School Councils in Government Schools

Overview

School councils of government schools operate within a complex and unique governance framework, sharing governance responsibilities with the principal of their school and the Department of Education and Training (DET). Because the governance framework of government schools is unique, it is particularly important that the roles, responsibilities, limits of authority and accountability of those involved are clearly defined and well understood, and that the framework works well in practice.

School councils’ role within government schools is not insignificant. As of February 2017, school councils operated in 1 534 government schools that served over 600 000 students. In 2016–17, Victorian school councils were responsible for budgets totalling $1.65 billion. School councils’ activities have a real impact on students and their school community’s confidence in the way they are managed.

DET is responsible for ensuring that school councils understand the governance framework, for overseeing their activities and for advising the Minister for Education on their performance.

In this audit, we examined whether school councils are meeting their objectives under the Education and Training Reform Act 2006. In doing so, we considered DET’s guidance, and whether DET effectively oversees school councils and keeps the minister informed on their performance.

We made five recommendations for DET.

Transmittal Letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER July 2018

PP No 420, Session 2014–18

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report School Councils in Government Schools.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

26 July 2018

Acronyms and abbreviations

| CEO | chief executive officer |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| ETR Act | Education and Training Reform Act 2006 |

| FM Act | Financial Management Act 1994 |

| IBAC | Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission |

| ISG | Improving School Governance |

| MOU | memorandum of understanding |

| PA Act | Public Administration Act 2004 |

| Regulations | Education and Training Reform Regulations 2017 |

| SPAG | School Policy and Advisory Guide |

| SPOT | Strategic Planning Online Tool |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VRQA | Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority |

Audit Overview

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006 (ETR Act) establishes school councils within Victorian government schools and outlines their objectives. These include to ensure efficient governance of the school, make decisions in the students' best interest, enhance educational opportunities and ensure the school complies with its legislative obligations.

The ETR Act also specifies responsibilities of school councils, which include strategic planning and financial administration. School councils are required to inform their school community about their school's performance against its strategic plan and budget.

School councils operate within a complex and unique governance framework. They share governance responsibilities with the principal of the school and the Department of Education and Training (DET). The framework cannot be compared directly with other well‑documented and understood governance structures, such as a board of directors for a private or public entity. The framework also differs from non-government schools—which are not part of DET and have their own governing arrangements.

Because the governance framework of government schools is unique, it is particularly important that the roles, responsibilities, limits of authority and accountability of those involved are clearly defined and well understood, and that the framework works well in practice.

DET is responsible for ensuring that school councils understand the governance framework. The ETR Act requires DET to establish an assurance regime over the financial and operational activities of school councils. DET is also required to advise the Minister for Education (the minister) on how school councils perform their functions and meet their objectives.

School councils' role within government schools is not insignificant. As of February 2017, school councils operated in 1 534 government schools that served over 600 000 students. In 2016, Victorian school councils were responsible for budgets totalling $1.64 billion. School councils' activities have a real impact on students and the wider school community.

In this audit, we examined whether school councils in government schools are meeting their objectives under the ETR Act. In doing so, we considered DET's guidance to school councils on their roles and responsibilities offered through its guide Improving School Governance (ISG). We also considered whether DET effectively oversees school councils and has an assurance regime over their activities. In our assessment, we have not distinguished between the role of the Secretary of DET and the role of DET itself.

Conclusion

School communities cannot be assured that all school councils of government schools are fulfilling their objectives and functions, nor that they are operating effectively.

This is largely because the role of school councils and the performance expectations of their members remains ill defined and is not well understood. This lack of clarity leaves school council objectives open to widely varying interpretations and creates confusion about the boundaries between the roles of the principal and the school council. Consequently, school councils interpret and therefore carry out their role in various ways, and at times are unable to resolve conflicts with school principals.

DET has improved its guidance to school councils since 2015. However, there are still gaps in its guidance and their advice on school councils' role and the full extent of their functions is confusing. The guidance is not clear about school councils' accountabilities or DET's role in overseeing their performance on the minister's behalf. DET's guidance causes further confusion by requiring school councils to comply with its policies—even though the minister has not delegated this power to DET to date. DET can do more to clarify these roles and provide school councils with practical guidance to address areas of ambiguity.

A further barrier to knowing whether school councils meet their objectives is a lack of performance evaluation, both within school councils and by DET. To date, school councils have not routinely undertaken performance self-assessments, a recognised better practice and, for councils of schools formed after July 2005, a requirement. DET also does not have an assurance regime for the non-financial operations of school councils commensurate with its oversight of their financial operations. Further, it has not used its authority under the ETR Act to review and oversee school council performance. As such, it cannot reliably assure the minister that school councils are meeting their objectives under the ETR Act.

Given the critical remit of school councils, failure to create and act on a more robust performance system represents a missed opportunity to continually improve the functioning of Victorian government schools.

Findings

School council role, establishment and accountability

The role of school councils

DET has not explained the policy intent of school councils in the school governance framework and why the ETR Act allocates specific roles and responsibilities to them.

The ETR Act's school council objectives provide the basis for the school council role. However, the terms used to define those objectives are open to interpretation.

Ambiguous phrases in the legislative objectives include:

- 'assist in efficient governance'

- make decisions in the 'best interests of students'

- enhance 'educational opportunities'.

DET has not provided specific guidance on how they are intended to apply in practice. Without guidance, school council members and principals can and do interpret each legislative objective differently, making it difficult to reach decisions and resolve disputes.

School councils perform multiple roles that include advising the principal, making decisions on specific issues, and consulting with the school community. The school council and principal also co-sign the school's strategic plan and all payments from the school's official bank account. While DET has provided guidance to school councils on school governance, it lacks information on these different roles or when they apply.

School councils are accountable directly to the minister—who has the power to require them to comply with policies. While the minister has the authority to delegate this power to DET, there is currently no delegation. Despite this, DET explains in its guidance that school councils are required to comply with its policies.

Under the ETR Act, there are functions that school councils are exclusively accountable for and others that they share with principals. Yet school councils do not have decision‑making authority over principals because they do not employ the principal. DET guidance does not clarify decision-making authorities. As a result, to effectively make and implement decisions, school councils and principals rely on the willingness of both parties to work together.

We surveyed school principals and school councils. Of the 1 004 schools that participated, many school councils told us that they have a productive relationship with their principal. We found that challenges can arise when school councils disagree with their principal. During term two of 2018, DET introduced guidance for school councils to help them to resolve disagreements between council members and to manage conduct of individual members.

However, DET's guidance does not explain the avenues through which school councils can seek advice independently of the principal when a dispute arises between them. The process also requires school councils to work through DET's regional officers even though these officers are responsible for providing support to the principal in their day-to-day work. The absence of clear boundaries of roles constrains DET's ability to work with both school councils and principals to resolve governance disputes.

As a last resort, DET's process involves a formal investigation of a dispute. However, as the employer of the principal, DET is ultimately constrained in conducting an independent and transparent investigation.

Through our survey, we found that over 60 per cent of the comments made by school principals and school council presidents identified decision‑making as an emerging challenge.

In responses to our survey, school councils were confident that they understood their role and how it differs from that of the principal. However, there was variation in how school councils understood their role, even though it should be the same across schools.

Around two-thirds of respondents (63.8 per cent) stated that school councils operated as a body working in partnership with the principal. In 2015, DET stopped referring to a partnership between school councils and principals. However, some schools continue to use this terminology on their websites. In their role as executive officers, school principals are required to implement certain school council decisions. To view the school council role as a partnership with the principal blurs the demarcation of responsibilities between school councils and the executive officer.

In our survey, 10 per cent of respondents considered a school council to be the 'body governing the school'. DET uses the term 'governing body' to describe school councils. However, given the shared governance roles across DET, principals and school councils, the phrase 'body governing the school', in the way it would ordinarily be understood, does not accurately describe school councils' role.

Establishing and sustaining school councils

DET relies on its principals to comply with ETR Act requirements for the election and composition of school councils, while complaints it receives alert it to noncompliance. DET offers support and guidance to principals to manage election of school council members and ensures that they declare details in its membership database—known as Schedule 7—by 30 April each year. Principals are required to record appointed members, office bearers and vacant member positions.

School councils are legally allowed to operate with member vacancies. However, they must achieve a quorum for each meeting to proceed and to make decisions. For school council meetings to achieve a quorum, non-DET members must outnumber DET employee school council members. Where vacancies are concentrated in parent or community membership categories, the risks of not meeting quorum increases.

DET does not monitor the Schedule 7 database to identify this risk. It relies on school principals and school councils to monitor their own vacancies and to address any membership issues. However, DET does monitor whether school councils are meeting quorum requirements. In its audits conducted in 2016–17, DET found that of the 267 schools audited, 38 schools did not meet quorum requirements (around 14 per cent). DET's audits did not identify whether school councils continued to make decisions without a quorum.

Where these vacancies are concentrated in certain membership categories, and decisions are made without a quorum, decisions may also be dominated by particular members or member groups. For example, where vacancies are concentrated within parent or community member categories, DET employee members may have greater influence over decisions. This risk is increased by DET employee members having greater access to information through DET's newsletters and notifications.

School councils frequently experience challenges recruiting members who possess the appropriate knowledge, skills and time. To address such capability gaps, school councils can co-opt skilled members from their wider communities.

DET provides guidance to school councils to help them assess their own skills and identify the skills they may require. However, without clarity on the role of the school council, the usefulness of this guidance is limited. Across the 1 004 schools we surveyed, only 15 per cent of respondents had developed a skills matrix to identify skills they needed on their school council. Without clarity on their role, school councils are not able to identify the specific skills they require and, as a result, to know whether they have the right mix of members.

Accountability

While the ETR Act refers to school councils' accountability and performance requirements, DET does not explain to school councils its assurance activities or how these relate to a school council's role in overseeing school compliance. DET has also not provided clear guidance on the full list of school council functions or how school councils are accountable to the minister for their performance.

School councils and principals operate within complex accountability arrangements within the governance framework:

- School councils are accountable to the minister for their functions.

- As the school council's executive officer, the principal is accountable to the school council for responsibilities defined in the ETR Act.

- The principal is also accountable to DET as an employee and is subject to a DET performance process.

DET provides guidance to principals on their dual roles as principal and executive officer of the school council. However, as the principal's employer, DET has not established processes to enable school councils to have input into principals' performance evaluations. As a result, school councils are not able to ensure that principals, in their role as their executive officer, meet their obligations to the school council as established under the ETR Act. This includes implementing school council decisions and providing effective executive support.

DET does not provide adequate information on how school councils can effectively delegate their powers, duties or functions to a principal or to school council subcommittees. When they delegate, school councils retain ultimate responsibility—yet DET does not provide specific guidance on how school councils can establish processes to monitor their delegations. The effectiveness of such delegations relies on school councils being able to ensure their principals are accountable for the delegation, and on the implementation of an effective dispute‑resolution process.

School council performance

DET does not use its authority to conduct effectiveness and efficiency reviews of school councils and DET's reviews of school performance do not consider performance of the school council. The key form of performance review for school councils is their own self‑assessment. However, our survey results showed that only 33 per cent of school councils conducted annual self‑assessments.

DET is required to provide guidance to school councils, and work with them, on governance.

Changes to the Public Administration Act 2004 (PA Act) require school councils established after 1 July 2005 (when the amendments were introduced) to assess their own performance and those of each school council member. In its ISG guide, DET has not explained that this legal responsibility applies to only 117 school councils—8 per cent of Victoria's 1 534 schools.

During our audit, DET updated its guidance to state that all 'school councillors are required to undertake the school council self-assessment tool each year, as part of the school's annual self-evaluation process'. However, DET's guidance does not explain the source of this requirement, nor that it does not apply to most school councils.

Self-assessments are an important best-practice tool for reflecting on school councils' effectiveness. DET advised us that the tool could form part of its assurance regime over school council activities. However, DET is yet to explain its authority to place such a requirement on school councils.

Although DET provides a school council self-assessment tool, it does not provide recommended performance measures on all school council objectives, functions or other legal obligations. It also does not provide benchmarks to assist them to review their performance.

Departmental guidance and support

DET has improved the guidance it provides to school councils. In 2015 it released its ISG guide, a resource for school council members, supplemented by face-to-face training at no cost to the school. It also supports school councils by offering assistance through its dedicated School Operations and Governance Unit and through school principals.

DET provides guidance directly to schools on required policy and procedures through a dedicated online resource—the School Policy and Advisory Guide (SPAG). School council members can access this resource online.

While the ISG guide is a substantial improvement on what was previously available, further improvements are required to provide easily accessible information to school councils. DET's guidance to school councils is difficult to find on its website. It lacks a central page to direct school councils to the five separate public pages and multiple internal pages that are relevant to them.

Further, not all school council members can access DET's guidance material—access to guidance on DET's internal pages is limited to principals, school council presidents and DET employees who have a DET eduMail account. This results in an imbalance in the information available to each council member to inform their decisions. We found that there is a low rate of school council presidents accessing their eduMail accounts—during the four-week period of our survey, only 28 per cent accessed their accounts.

Although DET can provide ministerial orders on request, neither the principal nor school council members have direct access to the system that contains all ministerial orders relevant to their responsibilities.

Since term three of 2015, DET has offered training to support school council members to confidently and effectively fulfil their role. However, it does not have an implementation plan to ensure the training is achieving its intended objectives and sufficiently reaching its audience. Face‑to‑face training sessions are not always suitable for council members who have family and work commitments. In our survey, school council presidents told us that their members were positive about what they learned in DET's training sessions. DET conducts end-of-session evaluations of its training, however it has no measures in place to evaluate training effectiveness.

DET communicates the assistance it offers through its School Operations and Governance Unit. However, during our school council forums we conducted, we found that school councils had a low awareness of the dedicated assistance DET provides to them. DET could do more to improve this awareness by actively promoting the assistance, support and legal advice it provides to school council members and providing information about how to access it.

Departmental oversight

DET has only partially used its powers under the ETR Act to establish systems or processes to oversee the performance and compliance of school councils.

DET has established quality assurance processes for school council financial activities. It oversees the financial activities of school councils though monitoring and auditing as part of its risk-based School Council Financial Assurance Program. DET has found that school councils have not always adequately overseen their financial controls—in such instances, DET follows up school councils that are failing to meet their obligations, as well as working to improve its financial guidance and training for principals, business managers and school councils.

However, DET has only partially met its obligations under the ETR Act to oversee the operational activities of school councils. While DET has some assurance activities in place, it has not implemented an equivalent risk-based assurance regime over school councils' operational activities as it has for their financial activities. DET has neither identified what school council 'operational activities' exist under the ETR Act and its associated legal instruments, nor has it interpreted the requirement for a 'quality assurance regime' over these activities. During our audit, DET was in the process of reviewing its interpretation of requirements under the ETR Act and its obligations.

The ETR Act also provides DET with the power to conduct effectiveness and efficiency reviews of school councils. However, since the introduction of the ETR Act in 2006, DET has not conducted such a review for any school council or developed a system to determine when it would undertake such a review.

As such, DET is not well positioned to identify emerging risks or advise the minister of any performance issues relating to the non-financial activities of school councils.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Department of Education and Training:

1. provide an interpretation of the policy intent of school councils under the Education and Training Reform Act 2006, to clarify the objective of school councils and the role of all entities within the governance framework (see Section 3.3)

2. update its guidance and training for school councils to reflect the clarified interpretation of school council objectives and their role in the governance framework (see Sections 2.2 and 3.3)

3. implement and evaluate a support strategy for school councils that includes:

- effective communication processes with school council members

- a clearly identifiable page on its school council website to enable them to readily access all information relevant to their role

- clearly identifying and promoting the departmental assistance available to school councils in their role

- targeting training activity to improve the capacity and capability of school councils to fulfil their objectives (see Sections 2.2 and 2.3)

4. determine the nature of the assurance regime that the Education and Training Reform Act 2006 requires the Department of Education and Training to establish over school councils, and implement additional assurance measures as required (see Section 2.4)

5. establish a process for annual reporting to the Minister for Education on school council performance (see Section 3.4).

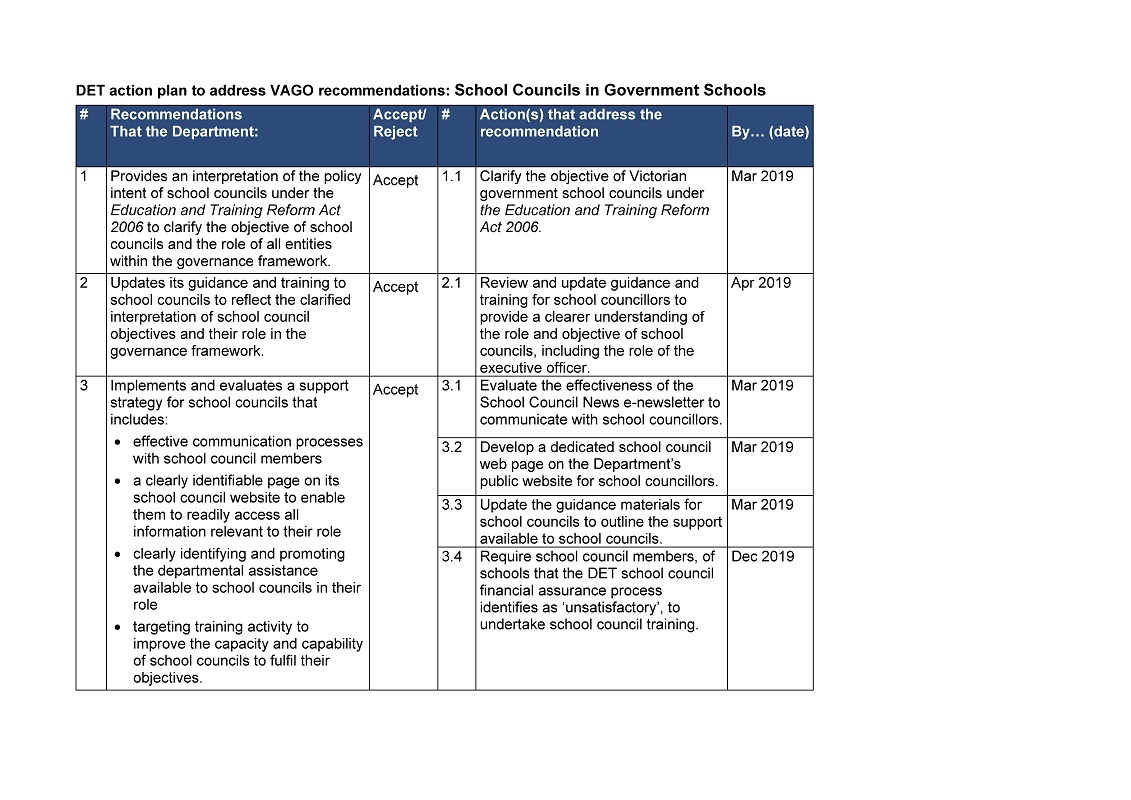

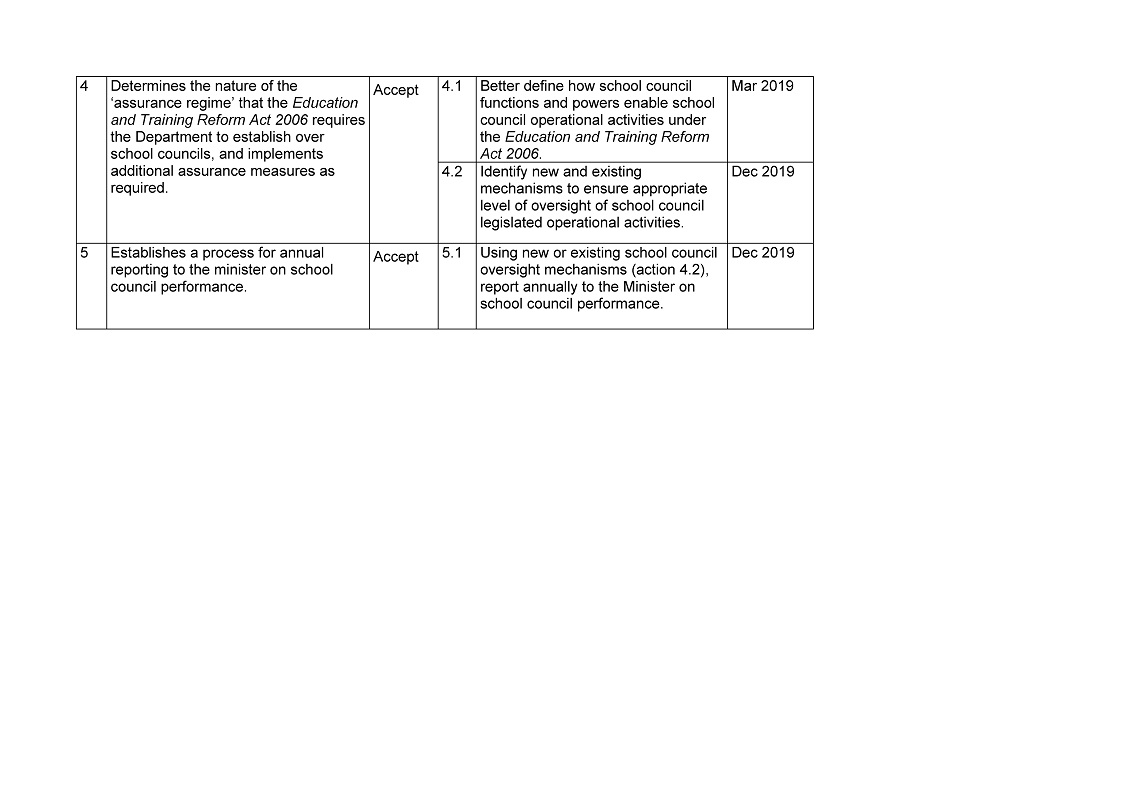

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DET and the Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority (VRQA), and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to them and asked for their submission or comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

DET provided a response which is summarised below. The full response is included in Appendix A.

DET welcomed the findings of this audit and provided an action plan outlining its planned activities to address our recommendations.

1 Audit context

School councils are part of the governance framework for Victorian government schools.

Under the ETR Act, the objectives of school councils are to:

- assist in the efficient governance of the school

- make decisions in the best interests of students

- enhance the educational opportunities of students at the school

- ensure schools and school councils comply with their legislative obligations.

To achieve their objectives, school councils have functions that relate to strategic planning, finances and community engagement.

The clarity of the governance arrangements—including school councils' role (as defined by their objectives), their responsibilities (as defined by their functions), the limits of their authority and their accountability—is an important underpinning for school councils to meet their obligations. In turn, high‑performing school councils enable schools to perform efficiently and effectively and respond strategically to changing demands and educational challenges. They can also strengthen the confidence communities have in their schools.

1.1 The changing role of school councils

Victorian government school communities first provided an advisory role to principals through boards of advice. Their main role was to report to the government on the condition of school buildings.

In 1975, the government established school councils with extended powers and greater authority for making decisions, particularly over school finances.

In 1998, the government passed legislation that gave school councils the option to choose to operate as a self-governing council, which included the power to employ all school staff, including the principal. Some 51 schools chose to adopt this model. In 2000, the incoming government revoked these powers, transferring all staff employed by school councils back to DET. The introduction of the ETR Act further clarified the responsibilities and powers of school councils.

Today's governance framework is complex and unique to Victorian government schools. The framework provides school councils in Victoria with greater powers than in other states and territories, but not the equivalent self‑governing powers of many boards of governance in the public and private sectors.

School councils are not legally responsible for all aspects of a school's operations—their responsibilities are limited to the obligations outlined in the ETR Act. They are also not responsible for the core purpose of the school—the educational outcomes of students. However, they are responsible for enhancing educational opportunities. DET is responsible for most of the school's operations.

The underlying rationale for this governance framework is to distinguish government schools from non-government schools and to maintain their public nature. The governance framework also recognises that the risks and liability associated with administering the government school system rests with the State of Victoria.

1.2 Overview of the governance framework

School councils are one part of the complex governance framework of Victorian government schools. They share responsibilities with the minister and DET, as shown in Figure 1A.

The framework has the following features:

- DET is responsible for the ongoing operation and performance of government schools:

- Schools are an operational arm of DET.

- School principals manage schools under DET's delegation.

- DET oversees principals' performance.

- All 1534 school councils in operation are separate legal entities from DET and its schools:

- The school principal is a school council member and its executive officer.

- Principals are accountable to the council in terms of providing them with adequate advice and resources and implementing their decisions.

- The school council has limited authority to hold the executive officer to account.

- School councils are directly accountable to the minister for assisting in the efficient governance of schools:

- DET is responsible for advising and assisting the minister in holding school councils accountable for their statutory obligations.

- DET can conduct efficiency and effectiveness reviews of school councils.

- DET is required to have a quality assurance regime to cover the legislated activities of school councils.

Figure 1A

Victorian government school governance framework

Note: Solid lines represent accountability; dotted lines represent responsibility.

Source: VAGO.

1.3 Legislative framework

The legislation relevant to Victorian government schools, including school councils, includes the ETR Act, the PA Act and the Financial Management Act 1994 (FM Act).

Education and Training Reform Act 2006

The ETR Act establishes the governance framework for the Victorian government school system and makes the minister responsible for Victorian government schools.

Legal instruments associated with the ETR Act include the Education and Training Reform Regulations 2017 (the Regulations) and ministerial orders, directions, guidelines and policies issued under the ETR Act.

The ETR Act sets out school councils' objectives, functions, powers and duties.

Minimum standards for registration

In fulfilling their functions, school councils must ensure that their school and the school council complies with the ETR Act.

The ETR Act prescribes minimum standards that schools must meet for registration related to:

- school governance

- enrolment

- curriculum and student learning

- student welfare

- staff employment

- school infrastructure.

VRQA explains that these standards underpin five key pillars of a school—good governance, strong financial management, an effective curriculum, sound teaching practice, and a safe environment for children.

Public Administration Act 2004

The PA Act establishes the governance framework for the Victorian public sector. It makes the minister accountable to parliament for the performance of DET and school councils.

The PA Act treats school councils as governing entities and school council members as directors of a board. The PA Act establishes that school councils are accountable to the minister for the exercise of their functions. Council members are subject to provisions of the PA Act and bound by the Code of Conduct for Directors of Victorian Public Entities.

Amendments to the PA Act applying from 1 July 2005 provide further responsibilities for all governing entities—including school councils. These responsibilities include advising the relevant minister and their department about major risks and their strategies to manage them, and assessing the performance of their board and of individual directors.

The amendments only apply to governing entities established after the amendments were introduced. DET estimates that this applies to approximately 8 per cent of school councils—the 117 schools that opened after 1 July 2005. The minister has the power to apply these requirements to all other school councils but has not done so.

The PA Act establishes responsibilities for DET that relate directly to school councils. The PA Act makes DET responsible for holding school councils to account by advising the minister on matters relating to school councils, including the discharge of their responsibilities. It also requires DET to work with, and provide guidance to, school councils to assist them on matters relating to public administration and governance.

Financial Management Act 1994

The FM Act establishes government schools' financial administration requirements and aims to improve the financial accountability of the public sector.

The FM Act requires all public entities to maintain proper accounting records and systems. It also requires them to prepare an annual report of operations and financial statements.

In 2016, the Minister for Finance issued Standing Directions under the FM Act that specify the responsibilities of public sector agencies to achieve a high standard of public financial management and accountability.

The Standing Directions exclude school councils and other small entities from the mandatory requirements because, in most cases, their size and risk profile make many inappropriate. In excluding school councils, the Standing Directions require DET to impose on school councils an appropriate level of financial management accountability, governance and compliance arrangements.

1.4 Roles and responsibilities

Minister for Education

The minister is responsible for Victorian government schools. Under the ETR Act, the minister has the authority to set the overall policy for education and training in Victoria. The minister has powers, functions and duties that supplement the governance framework. These include the power to establish schools and school councils.

The ETR Act allocates to the minister, the power to issue policies, guidelines, advice and give directions that DET, schools and school councils must comply with. The minister can delegate to DET the power to issue policies that school councils must comply with. However, currently there is no general delegation in place. In 2018, the minister issued a ministerial order directing all school councils to comply with DET's Procurement Policy for Victorian Government Schools. The minister also issued a ministerial order directing metropolitan government schools to procure school cleaning services in accordance with arrangements approved by DET.

The minister is responsible for holding school councils accountable for their performance, based on the advice of DET.

Department of Education and Training

The ETR Act provides specific responsibilities to DET and its Secretary in relation to schools and school councils. Throughout this report, we have not distinguished between the responsibilities of the Secretary of DET and those of DET itself—we refer to all responsibilities as DET's responsibilities.

DET is accountable to the minister for implementing Victoria's education system. DET is responsible for the performance and compliance of Victorian government schools. DET's responsibilities include:

- employing school principals and teaching staff

- developing policies, processes and procedures that schools must follow

- establishing rules for school operational matters, such as curriculum, opening hours and student-free days

- planning and funding major capital works.

In relation to school councils, DET is specifically required to:

- impose an appropriate level of financial management accountability, governance and compliance

- establish asset management requirements proportionate to the collective value of those assets

- ensure that an effective quality assurance regime is in place over school councils' financial and operational activities

- provide guidance and assistance on matters relating to public administration and governance.

DET does not have the power to give directions to school councils. DET also does not have the general power to require school councils to comply with its policies, as the minister has not delegated this power to it.

DET is required to work with school councils and hold them accountable by reporting to the minister on their performance and how they discharge their functions under the ETR Act and its associated legal instruments. To do this, the ETR Act provides DET with specific oversight powers. It also authorises DET to conduct reviews on the effectiveness and efficiency of the operations of school councils. This includes examining the performance of their functions, operations and procedures.

School principals

The role of the principal is complex and multifaceted. In addition to managing the school and its programs, the principal has two roles in the context of school councils, to:

- participate as a voting school council member

- support the school council and implement its decisions as the executive officer.

Therefore, the principal is accountable to both DET and the school council, but only DET is responsible for overseeing the principal's performance.

Manager of the school

The principal is responsible for the day-to-day management of the school. This involves:

- determining the curriculum programs followed in the school

- selecting and managing permanent teaching staff—such as teachers and assistant principals—and allocating duties

- maintaining buildings and grounds

- ensuring the school complies with legislation and all departmental policies

- ensuring the safety and welfare of students and anyone working at the school.

School council executive officer

The principal is the executive officer of the school council—part of this role is like a company secretary to a board, and part of it reflects that of a chief executive officer (CEO), but neither is a perfect analogy.

As the executive officer, the principal is accountable to the school council for:

- ensuring that the school council receives adequate and appropriate advice

- implementing the school council's decisions

- adequately supporting and resourcing school council meetings.

School council member

The principal is an ex-officio member of the school council, with voting power. The Regulations specify that the principal is a school council member by virtue of that position. No other members of the school council are automatically appointed to the school council.

School councils

The minister establishes an individual school council as a body corporate through a ministerial order known as a School Council Constituting Order (constituting order).

As body corporates, school councils are:

- separate legal entities from DET, the school and the school's students and teachers

- public entities under the PA Act that must comply with relevant legislation and ministerial directions and guidelines.

The constituting order provides a governing document, without which a school council may not exist. It sets out the rules—in addition to the ETR Act, the Regulations and any other ministerial orders—that a school council must comply with to fulfil its obligations. It also outlines the member composition specific to each individual school councils, their powers and their reporting requirements.

School councils can create their own standing orders to detail additional school council rules to assist their operations. Standing orders must be consistent with school council legal requirements set out in the ETR Act and its associated legal instruments.

School councils are accountable to the minister for the performance of their functions established under the ETR Act. One of these functions is for the school council to perform any other function or duty, or exercise any power under the ETR Act, Regulations, a ministerial order or direction issued by the minister under the ETR Act. They also have an implied accountability to the school community—they must produce an annual report and present it to the school community.

School councils form one of the largest groups of public entities in Victoria. In 2017, DET had 19 080 active school council member positions available across 1 534 school councils. Of these, 17 600 positions (92.2 per cent) were filled.

Most school council members are volunteers who make a considerable commitment. Only the principal is required to be a member, which is a component of the position as principal. Members are required to attend and prepare for at least eight meetings per year. They are also encouraged to be involved in council subcommittees.

School councils have decision-making powers that can influence the direction of schools. In 2016–17, school councils were collectively responsible for budgets of approximately $1.64 billion, representing 2.5 per cent of the State Budget.

As shown in Figure 1B, in 2016, school councils were responsible for approximately 24 per cent of Victoria's school-related finances, comprising funding from the Commonwealth and state governments. It also included funding that school councils raised themselves from local sources, including fundraising activities and voluntary contributions from parents. School principals were responsible for the remainder.

Figure 1B

Responsibility for school-related finance in 2016

Source: VAGO based on data provided by DET.

At 30 June 2017, school councils shared oversight with DET for $20.4 billion worth of property, plant and equipment—including $9.41 billion of land and $10.99 billion of buildings, improvements, plant and equipment. This property portfolio made up 17 per cent of the value of Victoria's government-owned assets during the previous financial year, one of the largest state-owned asset portfolios in Victoria.

Size and membership

The school council's constituting order specifies the size of the school council, its membership categories and its election procedures.

Victorian government school councils vary considerably in their size, revenue and expenditure, and level of financial risk. In 2016, the school council of one of Victoria's smallest schools was responsible for authorising $31 170 in expenditure for five students. In contrast, the school council of one of Victoria's largest schools authorised $7 million in expenditure for 1 373 students.

In 2017, the size of school councils in Victoria defined in their constituting orders ranged from five to 18 members. As shown in Figure 1C, the majority of school councils should have between 12 and 15 members if all positions are filled.

Figure 1C

School council size in 2017, as determined by the minister

Source: DET's school council membership database called Schedule 7.

School council membership is sourced from two mandatory categories—'parent' and 'DET employee'. There is also an optional 'community' category and a 'nominee member' category that can be used to appoint members who have specific skill sets. For example, where a children's hospital has a school for its patients to attend, hospital staff may be appointed in the nominee member category for their medical skills.

The school community votes to elect parents and DET employees to the school council. School councils can also co-opt members rather than elect them if their constituting order permits this. In addition to setting the number of members required in each category for each school, the school's constituting order also specifies how many community members and/or nominee members a council has.

Since term two of 2018, secondary school councils have two new mandatory student category positions unless they have been exempted. These are in addition to the nominee and community categories.

Subcommittees

Under the ETR Act, school councils can form subcommittees. DET encourages school councils to have a finance subcommittee, but school councils might also have subcommittees for buildings and grounds (facilities), education policy, student leadership, information technology, community building, and community relations. The school council may also have a subcommittee for outside-school-hours care or a canteen if the school provides such services.

Roles and responsibilities

The role of school councils is defined by their objectives established in the ETR Act, to:

- assist in the efficient governance of the school

- make decisions in the best interests of students

- enhance the educational opportunities of students at the school

- ensure schools and school councils comply with their legislative obligations.

The ETR Act also describes the functions of school councils, detailed in Figure 1D. This list also includes a provision for school councils to fulfil any other function or duty, or exercising any power established through the ETR Act, Regulations, a ministerial order (see Appendix B) or direction issued by the minister under the ETR Act.

Figure 1D

School council functions

|

Under the ETR Act, school councils must:

|

Note: Refer to ETR Act for exact phrasing of school council legal functions.

Source: VAGO based on the ETR Act.

DET's guidance categorises the responsibilities of school councils into three broad areas—strategic planning, finance and assets, and policy development and review. School council responsibilities also include community engagement.

Strategic planning

The school council establishes the broad direction and vision for the school through its school strategic plan. The ETR Act requires this plan to set the school's goals and targets for the next four years and the strategies for achieving them. The strategic plan is informed by DET's review of the school's performance against its previous strategic plan, which school councils participate in.

The ETR Act requires that both the principal and school council president sign the plan and submit it to DET for approval.

The ETR Act also requires school councils to produce an annual report on the school's progress against its plan and on its financial activities. The school council must publish its annual report and make it available to the school community.

Finance and assets

Finance

|

The ETR Act defines the financial activities of school councils. They include responsibility for:

|

The ETR Act allocates the school council separate financial responsibilities from those of the principal.

Principals are responsible for budgeting for their schools' teaching staff, including those of the senior leadership team. However, DET employs the staff and holds the funds to pay them directly.

School councils are responsible for the school's official budget as it relates to running the school. School councils are responsible for the school's official bank account which is in the school council's own name.

DET provides funds to each school by placing it in an intermediate account. School councils can transfer these funds into their school's official account. They can also raise their own funds from local sources—including contributions from parents. School council fundraising activities are subject to the Fundraising Act 1998, which sets out obligations related to collecting funds and disclosing information.

From the school's official account, the school council pays the school bills—for example, funding goods, services, facilities and equipment required to operate the school. The school council has the power to enter into contracts and agreements on behalf of the school. The school council also has authority to employ staff—including teaching staff≠, but only on terms less than 12 months.

The school council is required to authorise and verify every payment that is made—in this way, the school council engages with a school's finances at a detailed, operational level. This is distinct from governing boards in public and private entities, which generally have a monitoring role rather than an operational role.

Assets

The ETR Act allocates responsibility for school buildings and grounds to both the school council and to DET. The school council is responsible for the oversight of school buildings and grounds, and ensuring that they are kept in good condition.

DET is responsible for ensuring that the assets of Victorian schools are managed efficiently and effectively. DET delegates its responsibility to school principals and requires them to create, implement and manage a plan for the development and general maintenance of school buildings and grounds.

Community engagement

The ETR Act allocates school councils with specific community engagement responsibilities. Members are required to inform themselves of the views of the school community when making decisions, along with stimulating interest in the school within the wider community.

The school community primarily includes staff, students and parents. It may also include early childhood services, service clubs, organisations or businesses.

Policy development and review

Under the ETR Act, school councils must ensure the school complies with any requirement issued within the ETR Act or its associated legal instruments, including the minimum standards for school registration. These standards require schools to put in place certain policies and procedures. As schools are extensions of DET, DET is also responsible for schools' compliance with these standards.

Through ministerial orders, the minister may place specific requirements on school councils in relation to school policy requirements. For example, through Ministerial Order No. 870, the minister has specifically required school councils to ensure that their school complies with the minimum standard relating to the risk of child abuse in schools. This compliance obligation is limited to the bounds of their role≠ described in the ETR Act. The school council constituting order requires school councils to develop a student dress code.

Powers and limitations

The ETR Act provides school councils with powers to meet their objectives and functions, including entering into contracts and agreements, establishing trusts, and charging fees to parents for some goods, services and resources provided by the school.

School councils can grant licences for the use of school land and buildings. They can also employ sessional teachers and ancillary staff, such as administrative, cleaning and maintenance staff.

School councils are not authorised to purchase or acquire any land or building, or to employ teachers on contracts of greater than 12 months. Unless authorised, they do not have the power to:

- license or grant any interest in land, including school lands or buildings

- enter into hire purchase agreements

- obtain loan or credit facilities

- form or become a member of a corporation

- provide anything outside of Victoria unless it is related to a student excursion or staff professional development

- purchase a vehicle, boat or plane.

School council authority to delegate

The Regulations prohibit a school council from delegating any of its functions or powers in relation to the approval of the school budget and annual report. However, school councils can delegate any of their other functions, including approval of payments, signing of contracts, and establishment of the school's broad direction and vision. This delegation power also applies to school councils' compliance responsibilities, including ensuring that the school complies with Ministerial Order No. 870.

The Regulations require school councils to have written approval from the minister if they delegate any of their powers or duties to any person other than their school principal. Where a school council makes such a delegation, the Regulations stipulate how it must be recorded.

Victorian Registration and Qualifications Authority

VRQA is a statutory authority with responsibility for monitoring compliance with the minimum standards for the registration of primary and secondary schools, as set out in the ETR Act. It has issued a document entitled Guidelines to the Minimum Standards and Other Requirements for Registration of Schools Including Those Offering Senior Secondary Courses, which details the requirements for a school to become registered and maintain its registration.

To assure itself that schools comply with the minimum standards, VRQA can conduct its own reviews or appoint a reviewer. VRQA has approved DET as a review body for all government schools. These schools are an operational arm of DET and DET applies to VRQA for school registrations. VRQA relies on an annual compliance report from DET to provide assurance that Victoria's government schools comply with the minimum standards.

VRQA and DET have a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that sets out these assurance arrangements, outlined in Figure 1E.

Figure 1E

MOU between VRQA and DET

|

DET has an agreed responsibility to review school compliance and report on its findings to VRQA. VRQA relies on DET to oversee schools, including their principals and school councils. It expects DET to:

DET has agreed to provide VRQA with:

Under this agreement, DET is also required to address school compliance issues. VRQA expects DET to:

|

Source: VAGO .

1.5 Past inquiries and reviews

Since the ETR Act was introduced in 2006, government reviews—see Appendix C—have consistently revealed a need to improve school council members' capacity and understanding of their roles. Specifically, these reviews have highlighted the need to:

- clarify the role of school councils and principals

- provide clear governance principles and standards

- provide better support for school councils and individual school council members

- clarify school councils' oversight role in monitoring performance and compliance

- provide school councils with an opportunity to contribute to curriculum objectives

- require school councils to have a stronger focus on strategic planning and aligning budgets to strategic directions.

In 2016, the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission (IBAC) exposed limitations in the existing school governance arrangements. IBAC's Operation Ord investigation found significant weaknesses in DET's systems, controls and culture, including that members of school councils may have unwittingly facilitated the misapplication of DET funds.

Following the conclusion of Operation Ord, DET introduced a program of integrity reforms which aim to address the systemic issues that enabled previous governance failures. The reforms include training and support for principals and school councils.

Two of our past performance audits also examined the role of school councils— Figure 1F outlines key findings from these audits.

Figure 1F

Previous VAGO audits that discuss the role of school councils

|

Date |

Performance audit |

Key finding |

|---|---|---|

|

2017 |

Managing School Infrastructure |

We found that the roles and responsibilities of school councils and principals in relation to school infrastructure were unclear. We highlighted that DET lacked oversight of school councils and how they hold their principals (as their executive officers) to account for managing assets they are responsible for. |

|

2017 |

Follow-up Audit—Additional School Costs for Families |

We found that DET had responded to the recommendations from our 2015 performance audit Additional School Costs for Families. We found that DET had:

|

Source: VAGO .

1.6 Why this audit is important

School councils play a role in the governance framework of Victorian government schools. They share responsibilities for significant public funds and assets and have an influence over of school communities' confidence in how schools are managed. However, past reviews and inquiries have consistently identified weak governance arrangements for Victorian government schools.

As DET has recently invested considerable effort in strengthening school councils' understanding of their responsibilities, it is timely to review the functioning of school councils.

1.7 What this audit examined and how

Our objective for this audit was to determine whether Victorian government school councils are meeting their objectives under the ETR Act.

To address this, we examined whether:

- roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of school councils are specific, transparent and understood by stakeholders

- school councils and their subcommittees operate in accordance with their constituting order and standing orders

- DET effectively oversees school governance, including school councils.

We considered school councils of Victorian government schools, including primary and secondary schools. We did not consider Catholic and other independent schools, pre‑primary, tertiary or specialist schools.

While VRQA was within the scope of the audit, its reliance on DET led us to focus on DET's activities in ensuring compliance with school registration requirements and processes.

We did not consider the responsibilities of school councils relating to preschool programs.

In addition to our usual audit methodology, we conducted a survey of school principals and council presidents and held forums across the state for school council members to share their experiences and views on school council governance, functions, and financial and operational activities and support. Appendix D provides further detail about the survey and forums.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $680 000.

1.8 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines DET's guidance, support and oversight

- Part 3 examines the establishment, obligations and accountability of school councils.

2 DET guidance, support and oversight

School councils are authorised to do all within their statutory powers to meet their objectives and perform their functions. It is important that school councils use their considerable powers responsibly and, to do this, they need to understand their governance responsibilities.

As required by the PA Act, DET provides guidance, training and advice directly to school council members to assist them to understand their responsibilities. This support also helps school council members to develop the skills and knowledge they need to perform their duties.

Under the ETR Act, the minister holds school councils accountable for making decisions and taking actions that meet their legislative objectives. To enable this, DET must inform the minister about the performance of school councils. Further, DET has legislated power to review school councils.

In this part of the report, we assessed whether DET is effectively disseminating guidance to school councils and reinforcing this through training and other support. We also assessed the extent to which DET has processes to oversee the performance and compliance of school councils, and effectively provides advice to the minister.

2.1 Conclusion

DET has increased its guidance to school council members, yet further improvements are required to provide timely and easily accessible information to them on their role, responsibilities and accountabilities. The accessibility of information is critical to reduce the need for school councils to rely solely on principals for information and support.

DET has improved its oversight of the financial activities of school councils through a risk-based assurance program. But because DET has not applied this risk-based approach to school councils' non-financial activities, DET cannot assure the minister that school councils are meeting their objectives. DET is not well positioned to identify emerging risks or to advise the minister of any performance issues relating to the non-financial activities of school councils.

2.2 Guidance and training

Guidance and training for school councils

DET has increased its guidance to school councils. In 2012, DET's predecessor department established the School Operations and Governance Unit. This unit is located within DET's Regional Services Group. It is responsible for developing and implementing operational policy and procedures for schools and school councils, and providing advice and support to both internal and external stakeholders on school governance and operational matters—this includes to school councils. It is also responsible for managing training for school councils.

Improving School Governance guide

In 2015, DET developed its ISG guide—the main source of advice and guidance to school councils on their roles and responsibilities. DET issued the most recent revision in February 2018, and provides hard copies to those attending training. The guidance is subject to ongoing review.

The ISG guide comprises five modules:

- governance

- finance

- strategic planning

- policy and review

- school council president.

School Policy and Advisory Guide

DET provides guidance to schools on their policy and procedure requirements in its SPAG. Its purpose is to ensure schools have quick and easy access to important governance and operational policies and procedures that they must follow, and to support them to comply with school registration requirements. DET uses the SPAG as a tool to assure VRQA that schools comply with minimum standards for registration.

While the SPAG is targeted to schools, it contains information and guidance relevant to school councils.

During our audit, DET established a School Policy Template Portal to provide schools with relevant templates for documents they must complete.

Guidance and training for schools

DET provides guidance on its website and tools to help schools run and manage their responsibilities. This content is targeted at schools and includes information relevant to school councils. DET's website explains that these materials complement the SPAG.

DET has improved its guidance on school finance responsibilities. In 2017, DET updated its Finance Manual for Victorian Government Schools. This manual explains the mandatory requirements for school councils in relation to their financial responsibilities.

DET has also improved its training for principals and business managers based on this manual, through its Finance Matters training program. DET is also developing a capability framework for school business managers to enable them to provide effective financial support to the school.

Accessibility of guidance

DET provides guidance relevant to school councils through a number of channels and formats, including:

- public website—SPAG policies, guidance material and templates, ISG modules, other governance and human resources material

- intranet—contracts, infrastructure and school cleaning

- face-to-face training—based on online ISG modules

- email communication—newsletters, notifications to schools and formal communications to school councils.

However, guidance, or a complete set of links to the guidance, is not located in one central, accessible location for all school council members.

Public website

DET's guidance to school councils is hard to find on its public website.

Figure 2A highlights that pages relevant to school councils are located in multiple sections within DET's website. It also highlights that school council information is found on pages intended for teachers and school principals.

On DET's public website, it has a webpage titled 'School councils', however it is located within a section on teachers. It does not provide links to all the information DET provides to assist school council members in their role. As such, information for school councils is dispersed and hard to find.

Figure 2A

The structure of DET's website, as at July 2017

Key: ■ Webpages relevant to school councils.

Source: VAGO based on DET's website.

DET's public webpages do not provide links to all ministerial orders that school councils must comply with. These include:

- the constituting order of each school council

- ministerial orders that provide directions specifically to school councils—we identified 18 ministerial orders that directly allocate responsibilities to school councils (see Appendix B), but we could only locate five of these on DET's public website

- ministerial orders that provide directions to the school in general—school councils are required to ensure that their school is compliant with these orders within the limits of their functions.

DET stores ministerial orders on an internal system called eduPass that is only accessible to central office staff. School councils and principals do not have access to this internal system. However, school councils can request copies of ministerial orders from DET.

The result is that school council members—including principals—cannot easily and adequately inform themselves about their obligations and locate the information they need to make decisions. It also places an additional expectation on their principal, as the DET representative, to be a primary source of advice and guidance.

DET has acknowledged the efficiencies to be gained by making the ministerial orders available publicly.

Intranet

DET's intranet is only accessible to the school council president, the principal and DET employee members through their eduMail accounts. This results in an imbalance in the information available to each school council member.

Even where school council members can access the intranet, it is difficult to navigate. Information on the intranet that is relevant to school councils includes:

- legal agreements and templates for contract management

- DET's school cleaning contract policy, guide and panel search tool

- information on training for DET's bricks-and-mortar asset management program

- templates that schools are required to use for strategic planning (school review self-evaluation, school strategic plan, annual implementation plan, annual report to the school community)

- templates for policies required by the minimum standards for school registration (student engagement and inclusion, visitors and emergency management planning).

Face-to-face training

DET started its training program targeted at school councils in term three of 2015, with the objective of supporting school council members to confidently and effectively fulfil their role. DET outsources this training to external providers. Training modules are based on the ISG guide and include governance, finance, strategic planning, and the role of the school council president. DET is currently developing a training module on policy and review.

However, DET has not developed an implementation plan to ensure training is achieving its intended objectives and sufficiently reaching its audience. DET is yet to identify:

- the participants it seeks to attract to training (such as new school council members)

- the coverage of training it aims to provide across the state

- the optimum number of council members and category of members participating per session and per council to maximise learning outcomes

- an approach for increasing new school council members' awareness that training is available.

DET has two separate webpages relating to school council training. The page with information for school councils describes:

- availability of training—statewide face-to-face or online modules

- cost—training is provided at no cost to schools

- attendance expectations—training is voluntary, not compulsory.

This page also provides links to the two training providers that DET uses—however, only one of these providers gives information on the dates, times, duration and location of training events.

DET's other webpage dedicated to ISG training only provides an email address for school council members interested in finding out more. It does not link to the information DET provides.

Attendance

Since the training started in term three of 2015, DET has offered individual training sessions for four of the five governance modules—see Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Training sessions for school council members, 2015 to 2017

|

Training module(a) |

Sessions provided |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

2015(b) |

2016 |

2017 |

|

|

Governance |

87 |

131 |

98 |

|

Finance |

59 |

62 |

102 |

|

Strategic planning |

37 |

44 |

58 |

|

School council president |

13 |

60 |

21 |

|

Total |

196 |

297 |

279 |

(a) DET is currently developing training for the fifth module, policy and review.

(b) 2015 training was only provided in term three.

Source: VAGO based on DET's training attendance data.

Figure 2C shows the rates of attendance for training modules between 2015 and 2017. The governance module has attracted the best attendance rates but, even at their highest in 2016, attendance was still low compared to the number of school council members involved.

Figure 2C

Attendees at school council training sessions, 2015 to 2017

|

Training module |

2015 |

2016 |

2017 |

Total attendees |

Attendees as a percentage of all school council members |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Attendees |

Attendees |

Attendees |

% total |

||||||

|

Governance |

1 093 |

1 892 |

1 350 |

7.67 |

4 335 |

24.63 |

|||

|

Finance |

648 |

623 |

1 053 |

5.98 |

2 324 |

13.20 |

|||

|

Strategic planning |

338 |

437 |

575 |

3.27 |

1 350 |

7.67 |

|||

|

School council president |

68 |

394 |

110 |

0.63 |

572 |

3.25 |

|||

Note: DET's register shows that in 2017, there were 17 600 school council membership positions filled. All percentage calculations were based on this membership.

Source: VAGO based on DET's training attendance data.

The data that DET has collected to date does not allow it to identify which school councils have members attending training sessions or the membership categories of these attendees. This limits DET's ability to identify the coverage of school council training across the state and prioritise the location of its future training sessions.

Until 2017, DET only collected information on:

- the location of training sessions

- the total number of schools represented

- the total number of attendees.

Since term two of 2018, DET has collected additional information on whether attendees have attended training before, the position they hold on school council, their membership category and their view on the effectiveness of the training. This will enable DET to better target training and increase confidence that the capability of Victoria's school councils is improving.

In response to our survey, many school principals and council presidents responded that they valued the training. They indicated that their members should be taking up the training opportunity—particularly when first joining their school council. However, a common theme in the responses was that attending face-to-face training could be onerous for volunteers. Respondents highlighted the need to improve the clarity of the training material and consider online alternatives to the face-to-face training format.

In our forums, we heard that there are barriers to school council members accessing the training sessions for all modules. These barriers were echoed in our survey results—council members in regional areas described the need to travel considerable distances to attend training, while others discussed the challenge of juggling commitments with young families or trying to arrange childcare to attend evening sessions.

Assessment and evaluation

DET's training does not include any assessment component to test whether attendees have understood the role of the school council and its responsibilities. DET relies on self-attestation to know whether school council members have improved their understanding of the role.

DET conducts evaluations at the completion of each training session and, through this process, has received positive feedback from attendees. Attendees report that the training improved their understanding of:

- the governing role of the school council, including their role as members

- the differences between governance and operational responsibilities

- council procedures.

While DET has a clear objective for its training of school council members, it does not have an implementation or evaluation plan to ensure the training is achieving this objective.

2.3 Support

DET provides support to school councils on administration, governance and legal matters, and keeps school councils informed through direct communications.

Assistance with administration and governance

DET could do more to improve school council members' awareness of the support it offers on administration and governance.

DET's ISG guide explains the role of DET's regional offices in providing advice and support services to the school as a whole. Their services cover a wide range of topics including school management, workforce planning, leadership, youth pathways and student wellbeing. However, these topics are not relevant to school councils as they do not relate to school council functions.

DET's ISG guide does not explain the nature of the support services DET offers to school councils through two full-time staff in its School Operations and Governance Unit. This unit provides dedicated support to the 1 534 school councils about their public administration duties and governance. DET updated its ISG guide during our audit to provide an email address for the unit and to explain that it can offer advice on the roles and responsibilities of school councils. However, this update did not explain the unit's role or how it relates to DET's regional offices.

During our audit, DET described how it explains to schools and school councils the assistance the School Operations and Governance Unit provides—it communicates through school updates and newsletters, at regional forums and at various presentations. However, the forums are primarily attended by principals and DET staff, and updates and newsletters are not accessible to all school council members. Direct access is limited to principals, school council presidents and DET employees who have an eduMail account.

During our school council forums, we found that school councils had a low awareness of DET's School Operations and Governance Unit and the dedicated assistance it offers to them.

As DET does not record the support requests it receives through the regional offices or through the School Operations and Governance Unit, it does not have data on the type or frequency of information that school councils request. Therefore, DET is not able to identify common themes or opportunities to improve its guidance to meet the needs of school councils.

DET's School Operations and Governance Unit advised us that most of the issues it dealt with related to:

- a breakdown in the relationship between the principal and school council members

- lack of understanding of the respective roles of the school council and principal

- behaviour of school council members that are difficult to manage

- school councils not being provided with adequate and appropriate information to fulfil their role

- individual members who had joined the school council to focus on a single issue of interest to them.

In our survey, we asked respondents to reflect on positive aspects of the support provided to school councils and any barriers to this. In the responses, 250 principals and school council presidents commented on the way DET provides support:

- 107 respondents (43 per cent) told us that DET needed to do more regarding communication.

- 50 respondents (20 per cent) told us that DET should improve its handling of complaints.

- Only 30 respondents (12 per cent) reported that DET's support was helpful.

Legal advice

During the audit, DET told us that general legal advice is available on its intranet—but this advice is only accessible to the principal, school council president and DET employee members of the school council. DET also advised that it supports school councils with legal and quasi-legal advice through its principals.

Challenges arise when school councils need advice about their relationship with their principal or executive officer. DET is not able to provide an effective alternative advice service directly to school councils for these circumstances because it has not yet resolved the ambiguity in the relationship between the school council and the principal.

DET communication to school councils

DET relies on principals to distribute relevant information to school council members in a timely and appropriate way.

DET communicates to schools through newsletters to inform them of changes to legislation, new procedures or requirements, training and general information. DET uses the principal's eduMail accounts to email newsletters and formal communications specifically for school councils. It also uses the school council president's eduMail account for other matters relevant to school councils.