Principal Health and Wellbeing

Audit snapshot

Is the Department of Education (the department) protecting the health and wellbeing of its school principals?

Why this audit is important

As their employer, the department is responsible for protecting the health and wellbeing of all government school employees, including school principals, so far as is reasonably practicable.

Principals experience worse health and wellbeing outcomes than the general population, especially relating to stress, burnout and sleeping troubles. They also experience mental injury more often than other school staff.

Who and what we examined

We examined whether:

- principals’ health and wellbeing outcomes were improving over time

- the department was proactively identifying and addressing the root causes of poor principal health and wellbeing

- the department was monitoring, evaluating and reporting outcomes.

What we concluded

The department is not effectively protecting the health and wellbeing of its school principals.

The department has identified the key challenges that principals face. It has developed numerous strategies and initiatives to address them. Many principals use and appreciate these services.

However, they have not improved principals' health and wellbeing. The department needs to do more to reduce principal workload if it is to achieve better outcomes.

The department also needs to better monitor, evaluate and report on those outcomes. It will then better understand principals’ health and wellbeing and whether its initiatives are leading to desired outcomes.

What we recommended

We made 3 recommendations to the department to:

- further reduce principal workload

- better monitor, evaluate and report on principal health and wellbeing outcomes.

Video presentation

Key facts

Source: VAGO, based on department and Australian Catholic University data.

Note: principal-class employees include principals, assistant principals and liaison principals.

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the Department of Education (the department) and considered its views when reaching our conclusions. The department’s full response is in Appendix A.

Background: Principals’ health and wellbeing outcomes

The term ‘principals’ used throughout the report refers to Victorian government school principal-class employees (principals, assistant principals and liaison principals) unless otherwise stated.

Principals experience worse health and wellbeing outcomes than the general population. They also experience more mental injuries than other school staff.

Workload is the most significant cause of poor principal health and wellbeing

Principals reported working an average of 55 hours per week during school term and 21 hours per week during school holidays in 2022. Averaged over a year, they reported working 94 hours per fortnight – 18 hours more than their ‘ordinary hours of work’. There has been no material change in working hours since at least 2015.

WorkSafe Victoria (WorkSafe) maintains that working long hours can increase a person’s risk of heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, burnout, depression and anxiety. Principals’ long working hours correlate strongly with their high levels of stress, burnout and sleeping troubles compared to the general population. The lack of change in their working hours correlates with the trend in their health and wellbeing outcomes.

The department’s initiatives are not improving principal health and wellbeing outcomes

In its Principal Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2018–21 (PHWB Strategy) and advice to government during the same period, the department established a set of outcomes to assess whether its initiatives were working.

The department stated that the initiatives would work at 2 levels:

|

At the individual level, the department stated it would … |

At the organisational level, the department stated it would … |

|---|---|

|

|

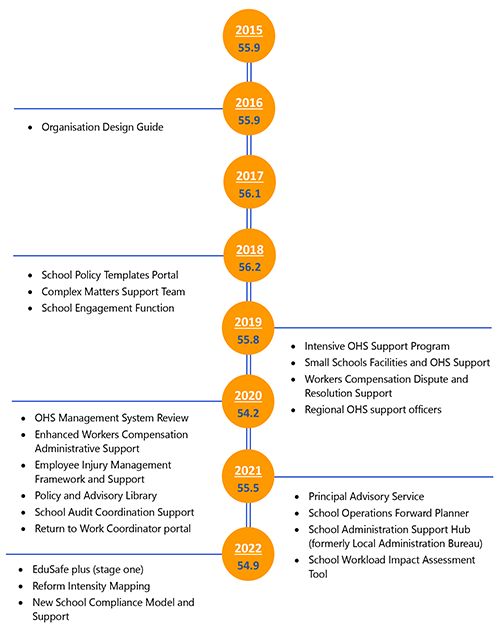

To improve principal health and wellbeing, the department has implemented 28 initiatives since 2018 (and one in 2016) (listed in sections 1.3, 1.4 and 1.5). Despite its efforts and investment, principals’ outcomes have not improved.

Additional measures of success

During and after piloting the PHWB Strategy initiatives, the department identified other indicators that it believed would demonstrate success. These included:

- principals being more willing to seek health and wellbeing support

- improved trust between the department, regions and principals

- the department developing a strong service culture.

The department needs to do more to reduce principals’ volume of work

Of the department’s 29 initiatives, 22 aim to reduce principal workload. Nearly all focus on increasing principals’ efficiency in undertaking required tasks rather than on reducing the volume of work.

Principals have welcomed the increased efficiencies, such as advice, templates, and streamlined systems and processes. In particular, they like initiatives such as the School Policy Templates Portal, the Policy and Advisory Library, the Complex Matters Support Team and the Principal Advisory Service.

The department should continue to identify and implement such initiatives. However, if it is to improve principals’ health and wellbeing the department needs to do more to reduce their volume of work.

Initiatives to reduce workload

The department needs to provide resources that undertake work on the principal’s behalf. The principal would continue to be accountable for the work.

The department has made some progress here, especially with 2 initiatives:

- The Organisation Design Guide (2016) aims to support principals to review and revise school structures and delegate more of their work to support staff (such as assistant principals, business managers and leading teachers).

- The opt-in School Administration Support Hub (SASH) gives small schools (enrolments under 200) finance and human resources (HR) support. It expands on the previous Local Administration Bureau (LAB).

To meaningfully reduce principal workload the department needs to increase access and support for these initiatives.

Recommendations about reducing principal workload

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education | 1. progressively rolls out an opt-in organisational design implementation project that:

(See Section 3.5) |

Accepted in principle by: Department of Education |

| Department of Education | 2. uses the School Administration Support Hub, or a similar approach, to support principals with administrative tasks by:

|

Accepted by: Department of Education |

The department’s monitoring, evaluation and reporting

The department can access the data it needs to monitor, evaluate and report on outcomes. As part of this audit, we were able to assess outcomes using this data.

However, shortcomings in the department’s approach and processes mean it does not fully understand how principals are faring. It also does not know whether its initiatives are improving outcomes.

|

Because the department … |

It cannot … |

|---|---|

|

consistently measure progress over time |

|

often monitors, evaluates and reports at an aggregate level |

isolate and identify the status of principals working in government schools. |

|

does not sufficiently coordinate monitoring, evaluation and reporting activities |

compile an accurate and comprehensive picture of principal health and wellbeing |

|

does not monitor, evaluate or report on workload reduction |

determine the effectiveness of its workload reduction initiatives, even though the department identifies workload as a root cause of poor principal health and wellbeing. |

The department does evaluate and report on output data on individual initiatives, such as the:

- number of principals using a service

- percentage of principals who are satisfied with a service.

It also commissioned 3 evaluations of its PHWB Strategy and employee wellbeing and operational policy (EWOP) reforms between 2019 and 2021. However, these evaluations drew on output data only. They did not evaluate or report on the individual- and organisational-level outcomes that the department committed to monitoring and reporting on.

Recommendation about monitoring, evaluation and reporting

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education | 3. develop and implement an evaluation framework that:

|

1. Audit context

School principals are key to creating teaching and learning environments that enable positive student outcomes. Their health and wellbeing is critical to ensuring that they can perform their roles effectively.

Principals experience worse health and wellbeing outcomes than the general population, including higher stress, burnout and sleeping troubles. They also experience a higher incidence of mental injury than other school staff.

The department employs principals and is responsible for government schools. It has a responsibility to protect principals’ health and wellbeing so far as is reasonably practicable.

Since 2018, the department has implemented 28 initiatives that aim to improve principals’ health and wellbeing.

In this section

1.1 The role of principals

Principals have complex and demanding leadership roles. Their core accountabilities distinguish their work from that of other employees in education. These accountabilities are to:

-

ensure the delivery of a comprehensive, high-quality education program to all students

- provide a child-safe environment in accordance with the Child Safe Standards

- be the executive officer of the school council

- implement the decisions of the school council

- establish and manage financial systems in accordance with department and school council requirements

- represent the department in the school and local community

- contribute to system-wide activities, including policy and strategic planning and development

- effectively manage and integrate the resources available to the school

- appropriately involve staff, students and the community in the development, implementation and review of school policies, programs and operations

- report to the department, school community, parents and students on the achievements of the school and of individual students as appropriate

- comply with regulatory and legislative requirements and department policies and procedures.

There are 3,424 principal-class employees (1,477 principals, 1,947 assistant principals) working across 1,557 government schools in Victoria (as of June 2022). They are responsible for the safety and wellbeing, and academic and professional performance of more than 645,400 full-time equivalent students and 51,920 teaching staff.

The department funds, administers and regulates the government school system. This includes employing and managing principals.

1.2 Principals’ health and wellbeing

Principals experience worse health and wellbeing outcomes than the general population, especially relating to stress, burnout and sleeping troubles. They also experience a higher incidence of mental injuries than other school staff, with mental injury, on average, making up 48 per cent of principals’ workers compensation claims. This is compared to 29 per cent and 20 per cent for teachers and non-teaching school staff, respectively.

Poor principal health and wellbeing can adversely affect students’ experiences, development and achievement by impacting their schools’ teaching and learning environments. It can also increase financial, social and psychological costs, as unwell principals may be more likely to take unplanned leave, claim compensation, resign or retire early.

1.3 Principal Health and Wellbeing Strategy 2018–21

The department recognised principal health and wellbeing as an issue in its 2017 Principal Health and Wellbeing Strategy: Discussion Paper. The discussion paper drew on principals’ workers compensation claims data, and data from the Australian Catholic University’s (ACU) annual Australian Principal Occupational Health, Safety and Wellbeing Survey (National Principal Survey). It highlighted principals’ poorer health and wellbeing relative to the general population and other department staff.

The department began advising government of principals’ relatively poorer health and wellbeing at least as early as 2018. It said that, compared to the general population, principals experience higher:

- job demands (1.5 times higher)

- emotional demands (1.7 times higher)

- emotional labour demands (1.7 times higher)

- burnout (1.6 times higher)

- stress symptoms (1.7 times higher)

- difficulty sleeping (2.2 times higher)

- cognitive stress (1.5 times higher)

- somatic symptoms (1.3 times higher)

- depressive symptoms (1.3 times higher)

It noted that 2.9 per cent of principals reported thoughts of self-harm.

In response to the poorer health and wellbeing outcomes experienced by principals, and following consultation on its discussion paper, the department developed its PHWB Strategy. This aimed to protect, promote and address mental and physical health and wellbeing outcomes for all Victorian principals. The PHWB Strategy aligns with the whole of Victorian Government (WoVG) Mental Health and Wellbeing Charter that was launched by the department in March 2017.

The department co-designed the PHWB Strategy with principals, principal peak associations, unions, academics and organisational psychologists. It drew on a range of literature, including the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace.

The PHWB Strategy was released in May 2018 with a first-year investment of just over $5 million to deliver 7 key pilot initiatives:

|

PHWB Strategy initiatives were … |

Which aimed to … |

|---|---|

|

School Policy Templates Portal |

reduce workload by providing template policies and practical guidance to support school compliance requirements |

|

Principal Mentoring Program |

reduce isolation and build social capital |

|

Principal Health Checks |

provide free and confidential proactive health consultations with general practitioners |

|

Complex Matters Support Team (CMST) |

minimise workloads and stress associated with managing and responding to complex cases |

|

Early Intervention Program |

give principals access to proactive professional support to prevent health and wellbeing risks escalating |

|

Proactive Wellbeing Support |

provide the opportunity to debrief with experienced psychologists and provide check-ins for new principals |

|

Regional Capability Development |

upskill the department’s regional corporate staff so they are better equipped to support principals in understanding and accessing the PHWB Strategy’s services. |

1.4 Safe and Well in Education Strategy 2019–24

In 2019, the department developed and implemented its Safe and Well in Education Strategy 2019–24 (SWE Strategy). This absorbed 6 of the PHWB Strategy’s 7 pilot initiatives (Regional Capability Development was discontinued). It added 2 new reform streams:

- Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) and Workers Compensation Reforms

- Operational Policy Reforms.

Under the SWE Strategy:

|

Initiatives implemented include the … |

Which aims to … |

|---|---|

|

Policy and Advisory Library |

support schools to easily and quickly find all department policy and related operational guidance and resources that apply to government schools |

|

Employee Wellbeing Response Team |

coordinate support to schools in relation to complex and high-risk health, safety and wellbeing issues |

|

safety at work for school staff initiative |

|

|

regional OHS support officers |

provide practical advice and hands-on OHS support (including support in relation to interactions with WorkSafe) to all schools |

|

Intensive OHS Support Program |

provide schools with intensive and targeted OHS support on a risk and needs basis |

|

enhanced workers compensation administrative support |

reduce administrative burden by transitioning hard copy manual tasks to electronic processes |

|

Return to Work Coordinator Portal |

support principals with staff workers compensation claims management and RTW planning |

|

OHS management system review |

support schools to manage and implement effective systems of (psychological and physical) safety |

|

workers compensation dispute and resolution support |

provide increased support to schools for workers compensation complaint resolution and legal action |

|

eduSafe Plus |

deliver a single digital system for reporting and management of employee and student incidents, OHS and workers compensation management. |

1.5 Other workload reduction and principal support initiatives

The department developed initiatives that were not part of the PHWB Strategy or SWE Strategy reforms. These were developed in response to identified need and principal feedback to reduce principal workload and enhance support to schools.

|

Initiatives implemented or planned for implementation include the … |

Which aims to … |

|---|---|

|

Principal Advisory Service |

reduce administrative burden by providing a service for principals to contact to ask policy and operational questions and seek support with reviewing and drafting their local policy documentation |

|

school engagement function |

coordinate and assess communications from the department to schools, streamlining and reducing the volume of communications as well as applying a workload reduction and red tape lens |

|

audit coordination function |

coordinate school audits/reviews to avoid multiple audit and review activities within the same period |

|

new school compliance model and support |

provide a supportive model for assessing schools’ compliance with the minimum standards for school registration |

|

OHS advisory service |

provide a telephone advisory service for support on the management of OHS issues, hazards, and risks |

|

Organisation Design Guide |

support principals to review and restructure teams, roles and responsibilities within the school with a view to delegating more work from the principal to support staff |

|

Small Schools Facilities and OHS Support Program |

support small rural and regional schools across Victoria with practical OHS and facilities support |

|

pre and post-OHS audit support |

provide audit support by OHS professionals to reduce principals’ administrative workload |

|

SASH (formerly Local Administration Bureau) |

provide support for small schools to reduce finance and HR administration workloads |

|

employee injury management framework and support |

to support schools with workers compensation injury management and claims management. This includes supporting principals with staff claims management and RTW planning |

|

School operations forward planner |

assist school leaders with workload management by detailing when operational and compliance tasks fall across the school year and allowing school leaders to track these tasks |

|

school workload impact assessment tool |

assist the department when designing new initiatives to consider school workload, systems, reporting and resourcing implications |

|

reform intensity mapping |

coordinate when reforms are reaching schools and what level of impact they have. |

1.6 The department’s principal health and wellbeing outcomes

The department identified a range of outcomes that it said would determine the success of its initiatives. In its PHWB Strategy, it wrote:

’How will we know we are achieving success over time? … The Department has developed a longer-term vision to evaluate both individual and organisational measures which have been linked to health and wellbeing. At the end of the three-year period [2018–21] we expect to see the extent to which these factors have improved to indicate an overall increase in principals’ health and wellbeing.’

The individual and organisational indicators are listed in the ‘What we found and recommend’ section above.

The department reiterated many of these outcomes in its advice to government between 2018 and 2021. It stated that its initiatives aimed to reduce the number and cost of principals’ workers compensation claims, reduce absenteeism, attrition and burnout, and improve principal recruitment and RTW rates.

In 2019, the Victorian Government invested $51 million over 4 years and $16 million ongoing annually to improve principal health and wellbeing.

2. Principal health and wellbeing outcomes

Conclusion

Principal health and wellbeing outcomes have not improved since the department started implementing its initiatives in 2018.

Victorian government school principals report similar outcomes to principals from Victorian non-government schools. Both report better health and wellbeing than government school principals in other states and territories.

In this section

2.1 Principals appreciate the department’s health and wellbeing initiatives

The department provides 29 services or resources that have aims that include improving principal health and wellbeing and targeting workload reduction.

The department surveyed all its principals in 2018 and 2019–20 to understand their use of, and experiences with, the PHWB Strategy pilot initiatives. In 2021 and 2022, the department surveyed users of specific services about their experiences. The survey data shows that, of the principals that use the department’s services and resources, most appreciate them (service use is discussed further in Section 2.2):

‘Well done! Lovely to know that our wellbeing is now being recognised as important/critical in order to better support the wellbeing of others.’

‘Excellent to see the variety of programs and support for principals who have a very complex job.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy pilot initiatives, 2018.)

Between 2018 and 2022:

- 89 per cent of survey respondents indicated that the Early Intervention Program had met their needs

- 93 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that the Proactive Wellbeing Support was useful

- 89 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that the Principal Mentor Program had reduced their feelings of isolation

- 74 per cent indicated that their overall experience with principal health checks was good or very good.

2.2 Principal health and wellbeing outcomes have not improved

Victorian government school principals report similar results for health and wellbeing (such as general health perception, stress and burnout) and job satisfaction as Victorian non-government school principals. Both score consistently higher on these indicators than principals from government schools in other states and territories.

However, all principals do significantly worse than the general population.

The department notes that principals report being close to ‘a tipping point’ when it comes to managing their health and wellbeing. It advised government that without appropriate intervention, the department faces a high risk of failing to meet its legal and ethical responsibility to provide the school workforce with safe and healthy workplaces.

It also advised government that there has been a steady increase in the number of principals’ OHS related work injury cases and increasing advocacy by the principal associations for the department to provide greater support for principals’ psychological and physical health and wellbeing.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

Since March 2020, Victorian government school principals have faced unique challenges, including:

- multiple and extended lockdowns

- continuously transitioning between remote, hybrid and onsite learning

- supporting contact identification and notification

- managing COVID-19 safe protocols

- overseeing the wellbeing of their staff, students and school community

- workforce shortages due to staff illnesses and absences related to COVID-19 requirements.

The department suggests that these challenges would likely impact principal health and wellbeing, workload, turnover, job satisfaction and many other aspects of the role. The department also suggests that the lack of improvement in principals’ health and wellbeing outcomes between 2020 and 2022 is attributable to these factors.

However, despite the challenges, principals reported their best health and wellbeing outcomes, and the lowest levels of workload pressures, in the 2 years most affected by COVID-19, 2020 and 2021. Victorian non-government school principals, who were equally affected by COVID-19, also show no deterioration in their health and wellbeing outcomes, and no increase in workload pressures, over the same period.

Organisation-level outcomes

Workers compensation claims have not reduced

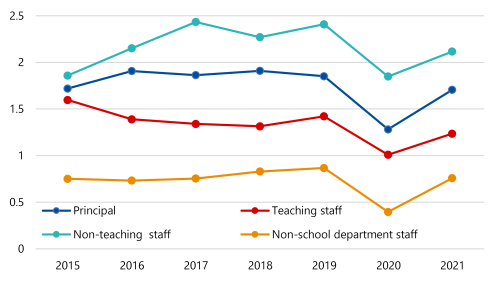

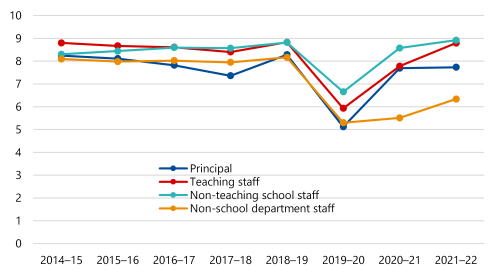

Figure 2A shows that there has been no sustained reduction since the department started implementing its initiatives in 2018.

Figure 2A: Annual workers compensation claims per 100 full-time equivalent staff, 2015–21

Source: VAGO, based on WorkSafe claims data 2015–21.

There was a sharp reduction in compensation claims in 2020 across all cohorts. The reason for this is unclear. It may be linked to COVID-19 when staff were spending more time at home or otherwise away from colleagues and school communities. However, if this were the case, we would expect to see that trend continue in 2021, which was also affected by COVID-19. Given that it did not, it is difficult to identify the potential cause.

The marginal improvement in principals’ claims in 2021 relative to their 2016–19 average follows the same trend as the other cohorts. This means that the reduction is likely part of a broader trend and the department’s initiatives are unlikely to be responsible for it.

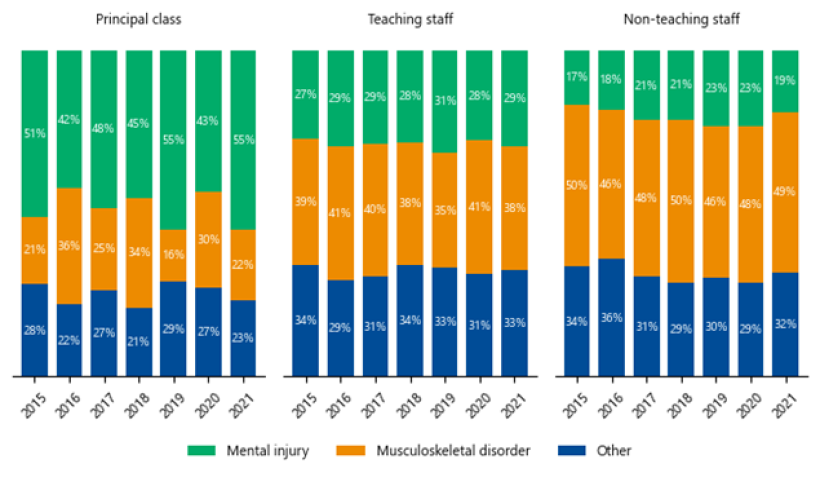

Mental injury claims are significantly higher than for other school staff

Figure 2B shows that mental injury was consistently the highest cause of principals’ workers compensation claims between 2015 and 2021. It made up almost half (48 per cent) of all claims.

By comparison, mental injury makes up an average of 29 and 20 per cent of teachers’ and non-teaching school staff claims, respectively.

Figure 2B: School staff workers compensation claims by injury type, 2015–21

Source: VAGO, based on WorkSafe claims data 2015–21.

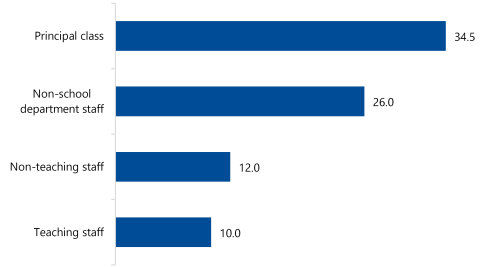

Figure 2C: Department staff median annual workers compensation leave days, 2015–21

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s data 2015–21.

Figure 2C shows that principals have, on average, the most annual workers compensation leave days. This is likely due to their higher incidence of mental injury. Cases of mental injury take longer on average to return to work than other injury types.

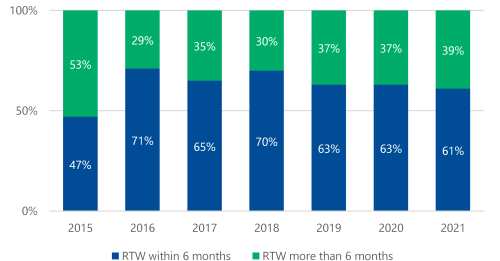

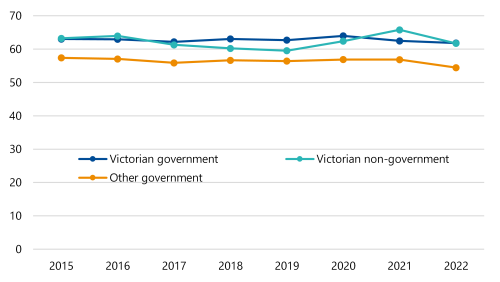

RTW rates have not increased

The department uses RTW within 6 months as one of its performance measures. Figure 2D shows that the percentage of principals returning to work within 6 months has remained steady over time (with annual fluctuations).

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s data 2015–21.

The department advises that there was greater complexity in RTW for principals during 2020 and 2021 due to COVID-19 disruptions. The department notes that returning a principal to work when they would have faced unprecedented challenges, such as the shift to remote teaching and learning, the increased need for principals to support student and staff wellbeing, and the need for principals to enforce vaccination requirements, could have been detrimental to their recovery, especially if they were suffering from mental injury.

Sick leave has not decreased

Figure 2E shows that principals’ sick leave (which the department labels ‘unplanned absenteeism’) remained steady over time, apart from the reduction in 2020. That may have been due to COVID-19, as discussed under Figure 2A. Principals’ sick leave followed a similar trend to the other cohorts, indicating that the department’s initiatives have had no influence on this outcome.

Figure 2E: Sick leave days by all cohorts, FY 2014–15 to 2021–22

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s eduPay data, 2015–22.

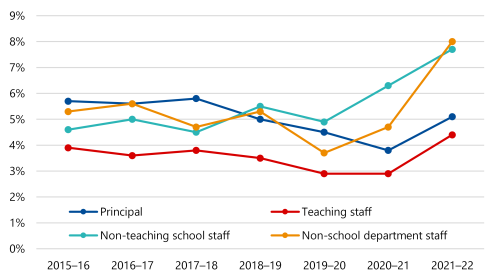

Principal attrition has not decreased

Figure 2F shows principals’ attrition rate (net loss of staff, which the department calls turnover) declined by 2.1 per cent between 2018 and 2021. It increased again in 2022. Without a sustained decrease, and given that it follows a similar trend to that of teachers, we cannot link declining attrition to the department’s initiatives. This is especially so when all other indicators have remained steady.

Figure 2F: Attrition by all cohorts, FY 2015–16 to 2021–22

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s eduPay data, 2015–22.

We note that the department’s principal attrition data does not include those who leave to take up another role within the department, such as a teaching role. This means the department’s principal attrition rates are understated.

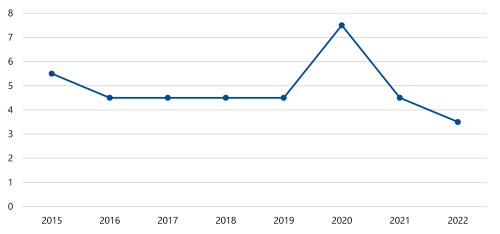

Principal role attractiveness has not increased

Figure 2G shows that the median number of principal role applications has remained steady over time, except for the spike in 2020. This coincides with the outliers identified in other datasets and discussed under Figure 2A.

Figure 2G: Median number of principal applications per vacancy, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s Recruitment Online data, 2015–22.

Job application rates considered alongside the steady attrition rates in Figure 2F indicate that principal role attractiveness has not improved. Principals VAGO spoke to, feedback provided to the ACU and the department’s analysis of the issue suggest that role attractiveness is, in fact, deteriorating. Experienced principals reported feeling that the role has changed over time, and that the role’s new requirements make it less attractive than when they had commenced their principalships.

‘If I knew what I know now I wouldn’t have gone down this track [of becoming a principal] … due to [the] workload and mental health and stress on a daily basis, from managing expectations of families, also of community, society, and [the department].’

(Principal feedback to VAGO 2022.)’We have four assistant principals and a lot of principal role opportunities, but no one wants to take it on – this has changed over the last few years.’

(Principal feedback to VAGO 2022.)‘I believe the expectations of principals are ridiculously high and many of my colleagues are quite stressed and anxious. I will be retiring in the next couple of years, and I certainly would not like to be a beginning principal given the amount of work, expectation and accountability that the role demands.’

(Victorian government school principal comment provided to the ACU’s National Principal Survey, 2021.)

The department advised government in 2021 that the principal role was becoming less attractive and that workload and work–life balance were key contributing factors.

Individual-level outcomes

ACU’s National Principal Survey

The ACU collects data on individual-level health and wellbeing outcomes for principals through its annual National Principal Survey. The survey began in 2011 and is the longest running survey of its type. It is also one of the most comprehensive longitudinal datasets of principal leadership across the world.

The survey collects, analyses and reports on school and personal demographic information, as well as principals’ quality of life and psychosocial coping. We have used the ACU’s data to assess changes in principals’ individual-level health and wellbeing outcomes over time.

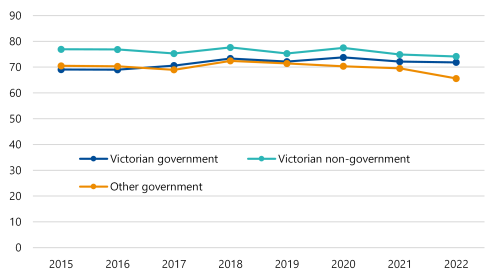

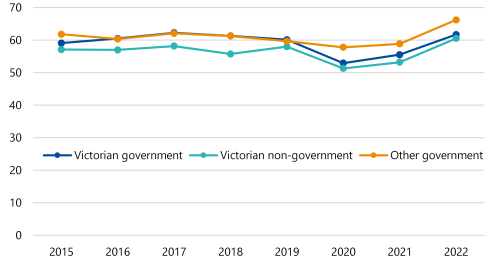

Perceived health and wellbeing has not improved

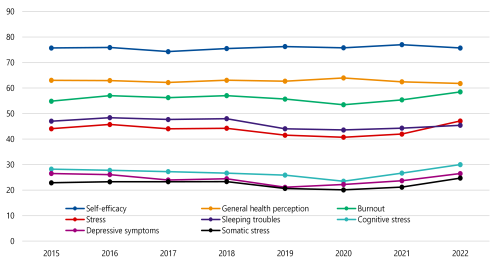

Figure 2H shows that principals’ perceived health and wellbeing has remained steady over time.

Figure 2H: Principals’ perceived health and wellbeing scores, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU’s National Principal Survey data, 2015–22.

Figure 2I shows that principals’ health and wellbeing sub-indicators have also remained steady over time.

Figure 2I: Principals’ health and wellbeing sub-indicators, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU’s National Principal Survey data, 2015–22.

Note: ‘Self-efficacy’ and ‘general health perception’ are positive indicators (higher scores are better). The other indicators are negative (lower scores are better).

Victorian government school principals report similar scores for general health perception and health and wellbeing sub-indicators as Victorian non-government school principals. Both have consistently reported better scores across all health and wellbeing indicators than government school principals in other states and territories since at least 2015.

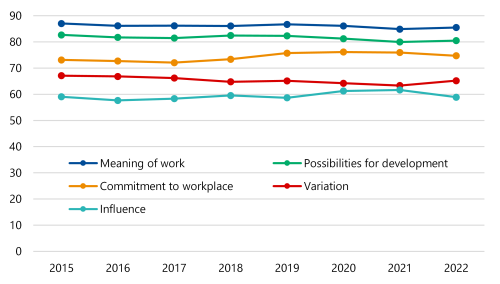

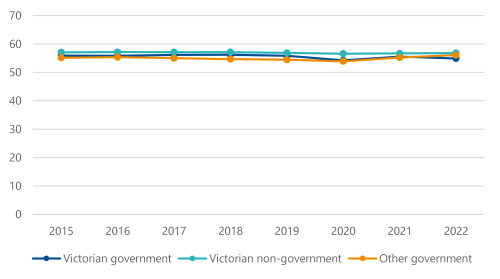

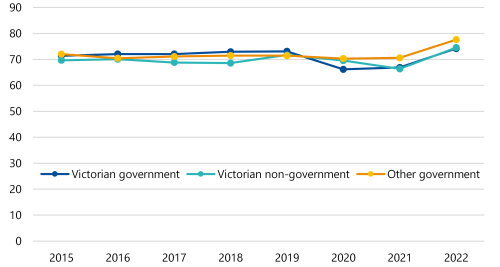

Job satisfaction has not improved

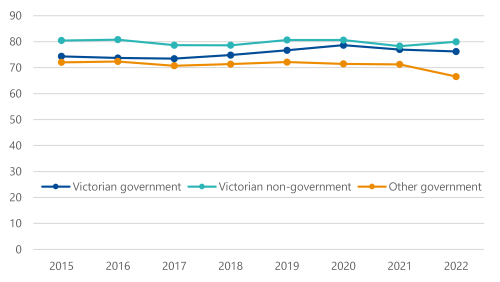

Figure 2J shows that there has been no material improvement in principals’ job satisfaction over time.

Figure 2J: Principals’ job satisfaction scores, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU’s National Principal Survey data, 2015–22.

Victorian government school principals report marginally lower job satisfaction than Victorian non-government school principals. Both have reported consistently better scores than government school principals from other states and territories.

Employee engagement has not improved

As the department has no direct measure of employee engagement, we assessed 5 related indicators.

Figure 2K: Principals’ employee engagement scores, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU’s National Principal Survey data, 2015–22.

Figure 2K shows that principals’ employee engagement scores have remained steady over time. There is a marginal improvement of 2.6 points in ‘commitment to the workplace’ between 2017 and 2022, however the same trend applies to other principal cohorts (graphs not shown here). This means that the department’s initiatives are unlikely to be responsible for this.

Additional indicators

During and after piloting the PHWB Strategy initiatives, the department identified other measures that it believed would demonstrate success. These included:

- greater willingness of principals to seek support to manage their health and wellbeing

- improved trust between the department, regions and principals

- the department developing a strong service culture.

Willingness of principals to seek support has been mixed

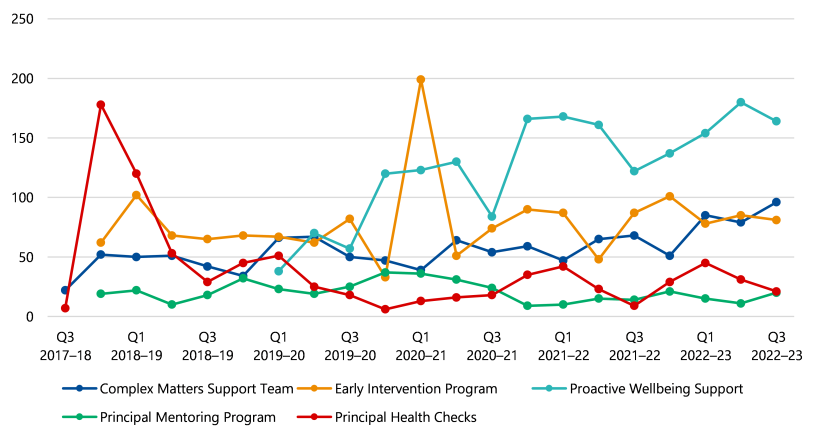

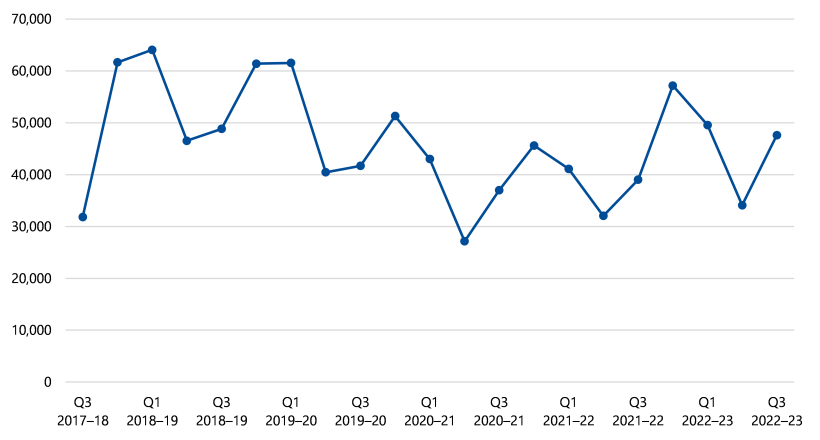

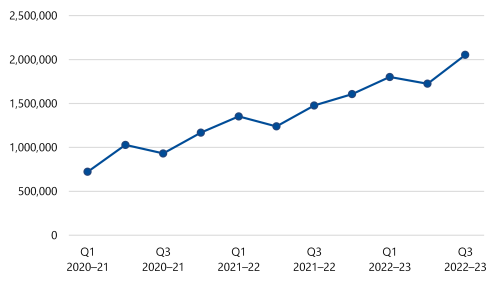

Service use data (see figures 2L, 2M and 2N) shows that 3 of 7 health and wellbeing and workload reduction initiatives have seen increased use: the Complex Matter Support Team, Policy and Advisory Library and Proactive Wellbeing Support, which increased with expanded eligibility. The others have remained stable.

Figure 2L: Quarterly principal health and wellbeing service use, 2017–18 to 2022–23

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s services usage data, 2017–18 to 2022–23.

Note: Complex Matters Support Team is a measure of the number of cases engaged.

Early Intervention Program is a measure of the number of referrals made to the Program.

Proactive Wellbeing Support is a measure of the number of completed sessions.

Principal Mentoring Program is the number of ‘pairings’.

Principal Health Checks is the number of checks performed.

Figure 2M: Quarterly School Policy Templates Portal page views, 2017–18 to 2022–23

Source: VAGO, based on the department services usage data, 2017–18 to 2022–23.

Figure 2N: Quarterly Policy and Advisory Library page views, 2020–21 to 2022–23

Source: VAGO, based on department data, 2020–21 to 2022–23.

A department-commissioned evaluation in 2021 noted that, ‘[the department] indicates some [services] are underutilised’. The evaluators cite as reasons for this:

- a lack of time for principals to participate

- a prevailing culture within the principal-class that typically defaults to ‘shouldering the load’ rather than seeking support

- principals’ sense of guilt accessing supports not readily available for many of their staff who principals view as needing it more.

Principals VAGO spoke to also cited a lack of time to engage with these services.

Trust between principals and the department

There has been no material increase in trust between principals and the department.

The department’s external evaluators found in 2021 that:

'There is reportedly increased trust and confidence that [the department] is focused on supporting principals and school leaders in their role. Principals’ perspectives have shifted significantly to viewing ”central as a supportive body rather than the dark side”.'

The suggestion that the department’s initiatives have increased trust between the department and principals is not supported by ACU National Principal Survey data, as Figure 2O shows.

Figure 2O: Trust between principals and their management, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU’s National Principal Survey data, 2015–22.

Figure 2O shows that Victorian government school principals report a marginally lower level of trust than Victorian non-government school principals, and a marginally higher level of trust than other government school principals.

The evaluation commissioned by the department bases its finding of increased trust on qualitative feedback from the principal associations and unions that it engaged with as part of its research. The survey data showing no increase is based on responses from between 250 and 650 Victorian government school principals each year.

The department’s service culture has improved

The department has made strong progress in developing and delivering health and wellbeing services for principals. Principals have appreciated those services and made good use of them.

Figure 2P: Number of times principals accessed health and wellbeing services between 2018 and 31 March 2023

| Service | Number of times principals accessed service |

|---|---|

| Early Intervention Program | Over 1,332 |

| Principal Health Check | 807 |

| Proactive Wellbeing Support | 499 |

| Complex Matters Support Team | 488 |

| Principal Mentoring Program | 407 |

Source: VAGO, based on department figures.

A department-commissioned evaluation of its PHWB Strategy published in 2019 found that:

‘Principals highlighted their satisfaction at the timely service they received through some of the initiatives, in particular from the [school] policy templates portal team and the complex matter [support] team.’

The department‘s 2021 evaluation also found that the department was making good progress in developing a strong service culture for principals:

‘[The department] has made significant progress expanding the suite of services and initiatives available to principals and other school staff under the Reforms … In general, there is a view that there are now more supports provided that not only look after principal health, safety and wellbeing, but also provide principals with the knowledge and tools required to manage, support and help staff to cope more effectively with stressful conditions.’

The department’s improved service culture is supported by principal feedback, such as:

‘… to know that this support for Principals is available is nothing short of amazing. Thanks again and really appreciate that the [department] have introduced this service, this is the kind of support we need.’

(Assistant principal feedback to the department on its Principal Advisory Service, 2021.)'We love PAL [Policy and Advisory Library]. It has been the best tool for schools to find the topic overview, policies and resources all together in one place. We consider PAL to be a single source of truth in front facing school land.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its Policy and Advisory Library, 2022.)

The 28 initiatives the department has implemented since 2018 also demonstrate the improvement in its service culture.

3. Workload, health and wellbeing

Conclusion

Instructional leadership is a form of school leadership that places teaching and learning at the forefront of school decision making. It has an intentional focus and demonstrated impact on continuous improvement in quality teaching and learning.

Workload is the most significant cause of poor principal health and wellbeing. Administrative tasks, compliance obligations and government initiatives are disproportionately contributing to principals’ workloads. Many principals work long hours, which impacts their health and wellbeing and reduces their time for instructional leadership.

The department identifies workload as a root cause of poorer principal health and wellbeing and has 22 initiatives in place to reduce it. Principals appreciate the services the department provides and have indicated that some save them time when undertaking particular tasks.

The overall volume of principals’ work has not reduced. The department has attempted to address this through several initiatives, but more needs to be done if the department is to reduce workload to the extent needed to improve principals’ health and wellbeing.

In this section

3.1 Workload is the most significant cause of poor principal health and wellbeing

Principals consistently identify workload as the most significant cause of their poorer health and wellbeing. They have communicated this in various ways:

- directly to the department through surveys

- to VAGO through focus groups

- to department-commissioned evaluators

- to principal peak associations and unions

- to the ACU through its National Principal Survey.

Comments include:

‘Most of these [PHWB Strategy] initiatives address symptoms, not causes. If [the department] is serious about principal health and wellbeing, they really need to seriously address the real problem – WORKLOAD!!!'

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy pilot initiatives, 2018.)‘There needs to be significant work done into Principal Workload, the principal cause of [a] significant proportion of Health and Wellbeing issues.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy initiatives, 2019.)

In 2022, a sample of 258 principals ranked ‘sheer quantity of work’ as their number one source of stress, followed by 2 other sources that relate to workload: ‘lack of time to focus on teaching and learning’ and ‘government initiatives’ (see Figure 3A).

The scores principals allocated to ‘sheer quantity of work’ increased marginally between 2021 and 2022. This suggests no reduction or improvement in workload (the ACU only started recording sources of stress from 2021).

Figure 3A: Sources of stress for principals in Victorian government, other government, Victorian non-government and all schools in 2022

| Sources of stress | Victorian government | Rank | Other government | Rank | Victorian non-government | Rank | All | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheer quantity of work | 8.14 | 1 | 8.30 | 1 | 7.84 | 1 | 8.18 | 1 |

| Lack of time to focus on teaching and learning | 7.80 | 2 | 8.14 | 2 | 7.73 | 2 | 7.95 | 2 |

| Government initiatives | 6.84 | 3 | 6.91 | 8 | 5.88 | 11 | 6.53 | 9 |

| Mental health issues of students | 6.80 | 4 | 7.58 | 4 | 6.62 | 5 | 7.27 | 4 |

| Expectations of the employer | 6.79 | 5 | 7.43 | 7 | 5.98 | 10 | 7.02 | 7 |

| Student-related issues | 6.73 | 6 | 7.48 | 6 | 6.45 | 6 | 7.16 | 6 |

| Teacher shortages | 6.71 | 7 | 7.67 | 3 | 6.90 | 4 | 7.33 | 3 |

| Mental health issues of staff | 6.64 | 8 | 7.48 | 5 | 7.00 | 3 | 7.20 | 5 |

| Resourcing needs | 6.44 | 9 | 6.78 | 10 | 6.00 | 9 | 6.52 | 10 |

| Parent-related issues | 6.19 | 10 | 6.88 | 9 | 6.06 | 8 | 6.66 | 8 |

| Poorly performing staff | 5.41 | 11 | 6.57 | 11 | 6.30 | 7 | 6.29 | 11 |

| Complaints management | 5.07 | 12 | 5.88 | 12 | 4.94 | 13 | 5.60 | 12 |

| Critical incidents | 4.97 | 13 | 5.63 | 13 | 4.64 | 15 | 5.35 | 13 |

| Financial management issues | 4.82 | 14 | 4.80 | 16 | 4.97 | 12 | 4.82 | 16 |

| Lack of autonomy/authority | 4.64 | 15 | 5.45 | 14 | 4.43 | 17 | 5.15 | 14 |

| Interpersonal conflicts | 4.32 | 16 | 5.05 | 15 | 4.86 | 14 | 4.89 | 15 |

| Inability to get away from school/community | 4.13 | 17 | 4.49 | 17 | 4.53 | 16 | 4.58 | 17 |

| Declining enrolments | 4.09 | 18 | 4.07 | 18 | 3.80 | 19 | 3.99 | 18 |

| Union/industrial disputes | 3.54 | 19 | 3.48 | 19 | 3.95 | 18 | 3.47 | 19 |

Source: ACU National Principal Survey 2022.

The department identifies workload as a root cause of poor principal health and wellbeing through key documents, including its PHWB Strategy, Safe and Well in Education Strategy 2019–24 (SWE Strategy) and advice to government between 2018 and 2021:

‘The [PHWB] Strategy builds upon the work commenced by the new School Delivery Unit. The establishment of the unit acknowledges the workload pressures experienced by principals and represents a significant cultural shift.'

(PHWB Strategy)

In 2018, the department advised government that principals were reporting reaching a ‘tipping point’ in their efforts to manage their workload. The principals said it was having a detrimental impact on their health and wellbeing.

The department advised government that these claims were supported by the steady increase in the number of principals’ OHS-related work injuries, as well as increasing advocacy from principal associations about principals’ workloads and their effect on health and wellbeing.

The department is also aware of other causes of poor principal health and wellbeing, such as teacher shortages and mental health issues of students. The department is addressing these issues through programs and initiatives that sit outside its principal health and wellbeing initiatives. These include a ‘targeted initiative to attract more teachers’ and the Schools Mental Health Menu, which is a support program for students.

The department acknowledges that workload is the most significant cause of poor principal health and wellbeing. The department’s PHWB Strategy and SWE Strategy aim to reduce other risks to principal health and wellbeing such as work-related violence. They target key drivers of positive mental health, including:

- psychological and social support

- organisational culture

- growth and development

- physical safety.

3.2 Workload is increasing

Principals' official duties centre around 52 major accountabilities set out in Schedule B of their employment contracts. While Schedule B has not changed since 2016, principals report increases in specific components that contribute to their increasing workloads. These include:

- increases in compliance requirements relating to OHS and workers compensation

- increases in general administration

- changing government and school community expectations around what a principal's role is.

Some principals note that the increases in workload are occurring in areas that they consider to be 'low value-adding'. These take them away from their core, and most value-adding, responsibilities, such as instructional leadership.

’Support is great to treat symptoms but the workload continues to increase and take me away from [my] core purpose – instructional leadership, thus the cause doesn't go away.ְ’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy initiatives, 2019.)‘Great [PHWB Strategy] initiatives but it is continuing increases in demand from [the department] in governance tasks that create stresses in the first place.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy initiatives, 2020.)

The department acknowledges an increasing workload for principals. It advised government in 2018 that the number and complexity of incidents principals are required to report and manage has ‘increased vastly’ in recent years. It also advised that, at the same time, the administrative time associated with being accountable for staff and student health and safety has ‘increased exponentially’ for principals.

The department advised government in 2018 that principals had been reporting increasing rates of physical and mental health-related harm. It noted that key contributing factors include:

- the growing amount and severity of complex student behaviours

- increased pressure from parents and advocates

- managing growing student enrolments and corresponding staff numbers.

The health impact of a high workload

In 2022, the ACU’s National Principal Survey found that principals worked an average of 55 hours per week during the school term and 21 hours per week during school holidays.

When averaged over a year, principals reported working an average of 94 hours per fortnight. This is 18 hours per fortnight more than the ‘ordinary hours of work’ (76 hours) for a full-time principal-class employee.

WorkSafe notes that working long hours and/or an imbalance between the demands of someone’s job and the personal and work resources provided to support a person to manage these demands can result in work-related fatigue. Work-related fatigue can increase a person's risk of heart disease, diabetes, high blood pressure, burnout, depression and anxiety.

Principals’ long working hours correlate strongly with their disproportionate experiences of burnout, sleeping troubles and stress compared to the general population.

Principals have told VAGO, the ACU and the department about the impact of working long hours on their health and wellbeing:

‘I would love the focus to be on reducing or managing workload. I find myself constantly struggling to get through everything and therefore working 12 hours per day (14 sometimes), 6 days per week.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy pilot initiatives, 2018.)’Workload – how can I complete my role in 76 hours per fortnight?’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy pilot initiatives, 2018.)‘I have real concerns about the direction of Principal Class roles and expectations on educators in general. In 20 years, the significant increase in workload, stress and emotional and physical demands to the role have come to a head. With Principal class working in excess of 60 hours a week and expected to work through holidays, it certainly makes it difficult to maintain both good physical and mental health...’

(Victorian principal comment provided to the ACU’s National Principal Survey 2021.)

The department is aware of the impact that workload can have on principals' health and wellbeing. It advised government in 2018 that over the preceding 5 years, 19 principals were identified as a high risk for potential self-harm and/or had already self-harmed or been institutionalised. It advised government that this had been consistently raised as a matter of concern by all principal peak associations.

In 2021, the department also advised government that there is emerging evidence about the impact of workload on psychological health and safety. It reported that WorkSafe considers workload to be a psychosocial factor causing workplace injury.

3.3 Workload drivers and the department’s response

Administrative tasks, compliance obligations and government initiatives take up a disproportionate amount of principals' time, leaving them less time to focus on instructional leadership and contributing to their poorer health and wellbeing.

Administrative tasks

The volume and breadth of administrative tasks that principals do takes up a substantial amount of their time.

Administrative tasks can be considered as all the activities related to ‘leading the management of the school’. They are often unplanned, ad hoc and variable in nature. They contribute to the disrupted pattern of the typical day of a principal during school hours. They can include tasks like organising student assessment papers and scheduling tests, organising and promoting school events, and coordinating student enrolment processes.

Research commissioned by the department between 2014 and 2019 found that principals were spending between 15 and 18 per cent of their total time on administrative tasks. It notes that in 2019, principals spent more time on administrative tasks than on curriculum, teaching and performance, budget, strategy and planning, and governance and policy activities. It also notes that there had been minimal change to this over the preceding 5 years.

Principals have consistently expressed these views:

‘It is disappointing that the [PHWB] strategy deals with the principal and personal coping. There is still a massive need to reduce the system-level admin that just grows and grows. That is the aspect that I find so overwhelming. Don’t give me a pay rise, give me additional admin support.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy pilot initiatives, 2018.)‘WORKLOAD – INCREASING ADMINISTRATION roles and tasks are increasing. There is not enough time and support to do what matters most.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy initiatives, 2019.)

The ACU, through its National Principal Survey 2021, identified administrative burden as a key workload concern among principals:

‘Qualitative comments reported concerns about increasing bureaucratic and compliance work. There is frustration with administrative work that does not improve student learning.’

The department acknowledges administrative tasks as a key workload burden for principals. It advised government in 2018 that surveys show that the average Australian secondary principal spends 47 per cent of their time on administrative tasks and just 17 per cent on teaching-related activities. The discrepancy between the 47 per cent reported to government and the 15 to 18 per cent found by department-commissioned research shows that the department does not have an accurate understanding of the amount of administrative work that principals undertake. It does indicate, however, that even a conservative estimate shows that it is too high.

The department notes that principals’ core business is achieving excellence in teaching and learning, and they should not be distracted or overwhelmed by administrative burden. In 2021, the department advised government that the volume of administrative and compliance activities now managed by schools is presenting challenges at the local school level. It noted that not only are these activities an inefficient use of a principals’ skills and expertise, and a distraction from the learning needs of their students, but they are also a cause of significant occupational stress.

The department’s response to principals’ administrative workload

The department is trying to reduce principals’ administrative workload through several initiatives that it has progressively implemented since 2018.

The School Policy Templates Portal provides schools with 49 templates that they can adapt to their own settings. It also provides guidance and advice on each topic. This aims to:

- reduce principal and school workload in the area of policy development and save principals time by eliminating the need for them to write their policies from scratch

- reduce the stress associated with ensuring the policy content is accurate and meets compliance requirements.

The department advises that between its launch in 2018 and 3 May 2023, there were 973,402 page views of the School Policy Templates Portal. Overall, principals have provided positive feedback on the Portal. They say that it saves them time and ensures their policies are compliant with legal and regulatory requirements:

’The [school] policy template portal is excellent and has reduced my workload.’

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy pilot initiatives, 2018.)‘The school policy template [portal] is an excellent resource for schools.'

(Principal feedback to the department on its PHWB Strategy initiatives, 2019.)

The department's Complex Matters Support Team (CMST) is another initiative that aims to reduce principal workload. It provides a central point within the department to coordinate responses to complex matters raised by principals, such as those relating to parent/advocate complaints.

The department advises that between its establishment in 2018 and 30 September 2022, the CMST dealt with 558 cases. The CMST received mixed feedback early in its implementation, and feedback in the later years is from a small sample, but overall, the feedback has been positive.

’I am not sure I could have managed this situation without this service and have highly recommended this to colleagues since. From my point of view, this service is critical in both protecting principals’ health and wellbeing, and ensuring we are not losing quality leaders as a result of the more complex challenges we may face.’

(Principal feedback to the department on the CMST, 2022.)

Of the principal respondents surveyed between 2018 and 2022:

- 94 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that the CMST reduced their workload when dealing with a complex matter

- 98 per cent agreed or strongly agreed that the CMST reduced their stress when dealing with a complex matter

- 98 per cent indicated that they were satisfied with their overall experience with the CMST.

Compliance obligations

Compliance obligations (and the reporting, audit and review processes that accompany them) also take up a significant amount of principals’ time. The department advises that between 2019 and 2022, Victorian government schools were scheduled to undergo more than 7,000 reviews or audits from at least 12 department program areas. That is equivalent to approximately 1.2 audits or reviews per school each year. Given that individual reviews or audits can potentially take months to prepare for and close off, they can provide a significant workload for principals.

Principals have highlighted this in much of their feedback to the department, VAGO, and the ACU:

’Large compliance aspects such as school reviews take so much time – at least six months preparation and are stressful. The recommendations and feedback are quite often pre-determined from 10 or 15 initiatives the government want delivered’

(Victorian principal comment provided to the ACU’s National Principal Survey, 2021.)The role is not what it used to be. The demands are unrealistic and the support is next to none. The compliance and non-student focused tasks are distressing and not why educators were drawn to the industry.

(Victorian principal comment provided to the ACU’s National Principal Survey, 2021.)

The department acknowledges the burden that compliance requirements place on principals. It advised government in 2018 that schools face complex legislative, regulatory and policy requirements in all aspects of operations. It said that compliance with these requirements has become an increasingly time-consuming activity for school leadership that leaves less time for core educational leadership work.

The department’s response to principals’ compliance workload

The department has implemented several initiatives that aim to reduce the compliance burden on principals, especially in the areas of OHS, workers compensation and RTW, the Minimum Standards for school registration and the Child Safe Standards.

The Small Schools Facilities and OHS Support Program (SSP) is designed to support principals to complete their facilities and OHS requirements more efficiently, more often, and with greater compliance. To do this, participating schools have access to a SSP coordinator, project team, school maintenance plan portal and a vendor panel.

An evaluation of the pilot found that the SSP:

- increased principals’ facilities and OHS management capability

- reduced administrative burden

- increased completion and compliance

- improved budget use.

Some principals provided positive feedback on the SSP, including:

‘Many thanks for today, you made my heart sing! I feel everything is achievable with this kind of support. Many thanks my blood pressure should now be in the normal range.’

(Principal feedback to the SSP coordinator, 2020.)’These activities are always difficult to get done, organised, processed in the time they have available … the Coordinator has been so helpful and accommodating and her advice and support has been invaluable. What she doesn’t know, she will find out. She can get done in a couple of hours what it would take me at least a whole day, or more, to do. This has taken so much pressure off.’

(Principal feedback to the department, 2021.)

The program is now being made available to all small schools over 4 years and will also provide support for workers compensation claims made by staff at small schools.

The department also implemented a school audit coordination function in 2020 that manages how schools are scheduled for audits and reviews. It looks at scheduled audits and reviews from 12 department program areas and recommends when audits should be rescheduled or avoided to assist principals in managing their workloads. The department advises that in 2022 it reviewed over 9,000 proposed reviews and audits and recommended that approximately 1,500 be avoided for selection or rescheduled to a more suitable time, in support of school workload management.

Government initiatives

The number, complexity and pace of government initiatives is a key contributor to principals’ workloads. Principals particularly express frustration at what they consider to be inadequate consultation from the department on the amount of time and resources that they need to implement the initiatives.

Victorian government school principals ranked ‘government initiatives’ as their third-highest source of stress in the ACU National Principal Survey 2022. This is compared to eighth and eleventh for other government and Victorian non-government school principals, respectively. This sentiment has also been expressed through qualitative feedback:

’I think the education department often brings down initiatives through the school that we need to implement with limited support, resources and knowledge. The curriculum is already very crowded and despite this fact schools are expected to deliver just about everything that is stipulated by the department.’

(Victorian principal comment provided to the ACU’s National Principal Survey, 2021.)

‘I am frustrated by the lack of support by the department to resource my school adequately and the way I need to manage this and keep families and staff content or to buffer them from these issues … decisions are made by the department that directly impacts schools (e.g. the parent payment policy, the tutoring initiative, and the ICT devices) without consultation that schools need to manage quickly.’

(Victorian principal comment provided to the ACU’s National Principal Survey, 2021.)

The department acknowledges this issue in advice it gave to government in 2022. It stated that the department needs to do more to improve the coherence of new programs and initiatives to ensure that they account for existing reforms in the system.

It also advised that it needs to do more to address reform intensity. It noted that program design does not always sufficiently account for the operational realities of schools and regions. It identified the volume, pace and workload implications of new reforms as barriers to successful implementation.

The department’s response to the impact of government initiatives on principals’ workloads

The department started reform intensity mapping in 2022 to help schools better manage government reform implementation. The department advises that this work has been used by its various program areas and internal governance groups to help them understand the current workload intensity schools are managing. This will guide implementation planning for new or expanding programs. The department also advises that schools' workload intensity has been a key consideration during the development of incoming government strategic opportunities and government funding submissions for 2022–23 and 2023–24.

The department has developed a school workload impact assessment tool to help corporate staff and decision-makers consider the operational and resourcing impact of initiatives and programs on schools. The tool builds understanding of the impact of implementing initiatives, in conjunction with the rationale and benefits they are anticipated to bring. It helps department staff design initiatives that complement school operating environments and reduce schools’ workload and administrative burden. It is currently being trialled at budget bid, design and later stages prior to telling schools about initiatives.

3.4 Effectiveness of the department’s workload reduction initiatives

Workload has not reduced overall

Some principals have indicated that some of the department’s workload reduction initiatives, such as the School Policy Templates Portal and the Complex Matter Support Team, have reduced their workloads when performing tasks related to those initiatives. However, principals’ overall workloads have not reduced. The department’s initiatives have improved efficiency in some areas, such as in OHS and workers compensation, but they have not reduced the volume of principals’ work. This means that many principals are continuing to work long hours to acquit their responsibilities.

Figure 3B: Principals’ reported average weekly working hours, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU National Principal Survey data 2015–22.

The department advises that principals’ average working hours have been trending down since it started implementing its workload reduction initiatives. Figures 3B and 3C show that the department’s initiatives have had little to no effect on working hours. The high and stable trend in working hours correlates strongly with the static nature of principals’ health and wellbeing outcomes presented in Section 2.

Figure 3C: Principals’ average reported weekly working hours mapped against the department's workload reduction initiatives, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on the department’s initiatives and ACU National Survey data 2015–22.

Figure 3D: Principals’ quantitative demands scores, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU’s National Principal Survey data, 2015–22.

Quantitative demands assess how much a principal must achieve in their work. It assesses the difference between the number of tasks and the time available to perform the tasks in a satisfactory manner (the higher the value the more demanding the role).

Figure 3D shows that, after reducing in 2020 and 2021, Victorian government school principals’ quantitative demands returned to historical levels. From 2019, Victorian government school principals followed a similar trend to the other principal cohorts, especially Victorian non-government school principals. This supports Figures 3B and 3C in showing that the department’s initiatives have had no impact on principals’ workloads.

Figure 3E: Principals’ work pace scores, 2015–22

Source: VAGO, based on ACU’s National Principal Survey data, 2015–22.

Work pace assesses the speed at which tasks must be performed (work intensity). Figure 3E shows that, following a reduction in 2020 and 2021, Victorian government school principals’ work pace returned to historical levels. From 2019, Victorian government school principals’ work pace followed a similar trend to Victorian non-government schools (albeit with a sharper decrease in 2020), indicating that the department has not influenced this measure.

Principals' experiences support the workload data, as the department’s external evaluation of its PHWB Strategy and EWOP reforms found:

’Whilst principals genuinely believe [the department] is working for them through the supports delivered through the Reforms, it was consistently reported that a significant reduction in the overall workload expected of principals by the [the department] has yet to be observed.’

(External evaluation of the department’s PHWB Strategy and EWOP reforms, 2021.)

Current initiatives are unlikely to reduce principals’ workloads enough to improve health and wellbeing

The department’s current initiatives do not do enough to reduce the volume of principals’ work. Instead, most focus on supporting principals to do the same amount of work more efficiently.

Some of the initiatives involve providing support to principals in the form of advice and guidance, while others focus on streamlining systems and processes. The principal is still responsible for doing the work. Examples of these include the OHS Advisory Service, the Principal Advisory Service, eduSafe Plus, and the Return to Work Coordinator Portal.

Others, such as school audit coordination support, help some schools by postponing or cancelling an audit or review that they may be scheduled for, but those audits/reviews are generally undertaken at a later date or otherwise performed on other schools. It does not reduce the overall number of audits/reviews in the system.

An evaluation of the department’s SSP (which provided facilities and OHS support) demonstrates how a focus on efficiency without reducing work volume may not reduce principal workload. The evaluation found that, while the program made principals more efficient, it did not save them any time overall. This was because the increased efficiency led them to do tasks that they did not do before the pilot. They were spending the same amount of time on facilities and OHS but getting more done.

The initiatives that do save principals time have marginal impact.

Enhanced Workers Compensation Administrative Support is an example of this. The department estimates that automating the calculation of pre-injury average weekly earnings saves between 30 minutes and one hour per claim. Over an average of 1,038 claims, this process would save each school an average of 40 minutes per year. Principals report working an average of 468 hours per year above what the government deems their standard hours.

Principals would welcome any time-saving measure, no matter how small, and the department should continue to look for and support more efficient practices for principals. But it needs to modify its approach to more effectively reduce the volume of principals' work. Otherwise, principals are likely to keep having to work long hours, and their health and wellbeing is unlikely to improve as a result.

3.5 Reducing the volume of principals’ work

Organisational design

Organisational design is the process of aligning organisational elements with the school's strategic plan and operational (day-to-day) requirements. It is about how a school:

- groups responsibilities around work

- allocates decision making authority

- defines jobs

- binds teams together structurally to maximise their effectiveness

- translates the school's strategic plan into actions and results through the design of jobs and their relationships to one another.

The department has explored organisational design and the increased delegation of tasks from the principal to support staff as one way to more substantially reduce principal workload. As part of this, the department commissioned annual research between 2014 and 2019 to look at the different tasks that principals did throughout the day. The aim was to help principals better manage their workloads.

The research recommended that principals reduce the scope of their roles or the number of tasks that they do. They could do this by restructuring their schools to allow for more delegation from the principal to their leadership teams. The department developed an Organisation Design Guide in 2016 to support this work. The department also developed support materials in 2018 for its regional staff to assist principals in implementing the changes.

Despite the support and guidance developed for principals, school restructuring and increased delegation has not reduced principals' workloads. The researchers note in 2018:

‘Over the last four years, considerations have been provided on changes that individual principals can make to their own role, and to the school. Despite the tools and training that has been organised by the Department, there has not been widespread adoption of strategic change related to school structures. This is demonstrated through the consistent year-on-year results.’

Reasons for low uptake of the organisational design changes

The researchers suggest that workload pressures on individual principals may be stopping them from implementing changes. Our discussions with principals support this, with several citing a lack of time to engage with the Organisation Design Guide.

The department advises that there is a culture among principals of prioritising budget allocations for students and classroom delivery at the expense of school administration and leadership. It says that this is the primary reason for principals not implementing the recommended changes.

Some principals we spoke to confirmed prioritising budget allocations in this way. One reason they gave was that the school community expects them to prioritise the school budget for students and classroom delivery. It would be difficult for them to get school council approval to spend funds on principal support staff at the expense of student spending.

The department acknowledged these pressures in its 2018 advice to government. It stated that the current assumption is that schools will resource responses to principal health, safety and wellbeing issues from within their school budgets. It noted that there is school community pressure to direct the budget to teaching and learning opportunities for students.

Another reason principals cited was that they felt an obligation to their students to prioritise student needs over their own. They felt that they could not, in good conscience, spend money on additional support staff for themselves if it meant their students missed out on something they needed.

Promoting uptake of the recommended changes

The researchers maintain that, despite the low uptake, their organisational design and delegation recommendations are still relevant. They believe the department should explore ways of better promoting their implementation.

The department advised that it intends to actively encourage principals to allocate more funds from their budgets to support staff to help reduce their workloads. It also advised that its regional staff would support principals to implement the structural changes by using additional guidance it has developed.

While this may help, it does not address the lack of time that principals have identified as impeding their ability to make the changes. It also does not address the pressure principals feel from school councils and communities to prioritise student spending over the needs of the principal.

Another issue the department faces is that it does not know how many schools have implemented, or attempted to implement, the organisational design changes that its guide promotes. It has not monitored its uptake and impact. This means the department does not know whether the changes work in practice to reduce principals' workloads.

Changes to organisational design and increased delegation may help principals reduce their workloads. However, the department needs to better support its uptake and test the effectiveness of the changes before relying on them as a key workload reduction initiative.

School Administration Support Hubs

The researchers’ recommendations to the department regarding organisational design and delegation note that delegation could occur to the principal’s internal leadership team or to an external source. This could include a SASH.

The SASH builds on a local small schools initiative, the LAB, that was started in the 1990s by a group of schools in the Horsham area. Operating out of Horsham Primary School, the LAB provided schools shared finance and HR processing operations. It charged a fee based on student enrolment numbers, length of subscription and services requested.

The SASH helps small schools (currently those with fewer than 200 enrolments) that do not have a full-time business manager for operational tasks or the skills or time to do them. It does not replace a business manager but supports them and their principal with excess administrative work.

The SASH works on an opt-in basis and allows principals to choose from between one and 6 service streams. Principals can choose to use a service for anywhere between one term and 2 years.

The SASH team accesses the participating schools' internal systems remotely to undertake the selected tasks on their behalf. It is trained in the use of all the department’s relevant systems (such as CASES21 and eduPay). It understands all the department’s relevant policies, processes and requirements. Figure 3F lists the services that the SASH currently offers.

Figure 3F: Current SASH services

| eduPay/Recruitment Online | Cash budget | Financial | Local payroll | Student administration | Student Resource Package |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appointment of employees | Development of budget | Chart of Accounts maintenance | Hire/rehire of employees | Student enrolments | Short-term leave replacement |

| Cessation of employees | Budget entry/ maintenance | Monthly bank reconciliations | Cessation of employees | Injury data entry | Credit to cash/cash to credit transfers |