Kinship Care

Snapshot

Is the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH) supporting timely, stable and quality placements for children and young people through the new kinship care model?

Why this audit is important

Kinship care is the support provided by relatives or a member of a child's social network when they cannot live with their parents. It is the fastest-growing form of out-of-home care in Victoria.

Available information shows that between 2017 and 2021, the number of children and young people in kinship care grew by 33.2 per cent.

DFFH introduced a new kinship care model in 2018 to accommodate this growth and respond to issues with the level of support kinship carers were receiving.

What we examined

We examined DFFH and 3 other kinship care service providers—Anglicare Victoria, Uniting Vic.Tas, and the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency.

We assessed if the new kinship care model helps identify kinship networks in a timely manner for children and young people at risk and provides them with stable and quality placements.

What we concluded

DFFH cannot be assured that it is providing timely, safe and stable placements for children and young people at risk. This is because it does not systematically monitor or report on if it is achieving the new model's objectives.

DFFH also does not ensure that staff and service providers complete mandatory assessments on how safe a home is, what support the carer needs and the child's wellbeing. This puts children in care at risk because DFFH cannot confirm if they are being cared for in a safe environment.

Kinship carers are also not receiving the support they need to provide stable homes for children and young people in their care.

What we recommended

We made 12 recommendations to DFFH, including 6 about identifying kinship networks early, one about completing mandatory assessments, 2 about support for carers and 3 about monitoring and reporting on the new model.

Video presentation

Key facts

Source: VAGO.

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

What is kinship care?

We refer to children and young people throughout this report as ‘children’ for simplicity.

Kinship care is the preferred type of out-of-home care (OOHC) for children and young people in Victoria. Kinship carers can be family members or non-family members who are in the child or family's social network.

Kinship carers need different support to other types of OOHC carers due to their unique circumstances as relatives or close friends of both the parents and the child needing care.

For example, as Figure A shows, they may make the decision to become a carer quickly during a stressful family crisis involving a grandchild, niece, nephew, cousin or family friend. Kinship carers often continue to have a relationship with the child's parents. This may cause issues due to family contact, which can impact the carer's and child's emotional wellbeing.

Figure A: Case study: from grandmother to kinship carer

‘I went to bed one night single, I woke up the next morning with 3 children. I didn’t have a pregnancy to prepare for having kids—or deal with the traumatised behaviour and difficulties that have added to the challenge’.

That’s how a grandmother describes her experience of becoming a kinship carer to her 3 grandchildren 4 years ago.

The carer’s adult daughter was battling a drug addiction. After an overdose, it became clear that she could no longer look after her children.

Rather than have the children placed with a foster family they did not know, the grandmother embarked on a journey as the sole carer of 3 kids under 9.

Source: VAGO, adapted from Anglicare Victoria (Anglicare).

Finding a home early

Having a network of caring adults helps a child feel a sense of belonging and connection to their family, culture and community.

Academic research also shows that if children are not placed in a stable kinship placement early, they are more likely to need specialised mental health services or be involved in the youth justice system than others in OOHC.

In 2018, the Victorian Government introduced a new kinship care model to:

- help child protection practitioners find carers early or in a timely manner

- strengthen community connections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in care

- deliver better and more flexible support to carers.

DFFH was established in February 2021 when the former Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) split into 2 departments.

Throughout this report we use ‘DFFH’ to refer to actions taken by both DFFH and the former DFFH for simplicity.

To help achieve these objectives, the Department of Families, Fairness and Housing (DFFH) established:

- kinship engagement teams (KETs), which are made up of 44 full-time workers across the state, to help DFFH's child protection practitioners find kinship placement options, or 'kinship networks', early

- the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program, which the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency (VACCA) delivers, to find kinship networks for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

Not working with KETs to identify kinship networks early

DFFH cannot demonstrate that KETs are helping identify kinship networks early.

We found gaps in how KETs collaborate with child protection practitioners, who play a critical role in referring children to KETs.

Deficiencies in DFFH's procedures, guidance and training for child protection practitioners mean they do not fully understand KETs' role and are hence unable to help facilitate timely identification of kin. For example:

- DFFH's Child Protection Manual does not include specific triggers for when and how child protection practitioners should refer cases to KETs, which leaves it to the discretion of individual practitioners

- DFFH's training for child protection practitioners does not specify when they should engage KETs or how KETs can help them identify potential kinship placements.

CSOs are funded by DFFH to provide kinship care services to families in areas close to where they live.

ACCOs are funded by DFFH to provide kinship and cultural connection services. They also facilitate and coordinate support for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship carers and healing groups.

We also heard from community service organisations (CSOs) and Aboriginal community-controlled organisations (ACCOs) that DFFH provides limited training on KETs' role.

Additionally:

- DFFH's guidelines for KETs do not include children at risk of needing OOHC in the list of young people to prioritise.

- DFFH has not defined what finding a kinship network ‘early’ means or set timeframe benchmarks.

- DFFH does not consistently monitor and report on KETs’ performance.

Identifying Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship networks early

DFFH cannot demonstrate if the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program is leading to timely kinship placements and cultural connections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. This is due to weaknesses in how DFFH set up the program. In particular:

- DFFH has not set up effective referral systems and processes to help VACCA identify kinship networks early

- similar to general kinship care, DFFH has not defined what 'early' means when identifying kinship networks for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

- DFFH does not monitor the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program across the state and therefore does not have a thorough understanding of:

- how many children it has referred to VACCA

- the timeliness of these referrals

- the outcomes of these referrals.

These gaps mean that DFFH is placing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in homes that are not culturally appropriate.

A 2019 evaluation of the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program, which DFFH commissioned, found that around 56 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC in Victoria are placed with a non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carer. Over 50 per cent are separated from their siblings and 56 per cent have no cultural support plan.

This can lead to children experiencing a lack of connection with their culture and family.

Not measuring if kinship networks are being identified early

When DFFH designed the new model, it defined a performance measure for identifying kinship networks early. DFFH intended for this measure to assess the proportion of children who enter kinship care as their first OOHC placement. However, DFFH does not report on this measure. It also has not defined a percentage increase for its target.

DFFH uses CRIS to manage and deliver child protection services.

We analysed available data from DFFH's Client Relationship Information System (CRIS) to assess its progress against this measure. Appendix C explains why readers should exercise caution when interpreting CRIS data.

We found that between 2018 to 2021, the proportion of children who entered kinship care as their first placement increased from 74.5 per cent to 79.5 per cent. However, as DFFH has not specified a target for the increase, they do not know if this is a good result.

Based on our discussions with DFFH staff, this increase is likely due to child protection practitioners becoming more familiar with the referral process over time and getting involved earlier instead of DFFH’s actions.

Recommendations about identifying kinship networks early

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

|

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing |

1. sets clear benchmarks for identifying kinship networks early (see Section 2.1) |

Accepted |

|

2. develops mandatory and ongoing training programs for child protection practitioners to improve their awareness of kinship engagement teams’ role (see Section 2.1) |

Accepted |

|

|

3. updates its Child Protection Manual to include specific triggers for when and how child protection practitioners should refer cases to kinship engagement teams (see Section 2.1) |

Accepted |

|

|

4. implements consistent monitoring and reporting for kinship finding activities that at minimum capture the amount of time it takes between a kinship engagement team receiving a referral and identifying a kinship placement (see Section 2.1) |

Accepted |

|

|

5. works with service providers to agree and set benchmarks for finding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship networks to be accountable for (see Section 2.2) |

Accepted |

|

|

6. establishes processes to monitor and report on:

|

Accepted |

Putting children at risk

DFFH’s guidelines require its child protection practitioners and, where relevant, case workers from CSOs and ACCOs to complete the assessments listed in Figure B.

Figure B: Mandatory assessments and their purposes

| Assessment | Purpose |

|---|---|

|

Part A |

To assess if a placement is safe when it starts |

|

Part B |

To assess what support the carer and child need for a safe and stable home |

|

Part C |

To assess:

|

Source: VAGO based on DFFH documents.

Not completing assessments on time

DFFH has mandated timeframes for completing part A, B and C assessments. In 2016, a review commissioned by DFFH recommended that each DFFH division monitors and reports on child protection practitioners’ and case workers’ compliance with these timeframes. However, none of the divisions currently do this.

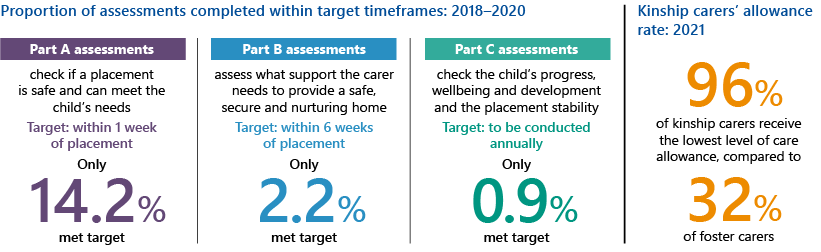

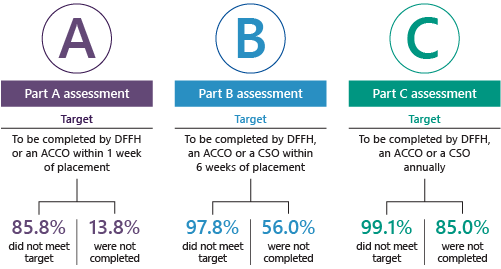

As Figure C shows, our review of available CRIS data found that DFFH and, where relevant, CSOs and ACCOs are not completing part A, B and C assessments on time. In many instances, they are not completing them at all. This has serious implications for children and their carers. When an assessment is not completed, the carer is unlikely to receive the full level of support they are entitled to, which puts the placement’s stability at risk.

Figure C: Percentage of part A, B and C mandatory assessments completed and completed within timeframes between 2018 and 2020

Note: Part A assessments are completed by DFFH or one of the 2 specific ACCOs that are authorised under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (CYF Act) to take responsibility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC on court orders as part of the Aboriginal Children in Aboriginal Care (ACAC) program.

Part B and C assessments are completed by DFFH or one of the ACCOs authorised under the CYF Act. CSO or ACCO case workers only complete Part B or C assessments if DFFH has referred the placement to them for either the First Supports program or case contracting. In these instances, DFFH needs to endorse the assessments done by CSOs and ACCOs before they are considered completed.

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data and DFFH documentation.

Not completing assessments to a sufficient standard

While timing is crucial, it is also important that part A, B and C assessments thoroughly assess the child's and carer’s needs.

We reviewed a random selection of part A, B and C assessments for 72 CRIS case files and assessed them against criteria listed in DFFH's mandatory policy requirements. To do this, we assessed how many of the criteria DFFH and service providers completed for the various assessments. As Figure D shows, we found that DFFH and, where relevant, CSOs and ACCOs did not complete these assessments to a sufficient standard.

Figure D: Thoroughness of assessments

| Assessment | Criteria | Our assessment |

|---|---|---|

|

Part A |

|

At least 41 per cent of all part A assessments were not completed to a sufficient standard. |

|

Part B |

|

At least 17 per cent of all part B assessments were not completed to a sufficient standard. |

|

Part C |

Assessment links to the child’s case plan and assesses:

|

20 placements continued for more than a year, but only 7 of these had a part C assessment completed. While all 7 completed part C assessments fully assessed the criteria, only 5 linked to the child’s case plan. |

Note: Figure D only refers to completed assessments. As Figure C shows, many are not completed at all.

We excluded files that we assessed as ‘not applicable’ from this review. For example, if a placement continued for less than one week or if the child was reunified with their parents before the part A assessment was completed.

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS file review.

Recommendation about completing mandatory assessments

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

|

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing |

7. monitors and reports on whether child protection staff and, where relevant, community service organisations and Aboriginal community-controlled organisations:

|

Accepted |

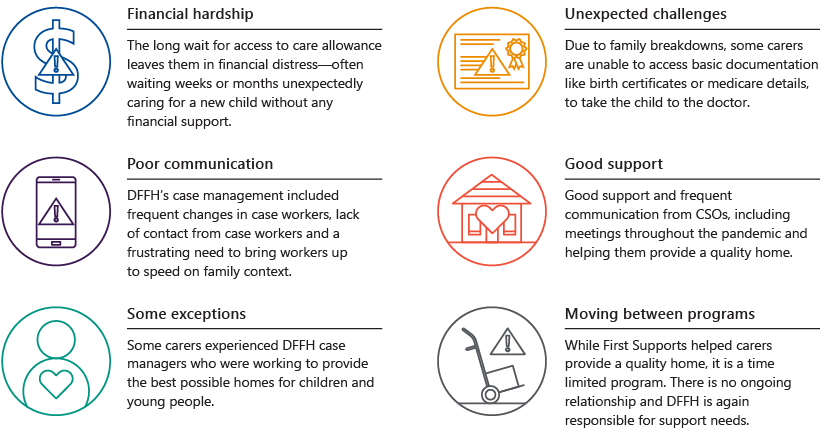

Insufficient support to carers

The First Supports program provides targeted support services to new kinship placements.

The kinship care model has increased the financial support available to carers, including DFFH’s First Supports program. However:

- not all eligible placements are referred to the First Supports program on time

- in some instances, placements are not referred to the program at all

- kinship carers continue to experience barriers to accessing financial support.

Not all placements are referred to First Supports on time or at all

Between June 2019 to March 2021, DFFH referred approximately 37 per cent of eligible placements to CSOs and ACCOs, who deliver the First Supports program. This is likely because DFFH's child protection practitioners have a varied understanding of the First Supports program.

This means that many kinship carers are missing out on support they should be getting.

We also found that while the benchmark is 21 days, it takes DFFH on average 28 days to refer a placement to the program after completing the part A assessment. Late referrals reduce CSOs’ and ACCOs' ability to provide early support to kinship carers, many of whom are unfamiliar with the OOHC system.

Barriers to accessing financial support

Brokerage is an allocation of money to a carer for a one-off purchase that will help support the placement.

Under the new model, kinship carers can access:

- financial brokerage to help pay for one-off costs, such as buying a new bed or car seat

- financial assistance to help set up a placement.

Kinship carers can also access a care allowance, which was already in place before DFFH introduced the new model. This allowance helps carers pay for the ordinary costs of care, such as food, fuel, clothing and pocket money.

A SNA is how a kinship carer can apply for a higher care allowance level. DFFH’s policy states it will only approve a higher care allowance in exceptional circumstances. A SNA lasts for one year, at which point the carer must reapply.

We held feedback sessions with 16 kinship carers as part of this audit. They told us they were unaware of the financial support available to them.

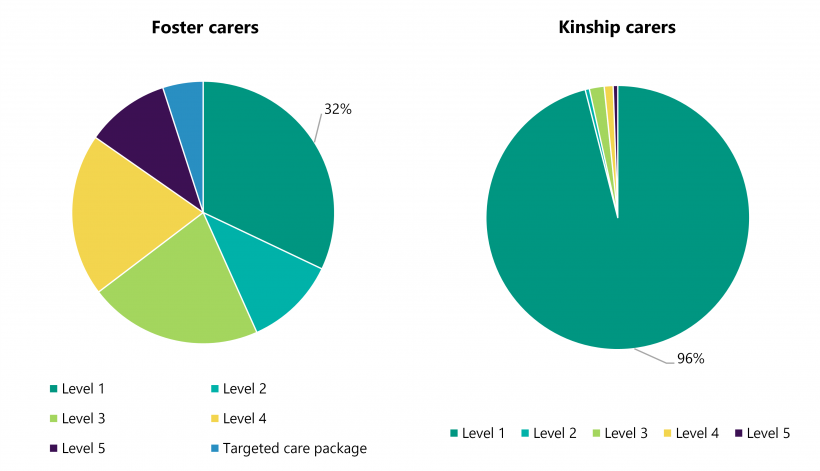

As of June 2021, 96 per cent of kinship carers still receive the lowest level of care allowance compared to 32 per cent of foster carers.

From early 2018 to March 2019, KETs submitted 92 special negotiated adjustment (SNA) applications to DFFH area operations managers for higher care allowances. Only 17 (18 per cent) of these were approved.

Our discussions with kinship carers, CSOs, ACCOs and KET staff highlighted that applying for a higher allowance level is a lengthy process that requires receipts and other supporting documentation. In comparison, DFFH gives foster carers an allowance based on the child’s needs at the start of a placement without requiring supporting documentation.

Recommendations about supporting carers

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

|

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing |

8. reviews the special negotiated adjustment process to increase transparency and equity in the care allowance payments process (see Section 3.2) |

Accepted |

|

9. monitors and reports:

|

Accepted |

Ensuring the long-term quality and safety of placements

DFFH intends for the new model to provide high-quality placements that support children living in kinship families to thrive.

However, DFFH does not measure or report on the extent to which it is achieving the new model's objectives.

DFFH does not know if the new model is giving children high quality, safe and stable placements. For example:

|

DFFH ... |

But ... |

|---|---|

|

has established outcome measures for the new model that link to placement quality |

it has not:

|

|

runs a survey that provides some insights into outcomes for children in OOHC |

its OOHC Outcomes Tracking Survey results do not differentiate between the different types of OOHC, so it is not possible to identify the results that are relevant to kinship care. DFFH also takes part in a national survey by collecting Victorian data on the views of children in OOHC. However, the most recent The Views of children and young people in out-of-home care: Overview of indicator results from the second national survey predates the new model and therefore cannot show if outcomes are improving. |

![]() We did not and am still not receiving support requested or needed. Case managers or staff change without us being informed. Phone messages left at their office and drop in calls to their office asking them to contact us were mostly ignored.’

We did not and am still not receiving support requested or needed. Case managers or staff change without us being informed. Phone messages left at their office and drop in calls to their office asking them to contact us were mostly ignored.’

By not monitoring its progress against the new model’s outcomes, DFFH cannot determine if it is meeting them.

Not supporting carers’ needs

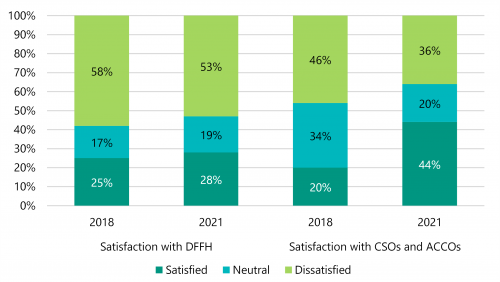

DFFH has run 2 kinship carer surveys since it introduced the new model—a survey in 2018 and a carer census in 2021. These surveys show that carers’ views about the support DFFH provides have not changed significantly.

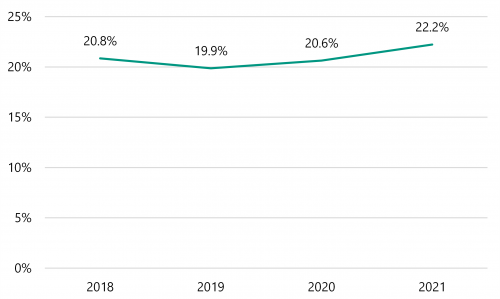

As Figure E shows, more than half of kinship carers have continued to report that they are dissatisfied with DFFH’s support.

In contrast, kinship carers’ satisfaction with the support they receive form CSOs and ACCOs significantly increased from 20 per cent to 44 per cent between 2018 and 2021.

Figure E: Kinship carers’ satisfaction with DFFH’s support and CSOs’ and ACCOs' support

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH’s 2018 survey and 2021 census.

These results show that carers’ long-term dissatisfaction with DFFH’s support has continued after it introduced the new model. This includes not having consistent case workers, not getting sufficient financial support and finding it difficult to navigate the child protection system.

In our feedback sessions, some carers cited examples where they received timely and valuable support from DFFH’s child protection practitioners. However, most carers told us they have had trouble getting the support they need from DFFH and have received insufficient or untimely financial assistance.

Consistent with the 2021 census results, carers spoke positively to us about the role CSOs and ACCOs are playing compared to DFFH:

|

Kinship carers reported … |

Compared to DFFH … |

|---|---|

|

good relationships and frequent communication with CSO and ACCO case workers, including meetings throughout the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic |

|

|

that CSOs and ACCOs respond to their requests for support in a timely way, particularly for things that cannot wait, like clothing and psychological support |

taking a long time to provide financial support. Carers told us that they have sometimes waited months without any financial support. |

Recommendations about measuring and reporting on the quality of kinship care

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

|

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing |

10. identifies the data it needs, establishes a performance baseline and defines data collection methods for the new model’s outcome measures (see sections 4.1 and 4.2) |

Accepted |

|

11. systematically monitors and reports on if the new model is contributing to high-quality, safe and stable placements (see Section 4.3) |

Accepted |

|

|

12. collects and presents data in its carer surveys that differentiates between results for different types of out-of-home care carers (see Section 4.4). |

Accepted |

1. Audit context

All children have the right to grow up happy, healthy and safe in a stable, caring environment. If a child's home is unsafe due to the risk of violence, abuse or neglect, DFFH may need to place them in an alternative care environment.

Under the Children, Youth and Families Act 2005 (the CYF Act), if a child needs to be removed from their home, DFFH should consider placing the child with an appropriate family member or other person significant to them before considering other placement options.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 OOHC in Victoria

If parents are unable or unwilling to keep their children safe at home, the state’s OOHC system provides alternative care for them. While some children are placed in this system for only a few days or weeks, others spend many years in it.

There are 3 main types of placements:

- foster care, where trained carers provide care

- residential care, where children live in community-based care homes

- kinship care, where relatives or other familiar people in a child’s life provide care.

Kinship care

Kinship care is the fastest-growing placement type in Victoria. Available information indicates that:

- over 70 per cent of all children in OOHC live with a kinship carer

- between 2017 and 2021, the number of children in:

- OOHC grew by 25.2 per cent from 7,571 to 9,498

- kinship care grew by 33.2 per cent from 5,577 to 7,429.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are significantly over represented in kinship care. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Victoria are 20.1 times more likely to be in kinship care than non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

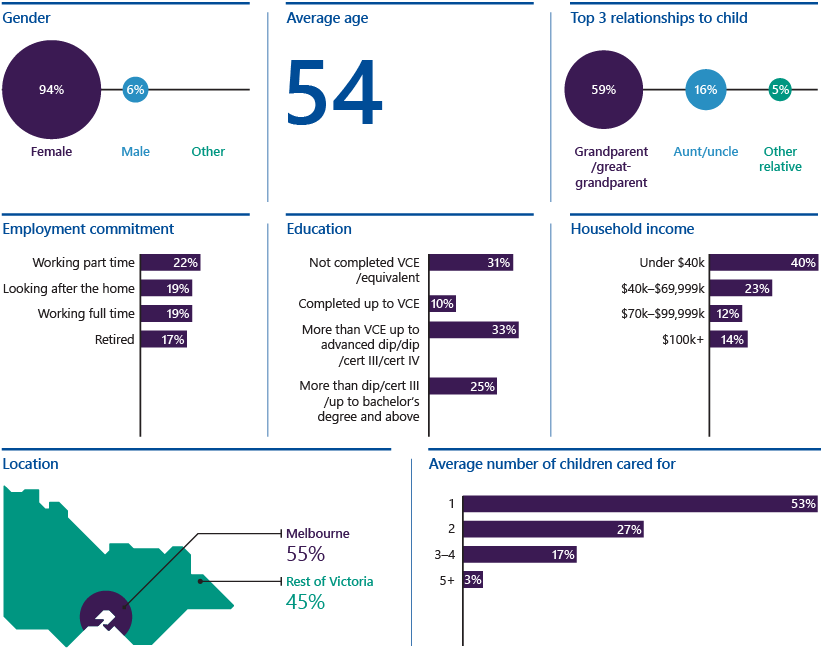

Who are kinship carers?

Kinship carers are typically female, grandparents or great-grandparents and live on lower incomes. Figure 1A outlines the main characteristics of kinship carers in Victoria.

FIGURE 1A: Key characteristics of kinship carers

Note: *Total of percentages equals 99% due to rounding. **VCE stands for the Victorian Certificate of Education.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH’s 2021 census.

Legislation

The CYF Act outlines the requirements for OOHC in Victoria. It prioritises the child’s best interests, including protecting their rights and development.

Under the CYF Act, kinship care is the preferred option for children entering OOHC. The Aboriginal child placement principle in the CYF Act prioritises placing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander relatives or, where this is not possible, other extended family.

The CYF Act requires the government to provide a framework that promotes the rights and wellbeing of children in OOHC. Appendix D shows the Charter for children in out-of-home care, which outlines the expected standards for a child’s experience in OOHC.

1.2 Roles and responsibilities

Department of Families, Fairness and Housing

DFFH is responsible for designing and delivering programs that provide safe homes for children who cannot live with their family, including kinship care.

DFFH also contracts CSOs and ACCOs to provide OOHC services.

DFFH’s agency performance system supports staff within its divisions manage its contracts with CSOs and ACCOs and monitor their performance.

Child protection practitioners

Child protection practitioners work for DFFH and are based across 17 geographical areas within DFFH’s 4 divisions (north, south, east and west) and its statewide services group.

Child protection practitioners have a specific statutory role, which includes:

- receiving and investigating allegations of harm or risk of harm to children

- working with children, families and support services to make sure children are safe if they identify abuse or neglect

- applying for Children's Court of Victoria orders when needed.

If a child requires OOHC, child protection practitioners work with the child, the child's family and support services to find a suitable placement and provide ongoing support.

Child protection practitioners complete part A assessments. However, 2 specific ACCOs that are authorised under the CYF Act to take responsibility for Aboriginal Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC on court orders as part of the ACAC program may also complete part A assessments.

Child protection practitioners and, where relevant, CSO and ACCO case workers are responsible for completing part B and C assessments.

CSOs and ACCOs

DFFH funds 28 CSOs and 13 ACCOs to provide kinship care services across Victoria.

Two ACCOs—VACCA and Bendigo & District Aboriginal Co-operative—are authorised under the CYF Act to take responsibility for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC on court orders as part of the ACAC program.

CSO and ACCO case workers also provide the following services:

- First Supports services, including:

- completing part B assessments

- providing up to 110 hours of family services support

- providing financial support for carers to purchase one-off items or services

- giving information and advice to kinship carers about community resources, peer support and access to training

- case contracting, which includes case management services for children living in kinship care.

CSOs and ACCOs report to DFFH monthly on their performance, such as the daily average number of placements receiving case contracting services and the number of assessments completed.

1.3 Sector reforms

Roadmap for Reform: Strong Families, Safe Children

The Roadmap for Reform: Strong Families, Safe Children (the roadmap) is the Victorian Government's blueprint to transform the child and family system to improve outcomes for vulnerable children and families. The government released the roadmap in 2016 following the Royal Commission into Family Violence. The roadmap has 2 reforms for kinship care:

- strengthening OOHC

- improving outcomes for children in OOHC.

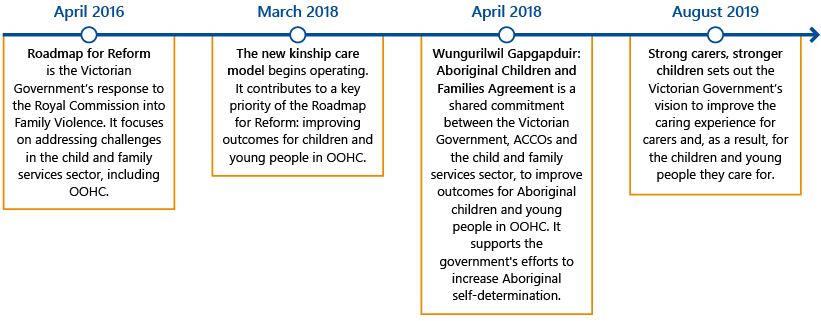

Figure 1B shows the key reforms since the roadmap was released.

FIGURE 1B: Timeline of sector reforms

Note: Self-determination is about supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities to make decisions about their own social, cultural and economic needs.

Source: VAGO.

The new kinship care model

A statutory placement is where a Children's Court of Victoria order requires a child or young person to live in a placement outside of their family home.

DFFH started using the new kinship care model in March 2018. The model seeks to better support statutory kinship placements to promote safe and quality care.

The model also aims to reduce the likelihood of children entering residential care. It recognises that in residential care, children experience poorer long-term health and wellbeing outcomes. The main components of the new model are:

- First Supports program

- KETs

- Aboriginal Kinship Finding program

- case contracting

- brokerage.

Appendix E provides more information about these components.

1.4 Past reviews

Recent reviews have found that children in OOHC and their carers face significant challenges, including a lack of support. Figure 1C summarises the findings from these reviews.

FIGURE 1C: Key findings from recent reviews

| Title | Year | Key findings |

|---|---|---|

|

Royal Commission into Family Violence: final report |

2016 |

|

|

Review of the kinship care model (commissioned by DFFH) |

2016 |

|

|

Investigation into the financial support provided to kinship carers (Victorian Ombudsman) |

2017 |

|

Source: VAGO

2. Finding a home

Conclusion

DFFH cannot demonstrate that its processes are helping identify kinship networks early or in a timely way.

There is also a risk that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are not being placed in culturally appropriate homes as DFFH cannot demonstrate these children are getting timely and appropriate kinship placements and cultural connections. This means it is unlikely that the model is achieving its aim to strengthen the cultural connections of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in kinship care.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 Finding placements early

When DFFH designed the new model, it identified new performance measures and committed to reporting on them. DFFH's performance measure for identifying kinship networks early is an increase in the proportion of children who enter kinship care as their first OOHC placement.

We found that DFFH does not report on this measure and has not defined a percentage increase target. We analysed CRIS data to assess DFFH’s performance against this measure.

Figure 2A shows that the proportion of children who entered kinship care as their first placement increased from 74.5 per cent in 2018 to 79.5 per cent in 2021.

FIGURE 2A: Proportion of children who entered kinship care as their first OOHC placement from 2018 to 2021

| Year | Total number of children who entered OOHC | Total number of children placed in kinship care first | Proportion of children placed in kinship care first |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 3,097 | 2,308 | 74.5% |

| 2019 | 3,321 | 2,538 | 76.4% |

| 2020 | 2,791 | 2,190 | 78.5% |

| 2021 | 2,479 | 1,970 | 79.5% |

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data.

However, without a target for the increase, DFFH does not know if this is a good result. DFFH also cannot confirm the increase is due to its efforts because:

- it has not defined what identifying a kinship network ‘early’ means

- there are gaps in how it integrates KETs with its child protection practitioners

- it does not consistently monitor if KETs are supporting the new model’s objectives.

Not defining ‘early’

Under the new model, KETs are one of the inputs needed to achieve the objective of identifying kinship networks early. However, DFFH has not defined what it considers identifying a kinship network ‘early’.

DFFH’s ‘Kinship engagement teams roles and responsibilities’ document, which is the main guideline for KETs, also does not include children at risk of needing OOHC in the list of young people to prioritise. KETs currently prioritise:

- children in placements that are at risk of breaking down

- children in residential care and foster care

- children in contingency placements or in other short-term arrangements or programs

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

- children with a disability.

DFFH advised us that KETs do kinship finding as an added service where needed. Child protection practitioners or authorised ACCOs are responsible for identifying kinship networks and systems of support for children at risk of entering OOHC.

However, not prioritising children at risk of needing OOHC effectively de-prioritises this cohort and shows that there is a disconnect between the new model’s objective and how DFFH practically applies it.

Gaps in integrating KETs with child protection practitioners

As DFFH intends for KETs to work with child protection practitioners, we expected it to have:

- clear roles and responsibilities for both types of roles

- defined procedures that set out when and how child protection practitioners should engage KETs

- training and governance structures to embed their integration.

While DFFH has some of these things, we found various gaps. In particular:

|

DFFH ... |

But ... |

|---|---|

|

has included brief references to KETs in sections of the Child Protection Manual that refer to kinship finding |

there are no specific triggers for when and how child protection practitioners should refer cases to KETs, which leaves it to their discretion. |

|

has included references to KETs in its mandatory training program ‘Beginning Practice’ for all child protection practitioners |

these references are brief and do not specify when practitioners should engage KETs or how KETs can help them identify potential kinship placements. |

|

established local governance structures, such as working groups, in the early stages of the new model to integrate KETs with child protection practitioners |

these structures were not consistent across all of DFFH’s divisions due to its devolved governance model, where divisions have their own individual service arrangements. |

These gaps create a risk that child protection practitioners will not:

- fully understand the role of KETs

- use KETs to their full potential to identify kinship networks early.

A 2019 review completed by DFFH’s west division found that child protection practitioners and KETs often work in silos and were unclear about each other’s roles and functions.

Similarly, a 2019 review commissioned by DFFH found that while KETs had clearly defined roles and responsibilities, these were not always clear to child protection practitioners who work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children.

KET staff and child protection practitioners we spoke to indicated that as the new model has become more established, they have understood each other’s roles and responsibilities better. However, this is due to staff becoming more familiar with the model rather than DFFH’s procedures and guidelines.

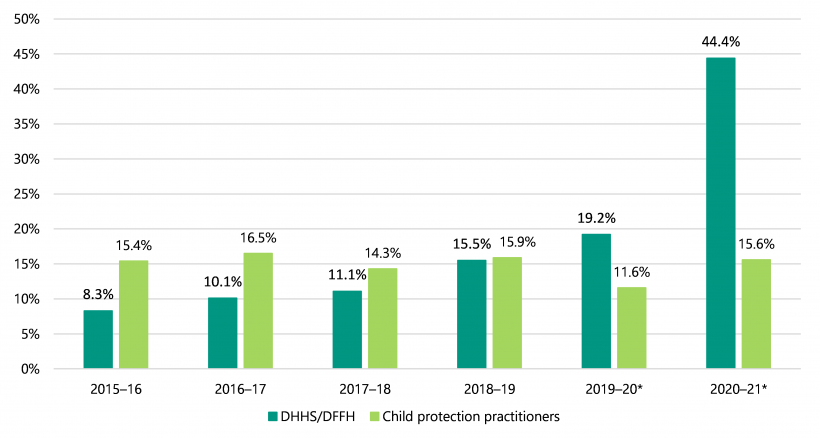

Staff and kinship carers we spoke to also raised concerns with the high turnover of child protection practitioners, which Figure 2B shows. This high turnover increases the risk that child protection practitioners will not integrate with KETs.

FIGURE 2B: Annual staff turnover for DHHS/DFFH overall compared to child protection practitioners from 2015–16 to 2020–21

Note: *The 2019–20 and 2020–21 annual staff turnover for DHHS/DFFH reflects the Victorian Government’s divestment in disability services due to the National Disability Insurance Scheme.

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

Inconsistently monitoring and reporting on KETs

DFFH does not consistently monitor and report on KETs. As a result, it does not understand what KETs are primarily working on and how well this supports the new model’s objectives.

Between 2018 and 2019, KETs manually tracked their work with a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. However, this reporting tool tracked how efficient KETs were at referring and closing cases rather than indicating if they were identifying kinship networks early.

Since 2019, DFFH has improved CRIS to allow KETs to directly receive referrals within it. This means that KETs do not need to manually record when they receive and close cases.

However, DFFH does not systematically use CRIS to report on KETs’ performance. As a result, it is missing an opportunity to understand their impact on identifying kinship networks early across the state.

2.2 Kinship placements and cultural connections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children

The new model aims to support Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC as follows:

- strengthen their self-determination by ensuring that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people can make decisions about their children and families

- support the outcomes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander care by:

- identifying their cultural needs early

- strengthening their cultural safety and connections

- promote compliance with the Aboriginal child placement principle under the CYF Act.

Figure 2C shows an example of how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship finding works to help identify cultural connections for children in OOHC.

FIGURE 2C: Case study: an example of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship finding

A regional DFFH office identified an Aboriginal young person who was at risk.

DFFH proposed to remove the young person from their family home, where they were living with a non-Aboriginal paternal grandmother and her partner.

The grandmother and her partner said that the young person could not live with them anymore because they were getting too old and did not have enough space. Nobody knew where either of the young person’s parents were.

The grandmother did not have any additional information about the young person’s mother’s Aboriginality and DFFH’s limited information did not include the mother's broader cultural or family history.

DFFH initially contacted the local ACCO to see if it had any information that would help it find relatives for kinship care. The local ACCO could not provide information other than it understood the mother came from another part of the state.

DFFH recorded this limited information and the young person’s details in an application to the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program.

Some 8 months later, the ACCO that ran the program produced a detailed report identifying a number of family contacts and information related to the young person’s culture, language, family history and country.

When DFFH child protection practitioners received the report they had since placed the young person with a non-Aboriginal family who they were not related to.

DFFH used the information in the report to build a more detailed and specific cultural plan that identified opportunities for the young person to connect with their culture. DFFH organised a return to country visit for the young person, which included meeting with relatives who they previously did not know.

While the young person decided to stay in their current placement, DFFH has made plans for one of the newly found relatives to undertake respite care to further their cultural connection with the help of the local ACCO.

Source: VAGO, adapted from DFFH’s Evaluation of the Aboriginal Kinship Finding Service report.

DFFH and VACCA held several workshops to co-design and develop processes and draft the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program’s procedure manual, which VACCA led. The manual outlines the referral process and eligibility criteria for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children who need OOHC.

We expected DFFH and VACCA to have clear and efficient processes for:

- referring Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children to VACCA to find family connections and kinship placements, including timeframe benchmarks

- monitoring the progress of VACCA’s work to identify kinship networks early

- monitoring and reporting on the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program’s outcomes.

However, there are gaps in DFFH and VACCA’s referral systems and processes for finding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship networks. DFFH also does not monitor how effective these processes are across the state.

DFFH and VACCA told us they have recently reviewed the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program and intend to redesign it based on the findings of this review.

Gaps in referral systems and processes

DFFH and VACCA do not have effective processes to find kinship networks for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. In particular:

|

DFFH has not ... |

Which means ... |

|---|---|

|

included guidance in its Child Protection Manual on how to refer cases to VACCA |

child protection practitioners are unclear about the process. This can lead to them:

|

|

defined timeframes for referring children to VACCA |

there is no requirement for

|

|

automated the referral process within CRIS for efficient monitoring and record keeping. Instead, all referrals take place via email and are not tracked in a central register |

DFFH has no meaningful oversight of the referral process. There is also double handling, which is inefficient and creates risks to data integrity. |

![]() … the referral process could be streamlined by providing VACCA workers with access to CRIS as referrals were currently made by email.’

… the referral process could be streamlined by providing VACCA workers with access to CRIS as referrals were currently made by email.’

These gaps create the risk that child protection practitioners will not have access to enough information to make detailed and timely referrals to VACCA.

Our discussions with DFFH and VACCA highlighted that this risk has materialised. They cited instances where child protection practitioners:

- directly referred cases to VACCA, rather than through KETs as required

- did not use the correct forms

- did not provide enough information in referrals to help VACCA find suitable placements, such as providing a genogram of only one or 2 connections

- made referrals that did not meet the eligibility criteria

While the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program has been able to find suitable kinship placements and cultural connections for children, these gaps have led to unnecessary delays.

Lack of defined timeframes for VACCA to find kinship placements

DFFH evaluated the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program in 2020. Citing anecdotal evidence, the evaluation found that the process takes 6 to 12 months to complete. As a result, it concluded that the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program is ‘ineffective for informing short to medium-term child placement decisions’.

The evaluation noted that there are some benefits to the program though, such as identifying broader cultural connections, informing cultural plans and capturing information to inform later placement decisions.

The evaluation also highlighted that staff at VACCA have the following informal benchmarks to guide their work:

- start finding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander family connections to ensure a suitable kinship placement within one to 6 weeks of a referral

- complete kinship finding within 30 days.

![]() … our initial, fully 9 months of referrals was not strong. So, we've had a number of referrals come back where they haven't been able to establish connection because we've given them a genogram with 2 people … so really, we haven't assisted them in that space. But I think we have improved and when we have given them more fulsome, genogram and local information that they can't see from CRIS, and then they can progress ...’

… our initial, fully 9 months of referrals was not strong. So, we've had a number of referrals come back where they haven't been able to establish connection because we've given them a genogram with 2 people … so really, we haven't assisted them in that space. But I think we have improved and when we have given them more fulsome, genogram and local information that they can't see from CRIS, and then they can progress ...’

However, VACCA’s ability to meet these timeframes is compromised by:

- the quality of information in DFFH’s referrals, including a lack of information about a child’s cultural background and links to their family

- child protection practitioners not responding to requests for further information

- the unique circumstances of each referral

- delays in related processes, such as receiving birth, death or marriage certificates

- families not responding to attempts at contact

- the demand for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship finding services, which exceeds VACCA’s workforce capacity

- the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has:

- challenged VACCA’s ability to collaborate internally

- increased the number of referrals.

DFFH advised us that when it designed the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program with VACCA it focused on establishing and starting the service. VACCA advised us that it did not implement timeframe benchmarks because it and DFFH decided that the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program was not a crisis service.

We recognise the highly complex and sensitive nature of finding Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander kinship networks and the difficulty of applying a timeframe to it. However, the lack of a timeframe for referrals means that DFFH and VACCA are not finding culturally suitable placements for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in a timely way.

No statewide monitoring

A 2020 DFFH-commissioned evaluation found that the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program is contributing to self-determination in Victoria because an all Aboriginal team deliver it and it is aligned with the Aboriginal child placement principle and Wungurilwil Gapgapduir: Aboriginal Children and Families Agreement.

VACCA advised us that it provides monthly data to DFFH about the number of referrals to the program and their progress. Despite receiving this information, DFFH does not perform any statewide monitoring of:

- the number of referrals it makes to VACCA

- VACCA’s progress on referred cases

- if VACCA’s work is leading to kinship placements or cultural connections for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC.

VACCA told us it does not receive feedback from DFFH on if its work is leading to successful kinship placements or cultural connections.

Consequently, there is a risk that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children are not being placed in culturally appropriate homes.

A 2019 evaluation of the Aboriginal Kinship Finding program, which DFFH commissioned, found around 56 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in OOHC in Victoria are placed with a non-Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander carer. Over 50 per cent are separated from their siblings and 56 per cent have no cultural support plan.

3. Ensuring the care provided is safe and supported

Conclusion

DFFH is not completing placement assessments on time or to a sufficient standard. This puts the children DFFH is placing in kinship care at risk. This is likely to reduce placements’ safety and suitability and the support carers receive.

DFFH is also not referring all eligible kinship placements to the First Supports program in a timely way. Late referrals reduce CSOs’ and ACCOs’ ability to provide early support to kinship carers, many of whom are unfamiliar with the OOHC system and need help to navigate their new role.

Kinship carers continue to experience barriers to accessing finances to support the children in their care.

This chapter discusses:

3.1 Assessing the safety and suitability of placements

The new model aims to support kinship carers to:

- be emotionally supported while adjusting to their caring role

- be financially able to support a placement

- know where to go for advice and help

- have the necessary support to look after children with complex needs.

DFFH uses part A, B and C assessments to get insights into the safety, suitability and stability of a placement, including understanding the child’s needs and the carer’s capacity and needs.

We reviewed CRIS data and a selection of CRIS files to see if DFFH and, where relevant, ACCOs and CSOs are completing assessments on time and to a sufficient standard. We found that assessments are not completed on time or completed to a sufficient standard.

Not completed on time or at all

![]() The lack of support makes you question what you’re doing—is it right or is it wrong? Without the support, we kind of think when does this end, when does it get easier. It puts a lot of self-doubt within the placement.’

The lack of support makes you question what you’re doing—is it right or is it wrong? Without the support, we kind of think when does this end, when does it get easier. It puts a lot of self-doubt within the placement.’

When part A and B assessments are not completed on time, a carer is unlikely to receive the full range of support they are entitled to, which puts the placement’s stability at risk. This situation worsens when the assessments are not completed at all.

As Figure 3A shows, we found that from 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2020 DFFH and, where relevant, CSOS and ACCOs did not complete most part A, B and C assessments on time. This has serious implications for carers and the children in their care.

It is particularly concerning that for 10 per cent of the cases, the part A assessment took more than 634 days to complete and the part B assessment more than 1,261 days.

Figure 3A also shows that 13.8 per cent of part A assessments, 56 per cent of part B assessments and 85 per cent of part C assessments were not completed at all. This means that DFFH has no recorded assessment of the safety and stability of a significant number of kinship placements.

FIGURE 3A: Proportion of assessments completed and how long they took to complete, 1 January 2018 to 31 December 2020

| Assessment type | Target | Total placements | Proportion incomplete* (%) | Proportion that took longer than target (%) | Median time to complete (days) | 90th percentile** of completed assessments (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part A | 100% completed within 7 days | 7,669 | 13.8 | 85.8 | 46 | 634 |

| Part B | 100% completed within 42 days | 7,045 | 56.0 | 97.8 | 809 | 1,261 |

| Part C | 100% completed within 365 days | 4,228 | 85.0 | 99.1 | 1,034 | 1,397 |

Note: *Assessments that DFFH has not endorsed. **The 90th percentile is the value where 90 per cent of observations can be found below.

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data.

Not completed to a sufficient standard

![]() I don't think they [part A and part B assessments] are filled out extensively … I think it’s because people are time poor so if they can get away with putting a couple of lines on people see that as sufficient. But I don't actually … We need to be delving deep into the person who has put their hand up to care for the child.’

I don't think they [part A and part B assessments] are filled out extensively … I think it’s because people are time poor so if they can get away with putting a couple of lines on people see that as sufficient. But I don't actually … We need to be delving deep into the person who has put their hand up to care for the child.’

We found that DFFH and, where relevant, CSOs did not complete the assessments we reviewed to a sufficient standard.

With the delays in completing part A and B assessments, this further reduces DFFH’s, CSOs’ and ACCOs’ ability to support carers. One agency told us that DFFH provides limited training on completing assessments and it has a lack of understanding about their importance.

We reviewed a random selection of 72 case files and assessed their part A, B and C assessments against the following criteria:

- part A assessment includes:

- a police check to assess the suitability of the proposed carer

- police checks on other household members

- a review of CRIS information

- a meeting with the carer to discuss the child’s safety

- part B assessment includes:

- a kinship carer suitability assessment

- the placement’s support needs

- recommendations and a support plan

- a requirements checklist

-

C assessment links to the case plan and assesses the:

A case plan is a document that records all of the significant decisions concerning a child in kinship care, such as their care arrangements, cultural support or developmental needs.

- child’s wellbeing and development

- overall suitability of the placement

- suitability of the carer’s financial support.

Of the 72 case files we assessed:

- DFFH completed a part A assessment for 55 of them (76 per cent)

- DFFH completed a part B assessment for 13 of them (18 per cent) and approved an additional 11 (15 per cent) that CSOs completed

- 20 placements continued for more than a year, but only 7 of these placements had a completed part C assessment.

A 95 per cent confidence interval is the range of values of which you can be 95 per cent confident that the true value lies within.

Part A assessments

We found that 28 of the 55 completed part A assessments we reviewed (51 per cent) were not done to a sufficient standard. Based on this sample, within a 95 per cent confidence interval, DFFH does not sufficiently complete at least 41 per cent of all part A assessments.

Figure 3B shows the checks DFFH completed for the part A assessments we reviewed.

FIGURE 3B: Thoroughness of part A assessments completed by DFFH

| Criteria | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Completed police check | 45 | 10 |

| Completed police check on other household members | 31 | 24 |

| Completed review of CRIS information | 31 | 24 |

| Meeting with the carer | 52 | 3 |

| All 4 sections completed | 27 | 28 |

Note: Of the 72 case files we reviewed, 55 had a completed and approved part A assessment. Our file review did not include any part A assessments completed by the 2 ACCOs authorised under the CYF Act as part of the ACAC program.

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data.

Part B assessments

We found similar issues with part B assessments. As Figure 3C shows, 7 of the 24 completed part B assessments we reviewed (29 per cent) were not done to a sufficient standard. Based on this sample, within a 95 per cent confidence interval, DFFH and CSOs do not sufficiently complete at least 17 per cent of all part B assessments.

FIGURE 3C: Thoroughness of part B assessments completed by DFFH and CSOs

| Criteria | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Completed kinship carer suitability assessment | 20 | 4 |

| Includes support needs | 19 | 5 |

| Includes recommendations and support plan | 5 | 4 |

| Includes requirements checklist | 19 | 5 |

| All 4 sections completed | 17 | 7 |

Note: Of the 72 case files we reviewed, 24 had a completed and approved part B assessment. DFFH completed 13 part B assessments and CSOs completed 11.

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data.

Part C assessments

All 7 part C assessments we reviewed were completed by DFFH and fully assessed the child’s wellbeing and development, the suitability of the placement and the suitability of the carer's financial support. However, only 5 of them linked to the child’s case plan It is important that part C assessments are linked to the case plan as this is a key document that identifies strategies to achieve stability in the placement.

3.2 Supporting carers

Under the new model, DFFH set up the First Supports program and the following financial assistance to help carers:

- financial brokerage, including brokerage through the First Supports program and kinship placement support brokerage

- placement establishment costs.

Carers also have access to a care allowance, which has been in place prior to the new model.

However, we found:

- not all eligible placements are referred to First Supports in a timely way or at all

- kinship carers still receive less care allowance than foster carers

- First Supports brokerage is not flowing through to carers

- DFFH does not know if it is providing timely and customised financial support to carers

- carers are confused about what financial support is available.

Not all eligible placements are referred to First Supports in a timely way or at all

DFFH child protection practitioners and ACCO case workers can refer a new placement to First Supports if they expect the placement will last more than 3 months and they have completed a part A assessment. Identifying if a placement will last more than 3 months is a professional judgement and operational challenge. DFFH has not set guidance or provided tools to help child protection practitioners assess this.

We found that between June 2019 to March 2021, child protection practitioners referred 37 per cent of placements that lasted more than 3 months to First Supports. This is likely because child protection practitioners have a varied understanding of the program.

We also found that while the benchmark is 21 days, the average amount of time it took for DFFH to refer a placement to First Supports after completing the part A assessment was 28 days.

This means that carers are missing out on the customised support they are entitled to. Late referrals also reduce CSOs’ and ACCOs’ ability to provide early support to kinship carers, many of whom are unfamiliar with the OOHC system and need help to navigate their new role.

Kinship carers still receive less care allowance than foster carers

![]() The allowance goes nowhere near covering childcare expenses … to take on the care of a child with no clothes, cot or items they need is very financially draining.’

The allowance goes nowhere near covering childcare expenses … to take on the care of a child with no clothes, cot or items they need is very financially draining.’

DFFH has set 5 care allowance levels, each with 4 age bands, that reflect the diverse needs of children in OOHC. For example, for a child aged 7 years or younger in 2021–22, the allowance ranges from $418.68 per fortnight (level one) to $1,705.36 per fortnight (level 5).

The Victorian Ombudsman’s 2017 Investigation into the financial support provided to kinship carers found that kinship carers received less care allowance than foster carers. In 2017, 96.8 per cent of kinship carers received the lowest level of allowance. In contrast, only 40 per cent of foster carers received the lowest level of allowance.

The Ombudsman found that this was mostly due to differences in how care allowances are set during and at the start of a placement:

|

While kinship carers ... |

Foster carers ... |

|---|---|

|

were automatically eligible for the lowest level of care allowance at the beginning of a placement |

were eligible for an allowance based on the child’s individual needs at the beginning of a placement. |

|

must apply for a SNA if DFFH assesses the child as having higher needs |

receive an increase in their care allowance level if a child’s needs change over time following DFFH’s approval after consulting with a CSO or ACCO. |

The Ombudsman recommended that DFFH change its processes for assessing kinship carers’ support needs, such as ensuring that part A, B and C assessments inform applications for higher allowance levels. It also recommended streamlining the approval process for higher allowance levels.

In response, DFFH included prompts in part A and B assessments for child protection practitioners and case workers to consider the need for a higher allowance level. It also included supporting applications for SNAs in KETs’ roles and responsibilities.

However, these changes have had little impact on the amount of care allowance kinship carers receive.

As Figure 3D shows, 96 per cent of kinship carers still receive the lowest level of care allowance. In contrast, only 32 per cent of foster carers receive the lowest level.

FIGURE 3D: Percentage of kinship carers and foster carers per level of carer allowance in 2021

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH data.

Additionally, from early 2018 to March 2019, KETs completed 92 SNA applications for higher care allowances. However only 17 (18 per cent) were successful.

Our discussions with kinship carers, CSOs, ACCOs and KET staff highlighted that making a case to DFFH for a higher allowance level is a long process.

For example, kinship carers must provide evidence, such as receipts and other supporting documentation, to show they need a higher allowance. In comparison, foster carers are given an allowance based on the child’s needs at the start of a placement.

First Supports brokerage not flowing to carers

![]() It took 6 months to get the child a bed … housing is a huge problem now as I am looking after another child. I have been asking for help for 12 months or more. One child sleeps in my room and another sleeps on a mattress in the lounge.’

It took 6 months to get the child a bed … housing is a huge problem now as I am looking after another child. I have been asking for help for 12 months or more. One child sleeps in my room and another sleeps on a mattress in the lounge.’

DFFH gives CSOs and ACCOs $1,000 per carer as First Supports brokerage. CSOs and ACCOs give this funding to carers when they need to buy an item or service to help integrate a child into a placement or maintain it.

CSOs and ACCOs have full discretion on how they manage these brokerage allocations. They can choose to pass on more or less than $1,000 to an individual carer based on their assessment of the carer’s needs. CSOs’ and ACCOs’ ability to pass on more than $1,000 depends on some carers receiving less than $1,000.

Since November 2020, CSOs and ACCOs have reported their brokerage spending through service delivery tracking, which DFFH collates in its monthly care services report. These reports, which provide a statewide picture of brokerage spending, show that CSOs and ACCOs passed 74 per cent of brokerage funding onto carers from November 2020 to June 2021.

As Figure 3E highlights, Anglicare and VACCA underspent brokerage while Uniting Vic.Tas’s (Uniting) spending matched DFFH’s target. During this audit, we saw DFFH discuss brokerage underspending with Uniting and Anglicare. It encouraged the agencies to be more generous and proactively ask carers about their support needs. However, DFFH did not discuss with the agencies why they had not met its initial brokerage target and how this issue could be fixed.

We interviewed Anglicare, Uniting and VACCA to understand their challenges in meeting DFFH’s target. They all told us that low referrals from DFFH make it difficult to meet their target. One agency told us it purposefully tries not to overspend brokerage so funding is available for new clients.

FIGURE 3E: Brokerage spending by agency from October 2020 to June 2021 (as a percentage of DFFH’s target)

| Agency | Brokerage spent |

|---|---|

| Anglicare | 84% |

| Uniting | 103% |

| VACCA | 41% |

Source: VAGO, based on DFFH information

DFFH does not know if it is providing timely and customised financial support to carers

DFFH makes kinship placement support brokerage available to carers that are not eligible for First Supports. KETs administer these funds, which are intended to support and stabilise placements—particularly placements that are at risk of breaking down. From 1 March 2018 to 9 November 2021, DFFH spent $15.24 million on kinship placement support brokerage.

The kinship engagement manager in each DFFH division monitors kinship placement support brokerage. However, this monitoring only tracks spending and not the impact brokerage has had on a placement.

DFFH gives its divisions a suggested template to track spending, but it does not require them to use it as long as they record the:

- list of items or services purchased

- amount of items purchased from each category

- amount of brokerage used

- number of kinship households that have received brokerage

- number of children placed in a kinship household that receives brokerage.

These mandatory reporting fields do not let DFFH assess the impact brokerage has had on a placement. For example, how long it took a carer to access brokerage or if it met their support needs.

We also found that the level of detail recorded for these fields varied. For example, while divisions are meant to list the items or services purchased, many spreadsheets have blank cells or refer to hard-copy receipt numbers.

![]() We’ve been promised different things by different case managers at different times … it’s just been mixed messages the whole time.’

We’ve been promised different things by different case managers at different times … it’s just been mixed messages the whole time.’

means that DFFH cannot tell if this type of brokerage is providing timely and customised support to carers in line with the model’s objectives.

Carers are confused about what financial support is available

We met with 16 kinship carers who receive First Supports and/or case-contracting services from Anglicare, Uniting, VACCA and Bendigo and District Aboriginal Co operative.

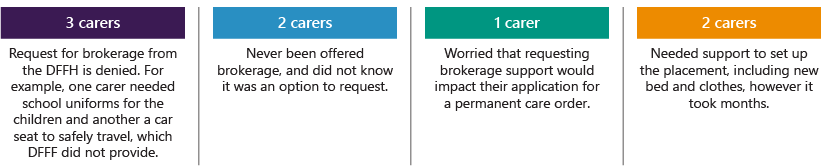

As Figure 3F shows, half of the carers felt it was difficult to access financial support from DFFH, CSOs and ACCOs at the right time. The other half of carers did not comment on this.

FIGURE 3F: Difficulty accessing financial support

Source: VAGO.

While our audit methods did not include verifying these claims, they indicate how difficult it can be for some carers to access financial support.

DFFH’s 2021 carer census, which 564 kinship carers responded to, supports these experiences. The census found that 52 per cent of carers were unaware of DFFH’s flexible funding.

4. Providing long-term stable homes

Conclusion

DFFH does not systematically measure and report on the outcomes of new model to see if it provides quality homes for the approximately 7,000 children in kinship care.

This means that DFFH does not know if it is supporting children in kinship care. It also means that DFFH may not be able to identify risks and provide support in a timely way.

This chapter discusses:

4.1 Understanding the new model’s impact

We assessed how DFFH monitors if children in kinship placements:

- have access to health, education and social opportunities

- are in stable homes

- are reunified with their parents where appropriate.

Access to health, education and social opportunities

DFFH’s regular reporting on kinship care and child protection does not have measures to assess if children are living in quality placements.

For example, DFFH’s statewide reporting on the OOHC system does not have indicators to measure if children living in kinship placements are:

- accessing health services and receiving medical treatment

- enrolled in and attending school or early childhood education

- accessing social opportunities.

Additionally, while CRIS includes records to show if a child is enrolled in school or early childhood education, these records do not:

- show if the child is regularly attending school or early childhood education

- always include information about the child’s participation in health and social opportunities as part of their case plan.

This lack of information on children's access to health, education and social opportunities prevents DFFH from getting meaningful insights to inform its policies and improve operational decisions.

Stable homes

One of the aims of the new model is to promote stability and reduce the likelihood of children entering into residential care.

However, DFFH has not determined what a stable placement is, collected baseline data to compare placements to, or assessed its progress against intended outcomes.

This means that DFFH cannot show if the model is achieving its objectives. It also does not understand how the new programs introduced in the model, such as First Supports, may be impacting the stability of kinship care placements.

Our file review

A permanency objective can be preserving the kinship family, reunifying the child with their family, adoption, permanent care or long-term OOHC.

An unplanned exit is when a placement ends earlier than originally planned.

We reviewed a random selection of 72 CRIS case files to understand if the new model is supporting stable placements.

When managing a kinship care case, a child protection practitioner must list a permanency objective in the case plan, which DFFH then endorses. At the time of our file review of post-2018 placements, we identified 46 of the 72 (64 per cent) placements that ended. Of these 46 cases, 19 (41 per cent) either did not meet their permanency objective or did not have an endorsed case plan.

We also assessed if the proportion of completed kinship placements that had unplanned exits has changed since DFFH introduced the new model in 2018.

Figure 4A shows that there has not been a meaningful change in the number of unplanned exits since 2018. This may indicate that despite introducing programs like First Supports, the new model has not improved the stability of placements.

FIGURE 4A: Proportion of completed kinship placements that had an unplanned exit since 2018

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data.

Reunification with parents

Reunifying parents with children, where appropriate, is one of the new model’s objectives. DFFH treats reunifications as a measure of placement quality.

We used CRIS data to examine the proportion of children in kinship care who were reunified with their parents before and after the new model was introduced. As Figure 4B shows, this has declined slightly since 2016.

FIGURE 4B: Placements that ended in reunification compared to new placements from 2016 to 2021

| Year | Placements that ended | Placements that ended reunification | Percentage of placements that ended reunification |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 3,934 | 1,486 | 37.8% |

| 2017 | 4,294 | 1,769 | 41.2% |

| 2018 | 4,886 | 1,773 | 36.3% |

| 2019 | 5,668 | 2,088 | 36.8% |

| 2020 | 5,464 | 1,939 | 35.5% |

| 2021 | 5,328 | 1,851 | 34.7% |

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data.

We also examined the proportion of children who re-entered care within 6 months after a reunification, which Figure 4C shows.

FIGURE 4C: Placements that ended in reunification compared to placements where children re-entered care following reunification from 2016 to 2021

| Year | Placements that ended in reunification | Children who re-entered care after reunification within 6 months | Percentage of placements ending in reunification that re entered care within 6 months |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 1,486 | 249 | 16.8% |

| 2017 | 1,767 | 294 | 16.6% |

| 2018 | 1,773 | 343 | 19.3% |

| 2019 | 2,088 | 349 | 16.7% |

| 2020 | 1,939 | 312 | 16.1% |

| 2021 | 1,851 | 199 | 10.6% |

Note: The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to a decrease in new placements in 2021, which may have also reduced the number of placements and reunifications that occurred in 2021.

Source: VAGO, based on CRIS data.

Overall, we did not find a significant change in the proportion of children who re entered care after being reunified with their parents. While DFFH aimed to lower re-entry numbers with the new model, a number of factors beyond the model can influence this, such as the safety and suitability of parental care.

4.2 Monitoring the new model’s outcomes

The Commission for Children and Young People did an inquiry to address concerns raised with it about OOHC.

The inquiry reported on the lived experience of children in the Victorian OOHC system.

The Commission for Children and Young People’s 2019 report In our own words and a 2016 review commissioned by DFFH both recommended that DFFH establish outcome measures for kinship care.

DFFH has 21 outcomes it wants to achieve with the new model over the short, medium and long term. However, it has not defined data collection methods or systematically monitored or reported on these outcomes. This is a missed opportunity for DFFH to demonstrate if the new model is improving the quality of kinship placements.

In 2018, DFFH's lapsing program evaluation showed that it was on track to achieve 3 of the short term and one of the medium-term outcomes at that time. The evaluation included early results against 6 of the short-term outcomes and 3 of the medium term outcomes.

DFFH runs a survey—the OOHC Outcomes Tracking survey—to get some insights into OOHC. However, this survey has limitations in how it presents information, which compromises DFFH’s ability to use the results to improve service delivery.

![]() … we have had no support, when I have tried to get help from DHHS they ignore.’

… we have had no support, when I have tried to get help from DHHS they ignore.’

In particular, the results of the OOHC Outcomes Tracking survey show some improvements in placement stability and children in OOHC attending school between 2016 and 2018. However, the 2016 and 2018 surveys do not differentiate between the different types of OOHC. This means DFFH is not able to identify which survey results that are relevant to kinship care.

DFFH also participates in a national survey by collecting Victorian data on the views of children in OOHC. However, the most recent The Views of children and young people in out-of-home care: Overview of indicator results from the second national survey report predates the new model and therefore cannot show if outcomes are improving.

4.3 Kinship carers' satisfaction with support

![]() Child protection worker has only visited once in 16 months. Financial assistance for childcare has not been forthcoming, despite assurances for over 3 months.’

Child protection worker has only visited once in 16 months. Financial assistance for childcare has not been forthcoming, despite assurances for over 3 months.’

DFFH ran 2 surveys in 2018 and 2021 to try to improve the support it provides to kinship, foster and permanent carers and inform its ongoing reforms in the sector.

We spoke to a small selection of kinship carers with diverse backgrounds to understand their lived experience and how supported they feel to provide quality homes for the children in their care.

Kinship carers’ satisfaction with DFFH support

DFFH’s 2018 survey found that only 25 per cent of kinship carers surveyed felt satisfied with the support DFFH provides and 58 per cent felt either dissatisfied or very dissatisfied.

DFFH conducted a carer census in 2021. The census had a broader scope than the 2018 survey because it included questions about all OOHC models. It also reached more kinship carers.

![]() We’ve been promised different things by different case managers at different times, for example, counselling and respite care, but none has been explored or looked at. It’s just never actioned. Total care packages—one person said yes, the other said no … it’s just been mixed messages the whole time’

We’ve been promised different things by different case managers at different times, for example, counselling and respite care, but none has been explored or looked at. It’s just never actioned. Total care packages—one person said yes, the other said no … it’s just been mixed messages the whole time’

The census found that while 28 per cent of kinship carers agreed they felt well supported by DFFH, 53 per cent either disagreed or strongly disagreed. These results show a slight improvement since 2018. However, it is concerning that more than half of the kinship carers surveyed in 2021 still felt dissatisfied with the support they receive.

The 2021 survey results also highlighted issues with child protection practitioners’ workloads. Child protection practitioners’ unreasonable workloads was a key finding of our 2018 report Maintaining the Mental Health of Child Protection Practitioners.

At that time, our analysis showed that practitioners had an average of 17 cases to manage. DFFH estimates that 12 is a suitable target. Between July 2020 and July 2021, the median case load hovered between 14 and 15, which is still above DFFH’s estimated target.

Additionally, VACCA advised us that ACCOs have a higher workload due to additional work to support cultural connections and health.