Fraud Control Over Local Government Grants

Snapshot

Are fraud controls over local government grants well-designed and operating as intended?

Why this audit is important

In 2020–21, Victorian councils distributed more than $45 million in grants to individuals, businesses and community groups.

It is important that councils have effective controls for their grant programs to prevent fraud and give their communities confidence that public money is spent as intended.

Who and what we examined

We examined Hume City Council, Knox City Council, Loddon Shire Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council and West Wimmera Shire Council.

We looked at a selection of their grant programs from the last 5 years to see if their fraud controls are well-designed and consistently applied.

What we concluded

Councils' fraud controls for their grant programs are not always well designed and operating as intended. In some cases, they are missing.

Councils are not consistently identifying conflicts of interest, assessing applications against criteria, documenting their decisions, checking how funds are used or evaluating their grant programs' outcomes.

This unnecessarily increases the risk of fraud and makes it harder for the audited councils to show that their grant programs are transparent, equitable and benefit the community.

Our recommendations

We made 9 recommendations to all Victorian councils about strengthening their fraud controls and improving their guidance and training for grant related fraud.

We also made one recommendation to Loddon Shire Council about reviewing its community planning grant process.

Video presentation

Key facts

Note: *33 of 79 councils did not report their total grant spending in their 2020–21 annual reports.

Source: VAGO, based on information from councils.

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited councils and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. The councils’ full responses are in Appendix A. We have included a summary of each audited council’s performance in Appendix D.

Unless otherwise indicated, any individuals referred to in this report by name or position are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Importance of fraud controls

None of the audited councils have consistently applied fraud controls across all their grant programs. We found that these inconsistencies have unnecessarily exposed councils to a higher risk of fraud.

Figure A shows an example from Loddon Shire Council (Loddon) of how a lack of fraud controls over the life cycle of a grant program increased the risk of fraud.

Figure A: Lack of fraud controls for Loddon's community planning grant program

Under Loddon's community planning grant program, a councillor applied for $150,000 on behalf of a community asset committee in 2019. The grant was to upgrade a kitchen at a council facility to commercial standards.

The councillor chaired a community asset committee that manages a council facility on behalf of the council. The councillor, on behalf of the committee, estimated that the kitchen upgrade would cost $233,000 and requested $150,000 to complete the project.

The council staff member who assessed the application estimated that it would cost $20,000 to complete the project. Loddon advised us that it sought quotes during project planning, but the staff member who assessed the application did not attach or reference them.

The councillors, including the councillor that made the application, approved $20,000 for the project. But Loddon did not:

- exclude the councillor from the decision-making process

- review or comment on why the applicant requested $150,000 when the assessors estimated that $20,000 was an appropriate amount

- note that the requested amount was excessive in its report to the councillors.

Loddon's community planning grant program requires applicants to inform the local ward councillor of their application before they submit it. Otherwise, the council will consider it ineligible.

In this case, the local ward councillor and the applicant were the same person. While Loddon staff were aware of this, they did not consider how it could lead to a conflict of interest. For example, a local ward councillor could discourage other potential applicants from applying for a grant to reduce competition for their own application.

This process lacks transparency because Loddon does not require councillors to keep records of potential applicants that have approached them. Directly engaging with a potential applicant could also influence a councillor's decision to approve their application or not.

|

In this example … |

Which means … |

|

the council allowed the councillor to approve their own application without declaring or managing the conflict of interest |

the councillor could be voting to approve funding for a project that may personally benefit them. |

|

there were no assessment criteria to assess the applications |

|

|

the council did not clearly document how it determined the grant amount |

there is no transparency on why the council chose this amount. |

|

2 of 5 councillors at Loddon, including the councillor who applied for the grant, had not completed fraud training |

they might lack an understanding of how to prevent, detect and respond to fraud risks. |

As this case study shows, the following controls are important to help councils reduce the risk of fraud and ensure their grant programs are transparent, fair and benefit the community:

- declaring and managing conflicts of interest

- assessing applications against eligibility and assessment criteria

- not having councillors on assessment panels

- documenting funding decisions

- acquitting spending

- evaluating their overall benefits.

Inconsistently declaring conflicts of interest

All of the audited councils require their staff to declare conflicts of interest. However, none of them have an overarching grant policy that outlines how staff and councillors should declare them for all their grant programs.

Hume City Council (Hume) has a process for relevant staff to declare conflicts of interest for one program that delivers individual grants up to $2,000. However, it did not apply this process to another program that provided grants up to $250,000 between 2014 and 2020.

Only Loddon and Southern Grampians Shire Council (Southern Grampians), which has only one grant program, have processes for all their staff who assess applications to declare conflicts of interest within their grant management systems.

Lack of eligibility and assessment criteria

Loddon and West Wimmera Shire Council (West Wimmera) do not use eligibility or assessment criteria to assess applications for all their grant programs. This makes it unclear how these councils decide who is eligible for their programs or why they approve some applications over others.

Two of West Wimmera's 4 grant programs do not have eligibility criteria. These programs, which provide sponsorships and donations, require applicants to approach the council directly to request funding instead of making a formal application. In 2020–21, West Wimmera spent $51,559, or 58 per cent of the $89,409 it spent on grants, on sponsorships and donations with no eligibility criteria.

Assessors are council staff members who assess grant applications.

An assessment panel typically has multiple assessors and a chairperson. A panel assesses grant applications and makes recommendations to the council about which applications should receive funding.

For Loddon’s community planning grant program, assessors only record brief overall comments for each application and there is no evidence that they use assessment criteria. This makes it unclear if they assess all applicants against the same standard.

Loddon also distributes unallocated funds from one of its grant programs without assessing applicants against criteria. This reduces transparency over how it selects recipients and creates a risk that it is not maximising community benefits.

Councillors assessing grant applications

Councillors at Hume and Knox City Council (Knox) sit on assessment panels for some grant programs. This is an issue because these councillors are involved in both assessing and approving grant applications. For example, at Knox, a councillor assessed a grant application and later voted to approve it.

Both councils told us they will recommend that councillors do not form part of assessment panels. Knox advised us that its newly developed overarching grant policy will address this, which it will present to councillors in mid 2022.

Not documenting funding decisions

Assessors at Hume, Knox and Loddon changed their initial recommendations without documenting any reasons in their grant management systems. From these councils' records, it is not clear why they awarded:

- grants to some applicants who assessors did not initially recommend for funding

- a higher grant amount than assessors initially recommended.

For example, at Hume, the assessment panel chair changed an applicant’s score and increased the grant amount from $8,750 to $10,000, but there are no records to explain this change.

At Knox, one applicant received $20,000 in 2017 even though Knox's records show that none of the 4 assessors recommended awarding them the grant when they individually assessed applications. Knox advised us that after completing individual assessments, assessors met as an assessment panel and decided to recommend the application. However, Knox did not document reasons for changing its recommendation.

Knox advised us that it has recently changed its process to better document these types of changes. It also plans to include these notes in its grant management system.

Not communicating outcomes to applicants

Only Loddon, Warrnambool City Council (Warrnambool) and West Wimmera consistently tell unsuccessful applicants why they have rejected their applications.

The other 3 audited councils do not consistently do this, which reduces the transparency of their grant programs.

Inconsistently applying acquittal processes

Councils can check if recipients have used grant funds as intended by asking them to provide evidence of their spending, such as receipts or photos of a completed project. This is called an acquittal process.

Without an acquittal process, councils cannot be sure that recipients have met a program’s conditions and used the funding to benefit the community. It also may be difficult for councils to identify any unspent funding to recover.

While all audited councils use an acquittal process in some of their grant programs, only Knox acquits all of them. Southern Grampians uses an acquittal process for the only grant program it has. In line with better practice, Knox also monitors recipients' spending throughout the funding period for its largest grant program.

Inconsistently documenting acquittal processes

In addition, only Knox could give us complete documentation to show that it acquits grants consistently. This is because the other councils do not follow a consistent process or always keep supporting documentation.

Unlike the other audited councils, West Wimmera does not have a grant management system. Instead, it stores documentation in its records management system. As this system is not designed for managing grants, the council could not confirm if the gaps we found were due to the system’s poor search functionality or missing records.

Not regularly evaluating grant programs

Councils cannot make informed decisions on how to best allocate their funding if they do not regularly evaluate their grant programs. None of the audited councils have a standard practice or requirement to assess if their programs benefit the community.

For example, Loddon annually allocates $50,000 to each of its wards for its community planning grant program. It also rotates $500,000 a year across its wards for significant community projects. However, it has not evaluated if dividing funding between wards maximises community benefits.

We also found examples at Warrnambool where the council has paid recurring grants for over 15 years without reviewing them. However, it stopped paying 3 non competitive recurring grants after finding out that they were not benefitting the community or lacked relevant approvals.

Recommendations about improving fraud controls

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| All Victorian councils Loddon Shire Council |

1. improve their conflict-of-interest processes by:

|

Accepted by: Knox City Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, West Wimmera Shire Council Partially accepted by: Hume City Council, Loddon Shire Council |

|

2. develop eligibility and assessment criteria for all their grant programs and:

|

Accepted by: Knox City Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council |

|

|

3. exclude councillors from assessing and making recommendations on grant applications (see Section 2.2) |

Accepted by: Hume City Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, West Wimmera Shire Council |

|

|

4. verify that all grant recipients use grant funds for their intended purpose (see Section 2.3) |

Accepted by: Hume City Council, Knox City Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, West Wimmera Shire Council |

|

|

5. evaluate the benefits of:

|

Accepted by: Hume City Council, Knox City Council, Warrnambool City Council |

|

|

6. document all funding decisions in a consistent and structured way within a centralised system to ensure their decision making is transparent, including by recording:

|

Accepted by: Hume City Council, Knox City Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, West Wimmera Shire Council |

|

|

7. assesses the benefits of its ward-based approach to allocating grants and how this aligns with the council's strategy (see Section 2.2). |

Partially accepted by: Loddon Shire Council |

Internal guidance and training

Councils should provide guidance to staff and councillors who administer grants, including:

- an overarching grant policy

- fraud control frameworks

- fraud training.

Lack of overarching grant policies

Only West Wimmera has an overarching grant policy that documents how its staff and councillors should run grant programs.

This means that at other councils, staff and councillors do not have centralised guidance on which fraud controls they need to implement and when. Due to this, these councils have applied fraud controls in some grant programs but not others.

Hume, Knox and Loddon are currently developing draft overarching grant policies. They intend to adopt their policies in mid-2022.

Gaps in fraud control frameworks

All audited councils have risk management plans and fraud and corruption policies. However, councils do not prioritise grant-related fraud as a key risk. For example:

- none of the audited councils’ risk management plans and fraud and corruption policies cover fraud controls for grant programs

- Loddon’s fraud control framework does not clearly define roles and responsibilities for managing and reporting fraud

- of the 4 councils that have risk registers (Hume, Knox, Loddon and West Wimmera), none list grant-related fraud as a risk.

Gaps in fraud training

While all audited councils provide fraud training, none ensure that all staff and councillors involved in administering grants have completed it. In addition, only Knox, Loddon and Southern Grampians provide this training to councillors.

We assessed what the audited councils’ fraud training covers and found that:

- none cover fraud risks that are specific to grants

- Southern Grampians refers to a superseded version of the Local Government Act 2020.

Without adequate training, councils are not proactively ensuring that staff and councillors understand their responsibilities in managing fraud risks.

Recommendations about improving guidance and training

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| All Victorian councils | 8. develop their own overarching grant policy that details:

|

Accepted by: Hume City Council, Knox City Council, Loddon Shire Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, West Wimmera Shire Council |

|

9. include grant-related fraud risks in their risk management and fraud and corruption plans and assign responsibility for managing these risks (see Section 2.4) |

Accepted by: Hume City Council, Knox City Council, Loddon Shire Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, West Wimmera Shire Council |

|

|

10. develop mandatory training for staff and councillors that covers:

|

Accepted by: Hume City Council, Knox City Council, Southern Grampians Shire Council, Warrnambool City Council, West Wimmera Shire Council |

1. Audit context

The law requires, and communities expect, councils to deliver grant programs with integrity and accountability.

A person or entity that fraudulently gets an unjust advantage over other applicants undermines the fairness of a grant program. Fraud controls help councils prevent, detect and respond to fraud-related risks.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 What is fraud?

Fraud occurs when a person or entity uses dishonest or deceitful means to get an unjust advantage over another person or entity. Within the public sector, fraud can also involve corruption.

Victoria's Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission Act 2011 defines corrupt conduct:

|

Of a public officer or public body as ... |

For any person as ... |

|

|

1.2 Local government grants

Councils can use grant programs to help them:

- meet an existing community need

- provide a service that aligns with the council's goals

- stimulate the local economy.

To do this, they distribute grants to individuals, community groups and businesses.

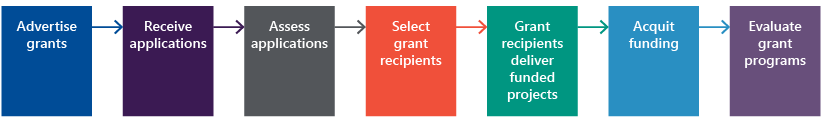

Figure 1A shows the stages that should be involved in council grant programs.

FIGURE 1A: Stages that should be involved in council grant programs

Source: VAGO.

In 2020–21, 46 Victorian councils spent more than $45 million on grants. The remaining 33 councils did not report their total grant spending in their annual reports. Figure 1B shows that the audited councils spent around $4.11 million in grants in 2020–21.

FIGURE 1B: Audited councils’ grant spending in 2020–21

| Council | Grant spending per capita | Total grant spending |

|---|---|---|

| Hume | $7.70 | $1,902,285 |

| Knox | $6.10 | $1,017,141 |

| Loddon | $75.11 | $560,756 |

| Southern Grampians | $9.62 | $154,640 |

| Warrnambool | $10.84 | $388,237 |

| West Wimmera | $23.47 | $89,409 |

| Total | $4,112,468 |

Source: VAGO, based on information from the audited councils, the Australian Bureau of Statistics, and the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning's projected population growth rates.

1.3 Fraud and local government grants

To award a grant, a council needs to transfer funding to a third party. This carries a number of fraud risks, including the risk of:

- staff or councillors selecting recipients unfairly based on personal interests

- an applicant giving staff or councillors benefits for awarding them a grant

- a recipient using funding for purposes outside the grant's objective.

Fraud controls

Victorian state departments are bound by the 2018 Better Grants by Design guide for administering grants.

|

Better Grants by Design recommends… |

To ensure that… |

|

having processes for staff to declare conflicts of interest |

conflicts are identified, managed and do not influence decision-making. |

|

using clear and easy to understand eligibility criteria to select and assess applications |

they fairly assess every application the same way. |

|

documenting and communicating their decisions |

their decision-making is transparent. |

|

acquitting spending |

|

However, there is no official guidance or better-practice document for Victorian councils on what fraud controls they should use in their grant programs, such as managing conflicts of interest, using assessment criteria and documenting decision making.

Managing conflicts of interest

In the public sector, a conflict of interest occurs when an employee has private interests that could influence, or be seen to influence, their decisions or how they perform their public duties. A conflict of interest can be actual, potential or perceived.

For example, in its 2018 investigation Protecting Integrity: West Wimmera Shire Council examination, the Local Government Inspectorate found that West Wimmera’s communications officer engaged with prospective applicants and assisted them with their applications. As the officer was also involved in assessing applications, this created a conflict of interest.

In 2019, the Independent Broad-based Anti-corruption Commission’s Managing corruption risks associated with conflicts of interest in the Victorian public sector report described good-practice examples of some councils managing conflicts of interest. This included having a standalone conflict of interest policy and maintaining registers for declarations.

However, the report found that other councils it reviewed relied on general guidance provided by Local Government Victoria or codes of conduct that did not clearly outline how staff should declare and manage conflicts of interest.

If a council does not identify or manage conflicts of interest between grant applicants and assessors, it increases the risk of fraud.

Using assessment criteria and documenting decision-making

Councils must assess grant applications against eligibility and assessment criteria and record their decision making process to make sure their funding decisions are transparent.

For example, the Local Government Inspectorate's 2019 Protecting integrity: Yarriambiack Shire Council Investigation report highlighted that the council's lack of record keeping and separation of duties in its decision-making process undermined the transparency around its community grants.

In particular, the investigation found that the council:

- did not have criteria to decide who would be on the assessment panel

- could not explain why councillors were on the assessment panel, which are operational roles within the council

- did not document why assessors approved or declined applications.

Similarly, in 2014, the Local Government Inspectorate found that councillor discretionary funding programs at the City of Greater Geelong had limited oversight and accountability. This was because councillors could allocate funding to projects within their own wards without:

- formally advertising or publicly promoting funding programs

- a formal process for prospective applicants to apply

- documenting how they selected projects and against what criteria

- requiring any feasibility studies or business cases for proposed projects

- considering how the council would pay to maintain new assets.

2. Implementing fraud controls

Conclusion

Councils do not always follow processes for staff or councillors to declare conflicts of interest, use eligibility criteria to select recipients, document decision-making or evaluate the outcomes of their grant programs. This means that they are not consistently using fraud controls when delivering grants, which undermines the transparency and fairness of their programs.

Councils’ guidance to staff and councillors who administer grants is insufficient.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Conflicts of interest

If a councillor or staff member with a conflict of interest is involved in assessing or approving a grant application, they could use their position to benefit themselves or someone they know, such as a family member or friend.

Not identifying potential conflicts of interest

None of the audited councils have reviewed their grant records to detect potential fraud. Analysing grant records to see if staff or councillors have connections to past recipients can also help councils identify present conflicts of interest.

While connections do not always indicate fraudulent behaviour, councils should oversee these relationships.

Figures 2A and 2B present examples of councils approving applications made by staff or councillors without acknowledging potential conflicts of interest.

FIGURE 2A: Loddon: family members applying for grants

Loddon distributes grants to community groups for promoting local events. In 2021, a councillor's family member applied for a $400 grant as a representative of a community group.

The family member used the councillor's account in Loddon’s grant application portal to apply for the grant, which meant the application was lodged under the councillor's name. The councillor is not involved with the community group.

A Loddon staff member approved the application because it met the eligibility criteria. However, it is unclear if they knew the councillor was not involved with the community group. We found no evidence in council records that the staff member considered this.

FIGURE 2B: Hume: staff applying for grants

In 2018, Hume ran a grant program to sponsor local events.

Applications were due in October 2018 with budgets to be finalised in June 2019. In August 2019, 10 months after applications were due, a council staff member made a late application for $16,500 on behalf of a community group for a street festival. Hume allowed the applicant to submit a late application and approved it.

Hume was unable to locate evidence for this approval because it processed the application outside its grant management system.

Lack of policies on how staff should declare conflicts of interest

All audited councils have general requirements for staff to declare conflicts of interest when they occur. However, none have an overarching grant policy that specifically outlines how staff should declare conflicts for grants. Without this, staff may not know how to declare and manage conflicts in this context.

Figure 2C presents better-practice examples of how Hume, Loddon and Southern Grampians identify conflicts of interests.

FIGURE 2C: Hume, Loddon and Southern Grampians: declaring conflicts of interest

Hume, Loddon and Southern Grampians use different better practice approaches to identify conflicts of interest for staff assessing grants.

Hume

For its economic development grant program, Hume requires both applicants and assessors to separately declare conflicts of interest.

Hume’s grant application form asks if the applicant or their family members have any relationships with a council staff member. In addition, councillors and staff involved in the program must declare any relationships with applicants.

Loddon and Southern Grampians

Southern Grampians has a mandatory field in its grant management system for assessors to declare if they have a conflict of interest for every application in its grant program. Loddon also has this field for all its staff who assess grant applications.

Hume's 2-step process for declaring conflicts of interest reduces the risk of conflicts going undetected. While this program is an example of better practice, it is unclear why Hume does not consistently apply it to all of its grant programs.

Southern Grampians' approach ensures that assessors report and document any conflicts of interest consistently.

Inconsistently managing conflicts of interest

As the audited councils do not have consistent processes for staff and applicants to declare conflicts of interest, it is unclear if they are managing them well.

Figure 2D presents an example of better practice from West Wimmera. The council excludes staff and councillors that have declared a conflict of interest from the decision making process. This way, the council does not provide some applicants with an unfair advantage over others.

FIGURE 2D: West Wimmera: managing conflicts of interest

In May 2021, West Wimmera excluded a councillor and staff member from the decision making process for one of its grant programs because they declared conflicts of interest.

The councillor was a life member of a group that applied for a grant. The staff member managed a council asset at a local club that also applied for the grant.

The council's records show that the councillor left the room while the rest of the council voted to approve the application. The staff member did not take part in assessing the application.

West Wimmera documented details of each conflict of interest and the outcomes in its conflict of interest register.

2.2 Distributing grants fairly

To make sure grant programs are fair and accessible, councils should:

- set eligibility and assessment criteria and use them consistently

- document their funding decisions

- not have councillors on assessment panels

- communicate outcomes to all applicants

- regularly evaluate if their grant programs are providing community benefits

- publicly advertise their grant programs.

Using eligibility and assessment criteria inconsistently

When grant programs do not have clear eligibility and assessment criteria, councils may assess applications inconsistently and the public might think the outcomes are unfair.

All of the audited councils, except Loddon and West Wimmera, had eligibility criteria for all of the grant programs we reviewed.

Lack of assessment criteria for Loddon’s community planning grant program

Loddon's community planning grant program annually budgets $50,000 for each ward to use on projects proposed by community planning groups. While council staff do assess applications before councillors vote to approve them, there is no evidence that they use assessment criteria. Instead, the council documents its overall comments for each application.

Figure 2E outlines an example where Loddon staff did not use assessment criteria for this program. This makes it difficult to understand why the assessors changed their recommendation.

FIGURE 2E: Loddon: assessments do not reflect recommendations

In May 2019, a local club applied for a $16,390 grant to install a disabled toilet.

The council's assessment of this application states: ‘Good project. This has been fully designed and planned and is ready to proceed. Recommend funding for full amount’.

However, Loddon's September 2019 report to its councillors did not recommend the project because it was for a specific club operation. In line with the report's recommendations, the councillors did not approve the project for funding.

The council's letter to the applicant says that it declined the project because it was better suited for another grant program.

While it was reasonable for the council to decline the project, Loddon's records do not explain why the council's initial assessment was different to its final recommendation to the councillors. Having assessment criteria would have helped Loddon document why it did not select the project.

Loddon’s ward based approach may not be delivering the best value for money for the municipality because it allocates funding based on wards. Even when the council does not approve any projects from a ward one year, the budget rolls over for the same ward to use in future years.

Loddon also provides $500,000 per year to support its community planning framework. It funds a single project that strategically benefits the community and is intended to attract state and federal grant funding by providing a co-contribution. The council rotates the funding between wards and there is no competitive process to select projects. The council also delivers the project.

By using both of these programs to fund primarily capital projects, Loddon is not assessing these projects against competing projects that go through its annual budgeting process.

Loddon advised us that while it manages capital bids through its annual budget process, a lack of staff has impacted its ability to develop a project pipeline to help it develop and prioritise capital projects.

Lack of eligibility criteria in ad hoc grant programs

Both Loddon and West Wimmera have ad hoc grant programs that do not use eligibility criteria or an open competitive process. Figures 2F and 2G show that these grant programs are less transparent to the public because they rely on assessors’ individual discretion, rather than a formal assessment process, to select recipients.

FIGURE 2F: Loddon: grants awarded without assessment

Councillors at Loddon distribute unallocated funds from its competitive community grant program without advertising that they are available and documenting the eligibility or assessment criteria.

In 2020 and 2021, Loddon did not open additional competitive rounds to distribute more than $16,000 of un-allocated community grant funds. This is inequitable because some community groups have access to funds while others need to show how they will use them to benefit the community through a competitive process.

For example, in March 2021, the councillors voted to pay a community group almost $7,000 in un-allocated funds from the community grant program. The recipient did not submit an application for council staff to assess.

In another example, a community group approached a councillor to ask for funding because it missed the community grant round. The councillor consulted a council officer to confirm that this group would have met eligibility criteria, but there was no formal application or assessment process. The councillor took this request to the council in June 2021 and the council approved the group's request for $1,980.

If the applicant had applied through the council's community grant program, it would have had to detail what the funds would be used for and been scored against other applicants using the assessment criteria.

FIGURE 2G: West Wimmera: lack of eligibility criteria

In 2020–21, West Wimmera gave out 57.6 per cent of all its grant funding in programs without eligibility criteria.

In 2020–21, West Wimmera delivered 4 grant programs, but only 3 had eligibility criteria. For the remaining program, applicants approached the council directly to request funding. This is because these programs are sponsorships and donations, which have a different process than grant programs. However, it is still unclear how the council selected recipients for these programs.

West Wimmera also told us that it did not have eligibility criteria because these grants are designed to give the council flexibility to respond to small funding requests that are not eligible for the council's other grant programs.

In 2020–21, West Wimmera spent $51,559, or 57.6 per cent of its total grant spending of $89,409, on this ad hoc funding. The funding included contributions to local businesses to start or continue operating in the council area, small payments to tourism companies and sponsorships of local events.

Not documenting funding decisions

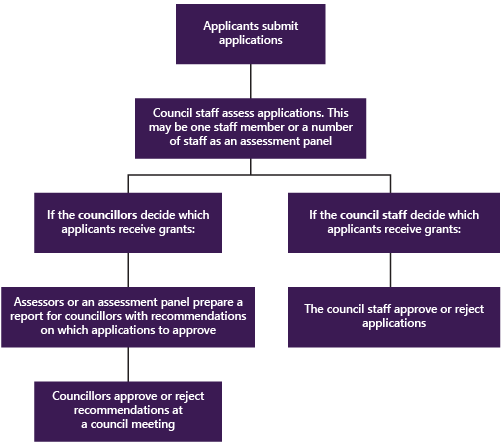

Figure 2H outlines 2 different processes to select grant recipients depending on whether councillors or council staff approve applications.

FIGURE 2H: Processes to select recipients for grant programs

Source: VAGO.

Hume and Loddon have no internal guidance on when grant programs should have an assessment panel. It is not clear why these councils use one assessor to assess some grants and a panel to assess others.

Figure 2I describes examples from Hume, Knox and Loddon where assessment panels initially recommended funding less than the requested amount, or not funding an applicant at all, then changed their recommendations without recording why. Before this audit, none of these councils had standard practices to document when and why the assessors changed their recommendations.

FIGURE 2I: Hume, Knox and Loddon: not documenting funding decisions

Based on their grant records, Hume, Knox and Loddon have approved more funding for recipients than what assessors initially decided. This is because these councils do not record changes in assessors' recommendations.

For example, at Knox, a single applicant received $20,000 when none of the 4 assessors recommended awarding the grant to them when they individually assessed applications. We also found that one applicant received the full $14,200 they requested, even though 3 of the 4 assessors recommended they receive less than $5,000.

Knox advised us that in both instances, the assessors discussed the applications as an assessment panel after completing their individual assessments and agreed to change their recommendations. However, Knox did not document reasons for doing so. Knox told us that it has since updated its processes to record more details about assessors' decisions.

In another instance, Hume's assessment panel chair changed an applicant’s score and increased the grant amount by $1,250. Hume advised us that the assessment panel increased the amount at a second meeting but did not document why.

We also found 3 instances at Hume where councillors approved grants despite the applicants not meeting the assessment criteria.

Loddon does not always document its funding decisions in its grant management system. For example, councillors approved one application that assessors did not initially recommend funding without documenting that the assessors changed their recommendation. Loddon also did not document in its system why it awarded 2 grant applicants more than $33,000 when they only requested $25,000.

Councillors on assessment panels

The Local Government Inspectorate's 2019 Protecting integrity: Yarriambiack Shire Council Investigation report recommended the council to remove councillors from assessment processes for community grants.

At Hume and Knox, councillors sit on assessment panels for some grant programs and then approve grants they have recommended at council meetings. For example, in August 2020, a Knox councillor assessed a grant application for $8,891. In September, the same councillor voted to approve the application.

Hume and Knox told us that they will recommend that councillors do not form part of assessment panels in mid-2022. Both councils advised us that their new overarching grant policy will address this, which they will present to councillors after this report is released.

For some grant programs at Loddon and West Wimmera, councillors assess and approve applications in council meetings without council officers formally assessing them (see figures 2F and 2G).

Lack of transparency in communicating outcomes to applicants

Informing applicants about the outcome of their application can help to ensure that councils have valid reasons for their decisions. It also gives the applicant transparency on why the council selected other applicants.

However, only Loddon, Warrnambool and West Wimmera consistently send letters to applicants that explain why they were unsuccessful.

While Knox does inform applicants and provides reasons why they were unsuccessful, we found 3 grant applications where this did not occur. Other audited councils do not consistently tell unsuccessful applicants why they rejected their application. This can reduce the transparency of their grant programs.

Not regularly evaluating grant programs

Regularly evaluating grant programs can help councils identify programs that are not delivering community benefits and redirect the funds to worthier recipients.

None of the audited councils have a standard practice or requirement to evaluate their grant programs. While all audited councils except West Wimmera have evaluated at least one of their grant programs in the past, this has occurred on an ad hoc basis.

Figure 2J discusses how Warrnambool continued to pay recurring grants without knowing if they were achieving their intended benefits or were fit for purpose.

FIGURE 2J: Warrnambool: funding recurring grants without review

While Warrnambool has evaluated if some of its recurring grants provide community benefits, it has continued to fund some grants for up to 25 years without reviewing them.

Warrnambool has provided:

- $5,000 each year to the coast guard to cover petrol costs since 1997

- $15,000 each year to a surf lifesaving club for at least 15 years.

Warrnambool has not adjusted the value of these grants even though:

- the price of fuel has risen more than 1661 per cent in the last 20 years

- it has not reviewed what equipment and maintenance costs the council provides to the surf lifesaving club and if these costs are greater than they were 15 years ago

- the coast guard has requested additional funds from the council.

The council stopped automatically paying the following 2 non competitive recurring grants because it found that they were not benefitting the community or it could not find evidence from when it approved them:

- The council paid a committee of management (CoM) $11,000 a year from 2006 to 2020 to maintain an athletics park. The athletics track has degraded and is currently not safe for schools and other community groups to use. In November 2020, council staff told the park's CoM that the council would not make any future payments. The CoM sent an invoice in late 2021, which the council has not paid.

- The council had been paying a sporting organisation $10,000 per year since 2006 but had no evidence that it had approved the grant. In 2020–21, staff ceased the organisation’s annual payments and recommended that it apply for budget funding.

Note: 1This percentage was calculated based on the nominal price increase of fuel from 1999 to 3 May 2022.

Gaps in advertising grant programs to potential recipients

When distributing public funds, councils should ensure that they give all potential recipients the same opportunity to apply for a grant. Councils risk not treating all potential recipients fairly if they do not do this. While there are valid reasons for not advertising grant programs, it is important that councils document these reasons for transparency.

At Loddon and West Wimmera, gaps in advertising their grant programs mean that they cannot be sure that all potential recipients can access information about the programs they are eligible for.

|

For example ... |

But ... |

|

Loddon advertises its grant programs on its website |

it spreads information about its grant programs across different policies and webpages. |

|

Loddon's Community Support Policy mentions that the council may consider granting sponsorships and donations |

does not include information on how a potential recipient can apply. |

|

West Wimmera advertises its formal grant programs on its website |

does not advertise programs that it categorises as sponsorships or donations. |

2.3 Checking how funds are used

Councils should use acquittal and monitoring processes to make sure grant recipients use funds as intended. This can help them recover leftover or misspent funding. Councils should apply acquittal processes that are proportionate to the value of the grant.

Inconsistent acquittal processes

The audited councils do not consistently check if recipients use funding as intended. Only Knox and Southern Grampians have an acquittal process for all of their grant programs. The remaining councils do not require recipients to provide evidence of how they have used funding for at least one program.

Not consistently using an acquittal process means that councils cannot:

- be sure if grant recipients have used funds as intended

- be sure if recipients have met a grant’s conditions

- recover any unspent funds.

Figure 2K provides an example where Loddon paid a larger grant than it should have because it did not check how the recipient used the funding.

FIGURE 2K: Loddon: selling an oval mower against grant policy

Loddon runs a grant program to help major recreation reserve CoMs replace their oval mowers.

Under the program's policy:

- eligible CoMs can receive support of up to $35,000

- CoMs must give the council proof of the net cost of the new mower, accounting for any trade-in value of the old mower.

In August 2021, a CoM requested, and the council approved, a $35,000 grant to purchase a new mower. Under the program's policy, the group should have supplemented the grant funding with funds from the sale of its old mower.

The CoM privately sold its old mower 2 months after purchasing the new mower, despite advising the council that the old mower had no trade-in value. The CoM kept the $7,700 it received for the old mower after it made an agreement with the school that co-owned it.

Loddon was not aware of the sale because it had not acquitted the funding. While the CoM later informed Loddon about the sale, the council has no plans to recover this funding even though it should not have paid the full cost of the new mower.

In the conditions for its largest grant program, West Wimmera outlines its right to withhold 20 per cent of funding until recipients acquit their spending. This creates a financial incentive for recipients to show how they used the funding. However, West Wimmera does not have evidence that it does this in practice.

While West Wimmera specifies this process in funding agreements, it does not formalise it in its overarching grant policy. By not doing this, the council does not require staff to consistently apply this practice across its grant programs.

Not monitoring how recipients are using funds

None of the audited councils consistently monitor how grant recipients are using funding. Instead, they rely on acquittal processes at the end of a program. Ongoing monitoring could help councils detect potential fraud at an earlier stage.

From the grant programs we sampled, only Knox has an ongoing monitoring process, which Figure 2L describes. While this is an example of better practice, it only applies this to its largest grant program.

FIGURE 2L: Knox: monitoring process for its community partnership funding grants

Knox requires recipients of its community partnership funding grants, which support organisations that have ongoing operational costs to deliver community services and activities, to report how they have used the funding each year.

The program's 4-year funding agreements require recipients to provide Knox with an annual outcomes report for each funded activity that includes supporting documentation. This helps Knox ensure that recipients are using the funds as intended.

This monitoring has helped Knox identify areas for improvement in its performance measures. For example, an organisation reported that it would not be able to meet its original performance measures due to the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic. In response, Knox changed its performance measures so the organisation could still meet them and acquit its spending.

Lack of processes to recover funding

It can be difficult for councils to recover funding from recipients who have not met a program’s conditions, such as not delivering a funded activity. Only Hume and Knox have clauses in their funding agreements that allow them to stop or recover payments.

Having these terms in their funding agreements has enabled Hume and Knox to recover funding. For example, in June 2021, Knox recovered around $20,000 from a community group after a funded event could not go ahead due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Gaps in record keeping

Councils should have a structured way to document information about their grant programs to ensure that their decision-making is transparent throughout a program’s life cycle. One way that councils can do this is by using a grant management system to document:

- how the council assessed applications, including the names of the assessors

- any conflicts of interest with individual applicants

- correspondence with applicants and recipients

- supporting documentation from recipients to acquit spending.

All audited councils except West Wimmera use a centralised grant management system to manage their grant processes.

However, we found that all audited councils except Knox had incomplete records, such as missing acquittal forms and receipts, for the programs we reviewed. This is because these councils administer some grant programs outside of their grant management system. For example:

|

Currently … |

But … |

|

Hume does not process all grants through its grant management system |

it plans to move all grants into the system by the end of 2022. |

|

Loddon administers all of its grants in the grant management system it implemented in 2019 |

some of the grant programs we reviewed from 2019 were administered outside the system in the early stages of its implementation. |

|

Southern Grampians uses assessment panels to review applications, but only records one assessor's name per application in its grant management system |

it plans to update its system to include the names of all assessors for its 2022 grant rounds. |

West Wimmera uses its records management system to store documents that relate to its grant programs. However, the system's poor search functionality and lack of structure to organise documents makes it difficult for staff to find grant records. West Wimmera:

- did not record the assessors’ names for 2 applications in 2017 and 2 in 2019

- could not find 2 letters of success sent to applicants in 2019

- could not provide assessment documents from 2018 when requested, but found them after some investigation.

West Wimmera is seeking funding in its next budget cycle for a grant management system that it expects will address these issues.

2.4 Frameworks to manage fraud risks

Councils can provide staff and councillors with guidance on how to manage fraud risks by:

- implementing an overarching grant policy to make sure staff apply fraud controls throughout a grant’s life cycle

- documenting fraud risks in risk registers and defining roles and responsibilities for managing these risks

- training staff and councillors to detect and prevent fraud.

Lack of overarching grant policies

An overarching grant policy promotes consistency in how staff manage a council’s grant programs. It should:

- cover the entire life cycle of a council’s programs from advertising to acquittal

- set standards to prevent and manage fraud risks

- follow relevant legislation, policies and guidance

- be accessible to staff who are involved in administering grants.

However, 5 of the 6 audited councils do not have an overarching grant policy.

West Wimmera is the only audited council that has an overarching policy. This policy covers some key aspects, including:

- its definition of a grant

- an explanation of how past recipients who have not acquitted spending are ineligible for future grants

- its application, assessment and accountability processes.

However, its policy lacks some key elements, such as how to acquit spending and manage conflicts of interest for grant programs.

Hume, Knox and Loddon have developed draft overarching grant policies. Hume and Knox expect to adopt their policies in mid-2022. Both councils advised us that this timing will allow them to consider our report's recommendations in their new policies.

Hume and Knox's policies include better-practice fraud controls:

|

The draft policy at … |

Outlines how it will manage grants over their life cycle, including … |

|

Hume |

|

|

Knox |

|

Loddon's draft policy lacks guidance on how staff should manage grants at each stage of their life cycle, including assessment, acquittal and conflict of interest processes. Loddon told us that this policy is a work in progress.

Documenting fraud risks

Incomplete and missing risk registers

Risk registers can help councils evaluate the impact of risks and identify actions to address them.

Hume, Knox, Loddon and West Wimmera have risk registers, but they do not list grant related fraud as a risk. This is a missed opportunity to reduce these risks and identify areas for improvement within their fraud controls.

Both Hume and West Wimmera told us that they are currently reviewing their risk registers to include grant related fraud as a risk. Hume expects to complete its review at the end of 2022. West Wimmera plans to include controls around declaring conflicts of interest and selecting assessment panels.

Defining roles and responsibilities

Councils should have clearly defined roles and responsibilities for managing fraud related risks. Without doing this, they may not be prioritising these risks.

Except for Loddon, all of the audited councils clearly define roles and responsibilities for managing and reporting fraud in their general fraud and corruption policies.

all of the audited councils have policies for fraud and corruption, none of these policies cover fraud controls for grant programs.

Lack of training about grant-related fraud risks

Without training, staff and councillors involved in administering grants may not know how to prevent and detect fraud.

All audited councils deliver fraud training, but attendance records show that none have ensured that all staff have completed it.

In 2020, councillors at the audited councils approved around $2.6 million in grants. However, only Knox, Loddon and Southern Grampians deliver fraud training to their councillors. Other councils rely on councillors to act with integrity, which is required under councillor codes of conduct.

Figure 2M is an example that shows why councils should ensure they train staff and councillors on the risks of both perceived and actual conflicts of interest.

FIGURE 2M: Loddon: councillor-sponsored prize

A Loddon councillor sponsors a $14,500 prize at an event that a local club runs every year. The prize is named after them and their family.

In 2021, the club applied for and received a $1,000 grant from the council to promote the entire event.

While the councillor did not approve the grant, it can be perceived as a conflict of interest. This is because the council is providing public funding to promote an event that a councillor personally contributes to. While the event was eligible for funding, council records show that Loddon did not consider how the application could present a conflict of interest.

As of December 2021, 2 of Loddon's 5 councillors had not completed the council's fraud and corruption awareness training. While councillors do not have to complete this training under the council's fraud policy, Loddon has the authority under its Councillor Code of Conduct to ensure that councillors complete any training it sees as necessary to fulfil their role.

Gaps in training

While we found some examples of better practice, councils could improve their training so staff and councillors who administer grants understand fraud risks and how to respond to them:

|

All audited councils … |

But could improve their training by … |

|

cover conflicts of interest in their training |

|

|

except Loddon and Southern Grampians, have updated their training in the last 2 years |

ensuring it refers to current legislation and guidance. For example, Southern Grampian's training refers to a superseded version of the Local Government Act 2020 Loddon advised us that it is currently reviewing its training content. |

Appendix A. Submissions and comments

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix A. Submissions and comments.

Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary.

Click here to download Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

Appendix C. Scope of this audit

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix C. Scope of this audit.

Appendix D. Performance ratings of audited councils

Click the link below to download a PDF copy of Appendix D. Performance ratings of audited councils.

Click here to download Appendix D. Performance ratings of audited councils