Ravenhall Correctional Centre: Rehabilitating and Reintegrating Prisoners – Part 2

Audit snapshot

Is Ravenhall Correctional Centre rehabilitating and reintegrating prisoners as intended?

Why we did this audit

Rehabilitating and reintegrating prisoners is critical for improving community safety and reducing the high cost of running prisons.

Ravenhall Correctional Centre (Ravenhall) is a private prison that offers a unique model for reducing reoffending. It has modern facilities and its own suite of rehabilitation programs. It also has a community-based reintegration centre, the Bridge Centre, that supports people up to 2 years after their release from prison.

However, our 2020 audit Ravenhall Prison: Rehabilitating and Reintegrating Prisoners found that the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS) did not know if Ravenhall's model was working. This was due to gaps and flaws in the performance and evaluation framework.

Five years later, we did this audit to see if Ravenhall is delivering on its targets to reduce reoffending.

Key background information

Note: The number of adult prisons includes the new Western Plains Correctional Centre, which opened on 30 June 2025.

Source: VAGO.

What we concluded

Despite its different rehabilitation and reintegration approach, Ravenhall's overall results for reducing reoffending fall short of performance targets and is similar to other Victorian adult male prisons. However, reoffending results are more promising for Ravenhall's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners.

Ravenhall may be missing some opportunities to rehabilitate prisoners because not all receive the programs they need.

DJCS’s key performance indicators for reintegration do not capture the full performance picture of the Bridge Centre’s reintegration services. But partial data shows the Bridge Centre often misses performance targets.

Video presentation

1. Our key findings

What we examined

Our audit followed 2 lines of inquiry:

1. Is Ravenhall delivering its rehabilitation and reintegration programs as required?

2. Is Ravenhall's rehabilitation and reintegration model contributing to reducing reoffending?

To answer these questions, we examined:

- the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS)

- The GEO Group Australia (GEO)

- ASGIP III Ravenhall Project Pty Ltd (Project Co).

Identifying what is working well

In our engagements we look for what is working well – not only areas for improvement.

Sharing positive outcomes allows other public agencies to learn from and adopt good practices. This is an important part of our commitment to better public services for Victorians.

Terms used in this report

Bail

Bail refers to when a person is charged with a criminal offence and is released from custody if they promise to attend court on their next court date. They may be required to follow rules during their release, including staying at home at certain times or reporting to a police station. People on bail are waiting for their case to be heard and have not been found guilty.

Remand

People on remand have been charged with a criminal offence and are held in custody, usually in a prison or a police cell, until their case has been heard. They have not been found guilty of their charge.

Reoffending

In the context of this audit, 'reoffending' refers to prisoners released from custody after serving a sentence, who return to prison under sentence within 2 years of release.

Background information

Ravenhall Correctional Centre (Ravenhall) is a privately operated medium-security men's prison in Melbourne's west. It opened in 2017 with a unique model for reducing reoffending. Ravenhall is operated by GEO through Project Co.

GEO offers rehabilitation and reintegration services that aim to address issues such as mental illness, drug abuse and unemployment. GEO calls its approach a ‘continuum of care’ because individuals can often access the same clinicians and caseworkers before and after their release from Ravenhall.

As of June 2025, Ravenhall had 965 inmates, making it the largest of Victoria's 16 adult prisons. It is one of only 3 private prisons in the state and the only one to receive bonuses if it meets DJCS's performance targets for reducing reoffending.

While GEO's contract with DJCS for operating Ravenhall runs until 2042, the state has the option to remove rehabilitation and reintegration programs from its scope.

Figure 1 shows the demographics of Ravenhall’s prison population.

Figure 1: Ravenhall’s prison population demographics

Note: These statistics are for prisoners who spent more than 90 days and/or 50 per cent of their time at Ravenhall between July 2022 and June 2025. The statistic '6% with intellectual disability' refers to prisoners identified in DJCS data as having intellectual disability. However, this data may not capture all cases.

*Offence type refers to the prisoner's 'most serious offence' recorded in DJCS data.

Source: VAGO.

The Bridge Centre is GEO's community-based reintegration facility in inner Melbourne. It provides support to former Ravenhall prisoners for up to 2 years after their release. This includes:

- access to the same GEO support staff they engaged with during their prison term

- case management and employment assistance

- opportunities for former prisoners' families to be involved in post-release support.

Our 2020 Ravenhall audit

In 2020, we tabled our report Ravenhall Prison: Rehabilitating and Reintegrating Prisoners. This audit found that Corrections Victoria and GEO did not have a fit-for-purpose performance and evaluation framework for Ravenhall. This meant the state could not learn if Ravenhall's unique model for rehabilitating and reintegrating prisoners was successful or not.

Cost of reoffending

Running prisons in Victoria is expensive. The cost per prisoner per day is $599.27. According to the Australian Government's Productivity Commission, reoffending accounts for more than half of this cost.

Although reducing reoffending would decrease prisons' high operational costs, the state's level of investment in rehabilitation and reintegration is comparatively low. Based on figures provided to us, DJCS spends 13.8 per cent of its public prison budgets on rehabilitation and reintegration. GEO told us it spends 17.5 per cent of its budget on this area. These figures may not be directly comparable because public and private prisons have different funding models and approaches to rehabilitation and reintegration.

Drivers of reoffending

In 2023–24, the rate of return to prison within 2 years in Victoria was 39.3 per cent.

Compared with the general population, people entering prison typically have significantly higher rates of:

- school dropout

- unemployment

- homelessness

- mental illness

- alcohol and other drug (AOD) abuse.

The challenges many people face when reintegrating into the community after release can be heightened by these issues.

After release, having a criminal record can worsen their already poor job and housing prospects.

Bail reforms

In March 2025, the Victorian Government passed bail reform legislation that:

- expands police powers to bring an arrested person directly to court rather than waiting for a bail test to determine the person's eligibility for bail

- makes it a criminal offence to commit an indictable offence while on bail for an indictable offence

- removes 'remand as a last resort' for youth offenders.

These changes may result in an increased need for prisoner places, adding strain to the system's existing resources. While it is too early to assess the impact of the current bail reforms, a 2025 Sentencing Advisory Council report on Victoria's prison population notes that the proportion of remand prisoners has increased over the last 2 decades. As at 30 June 2025, people on remand made up 39 per cent of Victoria's adult male prison population.

What we found

This section focuses on our key findings, which fall into 3 areas:

1. Ravenhall's reoffending rates are similar to other Victorian prisons, except for some more positive results for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners.

2. Ravenhall may be missing opportunities to rehabilitate prisoners because not all receive the programs they need.

3. Reintegration key performance indicators (KPIs) do not capture the full performance picture, but show missed targets.

The full list of our recommendations, including agency responses, is at the end of this section.

Consultation with agencies

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views. You can read their full responses in Appendix A.

You can read their full responses in Appendix A.

Key finding 1: Ravenhall's reoffending rates are similar to other Victorian prisons, except for some more positive results for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners

The results below are based on our independent analysis of DJCS prisoner data from July 2022 to June 2025. Reoffending rates are calculated on a 2-year cycle, meaning that 2024–25 rates refer to people who were released from prison in 2022–23.

Who is a ‘Ravenhall prisoner’?

Throughout this report, we compare prisoners who have been exposed to Ravenhall's rehabilitation and reintegration model with other prisoners. We use 2 different approaches to define Ravenhall prisoners:

- prisoners who were released from Ravenhall (but may not have spent most of their prison time at Ravenhall). Only prisoners who are released from Ravenhall can access Bridge Centre reintegration services

- prisoners who spent at least 90 days and/or 50 per cent of their prison time at Ravenhall.

You can read more about our audit scope and method in Appendix C.

2024–25 reoffending rates

The rate of reoffending for adult male prisoners who spent at least 90 days and/or at least 50 per cent of their jail time at Ravenhall was 37.4 per cent. In comparison the rate for adult male prisoners who did not meet either of those conditions was 36.9 per cent.

Working well: Reducing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander reoffending

In 2024–25, the reoffending rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult males who spent at least 90 days and/or 50 per cent of their prison time at Ravenhall was 34.6 per cent compared with 42.8 per cent for those who did not.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding we made one recommendation to DJCS about evaluating Ravenhall's rehabilitation and reintegration programs, including its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rehabilitation approach, to explore what is working well and if it could be scaled up to other prisons.

Key finding 2: Ravenhall may be missing opportunities to rehabilitate prisoners because not all receive the programs they need

GEO designs and offers rehabilitation programs relevant to Ravenhall prisoners' needs, such as addressing alcohol, drug and offending behaviour issues. Ravenhall also delivers vocational training courses through its partner Bendigo Kangan Institute. The level of coverage is limited compared with the overall prison population and waitlists are more than 3 months long. Program participation is voluntary and some prisoners may be unable to participate in programs due to mental illness or intellectual disability.

Program delivery matches DJCS's targets, but waitlists are long

More than 85 per cent of enrolled prisoners go on to complete their programs in line with DJCS's contractual target. This means program dropout rates are low. However, various factors suggest Ravenhall is not fully meeting prisoners’ needs or maximising rehabilitation opportunities. These factors include:

- long waitlists to start programs

- limited access to education and vocational training opportunities.

Most prisoners did not participate in any programs between January and June 2025

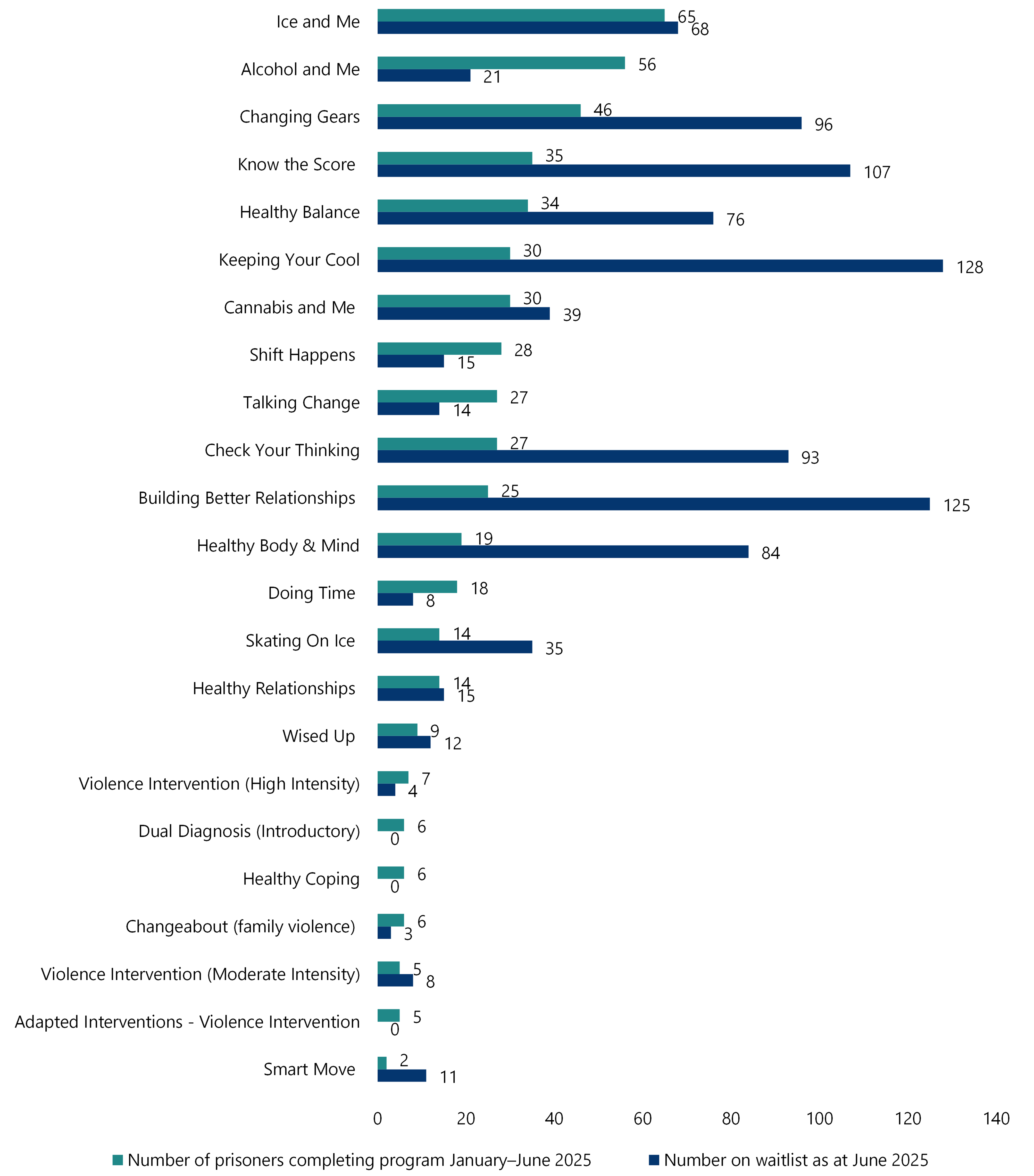

Between January and June 2025, Ravenhall delivered 23 different group rehabilitation programs targeting AOD issues and offending behaviour. We found that during this period:

- 328 unique prisoners completed 514 rehabilitation programs between them (compared with a total prison population of 965 prisoners as at June 2025)

- 96 unique prisoners refused 108 program places offered to them.

However, as at June 2025, Ravenhall prisoners were waiting for a total of 962 rehabilitation program places, with an average wait time of 111 days.

Key issue: Offering rehabilitation program places to match needs

When prisoners arrive at Ravenhall, they receive a rehabilitation and reintegration needs assessment. Staff can add prisoners to program waitlists at that time, or prisoners can self-refer to programs using tablets in their cell that are connected to the prison intranet.

Caseworkers also regularly meet with prisoners to encourage them to work in prison industries, do exercise, do programs and remain in regular contact with family and friends.

Completing rehabilitation programs is voluntary unless it is linked to a prisoner's parole requirements. However, we did not see any evidence of Ravenhall:

- prioritising high-needs prisoners on waitlists for offending behaviour or AOD programs

- systematically following up to make sure programs were offered to prisoners in a timely manner.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding we made one recommendation to DJCS about aligning its rehabilitation program and vocational training course delivery to prisoner needs.

Key finding 3: Reintegration KPIs do not capture the full performance picture, but show missed targets

Reintegration KPIs do not capture the full picture of the Bridge Centre’s performance

DJCS’s KPIs do not allow it to effectively capture the full picture of the Bridge Centre's performance in providing reintegration services. This is because the reintegration KPI has limitations in its design and only measures:

- a small number of former prisoners who consent to being monitored after release

- 2-month post-release performance targets, even though the reintegration services are provided for up to 2 years.

This limited data shows that the Bridge Centre’s results often fall short of DJCS's 2-month post-release performance targets.

However, former Ravenhall prisoners do access the Bridge Centre's reintegration services, especially to find housing. Our review of a sample of prisoner files identified instances where the Bridge Centre's intensive case management approach met former prisoners' reintegration needs over a longer timeframe.

DJCS independently monitors performance targets but has not evaluated Ravenhall

DJCS has a rigorous procedure for independently verifying private prison operators' performance. DJCS staff access Ravenhall prisoners' files and reintegration records to independently check KPI results. This means DJCS does not pay performance bonuses to GEO without carefully crosschecking that Ravenhall met the relevant target.

While DJCS has commissioned independent evaluations of rehabilitation and reintegration programs for Victoria's public prisons in recent years, it has not done so for Ravenhall.

This means that DJCS does not know if any of Ravenhall's unique programs are successful. The department may therefore be:

- continuing to invest public funds in ineffective programs

- missing opportunities to scale up successful programs to other prisons.

Addressing this finding

To address this finding we made 2 recommendations to DJCS about:

- monitoring Ravenhall's overall service delivery of reintegration services

- evaluating Ravenhall to assess which programs should be continued and/or expanded.

See the next section for the complete list of our recommendations, including agency responses.

2. Our recommendations

We made 3 recommendations to address our findings. The relevant agencies have accepted the recommendations in principle.

| Agency response(s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

Department of Justice and Community Safety

| 1

| Evaluate Ravenhall Correctional Centre’s rehabilitation and reintegration programs, including its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rehabilitation approach, to identify possible success factors to scale up to other prisons (see Section 4).

| Accepted in principle

| |

2

| Establish a mechanism to accurately measure and monitor the delivery of reintegration services (see Section 5).

| Accepted in principle

| ||

3

| Work with The GEO Group Australia to strategically align program delivery with prisoner needs, including programs for:

| Accepted in principle

| ||

3. Reducing reoffending

Ravenhall does not perform any better than other Victorian adult male prisons on reducing reoffending, except for some encouraging results for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners.

Due to its forensic mental health facilities, Ravenhall receives prisoners with high psychiatric needs, which may increase the challenge of meeting its targets for reducing reoffending.

Covered in this section:

- Ravenhall's reoffending rates are no better than other Victorian adult male prisons

- Challenging prisoner profiles make it harder to hit targets

- Looking forward: preliminary trends in reoffending rates

Ravenhall's reoffending rates are no better than other Victorian adult male prisons

Targets for reducing reoffending

DJCS's KPI 16 for Ravenhall defines reoffending as returning to prison within 2 years of release. For GEO to receive a performance bonus from DJCS for reducing reoffending, the contract requires Ravenhall to have a lower reoffending rate. Compared with other Victorian adult male prisons, the reoffending rate must be:

- at least 12 per cent lower overall

- at least 14 per cent lower for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners.

Results on reducing reoffending

Our independent analysis of DJCS data shows that overall, Ravenhall is not meeting its reoffending targets.

Rather than detecting a positive difference, we found that Ravenhall's reoffending rates are slightly worse than the rest of adult male prisons. This is the case both for prisoners released from Ravenhall and for prisoners who spent at least 90 days and/or 50 per cent of their time there.

As Figure 2 shows, in 2024–25:

- the reoffending rate for prisoners released from Ravenhall was 38.3 per cent, which is slightly higher than the rate of 36.6 per cent for those released from other adult male prisons

- the reoffending rate for prisoners who spent at least 90 days and/or 50 per cent of their time at Ravenhall was 37.4 per cent, compared with 36.9 per cent for those who spent this amount of time at other adult male prisons.

Figure 2 compares Ravenhall prisoners (defined by prison of release or time spent) with other adult male prisoners.

Figure 2: Percentage of sentenced prisoners released in 2022–23 who returned to prison and were re-sentenced within 2 years

Source: VAGO analysis of DJCS dataset.

Reoffending rates for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island prisoners

In the same reporting period, Ravenhall succeeded in delivering lower reoffending rates for its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners.

As Figure 3 shows, in 2024–25:

- the reoffending rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners released from Ravenhall was 41.2 per cent. This is slightly lower than the rate of 42.8 per cent for those released from other adult male prisons but still misses the DJCS performance target of 14 per cent lower

- the reoffending rate for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners who spent at least 90 days and/or at least 50 per cent of their time at Ravenhall was 34.6 per cent compared with 42.8 per cent for those who spent this amount of time at other adult male prisons. DJCS calculates the KPI result as a percentage of the comparison rate. This means that for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island prisoners who spent at least 90 days and/or 50 per cent of their time at Ravenhall, the reoffending rate is 19 per cent lower, which is better than the 14 per cent target.

Figure 3 compares Ravenhall’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners (defined by prison of release or time spent) with other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adult male prisoners.

Figure 3: Percentage of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners released from Ravenhall and other male prisons in 2022–23 who returned to prison and were re-sentenced within 2 years

Source: VAGO analysis of DJCS dataset.

Challenging prisoner profiles make it harder to hit targets

Prisoners’ psychiatric risk profiles

Due to its specialist facilities, Ravenhall regularly receives some prisoners who are more challenging to rehabilitate and reintegrate. For example, prisoners with serious mental health needs may be unable to safely participate in group rehabilitation programs.

As Ravenhall has 75 forensic mental health beds, it is one of only a few prisons in Victoria equipped to receive the most acute psychiatric cases.

| Up until the end of June 2025, Ravenhall … | was one of only … | that can receive … | which is the category with the … |

|---|---|---|---|

| along with Melbourne Assessment Prison | 2 prisons | P1 prisoners | highest psychiatric risk rating. |

| along with Melbourne Assessment Prison, Metropolitan Remand Centre and Port Phillip Prison | 4 prisons | P2 prisoners | second-highest psychiatric risk rating. |

Port Phillip Prison is scheduled to close by the end of 2025, but Western Plains Correctional Centre opened on 30 June 2025 and can receive P2-rated prisoners.

According to a GEO submission to DJCS on reviewing KPIs, as at 31 December 2024, of Ravenhall’s total prison population:

- 4 per cent had the highest psychiatric risk rating (P1)

- 19 per cent had the second-highest psychiatric risk rating (P2)

- 48 per cent had a moderate psychiatric risk rating (P3)

- 29 per cent had no P-rating (no identified psychiatric risk rating).

Figure 4 shows the psychiatric risk profile of Ravenhall prisoners as at December 2024.

Figure 4: Ravenhall prisoners' psychiatric risk profile as at 31 December 2024

Source: VAGO, based on GEO analysis.

While P1 and P2 prisoners make up almost a quarter of Ravenhall’s total population based on the above figures, GEO says that its rehabilitation and reintegration model is best suited to prisoners with a P3 rating or no P-rating.

As Ravenhall is one of only a few Victorian prisons that receives the highest-risk psychiatric cases, this may be a contributing factor for it falling short of meeting targets to reduce reoffending.

However, DJCS told us that as the 75 forensic mental health beds were part of Ravenhall's original contract, it expected GEO would also cater for the highest-risk psychiatric cases. In March 2025, GEO submitted a formal request to DJCS to lower its contractual targets for reducing reoffending, arguing that the percentage of high-risk psychiatric cases it receives has significantly increased.

DJCS said it would support further work to strengthen GEO's rehabilitation and reintegration model to serve this population.

Looking forward: preliminary trends in reoffending rates

Future trends

Trends in reoffending rates for prisoners released from Victorian prisons in 2023–24 and 2024–25 are still emerging. This is due to both the time prisoners take to reoffend and the time it takes for the courts to sentence them.

DJCS measures the reoffending rate as the percentage of prisoners who return to prison and are re-sentenced within 2 years of release. To take the sentencing time lag into account, we also included prisoners who returned to prison on remand in our analysis.

Based on early indications, Ravenhall may be reducing reoffending compared with other adult male prisons:

- Out of prisoners released from Ravenhall in 2024–25, the rate of return to prison to date is lower.

- Out of those who spent at least 50 per cent of their prison time and/or 90 days in Ravenhall, the rate of return to prison so far is lower for those released in both 2023–24 and 2024–25. Notably, the difference between the percentage of prisoners who have been re-sentenced so far from those released in 2023–24 (20.8 per cent for Ravenhall prisoners compared with 29.6 per cent for other adult male prisons) appears to be an encouraging preliminary trend. However, these are very early indications and final results could look significantly different at the end of the 2 year reporting period.

Future trends – detailed data

Figure 5 shows the preliminary data on reoffending for prisoners released from Ravenhall compared with those released from other adult male prisons. As reoffending is measured over a 2 year timeframe, the reporting period for 2022–23 is now complete (pending DJCS releasing official results at the end of 2025).

We have provided the 2022–23 data for comparison with the trends emerging in 2023–24 and 2024–25.

Figure 5: Preliminary data on remand and re-sentencing rates for prisoners released from Ravenhall compared with other adult male prisons

Note: ‘Any return’ means a return to prison as either a sentenced or remand prisoner.

Source: VAGO analysis of DJCS dataset.

Figure 6 compares preliminary data on reoffending for prisoners who spent 50 per cent of their time and/or more than 90 days at Ravenhall compared with prisoners who spent this amount of time at other adult male prisons.

Figure 6: Preliminary data on remand and re-sentencing rates for prisoners who have spent 50 per cent of their time or more than 90 days at Ravenhall compared with other adult male prisons

Note: 'Any return’ means a return to prison as either a sentenced or remand prisoner. As reoffending is measured over a 2-year timeframe, the 2022–23 reporting period is complete (with official results pending DJCS data validation at the end of 2025) while the 2023–24 and 2024–25 data reflects preliminary trends.

Source: VAGO analysis of DJCS dataset.

4. Meeting prisoners' rehabilitation needs

GEO designs and offers rehabilitation programs relevant to Ravenhall prisoners' needs, such as addressing AOD and offending behaviour issues.

More than 85 per cent of enrolled prisoners go on to complete their programs in line with DJCS's contractual target. This means that program dropout rates are low. However, long waitlists to start programs and limited vocational training options suggest that Ravenhall is not fully meeting prisoners’ needs or maximising rehabilitation opportunities.

During our site visit, we observed that Ravenhall has modern facilities, such as a cultural centre for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs and a family-friendly space for parenting programs. However, no data is available to assess their effectiveness.

Covered in this section:

- Rehabilitation programs do not reach the majority of prisoners

- Few prisoners have completed formal vocational training qualifications

- Other programs and facilities at Ravenhall may support rehabilitation, but they lack feedback and performance data

- Prisoner feedback on rehabilitation programs targeting AOD issues is mainly positive

- Prisoner case studies show mixed levels of engagement with rehabilitation programs

Rehabilitation programs do not reach the majority of prisoners

Program design

GEO has developed a comprehensive suite of rehabilitation programs to address Ravenhall prisoners' needs.

These programs include:

- AOD rehabilitation programs, such as Skating on Ice (for methamphetamine users), Cannabis and Me and Alcohol and Me

- behaviour change programs, such as Keeping Your Cool (anger management) and Building Better Relationships.

These programs include a range of resources, such as facilitator manuals, participant work sheets, videos and activity cards.

At the end of each program, the clinician drafts a report on each participant's level of engagement and recommends any further activities suitable for the prisoner's needs and risk profile.

Program delivery targets

At Ravenhall, GEO implements both its own rehabilitation programs and the Victorian Government's according to a schedule agreed with DJCS. Victorian Government programs include the family violence program, Changeabout, and the Violence Intervention programs.

Ravenhall’s contractual service delivery targets are to deliver 100 per cent of planned AOD and offending behaviour programs with an 85 per cent prisoner completion rate or higher.

GEO met these targets for 11 of the 12 quarters within our audit scope, except for January to March 2024 when Ravenhall implemented 97 per cent of its planned rehabilitation programs.

Program scheduling and prisoner participation

It is unclear how GEO:

- adapts the type and frequency of rehabilitation programs it offers

- aligns the number of program places available to match prisoners' needs.

DJCS told us it reviews Ravenhall's rehabilitation program schedules to make sure the number of programs it delivers does not drop significantly below previous years or what is reasonable considering staff resources.

For Ravenhall’s January to June 2025 rehabilitation program schedule, DJCS stressed the importance of offering programs targeting family violence and sexual offending to match prisoners' profiles.

We found that Ravenhall's recent AOD and offending behaviour rehabilitation programs only reach a limited proportion of prisoners.

For example, GEO's April 2025 reporting to DJCS shows up to 81 prisoners participating in these programs during that month out of the prison's population of 962 prisoners at that time. Even if no prisoners are completing more than one program concurrently, this would mean that less than 10 per cent of the prison's population participated in these rehabilitation programs during that month.

Some prisoners may be unable to participate in mainstream group rehabilitation programs due to high psychiatric risk ratings or other factors, such as intellectual disability. However, due to data limitations we could not identify the precise number of people who are unable to participate.

Program completions versus waitlists

Between January and June 2025, Ravenhall delivered 23 different group rehabilitation programs targeting AOD issues and offending behaviour. We found that during this period:

- a total of 328 unique prisoners completed 514 rehabilitation programs between them

- a total of 96 unique prisoners refused 108 program slots offered to them.

However, as at June 2025, Ravenhall prisoners were waiting for a total of 962 rehabilitation program places, with an average wait time of 111 days.

This data shows that due to both wait times and prisoners refusing places, Ravenhall’s rehabilitation programs only reached a minority of the prison population between January and June 2025.

We reviewed a sample of prisoner files. We found examples of individuals with particular profiles, such as family violence or sexual offending and sentences of over 6 months, who were not offered and did not complete the relevant programs.

We also noted that in some cases involving prisoners from migrant backgrounds, their level of English was considered insufficient for program participation. There are no alternatives in other common languages spoken by prisoners. GEO told us it is looking at ways to improve the volume and timeliness of its programs for high risk and high-needs prisoners.

Figure 7 compares the number of program completions for January to June 2025 with the June waitlist figures. It shows that waitlists for some programs are significantly longer than others, with the shortest waitlists tending to be for short (6-hour) courses designed for remand prisoners. These include Alcohol and Me, Ice and Me, and Cannabis and Me.

Figure 7: Number of prisoner completions and waitlists for rehabilitation programs offered in 2025

Source: VAGO, based on GEO data.

Limitations with waitlist data

There are several potential limitations with Ravenhall's rehabilitation program waitlist data. These limitations reduce Ravenhall’s ability to effectively and efficiently deliver needs-based programming.

Ravenhall reintegration staff told us that waitlist figures may be higher than the actual demand. This is partly because rehabilitation program participation is voluntary.

We observed that the limitations in GEO's prisoner management system do not allow Ravenhall staff to change a prisoner's position on a waitlist when they choose to postpone their participation to a later session.

On the other hand, waitlists for the Changeabout (family violence) and Violence Intervention programs may be lower than actual demand. This is because a prisoner must have an additional assessment by a clinician to be put on the waitlist for these DJCS-designed targeted programs.

In December 2024, there were several clinical assessments outstanding for sexual and violent offenders at Ravenhall.

Few prisoners have completed formal vocational training qualifications

Limited access to formal vocational training qualifications

Ravenhall prisoners have limited access to formal vocational education training qualifications, potentially limiting their future employment options.

Between June 2022 and June 2025, individual Ravenhall prisoners made 6 separate complaints to the Victorian Ombudsman alleging a lack of support to access educational courses, such as the Tertiary Preparation Program. In response, GEO explained to the Victorian Ombudsman that the estimated wait time to enter the Tertiary Preparation Program is 2 years because there is only one staff member available to supervise prisoners' distance education courses.

Since 2023, 44 Ravenhall prisoners have gained 49 formal TAFE qualifications between them. Even without accounting for any prisoner turnover during this period, this is less than 5 per cent of Ravenhall's current population. There is one TAFE provider at Ravenhall (Bendigo Kangan Institute) and prisoners have been able to gain only 3 types of full qualifications.

| Based on GEO’s records … | have/has completed … |

|---|---|

| 28 prisoners | a Certificate II in Engineering |

| 20 prisoners | a Certificate III in Cleaning Operations, including 6 prisoners who also completed a Certificate II in Engineering |

| one prisoner | a Certificate I in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Cultural Arts. |

Certificate II in Engineering

DJCS told us that the Certificate II in Engineering (focused on steel work) is a useful vocational training qualification. This is because the department has identified welding as a skills shortage area where gaining a relevant qualification is likely to increase employment prospects.

The Australian Government's occupation shortage list confirms this assessment, with multiple types of welding rated as skills gaps in Victoria.

Certificate III in Cleaning Operations

Public prisons also offer the Certificate III in Cleaning Operations. Prisoners working inside as cleaners reportedly make up 20 per cent of enrolments.

DJCS told us that prisoners who complete the cleaning qualification in public prisons can then transition to studying business units to prepare them for setting up their own small business after release.

No prisoners have completed business qualifications while at Ravenhall. It is unclear if the cleaning course matches their needs and maximises their employment prospects.

For example, according to a Victorian Government online resource for jobseekers with a criminal record, cleaning jobs often require a police check. This means it may be harder for a former prisoner to find work as a cleaner.

The Australian Government also does not list cleaning as a shortage occupation in Victoria or any other state.

Incomplete qualifications

In 2024–25, Bendigo Kangan Institute also delivered courses from 9 other certificate-level qualifications at Ravenhall. But no prisoners had gained the formal qualification in these areas by June 2025. Certificate-level qualifications take at least 6 months to complete and most prisoners do not stay at Ravenhall for that length of time.

Prisoners have the option to transfer their completed units along with them if they are moved to another prison. However, there are no similar direct pathways for completing qualifications after release, despite Bendigo Kangan Institute having a network of community-based TAFEs.

GEO's Bridge Centre can support former Ravenhall prisoners to enrol and continue their vocational training in the community. However, from July 2022 to June 2025, there are no documented cases of people completing qualifications they started at Ravenhall after their release.

Language, literacy and numeracy courses

The need for basic language, literacy and numeracy education among Victorian prisoners is high.

DJCS data for people entering prison in 2021–22 indicates that:

- 65 per cent had not completed high school

- 58 per cent lack the skills required to handle their day-to-day affairs without assistance, such as claiming Centrelink benefits.

While no Ravenhall prisoners have completed a full TAFE certificate in language, literacy or numeracy, Bendigo Kangan Institute delivered a number of course units at Ravenhall between January 2023 and June 2025.

This includes:

- General Education for Adults, in which a total of 415 students completed 687 course units

- English as an Additional Language, in which a total of 111 prisoners completed 194 course units.

Other programs and facilities at Ravenhall may support rehabilitation, but they lack feedback and performance data

Prison environment

As well as the actual programs, Ravenhall's physical environment was designed to promote rehabilitation.

Ravenhall has modern, architecturally designed buildings, ample green space and well-equipped facilities, such as a gym and a library.

Comparing Ravenhall with Victoria's older prisons, such as Port Phillip Prison, is beyond the scope of this audit. However, we note Ravenhall's more modern facilities may better enable rehabilitation work.

During our July 2025 site visit, we observed clean, bright classrooms with large screens available for rehabilitation program delivery.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs

During our July 2025 site visit, we observed that Ravenhall has a well-equipped cultural centre. It has a team of 5 Aboriginal wellbeing officers who manage rehabilitation and cultural programs.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners are given a brochure with information on programs and how to enrol.

Regular activities (run at least monthly) include:

- traditional smoking ceremonies

- an Indigenous art program (in addition to The Torch program, which is run in all Victorian prisons, with 259 prisoners participating in Ravenhall between January to June 2025)

- Koorie youth council (for prisoners under 25)

- men's business yarning circles

- peer-led didgeridoo classes.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners at Ravenhall can also enrol in the following programs:

| The … | involves … | and in January to June 2025, a total of … |

|---|---|---|

| Dardi Munwurro Men's Healing and Behaviour Change program | a 3-day intensive program with 2 additional days of follow-up | 36 prisoners completed this program |

| Yarn Bark cultural immersion program | 7 sessions of men's business workshops focused on traditional crafts | 36 prisoners participated in this program. |

| Balit Yirramboi program | individual and group counselling sessions for substance abuse | 46 prisoners participated in this program. |

| Wadamba Prison to Work program | a weekly program for remand prisoners | 59 prisoners participated in this program. |

| Own Your Decisions program by retired AFL footballer Travis Varcoe | 4-day small-group intensive life coaching, offered quarterly | 63 prisoners participated in this program. |

Bendigo Kangan Institute also offers:

- Certificate I and II in Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Cultural Arts

- the Mumgu Dhal program, which is a weekly community course currently focused on cooking skills.

In summary, Ravenhall offers good facilities, a dedicated wellbeing team and a wide range of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rehabilitation and cultural programs.

These resources, staff and programs may be contributing to Ravenhall's above-average results in reducing reoffending among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners. However, we have not seen any direct evidence to confirm their effectiveness. This is because:

- Ravenhall's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rehabilitation programs are not included in DJCS's KPIs

- GEO has not yet completed internal evaluations on these programs.

Family programs

For all prisoners, Ravenhall has a range of facilities and programs designed to strengthen family relationships and parenting skills. These include:

- a child-friendly zone in the visiting area to allow prisoners to play with their children (in some cases supervised by child protection services). We saw these facilities during our site visit and observed that they were clean and welcoming, with a colourful sea life theme

- a team of GEO family practitioners who can advise prisoners on child protection and family law issues and support them to communicate with their families and rebuild relationships. Between January and June 2025, a total of 183 unique prisoners received support for family and child protection issues and 16 participated in the Family Connect program

- a group-based Triple P Positive Parenting Program to improve fathers' communication with their children and their understanding of child development. Twelve prisoners participated between January and June 2025

- Read Along with Dad program where staff help fathers to record up to one children's book per month and send it as an audio file to the child's carer. A total of 7 prisoners participated in this program between January and June 2025.

In all prisoner files we reviewed, we noted that rehabilitation staff encouraged prisoners to keep in touch with friends and family via phone, video calls and visits. Staff also supported prisoners to set goals related to improving family relationships.

These family programs regularly feature in GEO's quarterly reports to DJCS as a key part of Ravenhall's rehabilitation approach. However, similarly to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander programs, DJCS does not have distinct performance measures for family programs and GEO has not collected any participant feedback on these programs at Ravenhall.

Prisoner feedback on rehabilitation programs targeting AOD issues is mainly positive

Feedback data on rehabilitation programs

GEO collects feedback on its suite of AOD rehabilitation programs from both Ravenhall prisoners and facilitators.

One potential limitation of this data is that as prisoners depend on GEO for their daily needs and facilitators for their employment, some may be hesitant to express negative feedback. To minimise this risk of bias, GEO‘s feedback form tells participants and facilitators that their honest feedback will help GEO to understand if this program was effective and that it will remain confidential.

GEO collected a total of 537 prisoner feedback surveys at Ravenhall between July 2022 and July 2024, with sample sizes differing between programs. Of the prisoners who gave feedback:

- 93 per cent agreed or strongly agreed they would recommend the AOD treatment program they attended to other prisoners

- the most positive rating was for the Skating on Ice methamphetamine treatment program, where all participants agreed they would recommend the program to others

- the lowest rating was for Cannabis and Me, but 89 per cent of prisoners still said they would recommend the program.

Figure 8 shows prisoner feedback results.

Figure 8: Percentage of participants who said they would recommend the program to other prisoners

Note: RRHR stands for Release Related Harm Reduction. This program aims to prevent drug overdoses following release from prison. Numbers in brackets represent the overall survey sample size.

Source: VAGO, based on analysis of GEO’s research and evaluation feedback survey dataset collected at Ravenhall between July 2022 and July 2024.

Feedback themes from participants

In open-text responses, prisoners' reasons for giving positive feedback included appreciation for the facilitators. One said, ‘I felt good to know that there are people who care, and who are here to help and educate me about how bad it is … such as Dopeman affecting our brains, and how bad the chemicals are’.

While negative feedback was minimal, a few prisoners disliked the group treatment setting. For example, one prisoner said, ‘I feel the clinicians are easy to interact with but others in the program make it easy to be distracted’.

Prisoners’ motivation to change

After completing their rehabilitation program, GEO's research and evaluation team asked prisoners if they felt motivated to change.

Several prisoners stated their desire to change. These statements included:

- ‘It was good to refresh my memory and understanding that I need to get back to the man and father I know I can be. That I am better without ice, and I know what it can destroy and what I can lose’.

- ‘I have listened to how strategies work for others and am willing to give them a go’.

However, some prisoners said their program was simply too short to make any meaningful impact. Programs for remand prisoners, such as Alcohol and Me, Ice and Me and Cannabis and Me, have 2 sessions of 3 hours each.

The percentage of participants saying they would reduce or quit alcohol or drugs was highest for the Alcohol and Me program at 91 per cent, and lowest at 73 per cent for Know the Score. This program covers general drug issues rather than a specific substance.

Figure 9 shows prisoner responses in relation to changing their AOD use after attending specific programs.

Figure 9: Percentage of prisoners who report they feel motivated to change their AOD use after the program

Note: GEO did not collect feedback data from Release Related Harm Reduction participants for this question because it is not applicable to the program content. Numbers in brackets represent the overall survey sample size.

Source: VAGO, based on analysis of GEO’s research and evaluation feedback survey dataset collected at Ravenhall between July 2022 and July 2024.

These results should be interpreted with caution because they reflect a point-in-time snapshot of prisoner attitudes, rather than their subsequent behaviours. The results do not allow for differences in sample sizes or prisoner cohorts, such as:

- remand versus sentenced prisoners

- those with more complex drug treatment needs.

Prisoner case studies show mixed levels of engagement with rehabilitation programs

Case management system

GEO's prisoner file management system, Gateway, is comprehensive and retains records of existing and former prisoners. To examine cases at both extremes of the reoffending spectrum, our sample of files covered:

- 37 Ravenhall prisoners who had reoffended the most quickly (all within 3 months of release)

- 29 prisoners released from Ravenhall who had not reoffended by June 2025.

| We found all 66 files … | This enables GEO to … |

|---|---|

| identified the prisoner's goals during their time at Ravenhall, with all prisoners setting multiple goals. | track, monitor and assess the prisoner’s rehabilitation and reintegration progress as they align with their identified goals. |

had comprehensive file notes that ranged from:

| have a broad view of the prisoner's time at Ravenhall and track the prisoner's activity. |

| include a basic overview of the prisoner, including their religion, any dietary requirements and if they require a language interpreter. | track and monitor a prisoner's individual needs. |

| recorded the rehabilitation and reintegration programs that the prisoner has participated in, not been approved for, and did not complete. | track a prisoner's participation in programs. |

Gaps in record keeping

Each tab in the prisoner files we sampled contained extensive information that allowed us to track the prisoner's time in Ravenhall. However, we noted some gaps in record keeping.

Thirteen files did not record the outcome of GEO's assessment of the prisoner's risk of reoffending despite this being a tab in each file. GEO advised us that this may happen for different reasons. This includes the prisoner being on remand or not eligible for an assessment because of insufficient sentence length.

However, of the 13 files we found with a blank reoffending risk tab, GEO did not record a justification for not assessing this.

There was also an instance where another prisoner's file notes had been included in the wrong prisoner file.

Selecting and using case studies in this report

We selected a total of 66 cases of prisoners who had not reoffended as well as cases of prisoners who had reoffended quickly. In this approach, the purpose is not to make statistically significant findings based on our case sample. Rather, it examines cases at both ends of the spectrum to see if any qualitative themes emerge. These themes can either be in terms of best practice or missed opportunities for rehabilitation and reintegration.

The drivers of reoffending are complex. The following 3 case studies show that if a prisoner participates in rehabilitation programs, this does not always guarantee they will stay out of prison.

These case studies provide examples of:

- prisoners' varying levels of participation in different programs in practice

- Ravenhall staff sometimes making extensive efforts to support prisoners both before and after release.

Case study 1: Prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration journey

Example of a prisoner who received support, including for AOD issues, and who did not reoffend

Alex* has served 3 terms in prison, with his latest being a 2-month stint in 2023. From his first prison term, Alex was rated as having a high risk of reoffending. While he told Ravenhall staff he was not interested in education or vocational training courses, he did complete a number of life skills programs, including a Managing Money course. Ravenhall staff also supported Alex with information on accessing the Disability Support Pension.

After Alex's release in late 2023, he accessed Bridge Centre services 19 times over a 3-month period, each time for AOD-related assistance. Since his release, Alex has not returned to prison.

Note: *Name has been changed for data protection purposes.

Source: VAGO, based on review of a sample of prisoner files.

Case study 2: Prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration journey

Example of a prisoner who did not participate in programs but received housing support and did not reoffend

Steven* arrived at Ravenhall in early 2023 as a sentenced prisoner. This was his 24th time in prison. He later returned in early 2024 as a remand prisoner. During his assessment for this term, Steven told staff during his induction that although he had good reading and writing skills, he was not interested in educational programs while at Ravenhall.

When Steven left Ravenhall in 2024, he accessed Bridge Centre services 5 times, all for housing or independent living reasons. During this contact, the Bridge Centre was able to successfully extend Steven's stay at assisted housing. He has not returned to prison.

Note: *Name has been changed for data protection purposes.

Source: VAGO, based on review of a sample of prisoner files.

Case study 3: Prisoner rehabilitation and reintegration journey

Example of a prisoner who reoffended despite participating in rehabilitation programs for AOD issues as well as an employment program

Craig* was at Ravenhall from mid-2023 until early 2025. He spent the first year as a remand prisoner and then another 6 months after he was sentenced for assault and other charges. Due to a family violence intervention order, he was only allowed to have video calls with his young son.

However, despite this background, Ravenhall did not offer Craig a place in any parenting skills courses or targeted programs to address family violence or other violent offending. Staff did not assess him for either type of programming until 3 to 4 months after he was sentenced and he never made it off the waitlist.

It was Craig's first time in prison, and he told Ravenhall staff that he was under the influence of drugs when he committed his crimes. To address these issues, he completed the Ice and Me, Alcohol and Me and Know the Score rehabilitation programs.

Reintegration staff also referred Craig to the YMCA's employment program for post-release support. During an appointment one month after his release, Craig ‘reported being job ready and excited to work’. But 11 days later, he reoffended and returned to prison.

Note: *Name has been changed for data protection purposes.

Source: VAGO, based on review of a sample of prisoner files.

5. Monitoring and evaluating reintegration services

DJCS’s KPIs do not allow it to monitor overall service delivery at the Bridge Centre. This is because DJCS’s reintegration monitoring only measures a small number of participants and only for 2-month post-release performance targets.

The limited available data shows that the Bridge Centre’s results often fall short of performance targets. However, prisoners released from Ravenhall do access the Bridge Centre's reintegration services, particularly to find housing.

DJCS has not done any independent evaluations of Ravenhall or the Bridge Centre in the 8 years since the prison opened. This means DJCS does not know if these unique rehabilitation or reintegration programs are worth continuing or expanding.

Covered in this section:

- DJCS’s reintegration KPIs do not allow it to monitor the full picture. But limited data shows the Bridge Centre often misses targets

- Our data review, site visit and case studies show intensive reintegration case management

- DJCS has not independently evaluated Ravenhall since it opened 8 years ago

DJCS’s reintegration KPIs do not allow it to monitor the full picture. But limited data shows the Bridge Centre often misses targets

Reintegration KPI data

Reintegration performance data is for a subset of former prisoners (called 'pathway participants'), rather than the overall population of prisoners released from Ravenhall.

This is because:

- Ravenhall staff assess prisoners prior to their release and refer them to the Bridge Centre's services based on their individual reintegration needs. For example, a prisoner who plans to move in with family members would not usually be referred for housing support

- for most former prisoners, housing and AOD counselling are the most urgent post-release needs and so most of the Bridge Centre’s services are in these KPIs. This means there is less data on employment, education or mental health KPIs

- to monitor former prisoners 2 months after their release, these individuals must provide their signed consent. Ravenhall staff told us that many refuse this and organisations providing mental health or other support may not share information with GEO. Even if former prisoners do initially consent to monitoring, they may simply disappear into the community after their release.

For these reasons, reintegration KPIs do not provide a complete picture of the Bridge Centre's services or the status of all former prisoners 2 months after their release from Ravenhall.

By monitoring only voluntary 'pathway participants', the reintegration KPI does not allow DJCS to assess the quality of overall reintegration service delivery.

Disconnect between 2-year support timeline and 2-month KPI timeframe

There is also a disconnect between the Bridge Centre's mandate to provide support to former prisoners and their families for up to 2 years post release and the reintegration KPI’s 2-month timeframe.

Our review of sample files found instances where intensive case management worked to meet reintegration needs over more than a 2-month timeframe. Additionally, if a former prisoner lost their initial housing or job, support to find another one within 2 months would not count towards the KPI.

This means that DJCS cannot properly understand GEO's model of reintegration support and whether it is working.

Notwithstanding these limitations, available data shows that the Bridge Centre’s results often fall short of its 2-month post-release performance targets.

Employment KPI

To meet this KPI, 50 per cent of participants must have maintained stable employment (full time or part time) of 20 hours or more per week for 2 months after their release from prison.

Of the 12 quarters that GEO has reported against this KPI, it failed 10.

In late 2024, GEO noted issues in meeting this KPI, which it said was due to prisoners not spending enough time at Ravenhall to complete employment programs while in prison.

To address this, GEO delivered 2 employment expositions in 2025, designed to connect prisoners with prospective employers and support their reintegration into the workforce upon release. Each exposition included up to 8 employers from industries such as construction, warehousing and call centres.

GEO advised us that multiple individuals have since secured employment arising from these expositions. GEO provided us with 3 examples of this.

Housing KPI

The housing KPI requires participants to have maintained stable accommodation at a personal or public residence for 2 months after their release from prison.

The current target is for 57.7 per cent of participants to have maintained accommodation in line with the KPI requirement. Of the 12 quarters that GEO has reported against this KPI, GEO passed 10. This means that the Bridge Centre performs better against housing targets than any other reintegration service type.

AOD treatment KPI

The AOD treatment KPI requires participants to have been referred to and maintained AOD treatment as defined in their reintegration plan for 2 months after their release from prison.

To achieve this target, 60 per cent of all participants need to be referred to and maintain AOD treatment in line with the KPI's requirements.

Of the 12 quarters that GEO has reported against this KPI, GEO passed 4.

Mental health needs KPI

The mental health needs KPI requires participants to be referred to and maintain mental health treatment, as defined in their reintegration plan, for 2 months after their release from prison.

The current target for meeting this KPI is 76.9 per cent of all participants being referred to and maintaining mental treatment as per the KPI's requirement.

GEO reports that meeting this KPI has been challenging because newly released prisoners may not have a fixed address they can use to access an area-based mental health service.

Of the 12 quarters that GEO has reported against this KPI, it passed 4.

GEO told us that since January 2025, it has increased its outreach efforts to former prisoners who consent to be monitored for the mental health pathway. These efforts include providing former prisoners with transportation to scheduled mental health appointments.

Remand KPIs

Since January 2025, new KPIs measure Ravenhall's performance in offering reintegration services to remand (unsentenced) prisoners rather than only for sentenced prisoners.

Remand prisoners often have high reintegration needs because courts release them into the community at short notice.

The target for remand KPIs is for 40 per cent of all participants to have achieved the specific activity within either one or 2 months of their release from prison. GEO met targets in both quarters for housing and AOD treatment, but not for employment or mental health.

Figure 10 shows GEO's performance on these KPIs since January 2025.

Figure 10: Ravenhall’s performance against remand KPIs

| KPI | Target | Q3 (2024–25) result | Q4 (2024–25) result |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15.6 Remand Employment | 40 per cent of participants have maintained stable employment for one month following release from prison | No participants | No participants |

| 15.7 Remand Housing | 40 per cent of participants have maintained stable accommodation at a personal or public residence for one month following release from prison | 75% | 66.7% |

| 15.8 Remand AOD | 40 per cent of participants have maintained AOD treatment for 2 months following release from prison | 50% | 50% |

| 15.9 Remand Mental Health | 40 per cent of participants have maintained mental health treatment for 2 months following release from prison | No participants | No participants |

Source: VAGO, using GEO data.

Our data review, site visit and case studies show intensive reintegration case management

Bridge Centre services

The Bridge Centre assigns prisoners an individual case worker and offers a range of services to meet their post-release needs. Reintegration staff provide support via outreach visits, phone or email. Clients can also visit the Bridge Centre's inner-Melbourne office.

Figure 11 shows that the top type of support that prisoners requested between July 2022 and May 2025 was to find housing.

Figure 11: Nature and number of service contacts at the Bridge Centre between July 2022 and May 2025

Source: VAGO, using GEO data.

Pre-release reintegration services

A major part of Ravenhall's reintegration work starts when an individual enters prison.

Staff routinely carry out an incoming reintegration assessment to see if prisoners have existing housing, employment or other basic services that can be maintained during their prison term.

For example, in the case of a prisoner with intellectual disability and limited English skills, reintegration staff communicated with service providers to make sure the prisoner did not lose his housing or National Disability Insurance Scheme support.

In another case involving an elderly prisoner, Ravenhall staff communicated with Centrelink to make sure his Age Pension was reactivated upon release.

Post-release housing

While many Victorians are struggling to find suitable accommodation amid the housing crisis, former prisoners often face extra barriers. Their criminal record and gaps in rental and employment history put them at a significant disadvantage in a highly competitive market. DJCS and GEO have identified a lack of stable housing as a major risk factor for reoffending.

Unlike DJCS, GEO does not run any transitional housing facilities for men exiting the prison system who would otherwise be homeless. Instead, Bridge Centre case workers refer clients to the Salvation Army's housing assistance service. They also maintain a list of private rooming houses and real estate agents that are open to accepting former prisoners.

During our site visit to the Bridge Centre, we observed that case workers' housing-related tasks were mostly about advocating for clients and accompanying them to housing appointments. Some former prisoners (for example, KPI 15 housing pathway participants) have funding packages that pay part of their rent, while former prisoners needing a few nights of emergency accommodation can receive 'brokerage' funding.

As former Ravenhall prisoners do not frequently access Corrections Victoria's transitional housing, such as the Maribyrnong Community Residential Facility, they may be at a disadvantage compared with those released from public prisons.

DJCS told us that while all former prisoners in Victoria are eligible for the state's transitional housing, it is a last resort and former Ravenhall prisoners should not usually be in that position due to the Bridge Centre's services. DJCS confirmed that a total of 22 former Ravenhall prisoners have been referred to the Maribyrnong Community Residential Facility since it opened in 2020.

GEO’s direct implementation reintegration approach

Our site visit and document review confirmed that GEO primarily uses a direct implementation approach to deliver its core reintegration support, while also collaborating with community organisations.

Instead of relying only on referrals to partner organisations, GEO has 12 full time and 2 part-time caseworkers on staff who each have a portfolio of clients. GEO also has an on-staff AOD counsellor with lived experience who directly supports clients.

Bridge Centre reintegration partners

According to DJCS, private prison operators tend to work in silos and do not have the appropriate networks with community service providers to effectively reintegrate former prisoners.

GEO staff told us that some previous partnerships with service providers ended because they did not match GEO's continuum of care model. This included a partnership with Melbourne City Mission for housing.

A previous employment partnership with YMCA's ReBuild program gave former prisoners construction jobs, but this program shut down in December 2024. The YMCA’s Bridge Project employment case management program is currently the main contracted partner service.

GEO has a range of other community partners for Ravenhall, including the Salvation Army and homeless charities.

While we do not have enough evidence to confirm if a direct implementation or partnership model is more effective, we note that charities are under increasing strain due to the cost-of-living crisis. This means they are likely to prioritise the most vulnerable cases, which may not include former prisoners.

Case studies

The following 3 case studies show the extensive work the Bridge Centre does to support people after they are released.

These individuals had been in prison multiple times and required resource-intensive support to reintegrate. Without this support, these individuals may not have been able to get necessary things such as Centrelink access or a driver’s licence.

All 3 individuals in the case studies did not return to prison.

Case study 4: Post-release reintegration journey

Example of a former prisoner who received intensive case management support and did not reoffend

Luke* was released from Ravenhall in late 2022. Due to a long history of drug-related offences and family violence, this was his sixth time in prison. However, following the Bridge Centre's intensive reintegration case management, this time he did not reoffend.

In the year following Luke's release, his Bridge Centre case manager visited him 20 times. Many appointments were lengthy and involved:

- driving him to housing appointments

- driving him to his previous employer an hour outside of Melbourne to pick up tradesman's tools

- accompanying him to court to support his efforts to get his driver’s licence back.

Initially, the case worker also supported Luke to access Centrelink, an AOD counsellor and supermarket vouchers.

According to one of the final case notes, Luke ‘is now in the best situation he has been in for the last 20 years in terms of housing stability, being substance free, being employed and having pro social relationships’.

Note: *Name has been changed for data protection purposes.

Source: VAGO, based on review of a sample of prisoner files.

Case study 5: Post-release reintegration journey

Example of a former prisoner who received intensive in-person support despite their regional location and who did not reoffend

Scott* was released from Ravenhall in early 2023 after completing his fourth prison sentence. He has schizophrenia and has committed violent offences under the influence of drugs.

After the Bridge Centre's intensive case management, he has stayed out of prison for more than 2 years. When Scott was released to his family home in regional Victoria, a Bridge Centre reintegration case worker completed a 6-hour return trip from Melbourne to help Scott access basic services. This included accompanying Scott to:

- 3 banks to find one that would let him open an account quickly

- a Centrelink office to restart his support payments

- a doctor to make sure he was receiving medication for his psychiatric conditions and to get a support letter to obtain the Disability Support Pension

- a store to buy a mobile phone.

The reintegration caseworker also later supported Scott to set up a myGov online service account and to replace a lost trade certificate. During a phone call later that month, Scott reported that he was doing well and helping his mother with jobs in the house and garden.

This case illustrates a positive outcome, although resource intensive because the Bridge Centre does not have a network of offices across the state like Corrections Victoria.

Note: *Name has been changed for data protection purposes.

Source: VAGO, based on review of a sample of prisoner files.

Case study 6: Post-release reintegration journey

Example of intensive advocacy, housing and brokerage support for an Aboriginal former prisoner who did not reoffend

Darren* is an Aboriginal man who served his latest prison term for breaching a family violence intervention order. He had drug issues and lost custody of his children.

While in prison, Darren completed the Cannabis and Me rehabilitation program as well as the Mumgu-Dhal program to build his connection to culture. Ravenhall staff also supported him to have video calls and write letters to his children. He got a job inside the prison untangling, cleaning and repackaging airline headphones, and his supervisor praised his work ethic.

After his release in mid-2023, Darren returned to his rural town where community organisations said they could not provide him with housing due to his past record of damaging property. With no other options, he moved back into his previous share house where it was difficult to avoid AOD users.

The Bridge Centre continued to advocate for Darren with local housing organisations and visited him 3 times despite it being a 4-hour drive from Melbourne. They also bought him clothes, groceries and a bicycle for transport. They encouraged him to attend his AOD counselling appointments and attend a men's behaviour change program.

When Darren was evicted from the share house, they organised for him to stay at a hotel and subsidised the cost. Darren has not returned to prison.

Note: *Name has been changed for data protection purposes.

Source: VAGO, based on review of a sample of prisoner files.

DJCS has not independently evaluated Ravenhall since it opened 8 years ago

DJCS’s evaluation framework

While DJCS has commissioned independent evaluations of rehabilitation and reintegration programs for Victoria's public prisons in recent years, it has not done so for Ravenhall.

This means DJCS does not know if any of Ravenhall's unique programs are successful. It may be continuing to invest public funds in ineffective programs. Alternatively, it may be missing opportunities to scale up successful programs to other prisons.

Following a recommendation in our 2020 audit, DJCS designed a draft evaluation framework for Ravenhall in 2021. The draft includes:

- in-depth consideration of an evaluation methodology

- key questions to explore the effectiveness of Ravenhall's rehabilitation and reintegration programs.

However, as of July 2025 the evaluation framework has not been finalised or implemented. DJCS told us in July 2025 that it paused work on the framework during the COVID-19 pandemic but work is restarting now that it has revised the KPIs for remand prisoners.

DJCS noted resourcing constraints due to the government's savings agenda.

Without redirecting resources to prioritise this work, it missed the opportunity to evaluate if Ravenhall's rehabilitation and reintegration programs are achieving their intended outcomes and should continue.

While DJCS has not evaluated the big picture of Ravenhall's rehabilitation efforts, we found that:

- it does have a rigorous procedure to verify private prisons’ performance data

- it independently confirms GEO's results before paying performance bonuses.

Appendix A: Submissions and comments

Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary

Download a PDF copy of Appendix B: Abbreviations, acronyms and glossary.

Appendix C: Audit scope and method

Appendix D: Ravenhall rehabilitation and reintegration KPIs

Download a PDF copy of Appendix D: Ravenhall rehabilitation and reintegration KPIs.

Appendix D: Ravenhall rehabilitation and reintegration KPIs.