Systems and Support for Principal Performance

Snapshot

Does the Department of Education and Training support and manage principals’ development and performance to optimise student outcomes?

Why this audit is important

The principal is the critical leader within a school community and directly influences its culture and learning environment. Principals are also accountable for their school’s performance and progress towards the Victorian Government’s Education State targets.

Who we examined

The Department of Education and Training (DET), which manages the performance and development (PD) process for principals.

What we examined

- How DET implements the principal PD model (the PD model).

- DET’s expectations of principal performance and how it assesses it.

- DET’s understanding of principal performance and principals’ learning and development needs.

What we concluded

While some principals experience a constructive PD process, DET does not consistently implement its PD model to support and manage all principals' development and performance to optimise student outcomes. DET also does not systematically monitor principals' participation in the PD cycle. This means principals do not have equivalent performance expectations and assessment across Victoria.

DET also does not analyse PD outcomes to understand principals' performance or use information from the PD cycle to identify their professional learning and development needs at a region or statewide level, although it has a better understanding at a local level. This limits its ability to target support to identified performance issues and learning and development needs.

DET's PD model is intended to be based on a whole-of-practice approach; however, in practice it focuses more on leading teaching and learning, and less on managing resources and leading the school community. As a result, not all principals' performance expectations and assessments are a balanced reflection of these key aspects of their role.

This also means their development may not focus on all the skills they need to perform their role effectively.

What we recommended

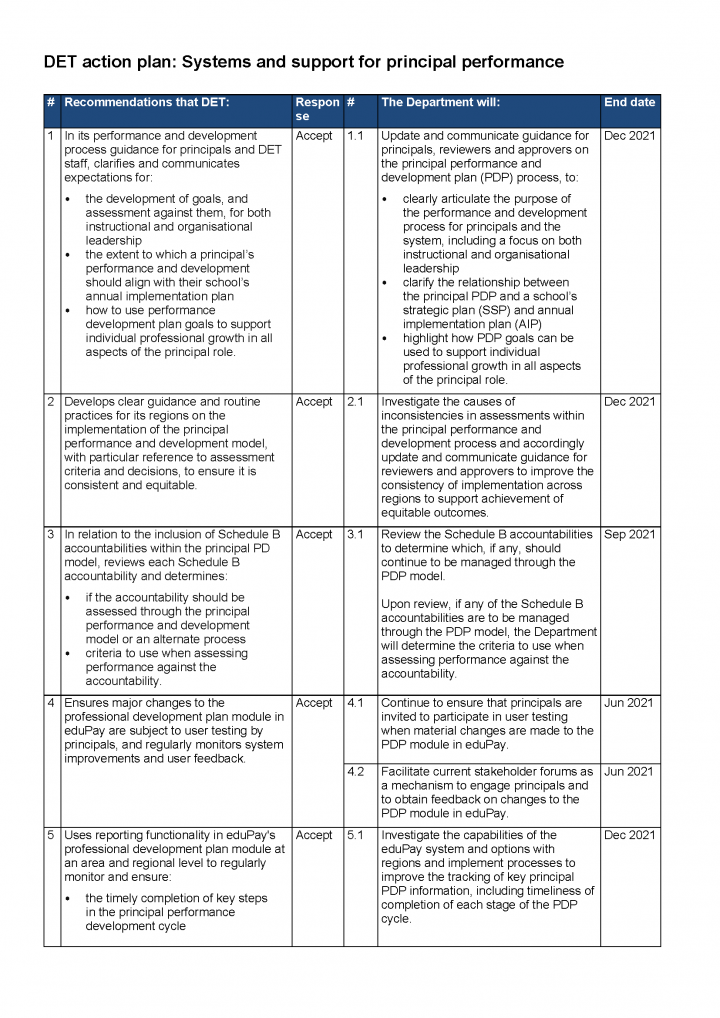

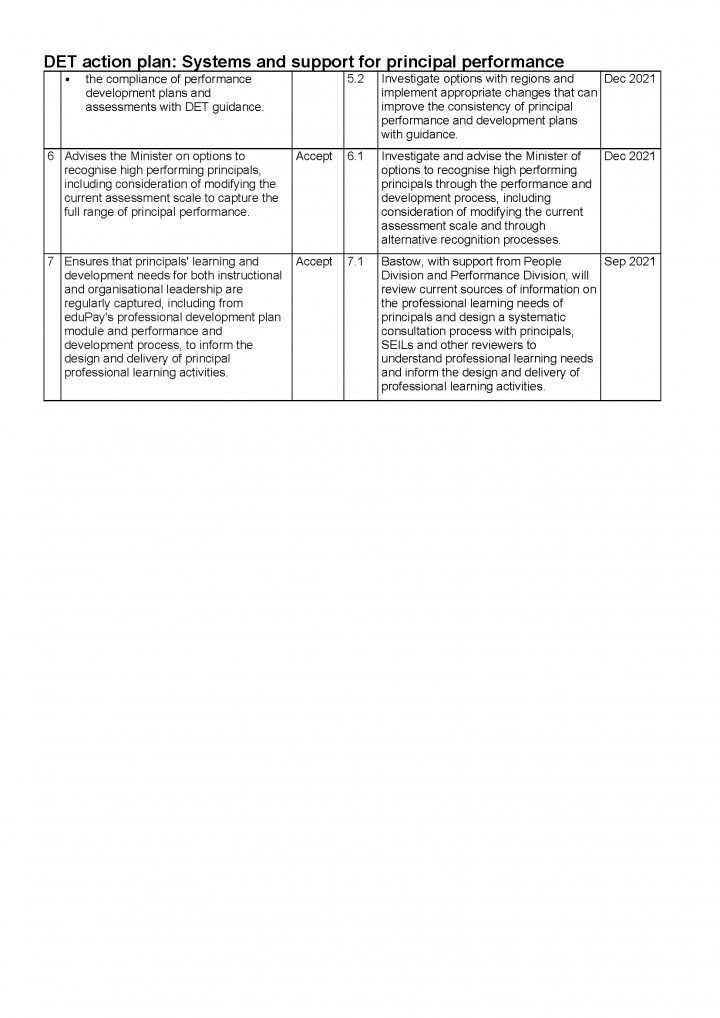

In our report, we made seven recommendations to DET. Three recommendations relate to the principal PD model, and four relate to principal performance and learning and development needs. These will ensure principals have consistent performance expectations and assessment, and improve DET’s understanding of principal’s learning and development needs. DET accepted all recommendations.

Video presentation

Key facts

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited agency and considered its views when reaching our conclusions. The agency’s full response is in Appendix A.

Implementation of the principal performance and development model

The Department of Education supports principals to develop their instructional leadership but support for organisational leadership is inconsistent

A principal’s role is to support student outcomes by leading effective teaching and learning (instructional leadership) and managing the resources that support teachers and students (organisational leadership).

The Department of Education’s (DET) performance and development (PD) model aims to develop principals in all aspects of their role but it does not implement this consistently. DET gives different PD guidance material to principals than it does to its senior education improvement leaders (SEIL), who review principal performance. Guidance to principals emphasises instructional and organisational leadership, whereas guidance to SEILs, while noting each domain of principal practice, only provides explicit guidance and examples for instructional leadership.

Consequently, while principals generally align their PD goals across all aspects of their role, some SEILs require principals’ PD goals to only reflect their school’s goals and targets, therefore excluding goals reflecting the principals’ organisational leadership development. This means that DET’s principal PD model is not as effective as it could be in assessing performance and developing principals’ professional growth and career development in all aspects of their role.

DET cannot assure that PD practices are equivalent across its regions

It is important that DET assesses principals consistently to ensure that PD outcomes in each area and region are equivalent. However, DET has not set clear assessment criteria or documented the moderation process, and it does not routinely monitor how SEILs implement the PD model and assess professional development plans (PDP). Consequently, there is variation in goal setting, assessment and moderation practices across the state. This variation means that a principal's experience of the PDP process can be strongly influenced by their particular SEIL. As DET does not ensure that PD practices are implemented consistently across its regions, it cannot assure itself that principals experience an equivalent process.

Schedule B is a section in the standard principal employment contract that outlines principals’ contractual accountabilities. It includes leading teaching and learning, school planning and governance, and financial and human resources management.

It is not clear if PDPs should include Schedule B accountabilities

DET's PD guidance states that its model focuses on principals’ development and assessment of PDP goals rather than their contractual Schedule B accountabilities. However, DET includes these accountabilities in its PD process without guidance on how to measure or assess them. This leads to varying practices among SEILs and an inconsistent assessment experience for principals across the state.

DET's lack of guidance and inconsistent practices in assessing Schedule B accountabilities contributes to principals being uncertain about their performance expectations and assessment criteria.

Recommendations about the PD model

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education and Training | 1. in its performance and development process guidance for principals and Department of Education and Training staff, clarify and communicate expectations for:

|

Accepted |

| 2. develops clear guidance and routine practices for its regions on the implementation of the principal performance and development model, with particular reference to assessment criteria and decisions, to ensure it is consistent and equitable (see Section 3.1) | Accepted | |

3. in relation to the inclusion of Schedule B accountabilities within the principal PD model, reviews each Schedule B accountability and determine:

|

Accepted |

Understanding principals’ performance and their learning and development needs

DET has a limited understanding of principal performance across the state

DET does not systematically monitor implementation of the PD model for timeliness and completion. In the 2019 cycle, most principal PDPs did not meet deadlines for milestones such as goal-setting, mid-cycle and end-cycle reviews. This means that goals and feedback are not timely, which limits the effectiveness of the PD process.

eduPay is DET’s online tool for human resources management. The PDP module within eduPay manages PDPs and the performance review cycle. All of DET’s staff, including principals and teachers, use eduPay.

Information is available to DET about the range of principal performance through the PDP module in eduPay and the local knowledge of SEILs and executive staff at area and regional levels. However, DET does not use this information to analyse principal performance across the state: for example, to identify whether particular issues exist across regions or principal types, or if systemic issues exist. Doing so could help inform DET's approach to principal professional development.

Principals' individual PDP goals are assessed according to a three-point scale of 'meets requirements', 'partially meets requirements' and 'does not meet requirements'.

Use of the three-point scale for PDP goals varied markedly between SEILs, despite each having a similar principal cohort to assess. Many SEILS do not use the 'partially meets' rating and therefore some principals are less likely to receive specific feedback on their performance and development against individual goals. This practice also indicates that principals' assessment experience is significantly dependent on the approach of their SEIL.

DET can do more to respond to principals’ learning and development needs

DET’s professional development support focuses on principals’ instructional leadership skills. There is evidence that informal processes at area and regional level mean that DET is able to identify and respond to some learning needs highlighted through the PD process. DET also encourages principals to continue their professional reading and undertake external learning where relevant. We found that principals do this.

While DET gathers and has access to information relating to the learning and development needs of principals, it does not combine and analyse this information at a system level. Further, DET's focus on professional development in instructional leadership means that principals are not always given the opportunity to develop their organisational leadership skills.

The 2019 PDP module within eduPay delivered a poor user experience

Principals told us that the user experience for eduPay's PDP module was ‘cumbersome’ and time consuming in 2019. DET responded to this feedback and has made changes to the module for the 2020 PD cycle. These are likely to lead to improved user experience in the 2020 cycle.

Recommendations about principal performance and learning and development needs

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education and Training | 4. ensures major changes to the professional development plan module in eduPay are subject to user testing by principals, and regularly monitors system improvements and user feedback (see Section 2.7) | Accepted |

5. uses reporting functionality in eduPay's professional development plan module at an area and regional level to regularly monitor and ensure:

|

Accepted | |

| 6. advises the Minister on options to recognise high-performing principals, including consideration of modifying the current assessment scale to capture the full range of principal performance (see Section 3.1) | Accepted | |

| 7. ensures that principals' learning and development needs for both instructional and organisational leadership are regularly captured, including from eduPay's professional development plan module and performance and development process, to inform the design and delivery of principal professional learning activities (see Section 3.2). | Accepted |

1. Audit context

The principal is the critical leader within a school community and directly influences its culture and learning environment. Principals are also accountable for their school’s performance and progress towards the Victorian Government’s Education State targets.

DET manages the principal PD process. It aims to develop principals’ capabilities in all aspects of their role and promote consistency in support and performance assessment across the state.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 The principal’s role

DET's Performance and Development Guidelines for Principal Class Employees describes a principal's role as providing effective instructional and organisational leadership to:

- promote effective teaching practices

- ensure that students are supported to do well

- ensure that the school community is working together.

Instructional leadership

Instructional leadership involves understanding which teaching strategies have the most impact on students in a school. Principals use this knowledge to support their staff to apply these strategies and provide an environment where students are engaged in learning.

When principals are effective instructional leaders, they:

- lead the implementation and improvement of highly effective teaching models

- participate in teachers’ learning and development

- plan and evaluate the curriculum

- establish clear goals and expectations

- support students’ engagement, wellbeing and achievement.

Organisational leadership

Organisational leadership involves managing all of a school’s available resources to sustain effective teaching, learning and engagement. Principals use the skills and knowledge of all school staff to build a positive and safe learning environment. They also manage financial and non-financial resources provided by DET and the school community to ensure that school buildings and programs support effective teaching and learning.

When principals are effective organisational leaders, they:

- secure and allocate resources that are aligned with the school’s teaching and learning goals

- create and maintain a respectful school environment that manages conflict and enables learning

- create connections within the school community so staff, students, parents and carers can work together to improve student outcomes

- build networks beyond the school community and contribute to the education system.

Professional leadership

DET recognises that principals can positively impact students’ engagement, wellbeing and achievement through ‘professional leadership’. This is one of the four statewide priorities in DET’s Framework for Improving Student Outcomes (FISO), which we discuss in Section 1.2.

As Figure 1A shows, effective professional leadership, which can be exercised by principals and other school leaders, has four dimensions each including instructional and organisational leadership.

1.2 Requirements of the principal role

Principals are employed by DET and are responsible for implementing DET’s policies. DET expects principals to lead improvements in student outcomes, teaching quality and their school’s overall performance. Principals work autonomously and are supported by SEILs.

Principals are accountable to their school council and DET for their school’s performance and progress towards the Victorian Government’s Education State targets. DET expects principals to align human, financial and intellectual resources within their school to achieve the school’s goals and priorities.

School councils play a role in appointing principals but are not involved in the annual principal PD cycle. DET is responsible for establishing and maintaining performance expectations and conducting assessments.

Principals’ contract of employment

The Education and Training Reform Act 2006 is the legislative foundation that DET uses to employ principals.

DET employs principals through a contract of employment that lasts for up to five years. This contract requires principals to:

‘lead and manage the planning, delivery, evaluation and improvement of the education of all students in a community through the strategic deployment of resources provided by the Department [DET] and the school community.’

Schedule B in the principal contract of employment describes the duties and core accountabilities of the role across 10 areas. Principals must perform these duties in line with statewide guidelines and government policies.

The contract also requires principals to participate in a performance review process relating to the 10 core accountabilities.

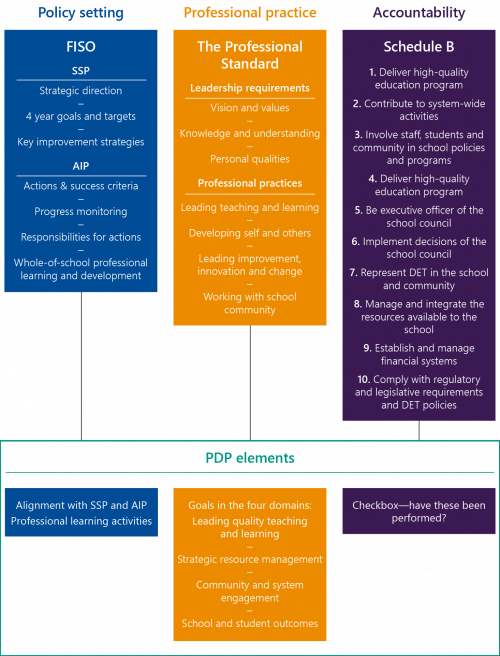

Figure 1B shows the core accountabilities described in Schedule B aligned to instructional and organisational leadership requirements.

FIGURE 1B: 10 core accountabilities described in Schedule B sorted by leadership type

| Instructional leadership | Organisational leadership |

|---|---|

| Ensure the delivery of a comprehensive, high quality education program to all students | Be executive officer of the school council |

| Contribute to system-wide activities, including policy and strategic planning and development | Implement decisions of the school council |

| Appropriately involve staff, students and the community in the development, implementation and review of school policies, programs and operations | Establish and manage financial systems in accordance with DET and school council requirements |

| Report to DET, the school community, parents and students on the achievements of the school and of individual students as appropriate | Represent DET in the school and the local community |

| Effectively manage and integrate the resources available to the school | |

| Comply with regulatory and legislative requirements and DET policies and procedures |

Source: DET.

The Framework for Improving Student Outcomes

The Framework for Improving Student Outcomes model (FISO model) is DET’s policy for leading and delivering school education in Victoria. It provides the context for DET’s principal performance expectations and shapes the content of principals’ PDPs.

DET expects principals to implement school improvement strategies consistently with the FISO model. The FISO model is made up of four statewide priorities that are enacted through 16 dimensions of school practice. The four statewide priorities are:

-

excellence in teaching and learning

SSPs describe schools’ high level goals and targets over four years. Key improvement strategies set out how schools will achieve these goals.

AIPs outline the actions that schools will take that year to achieve the goals and targets in their SSP.

- community engagement in learning

- positive climate for learning

- professional leadership.

Schools use the FISO model to develop their school strategic plan (SSP) and annual implementation plan (AIP).

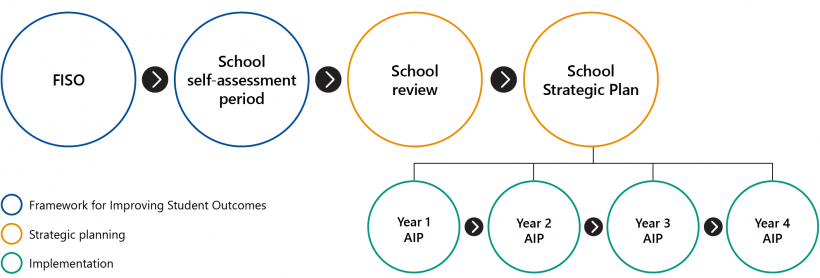

Each school undergoes a four-year review and planning cycle. In each review year, the principal leads their school through a self-assessment against the FISO Continua of Practice for School Improvement, which is a tool that assists principals and teachers to review and refine what works in their school. An independent review team authorised by DET works with each principal to evaluate their school’s performance against the goals and targets in their current SSP.

During this review process, schools create a new SSP for the next cycle, which enables them to develop their next AIP. Figure 1C shows the review and planning cycle.

FIGURE 1C: School review and planning cycle

Source: VAGO, from DET information.

DET expects the goals, strategies and targets in SSPs and AIPs to inform the work and professional learning of each staff member at a school.

1.3 DET’s approach to principal PD

In 2015, DET introduced the PD model, which aligns principals’ performance with their school’s strategic priorities for overall improvement and student learning outcomes.

The PD model requires principals to set goals across the following three domains of principal practice:

- leadership of quality teaching practices and lifelong learning

- strategic resource management

- system and community engagement.

Principals set an additional goal against 'school and student outcomes'.

The PD model also includes assessment of Schedule B core accountabilities.

DET adopts a whole-of-practice approach to its PD model. It recognises that the totality of principals’ work and leadership within their school context contributes to improvements in student engagement, wellbeing and achievement.

Strategic and annual planning

DET expects principals’ PDPs to be informed by their school’s AIP goals, key improvement strategies and targets. This alignment happens when a principal’s PDP goals, strategies and targets are taken directly from their school’s AIP or clearly support the work described in the AIP.

Each AIP includes a professional learning and development plan (PLDP) that:

- identifies professional learning priorities for the school

- describes who will participate in these learning priorities, when the learning will occur and what expertise the school will access.

DET expects the contents of a school’s PLDP to flow into each staff member’s PDP, including the principal’s. DET’s intention for this is to unite school staff towards achieving the priorities in its SSP.

The Australian Professional Standard for Principals

DET’s whole-of-practice approach is based on the Australian Professional Standard for Principals (the Standard). The Standard is published by the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL).

The Standard is based on the following three leadership requirements:

- vision and values

- knowledge and understanding

- personal qualities and social and interpersonal skills.

It states that principals enact these leadership requirements through five professional practices:

- leading, teaching and learning

- developing themselves and others

- leading improvement, innovation and change

- leading the management of the school

- engaging and working with the community.

The Standard outlines leadership profiles and development pathways against each of the professional practices. While not intended for use as a performance assessment framework, principals are encouraged to use it for reflection on their professional growth and development.

DET’s PD model supports principals to incorporate these professional practices into their PDPs. It does this by aligning three goals in its PDP template with the professional practices (see Figure 1D).

FIGURE 1D: Alignment between DET's three domains of principal practice and AITSL's five professional practices

| DET domain of principal practice | DET description | AITSL professional practices |

|---|---|---|

| Leadership of quality teaching and lifelong learning | Principal-class employees are the leaders of high-quality teaching and learning in the school community. They set high expectations for everyone in the community and develop students, teachers and themselves through building a culture of lifelong learning, challenge and support. |

|

| Strategic resource management | Principals effectively optimise resources and lead innovation and change to deliver high-quality educational outcomes for all students. Principals lead evidence and data-based improvements to maximise the efficiency and effectiveness of school resources (including human, financial and physical resources) to achieve the school’s priorities. |

|

| Strengthening community and system engagement | Principals develop and maintain positive and purposeful relationships with students, parents/carers and the broader school community. This includes using multiple sources of feedback from the community to drive improvement, ensuring a culturally rich and diverse school environment and contributing to the school system through engaging and collaborating with other schools and external organisations. |

|

Source: DET’s Performance and Development Guidelines for Principal Class Employees.

Principals set their PDP goals, strategies and targets to align with their school’s SSP and AIP and the Standard’s framework. Figure 1E shows how these elements combine to make up a complete PDP.

FIGURE 1E: Elements of DET's principal PDP

Source: VAGO.

Professional learning and development

DET provides a professional learning and development framework for principals. The content of this framework focuses on implementing the FISO model. DET delivers the framework through forums and activities for principals throughout the school year and at various levels of the education system, such as:

- communities of practice meetings, which occur approximately monthly at a network level

- area principal forums, which take place in terms 1, 3 and 4 and occur at a region and area level

- the Education State School Leadership Conference, which is a system-level event that occurs annually in Term 2.

In 2019, these professional learning activities focused on:

- strengthening instructional leadership

- developing an evaluative mindset

- creating collective responsibility and collective efficacy

- embedding structures, processes and culture

- leading improvement.

Principal professional learning can also occur through professional reading, embedded learning within schools, small-group actions and formal courses. For example, DET's Bastow Institute of Education Leadership delivers a range of courses to support the development of emerging and new principals.

1.4 The principal PD cycle

Roles and responsibilities

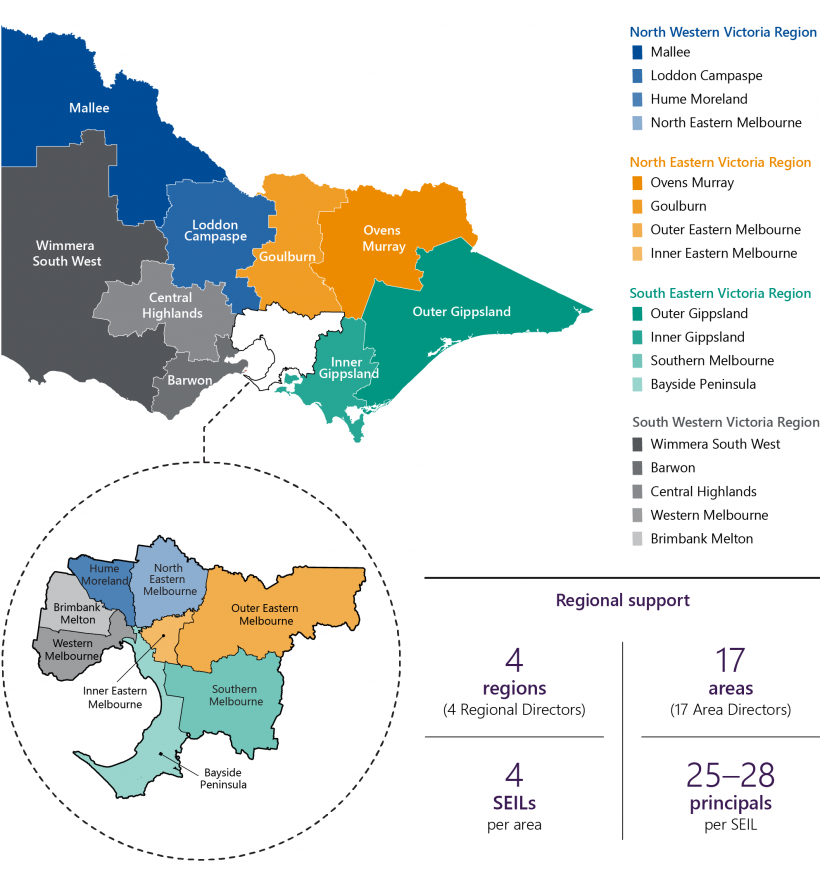

DET has a regional operations model, which means that it delivers support to schools and principals through its regions, areas and networks.

DET has four regions and each region has approximately 400 principals. A regional director manages principals in each region. Regional directors authorise SEILs to manage principals on a day-to-day basis.

Sixty-eight SEILs operate within 17 areas and each work with a network of approximately 25 to 28 principals. SEILs work closely with key executives in their area; the area executive director (ED) and the ED, school improvement.

Figure 1F shows DET's region-based support for schools and the distribution of senior staff that support the PD model.

FIGURE 1F: DET's region-based support and distribution of staff supporting the PD model

Source: VAGO, from DET information.

SEILs are authorised by regional directors to review their principals’ performance. This means that they approve PDP goals, have performance conversations with principals and recommend an outcome for each PD cycle. Regional directors are responsible for approving the outcome of each principal’s performance review.

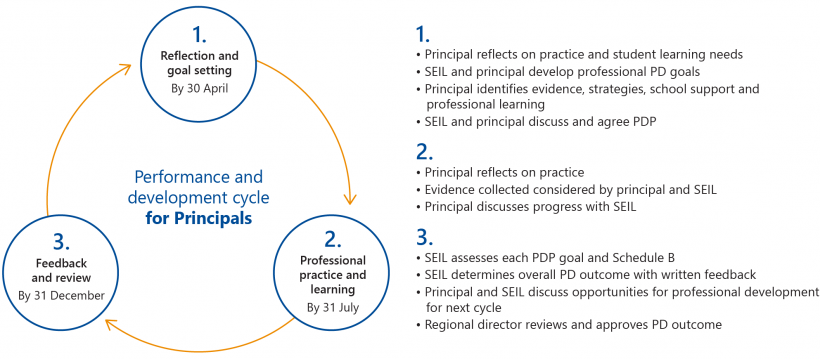

Figure 1G shows the key stages of the PDP process and who is involved in each stage.

FIGURE 1G: Key stages and roles involved in PD cycle

Source: VAGO, from DET information.

By 30 April, each principal must be advised of their final PD outcome from the previous year so that any remuneration progression can occur on 1 May. For example, principals participating in the 2019 PD cycle will know their final outcome by 30 April 2020 so that progression can occur from 1 May 2020.

Implementing the PD cycle

DET provides guidance material to help principals, SEILs and regional directors move through each stage of the PD cycle. Principals enter their PDP goals into eduPay’s PDP module, which allows SEILs and regional directors to view PDPs and provide feedback.

The purpose of eduPay is to streamline human capital management within DET. The tool can monitor timeliness, completion rates and review outcomes for PDPs. DET rolled out eduPay to all of its non-teaching staff in 2016 and to schools in 2017 and 2018.

DET set up eduPay securely to ensure that PDP content and assessment outcomes can only be seen by the principal, reviewer (SEIL) and approver (regional director). Principals can see the comments made by their SEIL and regional director and the final approved outcome of the PD cycle. SEILs can see the PDPs of each principal in their network and regional directors can see the PDPs of each principal in their region.

The ED of DET’s People Division receives annual reports of PDP outcomes. These reports contain the results of all teaching services' performance outcomes, including outcomes for principals. DET’s People Division uses this data to administer salary progression.

DET has committed to using PDP data at an ‘aggregate level and not at an individual level (that is, the data contained in an individual employee's performance and development plan will not be used beyond the school)’. This is one of DET’s commitments in the Victorian Government Schools Agreement 2017 Additional Commitments (VGSA 2017). DET interprets this to mean that any data in an individual employee’s PDP, whether teacher or principal, will not be used or referred to for purposes beyond the school. While DET staff use individual data to implement the PD model, the People Division does not undertake analysis of this data.

Guidance material for principals and reviewers

Materials for principals

DET has a suite of guidance materials for principals that describe its approach to principal PD and the PDP process. The key document is the Performance and Development Guidelines for Principal Class Employees. This document describes:

- DET’s whole-of-practice approach to principal PD

- the relationship between the FISO and principal PD

- the Standard and how it aligns with PDP goals

- the goal-setting process

- the PD cycle

- the role of professional learning

- links to other resources.

Other resources include guides about setting goals, selecting evidence to prepare for mid and end-of-cycle review conversations and how to use the PDP module in eduPay.

DET’s mid and end-of-cycle guidance to principals states that while PDPs must incorporate elements of their school’s SSP and AIP, they should also incorporate goals that are relevant to individual professional development.

Materials for SEILs

DET provides SEILs with a guidance document that describes their role in school planning. This document also defines their role and responsibilities for the principal PD cycle, including approving PDP goals and providing feedback at the mid and end points of the review cycle.

DET’s guidance for SEILs describes how it expects principals’ PDPs to align with school planning and professional learning. It notes that the Standard outlines the quality, practice and professional expectations for principals.

The eduPay PDP module

DET introduced the PDP module in eduPay to schools in 2017 to replace its existing paper-based PDP system. It finished rolling out the module in 2018. The module gives DET a greater ability to oversee principals’ compliance with PDP requirements, timeliness and completion. The 2019 PDP cycle was the module’s first full cycle of operation.

DET adopted the module to improve the efficiency of the PD process and PDP documentation. The tool holds a single up-to-date version of each principal’s PDP and has reminders and a built-in workflow for users and reviewers. It acts as a central repository for PDP goals, evidence and feedback.

DET matches outcomes data from eduPay with data on employees’ eligibility for salary progression. The results of this process flow through to DET's payroll staff to administer.

The module has specific functions and views for each participant in the PDP process. An employee, such as a principal, fills out their PDP online and attaches electronic files to show evidence of their achievements. Reviewers (SEILs) view the PDPs of their direct reports and complete review steps, such as providing feedback, online. Approvers (regional directors) can see PDPs and reviewers’ comments.

Batch approval is available to regional directors, who have large numbers of PDPs to approve. This means that they can approve multiple PDPs at once.

2. Implementation of DET’s PD model

Conclusion

DET has limited oversight of the principal PD model and there are inconsistencies in its guidance materials about it. As a result, some principals’ PDPs lack:

- focus on organisational leadership, which is fundamental to the principal role

- individual development goals because they focus more on the school’s overall goals

- consistent assessment of the Schedule B accountabilities.

Principals play an important role in improving their school’s learning outcomes, so it is vital that DET takes a more holistic and consistent approach to implementing the PD model.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Guidance on the principal PD model's purpose

DET’s principal PD process complies with legislative requirements and the approach outlined in the VGSA 2017. During the process:

|

SEILs … |

Principals … |

|

Review school data and their region’s priorities for school improvement |

Set goals with their reviewer and submit their PDP in eduPay |

|

Coordinate the PDP process by sending reminders and prompts to their principals to start the reflection and goal-setting processes. They also organise mid and end-of-cycle review conversations |

Gather evidence for mid and end of cycle review conversations |

|

Endorse PDPs and complete other review and endorsement steps in eduPay |

Participate in mid and end-of-cycle review conversations |

|

Provide feedback throughout the principal PD cycle and exercise their professional judgement while assessing PDPs |

|

However, DET does not consistently implement or provide clear guidance on some parts of the process.

DET’s guidance material for principals and SEILs about the PD model’s purpose is unclear and inconsistent. This means that principals and SEILs approach the PD cycle with different expectations.

DET’s guidance material for principals describes its whole of practice approach, the Standard’s professional practices and development pathway and how PDP goals need to align with SSPs and AIPs. It also encourages principals to set goals that are relevant to their individual development.

However, DET’s guidance material for SEILs refers only briefly to its whole-of practice approach. Instead, it emphasises that a principal’s PDP goals should closely align with their school’s SSP and AIP.

As a result, principals, SEILs and area EDs have a different understanding of the PD model’s purpose. Our interviews with 16 principals, seven SEILs and four area EDs found that in practice:

|

Principals think the PD model’s purpose is to … |

Principals think the PD model’s purpose is to … |

|

Manage Schedule B accountabilities |

Be a lever for school improvement |

|

Improve their instructional leadership |

Achieve a school’s AIP targets |

|

Reflect all aspects of their role, including organisational leadership and their individual development needs |

|

Two area EDs and four SEILs reflected that the current PDP process does not adequately capture all aspects of the principal role, including organisational leadership. This was reiterated by interviewed principals, who explained that they did not feel supported through the PDP process to develop their organisational leadership skills.

The lack of shared understanding about the purpose of principal PD has a negative impact on PD practices and outcomes. It means that principals can experience a PD cycle where their goals are largely irrelevant to their development needs or their performance assessment does not focus on all aspects of their role.

2.2 Managing Schedule B accountabilities and performance expectations

The Schedule B accountabilities are the minimum expectations of the principal role. The principal contract of employment expects principals to be ‘honest and diligent’ in performing these accountabilities. In its guidance materials for SEILs and principals, DET states that ’satisfactory performance’ of these accountabilities is necessary to determine that a principal has met their PD requirements.

DET's guidance material does not clearly explain how Schedule B accountabilities should be managed in the PD process. This can make principals feel uncertain about their performance expectations and assessment criteria for Schedule B.

DET only briefly discusses the Schedule B accountabilities in its guidance materials. It also does not provide assessment criteria, examples of relevant evidence or performance benchmarks for them. While DET’s guidance infers that principals are accountable for performing their duties and responsibilities at all times, it does not describe how to assess this.

DET’s PDP template includes a checkbox for SEILs to confirm that a principal has met all of the Schedule B accountabilities. However, interviewed SEILs agreed that they do not have clear guidance on how to assess this. Instead, SEILs said that they use their professional judgement and knowledge of each principal and their school to determine if a principal has met these accountabilities.

Role accountability involves routinely holding an employee accountable for performing the duties of their role.

The Victorian Public Sector Commission’s (VPSC) Executive Performance Management Framework (the VPSC Framework) describes role accountability as one of the ‘foundation principles’ of PD models. Better practice PD models explicitly explain this in their guidance material and state that poor performance, or an employee’s failure to perform these duties, should be addressed immediately. See Appendix E for more information on what better practice PD involves.

DET’s unclear guidance about Schedule B accountabilities limits the PD model’s effectiveness. It also means that principals across DET’s regions and the state are likely to experience inconsistent assessment practices.

2.3 Goal setting and professional development

Goal setting has two functions in a PD model. It identifies areas for professional development and describes targets and strategies to measure progress towards those goals.

In DET’s PD model, goals and targets form the basis of performance assessments. These are additional to the Schedule B accountabilities.

DET's guidance for principals states that they will use their school’s priorities, as stated in the SSP and the AIP, to reflect on their practice and inform their PDP goals. DET’s guidance states that a principal’s goals should aim to improve their school and student outcomes and reflect their development needs.

Balancing school-focused and individualised PDP goals

The process for setting principals' PDP goals is less effective in supporting personal professional growth when SEILs:

![]() There is a standardised approach to goal setting regardless of school size and 'network goals' are now becoming evident in preliminary PDP discussions for the new year.'

There is a standardised approach to goal setting regardless of school size and 'network goals' are now becoming evident in preliminary PDP discussions for the new year.'

—Survey respondent

- suggest goals and targets that are relevant to their region rather than goals that are specific to the individual school and principal

- expect very strong alignment between PDPs and AIPs

- do not approve PDP goals related to organisational leadership.

DET’s guidance to principals emphasises that the PDP is an individual document for professional development, but this does not reflect many principals’ experience. The strong focus on school improvement means that DET’s PD model is not implemented as effectively as it could be to promote principals’ individual professional growth and career development. There is therefore a risk that principals experience a depersonalised PD cycle that does not help them develop in all aspects of their role or become the education system leaders they would like to be.

For example, three interviewed principals said that their SEIL had refused organisational leadership goals because they were not directly aligned with their school’s AIP. One principal gave us an example of a goal they proposed about learning to lead change when introducing a new instructional model at their school, which their SEIL did not agree to include in their PDP.

Alignment of PDP goals with school AIPs

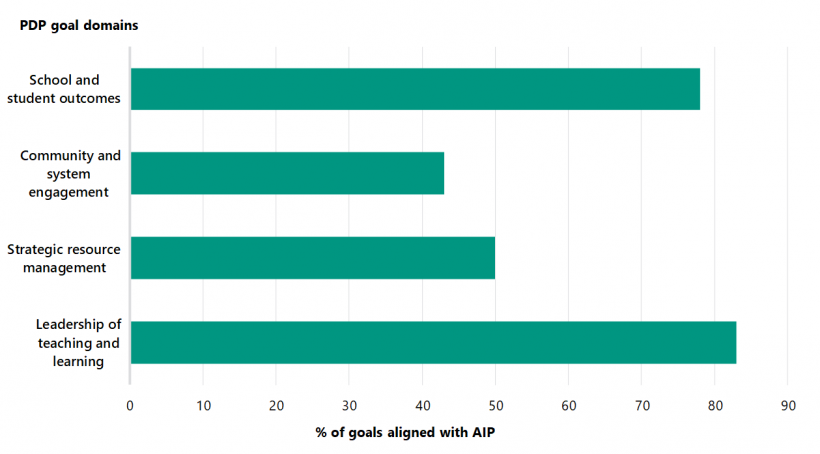

There is a strong alignment between principals’ PDP goals and their school's SSP and AIP when goals relate to instructional leadership and student achievement. There is weaker alignment for goals relating to strategic resource management and community and system engagement, which involve organisational leadership.

SEILs implement the PDP process with a focus on each school’s AIP and SSP. They do this during their goal-setting conversations with principals and by aligning school improvement meetings with performance review conversations.

Each interviewed SEIL said that they prepare for the principal goal-setting process by identifying relevant goals based on regional school improvement data and school specific student achievement data. They communicate this information to the principals they manage.

Not all SEILs see the principal PDP process as exclusively related to assessing the principal's delivery of the school's AIP. Three interviewed SEILs expressed the view that the current PDP process has room for personal professional development goals and that it is ideal for each principal’s PDP to have these.

During this audit, we surveyed 1 332 principals and received 479 responses. 96 per cent of survey respondents agreed that their PDP aligned with their school’s SSP and AIP. All interviewed principals agreed with this statement. Refer to Appendix D for further information about our survey method and the margin of error for all results.

By aligning principals’ PDPs with schools’ AIPs, SEILs focus on school improvement when assessing principal performance. Across a sample of 40 de-identified principal PDPs and their schools’ SSPs and AIPs, 60 per cent of these 40 PDPs aligned with their school’s corresponding SSP and AIP, which is in line with DET’s policy and guidance. Only six contained goals that were relevant to other aspects of the principal role, such as organisational leadership.

Figure 2A shows the percentage of goals in this sample of PDPs, grouped by goal domain, that align with the corresponding school’s AIP.

FIGURE 2A: Alignment between PDP goals and school AIPs

Source: VAGO, from DET’s 2019 eduPay dataset.

As Figure 2A shows, there is a weaker alignment between PDP goals and the school's AIP in the domains of ‛strategic resource management’ and ‛community and system engagement’. For eight PDPs, these were not aligned because the school was going through the school review process. These principals’ PDPs focused on the review process rather than the AIP or their own professional development. This approach works with the FISO model, but without clear guidance there is a risk that a principal’s PDP goals will not be balanced across all aspects of their or reflect their individual development needs.

PDPs that were less closely aligned to the school's AIP reflected a better balance of the school’s context with individual goals for professional growth from a whole of role perspective.

DET's strong focus on aligning principals' PDPs with their school's AIP means that some SEILs and principals use goal domains for organisational leadership to add student achievement goals. Within the domain of 'strategic resource management', 40 per cent of the sample PDPs had goals specific to student achievement outcomes or instructional leadership. In the domain of 'community and system engagement', 43 per cent of these PDPs described student wellbeing, instructional leadership or school review goals. When goal domains for organisational leadership are used for instructional leadership outcomes, the opportunity for principals to develop in all aspects of their role is undermined.

When principals’ have a lack of individual goals, they often see their PDP as less necessary. One in five surveyed principals stated that the alignment between AIPs and PDPs is so strong that the AIP should replace the PDP to ease the administrative burden. Four of the 16 interviewed principals also expressed this opinion.

Surveyed and interviewed principals cited several reasons why they would prefer to reduce their workload by replacing their PDP with the AIP, including:

- they have a heavy workload

- there is already a sustained focus on school improvement outside of the PDP process

- the PDP module in eduPay delivers a poor user experience

- their experience of the PD cycle varies substantially.

As expressed by these surveyed and interviewed principals, strong alignment between PDP and AIP goals means that, in practice, school improvement targets also become the principal's performance expectations.

While there should be a clear relationship between principal performance and school performance, there is a separate and specific process designed to assess school performance. The principal PD model is most effective when linked to this and it allows each principal to identify individualised goals and development actions to achieve wide school objectives.

SEILs’ recognition of school leadership work

Because DET’s current approach can overlook the organisational leadership aspects of the principal role, there is a risk that a principal’s effectiveness in, for example, financial or human resource management or leading their school community may not be recognised or further developed.

Span of control refers to the relationship between managers and the number of people they supervise. Best-practice spans of control for Australian public sector agencies range between five to 12 employees per supervisor.

Feedback from surveyed and interviewed principals indicated that while their instructional leadership work is visible to their SEIL, the work they do to manage their school community is not. Eighteen per cent of survey respondents commented that their SEIL does not recognise this type of leadership work. These principals attributed this to their SEIL’s heavy workload from having a large span of control, high turnover in the SEIL role or DET overemphasising school data as an indicator of performance.

Half of the interviewed principals described a PD process that overlooks their school leadership work. One interviewed principal felt that their SEIL does not see the work they do to lead their school, which has a complex context. This principal experienced a PD process that did not recognise the entirety of their role. Another principal described the PD process as overlooking the ‛everyday work‘ of school culture, community support and student and family engagement.

2.4 Assessing principal performance

DET assesses principal performance based on whether a principal has met the Schedule B accountabilities, achieved their PDP goals and provided evidence of improved practice and their impact on school and student outcomes.

Each principal agrees on their PDP goals, targets and evidence with their SEIL. DET’s Principal Evidence Guide describes the types of evidence that principals can use to support their performance and achievements, such as:

- student achievement data

- school survey data

- curriculum documentation

- other documentation relating to professional learning, school management or communication with the school community.

This list is not exhaustive; principals may choose other types of evidence if their SEIL agrees.

How SEILs assess principal performance

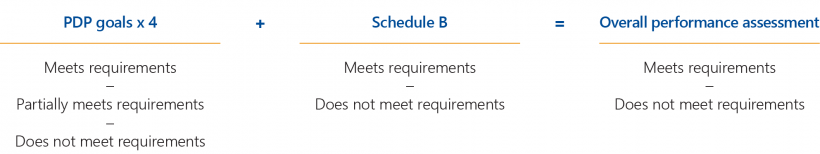

As Figure 2B shows, a SEIL gives an overall assessment of principal performance by assessing whether a principal has met their PDP goals and Schedule B accountabilities.

FIGURE 2B: Assessment criteria for principal PDPs

Source: VAGO, from DET.

DET provides definitions for a three-point scale for PDP goals. These definitions are based on if a principal meets (or partially meets or does not meet) ‛the goal set in their PDP, and therefore demonstrates the required performance and professional growth and improvement of practice at this stage of career development’. DET’s guidance uses the Standard to frame performance, growth, professional practice and career stages but does not provide advice on how SEILs should apply this in practice.

SEILs assess whether principals have honestly and diligently performed the Schedule B accountabilities. They are required to report this using a two-point scale of 'meets' or 'does not meet' requirements. In the absence of specific guidance or assessment criteria, they use their professional judgement and knowledge of each principal and school to assess if a principal meets the Schedule B accountabilities. However, this approach may be insufficient to assess performance of some accountabilities, such as financial and human resources management or school governance, as this work may not be visible to all SEILs.

Interviewed SEILs were aware of the need to ensure that principals are accountable in all aspects of their role. Some practices for assessing principal performance were consistent for all interviewed SEILs. This included tracking a principal’s progress and achievement through careful use of evidence in their PDP and making the time to visit each principal at work in their school.

DET’s guidance to SEILs and principals does not explicitly say how SEILs should assess a principal's overall performance. It is inferred, rather than stated, that a principal needs to get an assessment outcome of 'meets requirements' for the Schedule B to receive an overall performance outcome of 'meets requirements’. DET’s guidance does not state if a minimum number of PDP goals need to be assessed as 'meets requirements' and it is not clear how the 'partially meets requirements' rating contributes to a principal’s overall performance assessment.

This lack of clarity around assessment criteria means that a principal’s performance assessment relies on the goals and targets agreed in their PDP and their individual SEIL’s professional judgement.

How SEILs use the three-point scale to assess PDP goals

![]() The meet/does not meet option has meant that if you do not meet the target 100% when you have set stretch goals for yourself and your school, you run the risk of being labelled as ‛not met’ even though significant growth has been made professionally and for your school.’

The meet/does not meet option has meant that if you do not meet the target 100% when you have set stretch goals for yourself and your school, you run the risk of being labelled as ‛not met’ even though significant growth has been made professionally and for your school.’

—Survey respondent

Interviewed SEILs were aware of the need for nuance when assessing principal performance. In this context, nuance can involve assessing one or two individual PDP goals as ‛partially met’ or ‛not met’, while giving an overall assessment of ‘meets expectations’. This approach is in line with DET’s policy and guidance.

Feedback from the interviews we conducted suggested that SEILs are somewhat reluctant to use the ‛partially meets expectations’ rating for PDP goals. Three SEILs said that they rarely give ‛partially meets expectations’ ratings, or only in circumstances where a PDP goal has been ‛derailed’ by factors outside of the principal’s control. As one SEIL said, ‛Principals work really hard and can see it as a real whack if you give them a partially met’. This feedback may also reflect a culture that is reluctant to address underperformance and hold difficult performance conversations.

While two interviewed principals were more accepting of this nuanced approach, others were not. Most principals experienced their PD as a binary assessment and associated a ‛partially met’ rating with negative perceptions of their work. This may inhibit their goal setting and targets so that they can be sure of a 'meets requirements' assessment.

Only one interviewed principal mentioned that their SEIL used a ‛partially met expectations’ rating for their PDP goals. This early-career principal said that they did not think the PD process would be used punitively and was ‛not afraid’ of a goal being assessed as partially met. This is because they consider their PDP goals as aspirational and that ‛what is important is the strategy and effort brought to trying to meet that goal’. We discuss how SEILs used the ‛partially meets requirements’ rating in the 2019 PD cycle in Section 3.1.

2.5 Principals’ experiences of performance assessments

Performance assessments are more effective when employees perceive them as fair, consistent, accurate and open to their input. When this happens, employees tend to accept constructive feedback and their performance is more likely to improve.

Our interviews with principals and SEILs and the results from our principal survey showed that:

- most principals put significant effort into the PD cycle

- most principals are confident that their SEIL understands their school’s context and performance data

- large spans of control and the narrow focus on school improvement increases the risk that DET will not identify principals who do not meet the organisational leadership expectations of the role

- in the absence of a documented process, area EDs informally moderate performance assessments, which leads to inconsistent practices across the state.

How principals engage with the PD cycle

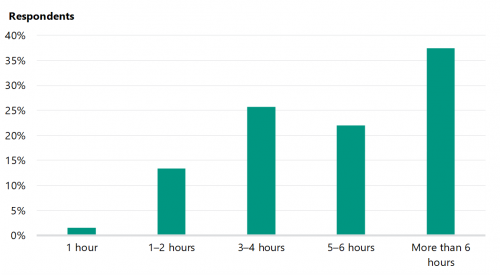

Figure 2C shows that surveyed principals most commonly spent over six hours on the 2019 PD cycle.

FIGURE 2C: Time principals spent on the 2019 PD cycle

Source: VAGO.

Our analysis of 1 425 principal PDPs from the 2019 PD cycle found that principals concisely describe their goals. The mean word count across all goals was 4.6 and the maximum word count was 14.

Closer examination of a sample of 40 PDPs confirmed this result. While the goals themselves were brief, each PDP described the strategies and evidence required to demonstrate the achievement of goals in greater detail.

Additionally, 93 per cent of principals engaged with eduPay’s PDP module in 2019 and 91 per cent recorded goals against the three domains of principal practice and school and student outcomes. Seven per cent of PDPs were recorded as blank and were not included in our analysis. We discuss these PDPs in Section 3.1.

Two per cent of PDPs recorded in the eduPay module were inactive for 2019. This was due to unintentional duplication, the principal moving to another role for the year or the principal being on leave.

SEILs’ understanding of school context

Figure 2D shows that nearly all surveyed principals think that their SEIL understands their work and their individual school’s context.

FIGURE 2D: Principal perceptions of how SEILs understand their work and context

| Strongly agree | Agree | Disagree | Strongly disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My reviewer understands my school context | 61% | 29% | 6.5% | 3.5% |

| My reviewer has a good understanding of my work as principal | 66% | 23% | 8% | 3% |

Source: VAGO.

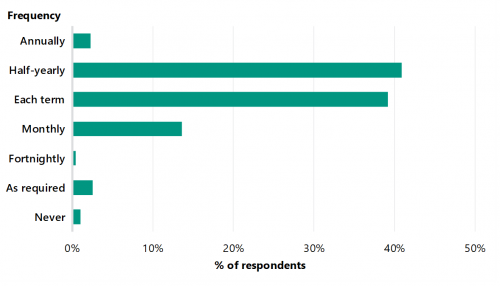

As Figure 2E shows, nearly 80 per cent of respondents see their SEIL between two to four times a year. We found no relationship between meeting frequency and a principal’s confidence that their SEIL understands their school’s context and performance data.

FIGURE 2E: Frequency of principal meetings with SEILs

Source: VAGO.

Moderation processes

It is important that PDPs are assessed consistently across the state to ensure that all principals are treated fairly. However, DET does not have a documented moderation process or guidance for SEILs to ensure that this occurs.

Interviewed area EDs and SEILs described the importance of a cohesive approach to principal performance and the informal moderation processes they use to help achieve this. These processes usually involve regular conversations between SEILs and area EDs through meetings at relevant points throughout the PD cycle. Area EDs and SEILs advised us that these moderation conversations focus on performance expectations and consistency of assessment.

Despite this, there is no evidence that moderation occurs consistently across or within DET’s areas or regions. There is also no evidence that the outcomes of moderation conversations result in consistent assessment processes across the state.

Only 35 per cent of surveyed principals felt confident or very confident that the PD process assesses their performance fairly and consistently.

2.6 Identifying and supporting underperformance

DET's guidance to SEILs states that the mid-cycle review is an opportunity to raise concerns about performance and expectations for improvement. It also states that such concerns should be raised as soon as they are identified. DET’s guidance to principals and SEILs on the PD cycle does not describe the procedures for managing poor performance or what happens if the overall assessment outcome is ‛does not meet requirements’.

Where unsatisfactory performance is identified, the principal contract of employment and Schedule 4 of the VGSA 2017 require DET’s secretary to provide a written notification to the affected principal. Schedule 4 also describes a support period with a focus on feedback and progress. A decision on employment is made at the end of this support period.

DET’s guidance to SEILs and principals explains that the mid-cycle review conversation is an opportunity to identify if a principal may be at risk of not reaching their targets. If this is the case, then the principal and SEIL are encouraged to discuss progress and evidence, possible practice improvements and refine the goal if appropriate. The SEIL confirms expectations for improvement prior to the end of cycle review. Interviewed SEILs and principals agreed that this happens in practice. Interviewed area EDs stressed that they work with SEILs to identify and support principals who may need it.

The Differentiated Support for School Improvement initiative has four initiatives to help schools build teaching or leadership capabilities to improve school performance and student outcomes.

Three interviewed SEILs advised us that there is a lack of consistency across regions in assessing performance against the Schedule B accountabilities. In particular, they said that they lack guidance on how to define and identify underperformance in relation to these accountabilities and how to manage it effectively. In the absence of guidance, they said that they use their professional judgement to identify cases where they think a principal may need support to meet the Schedule B accountabilities. SEILs also draw on resources available through DET’s area and region offices, including DET’s Differentiated Support for School Improvement initiative.

2.7 User experience of eduPay’s PDP module

DET provides a range of technical support, quick reference guides and e-learning modules about eduPay’s PDP module. DET’s guidance materials are clear, comprehensive and consistent with its other guidance materials. The e-learning modules provide real-life examples of principals and their approach to the PD cycle.

However, principals rarely interact with DET’s support materials for eduPay’s PDP module. Over half of the principals we surveyed described DET’s PDP technical guidance as ‛not at all helpful’. Interviewed principals said that they engaged with the module as little as possible. Analytics for DET’s People Division website show no engagement with the e-learning modules. The People Division has a communication plan to increase principals’ awareness of and engagement with e-learning modules.

Interviewed SEILs and principals consistently described eduPay’s PDP module as ‛clunky’. In particular, interviewed principals and SEILs cited issues in accessing or using the module. This included instances where SEILs who were new to the role or temporarily acting in it experienced considerable delays in gaining reviewer access to principals’ PDPs. They advised us that this caused delays or an inability to complete the PDP process.

Some interviewed and surveyed principals also experienced time out issues while filling in the module’s online fields. To work around this problem, some reported completing their PDP in a separate document and uploading it as an attachment. Our analysis of the 2019 eduPay dataset found that 100 of 1 326 PDPs were blank but had attached documents, which indicates use of this workaround.

Interviewed principals and SEILs were critical of the number of check and acknowledgement steps in the eduPay PDP process. Some interviewed SEILs and principals described working around this by waiting until mid or end-of-cycle review meetings to complete multiple steps at once. While these principals and SEILs are still completing all of the required steps, they delay recording these steps in the eduPay module and may instead keep records via email.

Ten per cent of surveyed principals provided open text comments stating that the 2019 PDP module was difficult to use. Eighty-three per cent of respondents disagreed with the statement that the current performance review process, including eduPay, minimises the administrative burden of preparing PDPs.

Our analysis of the 2019 eduPay dataset found that 8 per cent of principals did not use the eduPay module as intended in 2019. In these cases, principals did not use the module's template and instead maintained personal records. This impacts the tool’s usefulness for reviewers and approvers.

Improvements for the 2020 cycle

DET advised us that it reviewed the online PDP process for 2019 and has implemented improvements for the 2020 cycle. It identified the 2019 process as time consuming and difficult to navigate, and found that multiple steps led to repetitive exchanges between principals and SEILs. Other steps were confusing or easily missed.

DET also advised us that it consulted with principal representative associations in December 2019 and demonstrated proposed process improvements to them. These improvements are aligned with DET’s principal PD policies. Some of these changes include:

- reducing the number of steps from 12 to 10 and making two of them optional

- simplifying the processes for filling in the goal template and sharing comments between principals and SEILs.

DET has also connected LearnED, which is its electronic document management system, to eduPay’s PDP module. This means that when a principal completes an e learning module it is automatically recorded to their PDP. Principals can add any learning that they complete in an external environment to LearnED. So far, this functionality has not been widely used.

DET advised us that some of the performance issues with eduPay’s PDP module were due to some employees attaching large documents to their PDPs. There is now a limit on attachment size and DET reports that no further performance issues have been raised.

DET has also addressed issues with reviewers being unable to access PDPs. The system now allows a current reviewer to transfer PDPs to a new reviewer. SEILs have advised DET that they are using this function. Administrator users, such as business managers within schools and support officers in DET’s area and regional offices and People Division, can also perform these transfers.

2.8 Monitoring the PD cycle

Regional directors, area EDs and SEILs implement the PD cycle and support principals to meet PDP timelines. They do this by providing advice about goal setting, prompting principals about PDP milestones and scheduling review conversations.

DET’s area offices

Our interviews with DET’s regional directors and area EDs showed that area EDs play an important role in the principal PD process including:

- communicating principal performance expectations, approaches to goal setting and targets, and evidence types to support PDP assessments to SEILs

- chairing regular meetings with SEILs to discuss school and principal performance, the type of advice and support that DET can provide to principals and moderating assessment outcomes

- supervising the completion of the principal PD cycle, particularly ensuring timely completion of PDP milestones.

One way that area EDs perform this support role is through participating in regular meetings with their region’s executive team to discuss the principal PD cycle. For example, one region provided us with documents that outlined their 2020 agenda for monthly strategic meetings with area EDs. Principal PDPs were discussed in January, with a focus on goal setting, targets and managing Schedule B accountabilities. In September, the discussion focused on the end-of-cycle review.

Local government areas are equivalent to networks in DET’s regional operations model. DET groups networks into area offices.

Area EDs have an impact on the content and timing of the principal PD process and influence when principals complete PDP milestones. For example, in the 2019 PD cycle, 97 principal PDPs (or 7 per cent) recorded completion of the mid-cycle review milestone by the 31 July due date. One area office accounted for 42 PDPs (or 43 per cent) of the completed mid cycle reviews. The local government areas within this area had mid cycle review completion rates between 44 and 83 per cent. The mean completion rate for this milestone was 61 per cent.

The rate of PDPs completed by the 2019 deadline (31 December 2019) was also highly localised. Of the 362 PDPs completed by this milestone, 65 per cent came from two of DET’s areas in the same region. The mean completion rate for these two areas was 89 per cent compared to the statewide completion rate of 27 per cent.

This indicates that area EDs are well placed to support consistent practices for the principal PD cycle across the state. However, DET’s policy and procedure documents do not recognise and outline the role of area EDs in the PD process.

3. Understanding principals’ performance and learning and development needs

Conclusion

DET does not have a comprehensive understanding of principal performance or learning and development needs across its regions or the state. It does not analyse performance outcomes, systematically monitor how principals participate in the PD cycle or routinely analyse principals’ professional learning and development needs.

This is a missed opportunity to take a more evidence-informed approach to improving principal performance through tailored and targeted performance and professional development.

This chapter discusses DET’s understanding of:

3.1 DET’s understanding of PD participation and outcomes

Completing a PD cycle provides employees, their manager and the organisation with a range of information. This information helps fulfil some of the PD cycle’s purposes, such as:

- using outcomes data to administer salary progression

- using individual performance assessments to foster future talent and career development

- providing assurance that individual work contributes to the organisation’s strategic goals.

DET does not sufficiently monitor or report on the progress and outcomes of the principal PD cycle. Our analysis also revealed poor timeliness and completion rates for each of the PD milestones.

How DET monitors the PD cycle

DET's eduPay PDP module records each principal’s PDP from development through to their assessment outcome. It captures time and date stamps for completed steps within the PD cycle. It also captures identifying data, such as DET branch, school, reviewer and approver data. We analysed this data from the 2019 PD cycle.

DET’s People Division does not make use of this data to monitor or report on the timeliness or completion rates of principals’ PDPs. It also does not undertake a quality assurance process to test compliance with DET’s PD policy.

Interviewed regional directors, area EDs and SEILs described a regular communication process with principals to ensure compliance with PDP timelines. Regional directors and SEILs have access to reporting views and tools in the PDP module that identify each PDP’s status at a point in time. Interviewed SEILs and regional directors confirmed they use these tools, with SEILs more likely to monitor progress through the PD cycle.

Timeliness and completion rates of principal PDPs

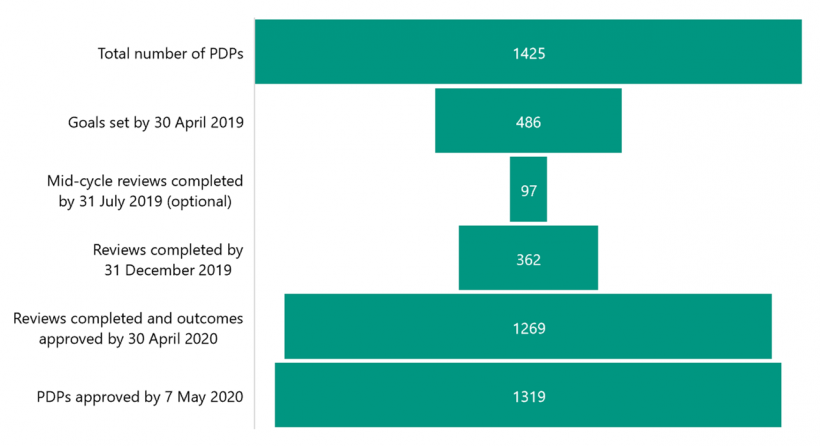

Our analysis of the 2019 eduPay dataset found that timeliness and completion rates for principal PDPs and PDP milestones are significant issues. Figure 3A shows these results.

FIGURE 3A: Timeliness and completion rates of 2019 PDP milestones

Source: VAGO, from DET’s 2019 eduPay dataset.

In Figure 3A, ‘Total number of PDPs’ represents the number of principals in the 2019 PD cycle. Only 34 per cent of PDPs met the goal-setting milestone (30 April 2019) and only 25 per cent met the PDP review completion milestone (31 December 2019).

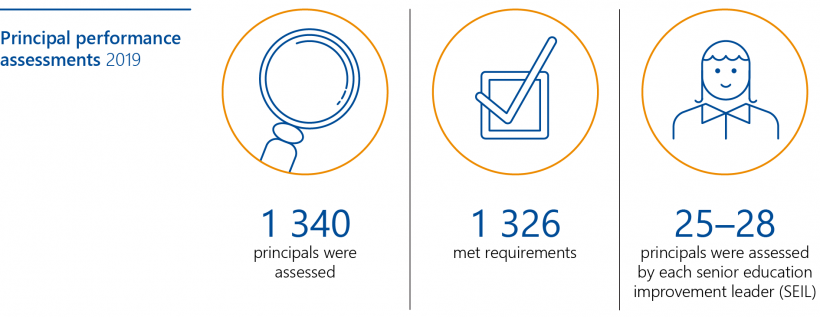

Our survey of principals (see Appendix D) asked about their participation in the optional mid-cycle review. In our survey, 97 per cent of survey respondents reported a mid-cycle meeting with their SEIL. This indicates at least 476 principals, or one third of the 1 340 principals assessed in 2019, had a mid-cycle review in 2019.

For 72 per cent of respondents, this meeting was an individual, face-to-face meeting and for 21 per cent, it was a group face-to-face meeting. Three per cent of respondents reported meeting online or via telephone and 1 per cent reported only receiving written feedback. Three per cent of respondents reported not having any type of mid-cycle feedback.

The discrepancy between eduPay data and survey data may be explained by the poor user experience of the PDP module in 2019 (see Section 2.7). Feedback from interviewed principals and SEILs also indicates that recording PD milestones in eduPay may not have occurred at the same time PD activities were conducted. In these circumstances, SEILs and principals described sharing PDP information via email.

Completion rates for 2019 PDPs increased to 89 per cent by 30 April 2020 and 93 per cent on 7 May, which is the date that DET retrieved PDP data for this audit. This means that most principal PDPs are completed according to progression cycle milestones, rather than PD milestones throughout the year. The progression cycle runs from May to April the following year. All principals must be advised of their final outcome by 30 April and salary progression occurs on 1 May.

Responses we received from SEILs and principals indicate that goal setting and other PD milestones likely occurred during the 2019 PD cycle, even if they were not recorded in the eduPay module in a timely manner. This means that DET's view of participation and timeliness in the PD model is limited and hampers its ability to monitor implementation and ensure meaningful engagement with the PD process.

DET does not have a comprehensive understanding of principal performance

While DET has an aggregate view of principal performance outcomes at a regional and statewide level, it does not analyse performance outcomes data to ensure that assessments are conducted consistently or to better understand principal performance.

Each role in the PD model has access to different types of data or performance information produced by each PD cycle. All roles have access to the PDP module in eduPay, except for the area ED.

|

If your role is … |

Within the eduPay PDP module you can … |

|

Employee/principal |

Review your own PDP, attachments, SEIL comments and assessment outcome |

|

Reviewer/SEIL |

Review the PDPs of principals in your network, their attachments, your comments and their assessment outcomes |

|

Approver/regional director |

View the PDPs of principals in your region, their attachments, reviewer comments and record assessment outcomes |

|

People Division staff |

View overall performance assessment outcomes for principals |

The area ED does not have access to principals' PDPs within the eduPay module.

This has significant implications for how DET understands principal performance. SEILs and area EDs have important roles in implementing the PD model but the area ED plays this role without access to information in the eduPay PDP module. This means that while detailed knowledge of principal performance is strongest at the local or area level, this information is not formally gathered or analysed at this level.

Assessment outcomes

For 2019, 14 principals, or 1 per cent of Victorian principals, were assessed as not meeting expectations for their overall performance. Nine of 76 reviewers made these 'not met' determinations, four reviewers each assessed one principal as not meeting expectations and five reviewers each assessed two principals as not meeting expectations.

The remaining 99 per cent of principals were assessed as meeting expectations. If a principal is assessed as 'meets expectations' and they are not presently at the top of their salary band, they receive a salary progression. Principals at the top of their salary band do not receive a salary progression.

DET advised us that due to its VGSA 2017 commitments, it does not examine the range of performance for principals who do meet expectations. DET's People Division does not conduct analysis into assessment outcomes at the level of individual PDP goals.

Such analysis would uncover whether SEILs make use of the three-point scale, whether this use is consistent and patterns in principal performance that will enable it to address systemic performance issues or development needs. Analysis of de identified data would yield these insights without compromising DET's commitment under the VGSA 2017.

We analysed the 2019 eduPay dataset to also understand if SEILs make use of the three-point scoring system available for individual PDP goals. This information, which is available to SEILs and regional directors, could provide DET with more insight into the range of principals' performance, if they were to use this information.

SEILs rarely used the ‛partially meets expectations’ rating for the four PDP goals. Of the 76 reviewers in the 2019 PD cycle, 44 per cent did not use the ‛partially meets expectations’ rating on any PDP goals.

The SEILs who used the ‛partially meets expectations’ rating are not distributed evenly across DET’s four regions. Figure 3B shows the number of reviewers in each region who used this assessment rating.

FIGURE 3B: Number of reviewers who used the ‛partially meets expectations’ rating in 2019 by DET region

| Region (and total number of reviewers) | Used ‘partially meets expectations’ less than 10 times | Used ‘partially meets expectations’ more than 10 times | ||

| Number of reviewers | Number of principals they collectively review | Number of reviewers | Number of principals they collectively review | |

| Region 1 (22) | 6 | 126 | 1 | 19 |

| Region 2 (18) | 8 | 151 | 5 | 109 |

| Region 3 (18) | 9 | 189 | 2 | 40 |

| Region 4 (18) | 15 | 126 | 1 | 16 |

Source: VAGO assessment of DET’s 2019 eduPay dataset.

Region 4 has the highest number of SEILs who used ‘partially meets expectations' which is nearly double the number who did in Regions 1 or 2. There is also an uneven distribution of reviewers who use this rating frequently (more than 10 times).

This analysis indicates that SEILs vary significantly in their performance assessment approaches and that principals experience a performance assessment based on the approach of their SEIL rather than a consistent method across the state.

Analysing SEILs’ use of ‛partially meets expectations’ ratings would provide DET with an understanding of how principals and SEILs approach the PD process and if SEILs are taking the opportunity to provide a more nuanced assessment of principal performance. Expanding the analysis would also help DET understand patterns in principal performance, monitor consistency of assessment and identify areas for targeted support.

Adopting a different assessment scale

Our survey asked principals to rank their preference for three different scales to assess their overall performance (not just individual PDP goals). We asked them to rank the following:

- a four-point scale (does not meet requirements, partially meets requirements, meets requirements, exceeds requirements)

- a three-point scale (does not meet requirements, meets requirements, exceeds requirements)

- a two-point scale (does not meet requirements, meets requirements), which is the scale currently used to assess overall performance.

Forty-eight per cent of respondents ranked the four-point scale as their first preference, 6 per cent preferred the three-point scale and the remaining 46 per cent chose the current two-point scale as their first. As 54 per cent prefer a more nuanced scale than 'meets' or 'does not meet', this suggests that a more nuanced assessment of principals’ overall performance may be widely acceptable.

The preference for a ranking scale that includes ‛exceeds requirements’ reflects the views of most principals we interviewed. These principals did not experience a celebration of their achievements in school improvement or leadership. One SEIL we interviewed made a similar comment, observing that there were ‛a lot of high performers who live in the absence of being told they’re doing a good job’.

Adopting a four-point rating scale would also be in line with the better practice VPSC Framework (see Appendix E).

Reviewers’ feedback practices

DET advises SEILs to give principals feedback to explain their assessment outcomes and provide guidance for future development. Its guidance materials state that SEILs must provide principals with written feedback but does not specify if this is required for each goal and Schedule B accountability.

Of 1 319 PDPs approved by 7 May 2020:

- 96 per cent had reviewer comments in at least one of the six sections

- 56 per cent had reviewer comments in all six sections.

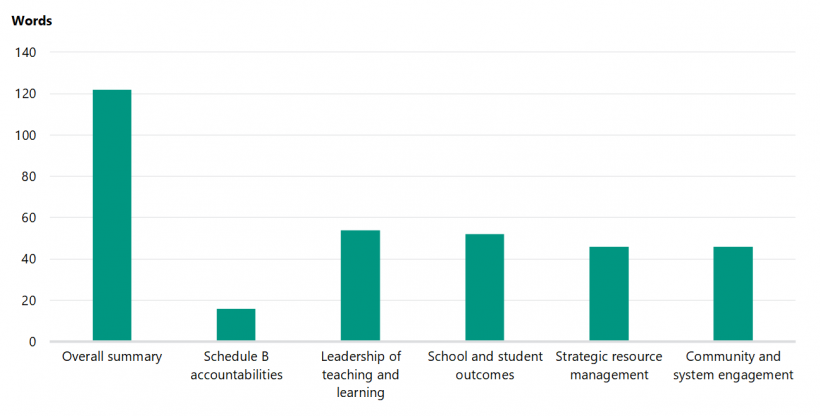

As Figure 3C shows, the length of reviewers’ comments varied by section. Reviewer feedback was longest in the overall summary section. Here, the mean word count was 121 words and the maximum word count was 1 321. The Schedule B accountabilities section had the least feedback. Our analysis indicated that this section is most likely to hold an affirmative statement that the principal met these accountabilities.

FIGURE 3C: Mean word length of reviewer feedback by PDP goal domain, accountability and summary assessment

Source: VAGO, from DET’s 2019 eduPay dataset.

Reviewers gave more feedback for goals that were strongly associated with AIP goals. The mean word count for the ‛leadership of quality teaching and learning’ and ‛school and student outcomes’ sections were similar at 54 words and 52 words respectively. The mean word count dropped to 46 words for the ‛strategic resource management’ and ‛strengthening community and system engagement’ sections.

The relationship between SEILs and principals