Collections Management in Cultural Agencies

Overview

Museum Victoria, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Public Record Office Victoria, are custodians of important state collections acquired and developed over nearly 160 years and valued at around $5 billion. These collections are generally well managed despite gaps in the agencies’ collection management policy and procedure frameworks. However, there are systemic issues requiring attention with respect to collection storage, gaps in collection documentation, inadequate performance reporting on collection management and the need to make collections more accessible online.

Arts Victoria, a division of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, is responsible for advising and supporting the Minister for the Arts on arts policy, and for providing support and oversight of state-owned arts and cultural agencies. It needs to more purposefully lead and oversight the agencies to address these systemic issues and realise government priorities.

Collections Management in Cultural Agencies: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2012

PP No 185, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Collections Management in Cultural Agencies.

Yours faithfully

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

24 October 2012

Audit summary

The National Gallery of Victoria, Museum Victoria, State Library of Victoria, Public Record Office Victoria, Arts Centre Melbourne and the Australian Centre for the Moving Image are custodians of important state collections acquired and developed over nearly 160 years. These collections have natural history, scientific, historical, artistic and cultural significance, and were valued at around $5 billion at 30 June 2012. The collections are a valuable resource to the people of Victoria and include items that cannot be replaced if lost, damaged or stolen.

While only a small proportion of collections are on public display at any one time, collections are increasingly being made accessible to the public through a range of online and other digital strategies. This brings with it some significant challenges, not the least of which is how to determine what should be available in a digital format from collections that range in number from 70 000 to nearly 17 million items.

Storage space is a perennial challenge for the agencies. In addition to adequate capacity, facilities need to be designed so that items are easily accessible and allow for their safe handling and transfer. Furthermore, storage environments need to be controlled to maximise the preservation of each collection.

Arts Victoria, a division of the Department of Premier and Cabinet, is responsible for advising and supporting the Minister for the Arts on arts policy, and for providing support and oversight of state-owned arts and cultural agencies.

This audit examined whether state collections of natural history, scientific, historical, and cultural significance are adequately managed, including whether:

- agencies holding key collections have adequate collection management policies, systems and practices, and can demonstrate performance against relevant statutory obligations—three cultural agencies, Museum Victoria, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Public Record Office Victoria, were examined in detail

- Arts Victoria adequately supports the delivery of relevant government priorities and oversees the collection management practices of agencies.

Conclusions

Museum Victoria, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Public Record Office Victoria, are managing the collections well despite none of them having a comprehensive collection management policy and procedure framework. However, there are systemic issues related to storage pressures, gaps in collection documentation, inadequate performance reporting on collection management and the need to make collections more accessible online that require attention.

Arts Victoria needs to more purposefully lead and oversight the agencies to address these systemic issues and realise government priorities.

Agency collection storage facilities are at or near capacity. This is compromising collections management and creates a significant risk for the future development and preservation of the collections. The lack of active deaccessioning by agencies has exacerbated storage pressures.

The agencies need accurate, comprehensive and current information about their collections to enable effective management and to facilitate access. There are gaps in the documentation of collections due to their size, the long periods over which they have been gathered, and record keeping systems and practices that have varied in quality and completeness over time. The lack of comprehensive condition information for all collection items limits the capacity of agencies to strategically target their conservation activities.

The rigour and scope of publicly reported performance information on the adequacy of collection management requires improvement. Currently reported performance information on the adequacy of collection storage is not reliable.

Direct access to the collections is well managed with active exhibition and public programs aimed at using them to engage the community. The agencies have extended online access to the state collections in line with government priorities, but progress varies and has not been guided by adequate strategies. Online access to the collections is relatively small and significant opportunities exist to make Victoria’s cultural heritage more accessible for all.

Findings

Leadership and oversight by Arts Victoria

Arts Victoria has the primary leadership role in advising and supporting the Minister for the Arts on policy, and oversighting agencies managing the state collections. However, it has not sufficiently leveraged its oversight mechanisms and the information at its disposal to realise government priorities and address systemic collection management challenges.

In 2005–06 Arts Victoria introduced service level agreements with all agencies except the Public Record Office Victoria. These agreements include funding details, agreed service outputs and extensive reporting requirements.

There is clear evidence that Arts Victoria reviews and assesses the information and documents provided by agencies under the service level agreements and information from the Public Record Office Victoria, including monthly reports. However, these assessments are undertaken on a serial, agency-by-agency basis with few examples of cross-portfolio analysis on performance and emerging issues and risks. Further, this performance data is not annually collated and compared across agencies and over time. As a consequence, it is not used effectively to inform the minister, the agencies, or the community on agency performance, or to drive the management of common collection management issues and challenges.

Government priority areas have been communicated to agencies each year since the introduction of service level agreements in 2005–06. Government priority areas are areas of interest, influence or activity that the state has chosen, as a matter of policy, to give priority, importance or prominence to. They have consistently included a focus on storage, shared services and extending digital access to collections. Arts Victoria does not effectively assess, monitor or advise the minister on agency progress in implementing the government priority areas. It collates individual agency statements of progress on implementing them but does not extend this analysis to an overall assessment of the extent to which they have been achieved or addressed.

Arts Victoria has facilitated some collaboration between agencies in relation to collections management issues including digitisation and storage but there are opportunities to use agency collaboration more purposefully to improve performance measurement and benchmarking, and share resources across agencies.

Arts Victoria has not actively addressed longstanding inconsistencies across the agencies in measuring performance and collection management costs. Further, its publicly reported performance information on the adequacy of collection storage is not based on complete and reliable evidence.

Access to the collections

Access to the collections is well managed with active exhibition programs, rotation of collection items on display, and extensive public programs aimed at using the collections to engage both broad and specific audience segments from school-aged children through to older community members.

Around eight million people visit the six agencies each year. The museum and the gallery use touring ‘blockbuster exhibitions’ to increase the number of visitors they attract each year. However, only limited analysis has been done on the extent to which these exhibitions have led to sustained increases in interest in and exposure to the state collections.

A very low proportion of collections are ever on public display and the rotation of material into the public arena in each agency varies due to the differing nature of each collection and respective agency exhibition programming approaches.

Extending access to state collections via digital media featured as a government priority for the arts portfolio between 2006–07 and 2011–12. During this period online visitation increased, approaching or exceeding physical visitation levels for agencies.

Agencies have made progress in increasing online access to their collections, but digitisation activity has not been guided by adequate strategies. The accessibility of collections using digital technologies varies considerably across agencies, reflecting the differing size and nature of their collections. Despite the challenges created by this task, there is a clear imperative for the agencies to respond to growth in online collections access and increase the development of rich online content to engage the community in their collections.

Collections management

Agencies have sound collection management practices with acquisition, storage, conservation and loans generally well managed. Notwithstanding this, the supporting collection management policies and procedure documents require improvement.

The collection storage facilities are at or near capacity and this is compromising the development, management and preservation of collection items. The National Gallery of Victoria reports only 66 per cent of its collection is stored to an acceptable industry standard. The remaining 34 per cent of the collection is held in overcrowded storage conditions and is valued at around $630 million, representing around 17 per cent of the value of the gallery’s collection. Storage issues also exist at Museum Victoria where an important part of its collection is kept in the basement of the Royal Exhibition Building which is prone to water inundation.

Ongoing growth in collections and a lack of purposeful deaccessioning by agencies has led to further pressures on collection storage facilities.

In 2006 the state purchased a property that could be used to build a shared collection storage facility. Site works and decontamination have been carried out but Arts Victoria has not been able to secure further funding to complete the project. Funding approved in 2012 to address pressing storage issues at some of the agencies is not intended for the shared storage solution and will not resolve agency storage capacity issues.

Agencies generally manage the physical and environmental conditions in storage facilities and key risks around fire, security, and pest control well. In the instances where this is not the case the agencies are taking adequate steps to address identified deficiencies.

The initial documentation and recording of information about newly acquired items is a key step in managing a collection. The agencies are adequately documenting and registering newly acquired collection items. However, they face significant legacy data issues with the documentation of their collections as they seek to transfer information on large collections developed over nearly 160 years from pre-existing paper records and multiple databases into a single electronic system.

Addressing these issues is a long-term, resource intensive process but crucial to the facilitation of knowledge of, and access to, each collection. At their current rate of progress the agencies will take decades to address legacy data issues.

Conservation activity is largely driven by the need to access items in each collection for exhibition, loans or for some other use. Surveys of the condition of collections to proactively identify issues requiring attention are only done on a limited basis. The lack of comprehensive condition information on all collection items limits the capacity of agencies to target conservation resources.

Internal agency arrangements for oversight and reporting on collections management performance include regular reporting to senior management and their governing bodies. However, the performance indicators used by agencies need to be improved to better measure key aspects of collection management.

The only publicly reported performance measure on collection management relates to the percentage of collections stored at industry standard. Agency performance against this measure is not based on complete and reliable evidence. Agencies have commenced work to address this issue and it is expected a revised and consistent approach will be in place for the 2013–14 reporting period.

Recommendations

-

Arts Victoria should more purposefully lead action to address systemic issues with the management of the state collections by:

- more rigorously advocating for the necessary resources to increase collection storage capacity

- more assertively facilitating collaboration between its portfolio agencies

- improving the rigour and scope of performance measurement and benchmarking

- actively coordinating a plan to address legacy data issues.

- The agencies should:

- expedite finalisation of strategies to guide digitisation activity

- track and report the total investment of staff and other resources into digitisation activity and the level of access to online collection material.

- Museum Victoria and the National Gallery of Victoria should undertake a targeted analysis on the extent to which ‘blockbuster exhibitions’ of collections from elsewhere in the world lead to sustained increases in visitation to the state collections.

- The agencies should:

- gather comprehensive condition information to better inform the allocation of conservation resources

- implement active collection stocktake programs

- purposefully review collections for deaccessioning opportunities

- give greater priority to addressing gaps in the policies and procedures guiding collection management activities.

Submissions and comments received

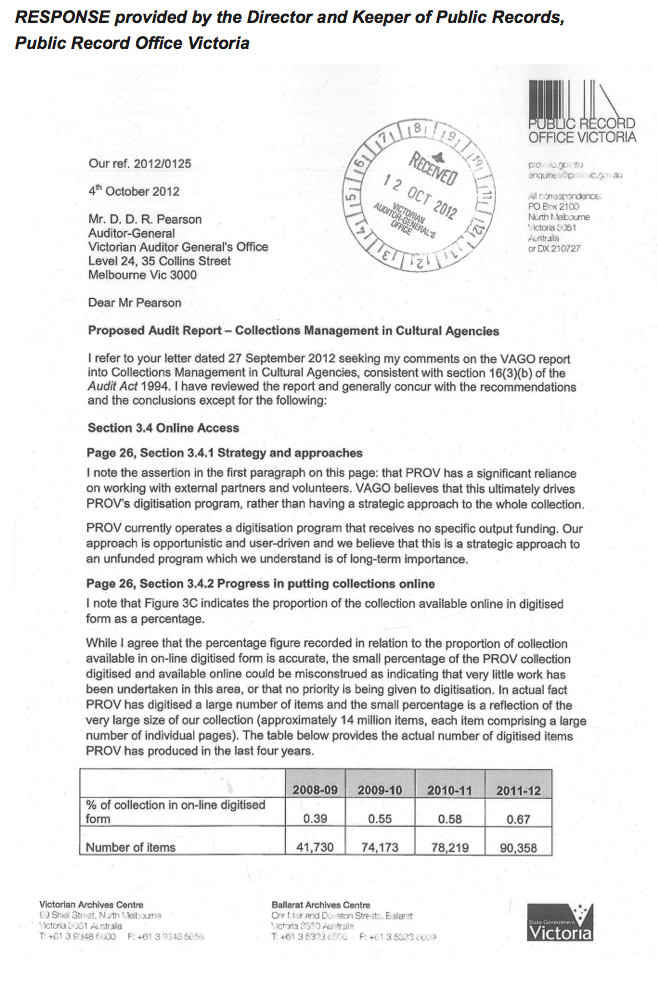

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Premier and Cabinet, Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Museum Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, Public Record Office Victoria, State Library of Victoria, and the Arts Centre Melbourne with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix B.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

Victoria’s state collections have natural history, scientific, historical, artistic and cultural significance and economic value, and require effective management to make them available to current and future generations. The state has an extensive collection of over 35 million individual collection items valued at around $5 billion.

The collections include paintings, sculptures, items from the natural sciences and human history, books, public records, performing arts material, photographs and moving images. Important items relating to Indigenous culture are also held. Figure 1A provides information on the number and value of collection items held by cultural agencies.

Figure 1A

Collection numbers and values at 30 June 2012

Agency |

Number of items in collection |

Collection value |

|---|---|---|

Australian Centre for the Moving Image |

154 |

9 |

Museum Victoria |

16 870 |

501 |

National Gallery of Victoria |

68 |

3 749 |

Public Record Office Victoria |

14 040 |

258 |

State Library of Victoria |

3 390 |

490 |

Arts Centre Melbourne |

510 |

54 |

Total |

35 032 |

5 061 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The collections are accessible to the community through displays and exhibitions, loans, direct access and via online content.

The number of items on display varies between agencies due to the differing nature of each collection. Public access also varies. While the Public Record Office Victoria does not have much of its collection on display, it is readily accessible through its reading room facilities.

1.2 The collections

Figure 1B provides a description of the collections held by the state’s cultural agencies and demonstrates the diversity of the collections.

Figure 1B

Collection descriptions

Agency |

Collection description |

|---|---|

Australian Centre for the Moving Image |

This collection contains feature films, documentaries, animation, experimental works, games, user generated content and media art works. It also includes archive material, posters, film stills and small artefacts. There are four major sub-collections: Moving Image; Installation Artworks; 2D Objects; 3D Objects. |

Museum Victoria |

This collection comprises three major sub-collections:

|

National Gallery of Victoria |

This collection includes paintings, sculptures, prints and drawings, photography, textiles and fashion, decorative arts and antiquities. |

Public Record Office Victoria |

This collection consists of permanent public records created by Victorian Government agencies. |

State Library of Victoria |

This collection consists of:

|

Arts Centre Melbourne |

This collection is made up of two major sub-collections:

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.3 Elements of effective collection management

Development and acquisition

The development of a collection through acquisition involves planning, identification, research, negotiation, decision-making and approval of prospective new additions to collections and ongoing stakeholder management. New additions may come in the form of purchases, gifts, bequests, transfers, fieldwork research, or through targeted development purchases.

Recording and cataloguing

Collection items are usually recorded, catalogued and registered into collection management systems on acquisition. Complete and accurate item information informs further decisions on conservation, restoration and valuation.

Storage

Effective storage for items both on and off display is crucial for the preservation of each collection. Storage systems allow easy access to collection items. Storage facilities are required to have environmental controls to minimise deterioration in each collection.

Preservation

The protection of collection items through activities that minimise chemical and physical deterioration and damage, and that prevent loss of information. The primary goal of preservation is to prolong the existence of collection items.

Removal

The removal, or deaccessioning, of collection items requires a robust identification, assessment, and approval framework. Items may be sold, gifted, repatriated, returned to the benefactor, or in rare cases destroyed.

Access

Collection items can be accessed physically or digitally for entertainment, research and educational purposes.

Planning and monitoring

Effective collection management also requires robust collection planning, risk management, disaster planning, resourcing, monitoring and reporting activities.

1.4 Legislative framework and agency roles

Arts Victoria is a division of the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC). It is responsible for advising and supporting the Minister for the Arts on arts policy, and providing funding, support and oversight for state-owned arts and cultural agencies. It also coordinates capital development in the arts portfolio and provides grants programs and other support for government and non-government arts agencies.

Arts Victoria is governed by the Arts Victoria Act 1972. This legislation assigns objectives to DPC and the Director, Arts Victoria which include developing and improving the knowledge and understanding of the arts, and increasing the availability and access to the arts in Victoria.

The Act also requires DPC to administer the other legislation for which the minister is responsible. These include statutes governing the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Museum Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, Public Record Office Victoria, State Library of Victoria and the Arts Centre Melbourne.

The legislation for each agency specifies functions requiring their focus on developing, preserving, and making the collections accessible to the community. The Australian Centre for the Moving Image, Museum Victoria, National Gallery of Victoria, State Library of Victoria and Arts Centre Melbourne each have governing boards or trustees who are accountable for delivery of their legislative functions. The minister has established service level agreements with these agencies to establish clear funding and service delivery expectations, and reporting requirements. Arts Victoria oversees the operation of these agreements. It also oversees the Public Record Office Victoria's activities as it is an administrative office of DPC.

1.5 Audit objective, scope, method and cost

This audit examined whether state collections of natural history, scientific, historical, artistic and cultural significance are adequately managed, including whether:

- agencies holding key collections have adequate collection management policies, systems and practices and can demonstrate performance against relevant statutory obligations

- Arts Victoria adequately supports the delivery of relevant government priorities, and oversights the agencies in relation to collection management.

This audit examined the collection management policies and practices of:

- Museum Victoria

- National Gallery of Victoria

- Public Record Office Victoria.

Arts Victoria’s leadership, oversight and support for these three agencies together with the Australian Centre for the Moving Image, State Library of Victoria and the Arts Centre Melbourne were also examined.

The audit was undertaken in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards.

The audit cost was $395 000.

1.6 Structure of the report

The structure of the report is:

- Part 2 examines the role of Arts Victoria

- Part 3 examines accessibility of collections

- Part 4 examines collections management.

2 Arts Victoria’s leadership and oversight

At a glance

Background

Arts Victoria has the primary leadership role in advising and supporting the Minister for the Arts on policy, and effectively oversighting the agencies managing the state collections.

Conclusion

There are clear opportunities for Arts Victoria to better leverage its oversight mechanisms to realise government priorities and address systemic collection management challenges. Further, the rigour and scope of its publicly reported performance information on the adequacy of collection management should be improved.

Findings

Arts Victoria:

- successfully implemented service-level agreements with agencies managing state collections, and gathers extensive information from them but does not adequately use this data to inform the minister or agencies on collection management performance

- does not effectively monitor the achievement of government priorities

- has identified opportunities for collaboration between agencies but generally has not successfully leveraged its engagement strategies to realise these

- has been slow to act on inconsistent agency approaches to measuring collection management costs

- is publicly reporting only limited performance information on the adequacy of collection storage which is not based on complete and reliable evidence.

Recommendation

Arts Victoria should more purposefully lead action to address systemic issues with the management of the state collections.

2.1 Introduction

Arts Victoria is part of the Department of Premier and Cabinet (DPC) and has the primary leadership role in overseeing agencies that manage the state collections.

Arts Victoria is responsible for advising and supporting the Minister for the Arts on policy, and providing funding, support and oversight of state-owned arts and cultural agencies. It also coordinates capital development in the arts portfolio and provides grants programs and other support for government and non-government arts agencies.

This Part of the report assesses the effectiveness of Arts Victoria in leading and oversighting the agencies managing state collections.

2.2 Conclusion

Arts Victoria needs to be more purposeful in overseeing and supporting agencies to facilitate their delivery of government priorities. It should be driving solutions to long‑standing systemic collection management challenges. These challenges include legacy data issues, insufficient storage capacity, making collections more accessible digitally and the robustness of publicly reported performance information.

Arts Victoria acts as an interface between the agencies and government. It successfully implemented service level agreements (SLA) with the agencies in 2005–06 and develops and communicates annual government priorities to them. Despite gathering extensive information under its reporting arrangements, Arts Victoria has not used this effectively to oversight agency performance. It has not sufficiently used its other engagement strategies to drive the realisation of government priorities or address systemic collection management challenges.

Despite identifying opportunities for collaboration between agencies in line with government priorities, Arts Victoria has generally had limited success in leveraging its engagement strategies to achieve these. The Victorian Cultural Network (VCN) and cooperation on seeking a shared storage solution are tangible outcomes when collaboration has occurred. However, repeated calls for delivery of shared services have not produced tangible results.

Arts Victoria has not acted with sufficient purpose to address longstanding inconsistencies across the agencies in measuring performance and collection management costs. In addition, Arts Victoria’s publicly reported performance information on the adequacy of collection storage is not based on robust evidence.

2.3 Delivery of government priorities and agency oversight

In order to facilitate the realisation of government priorities and address collection management challenges Arts Victoria needs to reposition itself to more actively lead and oversee the agencies holding state collections.

2.3.1 Agency oversight

Arts Victoria should improve its oversight by more purposefully analysing and using the information it gains to drive the realisation of government priorities and address collection management challenges faced by the sector.

In 2005–06 Arts Victoria introduced SLAs between agencies and government to strengthen governance and accountability arrangements. These agreements include funding details, agreed service outputs and extensive reporting requirements. The Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) does not have an SLA but provides monthly reports to Arts Victoria on financial and operational activity, and performance.

Arts Victoria gathers a significant amount of data from the agencies each year on their financial and operational performance. It also uses other mechanisms such as attendance at board meetings, and cross-agency forums to understand issues in portfolio agencies and communicate government direction and policy.

There is clear evidence that Arts Victoria actively reviews and assesses the information and documents provided by agencies under the SLA and other reporting arrangements. However, these assessments are undertaken on a serial, agency by agency basis with few examples of cross-portfolio analysis of performance and emerging issues and risks. Further, the performance data is not annually collated and compared across agencies and over time. As a consequence, it is not being effectively used to inform the minister, the agencies or the community on agency performance.

There are benefits in undertaking comparative analysis of agency financial and operational performance against the key performance indicators (KPIs) in the SLAs. More purposeful analysis and use of the information provided by agencies to Arts Victoria could be used to drive focused discussion on common issues and challenges at cross-portfolio forums.

In 2008, Arts Victoria commenced development of a database tool to enable collation and comparison of cross-agency data. Some analysis was produced and shared with agencies on their comparative financial performance over time. This analysis highlighted a range of issues including data quality which were well received by agencies. However, this initiative was not progressed or repeated and is a lost opportunity.

2.3.2 Development and communication of government priority areas

Since the introduction of SLAs in 2005–06, the minister has communicated government priority areas (GPA) for each financial year. They are defined in the current SLA as ‘those fields of interest, influence or activity that the state has chosen, as a matter of policy, to give priority, importance or prominence to’.

GPAs were described by the previous minister as ‘areas of interest that, consistent with government policy, have been given priority for a certain time period’.

Each SLA requires the relevant agency to respond to the GPAs when developing their annual business plan, and to report on progress towards the implementation of previous GPAs as part of the business plan.

The GPAs are approved each year by the minister based on advice from Arts Victoria. During the term of the previous government they remained relatively consistent with few changes or additions each year. Some changes of emphasis have occurred under the current government but they remain organised under the following headings:

- Whole-of-Government Initiatives

- Collaborative Initiatives

- Cultural Infrastructure: Sustainability and Revitalisation.

The minister normally approves and communicates the GPAs to agencies in March each year. The GPAs have included a consistent focus on the storage and digitisation of collections.

Arts Victoria does not provide additional explanatory content regarding the GPAs, and the annual release of the GPAs has not featured as an agenda item for the Arts Victoria-chaired monthly agency chief executive officers forum in the past five years. Given Arts Victoria’s lack of focus on assessing and reporting progress on the GPAs, it should launch the GPAs at the chief executive officers forum and include a regular agenda item on actions that are planned, or in progress to address the GPAs.

2.3.3 Monitoring progress in implementing government priority areas

Arts Victoria does not effectively assess, monitor or advise on agency progress in implementing the GPAs.

The SLAs require agencies to respond to the GPAs when developing their business plan, and to report on progress towards the implementation of previous GPAs when finalising their annual business plans. As a result, reporting on implementation of the GPAs happens only once a year. The timing of this reporting since at least 2008–09 means that Arts Victoria does not obtain information on agency progress until after the minister has determined the GPAs for the next year. The minister’s decision about which GPAs should remain or be introduced is, therefore, not informed by any advice on progress in implementing previous GPAs.

Arts Victoria’s advice to successive ministers regarding the GPAs is that they create an obligation on the agencies to provide a statement of intent or response at the start of a year and a statement of progress at the end of the year. Arts Victoria has an obligation to use the information reported by agencies to assess and report on the implementation of the GPAs.

However, there is no whole-of-portfolio reporting on substantive performance in implementing the GPAs. Arts Victoria collates individual agency statements of progress but it does not assess the overall extent to which the GPAs have been achieved or addressed. This, together with the associated lack of advice to the minister on the achievement of past GPAs creates a clear gap in management information.

To more purposefully monitor and report on performance, Arts Victoria needs to actively engage with agencies holding state collections to determine the extent to which they have achieved the desired outcomes. For example, this could be accomplished by requiring agencies to report quarterly under the SLA on progress in addressing GPAs.

2.3.4 Driving agency collaboration and consistency

Arts Victoria has had clear signals from government over the past eight years to lead improvements and greater collaboration between agencies. It has facilitated some collaboration between agencies, but has had limited success in consistently producing tangible results.

The 2004 Outcomes Outputs Framework and Action Plan for Victoria’s State Collections included specific commitments to greater collaboration and consistency across the agencies on a range of collection management issues and initiatives. This included collaboration and consistency in acquisition policies, knowledge development, storage, collection preservation services, digitisation programs, access, and the measurement and comparison of the costs of collection management and storage.

The GPAs for 2006–07 and 2007–08 included the implementation of actions set out in the 2004 plan. Most of these have not been implemented despite many of the actions in the plan not necessarily requiring significant additional funding. For example, there is still no single, agreed methodology for measuring the costs of collection management and storage.

Despite this there have been some achievements including:

- the establishment of the Arts Agencies Collections Working Group has facilitated sharing of information on collection management across agencies and some collaboration, including on a memorandum of understanding outlining commitments of support in the case of major collections disasters

- the development of the VCN project involving direct links between agencies and cross-agency work on digitisation

- agencies have been involved in developing a case for a shared collection storage facility.

The annual GPAs have continued to emphasise collaborative initiatives such as shared services. In 2004, a consultancy commissioned by Arts Victoria identified opportunities for annual efficiency savings estimated at $4.7 million. These included coordinated procurement practices, a shared agency approach to delivery of operational corporate services processes, and standardisation of enabling technology. The up-front cost of implementing the changes required to realise these savings was estimated at $6.3 million and the pay-back period was three years. Arts Victoria did not pursue these initiatives due to the initial investment required to implement shared services. This was a lost opportunity.

A GPA to establish an overarching strategic asset management framework to cover the arts portfolio was first identified in 2008–09. This remains a work in progress for Arts Victoria. The framework has been developed but has not been applied to the agencies included in the audit.

Arts Victoria convenes a chief executive officers’ forum for the arts agencies, which is intended to focus on strategic issues, directions and opportunities. However, a review of papers and minutes for the forum since 2007 identified that, while some strategic focus and examination of relevant external developments occurs, the forum’s potential to drive portfolio-wide collaboration and efficiencies has not been adequately exploited.

The cross portfolio chief information officers’ forum has similarly identified potential for collaboration in terms of joint procurement of information and communication technology services and related hardware and software but these opportunities have not been exploited to date. The chief information officers’ forum and Arts Victoria are overseeing the response to a recommendation from May 2011 to establish a shared digital storage repository for the agencies.

Arts Victoria has for many years been aware of issues with inconsistent approaches across the agencies in a range of areas including performance measurement and measuring collection management costs. The lack of a consistent approach to measuring the costs of collection management and storage was first identified in 2004 and remains unaddressed. Arts Victoria advised that this issue will be examined by the Arts Agencies Collections Working Group.

2.4 Addressing systemic collection management challenges

There are systemic challenges that need to be addressed to assure that collections held by Museum Victoria (MV), the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), the State Library of Victoria (SLV), Arts Centre Melbourne, the Australian Centre for the Moving Image (ACMI) and PROV are preserved for future generations. These challenges relate to legacy data, storage, making the collections more accessible online, and performance reporting.

Arts Victoria has not engaged in all of these challenges to lead and support agencies and agency progress has been mixed in addressing them.

2.4.1 Legacy data

Agencies need accurate, comprehensive and current information about their collections to enable effective management and facilitate access. There are gaps in agencies documentation of their collections due to their size, the long period over which they have been gathered, and recordkeeping systems and practices that have varied in quality and completeness over time.

Arts Victoria’s 2004 Outcomes Outputs Framework and Action Plan for Victoria’s State Collections acknowledged the importance of having adequate and easily retrievable information because it:

- gives collections much of their cultural (or scientific) value and meaning and is the basis on which the agencies understand and use their collections

- is a fundamental tool for agencies to manage their collections

- is a means to provide the public with access to the collections.

The action plan further acknowledged that the agencies were dealing with backlogs of collection information going back decades. It also recognised that acceptable levels of documentation in the past were not adequate to fully support collection management today.

The action plan included commitments to formulate complementary documentation programs to address documentation backlogs and to aggregated annual reporting on collection documentation. These actions have not been implemented:

- The audit found no evidence that agencies have shared their approaches, models and resources for tackling collection legacy data issues.

- Arts Victoria does not require annual reporting by agencies on progress in addressing legacy data issues.

Arts Victoria’s 2008 and 2011 reports providing an overview of the collections showed some progress by agencies in electronically documenting their collections.

Arts Victoria could better use the GPAs and KPIs included in SLAs to drive and monitor agency performance in addressing legacy data issues in collection documentation. Currently:

- the GPAs do not include any focus on legacy data issues

- the SLA KPIs do not include an indicator measuring progress in addressing the collection documentation legacy data backlog.

Arts Victoria’s agency chief executive officers’ forum has not included any substantive coverage or discussion on the legacy data backlog in the past five years. This forum should be used by Arts Victoria to highlight the importance of this issue and facilitate the sharing of approaches and learnings across agencies as they go about addressing it.

Despite acknowledging the legacy data issue and the importance of addressing it in 2004, Arts Victoria has not taken sufficient steps to assist in its resolution. It has yet to determine the full extent of the issue and to work with the agencies to develop a plan to address it.

2.4.2 Collection storage

Adequate storage facilities for the state collections are central for their preservation. The 2004 action plan identified meeting future storage requirements for the collection as a key issue to be addressed.

The collection storage facilities of the agencies are at or near capacity, ranging from 84 per cent at the Arts Centre Melbourne to 100 per cent at NGV and ACMI. This is compromising the development, management and preservation of collection items. Arts Victoria has developed proposals for an integrated solution to the collection storage issue since 2004. To date the state has purchased a property in Spotswood for $6.5 million that could be used to build a shared storage facility, and undertaken some site works including decontamination at a cost of $5.5 million. However, Arts Victoria has not been able to secure further funding to enable this project to be completed.

Arts Victoria advised that it is currently developing a proposal to construct a smaller scale modular storage facility on the Spotswood site which can be added to as the collections grow in the future. This proposal will be submitted for consideration as part of the 2013–14 Budget process. It is also considering the possible redevelopment of Scienceworks, including the construction of car parking facilities on the cleaned up Spotswood site.

As part of the 2012–13 Budget the government approved funding of $15 million over four years to deal with urgent storage needs. Detailed planning for the use of these funds is currently underway but it is not intended to be used for an integrated solution.

Failing to address the need for additional storage facilities will further compromise the care and preservation of the collections.

2.4.3 Making the collections more accessible online

Government policy and priorities over the past 10 years have emphasised the need for agencies to increase the availability of their collections online.

- The 2003 Creative Capacity Plus policy highlighted the importance of using agency websites to improve access. It also committed to establishing a centralised online web-based resource for cultural institutions to deliver community access to their collections and programs and develop and present digital media projects.

- The GPAs between 2006–07 and 2011–12 included priorities around extending the access to digital collections, content and services to be developed for the education sector and broader community using the VCN site and agency websites.

Arts Victoria led the VCN project, has encouraged agency collaboration, and included a KPI in the SLA dealing with the proportion of the total collection that is available online in digitised form. Beyond this, Arts Victoria has not:

- sought to develop a sector-wide approach and strategy for digitisation covering consistency in approaches, formats, systems, storage and access methods for digital collections across the agencies

- sought digitisation strategies and plans from the agencies to test whether they exist, are robust, and provide a sound basis for digitisation activity

- provided guidance to agencies about the key criteria to be used to prioritise digitisation activity

- determined whether agencies have established soundly based short- and long‑term targets for the proportion of each collection that should be available online in digitised form

- established indicators of success for digitisation activity

- monitored agency planned and actual investments in digitisation activity—such as staffing and equipment costs and website developments—to determine the potential for efficiencies, shared resources and procurement, and the total investment across the sector.

As a result, each agency has developed its own approach and made its own investments uninformed by an overarching portfolio strategy. These investments have not been wasted because the agencies have used relatively consistent and sound criteria for digitisation. However, even though Arts Victoria has advised that digitisation is now seen as a business-as-usual activity for all agencies that is to be funded out of existing resources, there is, nevertheless, clear scope for these separate agency activities to benefit from an overarching portfolio strategy and coordinated approach.

In terms of measuring the success of digitisation activity, the audit found that the agencies are not routinely gathering data on access levels for online collection material. Arts Victoria has not requested this information and should consider incorporating a relevant KPI in future SLAs.

The Victorian Cultural Network project

The VCN project started in 2003 and has primarily involved developing the Culture Victoria website to provide access to material from the digitised collections of NGV, MV, ACMI, SLV, Arts Centre Melbourne, and a range of metropolitan and regional organisations. It was also intended to facilitate collaborative projects across agencies, including digitisation of content for research, education and public purposes.

The Culture Victoria website incorporates digital content on state collections specifically developed for it in stages one and two by the five partner agencies and also has a search function enabling searches to return results from ACMI, Arts Centre Melbourne, MV, NGV, SLV, the Victorian Heritage database and metro-regional organisation websites. Although PROV is not linked to the VCN fibre network for cost reasons, it contributes searchable content to the website.

The project has had three stages to date with a total investment of $6 million:

- Stage 1 ($2.86 million)—focused on linking cultural agencies by optical fibre and established the website Culture Victoria. Funding of $1.4 million was shared among the five partner agencies.

- Stage 2 ($2.16 million)—focused on digitising and developing digital content for education users and increasing content on Culture Victoria from metro-regional cultural organisations. Funding of $1.3 million was shared among the five partner agencies.

- Stage 3 ($1.04 million)—over four years (2011–12 to 2014–15) is focusing on developing digital systems and content from Victoria’s metro-regional cultural organisations. Funding of $420 000 will be distributed by Arts Victoria to the metro-regional cultural organisations with no funding to the five partner agencies.

Stages 1 and 2 of the VCN project produced 139 stories based around collection material from the agencies including, 1 895 images, 433 videos and 67 audio recordings.

The Culture Victoria website was launched in October 2007. Figure 2A shows information about access to the site between 2007–08 and 2011–12.

Figure 2A

Access to the Culture Victoria website

Year |

Visits |

Unique visits |

Page views |

Average time on site per visit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

2007–08 |

8 429 |

5 837 |

10 499 |

1:03 |

2008–09 |

2 501 |

1 808 |

4 343 |

1:22 |

2009–10 |

12 094 |

8 700 |

58 095 |

4:40 |

2010–11 |

67 335 |

53 888 |

289 683 |

3:23 |

2011–12 |

134 535 |

111 302 |

464 909 |

2:11 |

Total |

224 894 |

181 535 |

827 529 |

2:32 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Visitation to the Culture Victoria website was very low in its first three years and was not commensurate with the significant investment in establishing it. The significant increase in visitation in 2010–11 is attributed to the fact the site was redeveloped at this time to provide Web 2.0 functionality and to address issues with its original design. The redeveloped site was more visible in common search engines than it had been previously. A key focus of the current stage of the project is on how to better promote this resource utilising traditional media and the new interactive social media.

2.4.4 Performance reporting on collection management and storage

Arts Victoria gathers performance data from the agencies on their activities, including collection management. Some of this performance information is reported publicly in DPC’s annual report and the annual Budget Papers.

The performance indicators used by the agencies relating to collection management could be enhanced by including additional indicators dealing with conservation activity, the costs of collection management, and rotation of the collections onto public display. The suite of KPIs included in the SLAs could similarly be enhanced to provide greater insights into agency collection management performance.

The Budget Paper 3 output measure ‘Agency collections stored to industry standard’ was introduced by Arts Victoria in 2007–08 without a rigorous, documented methodology. This has led to varying interpretations by agencies of what and how to measure performance against this indicator, and inconsistencies in what is reported.

Further, there is not currently an annual formal, evidence-based and documented assessment of collection storage facilities against a designated industry standard or standards by each agency to support their reported performance on this indicator. Reported performance is based on the professional judgment of collection management staff. As a result, while this information may provide a useful indication of agency performance with respect to the adequacy of collection storage arrangements it is not supported by robust evidence that can be validated.

Arts Victoria began working with the agencies in mid-2011 to facilitate the development of an evidence-based assessment and measurement methodology which can be applied consistently across agencies. This is planned for completion by the end of 2012 and is to be used for 2013–14 reporting. While this focus on improving the reliability of the measurement and reporting on this performance indicator is welcomed, it is also overdue given the range of issues identified which point to the reported performance for this measure being insufficiently robust since 2007–08.

Until this is completed, these weaknesses should be noted in Arts Victoria’s publicly reported aggregate performance information on this measure which is published in DPC’s annual report and the State Budget.

Recommendation

- Arts Victoria should more purposefully lead action to address systemic issues with the management of the state collections by:

- more rigorously advocating for the necessary resources to increase collection storage capacity

- more assertively facilitating collaboration between its portfolio agencies

- improving the rigour and scope of performance measurement and benchmarking

- actively coordinating a plan to address legacy data issues.

3 Accessibility of collections

At a glance

Background

Making their collections easily accessible to the community for education, entertainment and research is a statutory responsibility for Museum Victoria, the National Gallery of Victoria and the Public Record Office Victoria.

Conclusion

Direct access to the collections is well managed with active exhibition and public programs aimed at using the collections to engage the community. The agencies have extended online access to the state collections in line with government priorities, but progress varies and has not been guided by adequate strategies.

Findings

- The agencies are strongly focused on making the collections accessible and do so using a variety of strategies involving both direct and online access.

- Despite active exhibition and education programs and rotation of collection items on display, a very low proportion of the collections are ever on public display.

- While the agencies do not all have clearly documented strategies and policies to guide the digitisation of collection items they are applying sound criteria.

- The online availability of the collections has increased gradually but varies considerably across the agencies reflecting the differing size and nature of their collections.

Recommendations

The agencies should:

- expedite finalisation of strategies to guide digitisation activity

- track and report the total investment of staff and other resources into digitisation activity, and the level of access to online collection material.

Museum Victoria and the National Gallery of Victoria should undertake a targeted analysis on the extent to which ‘blockbuster exhibitions’ of collections from elsewhere in the world lead to sustained increases in visitation to the state collections.

3.1 Introduction

The state collections have considerable cultural, artistic, historical, natural history, and scientific significance and should be accessible to the community for education, entertainment and research. This obligation is recognised in the legislation that governs the management of each of these collections.

The collections are made available to the community through displays and exhibitions, managed direct access, loans and touring exhibitions. The online environment enables the agencies to provide broader access to the collections and to share knowledge about them with the public.

This Part of the report focuses on the effectiveness of Museum Victoria (MV), the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) and the Public Record Office Victoria (PROV) in making their collections available to the community.

3.2 Conclusion

Direct access to the collections is well managed with active exhibition programs, rotation of collection items on display and extensive public programs aimed at using the collections to engage both broad and specific audiences from school aged children through to older community members. There is active promotion of opportunities for access to the collections.

While there are strategies in place to make collections physically accessible, a very low proportion of collections are ever on public display. Extending access to the state collections through digital media was a key government priority area for the arts portfolio between 2006–07 and 2011–12. Agencies have made progress in increasing this form of access to their collections, but digitisation activity has not been guided by adequate strategies. The accessibility of collections using digital technologies varies considerably across agencies reflecting the differing size and nature of their collections.

The proportion of collections available online has increased and agencies are exploring new ways to engage in the digital world through, for example, applications for mobile devices. Agency approaches and progress in making the collections more accessible online is consistent with their national and international peers.

More analysis is required on the extent to which ‘blockbuster exhibitions’ of collections from elsewhere in the world have led to sustained increases in interest and exposure to the state collections.

3.3 Direct access

Physical access to the collections is well managed with active exhibition and education programs, rotation of collection items on display and extensive public programs aimed at using the collections to engage both broad and specific audiences from school aged children through to older community members.

Each agency’s approach varies due to the nature of their collections. NGV’s approach is to show iconic works from the collection on permanent display and rotate other collection items over time through temporary exhibitions. MV uses long-term themed exhibitions and a travelling exhibitions program to showcase elements of its collection. Access to PROV’s collection is managed through reading rooms where the public can access records on request at one of its two archives centres.

NGV and MV also use ‘blockbuster exhibitions’ to attract the public to their venues. These are typically high-profile and high-value temporary exhibitions loaned from institutions around the world that are accompanied by large marketing and publicity campaigns. These exhibitions contribute to broader government objectives of attracting interstate and international visitors to Victoria and provide Victorians with access to major international collections that they might otherwise not have the opportunity to experience.

Figure 3A shows visitor numbers to agency facilities between 2008–09 and 2011–12.

Figure 3A

Visitors to agency facilities

|

Agency |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Australian Centre for the Moving Image |

332 320 |

749 942 |

1 138 217 |

911 635 |

|

Museum Victoria |

1 642 901 |

2 122 227 |

2,229,558 |

1 965 568 |

|

National Gallery of Victoria |

1 580 815 |

1 607 376 |

1 523 325 |

1 548 308 |

|

Public Record Office Victoria |

218 616 |

407 480 |

104 126 |

154 333 |

|

State Library of Victoria |

1 528 533 |

1 541 600 |

1 546 290 |

1 580 338 |

|

Arts Centre Melbourne |

2 000 000 |

1 889 000 |

1 764 000 |

1 736 657 |

|

Total |

7 303 185 |

8 317 625 |

8 305 516 |

7 896 839 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Visitor numbers have been largely static over recent years:

- NGV—the opening of NGV Australia at Federation Square in late 2002 led to a significant increase in NGV’s overall attendance numbers. However visitor numbers have been relatively static since the redeveloped NGV International on St Kilda Road was opened in December 2003. The number of visitors for 2004–05 was just over 2 million largely due to the success of The Impressionists exhibition which was the inaugural Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibition. Around 380000 people attended this exhibition. Subsequent Melbourne Winter Masterpieces exhibitions have not attracted this level of audience numbers with most generating around 200 000 visitors.

- PROV—the number of visitors to PROV’s reading rooms increased in 2011–12 but remains below earlier years. This is attributed to the growth in online access over this period and to a change in policy in July 2010 which increased the number of records able to be ordered for one visit.

- MV—the number of visitors for 2009–10 and 2010–11 exceeded 2million largely due to the success of ‘blockbuster exhibitions’. Total visitor numbers dropped below 2 million for 2011–12.

The agencies undertake regular audience research including visitor exit surveys to better understand audience profiles and satisfaction levels. These surveys show a high level of satisfaction among users, typically exceeding 90 per cent.

Blockbuster exhibitions are analysed and reported on in terms of audience numbers and financial outcomes, but the analysis of their impact on the numbers of visitors to the state collections is limited. The analysis undertaken to date suggests that these exhibitions do not have sustained flow-on effects for state collections.

3.3.1 Agency-specific issues

National Gallery of Victoria

Collection items not on public display such as prints and drawings or paintings held in storage can be accessed through managed access arrangements.

Temporary exhibitions are guided by an exhibition policy. An exhibition schedule is in place for the period 2011–12 to 2015–16. This is complemented by an ongoing program for renewing and refreshing gallery spaces. A five-year exhibition strategy is planned for development in 2012–13.

In June 2012, 3.6 per cent of state collection items were on display at NGV venues. This is lower than usual because NGV display areas for two high volume collections—the Asian and Antiquities collections—were closed for renewal. NGV advised that while trend information on collection items on display is not routinely measured, it has ranged between 5 and 10 per cent when captured in the past. Around 80 per cent of NGV’s collection items have not been on display since 2003.

NGV’s business plan for 2011–12 identified the development of a business case for additional funding to improve access, primarily through increased opening hours. This was not developed, but NGV is investigating options for extending its opening hours.

In addition to routine audience research, NGV has also undertaken surveys of the general population regarding their awareness that entry to NGV is free. The most recent general population survey in 2011 found that around 48 per cent of those surveyed believed that entry to NGV is free. This is higher than in previous surveys but presents an opportunity for NGV to build on community awareness of free entry to view the state collection.

Public Record Office Victoria

The reading rooms at the Victorian Archives Centre and Ballarat Archives Centre are PROV’s primary mechanism for making the collection physically accessible to the community. The public can access records on request at these locations. PROV has reviewed and improved the reading room model and processes in recent years.

PROV provides a wide range of printed and online guidance material to assist the public to understand the scope of the collection and how to search and access records of interest. It also runs two education sessions each month to assist and promote access to the collection.

Despite identifying the education sector as a priority for increased access in its 2008 10-year service delivery strategy, PROV has only limited online content specifically targeted at engaging this sector. It is drafting a strategy for the development of existing and new online content to create greater engagement with the primary, secondary and tertiary education sectors.

PROV has a small exhibition program compared to the other agencies examined as part of the audit. It has small exhibition spaces at the Victorian Archives Centre and Ballarat Archives Centre and has exhibitions designed to travel around Victoria. It is also funded to manage exhibitions at the Old Treasury Building.

Exhibitions are typically developed in response to anniversaries of significant events in the history of Australia, Victoria or Melbourne, or the acquisition of significant new collection items which have exhibition potential. Exhibitions are usually also made available online. PROV is developing an exhibition strategy.

Museum Victoria

MV has rigorous processes in place to guide exhibition planning and development.

Interest in the Melbourne Museum, Scienceworks and the Immigration Museum is driven through a mix of:

- Long-term themed exhibitions—a suite of these are typically installed for around 10 years each. They are designed to be topical and relevant to visitor interests and education curriculums, and parts are refreshed during this time to sustain interest and enable object/specimen changeover for conservation reasons. These exhibitions are replaced to sustain visitation by encouraging repeat and new visitors.

- Touring exhibitions—MV has a travelling exhibitions program which aims to deliver two touring exhibitions each year to provide broader access to its collections and a program of incoming temporary exhibitions from other institutions and sources.

- Blockbuster exhibitions.

In June 2012, 0.5 per cent of state collection items were on display at MV venues. This is typical for the past four years and reflects the fact that the majority of MV's collection, especially the natural sciences collection, is acquired for its high research value rather than its display value.

MV also provides access to its collection for research purposes through direct access by appointment, loans, scholarship programs and internships and online content.

There are discovery centres located at the Melbourne and Immigration Museums that are designed to assist and encourage the public to discover these collections. These centres also have an online presence.

MV also provides access to its collections through public programs such as:

- education programs involving self-guided activities, or tours led by museum staff

- children's programs that are offered across the three museums

- off-site programs designed to cater for people who may find it difficult to visit MV and other audiences including young children and older adults in community care.

MV actively loans collection items for both exhibition and research purposes to external entities for fixed periods of time.

3.4 Online access

Given the low proportion of collections ever on public display, the online environment enables agencies to provide increased access to their collections and to share knowledge about the collections with a range of interested people. Figure 3B shows that online visits now approach or exceed physical visits for the agencies.

Figure 3B

Visitors to agency facilities and websites—number of user sessions

|

Agency |

Physical visitor numbers |

Online visitor numbers |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

|

|

Australian Centre for the Moving Image |

1 138 217 |

911 635 |

1 176 629 |

1 107 401 |

|

Museum Victoria |

2 229 558 |

1 965 568 |

4 606 574 |

4 651 649 |

|

National Gallery of Victoria |

1 523 325 |

1 548 308 |

959 114 |

1 330 174 |

|

Public Record Office Victoria |

104 126 |

154 333 |

896 497 |

966 133 |

|

State Library of Victoria |

1 546 290 |

1 580 338 |

3,159 559 |

3 201 020 |

|

Arts Centre Melbourne |

1 764 000 |

1 736 657 |

2 297 296 |

1 486 482 |

|

Total |

8 305 516 |

7 896 839 |

13 095 669 |

12 742 859 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Extending digital access to state collections featured in the government priority areas for the arts portfolio between 2006–07 and 2011–12. This is achieved by putting descriptive information about collection items and where possible digital images on agency websites. Digitising state collections is a significant undertaking given the volume of items involved and the resources required to undertake the task.

3.4.1 Strategy and approaches

The importance of digitising their collections and making them more accessible online has been recognised by the agencies since at least 2004 when they agreed to share approaches and resources.

The agencies have pursued digitisation of their collections without adequately defined and approved strategies. Strategy development to underpin this activity is still a work in progress. Clear strategies to guide digitisation activity should include:

- the context for and objectives of digitisation linked to overarching organisational policies, strategies and frameworks

- a summary of current status of digitisation activity, and past and present digital initiatives

- a proposed digitisation plan for the next five years based on clear criteria and priorities and including specific targets

- an assessment of the resources required to complete the plan and strategies to obtain and allocate these resources.

None of the agencies had established adequate strategies:

- NGV’s 10-year service strategy document, developed in 2008 identified completion of the digitisation of the state collection as one of its priorities. However, NGV has not had a digitisation policy or strategy to guide its activity and does not expect to complete a strategy until the end of 2012

- PROV has had a digitisation policy in place since 2010 but not a documented strategy. PROV plans to develop a digitisation strategy in 2012–13.

- MV plans to develop a digitisation and digital preservation strategy to cover the period 2012–17 by the end of 2012.

However, the agencies demonstrated a consistent approach to prioritising which parts of their collections were to be digitised. Criteria for this activity included demand for items, their value and/or significance, and the existence of preservation risks. Funding and resource opportunities also drove the timing and focus of these activities.

The digitisation of the collections also occurred in conjunction with other activities such as registration, preparations for exhibitions, loans, and conservation assessments or treatments.

PROV’s online presence has become the primary means of making the collection accessible. It has pursued digitisation based on opportunistic use of available resources from PROV staff and volunteers, and partnerships with external organisations. Its most significant digitisation projects have involved the use of volunteers and/or external partners. For example the digitisation of the Victorian Wills, Probate and Administration Records 1841–1925 was undertaken over eight years. Volunteers digitised over 7 million images in this period.

However, PROV’s significant reliance on external partners and volunteers has meant that these groups have largely driven what has been digitised in projects they are involved in rather than PROV undertaking a series of digitisation projects based on a strategic approach to the whole collection.

3.4.2 Progress in putting collections online

Apart from bursts of digitisation activity associated with externally-funded digitisation projects, agencies typically undertake digitisation activity as opportunities arise during routine collection management activity. For example, when items are handled for conservation work, exhibition or loan preparation, or educational activities they may be photographed and data collected to improve catalogue or condition information.

Figure 3C shows gradual progress in digitising collections and making them available to a wider audience online. The proportion of collections accessible online varied between less than 1 and 35 per cent of collections by the end of 2011–12. Approaches and progress to date is broadly consistent with what has been achieved nationally and internationally.

Figure 3C

Proportion of collection available online in digitised form (per cent)

|

Agency |

2008–09 |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Museum Victoria |

35 |

35 |

35 |

35 |

|

National Gallery of Victoria |

4 |

23 |

24 |

27 |

|

Public Record Office Victoria |

0.39 |

0.55 |

0.58 |

0.67 |

Note: The Museum Victoria collection comprises over 16.8 million items that are recorded as part of 4 million collection registration units (CRUs). 35 per cent of the CRUs are available online in digitised form.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

The New Renaissance, a report published in January 2011 on bringing Europe’s cultural heritage online makes the following observation.

‘The new information technologies have created unbelievable opportunities to make this common heritage more accessible for all. Culture is following the digital path and ‘memory institutions’ are adapting the way in which they communicate with their public.

Digitisation breathes new life into material from the past, and turns it into a formidable asset for the individual user and an important building block of the digital economy. We are of the opinion that the public sector has the primary responsibility for making our cultural heritage accessible and preserving it for future generations.’

Despite the challenges created by this task there is a clear imperative for the agencies to respond to growth in online collections access and increase development of rich online content to engage the community in their collections.

PROV’s digitisation activity has proceeded slowly with less than 1 per cent of its collection accessible online at the end of 2011–12. However, around 90 per cent of PROV’s collection is searchable online using the online catalogue and indexes. These search facilities enable series and units to be located and ordered, but the extent of information about the content of the series and units varies.

The proportion of MV’s collection accessible online remained static at 35 per cent during the period 2008–09 to 2011–12, but this reflects the application of a more rigorous counting methodology than a lack of progress. There are currently around 1.4 million individual records on MV website, and external websites relating to MV collection items.

In addition to placing collection-related content on their websites, the agencies have explored other ways to engage in the digital world with applications for mobile devices and other initiatives. These include establishing a social media presence, smartphone and tablet applications, and podcasts. The potential for greater interaction with, and participation by, audiences is also being explored.

MV has also participated in a range of distributed online collection initiatives including the Global Biodiversity Information Facility, the Pest and Diseases Images Library, the Atlas of Living Australia, the Online Zoological Collections of Australian Museums, and the Google Art Project.

The agencies that are part of this audit have also participated in the Arts Victoria led Victorian Cultural Network project. While this has not involved sharing specific facilities and resources for digitisation between agencies, it has established a network of contacts focused on digitisation within these agencies.

The agencies have oversight arrangements in place for digitisation activity but they are not tracking and reporting the total investment of staff and other resources on this activity. Increasing the rate of progress in making collections available online will require additional resourcing.

3.4.3 Measuring access

In responses to a survey from Arts Victoria in 2008, agencies identified the digitisation of their collections and making them available online as a key priority for the next 10 years.

Despite this, the agencies are not using the information available to them on the number of visitors to the collections-related pages on their websites. These could provide insights into interest in, and use of, the material available on each of the collections. Figure 3D shows the visits to specific collection pages on each website.

Figure 3D

Visitors to collection pages on agency websites–number of user sessions

|

Agency |

2009–10 |

2010–11 |

2011–12 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Museum Victoria |

226 658 |

530 521 |

697 839 |

|

National Gallery of Victoria |

No data |

No data |

69 934 |

|

Public Record Office Victoria |

141 273 |

175 160 |

191 598 |

|

Total |

367 931 |

705 681 |

959 371 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

3.4.4 Challenges to making collections available online

Making cultural material available in a digital environment is challenging.

Projects, such as Google’s Art Project and the construction of a universal online library have grappled with copyright law, decisions about what underlying architecture to use and how to set protocols for importing catalogue information.

Copyright challenges have prevented the publication of some images, or in some cases metadata, online. For example, there are around 6 900 items online for which NGV has images of web publishable quality but which cannot be published due to copyright restrictions. This is predominantly an issue with contemporary artworks.

Archivists have raised concerns about how to make certain collections available, particularly those with documents that were created but not intended to be published, such as the records of government agencies. They have also highlighted the problems that are created if hyperlink reference points are not kept stable, predictable and persistent.

The agencies need to address these challenges as they continue to make their collections accessible online.

Recommendations

- The agencies should:

- expedite finalisation of strategies to guide digitisation activity

- track and report the total investment of staff and other resources into digitisation activity and the level of access to online collection material.

- Museum Victoria and the National Gallery of Victoria should undertake a targeted analysis on the extent to which ‘blockbuster exhibitions’ of collections from elsewhere in the world lead to sustained increases in visitation to the state collections.

4 Collections management

At a glance

Background