Access to Services for Refugees, Migrants and Asylum Seekers

Overview

Migrants, refugees and asylum seekers are among the most vulnerable people in our community because of their often complex and significant needs. Migrants with low English proficiency, and refugees and asylum seekers who have suffered traumatic experiences in their home country and on their journey to Australia, face challenges in accessing the services they need during settlement.

The focus of the audit was on service delivery departments (health, education, and human services) and central agencies with responsibility for multicultural affairs.

While strategic frameworks show that departments understand the concept of cultural diversity, there is less assurance that they understand the multiple needs of refugees and asylum seekers. Departments have policies and programs in place which are informed by stakeholder engagement but not by systematic and ongoing data analysis. Departments report annually on utilisation of their services but not on whether these services are meeting client need.

Victoria has a whole-of-government policy that commits to accessible and responsive service provision to these groups but the structures and processes that have been set up are not resulting in informed and coordinated service planning and delivery.

For improvement to occur there needs to be greater cross-department collaboration, better data collection and analysis to identify if client needs are being met, and stronger oversight of departmental performance.

Access to Services for Refugees, Migrants and Asylum Seekers: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2014

PP No 324, Session 2010–14

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Access to Services for Migrants, Refugees and Asylum Seekers.

The audit assessed the accessibility of government services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. The main focus of the audit was on whether departments understand the needs of these often highly vulnerable groups, have in place appropriate strategies and programs to meet these needs, are able to identify whether the programs are effective or not, and work together across government to provide 'joined up', responsive services.

I found several shortcomings with respect to these issues, the most significant being the absence of a consistent, coordinated, whole-of-government approach to service planning and provision. Despite the recent release of a new multicultural policy and the existence of several cross-departmental agencies and mechanisms, I found no clear authority or governance structure that would enable departments to be held to account.

I have made six recommendations aimed at improving cross-department coordination and at encouraging departments to develop comprehensive cultural diversity plans and systematically collect and analyse data to determine whether their services are accessible and meeting client need.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

29 May 2014

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Michele Lonsdale—Sector Director Karen Ellingford—Team Leader Teri Lim—Analyst Joanna Humphries—Analyst Steve Vlahos—Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Migrants, particularly those with low English proficiency or poor literacy in their own language, and refugees and asylum seekers are among our most vulnerable members of the community. This is because they often have complex needs, particularly in relation to health, welfare and language services. A whole-of-government approach to the broader area of multicultural affairs should improve integration, reduce duplication and better identify gaps in services. Monitoring and reporting on whole-of-government activities to improve performance is also critical in making sure needs are met and outcomes improved.

In this audit I have looked at how effectively the Department of Education and Early Childhood, Department of Health, Department of Human Services, Victorian Multicultural Commission and Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship are meeting the needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in the areas of health, education and human services.

The departments I looked at have strategic frameworks that are underpinned by the principles of multiculturalism, including recognition of cultural diversity. However, two of the three departments incorporate migrants, refugees and asylum seekers into a broad pool of vulnerable and disadvantaged people, which may lead to the specific needs of these cohorts not being identified and addressed appropriately. It was difficult for my office to gain assurance that these needs were well understood and clearly linked to plans that would make a difference.

The audit identified a number of weaknesses in the available demographic data that have made service planning difficult for departments and local governments. More systematic collection and analysis of feedback from clients, and public reporting of this information annually by departments, would assist in improving the accessibility, responsiveness and effectiveness of services.

Perhaps the issue of greatest concern is the lack of regular collaboration among departments working to address the needs of the same cohort, and the lack of authoritative leadership and oversight to monitor and report on whether services are meeting the needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. I found a similar issue in my Accessibility of Mainstream Services for Aboriginal Victorians report, which was also tabled today.

My office found examples of good practice by departments and service providers but these are not sufficiently embedded within or shared across departments. Migrants with low proficiency in English, refugees and asylum seekers continue to face barriers to access.

It is not enough for whole-of-government agencies to coordinate isolated activities or support departments in developing their cultural diversity plans. There needs to be genuine accountability for performance in this area, with public monitoring and reporting of how department initiatives are leading to improved access for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

The report contains six recommendations which, if implemented, will help address the gap in monitoring, reporting and accountability that currently exists in Victoria's whole-of-government approach to multicultural affairs.

I intend to revisit the issues raised in this report to ensure they are being appropriately addressed.

I also want to thank the staff in the Department of Health, Department of Human Services, Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship and Victorian Multicultural Commission who assisted with this audit and for their constructive engagement with the audit team throughout.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

May 2014

Audit Summary

Victoria has benefited economically, socially and culturally from successive waves of immigration. Each group of migrants has had its own challenges, with low English proficiency often being a key barrier to accessing services effectively. However, the diversity and composition of these immigrants has changed in recent years.

Many recent newcomers to Victoria have significant and complex needs. In addition to language difficulties and the need for substantial interpreter support, refugees and asylum seekers are more likely to have physical and mental health conditions arising from their experiences in their country of origin and during their journey to Australia. They may face significant barriers to accessing services, including isolation, transport barriers, financial barriers, lack of familiarity with service systems and lack of social networks that could help them understand their rights to services or the practicalities of arranging the help they need.

Inability to access services in a timely and effective manner can lead to increased disadvantage and disengagement for individuals who are already highly vulnerable in our community. This has flow-on costs to the health system, public housing, criminal justice system and other government services.

There are multiple agencies and tiers of government involved in providing services to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. The Commonwealth Government has an overarching policy role in this area. It determines the numbers, composition and distribution of people entering Australia—including asylum seekers.

Photograph courtesy of the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship

Victoria has adopted a whole-of-government approach to delivering multicultural services. Local government also plays a role in service access and responsiveness.

The objective of the audit was to assess the accessibility of government services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. To meet this objective we examined whether:

- government departments understand the needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

- departments have appropriate strategies and actions in place to support access to services

- departments can demonstrate that services are accessible to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

- whole-of-government structures and processes are leading to informed and coordinated service planning and delivery.

In the report, reference is made to culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities as an umbrella term that includes migrants, refugees and asylum seekers as this is the term that is often used by departments and agencies.

The audit looked at effective access to mainstream services and at targeted programs designed to support access to these services, including three key programs:

- Maternal and Child Health service, which is universal and free—Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

- Refugee Health Nurse Program, which is a targeted service delivered through community health centres—Department of Health

- family violence services, which are mainstream services that link to other services—Department of Human Services.

Conclusions

While all service delivery departments—the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, Department of Health, and Department of Human Services—can demonstrate understanding of multicultural principles, including the need to cater for diversity, only the Department of Health can demonstrate at a strategic level that it understands the complex and multiple needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

While Victorian Government departments must work within the constraints of Commonwealth immigration and asylum seeker policies, they could be doing more to provide a consistent, coordinated and efficient approach to service planning and provision. This includes:

- developing current, comprehensive and evaluated cultural diversity plans

- basing the design and delivery of services on systematic data collection and analysis

- coordinating stakeholder consultation to maximise usefulness and minimise duplication of effort

- explicitly recognising in strategic planning frameworks the particular and significant needs of these groups beyond simply their diversity.

All departments are required to report annually to the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship (OMAC) on their cultural diversity planning, use of interpreters and translators, and multilingual publications. However, this reporting is limited to outputs rather than outcomes, and departments cannot give assurance that their services are meeting client needs.

Lack of regular and accurate Commonwealth settlement data on newly arrived refugees and asylum seekers makes service planning difficult for departments. This lack of warning can lead to departments being reactive to new arrivals who have been given insufficient support from Commonwealth-funded programs. Regardless, service delivery departments and service providers could be doing more to collect and analyse client feedback and other relevant data for planning and evaluation purposes.

The new Victorian multicultural policy, Victoria's Advantage: Unity, Diversity, Opportunity, introduces key performance indicators for the first time—a significant step—but these are based on existing datasets and will not enable departments, OMAC or the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC) to determine if services are being effectively accessed.

Service delivery departments have a range of strategies and programs in place but these vary in the degree to which they can demonstrate how service design and delivery for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers has been informed by a sound and systematic assessment of client need.

Whole-of-government structures and processes are not resulting in informed and coordinated service planning and delivery. Despite some examples of departments working together effectively, these collaborative activities are not consistent, embedded or systemic. The two public sector entities tasked with whole-of-government roles and responsibilities—OMAC and VMC—are not being used to their full potential. As a unit within the Department of Premier and Cabinet, OMAC cannot hold other departments to account. As an independent advisory body, VMC lacks the statutory mandate to do so. This leaves a significant gap in the monitoring and reporting of whole‑of‑government service accessibility, responsiveness and effectiveness.

Findings

Understanding of effective access

Service delivery departments can demonstrate understanding of multicultural principles, including diversity, but, apart from the Department of Health, cannot demonstrate at a strategic level understanding of effective access as this applies to the complex needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. This is because these groups are generally incorporated into a broader group of vulnerable or disadvantaged people. Absorbing them in this way means that their particular needs may not be appropriately identified or addressed to support improved service access.

Department understanding of service needs is based mainly on stakeholder consultation rather than systematic data collection and analysis. Lack of supporting data means that there is little assurance that this understanding is sufficiently comprehensive, accurate and soundly based. Stakeholder consultations are not coordinated within or across departments, leading to duplication of effort and reduced usefulness of the information being gathered.

Strategies and programs

There is little assurance that departmental staff are sufficiently aware of and sensitive to the particular needs of CALD communities due to a lack of transparency and clarity around how embedded cultural competency training is in departments. At the service provider level, lack of culturally aware staff was a common issue raised in stakeholder consultations during the audit. While there is evidence in the form of accreditation standards and processes to show that cultural competency is required of service providers, this competency is often described in generic terms relating to tolerance and diversity rather than in terms of staff being required to understand the particular and multiple needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

Most service delivery departments do not have current, comprehensive and evaluated cultural diversity plans. Without these plans, or their equivalent, their capacity to provide a consistent and efficient approach to service planning and provision is reduced.

Departments do not undertake systematic analysis of needs, and their service provision to CALD communities and achievement of related policy outcomes are not monitored, reported or held to account. This means departments are not able to demonstrate that their strategies and programs are designed in response to the needs of those communities. There are some limited exceptions to this in the form of individual programs—both mainstream and targeted.

The government is the largest purchaser—80 per cent—of Victorian translation and interpreting services, and their availability and accessibility is critical to providing responsive services to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. However, a key factor in effective service delivery is the availability and sustainability of the workforce.

Longstanding factors in the industry, such as low remuneration and inadequate job security, make it difficult to attract and retain interpreters. There are also gaps in availability, such as in regional and rural areas, and in the languages of emerging communities.

Monitoring and reporting

A key barrier to effective service planning and monitoring is the lack of accurate new settler data. It is difficult for the state to access Commonwealth data in a timely manner. The number of people undertaking secondary migration—that is, movement from one location to another in Victoria or from outside the state to a location in Victoria—is not known. Data collected by service providers and departments does not always capture whether clients are from a CALD background or their year of arrival. Notwithstanding these difficulties, there is limited evidence of service providers and departments generating their own data from clients and using this to improve service design and delivery. This means that departments cannot always be assured that their services are being effectively accessed by newly arrived migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

In the annual Victorian Government Initiatives and Reporting in Multicultural Affairs report, departments report on activity levels but not on whether these activities have been effective. For the first time, Victoria's new whole-of-government multicultural policy includes performance indicators. However, these indicators are based on existing data sets and cannot show whether client need is being effectively met. There are limited mechanisms to assure government more broadly that departments' efforts to provide appropriate services to the people who most need them are effective.

A whole-of-government approach

Victoria's new multicultural policy recognises the importance of a whole-of-government approach to multicultural affairs, including the provision of accessible and responsive services to CALD communities. However, departments work largely on their own in the area of multicultural affairs, with coordinated activities more likely to occur at a local rather than strategic level.

Since the release of the new multicultural policy in March 2014, OMAC has shown its commitment to working closely with departments on the development of their cultural diversity plans. However, under the current governance structure, neither OMAC nor VMC can hold departments to account. This means there is no mechanism or agency for requiring departments to implement Victoria's whole-of-government multicultural policy or to develop and report on progress against their cultural diversity plans.

There are some cross-agency mechanisms in place to support collaboration, including OMAC's secretariat role on the Multicultural Services Delivery Senior Officers Inter Departmental Group, but there is no overarching monitoring of:

- how much funding is going to CALD communities, whether this is being effectively used, whether it is going to those most in need and where the gaps might be

- how data is being collected, analysed and used to improve service access and effectiveness.

There is no whole-of-government mapping of the full range of CALD-related services and initiatives being provided by departments and agencies in Victoria, such as who is delivering these programs, where, to which groups, with what impact and what the service gaps might be.

There is lack of clarity around the roles and responsibilities of VMC and OMAC. There is some overlap in activities, such as grants management. This reduces opportunities for these two key multicultural bodies to be more coordinated and strategic in planning how to address the diverse and changing needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. VMC has little leverage with service delivery departments, which do their own consultations about programs. It is not currently fulfilling its role as advocate to the government on behalf of CALD communities because the information it collects about issues and challenges facing these groups is not being used to inform service delivery.

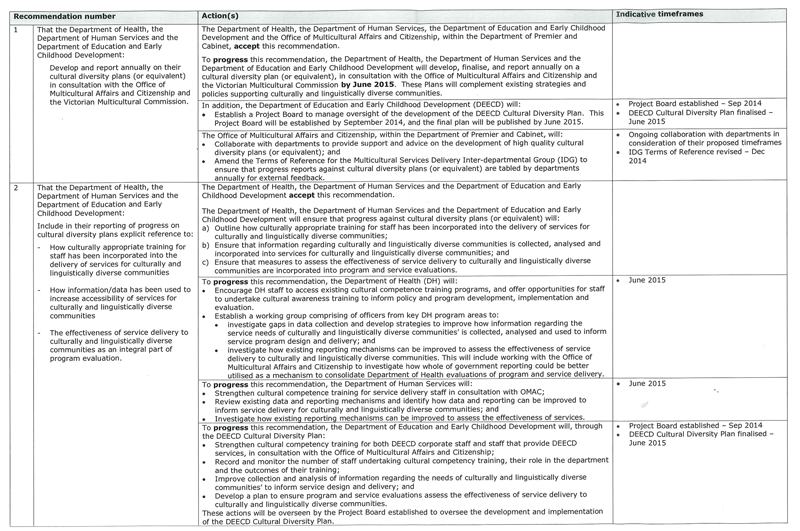

Recommendations

That the Department of Health, the Department of Human Services and the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development:

- develop and report annually on their cultural diversity plans—or equivalent—in consultation with the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship and the Victorian Multicultural Commission

- include in their reporting of progress on cultural diversity plans explicit reference to:

- how culturally appropriate training for staff has been incorporated into the delivery of services for culturally and linguistically diverse communities

- how information/data has been used to increase accessibility of services for culturally and linguistically diverse communities

- the effectiveness of service delivery to culturally and linguistically diverse communities as an integral part of program evaluation.

That the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship within the Department of Premier and Cabinet:

-

monitors and reports on departmental compliance with the reporting requirements of section 26 of the Multicultural Victoria Act 2011.

That the Department of Premier and Cabinet:

-

defines more clearly the roles and responsibilities of the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship and the Victorian Multicultural Commission

-

develops appropriate governance arrangements for the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship and the Victorian Multicultural Commission with robust and effective reporting and accountability mechanisms.

That the Victorian Multicultural Commission and Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship:

-

work closely together to monitor and report on overall departmental performance in relation to the provision of accessible, responsive and effective services.

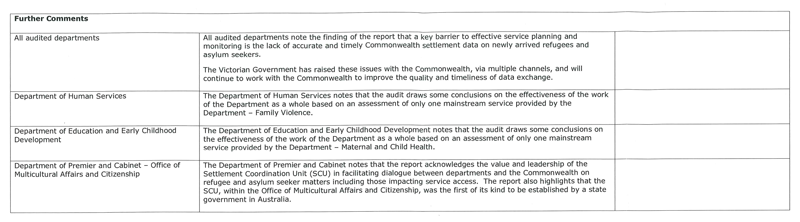

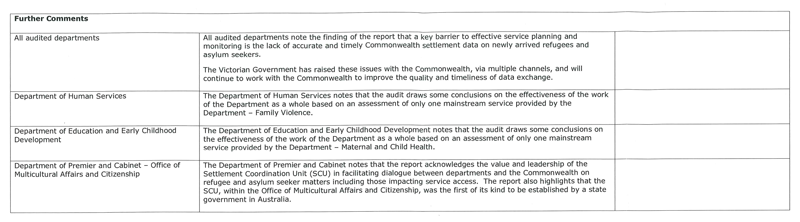

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Premier and Cabinet via the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship, the Victorian Multicultural Commission, the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development, the Department of Health and the Department of Human Services with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Providing accessible and responsive services to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers is critical if they are to settle effectively into a new country, rebuild their lives and contribute socially, economically, intellectually and culturally to the Victorian community. The economic, social and personal costs of not being able to access relevant services to meet basic health, education and other needs are high for both individuals and the community.

This audit assessed the accessibility of government services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. In the audit, reference is made to culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities as an umbrella term that includes migrants, refugees and asylum seekers as this is the term that is often used by departments and agencies.

1.2 Cultural diversity in Victoria

Victoria is one of the most culturally diverse communities in the world and accounts for around one-third of migrant settlement in Australia. In the past 10 years the proportion of the Victorian population born overseas has remained consistent—around 26 per cent. However, as Victoria's population has grown over the past 10 years, so too has the level of diversity. The number of Victorians born overseas as a percentage of the Victorian population has increased by 29 per cent from 2001 to 2011—from just below 1.1 million people to 1.4 million.

Photograph courtesy of the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship.

1.2.1 Migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

Between January 2007 and December 2013, 400 773 migrants settled in Victoria, including:

- 242 596 skilled migrants

- 126 374 people coming through the family reunion stream

- 31 735 humanitarian entrants.

Humanitarian entrants are refugees or people who have been subjected to refugee-like experiences in their country of origin. Under the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, a refugee is a person who, owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of their nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling, to avail themselves of the protection of that country or return to it.

Asylum seekers are people who have come to Australia seeking protection as refugees, but whose claim for refugee status has not yet been assessed. Asylum seekers include those who arrive by boat through unauthorised channels without travel documents—known as 'irregular maritime arrivals'—and those who arrive by plane, with or without valid travel documents.

There is no complete or reliable data on the number of asylum seekers in Victoria. At 3 March 2014, there were 24 000 asylum seekers on a Bridging Visa E in Australia, Of these, 8 680—36 per cent—were living in Victoria. This type of visa allows the holder to stay in Australian while they finalise their immigration matters or make arrangements to leave Australia.

At 3 March 2014, there were around 1 300 asylum seekers in community detention arrangements in Victoria, comprising vulnerable families, vulnerable adults and unaccompanied minors. There is no data currently available to capture the number of irregular maritime arrivals making secondary moves to Victoria from other states and territories or secondary migration within Victoria from metropolitan to rural and regional areas.

1.2.2 Distribution across Victoria

Figure 1A shows the six local government areas with the largest number and highest proportion of overseas-born residents, the largest number and highest proportion of Language other than English (LOTE) speakers, and the largest number of LOTE speakers with low English proficiency.

While the majority of local government settlement areas are in metropolitan Melbourne, at least 10 per cent of the population in Greater Shepparton (13.2 per cent), Swan Hill (12.4 per cent) and Greater Geelong (10 per cent) have a LOTE background.

Figure 1A

Population diversity by local government area, 2011

|

Population diversity |

Local government area |

|---|---|

|

Largest number of overseas born |

Casey, Brimbank, Greater Dandenong, Monash, Wyndham, Hume |

|

Highest proportion of overseas born |

Greater Dandenong, Melbourne, Brimbank, Monash, Hume, Whittlesea |

|

Largest number of LOTE speakers |

Brimbank, Greater Dandenong, Casey, Monash, Hume, Whittlesea |

|

Highest proportion of LOTE speakers |

Greater Dandenong, Brimbank, Maribyrnong, Monash, Whittlesea, Hume |

|

Largest number of LOTE speakers with low English proficiency |

Brimbank, Greater Dandenong, Hume, Monash, Whittlesea, Casey |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship report, Population Diversity in Victoria: 2011 Census Local Government Areas.

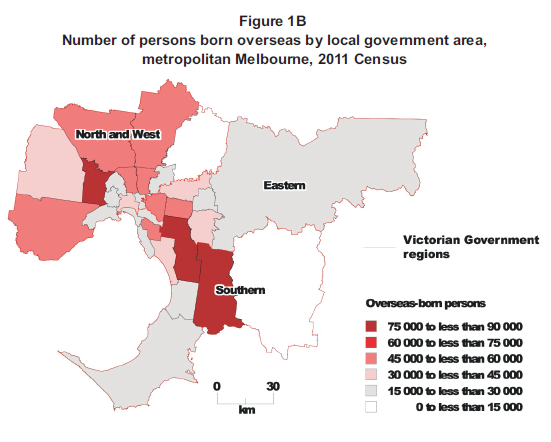

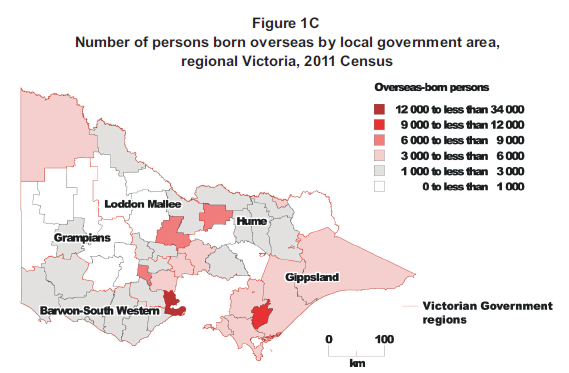

The largest numbers of humanitarian settlers in Victoria are from Afghanistan, Iran and Sri Lanka. Figures 1B and 1C show where different groups of people from CALD communities are concentrated.

Figure 1B

Number of persons born overseas by local government area, metropolitan Melbourne, 2011 Census

Source: Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship.

Figure 1C

Number of persons born overseas by local government area, regional Victoria, 2011 Census

Source: Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship.

1.3 Service needs

Migrants are typically less disadvantaged than refugees or asylum seekers because they have planned their entry to Australia and generally have better economic and social resources. However, any new arrival is likely to experience some challenges in understanding and accessing unfamiliar service systems.

Newly arrived migrants may have some service needs in common with refugees and asylum seekers, such as English language services, including substantial interpreter support, and services that are delivered in culturally appropriate ways. However, the service needs of refugees and asylum seekers are compounded by pre-settlement experiences, including during their journey to Australia. The demographic profile of refugees and asylum seekers has changed significantly in recent years, driven by changes to international circumstances and to Australian immigration policy. Many refugees and asylum seekers are arriving in Victoria with complex and chronic health conditions and higher levels of vulnerability.

For example, prior to their arrival, refugees and asylum seekers may have experienced some or all of the following:

- forced displacement

- prolonged periods in refugee camps or marginalisation in urban settings

- exposure to violence and abuse of human rights, including physical torture and gender and sexual-based violence

- loss and separation from family members

- deprivation of cultural and religious institutions and practices

- periods of extreme poverty, including limited access to safe drinking water, shelter and food

- severe constraints on access to health, education, employment and income support

- prolonged uncertainty about the future.

As a result, settlement needs for refugees and asylum seekers are significant and complex.

1.4 Roles and responsibilities

The Commonwealth Government has an overarching policy role relating to the services provided to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, including determining the numbers and composition of people entering Australia through the permanent immigration program and asylum seeker policy. The Victorian Government must work within these policies and constitutional and administrative parameters.

1.4.1 Commonwealth responsibility

Settlement services funded by the Commonwealth include:

- The Humanitarian Settlement Services (HSS) program, which provides initial support for refugees and humanitarian entrants for six to 12 months after entry into the program. In Victoria, the Red Cross and Adult Multicultural Education Services deliver the HSS program. The program includes reception and assistance on arrival, case coordination and cultural orientation, accommodation services and complex case support services.

- The Adult Migrant English Language Program, which provides 510 hours of free English language tuition to eligible migrants and humanitarian entrants in their first five years of settlement.

- The Settlement Grants Program, which provides funding to organisations to help refugees and newly arrived migrants with low English proficiency in their first five years of settlement.

Photograph courtesy of AMES.

The Commonwealth Government provides some health care to asylum seekers—for example, through Medicare—but does not guarantee the same level of health care as what is provided to refugees, who have the same entitlements to health care services as all other permanent residents of Australia. Thus, there are a number of Commonwealth-funded health programs and services that asylum seeker populations are unable to access. There are also a number of services where access is limited for both refugee and asylum seeker populations due to lack of interpreting services for those with low English proficiency.

1.4.2 State responsibility

State government departments deliver a broad range of mainstream and specialised services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers living in Victoria, including language services and cultural diversity planning. Victoria is the only jurisdiction to establish a Settlement Coordination Unit to proactively engage with the Commonwealth on immigration and humanitarian policy matters.

1.5 Legislative and policy frameworks

A range of Commonwealth and state legislation requires the provision of equal access to government services and for these services to be delivered in accordance with human rights obligations.

1.5.1 Legislation

The Multicultural Victoria Act 2011 (the Act) is the framework for a whole‑of‑government approach to building a cohesive, culturally diverse community. The Act establishes the principles of multiculturalism, including that:

- all individuals in Victoria are equally entitled to access opportunities and participate in and contribute to the social, cultural, economic and political life of the state

- Victoria's diversity should be reflected in a whole-of-government approach to policy development, implementation and evaluation.

The Act established the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC) as a statutory body to provide independent advice to the Victorian Government on multicultural affairs and citizenship matters. It also established reporting requirements for the VMC and government departments in relation to multicultural affairs.

The Equal Opportunity Act 2010, the Charter of Human Rights and Responsibilities Act 2006 and the Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2001 form the framework of laws in Victoria that protect people from discrimination and vilification.

1.5.2 Policy

The Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship (OMAC), situated in the Department of Premier and Cabinet, was established in 2011. OMAC drives Victorian Government multicultural policy and program implementation. It has responsibility for managing programs and projects such as the:

- Language Services Strategy

- Cultural Precincts Enhancement Fund

- Promoting Harmony and Multifaith/Interfaith initiatives

- Settlement Coordination Unit.

In March 2014, OMAC released a new multicultural affairs policy—Victoria's Advantage: Unity, Diversity, Opportunity—which is organised around three themes:

- maximising the benefits of our diversity

- citizenship, participation and social cohesion

- accessible and responsive services.

The policy commits to a whole-of-government approach to the delivery of responsive, culturally appropriate and accessible services and programs, and provides a set of performance indicators to track progress.

The Victorian Government guidelines on policy and procedures, Using Interpreting Services and Effective Translations, require departments and funded agencies to provide information to communities in their language and use interpreters and translators in delivering services. Updated policies and procedures for providing effective translations and using interpreting services were released on 8 April 2014.

A critical cross-department governance mechanism is the Multicultural Services Delivery Senior Officers Inter Departmental Group (IDG). The IDG reports to the Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship via OMAC. OMAC acts as the secretariat of the IDG, and the VMC also has a representative on the IDG.

The IDG meets four times a year, and its members are generally representatives at senior executive level from a wide range of departments and Victoria Police.

Other mechanisms supporting a whole-of-government approach are the Regional Management Forums (RMF). Departmental secretaries act as regional champions for allocated RMFs. There is also representation from departmental regional office directors. Regional strategy coordinators provide secretariat support for RMF meetings. These entities and mechanisms are explored further in Part 4 of this report.

1.6 Audit objectives and scope

The audit assessed the accessibility of government services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. In particular, it examined whether:

- departments have a comprehensive understanding or definition of 'effective access'

- departments have appropriate priorities, strategies and actions to facilitate effective access to services

- departments can demonstrate that services are accessible to migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

- whole-of-government structures and processes result in informed and coordinated service planning and delivery.

The following departments and agencies were included in the audit:

- Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

- Department of Health

- Department of Human Services

- Department of Premier and Cabinet

- Victorian Multicultural Commission.

Specific services within education, health and human services were selected for examination following an initial analysis of departmental policies, plans and reporting on service access, including three key programs:

- the Maternal and Child Health service, which is a universal and free service—Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

- Refugee Health Nurse Program, which is a targeted service delivered through community health centres—Department of Health

- family violence services, which are mainstream services that link to other services—Department of Human Services.

The audit focused on services which the general population is entitled to but also included targeted programs or strategies designed to support better access to services, and the responsiveness of those services in meeting the needs of migrants with low English proficiency, refugees and asylum seekers.

Photograph by Jorge De Araujo. By permission of the Victorian Multicultural Commission.

Access to government services was assessed in the Greater Dandenong and Greater Shepparton local government areas. These areas were selected because they have among the highest numbers of humanitarian arrivals in the metropolitan and non‑metropolitan areas, and reflect different location and refugee population characteristics. Figure 1D shows the diversity of the population in these areas. Greater Dandenong also ranked as the local government area with the highest proportion of overseas-born residents in the 2011 census.

Figure 1D

Diversity of Greater Dandenong and Greater Shepparton

|

Local government area |

Number of overseas-born residents |

Percentage of overseas-born residents |

|---|---|---|

|

Greater Dandenong |

76 127 |

56.1 per cent |

|

Greater Shepparton |

7 951 |

13.2 per cent |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship, Population Diversity in Victoria: 2011 Census Local Government Areas, 2013.

1.7 Audit method and cost

To assess the accessibility of government services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers the audit team:

- reviewed government policies, plans, strategies, program guidelines and reporting on access to services for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers

- analysed available data on service usage by migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, including the use of interpreters in service delivery

- interviewed departmental staff and key stakeholders, including consulting with service providers and peak bodies representing migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in metropolitan Melbourne and regional Victoria

- conducted two discussion groups with Community Guides who were former refugees.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The total cost of the audit was $420 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines departmental understanding of and responsiveness to the service needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

- Part 3 examines the adequacy of departmental monitoring and review.

- Part 4 examines the whole-of-government approach to the delivery of services for these groups.

2 Planning for effective and accessible services

At a glance

Background

A comprehensive understanding of the barriers to—and enablers of—effective access is needed if departments are to develop strategies and programs that meet the needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

Conclusion

While all service delivery departments can demonstrate some understanding of multicultural principles, including the need to cater for diversity, only the Department of Health can demonstrate at a strategic level that it understands the multiple and significant needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. The lack of current, comprehensive and evaluated cultural diversity plans, or their equivalent, reduces the capacity of departments to provide a consistent and efficient approach to service planning and provision.

Findings

- Departments engage with stakeholders to identify and address the service needs of culturally and linguistically diverse communities but this is not coordinated within or across departments.

- Departments are not required to report on cultural competency training even though this would give greater assurance that their staff have a sound understanding of the particular needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

- Departmental service agreements require cultural competency, but this is often limited to understanding of diversity rather than explicit requirements around understanding of migrant, refugee and asylum seeker needs.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health, Department of Human Services and Department of Education and Early Childhood Development develop and report annually on cultural diversity plans, or equivalent, and include in them explicit reference to:

- how culturally appropriate training for staff has been incorporated into the delivery of services for culturally and linguistically diverse communities

- how information has been used to increase accessibility of services

- the effectiveness of service delivery.

2.1 Introduction

To be effectively accessed by migrants, refugees and asylum seekers, services need to be physically accessible, have clear referral and registration processes, be affordable, be consistent with the beliefs and expectations of service users, and provide interpreters and translations as needed. In addition, users need to be aware of the existence and relevance of the services and these services need to be responsive to the diverse needs of users, which are likely to change over time.

2.2 Conclusion

While all departments can demonstrate understanding of multicultural principles, including the need to cater for diversity, only the Department of Health (DH) can demonstrate at a strategic level that it understands the particular needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

There is limited evidence to show that service design and delivery for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers has been informed by a sound and systematic assessment of client need. The lack of current, comprehensive and evaluated cultural diversity plans, or their equivalent, reduces the capacity of departments to provide a consistent and efficient approach to service planning and provision. Departments have a reasonable understanding of service need based mainly on stakeholder consultation rather than on systematic data collection and analysis.

2.3 Departmental understanding of client needs

In considering service access for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in Victoria, it should be noted that the Commonwealth Government has constitutional and administrative responsibility for immigration and humanitarian policy.

All audited departments advised that a lack of information from the Commonwealth on new settlers makes planning and allocation of adequate resources difficult. As a consequence of this lack of warning, departmental responses can be reactive to people arriving suddenly without adequate support from Commonwealth-funded programs. However, there is limited evidence of service delivery departments or service providers generating their own data from their current users and using this data to improve service design and delivery. This means that departments cannot always be assured that their services are being effectively accessed by newly arrived migrants, refugees and asylum seekers or that they are meeting client need.

2.3.1 Understanding of effective access and service needs

Except for DH, the service delivery departments do not explicitly refer to the service needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers in whole-of-department strategies. Instead, these groups are absorbed into a broader category of vulnerable communities, which means that the significant and complex needs of these groups may not be appropriately identified or addressed to support improved service access.

The Department of Human Services (DHS) has a clearly articulated, department-wide understanding of the components of effective access to mainstream services for vulnerable groups more broadly, as shown in its recently released Delivering for All— the Department of Human Services Access and Equity Framework 2013–17. While this framework does not explicitly refer to the complex needs of refugees and asylum seekers, there is evidence that the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities are understood at a programmatic level, with specific identification of this cohort in the areas of family violence, homelessness and child protection.

Like DHS, the Department of Education and Early Childhood (DEECD) does not have department-wide strategic documents that refer explicitly to the needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers but its understanding of the language needs of CALD communities—a significant barrier to service access—is reflected in the Victorian Government's vision for English as an additional language in education and development settings. This policy recognises the complex learning and settlement needs of refugees and asylum seekers who have experienced trauma or settlement issues. A dedicated English as an additional language unit focuses on services in schools, and this unit will soon also have responsibility for early childhood.

Photograph by Jorge De Araujo. By permission of the Victorian Multicultural Commission.

DH demonstrates a comprehensive understanding of effective access through its overarching Victorian Health Priorities Framework 2012–22 metropolitan and rural health plans. These plans include a commitment to increase the capacity of the health care system to design, implement and evaluate culturally and linguistically competent services for CALD communities. DH has also developed specific responses to make services more culturally appropriate and to improve access for refugees and asylum seekers because of the significant and ongoing physical health and mental health needs of these groups—particularly early in settlement.

DH's Refugee Health Nurse Program, which is targeted, and DEECD's Maternal and Child Health program and DHS's family violence services, which are mainstream services, were examined to identify whether departmental understanding of service need is demonstrated in local service delivery. While the principles of effective access are not stated explicitly, all three programs recognise the importance of:

- timeliness—in the form of early intervention

- coordinated services—links to other services as needed

- responsiveness—the ability to adapt to the identified needs of clients.

However, there is a need for ongoing, systematic data collection and analysis of client feedback to determine how accessible services are, how effective they are at meeting needs, and how planning and delivery could be improved.

2.3.2 Stakeholder consultation to identify needs

Stakeholder engagement occurs at whole-of-government, departmental, regional and local levels and is targeted at specific services, ethnic communities, issues and geographic locations. It includes formal planned consultation, ongoing engagement through membership of networks, and capacity building activities which are particularly important for migrant, refugee and asylum seeker communities.

Each of the audited departments consults with stakeholders to identify and address the service needs of CALD communities for particular programs. However, this consultation is not coordinated within or across departments to maximise usefulness. Efforts are duplicated and there is limited evidence of the collected information being shared where possible and appropriate across departments, or used to inform services or improve access.

For example, in one regional location several different agencies sought feedback from the same communities in a relatively short period. At least two of these consultations were about access to services. However, these consultations were not coordinated to minimise the burden on the communities or subsequently shared to maximise the usefulness of the information collected.

A coordinated stakeholder engagement strategy across government would enable a more strategic approach to information collection and analysis, better information sharing and a reduced 'consultation' load on some communities and their leaders.

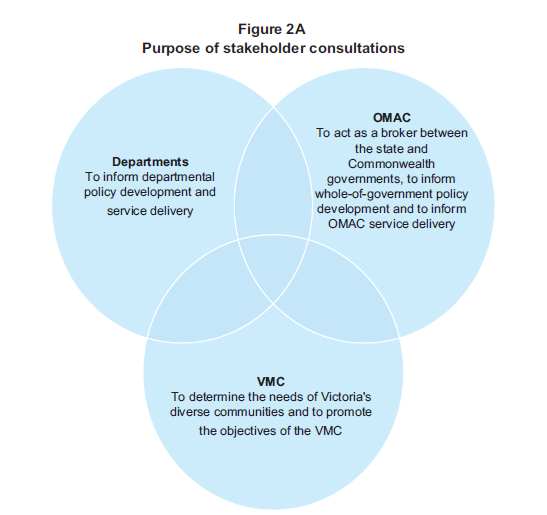

Figure 2A demonstrates the different purposes of the stakeholder consultation undertaken across government.

Figure 2A

Purpose of stakeholder consultations

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship

The Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship (OMAC) consulted with departments, communities and key sector stakeholders on the development of the new multicultural policy Victoria's Advantage: Unity, Diversity, Opportunity. To support implementation, OMAC recently developed a strategic engagement action plan which sharpens efforts to work with those departments that deliver policy, programs or services for CALD communities. However, OMAC has yet to develop the processes to assure effective cross-agency coordination and implementation.

OMAC's engagement with the Commonwealth, and its advocacy role, is valued by departments. OMAC acts as a broker between departments and the Commonwealth, which includes facilitating dialogue on refugee and asylum seeker matters through the Settlement Coordination Unit.

Victorian Multicultural Commission

Under the Multicultural Victoria Act 2011, the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC) is required to undertake systematic and wide-ranging community consultations which are to be reported back to the Minister for Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship. VMC's 2011 and 2012 Community Consultation Summary reports provide an overview of key issues and priority areas. The need for service providers and government departments to be more coordinated and strategic in planning to address the growing needs of CALD communities was a key theme in these reports.

However, the usefulness of the report findings are limited as issues raised are not subject to further investigation or analysis by the VMC to verify the underlying issues. The VMC advises that it does not have the resources to undertake such analysis. Consequently, departments have not taken any action in response to any department‑specific issues identified as they continue to do their own consultations on service delivery. This is a missed opportunity for VMC to provide a comprehensive rather than issue-specific perspective on the communities' needs, which in turn could enable a more coordinated whole-of-government approach to multicultural affairs where the issues have broader implications.

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

DEECD has a department-wide Stakeholder Engagement Framework designed to integrate its policies, strategies and day-to-day operations. The framework refers specifically to engaging CALD communities and recognises the need for services to be more culturally responsive and competent. DEECD's Refugee Education Support Program has demonstrated the use of effective stakeholder consultation to identify service need and enhance service accessibility.

Department of Health

DH has demonstrated extensive consultation in the development of key documents, specifically the Victorian refugee health and wellbeing action plan. Over 100 agencies were consulted, including eight community groups, and a consultation summary was produced. This consultation process has been promoted by the health sector as a good practice model that government should be using with refugee and asylum seeker communities.

DH has advised that it is prioritising a more strategic approach to stakeholder consultation in 2014, which will be undertaken through the Victorian Refugee Health Network. DH also has portfolio-specific strategies and principles for working in partnership with diverse community groups. DH's targeted stakeholder engagement at the local level has allowed for quick escalation of issues and responsiveness to client need. DH participation in the Victorian Refugee Health Network has allowed service delivery issues to be identified and good practice to be shared.

Department of Human Services

DHS has demonstrated effective stakeholder consultation to inform policies and programs for CALD communities. For example, in 2012, DHS provided translating and interpreting services so that CALD tenants could provide it with feedback on public housing. As part of Delivering for All, DHS has committed to holding stakeholder forums to assess whether it is meeting the needs of vulnerable communities and to identify new actions to deal with emerging issues.

2.4 Departmental planning and initiatives

2.4.1 Cultural diversity plans

Under the Multicultural Victoria Act 2011, departments are required to develop cultural diversity plans—or their equivalent—for the services and supports they provide for CALD communities. Departments are also required to report annually on progress being made against those plans but are not required to report on the effectiveness of initiatives undertaken.

There is also no central oversight of the plans. While OMAC's recent engagement with departments shows intent to provide input and guidance in the development of the plans, there are no opportunities currently for VMC to provide input, and even if there were, VMC advises that it is not resourced to take up such opportunities.

In the absence of a coordinated approach, the plans lack consistency:

- DEECD has no current cultural diversity plan following from its previous comprehensive plan for 2008–10. There are language policies but no whole‑of‑department cultural diversity plan or equivalent strategic approach. Instead, there is evidence of portfolio-specific planning to address the needs of CALD communities in the early childhood service and schools sectors.

- DH has several CALD strategies and plans to cater for its different health service sectors. However, there is no overarching framework or strategy that identifies consistent elements or expected minimum obligations that need to be addressed.

- DHS's Delivering for All framework incorporates cultural diversity as a key component of service delivery. DHS does not have a current cultural diversity plan but is reviewing its equivalent, the DHS Cultural Diversity Guide, in consultation with OMAC. DHS advises that this will contain strategies for service planning and highlight good practice models for use by both DHS and service providers.

One example of a department-wide approach to cultural diversity planning is DH's draft Victorian Refugee and Asylum Seeker Health Action Plan, which is scheduled for release in 2014. This document highlights accessibility as the first of six priority areas and identifies actions to increase the cultural responsiveness of the Victorian health care system. DH has advised that it will set priorities to ensure that refugees and asylum seekers achieve health outcomes comparable to the broader population. There is no equivalent department-wide plan for DEECD or DHS.

Cultural competency training

'Cultural competency is more than just training. It's about responding in a timely way to complaints, ensuring information is available—it's how people are held accountable to make sure there's universal competency and safety'.

—Worker, refugee health services, 2013.

Departments are not explicitly required to report annually on cultural competency training, although this is within the scope of annual reporting against progress of the cultural diversity plans.

Department service agreements with funded agencies identify relevant policies, service standards and guidelines that these agencies are expected to comply with in delivering services. Assurance for this occurs through various accreditation, review and reporting processes. However, these accreditation standards generally refer to multicultural principles of tolerance and diversity rather than referring explicitly to cultural competence as it relates to the particular needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. This means that service delivery departments have limited assurance that the staff of funded agencies have sufficient cultural sensitivity to be effectively meeting the needs of migrants, refugees and asylum seekers.

Because there is no requirement to report on cultural competency there is a lack of clarity and transparency about whether and how frequently departmental staff at all levels—including those in leadership positions, and in central and regional offices—are receiving any kind of training. The audit did not assess the specific gaps in departmental staff training or, in the case of DH, the requirements of health service boards for a culturally competent workforce. Requiring departments to report annually on their cultural competency training would help embed multicultural awareness and increase accountability regarding this important component of effective access.

Department of Education and Early Childhood

DEECD has various sector-specific accreditation standards that require service providers to provide cultural competency training to staff. The 2009 revised Maternal and Child Health Program Standards require culturally competent service delivery. In 2009, DEECD engaged the VMC to design and deliver a series of training and communication resources to increase cultural awareness among professionals who deliver early childhood services.

The training was delivered to 255—which is 28.3 per cent—Maternal and Child Health nurses across Victoria in 2010 and 2011. The sessions, which were subsequently taken over by OMAC after VMC was restructured, provided information on the use of language services, improving cultural awareness, and cross-cultural communication. Subsequent evaluations highlighted the need for a more comprehensive strategy to address cultural practice issues, include more information about ethno-cultural groups and provide further opportunities for cross-cultural training.

Department of Health

There are various accreditation standards service providers are required to comply with in order to obtain funding, as well as reporting mechanisms that provide DH with assurance that service providers are culturally competent.

DH's Refugee Health Nurse Program is a good example of how training has been used to improve service accessibility. Training has evolved in response to participant needs and feedback. The Victorian Foundation for Survivors of Torture (Foundation House) provides training to Refugee Health Nurses in coordination with the Refugee Health Nurse Facilitator. Both Foundation House and the Refugee Health Nurse Facilitator are required to report annually to DH on activities to promote the professional development of Refugee Health Nurses.

The training began in 2006 with a two-day introductory training course and seminars throughout the year. This has since been expanded to include sessions on responding to the psychosocial impacts of torture and trauma, paediatrics, youth and adolescent needs, health and wellbeing, and supporting families. There is regular evaluation, including feedback on whether participants have gained confidence in:

- understanding the traumatic experiences of refugees

- identifying possible survivors of torture and trauma

- outlining relevant services for refugee survivors and referral processes

- using interpreters and effectively communicating with people from CALD backgrounds

- working cross-culturally.

This training is also available to nurses working with refugees and asylum seekers who are not Refugee Health Nurses—i.e. Maternal and Child Health nurses and community health nurses—which contributes to capacity building for mainstream providers as well.

Department of Human Services

In 2012, DHS implemented the Department of Human Services Standards evidence guide, streamlining departmental accreditation requirements by replacing former program-specific standards. Cultural competency requirements are set out in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Department of Human Services Standard 3—Wellbeing

|

Criteria |

Common evidence indicators |

|---|---|

|

3.2—People actively participate in assessment of their strengths, risks, wants and needs |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Department of Human Services Standards evidence guide, December 2011.

DHS-funded family violence services are required to deliver their services in line with the Common Risk Assessment Framework and the Domestic Violence Code of Practice for Specialist Family Violence Services for Women and Children, both of which provide practical information for working with women and children from CALD communities.

DHS funds the InTouch Multicultural Centre against Family Violence to provide secondary consultations to other family violence and mainstream services. InTouch provides free, culturally sensitive services to women and children from CALD communities who are experiencing family/domestic violence. InTouch case managers speak 23 different languages and almost all are migrants or refugees themselves.

Building local cultural awareness

Building cultural awareness is not only about staff training. Figure 2C provides an example of how community members have been supported to increase their understanding of people from CALD backgrounds.

Figure 2C

Breaking down cultural barriers

|

In Shepparton, the ethnic council offers regular bus tours to community leaders of new and emerging communities to break down cultural barriers. The bus tours take community leaders to visit police stations, hospitals, and the local council. People from agencies and government are also taken on a cultural tour. Each bus takes around 50 people. On one tour, for example, participants were taken to an Aboriginal property, a football club, mosques, and a Sikh temple. Most people on the bus had never been to such places before or met with people from CALD backgrounds on a one-to-one basis. At an Iraqi mosque, a couple of men from the community talked about the importance of the building, how the community is operating and issues they experience. The bus tours have been very popular, and there are plans to continue this service. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Ethnic Council of Shepparton and District Goulburn Valley Settlement Planning Committee, 2013.

Culturally appropriate information

The government is the largest purchaser—80 per cent—of Victorian translation and interpreting services. The availability and accessibility of these services is critical to providing responsive services. However, a key driver of delivering a responsive service is the availability and sustainability of the workforce. There is a growing need for professional interpreters in new and emerging languages, as well as in established languages—studies show there is limited access to interpreters in rural and regional areas and in specialised areas such as legal and health interpreting.

To meet growing demand, the Multicultural Language Services program received $2 million over four years in the 2011–12 Budget to increase the supply and quality of interpreters in Victoria. A 2013 review of the program identified several issues:

- longstanding factors in the industry, such as low remuneration and inadequate job security, make it difficult to attract and retain interpreters

- insufficient focus on improving the supply of interpreters and translators in established languages

- the need for a compliance component in the new policy and guidelines to increase accountability for the use of interpreters and translators.

In 2011–12, the total identified expenditure by departments on interpreting and translating services, including expenditure through funded agencies, was $27 263 484—a 4.26 per cent increase on the 2010–11 total expenditure of $26 149 230. However, because reporting is based on the cost of service provision, it does not identify whether the services provided are being used by those clients who need them or whether services are accessible, available, or meeting demand. For example, stakeholders have noted the difficulties in understanding an interpreter over the phone in the absence of facial expression, tone and gestures and body language. For some cultures this can mean that the provision of telephone services is not an effective method of delivery.

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

DEECD has guidelines for use of interpreting and translation services in Victorian government schools and department-funded early childhood and support services. All Maternal and Child Health services have access to interpreter services through a DEECD-funded statewide interpreter service for families who require this.

In addition, DEECD's employment of Multicultural Education Aides (MEA) plays a critical role in improving accessibility to schooling. Schools can employ part-time MEAs to enable a broader range of languages to be covered locally. In 2014, around 357 equivalent full-time (EFT) positions are being funded statewide. DEECD does not formally monitor the effectiveness of the MEAs but relies on anecdotal evidence from schools about their contribution to effective access.

Department of Health

DH has prioritised improving the health literacy of refugees and asylum seekers. A key issue is the need to translate information for people who are not literate in their own language. Additional funding for language services in health has been provided in the last two State Budgets. This has included:

- attaching language services to each new EFT position for Refugee Health Nurses, allied health professionals and mental health counselling positions through a 2013–14 Budget measure

- additional funding to meet the increased demand for interpreting services

- funding for the redevelopment of the Health Translations Directory website which provides translated health information for health professionals and consumers.

The 2013–14 State Budget flexible language services funding attached to each funded service provider position—for mental health counselling, allied health and Refugee Health Nurse positions—is in recognition of the high use of interpreting services by newly arrived populations with limited or no English.

This is a positive and responsive investment as a 2013 report by Foundation House into promoting the engagement of interpreters in Victorian health services recommended providing a budget allocation for interpreting services with all new funding for health services, similar to the model used for the Refugee Health Nurse Program.

DH is currently conducting a statewide public consultation on the development of a Health Literacy and Consumer Health Information policy statement which will be part of a new statewide consumer, carer and consumer participation policy in 2015.

Department of Human Services

DHS standards require service providers to provide information in a format that helps people understand their rights and responsibilities; to be aware of different language, cultural and communication needs; and to use a range of alternative information and communication methods to enhance their understanding.

DHS has developed an online training resource 'Making the Connection' to assist staff to work with interpreters. DHS is also participating in the OMAC-led and funded Multilingual Government Information Online Pilot Project. As part of the OMAC initiative, DHS sought input from the InTouch Multicultural Centre Against Family Violence to advise on suitable material for translation into 12 community languages. A pilot website and best practice guide are currently being developed and this good practice model is to be shared with other departments.

Recommendations

That the Department of Health, the Department of Human Services and the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development:

- develop and report annually on their cultural diversity plans—or equivalent—in consultation with the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship and the Victorian Multicultural Commission

- include in their reporting of progress on cultural diversity plans explicit reference to:

- how culturally appropriate training for staff has been incorporated into the delivery of services for culturally and linguistically diverse communities

- how information/data has been used to increase accessibility of services for culturally and linguistically diverse communities

- the effectiveness of service delivery to culturally and linguistically diverse communities as an integral part of program evaluation.

3 Monitoring and reporting on service accessibility

At a glance

Background

Effective data collection enables departments and funded agencies to improve their understanding of the needs of their client groups. Monitoring service accessibility enables issues affecting access to be addressed in a timely and effective way. Reporting on service accessibility holds government departments and service providers accountable for their performance.

Conclusion

Poor data collection and analysis of service delivery means that departments and service providers do not always know if their services are being effectively accessed by migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Current reporting requirements do not hold service delivery departments sufficiently accountable for their performance with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities.

Findings

- A key issue for agencies is the lack of accurate new settler data to inform service planning.

- Background CALD information and year of arrival are not always captured by departments and service providers.

- Departments and service providers do not systematically collect and analyse data from clients to assess accessibility and effectiveness of service provision.

Recommendation

That the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship within the Department of Premier and Cabinet monitors and reports on departmental compliance with the reporting requirements of section 26 of the Multicultural Victoria Act 2011.

3.1 Introduction

In order to know if a service is accessible and responsive to need, relevant data needs to be collected, analysed and used to improve planning and delivery. Poor data collection and analysis of service delivery makes service planning difficult. Reporting on outcomes holds government departments and funded agencies accountable for their performance. Without this, it is difficult to be assured that those most in need are being appropriately supported.

3.2 Conclusion

Limited settlement data is made available by the Commonwealth, which affects the capacity of local government areas to plan adequately for new arrivals. However, departments and funded agencies could be making better use of their service interactions to collect feedback from clients on service accessibility and responsiveness. Such data is not collected systematically or routinely. This means that departments do not know if services are accessible and effective for migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. For universal services, monitoring accessibility for these cohorts helps to identify if there is a need for targeted programs to support access.

3.3 Departmental monitoring and evaluation of outcomes

Departments typically measure service utilisation and/or expenditure. They report annually on activity levels but not on whether these activities have been effective. There are some examples of departments identifying and addressing a level of unmet need or barriers to accessibility. However, there are limited mechanisms for regular reporting to assure government more broadly that appropriate services are being effectively delivered to the people who most need them.

A key issue is the lack of regular or accurate settlement data on newly arrived refugees and asylum seekers to inform service planning. Departments and service providers all commented on the challenges this presents. Yet they also have a responsibility to collect information from service users from culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) communities to make sure their significant needs are being met.

Effective data collection enables departments and funded agencies to improve their understanding of the needs of their client group and monitor the accessibility of the services they provide. Yet there are currently gaps in the kind of data collection and analysis that would enable departments and the Office of Multicultural Affairs and Citizenship (OMAC) and the Victorian Multicultural Commission (VMC) to better understand whether client groups are effectively accessing services.

3.3.1 Data limitations

There are several issues affecting the ability of departments and service providers to collect and analyse data for the purposes of service planning and delivery.

Unavailability of Commonwealth data for state planning purposes

This is a key issue raised by agencies during the audit. Data from the Commonwealth on refugee and asylum seeker arrivals and settlement locations is very limited. The Commonwealth does not routinely provide states and territories with accurate or timely data on settlement cohorts, including 'irregular maritime arrivals', refugee arrivals offshore, skilled and student visa holders and unauthorised plane arrivals. Commonwealth datasets are not integrated across systems, including the following datasets:

- immigration—Department of Immigration and Border Protection

- humanitarian settlement—Department of Social Services

- Asylum Seeker Assistance Scheme and Community Assistance Support—Centrelink

- Medicare health—Department of Health.

This makes it difficult for local government areas to adequately plan and prepare for new arrivals. While Commonwealth data is critical for effective local service planning, service providers and departments could also be collecting information from service users to identify whether services are being accessed effectively and meeting need.

Photograph by Jorge De Araujo. By permission of the Victorian Multicultural Commission.

Lack of data about secondary migration within Victoria

It is difficult to estimate the numbers of people who relocate in Victoria. This includes people from outside and inside Victoria who move to new locations within the state. While the Department of Immigration and Border Protection has access to the systems that could provide the most accurate and comprehensive data about secondary migration of asylum seekers, and the Department of Social Services has access to information about refugees, this information is not currently provided by the Commonwealth to states and territories.

Reliance on outdated census data

The most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) census data is from 2011. This is now outdated, particularly for locations that have experienced rapid growth in new settler arrivals. Despite this, with no readily-available Commonwealth data, departments and OMAC rely mainly on ABS census data. This is useful for longer‑term planning, however, there is limited readily-available data to manage and plan for migrant and humanitarian arrivals in the short to medium term.

Inadequate identification of CALD background

Data collected by service providers and departments does not always capture whether clients are from a CALD background. For example, CALD information has not been systematically collected and analysed on children and families in Victoria's child protection system. This means that families from a CALD background may not always gain access to the services that would benefit them. In general, the disclosure of CALD background by a service user is voluntary—this means systematic collection of CALD data will be limited.

Lack of data regarding country of origin and year of arrival