Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14

Overview

On 2 October 2014 a qualified audit opinion was issued on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 (AFR) on the basis that we do not agree with the accounting policy used to assess the level of economic obsolescence in schools.

The state has determined that seven out of every 10 Victorian schools are partly economically obsolete. It has therefore written down $1.58 billion of taxpayers' investments in those schools buildings as at 30 June 2014. However, those schools are continuing to deliver educational outcomes for the citizens of Victoria and had recently received significant investments of taxpayer funds through Commonwealth and state government funding programs. Further, in our review of the practices applied across other Australian jurisdictions we found that Victoria is alone in its approach to this matter.

The state's decision to write down those schools it deemed partly obsolete significantly reduces certain state funding for the renewal and replacement of those schools.

Overall, except for the effect of the audit qualification matters set out in our audit opinion and discussed in our report on the AFR, the Parliament and the public can have confidence that the AFR is reliable.

Auditor-General's comments

John Doyle Auditor-General |

Audit team Anna Higgs and Simone Bohan—Engagement Leaders Timothy Maxfield—Team Leader Kevin Chan and Jenny Tien—Audit Seniors Ryan Ackland, Jessica Cross, Thamali Jayasekera, Laurence McGlade, Amit Patkar and Jie Yang—Team Members Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Craig Burke |

The Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 (AFR) is the key accountability document for informing Parliament and the citizens of Victoria about the financial transactions and financial position of the state.

The AFR discloses that the state's 2013–14 net result from transactions was a surplus of $856.6 million, having reported a deficit for the previous three years. The surplus included unbudgeted Commonwealth grants of $1.16 billion.

The 2013–14 comprehensive result for the state was a surplus of $7.5 billion. The surplus was largely a result of increases in the value of the state's properties, specifically in the housing and health sectors.

I issued a qualified audit opinion on the AFR as I do not agree with the state's decision to write down $1.58 billion of taxpayers' investments in schools buildings. The state did this write down on the basis that it believed that seven out of every 10 Victorian schools are partly economically obsolete. However those schools are continuing to deliver educational outcomes for the citizens of Victoria. Further, in our review of the practices applied across other Australian jurisdictions we found that Victoria is alone in its approach to this matter.

It is of concern that the state has written down schools that had recently received significant investments of taxpayer funds through Commonwealth and state government funding programs. This includes some schools in current capital works programs and new schools in growth areas under public private partnership arrangements (PPP). Importantly the state is contractually obligated to fund the full operating, construction and financing costs of those PPP schools over a 25-year period, despite having now determined that they are partly obsolete.

It is also concerning that the state was unable to provide sufficient appropriate evidence to fully support its key school valuation assumptions and judgements.

The state's decision to write down schools it deemed partly obsolete also significantly reduces certain state funding for the renewal and replacement of schools.

Parliament and the citizens of Victoria can nevertheless have confidence in the reliability of the AFR, except for the effect of the audit qualifications described in this report.

John Doyle

Auditor-General

October 2014

Audit Summary

At 30 June 2014 the State of Victoria controlled net assets of $131 093 million and during 2013–14 collected revenue of $60 346 million. Public accountability for the collection, spending and management of the state's resources is fundamental to good government. In Victoria the legislative framework requires the government to report on the state's finances, and the Auditor-General to audit that report.

The Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 (AFR) is the key accountability document for informing Parliament and the citizens of Victoria about the financial transactions and financial position of the state for the past year. It is prepared by consolidating the financial statements of 279 state-controlled entities, and should conform with Australian Accounting Standards, and in the manner and form as determined by the Treasurer of Victoria, pursuant to the Financial Management Act 1994.

We audited the AFR and provided the opinion that—except for the effects of the following matters—the 2013–14 financial statements fairly presented the transactions and balances of the state. Our audit opinion, which was qualified, concluded that the state:

- has an accounting policy for measuring the fair value of school buildings, specifically including an economic obsolescence adjustment, that is not appropriate as it does not result in financial information that is relevant and reliable

- made an assessment of the economic obsolescence of school buildings, resulting in a significant write down of taxpayer investments in school buildings which are continuing to deliver educational outcomes, and which will result in significantly less funding for renewal of school buildings

- has not complied with AASB 127 Consolidated and Separate Financial Statements, as it has not prepared the financial report using a uniform accounting policy for measuring economic obsolescence adjustments to the fair value of all public sector non-financial physical assets, including school buildings

- was unable to provide sufficient appropriate audit evidence to fully support the appropriateness of some of its key valuation assumptions and judgements that it has used to adjust the fair value of school buildings due to economic obsolescence

- has not fully substantiated that the total economic obsolescence adjustment of $1.58 billion to the carrying value of school buildings at 30 June 2014 is fairly presented

- reclassified the total prior period's school building impairment of $2.15 billion as a fair value adjustment in the financial statements which means the comparative figures are not presented fairly in accordance with AASB 108 Accounting Policies, Changes in Accounting Estimates and Errors, which requires the state to correct material prior period errors retrospectively by restating the comparative amounts

- made inappropriate comments in the Certification by the Department of Treasury and Finance that the underlying principle of adjusting for obsolescence has remained unchanged since 2005—however, the application of economic obsolescence under AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement in the current period and impairment under AASB 136 Impairment of Assets in prior periods, are different accounting concepts that have different recognition and measurement requirements.

Conclusion

We issued a qualified audit opinion on the state's 2013–14 AFR. Parliament and the citizens of Victoria can have confidence in the reliability of the AFR, except for those audit qualifications which concern the $1.58 billion economic obsolescence adjustment to the carrying value of school buildings at 30 June 2014, and the reclassification of the prior period's school building impairment of $2.15 billion as a fair value adjustment.

The state reported a positive comprehensive result for 2013–14, reflecting positive movements in financial assets and liabilities, and positive movements in the value of non-financial assets in the housing and health sectors.

Findings

Financial performance

The state's financial statements report at two levels:

- the State of Victoria as a whole, which consolidates the results of all 279 state-controlled entities

- the general government sector (GGS) which is a subset of the state's controlled entities comprising a consolidation of the results of the 195 state-controlled entities which provide services free of charge or at prices significantly below their cost of production.

There are two key measures of financial performance and sustainability in the financial statements, the 'net result from transactions' and the 'comprehensive result'. The net result from transactions is revenue less expenditure that can be directly attributed to government policy. The comprehensive result includes other economic flows that represent changes in the value of assets and liabilities due to market remeasurements.

The state's net result from transactions was a surplus, after having reported a deficit for the previous three years. The surplus of $856.6 million for 2013–14 is a significant turnaround from the previous year, and includes unbudgeted Commonwealth grants of $1.16 billion.

The comprehensive result for the State of Victoria for 2013–14 was a surplus of $7 460.7 million. The surplus was largely a result of gains generated on the revaluation of non-financial assets, specifically in the housing and health sectors.

For the GGS, the government measures its performance and sets fiscal targets on the net result from transactions, rather than on the comprehensive result. The government's fiscal target is to achieve a net surplus from transactions of at least $100 million each financial year, consistent with net debt and infrastructure parameters. The net surplus from transactions for the GGS in 2013–14 was $1 976.2 million, well above the $100 million target.

Dividends

In 2013–14, the GGS received dividends of $220 million from state-controlled entities, and reported a net surplus from transactions of $1 976.2 million. In 2012–13 the GGS received substantially more dividends from state-controlled entities ($1 161 million), and in the 2012–13 AFR reported a net surplus from transactions of $316.4 million. The calling of dividends in 2012–13 had a significant impact on the GGS achieving its fiscal target of at least $100 million each financial year, consistent with net debt and infrastructure parameters. In 2013–14, when there was little risk of not achieving this target, fewer dividends were called.

Liquidity

The state's central treasury, Treasury Corporation of Victoria, is responsible for ensuring that the state's liquidity requirements are met at all times.

An analysis of liquidity at the state and GGS levels indicates that some entities do not have enough cash and other liquid short-term assets to settle short-term obligations. The liquidity ratio, which compares current assets with current liabilities, has improved over the last five financial years, however, it still remains below one. If entities are unable to pay debts they may call on the state to inject funds or to provide a letter of support—a letter of support is provided by the state or a state entity to an individual agency to confirm that financial assistance is available, and to enable management to prepare financial statements on a going concern basis. Liquidity is one factor when assessing going concern of an entity, and determining whether a letter of support is required. In 2013–14, 38 entities, or 14 per cent of all state-controlled entities, received a letter of support.

Borrowings

The state's borrowings increased by $3 840.4 million or 8.1 per cent in 2013–14. At the same time, gross state product increased by a smaller percentage resulting in the state having a reduced capacity to service borrowings.

As the state's debt increases, so does the interest expense incurred to service the debt. This reduces the funds available for public services, and the agility of the state to respond to revenue changes and unforeseen expenditure.

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

We issued a qualified audit opinion on the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development's (DEECD) 2013–14 financial report. The audit qualifications concerned the $1.58 billion economic obsolescence adjustment to the carrying value of school buildings at 30 June 2014, and the reclassification of the prior period's school building impairment of $2.15 billion as a fair value adjustment. These audit qualifications underpin the equivalent audit qualifications issued in respect of the AFR. In November 2013, Parliament was alerted to our concerns about DEECD's approach to impairing the value of school buildings in our Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits report.

That report highlighted that since 2006, DEECD had written down the value of school buildings as it considered that schools with more space than they were entitled to, were impaired. By 30 June 2013, DEECD had written down the carrying values of its school buildings by a total of $2.15 billion.

We nevertheless determined to issue an unmodified audit opinion on DEECD's 30 June 2013 financial statements on 11 September 2013 having received a commitment from DEECD that this issue would be resolved by the end of the 2013 calendar year and that it was appropriate to alert Parliament to this significant issue.

Notwithstanding the grace period provided to DEECD to resolve this matter, it had not been satisfactorily resolved for the 30 June 2014 financial statements, leading to the audit qualifications set out in this report.

DEECD's accounting policy for economic obsolescence results in a significant write down of taxpayer investments in school buildings which are continuing to deliver educational outcomes. This write down includes recent investments in school buildings funded from the Victorian Schools Plan (2007–08 to 2012–13) and the Commonwealth's Building the Education Revolution program (2007–08 to 2012–13).

Further, we note that some schools deemed to be partially economically obsolete by DEECD include new schools in growth areas under public private partnership arrangements or included in current capital works programs. In our review of equivalent departments across Australian jurisdictions we found that Victoria is the only state that makes an adjustment for economic obsolescence solely based on student enrolment data.

In addition to the qualified audit opinion, we found DEECD's 2013–14 financial statements required considerably greater audit scrutiny than in previous years as a direct result of our concerns related to management judgements on previous impairment estimates for school buildings, and the inability of DEECD to resolve technical accounting issues in a timely manner.

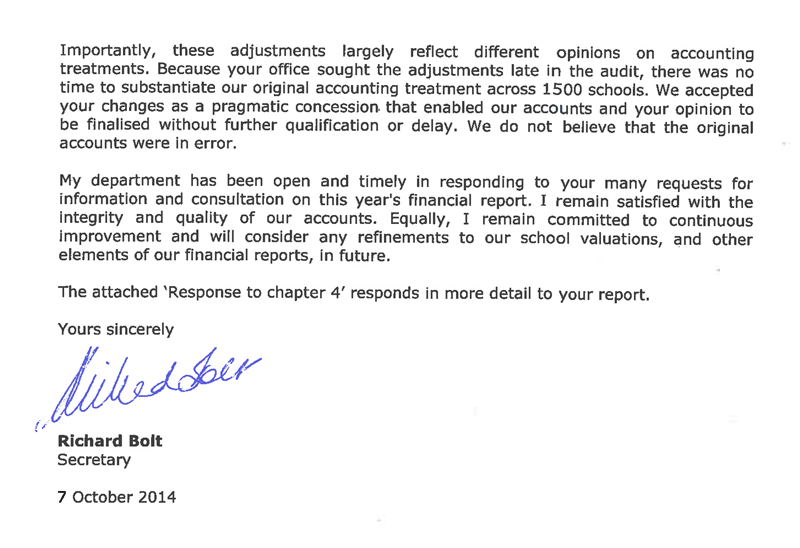

Financial report preparation by DEECD for 2013–14 was also inadequate. We formed this view based on the total number and quantum of adjustments and errors we identified during our audit of the draft financial statements. We requested 15 adjustments to the draft financial statements totalling some $850 million.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance develops an appropriate and consistent accounting policy for assessing economic obsolescence of public sector assets that sets out definition, recognition and measurement requirements, and provides guidance on how public sector agencies should apply the economic obsolescence policy. This should be consistent with the requirements of Australian Accounting Standards.

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance works with material entities to improve the timeliness of financial statement preparation.

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development maps the requirements of all applicable Australian Accounting Standards to their underlying systems and records, and identifies any gaps or limitations that prevent the preparation of a complete and accurate set of compliant financial statements.

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development critically reviews its financial report preparation processes to identify areas for improvement and implements all improvements before the 30 June 2015 reporting cycle.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16A and 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, a copy of this report, or relevant extracts from the report, was provided to the Treasurer and all relevant agencies with a request for submissions or comments.

The views of the Treasurer and agencies have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16A and 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix F.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

The Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA) governs the financial administration, accountability and reporting of the Victorian public sector. It requires the annual preparation of a consolidated financial report of the state, known as the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria (AFR).

The AFR acquits the government's stewardship of the state's finances to Parliament. It is incorporated into a narrative report, the Financial Report of the State of Victoria, which analyses the government's expenses, revenue, assets and liabilities.

The Treasurer, pursuant to the FMA, is responsible for determining the manner and form of the AFR and also preparing the AFR in accordance with applicable Australian Accounting Standards. In 2009 the Treasurer approved a standing delegation authorising specified officers of the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) to sign the certification of the AFR. This certification attests, in the opinion of the specified DTF officers, to the fair presentation of the AFR on behalf of the Treasurer.

1.2 Scope of the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria

1.2.1 Entities included

The AFR provides the combined financial results of all state-controlled entities, that is, entities where the state has the power to govern their financial and operating policies to obtain benefits from their activities. Controlled entities include portfolio departments and state-owned enterprises.

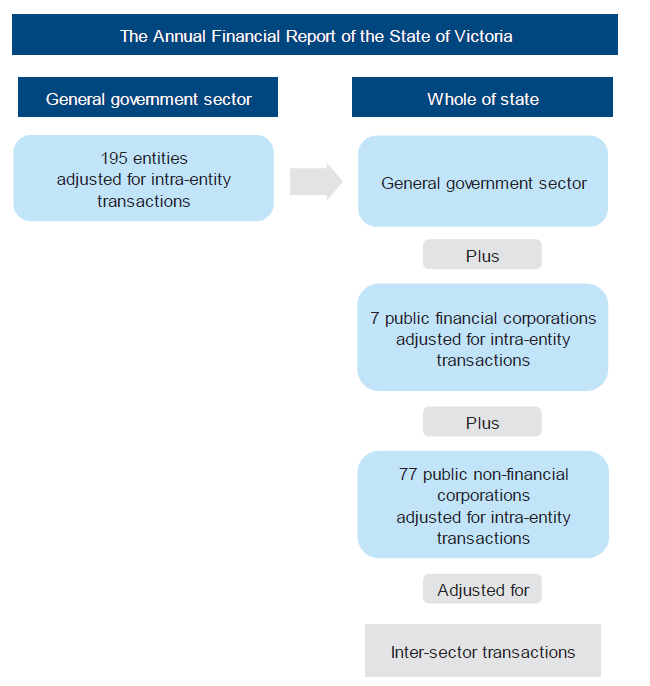

Entities controlled by the state are classified into three sectors. Figure 1A describes each sector. A list of all consolidated entities is contained in Note 42 of the AFR.

Figure 1A

Sectors of government and explanation of their controlled entities

Sector |

Explanation |

|---|---|

General government sector |

195 entities which provide services free of charge or at prices significantly below their production cost. Examples include government departments, public hospitals and technical and further education institutes. |

Public financial corporations |

Seven entities that borrow centrally, accept deposits and acquire financial assets. Examples include the Treasury Corporation of Victoria and Victorian WorkCover Authority. |

Public non-financial corporations |

77 entities whose primary purpose is to provide goods and/or services in a competitive market and who are non-regulatory and non‑financial in nature. Entities include water corporations, alpine resort management boards and the Victorian Rail Track Corporation. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

DTF produces the AFR. The controlled entities transmit their financial data through the State Resource Information Management System (SRIMS) to DTF and transactions between entities are eliminated to avoid double counting.

Of the controlled public sector entities, 48 were deemed 'material' entities for 2013–14 (49 in 2012–13). A public sector entity is classified as material when its individual financial operations are significant in the reporting of the consolidated finances of the state. Collectively, material entities accounted for more than 90 per cent of the state's assets, liabilities, revenue and expenditure. The 48 material entities for 2013–14 are listed in Appendix B.

1.2.2 Entities excluded

Local government entities, universities, denominational hospitals and superannuation funds are not state-controlled entities and therefore are not included in the AFR. Figure 1B details the rationale for their exclusion, consistent with Australian Accounting Standards.

Figure 1B

Entities not controlled by the state and the rationale for exclusion

Entity |

Rationale |

|---|---|

Local government |

Local government is a separate tier of government with councils elected by, and accountable to, their ratepayers. |

Universities |

Universities are primarily funded by the Commonwealth and the state directly appoints only a minority of university council members. |

Denominational hospitals |

Denominational hospitals are private providers of public health services and have their own governance arrangements. |

State superannuation funds |

The net assets of state superannuation funds are the property of the members. However, any shortfall in the net assets related to certain defined benefit scheme entitlements of the state's superannuation funds are an obligation of the state and are reported as a liability in the AFR. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3 Structure of the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria

1.3.1 Levels of reporting

The AFR presents information on two aspects of the state's finances:

- state of Victoria level—consolidates all three sectors set out in Figure 1A

- general government sector level—provides consolidated information on the 195 entities.

Figure 1C shows the entities covered by each of these aspects and the items that are eliminated to avoid double counting, being intra-entity and inter-sector transactions, in the AFR.

Figure 1C

Coverage of the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.3.2 Financial performance

The consolidated comprehensive operating statement in the AFR contains state revenue, expenses and other economic flows. It includes two key measures of financial performance and sustainability—the 'net result from transactions' and the 'comprehensive result'.

The net result from transactions is revenue less expenditure that can be directly attributed to government policy.

The comprehensive result, however, includes other economic flows that represent changes in the value of assets and liabilities due to market remeasurements. It includes actuarial gains and losses that primarily reflect the valuation movement in the state's unfunded superannuation liability.

1.3.3 Financial position

The consolidated balance sheet in the AFR presents the state's assets and liabilities. The notes to the AFR contain information about other financial commitments and contingent assets and liabilities not in the consolidated balance sheet. Combined, the balance sheet and relevant notes provide the state's financial position.

1.4 Audit requirements

Section 9A of the Audit Act 1994 requires the Auditor-General to provide an audit opinion on the AFR. To form that opinion, a financial audit is conducted in accordance with Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

Section 16A of the Audit Act 1994 requires the Auditor-General to report to Parliament on the AFR.

The Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 is the third of 10 reports to be presented to Parliament during 2014–15 covering the results of financial audits. Appendix A outlines the reports and the intended time frames for tabling.

1.5 Audit conduct

The audit was conducted in accordance with Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

The cost of preparing this report was $140 000.

1.6 Structure of this report

This report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 reports on the results of the AFR financial statement audit.

- Part 3 provides commentary and analysis of the state's financial result.

- Part 4 provides commentary and analysis of the results of the annual financial audit of the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development.

2 Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria audit result

At a glance

Background

This Part reports on the results of the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 (AFR) financial statement audit.

Conclusion

The Auditor-General issued a qualified audit opinion on the AFR relating to the state's valuation accounting policy for school buildings at the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD). The audit qualifications related to a $1.58 billion economic obsolescence adjustment to the carrying value of school buildings at 30 June 2014, and the reclassification of the prior period's school building impairment of $2.15 billion as a fair value adjustment. Except for the matters described in the Basis for Qualified Opinion paragraphs of the Auditor-General's report, the Parliament and the public can have reasonable assurance that the AFR was reliable and prepared in accordance with the requirements of applicable Australian Accounting Standards and the manner and form of the financial statements as determined by the Treasurer pursuant to the Financial Management Act 1994.

Findings

- The Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) improved the accuracy and timeliness of the AFR in 2013–14.

- The whole-of-government reporting system issues and deficiencies reported in 2012–13 were largely addressed and longstanding financial instruments disclosure issues resolved.

- While DTF acted in 2013–14 to improve the production of the AFR, it was not well supported by material entities, most of which did not meet a key DTF milestone.

- The Certification by DTF to the AFR inappropriately includes substantial further commentary that explains the state's approach to the adjustment of the fair value of school buildings.

Recommendations

- That DTF develops an appropriate and consistent accounting policy for assessing economic obsolescence of public sector assets.

- That DTF works with material entities to improve the timeliness of financial statement preparation.

2.1 Auditor-General's opinion

The Auditor-General issued a qualified audit opinion on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 (AFR) on 2 October 2014. A copy of the Auditor‑General's audit opinion can be found in Appendix E. The qualified opinion was issued because the Auditor-General does not agree with the accounting policy of how school buildings at the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) are measured—specifically, how economic obsolescence is assessed in calculating the building's fair value. Part 4 of this report specifically comments on our audit of DEECD's 2013–14 financial statements and the basis for the audit qualification.

Under Australian Auditing Standards, when VAGO is assessing whether a misstatement in the financial report is material for the audit of public sector agencies, there are additional requirements that we need to consider. In particular, ASA 450 Evaluation of Misstatements Identified During the Audit requires us to consider whether issues such as public interest and accountability affect our assessment of whether the misstatement is material by virtue of its nature.

The misstatements in DEECD's financial statements are therefore considered qualitatively material to the AFR because:

- there is substantial Parliamentary and public interest in the discharge of DEECD's accountability for its management of schools

- the management and operation of school assets are a significant part of DEECD's role and legislative objectives

- the financial management of school assets is critical to whether the state and DEECD are acting with financial prudence

- the amounts involved are significant to the reader of the AFR in absolute terms, comprising a total economic obsolescence adjustment of $1.58 billion and a total prior period impairment of $2.15 billion

- the state has not complied with AASB 127 Consolidated and Separate Financial Statements, as it has not prepared the AFR using a uniform accounting policy for measuring economic obsolescence adjustments to the fair value of all public sector non-financial physical assets, including school buildings.

The state's accounting policy for valuing public sector non-financial physical assets, including school buildings, is summarised in note 1 to the AFR and is also set out in Financial Reporting Direction FRD 103E Non-Financial Physical Assets issued by the Minister for Finance pursuant to the Financial Management Act 1994 (FMA). Further, FRD 103E references Australian Accounting Standard AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement.

AASB 13 provides that when assessing the fair value of non-financial physical assets there should be consideration of the existence of economic obsolescence when using the cost approach. However, it does not specify how to assess economic obsolescence, particularly in a public sector context. FRD 103E does not reference this requirement of the standard or set out the state's accounting policy in this regard, and Note 1 to the AFR only references the approach taken by DEECD which is based on student enrolment data.

Consequently, the accounting policy used by public sector agencies to assess economic obsolescence is dependent upon the policies adopted by the individual agencies, and a consistent policy has not been promulgated by the state for the purposes of the AFR. Our review of the accounting policies used by material entities found that, other than DEECD, they did not reference the requirement, or specify how to assess economic obsolescence. Consequently, the accounting policy being applied by DEECD wasn't being applied by those agencies.

The DEECD accounting policy for assessing economic obsolescence is based on a consideration of student enrolment data—as set out in Part 4 of this report. However, the valuation of the state's declared road network, for example, which also uses the written down replacement cost method for setting fair value as is used for school buildings, doesn't include any adjustment for economic obsolescence based on traffic volumes. An equivalent approach to that taken for school buildings would be to use traffic volumes to assess economic obsolescence for roads, however, this is not part of the state's accounting policies.

Further, the Certification by the Department of Treasury and Finance states that the underlying principle of adjusting for obsolescence has remained unchanged since 2005. In our opinion, the application of economic obsolescence under AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement in the current period and impairment under AASB 136 Impairment of Assets in prior periods, are different accounting concepts which have different recognition and measurement requirements under their respective Australian Accounting Standards.

Except for the matters outlined in the Basis for Qualified Opinion paragraphs of the Auditor-General's report on the AFR—see Appendix E—users can have reasonable assurance that the information in the AFR is reliable, and prepared in accordance with the requirements of the Australian Accounting Standards and in the manner and form as determined by the Treasurer of Victoria pursuant to the FMA.

The opinion was included in Chapter 4 of the state's 2013–14 Financial Report, which was transmitted to Parliament on 15 October 2014.

2.1.1 Certification by the Department of Treasury and Finance

The Certification by the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) to the 2013–14 annual financial report includes substantial further commentary that explains the state's approach to the adjustment of the fair value of school buildings. In our view it is highly unusual and inappropriate for this additional commentary to be included in the certification.

The purpose of the certification is to state its opinion that the financial statements present fairly the financial transactions during the reporting period and the financial position at the end of the period in accordance with AASB 101 Presentation of Financial Statements. We are of the opinion that commentary on the fairness of specific account balances, transactions or disclosures should be included in the notes to the financial statements and not in the certification. In particular, we do not believe it is appropriate for DTF to make direct reference to the Victorian Valuer-General in its certification.

2.1.2 Material inconsistency in the Annual Financial Report

The foreword of the 2013–14 AFR contains commentary in relation to the valuation of education assets which is materially inconsistent with Note 22(f) of the financial statements. Specifically, the Department of Treasury and Finance states that the underlying principle of adjusting for obsolescence has remained unchanged since 2005. However, Note 22(f) of the financial statements states that the economic obsolescence adjustment recognised for school building assets has been reclassified from impairment under AASB 136 Impairment of Assets in prior periods to economic obsolescence under AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement in the current period. As noted previously in Section 2.1, these are different accounting concepts which have different recognition and measurement requirements under their respective Australian Accounting Standards. As a consequence of this material inconsistency, the Auditor‑General included an 'Other Matter' paragraph in his independent auditor's report on the AFR.

2.2 Quality of reporting

Except for matters relating to the qualification, the accuracy and timely production of the AFR improved in 2013–14. DTF is to be commended on the improvements made to its processes and quality control. Despite the low number of material entities meeting the AFR milestone, DTF was able to achieve more timely production than in previous years.

2.2.1 Accuracy

The accuracy of the draft AFR is measured by the frequency and number of material adjustments arising from the audit, and the number of drafts provided for audit. Ideally there should be no material adjustments required once a complete draft is provided for audit.

To prepare the 2013–14 AFR, DTF planned to provide three drafts of the financial statements for audit, with the first being on 28 August 2014. DTF achieved this time line. Although there were minor delays on some information provided for audit, this was a significant improvement on previous years, demonstrating that DTF has invested time in improving its AFR production processes.

There were less material adjustments required to the first draft compared to prior years, indicating that the quality control procedures adopted by DTF had improved. Further to that, we noted that the first draft provided was more complete than in prior years, with all significant disclosures present.

During the 2012–13 AFR we identified limitations with the State Resource Information Management System (SRIMS) in capturing some financial instruments disclosures relating to insurance agencies. It is pleasing to note that for the 2013–14 AFR, DTF has worked closely with the insurance agencies to implement the required functionality into SRIMS, and improve the accuracy of the disclosure. This was further evidenced by the high quality of the first draft received on 28 August 2014.

The increased functionality of SRIMS has also improved the accuracy of the consolidated cash flow statement. In order to comply with AASB 107 Statement of Cash Flows, and in response to previous audit recommendations, DTF formalised the process of submitting gross cash flow information through SRIMS in 2013–14. We have made additional recommendations to DTF to further improve the accuracy of cash flow information in the AFR.

2.2.2 Timeliness

The timeliness of preparation of the AFR is measured against the statutory reporting deadline established in the FMA, and against the annual production timetable set by DTF. The 2014 state election, scheduled for 29 November 2014, resulted in the length of time for the preparation and audit of the AFR being reduced, with the certification date originally set for 19 September 2014. The AFR was certified by DTF officer's, on behalf of the Treasurer, on 29 September 2014.

The qualified audit opinion on the AFR was issued on 2 October 2014, compared to 27 September 2013 in 2012–13.

The Treasurer provided the 2013–14 AFR to Parliament on 15 October 2014. This was consistent with 2012–13 (14 October 2013) and on or before the statutory reporting deadline of 15 October 2014.

Material entities

The timely preparation and audit of the AFR depends on material entities meeting the AFR preparation timetable and the early identification and resolution of significant accounting and disclosure issues.

DTF set a milestone date of 20 August 2014 for all material entity accounts to be finalised. This date was set to allow adequate time to prepare and audit the AFR.

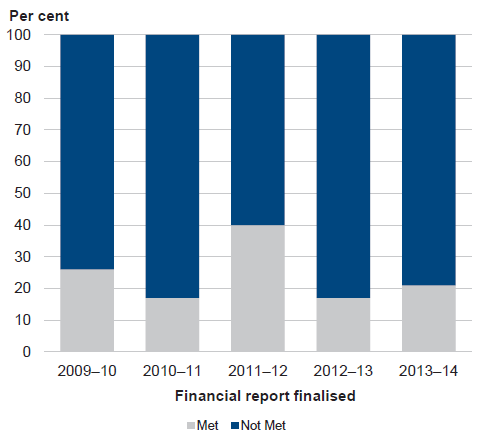

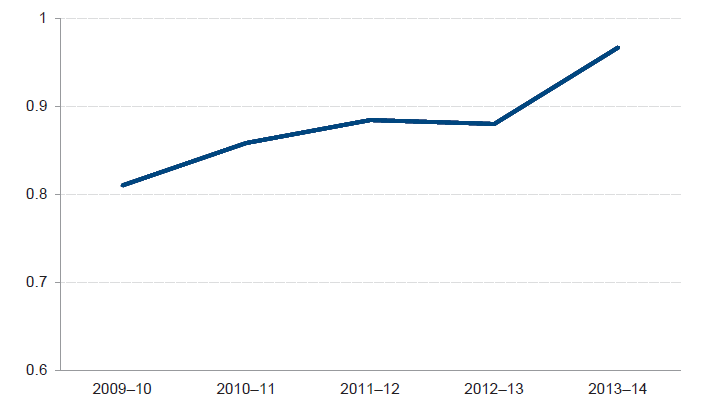

Figure 2A shows the performance of material entities in finalising their financial statements against the AFR milestone over the past five years.

Figure 2A

Timeliness – material

entities against the Department of

Treasury and Finance milestone

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

For 2013–14 only 10 of the 48 material entities (or 21 per cent) met the milestone date. The delays experienced may be partially attributed to the introduction of AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement. The purpose of the standard is to provide readers with more information about the inputs—observable and unobservable—used in calculating the fair value of assets and liabilities by splitting them into three levels. Each level has different disclosure requirements, with 'level 3' disclosures being the most onerous. Due to the nature and composition of the state's non-financial assets, a large number of material entities were required to report their non-financial assets as 'level 3', which significantly increased the disclosure requirements. This provided material entities with challenges in terms of the quantum of information required for the disclosure.

We encouraged material entities to prepare shell financial statements based on the DTF model financial report, which included the proposed disclosure requirements for AASB 13. The preparation of shell financial statements allows material entities to determine the presentation and disclosure requirements ahead of the preparation of the annual financial statements. We also recommend that material entities consider undertaking a hard-close process, which is typically done one to three months prior to year end. This process involves bringing forward some audit procedures meaning less work needs to be done by the entity and auditors at year end. The hard-close process does not suit all circumstances, however, it has been successfully used by a number of material entities in the past.

The late finalisation of material entity financial reports forced DTF to initially prepare the AFR on unaudited information provided into SRIMS. The important contribution that material entities make to the state's overall financial results and balances should serve as a driver for them to complete financial statements in a timely manner, as information cannot be verified in SRIMS until the audit of the financial statements is complete. Ideally all information in SRIMS provided by material entities would have been reviewed, and errors communicated back to the entity/DTF prior to the preparation of the AFR, however, this was not the case.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance develops an appropriate and consistent accounting policy for assessing economic obsolescence of public sector assets that sets out definition, recognition and measurement requirements, and provides guidance on how public sector agencies should apply the economic obsolescence policy. This should be consistent with the requirements of Australian Accounting Standards.

- That the Department of Treasury and Finance works with material entities to improve the timeliness of financial statement preparation.

3 The state's financial result

At a glance

Background

This Part analyses and comments on the state's financial performance and position for 2013–14 by interpreting the results reported to Parliament in the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 (AFR).

Conclusion

A positive net result from transactions was achieved for the state and general government sector. An analysis of the state's liquidity indicates that entities across the state do not have enough cash and other liquid short-term assets to settle short-term obligations.

Findings

- The state's net result from transactions was a surplus of $856.6 million, compared to deficits reported in the three prior years. A key contributor to the surplus was the receipt of unbudgeted Commonwealth funding of $1.16 billion relating to East West Link.

- Employee expenses increased at a rate of 1.3 per cent in 2013–14 which is less than the consumer price index (CPI) of 2.5 per cent.

- The state's comprehensive result was a surplus of $7 460.7 million, largely as a result of revaluation gains on non-financial assets—mainly land and buildings—in the housing and health sectors.

- Only $220 million of dividends were received from state-controlled entities in 2013–14 compared to $1 161 million in 2012–13.

- The state and general government sector liquidity ratio is less than one indicating that some state-controlled entities do not have enough cash and other liquid short-term assets to settle short-term obligations.

- The self-financing ratio indicates that the state is not generating sufficient cash from its operations to fund new assets and asset renewal.

- Borrowings have increased at a rate faster than the growth in gross state product, reducing the state's capacity to service its debt.

3.1 Introduction

This Part analyses and comments on the state's 2013–14 financial performance and position by interpreting the results reported to Parliament in the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2013–14 (AFR). It discusses significant transactions reported in the AFR, and the state's net result from transactions, overall comprehensive result, short-term liquidity, financing of infrastructure, and debt sustainability.

3.2 Overall conclusion

The state achieved a net surplus from transactions—which measures the revenue and expenditure attributed to government policy. The comprehensive result for the state was also positive, reflecting net gains in financial instruments within other economic flows included in the net result and a significant gain in the asset revaluation surplus.

3.3 Financial performance

3.3.1 The state's net result from transactions

The state's net result from transactions measures the revenue and expenses attributed to government policy in the general government sector (GGS), public non-financial corporations and public financial corporations. The comprehensive result includes changes in the value of assets and liabilities due to market fair value remeasurements. For example any gains or losses on financial instruments, which form a significant part of public financial corporations operations, are reflected in the comprehensive result and are not included in the net result from transactions.

The state's net result from transactions for 2013–14 was a surplus of $856.6 million ($3 119.8 million deficit in 2012–13) compared to a budgeted deficit of $1 490.7 million.

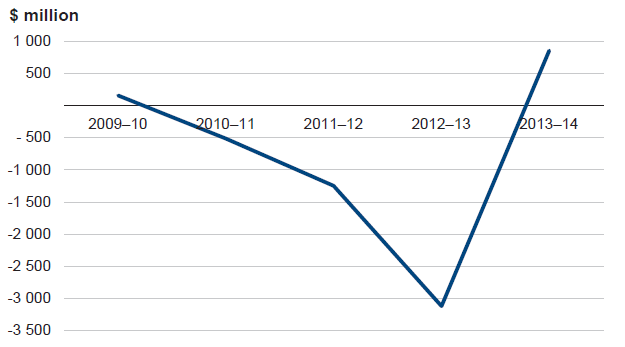

Figure 3A shows that the state's net result from transactions improved in 2013–14 after three consecutive years of decline. The improvement was caused by revenue increasing by 11.3 per cent compared to expenditure at 3.8 per cent.

Figure 3A

Net result from transactions, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

In 2013–14, revenue increased by $6 143.3 million compared to a budgeted increase of $3 444.3 million. The increase in revenue from the prior year was primarily driven by a:

- $3 228.7 million (14.8 per cent) increase in Commonwealth funding due to an increase in the national goods and services tax (GST) pool, and other specific purpose grants for the delivery of the East West Link and projects under the National Health Reform

- $1 336.4 million (10.4 per cent) increase in the sale of goods and services reflecting an increase in volume of water sold, as well as higher water and sewerage charges

- $891.4 million (27.2 per cent) increase in land transfer duties reflecting improved property markets.

The state outperformed the original budgeted revenue predominately due to higher than anticipated Commonwealth grants revenue, and additional land transfer duties and dividends received by the public financial corporations from external organisations.

The increase in revenue was partially offset by an increase in expenditure of $2 166.9 million compared to a budgeted increase of $1 815.2 million. The increase in expenditure from the prior year was primarily driven by a:

- $1 770.9 million (7.6 per cent) increase in other operating expenses predominately due to increased purchases of services in the health sector, and a payment of $540 million relating to a legal settlement with Tatts

- $415.8 million (16.4 per cent) increase in interest expense primarily due to a full year of interest charged on the desalination plant and Peninsula Link finance leases. There was also an increase due to additional borrowings required to fund the state's infrastructure investment program.

Total expenses were within 1 per cent of the original State Budget.

Employee expenses

Employee expenses accounted for 32 per cent of total expenses from transactions in 2013–14. In the Auditor-General's Report on the Annual Financial Report of the State of Victoria, 2010–11, we reported the need for the state government to closely monitor and tightly control expenditure with reference to employee entitlements. Over the five‑year period from 2006–07 to 2010–11, employee expenses had grown at a rate above the consumer price index (CPI).

A number of initiatives have been implemented by government to manage employee related expenses. For example, in December 2011 the state government announced its Sustainable Government Initiative (SGI). The SGI included a 3 600 reduction in the public service workforce announced as part of the 2011–12 Victorian Budget Update. Additional workforce reductions of around 600 positions were announced as part of the Victorian Budget 2012–13. The workforce reductions were completed by 31 December 2013 through natural attrition, a freeze on recruitment, the lapsing of fixed-term contracts and voluntary departure packages (VDP).

Figure 3B shows the percentage growth in employee expenses, before and after implementing the SGI, compared to CPI for the same period.

Figure 3B

Comparison of increases in employee expenses and CPI, 2006–07 to 2013–14

|

Financial year |

Employee expenses increase (%) |

CPI (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

2006–07 |

6.0 |

2.0 |

|

2007–08 |

7.2 |

4.4 |

|

2008–09 |

8.0 |

1.2 |

|

2009–10 |

7.9 |

3.1 |

|

2010–11 |

6.4 |

4.6 |

|

2011–12 |

4.6 |

2.3 |

|

2012–13 |

4.1 |

2.2 |

|

2013–14 |

1.3 |

2.5 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office and Australian Bureau of Statistics.

Employee expenses increased by 1.3 per cent ($242.7 million) in 2013–14. The percentage growth in employee expenses since implementing the SGI has been significantly lower than the percentage growth over the preceding five financial years. Although the SGI was not intended to apply to frontline service delivery roles, government must make sure that the quality and quantity of public services is not compromised by resource constraints. It is too early to reliably determine if reduced employee numbers has impacted service delivery and/or the engagement of contractors and consultants. This will be considered for inclusion in a later report to Parliament.

3.3.2 The general government sector's net result from transactions

For the GGS, the government measures its performance and sets fiscal targets on the net result from transactions, rather than on the comprehensive result. The government's fiscal target is to achieve a net surplus from transactions of at least $100 million each financial year, consistent with its infrastructure and net debt parameters. The net surplus from transactions for 2013–14 was $1 976.2 million compared to a budgeted surplus of $224.5 million. The improved result is predominately due to higher than anticipated Commonwealth grants revenue and additional land transfer duties.

Dividends

The government has a policy underpinning the payment of dividends. This policy requires the government's budget position to be a consideration when determining an entity's dividend payment. Actual dividend payments are negotiated with the responsible board and portfolio minister, and are generally paid twice a year as follows:

- an interim dividend paid in April based on half-year financial results

- a final dividend paid in October based on annual financial results.

In 2012–13, the GGS received dividends of $1 161 million from state-controlled entities that operate outside the GGS, and the 2012–13 AFR reported a net surplus from transactions of $316.4 million. If dividends were not received in that year, the government's fiscal target of a net surplus from transactions of at least $100 million would not have been achieved. It should be noted that the 2012–13 GGS net result from transactions has subsequently been restated in the 2013–14 AFR to account for the requirements of the revised AASB 119 Employee Benefits as a change in accounting policy in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards.

In 2013–14, the GGS received dividends of $220 million from state-controlled entities that operate outside the GGS, and reported a net surplus from transactions of $1 976.2 million. The decrease of $941 million in dividends compared to 2012–13 is partially driven by decreased financial results in the state-controlled entities that are required to pay dividends. The decrease is also a result of special dividends not being required from the State Electricity Commission of Victoria in 2013–14 ($413.8 million in 2012–13).

Notwithstanding the government's dividend policy requiring that the Department of Treasury and Finance (DTF) consider a number of financial indicators when determining an appropriate dividend payout ratio, it appears that a sufficiently robust assessment of an entity's ability to pay dividends may not have been completed.

In our report Water Entities: Results of the 2011–12 Audits, tabled in November 2012, we observed that each of the four metropolitan water entities had borrowed to facilitate the payment of dividends and fund infrastructure programs in that year. This trend continued in 2012–13 where three of the four metropolitan water entities were required to borrow.

We further commented that the metropolitan water entities ability to repay debt from operating profits was declining. In particular, City West Water and Melbourne Water did not have the capacity at 30 June 2012 and 30 June 2013 to cover annual debt repayments from operating profits.

In 2013–14, borrowings at City West Water, South East Water and Yarra Valley Water increased collectively by $333.8 million. The financial position at 30 June 2014, and the ability to remain financially sustainable, of all 19 water entities will be assessed in our report Water Entities: Results of the 2013–14 Audits, scheduled for tabling in February 2015.

3.3.3 The state's comprehensive result

The state's 2013–14 comprehensive result was a surplus of $7 460.7 million (surplus of $10 774.5 million in 2012–13) compared to a budgeted deficit of $5 997.2 million. The variance against budget is mainly due to a $5 211.5 million revaluation gain on non-financial assets in the housing and health sectors which was not budgeted for, and higher than anticipated revenue as explained in our commentary on the net result from transactions.

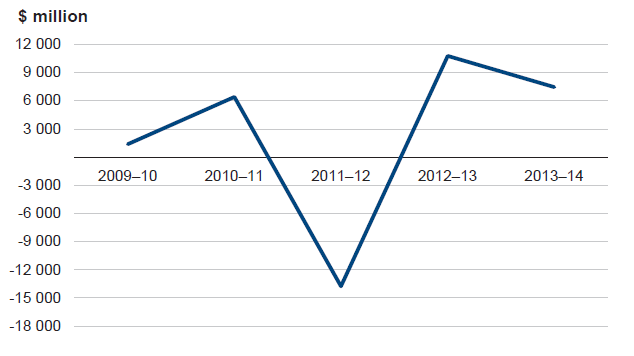

Figure 3C shows there is no discernable trend in the state's net result for the past five financial years.

Figure 3C

Comprehensive result, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The $856.6 million net surplus from transactions forms part of the 2013–14 comprehensive result reported in the AFR. The $6 604.1 million difference, known as other economic flows, is largely due to:

- a net gain of $1 159 million on financial instruments at fair value which reflects the performance of public financial corporations in 2013–14, in particular, the Treasury Corporation of Victoria (TCV) and Victorian WorkCover Authority.

- a $5 211.5 million revaluation gain on non-financial assets—mainly land and buildings—in the housing and health sectors.

These gains were partly offset by $195.7 million in fines in the justice sector being written off during the year.

3.4 Financial position

3.4.1 Significant transactions that impacted the state's financial position

The consolidated balance sheet contains all state assets and liabilities. Some of the key movements in the balance sheet are reflected through the revaluation of land and buildings in the health and housing sectors and an increase in borrowings. Other significant transactions that impacted the state's financial position are summarised below.

Fair value of school buildings

As set out in Part 4 of this report, the state has written down the carrying value of school buildings by a total of $1.58 billion as at 30 June 2014 as an economic obsolescence adjustment. Please refer to Part 4 for additional details.

Deconsolidation of dual-sector universities

Victoria's tertiary education system is comprised of eight universities and 12 technical and further education institutes (TAFE). Four universities currently deliver higher education courses, and operate a separate TAFE division that provides vocational education and training. These universities are known as dual-sector universities.

The universities currently operating as dual-sector universities in Victoria are:

- Federation University Australia

- Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology

- Swinburne University of Technology

- Victoria University.

Universities are not controlled, for financial reporting purposes, by the state and therefore are not consolidated into the AFR. However, until 31 December 2013, the dual sector universities were required to prepare separate financial information relating to their TAFE activities for consolidation into the GGS.

The enactment of the Education and Training Reform Amendment (Dual Sector Universities) Act 2013 from 1 January 2014 has resulted in major changes to the compliance and reporting requirements of these entities. The TAFE activities and balances are now reported solely in the four dual-sector universities financial statements, and are not required to be consolidated into the GGS. In addition, separate disclosures of TAFE activities in the dual-sector universities financial reports and audited performance statements are no longer necessary.

The legislative amendments have resulted in the deconsolidation of the financial information of the four dual-sector universities TAFE divisions from the AFR from 1 January 2014.

Consequently, the states net assets have been reduced by $847.6 million and $368.8 million of the asset revaluation reserve relating to these assets has transferred into accumulated funds. The AFR includes the financial transactions of the TAFE component of the dual-sector universities to 31 December 2013.

Sale of Rural Finance Corporation's business

The Rural Finance Corporation of Victoria (RFC) is a specialist rural lender that offers a range of financial packages to fund the acquisition, expansion and development of farm businesses, banking restructures, working capital, off-farm investments, plant and equipment, and housing.

During May 2014, the Treasurer signed a Business Sale Agreement (BSA) to sell the majority of the net assets of RFC and a licence to use RFC trade-marks to the Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited for an expected $1 780.8 million, or $85.0 million above the agreed carrying value of the acquired net assets. The net assets sold included the majority of the loan debtors and property, plant and equipment, less the employee provisions for staff moving to the Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited. RFC's borrowings associated with the loan debtors were retained and were discharged using the sale proceeds.

On 1 July 2014, the sale proceeded and the net assets sold were determined to have a final value of $1 675.3 million, being $20.5 million less than the amount set out in the BSA. This was due to the fact that loan debtors and property, plant and equipment values had changed since the original BSA was signed. The final sale proceeds on 1 July 2014 were therefore $1 760.3 million, including the $85.0 million. Certain former RFC staff members also transferred to the Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited at that time.

The proceeds from Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited were used to discharge RFC's borrowings from TCV totalling $1 310.5 million on 1 July 2014. This amount represents the full repayment of all TCV borrowings of $1 292.7 million, accrued interest of $6.0 million and break costs for the early repayment of borrowings of $11.8 million. In addition, both RFC and the state will have incurred other transaction costs as part of the sale process.

Following the settlement under the BSA, RFC will continue to exist, however, the ongoing activities are yet to be fully determined. It is expected that ongoing activities will include responsibility for certain government grant schemes, currently outsourced to Bendigo and Adelaide Bank Limited.

Under the agreement, the Bendigo and Adelaide Bank can make claims against RFC within 15 months of the completion date, for breaches of warranty. At the date of preparation of this report, RFC advised that it was not aware of any such claims having been made.

The sale has been reported in the 2013–14 AFR as an event that occurred subsequent to 30 June 2014. The impact on the financial position of the state will therefore be recognised and reported in the 2014–15 AFR.

3.4.2 Liquidity

An indicator of the state's short-term financial health is its ability to pay existing short‑term financial obligations as they become due. This can be measured by comparing the state's current assets with current liabilities. A ratio of more than one means there are more cash and liquid assets than short-term liabilities. A stronger ratio indicates a better ability to meet ongoing and unexpected costs.

The AFR discloses that the state is exposed to liquidity risk mainly through maturity of its borrowings and the requirement to fund cash deficits. The state's central treasury, TCV, is responsible for ensuring that the state's liquidity requirements are met at all times. The state's liquidity ratio disclosed in the AFR was 1.43:1. This measures TCV's liquid assets—after discounting to reflect potential loss of value in the event of a quick sale—versus 12 months of debt and interest obligations. It is not a complete indication of the state's ability to pay all existing short-term financial obligations as they become due.

The state currently holds a triple-A credit rating as provided by Standard and Poors and Moody's. The purpose of this rating is to assess credit risks, which evaluates the ability and willingness to meet financial obligations in full and on time. On the other hand, the liquidity ratio focuses on short term obligations, rather than financial obligations as a whole, and consequently provides a different perspective.

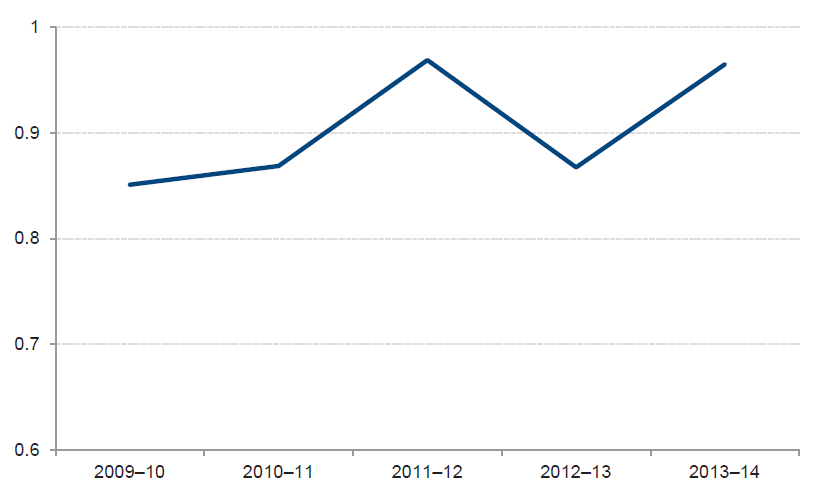

Figure 3D shows the state's ratio of current assets over current liabilities over the past five years.

Figure 3D

Liquidity ratio, State of Victoria, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Note: The state's current assets include land inventories while the state's current liabilities include unearned income. Further, the state's current liabilities include some longer-term employee entitlements, and associated on-costs, that have been appropriately disclosed as current liabilities in the financial statements in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards. The AFR does not separately disclose those longer-term liabilities classified as current liabilities.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 3D illustrates the sum of current assets compared to the sum of short-term liabilities for all state-controlled entities from the general government, public non‑financial and public financial sectors, less inter-sector transactions. It shows that the state had a liquidity ratio of less than one between 2009–10 to 2013–14, meaning that there are entities across the state that do not have enough cash and other liquid short-term assets to settle short-term obligations. More analysis of individual entities' liquidity is performed in our sector based reports, which are listed in Appendix A.

If entities are unable to pay debts they may call on the state to inject funds or to provide a letter of support. A letter of support is provided by the state or a state entity to an individual agency to confirm that financial assistance is available, and to enable management to prepare financial statements on a going concern basis. Liquidity is one factor when assessing going concern of an entity, and determining if a letter of support is required. In 2013–14, 38 agencies, or 14 per cent, of all state-controlled entities received a letter of support.

Figure 3E shows the GGS's ratio of current assets over current liabilities over the past five years.

Figure 3E

Liquidity ratio, General Government Sector, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Note: The GGS's current assets include land inventories while the GGS's current liabilities include unearned income. Further, the GGS's current liabilities include some longer-term employee entitlements, and associated on-costs, that have been appropriately disclosed as current liabilities in the financial statements in accordance with Australian Accounting Standards. The AFR does not separately disclose those longer-term liabilities classified as current liabilities.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 3E shows a liquidity ratio of less than one between 2009–10 to 2013–14 for the GGS. The cash of many GGS entities is managed centrally by DTF—through TCV. These entities have responsibilities within the bounds of set funding arrangements but do not have direct control over managing their liquidity, and consequently it is managed by DTF—through TCV. The ratio indicates that in the unlikely event that all short-term obligations were required to be paid at once, the GGS entities would not have sufficient cash and liquid assets at balance date to meet these payments. Consequently, some longer-term investments would need to be liquidated or short‑term borrowing raised, which may involve the payment of penalties or sacrificing interest revenue. The AFR highlights that TCV introduced an enhanced liquidity policy in 2012 to assist the state to manage its liquidity position, and that this includes liquidity crisis management plans to respond to any such crisis.

3.4.3 Self-financing

The state's infrastructure assets include roads, transport networks, ports, and water infrastructure. In 2013–14, the value of these assets increased by 3.7 per cent, from $52 351.8 million at 30 June 2013 to $54 314.0 million at 30 June 2014.

Maintaining existing infrastructure and providing new infrastructure to achieve the state's social, economic and environmental objectives is a significant challenge for government. The state funds infrastructure with its own cash reserves, which includes Commonwealth Government contributions, and borrowings. The state is substantially reliant on Commonwealth Government contributions, which accounted for 41.5 per cent of total revenue in 2013–14. Approximately 46 per cent, or $11.5 billion, of Commonwealth Government contributions relate to the state's share of the GST pool, the remainder relates to grants for specific purposes such as the National Health Reform, East West Link and Regional Rail Link. The state does not have direct control over the level of specific purpose contributions it receives each year from the Commonwealth Government.

An indicator of the state's financial performance is its ability to finance planned investments from its own cash resources, which includes Commonwealth Government contributions. In the long term, the state should generate sufficient funds from operations to maintain existing, and fund new, infrastructure. The self-financing indicator measures the net operating cash flows available to fund infrastructure, and is reported as a percentage of revenue. The indicator incorporates both own-sourced revenue and Commonwealth Government contributions. An indicator of less than 10 per cent generally shows there is insufficient cash from operations to maintain existing, and fund new assets. The higher the percentage the more effectively the state can finance its capital program from its own cash resources, which includes Commonwealth Government contributions.

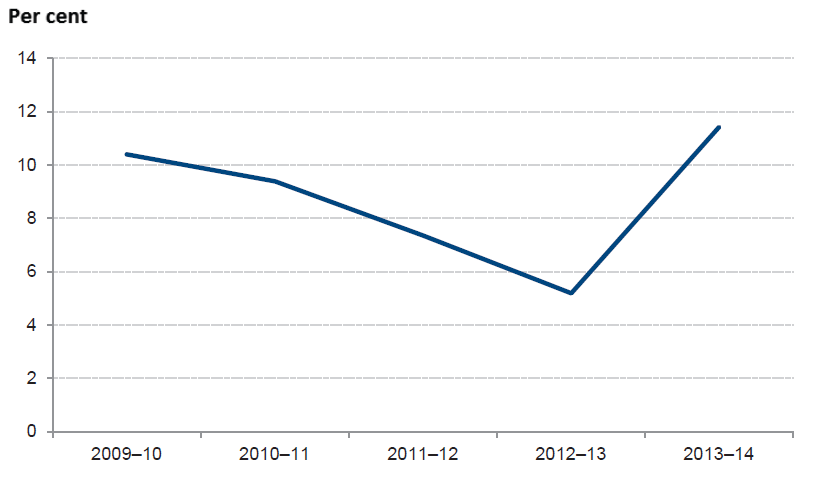

Figure 3F shows the state's ability over the past five years to fund infrastructure using cash generated by its operations.

Figure 3F

Self-financing percentage, State of Victoria, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Figure 3F indicates that since 2010–11, the state has not generated sufficient cash from its operations, which includes Commonwealth Government contributions, to fund new assets and asset renewal. Although this trend has reversed in 2013–14, a rate of between 10 per cent and 20 per cent indicates that the state may not be generating sufficient cash from operations to fund new assets.

Funding capital investment will be a continual challenge for government. The total value of Victorian public sector capital projects underway or commencing in 2014–15, as reported in 2014–15 Victorian Budget Paper number 4 State Capital Program, is approximately $72 billion.

The nature and purpose of the state is primarily to deliver public services, however, the assets it controls, and services it provides, do not always produce sufficient revenue to cover both the cost of operations and infrastructure investment. The shortfall is often significant, and requires alternate funding to be sourced through borrowings, asset sales and Commonwealth Government contributions. For example, borrowings have increased year-on-year from $15.8 billion in 2006–07 to $51.3 billion in 2013–14, which is primarily a result of infrastructure programs in the education, transport and water sectors.

Continually borrowing to fund infrastructure investment is not sustainable in the long term. Increasing debt to fund short-term investment activity has a consequential impact on future generations who must repay that debt. The money available for public services, and the ability of government to respond to fluctuations in revenue or unforeseen expenditure, is reduced when additional debt commitments require servicing.

The achievement of a financially viable and sustainable state is largely dependent on expenditure management and revenue maximisation practices. These must be prudently managed, while taking into consideration what is in the best interest of the citizens of Victoria.

3.4.4 Debt sustainability

In purely financial terms, sustainable debt is the level of debt that can be repaid while balancing factors such as economic growth, interest rates, and the state's capacity to generate surpluses in the future. Measuring the level of sustainable debt is difficult as debt is typically repaid over long periods.

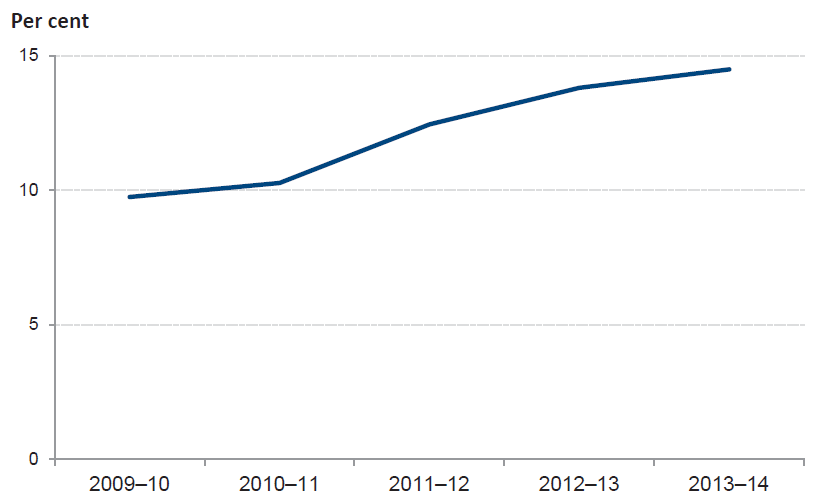

The value of borrowings as a percentage of gross state product (GSP) is an indicator of debt sustainability. A low percentage indicates that the state is better able to service its debt obligations. Figure 3G shows the state's borrowings as a percentage of GSP for the past five financial years.

Figure 3G

Borrowings as a percentage of GSP, State of Victoria, 2009–10 to 2013–14

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Borrowings are the result of government decisions around the type, timing and funding source of capital projects and public services. Public private partnerships (PPP) contribute significantly to the state's borrowings as the related finance leases are generally recognised as borrowings when the project moves into the asset's operating phase.

Figure 3G shows that borrowings have increased at a rate faster than the growth in GSP, reducing the state's capacity to service its debt. Total borrowings increased by 8.1 per cent ($3 840.4 million) in 2013–14 compared to GSP growth of 3.0 per cent.

As the state's debt increases, so too does the interest expense incurred to service the debt. In 2013–14, interest expenditure was $2 954.4 million, or 5.0 per cent, of total expenditure ($2 538.6 million or 4.4 per cent in 2012–13). Growing interest expenses will add to the pressures on the state's net result and will reduce the cash available to fund asset investment.

Meeting its fiscal target of reducing general government net debt as a percentage of GSP over the decade to 2022 will be a challenge for government, given the trend over the past five years.

4 Department of Education and Early Childhood Development

At a glance

Background

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) is a large public sector entity whose purpose is to provide educational outcomes to the community. DEECD spent $11 billion in 2013–14, and managed assets totalling $17 billion at 30 June 2014, making it a material public sector entity for the state.

Findings

- DEECD's accounting policy for economic obsolescence results in a significant write down of taxpayer investments in school buildings which are continuing to deliver educational outcomes. This write down includes recent investments in school buildings using funding from the Victorian Schools Plan (2007–08 to 2012–13) and the Commonwealth's Building the Education Revolution program (2007–08 to 2012–13).

- Schools deemed to be partially economically obsolete by DEECD include a number being delivered under Public Private Partnership arrangements.

- Our audit opinion on DEECD's 2013–14 financial report was qualified with respect to a $1.58 billion economic obsolescence adjustment to the carrying value of school buildings at 30 June 2014, and the reclassification of the prior period's school building impairment of $2.15 billion as a fair value adjustment.

- The qualification comprised three grounds, as the:

- accounting policy adopted to fair value school building assets, specifically including an economic obsolescence adjustment, was not appropriate

- key valuation assumptions and judgements were not be supported by sufficient appropriate evidence

- reclassification of previously reported 30 June 2013 balances does not accord with Australian Accounting Standards.

- DEECD's accounting policy also results in significantly less 'depreciation equivalent' funding for the renewal or replacement of school buildings, including school refurbishment, rehabilitation or rejuvenation. Seven out of every 10 schools were subject to an economic obsolescence adjustment.

- Victoria is the only Australian jurisdiction that we have identified which makes an adjustment for economic obsolescence solely on student enrolment data.

- Our concerns over DEECD's management estimates and judgements meant the audit risk relating to these significant audit areas increased. Australian auditing standards require us to apply increased audit scrutiny across all areas of the financial statements.

- Financial report preparation by DEECD was inadequate. We requested 15 adjustments to the draft financial statements totalling some $850 million, and identified a further four areas of concern.

Recommendations

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development maps the requirements of all applicable Australian Accounting Standards to their underlying systems and records, and identifies any gaps or limitations that prevent the preparation of a complete and accurate set of compliant financial statements.

- That the Department of Education and Early Childhood Development critically reviews its financial report preparation processes to identify areas for improvement and implements all improvements before the 30 June 2015 reporting cycle.

4.1 Background

Public sector entities are entrusted with taxpayer's money to provide public services. The preparation of a timely and accurate financial report is a key mechanism by which a public sector entity is accountable to taxpayers for the stewardship of public funds and assets.

The Department of Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD) is a large public sector entity whose purpose is to provide educational outcomes to the community. It spent $11 billion in 2013–14, and managed assets totalling $17 billion at 30 June 2014.

DEECD is material to the state's Annual Financial Report. This means that DEECD's transactions and balances need to be completely and accurately recorded for the results of the state to be considered complete and accurate.

4.2 Concerns over the valuation of school buildings

In November 2013, Parliament was alerted to our concerns about DEECD's approach to impairing school buildings in our Portfolio Departments and Associated Entities: Results of the 2012–13 Audits report.

That report highlighted that since 2006, DEECD had written down the value of school buildings as it considered that schools with more space than they were entitled to were impaired. By 30 June 2013, DEECD had written down the carrying values of its school buildings by a total of $2 149 million. This write down includes taxpayer funds provided through the Victorian Schools Plan (2007–08 to 2012–13) and the Commonwealth's Building the Education Revolution program (2007–08 to 2012–13), which together invested $4.4 billion in school building assets.

DEECD's approach to impairment meant that a portion of school buildings that were still providing educational outcomes and available for community use were not recognised in DEECD's, and consequently the state's, financial statements. We requested in that report to Parliament, that DEECD review its impairment policy.

We had previously raised our concerns with DEECD's impairment approach in 2012 when the impairment charge for that year was $615 million, significantly more than had been charged in previous periods and material to that year's comprehensive income statement. These concerns were raised through our 2012 final management letter where we recommended that DEECD review its impairment policy.

We nevertheless determined to issue an unmodified audit opinion on DEECD's 30 June 2013 financial statements on 11 September 2013 having received a commitment from DEECD that this issue would be resolved by the end of the 2013 calendar year and that it was appropriate to alert Parliament to this significant issue.

Notwithstanding the grace period provided to DEECD to resolve this matter, it had not been satisfactorily resolved for the 30 June 2014 financial statements.

4.3 DEECD's approach to the fair valuation of school buildings

Following our recommendations that DEECD review its previous approach to the impairment of school buildings, it changed its approach, and introduced a new economic obsolescence adjustment for the year ending 30 June 2014 in order to determine the fair value of school buildings.

An explanation of the two approaches taken by DEECD and an illustrative example of the 2014 approach are set out below.

The change in approach from 2013 to 2014 resulted in a $559 million increase in the fair value of school buildings, which had been previously written off as impaired.

DEECD's previous approach to impairment

School buildings were valued on depreciated replacement cost (DRC) basis. The Valuer-General conducted a valuation of all school buildings and determined what the cost would be to replace the existing school buildings based on current costs and condition.

Subsequent to the DRC valuation, DEECD determined that the value of certain school buildings were impaired. That means that it had determined that those schools had more space than they were entitled to based on current student enrolments, and therefore they were written down in accordance with AASB 136 Impairment of Assets.

DEECD's current approach to economic obsolescence

School buildings continue to be valued based on a DRC basis. However, the measurement of replacement cost differs from the previous approach as it includes an adjustment for the assessed level of economic obsolescence.

DEECD's current approach to determining the cost to replace school buildings is not based on what currently exists, but it is determined based on the size of school that would be required using the higher of current student enrolments or forecast long‑term (seven year) enrolments.

The DEECD valuation policy is based on the premise that it would not replace the existing area of a school if the current or forecast future student enrolments do not support a school of the current size. The difference between what DEECD deems to be the required school space, and the actual school space, is considered by DEECD to be economically obsolete in accordance with AASB 13 Fair Value Measurement.