Collecting State-based Tax Revenue

Audit snapshot

Are the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) and the State Revenue Office (SRO) optimising how they collect state-based tax revenue?

Why this audit is important

SRO collects state-based taxes, such as payroll tax and land tax.

The government uses these taxes to fund essential public services, such as education, healthcare, infrastructure, police and public transport.

It is therefore essential that SRO collects tax effectively and efficiently.

Who and what we examined

We assessed if:

- SRO effectively and efficiently collects tax

- DTF effectively oversees SRO's performance.

What we concluded

Despite many positive initiatives in recent years to better meet taxpayer needs, SRO and DTF cannot show that SRO has optimised how it collects tax.

SRO reliably collects the tax it knows about and the amount it collects has increased over the last 5 years.

However, there is a very high likelihood that SRO could collect more tax by better analysing how effectively it is reducing the tax gap, which is the difference between the tax people and businesses owe and what they actually pay.

SRO does not do enough analysis to determine if it is collecting taxes efficiently.

DTF and SRO's set of public performance measures do not give a clear picture of SRO's performance.

DTF's governance of SRO's performance also requires clarification.

What we recommended

We made 6 recommendations to DTF and SRO about:

- optimising tax collection

- improving performance reporting and work practices

- governance of SRO.

Video presentation

Key facts

Source: VAGO.

What we found and recommend

This section summarises our key findings and recommendations. Our complete findings, including supporting evidence, are detailed in the report chapters.

When reaching our conclusions, we consulted with and considered the views of the audited agencies. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

Optimise means to make something as perfect, effective or functional as possible.

The tax gap is the difference between the amount of tax people and businesses owe and what they actually pay.

The State Revenue Office is not optimising tax collection

The State Revenue Office (SRO) reliably collects the tax it knows about. The amount it collects has increased over the last 5 years. But it cannot show it is optimising how it collects tax. This is because it does not:

- regularly consider the tax gap

- sufficiently measure or analyse its costs.

Not regularly considering the tax gap

SRO does not regularly analyse the tax gap to optimise how it collects tax.

The BP3 is the state Budget paper that gives an overview of the goods and services the government funds. Departments and other public entities have performance targets for delivering these goods and services.

One of the Department of Treasury and Finance's (DTF) objectives in the Budget Paper 3: Service Delivery (BP3) is to 'optimise Victoria’s fiscal resources'. SRO provides revenue management and administrative services that contribute to this objective.

This implies that SRO should:

- regularly estimate and analyse the tax gap for its major taxes

- use this information to maximise the amount of tax it collects.

This is because analysing the tax gap can help an agency optimise tax collection by:

- identifying the amount of tax people and businesses owe but have not paid

- assessing the impact of its initiatives to reduce the gap

- prioritising compliance risks to allocate resources.

Voluntary compliance is when a taxpayer voluntarily pays the tax they owe on time without SRO needing to compel them to.

Back-end compliance is when an agency uses investigative tools and methods to detect people or businesses who owe tax but have not paid it.

SRO has a range of ongoing voluntary and back-end compliance initiatives to reduce the tax gap. But it does not regularly assess what the gaps are for its major taxes. This information could be used to inform its annual work program.

As a result, SRO cannot show:

- if and how it is meeting DTF's BP3 objective

- how effective its initiatives to reduce the tax gap are.

It is difficult to accurately calculate the tax gap because:

- tax gaps are made up of unknown amounts that people and businesses do not report

- data may not be readily available.

This means closing the tax gap should not be an explicit performance target. But analysing the tax gap is important because it informs:

- judgements about how effectively it collects tax

- if an agency's targeted initiatives are reducing the gap.

DTF believes that an agency should only regularly analyse the tax gap if the benefits outweigh the costs of conducting it. However, DTF and SRO have not done this cost–benefit analysis.

SRO recognises the value of analysing the tax gap. It last did a tax gap analysis for payroll tax in 2016. This analysis was for the period between 2010–11 to 2014–15.

SRO's analysis showed that the estimated average annual payroll tax gap for this period was about $297 million, or 5.2 per cent of the 2014–15 payroll tax revenue.

SRO has started to analyse the gap for payroll tax again. It also plans to analyse the gap for land tax in 2022–23.

Not sufficiently measuring or analysing its costs

SRO has reduced its costs to collect tax in some areas. But its total costs have increased over time.

SRO does not analyse:

- its spending compared to previous years

- how it can make its services more cost-efficient

- if its costs are increasing due to external factors beyond its control or internal inefficiencies it could fix

- if its increased spending has led to better services to optimise tax collection.

SRO uses performance measures to regularly monitor:

-

its internal measure and target for discretionary spending

SRO's discretionary spending includes staff pay and other operating costs, such as IT services.

- DTF’s BP3 measure on whether SRO's cost to collect $100 of tax revenue raised is less than the average of other state and territory revenue offices.

However, there are issues with these measures.

Not analysing discretionary spending changes

SRO regularly reports and reviews its discretionary spending against its budget. This includes some variance analysis. But overall, SRO's analysis lacks detailed insight into whether its cost increases are due to inefficiencies or factors outside of its control.

As a result, SRO cannot show it is collecting tax as efficiently as possible.

SRO met its internal target to spend 99 to 101 per cent of its discretionary budget between 2017 and 2021.

Over this period SRO’s discretionary budget and spending increased by 47 per cent. This increase primarily related to increased staff and associated costs.

Compliance FTE is the number of full-time equivalent staff doing back-end compliance activities at SRO.

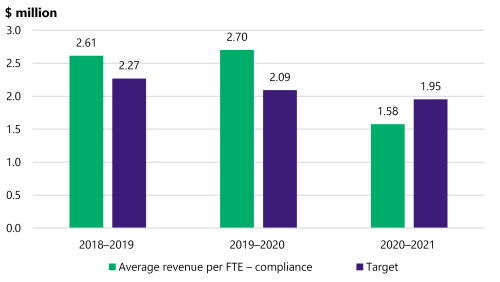

Since 2018–19 SRO has used an internal performance measure, ‘average revenue per FTE – compliance’, to monitor the revenue it generates per compliance FTE. It aims to collect at least 95 per cent of its target revenue per compliance FTE. This target varies over time.

SRO has consistently met this target, except for 2020–21. In 2020–21 SRO’s average revenue generated was $1.58 million per compliance FTE. This result was 81 per cent of its $1.95 million target. SRO did not analyse why it did not meet its target.

SRO also does not monitor the revenue it generates per FTE through voluntary compliance.

Issues with the BP3 measure on cost to collect $100 of tax

DTF and SRO are not effectively or transparently measuring and reporting on whether SRO is efficiently collecting tax.

DTF and SRO do not accurately report any tax collection cost efficiency performance measures in DTF's annual report.

DTF publicly reports against its BP3 measure that assesses if SRO’s ‘cost to collect $100 of tax revenue raised is less than the average of other state and territory revenue offices’.

DTF only reports if this measure is achieved or not achieved. DTF has reported that SRO has achieved this measure every year since it was introduced in 2018–19.

However, DTF and SRO do not calculate or know SRO’s cost to collect $100 of tax.

The method SRO uses to calculate its cost to collect $100 of tax to report against DTF’s BP3 measure is not consistent with the intent and description of the BP3 measure.

DTF and SRO use a national benchmarking report compiled by an external consultant that calculates ‘total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered’ rather than the cost to collect tax to report against this measure.

This does not assess if SRO is efficiently collecting tax because it:

- counts the costs SRO incurs doing things other than collecting tax

- excludes some costs SRO incurs collecting tax

- includes additional tax that is not collected by SRO and the value of grants SRO administers.

DTF reported that SRO achieved the BP3 measure for 2019–20 and 2020–21.

However, the national benchmarking report that DTF and SRO rely on for this measure states that SRO's ‘total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered’ was higher than the average for other jurisdictions in both of those years.

In 2020–21, the report ranked SRO 5th out of 8 jurisdictions on this cost efficiency measure.

DTF’s cost to collect measure compares SRO’s performance to other state and territory revenue offices. However, all states and territories collect different taxes at different rates and administer different non-tax matters. This makes comparing jurisdictions less meaningful for BP3 reporting.

This measure would be more meaningful if DTF published the actual value of SRO's cost to collect $100 of tax. This would allow Parliament and the public to assess if SRO's tax collection efficiency has improved or declined over time.

DTF and SRO's performance measuring and reporting needs improving

The RMF requires a government agency to have a meaningful mix of quality, quantity, timeliness and cost performance measures that:

- assess the efficiency and effectiveness of its services

- assess all its major activities for each BP3 output

- allow it to meaningfully compare and benchmark its performance over time.

DTF's set of BP3 measures do not meet all of its Resource Management Framework (RMF) requirements to report:

- SRO's performance transparently and effectively

- if SRO is improving its performance over time.

This is because:

- there are gaps in the BP3 measures to assess the effectiveness of SRO's activities. For example, there is no measure to assess the effectiveness of SRO's activities to increase taxpayers' voluntary compliance

- several performance measures lack transparency. This includes the revenue collection target measure and the measure that reports the amount of tax SRO collects.

DTF's BP3 output and 11 associated performance measures should assess if SRO:

- collects tax owed to the state

- collects tax when it is due

- is reducing its costs to collect tax over time.

However:

|

DTF's measures do not |

Because … |

For example … |

|---|---|---|

|

adequately measure if SRO optimises tax collection |

|

|

|

fully assess if SRO collects tax when it is due |

there is no effective measure or set of measures to fully assess taxpayers’ voluntary compliance. |

the measure to assess compliance only includes tax SRO collects through back-end compliance activities. It does not monitor tax SRO collects through voluntary compliance activities. |

|

assess if SRO's costs to collect tax are reducing over time |

SRO does not measure its cost to collect $100 in tax. |

SRO uses 'total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered' to report its cost to collect $100 of tax. The reported cost for this measure includes the total cost to administer all SRO activities, not just tax collection. |

|

drive SRO to continuously improve by analysing its historical performance |

at least 2 of its 11 performance measures and targets only require SRO to meet minimum standards or business as usual requirements. |

the measures ‘business processes maintained to retain ISO 9001 (Quality Management Systems) certification’* and ‘revenue banked on day of receipt'. These measures would be more suitable as internal performance measures. |

Accrued revenue is revenue that is owed but has not necessarily been paid yet.

*DTF removed this measure for 2022–23. It has been reintroduced for 2023–24.

This means:

- DTF cannot assess if it is effectively and efficiently meeting its objective to 'optimise Victoria's fiscal resources'

- Parliament and the public do not have enough performance information to assess if DTF and SRO are collecting tax effectively and efficiently.

DTF's BP3 revenue collection target does not optimise tax collection

In the state Budget, DTF forecasts how much tax each agency, including SRO, will accrue each financial year. SRO aims to accrue 99 per cent of the tax DTF forecasts it should collect each year.

SRO has generally met its revenue collection target since 2017. However, there are issues with the target because it is almost a given that SRO will meet it.

This is because:

- SRO reports its performance against a revised forecast that DTF releases approximately 6 weeks before the end of the financial year

- DTF's revised forecast includes the revenue SRO has already accrued for the financial year.

SRO reports accrued revenue, not collected revenue

DTF has a BP3 measure 'revenue collected as a percentage of state Budget target' to report the amount of tax SRO collects each financial year. But SRO reports the revenue it accrues instead of the amount it collects.

This means SRO counts tax as soon as taxpayers are due to pay it instead of when it actually receives the money, which is usually at a later time.

This is misleading because:

- the amounts are often different

- the measure specifies 'collected' revenue.

DTF and SRO do not adequately measure taxpayers' voluntary compliance

DTF and SRO do not have any measures to assess the effectiveness of SRO's initiatives to improve taxpayers' voluntary compliance.

As a result, SRO cannot adequately show if its initiatives are:

- improving voluntary compliance rates

- reducing SRO’s operating costs

- reducing the tax gap.

SRO has heavily invested in a range of initiatives to:

- increase taxpayers’ awareness of their obligations

- make system and automation changes to make it easier for taxpayers to comply.

This is because improving taxpayers' voluntary compliance with their obligations is one of the most efficient and effective ways of reducing the tax gap.

Voluntary compliance can be difficult to measure because it involves working out if an agency’s actions have influenced a taxpayer's behaviour or if they would have complied anyway.

SRO has started investigating how to measure voluntary compliance. It needs to keep investigating ways to consistently measure and analyse:

- changes in taxpayers’ awareness and behaviour

- trends in the amount of tax taxpayers voluntarily pay

- the return on investment for all its voluntary compliance initiatives.

This will help SRO identify and assess:

- which individual initiatives are working well and which are not

- where it should focus future initiatives to improve voluntary compliance rates.

DTF needs to clarify its governance arrangements for SRO

DTF's governance of SRO's financial compliance performance needs clarifying and improving to adequately reflect the Standing Directions 2018 under the Financial Management Act 1994's (Standing Directions) intent for good financial management. This is because:

- DTF governance arrangements and SRO's governance documentation do not show that they have a shared understanding of SRO's status

- DTF's secretary does not sufficiently oversee SRO's financial compliance performance.

SRO's status

DTF and SRO inconsistently describe SRO's status within the Victorian Public Sector, which is why its relationship with DTF is unclear. SRO is described as a:

- unit of DTF

- a public entity

- semi-autonomous service agency of DTF

- a portfolio agency of DTF.

There is no legislation that establishes SRO as a separate entity to DTF. This is because:

- the Taxation Administration Act 1997 (Vic) (the Tax Act) sets up the Commissioner of State Revenue's (Commissioner) role and responsibilities for administering tax law. It does not set up SRO

- the Public Administration Act 2004 defines the types of entities that make up the public sector. SRO was established in 1992 and does not match the definition of the entities recognised by the Public Administration Act 2004.

SRO was established and works with DTF in accordance with a Framework Agreement signed by the Treasurer, DTF’s secretary and the Commissioner. This agreement:

- says SRO is subject to the governance and reporting obligations of DTF

- specifies DTF's secretary and the Commissioner's roles and responsibilities for SRO's performance

- establishes the Commissioner as SRO's CEO. This means the Commissioner has dual roles.

During our audit, DTF and SRO confirmed that SRO is a unit of DTF. But, in practice DTF governs and works with SRO differently to its other business units.

This results in a hybrid governance arrangement between DTF’s secretary and the Commissioner.

Overseeing SRO's financial compliance performance

Governance roles and responsibilities for SRO's financial compliance performance need to be reviewed and clarified to fully meet the Standing Directions' intent.

As Figure A shows, this is because DTF's secretary, as SRO's accountable officer and responsible body, does not sufficiently oversee and review SRO's financial compliance performance.

Figure A: Accountable officer and responsible body roles and responsibilities for SRO's financial performance

| Roles and responsibilities under the Standing Directions | What is good | What needs to be reviewed |

|---|---|---|

| The department head/secretary is the accountable officer. | The Framework Agreement confirms that DTF's secretary is SRO's accountable officer. |

|

The accountable officer is responsible for:

|

|

There are no established relationships between:

|

| The responsible body and accountable officer are the same person for entities such as DTF, which includes SRO, because there is no statutory board or equivalent governing body. | DTF confirmed that DTF's secretary is SRO's responsible body. | SRO’s 2020 audit committee charter policy incorrectly identifies the Commissioner as SRO's responsible body. |

| The responsible body is ultimately responsible for the agency's financial performance (in this case this includes SRO's performance as a unit of DTF). The responsible body must annually assess the agency's compliance with all applicable requirements in the Financial Management Act 1994 and the Standing Directions. |

SRO's audit committee annually assesses SRO's compliance with the Financial Management Act 1994 and Standing Directions' requirements. | There is insufficient evidence that before DTF includes SRO's annual attestation in its annual financial report, it is reviewed by:

|

Source: VAGO.

DTF's secretary considers that in their role as the accountable officer and responsible body, 'they are able to rely on financial compliance information and attestations provided by the Commissioner to effectively meet the intent of the Standing Directions’.

DTF's secretary, as SRO's accountable officer and responsible body, must be able to assure Parliament and the public of SRO's financial compliance performance with the Standing Directions.

In this setting, assurance means DTF's secretary must be certain and confident in SRO's annual financial compliance attestation process and statements. This requires DTF's secretary to verify and challenge, rather than just accept, attestations and statements made by the Commissioner and SRO's audit committee.

DTF's secretary, as the responsible body, has not demonstrated how they get adequate assurance over SRO's compliance with the Standing Directions to inform their annual attestation statement for the whole of DTF, including SRO.

There is no evidence that current governance arrangements hinder SRO's performance in collecting tax or impact the integrity of SRO's financial compliance assessment.

However, DTF’s and SRO's governance arrangements need to be reviewed and clarified to accurately reflect the Standing Direction's intent and requirements.

SRO must continue to improve its work practices

SRO has introduced initiatives to reduce costs, modernise its processes and meet taxpayers’ needs.

However, we identified work practices that it could further improve.

|

We found … |

As a result … |

|---|---|

|

SRO has a BP3 target to resolve tax objections within 90 days. However, compared to 2018–19, it currently takes 9 days longer for SRO to allocate an objection to an officer for processing. |

|

|

SRO does not systematically review all feedback and complaints. This means it is potentially missing opportunities to improve its practices. |

|

SRO has developed revenue line profiles for its major taxes to identify, assess and manage taxpayer compliance risks. However, SRO could not show us that it regularly assesses its controls to manage these risks. |

SRO does not know if its controls effectively manage significant noncompliance risks. |

Our recommendations

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Treasury and Finance (working with the State Revenue Office) | 1. makes sure it and the State Revenue Office:

|

Accepted |

2. makes sure its Budget Paper 3: Service Delivery performance measures meet the Resource Management Framework's requirements by:

|

Accepted in principle | |

| State Revenue Office | 3. builds on its previous tax gap analyses, particularly for high-risk taxes, to get a regular and more detailed understanding of the tax gap to help it optimise how it collects tax (see Section 2.1) | Partially accepted |

| 4. improves its set of performance measures to monitor and analyse cost efficiencies over time and transparently reports on them (see Section 2.3) | Accepted in principle | |

5. continues to develop specific project-based performance measures for its voluntary compliance initiatives to:

|

Accepted in principle | |

6. reviews its:

|

Accepted in principle |

1. Audit context

SRO collects state taxes for the Victorian Government. The government uses this money to fund community services, such as education, health, police, infrastructure and public transport.

It is important that SRO optimises how it collects tax so the government can:

- adequately fund these services

- help Victoria recover from the COVID-19 pandemic and recent natural disasters.

In this chapter

The Australian Taxation Office (ATO) collects federal taxes, including personal income tax, corporate taxes and GST. These taxes are separate from state based taxes.

1.1 Victorian state tax revenue

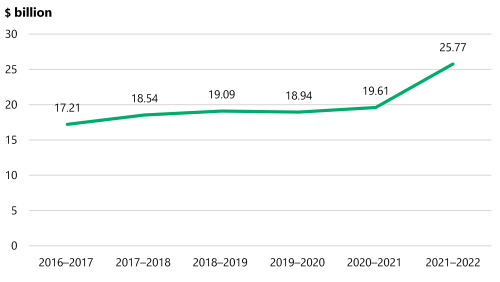

Figure 1A shows that state taxes made up 37 per cent of the Victorian Government's revenue in 2021–22 at $30.5 billion. Of this, SRO collected $25.8 billion.

Other agencies, including VicRoads and the Victorian Gambling and Casino Control Commission, collected the rest.

Figure 1A: Victorian Government’s revenue sources in 2021–22

Source: VAGO based on the 2021–22 Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria.

Key state taxes

Figure 1B shows the key state taxes SRO collects and how much it collected in 2021–22.

Figure 1B: SRO’s key state taxes in 2021–22

Source: VAGO based on SRO data.

A person's principal place of residence is the land they own and occupy as their home.

Primary production land is land that a person or business uses to grow, keep and harvest crops, plants, animal and animal products to sell. This does not include land people use to keep animals and grow crops as a hobby or for personal use.

For this audit, we assessed SRO's overall performance and analysed 4 taxes in detail:

|

Tax |

Applies when … |

|---|---|

|

Land tax |

A person owns property that:

|

|

Payroll tax |

A business, or group of businesses, annually pays more than $700,000(b) of wages in Victoria |

|

Land transfer duty |

A person buys a property |

|

Metropolitan planning levy |

A person or business plans to develop land in metropolitan Melbourne and the estimated cost to develop it is more than $1,133,000 |

(a)The threshold for land tax will be $50,000 from 1 January 2024.

(b)The threshold for payroll tax will be $900,000 from 1 July 2024 and $1 million from 1 July 2025.

We selected these taxes because they make up most of the revenue SRO collects each year.

Financial relief, grants and concessions for taxpayers

SRO administers a range of government grants, subsidies and exemptions.

SRO also provided hundreds of millions of dollars in financial relief measures to help Victorians respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and 2019–20 bushfires. These measures included tax deferrals, waivers and refunds.

These measures required significant SRO resources. This impacted its normal operations from 2019–20 to 2021–22.

In agreement with the government, SRO also reduced its compliance activities in response to the pandemic.

We did not look at financial relief measures, grants, subsidies and other concessions in this audit.

1.2 Relevant legislation

The following legislation outlines the requirements for SRO's governance, tax collection and performance reporting:

|

Legislation |

Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Taxation Administration Act 1997 (Vic) (the Tax Act) |

|

|

Financial Management Act 1994 |

|

|

Standing Directions 2018 under the Financial Management Act 1994 (Standing Directions) |

Specifies public sector agencies’ governance responsibilities for managing public money |

|

Public Administration Act 2004 |

Sets governance standards for public sector entities |

The Public Administration Act 2004 also defines the types of entities that make up the public sector. These include:

- ‘public service bodies’, which include departments and administrative offices

- ‘special bodies’ that have a particular relationship with the government, such as Victoria Police

- ‘public entities', such as public hospitals and TAFE institutes.

There is no legislation that establishes SRO as a public service body, special body or a public entity. This means SRO works with DTF in accordance with:

- a Framework Agreement that is signed by the Treasurer, DTF’s secretary and the Commissioner

- a set of formal delegations under the Tax Act and the Public Administration Act 2004.

We refer to the Commissioner and SRO’s CEO as the Commissioner throughout the rest of the report.

The Commissioner is accountable to the Treasurer and DTF's secretary for SRO's performance.

The agreement formalises:

- DTF's secretary as SRO's accountable officer. This means that among other things, they are responsible for SRO's financial performance under the Standing Directions

- the Commissioner as SRO's CEO. This means they are responsible for SRO's day to-day operations.

This means the Commissioner has dual roles as the Commissioner and as the CEO of SRO.

These parties review the agreement every 3 years. The current agreement is from 1 January 2022 to 31 December 2024.

1.3 DTF’s and SRO’s roles and responsibilities

DTF's and SRO's responsibilities for managing state taxes are:

|

DTF … |

SRO … |

|---|---|

|

|

The Framework Agreement outlines the specific roles and responsibilities of DTF's secretary and the Commissioner to deliver these services.

|

DTF’s secretary is responsible for … |

The Commissioner (as SRO’s CEO) is responsible for … |

|---|---|

|

|

Figure 1C shows the reporting relationships between the Commissioner, DTF’s secretary and the Treasurer under the agreement.

Figure 1C: Reporting relationships

Source: VAGO based on the 2022–2024 Framework Agreement.

Performance monitoring and reporting

The RMF is the government's overarching policy for:

- the state Budget process

- government agencies' performance reporting.

The RMF requires government agencies to develop a set of logical and linked objectives, outputs and measures that:

- drive agencies to deliver the government's priorities

- allow Parliament and the public to assess agencies' performance

- drive agencies to continuously improve their performance.

The RMF requires agencies to have a meaningful mix of quality, quantity, timeliness and cost measures that:

- assess the efficiency and effectiveness of their services and major initiatives

- allow them to meaningfully compare and benchmark their performance over time.

Figure 1D shows DTF's BP3 objective and output for SRO.

Figure 1D: DTF's BP3 objective and output for SRO

Note: Optimising Victoria's fiscal resources is one of DTF's objectives.

Source: VAGO based on the BP3.

DTF has 11 BP3 measures and targets to monitor and publicly report SRO's performance in optimising tax collection.

SRO internally monitors and reports on 22 measures, including 7 of DTF’s BP3 measures and targets (see Appendix D for more information).

Figure 1E shows the different reports SRO and DTF use to report on SRO's performance.

Figure 1E: DTF’s and SRO's performance reports

| Report | Purpose | Audience |

|---|---|---|

| DTF’s annual performance statement | Reports how well SRO is optimising Victoria’s fiscal resources using 11 BP3 measures and targets | External (for the Treasurer, government, Parliament and the public) |

| Commissioner’s quarterly report to DTF's secretary | Reports SRO’s progress against its business plan (which the Framework Agreement requires) | Internal (for DTF’s secretary) |

| SRO’s scorecard | Reports on 22 measures and targets that SRO’s annual plan identifies | Internal (for the Commissioner and SRO's executives) |

| SRO’s annual review | Reports on a mix of scorecard and BP3 measures | External (publicly available on SRO’s website) |

Source: VAGO.

2. Collecting tax and reporting performance

Conclusion

SRO reliably collects the tax it knows about and the amount it collects has increased over the last 5 years. However, there is a very high likelihood that SRO could collect more tax by better analysing:

- if it is effectively reducing the tax gap

- its initiatives to improve taxpayers’ compliance.

DTF and SRO do not give Parliament and the public sufficient information on how effectively and efficiently SRO collects tax. This is due to issues with:

- DTF and SRO’s performance monitoring and reporting

- how DTF governs SRO’s performance.

In this chapter

2.1 Considering the tax gap

One of DTF's BP3 objectives is to 'optimise Victoria’s fiscal resources'. SRO contributes to this objective by providing revenue management and administrative services to the government. This implies SRO should:

- regularly analyse and estimate the tax gap for its major taxes

- use this information to maximise the amount of tax it collects.

SRO undertakes a range of ongoing initiatives to reduce the tax gap. These include:

- back-end compliance initiatives

- analysing internal and external data

- voluntary compliance initiatives.

SRO does not regularly analyse:

- the tax gap for all its major taxes

- how effectively its initiatives are reducing the tax gap.

As Figure 2A shows, the tax gap is the difference between the total amount taxpayers owe and what they actually pay.

Figure 2A: The tax gap

Note: This graphic is not intended to represent the actual size of the tax gap.

Source: VAGO.

Measuring the tax gap can help a tax collection agency:

- assess how effectively it collects all taxes

- better understand how much tax is not being paid

- identify why some people do not pay tax (both overall and for specific taxes)

- design more effective strategies to reduce the gap

- decide how to allocate staff and resources.

All tax collection agencies find it difficult to accurately calculate their tax gap. This is because:

- tax gaps are made up of unknown amounts that people and businesses do not report

- data may not be readily available.

Some of the reasons people and businesses do not report and pay tax are:

- they are not aware of their tax obligations

- they misunderstand their obligations

- they choose not to (for example, they pay their employees cash and do not report it).

There is a very high likelihood that SRO could collect more tax if it regularly analysed the tax gap. This would help SRO:

- assess and report on how effectively its initiatives are reducing the tax gap

- identify where it should invest its resources to collect more tax.

DTF believes that an agency should only regularly analyse the tax gap if the benefits outweigh the costs of conducting it. However, DTF and SRO have not done this cost–benefit analysis.

SRO has historically analysed the gap for payroll tax. But it has not done this on a regular basis or for other taxes. It has also not used this information to inform its annual work program.

In 2016, SRO analysed the gap for payroll tax for the period between 2010–11 to 2014–15.

SRO's analysis showed that the estimated average annual payroll tax gap for this period was about $297 million, or 5.2 per cent of the 2014–15 payroll tax revenue.

SRO recognises the value of analysing the tax gap. It has started analysing the gap for payroll tax again.

It also plans to analyse the land tax gap in 2022–23 to build its knowledge of Victoria’s overall tax gap.

However, if SRO does not expand on its work to regularly analyse the gap for at least its major taxes, then it cannot show if it is effectively:

- optimising how it collects tax

- contributing to DTF's objective.

2.2 BP3 performance monitoring, measuring and reporting

DTF and SRO need to improve how they measure and report SRO's performance in optimising tax collection.

We found:

- DTF’s BP3 output to optimise tax collection focuses on efficiency and fairness, not effectiveness

- DTF's set of BP3 measures to report SRO performance have some gaps and lack transparency.

The RMF says an agency's output should:

- cover all the major activities of the output

- drive the agency to achieve its objective.

It also requires agencies to have a meaningful mix of quality, quantity, timeliness and cost BP3 measures and targets that:

- assess the efficiency and effectiveness of their services and major activities

- drive them to continually improve their performance over time.

DTF's BP3 measures should therefore assess if SRO:

- effectively and efficiently collects tax owed to the state

- collects tax when it is due

- is reducing its costs to collect tax over time.

DTF’s BP3 output focuses on efficiency and fairness, not effectiveness

DTF's output for SRO's services, which contribute to its objective to 'optimise Victoria’s fiscal resources', is 'revenue management and administrative services to government'.

The description of this output notes that SRO 'provides revenue management and administrative services across the various state-based taxes in a fair and efficient manner for the benefit of all Victorians'.

This is an issue because it does not mention effectiveness. This means DTF's BP3 measures and targets for SRO focus on efficiency and fairness.

As a result, DTF's set of BP3 measures do not adequately assess how effectively SRO collects tax owed to the state.

To assess how effectively SRO collects tax, DTF and SRO could develop measures to assess SRO's effectiveness in:

- making it easier for people and businesses to access and comply with their tax obligations

- shifting community attitudes and behaviour towards voluntary compliance.

DTF's BP3 measures to report SRO's performance need strengthening

DTF has several good individual BP3 measures to assess aspects of SRO's performance in collecting tax.

But there are weaknesses in the BP3 measures DTF uses to assess how effectively SRO's activities are optimising the amount of tax it collects.

For example:

|

DTF’s set of BP3 measures do not … |

Because … |

For example … |

|---|---|---|

|

adequately measure if SRO optimises tax collection |

|

|

|

fully assess if SRO collects tax when it is due |

there are no measures to specifically assess taxpayers’ voluntary compliance. |

the measure to assess compliance only includes tax SRO collects through back-end compliance activities. It does not monitor tax SRO collects through voluntary compliance activities. |

|

assess if SRO's costs to collect tax are reducing over time |

SRO does not measure its cost to collect $100. |

SRO uses 'total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered' to report against its cost to collect $100 measure. But total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered does not indicate how efficiently it collects tax. |

|

drive SRO to continuously improve by analysing its historical performance |

at least 2 of its 11 performance measures and targets only require SRO to meet minimum standards or business as usual requirements. |

the measures ‘business processes maintained to retain ISO 9001 (Quality Management Systems) certification’* and ‘revenue banked on day of receipt’. These measures would be more suitable as internal performance measures. |

*DTF removed this measure for 2022–23. It has been reintroduced for 2023–24.

Note: Refer to Appendix D for a full list of BP3 and scorecard measures.

Accuracy of DTF's revenue collection forecasts

DTF forecasts the amount of tax the government will accrue each year in the state Budget.

DTF updates its forecast during the year based on historical and economic factors.

DTF does not analyse or include the tax gap in its forecasts because the Financial Management Act 1994 does not require it to. This means its forecasts may not include all the tax owed to the state.

DTF has met its BP3 target for the accuracy of its forecasts except for 2020–21 and 2021–22. This was primarily because the property market performed better than expected. As a result, SRO collected more tax than DTF forecasted.

To meet the target, DTF’s forecasts must be within 5 per cent of the amount of tax the government receives.

Issues with SRO's reporting against its revenue collection target

DTF's BP3 measure requires SRO to collect 99 per cent of the tax it forecasts it should collect each year.

SRO has met its target over the last 6 years except for 2019–2020, which was likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

However:

- it is almost a given that SRO will meet the target

- SRO reports the tax it accrues, not the tax it actually collects.

As Figure 2B shows, the amount of tax SRO collects has increased since 2016–17.

Figure 2B: Total tax collected by SRO from 2016–17 to 2021–22

Note: The amount SRO collected increased between 2020–21 and 2021–22 primarily due to higher activity in the property market. This led to SRO collecting significantly more land transfer duty.

Source: VAGO based on SRO data.

This increase does not necessarily show that SRO is optimising how it collects tax. This is because the amount of tax it collects will also increase if:

- the government introduces more taxes or increases tax rates

- there are more taxpayers

- the economy performs better than expected.

Meeting the target is almost a given

DTF updates its forecast for each financial year twice during the reporting period to consider:

- the latest economic data

- the amount of tax SRO has collected to date.

This means it is almost a given that SRO will meet its collection target.

As Figure 2C shows, this is because SRO reports its performance against the updated forecast DTF releases approximately 6 weeks before the end of the financial year.

This forecast includes the amount of tax SRO has already collected when DTF finalises it in mid-April. This means SRO only reports against an 8 to 10-week period instead of a 12 month period.

Figure 2C: DTF’s forecasts and SRO’s reporting period for 2020–21

Source: VAGO.

As a result, SRO's reporting does not give a meaningful insight into its performance.

SRO reports accrued revenue, not collected revenue

SRO reports the amount of revenue it accrues each financial year instead of the amount it collects.

This is misleading because these amounts are often different.

Counting accrued revenue is appropriate and meets the Australian Accounting Standards. But SRO’s reporting is not transparent because Parliament and the public might have a different understanding of what ‘collected’ means.

2.3 SRO's internal performance measures and reporting

SRO's internal performance measures do not assess all of its key initiatives to optimise tax collection.

SRO uses an internal scorecard to monitor and report on 22 measures. The scorecard informs DTF's BP3 reporting.

SRO updates its scorecard monthly and includes trends for each measure. This allows SRO to assess its performance at a point in time and over time.

However, the scorecard does not have measures for all of SRO’s key initiatives that feed into BP3 reporting, including its initiatives to:

- make it easier and cheaper for taxpayers to comply with their obligations

- improve taxpayers’ voluntary compliance.

This means SRO cannot assess if its key initiatives to improve taxpayers’ compliance are working and providing value for money.

Measuring taxpayers’ compliance

SRO's 2020–23 strategic plan lists measuring and improving taxpayers’ compliance, particularly voluntary compliance, as a key outcome. Its compliance strategy and 2020–21 annual business plan also focus on maximising taxpayers’ compliance.

SRO has heavily invested in initiatives to improve taxpayers’ compliance. For example:

|

SRO advised us it… |

Over … |

To … |

|---|---|---|

|

has invested $150 million |

the last 8 years |

improve voluntary compliance. |

|

has invested $92 million |

the last 5 years |

return $2.8 billion to the state through back-end compliance initiatives. |

|

will invest approximately $70 million |

5 years from 2020–21 |

'futureproof' its revenue management system and expand its tax compliance programs to make it easier for taxpayers to meet their obligations. It expects this project will generate an extra $379.7 million in tax from 2021–22 to 2024–25. |

However, SRO does not effectively measure if its initiatives are:

- improving voluntary compliance rates

- reducing the risk of taxpayers not complying.

SRO assesses and reports the tax it collects through its back-end compliance initiatives using its:

- 'compliance revenue assessed meets targets' measure

- 'average revenue per FTE – compliance' measure.

But these measures mainly monitor the tax SRO collects through its back end compliance initiatives.

SRO has done limited return-on-investment analyses for some individual voluntary compliance initiatives.

But it does not:

- have a set of measures to effectively assess and report on all its voluntary compliance initiatives

- track the percentage of total tax that taxpayers voluntarily pay

- analyse the return on investment for all its voluntary compliance initiatives

- analyse if increasing voluntary compliance is reducing its operating costs.

Voluntary compliance is difficult to measure because it involves working out if an agency influenced a taxpayer’s behaviour. Like measuring the tax gap, these challenges are not unique to SRO.

SRO has started developing ways to consistently measure the impact of its voluntary compliance initiatives. It is important SRO continues this work to:

- reduce its reliance on measuring back-end compliance only

- use the results to get funding for future initiatives to improve voluntary compliance rates.

2.4 DTF's governance of SRO’s financial performance

DTF's governance of SRO's financial compliance performance needs clarifying and improving to adequately reflect the Standing Directions' intent for good financial management. This is because:

- DTF governance arrangements and SRO's governance documentation do not show that they have a shared understanding of SRO's status

- DTF's secretary does not sufficiently oversee SRO's financial compliance performance.

DTF and SRO do not have a shared understanding of SRO’s status

DTF and SRO inconsistently describe SRO's status as an entity within the Victorian public sector.

For example:

|

Source |

Description |

|---|---|

|

DTF’s website |

SRO is a 'public entity' |

|

DTF's 2021–22 annual report |

SRO is a portfolio agency of DTF |

|

SRO’s website |

SRO is 'semi-autonomous service agency' |

|

The 2022–2024 framework agreement |

SRO is a service agency of DTF |

|

SRO’s 2020 audit committee charter policy |

'SRO is not a public sector agency but acts as an independent service agency under the Framework Agreement' |

|

SRO’s written correspondence to VAGO to clarify its status |

'SRO is a public entity under the Public Administration Act 2004' |

|

DTF staff in meetings with VAGO |

SRO is a unit of DTF |

There is no legislation that establishes SRO as a separate entity to DTF. This is because:

- the Tax Act sets up the Commissioner's role and responsibilities for administrating tax law. It does not set up SRO

- the Public Administration Act 2004 defines the types of entities that make up the public sector. It also sets governance and accountability standards for each type of entity. SRO was established in 1992 and does not match the definition of the entities recognised by the Public Administration Act 2004.

SRO was established by and works with DTF in accordance with a Framework Agreement signed by the Treasurer, DTF's secretary and the Commissioner.

This agreement:

- describes SRO as a 'service agency of DTF that is subject to the governance and reporting obligations of DTF as a department within the meaning of the Public Administration Act 2004'

- specifies DTF's secretary and the Commissioner's roles and responsibilities for SRO's performance

- establishes the Commissioner as SRO's CEO. This means the Commissioner has dual roles as the Commissioner under the Tax Act and SRO's CEO under the Agreement. The Commissioner is responsible for SRO's day-to-day operations.

During our audit, DTF confirmed that SRO is a unit of DTF. But in practice:

- SRO and DTF's relationship is referred to inconsistently throughout DTF's and SRO's websites and documentation

- DTF governs and works with SRO differently to its other business units. SRO is not included in DTF's organisational chart

- SRO operates, and is seen by DTF, as a semi-autonomous unit to DTF.

This has resulted in hybrid governance arrangements for SRO.

Oversight of SRO's financial compliance performance

DTF’s and SRO's governance roles and responsibilities for SRO's financial compliance performance do not fully meet the Standing Directions’ intent.

As Figure 2D shows, this is because DTF's secretary as the accountable officer and responsible body does not sufficiently oversee and review SRO's financial compliance performance.

Figure 2D: Accountable Officer and responsible body roles and responsibilities for SRO's financial compliance

| Roles and responsibilities under the Standing Directions | What is good | What needs to be reviewed |

|---|---|---|

|

The department head/secretary is the accountable officer. |

The Framework Agreement confirms that DTF's secretary is SRO's accountable officer. |

|

|

The accountable officer is responsible for:

|

|

There are no established relationships between:

SRO's 2020–21 and 2021–22 annual financial attestation statements against the Standing Directions to its audit committee incorrectly state that the Commissioner is SRO's accountable officer. These were then signed off by the Commissioner. |

|

The responsible body and accountable officer are the same person for entities such as DTF, which includes SRO, because there is no statutory board or equivalent governing body. |

DTF confirmed that DTF's secretary is SRO's responsible body. |

SRO’s 2020 audit committee charter policy incorrectly identifies the Commissioner as SRO's responsible body. |

|

The responsible body is ultimately responsible for the agency's financial compliance performance (in this case this includes SRO's performance as a unit of DTF). The responsible body must annually assess the agency’s compliance with all applicable requirements in the Financial Management Act 1994 and the Standing Directions. |

The Framework Agreement allows SRO to set up its own audit committee to annually assess SRO's compliance with the Financial Management Act 1994 and Standing Directions' requirements. |

There is insufficient evidence that before DTF includes SRO’s annual attestation in its annual financial report, it is reviewed by:

For example, this makes the following attestations in SRO's 2020–21 and 2021–22 signed attestation statements inaccurate:

|

Source: VAGO.

DTF's secretary considers that in their role as the accountable officer and responsible body 'they are able to rely on financial compliance information and attestations provided by the Commissioner to effectively meet the intent of the Standing Directions’.

DTF's secretary, as SRO's accountable officer and responsible body, must be able to assure Parliament and the public of SRO's financial compliance performance with the Standing Directions because SRO is a unit of DTF.

In this setting, assurance means DTF's secretary must be certain and confident in SRO's annual financial compliance attestation process and statements. This requires DTF's secretary to verify and challenge, rather than just accept, attestations and statements made by the Commissioner and SRO's audit committee.

As Figure 2D shows, SRO's 2020–21 and 2021–22 annual financial compliance attestations contain inaccurate signed attestations. This means the attestation statements have not been subject to adequate oversight by the accountable officer and responsible body.

This is because DTF does not have a robust review process that meets the Standing Directions’ intent for the responsible body's responsibilities.

DTF's secretary, as the responsible body, has not demonstrated how they get adequate assurance over SRO's compliance with the Standing Directions to inform their annual attestation statement for the whole of DTF, including SRO.

We are not suggesting these issues affect:

- how SRO collects tax

- the integrity of SRO's financial compliance assessment.

However, DTF’s and SRO's governance arrangements need to be clarified and improved to ensure SRO's financial compliance performance is reviewed in accordance with the Standing Directions’ intent.

3. SRO’s costs and taxpayer services

Conclusion

SRO has reduced its costs to collect tax in some areas. But its overall costs have increased over time. SRO cannot show if this increase is due to inefficiencies or factors outside its control.

SRO has initiatives to reduce the amount of time, effort and money taxpayers need to meet their obligations. It also has initiatives to improve how it monitors noncompliance. SRO expects these initiatives will improve taxpayers’ compliance and awareness of their obligations.

There are opportunities for SRO to further improve its services.

In this chapter

3.1 Costs to collect tax

SRO has reduced its costs to collect tax in a range of areas, which we discuss in Section 3.2. But its overall costs have increased over time.

SRO has some performance measures to monitor its costs, including its:

- discretionary spending and total output costs

- cost to collect $100 of tax.

However, there are issues with these measures. SRO also does not analyse:

- its spending compared to previous years

- how it can make its services more cost-efficient.

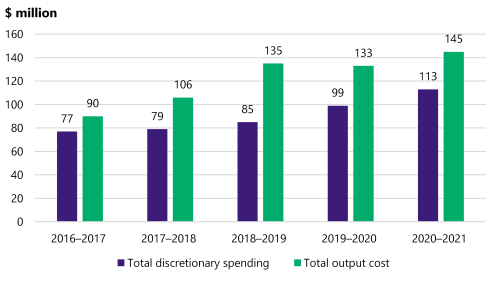

Discretionary spending and total output costs

From 2016–17 to 2020–21 SRO's total discretionary spending was between 63 and 85 per cent of its total output costs, which DTF includes in its BP3 reporting. SRO's remaining output costs were:

-

non-discretionary costs

Non-discretionary costs are money that an organisation must spend to keep functioning.

Capital costs are fixed one-off costs that are not part of an organisation’s normal operations.

- capital costs.

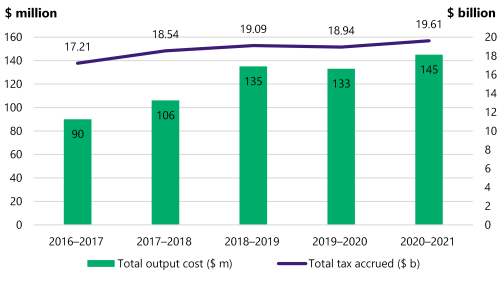

As Figure 3A shows, SRO's total output costs increased by 61 per cent between 2016–17 and 2020–21. Over the same time, the amount of tax SRO accrued increased by 14 per cent.

SRO's total output cost has not just increased due to costs related to collecting tax. It also includes the cost of:

- administering grants

- implementing COVID-19 relief measures

- starting capital projects.

COVID-19’s impact on the economy and SRO's reduction in compliance activity because of the pandemic also adversely impacted the amount of revenue it accrued between 2019–20 and 2020–21.

Figure 3A: SRO’s total output costs and total collected tax from 2016–17 to 2020–21

Source: VAGO based on SRO data and the BP3.

As Figure 3B shows, over this period SRO’s discretionary spending rose by 47 per cent. In each of the financial years from 2016–17 to 2020–21, staff salaries and other associated costs made up between 68 and 72 per cent of SRO's total discretionary spending.

In its scorecard, SRO reported that its number of FTE positions increased by 97.8 from 524.1 in 2016–17 to 621.9 in 2020–21. This led to a $23.5 million increase in salaries and other associated costs over the same period while its total output costs increased by $54.8 million.

Figure 3B: SRO's total discretionary spending and total output costs from 2016–17 to 2020–21

Source: VAGO based on SRO data and the BP3.

SRO has a scorecard measure to monitor how much of its discretionary budget it spends each financial year. It aims to spend 99 to 101 per cent of its budget. SRO has consistently met this target from 2017 to 2021.

SRO also has a scorecard measure ‘average revenue per FTE – compliance’ to monitor the revenue it generates per compliance FTE. Its target is to collect 95 per cent or more of its target revenue per FTE, which varies over time.

SRO has used this measure since 2018–19. Figure 3C shows it did not meet the target in 2020–21 because it only collected 80.6 per cent of its target revenue per FTE – compliance. SRO did not analyse why.

Figure 3C: SRO’s average revenue per FTE – compliance results from 2018–19 to 2020–21

Source: VAGO based on SRO data.

SRO does not monitor the revenue it generates per FTE through voluntary compliance.

Analysing costs

SRO has also not analysed if its cost increases are due to inefficiencies or factors outside its control.

Actuals is the actual amount an organisation has spent.

Budget is the amount of money an organisation expected to spend.

SRO regularly reviews and reports its costs against its budget to its executives. These reports include a high-level analysis of SRO’s actuals, budget and the dollar value difference between them for discretionary spending, non-discretionary spending and capital costs.

However, these reports do not:

- holistically analyse cost savings and efficiency across the organisation

- identify possible cost savings

- identify actions to reduce operating costs

- compare SRO’s spending to previous years.

Without this analysis, SRO cannot show that it is collecting tax as efficiently as possible.

Cost to collect $100 of tax

The ATO and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) identify several benefits of calculating and analysing the cost to collect $100.

|

The … |

Says a tax agency can calculate the cost to collect $100 to … |

|---|---|

|

ATO |

|

|

OECD |

|

DTF reported that SRO has achieved the BP3 measure, ‘cost to collect $100 of tax revenue raised is less than the average of state and territory revenue offices’, each year since it was introduced in 2018–19. DTF does not report the actual cost.

However:

- DTF does not correctly report against the measure

- comparing SRO with other jurisdictions is not meaningful for BP3 reporting.

Not correctly reporting against the cost to collect BP3 measure

DTF has not been correctly reporting against the BP3 measure ‘cost to collect $100 of tax revenue raised is less than the average of state and territory revenue offices’. This is because it does not know how much it costs SRO to collect $100 of tax.

DTF and SRO use a national benchmarking report compiled by an external consultant to report against this measure. But the report measures SRO’s ‘total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered’ rather than its cost to collect tax.

'Total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered' does not assess if SRO is efficiently collecting tax because it:

- counts the costs SRO incurs doing things other than collecting tax

- excludes some costs SRO incurs collecting tax

- includes:

- additional tax that is not collected by SRO

- the value of grants SRO issues.

This means that DTF’s reporting is not consistent with the wording of the BP3 measure.

As a result, DTF and SRO do not accurately report on any public tax collection cost efficiency performance measures.

SRO provided a methodology for how it calculated the BP3 measure. However, SRO did not follow the methodology it provided.

DTF reported that SRO achieved the BP3 measure for 2019–20 and 2020–21.

However, the national benchmarking report that DTF and SRO rely on for this measure states that SRO's ‘total expenditure as a percentage of revenue administered’ was higher than the average for other jurisdictions in both of those years.

In 2020–21, the report ranked SRO 5th out of 8 jurisdictions on this cost efficiency measure.

For DTF and SRO to calculate the cost to collect, SRO would need to start identifying how much it spends:

- collecting tax

- on its other operations.

DTF and SRO cannot know if SRO is optimising how it collects tax because SRO does not currently do this.

While there are benefits to calculating the cost to collect, there are also some limitations SRO needs to consider. This is because external factors can influence this cost, such as:

- changes in tax rates

- economic factors, which can change the amount of tax people and businesses owe

- new non-discretionary spending programs.

Comparing SRO with other jurisdictions is not meaningful for BP3 reporting

Each state and territory revenue office collects different taxes at different rates.

This means that a cost to collect comparison between other state and territories’ tax offices is not like for like. This makes the BP3 measure less meaningful.

If DTF reported SRO's actual cost to collect $100 of tax and not the comparative result, it would help Parliament and the public see if SRO’s efficiency in collecting tax has improved or declined over time.

3.2 Initiatives to reduce costs, improve compliance and meet taxpayers’ needs

SRO has introduced many successful initiatives to reduce costs in specific areas and better meet taxpayers’ needs, including projects to:

-

reduce its suspense account

The suspense account is the holding account SRO allocates money to when it receives a payment but cannot match it to a tax liability.

- improve its digital platforms

- identify compliance risks

- keep its website up to date and accessible

- collect customer feedback better.

Reducing the suspense account

If SRO receives a payment that it cannot link to a taxpayer’s liability or refund to the taxpayer, it puts it in its suspense account. The payment sits in the suspense account until SRO:

- can match it, or

- confirms it was an error and refunds the taxpayer.

Resolving unmatched payments is a complex and resource-intensive process. As a result, reducing the number of payments that go into its suspense account in the first place saves SRO time and money.

Historically SRO has had processes to reduce the number of unmatched payments. However, these processes have not led to a long-term reduction.

The value of SRO’s suspense account has been increasing since 2017, except for periods where SRO put extra resources into reducing it.

SRO started a project in July 2022 to reduce the:

- value of its suspense account to $50 million by 31 December 2022

- number of payments that go into its suspense account.

To achieve this, SRO put extra resources into:

- evaluating and resolving existing unmatched payments

- analysing the root causes of unmatched payments

- enhancing its system to help it allocate payments correctly.

This project immediately decreased the value of the suspense account.

SRO must continue to monitor the effectiveness of this project over the long term.

Improving digital platforms

SRO has put significant effort into streamlining its tools and processes for taxpayers. It has done this by creating digital platforms for major taxes, including:

|

Tax |

Digital platform |

|---|---|

|

Payroll tax |

PTX Express |

|

Land tax |

My Land Tax |

|

Land transfer duty |

Duties Online |

These platforms:

- let taxpayers register, manage or self-assess their liabilities and pay tax online

- save taxpayers and SRO time, money and effort by reducing manual processing

- provide suitable options to meet taxpayers’ varying needs.

SRO promotes its digital platforms and electronic payment processes as the most efficient payment option for taxpayers. As a result, SRO:

- received 97 per cent of its payments electronically in 2020–21, compared to 85 per cent in 2016–17

- received 4,063 cheque payments in 2020–21, compared to 152,417 in 2017–18.

This has increased SRO’s efficiency by reducing the time it takes to process payments.

In 2018 Deloitte estimated that digitising SRO’s paper-based land transfer duty forms into a combined 'digital duties form' will save taxpayers and SRO $13.6 million per year from 2017 to 2026 through:

- compliance cost savings

- administrative cost savings.

SRO has also estimated that the impact of further digitising the land transfer duty process will save it and taxpayers $44 million over a period of 5 years from 2021. But SRO has not separated these cost benefits into benefits for taxpayers and benefits for itself.

SRO is planning to further streamline its digital platforms by aligning:

- how taxpayers log in to different SRO platforms

- how it manages taxpayers’ accounts across different taxes, including taxpayer registrations and objections

- data from taxpayers' accounts across different taxes to reduce duplication.

Identifying compliance risks

SRO has a compliance strategy that outlines how it systematically detects, analyses and evaluates compliance risks. It reviews this strategy annually.

To find and manage compliance risks SRO uses:

- revenue line profiles for each major tax (see Figure 3D)

- investigative tools, guidelines, procedures and protocols.

Figure 3D: Case Study: SRO’s revenue line profiles

SRO uses its revenue line profiles to identify, assess, rate and rank compliance risks for its major taxes.

The revenue line profiles also:

- describe SRO’s controls to address each risk

- identify the responsible owner for each control

- set timeframes for SRO to review risks and its controls.

For example, SRO's revenue line profile for payroll tax identifies 22 risks. It has a risk assessment calculator to assess each risk's probability, impact, rating and level.

It also has a risk treatment schedule that outlines how SRO plans to address each risk.

The table below shows an example of a risk treatment schedule for a payroll tax compliance risk.

|

Description of risk |

Failure to lodge/pay tax returns on time |

|

Rank |

4 |

|

Risk rating |

15 |

|

Strategies to address risk |

Monitor taxpayers who fail to lodge/pay and issue default assessments/penalties |

|

Responsibility |

Responsible SRO business unit |

|

Agreed action |

Issue monthly default assessments to taxpayers in a timely manner |

|

Timetable for action |

Monthly (subject to the completion of the annual reconciliation) |

|

Additional strategies recommended after review |

Ongoing |

Source: VAGO based on SRO's 2021 revenue line profile for payroll tax.

A residual risk is a risk that remains after an agency has applied risk controls.

However, SRO could not show us that it:

- regularly assesses its risk controls

- reviews residual risks

- revises its controls for high residual risks.

We examined SRO’s 2021 revenue line profiles and found it had not revised:

- the rank or rating for any of the risks it identified in 2020–21

- any of its risk controls.

SRO told us it reviews its controls at a business-unit level. It does this on a monthly or ongoing basis depending on the risk level. But we did not find evidence of this in any of the internal reports we assessed.

SRO can use some of its non-specific scorecard measures to broadly assess if it is improving back-end compliance.

However, it cannot use these measures to assess if its individual controls effectively reduce specific risks.

Keeping its website up to date and accessible

SRO consistently updates its website and online education tools to help taxpayers understand and meet their obligations.

Its website also meets the government’s guidelines for making digital content accessible in languages other than English.

Website and education tools

SRO’s website is comprehensive, easy to navigate, written in plain English and offers a variety of educational tools for taxpayers.

SRO also has other educational services for taxpayers who are already aware of SRO and their obligations, such as webinars and digital newsletters.

SRO acknowledges there is room to increase its education initiatives.

For example, SRO has processes to identify when a person’s property portfolio reaches the land tax threshold. However, if more potential taxpayers were aware of their obligations, then SRO would not need to identify and notify them. This would save SRO effort and help it reduce the tax gap.

Access to tax information in other languages

The Multilingual Information Online: Victorian Government Guidelines on Policy and Procedures helps government departments and agencies make their websites and digital channels accessible in languages other than English.

We assessed SRO’s website against the Multilingual Information Online: Victorian Government Guidelines on Policy and Procedures.

SRO’s website meets the guidelines because it supplies interpreters to help taxpayers access information in languages other than English.

However, SRO could include logos on its main home page to make it easier for people to select their language and:

- access SRO’s services

- comply with their obligations.

Collecting customer feedback better

SRO has a BP3 target to achieve 85 per cent customer satisfaction. DTF reported that SRO has met this target since 2017.

However, the method SRO used until 2021–22 to calculate customer satisfaction was not sufficient or transparent. This is because:

- SRO only calculated it using a survey it ran approximately every 2 years

- the survey only related to SRO’s call centre customer service

- the survey’s sample size was too small to be meaningful.

Voice of the Customer project

In May 2022 SRO started a program called ‘Voice of the Customer’. This program will significantly improve how SRO collects and understands customer feedback.

SRO will survey a considerable proportion of taxpayers who have used its services on an ongoing basis. It will use the feedback to:

- identify where it needs to make improvements

- inform the BP3 customer satisfaction target.

However, it is not easy for taxpayers to proactively give feedback or make complaints outside of the program.

Taxpayer feedback and complaints

SRO’s phone menu does not have a specific feedback or complaint option.

Its website explains how to make a complaint and directs taxpayers to a ‘contact us’ form. However, this is a general enquiry form. It does not let users specify if they are making a complaint.

SRO’s process to categorise taxpayers' feedback and complaints is not transparent. This is because SRO officers manually assess what submissions are complaints or feedback.

SRO also does not centrally record all feedback and complaints. While it reviews feedback, it is potentially missing opportunities to improve how it uses it to inform its operations and improve its work practices.

SRO’s Voice of the Customer program will partially improve its taxpayer feedback processes. But SRO could consider using this program to make it easier for taxpayers to make a complaint, compliment or provide feedback.

3.3 Customer service response times

One of SRO’s goals in its strategic plan is to make it as easy as possible for taxpayers to comply with their obligations.

However, since 2018 SRO has been taking longer to:

- respond to taxpayers’ phone calls

- allocate, and therefore resolve, taxpayers’ objections.

Response times for phone calls

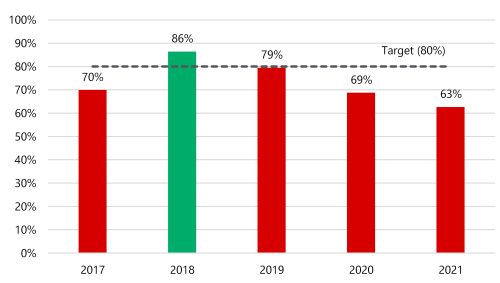

SRO has a scorecard target to answer more than 80 per cent of phone calls within 300 seconds.

SRO's performance against this target has varied over the last 5 years and worsened since 2018. It did not meet the scorecard target in 2017, 2021 or 2022.

We looked at SRO’s collective phone response times for all the taxes we assessed. These are not all the taxes SRO includes in its scorecard reporting. But from 2017 to 2021, between 75 to 90 per cent of SRO’s total calls were about the taxes we assessed.

As Figure 3E shows, SRO has not met the target for the taxes we assessed since 2018.

Figure 3E: Percentage of phone calls answered* within 300 seconds for taxes we assessed

Note: *SRO counts phone calls that taxpayers hang up within 300 seconds as answered.

Source: VAGO.

SRO’s decline in performance is not due to increased demand. Call volumes for the taxes we assessed decreased by 17 per cent between 2018 and 2021.

The target is also not transparent because SRO counts calls that taxpayers hang up within 300 seconds as ‘phone calls answered’.

SRO analyses call trends daily to reduce wait times. However, its wait times have continued to increase.

Longer wait times:

- impede SRO’s strategic goal to ‘make it easier for our customers’

- reduce taxpayers’ satisfaction

- make it harder for taxpayers to get the help they need to comply with their obligations.

SRO allocated 15 more staff to answer phone calls in December 2022 to address these issues.

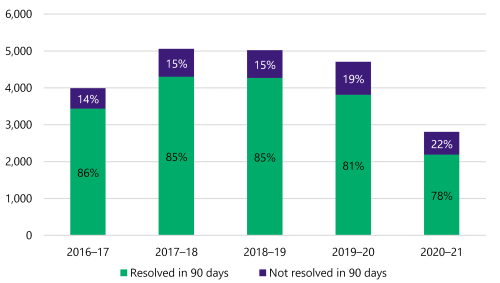

Allocation times for taxpayer objections

If a taxpayer disagrees with SRO’s assessment of their tax liability, they can lodge an objection. SRO allocates objections to its officers to resolve.

SRO has a BP3 target to resolve at least 80 per cent of taxpayer objections within 90 days.

Figure 3F shows SRO’s timeline for resolving objections.

Figure 3F: SRO’s timeline for resolving objections

Note: VCAT stands for the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal.

Source: VAGO.

Allocation time is the amount of time it takes for an SRO officer to start resolving an objection after SRO creates a case file for it.

Resolution time is the amount of time it takes for SRO to resolve an objection after it creates a case file for it.

We examined SRO's allocation and resolution times for private rulings and objections. We also reviewed SRO's relevant internal procedure manuals.

SRO’s average allocation time was 9 days longer in 2020–21 than in 2018–19.

As Figure 3G shows, this led to SRO not meeting its target to resolve 80 per cent of objections within 90 days in 2020–21. This is despite taxpayers objecting to fewer assessments in that financial year.

Figure 3G: Number of assessments taxpayers objected to and the percentage resolved within 90 days

Source: VAGO.

SRO has not analysed why its allocation times have increased or how this has affected its resolution times.

SRO’s internal documents also have 3 different descriptions of when it starts measuring the 90 days. The Tax Act says the 'date received' is the starting point but none of SRO's descriptions are consistent with this.

Under the Tax Act, a taxpayer can have their objection referred to the Victorian Civil and Administrative Tribunal or the Supreme Court of Victoria if SRO does not resolve it within 90 days. Resolving objections in court is more expensive and time consuming for both SRO and taxpayers.

Appendix A. Submissions and comments

Download a PDF copy of Appendix A. Submissions and comments.

Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

Download a PDF copy of Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary.

Appendix C. Scope of this audit

Appendix D. Comparing SRO’s BP3 and scorecard performance measures

Download a PDF copy of Appendix D. Comparing SRO’s BP3 and scorecard performance measures.

Download Appendix D. Comparing SRO’s BP3 and scorecard performance measures