Agricultural Food Safety

Overview

This audit found that agricultural food safety—encompassing farming, transporting, handling and processing raw agricultural products—is being effectively managed. This is supported by the Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Dairy Food Safety Victoria (DFSV) and PrimeSafe actively monitoring and enforcing compliance with regulations and food safety standards, and by the Department of Health (DOH) as the lead agency across the whole food safety system.

As with any aspect of public sector activity, there are areas for improvement. DPI, DFSV and PrimeSafe do not have clear performance measures or benchmarks defining what they expect effective performance to achieve. This limits their ability to attribute their regulatory work to positive food safety outcomes in Victoria. There are also opportunities for DPI to strengthen its risk-based approach to compliance monitoring and for DOH to improve its planning for incident response.

The agencies are members of the Committee of Food Regulators, which provides an effective coordinating role for the food safety system. However, the system’s effectiveness in driving improved food safety outcomes is weakened by a narrowly focused draft strategic plan, unclear accountability for achieving the plan, and an absence of information about the performance of the food safety system.

Agricultural Food Safety: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER March 2012

PP No 110, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Agricultural Food Safety.

Yours faithfully

![]()

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

14 March 2012

Audit summary

Agricultural food safety involves the primary production and processing of raw agricultural products. This encompasses activities on farms, during transportation, and at the facilities involved in processing and handling raw products.

Food safety risks can arise from poor management practices at any stage of the supply chain, such as poor controls over the use of chemicals and veterinary medicines and problems with facilities, hygiene, temperature control and handling practices of food items.

Australia has a national framework for food regulation, which includes food safety. The framework is established through an intergovernmental agreement between the Australian, state and territory governments and delivered through uniform national food standards.

In Victoria, a mix of regulation, education, advice and research are used to manage food safety risks and implement the national Food Standards Code. The Department of Health (DOH), Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Dairy Food Safety Victoria (DFSV) and PrimeSafe all have important responsibilities for supporting Victoria’s agricultural food safety system.

Conclusions

Agricultural food safety is being effectively managed, supported by the three regulators—DPI, DFSV and PrimeSafe—actively monitoring and enforcing compliance with regulations and food safety standards. Audit examinations show they apply their policies and procedures consistently and have sound controls in place for managing the quality of this work.

As with any area of public sector activity, there are areas for improvement in regulatory approaches. Importantly, there are opportunities for regulators to be able to demonstrate more clearly the effectiveness of regulatory activities.

Across the three regulators, assurance about the effectiveness and impact of their activities is incomplete because they do not have clear performance measures or benchmarks defining what they expect effective performance to achieve. This limits their ability to attribute their regulatory work to positive food safety outcomes in Victoria. This is also the case for the performance of the food safety system as a whole.

Findings

Managing compliance with food safety regulation

To regulate effectively, the agencies regulating agricultural food safety need to have clear food safety rules and requirements. They also need to efficiently and effectively administer and enforce them. This involves supporting businesses to understand and apply the requirements, monitoring how well businesses comply with them and applying sanctions to serious compliance breaches.

Generally, the three agencies are managing compliance well. There are clear rules and requirements for agricultural production and processing businesses to manage food safety.

DFSV and PrimeSafe have sound, risk-based processes for monitoring compliance, managing non-compliance with food safety requirements and using their enforcement powers. Each is generally consistent in applying them. These are effective approaches, given generally high compliance rates, low incidence of repeat offenders and rare need to prosecute. While DPI has risk-based processes for monitoring compliance and managing non‑compliance and enforcement, its approach to monitoring chemical use compliance needs to be strengthened.

DOH has primary responsibility for food safety incident response, whether it is an incident relating to the agricultural food safety stream or the manufacturing, retail and food service stream. The audit examination of recent incidents showed DOH communicated clearly and frequently with other agencies, sought advice and information and used its enforcement powers as a last resort. Recent national reviews of three incidents did not highlight any issues particular to Victoria.

Nevertheless, these actions cannot be assessed against a clearly defined incident response framework. DOH has policies and procedures for managing incidents, but there is no guidance on how they link together to form a seamless response. In addition, important details such as the criteria for escalating the level of response, and who makes some decisions, are lacking. Because of the lack of documentation, it was not evident whether DOH did all it should have to manage the risk that key people were not involved in incident response, that poorly informed decisions were made, or that unnecessary delays occurred at a time when good advice, clear thinking and quick responses were needed most.

Measuring and reporting performance

While undertaking compliance and enforcement activities is a key element of an effective regulatory regime, regulators also need to know whether they are delivering their programs as intended, consistent with their policies and procedures. To determine this, they should use quality assurance processes, such as accredited quality management systems and internal audit.

Agencies should also be routinely reporting on their performance to demonstrate how effectively and efficiently they are operating, and to indicate where improvement is needed. Effective performance reporting supports accountability, but this relies on agencies having relevant and measurable performance measures that show whether or not they are meeting their objectives and achieving their outcomes.

DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI all have sound approaches for reviewing the way they deliver their policies and procedures, and using the results to improve their performance. However, none have sufficient performance information to assure themselves on either the quality of their performance or the food safety benefits they deliver.

None of the regulators have clear measures, targets or benchmarks defining what they expect effective performance to achieve. Public reporting on compliance with Victoria’s agricultural food safety regulatory framework remains minimal. While there is some reporting on complaints and prosecutions, there is little available on compliance or trends in performance over time. There is little similarity in reporting between agencies, making it difficult to assess performance across the agricultural sector.

There is also no statewide food safety performance reporting framework despite this office in 2002 and 2005 and the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission in 2005 and 2007 recommending that better performance reporting is needed to provide public accountability for the food safety system’s effectiveness. Public reporting across the system almost exclusively describes activities and rarely demonstrates how these contribute to achieving goals or objectives.

Coordinating and overseeing regulatory and compliance effort

Victoria’s food safety system involves multiple agencies—including the food safety regulators—implementing the national food regulation framework through a number of state-based risk and compliance management tools. To be effective, the system needs to be supported by effective coordination and oversight, shared purpose and goals, and a clear understanding of system-wide risks.

Victoria’s food safety system is part of the national food regulation framework and involves all the appropriate agencies in implementing the national food standards. While the Committee of Food Regulators (CFR) provides an effective coordinating role, the system’s effectiveness in driving improved food safety outcomes is weakened by the narrow focus of the CFR’s draft strategic plan, unclear accountability for achieving the plan, and an absence of information about the performance of the food safety system. Accountability for achieving the plan needs to be determined, and CFR’s 2012 review of its operations and effectiveness provides a timely opportunity to do this.

Recommendations

- The Department of Primary Industries should strengthen its risk-based rationale for monitoring chemical use compliance and how it analyses results and uses this to improve compliance.

- The Department of Health should develop a food safety incident response plan that describes how its policies and procedures link together, supported by policies and procedures that are specific about what the criteria for action are, what needs to be done and who is responsible.

- The Department of Primary Industries, Dairy Food Safety Victoria and PrimeSafe should include more comprehensive performance data in their public reports, with clear links between objectives, performance measures and performance data.

- The Committee of Food Regulators should develop a performance reporting framework for Victoria’s food safety system, identifying the performance measures, data and public reporting that will provide assurance of food safety outcomes and the performance of the system.

- The Department of Primary Industries should clarify its role in regulating and managing agricultural food safety and integrate this work more strongly into the broader food safety system.

- When reviewing its operations and effectiveness in 2012, the Committee of Food Regulators should definitively assign accountability for the success of the strategic plan and for agency-specific actions to support the strategic plan.

-

The Committee of Food Regulators should expand the

strategic plan to:

- include a common strategic direction for food safety outcomes across the food supply chain from agricultural production to consumer

- identify statewide objectives, desired outcomes, performance indicators and targets for food safety, in addition to the regulatory goals already included

- be based on a clear program logic for how actions will contribute to achieving regulatory goals and food safety outcomes

- assign responsibilities and resources for delivering the actions required to achieve the objectives

- encompass all food safety agencies, including the Department of Primary Industries.

- Victoria’s overall food safety system should include a framework for reviewing and prioritising risks across all food sectors and agencies, selecting the best approaches for managing the significant risks, and allocating regulatory, advisory and surveillance efforts.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Primary Industries, the Department of Health, Dairy Food Safety Victoria, PrimeSafe and the Victorian Committee of Food Regulators with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments however, are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Victoria’s agricultural food industry

Victoria's agricultural industries produce raw animal and plant-based food products, such as dairy, meat, seafood, eggs and horticultural products. Together, these industries produce food valued at around $9 billion each year, and 26 per cent of the national agricultural production. Over half of Victoria’s contribution is from the dairy, beef and horticulture industries with the state's largest export earner, the dairy industry, providing around 87 per cent of Australia’s dairy exports.

1.1.1 Agricultural food safety

The entire food supply chain has a role in making food safe to eat, from on-farm producers through to manufacturers, retailers and consumers. Agricultural food safety involves managing the primary production and processing of raw agricultural products. This encompasses activities on farms, transportation, and the facilities involved in processing and handling raw products.

Food safety risks can arise from poor management practices at any stage of the supply chain. They can include poor controls over the use of chemicals and veterinary medicines, and problems with facilities, hygiene, temperature control and handling practices of food items.

In Victoria, a mix of regulation, education, advice and research are used to manage food safety risks and implement the national Food Standards Code. There are strong incentives across Australia for primary producers and processors to produce safe food, or risk their businesses, their market share and the national and international reputations of their industries.

Victoria’s rates of foodborne illness are generally lower than the Australian average. For example in 2009, Victoria had 30 cases of salmonellosis—a form of gastroenteritis resulting from infection with the Salmonella bacterium—per 100 000 people, compared with the national average of 44.

Foodborne illness data are not very useful for measuring how well food safety is being managed, partly because many factors can influence food safety outcomes. Further, as mild illnesses often go unreported, the data provide only an indication of the rate of illness. Also, because disease outbreaks are rare, it is difficult to detect trends in the data.

1.2 The Victorian food safety system

Victoria is part of an intergovernmental agreement between the Australian, state and territory governments. This agreement sets the national framework for food regulation, which includes model legislation and uniform food standards.

The framework is guided by the decisions and priorities of the Australia New Zealand Food Regulation Ministerial Council. Food Standards Australia New Zealand (FSANZ) provides the uniform food standards through the Australia New Zealand Food Standards Code (the Code).

The Code comprises specific standards covering composition, labelling, and food safety. Primary production and processing standards that relate specifically to agricultural food safety have been included progressively since 2006. The seafood standard was the first of these implemented. Since then, the dairy, poultry and egg standards have also been introduced and standards for raw milk products, seed sprouts, red meat and horticulture are being developed.

Not all of the food standards are about food safety. The Code also covers additional food quality and integrity issues such as labelling, nutrition and food definitions. The Code and its standards are given effect through state and territory legislation.

While the Ministerial Council and FSANZ set the policy and standards, the states decide how they will implement them. Victoria adopts the Code and the model food legislation in full through state legislation, and is responsible for compliance with it.

In Victoria, the food safety system is based on the policy and regulatory activities of the responsible agencies under relevant legislation, and the food safety assurance work by food businesses.

1.2.1 Agricultural food safety legislation

The Department of Health (DOH), Department of Primary Industries (DPI), Dairy Food Safety Victoria (DFSV) and PrimeSafe all have important responsibilities for supporting Victoria’s food safety system as it relates to the agricultural sector. These agencies conduct their functions under the following legislation.

Food Act 1984

The Food Act 1984 is the principal Act for food safety, and takes precedence in the event of any inconsistencies with other legislation and is administered by DOH. It mandates that all food must be safe for human consumption and requires compliance with the Code in Victoria. The regulation provisions under the Act apply only to the preparation and sale of food, specifically exempting primary production and processing. These are regulated through industry specific Acts. It also contains general offences relating to unsafe food handling and selling unsafe food, and emergency powers such as recalling food from the market that apply to all persons, including primary production businesses.

Industry-specific Acts

The meat and dairy industries have a longer history of regulation in Australia than other agricultural sectors, as a result of the recognised higher food safety risks in these sectors. Victoria was one of the first states to introduce meat and dairy food safety legislation, in the early 1990s, when the approach to managing food safety shifted from relying on government inspections to requiring food businesses to have effective systems for managing food safety.

The current Dairy Act 2000, Meat Industry Act 1993 and Seafood Safety Act 2003 put regulatory systems in place, which require businesses to manage food safety risks in accordance with relevant standards. The Dairy Act 2000 is administered by DFSV and the meat and seafood Acts by PrimeSafe.

Agricultural production Acts

DPI administers legislation governing good agricultural practice, designed to support market access for Victoria’s agricultural products while at the same time protecting public and environmental health. The Acts with the strongest influence on food safety are:

- the Agricultural and Veterinary Chemicals (Control of Use) Act 1992, which controls the use, application and sale of agricultural and veterinary chemical products, fertilisers and stock foods, and in doing do minimises chemical residues in food

- the Livestock Disease Control Act 1994 and Livestock Management Act 2010, which govern livestock health and disease management, including diseases that could impact on food safety.

Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008

The Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 is administered by DOH and supports human disease surveillance and control, including foodborne diseases. It requires mandatory reporting of certain food pathogens when detected in food or in the population.

1.2.2 Regulatory framework

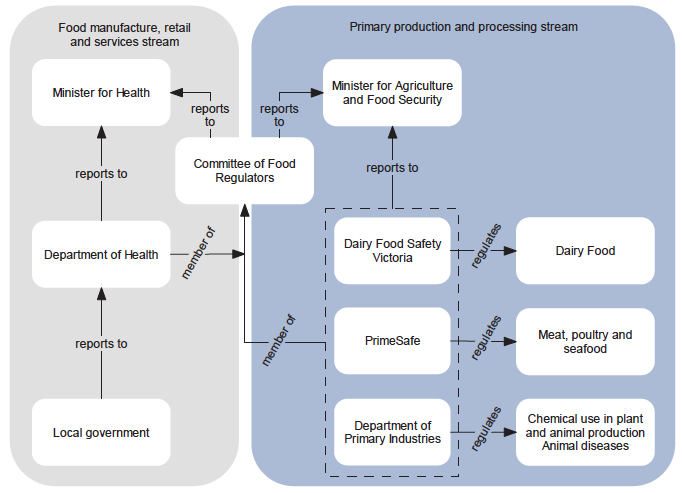

The Victorian food safety system has two ‘streams’ that regulate compliance with food safety requirements:

- The food manufacturing, retail and service sectors stream—regulated by local councils with the oversight of DOH, under the Food Act 1984. DOH reports to the Minister for Health.

- The agricultural production and processing sectors stream—regulated by the two statutory authorities, PrimeSafe and DFSV, for the meat, seafood and dairy sectors under the three industry food safety Acts. DPI regulates chemical use and animal disease management. These agencies report to the Minister for Agriculture and Food Security.

Figure 1A gives an overview of the regulatory framework in Victoria.

Figure 1A

Victoria’s food safety system

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The operation of the system is supported by the Victorian Committee of Food Regulators (CFR) which, through its strategic plan, aims to bring about a statewide, integrated approach to food regulation. In addition, the Food Safety Council, comprised of food safety experts, advises the Minister for Health and the Secretary of the Department of Health.

In addition to the food safety legislation and regulatory framework, industry quality assurance programs are an important part of the food safety system. The regulators recognise existing industry quality assurance programs that meet food safety requirements.

1.2.3 Agency roles and responsibilities

The regulatory framework for the agricultural stream involves four agencies, responsible for implementing eight Acts related to food safety in agricultural production and processing. Their primary responsibilities are outlined in this section.

Department of Health

DOH has overall responsibility for administering and enforcing the Food Act 1984. It also supports and oversees the performance of local government in regulating food manufacturing, retail and service businesses. While primary production and processing is excluded from much of the Act, DOH’s powers for enforcing food offences and emergency response apply across the whole food supply chain. It is also responsible for foodborne disease surveillance under the Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008.

DOH has overall leadership and coordination responsibilities across the food safety system, which includes:

- coordinating the whole-of-government advice and input to the national food safety framework

- briefing the Minister for Health as the lead Victorian representative on the Australia New Zealand Food Regulation Ministerial Council.

Department of Primary Industries

DPI’s Agriculture and Food Industry Policy branch develops and implements food safety policy advice relating to primary production and processing for the state system and as part of Victoria’s whole-of-government input to the national policy and standards. It briefs the Minister for Agriculture and Food Security as a member of the Australia New Zealand Food Regulation Ministerial Council.

DPI's Biosecurity Victoria division's regulatory framework underpins food safety by governing chemical use and animal health management on farms. The multiple purposes of these Acts include protecting public health as well as supporting good agricultural practice and market access for agricultural products. Chemical use is regulated as part of a national framework regulating the availability of agricultural and veterinary chemicals.

PrimeSafe

PrimeSafe has specific regulatory responsibilities for agricultural food safety, which are licensing red meat, poultry and seafood processors and monitoring their compliance with national standards, state legislation and additional permit conditions. This includes approving and monitoring business food safety programs so that food standards are maintained.

PrimeSafe does not have any current responsibility for on-farm production. However, from May 2012, the introduction of the national primary production and processing standard for the poultry meat industry will mean PrimeSafe will be responsible for regulating poultry production on farm. However, it is not intended that PrimeSafe will license poultry farms, but rather the food safety systems of poultry processors will extend to assuring the food safety of their poultry suppliers. A primary production and processing standard for red meat is being developed and may require a similar role for PrimeSafe.

Dairy Food Safety Victoria

DFSV has specific regulatory responsibilities for agricultural food safety, which are licensing dairy producers and processors and monitoring their compliance with national standards and state legislation and regulations. This includes approving and monitoring business food safety programs to make sure food standards are maintained. DFSV’s responsibilities include on-farm production as well as processing.

Committee of Food Regulators

The CFR was established in 2010 to improve coordination and consistency between regulators. In addition to DOH, DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI, its membership includes:

- the Municipal Association of Victoria—representing local councils

- Consumer Affairs Victoria—the state regulator for deceptive and misleading conduct, which is also regulated under the Food Act 1984

- Local Government Victoria—providing advice on local councils.

The CFR’s primary responsibilities are to:

- develop a strategic plan for food regulation in Victoria, regularly monitor its progress and coordinate reports to responsible ministers

- oversee the overarching memorandum of understanding between Victorian food regulators and its ongoing operation.

1.2.4 Recent food regulation reforms

The Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission’s (VCEC) 2007 report, Simplifying the Menu: Food Regulation in Victoria recommended many changes to food regulation, including how food safety is managed. The initial focus of the food safety agencies in implementing the recommendations was to amend the Food Act 1984 and improve the way councils regulate the manufacturing, retail and food services stream, as well as strengthen DOH’s role in supporting and overseeing the councils.

VCEC also made several recommendations for improving how the state food safety system is managed, including establishing a committee of food regulators, developing a strategic plan for food regulation and improved performance reporting. These changes will influence how agricultural food safety, as a component of the food safety system, is managed. The CFR is already established and work to implement other recommendations is now underway.

1.3 Audit objective and scope

The objective of the audit was to examine how effectively agricultural food safety is regulated in Victoria. The audit examined how well the overall assurance framework for food safety in Victoria addresses food safety in primary production and processing, and how effectively compliance with the legislation was regulated.

This audit reviewed the activities of DOH, DPI, PrimeSafe and DFSV in managing agricultural production and processing. It also examined the activities of the Victorian Committee of Food Regulators as they relate to agricultural food safety. It did not examine food imports, which are managed by the Australian Government.

1.3.1 Audit approach

The audit examined whether:

- there is a sound agricultural food safety system, underpinned by an effective regulatory framework

- sound risk-based systems and processes are used to monitor compliance with, and enforce, agricultural food safety regulations and standards

- continuous improvement occurs, supported by performance monitoring and reporting.

The audit was performed in accordance with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost of this audit was $345 000.

2 Regulating agricultural food safety

At a glance

Background

Food safety regulation needs to be underpinned by effective compliance monitoring and enforcement, as well as processes to assess regulatory performance, and to coordinate regulatory activity.

Conclusion

The regulation of agricultural food safety is generally effective, with active, risk-based monitoring of compliance with food safety standards. Improvements are required in some areas, particularly in assessing the performance of the regulators and the impact of regulatory activities.

Findings

- The regulators are managing compliance well, with clear rules and requirements to manage food safety and sound practices for monitoring, enforcing and supporting compliance with them.

- None of the regulators have sufficient performance reporting to provide them with strong assurance regarding the quality of their performance and the food safety benefits they deliver.

- The potential effectiveness of Victoria's food safety system in driving improved food safety outcomes is weakened by the narrow focus of the Committee of Food Regulators' draft strategic plan, and unclear accountability for the success of the plan.

Recommendations

- The Department of Health should develop a food safety incident response plan that describes how its policies and procedures link together.

- The Department of Primary Industries, Dairy Food Safety Victoria and PrimeSafe should include more comprehensive performance data in their public reports.

- The Committee of Food Regulators should develop a performance reporting framework for Victoria's food safety system.

- The Committee of Food Regulators should definitively assign accountability for the success of the strategic plan.

- Victoria's overall food safety system should include a framework for reviewing and prioritising risks across all food sectors and agencies.

2.1 Introduction

Agricultural food safety is one component of a broader food safety system, alongside the food manufacturing, retail and services component regulated by local government and supported by the Department of Health (DOH).

Victoria's food safety regulation is used to manage high-risk practices or sectors in the food supply chain so that they comply with the national food standards and legislative requirements. Given the potential for health impacts, the regulatory approach needs to be underpinned by effective compliance monitoring and enforcement activities to provide assurance that licensees are adhering to regulations and licence conditions. There also need to be processes to assess regulatory performance, and to coordinate regulatory activity.

2.2 Conclusion

Dairy Food Safety Victoria (DFSV) and PrimeSafe are regulating food safety effectively. They are actively monitoring and enforcing compliance with food safety standards, and have clear rationales for their risk-based approaches to this work. Audit examinations show they apply their policies and procedures consistently and have sound controls in place for managing the quality of this work. The Department of Primary Industries (DPI), while effective in some areas, needs to strengthen the risk‑basis for its chemical use compliance monitoring.

However, across the three agencies assurance about the effectiveness and impact of their activities is limited, because they do not have clear performance measures or benchmarks defining what they expect effective performance to achieve. This limits the ability of the regulators to attribute their regulatory work to positive food safety outcomes in Victoria and monitor their performance.

A process for assessing the performance of the broader food safety system is also needed. This would provide assurance about the performance of the regulators and indicate whether food safety risks across all food sectors and parts of the food supply chain are being managed well, and whether regulatory effort is being directed where it can generate the largest benefits in reducing risks.

While agricultural food safety is part of a broader food safety system, underpinned by a strategic plan to guide effort and memoranda of understanding (MOU) to support cooperative approaches and consistency between regulators, action needs to be taken to improve the effectiveness of the system. This includes providing stronger assurance that food safety risks are being systematically identified and managed, and clarifying and assigning accountability for achieving the overall goals of the plan.

2.3 Managing compliance with food safety regulation

To regulate effectively, the agencies regulating food safety need to have in place clear food safety rules and requirements. They also need to efficiently and effectively administer and enforce them, which involves supporting businesses to understand and apply the requirements, monitoring how well businesses comply and applying sanctions to serious compliance breaches.

The three agencies—DPI, DFSV and PrimeSafe—are generally managing compliance well. Clear rules and requirements are in place for how agricultural production and processing businesses need to manage food safety, as are sound practices for monitoring, enforcing and supporting compliance with them.

2.3.1 Food safety requirements for primary production and processing businesses

Victoria's agricultural food safety regulators have clearly defined responsibilities under their respective legislations to safeguard public health. PrimeSafe's and DFSV's responsibilities for regulating compliance with food safety standards are clearly set out in the dairy, meat and seafood legislation. They include:

- maintaining and improving the food safety standards of food products, premises and transport vehicles

- monitoring and reviewing the standards

- licensing food businesses

- approving and monitoring the implementation of licensees' food safety programs.

DPI's responsibilities for regulating compliance with chemical use and animal diseases regulations are also identified in legislation. These include licensing the use of high‑risk chemicals, protecting Victoria from biosecurity threats and responding to emergencies. While DPI's focus is predominantly on good agricultural practice and protecting domestic and export markets, the legislation is clear that the responsibilities involve protecting public health, which includes food safety.

Each agency uses a range of regulations, standards and codes of practice to support the implementation of the national food standards and the state legislation. The agencies clearly identify what food safety requirements the primary production and processing businesses need to comply with:

- DFSV and PrimeSafe require compliance with legislation, standards or licence conditions, including the requirement to have an approved food safety program. Each regulator has effective policies and procedures in place to guide consistent and transparent decisions on licence approvals.

- DPI requires individuals and entities that use high‑risk agricultural chemicals to have either a licence or a permit. Producers are also required to maintain records of chemical use. DPI has generally effective procedures for permit and licence approvals.

- DPI also requires livestock producers to individually identify their animals, so they can be tracked from place of birth to slaughter. Producers are required to declare important information about certain diseases and the treatment status of livestock being sold, using the National Vendor Declaration.

Agricultural industries such as horticulture, grains, eggs and honey are not actively regulated and have no single agency overseeing or managing food safety. They are governed by Food Act 1984 provisions related to supplying or selling unsafe food or handling food in an unsafe manner. These industries rely on self-regulation and voluntary codes of practice to achieve compliance with food standards. This will change during 2012–13 for the egg industry and seed sprouts, when the new national primary production and processing standards for these industries are implemented in Victoria.

This model of relying on industry self-regulation is a reasonable approach at this time given that nationally, food safety risks for these products is low to medium. In addition, both state and national product testing and foodborne illness data have indicated low risks, and there was only one recall of Victorian products from these industries between January 2010 and August 2011.

2.3.2 Monitoring compliance with requirements

DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI have sound, risk-based processes for monitoring compliance and managing non-compliance with food safety requirements, and each is generally consistent in applying them. In addition, each agency's licences and/or permits clearly specify how businesses should demonstrate compliance with the food safety requirements. This is an effective approach, given the generally high compliance rates, low incidence of repeat offenders and rare need to prosecute.

Dairy Food Safety Victoria and PrimeSafe

DFSV and PrimeSafe monitor compliance by all licensees, which total around 5 000 for DFSV and 2 100 for PrimeSafe. Each considers the food safety risks inherent in different production and processing sectors in deciding how intensively to monitor compliance in each sector.

All DFSV and PrimeSafe licensees have routine audits as part of licence conditions at a frequency determined by the risk-rating of their licence. For DFSV's licensees, this ranges from at least every two years for dairy farms to twice a year for manufacturers. For PrimeSafe's licensees it ranges from at least once a year for seafood businesses to at least four times a year for smallgoods manufacturers.

Where non-compliance is identified, DFSV and PrimeSafe have effective processes to respond, requiring the non-compliance to be fixed within a certain time. Both agencies intensify their compliance efforts with licensees that demonstrate serious or repeat non-compliance, identified during audits or through poor testing results. This includes weekly audits following serious breaches, until the licensee demonstrates sustained compliance.

The increased audits also act as a financial penalty as the licensees have to pay for them. DFSV and PrimeSafe require proof of sustained compliance to revoke the increased scrutiny. Less than 2 per cent of licensees have repeat breaches, indicating the agencies' compliance approaches are generally effective.

Each uses clear criteria to define serious compliance breaches. The main trigger is an audit that identifies a 'critical' corrective action request. Both agencies apply the national definition that this represents an immediate or substantial risk to human health. PrimeSafe's criteria also include any sulphur dioxide detected in meat products other than sausage meat. These agencies also use information from their own, and national, product testing and surveillance programs to support this work.

Data provided to VAGO indicate that the licensees that DFSV and PrimeSafe regulate have high levels of compliance. Only around 6 per cent of licensees commit significant compliance breaches, such as failing to use the right temperature to control pathogens. Production is stopped if a serious or immediate threat to public health is identified. Rates of product recalls are low, with nine for dairy, four for meat and none for seafood products manufactured in Victoria between January 2009 and August 2011. Combined with high compliance levels, this indicates that compliance monitoring is effective.

Department of Primary Industries

DPI also considers the food safety risks of different agricultural sectors in determining the frequency and spread of its compliance monitoring. However, unlike DFSV and PrimeSafe, which focus on food safety, DPI's risk consideration includes a wider range of hazards associated with its broader focus on good agricultural practice, as well as food safety. These additional considerations include potential environmental impacts from agricultural chemical use and animal welfare issues.

DPI has the challenge of working with many more permit holders and licensees—close to 20 000—across a diverse range of industries.

In 2008 DPI introduced a four-year cycle of support and compliance monitoring to better address chemical use compliance risks. It aims to audit around 1.5 per cent, or 280, of its 19 000 chemical use permit holders and 10 per cent of the 300 businesses licensed to apply chemicals each year.

The adequacy of the audit sample size is unknown as DPI does not have a documented risk-based rationale for how the numbers were determined. The size of the audit sample is influenced more by available resources—seven authorised officers—than by the number of audits needed to give a representative picture of compliance and therefore of how well compliance risks are being controlled. To get good value from its audit program, DPI needs a clear, risk-based rationale for the size of its audit sample and a more rigorous approach to how it analyses results and uses this to improve compliance.

Also, DPI's need to respond to emerging government priorities, such as delivering other biosecurity actions and responding to incidents, means the audit target is rarely achieved. For example, in 2010–11 it conducted only 88 of its scheduled audits due to the need to respond to the locust plague, but added around 65 audits and 500 product tests as part of the locust response.

Compliance with chemical and disease regulations varies widely across DPI's permit and licence holders. For example, there was 86 per cent compliance with some animal disease controls but in one irrigation area only 46 per cent compliance with chemical use requirements. However, the significance of this in relation to food safety is low as testing rarely shows potentially unsafe residue levels in fresh produce. For example, Victoria's 2009–10 chemical residue sampling program showed over 97 per cent compliance with maximum allowable residue levels. Chemical residues are unlikely to appear in food products because the national chemical management system only registers chemicals for use in Australia if there are no known food safety risks. Also, farmers using registered chemicals are required to withhold produce from harvest or sale for a safe period after applying the chemicals.

Like DFSV and PrimeSafe, DPI also intensifies its compliance efforts with businesses or industries with repeat compliance breaches. Repeat breaches may trigger re-audit and may also lead to enforcement action. Because of the small sample of permit holders and licensees audited, and DPIs relatively new approach, it was difficult to determine its effectiveness.

DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI also investigate unacceptable product testing results and complaints, which can be about both licensed and permitted businesses as well as those operating illegally. Investigations are followed with increased scrutiny over compliance and/or enforcement action as needed.

2.3.3 Enforcing compliance

DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI all have enforcement policies and/or procedures in place for using the suite of enforcement powers provided by their legislation, including warning or advisory letters, prohibition notices and orders as well as prosecution. These specify how a graduated enforcement response, proportionate to the food safety risk associated with the compliance breach and the business' compliance history, should be applied.

Each agency demonstrated how it applies its enforcement powers in proportion to the assessed food safety risk of the breach and the licensees' willingness to comply. In each agency, few licensees or permit holders needed significant enforcement action, such as stopping production. Prosecution was also rarely used. For example, DFSV and PrimeSafe did not prosecute any licensees in 2009–10 or 2010–11, while DPI prosecuted four permit or license holders for chemical use compliance breaches.

Good licensee compliance rates and low levels of enforcement and food safety incidents for dairy, meat and seafood products, indicate that the different approaches used by DFSV and PrimeSafe work well to promote compliance. PrimeSafe has detailed processes and criteria guiding how it applies its different enforcement powers, including how it responds to repeat offenders. DFSV has general enforcement guidance, and is developing a new enforcement model to guide its graduated approach, but does not specify criteria for increasing enforcement, instead taking a case-by-case approach.

DPI also has a detailed enforcement process and clear criteria triggering enforcement action, but it was not clear how it assessed its effectiveness in applying these. DPI should include a specific focus on enforcement when it evaluates the success of its new operating model for regulating chemical use, planned for 2013.

DFSV recently reviewed the effectiveness of its enforcement policies for the small number of licensees with multiple and high risk compliance breaches, and is adjusting its approach in response to this. PrimeSafe also reviewed its work with the small proportion of licensees with multiple serious breaches and adjusted its compliance approach to better address licensees with repeat breaches.

2.3.4 Supporting compliance with education and advice

DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI all encourage compliance through advisory support, to complement their monitoring and enforcement activities. Each agency uses data from audits, inspections, testing and complaints to identify compliance problem areas.

DFSV and DPI target problem areas using a range of complementary approaches to provide information, education, training and advice to individual businesses and industry associations. DFSV's annual external audit for accreditation with international quality management standards has noted the strength of its approach. DPI's approach is relatively new and due for review in 2013.

PrimeSafe's auditors provide advisory support to licensees but PrimeSafe has determined that, as a regulator, it should not have a direct role in education and nor is it staffed to deliver it. PrimeSafe advised that it seeks to improve education by supporting industry associations and educational bodies to deliver it, but could not demonstrate how it does this.

DFSV's and DPI's planning documents each demonstrated a strong rationale for their approaches to working with industry to improve compliance, and using industry feedback to guide their actions. PrimeSafe should similarly document its rationale for not including education as part of its core activities, and its strategy for supporting industry and other organisations to deliver the education needed.

2.3.5 Responding to incidents

DOH has primary responsibility for food safety incident response, which applies whether it is an incident relating to the agricultural food safety stream or the manufacturing, retail and food service stream.

The audit examination of recent incidents showed DOH communicated clearly and frequently with other agencies, sought advice and information and used its enforcement powers as a last resort. Recent national reviews of three national incidents did not highlight any issues particular to Victoria.

However, there is little assurance that DOH's actions are effective because they cannot be assessed against a clearly defined incident response framework. Because of the lack of documentation, it was not evident whether DOH did all it should have to manage the risk that key people were not involved in incident response; that poorly informed decisions were made; or that unnecessary delays occurred at a time when good advice, clear thinking and quick response were needed most.

DOH has a draft State Health Control Plan with high level guidance on managing public health emergencies, including food emergencies. It also has arrangements in place for how it will work with DPI and DFSV during incidents. However, its approach is insufficient because:

- there is no food safety incident response plan or process map to show how all these procedures link together

- it is not clear what criteria are used to scale up the level of response, decide when the response can be scaled back, or select the appropriate enforcement action, such as an order to publish warnings, prohibit sales or recall products

- the procedures are largely undated, uncontrolled documents, often in draft and often do not specify decision-making responsibilities or timing, reporting, or resourcing requirements

- there is no documented process for checking that all products that need to be withdrawn from sale have been

- DOH does not always review how it has responded to incidents, to improve performance.

This means that DOH does not have the guidance in place needed to secure a level of incident response and enforcement that is appropriate to the risk and is in place only as long as it is needed. The lack of clear criteria also reduces DOH's assurance that similar cases will be managed consistently and fair decisions will be made.

DOH is currently improving its system for managing food regulation incidents and emergencies and the way it responds to health protection incidents in general.

2.4 Regulator performance

While undertaking compliance and enforcement activities is a key element of an effective regulatory regime, regulators also need to know whether they are delivering their programs as intended, and consistently with their policies and procedures. To determine this, they should use quality assurance processes, such as accredited quality management systems and internal audit.

Agencies should also routinely report on their performance to demonstrate how effectively and efficiently they are operating and indicate where improvement is needed. Effective performance reporting supports accountability but relies on agencies having relevant and measurable performance measures that show whether or not they are meeting their objectives and achieving their outcomes.

DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI all have sound approaches to reviewing the way they implement their policies and procedures, and using the results to improve their performance. None, however, has performance reporting comprehensive enough to provide them with the information they need to assure themselves of the quality of their performance and the benefits to food safety that they deliver. There is no statewide food safety performance reporting framework.

2.4.1 Agency quality management systems

DFSV, DPI and PrimeSafe have sound processes to manage both the quality of the work of their auditors and authorised officers, and the quality of their compliance monitoring and enforcement systems.

DFSV's and PrimeSafe's quality assurance systems are accredited to the international quality management standard. DPI has similar accreditation for its quality systems in many of its high-risk operations and uses an external auditor to review others. These provide independent assurance that the agencies are applying their compliance and enforcement systems consistently and fairly. All demonstrated how they changed their practices in response to the recommendations from these process reviews.

Each agency has robust processes for accrediting and/or training auditors and authorised officers. DFSV and PrimeSafe both use contract auditors accredited through national or bi‑national accreditation schemes and manage their activities in line with the national policy and guidelines for food safety auditors. DFSV and PrimeSafe set performance standards and expectations, and monitor, review and address performance issues with their contract auditors. They similarly monitor and manage the performance of their own authorised officers in conducting audits.

All of DPI's audits are conducted by its authorised officers, who must have specific qualifications and meet internal training requirements. DPI assesses their work through its staff performance management system.

2.4.2 Measuring and reporting performance

DFSV, DPI and PrimeSafe do not have clear measures, targets or benchmarks defining what they expect effective performance to achieve. Public reporting on compliance with Victoria's agricultural food safety regulatory framework remains minimal. While there is some reporting on complaints and prosecutions, there is little on compliance or trends in performance over time. There is little similarity in reporting between agencies, making it difficult to assess performance across the agricultural sector. For example:

- DFSV's reporting includes licence statistics, prosecutions and residue testing results but not compliance rates, complaints, other enforcement actions or microbiological testing results

- PrimeSafe's reporting includes licence statistics, prosecutions, complaints and sulphur dioxide testing, and trends in prosecutions and complaints, but not compliance rates or other enforcement actions

- DPI's reporting includes compliance rates, testing, enforcement and prosecutions, but only for some of its permit and licence holders or industry sectors, and does not include complaints.

In its 2005–10 corporate plan, PrimeSafe recognised limitations existed with its performance reporting. It identified the need to measure its business performance and use this information to better identify and manage business risks. It committed to improving its performance reporting but this did not happen, and is not part of its 2010–15 plan. This is a missed opportunity that PrimeSafe should revisit.

Recognising the importance of the food safety regulators reporting publicly on their performance, in 2011 the Minister for Agriculture and Food Security directed PrimeSafe and DFSV to report publicly on their food safety performance. While the move to greater transparency and accountability is a good initiative, the issue of what the agencies should report remains unresolved. The agencies need to determine what should be reported, how the information should be used to provide assurance and inform decisions, and how it should link to broader food safety assurance reporting.

DFSV and PrimeSafe have a high degree of independence but need to balance this with better public assurance about their performance. DPI also needs to improve its public reporting. Each needs to develop a balanced set of relevant and appropriate performance measures and targets or benchmarks for the range of their activities, and report against them.

2.4.3 Measuring and reporting food safety system performance

There is no statewide food safety performance reporting framework despite this office in 2002 and 2005, and the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission in 2005 and 2007, recommending that better performance reporting is needed to provide public accountability for the food safety system's effectiveness. This is because accountability for performance reporting over the whole food safety system has not been assigned.

The Committee of Food Regulators (CFR)—established to support improved public health outcomes, industry performance and consumer confidence—has performance reporting as one of its terms of reference. Specifically, it is required to oversee a common approach to food safety performance reporting systems and report annually on performance. However, performance reporting is not part of its strategic plan, and CFR's work plan and meeting agendas do not include performance reporting. It is unlikely, therefore, that there will be any progress in establishing system-wide performance reporting before CFR reviews its operations and effectiveness in June 2012 and presents its findings to the Ministers for Health and Agriculture and Food Security for consideration.

Public reporting across the system almost exclusively describes activities and rarely demonstrates how these contribute to achieving goals or objectives. Performance reporting on statewide food safety achievements should be designed to assure the effectiveness of food safety management, benchmark performance and support agencies in allocating resources and improving performance. Common measures across different agencies or sectors provide an opportunity to compare consistency and effectiveness. Public reporting across the system does not replace individual agency needs to report against legislative requirements and agency objectives, priorities and measures.

In addition to the lack of reporting on the performance of the agricultural food safety system, there is currently only minimal reporting on complaints and enforcement. DOH's public reporting on infectious diseases identifies incidences and trends in foodborne illness. The most recent annual report available was from 2008, although it also publishes quarterly data. DOH does not report on compliance with the Food Act 1984, or on recalls of Victorian products but will begin reporting on compliance annually from 2012.

Doctors and analytical laboratories are required to report health risk pathogens to DOH, providing strong data related to actual and potential foodborne illness incidence. The data indicate that Victoria's levels of foodborne illness are below the national average. However, it is often difficult to identify the cause of the illness, so data on the extent to which illness stems from food safety failures in primary production and processing is not reliable.

Food businesses usually voluntarily recall products if their testing, records or complaints suggest there may be a food safety risk. DOH can order businesses to recall a product but this power is used very rarely. Recall data is much more specific about the source of the potential food safety issue. However, while DOH collects Victoria's recall data it:

- does not collate all voluntary food safety recalls by manufacturers

- conducts little analysis of trends over time in recall product type, source of recall or comparison with national data.

DOH needs to improve the way it records and analyses recall data, and use this information to support better food safety compliance management and monitoring.

Following changes to the Food Act 1984, from 2011–12 DOH will include information on its and local governments' compliance activities in regulating food premises and retail businesses in its annual report. There is no requirement for DFSV, PrimeSafe and DPI to include similar information in their reports. Such information, however, would improve their accountability and better enable Parliament to assess their performance.

Further work is needed to develop a comprehensive performance reporting framework based on performance measures and data selected to demonstrate food safety outcomes, effective risk management and continuous improvement. This would strengthen assurance that food safety regulation is managing identified risks and delivering proportional benefits for public health and the food business sectors.

The agencies will need to decide how to do this most efficiently; adding to, rather than duplicating, the data they already collect and the reporting they already do. They will need to identify:

- what aspects of performance need to be measured, and how the information will be used

- relevant performance indicators and the data that will measure them

- how the data will be collected and collated

- how performance will be reported.

2.5 Coordinating and overseeing regulatory and compliance effort

Because Victoria's food safety system involves multiple agencies, to be effective the system needs to be supported by coordination and oversight, a clear understanding of system-wide risks, and shared purpose and goals.

Victoria's food safety system is part of the national food regulation framework and involves all the appropriate agencies in implementing the national food standards. However, its potential effectiveness in driving improved food safety outcomes is weakened by the narrow focus of CFR's draft strategic plan, and unclear accountability for achieving the plan.

2.5.1 Coordination

Since it was established in 2010 in response to the recommendation of the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission's 2007 inquiry into food regulation, the main mechanism for coordinating the food safety agencies across the system is the CFR. In addition to supporting improved public health outcomes, industry performance and consumer confidence, its purpose is to improve coordination, and the consistency and efficiency of regulation. The CFR reports annually to the ministers for Health and Agriculture and Food Security.

Coordination across the system is generally effective, supported by an overarching MOU between the food safety regulators across both streams of food safety regulation—DOH, DFSV, PrimeSafe and the Municipal Association of Victoria, representing local councils. The MOU describes how responsibility for different types of dairy and meat manufacturing and retail premises is assigned between councils and DFSV, and councils and PrimeSafe.

Three additional MOUs have been developed, between DFSV and DPI, between DFSV and DOH and between DPI and DOH. These clarify operational roles and responsibilities for specific issues between different agencies where there is potential duplication in their legislated roles. Scheduled, regular meetings are used to support the application of the MOUs.

The overarching MOU and the three additional MOUs have been used effectively. For example:

- examination of the few potential dairy and meat incidents that have occurred in recent years demonstrated that DOH worked with DFSV and PrimeSafe respectively to investigate them

- the MOU between DFSV and DPI streamlines arrangements for industry to demonstrate regulatory compliance and coordinate residue investigations. The agencies meet and report to each other regularly.

While the overarching MOU has been effective for the agencies it includes, CFR has improved the MOU by further clarifying responsibilities, for example relating to complaints about misleading information, waste management and licensing mixed businesses.

A limitation of the MOU is that it excludes DPI, even though its regulation of agricultural and veterinary chemical use and animal diseases is directly related to public health outcomes, including food safety. Its exclusion potentially sidelines it from active involvement in the cooperative approach to applying food regulation in Victoria, as its role in food safety is poorly integrated into the food safety system compared to the other food safety agencies. DPI needs to integrate its work more closely into the food safety system for the state to be able to achieve a truly 'seamless' approach to managing food safety.

2.5.2 Setting and achieving the strategic direction

Victoria does not have a clearly defined overall objective for food safety and no statewide description of what the food safety system is aiming to achieve. Instead, it has a range of disparate agency and sector specific objectives that do not align. In an effort to address this, CFR has developed a draft strategic plan.

As the first plan for food regulation that Victoria has had, the draft strategic plan for 2011–14 represents an important opportunity to set a common goal for what good food safety management can be expected to achieve in Victoria. The strategic plan is required to achieve the objectives of the CFR—specifically:

- improved public health outcomes

- improved coordination of regulators

- greater consistency of implementation

- improved industry performance

- improved efficiency

- more confident consumer participation in markets.

Through the development of a complementary implementation plan, the strategic plan will also identify the individual agency actions that collectively will achieve the objectives. There are, though, several short-comings in the draft plan that limit how the state might benefit.

It is unclear who is accountable for the success of the strategic plan. The CFR performs a coordinating role, and reports annually on the progress in delivering the plan. However, it has no power to impose decisions on any agency, and so is not accountable for the success or failure of the plan. The lack of clarity creates the potential for diffused accountability and for failure to achieve the overall goal.

While the implementation plan will assign responsibility for actions designed to achieve the objectives, it is also unclear how individual agencies will be accountable for their success or failure in achieving their commitments under the plan.

Accountability for achieving the plan needs to be determined. The plan itself needs to communicate what Victoria's goal is for reducing foodborne illness and set the direction for both regulatory and non-regulatory actions to achieve it. It needs to be complemented with a work plan that clearly assigns responsibilities, time lines and resourcing.

The strategic plan was developed in response to a recommendation from the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission's 2007 inquiry into food regulation, to foster a more integrated, statewide approach to food safety. It specified the plan should include:

- a rationale for how regulation is used to address risk

- short- and medium-term goals and priorities, and strategies and actions for realising them

- regular progress reviews based on relevant information for assessing progress.

The strategic plan has not been based on a holistic review of food safety risks. Without a risk review, there is no clear rationale underpinning the plan for how the actions are aligned with managing the risks, and what food safety goals or outcomes are expected to be achieved through managing the risks.

Because it is focused on improving regulation, and was developed to address specific needs identified by the Victorian Competition and Efficiency Commission, the plan does not include food safety risks that are not managed through regulation. It also excludes DPI's on-farm activities, which have an important impact on agricultural food safety.

The CFR's objective is to support the seamless operation of the Victorian food regulatory system, and to deliver improved public health outcomes as well as operational improvements such as better coordination. Its strategic plan has indicators that describe the improved administration expected, but not how this is expected to improve food safety or public health outcomes. This represents a missed opportunity for driving improved food safety outcomes.

The CFR's upcoming review of its operations and effectiveness could be used to consider the best approaches for expanding the strategic plan to drive improved outcomes.

2.5.3 Reviewing risks

Understanding the risks associated with agricultural food safety is a key element of effective regulation. It enables regulators to target compliance activity and also allocate resources appropriately.

At the three regulators involved in agricultural food safety, there are effective risk management practices that enable them to identify and respond to sector-specific risks. For example:

- the individual agencies monitor different state, national and international information sources and conduct targeted research to identify emerging or changing food safety risks, especially testing for food pathogens, chemical residues and foodborne illnesses

- the agencies are involved in Food Standards Australia New Zealand's consultations on food safety risk assessments as part of developing individual food standards

- the agencies and the Food Safety Council also examine specific risks as the need arises, for example in response to changes in agricultural production and processing policy (e.g. use of reclaimed water) and processes (e.g. butchers' increasing use of cryovac machines)

- DFSV, DPI and PrimeSafe also analyse and manage compliance risks posed by individual licensees and industries.

However, at a statewide level, there is no systematic review of the major food safety risks and of the best mix of approaches to manage them, including the need for regulation. There is no statewide process for:

- collating the information held by agencies and prioritising any gaps to be filled

- analysing the relative risks across different food businesses and parts of the food supply chain

- reviewing how successfully different actions manage existing risks.

The absence of a systematic and holistic risk management process in Victoria means there is no clear rationale for how actions to manage agricultural food safety risks are selected and resources allocated across the food safety system. Nor is it clear whether these actions remain proportionate to the risks in a changing risk environment and how they complement each other to achieve a seamless approach to food safety. For example, while Victoria benefits from industry self-regulation through voluntary quality assurance schemes that include food safety risks, there has been no assessment of whether this reduces risks and how it contributes to Victoria's food safety outcomes.

Recommendations

- The Department of Primary Industries should strengthen its risk-based rationale for monitoring chemical use compliance and how it analyses results and uses this to improve compliance.

- The Department of Health should develop a food safety incident response plan that describes how its policies and procedures link together, supported by policies and procedures that are specific about what the criteria for action are, what needs to be done and who is responsible.

- The Department of Primary Industries, Dairy Food Safety Victoria and PrimeSafe should include more comprehensive performance data in their public reports, with clear links between objectives, performance measures and performance data.

- The Committee of Food Regulators should develop a performance reporting framework for Victoria's food safety system, identifying the performance measures, data and public reporting that will provide assurance of food safety outcomes and the performance of the system.

- The Department of Primary Industries should clarify its role in regulating and managing agricultural food safety and integrate this work more strongly into the broader food safety system.

- When reviewing its operations and effectiveness in 2012, the Committee of Food Regulators should definitively assign accountability for the success of the strategic plan and for agency-specific actions to support the strategic plan.

-

The Committee of Food Regulators should expand

the strategic plan to:

- include a common strategic direction for food safety outcomes across the food supply chain from agricultural production to consumer

- identify statewide objectives, desired outcomes, performance indicators and targets for food safety, in addition to the regulatory goals already included

- be based on a clear program logic for how actions will contribute to achieving regulatory goals and food safety outcomes

- assign responsibilities and resources for delivering the actions required to achieve the objectives

- encompass all food safety agencies, including the Department of Primary Industries.

- Victoria's overall food safety system should include a framework for reviewing and prioritising risks across all food sectors and agencies, selecting the best approaches for managing the significant risks, and allocating regulatory, advisory and surveillance efforts.

Appendix A. Audit Act 1994 section 16—submissions and comments

In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Primary Industries, the Department of Health, Dairy Food Safety Victoria, PrimeSafe and the Victorian Committee of Food Regulators with a request for submissions or comments.

The submission and comments provided are not subject to audit nor the evidentiary standards required to reach an audit conclusion. Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.