Victorian Electoral Commission

Overview

This audit assessed the Victorian Electoral Commission's (VEC) election planning systems, its performance across a range of indicators and its ability to engage the voting public and provide accessible services.

The 2014 state election challenged VEC to provide high-quality, user-friendly services to voters with varied needs due to record numbers of contesting parties and early voters who turned out in record numbers—almost 25 per cent of the voting population. Dissatisfaction with queuing rose amongst early voters, however, overall satisfaction was high at 92.6 per cent. VEC continued its good record of hosting secure events and improved protocols for securely handling ballot materials. Continuing to publish election indicators and including indicators for engagement and outreach activities will allow all stakeholders to transparently track VEC's performance.

Ensuring that the volume of election officials' administrative work is completed correct is also a persistent challenge. VEC is continuing to focus on this issue to provide innovative solutions for future elections.

VEC also needs to evaluate and continue to improve its programs to encourage participation by groups who are traditionally underrepresented in the electoral system. The electronic voting system vVote designed for people with motor impairment, low or no vision, and limited English proficiency was poorly utilised and the accessibility super centre pilot has not been evaluated.

Victorian Electoral Commission: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER February 2016

PP No 130, Session 2014-16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Victorian Electoral Commission.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

24 February 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Kristopher Waring and Michael Herbert—Engagement Leaders Caitlin Makin—Team Leader Kim Westcott—Team member Rue Maharaj—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Ray Winn |

Running a successful state election requires staff with foresight, integrity and attention to detail. It also demands systems that produce accurate and secure results to exacting standards that are flexible enough to respond to fluctuating voter turnout. The Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) carries enormous responsibility for ensuring our democratic will is realised. An audit of the 2014 state election is an opportunity to provide assurance that this important institution is operating effectively and ensuring the integrity of our most fundamental democratic process.

This audit assessed VEC's election planning systems, its performance across a range of indicators and its ability to engage the voting public and provide accessible services.

VEC achieved high satisfaction rates among surveyed voters. Additionally, voter turnout improved on 2010 results despite unpredictable demand during the early voting period and the challenge of providing high-quality, user-friendly services to voters with varied needs. These are considerable achievements. Strengthened ballot handling procedures helped VEC to continue its good record of security. Continuing to publish results against election indicators and including engagement and accessibility indicators will allow all stakeholders to transparently track VEC's performance.

VEC continues to refine and improve election staff training with a series of written, online and face-to-face modules. Well-trained and responsive election officials strive to make your voting day as efficient as possible. Yet, while over 70 per cent of people were able to vote within 10 minutes, queueing to vote remains a source of frustration for many. Ensuring that the volume of election officials' administrative work is completed correctly is also a persistent challenge. These are two issues that VEC will need to provide innovative solutions to in future elections.

To encourage groups who are traditionally under-represented in the electoral system, VEC has programs to build awareness of democracy and the importance of all people having a say in who governs. VEC's advisory groups provide valuable input into these programs. I have recommended that VEC evaluates the suite of programs to understand the impact of accessibility super centres and why electronically assisted voting failed to attract the target audience in significant numbers. This will help VEC to examine the best way to accommodate voters and build engagement in communities who may feel disenfranchised.

Many stakeholders praised VEC's dedication to inclusiveness—particularly in providing tools to make it easier for people with disabilities to vote. However, there is a need for the state to prioritise government buildings for accessibility upgrades in order to boost the number of wheelchair-accessible venues available for voting centres.

I am pleased to see that VEC has been active in its response to our recommendations and has agreed to adopt them to continue its high standard of service to the voting public.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

February 2016

Audit summary

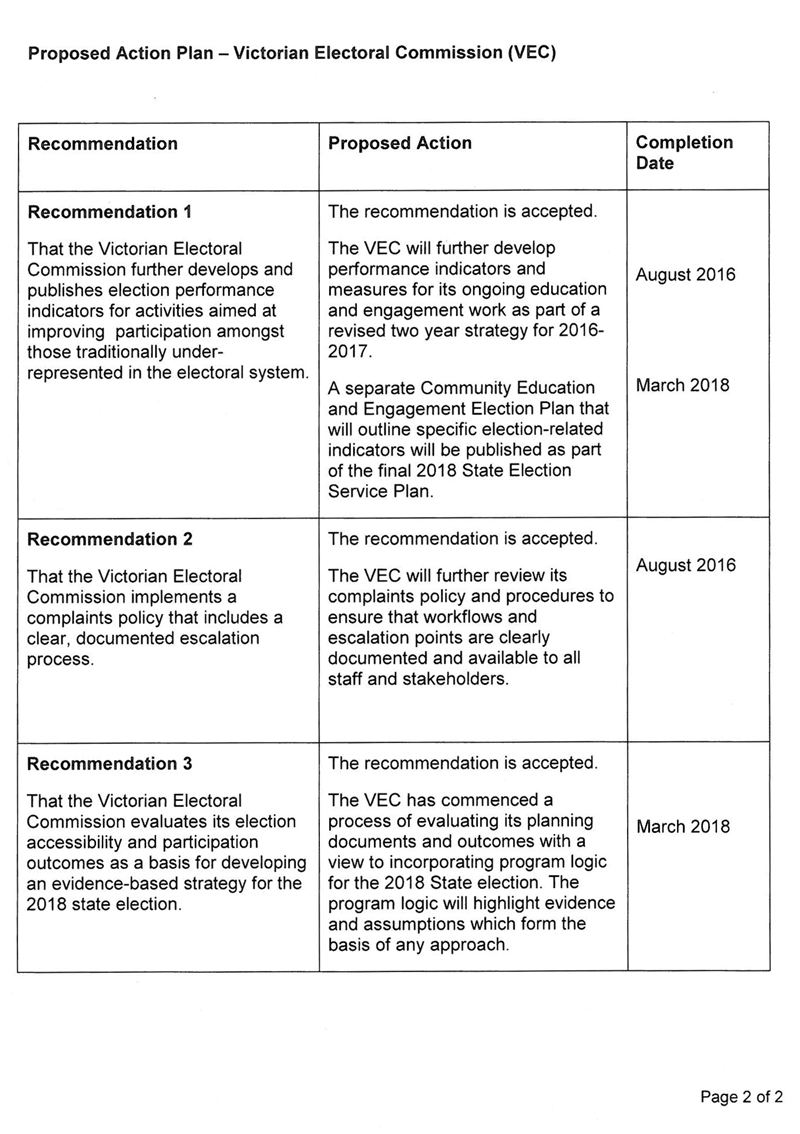

The Victorian state election held on 29 November 2014 involved recruiting and training over 20 000 temporary staff, setting up 1 786 voting centres across Victoria and providing information to 896 candidates, 21 political parties and over 3 800 000 eligible voters.

The Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) is set up as an independent statutory authority so that it can conduct elections impartially. The integrity of VEC relies on public trust in its ability to securely, accurately and efficiently count ballot papers and to educate and engage Victorians on their democratic rights, free from political interference.

Increasingly, voting services in Victoria must address a growing number of candidates and new political parties and must enable early voting for people unable to vote on election day. There is considerable public interest in alternative methods of voting—by post or by using electronic devices or online systems.

Removing obstacles to voting—for example, by providing sufficient options for wheelchair users and people experiencing homelessness and by providing tools for those with communication difficulties, intellectual disabilities, hearing impairments, and low or no vision—is critical to an inclusive, representative voting system. VEC promotes participation in the electoral system within communities who may be disengaged or who may lack awareness of the voting process, including those from diverse language backgrounds, those who have recently arrived in Australia, Indigenous Australians and young people.

This audit assessed whether the 2014 state election was effectively planned and encouraged full participation in the voting process. This involved reviewing VEC's planning, recruitment and logistical processes, its performance against indicators in the state election service plan, and complaints and satisfaction data. In addition, the audit assessed VEC's participation and engagement programs.

Conclusions

VEC faced unique circumstances in the 2014 state election, including unprecedented numbers of political parties registering to contest the election and high early-voter turnout across the state. This created challenges to deliver services that were high quality, inclusive and responsive to changing voter and candidate needs. Yet, VEC delivered an election that kept pace with previous levels of timeliness, accuracy and voter satisfaction. There were no security breaches—in fact, VEC strengthened its processes for the movement and storage of ballot materials.

VEC performed well against its key performance indicators, which were published prior to the election, for the first time, in 2014. This made VEC more accountable for its election services. However, the indicators can be improved by including a greater range of key performance indicators that demonstrate accountability to all voters—including those who have difficulties voting or are unlikely to do so. There are a range of positive engagement programs for under-represented communities that VEC currently undertake. VEC could publicly commit to these initiatives and be held accountable through public performance indicators and outcomes that target culturally and linguistically diverse, Indigenous and other communities. Ensuring that targets and indicators promote inclusiveness and are sufficiently ambitious is the next step.

Findings

Planning

VEC has developed planning tools to assist staff in setting up and rolling out voting centres across the state. These tools helped VEC to meet its planning milestones in relation to office set up and readiness to open. Senior election staff are trained to solve problems with the support of a network of experienced staff. The major problem faced by staff in early voting centres—open two weeks prior to election day—was the unprecedented rise in early voting. Guidance and advice was available to those managing early voting centres, but queue lengths grew in centres across the state. VEC's planning allowed for an increase in the number of people voting in the early voting period, however, demand was unprecedented—almost 70 per cent higher than in 2010. This had some impact on voter satisfaction with queue lengths but did not, on the whole, interfere with VEC's ability to conduct the election in a secure and accurate manner.

Photograph courtesy of the Victorian Electoral Commission.

Performance

Satisfaction with the voting experience remained high in 2014 across different categories of voters—over 90 per cent of early voters satisfied with their experience. However, the proportion of early voters who felt they had to queue for too long jumped from 1 per cent in 2010 to 20 per cent in 2014. VEC acknowledges that some voters experienced long queues when voting early.

While first-preference results were counted at a slightly faster rate than for the 2010 election, only around 60 per cent of votes were counted on election night. A high number of early votes can impact on VEC's ability to complete early vote counts on election night. This can impact upon their capacity to identify on election night, which party may have enough seats to be able to form government, where the outcome is close. However this was not the case in 2014. Early votes are not typically counted until the Monday following the election. Following the 2014 election, VEC recommended to Parliament that legislation be amended to allow pre-sorting of votes, to improve its ability to count early votes on election night and provide greater certainty to parties.

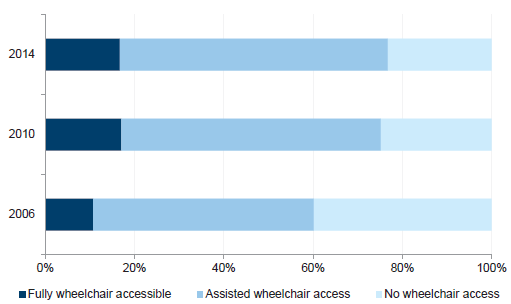

VEC published key performance indicators before the election and met those related to booking and opening early voting centres on time, and counting first-preference results, enrolled voters and voter turnout. It did not meet its target for fully wheelchair-accessible venues due to a lack of available fully accessible buildings.

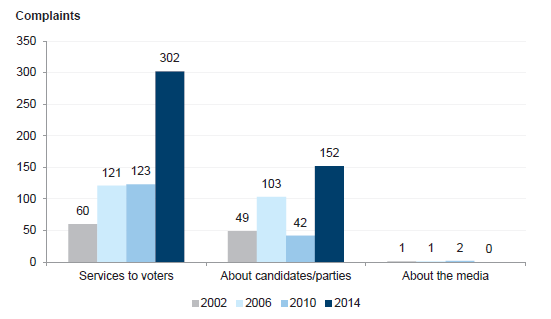

Complaints also rose, with 454 complaints registered in 2014–15, compared to 167 for the 2010 state election. This increase impacted VEC's ability to respond to complaints within the agreed time, however, the responses were consistent, and complaints were investigated and resolved appropriately.

Accessible voting

Providing sufficient numbers of voting venues that accommodate wheelchair users is an ongoing challenge for VEC. It relies on a mix of government and privately owned buildings with often limited accessibility. A comprehensive accessibility tool is used to rate venues, and VEC provides a range of information on its website. VEC set an ambitious target for fully wheelchair accessible voting centres, but this target was not met. At the request of its disability advisory group, VEC will provide additional information online for future elections, so that voters with particular accessibility requirements can determine which voting centres are accessible to them, rather than relying only on the rating provided by election staff.

VEC developed tools to assist people who have communication difficulties to navigate the voting process with greater ease. A number of stakeholders agreed that VEC is strongly committed to engaging with, and providing accessible services to, people with a disability.

The accessibility super centres were a pilot, designed to provide additional supports to people with disabilities and language difficulties. The electronically assisted voting system, vVote, designed for people with low or no vision and communication difficulties, was poorly utilised by these cohorts. It will be difficult to expand vVote for broader use. Due to their complexity both vVote and the super centres require extensive staff training. The super centres—based in six locations across Victoria—were not practical for those who prefer to vote locally, where the route and venue itself are more familiar.

VEC's civic participation programs attempt to reach parts of the community who traditionally do not vote or who find it difficult to vote. VEC's promising ῾Democracy Ambassadors' project aims to build the capacity of leaders in Horn of Africa communities to engage others in the democratic process. Other projects raise awareness of voting and democracy to people in disability group homes, homeless people and young Aboriginal leaders, among others. The impact of these projects is difficult to assess. VEC has started to record information to assist with evaluation of these projects and understanding improvements in enrolments.

Recommendations

That the Victorian Electoral Commission:

- further develops and publishes election performance indicators for activities aimed at improving participation among those traditionally under-represented in the electoral system

- implements a complaints policy that includes a clear, documented escalation process

- evaluates its election accessibility and participation outcomes as a basis for developing an evidence-based strategy for the 2018 state election.

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Victorian Electoral Commission throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to the Victorian Electoral Commission and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Elections need to be conducted with high levels of scrutiny, transparency and security to maintain public confidence in the democratic system. Voters need to be confident that their ballot paper is secret, securely transferred and counted using robust and verified methods. Voting is an enshrined human right in the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006, so all eligible voters need to have reasonable access to cast their vote in elections.

Enrolling to vote has been compulsory in Victoria since 1923, and Australian citizens over the age of 18 are eligible to vote. There were 3 806 301 voters enrolled in Victoria for the November 2014 state election, and 93.02 per cent of those enrolled cast a vote. In this election, there was also an increase in registered political parties contesting the election, from 10 in 2010 to 21 in 2014.

1.2 About the Victorian Electoral Commission

1.2.1 Role of the Victorian Electoral Commission

The Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) is an independent statutory authority, established under the Victorian Electoral Act 2002 (the Act). VEC is not subject to the direction or control of government.

The Electoral Commissioner and Deputy Electoral Commissioner are appointed by the Governor in Council for a period of 10 years.

Among others, the responsibilities of the VEC are to:

- administer voter enrolment and maintain the Victorian electoral roll

- conduct:

- Victorian state elections

- by-elections

- local council elections

- other statutory, commercial and community elections and polls and referendums in Victoria

- report to Parliament on the conduct of each election

- promote public awareness of electoral matters

- conduct and promote research into electoral matters

- administer compulsory voting enforcement.

VEC's vision is 'all Victorians actively participating in their democracy'. This vision is underpinned by VEC's purpose, 'to deliver high quality, accessible electoral services with innovation, integrity and independence'.

1.2.2 Independence and oversight

The Electoral Matters Committee (EMC) is a joint investigatory committee of the Parliament of Victoria. EMC conducts inquiries and reports on:

- issues related to the conduct of state and local government elections in Victoria

- any matters related to the administration of the Act.

EMC is currently conducting an inquiry into the 2014 state election, which it expects to complete on 30 April 2016. It is also holding an inquiry into electronic voting, for completion by 30 April 2017.

Following an election, VEC reports to Parliament on the conduct and results of the election. These reports may include recommendations regarding possible legislative changes. VEC's report on the 2014 state election was tabled in Parliament in September 2015.

1.2.3 Relevant legislation

VEC's functions are governed by legislation including:

- Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006—enshrines the human rights of the Victorian population, including the right to vote.

- Constitution Act 1975—sets out who is entitled to enrol to vote, who is entitled to be elected to Parliament, and the size and term of Parliament.

- Disability Act 2006—reaffirms and strengthens the rights and responsibilities of people with a disability.

- Disability Discrimination Act 1992(Commonwealth)—protects people with a disability against discrimination.

- Electoral Act 2002—establishes VEC as an independent statutory authority, sets out the functions and powers of VEC and prescribes processes for state elections and referendums.

- Electoral Boundaries Commission Act 1982—nominates the Victorian Electoral Commissioner as a member of the Electoral Boundaries Commission.

- Equal Opportunity Act 2010—promotes equal opportunity in Victoria and legislates against discrimination.

- Local Government Act 1989—provides for the conduct of local government elections and electoral representation reviews.

- Infringements Act 2006—prescribes stages 2 and 3 of the compulsory voting enforcement processes.

1.3 The 2014 Victorian state election

The Victorian state election was last held on 29 November 2014. Figure 1A provides some statistics about the conduct of the election.

Figure 1A

2014 election statistics

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

1.3.1 Resources

Victorian state elections are held every four years on the last Saturday of November. Leading up to the 2014 state election, VEC:

- established 56 election offices, 100 early voting centres and eight region recheck centres

- appointed 1 786 voting centres, 183 senior election officials, 16 298 election officials and around 6 890 casual roles

- provided training manuals and programs for election officials

- produced over 12 million ballot papers.

1.3.2 Planning for the election

Elections are significant logistical and financial undertakings, and by-elections, in particular, can take place with very little notice. A considerable amount of work takes place before and after the election but staffing levels peak on election day. This places considerable pressure on VEC's equipment and venues, and on staff—most of whom are temporary—to perform. The scale of operations and pressurised nature of the work increases the risk of error in an environment where timely and accurate outcomes are essential, especially where results are close.

VEC publishes a service plan prior to the state election to assist stakeholders, the media and the general public to understand the election services that will be delivered. The service plan provides an election time line, key milestones, counting methods, and an overview of the proposed communication campaign. In addition, there is information for registered political parties, independent candidates and for those wishing to vote early by post, in person or electronically. A draft is sent to political parties and other stakeholders for comment and is then refined and released prior to the election.

State election key performance indicators

For the first time, the 2014 state election service plan included indicators to measure election preparation, conduct and outcomes, so that the public can track VEC's performance. VEC published results against its indicators in the commissioner's report to Parliament in September 2015. The indicators are summarised in Figure 1B.

Figure 1B

The VEC 2014 state election key performance indicators

|

Election preparation These indicators are measured using milestones for logistical projects such as venue booking, set up and opening, and electoral roll production. Election conduct These indicators relate to the efficiency of counting, satisfaction with services and complaints management, derived from data on the election management system (EMS), survey results and records management system. Election outcomes These indicators relate to the enrolment rate, voter turnout and informality. The results are derived from data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and EMS. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3.3 Voting methods

Most Victorians vote in state elections by attending a voting centre on election day. The Act, however, provides alternative voting methods for particular groups who are unable to vote on election day.

Early voting

The Act allows early voting for a person who 'will be unable to attend an election day voting centre during the hours of voting on election day' and who makes a declaration that they will be unable to attend. The declaration can be signed to accompany a postal vote or can be a verbal declaration to voting centre staff at an early voting centre.

Early voting centre staff are advised in their training manual to check the elector is enrolled or entitled to vote and to ask if the person is unable to vote on election day. Confirmation of this statement by the elector is considered a declaration under the Act and enables them to vote in the early voting period.

Electronically assisted voting

The Act permits electronically assisted voting for people who are interstate or overseas and for people who have no or low vision, motor impairment or limited literacy skills. For the 2014 state election, VEC implemented vVote, an electronically assisted voting system. This was available at 25 early voting centres within Victoria and London, but was not available on election day.

Photograph courtesy of the Victorian Electoral Commission.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to examine the efficiency, effectiveness and economy of VEC in the context of the conduct of state elections. To assess this objective, the audit examined whether the 2014 state election was:

- well planned, efficiently and securely conducted, with outcomes thoroughly evaluated

- inclusive and accessible, encouraging full participation in the voting process.

The audit examined VEC and the planning, procedures, systems and arrangements used during the 2014 state election. This included a review of the electronic election management system, procurement processes and handling of election staff training. Consistent with previous practice, identified issues relating to the electronic EMS have been conveyed to VEC through a management letter. This letter provides detailed recommendations around matters including software security, password management and user access controls. In addition, issues relating to procurement processes and election staff training were also conveyed to VEC through the management letter. The audit did not consider local council elections. The audit also excluded boundary reviews or the management of the electoral roll.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion. Audit evidence was gathered through system, document and file review and interviews with VEC staff and other stakeholders, as well as reviewing research and reports tabled in Parliament.

The total cost of the audit was $392 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 discusses whether VEC effectively and efficiently planned, conducted and evaluated the 2014 Victorian state election.

- Part 3 discusses whether the 2014 state election was inclusive and accessible and encouraged full participation in the voting process.

2 Election planning and performance

At a glance

Background

The Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) is responsible for conducting the state election on a fixed, four-year cycle. The 2014 election was characterised by a record number of contesting political parties, a high early voter turnout and increased security measures for the movement and storage of ballot papers.

Conclusion

The election was conducted securely, and VEC's planning systems assisted staff to set up efficiently. Queues at early voting centres were difficult to address with existing arrangements, impacting on the otherwise high rate of voter satisfaction. Evaluations by election managers show that some voting centre staff need to improve the accuracy of administrative work, however, this did not impact on the election results. Additional support assisted new election managers to confidently complete what is often stressful work.

Findings

- VEC has a sound planning framework for conducting the state election.

- Evaluations show the need to improve the accuracy of paperwork.

- VEC does not publish performance indicators for community engagement.

- The escalation process for complaints is unclear.

- Voter satisfaction and turnout were high, but the percentage of informal votes rose.

- An unprecedented high turnout of early voters led to longer queues at early voting centres.

Recommendations

That the Victorian Electoral Commission:

- further develops and publishes election performance indicators for activities aimed at improving participation among those traditionally under-represented in the electoral system

- implements a complaints policy that includes a clear, documented escalation process.

2.1 Introduction

Election planning for an event the size of the state election requires clear objectives, tight project management, flexibility and contingency planning. This part of the report reviews the effectiveness of planning tools and the election services Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) provided to Victorians during the 2014 election. Elections are significant logistical and financial undertakings, and by-elections, in particular, can take place with very little notice. For the majority of election staff, tasks are performed over a matter of days, with tight deadlines under the scrutiny of voters and scrutineers. This places considerable pressure on VEC to secure equipment and venues, and on staff—most of whom are temporary—to perform. The 2014 election was characterised by a record number of contesting political parties, a high early voter turnout and increased security measures for ballot paper storage and movement.

2.2 Conclusion

VEC have a range of checks and controls in place to ensure that elections are conducted in a secure, accurate and timely manner. The election performance indicators VEC developed in 2014 will need regular reviewing to ensure they are sufficiently ambitious and that they adequately cover VEC's duties—such as the engagement of disenfranchised communities.

The oversight and systems of cross-checking ballot movements and results—embedded in election functions—provide VEC with confidence in the security of the election and the accuracy of the declared election results. Continued increased support for newer voting centre managers and a greater focus on accuracy and completion of administrative work would further improve the efficiency of over 20 000 temporary staff.

Voter satisfaction surveys and complaints are also useful indicators of success. VEC was responsive and consistent in its responses to complaints but ultimately missed its response target, largely due to the significant increase in complaints.

Photograph courtesy of the Victorian Electoral Commission.

2.3 Election planning

VEC's application of a range of planning tools—together with good internal control over projects and resource allocation—provided a clear framework for operations in the 2014 state election. Flexibility inherent in VEC event systems meant they could partially mitigate the impact of higher-than-anticipated early voter turnout. Some voters reported experiencing long waits, however, the voter satisfaction surveys showed 80 per cent of early voters and 70 per cent of ordinary and absent voters waited under 10 minutes.

2.3.1 Election day

Election planners need to understand which voting centres voters will use and to resource these centres appropriately. VEC considers the major and local events that could impact on voter turnout at particular voting centres, but it is difficult to predict turnout with precision. Voter turnout at a particular venue can be influenced by the weather, sporting events, traffic conditions and pre-existing travel plans. Victorian voters are also able to vote outside their electorate with relative ease. Managing queues to prevent long waits can pose difficulties in unforeseen circumstances.

VEC's report to parliament on the 2014 election states, 'Due to Ö issuing a higher number of votes than anticipated, a small number of voting centres could not supply electoral materials, including ballot papers, to voters. Four complaints were received relating to this issue'. There were 1 786 voting centres operating on election day, and there is no evidence of insufficient voting materials in the vast majority of these centres. VEC note ῾All voting centres were resupplied with materials as quickly as possible.'

2.3.2 Early voting period

For the 2014 state election, VEC planned for early voting by using historical early voting data from the 2010 state election and projecting increases of 30 per cent or higher for each location. In reality, there was an increase of almost 70 per cent on the 2010 figures, resulting in over 25 per cent of the voting population voting early and 8 per cent voting by post. The high turnout of early voters led to long queues in some centres compared with 2010. A small number of early voting centres, limited by their physical space, contributed to delays in service. Voting centre location was influenced by availability and suitability of space, known areas of high traffic and recent district boundary changes. VEC committed to one early voting centre per electorate and provided additional early voting centres in the central business district, popular tourist locations around Gippsland, Portland and Swan Hill, and Melbourne and Avalon airports.

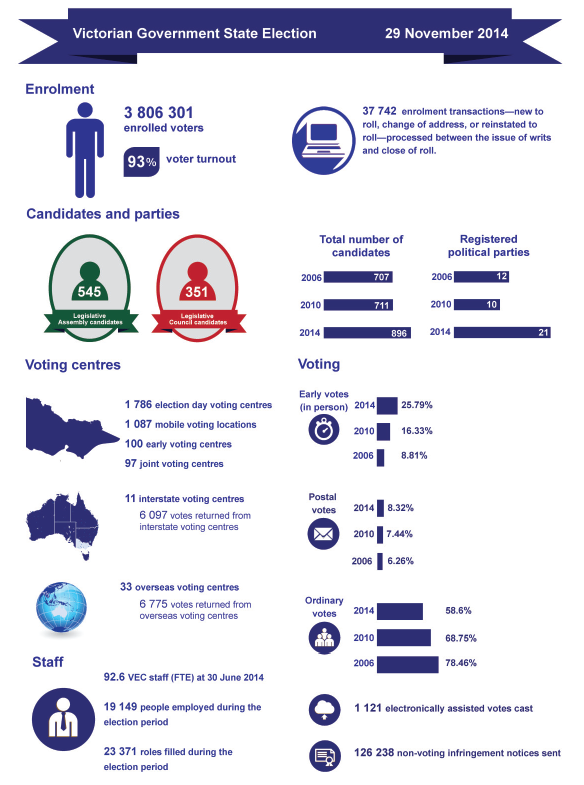

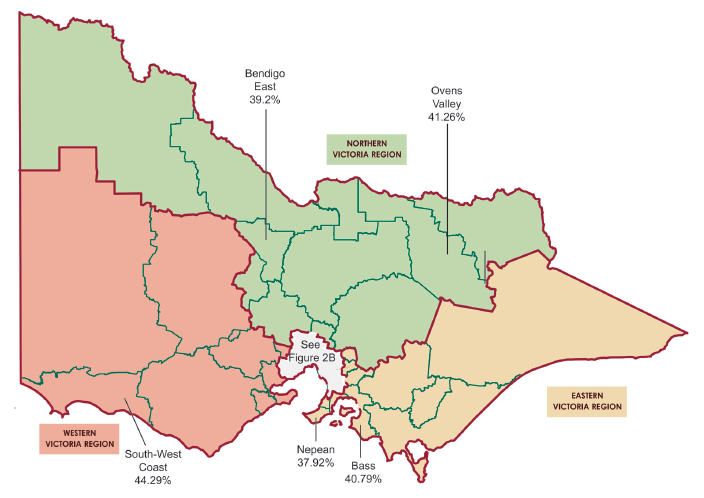

As predicted, early voting was most popular in regional Victoria. However, VEC did not anticipate the unprecedented statewide increase in early voting. Three coastal electorates—South West Coast, Nepean and Bass—were included in the top five regional electorates with the highest percentage of early votes, as shown in Figure 2A. Figure 2B shows the metropolitan districts with the highest percentage of early votes—these were all located in the Western Metropolitan Region.

Figure 2A

Regional districts with highest percentage of early voter turnout, 2014

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

Figure 2B

Metropolitan districts with highest percentage of early voter turnout, 2014

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

VEC's recruitment system allows for election officials to be hired in casual positions and to cover multiple roles, which means they can be deployed in basic roles at early voting centres that experience high demand. There is no cap on the number of staff that can be recruited to an early voting centre, however, training material suggests that total early voting staff hours remain within the guidelines recommended for voting centres. In reality, it may not be possible to meet spikes in demand lasting a few hours.

Feedback from voters shows that while dissatisfaction with queues rose, overall satisfaction with election services remained high.

Impact of high early voter turnout

High incidence of early voting can prolong vote counting. Political parties prefer early votes to be included in the election night count to reduce the potential for waiting for a clear result when an election is close. Early voting means there are fewer votes available to count on election night. Counting of early votes does not normally start until the Monday following the election. As voters are able to vote outside their electorate, all votes must first be sorted into their correct district and region before counting commences.

In 2014, only 62.9 per cent of all votes cast were counted on election night. However, timeliness of counting the district first preferences matched or exceeded that of the two previous elections. This means that over 60 per cent of district first preferences were recorded on election night, giving candidates a degree of certainty. VEC's report to Parliament on the 2014 election recommends that legislation be amended to allow VEC to begin sorting early votes before 6.00 pm on election night.

In its public submission to the Victorian Parliament's Electoral Matters Committee, VEC states that it will consider expanding its number of staff during early voting to include queue controllers who can better assist people who are aged or have a disability to proceed to the front of the queue.

2.4 Election performance

This section assesses how VEC performed in the election against indicators identified in its service plan, particularly regarding security of ballot papers, accuracy of counting and results, and management of resources. Voter satisfaction results and complaints also provide insights into the efficacy of voting services. Satisfaction was high but the number of complaints increased. Enrolment and turnout exceeded targets, but informality—the number of votes unable to be included because they were blank, illegible or completed incorrectly—was higher than predicted. Consistent with previous elections, no security issues were recorded, and new measures were introduced to improve counting and reconciliation transparency.

2.4.1 Performance against indicators

VEC met the majority of election performance measures related to election preparation. The enrolment rate and voter turnout exceeded targets, as did the timing for provision of Legislative Assembly first-preference results. Voter satisfaction with early and postal voting, however, was down compared with the 2010 state election.

For the first time, in 2014 indicators were included to measure election preparation, conduct and outcomes. The indicators largely measure timeliness, accuracy and participation. VEC published results against its indicators in the commissioner's report to Parliament in September 2015.

The performance indicators provide a snapshot of election outputs that allow stakeholders to understand VEC's progress against its core business. VEC also completes a range of important activities to increase participation and engagement among people who do not vote or find it difficult to vote. By publishing indicators for this work, VEC can be accountable to all stakeholders and reflect the effectiveness of these programs. Figure 2C shows how well VEC met a range of these indicators for the 2014 state election.

Figure 2C

VEC achievements against major performance objectives

|

Objective: Sufficient fully resourced and accessible voting centres will be available during the voting period. |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

|

Indicator |

Measure |

Target (%) |

Result (%) |

|

Number of voting centre venues booked and assessed by 1 August 2014 |

Proportion of total |

85 |

100 |

|

Number of voting centres fully resourced by deadline |

Proportion of total |

100 |

100 |

|

Number of early voting centres ready by deadline |

Proportion of total |

100 |

100 |

|

Number of fully wheelchair accessible venues provided |

Proportion of total |

25 |

16.7 |

|

Objective: The election will be conducted to a high standard within legislated and organisational time frames. |

|||

|

Indicator |

Measure |

Target (%) |

Result (%) |

|

Number of Legislative Assembly first-preference count results received from voting centres within two hours of close of poll |

Proportion of total |

75 |

76.6 |

|

Number of primary counts completed within five days of election day—based on total votes counted |

Proportion of total |

93.6 |

91.3 |

|

Number of complaints or election enquiries responded to or acknowledged within 24 hours or by the next business day |

Proportion of total |

100 |

89.4 |

|

Overall satisfaction level of voters |

Proportion of total surveyed |

93 |

92.6 |

|

Objective: Eligible voters will be enrolled and cast a formal vote, or provide a valid and sufficient excuse for not voting. |

|||

|

Indicator |

Measure |

Target (%) |

Result (%) |

|

Number of eligible voters enrolled at close of roll |

Proportion of eligible electors enrolled |

≥ 1% national average |

94.2 |

|

Voter turnout |

Votes counted as a proportion of the total electors enrolled |

93.0 |

93.0 |

|

Informality rate—Legislative Assembly |

Proportion of votes counted |

4.5 |

5.2 |

|

Informality rate—Legislative Council |

Proportion of votes counted |

3.3 |

3.4 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

The target for fully wheelchair accessible venues was not met—see Part 3 for further discussion of accessible venues.

2.4.2 Voter satisfaction with services

Overall voter satisfaction across all voter types remained high at 92.6 per cent. however the proportion of those who were extremely satisfied declined. VEC believes that this is the result of longer than expected queues during the early voting period. VEC arranged for a survey of voters and politicians to test the effectiveness of services and communication. Figure 2D contains their responses and recommendations for VEC.

Figure 2D

VEC voter satisfaction survey

|

Satisfaction—ordinary and absentee voters

Recommendations—ordinary and absentee voters

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from survey commissioned by Victorian Electoral Commission.

Complaints

The VEC received 454 complaints in 2014–15, compared to 167 for the 2010 state election. The number and categories of complaints received are detailed in VEC's reports on the state elections and in their annual report. A VEC email address, introduced in 2014, was used for over 85 per cent of complaints. A review of complaint handling found that responses to election complaints were managed consistently and 89 per cent of complainants received a response within 24 hours. Complaints management could be improved by the inclusion of a clear, documented escalation policy.

Categories of complaints

Figure 2E shows that in 2014 the single largest category of complaints made to VEC relates to services provided to voters. Out of these 302 complaints, 93 related to services, staff members and facilities throughout early voting and on election day, and 33 related to the queues and waiting times at voting centres. Although the VEC estimated the number of votes issued at each voting centre to within 99.83 per cent accuracy, the times people chose to vote was more difficult to predict. Queue lengths were monitored throughout the voting period and where queues remained for extended periods of time additional staff members were deployed as soon as possible.

Figure 2E

Complaints by category from the last four elections

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

A significant number of correspondents registered complaints arising from a misunderstanding of the electoral process, or the content of candidates' campaign material. The VEC will consider ways of providing further explanation and information in its communication and electoral education materials.

Complaints management

The complaints management process document does not include information about the responsibility or authority of staff to handle complaints, review processes or when complaints should be escalated. A review of a sample of complaints found that 86 per cent of complaints received a personal response from a VEC staff member and all were resolved satisfactorily. VEC believes that some gaps in the whole-of-commission understanding of the process may be responsible for the few instances of weak document management.

Complaints received by the complaints officer are tracked in a register. A complaints management policy was drafted in July 2015 but has not yet been approved by VEC's management group. While responses to complaints are currently handled in a consistent, fair and timely manner, without a clear escalation process and policy in place and greater emphasis on proper document management there is a risk that these factors may be compromised. A complaints management policy that details these areas would resolve this gap.

2.4.3 Accuracy and efficiency

VEC states that counts of the Legislative Assembly first-preference votes exceeded its target of 75 per cent of results available by 8 pm on election night. This shows that VEC were able to manage counting efficiently within the current operating environment. VEC exceeded its target by 1.6 per cent. Figure 2F shows the percentage of district first-preference results counted on election night. The efficiency of these counts has improved steadily since 2006.

Figure 2F

Percentage of district first-preference results counted at the last three state elections

|

Time frame |

District results 2006 (%) |

District results 2010 (%) |

District results 2014 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

6 pm to 7 pm |

15.1 |

17.0 |

18.3 |

|

7 pm to 8 pm |

68.0 |

73.0 |

76.6 |

|

8 pm to 9 pm |

91.8 |

93.6 |

94.8 |

|

9 pm to 10 pm |

96.4 |

98.9 |

98.9 |

|

10 pm to 11 pm |

98.4 |

99.9 |

99.8 |

|

11 pm to 12 am |

99.2 |

100 |

100 |

|

After 12 am |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Source: Victorian Electoral Commission.

Accuracy is also a function of election staff training. All election officials are evaluated according to the accuracy of their counting and paperwork. Analysis of the accuracy of voting centre managers' paperwork reveals that around 14 per cent failed to complete these tasks satisfactorily. However, evaluations of district and region managers and assistant managers showed higher performance on the accuracy of paperwork.

Ultimately, the paperwork of voting centre managers is rechecked and verified by election officials supervised by election managers, but some noted that this process impacted on the timeliness of rechecking ballot papers.

This rechecking and verification of paperwork can lead to longer working hours for staff. It is not known if this is common across other districts or whether it is the result of inexperienced managers in specific districts. VEC is aware of this risk and advises that improving administrative work such as paperwork accuracy has been a continual focus for election staff training.

VEC provided evidence of safeguards built into the election management software to avoid miscalculation. Additional manual safeguards include compulsory rechecking of ballots and oversight from scrutineers who are present during counting. Other processes track the movement of ballot materials and record reconciled ballot papers with the number of votes cast. A recent internal audit on the tracking and movement of ballot papers resulted in updates to a number of processes.

Recommendations

That the Victorian Electoral Commission:

- further develops and publishes election performance indicators for activities aimed at improving participation among those traditionally under‑represented in the electoral system

- implements a complaints policy that includes a clear, documented escalation process.

3 Election participation and inclusiveness

At a glance

Background

Some individuals who are entitled to vote can be reluctant to do so because of a lack of awareness of the voting process, not feeling connected to democratic systems or misunderstanding their right to vote. For others, there may be physical barriers that prevent them from voting—for example, voting centres that are not accessible to wheelchair users. The Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) promotes participation in the voting process among all eligible Victorians.

Conclusion

VEC worked with disability specialists to develop a range of accessibility tools for the 2014 election but despite this, a lack of suitably accessible buildings meant the wheelchair accessibility target was not met—electronic voting was also poorly utilised. A range of positive initiatives have been developed to engage communities who face challenges voting, including, newly arrived citizens, people experiencing homelessness and young people and another involves young Indigenous leaders. Some initiatives resulted in new enrolments and votes—but their true impact is unclear, due to the challenges in collecting relevant data and a lack of outcome evaluation of some of these promising initiatives.

Findings

- VEC's advisory committees provide valuable feedback that helps shape its access and engagement projects. The Indigenous advisory committee has been restarted after a period of inactivity.

- VEC struggled to find accessible voting centres to meet its target.

- VEC has only evaluated a selection of its participation and inclusion strategies.

Recommendation

That VEC evaluates its election accessibility and participation outcomes as a basis for developing an evidence-based strategy for the 2018 state election.

3.1 Introduction

The vision of the Victorian Electoral Commission (VEC) is to have ῾all Victorians actively participating in their democracy'. It has legislative obligations to encourage full participation in the voting process, which means actively engaging Victorians who may be disenfranchised or face physical, social, cultural or geographic barriers to voting.

This part of the report reviews how well VEC engages with—and provides services to—groups that traditionally have difficulties voting.

3.2 Conclusion

VEC has a number of positive programs targeted at improving voter participation. The electoral roll does not include information on ethnicity or disability, so the impact of these programs can be difficult to determine. Engagement with Indigenous communities in the lead up to the state election was lacking but is now showing signs of improvement. VEC assessed all voting venues for wheelchair accessibility but did not manage to increase the total number of accessible venues in 2014. This is an ongoing challenge that needs support from all levels of government when planning new infrastructure.

Tools to assist people with a range of disabilities were widely available. There has been limited assessment of the impact of vVote (VEC's electronically assisted voting system), the accessibility super centres or VEC's advisory committees. An evaluation of the impact of these activities will provide VEC with a sound evidence base to improve services for those who may face barriers to voting and participating in democratic systems.

3.3 Accessible voting

Accessible voting allows all voters to cast their vote, regardless of ability, geographic location or language barriers. This section reviews the effectiveness of VEC's actions to provide voting services that are inclusive and accessible.

3.3.1 Accessible voting centres

Finding sufficient stock of accessible voting centres continues to be an issue for state elections. VEC states that despite its best efforts, it continues to be disappointed with the lack of wheelchair-accessible venues available for use as voting centres—particularly given that most of the venues are owned by the state government. VEC has raised this issue with government but has seen little progress.

In the 2014 state election, 17 per cent of voting centres VEC secured were rated as fully wheelchair accessible—falling short of the 25 per cent target set in VEC's 2014 State General Election Service Plan. Figure 3A shows that while numbers of voting centres with either full or assisted wheelchair access rose between the 2006 and 2010 state elections, there has been little change since 2010.

Figure 3A

Accessibility of voting centres in Victorian state elections 2006–14

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

To rate the accessibility of a venue prior to selection as a voting centre, VEC developed an accessibility checklist with a company specialising in disability access. All voting centres were also equipped with maxi pencils, magnifying sheets and wheelchair-height voting screens. The accessibility tool focused mostly on wheelchair accessibility.

Feedback from stakeholders, including VEC's advisory group, is that VEC is committed to obtaining accessible voting centres.

Accessibility super centres

In response to an idea raised by the VEC electoral access advisory group, VEC piloted six accessibility super centres in the 2014 state election. These offered electronically assisted voting (EAV), translated voting instructions, hearing loops, sign language interpreters, communication boards for people who have difficulty speaking, and closed-circuit television systems that magnify text on a monitor. VEC promoted the six super centres through disability advocacy groups and advertised them throughout the wider community. The pilot was not independently evaluated.

VEC also worked with a disability advocacy and support organisation to develop Easy English voting guides and provided electoral information in a range of languages.

VEC employed 3 780 election staff across the state who spoke two or more languages. These staff wore stickers to identify the languages they spoke so that voters could easily seek assistance if required.

There is anecdotal feedback that interpreters were very well received, however, some interpreters felt they needed a better understanding of voting services to best assist voters. Figure 3B shows feedback from voters on EAV, communication and voting centre experience.

Figure 3B

Results of 2014 VEC voter satisfaction survey

|

Satisfaction—culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD), low-vision and overseas voters

Recommendations—voters with low or no vision

|

Note: Based on small sample sizes. CALD – 39, low or no vision – 6, not on the roll – 12, overseas – 67.

Source: Survey commissioned by the Victorian Electoral Commission.

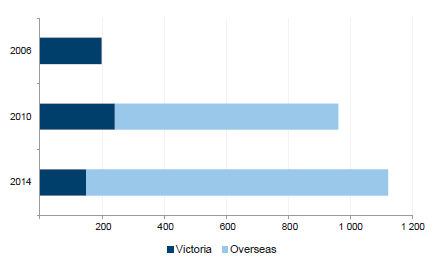

Electronically assisted voting

EAV has been available on a limited basis in Victoria since the 2006 state election. In the 2014 election, VEC implemented vVote, its modified EAV system for voters with motor impairment, voters with low or no vision, and voters with limited English proficiency, as well as overseas voters at the London early voting centre. vVote was available at 25 early voting centres—including the accessibility super centres—but not on election day. The system was not well utilised, with only 1 121 electronic votes processed. The vast majority of these—87 per cent—were cast overseas in London, as shown in Figure 3C. VEC made the decision to pare back the number of voting centres offering EAV between 2010 and 2014. VEC state that this was done to focus support and attention on those venues that were utilised in 2010. Many 2010 venues took no vVotes.

Figure 3C

Votes cast using vVote

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

A small survey of six voters who had low or no vision and 69 overseas voters showed that voters had high levels of trust in the vVote system but that the process was longer—particularly for voters who had low or no vision—and some voters found it confusing. Survey respondents were also keen to have vVote available in all voting centres in future elections, so they could vote on election day, or to be able to vote online, which is currently not permitted in the Electoral Act 2002. An internal project evaluation was completed, and a technical audit of voting verification completed on election night showed that the votes cast could be successfully verified.

Expanded use of vVote in its current form would pose challenges with infrastructure rollout and staff training as it requires that staff can communicate with people who have a range of distinct needs, and the technology itself requires lengthy training to ensure accurate use. VEC recommended to Parliament that legislation be amended to allow VEC to facilitate remote voting, with usage restricted to those currently eligible for EAV. In the event that these amendments are not made, VEC will need to determine whether to further refine vVote, provide an alternative EAV system or abandon EAV altogether. A robust evaluation will assist future decisions about accessible voting technologies.

3.4 Strategies to encourage full participation

VEC has election specific and ongoing projects and strategies designed to encourage electoral participation by groups who are generally disenfranchised or who find it difficult to vote, including people from CALD backgrounds, young people, Indigenous people, people with disabilities, and people experiencing homelessness. The audit reviewed programs aimed at election participation and VEC's ongoing engagement programs—with Horn of Africa communities, with schools, and with young Indigenous leaders. A number of these projects resulted in new enrolments and votes, as shown in Figure 3D. However, the success rate is variable, perhaps reflecting that some in these communities may not be familiar with democratic elections or concerned with voting.

3.4.1 Planning and evaluating participation strategies

It is difficult to assess the impact of VEC's engagement projects on voter participation, as the electoral roll does not contain indicators for the target groups—apart from the age of the voter. Recently, VEC has started flagging voters who have enrolled after attending VEC engagement activities, so that they can determine whether they also voted. Initial data provided by VEC is shown in Figure 3D.

Figure 3D

Electoral participation by attendees at VEC engagement programs 2014

|

Program |

Enrolled |

Voted |

Success rate |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Community Sector Information Kits |

313 |

182 |

58% |

|

Democracy Ambassador Program |

46 |

24 |

52% |

|

Homeless Engagement Program |

43 |

27 |

63% |

|

Disability Engagement Program |

68 |

59 |

87% |

|

Youth Engagement Program |

22 |

12 |

55% |

|

Indigenous Engagement Program |

9 |

5 |

56% |

|

Voting is for Everyone |

27 |

N/A |

N/A |

|

Total |

528 |

309 |

62% |

Note: 'Voted' data for participants in the 'Voting is for Everyone' program was not available, so enrolled participants have been excluded from the total success rate.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

Advisory committees

VEC has formed advisory groups to help it engage with people from CALD backgrounds, Indigenous people, people with disabilities, and homeless communities. The advisory groups help VEC obtain feedback and ideas about its services. The advisory group for people with disabilities is particularly active. However, due to staffing issues these groups have been managed inconsistently. Until recently, only two of the groups had terms of reference. VEC also had no set process for evaluating the groups. Newly created terms of reference for all groups include annual review and evaluation surveys.

VEC recently worked with its disability advisory group to review its disability action plan and has registered it with the Australian Human Rights Commission.

VEC's Indigenous engagement officer role has recently been filled after having been vacant since May 2014. The Indigenous advisory group has not met since 2011. The delay in filling this role and lack of input from the advisory group has limited the opportunities for VEC to effectively engage Indigenous communities in Victoria.

3.4.2 Civic participation programs

Voters from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds

Data collected by VEC indicates a correlation between levels of English language proficiency and informal voting rates. Voters from CALD backgrounds may also lack awareness about the electoral process, may be used to a different voting system, and may not be aware that they have both the freedom and requirement to vote in all elections.

In 2013, VEC piloted the 'Democracy Ambassadors' project in response to low levels of electoral participation by voters from CALD backgrounds. This project aims to train members of communities originally from Horn of Africa countries to become community educators, holding information sessions within their communities about voting and the electoral process. Following the initial pilot and review, VEC redesigned the project to focus on more established community leaders and longer training. This approach has been more effective, resulting in an increased number of facilitated information sessions in CALD communities. VEC is considering alternative strategies for future phases of this project.

Youth programs

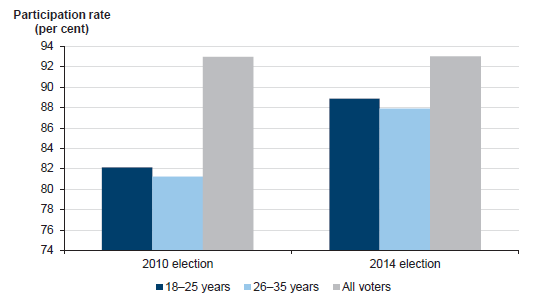

In the 2014 state election, just under 89 per cent of voters aged 18–25 voted, compared with 93 per cent of all Victorian voters.

The VEC's 'Passport to Democracy' program is a set of free lesson plans and resources available to school teachers, explaining the electoral process and encouraging participation. In 2014, 94 schools ordered the resources and 6 488 students participated in the program. VEC delivered 17 sessions about voting to schools. An internal review highlighted the lack of an overarching strategy to engage and educate young people who are disengaged.

A survey found 96 per cent of teachers believed that students were more likely to vote after completing the program, and 74 per cent of students said they were likely to vote if there was an election tomorrow. Another project, initiated at the 2014 state election targeting first-time voters—typically uninterested young voters—aimed to connect the issues they care about with the election. Over 1 200 young people participated, either by posting a question or voting for a question. However, only 42 candidates responded to questions, limiting the impact of the project. Despite the low response rate, surveyed participants reported they felt more positive about community engagement and were more aware of candidates and their policies.

VEC reviewed the participation of young Victorians in the 2010 and 2014 state elections. As Figure 3E shows, the participation rates have increased for both 18–25 and 26–35 year-old Victorians between the 2010 and 2014 elections.

Figure 3E

Youth participation rate in 2010 and 2014 state elections

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on Victorian Electoral Commission data.

Indigenous communities

Research commissioned by VEC showed a significant percentage of Indigenous Victorians have never enrolled to vote, while a high proportion of those enrolled have no intention of voting. VEC does not know the reasons for this, however, lower engagement may result from lower literacy levels, lack of awareness of voting requirements or distrust of the political process.

VEC partners with the Korin Gamadji Institute (KGI), which facilitates camps for Indigenous high-school-aged children. The camps focus on leadership, active participation, health and wellbeing, careers and cultural pride and include VEC-developed sessions about the importance of voting. In August 2015, KGI and VEC sent out a proposal for academic research on the effectiveness of the KGI program and partnership model. This research is due to be delivered by 30 June 2016.

The lack of an Indigenous engagement officer prevented VEC from conducting a thorough engagement program in Victorian Indigenous communities prior to the 2014 state election.

VEC has recently recruited an Indigenous engagement officer, which should lead to increased engagement with Indigenous communities in the future.

People with a disability

People with a disability may find it more difficult to vote due to physical or cognitive limitations. VEC is obligated under both state and federal legislation to provide accessible services for people who have a disability. Feedback from stakeholders agreed that VEC is strongly committed to engaging with and providing accessible services to people with a disability. VEC has also won awards for the accessibility features on its website and communication practices with people who have a disability.

VEC's strategies to make voting more accessible for voters with a disability are informed by their disability action plan, which has recently been reviewed and includes measures to assess VEC's future progress. VEC has committed to providing progress reports to its advisory group, as well as in its annual report.

VEC—with support from the Department of Health & Human Services—distributed a resource kit to all disability accommodation services shared group homes and offered education sessions. The kit included a DVD, an election planner and enrolment forms. The distribution was delayed, and kits arrived close to the election. Only two shared group homes participated in education sessions. A survey found concerns with the suitability of the resources for residents. Other feedback noted that while the resources were useful, planning should focus on time lines, setting a clear evaluation methodology and gathering input from stakeholders for future elections.

People experiencing homelessness

People experiencing homelessness may be particularly disenfranchised in the electoral process due to trust issues, lack of awareness of enrolment and voting processes, difficulties attending a voting centre, and a wide range of other concerns. During the 2014 election period, VEC continued its 'Homeless not Voteless' program, which involves enrolment outreach sessions at agencies that provide services to people experiencing, or at risk of, homelessness. During these sessions, 86 people completed enrolment forms. Mobile voting was also held at 20 locations, with 320 votes cast. Considering the significant daily challenges faced by people experiencing homelessness, this is a good result.

Most homelessness agencies surveyed said the sessions were well attended and that the response from their clients had been positive. Anecdotal feedback suggested VEC is more effective in engaging this community than electoral commissions in other Australian jurisdictions.

Other engagement projects

The 'Community Sector Information Kit' project was an awareness-raising initiative for the 2014 state election. VEC developed and distributed 2 209 kits with information about voting to community-based organisations and groups who face barriers to participation, particularly Indigenous, CALD, disability and youth community-based organisations.

Recommendation

- That the Victorian Electoral Commission evaluates its election accessibility and participation outcomes as a basis for developing an evidence-based strategy for the 2018 state election.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

Introduction

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report, or part of this report, was provided to the Victorian Electoral Commission.

The submissions and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

Responses were received as follows:

Victorian Electoral Commission

RESPONSE provided by the Electoral Commissioner, Victorian Electoral Commission

RESPONSE provided by the Electoral Commissioner, Victorian Electoral Commission – continued