Access to Public Sector Information

Overview

Public sector information (PSI) is a powerful resource that could be better used to drive open government, innovation, commerce, and community engagement for the benefit of Victorians.

In responding to the 2009 parliamentary Inquiry into Improving Access to Victorian Public Sector Information and Data, government committed to transform the way the public sector provides access to its PSI by adopting an ‘open by default’ approach.

However, the agencies we examined are not providing the public with full and open access to the information to which they are entitled. This is largely because the critical foundation of comprehensive and sound information management practices has been neglected.

Ineffective whole-of-government leadership and governance of information management has failed to drive the significant cultural and operational changes needed to achieve open access to PSI.

Consequently, access to PSI has not significantly improved, falling well short of the government’s original intentions.

Access to Public Sector Information: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER December 2015

PP No 110, Session 2014-15

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Access to Public Sector Information.

The audit assessed whether selected agencies are effectively facilitating access to public sector information (PSI) and whether whole-of-government leadership and oversight has supported improved performance.

I found that the agencies we examined are not providing the public with the full and open access to the information to which they are entitled. While I identified areas that had been progressed, the foundation of comprehensive and sound information management (IM) practices have been neglected. This is crucial because agencies need to first understand and properly manage the information they hold before they can effectively facilitate public access.

Critical to explaining this outcome is the partial and compromised implementation of the IM framework government committed to in early 2010 and the subsequent ineffective whole-of-government leadership and governance of information management. As a consequence access to PSI has not significantly improved, falling well short of government's original intentions.

I have made seven recommendations. Five of these target improving IM for the agencies examined in the audit. The remaining recommendations call for the Department of Premier & Cabinet to take the lead in creating a whole-of-government framework that will effectively support and oversee significantly improved performance.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

10 December 2015

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Ray Winn—Engagement Leader Michelle Tolliday—Team Leader Celinda Estallo—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Dallas Mischkulnig |

The government's response to the 2009 Parliamentary Inquiry into Improving Access to Victorian Public Sector Information and Data (PSI Inquiry) recognised:

- the significance of the potential benefits from improving community access to public sector information (PSI) in terms of greater innovation, economic growth and improved transparency, accountability and public trust

- the need to develop, and for public sector agencies to apply, a whole-of-government information management (IM) framework so they can effectively manage and provide access to PSI

- the importance of establishing an online directory, where the public can search for and obtain information about the PSI held by government.

The response concluded that open access to PSI would foster creative, innovative and often unanticipated entrepreneurial activities when businesses and citizens are allowed to use PSI to create products and services. Open access also enhances engagement between citizens and government on critical policy issues leading to broad economic and social benefits.

The current government's policy platform is strongly aligned with using PSI more effectively to deliver economic growth, improved services and greater transparency. This is evident in the appointment of a Special Minister of State to oversee government transparency, integrity, accountability and public sector administration and reform.

Realising these significant and widely acknowledged benefits requires strong whole-of-government leadership to help public sector agencies reshape and transform their practices. Unless public sector agencies effectively manage the PSI they hold and create comprehensive directories to allow the public to search for and obtain it, this resource will remain largely inaccessible and underused.

The audit assessed whether, selected agencies are effectively facilitating access to PSI and whether whole-of-government leadership and oversight supports improved performance.

I found that ineffective whole‑of‑government leadership and governance has failed to drive the significant cultural and operational changes needed to achieve open access to PSI. The partial and compromised application of the government's IM framework is evidence of this deficiency.

In the context of these weaknesses it is not surprising that the three agencies examined in detail are not providing the public with full and open access to the information to which they are entitled. While none of these agencies had reached a level of maturity that fully facilitates access to PSI, I am encouraged by the progress of the Department of Health & Human Services and the State Revenue Office, and can see the potential for these agencies to reach maturity in the short term.

In light of the whole-of-government weaknesses, my conclusions and recommendations are likely to apply across the public sector beyond the selected agencies included in this audit.

Two recommendations for the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC) highlight its critical role in leading and overseeing the development and application of a whole-of-government IM Framework and improving compliance with the Freedom of Information Act 1982. The remaining five recommendations are designed to improve the practices of the three agencies in complying with current legislation and applying better practice IM principles and standards.

If acted upon effectively, these recommendations will provide the essential foundation for public sector agencies to give open access to PSI.

There is little prospect of delivering the significant benefits of open access if government's track record of a partial, siloed and compromised application is repeated. In practice, this means that Victorians are unlikely to experience the economic benefits and the enhanced, more transparent and accountable decision-making that open access to PSI can deliver.

I do not underestimate the challenges to develop and effectively apply the comprehensive IM framework that is needed. Our performance audits over the past 10 years have repeatedly found weaknesses with whole-of-government programs that were not adequately authorised, planned or coordinated.

This puts the onus on DPC to effectively oversee a comprehensive and rigorous approach to implementing the IM framework described in the government's response to the PSI Inquiry and in this report.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

December 2015

Audit summary

Background

All the information generated, collected, and funded by, or produced for government is known as public sector information (PSI). This includes structured data—traditional datasets that sit within databases—and unstructured data, or information, which includes all government records, emails, reports, briefings, photographs and more.

Governments around the world have committed to improving access to PSI to:

- improve service outcomes—by providing relevant agencies with the quality and scope of information needed to effectively and efficiently deliver services

- achieve greater accountability, transparency and engagement—by giving the community access to information to better understand agencies' performance

- achieve greater levels of innovation and economic growth—by allowing businesses and citizens to use this information to create products and services.

In responding to the 2009 Parliamentary Inquiry into Improving Access to Victorian Public Sector Information and Data (PSI Inquiry), government committed to transform the way the public sector provides access to its PSI by adopting an 'open by default' approach.

Critical to this approach was the development of a whole-of-government information management (IM) framework to help public sector agencies:

- adopt the default position of open access to all PSI available

- establish and apply systematic and consistent practices for categorising, storing and managing PSI, because agencies cannot effectively provide access to information that is not effectively catalogued, stored and managed

- only restrict access to PSI through the application of clearly defined criteria where this is required by law, contractual obligations, or national or state security

- promote and facilitate increased access to, and re-use of, Victorian PSI

- make information available at no or marginal cost using the least restrictive licensing arrangements.

Government also committed to develop a whole-of-government PSI directory so the public could know what information it held and how to access it.

Progress was dependent on a clear mandate to improve IM strong governance, and accountability through timely and comprehensive progress reporting to senior government representatives.

Successive governments have committed to improve access to PSI and transparency by improving freedom of information (FOI) legislation and practices, publishing government datasets, and publicly committing to open up government to greater scrutiny. Since the PSI Inquiry, providing open access to PSI—except where this would breach criteria showing that it would not be in the public interest—has remained a clear policy goal.

Government created a project sponsors' board to implement its response to the PSI Inquiry. By late 2011 the board developed the Public Sector Information Release Framework (PSIRF) covering government's commitment to implement a holistic whole-of-government IM framework.

By early 2012, the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF) assumed responsibility for implementing PSIRF. However, instead of proposing the framework for government endorsement, it advised government to proceed with only a partial application of PSIRF. The proposed policy—the DataVic access policy—mandated the release of data held by public sector agencies through a centralised data portal. Government endorsed the proposed policy and did not mandate that agencies establish and apply systematic and consistent practices for categorising, storing and managing PSI.

Over 2011 and 2012, the Victorian Government Chief Information Officers' Council (CIOC) endorsed and released a set of better practice IM principles and standards. While not mandatory, nor applicable to Victoria's entire public sector, they closely match those proposed under PSIRF.

Audit objective

We examined the IM maturity and approach to providing public access to PSI of the State Revenue Office (SRO), the Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) and the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP).

We examined their progress in facilitating access to PSI and whether whole-of-government leadership and oversight has supported improved performance in this area, specifically by DTF, the Department of Premier & Cabinet (DPC), the Public Record Office Victoria and the Department of Justice & Regulation.

Conclusions

The agencies we examined are not providing the public with full and open access to the information to which they are entitled.

While progress has been made in some areas, the critical foundation of comprehensive and sound IM practices has been neglected. Agencies need to first understand and properly manage the PSI they hold before they can effectively facilitate public access to that information.

This outcome is explained by the partial and compromised implementation of the IM framework originally envisioned by government. This left agencies without consistent practices for categorising, storing and managing PSI, which are essential for effectively facilitating access to it. Ineffective whole-of-government leadership and governance of IM has failed to drive the significant cultural and operational changes needed to achieve open access to PSI.

Consequently, access to PSI has not significantly improved, and falls well short of the government's original intentions.

Findings

Facilitating public access to PSI

The agencies we examined are not adequately facilitating access to their PSI. None of the agencies examined have implemented consistent agency-wide approaches to identifying the PSI that should be proactively released.

While comprehensive information asset registers are an essential tool for facilitating public access to their PSI, none of the sampled agencies publish these. DHHS is, however, close to publishing its newly created information asset register. It follows that government's clear commitment to a whole-of-government PSI register remains unfulfilled.

Agencies also fall well short of fully complying with their obligations under Part II of the Freedom of Information Act 1982, to publish registers of the information they hold.

The guidance issued in 2012 to improve this situation allowed for agencies to adopt a minimalist approach to publishing information indexes, and is unlikely to have improved agencies' performance.

DTF and contributing agencies cannot demonstrate that the expected benefits of the DataVic access policy have been achieved. These benefits were:

- stimulating economic activity through new, innovative services

- increasing productivity through better decision-making

- improving research outcomes

- delivering services more effectively and efficiently.

The work in developing the DataVic access policy and populating the centralised DataVic portal deals with a subset of PSI and is at a low level of maturity. The use of dataset quotas has resulted in the release of easy to access, often low value data and the splitting of some datasets to achieve quotas. One exception to this finding is DELWP's freely available spatial datasets—data that identifies the geographic location, size and shape of objects on planet Earth, which is usually stored as coordinates and topology. These are published in their entirety and include valuable information.

Agency information management

We assessed agencies' maturity with respect to CIOC's better practice principles and standards and rated them as being:

- 'formative'—the lowest level of achievement

- 'in development'

- 'progressing'

- or 'established'—operating in line with better practice.

The three sampled agencies have not reached a level of maturity where they effectively manage the PSI they hold. Progress has been slow, has been disrupted by machinery-of-government changes and a focus on responding to the DataVic access policy, and has not provided the public with quality tools to make the majority of their PSI discoverable.

We found that none of the sampled agencies had fully established practices consistent with CIOC's principles and standards, and that performance varied.

Department of Health & Human Services

DHHS is 'progressing' to better practice, with strong IM governance structures, clear senior level support and a comprehensive IM strategy that is integrated with its corporate objectives and planning.

However, it has experienced repeated delays in implementing many of its improvement initiatives due to machinery-of‑government changes, the Sustainable Government Initiative—which aimed to reduce the number of public sector staff across all departments—and more recently, the need to incorporate the former Department of Human Services' information holdings, which were substantially less mature.

This means that many of these initiatives have only just commenced or are in their early stages, and DHHS needs to maintain its current momentum to achieve a fully mature IM environment.

State Revenue Office

SRO is 'in development', having made positive progress toward a more open approach to sharing its information with the public. In 2012, SRO began making multiple changes to how it manages its PSI to better facilitate access to it. These included establishing essential IM governance arrangements and implementing an information custodianship model.

However, a number of initiatives still need to be fully implemented to effect the necessary improvements. We are confident that this is likely with continued effort and senior level support.

Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning

DELWP's approach to managing PSI is 'formative'. Like DHHS, DELWP has also been impacted by machinery-of-government changes and the Sustainable Government Initiative. However, it lacks even the foundational governance and oversight requirements needed to ensure effective public access to more than just its spatial data.

DELWP's spatial data has long been recognised for its high quality, and efforts to ensure that it is supported by mature and robust governance and management processes have made it one of Victoria's most valuable and highly used data sources. However, this is only a portion of DELWP's total PSI holdings, and it has not applied the same level of effort to other valuable PSI such as research documents, outsourcing service agreements, and risk and performance reports.

Whole-of-government leadership and oversight

There is an absence of whole-of-government leadership and oversight for implementing a comprehensive framework to enable access to PSI.

Changes in the leadership arrangements and the scope of the implementation of the government's response to the PSI Inquiry have been critical in shaping the failure to establish an 'open by default' approach to PSI.

The initial arrangements, with leadership provided by a senior, cross-government project sponsors' board, and the subsequent development of PSIRF, provided a solid foundation for delivering effective public access to PSI.

Following consultation with DPC, DTF informed government in August 2012 that the scope for PSIRF's implementation had been narrowed. This involved excluding the goals of increased transparency and accountability and focusing on innovation, greater productivity and improved service delivery. These goals would be pursued by releasing only datasets, rather than all PSI as intended.

Government signed off on this alternative to PSIRF—the DataVic access policy—however, DTF did not adequately explain the reasons for this change or the clear risks this created for meeting the goals and existing legislative requirements of providing open access to PSI.

Progress toward an 'open by default' approach includes the release of a whole-of-government intellectual property policy and a default form of licensing that allows for the easier re-use of PSI.

DPC also maintains a web portal to which agencies can link their published datasets, providing centralised access to the public <www.data.vic.gov.au>.

Despite this, in mid-2015 we found a fragmented and confused governance framework and a proliferation of numerous unconnected, overlapping and inconsistent plans. This sits in contrast to the advice from DTF and DPC soon after the government's response to the PSI Inquiry, which identified the need for strong oversight to achieve open access to PSI.

Whole-of-government leadership and oversight have been inadequate for developing and implementing a framework to effectively provide public access to PSI because:

- a single point of accountability for the intended framework was not maintained—IM oversight and leadership had been removed

- parts of the intended framework essential for achieving open access—such as developing and implementing systematic and consistent practices for categorising, storing and managing PSI—were left without authorisation and oversight

- advocacy efforts of CIOC to promote improved IM in a small number of agencies lacked authority and were ineffective in driving the necessary changes

- the implementation of just a portion of the government's commitment meant that only some of the components needed to provide open access have been progressed and reported on.

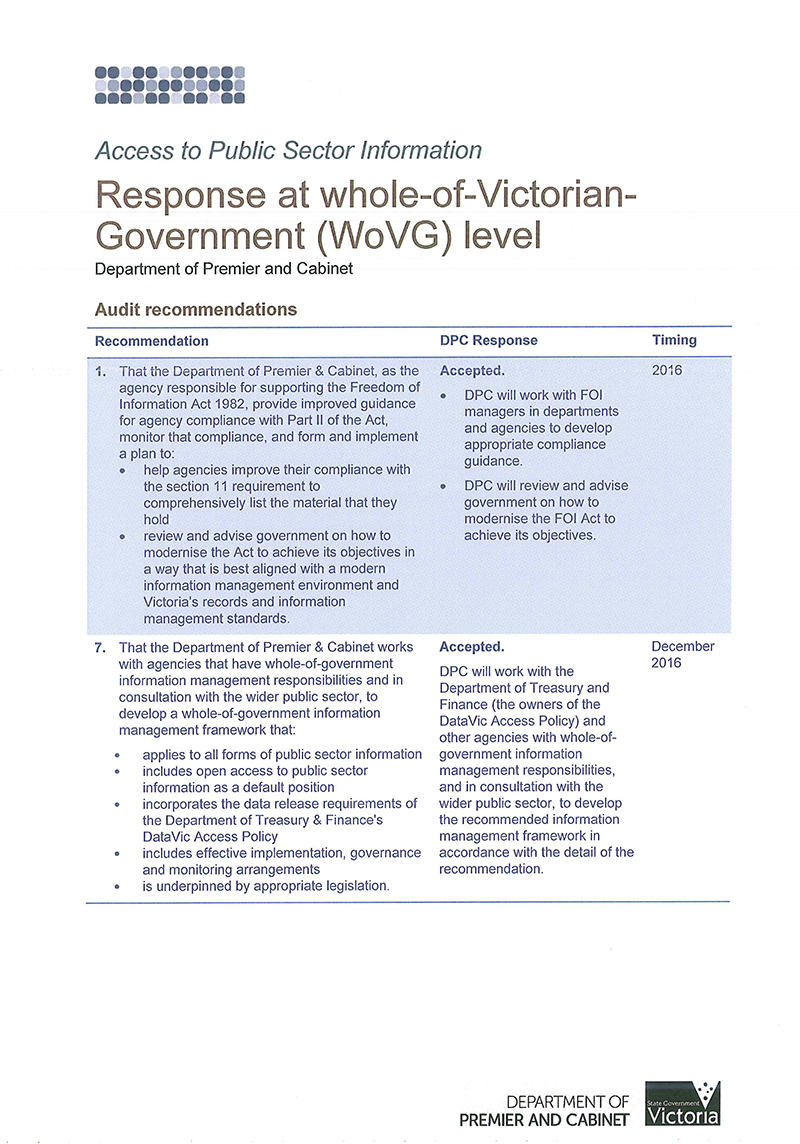

Recommendations

- That the Department of Premier & Cabinet, as the agency responsible for supporting the Freedom of Information Act 1982, provides improved guidance for agency compliance with Part II of the Act, monitors that compliance, and forms and implements a plan to:

- help agencies improve their compliance with the section 11 requirement to comprehensively list the material that they hold

- review and advise government on how to modernise the Act to achieve its objectives in a way that is best aligned with a modern information management environment and Victoria's records and information management standards.

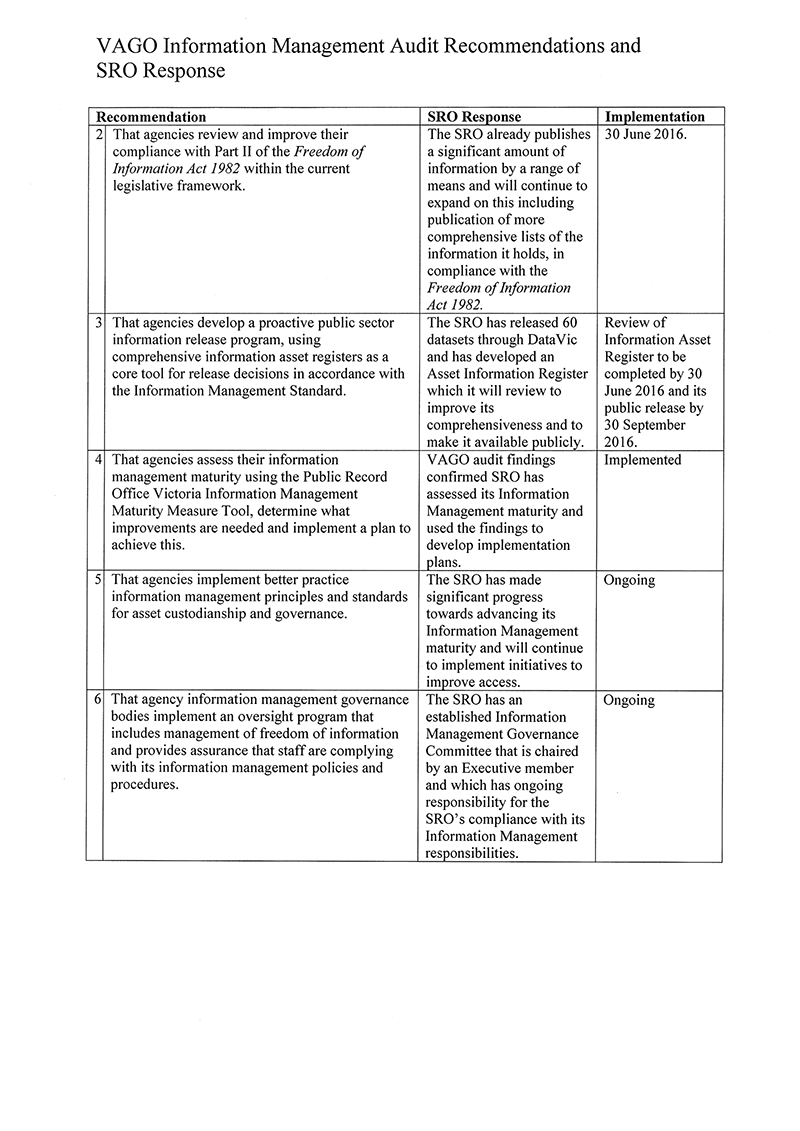

- That agencies review and improve their compliance with Part II of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 within the current legislative framework.

- That agencies develop a proactive public sector information release program, using comprehensive information asset registers as a core tool for release decisions in accordance with the Information Management Governance Standard.

- That agencies assess their information management maturity using the Public Record Office Victoria Information Management Maturity Measurement Tool, determine what improvements are needed and implement a plan to achieve these.

- That agencies implement better practice information management principles and standards for asset custodianship and governance.

- That agency information management governance bodies implement an oversight program that includes management of freedom of information and provides assurance that staff are complying with its information management policies and procedures.

- That the Department of Premier & Cabinet works with agencies that have whole-of-government information management responsibilities and in consultation with the wider public sector, to develop a whole-of-government information management framework that:

- applies to all forms of public sector information

- includes open access to public sector information as a default position

- incorporates the data release requirements of the Department of Treasury & Finance's DataVic access policy

- includes effective implementation, governance and monitoring arrangements

- is underpinned by appropriate legislation.

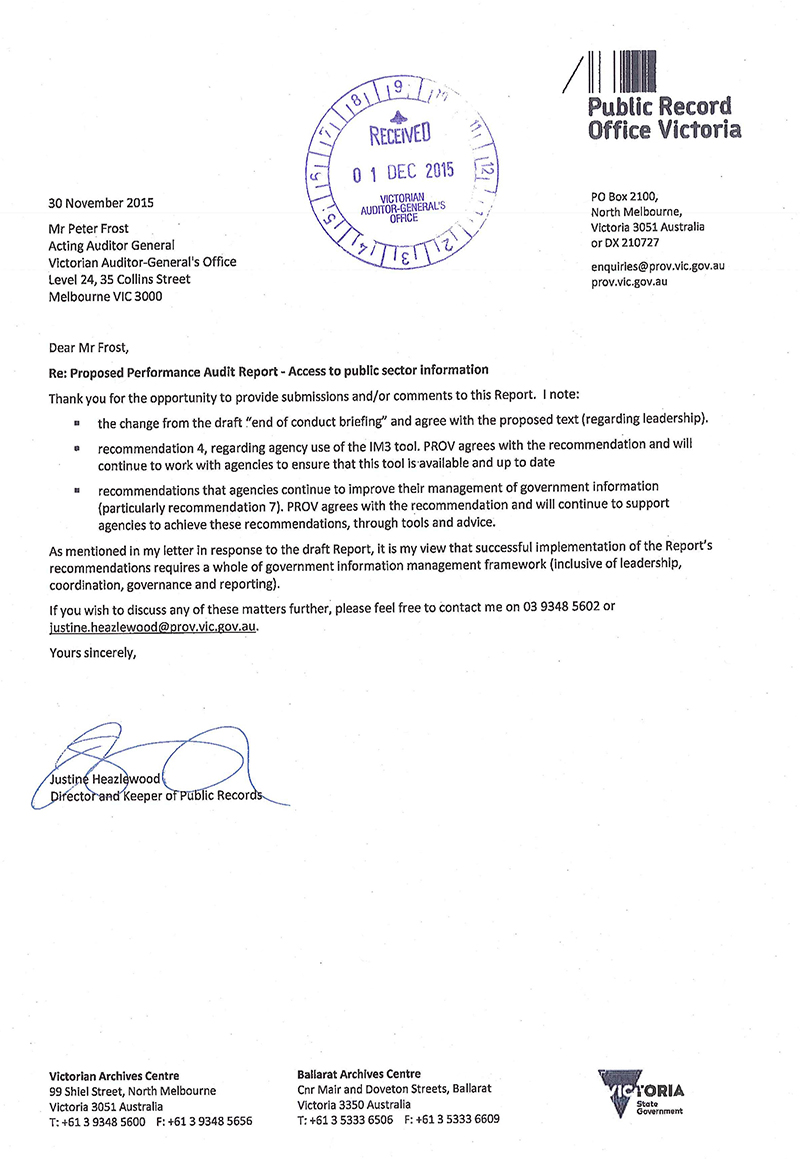

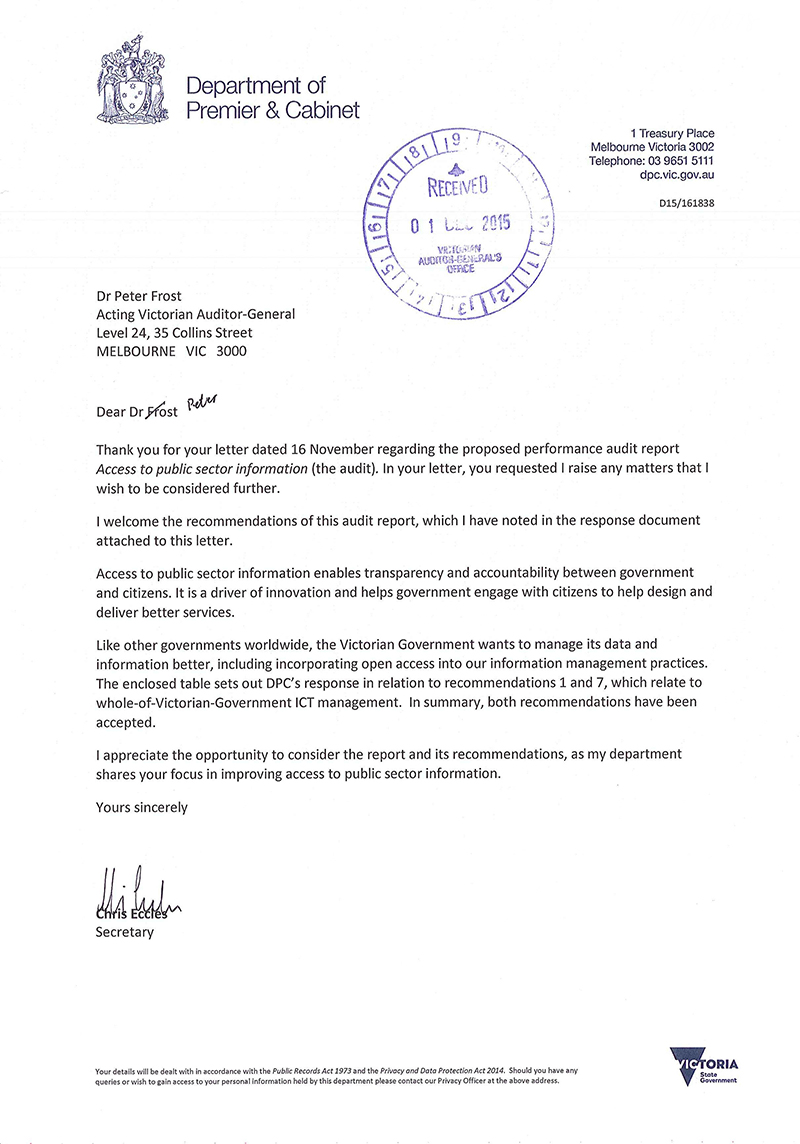

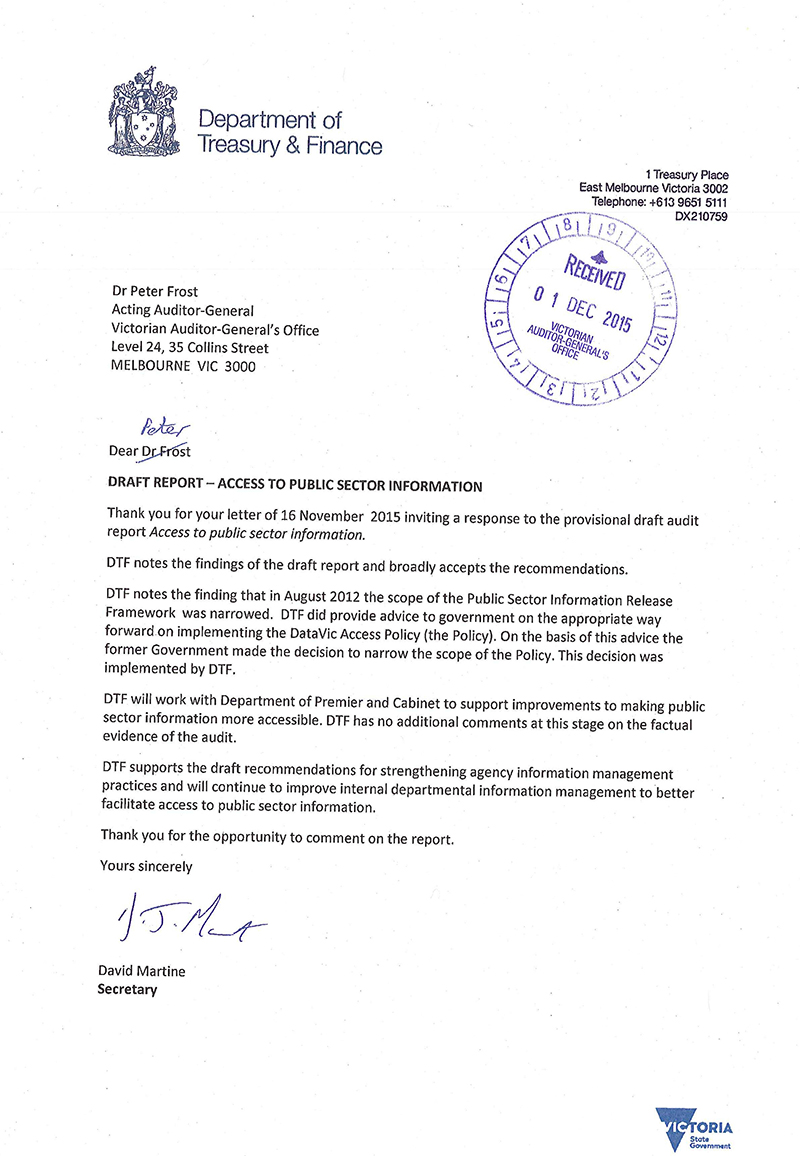

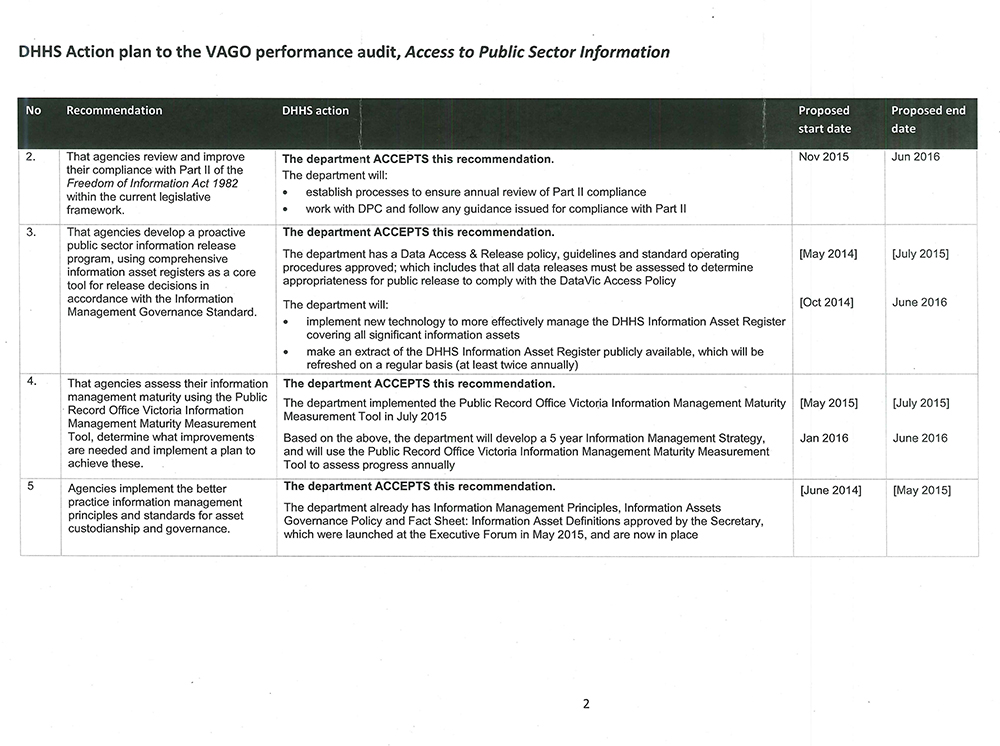

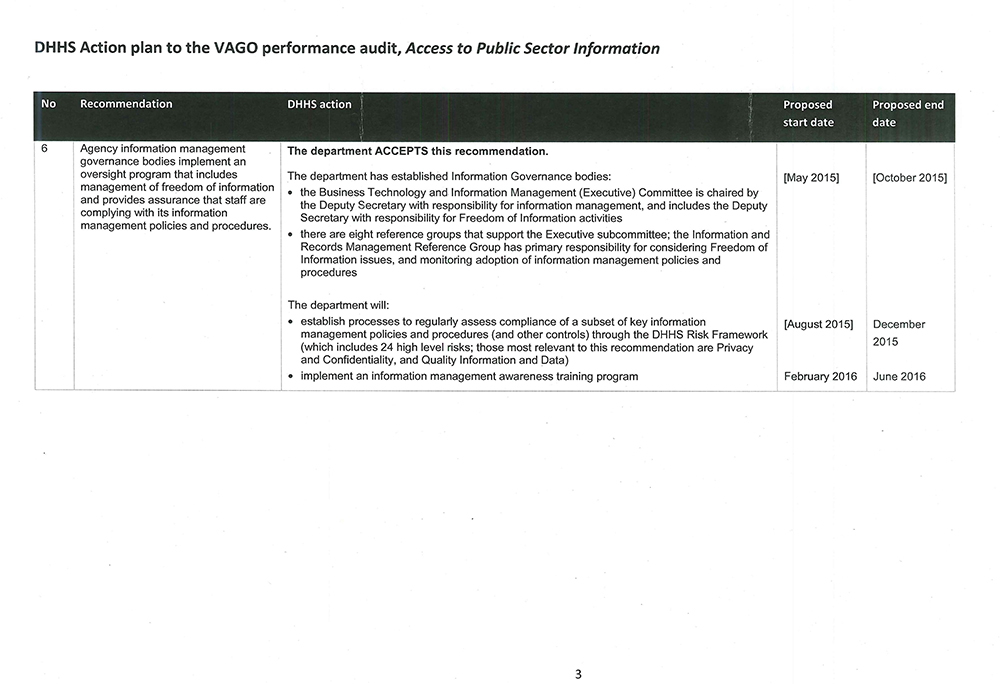

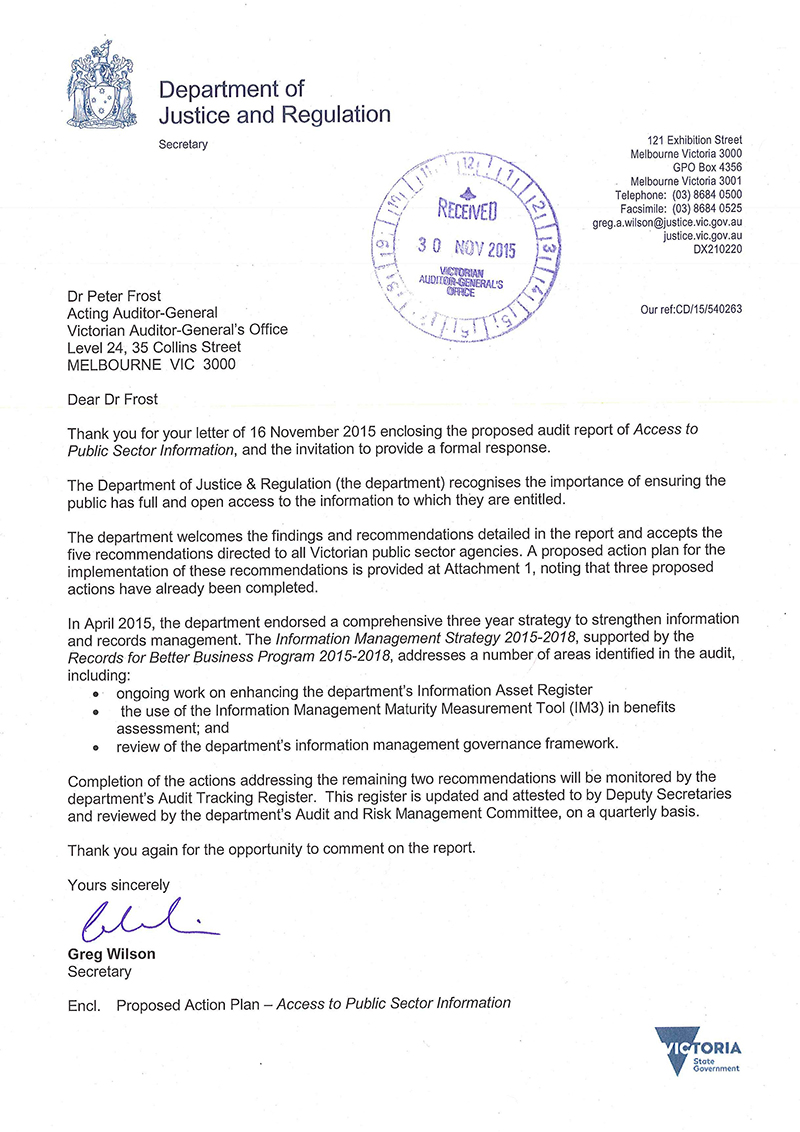

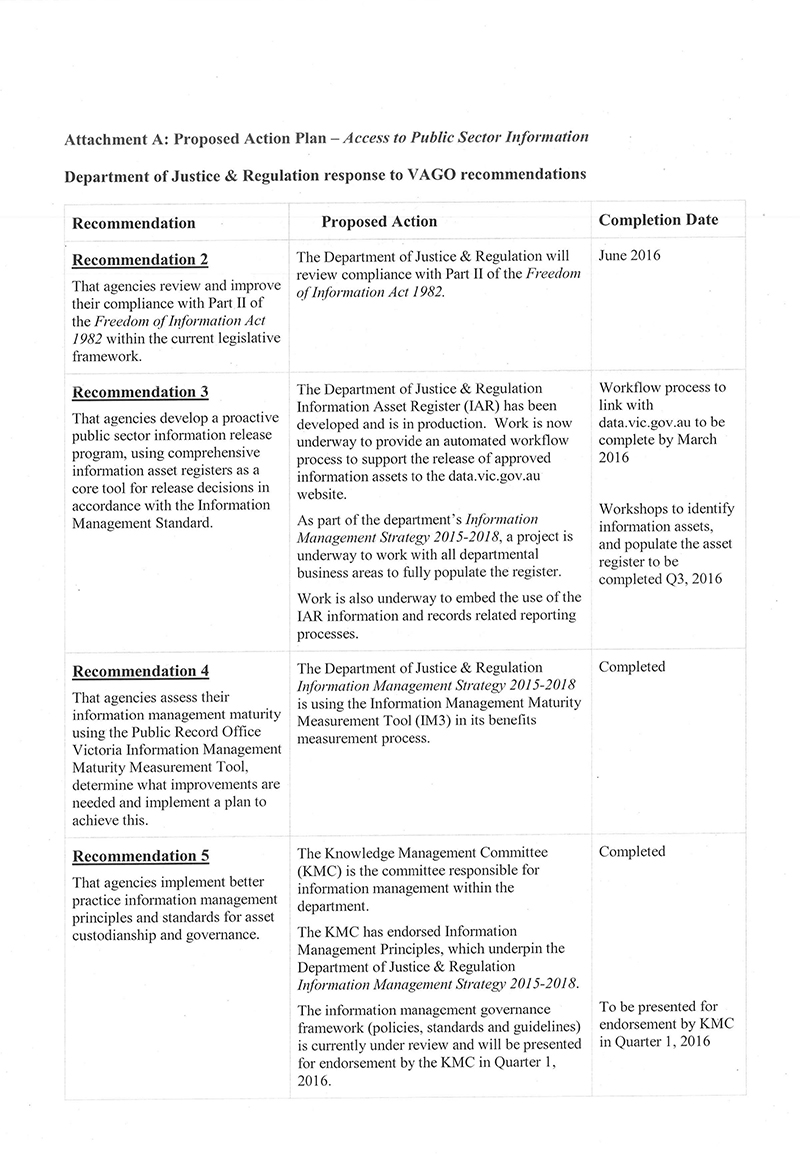

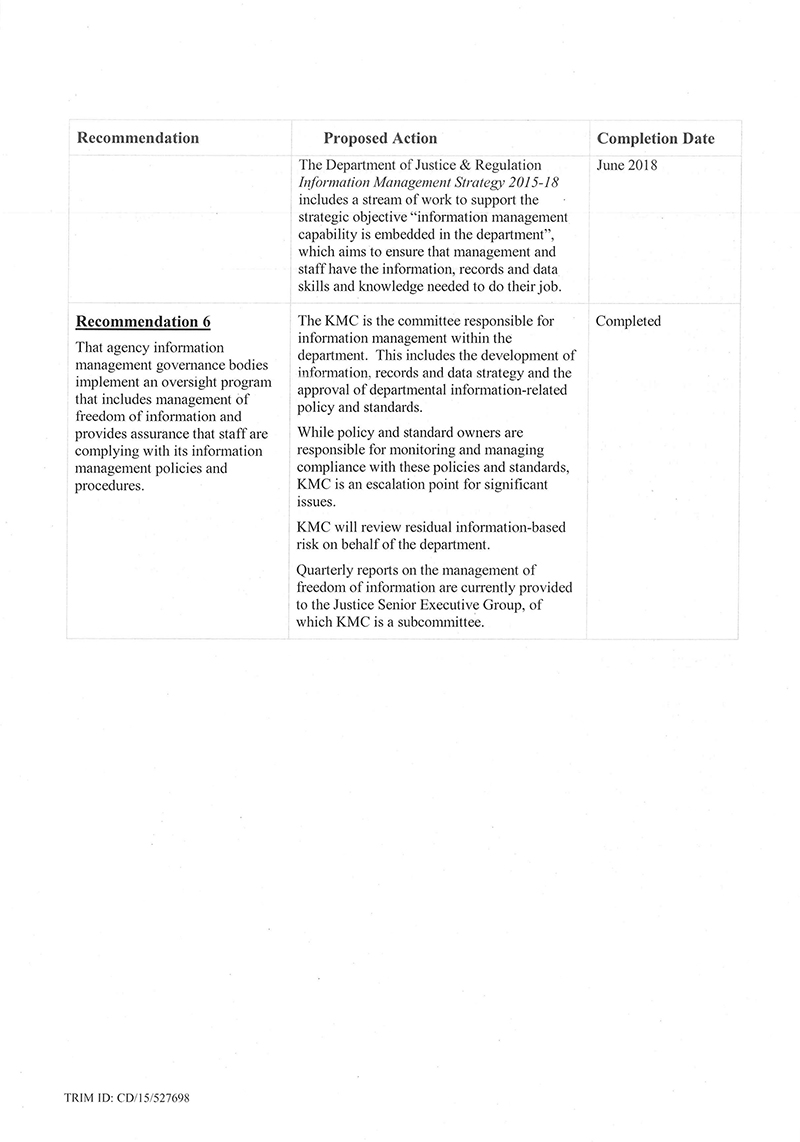

Submissions and comments received

Throughout the course of the audit we professionally engaged with the:

- Department of Premier & Cabinet

- Department of Treasury & Finance

- Department of Health & Human Services

- Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning

- Department of Justice & Regulation

- State Revenue Office

- Public Record Office Victoria.

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to those agencies and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix C.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Open access to public sector information

The importance of providing access to public sector information (PSI) is being increasingly recognised by government, business, research bodies, and the community at large.

As there are multiple definitions of PSI in Victoria, we have selected the one most consistent with the 2009 Parliamentary Inquiry into Improving Access to Victorian Public Sector Information and Data (PSI Inquiry) and the Inquiry committee's intended information management (IM) framework. Accordingly, in this report PSI includes all of the information that is generated, collected and funded by, or produced for government and is stored in all types of digital and physical media.

It is important to understand that the term PSI encompasses structured data—the traditional datasets that sit within databases—as well as unstructured data, or information—that includes all government records, emails, reports, briefings, photographs and more.

Governments across Australia and internationally have committed to improve access to PSI to:

- improve service outcomes—by providing all relevant agencies with the quality and scope of information they need to effectively and efficiently deliver services

- achieve greater accountability, transparency and engagement—by giving the community access to information to better understand agencies' performance

- achieve greater levels of innovation and economic growth—by allowing businesses and citizens to use this information to create products and services.

Critical barriers to providing open access to PSI include agencies failing to:

- understand and adequately manage their own PSI holdings—without recognising PSI as a valuable asset, assigning clear responsibilities for its management and ensuring that it is easy to discover and use, they cannot fully open it to the public

- apply an 'open by default' approach, by identifying PSI as accessible to the public unless it meets clearly understood criteria that legitimately prevent its release

- provide the tools the public need to understand what PSI they hold and how they can go about accessing it.

1.1.2 Victoria's commitment to open PSI

In its response to the PSI Inquiry, government committed to transform how the public sector provides access to the PSI it holds, by adopting an 'open by default' approach.

Government committed to helping public sector agencies:

- adopt the default position of open access to all PSI

- establish and apply systematic and consistent practices for categorising, storing and managing PSI

- only restrict access to PSI through the application of clearly defined criteria where this is required by law, contractual obligations, or national or state security

- promote and facilitate increased access to, and re-use of, Victorian PSI

- develop a whole-of-government PSI directory so that the public can know what information is held by government and how to access it

- make PSI available at no or marginal cost using the least restrictive licensing arrangements.

Government's response recognised two essential components of a successful approach to improving access to PSI—appropriate leadership, governance and accountability, and the implementation of an overarching IM framework.

Leadership, governance and accountability

Government's response recognised the need for a strong, appropriately authorised, whole-of-government governance framework if agencies were to achieve the type of transformation envisaged. The Department of Premier & Cabinet advised government about the scale of change required to achieve open access to PSI. Progress was dependent on a clear mandate to improve IM, strong governance, and accountability through timely and comprehensive progress reporting to senior government representatives.

Information management framework

The PSI Inquiry concluded that 'the best way for government to realise economic and efficiency gains from PSI is through the development and implementation of an overarching government information management framework'.

This framework was to provide government with systematic and consistent practices for categorising, storing and managing PSI. Doing this is essential to open access because agencies cannot effectively facilitate access to information that is not effectively catalogued, stored and managed.

1.2 Tools for facilitating access to PSI

1.2.1 Legislation and government policy

Open access to PSI, except where this would breach criteria showing that it would not be in the public interest, has remained a clear policy goal both before and since the PSI Inquiry. In responding to the Inquiry the government acknowledged the need to take account of legislative requirements in relation to personal information, privacy and confidentiality in developing an open access framework. Figure 1A describes how open access is embedded in legislation and policy.

Figure 1A

Open access requirements in legislation and government policy

|

Public Records Act 1973 and Records Management Standards This Act and its standards mandate that access to public records is open, unless there is a justifiable reason for restriction or closure. Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act) and the Freedom of Information (FOI) Obligations The object of the FOI Act is to 'extend as far as possible the right of the community to access information in the possession of the Government of Victoria…'. This includes, 'creating a general right of access to information in documentary form in the possession of Ministers and agencies limited only by [necessary] exceptions and exemptions…'. Section 16 notes that access to documents should be timely and inexpensive, and can occur outside the FOI Act:

Ensuring Openness and Probity in Victorian Government Contracts Policy Statement (2000) This policy requires agencies to publish, through a central register, details of contracts for the procurement of goods and services, and for the transfer of assets to the private sector. Contracts over $100 000 must be disclosed in summary and contracts over $10 million must be published. Whole of Government Intellectual Property Policy (2012) and Guidelines (2015) The policy is consistent with an open access approach, with the intent of granting rights to the state's intellectual property in a manner that maximises its impact, value, and accessibility consistent with the public interest. The guidelines stipulate how public sector agencies should identify, record, value and manage intellectual property so they can achieve the policy intent. DataVic access policy Standards and Guidelines (2013) The intent of this policy is to make public sector datasets freely available with minimum restrictions, and this includes proactively removing cost as a barrier to access. The guidelines emphasise the need to implement the IM framework's standards for creating an information asset register and putting in place governance arrangements to ensure the effective management of, and accountability for, the datasets they hold. Financial Reporting Directions—FRD22F: Standard Disclosures in the Report of Operations (2015) The directions require agencies to disclose certain information in annual reports, including organisational charts, key initiatives and projects, consultancy expenditure, and government advertising expenditure. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office summary of legislation, standing directions and government policies.

1.2.2 Information asset registers and metadata profiles

The PSI Inquiry report and government's response highlight that the failure to adequately identify and describe information critically undermines public access. In particular, the PSI Inquiry stated that 'one of the most critical issues to consider when improving access to PSI is the means by which information and data owned by government can be identified'.

Government accepted the PSI Inquiry's recommendation that metadata be a key aspect of the government's open access policy and IM framework. It also accepted recommendations that agencies create information asset registers and apply metadata to agency PSI.

1.2.3 Part II of the Freedom of Information Act 1982

Part II of the FOI Act has been in place since 1982 and requires agencies to publish material so the public can understand what PSI they hold and how to access it.

Part II requires agencies to publish statements—also called indexes—that specify their PSI, such as policies and procedures, documents used in making decisions affecting persons and in enforcing Acts and schemes that they administer, together with reports, advice and recommendations created in or for the agency. Figure 1B summarises the requirements.

Figure 1B

Summary of FOI Act Part II requirements

|

Part II of the FOI Act is designed to assist the public by providing information about what the agency does, how it acts, what information it holds and how to access the information. Specifically, agencies are required to publish and annually update statements—also called indexes—describing:

In addition, under section 10, the Premier is required to publish on a continuing basis a register containing details of the terms of all Cabinet decisions made, as well as the reference number assigned to each such decision and the date on which the decision was made. This information shall be entered on the register at the discretion of the Premier. |

Source: Victorian Auditor‑General's Office based on the FOI Act.

1.2.4 Data portals and PSI directories

Data portals—also known as data directories—allow users to search for, locate, download and re-use data for commercial or non-commercial purposes, through common metadata profiles. A whole-of-government data portal enables users to access data stored on the websites of public sector bodies.

Where the portal provides access to both structured and unstructured data—i.e. information—they are also referred to as PSI directories.

Government's response to the PSI Inquiry committed to establishing a whole-of-government PSI directory.

1.3 Government PSI initiatives

1.3.1 The Public Sector Information Release Framework

Government created a project sponsors' board to implement its response to the PSI Inquiry. By late 2011 the board had developed the Public Sector Information Release Framework (PSIRF) that addressed government's commitment.

By early 2012 the Department of Treasury & Finance assumed responsibility for PSIRF's implementation. However, instead of proposing the framework for government endorsement, it advised government to proceed with only a partial application of PSIRF. The proposed policy—the DataVic access policy—mandated the release of data held by public sector agencies through a centralised data portal. Government endorsed the policy, without mandating that agencies implement the underpinning actions of establishing and applying systematic and consistent practices for categorising, storing and managing PSI.

1.3.2 Victorian information management principles and standards

In 2011 and 2012, Victoria's Chief Information Officers' Council (CIOC) released a non-mandatory set of IM principles and standards that applied to government departments, VicRoads, Victoria Police and the State Revenue Office. Figure 1C summarises the high-level principles guiding IM, and the two standards that partially cover the application of these principles.

These principles closely match those proposed under PSIRF for the effective management of PSI. While the standards released by CIOC largely mirror PSIRF's intentions relating to agency information governance and custodianship, a number of additional intended PSIRF standards—in particular, those relating to metadata, information release, and charging for PSI—were not developed.

Figure 1C

CIOC IM principles and standards

|

IM principles 1. Information is recognised as a valuable asset—agencies develop an information asset register, integrate IM into their organisational planning and educate and encourage staff to exploit information to the full. 2. Significant information assets are managed by an accountable custodian—agencies manage significant information assets through their life cycle in line with their security risk profile, privacy, confidentiality and other statutory requirements. Agencies define roles and responsibilities in the management of these assets (custodianship model) and educate staff on their responsibilities. 3. Information meets business needs—custodians work with users to determine business needs and to manage, maintain and communicate information quality. Information use should be considered as it is being collected or developed and data quality statements are developed for significant information assets. Agencies put processes in place to improve data quality and work towards a single point of truth for key information assets. 4. Information is easy to discover—agencies describe information using appropriate metadata, appropriately restrict access on the basis of security, privacy, confidentiality or commercial risks and work towards a common, cross-government information directory and other mechanisms for facilitating information discovery. 5. Information is easy to use—agencies adopt and work towards using common standards across government for collecting, defining, storing and sharing information. Custodians work with users to define appropriate standards and sufficient metadata is provided to potential users so they know how to use information. 6. Information is shared to the maximum extent possible—agencies manage information with sharing, collaboration and interoperability in mind, and facilitate and actively promote sharing in accordance with security and statutory requirements. Agencies seek to re-use and build on existing information, release information to the public where appropriate while applying licences to promote reuse. IM standards

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on three Victorian Government CIOC documents—Whole of Government Principles: Information Management Principles (September 2011), Victorian Government Standard: Agency IM Governance (July 2012), Victorian Government Standard: Information Asset Custodianship (June 2012).

In 2013, the Public Record Office Victoria released an Information Management Maturity Measurement Tool—also referred to as the IM3. The tool is designed to assess agency IM practices and their alignment with the standards of the Public Records Act 1973 and CIOC.

While a 2012 guideline released by CIOC states that compliance against their standards would be measured through a coordinated survey, this never occurred.

1.3.3 DataVic access policy

The DataVic portal was first established in 2010, the accompanying policy was released in August 2012, and the standards for releasing datasets in February 2013.

The government's DataVic access policy mandated the use of the DataVic portal. The former government's information and communications technology strategy set quotas for the number of datasets that agencies were required to make available through the DataVic portal.

1.4 Audit objectives and scope

This audit examined agencies' progress in facilitating access to PSI and whether:

- whole-of-government leadership and oversight has supported improved performance in this area

- sampled agencies have effectively implemented the better practice IM essential to facilitating open access to PSI

- sampled agencies are effectively facilitating access to the PSI they own and hold

- sampled agencies and the Department of Treasury & Finance, in its oversight role, are achieving the DataVic access policy objectives.

The agencies with whole-of-government responsibilities included in this audit are the Department of Treasury & Finance, the Department of Premier & Cabinet, the Public Record Office Victoria and the Department of Justice & Regulation.

The sampled agencies, where we examined the application of open access were the State Revenue Office, the Department of Health & Human Services and the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of the audit was $420 000.

1.6 Structure of this report

This report has three further parts:

- Part 2 examines how well sampled agencies have facilitated access to their PSI

- Part 3 examines the quality of the IM that underpins the sampled agencies' access to PSI

- Part 4 examines whole-of-government leadership and oversight.

2 Facilitating public access to public sector information

At a glance

Background

A critical component of providing the public with access to the public sector information (PSI) that agencies hold is communicating what PSI is held and if and how a member of the public can access this information. This Part discusses how well agencies facilitate public access to PSI.

Conclusion

The agencies we examined are not adequately facilitating access to their PSI and are not fully meeting the requirements of Part II of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act). Agencies have complied with the DataVic access policy's dataset release quotas, but there is no evidence to demonstrate that this has resulted in its intended benefits.

Findings

- Agencies do not publish comprehensive information asset registers, which are an essential tool for facilitating public access to their PSI.

- Agencies have not implemented consistent agency-wide approaches to identifying PSI for proactive release.

- Agencies do not fully comply with the FOI Act's Part II requirements.

- Agencies have largely achieved targets for the number of datasets posted on the DataVic site. However a quota-driven approach has not encouraged agencies to prioritise posting datasets that are likely to best deliver on the policy's intended benefits. This, combined with the basic functionality of the DataVic portal, means the policy is falling well short of its potential.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Premier & Cabinet provides improved guidance for agency compliance with Part II of the FOI Act, monitors that compliance, and advises government on how the Act should be modernised.

- That agencies review and improve compliance with Part II of the FOI Act.

- That agencies develop a proactive PSI release program.

2.1 Introduction

A critical component of providing the public with access to the public sector information (PSI) agencies hold is communicating what PSI is held and if and how a member of the public can access it. This Part discusses how well agencies facilitate public access to PSI by examining whether they:

- provide tools that enable the public to fully understand what PSI they hold and how to go about obtaining it, including a published information asset register and clear approach to the proactive release of PSI

- more specifically meet their long-standing obligations under Part II of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act) to publish indexes that help the public understand what PSI they hold and how to access it

- apply the DataVic access policy in a way that achieves government's intended objectives of innovation, improved productivity and improved services through providing access to the datasets they hold.

2.2 Conclusion

The agencies we examined are not providing the public with full and open access to the information to which they are entitled.

Sampled agencies do not publish comprehensive registers, which are an essential tool for facilitating public access to their PSI. Nor have they implemented consistent agency-wide approaches to identifying the PSI that should be proactively released. The Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) is, however, close to publishing its newly created register.

These agencies have not fully met the requirements of Part II of the FOI Act. The guidance issued to improve this situation in 2012 was inadequate and is unlikely to have improved agencies' performance.

Along with the Department of Treasury & Finance (DTF), the sampled agencies cannot demonstrate that their application of the DataVic access policy has resulted in the intended benefits of stimulating economic activity through new, innovative services, increasing productivity through better decision-making, improving research outcomes and delivering services more effectively and efficiently. While agencies have largely achieved targets for the number of datasets posted, the quota-driven approach has not encouraged agencies to prioritise posting datasets that are likely to best deliver on the policy's intended benefits. This, combined with the DataVic portal's basic functionality, means the policy is falling well short of its potential.

2.3 Tools critical for public access to PSI

Part 1 of this report identifies a number of tools that can be used to effectively facilitate access to PSI. The most critical is a comprehensive, accessible information asset register, supported by a consistent approach to the proactive release of PSI. The agencies we examined currently do not publish this type of register and have not applied a consistent cross-agency approach to the proactive release of the PSI that they hold.

2.3.1 Information asset registers

The agencies we examined do not publish information asset registers, and the Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning's (DELWP) does not have an information asset register, as required by the Information Management Governance Standard. Consequently, the public has no way to understand the agencies' full PSI holdings, limiting—and in some cases, even removing—their ability to access the PSI that they hold.

Agencies often point to their websites as the repository of information of relevance and value to the public. However, this approach to information disclosure and providing access is inadequate. Discovery of information depends on the search skills of the person examining the website, what agencies have placed there, and the way in which they have stored and described information within the site.

There are specific weaknesses in relying on users' research skills as a substitute for a public information asset register:

- Information assets may not be published on the website—or at all—and are therefore not able to be located this way. Examples include agency contracts and unpublished internal reports, datasets, and performance information.

- A range of information assets might be considered exempt from open access and excluded from website publication listings. However the 2009 Parliamentary Inquiry into Improving Access to Victorian Public Sector Information and Data considered that a register should be comprehensive in identifying all PSI and clearly showing where access to particular information assets has been restricted.

- Those seeking a specific information asset may not know its title or how the agency has categorised it, rendering discovery through a website or publication search difficult, if not impossible.

- Websites are becoming increasingly complex and multi‑layered and this is likely to make finding information more challenging and time consuming.

Information asset registers have the potential to address these weaknesses. We note that DHHS is close to publishing its recently created information asset register.

2.3.2 A consistent approach to the proactive release of PSI

The absence of a coordinated approach to identifying PSI for release can result in decisions being subjective, and being made without a full understanding of the different legislative considerations. For example, under the Public Records Act 1973, access to a record is open unless there is a justifiable reason for restriction or closure. Under the FOI Act, where access is open the record is expected to be made available.

None of the agencies we examined applied a consistent, cross-agency approach to the proactive release of PSI. We also found no evidence of agency FOI staff working with information management (IM) staff to identify PSI for release.

Instead, decisions about proactive release were being made at the business unit level on a case-by-case basis. This may or may not include consultation with FOI staff, who have no authority to require business units to release their information outside of applications made under the FOI Act.

There appears to be a general perception that if information is required to be restricted from general public access, there is no obligation for agencies to make the public aware that such information exists.

Figure 2A illustrates how a recent DELWP initiative—the upcoming Know Your Council website—while being a positive and important step in facilitating public access to government information, is not fully consistent with an open access approach to PSI.

Figure 2A

DELWP's approach to proactive release

|

The premise of open access to PSI is that it is made freely available for everyone to use, re-use and distribute with, at most, the requirement to attribute and share-alike(a). As part of the upcoming 'Know Your Council' website, citizens will have unrestricted access to a dataset of all 66 performance measures of all 79 councils. This is a very positive first step toward improving public access to PSI, and a welcome innovation that enables the public to better understand council performance. However, while this represents improved access to PSI, it falls short of being open access. To fully understand a performance measure, it is also necessary to understand the data that sits underneath it (the 'raw data'). This data will not be publicly accessible. DELWP advised us that councils commented that there was a possibility that a portion of the raw data underpinning the performance measures could be commercial‑in‑confidence—as a result of individual councils having entered into contracts with private providers. DELWP did not seek to identify the specific measures for which the councils' raw data was commercial-in-confidence, with a view to opening up the data as much as possible by:

In response to the advice it received from councils, DELWP decided that it would not publish any of the raw data. |

(a) Share-alike is a copyright licensing requirement for copies or adaptations of works to be released under the same or similar licence as the original work.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office adapted from documentation provided by DELWP.

2.4 The FOI Act—Part II compliance

The agencies examined do not fully comply with the Part II requirements of the FOI Act to publish registers of the documents that they own or hold.

Agencies often provide a wide range of PSI through their websites, easily meeting the requirements of sections 7 and 8 of the Act. However, they fail to meet section 11 requirements to specify the particular documents and reports generated each year. Instead, agencies provided a general statement and, at best, a snapshot of the kinds of documents they hold.

Agencies may very well be making some or all of the relevant information available to the public through their websites and other publications. However, without such registers, it is unlikely that the public will understand what is available and therefore access to it is impeded.

It is important to understand that the FOI Act was passed in a predominantly paper-based environment and is now a significantly outdated piece of legislation. Agencies argued that the 'digital age' renders such registers unnecessary as they now simply publish straight to their websites. Section 4.3.1 of this report describes the weaknesses and flaws in this approach.

On the contrary, the 'digital age' means the use of registers is essential. The number of potential places where PSI may be held within a website's many pages means that discovering the exact information wanted is more difficult, making the register a key navigational tool.

We have seen no evidence that the agencies examined maintain an internal, comprehensive list of their documents and we conclude that they are not currently in a position to comply with this requirement. This shortfall was identified by the Ombudsman's 2006 report Review of the Freedom of Information Act 1982, but no meaningful action has been taken.

We also established that the Department of Premier & Cabinet has never published a register of Cabinet decisions. While the content of such a register is at the discretion of the Premier, its existence is mandated by law.

2.4.1 Explaining FOI Act Part II compliance shortfalls

The Ombudsman's 2006 report concluded that:

- '…few Victorian agencies fully comply with the publication requirements of Part II statements' …'This affects applicants' knowledge of the documents available and their ability to clearly frame requests.'

- 'It is not acceptable for departments and other agencies to ignore statutory provisions or to choose to implement those provisions as they see fit and not in accordance with the statute.'

The 2006 report recommended that government agencies review their compliance with Part II, that government review, as a matter of urgency, Part II with a view to modernising and improving the publication scheme, and that the former Department of Justice (DOJ)—the agency responsible for the Act at that time—should monitor agencies' compliance with Part II.

DOJ prepared proposed legislative amendments to the FOI Act in 2008, including:

- the kind of information to be published on the agency's own website or another agency or government website

- how frequently the information is to be published, reviewed and updated

- the form in which the information is to be published

- the circumstances in which an agency may publish information on behalf of another agency.

However, these amendments were not passed.

VAGO's 2012 report, Freedom of Information, recognised the challenges of meeting obligations that were crafted in a different technological age, but recommended that DOJ provide guidelines to help agencies meet their obligations.

We found that no meaningful progress has been made towards improving agencies' compliance with Part II of the FOI Act and better using Part II statements to communicate what information agencies hold.

DOJ's efforts to better guide agencies about their Part II responsibilities were inadequate. Practice Note 14, issued in response to our Freedom of Information audit, infers that agencies can acquit their requirements through a statement describing what the agency does, how a person can access information, and through a 'snapshot of the types of documents held'. This creates the potential for agencies to use compliance with this instruction as a mechanism to avoid listing the specific documents they hold.

DOJ's more detailed guidance relating to Section 11 states only that the agency must make a wide range of materials available. It fails to explain that agencies must specify the documents in a register or index.

The nature of this guidance helps to explain the inadequacy of the statements produced by the agencies examined in this audit.

DOJ published the guideline before it handed over its FOI responsibilities to the FOI Commissioner. DOJ has not provided any evidence describing how it implemented and evaluated the impact of these guidelines or that it had assessed and managed the risks to improving compliance prior to handing over responsibility.

We found that agencies used this guidance to justify their clear lack of compliance with the Part II requirements. For example DHHS stated that 'The department acknowledges Part II statements could be more detailed. The department took the reasonable approach of following the guidance issued by DOJ, the agency previously responsible for the FOI Act'. DELWP also advised us that the content of its Part II statements were framed to meet the requirements as set out in DOJ's guidance.

2.4.2 Implications of the lack of compliance with Part II of the FOI Act

Providing a comprehensive listing of information held by agencies is critical to effectively facilitating public access to PSI. The current system is in a state of disarray where we are not confident agencies understand what PSI they hold and we are certain that they are not providing the public with the means to request this information.

Currently the absence of a rigorous approach to managing information and publishing comprehensive registers has significant implications for public access and the sharing of information across government.

2.5 Application of the DataVic access policy

The application of the DataVic access policy is at a relatively low level of maturity and needs to be improved. In this section we examine:

- the limitations inherent in the approach to making datasets available, describing the weaknesses of a quota-driven approach and limited functionality in the way these data are presented to the public

- the absence of a structured approach to assessing the achievement of the policy's intended outcomes.

2.5.1 Meeting data release quotas

In January 2015, DTF reported to government on the negative impacts of the quota-driven approach to dataset publication. Specifically, the report confirmed that this approach resulted in agencies quickly releasing large volumes of data. However, it also encouraged them to reach their quotas by releasing their low-value data and splitting their large datasets into many smaller ones.

We observed several examples of this type of dataset splitting during the audit as shown in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

'Split' datasets observed in the DataVic portal

|

Source: Victorian Auditor‑General's Office based on DataVic portal.

Setting dataset release quotas has made the portal more difficult to navigate and, in some cases, made it more complicated to collate and analyse data. Combining datasets where appropriate allows public users to compare data more efficiently and effectively. In the DTF example cited in Figure 2B, instead of there being one dataset with all contract expenditure data, there are 44, and for the DHHS example, instead of one dataset, there are 80.

Functionality and ease of use of the DataVic portal

Our examination of the DataVic portal shows it to be at a low level of maturity.

The portal has recently been improved to provide 15 categorised 'sub‑portals' to help a user find the information of interest. However, this has only marginally improved the site's functionality and ease of use.

There are several weaknesses in the DataVic portal:

- Data ownership—the number of datasets shown in the organisational listing and the number shown by searching using the organisation's name often differ.

- Links to datasets—we found multiple instances of links being broken for extended periods. In these cases, the portal simply refers the user to the agency website. This degrades the user experience and defeats the portal's purpose.

- Metadata profiles—little beyond the dataset's title and a few words of description are accessible without drilling down into the record. The exception to this is DELWP's spatial datasets. Providing a consolidated view of the basic metadata profiles of each dataset would increase users' ability to access the data that they are seeking without needing to guess its owner, title, assigned category, and other attributes.

- Data quality—currently, including this information is optional and we found very few examples where agencies had elected to provide a data quality statement for its datasets. Again, the clear exception to this is DELWP, whose spatial data includes a rich metadata profile for each of its datasets that enables a full understanding of the data being made available.

2.5.2 Demonstrating the achievement of policy objectives and managing the risks

There is no framework in place to measure the achievement of the DataVic access policy's intended outcomes and agencies have no clear idea about the extent to which the policy has been a success.

Performance reporting to government is confined to the number of datasets being released. We found no assessment of their contribution to the government's intended outcomes of:

- economic stimulation

- improved productivity

- better access for researchers to critical and useful data

- improvements to the efficiency and effectiveness of government through improved management practices and the better use of data.

DTF has demonstrated an understanding of the current weaknesses in the application, evaluation and oversight of the policy that are constraining its potential. We have seen evidence of recent activity by DTF to change the focus from data release quotas to value-adding releases. The approach includes consulting with data providers and likely data user groups to raise awareness of the benefits of information sharing, enhance government's understanding of user demand for PSI, and increase that demand.

DTF has also commenced a project to encourage the adoption of creative commons licensing by agencies for appropriate documents and websites.

However, many of the actions to address the policy's weaknesses are still in the planning phase and need to be progressed. They also lack consideration of the importance of agencies first implementing the whole-of-government IM principles and standards to achieve the policy's intended outcomes.

The success of any efforts to increase demand for PSI depends on users first being able to understand what exists in agencies' information holdings. This requires agencies to publish comprehensive and well-structured information asset registers.

DTF needs to revise its approach to implementing the DataVic access policy by:

- helping agencies move from a quota focus to prioritising the publication of high-value data collections

- developing and applying an evaluation framework to better understand the potential and realised benefits, as the basis for better using resources to deliver on the intended benefits

- integrating the policy into a more comprehensive whole-of-government IM framework.

Agencies also need to adopt a methodical, fully informed approach to dataset release based on an assessment of the costs and policy benefits.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Premier & Cabinet, as the agency responsible for supporting the Freedom of Information Act 1982, provides improved guidance for agency compliance with Part II of the Act, monitors that compliance, and forms and implements a plan to:

- help agencies improve their compliance with the section 11 requirement to comprehensively list the material that they hold

- review and advise government on how to modernise the Act to achieve its objectives in a way that is best aligned with a modern information management environment and Victoria's records and information management standards.

- That agencies review and improve their compliance with Part II of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 within the current legislative framework.

- That agencies develop a proactive public sector information release program, using comprehensive information asset registers as a core tool for release decisions in accordance with the Information Management Governance Standard.

3 Agency information management

At a glance

Background

This part examines information management (IM) practices in a sample of agencies and rates agencies' maturity using the Victorian IM better practice principles and standards.

Conclusion

None of the sampled agencies had fully established practices consistent with the better practice principles and standards.

Findings

- The Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) is progressing to better practice, with strong IM governance, clear senior level support and a comprehensive IM strategy. However, many initiatives are still in their early stages.

- The State Revenue Office (SRO) has established good foundations, and is refining its IM approach, with many plans in development.

- The Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning has formative IM practices and has not yet established the minimum framework needed to effectively manage all of its public sector information (PSI).

- While none of the agencies have reached a level of maturity that fully facilitates access to their PSI, there is evidence that all are working towards this and that DHHS and SRO can potentially achieve this in the short term (one to two years).

Recommendations

That agencies:

- assess their IM maturity using the Public Record Office Victoria's Information Management Maturity Measurement Tool and address any deficiencies

- implement better practice IM principles and standards for asset custodianship and governance

- implement an oversight program that provides assurance that staff are complying with IM policies and procedures.

3.1 Introduction

This part examines information management (IM) practices in a sample of agencies as these practices critically determine how easily the public can access their public sector information (PSI).

Section 1.3 discussed the Victorian IM principles and standards including:

- establishing appropriate IM governance and custodianship arrangements

- developing and maintaining an information asset register for significant information assets and assigning responsibility for the assets to custodians

- establishing policies and processes to ensure that information assets are fit for purpose as they are being created or received, including information quality management and access mechanisms

- ensuring information is easy to discover by applying appropriate metadata

- adopting common IM standards, and contributing to a cross-government PSI directory and other information access mechanisms

- devising systems and encouraging behaviours for sharing information to the maximum extent possible.

The 2009 Parliamentary Inquiry into Improving Access to Victorian Public Sector Information and Data also recognised that one of the biggest barriers to improving access to PSI is agencies not cataloguing information in a way that it can be identified or discovered. Hence the importance in creating comprehensive and accurate information asset registers that are populated with metadata describing the information held, its location, content, how it has or could be used, and its quality.

We assessed the IM maturity of the:

- Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS)

- State Revenue Office (SRO)

- Department of Environment, Land, Water & Planning (DELWP).

3.2 Conclusion

None of the sampled agencies had fully established practices consistent with the Victorian IM principles and standards and their performance varied:

- DHHS is progressing to better practice, with strong IM governance, clear senior level support and a comprehensive IM strategy. However, many initiatives are still in their early stages.

- SRO has established good foundations, and is refining its IM approach, with many essential plans and projects in development.

- DELWP only has formative IM practices and has not yet established the minimum framework needed to effectively manage all of its PSI.

While none of the agencies has reached a level of maturity that fully facilitates access to their PSI, we saw evidence that all are working towards this and that DHHS and SRO have the potential to achieve this in the short term.

A key reason for the slow progress in improving PSI practices is the absence of a coherent and appropriately authorised whole-of-government governance framework to help agencies. It is therefore likely that the problems seen at DHHS, SRO and DELWP will be replicated at the vast majority of public sector agencies.

Where agencies are not effectively managing their PSI, there is little confidence that they are able to effectively facilitate access to it. Agencies that are not facilitating access to their PSI are failing to uphold one of the fundamental tenets of a democratic government.

3.3 Public sector information management

3.3.1 Agency information management

We assessed agencies' maturity with respect to the Victorian Government IM principles and standards and rated them as either:

- formative (~) where there is no agency-wide IM strategy, senior level support or adequate governance, and improvements are generally reactive

- in development (✔) where good IM structures are in place, but gaps remain where they are not being effectively applied

- progressing (✔✔) where the approach to IM is structurally sound, but not yet fully applied to all PSI

- established (✔✔✔) where agencies can demonstrate that they are effectively applying the better practice principles and standards in managing their entire information holdings and can provide assurance about information quality.

A comprehensive description of these ratings can be found in Appendix A.

Figure 3A shows the overall ratings for the three sampled agencies as:

- 'progressing' to better practice for DHHS

- 'in development' for SRO because it is refining its IM structures and processes

- 'formative' for DELWP because it had not yet established the minimum framework needed to effectively manage its entire PSI holdings.

Figure 3A

Information management maturity assessment

|

Criteria |

Ratings |

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

DHHS |

SRO |

DELWP |

|

|

1. Information is recognised as a valuable asset |

✔✔ |

✔✔ |

~ |

|

2. Significant information assets are managed by an accountable custodian |

✔✔ |

✔ |

~ |

|

3. Information meets business needs |

✔ |

✔ |

~ |

|

4. Information is easy to discover |

✔✔ |

✔ |

✔ |

|

5. Information is easy to use |

✔ |

✔ |

~ |

|

6. Information is shared to the maximum extent possible |

~ |

~ |

~ |

|

Overall assessment |

✔✔ |

✔ |

~ |

Source: Victorian Auditor‑General's Office.

3.3.2 Department of Health & Human Services

We rated DHHS as progressing in its IM maturity.

In terms of positive IM attributes, DHHS has:

- a strong IM governance framework with clear senior level support

- a comprehensive IM strategy that is integrated with its corporate objectives and planning

- frequently assessed its maturity and acted to continuously improve it.

These positive attributes have to be balanced against the need to:

- fully implement its IM strategy's objectives and actions

- fully populate its asset register to cover all of its information holdings

- ensure that the register includes metadata that fully describes each information asset

- implement its agreed IM training program

- publish its information register to appropriately facilitate public access to its PSI and to comply with Part II of the Freedom of Information Act 1982 (FOI Act)

- develop and implement a program for proactive PSI release—with clear and structured processes and criteria for assessing and authorising restrictions to an 'open by default' approach.

DHHS is now clearly on a pathway to improving its IM. However, progress towards applying the whole-of-government principles and standards has been slow and inconsistent. It is essential that DHHS maintains its current momentum and fully applies its IM framework to its PSI.

For DHHS, machinery-of-government changes since 2009 and job cuts made through the Sustainable Government Initiative (SGI), which aimed to reduce the number of public sector staff across all departments, between 2011 and 2013 impeded the application of these principles and standards. Figure 3B shows how the changes disrupted progress towards better practice IM.

Figure 3B

The impact of machinery-of-government changes and SGI cuts on DHHS IM

|

Event |

Impact |

|---|---|

|

August 2009 machinery-of-government change: DHHS split into Department of Health (DH) and Department of Human Services (DHS) |

|

|

Between 2011 and 2013—SGI cuts(a) DHS loses 659 staff—IM staff reduced from 10 to 0.5 |

|

|

December 2014 machinery-of-government change: Re-amalgamated DH and DHS into DHHS |

|

(a) From <http://www.afr.com/news/policy/industrial-relations/victoria-cuts-4000-public-service-jobs-to-save-surplus-20131021-jgvgd>.

Source: Victorian Auditor‑General's Office based on information provided by DHHS.

We do not want to understate the scale of the challenge DHHS faces in fully applying the IM framework that it has built. The former DHS has a significantly larger amount of unmanaged information in its holdings than the former DH, and its IM practices have been criticised by VAGO in the 2012 audit report on Freedom of Information, and the Ombudsman in the 2012 report on its Own motion investigation into the management and storage of ward records by the Department of Human Services.

Figure 3C illustrates this by describing the challenges presented in effectively managing the large volume of records for former wards of the state. It illustrates the scale of the tasks, what DHHS has and is doing, and the significant risks that remain.

Figure 3C

Ward of the state records

|

In 2012, the Victorian Ombudsman found that DHS was holding around 80 linear kilometres of historical records in boxes, a 'considerable portion' of which had not been inspected or indexed. These boxes included collections relating to former wards of the state and the institutions responsible for their care, as well as those relating to child migrants and aboriginal children removed from the care of their families and placed in institutional care. The former DHS' failure to index these critical records over the years significantly compromised its ability to effectively respond to FOI requests. As a result, DHS would not have been able to give any applicant any assurance that they were being given all the existing records about themselves. The former DHS commenced implementation of a Ward Records Plan in 2012 and has now indexed a large number of ward records. However, more records are yet to be indexed—such as its mental health records collection. DHHS advised us that it will complete the indexing of all DHHS ward, disability and mental health files by September 2016 and is reporting progress quarterly to the Ombudsman. DHS—now DHHS—was required to notify the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse that there was an inherent risk of it being unable to provide certainty over the completeness of records provided in response to a summons. This risk, of course, also extends to former wards currently or previously seeking access to information about themselves and their time in care. This risk will continue as long as DHHS holds records that could potentially hold evidence of abuse of wards of the state and where the contents of those records is unclear. Further, while this risk may decrease with the decrease in records still to be indexed, this must be weighed against the value that they hold to an abuse survivor who is required to demonstrate evidence of abuse in order to access redress opportunities. The 2012 Ombudsman report estimated that from 1960 to 1986, there were at least 50 000 wards of the state and that approximately 21 per cent of searches for records relating to FOI requests by former wards resulted in no documents being found. |

Source: Victorian Auditor‑General's Office.

3.3.3 State Revenue Office

We rated SRO as 'in development' with respect to its IM maturity.

In terms of positive IM attributes, SRO has:

- a strong IM governance framework with clear senior level support

- assessed its IM maturity and used the findings to develop improvement plans

- developed and implemented an information asset register and PSI custodianship arrangements.

These positive attributes have to be balanced against the need to:

- implement its IM strategy

- focus on using its information asset register for information assets, rather than repositories and software, and include metadata that fully describes each information asset

- improve custodianship arrangements so that their responsibilities include ensuring information assets are discoverable, easy to use and shared to the maximum extent possible

- implement an IM training program

- implement IM performance monitoring

- publish its information register to facilitate public access to PSI and to comply with Part II of the FOI Act

- develop and implement a program for proactive PSI release—with clear and structured processes and criteria for assessing and authorising restrictions to an 'open by default' approach.

Unlike DHHS and DELWP, SRO is a largely process-oriented organisation. It has historically prioritised the security of its highly sensitive data over achieving broader IM effectiveness.

After the 2009 Inquiry into Improving Access to Victorian Public Sector Information and Data, SRO resolved to examine how to align its predominantly non-disclosure environment with an 'open by default' approach to PSI. SRO's executive also recognised the opportunity to improve its information release framework.

SRO commissioned an internal review in 2012 that found that SRO did not have an overall policy or procedures on information release, or a coordinated approach to IM and information release. It found that each branch of the organisation had developed its own procedures for managing information release and there was no consistency.