Regulating Gambling and Liquor

Overview

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) was established in 2012 by bringing together the functions and resources of two predecessor regulators. The aim was to create a modern world-class regulator—one that would apply an integrated and risk-based approach to regulation in order to deliver more efficient and effective regulation, and compliance monitoring and enforcement, with a focus on minimising harm.

In this audit, we assessed VCGLR’s licensing and compliance functions, its oversight of the Melbourne Casino, its performance measurement and reporting, and its collaboration with other agencies. We also followed up on our recommendations from two previous audits, Taking Action on Problem Gambling in 2010 and Effectiveness of Justice Strategies in Preventing and Reducing Alcohol-Related Harm in 2012.

In this report, 12 recommendations are made for VCGLR, another is directed to VCGLR and Victoria Police, and a further recommendation is made to the Department of Justice and Regulation.

Regulating Gambling and Liquor: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2017

PP No 226, Session 2014–17

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Regulating Gambling and Liquor.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

8 February 2017

Audit overview

Abuse of alcohol and problem gambling can cause significant harm for individuals, families and the community. Because of this, the government regulates both industries. It controls:

- who can sell alcohol and gambling products

- where people can buy and consume alcohol or gamble

- what alcohol and gambling products may be sold

- how and when alcohol and gambling products may be available.

In general, industry participants must be licensed, and the government's compliance-checking activities seek to ensure that licensees comply with the legislation and conditions of their licences.

The government established the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) in 2012 by bringing together the functions and resources of two predecessor regulators—the Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation (VCGR) and Responsible Alcohol Victoria (RAV). The VCGLR is headed by the chair and commissioners, known as the Commission.

The government's aim was to create a modern world-class regulator—one that would apply an integrated and risk-based approach to regulation—in order to deliver more efficient and effective regulation, and compliance monitoring and enforcement, with a focus on minimising harm.

VCGLR has faced significant challenges since its establishment. Its creation coincided with significant changes in the gambling industry, including Victoria's move to allow venue operators to own and operate electronic gaming machines. This ended the previous duopoly arrangement where two companies owned all electronic gaming machines in Victoria outside the Melbourne casino. VCGLR's budget and staff were reduced by around 30 per cent in the four years from 2012, compared to the resources of RAV and VCGR, which had a combined budget of $41.3 million and staff of around 287.

VCGLR has also lost experience and expertise, with 24 experienced officers departing on redundancy packages offered as part of the Sustainable Government Initiative in 2012, followed by a further 22 redundancies up to mid-2014.

VCGLR inherited staff engagement and cultural challenges, including:

- the second lowest staff satisfaction levels in the Victorian public sector, as measured by the 2012 'People Matter' survey

- 12 industrial and employee relations matters carried over from RAV, including performance management cases and a serious bullying case

- dissent between compliance inspectors and management at the time of VCGLR's establishment over the decision to bring in inspectors from RAV and VCGR at different pay levels and working conditions.

It also inherited information technology (IT) issues relating to the absence of a single IT platform across its liquor and gambling activities, which was not addressed until October 2015. An integrated IT system was originally intended to incorporate around 30 legacy IT systems into a single solution by mid-2014, but it was launched, after significant delays, in December 2016.

In May 2015, the Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation outlined the government's significant concerns about VCGLR's ability to engender community confidence, and requested that the new chair of VCGLR review its capability and performance.

The chair reported to the minister in November 2015 that although VCGLR aspired to be a risk-based regulator, this ambition was either underdeveloped or unrealised in a number of areas of operation, particularly its compliance activities. The chairperson found there was a solid foundation to build on, but also found that VCGLR needed to address the following significant challenges as a matter of priority:

- a lack of leadership stemming from delays in filling the chief executive officer role and an unstable management team

- a critical need to develop a positive and unified workplace culture

- inadequate and poorly implemented information and other systems and procedures

- a lack of integration of gambling and liquor functions, particularly in the compliance division

- the need for greater focus on compliance and enforcement activities relating to:

- regional Victoria

- the supply of alcohol to minors and intoxicated people

- access of minors and intoxicated people to gambling activities

- pressures throughout the organisation due to either resource constraints or possible misalignment of resources.

The chair recommended a number of measures to address these issues:

- building VCGLR's leadership capacity

- addressing serious systemic gaps in the compliance division

- seeking additional budget to establish a presence in regional Victoria

- reviewing and updating people and culture policies and practices

- working better with other regulatory and enforcement bodies such as Victoria Police.

VCGLR has since acted to improve organisational culture and staff engagement, and there has been greater stability in the management team since mid 2015.

The minister's statement of expectations for VCGLR for 2016–17 indicated that it should:

- develop regional hubs to support compliance efforts in regional Victoria

- review standard liquor licence conditions to determine if they are effective and appropriate for minimising harm

- further streamline licensing processes, including those that impose unnecessary duplication on industry

- improve its service and determination times by enabling online licence applications for both temporary and permanent licences

- make the Commission's published decisions available in a form that is modern and more readily searchable

- deliver a modern inspection and compliance IT system to better support risk‑based regulation

- refine its risk-based approach to assessing and determining licence applications

- refine its risk-based approach to compliance activities to appropriately target the supply of alcohol and gaming to minors and the supply of alcohol to intoxicated people

- implement a consistent ongoing formal training program to support compliance inspectors to undertake their role effectively

- develop performance indicators aligned with VCGLR's strategic priorities, particularly harm minimisation, evidence-based decision-making and co‑regulatory activities.

VCGLR took action during 2015 and 2016 to address the issues and recommendations arising from the chair's review and the minister's statement of expectations. This included undertaking additional assessments of priority activities and seeking additional funding from government to establish a regional presence.

Against this background, in this audit we assessed VCGLR's licensing and compliance functions, its performance measurement and reporting, and its collaboration with other agencies. We also followed up on our recommendations from two previous audits, Taking Action on Problem Gambling in 2010 and Effectiveness of Justice Strategies in Preventing and Reducing Alcohol-Related Harm in 2012.

Conclusion

VCGLR's plans and actions to further develop its risk-based approaches to licensing and compliance are largely sound, and its recent focused attention to improving the way it manages, develops and deploys its regulatory staff, particularly compliance inspectors, is encouraging.

However, these actions are not yet complete and the scale of required reform is significant, meaning that much work remains for VCGLR to become a fully effective regulator.

Ongoing challenges in merging the people, systems and cultures from VCGLR's two predecessor regulatory bodies, along with the lack of a sufficiently risk-based approach, have precluded VCGLR from fully realising the benefits expected when creating a single regulator.

These significant shortcomings continue to reduce assurance that VCGLR's efforts are adequate to protect the Victorian community from the harms associated with the misuse and abuse of liquor and gambling.

To this end, VCGLR also needs to improve the way it measures and publicly reports on its performance to provide genuine insight into its effectiveness as a regulator in minimising harm, and in ensuring the integrity of the liquor and gambling industries.

Findings

Licensing

VCGLR has made limited progress over the past two years in reorganising the licensing division, training staff and providing improved guidance material to start moving towards a more risk-based approach to licensing activities.

Much work remains and weaknesses in VCGLR's approach mean it still cannot demonstrate that it properly examines and assesses all licensing applications in line with legislative provisions before approving them. These weaknesses are more significant for liquor applications and arise because VCGLR largely accepts the information provided to it by these applicants at face value. It relies heavily on both the honesty of applicants and the diligence of Victoria Police and potential objectors to raise issues about the suitability of applicants, amenity issues or social harms associated with these applications.

The provisions of the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 provide some basis for VCGLR to rely on the information submitted by applicants and the absence of objections when deciding on licence applications. However, this may not be sufficient to meet the legislative intent for VCGLR to minimise harm and prevent criminal influence and exploitation. We identified instances where VCGLR granted licences without fully identifying and assessing the suitability of applicants and their associates, including cases where applicants had not provided complete information on their associates and past criminal convictions.

VCGLR has recently acted to address weaknesses in its quality assurance for licensing processes and needs to continue its work developing a more robust, risk‑based approach to scrutinising applicants.

Compliance

VCGLR has not adequately monitored compliance with gambling and liquor legislation.

Compliance activities are not sufficiently risk based because VCGLR has focused on meeting a target number of inspections, rather than directing inspections to where noncompliance has a high risk or high potential for harm. This approach to compliance does not support the legislative objectives for harm minimisation.

VCGLR has not adequately managed its compliance monitoring functions due to longstanding serious and systemic weaknesses in the design and operation of its compliance activities. Key issues include:

- inflexible allocation of resources to compliance activities based on factors other than risk

- a management approach and culture focused on meeting quotas, which encourage superficial inspection activities rather than activities to address harms

- inadequate guidance and training for inspectors

- unreliable data about liquor and gambling inspections.

VCGLR has identified and started to address many of these issues since late 2015, and its proposed actions to better organise and train its inspectors and target its activities based on relevant data and indicators of risk are reasonable. However, these actions are not yet sufficiently developed for us to assess whether they will improve the effectiveness of VCGLR's compliance activities in minimising harm and protecting the community.

Casino supervision

VCGLR is responsible for regulating and monitoring the Melbourne casino. It has acted to address the lack of a coherent organisation-wide approach to casino supervision across its licensing and compliance functions. However, its compliance division has not applied a level of focus on the casino that reflects its status and risk as the largest gaming venue in the state and its approach has lacked continuity.

VCGLR's predecessor operated with a team solely focused on supervising casino operations. Instead, VCGLR rotates all compliance inspector teams through the casino, but it has not supported them with adequate training, guidance and consistent management oversight.

As a result, VCGLR has not paid sufficient attention to key areas of risk in the casino's operations, such as detection of people excluded by Victoria Police, responsible gambling and money laundering. VCGLR has recognised these issues and has taken action to address this loss of expertise. It is now moving to establish a dedicated casino team.

Reporting on performance

VCGLR's publicly reported performance information provides limited insight into its effectiveness in meeting legislative objectives relating to harm minimisation. VCGLR largely measures and publicly reports on activity rather than its effectiveness or impact. It includes some information in its annual report on actions relating to its effectiveness. However, its emphasis on counting activities such as the number of compliance inspections has encouraged operational behaviour that focuses on matters with little relevance to, or impact on, harm minimisation.

VCGLR has improved its internally reported performance measures by introducing indicators that seek to measure the impact and effectiveness of its regulatory activities. It is now recording the proportion of venues with a previous breach found to be in breach on a subsequent inspection, and changes in the number of specific breaches following a targeted education campaign.

Reporting publicly on the results of these measures would provide more valuable and meaningful insight to Parliament and the community on the impact of VCGLR's activities, rather than the measures it currently reports on.

Relationships between the agencies

VCGLR and the Department of Justice and Regulation (the department) have worked cooperatively to implement new policies for both the gambling and liquor industries, including the collection of wholesale alcohol sales data. VCGLR also has formal and informal relationships with Victoria Police that have led to effective information sharing, however there is scope to broaden this relationship to better coordinate enforcement activities.

VCGLR has also taken steps to strengthen its engagement with a range of other regulators and agencies including VicRoads, AUSTRAC, local government, and agencies involved in the investigation of organised crime.

Implementing past VAGO recommendations

VCGLR, the department and Victoria Police have made progress in addressing the recommendations made in our two previous audits.

There is still work to be done by all three agencies, including development of a joint enforcement strategy for VCGLR and Victoria Police. The department has developed an evaluation framework for alcohol-related strategies but has not yet used it to assess strategies such as the overall success of the freeze on issuing late-night liquor licences in some inner-city municipalities.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation:

- amend its liquor licensing process to:

- require applicants to provide evidence to show that all directors and associates have been disclosed

- document its assessments against all relevant legislative considerations when determining applications, including applicant suitability, amenity issues, and risks of misuse and abuse of alcohol (see Sections 2.3.1 and 2.3.2)

- undertake ongoing checks of liquor licensees to ensure company changes have been disclosed, in line with the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 (see Section 2.3.1)

- improve its guidance on assessment of licence applications, particularly for uncontested applications, and ensure licensing officers use this guidance (see Section 2.5.1)

- complete implementation of the licensing risk-based model by developing and implementing:

- a set of risk indicators

- checklists containing triggers for the escalation of applications within or between teams

- a risk matrix to be considered through the determination phase (see Section 2.2.1)

- develop principles or guidance for assessing net detriment and report transparently against them in decisions on applications for electronic gaming machines (see Section 2.4.2)

- broaden its management reporting on licensing activities beyond the speed of processing applications to include quality indicators (see Section 2.6.2)

- conduct robust data integrity checks across all divisions, particularly when relying on data for reporting purposes (see Section 3.2.3)

- continue to revise the risk-based approach to compliance to ensure better targeting of compliance activities (see Section 3.3.1)

- complete its quality assurance framework for compliance, and ensure it focuses on key divisional processes that contribute to the targeting and quality of inspections (see Section 3.3.2)

- continue to roll out its training and ensure there is regular, ongoing training for compliance inspectors (see Section 3.3.2)

- complete its planned actions to improve the supervision of casino operations (see Section 4.2.4)

- work the Department of Justice and Regulation to improve the quality of its publicly reported performance measures to focus on the outcomes and impact of its work (see Section 5.2.1).

We recommend that the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation and Victoria Police:

- develop a comprehensive collaborative enforcement strategy to more efficiently and effectively target harms associated with licensed premises (see Section 5.4.2).

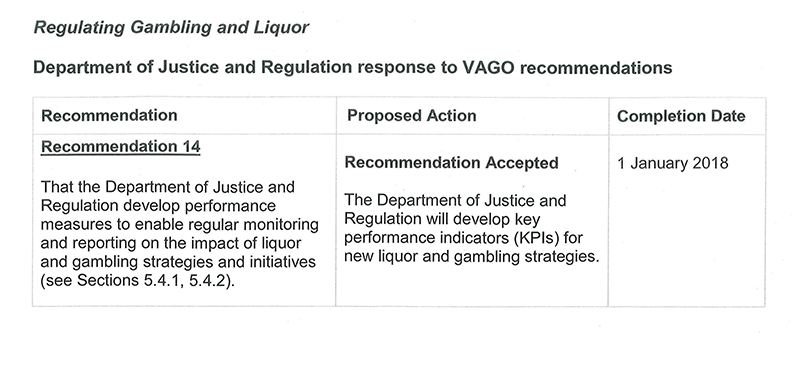

We recommend that the Department of Justice and Regulation:

- develop performance measures to enable regular monitoring and reporting on the impact of liquor and gambling strategies and initiatives (see Sections 5.4.1 and 5.4.2).

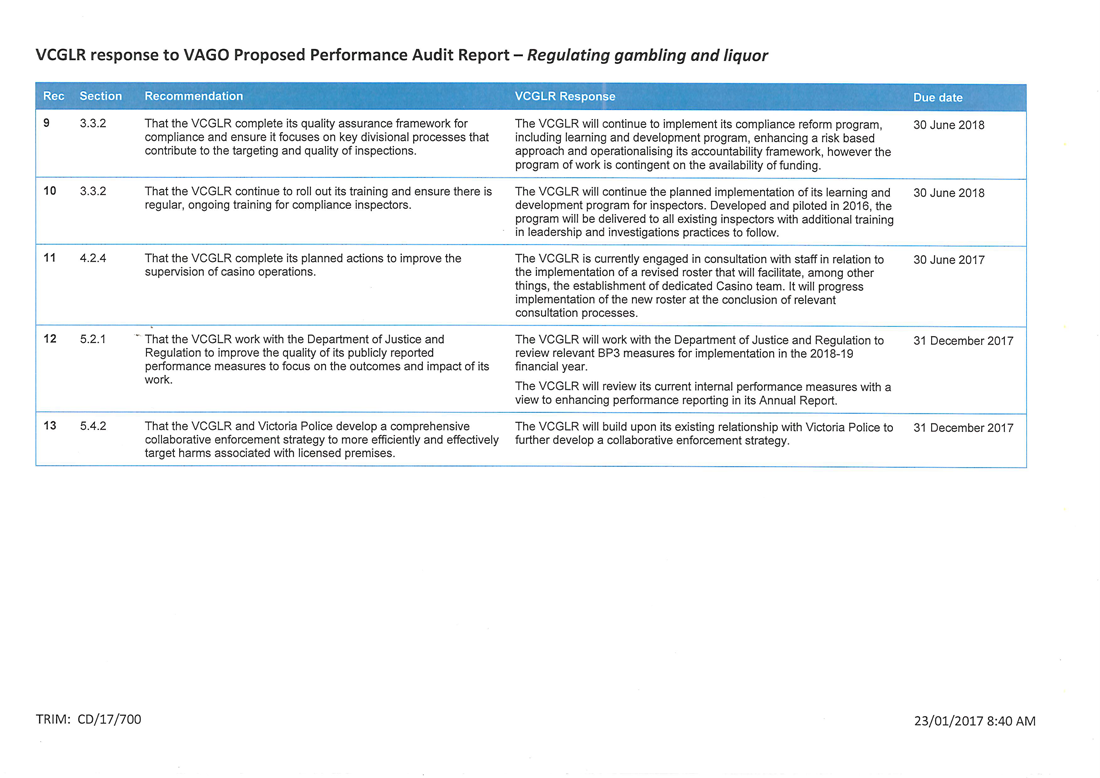

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with the Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation, the Department of Justice and Regulation and Victoria Police, and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

All agencies responded and accepted our recommendations. VCGLR provided a detailed action plan on how it will address our recommendations, although noted that its ability to fully action all recommendations is dependent on the availability of funding.

1 Audit context

1.1 Introduction

The social and economic lives of many Victorians include consuming alcohol and participating in gambling activities. About 75 per cent of the population gamble at least occasionally, and about 80 per cent drink alcohol regularly. The alcohol and gambling industries employ over 130 000 people in Victoria, and both are important parts of our tourism industry.

In 2015–16, Victorians' expenditure on gambling activities (player loss) was more than $5.8 billion. Gambling in Victoria includes sports betting and wagering, 30 000 electronic gaming machines (EGM), Keno, lotteries, minor gaming (such as bingo, lucky envelopes and raffles) and Melbourne's casino.

The Victorian Government collected $1.9 billion in taxation and licence fees from liquor and gambling activities in 2015–16.

1.2 Harm from gambling and alcohol

Both the gambling and liquor industries have a high economic and social impact on the community. The misuse or abuse of gambling and alcohol can have serious negative impacts for individuals, their families and friends, and the wider community. These impacts include street and domestic violence, injuries and fatalities associated with vehicle accidents, depression, theft and fraud to support gambling and alcohol addiction, neglect of family, the loss of family assets and income, and medical conditions associated with alcoholism.

Gambling and alcohol harm have a financial cost to the community. Alcohol-related harm may include violence, hospital admissions and car accidents, while the negative impact of problem gambling can be more hidden and may include family violence, child neglect and self-harm.

While no Victoria-specific data is available, studies have estimated the cost of alcohol abuse in Australia to be in excess of $14 billion per year and the cost of problem gambling to be almost $5 billion per year.

The population is drinking more alcohol over a longer period than previous generations. Some recent data on alcohol consumption in Victoria shows:

- about 42 per cent of Victorians will drink more than four standard drinks on a single occasion—in the 18 to 24 age group, this rises to about 75 per cent of men and 60 per cent of women

- in2010, over 1200 deaths in Victoria were directly attributable to alcohol, and about 2 per cent of hospital admissions were related to alcohol consumption.

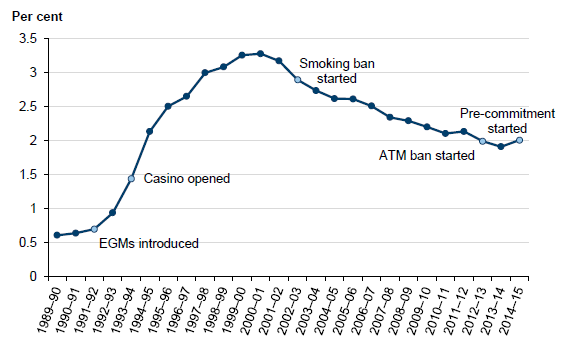

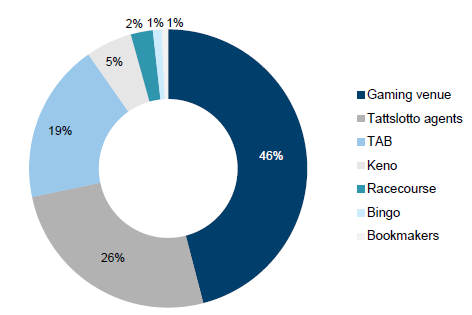

Gambling in Victoria has become increasingly common over the last 25 years. In 2014−15, Victorians lost on average 2 per cent of their household disposable income on gambling. Figure 1A shows a steep increase following the introduction of EGMs in 1992 and the opening of Melbourne's casino in 1994. More than half of Victorians' annual gambling expenditure (loss) is spent on EGMs.

Figure 1A Gambling expenditure as a percentage of household disposable income

Note: The pre-commitment scheme enables players to track the time and money they spend on EGMs and pre-commit a time or dollar amount if they choose to do so.

Source: VAGO, based on Australian Gambling Statistics, 32nd edition.

The Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation and the Department of Justice and Regulation (the department) jointly funded a 2014 study on the prevalence of gambling, which found that about 0.81 per cent of the population, or 35 563 adult Victorians, are problem gamblers.

1.3 Gambling and liquor regulation in Victoria

Government regulation of gambling and liquor is important to support the economic and social benefits of alcohol and gambling, while minimising harm for individuals, businesses and the community. Regulation also helps to ensure the integrity of the participants and practices involved in providing gambling activities and alcohol to the community.

1.3.1 Legislative framework

In Victoria, alcohol and gambling are primarily regulated by the following legislation:

- Liquor Control Reform Act 1998(LCRA)

- Gambling Regulation Act 2003 (GRA)

- Racing Act 1958

- Casino Control Act 1991

- Casino (Management Agreement) Act 1993.

The government regulates these activities by controlling:

- who can sell alcohol and gambling products

- where alcohol and gambling may be sold and consumed

- what alcohol and gambling products may be sold

- how and when alcohol and gambling products may be available.

A licence must be granted to operate a liquor or gambling venue, and compliance activities seek to ensure that licensees comply with the legislation and conditions of their licence.

The regulatory remit is wide, and covers businesses, individuals, products, premises and systems involved in the provision of gambling and alcohol to the community.

Licences in Victoria

There are around 21 000 liquor licences in Victoria—the range of licensed venues includes traditional pubs and clubs, restaurants and cafes, bars, packaged liquor outlets, wholesalers, and wine and beer producer licences. Organisers of one-off events such as music festivals must also apply for a temporary liquor licence.

There are about 500 venues that have both liquor and gaming licences. However, the largest number of gambling licence applications come from employees of the gaming industry, certain types of casino employees and associates of EGM venue operators.

Figure 1B lists the number of gambling and liquor licence applications finalised since 2012–13.

Figure 1B

Licensing applications finalised by year

2012–13 |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Liquor applications |

16 101 |

16 014 |

15 873 |

15 776 |

Gambling applications |

9 920 |

9 784 |

10 767 |

7 810 |

Total applications |

26 021 |

25 798 |

26 640 |

23 586 |

Source: VAGO.

Crown Casino is the only licensed casino in Victoria and has a contract to operate until 2050. It is the only venue in Victoria permitted to offer table games such as roulette, poker, blackjack and baccarat. The casino has around 540 gaming tables, 200 automatic table games and 2 628 EGMs. This makes Crown Casino the eleventh‑largest casino in the world.

Gaming industry employees whose jobs involve functions related to the integrity of gaming machines or restricted monitoring units must be licensed for that purpose. Casino employees who conduct or supervise gaming or betting, or monitor the movement, exchange or counting of cash or chips, and security and surveillance staff must also hold a licence.

Sports organisations can apply for approval to become a sports controlling body to enable them to participate in the monitoring of betting on their sport. When a sports organisation becomes a sports controlling body, they enter into agreements with betting providers to receive a share of the revenue betting providers earn when offering betting opportunities on their events.

Betting providers cannot offer bets on events without an agreement in place with a sports controlling body. Under these agreements sports controlling bodies can access information from betting providers on who is placing bets on their sport, to help them monitor compliance with integrity systems. Sports organisations that are approved sports controlling bodies include the Australian Football League, Tennis Australia and Bowls Australia.

1.3.2 Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) began operating in February 2012. It is an independent statutory authority that regulates Victoria's liquor and gambling activities.

The VCGLR's chair and commissioners—known as the Commission—are appointed by the Governor in Council, on the recommendation of the minister. The current chair was appointed in May 2015.

The commissioners perform statutory decision-making under gambling and liquor regulation. The commissioners also perform the functions that a board would perform in a public sector body—they are collectively accountable to government for the organisation's overall strategy, governance and performance.

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation Act 2011(the VCGLR Act) sets out its functions and responsibilities, including:

- licensing activities—approval, authorisation and registration—under relevant Acts

- informing and educating the public about VCGLR's regulatory practices and requirements

- promoting and monitoring compliance

- detecting and responding to contraventions of gambling and liquor legislation

- advising the Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation on the Commission's functions and the operation of gambling and liquor legislation

- ensuring that government policy on gambling and liquor is implemented.

The key purposes of the Casino Control Act 1991 are to ensure that gaming in casinos is conducted honestly, and that the management and operation of casinos is free from criminal influence or exploitation. VCGLR's remit for regulating the Melbourne casino is wide ranging and includes approving some suppliers, new activities such as automatic table games, rule changes and the layout of the gaming floor. VCGLR is also required to conduct a review into the casino operator and licence every five years. The most recent review was completed in June 2013.

VCGLR took on the responsibilities of its two predecessor regulatory bodies—the Victorian Commission for Gambling Regulation (VCGR) and Responsible Alcohol Victoria (RAV), a business unit of the former Department of Justice. The new entity was formed with the intention of providing Victoria with a modern, world-class regulator that could deal with both liquor and gambling matters, particularly for the compliance role.

VCGLR is a statutory body within the department's portfolio. It is accountable to the Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation, and is obliged to comply with the minister's directions.

VCGLR has authority for all licensing activities and holds public hearings on matters such as the approval of proposed gaming premises or requests for increases to numbers of EGMs. It also holds hearings on contested liquor licences, disciplinary actions and reviews of decisions made by a single commissioner or VCGLR staff.

Compliance inspectors

VCGLR has compliance inspectors who are appointed by the chair under the VCGLR Act. Before appointing an inspector, the chair must be convinced that the person is competent to perform the role and of good repute.

Compliance inspectors monitor licensed gambling and liquor premises throughout Victoria by inspecting licensed venues. This involves visiting a venue to ensure it is complying with either the LCRA or the GRA, or both for gambling venues. Compliance inspectors are located at the Melbourne casino 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to monitor the integrity of the casino's operations.

Compliance inspectors have the power to:

- enter and inspect licensed premises

- request that licensees and their staff answer questions and provide information, documents, records and equipment

- seize items as evidence

- request proof of age and seize liquor from minors

- issue infringement notices.

VCGLR's compliance inspectorate is based in Melbourne and is made up of about 40 operational inspectors divided into eight teams. Currently, each team is responsible for conducting inspections in a number of metropolitan local government areas and in a regional area of Victoria.

VCGLR's regulatory approach

VCGLR describes itself as a risk-based regulator. A risk-based regulator makes informed choices on how it allocates the resources dedicated to its core activities and functions by assessing the risk level. For example, a risk-based approach would apply more effort and resources to assessing a liquor licence application for a late-night pub than for a cafe that closes at 5pm.

VCGLR's regulatory approach is based on five principles:

- risk-based—using a risk-based strategy to guide decisions, priorities and use of resources in discharging statutory functions

- proactive—assessing the environment to detect, proactively manage and dedicate more resources to emerging issues

- collaborative—finding opportunities to partner, collaborate and share information with other co-regulators and industry

- transparent—giving industry, the community and other regulatory partners a clear understanding of what to expect from VCGLR, its regulatory approach and its decision-making

- targeted—following a targeted enforcement approach that involves an escalation of sanctions, in accordance with the severity of the breach or risk posed to the community.

Difficulties with the establishment of VCGLR

Establishing VCGLR and bringing together diverse regulatory functions was a major undertaking in a time of intense change. In its first 12 months, VCGLR staff were relocated to new premises and a new governance framework and operating environment were established, requiring the rapid development of integrated processes and systems. Additionally, there were a number of major gaming and liquor projects and activities taken on by the new organisation. A number of foundation pieces of work were also commenced including the development of strategic priorities, corporate values, a focus on business process improvement and the development of a regulatory framework.

Budget and staff issues

VCGLR has faced budget reductions since it was established. The predecessor organisations—VCGR and RAV—had a combined budget of $41.3 million in 2010−11 and around 287 staff members. In contrast, VCGLR's budget in 2016−17 is just under $31 million and its staffing is 206 full-time equivalent staff members. This equates to about a 30 per cent reduction in both staff numbers and in its budget in real terms. In 2016−17 VCGLR received supplementary funding of $1.5 million from the department to meet operational requirements. This additional funding is for one year only and is not recurrent.

VCGLR was given a target to reduce 24 positions as part of the Sustainable Government Initiative in 2012. VCGLR awarded voluntary departure packages based on length of service, which led to 24 experienced officers departing. A reduction in base funding from 2012 caused VCGLR to restructure, and a further 22 staff were made redundant in June 2014.

VCGLR also inherited 12 outstanding industrial relations and employee matters from RAV—six performance management cases, four WorkCover cases, one return‑to‑work case and one serious bullying case, which resulted in a major investigation.

While the merger of RAV and VCGR should have created some cost efficiencies, VCGLR's establishment coincided with a range of industry changes that had to be rolled out or continued by the regulator. This included implementing Victoria's move to allow venue operators to own and operate EGMs, ending the duopoly arrangement that existed previously—where two companies owned all EGMs in venues other than the Melbourne casino—and implementing a new EGM monitoring licence which required the development of new processes and system changes.

When VCGLR was first established, the satisfaction level of the merged staff was the second lowest in the Victorian public sector, as measured by the 2012 'People Matter' Survey. As a result, VCGLR created improvement plans, and VCGLR's staff satisfaction has increased to now be generally similar to comparable agencies.

When VCGLR was established, inspectors were brought in from RAV and VCGR at different pay levels and working conditions. The process to align these has created dissent between compliance inspectors and the management of the division. Tensions remain, and VCGLR's proposal for new roster arrangements to provide greater flexibility in deploying inspectors at higher risk times is yet to be agreed on by staff and management.

Information technology issues

When VCGLR was established, it did not have a single information technology (IT) platform. Liquor systems ran from the department's IT platform, and the VCGR's IT platform was retained for gambling matters. VCGLR sought to integrate the IT platforms using the department's IT provider. However, it was not until October 2015, after VCGLR hired its own in-house technical experts, that it was able to operate from a single IT platform.

VCGLR's IT issues have been further compounded by the issues it has faced with its IT system LaGIS (liquor and gambling information system). LaGIS was originally intended to incorporate about 30 IT systems, including VCGLR's internet and intranet platforms. The contractor was unable to deliver the planned system, and the scope of the project has now been significantly reduced to incorporate only three IT systems used in the compliance division. The system suffered a range of delays and was rolled out in December 2016.

Review of VCGLR during 2015 and ministerial expectations

In May 2015, the Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation requested that the incoming chair of VCGLR review its capability and performance.

The minister outlined the government's significant concerns about VCGLR's ability to make the community feel confident that Victoria has an effective regulator for gambling and liquor industries. These concerns included:

- ongoing absence of a permanent chief executive officer (CEO)

- the need to develop a positive and unified workplace culture and integrate gambling and liquor functions to create a truly integrated regulator

- a significant decline in compliance and enforcement activities, particularly in regional Victoria, relating to harms such as the supply of alcohol to minors and intoxicated persons and allowing minors and intoxicated persons to gamble

- delays in delivering LaGIS.

The minister asked that the review focus on how VCGLR could more effectively enforce and ensure compliance with the legislation, including in regional Victoria, minimise the harm from problem gambling and the misuse and abuse of alcohol, and better engage with industry and community stakeholders.

The chair completed his review in November 2015 and provided a report to the minister. The report identified that although VCGLR aspired to be a risk-based regulator, this ambition was either underdeveloped or unrealised in a number of areas of operation, particularly in its compliance activities. The chair found that there was a solid foundation to build on, but also found that VCGLR needed to address significant challenges as a matter of priority including:

- a lack of leadership stemming from the lengthy time taken to fill the CEO role, an unstable management team, and a past lack of cohesion in the management team—the first chair was in the position for less than a year, the inaugural CEO was in the role for just over two years, and the senior executive team had undergone considerable change throughout the three years of VCGLR's operation, with people serving in acting positions for extended periods

- a critical need to develop a positive and unified workplace culture

- inadequate and poorly implemented systems and procedures, which undermined the quality and efficacy of accountability and reporting mechanisms

- a lack of integration of gambling and liquor functions, particularly in the compliance division

- the need for greater focus on a range of compliance and enforcement activities, particularly in regional Victoria and in relation to the enforcement of prohibitions on supplying alcohol to minors and intoxicated persons and allowing minors and intoxicated persons to gamble

- pressures throughout the organisation due to either resource constraints or possible misalignment of resources

- inadequate IT systems, due in large part to the significant delays in the delivery of the LaGIS project.

The chair recommended a number of actions including building VCGLR's leadership capacity, addressing serious systemic gaps in the compliance division, seeking additional budget to establish a presence in regional Victoria, finalising the LaGIS system, reviewing and updating people and culture policies and practices, working better with other regulatory and enforcement bodies such as Victoria Police, and having greater input into decision-making by the department and minister on Budget Paper 3 performance measures.

The minister's statement of expectations for VCGLR for 2016–17 indicated that it should:

- develop regional hubs to support compliance efforts in regional Victoria

- review standard liquor licence conditions to determine if they are effective and appropriate for minimising harm

- further streamline licensing processes including those that impose unnecessary duplication on industry

- improve its service and determination times by enabling online licence applications for both temporary and permanent licences

- make the VCGLR's published decisions available in a form that is modern and more readily searchable

- deliver a modern inspection and compliance IT system to better support risk‑based regulation

- refine its risk-based approach to assessing and determining licence applications

- refine its risk-based approach to compliance activities to appropriately target the supply of alcohol and gaming to minors and the supply of alcohol to intoxicated persons

- implement a consistent ongoing formal training program to support compliance inspectors to undertake their role effectively

- develop performance indicators aligned with VCGLR's strategic priorities, particularly harm minimisation, evidence-based decision-making and co‑regulatory activities.

VCGLR took action during 2015 and 2016 to address the issues and recommendations arising from the chair's review and the minister's statement of expectations. This included undertaking additional assessments of priority activities and seeking additional funding from government to establish a regional presence.

In this report, we looked at VCGLR's progress on a number of these issues and highlight outstanding gaps.

1.4 Other bodies

1.4.1 Department of Justice and Regulation

The department's Office of Liquor, Gaming and Racing (OLGR) is responsible for gambling and liquor regulation policy and provides advice to the Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation.

The OLGR is involved in major gambling and liquor projects. It is currently undertaking reviews of the LCRA and the regulatory arrangements for the operation of EGMs. It has recently rolled out the pre-commitment scheme for EGMs, which allows gamblers to set limits on the time or money they spend and track their gaming machine activity.

VCGLR is included in the department's 'Industry Regulation and Support' output group for the purposes of Budget appropriations and reporting. VCGLR must negotiate its Budget Paper 3 performance measures with OLGR. To request new funding, VCGLR must go through OLGR and the department's internal processes.

1.4.2 Victoria Police

Victoria Police has a number of roles in liquor regulation. Victoria Police has three Divisional Licensing Units located in Melbourne, Stonnington and Geelong. It also has Police Service Areas (PSA) in each local government area. The commander of each PSA is responsible for reviewing liquor licence applications in the area and can object on the basis of detriment to the amenity of an area. The Chief Commissioner of Victoria Police may also object on any grounds he or she thinks fit.

Victoria Police also undertakes targeted liquor licensing compliance and enforcement activities via Taskforce Razon and has a dedicated liquor licensing prosecutions team known as the Liquor Licensing Unit.

Victoria Police signed a memorandum of understanding with VCGLR in October 2015. This agreement gives VCGLR access to Victoria Police data and sets out a framework for cooperation.

Victoria Police undertakes a range of activities related to gambling including investigating illegal gambling, and gathering and assessing intelligence relating to the integrity of racing and other sporting activities where gambling is involved. However, this work has little impact on or crossover with the activities of VCGLR.

1.4.3 Local councils

Local councils play an important role in the licensing process for liquor and gambling venues. They have the power to grant or reject planning permits. A licensee must already have a planning permit for the venue when applying for a liquor licence.

Councils also have a role in VCGLR's processing of applications for licences. VCGLR must notify the relevant council when it receives a new liquor licence application or variation of an existing licence. The council has 30 days to object to the granting of a new liquor licence, or a variation or relocation of an existing licence for an objection to be considered by VCGLR.

Under the LCRA, a local council can object on the grounds that the licence would detract from the amenity of the area around the venue or premises. Councils can also object to packaged liquor or late-night packaged liquor licences only, on the grounds that they would be conducive to or encourage the misuse or abuse of alcohol.

VCGLR is not required to notify a local council in the case of an application for a major event licence or a limited licence or transfer.

1.5 Why this audit is important

Alcohol and gambling provide a range of positive economic and other benefits to the community. However, the misuse and abuse of gambling and alcohol can have significant harmful effects on individuals, families and the community, and both industries need to be regulated effectively to minimise these risks of harm.

1.6 What this audit examined and how

Our objective was to examine the effectiveness and efficiency of VCGLR in regulating gambling and liquor activities. To assess this objective, we examined whether:

- VCGLR's licensing and compliance activities adequately fulfil legislative requirements

- VCGLR works effectively with the department and Victoria Police to regulate gambling and liquor activities

- VCGLR effectively monitors, evaluates and reports on performance to demonstrate efficient achievement of intended outcomes.

We focused on VCGLR's policies, procedures, systems, data and processes, and examined the relationships between VCGLR and the department and Victoria Police. We also followed up on the recommendations made in our previous audit reports Taking Action on Problem Gambling in 2010 and Effectiveness of Justice Strategies in Preventing and Reducing Alcohol-Related Harm in 2012.

VCGLR, the department and Victoria Police were key sources of information for this audit. We gathered evidence by conducting interviews, reviewing key documents provided by VCGLR, the department and Victoria Police. We also conducted file reviews of licensing applications, analysed VCGLR's compliance data and observed compliance inspections.

We conducted the audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of the audit was $590 000.

1.7 Report structure

The remainder of the report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines VCGLR's licensing methodology, its process for assessing liquor and gambling applications, and the tools it uses to support licensing decisions

- Part 3 examines VCGLR's compliance methodology, its inspections for liquor and gambling applications and, the tools it uses to support compliance activities

- Part 4 examines VCGLR's supervision of casino operations

- Part 5 examines VCGLR's internal and external performance measures and reporting, the actions taken by VCGLR, the department and Victoria Police to address our previous recommendations, and VCGLR's relationships with the department and Victoria Police.

2 Licensing industry participants

The Victorian Commission for Gambling and Liquor Regulation (VCGLR) makes decisions on a large number of gambling and liquor licence applications each year. These include applications for permanent licences, temporary licences, variations and transfers of existing licences, and approval of new directors or nominees.

A robust licensing process is essential for VCGLR to meet its legislative and regulatory objectives of minimising harm and ensuring industry participants are suitable.

This Part of the report examines VCGLR's licensing framework and processes, including guidance and training for decision-makers and quality assurance.

2.1 Conclusion

VCGLR cannot demonstrate that all licensing applications are properly examined and assessed before being approved.

VCGLR has made progress over the past two years in reorganising the licensing division, training staff and providing guidance material to support a move to a more risk-based approach to licensing activities. However, significant weaknesses remain in VCGLR's licensing approach, and this has compromised its achievement of legislative objectives for harm minimisation and for the prevention of criminal influence and exploitation.

2.2 Licensing framework and approach

Since its establishment, VCGLR has made some progress in implementing a risk‑based approach to its licensing functions. It has established a licensing branch structure and an initial triaging process for applications informed by basic risk factors.

VCGLR's documented approach to regulating the gambling and liquor industries emphasises:

- risk-based targeting—analysing the risks presented by individuals and businesses in these industries that may cause harm

- understanding these risks and using them to guide VCGLR's decision-making, priorities and use of resources in discharging its functions.

However, significant work remains for VCGLR before it has a fully risk-based framework to assess applications.

2.2.1 Risk framework for assessing applications

Following VCGLR's creation in 2012, licensing officers continued to only process either liquor or gambling applications, based on their previous roles, with the exception of a small 'dual licensing' team.

In August 2014, the licensing division was restructured into three streams to encourage a more agile workforce and to implement a risk-based approach to licence processing. This stream-based structure was refined in October 2015, with three streams merged into two. Now, one stream deals with low–medium risk applications (Stream 1) and the other stream deals with medium–high risk applications (Stream 2).

Stream 1 staff triage and assign applications based on a risk rating. The risk rating for each application is determined by the type of application. This is primarily based on a risk-based fee structure initially set by government in 2009, to determine the cost of a liquor licence based on risk factors such as late-night hours and patronage. These risk factors have not been reviewed since they were established in 2009, and this model does not incorporate any risk factors specifically related to gambling venues or licence types.

VCGLR's move towards a risk-based model for processing licence applications was based on advice from external consultants and intended to enable active consideration of risk throughout the entire application assessment process. In late 2014, the licensing branch committed to developing risk indicators and implementing an initial risk matrix, with checklists containing 'red flags' for delegates to trigger the escalation of applications within a team or between teams, and a further risk matrix to be considered during the determination phase. A project plan for developing risk indicators was drafted in early 2015, but the project did not progress and the checklists and risk matrixes have not yet been developed.

VCGLR advised us that it intends to continue with this project as part of a broader program of work focused on its regulatory approach but it will take time. The importance of this work was highlighted in January 2015 advice to the acting chief executive officer of VCGLR from the licensing branch director, in the chair's review of VCGLR in late 2015, and in the June 2016 statement of expectations for VCGLR from the Minister for Consumer Affairs, Gaming and Liquor Regulation.

Since the move to a two-stream model, no applications have been escalated between teams, and we found no evidence of applications being escalated within teams in the licensing files we reviewed as part of this audit. This indicates that following the initial triaging of applications, there is no systematic ongoing review of risk as applications progress through the assessment process.

To deal with the high number of low-risk liquor licence applications, different licensing officers are rostered to process correspondence and objections received for these applications. The aim is to process and finalise applications as quickly as possible, to meet VCGLR's 60-day processing benchmark.

However, VCGLR does not systematically review the risk profile of individual applications when it receives the relevant attachments, so it is not possible to determine whether all applications finalised in this manner are low risk or whether VCGLR should escalate some applications for further review before making a decision.

This approach primarily focuses on speed rather than quality, and it is not in line with VCGLR's claimed risk-based regulatory approach.

A risk-based approach optimises the use of available resources. However, VCGLR does not have an integrated information management system that shows how many cases each licensing officer has on hand, or how many applications individual officers have determined across the entire branch.

2.3 Assessing liquor licence applications

VCGLR received about 15 800 liquor licence applications in 2015–16, including new applications, temporary licence applications, variations, transfers and changes to directors for existing licences. The bulk of liquor licence applications—almost 10 000— were for temporary liquor licenses.

VCGLR must assess and determine liquor licence applications in accordance with the Liquor Control Reform Act 1998 (LCRA).

We assessed a sample of 85 liquor licences that were granted between August 2014 and March 2016, to determine whether:

- decisions and the reasons for them were adequately documented

- there was adequate documentation on file to support decisions

- decisions were made in accordance with the legislation.

2.3.1 Consideration of relevant matters

VCGLR's assessment of liquor licence applications does not adequately address the requirements of the LCRA. It does not sufficiently consider the key matters specified in legislation that must be assessed when making a determination for every application, including:

- the suitability of applicants

- the identification and assessment of associates

- the potential impacts on amenity

- the potential for misuse and abuse of alcohol.

The LCRA specifies applicant suitability and amenity and harm issues associated with the granting of a liquor licence as grounds on which VCGLR may refuse to grant an uncontested application.

VCGLR advised that because Victoria Police, local councils and the public can object to an application on any of these grounds, VCGLR considers that when no objection is received it can proceed to grant a licence without needing to document its own assessment of these matters. VCGLR considers that in these circumstances the VCGLR staff member is entitled to assume the granting of the application is in accordance with the LCRA.

This view is not soundly based. The LCRA states: 'It is the intention of Parliament that every power, authority, discretion, jurisdiction and duty conferred or imposed by this Act must be exercised and performed with due regard to harm minimisation and the risks associated with the misuse and abuse of alcohol.'

The LCRA clearly obligates VCGLR to gather and carefully consider evidence on all matters, including 'optional considerations' specified in the legislation, when they are relevant to the decision to grant or refuse a licence. This includes any associated risks or potential harm arising from the misuse or abuse of alcohol.

It is good practice and good public policy for a regulator to make use of all available powers to further the purpose of the legislation and demonstrate that decisions are made in support of policy objectives. Failing to do this undermines confidence that the licensing approach is effective and that decisions are soundly based.

VCGLR's recently obtained advice indicates that licensing determinations should be based on all relevant considerations and not just on mandatory criteria. Specifically, this advice states that:

- VCGLR is required to determine an application by reference to both the grounds for refusal and the objectives of the LCRA.

- Reasons for decisions should refer to the relevant statutory provisions in more detail and identify at the outset the test to be applied, any mandatory considerations and other considerations relevant to the decision. This includes the relevant objectives of the Act under which decisions are made.

The case study in Figure 2A provides an example where VCGLR did not document its consideration of an applicant's initially undisclosed criminal history when recording the reasons for granting the licence application. The decision recorded on this application should have documented VCGLR's assessment of the relevance of this history and the fact that the applicant did not disclose it in his application to its determination on his suitability to hold a licence.

Figure 2A

Case study: Liquor licensing

An applicant applied for a liquor licence but did not initially disclose his history of criminal convictions. Victoria Police lodged an objection to the application based on the lack of information the applicant had disclosed in his application about his criminal history. Following the objection, the applicant provided details of his criminal history to VCGLR, which showed that he had a range of earlier convictions and his most recent criminal conviction was for making a false statutory declaration. Once VCGLR became aware of the applicant's criminal history, Victoria Police withdrew its objection. The applicant also advised VCGLR that he was a current director of two other licensed premises and a former director of two further licensed premises. The applicant was granted a liquor licence. There was no evidence on file that VCGLR asked the applicant for further information or an explanation about his criminal history. In addition, the decision record for this application did not explicitly deal with the relevance of the past criminal convictions and their initial non-disclosure to its assessment of the applicant's suitability. This was despite Victoria Police bringing the issue of the applicant's criminal convictions to VCGLR's attention. Despite having copies of the applicant's criminal history, VCGLR believed there was no evidence on which to question whether the applicant was suitable to hold a licence. Although having a criminal conviction does not preclude an individual from holding a liquor licence, we expected VCGLR to document its examination of these matters as part of its assessment of the applicant's suitability. |

Source: VAGO.

Reliance on information from applicants

VCGLR largely accepts the information provided to it by applicants at face value. It relies heavily on the honesty of applicants and the diligence of Victoria Police and potential objectors to raise issues about the suitability of applicants, amenity issues or social harms associated with applications.

The LCRA specifies applicant suitability as a matter relevant to VCGLR's assessment of liquor licence applications. Under the LCRA, applicants must provide details of their associates when applying for a liquor licence, and this includes the associates of all directors where the applicant is a company. VCGLR provides Victoria Police with a copy of the application. However, VCGLR's assessment processes do not provide sufficient assurance that all directors and associates are declared and sufficiently scrutinised as part of the liquor licensing process.

License application forms require applicants to disclose information on directors and associates. The LCRA makes it an offence for an applicant to provide false or misleading information to the VCGLR, including by omitting material information. This offence and the requirement for applicants to complete a statutory declaration places obligations on applicants to be truthful, and VCGLR is entitled to place some reliance on this when making determinations on applications.

However, VCGLR does not take adequate steps to confirm the accuracy of information provided by applicants. Specifically, it does not require applicants to provide company extracts from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) to support their applications, and it does not routinely conduct its own ASIC searches to verify that all directors and associates have been correctly identified.

We conducted ASIC searches on 19 companies that had been granted liquor licences since 2013, and found that four had either directors or shareholders that had not been disclosed at the time the application was made. This demonstrates that the LCRA's provisions do not ensure the accuracy of information that applicants submit and indicates that VCGLR should not simply rely on the diligence and honesty of applicants.

VCGLR's reliance on self-disclosure by applicants is a significant weakness in its assessment of applicants' suitability. If VCGLR's processes do not ensure that applicants disclose all associates, then resulting checks by Victoria Police will be incomplete and licences may be granted to applicants with unsuitable company directors or associates. Clearly, VCGLR needs to take action to mitigate this risk by requiring applicants to provide evidence to support the information they provide and to be more proactive in checking this information.

VCGLR's view is that requiring all applicants for liquor licenses to submit an ASIC extract would place extra regulatory and financial burdens on applicants. However, the cost of an ASIC company extract is not excessive, and VCGLR has not demonstrated that the additional burden would not be justified. We note that VCGLR requires this information for gambling licence applications.

Further, VCGLR does not have sufficiently robust processes in place to ensure that liquor licence holders comply with obligations to inform it of changes in company directors and associates after a licence is granted.

Unlike most gambling licences, which have expiry dates, liquor licences are granted once and do not expire if the licensee continues to make annual licence renewal payments and is not found to be in serious breach of the LCRA. The LCRA recognises that the ownership, control and associates of liquor licences may change and requires licensees to advise the VCGLR of any changes in directors or associates. These important provisions are relevant to VCGLR's achievement of the objectives of the LCRA.

VCGLR relies primarily on licensees informing it of relevant changes. Compliance inspectors undertaking routine inspections may sometimes pick up changes, although they do not systematically check for changes in directors or associates due to a lack of consistently applied compliance procedures.

VCGLR could better monitor whether company details have changed via random checks of licensees. Alerting licensees to the possibility of being randomly checked would encourage compliance with the LCRA.

2.3.2 Decision records

Decision records are retained on VCGLR's licensing files to document the basis for licensing decisions. To determine whether a robust assessment process was in place, we looked at decision records to assess whether they acquitted applications against all relevant legislative considerations, clearly documented reasons for decisions and were signed by a VCGLR staff member with the appropriate authorisation to make the decision.

Although licensing files were well organised, there were gaps in the quality and content of decision records. The decision records we examined were inconsistent, did not comprehensively address key matters specified in legislation or contain sufficient information to demonstrate why a liquor licence was granted. Analysis of 85 liquor licensing files showed:

- the LCRA was mentioned in only 13 per cent of decision records

- misuse or abuse of alcohol was mentioned in only 16 per cent of all decision records

- it was unclear who had made the decision in 60 per cent of all decision records.

The poor quality of decision records means the VCGLR cannot provide adequate assurance that liquor licence applications are assessed in accordance with the legislation.

VCGLR has acknowledged that its decision records could be more complete. VCGLR recently conducted a quality assurance review, which highlighted issues with decision records for liquor licence applications, and undertook to do more work to improve decision records.

2.4 Assessing gambling licence applications

VCGLR received almost 8 000 gambling licence applications in 2015–16. VCGLR is responsible for administering 18 different types of licences and approvals. A large volume of applications comes from trade promotion lottery permits, modifications to electronic gaming machines (EGM) including new games and systems, new gaming industry employees and associates of venue operators.

We reviewed a sample of 100 gambling applications that VCGLR granted between 2014 and 2016, including from the following types:

- new and renewal gaming venue operator licences

- associate or nominee of gaming venue operator licences

- directors of gaming venues

- gaming industry employees

- casino industry employees

- new and modified gaming machine hardware and game software

- sports controlling bodies.

We reviewed these files to determine whether VCGLR made decisions in accordance with the Gambling Regulation Act 2003 (GRA) and the Casino Control Act 1991, and whether decisions met the objectives of the legislation, including that gaming on gaming machines is conducted honestly and that the gambling industry is free from criminal influence and exploitation.

We also assessed VCGLR's administrative practices to determine whether there was adequate documentation in the files, including whether decisions were appropriately documented.

2.4.1 Licensing gaming venue operators, directors, associates and nominees

Venue operator licences allow an entity to operate gaming machines in Victoria. The licence is granted for 10 years, after which it must be renewed. The GRA specifies that when assessing applications, VCGLR must be satisfied:

- the applicant and associates are of good repute, having regard to character, honesty and integrity

- the applicant has, or has arranged, a satisfactory ownership, trust or corporate structure

- whether any person related to the ownership, trust or corporate structure has a business association with a person who, or body or association which, is not of good repute or has unsatisfactory financial resources

- any person connected to the ownership, administration or management of the operation or business is a suitable person to act in that capacity.

VCGLR typically obtains sufficient information from applicants for gambling licences to enable it to address these matters. The files documenting VCGLR's assessment of applications for gaming licences were in good administrative order and the documentation on the basis for these licensing decisions was generally adequate.

However, we identified an instance where VCGLR's licensing of venue operators and associates did not fully ensure that the legislative objectives of the GRA were met. The case study in Figure 2B provides an example where VCGLR's assessment process was not sufficiently robust to ensure VCGLR fulfilled the objectives of the legislation relating to avoiding criminal influence and exploitation.

Figure 2B

Case study: Gaming venue operator's licence

A key objective of the GRA is to ensure that the management of gaming machines and gaming equipment is free from criminal influence and exploitation. An associate of an applicant for a venue operator's licence (the applicant's husband) stated in the application that his role was to provide financial support and operational assistance in the management of the venue, which clearly indicated that he was a significant investor and ongoing manager of the business. VCGLR's licensing process appropriately identified that the associate had previous business connections with an alleged underworld figure who is excluded from Victorian race tracks and Crown Casino. The matter was referred to the compliance branch for investigation. The compliance branch determined that 'there probably wasn't an issue arising from this association because there hadn't been reports of contact between the alleged underworld figure and the applicant for two years'. This advice appears deficient as it was solely based on a review of publicly available information. There was no evidence on the file that VCGLR:

It is of further concern that VCGLR granted the licence and did not place any conditions on it to deal with the risks associated with this matter. |

Source: VAGO.

In Figure 2B, VCGLR did not properly investigate the relationship between the associate and the alleged underworld figure. This could undermine the objectives of the GRA to ensure that the management of gaming machines and gaming equipment is free from criminal exploitation. VCGLR should properly consider and investigate matters that are central to achieving the objectives of the GRA.

2.4.2 Electronic gaming machines—assessing 'no net detriment'

Gaming venue operators have to apply to VCGLR for approval of additional venues or machines. The GRArequires VCGLR to satisfy itself that the net economic and social impact of its approval will not be detrimental to the wellbeing of the community where the venue is located.

These decisions are made by VCGLR commissioners, rather than being delegated to licensing officers or executive staff. VCGLR provides the commissioners with social and economic impact assessments containing information on key indicators such as unemployment, homelessness and housing stress in the area where the venue is located. The assessments also contain data on the number of gaming machines in the area and the average spend (loss) per head, relative to the statewide average. The content and quality of the social and economic impact assessments has improved, in line with the recommendation made in our 2010 report Taking Action on Problem Gambling.

Applicants try to show in their applications and in hearings in front of the Commission how increasing the number of gaming machines will have a positive impact on the community, for example, by providing increased employment or by the venue making financial contributions to the community. The Commission assesses these factors to determine whether there is 'no net detriment' to the local community as a result of increasing the number of gaming machines.

The GRA does not provide guidance on how the test for no net detriment should be applied. VCGLR has undertaken a number of initiatives to improve the way it assesses no net detriment, including:

- providing information to commissioners during their induction

- holding biannual meetings to discuss the content, style and consistency of VCGLR decision records on gaming

- drafting guidance material for EGM matters.

Despite this, VCGLR still lacks comprehensive guidance for commissioners on how to assess and calculate net detriment. Its draft guidance for assessing EGM matters provides summaries of key points from case law, however there is further opportunity for VCGLR to refine this and provide more comprehensive guidance for commissioners.

In our 2010 report Taking Action on Problem Gambling, we recommended that the former gambling regulator develop principles for assessing net detriment. The former gambling regulator did not accept this recommendation on the basis that it published its reasons for decisions in determinations on its website. It proposed reviewing the format for its written decisions to ensure its reasons were clearly articulated.

Since our 2010 audit, and following a 2013 Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal (VCAT) case, the Commission has changed the way it reports on net detriment in its decision records. VCAT stated that a table of likely economic and social benefits and disbenefits, with comments on the weighting to be given to each factor, would be a useful way to transparently deal with the no-net-detriment test.

The Commission's recent decision records show a focus on no net detriment, and it has been clear in listing the factors it takes into consideration and the relative weighting that it gives each factor when making a decision.

However, there is scope for the Commission to further improve its decision records as some stakeholders, in particular local councils, advised that they found it difficult to understand how the Commission reached a position of no net detriment, particularly in areas with high levels of socio-economic disadvantage and a high number of EGMs.

The Commission is also currently reviewing the adequacy of its decision documents, which provides it with an opportunity to clarify the principles for assessing net detriment, strengthen decision-making and develop a transparent framework.

2.4.3 Other gambling licensing decisions

Gaming industry employees and casino special employees

When we reviewed the processing of employee applications, we found that VCGLR receives enough information from applicants to be assured that all legislative requirements have been met. Applicants provide a criminal history check, a credit report and two passport photos to support their application.

VCGLR has a template for licensing officers that directs them to consider all relevant legislative requirements before they approve an application. There was evidence that when issues with suitability were identified, licensing officers undertook further checks, including asking the applicant for more information before granting the licence.

Sports controlling bodies

VCGLR approves sports controlling bodies by assessing whether they have appropriate processes and policies in place to ensure the integrity of betting on their particular sport, and whether they can monitor and enforce their own integrity systems.

We examined the process for approving three applications from sports controlling bodies. We found that the application forms and VCGLR's assessment of them demonstrate compliance with the legislative requirements for approval, and the assessment process was well documented.

New and modified gaming machine hardware and software

VCGLR approves new and changed hardware and software for EGMs using a framework established by the GRA, and Victorian and national standards.

Applications for VCGLR approval of EGM hardware and software must include a recommendation from an approved testing laboratory. These laboratories are nationally accredited, and VCGLR assesses their work using a range of evidence. The laboratories are engaged directly by the manufacturers, and VCGLR has little visibility on the extent of other work performed by these laboratories for the manufacturers.

Our 1998 report Victoria's Gaming Industry: An insight into the role of the regulator commented on fairness issues for players of EGMs and suggested opportunities to improve the level of information made available to players about 'metamorphic games'. These games typically feature players accumulating tokens over multiple games and then reaching a bonus phase, where they receive free games, after accumulating a particular number of tokens.

For most games within this category, the theoretical return-to-player percentage before the bonus phase can be well below the statutory minimum level of return of 85 per cent. This is acceptable given that the bonus feature is an intrinsic part of the game and there is overall compliance with the minimum level of return. However, the electronic game information screen available to players of metamorphic games does not currently disclose information on the extent to which the bonus feature contributes to the overall return to players. There is an opportunity to provide additional information to players on this issue.

2.5 Supporting licensing decisions

With applications being processed and determined by a large number of licensing officers, it is important that VCGLR provide licensing officers with up-to-date, consistent and comprehensive guidance and training.

2.5.1 Online guidelines for licensing staff

The licensing branch of VCGLR launched an interactive online 'Wiki' site in November 2015 to make guidance on licensing processes more accessible and to encourage greater staff engagement. Although this was a positive development, the content on the site is incomplete and inconsistent in style, which reduces ease of interpretation and application.

While guidance is available for contested applications, licensing officers commented that they did not rely on the guidance available and asked a colleague instead.

Where an application is uncontested, we found there was insufficient guidance to assist licensing officers to consider relevant information on matters such as applicant suitability. This could compromise the quality of licensing decisions, as licensing officers may make inconsistent decisions or follow poor practice by not using guidance.

2.5.2 Training licensing officers

Over the last two years, the licensing division has provided training to cross-skill all staff in both gambling and liquor, with the aim of training each person in the area that was unfamiliar (either liquor or gambling).

Although this was a positive step, staff are not yet fully trained and experienced in both areas, because not all licensing officers in Stream 1 process a mix of liquor and gambling applications.

VCGLR's most recent quality assurance process has identified that some staff require further training.