Accessibility of Mainstream Services for Aboriginal Victorians

Overview

The Victorian Aboriginal population was around 47 000 at the 2011 census, making up around 0.9 per cent of the overall population. Aboriginal Victorians experience considerable disadvantage compared to the non-Aboriginal population, with higher perinatal mortality, higher disability rates and lower literacy and numeracy outcomes.

The Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18 (VAAF) outlines criteria to apply to service design and delivery to ensure that services are accessible, and a set of targets relating to closing the gaps and ensuring that Aboriginal Victorians receive equitable access to mainstream services.

This audit assessed the accessibility of mainstream services such as hospitals, maternal and child health services, schools and kindergartens, and community and public housing for Aboriginal Victorians.

The audit found little improvement in outcomes, and in some cases, the gap has worsened. However, access to hospitals, maternal and child health services, housing services and kindergarten has improved. An absence of effective leadership and oversight has affected mainstream service delivery over many years. The Secretaries’ Leadership Group on Aboriginal Affairs is responsible for overseeing implementation of VAAF and has not been effective. Without strengthened oversight and improved collaboration between departments, VAAF will not be implemented effectively and its intended outcomes are not likely to be achieved.

Accessibility of Mainstream Services for Aboriginal Victorians: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER May 2014

PP No 325, Session 2010–14

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Accessibility of Mainstream Services for Aboriginal Victorians.

The audit examined the access to mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians that are provided or funded by government departments, and it assessed whether departments can demonstrate how improved access has contributed, and is expected to contribute to improved outcomes.

I found that despite departments developing programs aimed at increasing access, outcomes have not improved significantly and in some cases the gap has worsened. A lack of broad consultation and problems with data reliability mean that departments cannot be assured they understand the needs of Aboriginal Victorians.

With the exception of the Department of Health, departments do not know if the work they are undertaking is improving access, and why outcomes are not improving. As a result, departments cannot be assured they are on track to meet the targets in the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework. There is a lack of effective oversight and coordination by the Secretaries' Leadership Group and the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria. Without improvements in these areas, it is unlikely the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18 will be effectively implemented.

I have made eight recommendations, six targeted at the Departments of Health, Human Services, and Education and Early Childhood Development, and two targeted at the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria in the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

Yours faithfully

John Doyle

Auditor-General

29 May 2014

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Andrew Evans —Sector Director Peter Rorke — Team Leader Sophie Fisher — Analyst Pablo Armellino — Graduate Analyst Chris Sheard —Engagement Quality Control Reviewer |

Victoria's Aboriginal population is small relative to other parts of Australia. The 2011 census reports that there are around 47 000 Aboriginal people in Victoria — 0.9 per cent of the total Victorian population — and 55 per cent of Aboriginal Victorians are under 25 years of age, compared to 32 per cent of the non-Aboriginal population.

Despite some improvements, Aboriginal Victorians are still facing significant disadvantage compared to the rest of the Victorian population, and they access many mainstream services at lower rates than the rest of the population. Gaps persist in many areas including early childhood development, health outcomes, income and employment. Addressing these gaps is vital to improve life outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians, and ensure they receive equitable access to services they are entitled to.

This audit assessed the accessibility of mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians, including whether departments can demonstrate how improved access has, and is expected to, improve outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians. The audit focused on whole‑of-government and departmental policies, programs and strategies, as well as outcomes, covering early childhood, health and human services.

My audit found little improvement in outcomes and in some cases, the gap between Aboriginal Victorians and the rest of the population has worsened. However, access to hospital services, maternal and child health services, public housing services and kindergarten has improved.

Many of the audit findings reflect similar issues identified in past VAGO reports and various departmental reviews relating to disadvantaged sections of the population. These groups have differing needs and challenges in accessing mainstream services. In order to ensure they receive the same opportunities as the rest of the population, departments and agencies need to be well informed about the needs of disadvantaged groups, including Aboriginal people, and target their services and programs accordingly.

In common with other whole-of-government initiatives that focus on vulnerable Victorians, there is an absence of effective leadership and oversight in Aboriginal affairs which has affected mainstream service delivery over many years. The Secretaries' Leadership Group on Aboriginal Affairs (SLG) is responsible for overseeing implementation of the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18 (VAAF), and this has not been effective. To ensure that services are accessible — and to achieve its intended outcomes — VAAF needs to be implemented with strengthened oversight and improved collaboration between departments.

I have made key recommendations for the Department of Premier and Cabinet through the SLG to provide more active leadership and direction to make sure that departments comply with the requirements of VAAF. I am pleased DPC has accepted these recommendations and the SLG has recently created a new Inter-Departmental Aboriginal Inclusion Working Group. It is important this group, the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria (OAAV) and the SLG actively oversee progress in developing and implementing plans and actions to improve Aboriginal inclusion.

The report also contains a set of recommendations that apply to all government agencies that may be responsible for providing services for Aboriginal Victorians. I am confident that adopting these recommendations will assist agencies to 'close the gap', thus improving the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal Victorians.

I intend to revisit the issues that my office has identified in this report to ensure they are being appropriately addressed.

Finally, I wish to acknowledge and thank the staff of OAAV and the departments of Education and Early Childhood Development, Health and Human Services for their assistance and cooperation during this audit.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

May 2014

Audit Summary

The Australian Aboriginal population faces considerable disadvantage when compared to the non-Aboriginal population. For example, there are significant gaps in early childhood development, lower participation in maternal and child health services and kindergarten, poorer health status and shorter life expectancy, higher disability rates and comparatively lower literacy and numeracy outcomes. Despite some recent improvements, these gaps are still prevalent in Victoria.

Victoria's Aboriginal population is small relative to other parts of Australia. The 2011 census reports that there are around 47 000 Aboriginal people in Victoria — 0.9 per cent of the total Victorian population — and 55 per cent of Aboriginal Victorians are under 25 years of age, compared to 32 per cent of the non-Aboriginal population.

Victorian Aboriginal Health Service (Fitzroy). Photograph courtesy of Tobias Titz.

In November 2008, the Council of Australian Governments agreed to the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA), which commits all Australian governments to achieving specific closing the gap targets. To address its commitments under NIRA, the Victorian Government has developed the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18 (VAAF), which builds on the previous Victorian Indigenous Affairs Framework 2010–13, as the primary whole-of-government framework for Aboriginal people. VAAF outlines criteria designed to provide more effective access to services and improve outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians.

This audit examined the access to mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians provided or funded by government departments, and it assessed whether departments can demonstrate how improved access has contributed, and is expected to contribute to improved outcomes. The audit focused on whole-of-government and departmental policies, programs, strategies and outcomes, covering early childhood, health and human services and excluding child protection and youth justice.

Conclusions

Despite departments developing programs aimed at closing the gap between the Aboriginal population and the non-Aboriginal population, there has been little improvement in outcomes, and in some cases the gap has worsened. However, there is improved service access as a result of programs such as the Aboriginal Quitline and Aboriginal Health Promotion and Chronic Care programs, and in some areas such as maternal and child health.

An absence of effective leadership and oversight has adversely affected the delivery of mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians over many years. The Secretaries' Leadership Group on Aboriginal Affairs (SLG) is responsible for overseeing the implementation of VAAF. This arrangement does not appear to have been effective, and there is limited evidence that the SLG is fulfilling its intended role. Crucially, it appears unable to ensure that VAAF is applied as intended across government. Similarly, the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria (OAAV) does not oversee departmental activities. OAAV advised it does not have the authority to direct the way departments undertake their work and sees its role as one of coordination and facilitation. There is a lack of accountability for delivery of actions because it is up to individual departments to develop and implement their own plans, with limited oversight. However, a new Interdepartmental Aboriginal Inclusion Working Group is being created to provide for regular departmental engagement and oversight of plans and associated processes.

OAAV was not able to quantify the total amount spent by the Victorian Government in relation to services for Aboriginal people, and some departments had difficulty providing complete financial information. Therefore, the total amount of funding is not clear, and the lack of complete information makes effective monitoring of expenditure problematic.

Departments have developed a range of plans, strategies and programs aimed at improving access to services for Aboriginal people. Most of these have been in place for five to 10 years and in the case of the Department of Health (DH), some for over 20 years. Since the introduction of VAAF in 2012, departments have not reviewed or updated their plans to reflect the framework's focus on addressing service access. All departments are required to complete their Aboriginal inclusion action plans by the end of August 2014. Originally, they were due to be developed by the end of 2013, and significant work remains for these plans to identify and address barriers to access to comply with VAAF criteria. The plans should also include clear target measures and milestones, and detail the requirements for monitoring, evaluating and reporting on access and outcomes.

There is significant scope for departments to improve their monitoring, evaluation and reporting of outcomes of Aboriginal service delivery strategies and programs. Except for DH, there is little evidence that departments undertake robust evaluations to assess the achievement of outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians.

Across all departments, weaknesses in the completeness and reliability of data mean that it is difficult for them to accurately measure the achievement of outcomes. This diminishes their ability to effectively monitor, evaluate and report progress on service delivery plans. While there are challenges in obtaining data on the Aboriginal population, more should be done to improve the completeness and reliability of information, including data on population levels. Without improvements to the completeness of data, departments cannot be assured that all Aboriginal Victorians who are eligible for particular services are able to access them.

A lack of effective collaboration and coordination in planning and service delivery between the departments and service providers, as well as at service delivery level between local providers, creates difficulties for Aboriginal people, who have to navigate multiple service providers to access services. SLG is tasked with coordination and collaboration between departments, but there is limited evidence this is occurring.

Findings

Oversight and leadership

A lack of effective oversight and leadership has adversely affected the delivery of mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians. Given the deficiencies identified in this audit — such as with Aboriginal action plans and strategies, data collection and sharing, and program evaluations — there is a pressing need for SLG and OAAV to provide more active leadership, direction and oversight to ensure that departmental programs and strategies identify and address the needs of Aboriginal Victorians to facilitate increased access and improved outcomes.

Consultation and engagement

There are a number of ways in which government departments consult and engage with Aboriginal organisations and people. However, there is a lack of broad consultation, and this limits community representation and is time consuming for stakeholders who are on multiple committees.

Consistent with VAAF and Council of Australian Governments (COAG) principles, broad consultation includes engaging Aboriginal community members and organisations, as well as mainstream service providers, at all stages of program development, implementation and evaluation to ensure diverse representation.

Many organisations — including Aboriginal community controlled organisations — that provide feedback and advice to departments are directly funded by those departments, which may diminish their capacity to provide constructive feedback. There is scope for greater use of community consultation, which would strengthen overall consultation processes.

Complete and reliable data

There are challenges for the audited departments in obtaining complete and reliable data to identify needs, develop plans, evaluate programs and report outcomes — particularly data relating to population levels. Despite these challenges, DH has had data improvement processes in place for a number of years through strategies to improve identification in public hospitals. The Department of Human Services (DHS) more recently has moved to enhance data collection procedures to improve completeness and reliability of datasets particularly relating to service accessibility for Aboriginal Victorians, while the Department of Education and Early Childhood (DEECD) is improving data collection in its maternal and child health service.

There is a clear imperative for departments to improve their data collection methods and information sharing practices. Data sharing across departments is limited. Without complete and reliable data, departments cannot be assured they are meeting the service needs of Aboriginal people.

Plans, programs and strategies

All departmental secretaries have agreed to finalise Aboriginal inclusion action plans by the end of August 2014, but significant work remains for these plans to identify and address barriers to access.

Overall, the quality of the audited sample of plans and strategies for the delivery of services to Aboriginal Victorians in the audited departments was poor. They did not meet many of the better practice criteria established in government policy framework documents. Consequently, there is considerable scope for departments to improve their plans and strategies under VAAF.

Collaboration and coordination

There is a lack of effective collaboration and coordination in planning and service delivery between the departments and service providers, as well as at service delivery level between local providers, despite this being a role of SLG. The successful implementation of VAAF requires improved cross-government coordination. Feedback from Aboriginal stakeholders, community organisations, service providers, and departmental officers indicated that many problems with government services are the result of a 'siloed' approach to service delivery that can impede access to services and negatively impact outcomes. This creates difficulties as users have to navigate multiple service providers to access services.

According to its terms of reference, SLG is responsible for strengthening coordination and collaboration between departments. However, there is limited evidence this is occurring and there is considerable scope for improvement in this area.

Access to services

Both DH and DEECD measure access to programs, and can demonstrate improvements in accessibility in some services. At DH this is the case in a range of areas, while at DEECD, gaps in participation in maternal and child health and kindergarten have narrowed. However, this data needs to be viewed with caution, because longer-term trends need to be considered rather than short-term increases or decreases in participation and attendance. DHS can demonstrate increased access to public housing — although overcrowding in public housing has increased — and to homelessness services.

Evaluating outcomes

Despite the development of programs aimed at increasing access to close the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Victorians, there has been little improvement in outcomes, and in some cases the gap has worsened.

Without effective evaluations, departments cannot be assured they have achieved or are achieving targets under VAAF. Only DH demonstrated a rigorous program of evaluation that assessed the achievement of outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians, and this has been in place for a number of years.

While DEECD and DHS undertake some evaluations, neither could demonstrate a comprehensive evaluation regime for Aboriginal programs, and it is difficult to understand how these departments can assure themselves that plans, programs and strategies are achieving positive outcomes for Aboriginal people.

Monitoring and reporting

The Victorian Government Aboriginal Affairs Report is submitted annually to the Victorian Parliament. OAAV collects information from departments to publish in the report. However, this report provides only a high-level analysis of outcomes against targets in key areas and some basic data on trends. The information is not always reliable because it depends on data provided by departments, which is of varying quality. Departments also report to COAG, on their progress towards outcomes for closing the gap between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Victorians.

Although departments report on results of their various programs, there is significant scope to improve public reporting on the accessibility and outcomes of mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians.

Funding of services

Quantifying the Victorian Government's expenditure on mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians is difficult. DEECD was not able to provide specific details on expenditure for Aboriginal Victorians in maternal and child health, and DHS was unable to provide specific funding details in relation to access of its mainstream services by Aboriginal Victorians.

Although OAAV is the central policy group for Aboriginal affairs, it was unable to provide any information on the amount of funding provided for programs related to services for Aboriginal people across Victorian Government departments.

Recommendations

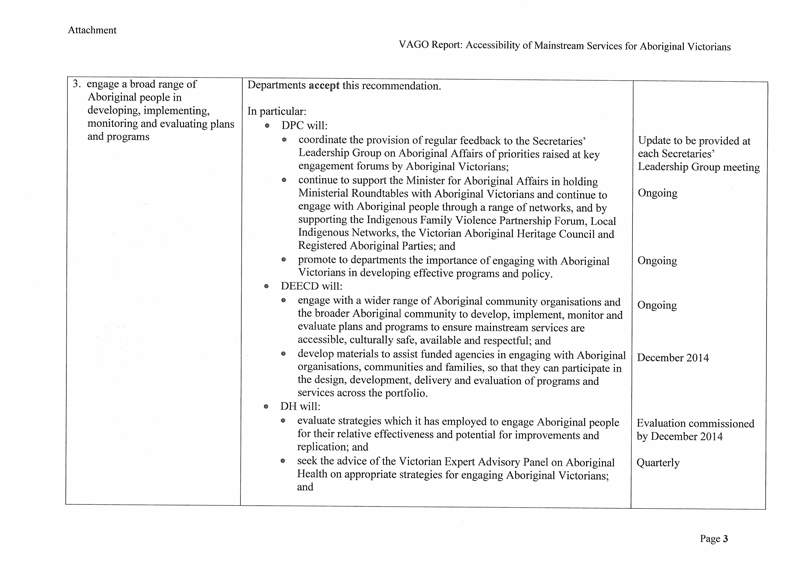

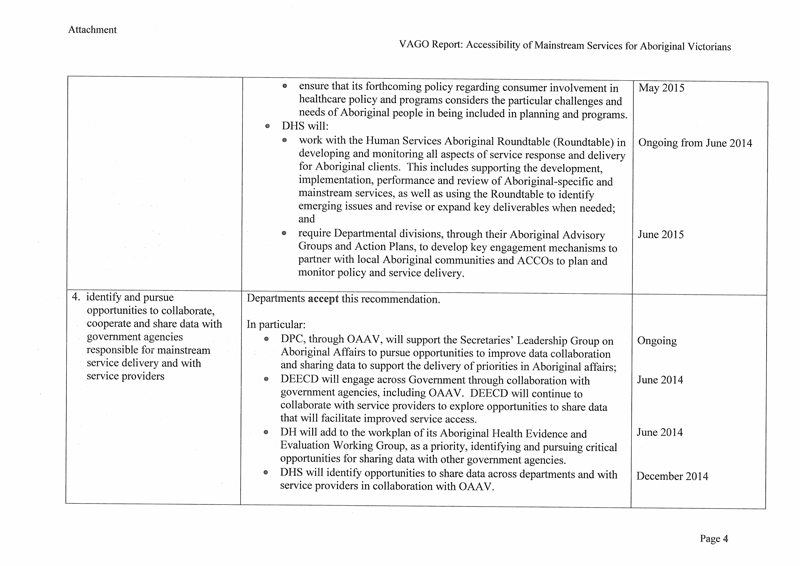

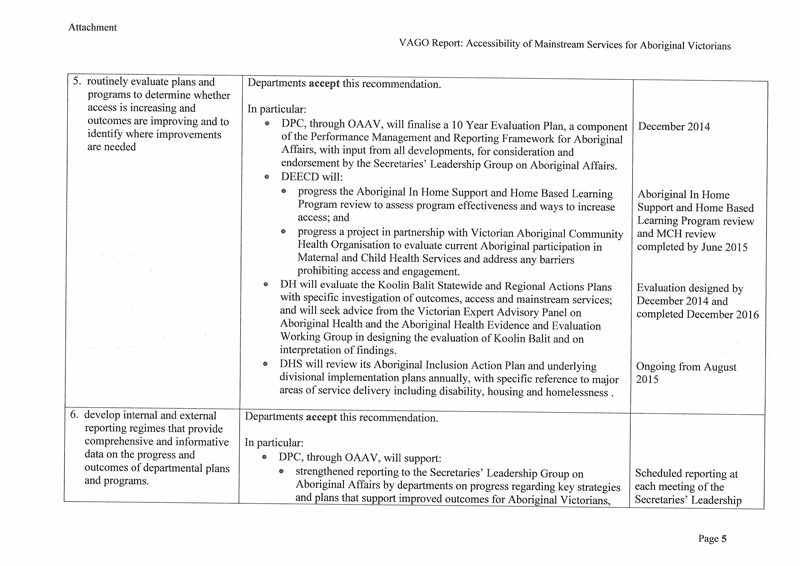

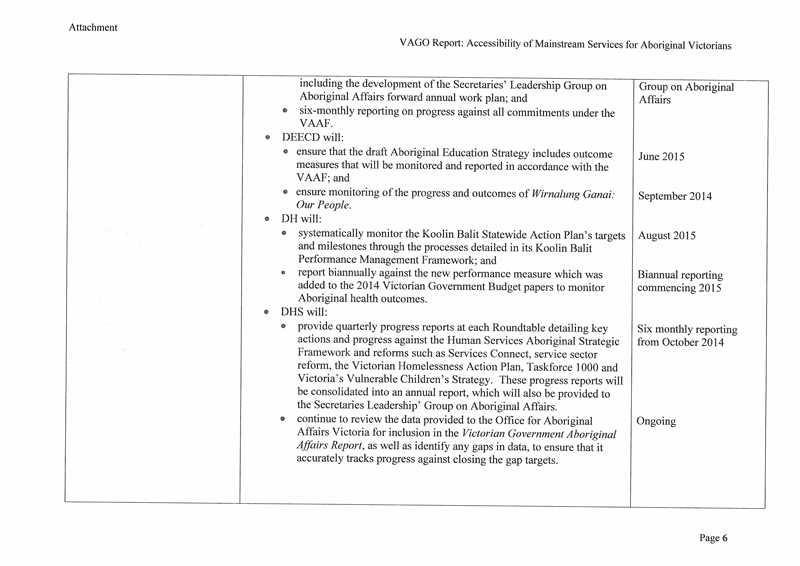

That departments:

- improve data collection and recording processes, including collaborating with other departments, Aboriginal community controlled organisations and other relevant organisations to estimate Aboriginal populations for each service

- as a priority, finalise Aboriginal inclusion action plans and fully apply Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework service access criteria in service delivery plans and programs

- engage a broad range of Aboriginal people in developing, implementing, monitoring and evaluating plans and programs

- identify and pursue opportunities to collaborate, cooperate and share data with government agencies responsible for mainstream service delivery and with service providers

- routinely evaluate plans and programs to determine whether access is increasing and outcomes are improving, and to identify where improvements are needed

- develop internal and external reporting regimes that provide comprehensive and informative data on the progress and outcomes of departmental plans and programs.

That the Department of Premier and Cabinet:

- provides more active leadership and direction so that departmental programs and strategies comply with the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18, and identify and address increased access and improved outcomes

- through the Secretaries' Leadership Group on Aboriginal Affairs, monitors the implementation of departmental plans, evaluates outcomes and monitors the development of investment logic maps that identify the funding requirements over the term of the government's commitment to the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report was provided to the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria and the departments of Education and Early Childhood Development, Health, and Human Services with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix D.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

1.1.1 Victoria's Aboriginal population

Victoria's Aboriginal population is relatively small compared to other parts of Australia. The 2011 census reports that there are around 47 000 Aboriginal people in Victoria — 0.9 per cent of the total population — an increase of around 40 per cent between 2006 and 2011. This growth is attributed to higher birth rates, migration to Victoria and higher rates of people identifying as Aboriginal.

The Aboriginal population is relatively young, with 55 per cent of Aboriginal Victorians under 25 years of age, compared to 32 per cent of the non-Aboriginal population. Victoria's Aboriginal population is distributed between metropolitan Melbourne — 46 per cent — and regional locations — 54 per cent.

1.1.2 Gap between the Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal population

Australia-wide

The Australian Aboriginal population faces considerable disadvantage when compared to the non-Aboriginal population — with gaps in early childhood health and development, higher than average perinatal mortality rates, lower birth weights, and lower participation in maternal and child health services and kindergarten. Aboriginal people report higher levels of psychological distress and have a poorer health status, shorter life expectancy and higher hospitalisation and disability rates. In education, comparatively lower literacy and numeracy outcomes, and higher disengagement rates, contribute to lower rates of Year 12 completion and tertiary education access.

The Victorian experience

Despite some improvements, Aboriginal Victorians are still facing significant disadvantage compared to the rest of the Victorian population. There is a gap in health and educational outcomes and therefore life outcomes between Aboriginal and non‑Aboriginal Victorians. The Council of Australian Governments (COAG) and the Victorian Government have recognised the importance of addressing Aboriginal disadvantage and closing the gap in outcomes.

Data from the 2011 census indicates that the median age of Aboriginal Victorians is 22 years, 15 years younger than the median age of non-Aboriginal Victorians. The data shows higher birth rates and a much shorter life expectancy for Aboriginal people Australia-wide. The Australian Bureau of Statistics is not able to calculate specific Victorian life expectancy rates at present because of the small size of the Victorian Aboriginal population. A large gap in median weekly income is also reported — $390 for Aboriginal and $562 for non-Aboriginal Victorians.

1.1.3 Policy framework

National Indigenous Reform Agreement (Closing the Gap)

In December 2007, COAG created a partnership between all levels of government to address Aboriginal disadvantage and close the gap between the Aboriginal and non‑Aboriginal population. In November 2008, COAG agreed to the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA), which commits all Australian governments to achieving the six Closing the Gap targets:

- close the life-expectancy gap within a generation

- halve the gap in mortality rates for Indigenous children under five within a decade

- ensure access to early childhood education for all Indigenous four-year-olds in remote communities within five years

- halve the gap in reading, writing and numeracy achievements for children within a decade

- halve the gap in Indigenous Year 12 achievement by 2020

- halve the gap in employment outcomes within a decade.

NIRA sets out an integrated strategy, which defines responsibilities, promotes accountability, clarifies funding arrangements, and links to other initiatives contributing to closing the gap. The agreement also identifies strategic areas for policies and sets out policy principles, objectives and performance indicators.

Victorian Government Aboriginal Inclusion Framework

The Victorian Government Aboriginal Inclusion Framework was released in November 2011. It outlines a number of important actions that should shape Aboriginal affairs policy. One of the key actions is to develop departmental action plans to demonstrate how access to and inclusion in mainstream services will be improved. The framework 'is designed to be flexible in its implementation and departments and agencies will be encouraged to develop their own plans, structures and strategies that suit the context within which they operate'. It is intended to provide a tool to assist departments to develop their action plans.

The framework outlines the main barriers Aboriginal Victorians face in accessing services and resources. The main barriers are actual and perceived discrimination by service providers, language and cultural barriers, lack of trust in services and organisations, and lack of awareness of and engagement with local Aboriginal communities.

Victorian Indigenous Affairs Framework

First released in 2006, the Victorian Indigenous Affairs Framework (VIAF) focused on Aboriginal childhood and early development, home environments, economic sustainability, justice, and cultural identity. All government departments were required to prepare Aboriginal Strategic Action Plans addressing key action areas and focusing on interdepartmental collaboration.

VIAF operated between 2006 and 2012. It was revised in 2010 to produce VIAF 2010‑13, which established Victorian-specific objectives and targets consistent with the nationally agreed Closing the Gap targets for 2013, 2018 and 2023. The 2013 targets were not reported against.

Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18

In November 2012, the government released the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18 (VAAF) which builds on the previous VIAF as the primary whole‑of-government framework related to Aboriginal affairs. It identifies six strategic action areas, covering early childhood, education, economic participation, health and wellbeing, safe families and justice outcomes, and strong culture and confident communities. Each strategic area includes sub-objectives with specific improvement targets and expected outcomes.

Many of the indicators under VIAF related to service access and participation and are similar to the VAAF indicators and targets — for example, in action areas such as improving maternal and early childhood health, and developing and improving education outcomes.

VAAF requires all Victorian Government departments to have an Aboriginal inclusion action plan consistent with the Victorian Government Aboriginal Inclusion Framework.

Photograph courtesy of Tobias Titz.

1.1.4 Access to services for Aboriginal people

Many services that Aboriginal people need are delivered by mainstream service providers, including hospitals, maternal and child health services, schools and kindergartens, and community and public housing. The general population is entitled to access these mainstream services.

In addition, Aboriginal community controlled organisations (ACCO) provide a range of services for Aboriginal Victorians, including mainstream services such as maternal and child health, and more targeted services such as the Aboriginal Health Promotion and Chronic Care program (AHPACC), funded by the Department of Health. In many cases, these services exist to facilitate improved access to mainstream services. VAAF outlines that a significant number of Aboriginal people — 40 per cent nationally — rely on ACCO‑delivered services in areas such as health, child and family services, housing and justice.

VAAF emphasises increasing take-up of services as the first step towards improved outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians. It states that 'the challenge for service providers is to encourage or ensure that those targeted by a service actually use it'. In this context, VAAF outlines seven criteria designed to provide better access to services for Aboriginal Victorians and improve outcomes consistent with VAAF priorities. The seven access criteria are listed in Figure 1A.

Figure 1A

Key access criteria for effective service design

|

Criteria |

Outcome |

|---|---|

|

Cultural safety |

Service provider understands client needs, including cultural needs |

|

Affordability |

Clients can afford to use required services |

|

Convenience |

Clients can get to the service easily |

|

Awareness |

Current and potential clients are informed about the availability of the service and its value |

|

Empowerment |

Current and potential clients know which services they are entitled to seek |

|

Availability |

Services that a client needs are accessible |

|

Respect |

Service provider treats the client with respect |

Note: Cultural safety refers to an environment in which people feel safe, that they are respected for who they are and what they need, and that their cultural identity is unchallenged.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office from the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework 2013–18

VAAF recognises that more than any other state or territory, Aboriginal people in Victoria have been directly affected by the Stolen Generation. The Stolen Generation still has a significant impact on the way Aboriginal people feel about mainstream services and the level of trust they have in services that were once used as government instruments for removing Aboriginal children from their families. Also, evidence indicates that historically, Aboriginal Victorians have been excluded or discriminated against when trying to access mainstream services.

To achieve the highest level of service effectiveness, people first need to use the service, which is not an automatic decision. People consider a range of factors in making this choice. The most important challenge for all service providers, when developing a program of services designed to achieve an outcome, is making sure the intended users actually access the services.

In Victoria, mainstream services play a key role in providing health, education and welfare services to Aboriginal people, as the Aboriginal population is quite small and widely dispersed throughout the state.

According to a 2009 report by the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), nearly a quarter of young Aboriginal people and adults had problems accessing services. Long waits, cost and the service not being available when required were the major reported barriers to accessing services. Lack of adequate transport and distance were also commonly reported barriers.

At the 2010 Young Koori Parents Forum, organised by the Victorian Indigenous Youth Advisory Council, young Aboriginal people, particularly young parents, reported limited knowledge of services available to them, which negatively impacts the accessibility of services.

1.1.5 Identified barriers to access

Following our review of documentation — including plans, strategies and evaluation reports — and discussions with audited departments, Aboriginal stakeholders and service providers, we identified the main barriers to accessing mainstream services experienced by Aboriginal people. These include a lack of culturally safe services and a lack of awareness of the services available, racism, shame and fear, complex administrative processes and affordability. Appendix A provides further details on barriers to access and required actions.

1.1.6 Roles and responsibilities

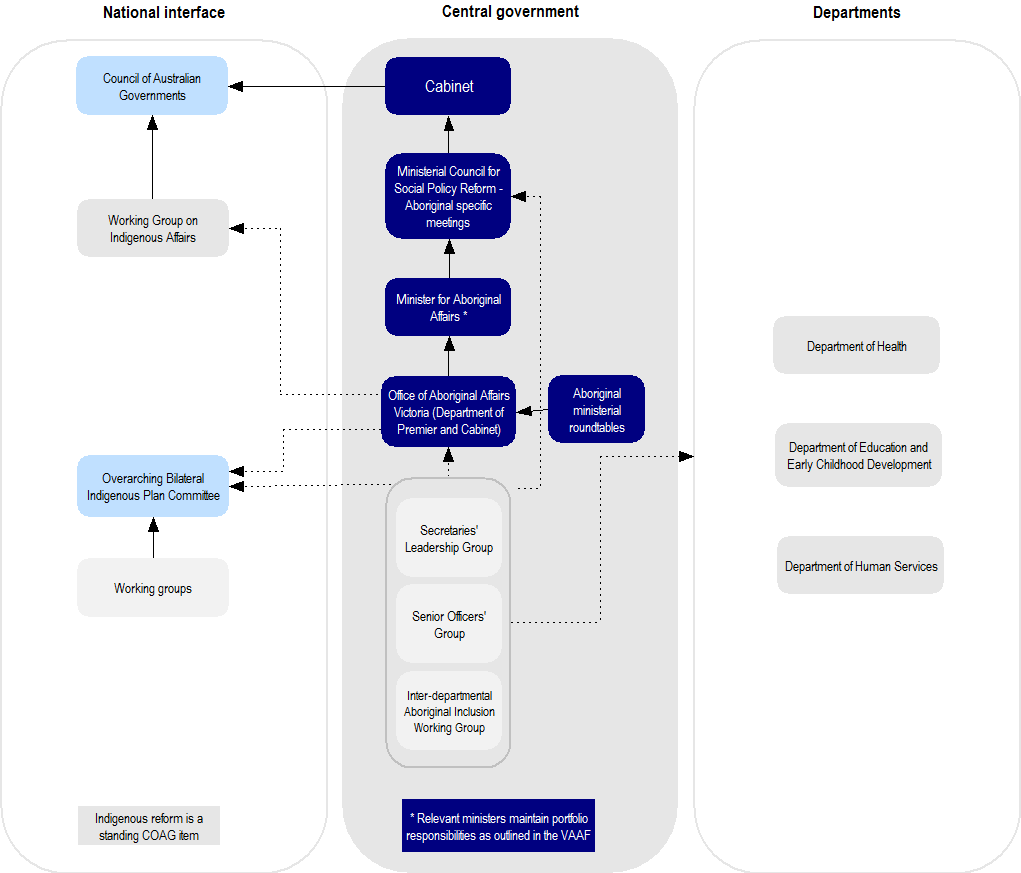

Figure 1B sets out the roles and responsibilities for the development and implementation of Aboriginal affairs policy.

Figure 1B

Roles and responsibilities–Aboriginal affairs policy

Note: Working groups under the Overarching Indigenous Bilateral Plan Committee include the Vulnerable Children's Working Group, the Economic Development Working Group, and the Data Reform Working Group.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office, based on information provided by the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria.

Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria

The Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria (OAAV) was established within the former Department of Planning and Community Development in December 2012 to combine Aboriginal Affairs Victoria with the Aboriginal Affairs Taskforce. In July 2013 OAAV was transferred to the Department of Premier and Cabinet. Consistent with its business plan, OAAV takes a coordinated end-to-end approach to deliver the Victorian Government's agenda for Aboriginal policy reform, community strengthening and engagement, and cultural heritage management and protection. OAAV works with Victorian Aboriginal communities and other partners to lead the whole-of-government Aboriginal affairs reform agenda to improve the lives of Aboriginal Victorians. It is also responsible for the effective implementation of the Aboriginal Heritage Act 2006 and the Aboriginal Lands Act 1970.

Secretaries' Leadership Group on Aboriginal Affairs

The Secretary of the Department of Premier and Cabinet chairs the Secretaries' Leadership Group on Aboriginal Affairs (SLG), which has a membership comprising the secretaries of all departments. SLG has a range of responsibilities, including overseeing the implementation of VAAF and driving the development and implementation of departmental Aboriginal inclusion action plans to ensure services are accessible and inclusive for Aboriginal Victorians.

Senior Officers Group

The Executive Director of OAAV chairs a Senior Officers' Group on Aboriginal Affairs with representatives from across Victorian Government departments. Its role is to provide a forum for interdepartmental collaboration and coordination.

Government departments

Departments develop policies specific to their area and coordinate service provision for Aboriginal Victorians. Each department should have an Aboriginal inclusion action plan that guides it in developing policies and services that are culturally appropriate for Aboriginal people. In terms of departmental responsibilities:

- The Department of Health has three main focus areas, health, mental health and aged care. The department works primarily in a funding and policy capacity, funding a variety of mainstream and targeted services.

- DEECD funds kindergarten programs, the Victorian Maternal and Child Health Service, parenting services, and school and higher education.

- The Department of Human Services either directly delivers or funds community organisations to deliver child protection, out-of-home care and family services, youth justice services, disability services, housing and homelessness services, and concessions.

Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations

ACCOs are not-for-profit organisations that provide services to Aboriginal people and are administered by the community they serve. They often run programs funded by government departments involving partnerships with mainstream service providers. Generally, their focus is on facilitating access to, and improving cultural safety of, services for Aboriginal people. Their establishment and management is community driven and largely regulated through state and Commonwealth legislation. Aboriginal community controlled health organisations are well established types of ACCOs.

1.2 Previous VAGO audits

Coordinating Services and Initiatives for Aboriginal People, June 2008

The audit examined how well services and initiatives for Aboriginal people are planned and coordinated across the Victorian public sector and specifically focused on the governance and accountability arrangements in place to facilitate and monitor the progress of VIAF.

The audit examined interdepartmental and intradepartmental arrangements, and found that lack of coordinated program design was a key area for attention. Overall, the findings indicated that the respective roles and responsibilities of the agencies involved were unclear and cross-departmental collaboration was not evident. At a department level, the audit found that the departments' action plans were incomplete, or not clear in terms of interdepartmental collaboration.

The audit also identified a lack of joint datasets for departments to monitor goal achievement, and the need for a performance monitoring framework to monitor progress.

Indigenous Education Strategies for Government Schools, June 2011

The audit examined the implementation and delivery of the Wannik education strategy. It found that the strategy had a solid planning base but the rigour was not sustained throughout the rollout of the program, resulting in poor implementation. It also found that there were no comprehensive plans covering implementation milestones and time lines, stakeholder engagement and communications, and risk management. There was insufficient information available and no reporting mechanisms that provided a picture of the overall status of the Wannik strategy.

The audit reported that DEECD was unable to demonstrate that it was effectively managing the range of risks to the strategy's success. Rather than project-managing the strategy, DEECD used a business-as-usual model with a limited accountability system.

Access to Education for Rural Students, April 2014

This audit assessed the effectiveness of DEECD's activities to ensure that Victorians in rural areas have access to a high-quality education and that outcomes for these students are maximised.

The audit concluded that DEECD has not provided access to high-quality education for all students, and while DEECD undertakes many activities that assist rural educators and students, these have not resulted in significantly improved performance. The report, however, did acknowledge that DEECD's Smarter Schools National Partnerships program for people in low socio-economic areas had improved oral language skills among Indigenous students and the capacity of teachers to work with disadvantaged students.

1.3 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess the accessibility of mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians.

The following criteria address the audit objective:

- departments have a sound understanding of the service needs of Aboriginal people

- departments develop and implement effective plans, programs and strategies to facilitate access to services for Aboriginal Victorians and address identified needs

- departments can demonstrate how improved service access has contributed, and is expected to contribute, to improved outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians

- there are effective monitoring, reporting and evaluation frameworks in place, underpinned by reliable data on service access,to demonstrate the achievement of intended outcomes.

This audit examined access to mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians, including targeted programs and strategies designed to support access to these services, which are mainly services provided or funded by departments.

The audit focused on whole-of-government and departmental policies, programs and strategies, as well as outcomes, covering early childhood, health and human services.

The following departments were part of the audit:

- Department of Premier and Cabinet — Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria

- DEECD

- Department of Health

- Department of Human Services.

The audit examined specific services within early childhood, health, and human services — excluding child protection and youth justice. Appendix B sets out the mainstream services and key related strategies and programs provided by departments in this audit.

1.4 Audit method and cost

The audit was conducted in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Audit evidence was gathered through:

- meetings with each of the four audited departments, including regional staff

- meetings with service providers and other stakeholders, including in regional areas

- review of government frameworks and policy for Aboriginal affairs

- review of departmental plans, programs and strategies, including examination of evaluations, reviews and progress reports.

Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of this audit was $335 000.

1.5 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 discusses whether departments have a sound understanding of the needs of Aboriginal Victorians

- Part 3 discusses departmental plans, programs and strategies

- Part 4 discusses access, outcomes and governance.

2 Understanding the needs of Aboriginal Victorians

At a glance

Background

Victorian Government departments need a sound understanding of the service needs of Aboriginal Victorians to be able to design and deliver services which are accessible.

Conclusion

Audited agencies have a reasonable understanding of the service needs of Aboriginal Victorians. However, this is constrained by a lack of broad consultation and complete and reliable data.

Findings

- Audited departments have established both structured and informal processes for consulting and engaging with stakeholders and representatives of Aboriginal organisations. However, existing processes are limited in breadth.

- There are challenges for the audited departments in obtaining complete and reliable data to identify needs, to develop plans, and to evaluate programs and report outcomes, particularly data relating to population levels.

- While there is evidence of data sharing across departments, this is limited and — without improving data collection methods and information-sharing practices — departments cannot be assured they are meeting the needs of Aboriginal people.

Recommendation

That departments improve data collection and recording processes, including collaborating with other departments, Aboriginal community controlled organisations and other relevant organisations to estimate Aboriginal populations for each service.

2.1 Introduction

Departments need a sound understanding of the service needs of Aboriginal Victorians if they are to design and deliver services that are accessible and achieve improved outcomes. This Part assesses whether departments have a sound understanding of the needs of Aboriginal Victorians that can inform the development of robust plans for service delivery.

2.2 Conclusion

Audited departments have a reasonable understanding of the service needs of Aboriginal Victorians. However, this is constrained by a lack of broad consultation and of complete and reliable data. Although there are challenges for the departments in obtaining data to identify needs — including data on population levels — data collection could be improved.

The Department of Health (DH) has an extensive program of evaluation that assists it to understand Aboriginal service needs, but neither the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) nor the Department of Human Services (DHS) were able to demonstrate similarly comprehensive evaluation programs to assist them in understanding the needs of Aboriginal Victorians. DHS and DEECD provided limited evidence of extensive consultation. DH provided evidence of extensive consultation at a state and local level with both mainstream and Aboriginal organisations. However, existing processes are limited in breadth. With respect to consultation:

- Some regional stakeholders indicated that a lack of broad consultation limits community representation and is time-consuming for stakeholders on multiple committees.

- Many organisations, including Aboriginal community controlled organisations (ACCO) that provide feedback and advice to departments are directly funded by those departments, which may diminish their capacity to provide open and constructive feedback. Greater use of community consultation, including with service users, would strengthen the consultation process and provide departments with views unencumbered by funding relationships.

2.3 Understanding Aboriginal service needs

2.3.1 Consultation and engagement

Under the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework (VAAF), consultation and engagement with Aboriginal people is fundamental to the achievement of government objectives for Closing the Gap, and can only be achieved through 'genuine engagement' with both the community and Aboriginal organisations and peak bodies. Under the National Indigenous Reform Agreement (NIRA) to close the gap, Victoria committed to specific service delivery principles for programs and services for Indigenous Australians, including the Indigenous engagement principle:

'Engagement with Indigenous men, women and children, and communities should be central to the design and delivery of programs and services.'

Both VAAF and NIRA make clear the importance of engaging community members as well as ACCOs and mainstream service providers in all aspects of service delivery.

Consultation and engagement is therefore vital to ensure that services are accessible, ensure that planned actions take into account the views and experience of Aboriginal people and the community, and evaluate service effectiveness. There are a number of ways in which government departments consult and engage with Aboriginal organisations and people. These are discussed in this section.

Photograph courtesy of Tobias Titz.

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

The main consultation process DEECD uses to inform its approach to Aboriginal inclusion involves quarterly meetings with the peak Aboriginal education body in Victoria — the Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Incorporated (VAEAI). DEECD provides funding to VAEAI, which has a committee of management that is made up of the leaders of 32 Local Aboriginal Education Consultative Groups located across the state. Records of meetings are not comprehensive but indicate that these meetings are not used solely for consultation but also to update VAEAI members on DEECD initiatives.

DEECD has a service agreement with the Victorian Aboriginal Community Services Association Limited, with which it has quarterly meetings. DEECD also provided evidence of consultation with the Victorian Aboriginal Child Care Agency and the Victorian Aboriginal Community Controlled Health Organisation.

Evidence provided by DEECD relating to these relationships does not indicate that consultation is robust, nor is it clear if DEECD uses this consultation to assist it in understanding the needs of Aboriginal people. Also, there is insufficient evidence of rigorous engagement with the local community.

However, DEECD does have a reasonable understanding of the needs of Aboriginal people. It has been aware of problems with access to services for some time, evidenced by issues raised in past reports including the State of Victoria's Children 2012: Early Childhood Report which discusses gaps in development between Aboriginal children and the rest of the population.

A departmental review of the maternal and child health (MCH) service in 2013 raised a number of issues with this service, including a lack of strategies to increase the participation of Aboriginal children and families. DEECD has known of issues with the delivery of this service since a 2006 review undertaken when MCH was part of DHS. The recommendations of these reviews are quite similar. For example, both reviews recommended:

- use of outcome, rather than input, measures to monitor and evaluate system performance

- improvements to workforce management models and development of strategies to support the future service delivery model

- implementing a formal professional development program that supports the workforce strategy.

The review findings indicate there has been little change over time in ensuring the MCH service is able to support vulnerable cohorts such as Aboriginal families on a statewide basis. This highlights prolonged inaction by the department in addressing needs and developing and finalising plans and strategies.

Department of Health

DH has a better understanding of the needs of Aboriginal people, obtained primarily through a network of Regional Aboriginal Health Committees that are made up mainly of Aboriginal organisations and local mainstream service providers. DH has developed a range of programs and initiatives, some going back several decades, that aim to specifically address the needs of Aboriginal Victorians — such as the Victorian Patient Transport Assistance Scheme, Koori Maternity Services (KMS) and programs that assist staff with developing culturally safe environments, including Improving Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Patients and Aboriginal Hospital Liaison Officers.

A key initiative of DH is the Koolin Balit: Victorian Government strategic directions for Aboriginal health 2012–2022 policy document, which provides the overall strategic directions for Aboriginal health over 10 years.

DH has several ongoing consultation structures in place, including the Victorian Advisory Council on Koorie Health, the Victorian Committee for Aboriginal Aged Care and Disability, and the Aboriginal Tobacco Control Advisory Group. DH provided evidence that the Koolin Balit planning process began with consultation with Aboriginal community-controlled organisations and mainstream community organisations in each region, using both existing consultation structures and a more targeted approach.

Gippsland Lakes Community Health Centre. Photograph courtesy of Tobias Titz.

DH has conducted a number of service delivery reviews, some of which provided valuable information to assist it in understanding Aboriginal needs. These include:

- The Review of KMS 2012 found that barriers to maternity care access include lack of transport, shame, lack of understanding of the importance of maternal health, complex needs, concerns about child protection officers and not trusting the KMS worker.

- The Improving Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Patients (ICAP) Quality of Care Review 2011 found that health practitioners need skills and knowledge development to provide care that meets the cultural needs of Aboriginal people.

- The ICAP and Koori Mental Health Liaison Officers Developmental Review 2011 identified key enablers that could improve models of care by meeting the needs of Aboriginal patients.

- The Aboriginal Health Promotion and Chronic Care Program (AHPACC) Review 2010 found that the program may have contributed to a 69 per cent increase in access to medical services between 2005–06 and 2009–10.

- DH used the results of these and other reviews when developing Koolin Balit, including the shift in focus away from shorter 'one-off' projects to more long-term work. DH also changed the structure of its ICAP program following the ICAP and Koori Mental Health Liaison Officer (KMHLO) Developmental Review in 2011 and used the 2010 evaluation of the AHPACC program to revise service delivery targets and models, improve networking and shift resourcing to capacity-building activities.

These reviews improved DH's understanding of the needs of Aboriginal people. In particular, DH applied the results of its ICAP and KMHLO Developmental Review to redesign the program, and recently completed a series of evaluations of its previous overarching Aboriginal health strategy, the Closing the Gap in Aboriginal Health Outcomes Initiative, which also recommended a shift away from one-off projects to more sustained initiatives.

Department of Human Services

In December 2012, DHS restructured its operations hierarchy to increase its focus on service needs at the local level. The aim of this was to improve service coordination and provide better outcomes through early intervention and increasing social and economic participation. Human Services stakeholders indicated the importance of understanding localised differences in needs. The restructure may assist in developing a better understanding of this.

DHS has processes in place for structured consultation and informal engagement with stakeholders and representatives of Aboriginal groups. These include the Community Conversations and Human Services Aboriginal Roundtable, and engagement processes with six Aboriginal Signatory Organisations. Formal meetings are held at scheduled times throughout the year. In March 2013, the chief executive officers of these organisations and the Secretary of DHS signed the DHS protocol, which formalises the engagement process.

Despite these formal processes, evidence does not indicate that consultation is rigorous and it is unclear how it is used to inform an understanding of needs. However, DHS is in the process of implementing broader consultation processes. These include Community Conversations held in conjunction with the Human Services Aboriginal Roundtable, and DHS's relationship with the First Peoples Disability Network Australia and the Victorian Aboriginal Disability Network, which represent Aboriginal people with a disability and their carers.

DHS advised that its four divisions are working with local communities to establish Aboriginal advisory structures to support planning and implementation of Aboriginal inclusion action plans. These consultation processes are recent initiatives, so it is too early to assess their effectiveness.

DHS has undertaken program reviews and developed guidance material and discussion papers in relation to its disability, housing and homelessness services. Our review of these documents highlighted challenges for the department in understanding and addressing the service needs of Aboriginal Victorians in these areas.

Aboriginal Homelessness in Victoria

A discussion paper on Aboriginal homelessness prepared by DHS in 2013 indicated that based on Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data the number of Aboriginal people experiencing homelessness had increased by 30 per cent between 2006 and 2011 — from 639 people to 832 people. The number of all homeless people in Victoria also increased by 30 per cent over the same period.

The paper identified the structural barriers to access experienced by Aboriginal Victorians, including financial pressures and lack of culturally responsive services, and weaknesses in the reliability of data on homelessness. The paper recommended that:

- agencies should build the evidence-base for Aboriginal homelessness and separate out data to capture Aboriginal service usage to inform future distribution of funding addressing community needs and disadvantage

- Aboriginal people should be engaged in the development, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programs.

This paper provides an informative insight into how DHS can identify and understand the housing needs of Aboriginal Victorians and address homelessness issues.

Aboriginal Victorians with a disability

In March 2011, DHS released a guide for promoting access and inclusion of Aboriginal Victorians with a disability entitled Enabling choice for Aboriginal people living with a disability.

The guide acknowledged that the disability needs of Aboriginal Victorians are complex and may require access to a range of services and supports, as well as increased coordination between services. It also identified that the factors contributing to Aboriginal use, or non-use, of disability support services are complex, ranging across fear, racism, stereotyping, misinformation, shame, attitudes towards Aboriginal clients among service providers, and the interpretation of how disability is defined within the Aboriginal community.

This guidance material was based on consultation with ACCOs, community elders and local community disability service providers. It provides evidence of DHS's efforts to understand the needs of Aboriginal Victorians with a disability and the provision of disability services.

2.3.2 Complete and reliable data

Complete and reliable data is important to:

- assist with the identification of Aboriginal service needs, leading to the planning and development of evidence-based departmental programs

- measure the success of a program, including whether service access has improved, and expected outcomes have been achieved.

There are challenges for the audited departments in obtaining complete and reliable data to identify needs, to develop plans and to evaluate programs and report outcomes — particularly data relating to population levels. For example, ABS cannot calculate and report Aboriginal life expectancy in Victoria, because the number of deaths reported as Aboriginal is too low and the population is too small. This means that data about a key outcome is not presently available, and it is not expected to be until after the 2016 census.

Some programs that encourage identification, such as those used in public hospitals, assist in developing a better understanding of population levels in local areas. However, in order to understand the service needs of the Aboriginal population, departments should further develop strategies to increase identification, and work with local service providers and ACCOs to assist in understanding population levels in local areas. This is particularly pertinent when estimating Aboriginal service use in regional areas. For example, 2006 ABS data put the Aboriginal population in the Shepparton area at 3.2 per cent of the overall population. Based on its number of registered clients, Rumbalara Aboriginal Cooperative estimates the population to be 7.4 per cent. Greater Shepparton City Council has estimated that the population may be as high as 10 per cent.

Departments are aware of barriers to access. However, high annual population growth rates, particularly in regional areas, mean it is difficult for departments relying on census data to be confident that all of the eligible people who require a service are able to access it. This is why estimated service populations — that is, a population estimate based on demand for and use of services in a particular area — can be more useful.

Both DH and DHS have put in place data collection initiatives to improve completeness and reliability of datasets, particularly relating to service accessibility for Aboriginal Victorians. For example, DH is establishing more accurate baseline data on Aboriginal populations in hospitals, while DHS has established the Centre for Human Services Research and Evaluation, which is focusing on developing its evidence-base. DEECD is in the process of improving data collection in the MCH service.

While there is evidence of data sharing across departments, this is limited, and without improving data collection methods and information-sharing practices, departments cannot be assured they are meeting the needs of Aboriginal people.

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

Past reports at DEECD have highlighted data quality issues affecting the evaluation of service delivery programs. For example, the 2006 MCH service review — undertaken by DHS — found that data quality issues make evidence-based research, and consequently measuring outcomes, difficult. The September 2013 VAGO report Performance Reporting Systems in Education found similar problems with data quality. This report noted it is difficult to monitor who is not using the MCH service or the reasons why this is occurring.

These reports indicate that DEECD has for a number of years known about data quality issues affecting evaluation of access to services. DEECD provided evidence that it is in the process of establishing a central data system for the MCH service to replace manual data collection processes in response to VAGO's findings.

Department of Health

DH does not set service access targets for Aboriginal people as part of its approach to ensuring mainstream services are accessible. While this makes it difficult for DH to determine if mainstream services are becoming more accessible, problems with data mean that it would be difficult to measure access without considerable work to quantify the Aboriginal population.

Since 1993, mandatory identification of Aboriginal people in the Victorian Admitted Episodes Dataset has enabled the establishment of baseline data. DH is endeavouring to establish more accurate baseline data by encouraging identification of Aboriginal users of DH services — including hospital and dental, home and community care, Victorian eye care and community health services, and as part of AHPACC. This initiative is significant because it provides DH with data on actual service use, which is more useful than relying on ABS census data which estimates the temporary population of a particular area.

The ICAP program supports identification of Aboriginal patients in hospitals by aiming to create a more welcoming environment. Evidence indicates that ICAP has:

- improved cultural safety and support in public hospitals

- increased numbers of referrals

- decreased fail-to-attend rates at hospitals.

The establishment of baseline data and the ICAP program are both positive initiatives for DH.

Department of Human Services

DHS provided data relating to Aboriginal people for specific service areas including detailed data relating to provision of public housing, overcrowding and total numbers of new households assisted. DHS estimated the proportion of the Aboriginal population in Victoria that was homeless in 2013 to be 3.7 per cent. However, the reliability of this data is unclear. DHS advised that it is working to improve data reliability, particularly regarding accessibility of services for Aboriginal people.

DHS also advised that it has completed work to incorporate specific service data relating to Aboriginal Victorians into DHS board and other performance reporting, including housing assistance waiting times, access and eviction data. DHS also informed us that work is underway to address the reliability of service data for disability and homelessness services. For example:

- DHS is developing a Client Engagement Framework — consistent with the Victorian Government Aboriginal Inclusion framework — to improve client engagement across settings and promote culturally responsive service delivery, including a Practice Guide to support the identification of Aboriginal clients.

- Work is being undertaken to forecast service demand for homelessness services as part of the Victorian Homelessness Action Plan 2011–15, which includes a specific focus on Indigenous clients.

We have not seen evidence of this work.

DHS has established the Centre for Human Services Research and Evaluation, which will lead the development of DHS's evidence-base through research and evaluation activities, and advise and assist DHS in evaluating program areas.

Recommendation

- That departments improve data collection and recording processes, including collaborating with other departments, Aboriginal community controlled organisations and other relevant organisations to estimate Aboriginal populations for each service.

3 Plans, programs and strategies

At a glance

Background

Plans, programs and strategies should be consistent with the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework (VAAF) and demonstrate how each department will improve access and inclusion for Aboriginal people across all service areas.

Conclusion

Plans, programs and strategies do not yet adequately reflect the service access criteria of the VAAF.

Findings

- All departmental secretaries have agreed to finalise Aboriginal inclusion action plans by the end of August 2014, but significant work remains to ensure that plans identify and address barriers to access.

- There is a lack of collaboration and coordination between the departments and service providers, as well as at service delivery level between local providers.

- While the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria has released guidelines to develop Aboriginal inclusion action plans, departments are responsible for developing and implementing their own plans. There is little oversight of plans which means they are of varying quality.

Recommendations

That departments:

- as a priority, finalise Aboriginal inclusion action plans and fully apply VAAF service access criteria in service delivery plans and programs

- engage a broad range of Aboriginal people in developing, implementing, monitoring and evaluating plans and programs

- identify and pursue opportunities to collaborate, cooperate and share data with government agencies responsible for mainstream service delivery and with service providers.

3.1 Introduction

Plans, programs and strategies should be consistent with the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework (VAAF) and demonstrate how each department will improve access and inclusion for Aboriginal people across all service areas.

The Victorian Government Aboriginal Inclusion Framework 2011 (VGAIF) requires all government departments to prepare Aboriginal inclusion action plans in accordance with the Aboriginal Inclusion Action Plan Guidelines issued by the Office of Aboriginal Affairs Victoria (OAAV) in 2011. Under VGAIF, these plans must demonstrate how each department will improve access and inclusion for Aboriginal people across all service areas.

VGAIF is flexible about the form these plans may take and plans do not consistently demonstrate how inclusion and access will be improved.

Departments are responsible for developing, releasing and implementing their own plans. The framework is intended to allow departments to tailor their plans and programs to suit their particular role and approach to facilitating access and delivering the services they provide or fund.

This Part assesses audited departments' plans, strategies and programs for enhancing access to and delivery of mainstream services for Aboriginal Victorians.

3.2 Conclusion

Departments have developed a range of plans, strategies and programs to assist in improving access. Most of these have been in place for five to 10 years, and in the case of the Department of Health (DH), some for over 20 years. However, despite the development of VAAF in 2012, departments have neither reviewed, nor updated, nor significantly changed their plans to reflect VAAF's shift in focus to improving service access. Plans were due to be finalised by the end of 2013 but were not completed by that date. All departmental secretaries have now agreed to finalise outstanding Aboriginal inclusion action plans by the end of August 2014.

There is little oversight of plans which means they are of varying quality. OAAV advised that the Secretaries' Leadership Group on Aboriginal Affairs (SLG) has recently agreed to a terms of reference for the creation of a new interdepartmental Aboriginal inclusion working group to provide for regular departmental engagement and oversight of the plans and associated processes.

While departments have addressed some access barriers through their plans, programs and strategies, barriers have not been uniformly addressed and it will be difficult to achieve better outcomes without considering all the issues that impact service access.

3.3 Adequacy of plans and strategies for service delivery

We examined the progress of audited departments in preparing Aboriginal inclusion action plans under the VGAIF and VAAF, as well as past Aboriginal service delivery plans and strategies to assess whether they were consistent with better practice criteria established in government policy framework documents.

3.3.1 Quality of plans and strategies

The quality of the sample of plans and strategies for delivery of services to Aboriginal Victorians was poor overall and did not adequately address many of the better practice criteria. There is significant scope for departments to improve the comprehensiveness of these documents.

Aboriginal inclusion action plans should have clearly stated objectives, expected outcomes with clear targets, performance measures that are capable of being measured and time lines. Plans will need to incorporate accountabilities through roles and responsibilities, provide for effective monitoring and evaluation, and have clear lines of reporting, including internally, to OAAV and the SLG, and through the annual report.

3.3.2 Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

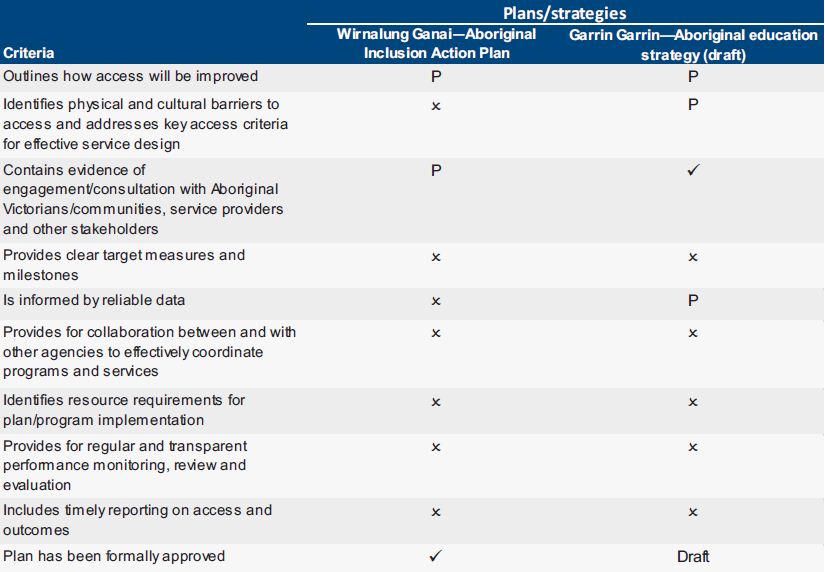

We assessed two of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development's (DEECD) key strategic documents for the provision of Aboriginal education services against government policy framework objectives and better practice criteria. Figure 3A summarises the results of our assessment.

Figure 3A

DEECD–Assessment of plans and strategies against key criteria

Note: ✔ = Met, P = Partially met and ✘ = Not met.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on government policy framework documents.

Wirnalung Ganai — Aboriginal Inclusion Action Plan

DEECD has a whole-of-department action inclusion plan, Wirnalung Ganai: Our People–Aboriginal Inclusion Action Plan 2012–14, which was launched in 2011. It aims to make DEECD a more culturally responsive workplace, both structurally and organisationally, and to increase its employment of Aboriginal people in order to facilitate a more culturally appropriate approach to departmental service delivery.

Overall, this plan does not meet better practice criteria for a soundly based action plan. It does not reflect VAAF access criteria, detailing only that access will be improved by increasing Aboriginal employment and making the workplace more culturally safe.

Photograph courtesy of Tobias Titz.

Garrin Garrin — A strategy to improve learning and development outcomes for Aboriginal Victorians (draft)

DEECD is currently developing an Aboriginal education strategy, which when released will replace its previous Aboriginal education strategies, Wannik and Wurreker, and become DEECD's main strategy for Aboriginal inclusion.

This draft strategy revises the early years approach into a lifespan approach to Aboriginal education, and it aims to 'improve the opportunities for all learners without exception'. The draft strategy indicates that 'being available and being accessible are two different things', emphasising the difficulties Aboriginal people may face in accessing services, and highlighting the need for the department to continue to work to improve service access, inclusiveness and usefulness.

Although barriers are mentioned, they are not explicitly identified. DEECD consulted with community members across Victoria as part of the development of the strategy.

Specifically, the draft strategy discusses the difference between a service being available and it being accessible, and references VAAF accessibility criteria. However, there are no clear target measures or milestones mentioned outside of those under VAAF.

3.3.3 Department of Health

DH has a range of strategic documents and plans for enabling Aboriginal inclusion, including the Department of Health Aboriginal Inclusion Framework 2013, Koolin Balit: Victorian Government strategic directions for Aboriginal health 2012–2022 and various regional closing the gap plans.

Photograph courtesy of Tobias Titz.

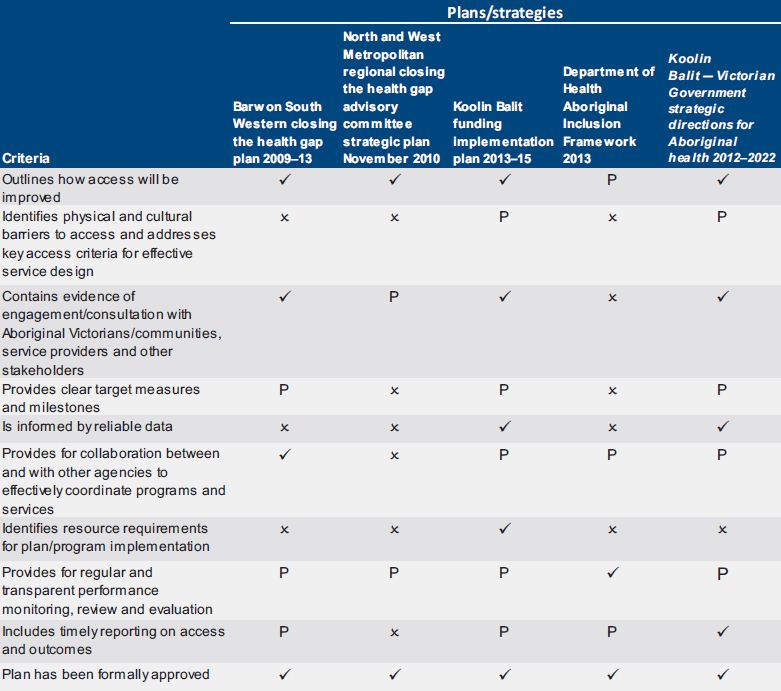

We assessed a number of DH's strategy documents and plans against government policy framework objectives and better practice criteria. Figure 3B summarises the results of our assessment.

Figure 3B

DH–Assessment of plans and strategies against key criteria

Note: ✔ = Met, P = Partially met and ✘ = Not met.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office based on government policy framework documents.

Regional closing the gap plans

We assessed two regional plans — Barwon South Western closing the health gap plan 2009–13 and North and West Metropolitan regional closing the health gap advisory committee strategic plan November 2010. These plans were developed prior to the introduction of VAAF, and therefore do not reflect VAAF access criteria.

Both plans were formally adopted, and they adequately describe how access will be improved. However, each plan was deficient with respect to other criteria — neither adequately identifies or addresses barriers to access, and they do not include clear target measures and milestones, resource needs or requirements for reporting on access and outcomes.

DH advised that obtaining data at the local level relating to incidence of disease or, for example, perinatal mortality is difficult because of the very small sample sizes. In many cases it is difficult to provide de-identified data.

Plans/strategies under the Victorian Aboriginal Affairs Framework

The DH Aboriginal Inclusion Framework 2013 sets out DH's key strategies and plans to promote access and inclusion. It emphasises local planning as imperative to meeting needs, including the need for targeted intervention for Aboriginal people. Under this framework, DH has developed its plan Koolin Balit — Victorian Government strategic directions for Aboriginal health 2012–2022.

While these documents do not directly reference VAAF, DH believes that VAAF service access criteria are implicit in them, and that Koolin Balit was prepared with frequent interaction between DH and OAAV relating to themes and direction, although it was published six months prior to VAAF. However, VAAF access criteria are quite specific, and without direct reference to these criteria it is difficult to see how they are being applied to service delivery.

DH has recently completed the Koolin Balit funding implementation plan 2013–15, which contains an overarching plan for funding Koolin Balit initiatives, including the Koolin Balit regional action plans. The funding plan is linked to VAAF and Koolin Balit: Victorian Government strategic directions for Aboriginal health 2012–2022. We have been given extensive documentation indicating significant consultation and planning has been undertaken in regional areas relating to the development of this framework and the individual regional plans.

As well as these plans, individual hospitals and health services have adapted and developed a number of their own initiatives to improve access to services. These include local advisory committees, and cultural awareness training that is targeted to specific local cultural needs, as is the case at Goulburn Valley Health, which has a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the Rumbalara Aboriginal Cooperative. Feedback from Aboriginal stakeholders indicated that this has been a positive approach.

Mallee District Aboriginal Services has developed a number of MOUs, including with Mildura Base Hospital. These MOUs provide an opportunity for mainstream organisations to strengthen their cultural awareness and relationships with the local community, and are viewed as a positive development by both organisations.

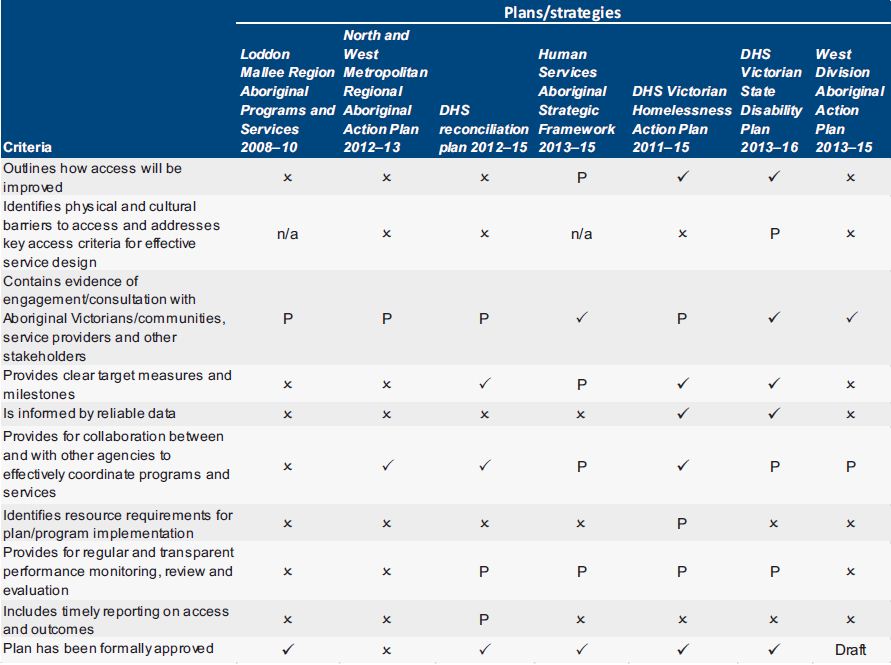

3.3.4 Department of Human Services

Since around 2002, the Department of Human Services (DHS) has developed a range of action strategies and plans to enable Aboriginal inclusion. These have evolved over time — with the introduction of the Victorian Indigenous Affairs Framework in 2006, the Aboriginal Inclusion Framework in 2011 and more recently VAAF in 2012.