Reducing the Harm Caused by Gambling

Snapshot

Is the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation effectively reducing the severity of gambling harm?

Why this audit is important

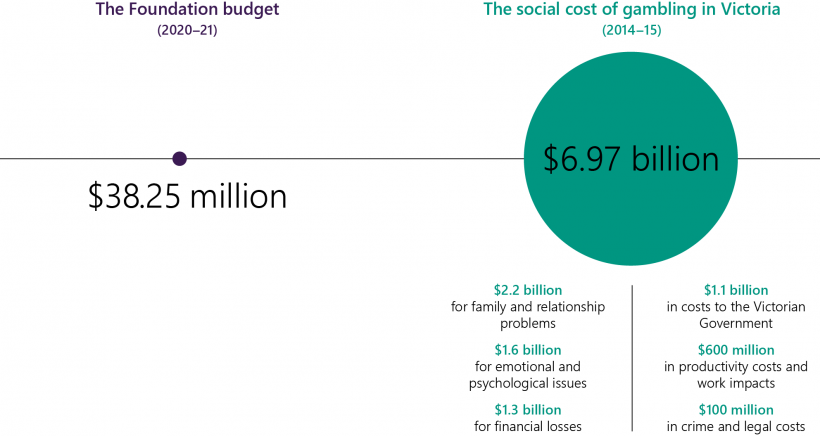

Gambling is legal in Victoria, and easy to access. However, it can cause serious harm for individuals, their family and friends, and for the wider community. Gambling harm costs all Victorians around $7 billion a year, through damage to relationships, health and wellbeing, monetary losses and other social costs.

Who we examined

The Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation (the Foundation) was established in 2012 to reduce gambling harm.

It is a statutory authority under the Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS).

What we examined

We examined whether the Foundation is achieving its intended outcomes and impacts, including through:

- understanding gambling harm

- prevention programs

- treatment services.

What we concluded

The Foundation does not know whether its prevention and treatment programs are effectively reducing the severity of gambling harm.

While the Foundation may help some people through its programs, it does not understand their broader impact. This is because the Foundation lacks an outcome based framework to develop programs and measure their results.

In addition, while the Foundation funds research and program evaluation, it does not always use this evidence to improve program design and service delivery.

What we recommended

We made seven recommendations to the Foundation, including two about applying research and evaluation to improve its programs, three on developing an evaluation and outcomes framework to improve how it funds, evaluates and promotes better practice in reducing gambling harm, one on improving how Gambler’s Help refers clients between different services and one on assessing the effectiveness of different prevention approaches.

We also made one joint recommendation to the Foundation, DJCS, the Department of Health and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing about working together to better support clients with co-occurring conditions.

Video presentation

Key facts

Source: VAGO, and Browne et. al. (2017), The Social Cost of Gambling to Victoria, as published in the Foundation’s Annual Report 2018–19.

Support options

Our report discusses gambling harm, which refers to negative consequences caused or made worse by gambling, including emotional or psychological distress, financial problems, and difficulties with relationships, work or study. Gambling harm may co-occur with other problems such as mental illness, alcohol and other drug use and family violence. If you or someone you know is affected by gambling harm, support options are available. These include:

Gambler’s Helpline

Provides confidential and free support and advice, 24 hours a day, seven days a week for anyone affected by gambling—their own, or someone else's. Gambler’s Helpline can make referrals to local services for financial and therapeutic counselling.

Phone: 1800 858 858 or 1800 262 376 (Youthline)

Gambling Help Online

Provides anonymous, free, confidential advice and counselling through email or 24/7 online live chat.

1800RESPECT—National sexual assault, domestic family violence counselling service

Provides information, referral and counselling services to people experiencing or at risk of experiencing sexual assault or family violence. It is also available to friends and family and professionals. 1800RESPECT provides a confidential service 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Phone: 1800 RESPECT (1800 737 732)

Men’s Referral Service

A men’s family violence telephone counselling, information and referral service operating in Victoria, New South Wales and Tasmania. It is the central point of contact for men taking responsibility for their violent behaviour.

Phone: 1300 766 491

Kids Helpline

Kids Helpline is Australia’s only free 24/7, confidential and private counselling service specifically for children and young people aged five to 25 years.

Phone: 1800 551 800

Lifeline

Lifeline is a national charity providing all Australians experiencing a personal crisis with access to 24-hour crisis support and suicide prevention services.

Phone: 13 11 14

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the Foundation and considered its views when reaching our conclusions. Its full response is in Appendix A.

Understanding gambling harm

The Foundation’s research on gambling harm

Since it was set up in 2012, the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation (the Foundation) has funded academic research that has identified:

- groups most at risk of experiencing gambling harm

- social and environmental factors that contribute to gambling harm

- a high incidence of co-occurring health problems for individuals who experience gambling harm.

The Foundation's research also identified that the most at-risk groups of gambling harm are:

- people with mental illnesses

- young people, particularly males aged 18 to 24 years old

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- people from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities

- people who are socially and culturally isolated, including those living in regional and rural areas.

In this report, we use the terms low-risk, moderate-risk and problem gambler as defined in the Problem Gambling Severity Index, which we discuss in Section 1.2 and Appendix E.

However, we note that terms such as ‘problem gambler’ and ‘responsible gambling’ suggest that people only experience gambling harm because of poor choices or character faults. This can contribute to the stigma around gambling, which may make it difficult for people to seek help. As such we have aimed to limit the use of these terms where possible.

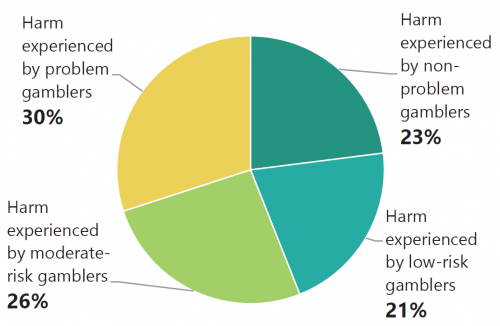

The Foundation's research found gambling harm goes beyond financial losses and includes emotional and psychological stresses. Harm from gambling is more severe at an individual level, but also has wider impacts on the community. Harm from low-risk and moderate-risk gambling makes up 70 per cent of harm in Victoria, as more people engage in this type of gambling and it includes the impacts on families and other relationships.

Applying research to program and service design

The Foundation has used its research evidence to focus its work on:

- prevention efforts targeting the whole community, such as its media campaigns on gambling harm

- prevention and early intervention initiatives, such as the sporting clubs program, for people at low and moderate risk of experiencing gambling harm.

However, since 2015 the Foundation has not funded research into gambling treatment and support services. As a result, it has missed opportunities to use evidence to improve its treatment services.

There is not always a clear link between the research evidence and the Foundation’s program design. For example, its research into ways to reduce stigma and its piloted tools to support gamblers experiencing poor mental health have not been used to improve service design.

The Foundation's lack of a plan to apply research to improving its programs is not consistent with its legislative mandate to reduce gambling harm, or with its responsibility as the sole public funder of gambling treatment services.

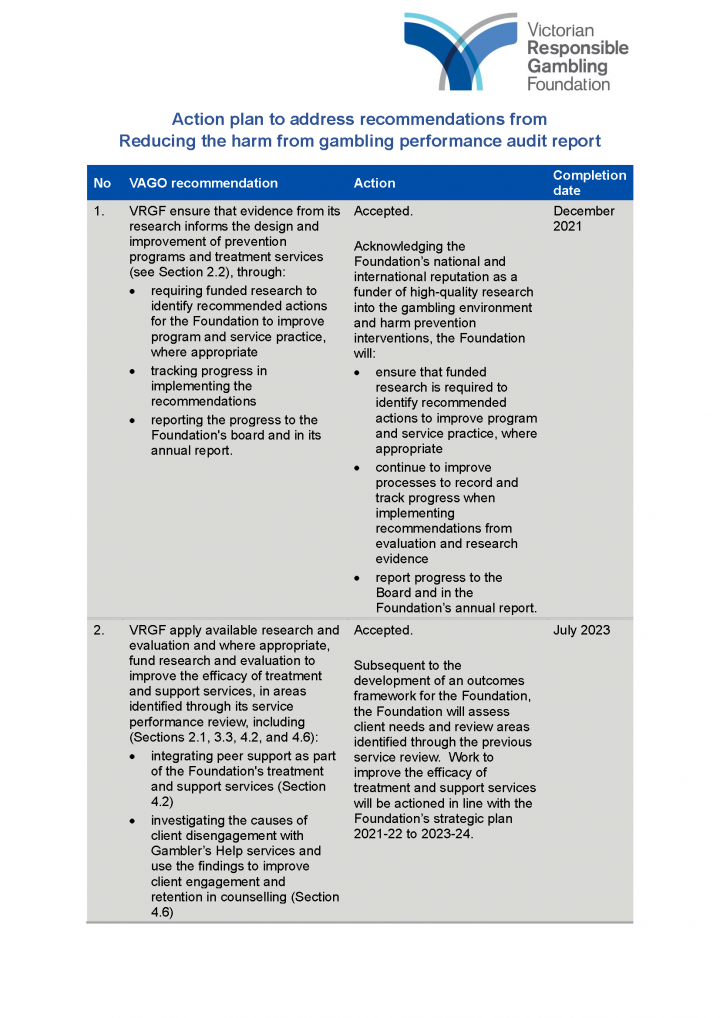

Recommendations about understanding gambling harm

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation | 1. ensure that evidence from its research informs the design and improvement of prevention programs and treatment services (see Section 2.2), through:

|

Accepted |

2. apply available research and evaluation and where appropriate, funds research and evaluation to improve the efficacy of treatment and support services, in areas identified through its service performance review, including:

|

Accepted |

Preventing gambling harm

Prevention programs aim to deter people from activities that may result in gambling harm. This can include providing education about gambling harm or activities to replace gambling.

Outcome-based measures allow an agency to monitor the effect that a program or treatment has had on a person, group or community.

Prevention programs

Programs and services broadly target at-risk groups

Based on its research, the Foundation has developed prevention programs that broadly target at-risk groups. These programs reach target groups because organisations that have links to these communities deliver them.

Prevention programs lack clear aims and outcome-based measures

Most of the Foundation's prevention programs involve general education and raising awareness. Most do not have clear objectives or outcome-based measures that enable the Foundation to know if the programs are effective in preventing harm. This is because the Foundation has not provided sufficient support and guidance to its funded partners to develop these.

Further, the Foundation does not:

- evaluate whether its programs effectively reduce the risk factors or enhance protective factors that influence gambling harm

- take a structured approach to applying the learnings from pilot initiatives to ongoing programs.

Risk factors/protective factors are those relating to a combination of individual, family and community circumstances that can increase/reduce gambling harm. A community venue having pokie machines is a risk factor while having a safe place at night for recreational activities is a protective factor against gambling harm.

The venue support program provides training to staff working at gambling venues to help them identify and support clients who experience gambling harm.

The sporting clubs program aims to counter the normalisation of sports gambling in young people through engaging with local and elite sporting clubs.

Of all the Foundation's prevention programs, its programs targeting sports betting are the most advanced in identifying program objectives and how they intend to impact relevant risks.

The Foundation is addressing these gaps by providing guidelines to funded partners to develop clear objectives and outcomes measures.

Impact of prevention programs

The Foundation has evaluated all its major prevention programs and activities since 2015. This has resulted in some improvements to how it delivers programs, such as refining training material in the venue support program and better targeting groups in the sporting clubs programs. However, the Foundation's evaluations monitor program outputs, such as the number of educational sessions provided, and do not always assess whether a prevention program had an impact on the target group.

This means that the Foundation does not always know what makes a program effective in preventing gambling harm, or how it can invest in the most effective approach.

For example, the Foundation did evaluate its media campaign aimed at reducing the risk that young people believe that gambling is a normal part of sport. The Foundation's evaluation found that this had some success in raising awareness, but it waned over time. The evaluation was useful for understanding the campaign's reach but did not provide insight on the program's impact on harm prevention or reduction.

The Foundation's media campaigns cannot match what sports betting companies spend on advertising, both in scale and intensity, as it has a much smaller budget. Yet media campaigns consume a significant portion of the Foundation's budget. The Foundation should therefore assess the cost-effectiveness of its media campaigns in relation to the overall objective of reducing the risk of harm from sports betting in young people.

Prevention strategy and outcomes framework

Despite funding wide-ranging prevention programs, the Foundation does not have a prevention strategy that outlines what its prevention goals are, the steps it will take to achieve them and how its prevention programs contribute to this.

The Foundation also does not have an outcomes-based framework to measure whether its prevention programs and treatment services are effective in reducing gambling harm. This is despite three organisational reviews, one in 2014 and two in 2018, emphasising the need for one.

Foundation's legislative mandate:

The Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation Act 2011 requires the Foundation to:

- reduce the prevalence of problem gambling

- reduce the severity of harm related to gambling

- foster responsible gambling.

The Foundation has recognised that it has limited understanding of the impact of its programs and services against its legislative mandate and strategic priorities. In December 2019, it developed a draft outcomes framework. However, it is still at an early stage. In early January 2021, the Foundation engaged external consultants to further this work.

The Foundation is in the initial stages of developing common output and outcome measures to better assess its community partnership prevention programs. It has also recently included focus on both the process (how the program is implemented) and outcomes (results achieved) as part of its improved evaluation of the sporting clubs program.

Building community capacity to prevent harm

Despite having invested in 70 projects through community prevention partnership programs since 2014, the Foundation has not provided adequate guidance and resources to actively build the capacity of community groups to prevent gambling harm.

A community of practice is a group of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly.

In late 2019, the Foundation started two communities of practices, open to staff from its funded programs to share knowledge and best practices. While this is a positive step, the Foundation advised us that its role is as a supportive observer, rather than being an active and strategic lead.

Without the Foundation’s leadership, the communities of practice are at risk of operating without any strategic direction. This may limit the extent to which they can achieve sector wide improvements to prevention and treatment programs.

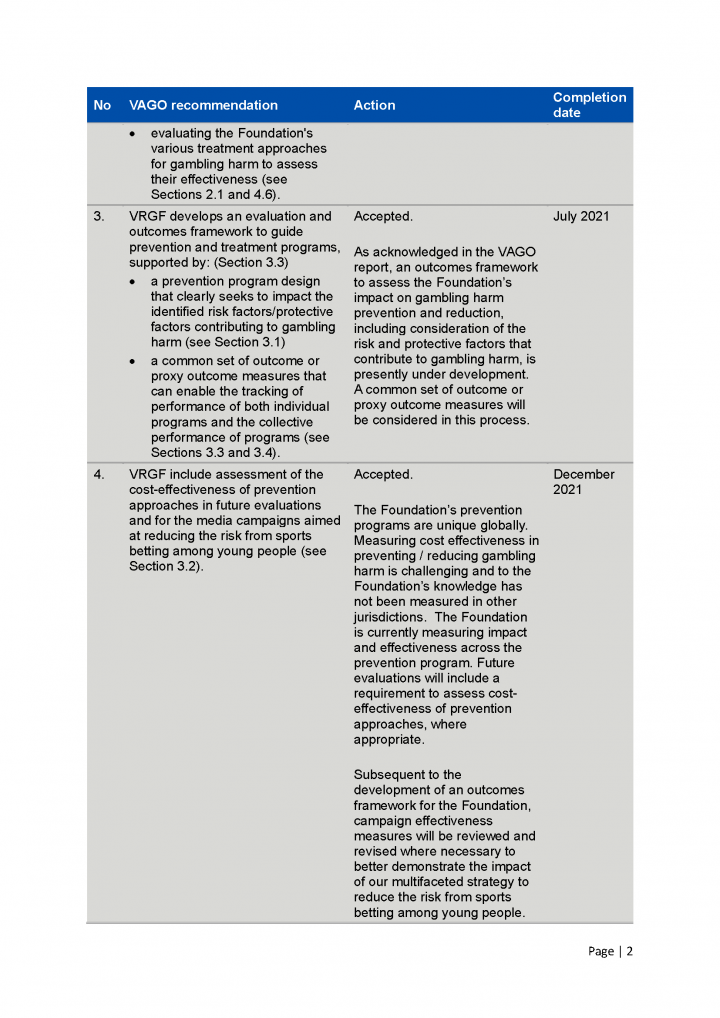

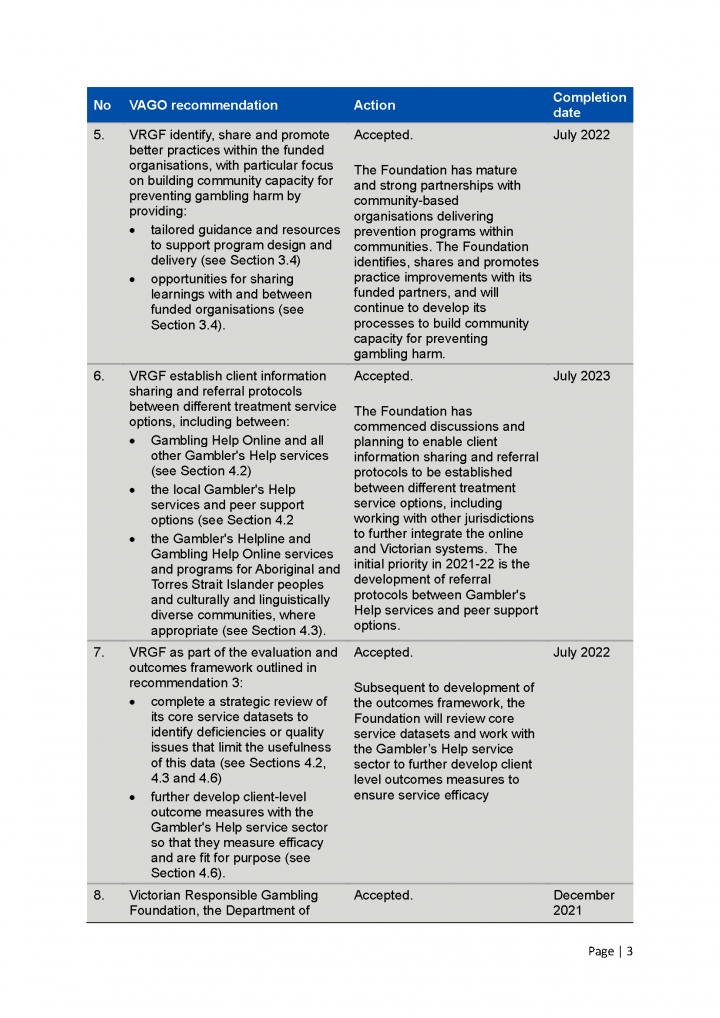

Recommendations about programs to prevent gambling harm

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation | 3. develop an evaluation and outcomes framework to guide prevention and treatment programs, supported by:

|

Accepted |

| 4. include assessment of the cost-effectiveness of prevention approaches in future evaluations and for the media campaigns aimed at reducing the risk from sports betting among young people (see Section 3.2) | Accepted | |

5. identify, share and promote better practices within the funded organisations, with particular focus on building community capacity for preventing gambling harm by providing:

|

Accepted |

Treating gambling harm

Outcome-based performance management

The Foundation funds Gambler’s Help, which provides free and confidential help to Victorians experiencing gambling harm. While Gambler's Help providers know that the service has helped some individuals, the Foundation does not know whether it is effective overall, because it does not have an outcome-based framework to monitor service performance.

Further, the Foundation has not strategically used its extensive service data to improve access or determine whether services are meeting client needs.

Providing service choices for clients

The Foundation has not systematically tested whether its service streams meet clients' needs.

The three Gambler's Help services—Gambler's Help Local, Gambler's Helpline and Gambling Help Online—are largely independent from each other. This means that clients cannot move easily between the service streams to access support in a way that best meets their needs.

The Foundation assumes that clients prefer face-to-face counselling, and so telephone and online services are only for brief interventions or providing information.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Gambler's Help shifted services to a telehealth delivery model. As a result, the Foundation is exploring if telehealth could become an ongoing part of its service, particularly in under-serviced regional and rural areas.

Programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and CALD communities

Programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and CALD communities may include group-based counselling focused on wellbeing, financial counselling, community engagement and awareness-raising activities.

The Foundation has developed tailored prevention and treatment programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and CALD communities. However, there are no formal referral pathways between the Gambler's Helpline and Gambling Help Online services and these programs.

The Foundation is missing an opportunity to improve access and service pathways for people in these communities to the specialised programs from Gambler's Helpline and Gambling Help Online.

Supporting people with co-occurring conditions

The Foundation's research shows that people who experience gambling harm often experience a co-occurring condition. The community organisations the Foundation funds to deliver Gambler's Help Local services also deliver other services, which may include allied health, alcohol and other drugs services, or family violence support. This means they can internally refer gambling clients to one of their other services.

A co-occurring condition is one that is experienced alongside another issue. For example, people who experience gambling harm may also experience mental illness, homelessness or family violence at the same time.

However, the Foundation does not have a system-level process for linking clients with co occurring conditions with other support services, which means that there is no consistent approach. This poses a risk that the help the client receives depends heavily on the service offerings of the particular community organisation they have accessed, and local relationships that entity may have.

At the system level, the Foundation does not have agreed referral pathways between Gambler's Help Local services and the state's mental health, family violence, and alcohol and other drug services. This means that people who experience gambling harm may not be offered appropriate support for their co-occurring conditions, and that people accessing health and human services in Victoria may not be aware that targeted support is available for gambling harm. Although the Foundation has engaged with the state's public health staff, it reported that it has had limited success influencing the state's public health policies.

Developing specialised gambling mental health support

The Foundation funds Alfred Health’s Mental Health and Gambling Harm Program to provide specialised support for gamblers with co-occurring mental illnesses. While this is a positive step, the Foundation has limited capacity to understand whether the program has achieved its intended impact, as its performance indicators are output based. Further, the Foundation does not have a plan, outside of this program, to establish a sector-wide referral process to link Gambler’s Help Local clients with existing statewide mental health services.

Managing performance and client outcomes

The Foundation collects extensive service performance data on its Gambler's Help treatment streams. However, it has not used the data to determine whether services are meeting client needs or to better integrate its three Gambler's Help service streams. For example, better use of the data should inform the Foundation:

- about how many clients disengage with Gambler's Help services after they first contact Gambler's Helpline and why

- on whether its promotion or prevention programs have increased awareness of Gambler's Help services.

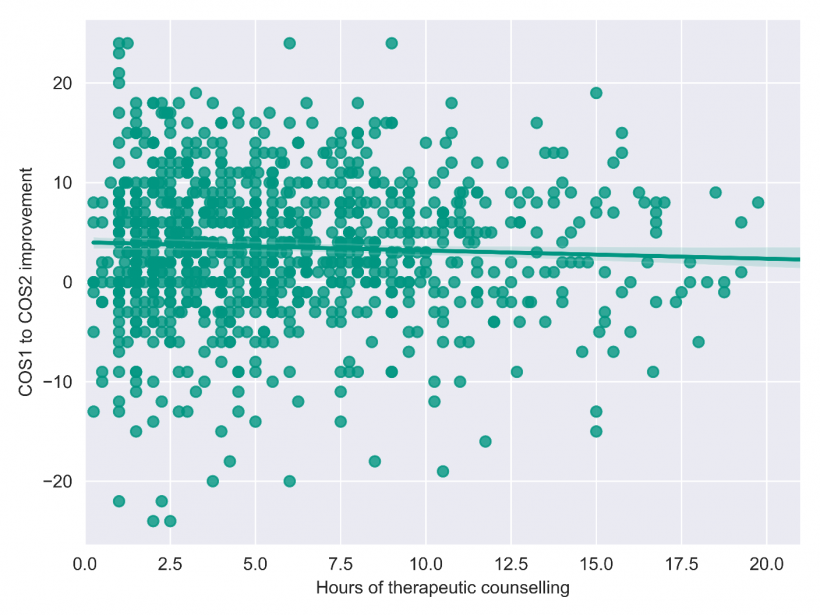

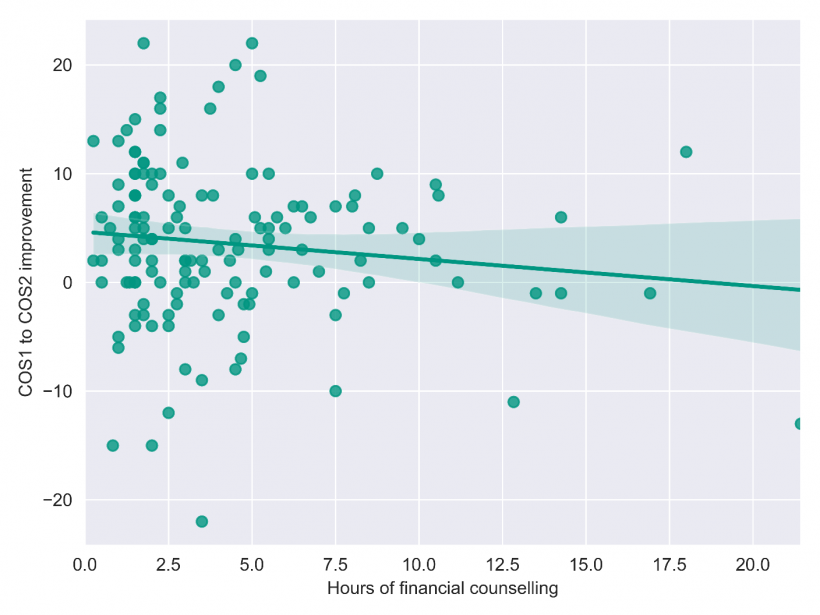

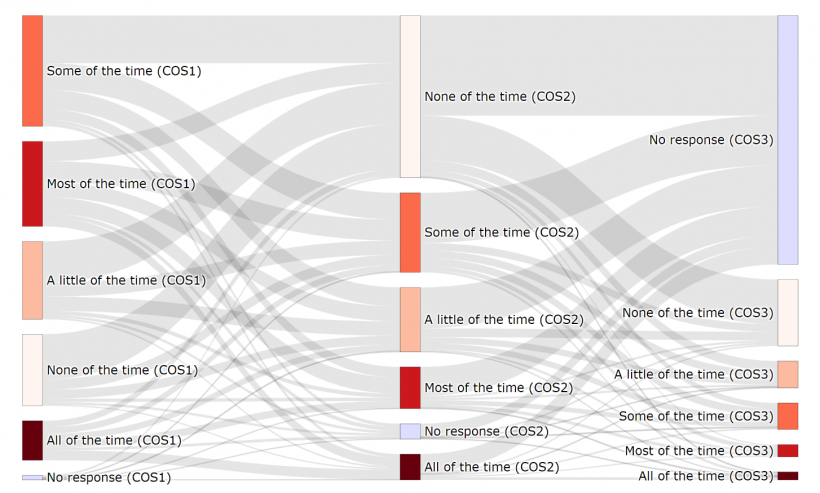

Our analysis of the service data found that many clients have shown slight improvement in their health and wellbeing after treatment based on the measures. However, the degree of improvement did not appear to depend on the amount of counselling received.

This shows that the Foundation is missing opportunities to analyse its existing data to understand how it could improve its service delivery and outcomes for its clients.

Recommendations about programs to treat gambling harm

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation | 6. establish client information sharing and referral protocols between different treatment service options, including between:

|

Accepted |

7. as part of the evaluation and outcomes framework outlined in recommendation 3:

|

Accepted | |

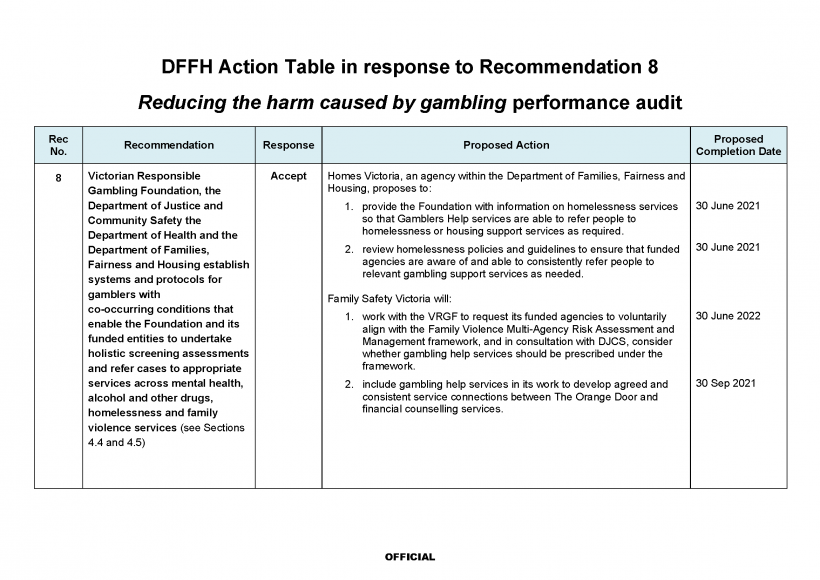

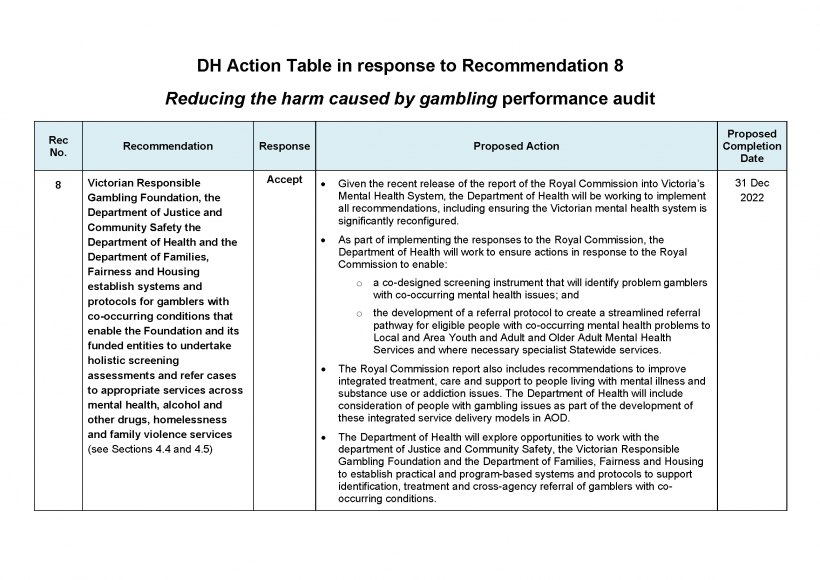

| Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation, the Department of Justice and Community Safety, the Department of Health and the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing | 8. establish systems and protocols for gamblers with co-occurring conditions that enable the Foundation and its funded entities to undertake holistic screening assessments and refer cases to appropriate services across mental health, alcohol and other drugs, homelessness and family violence services (see Sections 4.4 and 4.5). | Accepted by all |

1. Audit context

Gambling is common and socially accepted in Victoria; around 70 per cent of Victorian adults gamble. It is also the fifth highest source of state taxation revenue, worth over $1.7 billion in 2019–20.

However, gambling harm costs Victorians around $7 billion a year. The highest costs are associated with family and relationship problems, followed by emotional and psychological issues, and then financial losses.

To address harm from gambling, the Foundation began operations in 2012 under the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation Act 2011.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 Gambling in Victoria

Types and methods of gambling

Adults can gamble on a range of legal gambling products, in person and online. These include:

- electronic gaming machines or pokies

- casino table games

- betting

- lotteries and raffles

- bingo.

The Foundation's research, conducted in 2018–19, found about 70 per cent of Victorian adults participated in some form of gambling in the prior 12 months. Almost 20 per cent of Victorian adults have gambled online. Online gambling has increased rapidly. It is especially popular with people who bet on sports, with 71 per cent of sports betting taking place online.

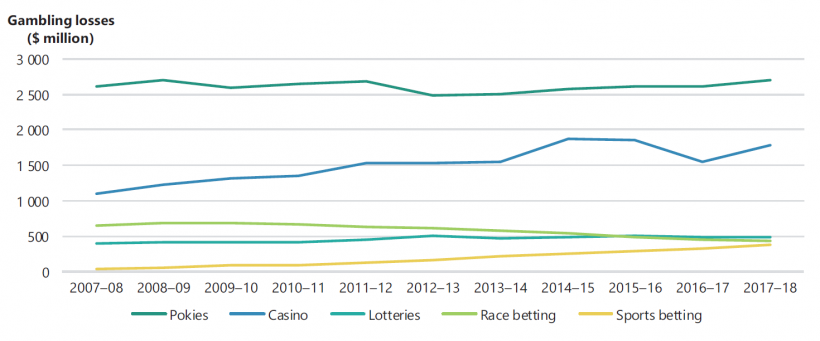

Figure 1A shows losses by gambling product between 2007–08 and 2017–18. While pokies still result in the greatest losses—$2.7 billion in 2017–18—sports betting losses have risen by about 835 per cent in that time, from $39.8 million to $371.7 million.

However, this figure does not include losses recorded at online bookmakers licenced outside Victoria. As a result, actual losses from sports betting are likely to be much higher.

FIGURE 1A: Gambling losses by gambling product 2007–08 to 2017–18, Victoria

Source: VAGO, based on Queensland Government Statistician's Office, Queensland Treasury, Australian Gambling Statistics, 35th edition.

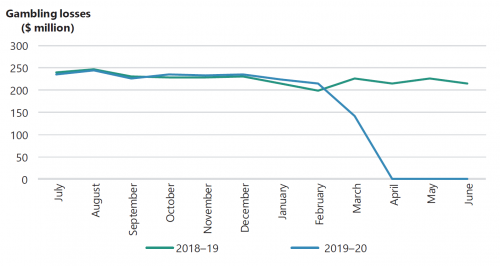

The closure of gambling venues from March to October 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on gambling losses. Figure 1B shows that compared to 2018–19, Victorians spent $710 million less on electronic gaming machines.

However, reported revenue from major gambling companies shows that spending on online betting increased. One major sports betting company reported that its Australian net online revenue was up 45 per cent in the first half of the year.

FIGURE 1B: Monthly electronic gaming machines gambling losses in Victoria, July 2018 to June 2020

Source: VAGO, based on Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, Current gaming expenditure by local government area – monthly, published July 2020.

1.2 Gambling harm

Gambling harm refers to any negative consequence caused, or made worse, by gambling.

Problem gambling

Gambling harm is usually linked to problem gambling, which is characterised by difficulties in limiting money or time spent on gambling.

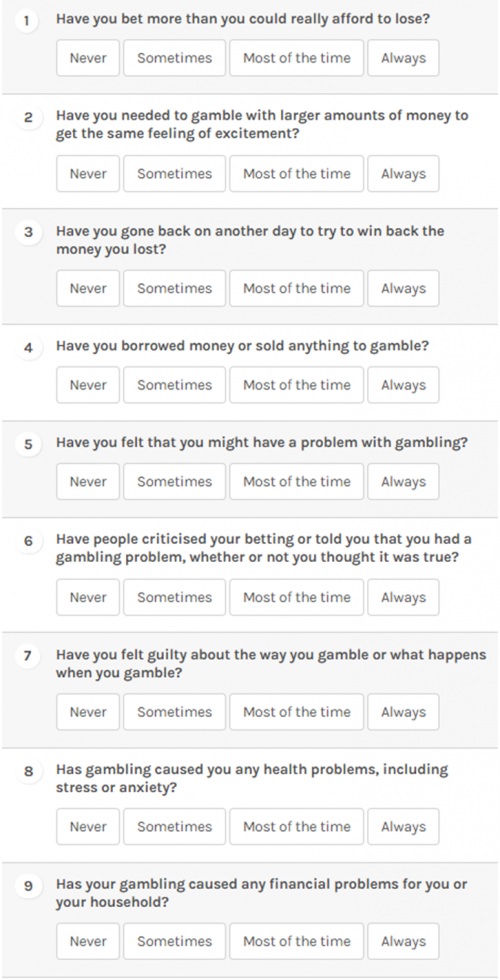

To assess the risk and prevalence of problem gambling, researchers use the Problem Gambling Severity Index (PGSI), which is a standardised measure of at–risk behaviour.

|

If the PGSI score is … |

Person is categorised as ... |

For example … |

|

0 |

Non-problem gambler |

A person’s gambling has no negative consequences. |

|

1–2 |

Low-risk gambler |

They may very occasionally spend over their limit or feel guilty about their gambling. |

|

3–7 |

Moderate-risk gambler |

They may sometimes spend more than they can afford, lose track of time, or feel guilty about their gambling. |

|

8 or above |

Problem gambler |

They may often spend over their limit, gamble to win back money and feel stressed about their gambling. |

The Foundation has provided a PGSI that people can use to self-assess their level of risk. We include this tool in Appendix E.

Gambling harm

Gambling harm is not limited to those who gamble at risky levels as assessed by the PGSI. It can affect the family or friends of those who gamble, and the wider community.

Research funded by the Foundation identified seven types of gambling harm:

- relationship difficulties

- health problems

- emotional or psychological distress

- financial problems

- issues with work or study

- cultural problems

- criminal activity.

Regression analysis is a statistical process that estimates or predicts the relationships between a dependent variable (such as gambling harm) and one or more independent variables (relationship problem, health, emotional stress, and financial losses).

This research, based on regression analysis, found that most gambling harm (50.2 per cent) is related to low-risk gambling behaviour, rather than problem gambling (15.2 per cent). Relationship harm is the most common type of harm from gambling. It makes up a quarter of all gambling harm experienced by Victorians. Other significant harms are to health (21 per cent), emotional or psychological distress (18.6 per cent), followed by harm from financial losses (15.6 per cent).

Health and gambling

Research shows that people experiencing gambling harm often have co occurring conditions, such as:

- mental illness—about 40 per cent of problem gamblers also have a diagnosed mental health condition

- alcohol and other drug use—about 65 per cent of problem gamblers consume excessive alcohol

- family violence

- homelessness

- financial hardship

- legal problems

- unemployment

- a relationship breakdown.

1.3 A public health approach to gambling harm

In 2010, the Productivity Commission recommended that governments continue to provide support to individuals who gamble, but also take a broader, public health approach to addressing gambling harm.

Public health approaches to gambling aim to:

- concentrate on building a well-functioning community, rather than focus on only the individuals who experience harm

- prevent the harms associated with gambling from occurring, rather than focus only on treating individuals with gambling problems when the problems have occurred.

As shown in Figure 1C, the World Health Organization's framework for developing public health interventions involves four key steps.

FIGURE 1C: The steps of a public health approach to interventions

1.4 The Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation

Established in 2012 under the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation Act 2011 (the Act), the Foundation is a statutory authority to address gambling harm in the Victorian community.

Responsibilities and alignment with other authorities

The Act requires the Foundation to:

- reduce the prevalence of problem gambling

- reduce the severity of harm related to gambling

- foster responsible gambling.

The Foundation does not regulate gambling activity in Victoria. State and federal government agencies share gambling regulation and policy development:

- The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation regulates gambling through licensing and compliance activities.

- The Department of Justice and Community Safety (DJCS) develops policy for the gambling and racing industries and advises the Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation.

- The Australian Government regulates online gambling and gambling advertising during live sports broadcasts.

The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion

Over the past eight years, the Foundation has evolved its approach to gambling harm to align with principles of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (the charter), which is an internationally recognised framework by the World Health Organization.

The charter recommends that public health initiatives should prioritise action in the following domains:

- building healthy public policy

- creating supportive environments

- strengthening community action/capacity building

- developing personal skills

- reorienting health services toward prevention of illness.

The Foundation still delivers treatment services for people who experience gambling harm, but it has reshaped its programs and strategic priorities to focus more on prevention and early intervention.

The Foundation's funding and strategic priorities

The Victorian Government funds the Foundation on a four-year cycle from the Community Support Fund, which is generated from revenue from electronic gaming machines in hotels. The 2018–19 state budget allocated $153 million over four years to the Foundation. This was a $3 million increase on the Foundation's previous funding cycle, designed to support programs for harm prevention.

In 2018, the Foundation released its first three-year plan, setting out its strategic priorities for 2018–21:

- A public health approach to prevent gambling harm.

- A partnerships approach to improve community health and wellbeing.

- A collaborative approach to build itself as a centre of expertise to deliver its mission for all Victorians.

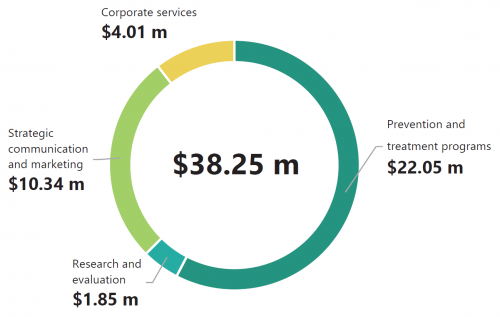

Figure 1D shows the Foundation's 2020–21 budget allocations against its main business functions.

FIGURE 1D: The Foundation's budget allocation by business function, 2020–21

Source: VAGO, based on the Foundation's information.

This budget allocation can also be broken down between prevention and treatment streams, which combines program delivery and communication and marketing spend. In 2020–21, this totalled $30.76 million, as follows:

|

Stream … |

Funding in 2020–21 … |

Aims to … |

|

Prevention programs |

$15.82 million |

|

|

Treatment and support services |

$14.94 million |

|

1.5 Prevention programs

The Foundation's prevention programs target different groups as follows:

|

Prevention program … |

Targeting … |

Is delivered by … |

Providing … |

|

School education program |

secondary school students across Victoria |

Gambler's Help Local |

|

|

Venue support program |

staff at gambling venues, such as pubs and hotels |

Gambler's Help Local |

|

|

The prevention partnerships program The strategic partnership initiatives |

at-risk community groups, such as migrants, refugees |

community organisations |

|

|

Community engagement program |

locally identified at-risk groups, such as migrant youth and CALD groups |

Gambler's Help Local |

|

|

Local sporting clubs program Elite sporting clubs partnerships |

young players and their key influencers in community sport settings the wider community, including fans and their families |

the Foundation's contracted provider |

|

|

Media campaigns:

|

all Victorians |

the Foundation |

|

We assess the Foundation's prevention programs in Chapter 3.

1.6 Treatment and support services

The Foundation's treatment and support services involve both therapeutic and financial counselling:

- Therapeutic counselling aims to support clients by changing the way they think about gambling, such as helping clients to understand what triggers them to gamble and how to resist the urge.

- Financial counselling aims to help clients improve their financial situation when they experience financial hardships from gambling.

The Foundation's key treatment and support services are as follows.

|

Service … |

Is delivered by … |

Providing … |

|

Gambler's Help Local |

11 contracted service providers |

face-to-face therapeutic and financial counselling across 100 locations in 15 catchment areas |

|

Gambling Help Online and Gambler's Helpline |

contracted provider Turning Point |

telephone hotlines, online self-help tools, online chats, email and online peer-to-peer support 24-hours, seven days a week |

|

*Peer–to–peer support service |

people with lived experience of gambling harm |

non-crisis, confidential support across the broader Victorian community and in language to the Chinese community |

|

*Targeted services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and for CALD communities |

four Aboriginal communities’ Community Controlled Health Organisations in Melbourne, Bairnsdale, Shepparton and Mildura |

the Aboriginal Communities’ Gambling Awareness Program |

|

five established ethnic community organisations |

a mix of prevention and treatment services to Chinese, Vietnamese and Arabic–speaking communities |

|

|

*Specialist mental health program |

Alfred Health |

a combination of brief case assessment and review to Gambler's Help clients provided by qualified mental health specialists |

Note: All services are available across Victoria except for the services marked with *.

We discuss the treatment and support services in Chapter 4.

2. Understanding gambling harm

Conclusion

The Foundation has developed an extensive research base to support its work. Through its research it has identified the groups most at risk of experiencing gambling harm and understands how gambling can co-occur with other health problems.

However, the Foundation does not always apply research findings in its service design. This means it is not realising the benefits of its research investment and is missing opportunities to improve its services and programs to best meet the needs of at-risk groups.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Understanding gambling and gambling harm

As part of its shift from just focusing on treating people with gambling problems to a broader public health approach, in 2013 the Foundation funded research to better understand how it could prevent and reduce gambling harm. This research supports the Foundation's increased focus on prevention efforts targeting the whole community, and early intervention initiatives for people at low and moderate risk of experiencing gambling harm.

The Foundation's research program

Since 2014, the Foundation has awarded 50 research grants. Grant recipients have published 40 peer-reviewed reports on a wide range of topics, including the:

- risk factors contributing to groups being at risk of experiencing gambling harm

- social and cultural factors that shape attitudes, beliefs, and behaviours about gambling among demographic groups

- impact of new gambling products, including of online gambling on young people

- normalisation of gambling across the community through sports betting.

The Victorian Population

Gambling and Health Study

2018–2019 involved a mobile phone and landline survey of 10 638 randomly selected Victorian adults conducted in 2018–19.

Population-level studies on gambling behaviour

In 2014 and 2018 the Foundation funded population surveys of gambling behaviour in Victoria. Its publication Victorian Population Gambling and Health Study 2018–2019 uses the 2018 survey results. The study found that the most harmful gambling forms are:

- electronic gaming machines

- online wagering

- casino table games

- Keno.

In Victoria, most gambling harm (65.9 per cent) occurred from these products.

The study also found that many factors contribute to gambling harm, such as individual circumstances, environmental and cultural factors. It clearly identified that people categorised as moderate and problem gamblers are more likely to be:

- people with mental illnesses

- young people, particularly males aged 18 to 24 years old

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- people from CALD communities

- people who are socially and culturally isolated, including those living in regional and rural areas.

The Foundation has developed and funded programs targeted to the needs of these cohorts. For example:

- five ethnic community organisations deliver Gambler's Help and awareness-raising programs in Chinese, Vietnamese and Arabic

- four Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisations deliver the Aboriginal Communities’ Gambling Awareness Program

- the Foundation's school education and sporting clubs programs target young people for early intervention.

Research on defining gambling harm

In 2016, the Foundation released world-first academic research into gambling-related harm and the factors that contribute to it. The Foundation used this to shape its approach to gambling as a public health issue.

The research found that gambling harms are diverse and affect many more people than just those engaged in problem gambling. The research findings included that:

- more than half a million Victorians experience harm from gambling each year

- for every individual who experiences severe gambling harm, up to six other people are affected, including family members and friends

- 85 per cent of the gambling harm in Victoria is experienced by people in the low and moderate-risk groups for problem gambling

- gambling harm is not limited to financial losses. A quarter of all gambling harm involves relationship issues.

Also, in 2018–19 it found that 70 per cent of gambling harm is experienced by people whose behaviour is not classified as problem gambling. Figure 2A shows this.

The research findings support the Foundation's shift to a public health approach. Since 2014, the Foundation has increased funding allocation to prevention programs, expanded from the initial venue support and school education programs to a wide range of prevention programs, such as its community-based prevention partnership programs.

FIGURE 2A: Proportion of Victorian population experiencing gambling–related harm by PGSI status, 2018–19

Source: The Foundation, based on Rockloff et al (2020), Victorian Population Gambling and Health Study 2018–2019.

Research on policy and environmental factors

Public health research aims to identify ways to reduce harm that go beyond raising awareness or treating individuals, such as how government policy can influence the industries and social environment to prevent harms.

The Foundation has commissioned and published several public health research projects exploring the broader environmental and contextual factors that contribute to gambling harm. Since 2014, it has researched the impact of gambling marketing methods on at-risk groups. In response, the Foundation developed a suite of programs targeting the normalisation of sports betting among young people.

Public policy development

It is the role of DJCS—not the Foundation—to advise government on gambling policy. However, the Foundation can contribute to better public policy development by providing evidence to departments such as DJCS and the Department of Health, and government. This is because it has a unique advantage through its research and prevention programs to understand how gambling harm affects the broader community.

The Foundation has contributed to public inquiries and provided advice to government. This includes advice to the Victorian and Australian governments on gambling operations, such as its submissions to Victoria's royal commissions into family violence and mental health.

In June 2019, the Foundation published an exploratory report on the effectiveness of policy interventions on minimising harm from alcohol and tobacco, and how this might help address gambling harm. In April 2020, the Foundation provided advice to government based on this research in relation to policy opportunities for venues reopening post closures related to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Research into treatment and support services

The Foundation's treatment and support services remain its single largest program by funding, making up $14.94 million in 2020–21. However, since 2015, the Foundation has not prioritised funding research into the efficacy of different treatment and support approaches.

In 2013, the Foundation decided that research on the effectiveness of clinical treatment was not cost–effective and did not align with its new public health approach focused on prevention. As a result, the Foundation only funded limited research into parts of their treatment services.

This means, for example, it does not know how effective:

- its various service streams are in overcoming client stigma

- Gambler's Help services are at supporting people with co-occurring health problems.

Foundation-funded research shows both issues are critical in reducing the severity of gambling harm.

As a result, the Foundation has missed the opportunity to better understand the efficacy of its treatment services, as we discuss further in Chapter 4.

2.2 Applying research

The Foundation is not maximising the value of its funded research by using it to inform the design of its programs and services, such as in better targeting its programs to the risk factors affecting gambling harm.

The Foundation has published and distributed its research through its website and newsletters to Gambler's Help providers. Through its gambling harm conferences, it has also successfully promoted gambling harm as a broader public health issue. For example, in 2018, 203 of the total 400 conference attendees were outside of its funded organisations for Gambler's Help.

However, the Foundation does not consider that it is its role to embed research findings into service design and delivery. It believes that is the role of individual service providers.

The Foundation's mandate is to reduce gambling harm. Being the only funder for Gambler's Help services, it is accountable for continuously improving the efficacy of funded programs and service, such as by incorporating better practices identified through research and evaluation.

The Foundation’s programs and services do broadly target groups that research identifies as having a high risk of experiencing or developing gambling harm. However, the link between the research evidence and the Foundation’s program/service design is not always clear. We discuss two examples below.

Applying stigma research to service design

The social stigma associated with gambling prevents many individuals from using support services. The Foundation has funded research that identified ways to reduce stigma, but it has not used this research to reduce access barriers for people seeking treatment.

In 2015, Foundation-funded research found that only 22 per cent of problem gamblers seek help. For people experiencing moderate harm from gambling, the rate drops to 2 per cent.

Foundation-funded research in 2016 suggests the stigma associated with gambling is stronger than that associated with mental illness or drug and alcohol issues. This means that it is essential that the Foundation addresses this barrier to ensure it can effectively engage with and support clients to maximise their chance of recovery.

Evidence suggests that there are a range of responses the Foundation could implement to address stigma and improve service access.

|

People exposed to stigma and seeking help … |

This means treatment services need to … |

However, the Foundation |

|

need to feel supported on first contact with treatment services. The Foundation's research shows that arranging access to treatment within 72 hours of a client's first contact boosts their engagement with services. |

engage clients at the first point of contact and help them transition to other service streams as smoothly as possible. |

incorporated its research into its service design to make sure clients can access treatment and have a referral to Gambler's Help Local within 72 hours of first contact. |

|

need to feel they can trust and have rapport with service providers. |

show they understand the client's experience, such as by providing peer support to sustain engagement and ongoing support. |

integrated peer support as a viable statewide service option. |

|

need to be able to reach out to appropriate services when they want to seek help, at anytime and anywhere. |

provide flexible solutions that are available 24 hours, seven days a week, such as Gambler's Helpline/Gambling Help Online. |

required Gambler's Help Local to refer clients to its flexible services such as Gambler's Helpline or Gambling Help Online, nor further developed its peer support program to address stigma issues. |

Despite the research finding that client engagement is better within the first 72 hours, the Foundation only requires Gambler's Help Local providers to contact the client within five business days after Gambler’s Helpline refers a client to a provider. The Foundation has not acted to require Gambler's Help Local providers to contact clients sooner and consequently may be missing out on opportunities to better engage clients.

The Foundation’s Our strategic priorities 2018–21 includes a commitment to developing a strategy to address the stigma related to gambling harm. The Foundation initially intended that this would be a 10-year standalone strategy. After completing a review of gambling-related stigma in 2019, it no longer intends to do this, as addressing stigma is an integrated part of its current activities.

The Foundation’s approach brings together existing components across its communications, research and program delivery to address stigma on an ongoing basis. However, there is no detailed work plan or outcomes from this approach. This means we cannot conclude whether this approach will be effective in reducing stigma and improving support for people experiencing gambling harm.

The Foundation will also include stigma reduction as part of the next three-year business strategy, due to start in July 2021.

Screening for people with co-occurring conditions

While the Foundation has piloted tools to support early identification of gamblers experiencing mental health issues, it has not rolled these out in mental health services.

The Foundation funded the development of a:

- self-assessment tool for mainstream health agencies in 2014, which the Foundation reported as useful in 2016

- short screening tool in 2017 to assist general practitioners and mental health services to identify problem gambling in clients and to refer them to Gambler's Help Local at an earlier stage.

The Foundation evaluated the self-assessment tool as being beneficial and promoted it at its 2016 and 2018 conferences, as well as through its professional development activities. However, it has not sought to support the rollout of these tools more broadly in mainstream health services.

3. Preventing gambling harm

Conclusion

The Foundation has developed a range of programs and pilot initiatives that aim to prevent gambling harm. However, the Foundation does not know if it is preventing gambling harm, as its program evaluations focus on outputs rather than on outcomes and impacts. This makes it difficult for the Foundation to understand what makes a program effective and to identify which pilot initiatives to scale up.

In addition, the Foundation does not have an overarching prevention strategy to guide its work and measure its impact.

This chapter discusses:

3.1 Developing prevention programs

As discussed in Section 1.5, the Foundation’s prevention programs consist of education and awareness programs targeting specific settings such as schools, gambling venues and sporting clubs, as well as population–based media campaigns. In addition, community groups and Gambler's Help services deliver the Foundation's suite of community prevention partnership programs to raise awareness of gambling harm in at-risk groups such as migrants and CALD communities. In 2020–21, the Foundation allocated $15.82 million to these programs.

Designing prevention programs

Public health involves developing and evaluating interventions, as shown in Figure 1C. A well-designed prevention program needs to:

- clearly identify the problem, including at-risk groups that may have or will experience the problem

- define risk factors or protective factors, and design prevention programs to influence these factors, which is assessed through program evaluation

- have clear program aims and key outcome indicators or proxy measures to monitor the intended impact.

Except for the programs targeting sports betting described in Section 1.5, most of the Foundation's preventative programs do not align with these principles because they do not address the underlying risk factors or have clear outcome indicators.

Targeting at-risk groups

The Foundation's programs broadly target the at-risk groups identified in its research as needing support.

The prevention partnership programs reach target groups because they are delivered by community organisations that are already established within targeted communities.

Since its launch in 2014, the sporting clubs program has targeted young adults over sports betting. It operates in over 300 local and elite sporting clubs, such as the Australian Football League in Victoria and Football Victoria. The elite clubs stream encourages its member sporting clubs to reduce their reliance on gambling sponsorship and electronic gaming machine revenue.

While the sporting clubs program targets young adults, the program's evaluation in 2017 found it needed to target younger cohorts of 12–17 years old. The Foundation launched the redesigned program in 2019. In the redesign, the Foundation incorporated recommendations to:

- target younger people (12–17 years)—through engaging with the junior players in the sporting clubs

- improve program planning and integration between both local and elite clubs with consistent branding and messaging.

The changes should help the sporting clubs program to become more targeted, integrated, and strategic at preventing gambling from being a normalised activity.

Addressing risk factors

The Foundation's prevention programs, such as the venue support program, school education program and prevention partnership program, do not clearly identify how the program activities are designed to impact identified risk or protective factors. Rather, they are about raising awareness that gambling is harmful. A 2013 Foundation evaluation concluded that general awareness raising is not effective at changing attitudes and behaviours in the long term.

Only the sporting clubs and the media campaign programs have clear aims to address the underlying risk factors. For example, targeting sports betting is strategic, given its rise in popularity. The programs directly aim to address the risk of normalising gambling through betting on sports.

Having clear aims and outcome indicators

The Foundation's prevention programs are varied, as listed in Section 1.5:

- school education program

- venue support program

- community prevention programs for vulnerable groups including migrants and refugees (Gambler's Help for at-risk communities)

- the sporting clubs programs covering both local and elite sporting clubs

- media campaigns.

Apart from the sporting clubs and media campaign programs, the rest of the Foundation's prevention programs do not have clear objectives or outcome indicators. As such, the Foundation's program evaluations focus on outputs rather than outcomes and the Foundation has little knowledge about whether its programs and services are effective in preventing or reducing gambling harm.

Figure 3A shows an example of the output monitoring for the longstanding venue support and school education programs.

FIGURE 3A: Venue support and school education programs output monitoring

| Program | Activity | Output in 2018–19 |

|---|---|---|

|

Venue support |

|

|

|

School education |

Aims to challenge the normalisation of gambling among adolescents by:

|

|

Note: A self-exclusion program allows a person to ban themselves from gambling venues such as pubs, clubs and bookmakers. If venue staff see a person in the gaming area of their venue who has excluded themselves, they will report them to the program and ask them to leave. It is also possible to self-exclude from gambling websites.

Source: VAGO, based on the Foundation's information.

3.2 Impact of prevention programs

The Foundation has evaluated all its major prevention programs and activities since 2015.

Venue support program

A 2018 program review found venue staff training has improved the awareness of, and confidence in, venue staff to recognise and interact with individuals experiencing gambling problems.

The Foundation has not evaluated if the program is reducing harm. It does not know if the venue support program has increased the number of referrals to the self exclusion program or to the Gambler's Help programs, which is one of its program objectives.

School education program

A 2019 program review recommended that the Foundation, among other things:

- expand online resources instead of only using face-to-face delivery

- target younger age groups

- measure program impact through ongoing monitoring and evaluation.

The Foundation intends to update key elements of the program and develop a longer-term strategy on youth and gambling harm. However, it has not provided a plan or timeline on how it will implement the above recommendations.

Impact of media campaigns

It is difficult to change attitudes and behaviours using short media campaigns, and the Foundation cannot match the advertising spend of the gambling industry (Figure 3B).

In 2019, the gambling industry spent $70 million promoting gambling in sporting events in Victoria. In contrast, the Foundation allocated $2.62 million in its 2019–20 budget for media campaigns during live sports.

The Foundation advised us that population level behaviour change requires:

- a sustained level of mass media activity over time

- a broader response that includes local program and service delivery, policy and advocacy and other community interventions.

However, while these observations may be true, without a strategic framework within which to assess the most effective levers for behavioural changes, the Foundation does not know how to best achieve population-level changes.

FIGURE 3B: Case study—Love the Game media campaign

During the 2018 Australian Football League finals, the Foundation ran a 'Love the Game' media campaign.

The campaign ran from 26 August to 30 September 2018, a time when both viewership and sports betting advertising were particularly high.

The Foundation spent $887 896 on the campaign and advertised on television, radio and digital channels. Its evaluation found that:

- it reached 49 per cent of Victorians aged 30 to 55, including 51 per cent of the primary target audience (parents of 12 to 17-year-olds)

- television was the main source of exposure

- ‘there was some gradual decrease in favourable attitudes to parents’ role in talking to their children’, indicating that the effectiveness of the campaign message waned over time.

Source: VAGO, based on the Foundation's information. Photographs courtesy of the Foundation.

3.3 Prevention strategy and outcomes framework

A good prevention strategy helps an organisation, its partners and the public to understand what its prevention goals are, what steps it will take to achieve them, and how its prevention programs contribute to this.

A 2016 evaluation of the Foundation's prevention partnership programs identified the need for a prevention strategy. A longer-term prevention strategy would help the Foundation plan beyond its four-year funding cycle, to guide how it funds and evaluates prevention projects against overall prevention goals. This is necessary for the Foundation to know whether its wideranging prevention activities are achieving its overall goal of preventing gambling harm.

The Foundation has no outcome-based framework that sets out how to measure if prevention programs and treatment services are influencing the risk factors.

The Foundation has been slow to develop a outcomes framework, despite three organisational reviews pointing to such a need, one in 2014 and two in 2018. The Foundation advised us that it is difficult to measure the effectiveness of public health interventions, particularly as public health approaches to gambling are relatively new. However, other organisations—such as VicHealth—have evaluated public health approaches to tobacco, alcohol and other drugs, and health promotion for some time.

In addition, the Foundation has lacked a coordinated process to build learnings and better practices from the pilots to program development. In the absence of an outcome-based framework, the Foundation's implementation of its research and evaluation findings depends more on its budget and the priorities of individual staff members than on an overall strategy.

Next steps

The Foundation has recognised that its performance management framework is inadequate for assessing the impact of its programs and services against its legislative mandate and strategic priorities.

It is in the early stages of improving how it evaluates its prevention partnership programs. The Foundation’s funding agreements require recipients to work with the Foundation to develop a program logic, which outlines the project objectives and outcomes. The revised evaluation includes a set of standard questionnaires that measure changes in participants’ awareness, attitudes and behaviours before and after attending the community prevention activities. It first applied this approach in August 2020 to evaluate these prevention partnership programs.

While this is a step in the right direction, the Foundation needs to link these short term, program-based outcome measures with medium and long-term ones so that it can meaningfully measure the full impact of its prevention work. This will help it to make strategic decisions about which programs to fund or expand.

3.4 Building community capacity to prevent harm

Since 2014, the Foundation's largest investment in prevention initiatives is its suite of community partnership prevention programs. In 2020–21 the Foundation allocated $5.23 million, up from $2.2 million when it launched in 2014.

The Foundation's community prevention partnership programs aim to build the funded organisations’ capacity to take actions against gambling harm. This aligns with the principles of the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. However, the Foundation has failed to actively help capacity building by not providing adequate:

- guidance

- resources

- opportunities for these groups to share lessons learnt across similar projects.

The Foundation has invested in about 70 projects since 2014 and evaluated most of these. However, the Foundation does not have a systematic process to apply project level learnings to guide further program development. This means that it does not have a clear understanding of what has worked. It also does not know what is needed to build the capacity of community groups to prevent gambling harm.

Communities of practice and sector development hub

The Foundation does not have a sector-level process to identify, share and promote practice improvements within funded organisations.

Each Gambler's Help Local service operates independently. This makes it challenging for the Foundation to promote continuous improvement among providers.

The Foundation's 2016 and 2018 evaluations of the community prevention partnership programs recommended a community of practice for prevention.

In late 2019, the Foundation realigned the purpose of its professional training hub known as the sector development hub. It aims to create greater opportunities for collaboration:

- between prevention partners from different programs

- between therapeutic and financial counselling staff from Gambler's Help.

The Foundation conducts a range of activities to engage with funded partners and to disseminate information, including training sessions and quarterly peer networking forums for funded partners.

In May 2020, the Foundation helped establish two communities of practice on youth and CALD issues. These are open to staff from all funded organisations and are to meet at least monthly. The Foundation advised us that it intends to play an observational and supportive role in how the communities of practice operate. It intends for them to be largely organised and governed by community organisations.

While communities of practice may provide opportunities for staff from funded programs to learn from their peers, only the Foundation can play a statewide sector development role. Based on the minutes of meetings, community of practice forums have mostly been information sharing sessions. They are at risk of operating without strategic direction and may not provide sector-wide improvements without the Foundation’s leadership.

The Foundation advised us that despite offering professional development opportunities and training, it does not consider its role to provide leadership to the gambling counselling sector. It views this as the role of a peak body or organisation for gambling counsellors. However, in the absence of a peak body, and given that Gambler's Help Local services are the primary employer for counsellors working in the gambling sector, the Foundation needs to play a leadership role to achieve its legislative mandate.

4. Treating gambling harm

Conclusion

While Gambler's Help providers know that they have helped some individuals, the Foundation does not know whether its treatment services are effective overall. This is because it does not have an outcome-based framework to monitor service performance.

Although the Foundation collects extensive service data, it has not used this strategically to determine whether services are meeting client needs or improving access.

In addition, the Foundation has not used its role as service funder to lead sector-wide improvements. While it has funded pilot programs and research on gambling treatment, it has not scaled up these initiatives across the state.

This chapter discusses:

4.1 Outcome-based performance management

Over the past eight years, the Foundation has developed tailored responses to better meet the needs of specific at-risk groups. These include programs for:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples

- CALD communities

- people experiencing gambling harm who also suffer from co-occurring conditions, particularly mental illnesses.

Similar to the prevention services, all treatment programs have output-based performance indicators, such as the number of counselling hours delivered. Gambler's Help Local has client-level outcomes measures, such as indicators of a client's mental health status. However, the response rates for the client-based outcomes data have been low. This means the Foundation has limited ability to understand whether these programs are reducing gambling harm.

Despite having collected extensive service data, the Foundation has not used this strategically to inform its service performance. As a result, the Foundation does not know whether its treatment services are effective overall.

4.2 Providing service choices for clients

The three main service streams— Gambler's Help Local, Gambler's Helpline and Gambling Help Online— remain largely independent from each other. This means that clients cannot move easily between them to access support in a way that best meets their needs.

This is despite a 2013 service review by the Foundation pointing to the need to integrate the three streams to provide a seamless service for people seeking help.

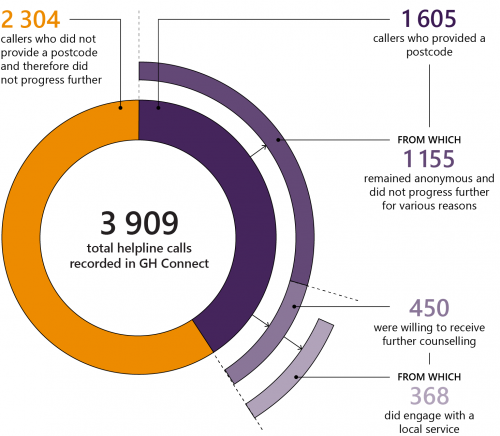

GH Connect is the Foundation's web–based data entry and reporting system.

In 2015, the Foundation developed GH Connect to record client information centrally. Gambler's Helpline and Gambler's Help Local can now share client information. However, Gambling Help Online is a national service that uses a different system and remains disconnected from other Gambler's Help services.

The Foundation advised us that it is working with the other states and territories to integrate the online and Victorian systems.

Responding to client needs

The Foundation has not systematically tested the efficacy of its service streams in meeting clients' needs

The Foundation's approach to treatment assumes that clients prefer face-to-face counselling, and that telephone and online services are for brief interventions or providing information.

However, the Foundation's existing service data suggests that Gambling Help Online and Gambler's Helpline have some advantages over Gamblers Help Local. They offer services:

- at all hours

- remotely, where face-to-face services are not easily accessible

- that avoid the stigma that may be stronger when one has to face another person.

For example, national data from Gambling Help Online in 2019–20 demonstrated 36.1 per cent of service usage occurred between 7 pm and midnight, outside of traditional office hours.

Gambler's Help Local services ask clients about their access preferences—such as the suitability of their opening hours and the accessibility of the local offices. However, these services are not required to ask whether clients prefer services delivered online or by telephone.

We interviewed managers of four Gambler's Help Local providers who confirmed that they do not refer clients to telephone and online services even where it may better suit them, such as those needing to access support after hours or from a distance.

Testing telehealth treatment services

During the COVID–19 pandemic, the Foundation has supported Gambler's Help Local to transition face-to-face counselling services to telehealth. Some providers have also shifted their service times beyond the traditional 9 am to 5 pm offering.

During the pandemic period, Gambler's Help services delivered more counselling hours. The Foundation reported that, despite a reduction in the number of new referrals, Gamblers' Help Local services delivered an increased number of counselling hours in the last quarter of 2019–20. The Foundation achieved 99 per cent of its annual target for counselling hours delivered, its best result ever.

The Foundation is working with Gambler’s Help services to include telehealth as a standard flexible service delivery offering. It is setting up a telehealth community of practice in early 2021 to help it define what the service will be. This is a positive step.

Integrating peer support from people with lived experience

Since 2015, the Foundation has funded several local peer support programs and initiatives, as shown in Figure 4A. The Foundation has missed the opportunity to ‘scale up’ effective programs to provide a statewide peer support service.

FIGURE 4A: Summary of Foundation-funded programs offering peer support

| Peer support program | Program nature | Availability |

|---|---|---|

|

Peer Connections Program |

Volunteer–based telephone peer support service delivered by Banyule Community Health Service |

Marketed to statewide clients, but awareness of the service and access is limited |

|

Face-to-face peer support |

Pilot in 2018 funded by the Foundation and delivered by Banyule Community Health Service |

Initiated when a client contacts Banyule Community Health Service Gambler's Help provider |

|

Gambling Help Online’s peer chat service |

Free and confidential online chats provided by staff from Gambling Help Online |

Initiated when a client contacts Gambling Help Online and selects the option |

|

ReSPIN Speakers Bureau |

Community-initiated program that recruits, trains and supports speakers to talk about the effects of gambling harm |

On request by any interested organisation. Marketed statewide, but availability depends on resources |

|

Chinese Peer Support program |

Delivered by Eastern Area Community Health |

Initiated when a Chinese-speaking client contacts Eastern Area Community Health |

|

Three sides of the coin |

Storytelling theatre-like performance run by Link Health and Community |

Fee-based performance on request by any interested organisation Marketed statewide, but availability depends on resources |

Note: The Chinese Peer Support program is a small program, serving 33 clients in 2019–20.

Source: VAGO, based on the Foundation's information.

Peer Connections Program

People with lived experience who have recovered from illness or addiction deliver peer support initiatives. Used widely in the mental health and alcohol and other drug sectors, this is an effective way to help people receiving treatment and reduce the stigma associated with illness and addictive behaviours.

The Peer Connections Program started in 2006 as an initiative of Banyule Community Health Service. In 2015, an evaluation of the program found it was effective for both the volunteers providing support and the clients being supported in their recovery journey. The program evaluator identified that it filled a service gap around ongoing support for those recovering from effects of gambling harm.

Despite having run for a long time, only a few clients outside of Banyule Community Health Service access the Peer Connections Program.

The Foundation has promoted the Peer Connections Program through its newsletters and flyers since 2018. While it asked Banyule Community Health Service to develop a strategic plan to expand this service sector-wide, the expansion is unlikely to occur without leadership and further support from the Foundation. Such an expansion would likely require:

- making the Peer Connections Program a standard option for Gambler's Help services on GH Connect

- facilitating referral pathways from other Gambler's Help Local providers to the Peer Connections Program

- promoting the positive impact of peer support more widely

- sourcing and training more peer support workers.

4.3 Programs for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and CALD communities

The Foundation funds counselling and awareness-raising prevention activities tailored to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and CALD communities.

However, there are no formal referral pathways between Gambler's Helpline and Gambling Help Online services and these specialised programs. This reduces potential access and service pathways for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and CALD community members.

Aboriginal Communities’ Gambling Awareness Program

The Foundation's Aboriginal Communities' Gambling Awareness Program has resulted in more Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients accessing the tailored support.

In 2018–19, 556 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander clients accessed the programs. In comparison, there are only 185 such clients a year on average from all Gambler's Help Local providers across the state.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples can also access the Gambling Help Online and Gambler's Helpline services, particularly those who may want to avoid a face-to-face service within their own community. However, there are no screening questions to identify if the user is an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander client, nor is there culturally appropriate counselling within these services for these communities.

Further, there are no referral processes between these mainstream services to the tailored programs. One provider of the Aboriginal Communities' Gambling Awareness Program noted that they have never received a referral from the Gambling Help Online or Gambler's Helpline services. As a result, the Foundation is missing an opportunity to expand access to services for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

CALD community services

Similar to the Aboriginal Communities' Gambling Awareness Program, referral pathways between CALD services and the mainstream Gambler's Help services are unclear.

In October 2020, the Foundation announced that it procured a service provider to deliver statewide, integrated gambling support services for CALD communities. It will continue its existing programs for Chinese, Vietnamese and Arabic-speaking communities.

While the new service will provide counselling, community education and engagement to multiethnic communities, the Foundation advised us that it does not have a strategy on the number of languages or the ethnic groups that the new service supports. Rather, it will depend on the provider's assessment of community need balanced against available resources.

In addition, the Foundation has not outlined how it will improve referral pathways between the mainstream Gambler's Help services and the existing CALD communities’ Gambler’s Help programs.

While expanding services to more CALD communities is desirable, the Foundation and the new statewide hub provider needs a clear strategy, referral pathways and outcomes-based performance measures, as discussed in Section 4.1.

4.4 Supporting people with co-occurring conditions

The Foundation does not have a consistent or systematic process for linking clients with co-occurring conditions to other services.

This poses a risk that a client will only be linked to an appropriate support service if the particular Gambler's Help provider they access has a strong relationship with these services. This is different from a ‘joined-up’ approach, where there are formal referral pathways.

|

People experiencing gambling harm often … |

This means Gamblers' Help services need to … |

But, the Foundation has not … |

|

have co-occurring conditions that also require treatment and support from health and human services |

|

|

In addition, people experiencing gambling harm often first seek treatment from health and human services for a co occurring issue, such as depression or family violence. These treatment sessions could also be used to screen for gambling issues. The Foundation funded a pilot of a screening tool but has not rolled it out to help clients to get early support for their gambling issues.

Lack of clear referral pathways with mental health services

Within Gambler's Help Local

The Foundation's service partners for Gambler's Help Local are social service or community health organisations. They offer a range of services in addition to gambling treatment, such as allied health, homelessness and family violence support services.

We found that these providers all screen new clients for gambling issues, and have internal referral processes to provide person-centred care, regardless of the primary reason they presented for support. Therefore, these providers can support clients with co-occurring conditions, within their range of services.

Integrating Gambler's Help with the state's health and human services

Gambler's Help Local also works with other local services to support clients with co occurring conditions. However, the level of integration between these services depends on the strength of relationships between providers in a local area.

At the system level, the Foundation does not have agreed referral pathways between Gambler's Help Local services and the state's mental health, family violence, and alcohol and other drugs services.

For example, the Foundation does not have a formal agreement or memorandum of understanding with the Department of Health and Department of Families, Fairness and Housing on how gambling services should integrate with its funded services. It does not issue guidelines to providers on how to support clients in transition, such as whether the providers should track if other service providers have taken up the referrals.

In addition, the Foundation has had limited success at partnering with the Department of Health to draw attention to gambling harm as a mental health and wellbeing issue. For example, the Victorian Health and Wellbeing Plan 2019–2023 only mentions gambling once in relation to mental health. This is despite the Foundation providing advice that the plan needs to include gambling harm as one of the public health priorities for healthier lifestyles for all Victorians.