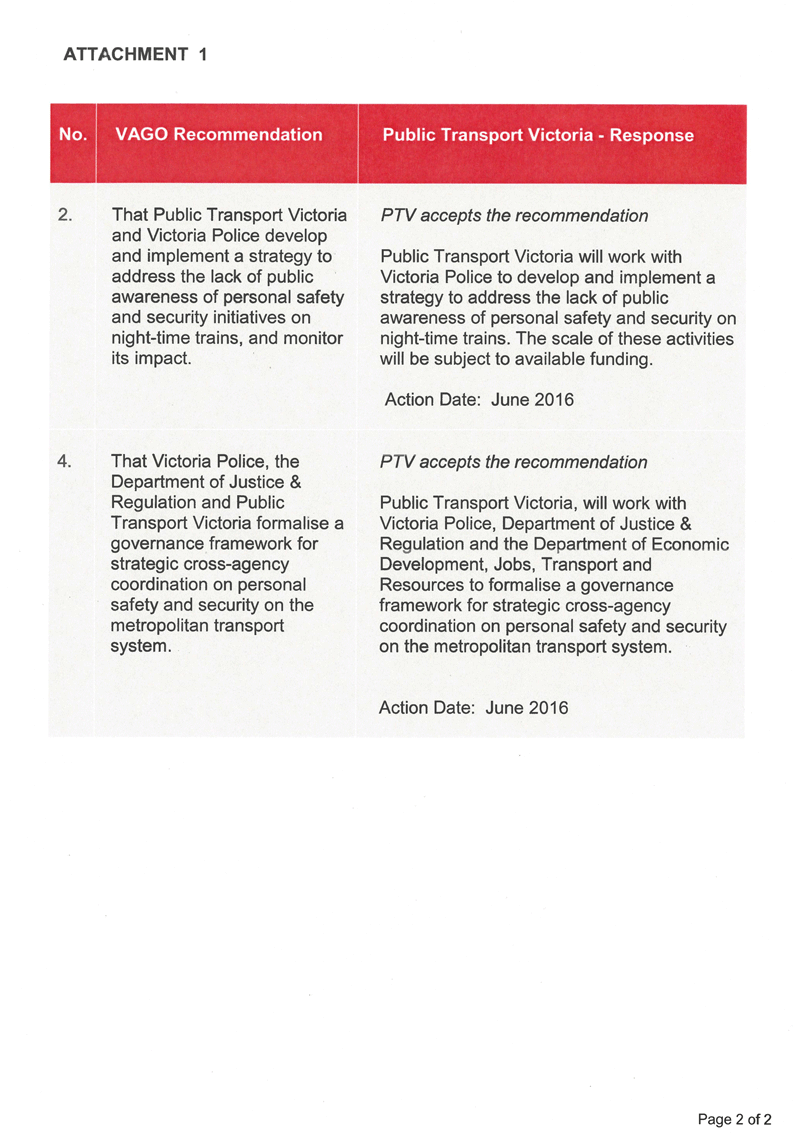

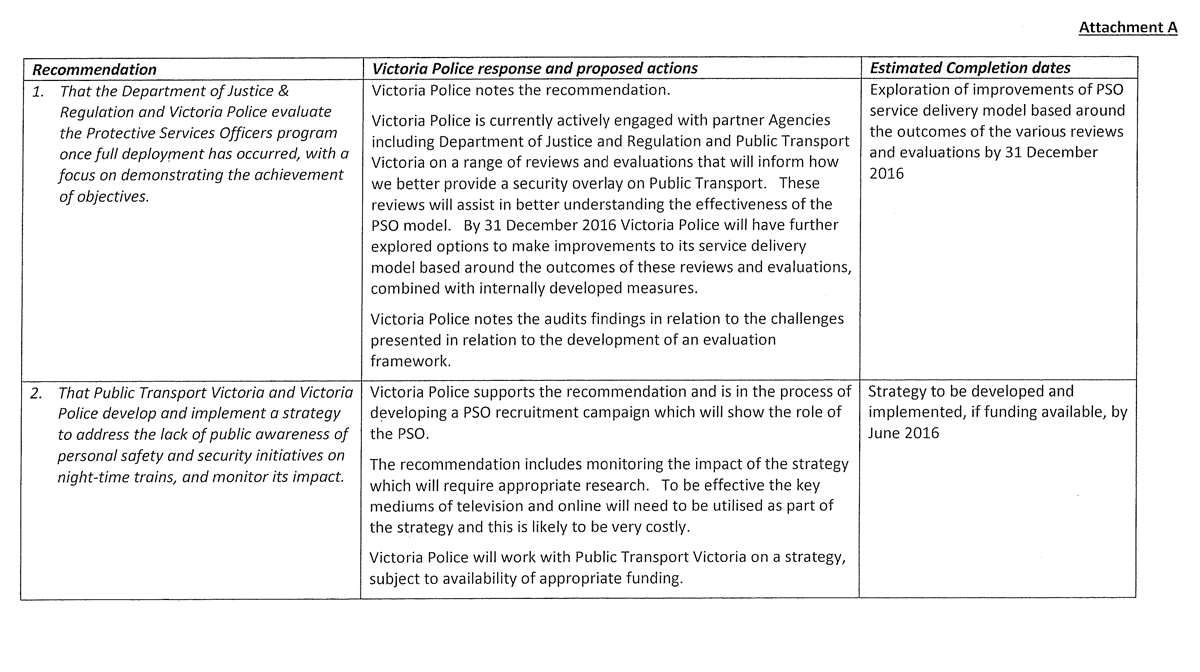

Recommendations

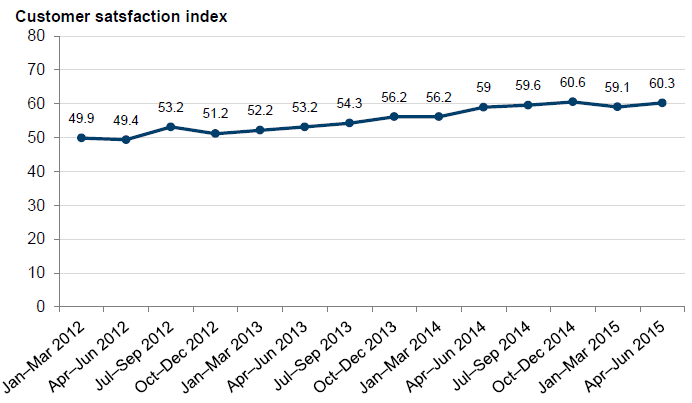

- That the Department of Justice & Regulation and Victoria Police evaluate the protective services officers program once full deployment has occurred, with a focus on demonstrating the achievement of objectives.

- That Public Transport Victoria and Victoria Police develop and implement a strategy to address the lack of public awareness of personal safety and security initiatives on night-time trains, and monitor its impact.

- That Victoria Police establishes a performance monitoring framework for the protective services officers program, which captures accurate and relevant data to inform future decisions to improve effectiveness and efficiency.

- That Victoria Police, the Department of Justice & Regulation and Public Transport Victoria formalise a governance framework for strategic cross-agency coordination on personal safety and security on the metropolitan transport system.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Justice & Regulation, Victoria Police and Public Transport Victoria throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Public transport services and, in particular, trains play a significant role in connecting people to a range of social and economic opportunities such as employment, education and services. Passengers should feel safe as they use these services, regardless of the time of day or night.

Public perceptions of safety on the train system can impede patronage and may be influenced by personal insecurity, media reporting of incidents, poorly lit areas, and vandalism and graffiti.

During 2014 there were more than 9 600 criminal offences reported on Melbourne's train system. Approximately half of these occurred after 6 pm. In the same year, around 222.2 million commuters used the metropolitan train network. Patronage after 6 pm accounted for around 17 per cent of the total, meaning individuals were at greater risk of being exposed to crime at night.

Fear of crime can lead to a reduction in the number of people using the train system. As part of a commitment to make the train network safer, in 2011 the former government committed $212 million over four years to recruit, train and deploy 940 protective services officers (PSO) at 212 metropolitan rail stations and four regional stations, every night from 6 pm until after the last train. This was intended to:

- deter crime, violence and anti-social behaviour on the train system

- improve perceptions of safety for commuters on the train system

- enhance opportunities for local crime prevention and intelligence gathering to assist broader policing initiatives and ensure public safety and confidence within railway precincts.

History of protective services officers

PSOs have existed since 1987 when the Police Regulation (Protective Services) Act 1987 came into operation, but they were used to provide specialist security services to government, not for policing the transit system. Historically, PSOs could only be appointed for the protection of persons holding certain official or public offices and of certain places of public importance, such as Parliament House and the Shrine of Remembrance. After the 2010 state election, the former government followed through on its election commitment to improve safety on the public transport network through the provision of a second category of PSOs, known as transit PSOs—referred to as PSOs throughout the remainder of this report.

1.1.1 Roles and responsibilities

Department of Justice & Regulation

The Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) provides advice to the Minister for Police on the PSO program. This includes developing legislation to support the role and deployment of PSOs, providing a secretariat function to guide implementation, and reporting to Cabinet on program implementation. DJR was responsible for facilitating the report back to government on the progress of the PSO initiative, the emerging cost pressures associated with the attraction and retention of PSOs, and any impacts the policy had in improving perceptions of public safety.

Victoria Police

Victoria Police is responsible for the practical implementation of the PSO policy and operations, including the recruitment and training of PSOs, determining the priority order for deployment, and monitoring and reporting on the progress and effectiveness of the initiative. Victoria Police works with Public Transport Victoria (PTV) in determining deployment order.

Public Transport Victoria

PTV is responsible for making sure the necessary train station infrastructure is in place to support PSOs' functions. This includes:

- an area for PSOs to carry out administrative tasks

- a transitions room where apprehended persons can be held until safely collected by a member of the police force

- a meals area and secure amenities.

Broader rail security is jointly managed by Metro Trains—the current private train operator—PTV and Victoria Police.

Photograph courtesy of Public Transport Victoria.

1.1.2 Related safety and security initiatives

Alongside PSOs, there are several other types of staff who work across the metropolitan train system to deter crime and ensure the personal safety and security of commuters. Figure 1A provides an overview of these personnel.

Figure 1A

Metropolitan train safety and security personnel

|

Personnel |

Description |

|---|---|

|

Transit police officers |

Transit police officers are Victoria Police officers assigned to public transport duties. Their role is to ensure public safety and security, and prevent crime on public transport. Transit police work across all modes of public transport and play a key role in directing and supervising the work of PSOs. |

|

Authorised officers (AO) |

AOs' primary role is reducing fare evasion, but they also perform customer assistance, safety, security, crime prevention and crime deterrence duties. AOs operate at train stations as well as on board trains and are employed by public transport operators. |

|

Customer service staff |

Customer service staff provide customer assistance. They also play a role in reducing fare evasion, safety and crime deterrence. Customer service staff are employed by public transport operators. Premium stations are staffed from first to last train, and host stations have customer service staff during the morning peak. Customer service staff are also deployed to support major events or disruptions. |

|

Private security |

Private security companies may be engaged by public transport companies or PTV to supplement existing safety, security, crime prevention and deterrence measures. Private security may be used to support major events at major stations. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

These resources are also supported by built environment and technology solutions. These are designed, implemented and managed by PTV or the train operator or both, depending on the location and primary purpose. They include:

- closed circuit television systems

- passenger emergency communication systems

- lighting and station platform design

- designated platform safe zones.

1.2 Relevant legislation

PSOs' functions and powers are detailed in the Victoria Police Act 2013. The function of PSOs assigned to transit roles is to provide protection to the general public on the train network.

Figure 1B outlines the main powers PSOs have. These powers may only be exercised while on duty and in designated places as set out in the Victoria Police Regulations 2014. Designated places are:

- railway premises, which include stations, trains and tracks

- car parking areas near train stations

- roads used to access train stations

- bus stops and taxi ranks that are next to train stations

- council car parking areas adjoining train stations

- private land that is used as a car park or related to public transport that is near a train station.

Designated places may be changed through amendments to the Victoria Police Regulations 2014.

Figure 1B

PSO powers

|

Powers |

|---|

|

Search and seizure |

|

PSOs on duty at a designated place have the authority to search without a warrant and to seize items under:

|

|

Arrest of persons |

|

PSOs on duty at a designated place are authorised to:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Initial deployment

PSOs were progressively deployed across the metropolitan train network as personnel became available and the station infrastructure required to support PSO operations was completed. Flinders Street and Southern Cross were the first stations to have PSOs deployed, with operations commencing on 22 February 2012.

Deployment to additional stations commenced in mid-May 2012. The initial target of 940 PSOs was reached in November 2014 and covered 166 of the 212 metropolitan stations plus four major V/Line regional stations. By 1 June 2015, PSOs had been deployed to 177 stations.

In February 2014, DJR informed government that 940 PSOs were not sufficient to provide the coverage required. In July 2014, an additional 96 PSOs were approved by government for deployment by June 2016, increasing the total to 1 036 for coverage at 216 rail stations. The current government remains committed to this.

The PSO program rollout order was considered an operational decision, reserved to the Chief Commissioner of Police. Victoria Police and DJR provided the Minister for Police and government with regular updates informing them of its progress.

The order in which infrastructure was completed did not precisely follow the rollout priority order, due to differences in the complexity of the different builds. When multiple stations were ready for deployments but there were not enough PSOs, priority was given to safety concerns and community needs.

Photograph courtesy of Public Transport Victoria.

1.4 PSOs today

As at 31 August 2015, there were 998 PSOs deployed at train stations across the state, as detailed in Appendix A.

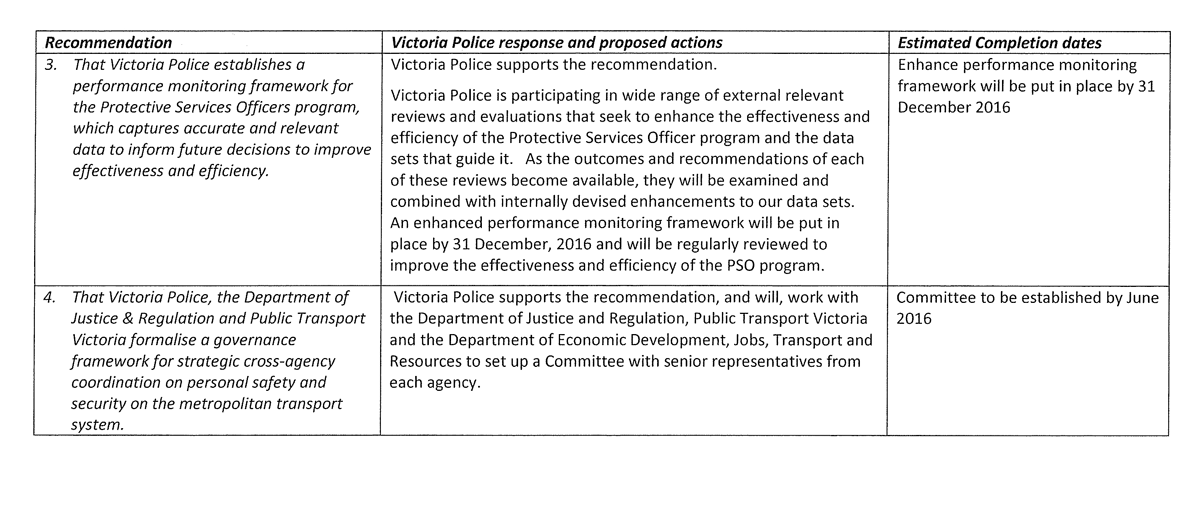

As shown in Figure 1C, almost 91 per cent of PSOs are male and, of these, around three quarters are 20–39 years old.

Figure 1C

Deployed PSOs by age and gender, as at 31 August 2015

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Victoria Police.

The Victoria Police Manual– Protective Services Officers on the rail network details the roles and responsibilities of PSOs. Victoria Police's Transit Safety Division has responsibility for managing PSOs, including rostering, supervision, performance management, and health and safety matters.

When they have graduated from training, PSOs undergo a three-month coaching period. During this time, they commence duty at the Victoria Police Centre and then travel to their rostered location. Once their coaching period is complete, PSOs are allocated to a train station where they commence their duties from a nearby police station or facility.

1.5 Previous VAGO audit

Personal Safety and Security on the Metropolitan Train System

In June 2010, VAGO tabled the performance audit report Personal Safety and Security on the Metropolitan Train System. This audit examined progress in improving personal safety by assessing whether Victoria Police and the then Department of Transport had:

- designed programs using sound evidence and worked together to reduce crime and make passengers feel safe when using Melbourne's trains

- monitored and evaluated programs to understand their effectiveness

- achieved the standards and targets set for personal safety and security.

The audit found that Victoria Police and the then Department of Transport had been successful in reducing crime on Melbourne's train system. However, the approach to improve passengers' perceptions of safety had not been effective and required focused attention.

The audit made a number of recommendations to Victoria Police and the former Department of Transport, all of which were accepted, including that they:

- apply the evidence-based approach used to manage crime to the management of perceptions of safety

- have regular high-level meetings to better assure information sharing and the coordination of personal safety initiatives

- improve project evaluation by clearly defining the expected benefits and how they will be measured

- set targets for reducing crime and improving perceptions of safety based on the evidence about trends.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

This audit aimed to determine the effectiveness of the PSO program by assessing if:

- it has reduced crime on the Melbourne metropolitan train system and improved public perceptions of the safety of train travel, particularly at night

- appropriate advice supports key decisions on the deployment of PSOs

- governance arrangements for personal security and safety initiatives across Victoria's train system optimally support and leverage the work of PSOs.

The audit did not involve:

- a detailed examination of safety and security on the V/Line regional train network, as the PSO initiative was primarily targeted at metropolitan stations

- an examination of the conduct of individual PSOs, or examination of the processes for investigating complaints or allegations of PSO misconduct.

1.7 Audit method and cost

To determine whether PSOs have been effective, the audit examined:

- statistics and data relating to detected and reported crime, and perceptions of safety on the metropolitan train network

- advice provided to government regarding the PSO program

- the cost of the PSO program, including related infrastructure costs

- governance and coordination arrangements for personal safety and security programs in operation on the metropolitan rail network

- progress on addressing relevant recommendations from the 2010 audit Personal Safety and Security on the Metropolitan Train System.

The cost of the audit was $360 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

Part 2 examines the impact of PSOs on commuter and community perceptions of the safety of the metropolitan train system at night, as well as their impact on crime. It also reviews the degree of integration of the PSO program with other safety and security initiatives.

Part 3 examines the advice provided to government regarding the deployment model and the processes in place for implementing the initiative and supporting monitoring and continuous improvement.

2 Impact of PSOs

At a glance

Background

Introducing protective services officers (PSO) at Melbourne metropolitan train stations was intended to improve perceptions of safety and reduce crime and antisocial behaviour on the train network at night.

Conclusion

Perceptions of the safety of the metropolitan train system at night have improved, but this cannot be solely attributed to the PSO program. Crime data limitations mean it is uncertain if recorded crime increases since the start of PSO deployment is due to rises in criminality or increased detection and reporting. The lack of a public awareness strategy means that agencies are not capitalising on the presence of PSOs to increase patronage.

Findings

- Perceptions of safety of the train system at night have improved.

- Recorded crime at train stations has increased in part due to increased detection and reporting.

- There are no strategies in place to increase public awareness of PSOs and their roles.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Justice & Regulation and Victoria Police evaluate the protective services officers program once full deployment has occurred, with a focus on demonstrating the achievement of objectives.

- That Public Transport Victoria and Victoria Police develop and implement a strategy to address the lack of public awareness of personal safety and security initiatives on night-time trains, and monitor its impact.

2.1 Introduction

Protective services officers (PSO) were introduced to Melbourne metropolitan train stations in early 2012 to increase community perceptions of the safety of night-time train travel and to reduce crime and antisocial behaviour.

2.2 Conclusion

Perceptions of safety of the metropolitan train system at night have improved since the start of the PSO program. However, it cannot be determined how much this improvement can be directly attributed to PSOs and how much is due to other factors.

Conversely, recorded crime at train stations has increased since the start of the PSO program but, due to data limitations, it cannot be determined if this increase is due to rises in criminality or increased detection and reporting.

The lack of a public awareness strategy means that agencies are not capitalising on the presence of PSOs to improve perceptions of safety and increase patronage on trains after 6 pm.

2.3 Perceptions of safety

A key purpose of the PSO program was to increase perceptions of the safety of Melbourne's train system after dark. Although government did not establish any specific targets for achieving this outcome, various surveys have identified improvements in this area.

However, there have been other changes on the metropolitan rail network that could have contributed to increased perceptions of safety, including increases in the number and patrol frequency of authorised officers and transit police, station improvements and increases in train service frequency. The presence of PSOs alone may also not be enough to improve perceptions of safety, particularly at large, multi-platform stations where PSOs may not be visible at all times. It is not possible to fully isolate the effect of PSOs on perceptions of safety from the impact of other factors.

Limitations of the data

Nevertheless, in order to assess the impact PSOs have had on perceptions of safety, three surveys have been identified which measure this from the perspective of:

- night-time users—evaluation study commissioned by the Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) and Public Transport Victoria (PTV) in order to report back to government

- commuters in general—Customer Satisfaction Monitor (CSM) commissioned by PTV

- public transport users—National Survey of Community Satisfaction with Policing (NSCSP) used by Victoria Police.

All three surveys show an upward trend in perceptions of safety since the start of the PSO program. However, only the evaluation study was specifically designed to consider the impact of PSOs.

The CSM and NSCSP are useful for understanding general perceptions of safety but lack the specificity required to isolate the effect of PSOs.

The NSCSP covers all modes of public transport, so the improvements noted in this survey cannot be solely attributed to the PSO program. Although the CSM is specific to metropolitan trains, the interview pool includes users who may not travel during PSO deployment times or to stations where PSOs have been deployed.

2.3.1 Night-time train users' perceptions of safety

Several studies have found that perceptions of safety have a greater influence on community behaviour than the actual crime rate. In terms of public transport, community perceptions that travel at night is unsafe are likely to lead to fewer people using night-time services.

Improving perceptions of the safety of Melbourne's train system at night is a key objective of the PSO program. In approving funding for the program in 2011, government specifically requested a report back on the impact of PSOs on perceptions of safety, but not on their impact on crime rates.

Evaluation study

DJR and PTV commissioned research on the impact of PSOs and the safety perceptions of night-time metropolitan train users and members of the broader Melbourne community. Over 5 400 people were interviewed.

The study was carried out in two parts:

- In 2012, commuters at six railway stations were surveyed prior to PSOs being deployed in order to establish a baseline.

- An evaluation survey was conducted one year later at the same six stations, after PSOs had been deployed.

The key objectives of the research were to:

- measure baseline perceptions of security when travelling by metropolitan train after 6 pm, both on board trains and at stations

- gauge levels of support for PSOs

- assess awareness of PSOs, their role and how this awareness had been obtained

- identify any potential improvements around how PSOs operate from a customer perspective.

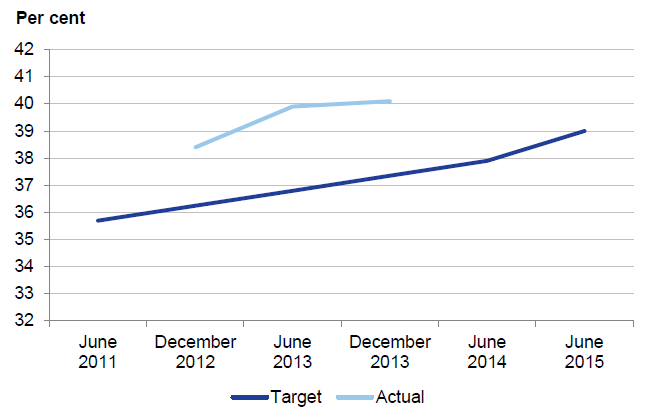

Overall, the study showed that safety perceptions of night-time train users increased by the end of the first year of PSO deployment. This is illustrated in Figure 2A. However, given that this involved only six stations and occurred one year into the initiative, it is not possible to determine whether this increase is representative of the wider train network and has continued for the remainder of the deployment of PSOs.

Figure 2A

Safety perceptions of night-time train users

Note: Neutral responses have been omitted from the figure above.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Public Transport Victoria.

The study also identified that not having PSOs at train stations was not necessarily the reason why commuters did not travel at night. It found that around half the survey respondents had no need to travel by train after 6 pm.

The study found that others who did not routinely travel by train after 6 pm chose not to due to safety concerns. For these people, safety concerns were either the primary driver of their decision or influenced their decision to some extent. Around 3 per cent of respondents had no safety concerns about travelling by train after 6 pm.

2.3.2 Commuters' perceptions of safety

PTV's CSM is a monthly survey where commuters are asked to rate a number of aspects of public transport services, one of which is their perception of safety on trains. Customer satisfaction is tracked on an index of 0 (totally dissatisfied) to 100 (totally satisfied).

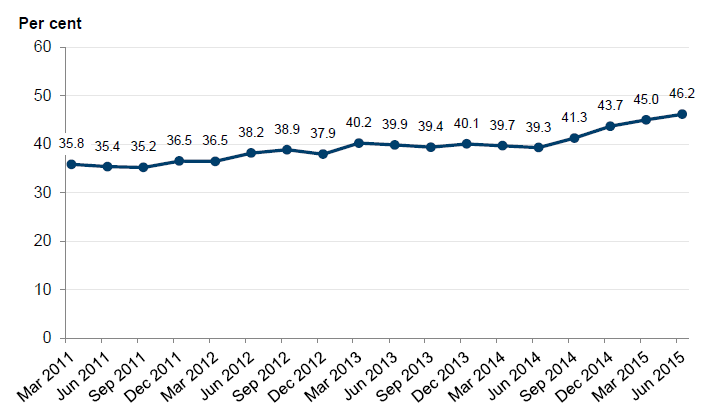

Figure 2B shows that satisfaction with personal security at train platforms at night has increased by approximately 10 points since the start of PSO deployment in February 2012. However, as noted above, the extent to which this can be attributed to PSOs cannot be determined.

Figure 2B

Satisfaction with personal security on train platforms after dark

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Public Transport Victoria.

2.3.3 Community perceptions of safety

Victoria Police uses NSCSP data to assess changes in community confidence and satisfaction with policing. One of the datasets measured by NSCSP is the percentage of the population who feel safe on public transport at night. Figure 2C shows that according to NSCSP data, the percentage of Victorians who feel safe on public transport at night has risen by approximately 10 per cent since February 2012.

Figure 2C

Perceptions of safety on public transport at night

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Victoria Police.

2.4 PSOs' impact on crime

As well as increasing perceptions of safety, the PSO program intended to decrease crime and antisocial behaviour. It is not possible to assess whether PSOs have had this effect due to limitations in the available data.

An increase in police numbers typically leads to an increase in recorded crime. This is because more police personnel are available to detect more crime. The incidence of reported crime can also increase due to the better accessibility of police.

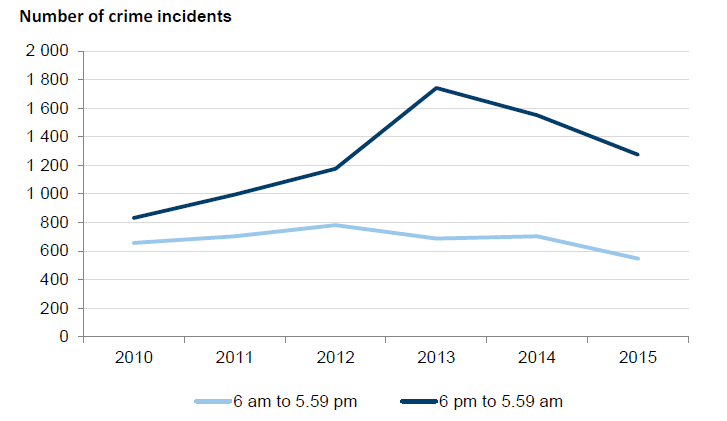

An analysis of the first 11 stations to have PSOs deployed shows a sharp increase in recorded offences coinciding with the deployment of PSOs and their first year of operation, with a gradual reduction in recorded offences since then. This is illustrated in Figure 2D.

Figure 2D

Recorded crime at priority stations

Note: PSOs are deployed from 6 pm until the last train, which is typically 2–3 am. See Figure 2E for information on priority stations.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by the Crime Statistics Agency.

The list of priority stations used for this analysis and the date of PSO deployment to those stations is shown in Figure 2E. Priority is determined by Victoria Police analysis of crime, patronage and other relevant factors for all metropolitan train stations.

Figure 2E

Priority stations

|

Priority stations |

PSO deployment date |

|---|---|

|

Flinders Street |

22 February 2012 |

|

Southern Cross |

22 February 2012 |

|

Footscray |

16 May 2012 |

|

Dandenong |

28 May 2012 |

|

Melbourne Central |

12 June 2012 |

|

Parliament |

03 July 2012 |

|

Richmond |

03 July 2012 |

|

North Melbourne |

26 July 2012 |

|

Box Hill |

07 August 2012 |

|

Epping |

07 August 2012 |

|

Noble Park |

07 August 2012 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Victoria Police.

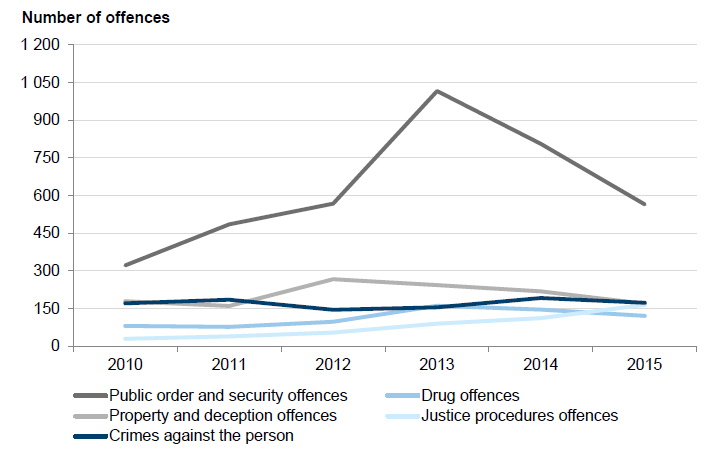

The large increase in crimes shown in Figure 2D is mainly due to the additional detection of public order and security offences, including disorderly and offensive conduct , public nuisance and weapons offences. Figure 2F illustrates the sharp increase in these types of offences between 2012 and 2013 coinciding with the deployment of PSOs.

Figure 2F

Offence by type at priority stations from 6 pm to 5.59 am

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by the Crime Statistics Agency.

It is not possible to analyse the impact of PSOs on crime across the entire metropolitan network. This is partly because PSOs will not be fully deployed to all stations until June 2016. It is also due to the limitations of Victoria Police's systems and processes for recording crime.

Victoria Police members record offence information in the LEAP database. When recording in LEAP, some data is entered by selecting from dropdown menus, while other data is typed into free-text fields. Not all fields are compulsory.

While the flexibility of free-text and optional fields is necessary due to the wide range of possible crimes and circumstances, it can inhibit accurate reporting. Members can select a train station as an offence location in a dropdown menu, however, there is no compulsory field to enter the name of the train station. Approximately 13 per cent of the data provided by the Crime Statistics Agency could not be accurately attributed to a particular train station.

Ensuring that crimes occurring at train stations are attributed to a specific station will enable more accurate analysis of the effect of PSOs and other police resources on the metropolitan train network.

2.5 Public awareness

A key priority for PTV is to improve perceptions of safety on the train network. This is also one of the most effective ways to increase patronage. Until efforts are made to increase public awareness of PSOs and their duties, the full effect and value of the PSO initiative cannot be realised.

Photograph courtesy of Public Transport Victoria.

2.5.1 Lack of public awareness

Research commissioned by PTV in 2014 shows that there is a lack of awareness of the presence and functions of PSOs, particularly among those who do not use trains at night.

Figure 2G shows that just over half of the representative sample of Melbourne residents who do not use public transport, or who only use public transport during the day, were aware that PSOs currently patrol most metropolitan train stations after 6 pm.

Figure 2G

Awareness of PSOs

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Public Transport Victoria.

Several organisations, including other integrity bodies, reported that the public seemed unaware of the roles and responsibilities of PSOs and often did not differentiate between authorised officers and PSOs.

2.6 Impact of lack of awareness

Knowing PSOs are present and observing them patrolling platforms increases commuters' perceptions of safety.

In 2014 PTV commissioned research in order to identify factors that had the greatest impact on safety perceptions and patronage. This research found that guaranteeing PSOs at stations had the potential to generate as many as 253 million additional trips per year across the Victorian public transport system.

However, there is insufficient data available to assess whether PSOs have had any impact on patronage. Accurate patronage data is not available prior to June 2013, due to changes in commuter behaviour and to PTV's patronage calculation methodology during the changeover of ticketing systems from Metcard to myki.

In 2015, PTV advised that it was developing an information campaign to raise public awareness of the personal safety and security initiatives in place on the train network, with the aim of increasing patronage by increasing perceptions of safety. However, following discussions with Victoria Police in late 2015, PTV no longer plans to undertake this campaign.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Justice & Regulation and Victoria Police evaluate the protective services officers program once full deployment has occurred, with a focus on demonstrating the achievement of objectives.

- That Public Transport Victoria and Victoria Police develop and implement a strategy to address the lack of public awareness of personal safety and security initiatives on night-time trains, and monitor its impact.

3 Maximising the PSO program's efficiency and effectiveness

At a glance

Background

Government and agency decision-making for the protective services officers (PSO) program has been focused on operational imperatives, but ensuring efficiency and effectiveness in the future requires a strategic focus.

Conclusion

Quality comprehensive advice was provided to government throughout the establishment and rollout of the PSO program, however, performance monitoring deficiencies will compromise Victoria Police's ability to inform future decision-making. The lack of strategic cross-agency coordination reduces confidence in the value of ongoing personal safety and security initiatives.

Findings

- Advice provided to government on the establishment, rollout and initial impact of the PSO program was comprehensive.

- Key performance indicators for the PSO program are not underpinned by relevant or accurate data and have not been consistently monitored.

- There is a lack of strategic coordination between agencies regarding personal safety and security on the metropolitan rail system.

Recommendations

- That Victoria Police establishes a performance monitoring framework for the protective services officers program, which captures accurate and relevant data to inform future decisions to improve effectiveness and efficiency.

- That Victoria Police, the Department of Justice & Regulation and Public Transport Victoria formalise a governance framework for strategic cross-agency coordination on personal safety and security on the metropolitan transport system.

3.1 Introduction

By the end of June 2016, protective services officers (PSO) are expected to be deployed to all Melbourne metropolitan train stations. To make sure that the PSO program is operating effectively and efficiently, and to ensure the quality of future advice to government on improvements to the initiative, appropriate performance monitoring measures must be in place.

The PSO program is one of several initiatives currently operating on the train network aimed at reducing crime and increasing perceptions of safety. In order to be fully effective and to operate efficiently, the PSO program needs to integrate with these other safety and security programs. The need for integration also extends to the organisational level—with multiple agencies and organisations sharing responsibility for personal safety and security on the train system, effective coordination is vital to avoid duplication and to maximise the value of these programs individually and collectively.

3.2 Conclusion

Comprehensive advice was provided to government to support the initial decisions on the establishment and deployment of PSOs.

There is potential for PSOs to be used more efficiently and effectively. However, until Victoria Police improves its approach to monitoring the performance of the PSO program, it will not have the necessary evidence to inform future government decisions about their deployment and use.

The focus of the PSO program to date has been operational—on recruitment, training, deployment and immediate impact. There is now a need to shift this focus to drive strategic cross-agency coordination in order to maximise the community benefit of the current suite of personal safety and security initiatives in place across the public transport system.

3.3 Advice to government

Advice provided to government to support decisions on the establishment and deployment of the PSO program was comprehensive. The report back to government following the first 18 months of the program was focused on the government's priorities at the time, but it also advocated for changes to the PSO program in order to improve efficiency and effectiveness. While government chose not to follow this advice, the options presented were nevertheless comprehensive and soundly based.

3.3.1 Policy development and initial advice

In late 2009, government made its first statement about its PSO policy, the number of PSOs to be recruited and the initial cost of the program, which were formulated without input from Victoria Police. Government intended to establish a force of 940 PSOs to patrol train stations from 6 pm until the last train, at an estimated cost of $161.3 million over four years. It also expected that two PSOs were to be deployed per station and that they were not to be redeployed for other tasks.

In early 2011, Victoria Police was given the opportunity to provide input and prepared a business case for government consideration. The business case noted that government's funding estimate would not be sufficient for recruiting, training and deploying 940 PSOs. It also noted that 940 PSOs would be insufficient to provide two PSOs at every train station from 6 pm until the last train—full coverage would have required 1 090 PSOs.

Victoria Police provided government with several options on how to implement its policy. The preferred option was the deployment of 940 PSOs by November 2014. This would enable the coverage of up to 195 of the 212 metropolitan train stations and four priority regional stations, at a cost of $226.4 million over four years.

Government endorsed the preferred option and, in May 2011, approved $212.3 million over four years for the program.

3.3.2 Commencement and rollout

The recruitment and deployment of PSOs was generally well managed, and the methodology used to determine the program rollout order was sound and underpinned by comprehensive data and evidence.

PSOs were deployed progressively across the metropolitan train network, as personnel graduated from their training program and as the station infrastructure required to support PSO operations was completed. Flinders Street and Southern Cross were the first stations to have PSOs deployed on 22 February 2012. Deployment to additional stations commenced in mid-May 2012. By 1 June 2015, PSOs had been deployed to 177 stations (173 metropolitan and four regional). A full list of these stations is provided in Appendix A.

The PSO program rollout order was considered an operational decision, reserved to the Chief Commissioner of Police. However, Victoria Police and the Department of Justice & Regulation (DJR) provided the Minister for Police and government with regular progress updates.

3.3.3 Reporting to government and efficiencies

When funding for the PSO program was approved in 2011, government requested the Minister for Police to report back on key areas to inform the 2013–14 Budget deliberations. The report back was to cover:

- the progress of PSO recruitment and deployment against the targets set in the business case

- emerging cost pressures associated with the attraction and retention of PSOs

- any impact the policy was having in improving perceptions of public safety.

In reviewing the PSO deployment to prepare for the report back, Victoria Police saw an opportunity to gain efficiencies, reduce costs and improve effectiveness if changes were made to how PSOs were deployed.

As well as providing a report on the three requested areas, the agencies also provided government with a new business case comprehensively detailing options for reducing the cost and increasing the effectiveness of the PSO program. The option preferred by Victoria Police and DJR was to change the way PSOs were deployed.

Figure 3A

PSO deployment models

|

Victoria Police proposals have focused on two kinds of PSO deployments or patrols:

While there are other potential deployment models that could be used for PSOs in the future, to this point Victoria Police has focused on the static and clustered models, including combinations of the two. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The business case noted that 940 PSOs would enable static deployment at 138 stations, with clustered deployments at all other metropolitan stations as described in Figure 3A. Victoria Police noted that this model provides the capacity for flexibility and intelligence-based tasking, enabling personnel to be sent where they will be most effective. Total funding for this option was $58.9 million over five years—around $100 million less than to recruit and deploy the 1 074 PSOs required to provide a static presence at every station.

While this option was initially approved, government subsequently reversed its decision in May 2014, instead favouring the option of increasing PSO numbers to 1 074 and retaining static deployments.

3.4 Performance monitoring

Despite government statements emphasising that the PSO program had been established to reduce crime and antisocial behaviour on the train system, its impact on crime was not one of the areas that government requested reports on. Rather, government requested progress reports against recruitment and rollout targets, cost pressures and any impact PSOs had on perceptions of the safety of the train system.

While agencies had access to sufficient data to provide advice to government on some of these areas, Victoria Police does not have an effective performance monitoring regime in place to understand how effective PSOs have been or to inform future government decisions about their deployment and use.

3.4.1 Benefits-management regime

In 2013, Victoria Police established a benefits-management regime to track the impact of the PSO program and measure its effectiveness. The regime was intended for internal use by Victoria Police to identify potential areas for improvement.

Victoria Police established the following key performance indicators (KPI):

- increase in community perceptions of safety when travelling on public transport at night

- increase in the number of transit PSO patrol hours in and around train stations

- changes in the number of infringements issued by PSOs.

Victoria Police advised that minimising cost and administrative burdens was a key driver in selecting these KPIs and the data that underpinned them. It chose data sources it already had and which would require minimal additional work, to avoid a situation where the resources required for producing the data outweighed the usefulness of the reporting. However, the data sources have proven insufficient to enable reporting on PSO performance, negating the efficiency Victoria Police was aiming to achieve.

Furthermore, Victoria Police abandoned performance reporting for the PSO program in late 2013, due to lack of staff resources. There has been no internal tracking of the effectiveness of the PSO program since then.

Victoria Police should develop methods for assessing the effectiveness of the PSO program that take into consideration the limitations of the available data. It should also consider what will be needed to enable reporting to government on the efficiency and effectiveness of PSOs once they have become embedded in the system. This will enable government and Victoria Police to decide how to best use the significant resources made available to address public safety concerns.

3.4.2 Key performance indicators

Victoria Police established and reported against three KPIs up until late 2013.

KPI 1: increase in community perceptions of safety when travelling on public transport at night

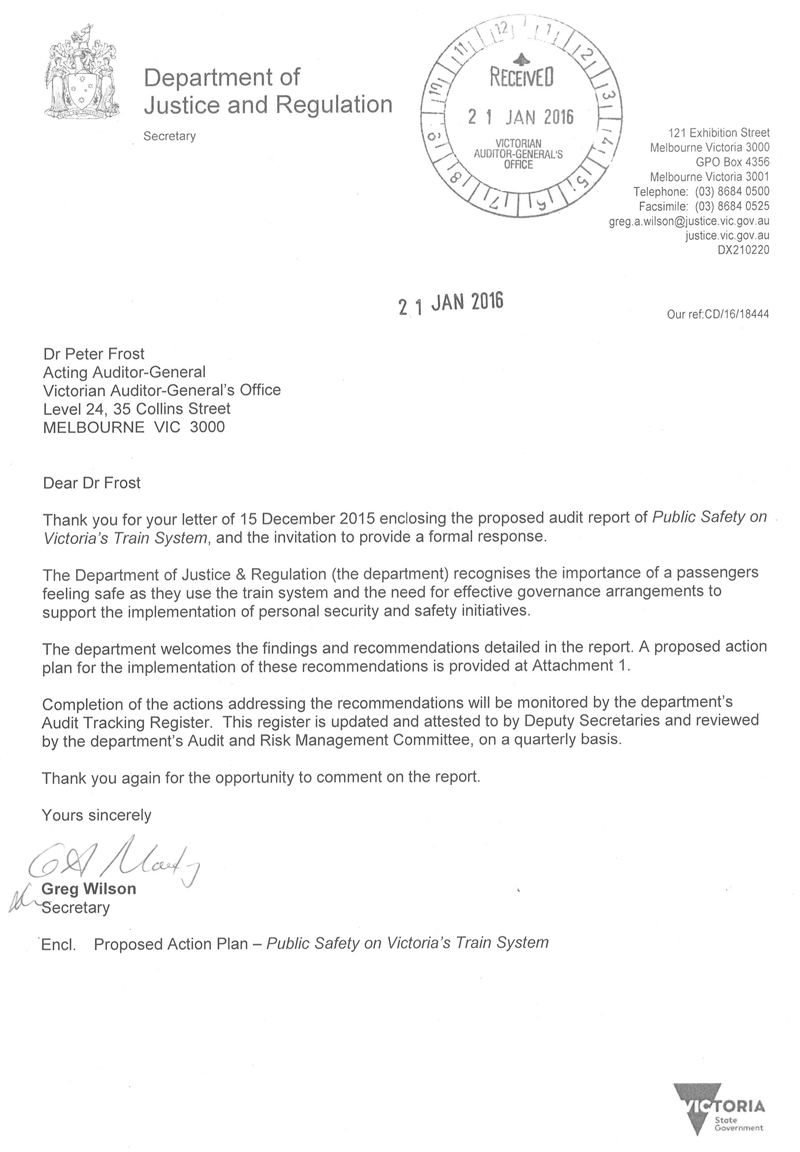

Victoria Police measured this KPI using data collected by the National Survey of Community Satisfaction with Policing (NSCSP). NSCSP measures how safe people feel their community is and how happy they are with policing. Although NSCSP data is an effective measure of the impact of all public safety and security initiatives, it does not differentiate between trains and other modes of public transport. Therefore, while it is a useful reference point, it is not specific enough to provide assurance that the deployment of PSOs led to the increase in perceptions of safety.

Additionally, Victoria Police did not set a realistic performance target for this KPI. After analysing the data, Victoria Police set a baseline of 35.7 per cent and an end target of 39 per cent, to be achieved by mid-2015. As shown in Figure 3B, the end target was surpassed by the beginning of 2013, but Victoria Police did not review its targets in light of this.

Figure 3B

Percentage of people who felt safe on public transport at night, target vs actual performance

Note: No data on actual performance was collected after 2013.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Victoria Police.

KPI 2: increase in the number of transit PSO patrol hours in and around train stations

This KPI was never reported against and was removed due to a lack of data. It was intended to track the deployment of PSOs, however, Victoria Police's systems for recording patrol hours were not able to readily differentiate between those of PSOs and other police members.

KPI 3: changes in the number of infringements issued by PSOs

This KPI was selected by Victoria Police to measure the effectiveness of PSOs over time. It was expected that the number of infringements issued would climb as more and more PSOs were deployed, reach a peak, plateau and then decline after 18−24 months. Victoria Police set the baseline and target for this KPI in mid-2012, aiming for an increase in the number of infringements issued of 5 per cent every six months to 30 June 2014, then a decrease of 5 per cent to December 2015. Data provided by Victoria Police, shown in Figure 3C, reflects the expected outcome. However, Victoria Police only produced one report on performance against this KPI.

Figure 3C

Total infringements issued by PSOs

|

Year |

Total number of infringements |

|---|---|

|

2011–12 |

1 858 |

|

2012–13 |

14 392 |

|

2013–14 |

17 784 |

|

July–December 2014 |

12 131 |

|

Total |

46 165 |

Note: Infringement data is only available to the end of December 2014.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from data supplied by Victoria Police.

This KPI was only to apply to the PSO program as a whole—the effectiveness of individual PSOs was not measured by this KPI, and individuals have never been set targets relating to infringements.

Other KPIs

Two further potential KPIs were identified, which were planned to be added to the performance reporting regime once a separate project to improve the recording of crime data was completed. However, this project was cancelled and these KPIs were never included, as sufficiently accurate data to report against them was not available.

3.5 PSO operations and training

Victoria Police's focus since the start of the PSO program has been on PSO training and operations, to ensure its personnel have the knowledge, support and resources needed to carry out their duties. It has sufficient processes in place to ensure that PSOs' training and operations are continuously improved.

3.5.1 PSO operations

Victoria Police uses an evidence-based model to determine its deployments, which VAGO's 2010 audit Personal Safety and Security on the Metropolitan Train System found was an effective way of ensuring personnel are deployed to match priorities and need. However, Victoria Police continues to deploy PSOs in accordance with the government's policy of two PSOs per station.

PSOs are only one component of Victoria Police capability operating on the metropolitan train system. From 6 pm until the last train, Victoria Police endeavours to ensure personal safety and security on the metropolitan train system through:

- PSOs, currently deployed at two per station, with deployment to all metropolitan stations to be completed by June 2016

- transit police, either supervising PSOs or deployed to patrol the network according to an evidence-based deployment model

- Victoria Police members, deployed in response to an incident.

PSOs are now fully integrated with other Victoria Police units. Communications between PSOs and other members of Victoria Police are conducted through established and effective channels. Figure 3D describes the typical preparation PSOs go through each day prior to commencing a shift at their allocated train station.

Figure 3D

PSO activity prior to station duty

|

PSO shifts start prior to their arrival at their rostered train station. Before they commence duty at a train station, PSOs arrive at their home police station. Once there, they typically check their work emails, intelligence reports and any internal Victoria Police notices. They are also issued with their firearm and radio. An operational briefing is delivered by their shift supervisors. The operational briefing is prepared by the Transit Safety Division and contains the same information for all PSOs on duty that night. It will contain relevant intelligence information, operational pointers or reminders, and briefings on issues specific to the local area. After the briefing, PSOs move to their rostered train station. Once there, they will check in with the stationmaster and any customer service staff to inform them that they are on duty, as well as to see if there are any issues they need to be aware of. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Operational policies and processes

Operational policies and processes for PSOs are documented, readily accessible to all PSOs, and regularly reviewed. PSOs' operational instructions and processes are articulated in the Victoria Police Manual (VPM) and relevant Chief Commissioners Instructions. Victoria Police Manual—Protective Services Officers on the railway network details the roles and responsibilities of PSOs and how these responsibilities align with broader Victoria Police policy. The VPM is accessed through the Victoria Police intranet to ensure members are always using the most recent version. The VPM is reviewed and reissued whenever Victoria Police makes changes to its policy or whenever there are changes to relevant legislation.

Adherence to operational processes is continuously monitored by PSO supervisors from the Transit Safety Division. Supervisors also receive regular feedback on PSO performance on specific tasks from other areas within Victoria Police, for example, intelligence areas provide feedback on the quality and usefulness of reports prepared by PSOs. Small changes, areas for improvement or reminders to adhere to processes are communicated to PSOs at their pre-shift briefing or through the Transit Safety Division's intranet.

3.5.2 Training

PSO training currently consists of:

- a 12-week training course at the Victoria Police Academy (initial training)

- a 12-week on-the-job mentoring and coaching program with an experienced PSO (coaching)

- skills and knowledge consolidation training courses after 12 and 24 months on the job.

In addition to this, PSOs undertake operational safety training every six months, in line with the requirements of all armed Victoria Police members. Operational safety training includes firearms use and safety refresher training, defensive tactics, tactical communication and training in relation to recent issues.

The PSO training regime has been consistently reviewed and modified since the start of the initiative.

Supervision

Supervision is a key aspect of PSO operations, especially as the PSO workforce is still relatively new in comparison with the rest of Victoria Police. New and inexperienced personnel rely heavily on effective supervision to not only ensure they are doing their job to Victoria Police's standards, but also to ensure they are safe and have access to support in critical situations.

Currently, PSOs are supervised by a Transit Safety Division sergeant, with one sergeant having responsibility for supervising four or five PSO teams.

Retaining adequate levels of supervision for PSOs without impacting on police capability is likely to be an ongoing issue. The 1700/940 Project, detailed in Figure 3E, introduced more than 2 600 new personnel into Victoria Police over a four-year period from 2011–15, creating strain across the organisation at the supervisory sergeant and senior sergeant levels. The unsociable work hours of these roles makes them unattractive for experienced Victoria Police members, creating problems with attracting and retaining skilled supervisory personnel.

Figure 3E

The 1700/940 Project

|

The 1700/940 Project was Victoria Police's project to support the introduction of 1 700 additional frontline police officers and 940 PSOs by November 2014. Like the PSO program, the addition of 1 700 new frontline officers and the deadline for their introduction were results of a government election commitment. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Victoria Police has undertaken several reviews of the supervision model for PSOs throughout the life of the program, to maximise efficiency and reduce the burden on the organisation, while still providing PSOs with the supervision they require. PSOs were originally planned to be managed and supervised by the Transit Safety Division for the first two years of the program, after which this responsibility would be shifted to regional commands. However, a May 2015 review recommended retaining the current supervision model, as the regional commands' capability to conduct their normal duties would be adversely impacted by the additional burden of PSO supervision.

3.6 PSOs and other safety and security personnel

PSOs present a challenge for Victoria Police operations, in that, while they are part of Victoria Police, there are legislative and policy constraints that prevent Victoria Police deploying and tasking them in the same manner as other police members.

Victoria Police has managed this challenge and has successfully integrated PSOs within the organisation. The level of integration between PSOs, Victoria Police and other safety and security initiatives has been sufficient to support effective PSO operations.

PSOs mostly operate separately and independently from non-police personal safety and security personnel, however, interactions necessarily occur. PSOs operational processes require them to check in with other personnel at stations, including authorised officers (AO), customer service personnel and stationmasters, to get updates on relevant situations. The check in also informs these staff of the PSO presence, should they require assistance.

Photograph courtesy of Public Transport Victoria.

Apart from specific, planned joint operations and joint training exercises, the deployment of non-police personal safety and security personnel is not influenced by PSO deployments. This is because PSOs have a specific function and cannot carry out the functions of other personnel. For example, AOs routinely operate on the same train platform as PSOs. The train operator advised this was because AOs are primarily tasked with preventing fare evasion and are deployed according to the train operator's assessment of levels of fare evasion. While PSOs have the power to check tickets, preventing fare evasion is not one of their main roles, making a concurrent AO presence necessary at times.

If PSOs are in the immediate vicinity when an incident occurs, they will assist other personnel, but there is no direct radio communications channel between PSOs and AOs or customer service staff. If PSOs are not nearby to help, AOs and customer service staff contact 000 to request police assistance. This situation may seem counterintuitive, but it is justified on the basis that the role of PSOs and their activities are managed by Victoria Police.

Routing requests for assistance through 000 enables Victoria Police to despatch the most appropriate resource—transit police, a local Victoria Police patrol, or several patrols—as the situation warrants. PSOs' powers are more limited than other police members, which can limit their ability to assist during an incident. For example, PSOs cannot usually take custody of a person arrested by an AO. Despatching other Victoria Police personnel to assist with an incident also enables PSOs to maintain a visible presence at the station.

Establishing direct radio communications between PSOs and AOs or customer service staff is unnecessary and would potentially undermine Victoria Police command and control procedures and task prioritisation.

3.7 Cross-agency coordination

Cross-agency coordination on personal safety and security is generally effective at both the operational and agency levels, but it is insufficient at a strategic level. Improved governance arrangements are required at all levels to maximise coordination and ensure that the available knowledge, resources and capabilities are efficiently and effectively used.

3.7.1 Operational information sharing

Operational information sharing between Victoria Police and the train operator is effective. There is direct and regular contact between the train operator's safety and security personnel and Victoria Police, to share information on incidents that have occurred on the train network. This enables Victoria Police to access information that can assist PSOs and transit police but that may fall short of the threshold for reporting a crime. The information gained through this channel assists with preparing daily briefings for PSOs.

3.7.2 Agency-level coordination

The Safe Travel Taskforce (STTF) is the main forum for agency-level coordination on personal safety and security. It comprises representatives from Victoria Police, Public Transport Victoria (PTV), DJR and public transport operators, as well as other relevant stakeholders. The taskforce had become defunct in mid-to-late 2008 as a result of changes in agency personnel and structure. Following a recommendation from VAGO's 2010 audit Personal Safety and Security on the Metropolitan Train System, the STTF was re-established and now meets quarterly to share information and updates on personal safety and security issues and initiatives and to discuss the coordination of activities.

The STTF currently lacks formal arrangements to guide intelligence-sharing, priority‑setting and joint operations-planning or to define the role of each member. This lack of formal arrangements renders its effectiveness contingent on the willingness of the personnel involved and increases the risk of the STTF once again becoming defunct as a result of changes to personnel or agency priorities.

A draft framework to formalise governance arrangements has been prepared but has not been finalised. The framework includes establishing an executive-level committee to oversee intelligence and information sharing. It also identifies priority action areas for STTF and executive-level committee focus. The draft framework is currently undergoing further development by PTV and Victoria Police, with implementation planned to occur in 2016.

3.7.3 Strategic coordination

Current strategic coordination between agencies on personal safety and security initiatives is lacking. There is no overarching strategy to guide agencies' decision‑making. The absence of an executive-level committee impedes the establishment of strategic cross‑agency initiatives to improve personal safety and security on the train network. While the STTF has filled some aspects of this role through its efforts to establish a framework for coordination on public transport personal safety, its focus is the sharing of information on individual agency initiatives, rather than driving decision-making and system improvements. Although PTV chairs a regular meeting of the chief executive officers of the transport operators, this does not focus on personal safety and security issues.

3.8 Night Network

The Night Network initiative is a 12-month trial of 24-hour public transport on Fridays and Saturdays throughout 2016, covering metropolitan trains, along with selected tram and bus routes. Ensuring commuter safety and security is a key aspect of the Night Network initiative, so the trial will involve PSOs.

In July 2015, government approved $47.9 million over four years for Victoria Police to recruit, train and deploy an additional 109 PSOs and 62 transit police for the Night Network trial. If the government does not choose to continue Night Network services beyond the 12-month trial period, PSO and transit police numbers will reduce to previous levels through attrition.

The Night Network trial will see a change in the usual deployment of PSOs. On Friday and Saturday nights, PSOs will be deployed to the 78 premium stations that will be operating during Night Network services, with capacity to provide deployments to four additional stations or to send extra personnel to further support major stations. Transit police will also be used to support Night Network, with extra patrols on trains and at stations.

The PSO deployment model that will be used for Night Network gives Victoria Police increased flexibility in deciding where to deploy PSOs. While it does not provide as much flexibility as the model considered and rejected by government in 2014, it nevertheless provides Victoria Police with the ability to deploy personnel in accordance with intelligence or operational priorities.

The Night Network proposal considered by government did not identify effectiveness measures for this initiative, but an evaluation of the trial is scheduled during June 2016, to determine whether to extend it into 2017. As yet, the criteria for assessing the Night Network trial have not been set. Until the problems identified in this audit concerning current KPIs and until weaknesses in available data are rectified, agencies may not be able to fully evaluate the effectiveness of the trial.