Community Health Program

Overview

Community health services are an integral part of Victoria’s primary care network. They deliver a diverse range of clinical and non-medical services, including the state-funded Community Health Program (CHP). The CHP is administered by the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), and aims to provide disadvantaged Victorians with access to high-quality general counselling, allied health, and nursing services.

In this audit, we examined whether the CHP effectively contributes to good healthcare outcomes for Victoria’s priority populations. We analysed DHHS’s management of the CHP, with a particular focus on its strategic direction, access and demand management, and performance monitoring.

This audit is important because well-coordinated primary care services may improve Victorian’s health and wellbeing, and reduce avoidable hospital admissions.

As a follow-the-dollar audit, we also looked at 10 community health services:

- four integrated health services—Bendigo Health, East Wimmera Health Service, Monash Health and Peninsula Health

- five registered community health services—Bendigo Community Health Service, cohealth, Gippsland Lakes Community Health, Latrobe Community Health Service and North Richmond Community Health

- one multipurpose health service—Orbost Regional Health.

We made seven recommendations to DHHS in this audit.

Transmittal letter

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER June 2018

PP No 397, Session 2014–18

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report Community Health Program.

Yours faithfully

Andrew Greaves

Auditor-General

6 June 2018

Acronyms and abbreviations

| CHMDS | Community Health Minimum Dataset |

| CHP | Community Health Program |

| DHHS | Department of Health and Human Services |

| DPAC | Divisional Performance Assurance Compliance |

| FOPMF | Funded organisation performance monitoring framework |

| INI | Initial needs identification |

| PEF | Performance escalation framework |

| PHW Plan | Victorian public health and wellbeing plan 2015-19 |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General's Office |

| VHES | Victorian Healthcare Experience Survey |

Audit overview

Primary care is an integral part of Victoria's health system—it includes services such as general practice, pharmaceutical services, allied health, and community nursing. In Victoria, the state and Commonwealth governments both fund the provision of primary care.

Community health services are essential to Victoria's primary care network. They deliver a range of state- and Commonwealth-funded programs, including the state-funded Community Health Program (CHP). There are 85 community health services located in rural, regional and metropolitan Victoria. These operate under two distinct legal and governance arrangements:

- Fifty-five community health services operate as part of regional or metropolitan Victorian public health services. These 'integrated' community health services are subject to the accountability frameworks of the broader health service.

- Thirty registered community health services operate as companies limited by guarantee. To receive state government funding, they must register as a community health service under the Health Services Act 1988.

The CHP aims to provide effective healthcare services and support to Victoria's priority populations. These populations receive priority access to services because they are socially or economically disadvantaged, experience poorer health outcomes, and have complex care needs or limited access to appropriate healthcare services.

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) administers the CHP through funding paid to community health services. DHHS's central office and divisions—North, South, East and West—are responsible for delivering the CHP. Each division operates several regional offices that are located across the state.

This audit examined whether the CHP effectively contributes to good healthcare outcomes for Victoria's priority populations. We analysed DHHS's management of the CHP, focusing on their strategic direction, access and demand management, and performance monitoring.

Conclusion

The CHP is a valuable tool for DHHS to keep Victoria's priority populations well, out of hospital, and productive in society. However, maximising these benefits requires DHHS to analyse demand and unmet need, and evaluate program outcomes.

DHHS does not regularly monitor whether the CHP's limited service hours are being provided primarily to Victoria's priority populations or what outcomes these services are delivering. Nor does it know where there is demand for the CHP or the extent of this demand across Victoria.

DHHS's funding model and distribution methods are based on historical data as opposed to analysis of changed population demographics. This may affect community health services' ability to deliver timely, effective and appropriate care to Victoria's priority populations. The community health services we audited do not necessarily promote their services due to lack of capacity.

DHHS's limited insights mean it is missing an important opportunity to take a more strategic approach when funding community health services, informed by a broad understanding of health service needs and utilisation across the spectrum of care services.

Recognising this, DHHS is currently progressing a number of projects to improve the CHP. These include considering a new funding model and making improvements to the Community Health Minimum Dataset (CHMDS) and use of its data. It will be necessary for DHHS to carefully monitor the results of this work and use that information to refine the program. Though the CHP's budget is very small in comparison to that for acute care services, there is a clear opportunity for DHHS to realise a significant return on its investment through effective preventative and primary health care services for the most disadvantaged Victorians.

Findings

Strategic management

Long-term health strategies

DHHS has two long-term strategies relevant to the CHP—Health 2040: Advancing health, access and care (Health 2040) and the Victorian public health and wellbeing plan 2015–19 (PHW Plan). DHHS has also released the Statewide design, service and infrastructure plan for Victoria's health system 2017–2037 to operationalise Health 2040.

The CHP's objective to provide effective healthcare services to Victoria's priority populations aligns with DHHS's long-term health strategies for better health, access and care. However, DHHS's ability to measure the CHP's effectiveness or contribution to DHHS's strategic directions is limited because DHHS does not have outcome measures or relevant data.

Evidence base for the CHP

DHHS's Community health integrated program guidelines have strong theoretical underpinnings and emphasise person-centred care. While DHHS has a range of demographic information, it does not incorporate on-the-ground information, such as indices of disadvantage or demographic data, into the CHP's evidence base. This limits DHHS's ability to translate theory into practice and deliver effective healthcare services to the right people in the right place at the right time.

DHHS should strengthen its evidence base by using population health data and information from the CHMDS. DHHS demonstrated this approach when identifying sites for the expansion of its Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Program.

Funding for the CHP

DHHS implemented a new funding model in 2007. Since then, DHHS has not reviewed the CHP's funding. As a result, DHHS cannot assure itself that its funding model supports the achievement of the CHP's objectives. DHHS has not reviewed:

- the unit price, to ensure that it reflects the true cost of providing one hour of service delivery

- the total amount of funding for the CHP

- the distribution of the CHP's funding across community health services.

DHHS's executive board has approved a proposal to undertake further research, analysis and sector engagement to inform any future funding reform options.

Access and demand

Timely access to the CHP is important—it ensures that disadvantaged people who cannot afford privately funded primary care receive the treatment that they need. Timely treatment means individuals can have better health, avoid hospital admissions and participate in society.

While DHHS can monitor who accesses the CHP, it does not do this regularly. Therefore, DHHS has limited oversight of whether services are provided to priority populations. DHHS's analysis of current or unmet demand for the CHP is limited and it does not know whether the CHP provides priority populations with effective, timely and sufficient care.

DHHS's key guidance document for managing access to the CHP is Towards a demand management framework for community health services. DHHS has not reviewed this guidance since its publication in 2008.

All the community health services we audited managed client intake in accordance with DHHS's guidance. Community health services commented that they update the tools used to prioritise clients to reflect current research. Community health services do this work in isolation from each other, duplicating effort, and do not receive specific funding for this.

DHHS is currently evaluating future health demand in the northern growth corridor by examining health risk factors, such as smoking and education levels. It has also commenced a project to examine demand in community health services by using past data and future population estimates.

Performance and quality

DHHS's performance management system

While DHHS has some tools to monitor quality, the CHP's current measuring, monitoring and reporting system focuses on outputs and lacks performance measures that assess whether care was timely and effective. As a result, DHHS cannot provide assurance through its current performance management system that the CHP delivers good healthcare outcomes for Victoria's priority populations. DHHS's sole performance measure—the number of service hours delivered—provides little insight into the efficiency, effectiveness or equity of care.

|

Process-based indicators evaluate the implementation of care as opposed to its outcomes. |

In 2014–15, DHHS piloted a set of process-based indicators to evaluate the client's administrative journey from admission to discharge. DHHS stopped collecting this data in 2016–17, following feedback from the sector that the data collection method imposed significant administrative burden on community health services. DHHS is addressing some of its data issues through a wide‑reaching improvement project and, after consulting with the sector, has begun to embed some of the process-based indicators into the CHMDS.

DHHS's management of community health services

DHHS uses a standardised performance monitoring framework to govern registered community health services. However, DHHS's divisions apply certain elements of the framework inconsistently, which leads to variances in performance management across agencies.

Adding further variation to performance management in the sector, DHHS lacks a specific performance monitoring framework for integrated community health services. This limits DHHS's oversight of integrated community health services, which may, in turn, limit its ability to identify and address performance issues in a timely and effective manner.

Program quality

As the CHP's performance measures focus solely on quantity, DHHS has limited oversight of the program's effectiveness and impact beyond community health services' accreditation cycles. DHHS is currently extending its knowledge of the CHP's quality through the collection of process-based indicators and the Victorian Healthcare Experience Survey (VHES), which assesses client satisfaction. While both tools provide insight regarding the provision of care and represent a step in the right direction, DHHS must ensure that the results of the survey are shared and used in a productive manner to yield value for the sector.

Recommendations

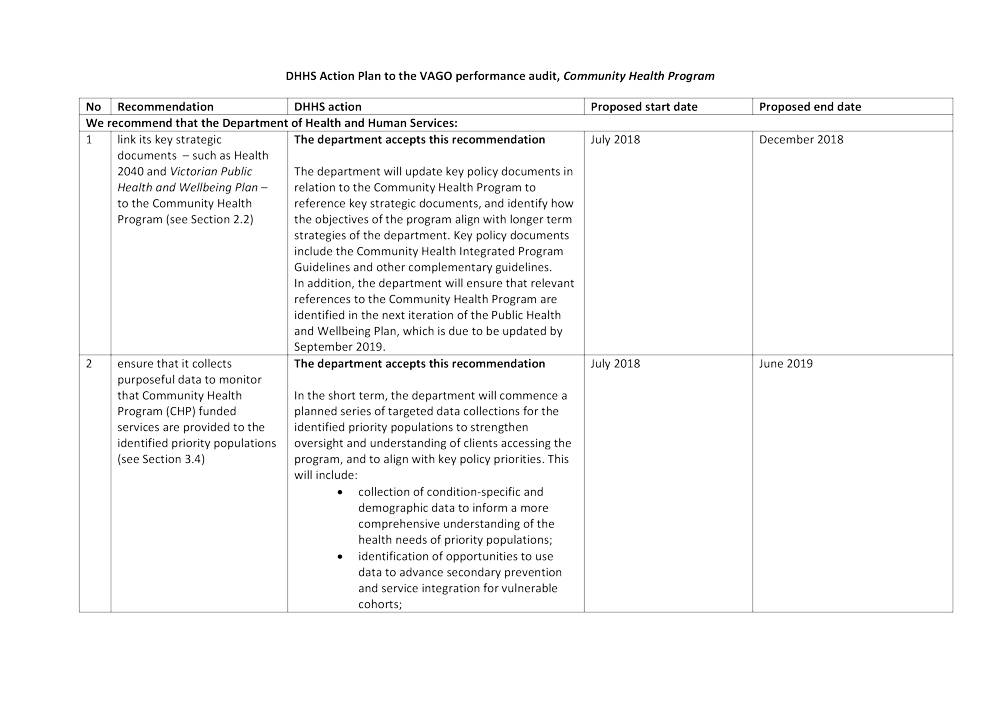

We recommend that the Department of Health and Human Services:

1. link its key strategic documents—such as Health 2040: Advancing health, access and care and the Victorian public health and wellbeing plan 2015−19—to the Community Health Program (see Section 2.2)

2. ensure it collects purposeful data to monitor that CHP funded services are provided to the identified priority populations (see Section 3.4)

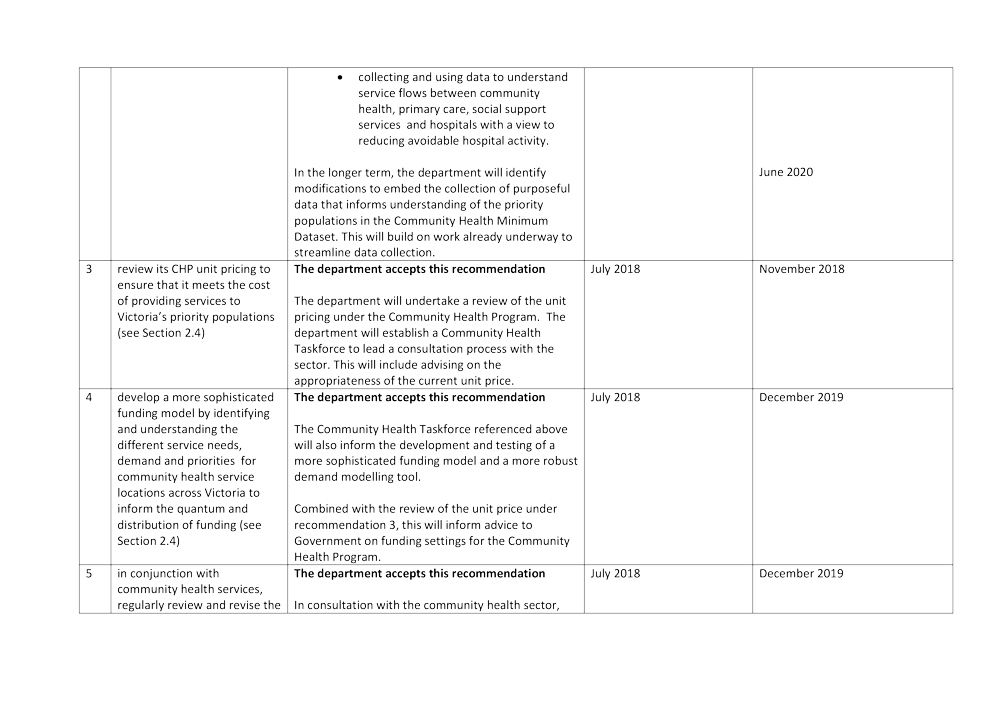

3. review its CHP unit pricing to ensure that it meets the cost of providing services to Victoria's priority populations (see Section 2.4)

4. develop a more sophisticated funding model by identifying and understanding the different service needs, demand and priorities for community health service locations across Victoria, to inform the quantum and distribution of funding (see Section 2.4)

5. in conjunction with community health services, regularly review and revise the demand management framework and clinical priority tools to ensure that they reflect optimal practice (see Section 3.3)

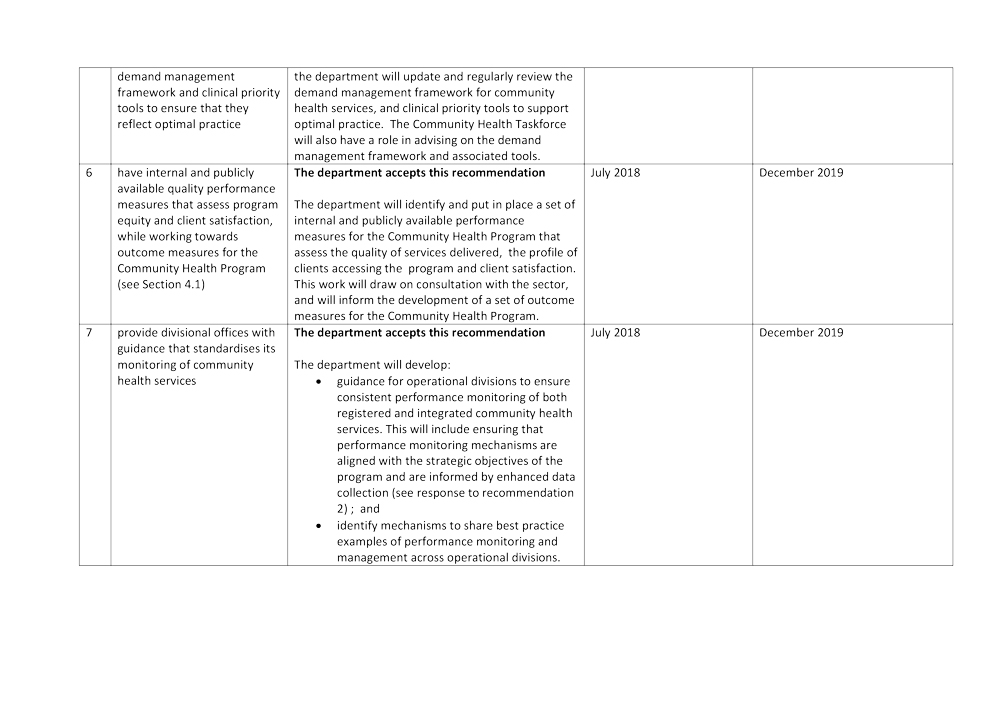

6. have internal and publicly available quality performance measures that assess program equity and client satisfaction, while working towards outcome measures for the Community Health Program (see Section 4.3)

7. provide divisional offices with guidance that standardises their monitoring of community health services (see Section 4.5).

Responses to recommendations

We have consulted with DHHS, Bendigo Health, East Wimmera Health Service, Monash Health, Peninsula Health, Bendigo Community Health Service, cohealth, Gippsland Lakes Community Health, Latrobe Community Health Service, North Richmond Community Health and Orbost Regional Health. We considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report to those agencies and asked for their submissions or comments. We also provided a copy of the report to the Department of Premier and Cabinet.

The following is a summary of those responses. The full responses are included in Appendix A.

DHHS acknowledged that the audit provides an opportunity to build on existing initiatives supporting community health services, especially for disadvantaged Victorians. DHHS accepted all our recommendations and provided an action plan detailing how these recommendations will be implemented, including its intention to form a Community Health Taskforce to consult with the sector and assist DHHS to implement the recommendations.

cohealth responded and was supportive of our recommendations, noting that their implementation will require resourcing for both DHHS and the community health sector.

1 Audit context

Primary care is a fundamental pillar of Victoria's health system—it includes services such as general practice, pharmaceutical services, allied health and community nursing. Well-coordinated primary care should improve the health and wellbeing of Victorian communities, enable the effective treatment of people with chronic diseases, and enhance outcomes for disadvantaged Victorians.

Generally, primary care is a person's first point of contact with the broader health system and it becomes the central point for ongoing, coordinated treatment. Acute care, in contrast, involves specialised, short-term intervention to address severe illness or injury. Acute care generally occurs in a hospital setting and includes admitted and non-admitted services. A good primary care system should alleviate pressure on the acute sector through the prevention and effective management of chronic diseases, reducing the number of avoidable hospital admissions per year.

In Victoria, the state and Commonwealth governments fund the provision of primary care. The Commonwealth Government provides the majority of funding through entitlement programs such as the Medicare Benefits Schedule and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme. Private allied health practitioners also operate across Victoria and provide an additional option for people seeking healthcare.

1.1 Community health services

Community health services are an integral part of Victoria's primary care network. They aim to reduce social inequity through effective consumer engagement and have strong connections to their local areas.

Community health services occupy a unique role in the Victorian landscape as a state-funded provider of primary care services. They work alongside other Commonwealth and privately-funded programs to deliver a diverse range of clinical and non-medical services. They prioritise access for people who generally have the poorest healthcare outcomes and are the most disadvantaged.

Community health services, however, are not the sole provider of primary care to disadvantaged people. These groups also access other service types, such as bulk-billing general practitioners.

Importantly, community health services are 'platform providers' of both health and social services—they can deliver up to 30 different programs through 60 different funding streams. Community health services thus facilitate a broad range of both state and Commonwealth initiatives that holistically address their clients' needs.

There are currently 85 community health services across Victoria—see Figures 1A and 1B. These differ in size and the range of programs they offer.

Most of the state's community health services formed in the 1970s to deliver the social model of health. The social model of health recognises that Victorians have unequal access to education, healthcare, cultural activities and employment. It aims to enhance outcomes for disadvantaged Victorians by providing equitable and affordable healthcare. Fundamentally, the social model acknowledges that a person's environment influences his or her health in addition to disease and injury.

Figure 1A

Community health services across Victoria

Note: LGAs = local government areas.

Source: DHHS.

Figure 1B

Community health services across metropolitan Melbourne

Note: LGAs = local government areas.

Source: DHHS.

There is great diversity across the community health sector, not just in the services they provide, but also in their operating models and their strategic priorities. While some organisations are small local services, primarily focused on the delivery of health services to disadvantaged groups within their local areas, others have grown or amalgamated to be very large organisations and operate from multiple 'satellite sites' across Victoria.

In Victoria, community health services operate under two distinct legal and governance arrangements and have different accountability mechanisms under legislation:

- Fifty-five community health services are part of rural or metropolitan public health services. They are subject to the regulatory provisions set out in Division 9B of the Health Services Act 1988.

- Thirty registered community health services are companies limited by guarantee. Registered community health services are subject to the regulatory provisions set out in Division 6 of the Health Services Act 1988.

1.2 The Community Health Program

The CHP aims to deliver effective primary care services to Victoria's priority populations. According to the CHP's guidelines, 'priority populations' refers to people who are socially or economically disadvantaged, experience poorer overall health outcomes, and have complex care needs or limited access to appropriate healthcare. These priority populations include:

- Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

- people with an intellectual disability

- children in out-of-home care

- people with a mental illness

- refugees and asylum seekers

- people experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

DHHS administers the CHP through a flexible funding source paid to community health services. Community health services deliver the CHP in addition to a broader suite of state- and Commonwealth-funded initiatives.

Figure 1C shows the range of state-funded primary and community health programs that community health services can deliver.

DHHS funds some community health services to deliver particular programs. For example, the Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Program—a specialised initiative—targets vulnerable, at-risk pregnant women and is only available in 20 local government areas. In contrast, the CHP is universal to all community health services.

Figure 1C

State-funded primary and community health programs

Note: MDC=multidisciplinary centre.

Source: VAGO based on DHHS documentation.

As shown in Figure 1D, the CHP funds community health services to deliver a range of activities, such as general counselling, allied health and nursing services. Community health services—in conjunction with DHHS—determine the mix of activities that they deliver. This flexible funding source enables community health services to customise the CHP to meet the needs of their local communities.

Figure 1D

Activities funded by the CHP

Source: VAGO based on DHHS documentation.

Client profile

In 2016–17, the CHP provided 705 318 hours of allied health, generalist counselling and nursing services to 181 977 individual registered clients. Of these:

- 57.7 per cent were female

- 1.9 per cent identified as either Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander

- 2.9 per cent identified as a refugee

- 17.6 per cent had a chronic and complex condition

- 46 per cent had a concession card.

1.3 Department of Health and Human Services

DHHS's central office has statewide responsibility for managing the CHP. This includes collecting and monitoring performance information, leading service improvement initiatives, and developing and implementing key policy and strategic directions.

DHHS's regional offices monitor the CHP's delivery by community health services and escalate performance issues to the central office when required. The central office provides key support through the provision of data and performance reports.

The Health Services Act 1988 establishes Victoria's public health services, public hospitals and multipurpose services as independent legal entities. Integrated community health services are part of rural or metropolitan health services. They are covered by the regulatory provisions set out in Division 9B of the Health Services Act 1988. A key accountability mechanism is the Statement of Priorities which is negotiated annually by DHHS with each Victorian public health service and public hospital.

Registered community health services are governed by the regulatory provisions set out in Division 6 of the Health Services Act 1988. A key accountability mechanism is the service agreement established between DHHS and the funded agency.

Overall the legislative and accountability frameworks provide both integrated and registered community health services with the flexibility to make decisions about services they deliver with state government funding, based on local needs.

Both types of community health services are subject to established performance monitoring processes, and DHHS may intervene if there are concerns about the delivery of funded programs and services.

1.4 Service delivery

DHHS funds community health services to deliver a defined number of hours of primary care. While community health services must deliver care within these thresholds, they have the flexibility to develop innovative approaches that reflect the needs of their local areas.

The CHP promotes a person-centred approach that assists clients to manage their own care, improve their understanding of the health system, and make informed decisions. It encourages community health services to undertake a team-based approach and deliver evidence-based services that 'wrap around' the individual—that is, multiple practitioners should collaborate to create a care plan that addresses the client's needs. The CHP also promotes early intervention, as this reduces the risk of further deterioration and produces better outcomes for clients.

1.5 Program funding

In 2017–18, the 85 community health services will receive approximately $105 million in funding to deliver allied health and nursing services under the CHP. This equates to around one million hours of service delivery. When compared to the overall Victorian health budget, the CHP makes up less than 1 per cent of Victoria's expenditure.

The CHP's funding is based on units and measured in service hours. In 2017–18, community health services will receive $104.93 for each hour of allied health practice and $93.62 for each hour of nursing that they deliver. This unit price must cover the community health services' travel expenses, general operating costs, rent, access coordination and the maintenance of facilities.

1.6 Why this audit is important

DHHS funds the CHP to provide effective healthcare and support to Victoria's priority populations. Community health services have the flexibility to develop innovative approaches to service delivery, such as the formation of multidisciplinary teams to support clients through a 'wrap around' model of care.

This audit is important because it is the first audit we have done of the CHP. It is also important because the CHP provides healthcare to priority populations that otherwise may not be able to afford these types of services. Along with other important primary care services—such as general practice—these forms of care can improve clients' health and wellbeing outcomes and reduce avoidable hospital admissions.

1.7 What this audit examined and how

This audit examined whether the CHP effectively contributes to good healthcare outcomes for Victoria's priority populations. We analysed DHHS's management of the CHP, with a particular focus on its strategic direction, access and demand management, and performance monitoring.

As a follow-the-dollar audit, we also included 10 community health services:

- four integrated health services—Bendigo Health, East Wimmera Health Service, Monash Health and Peninsula Health

- five registered community health services—Bendigo Community Health Service, cohealth, Gippsland Lakes Community Health, Latrobe Community Health Service and North Richmond Community Health

- one multipurpose health service—Orbost Regional Health.

We focused on how community health services manage demand and how they implement DHHS's guidelines.

The audit methods included:

- interviews with DHHS and community health service staff

- reviews of strategies, program delivery documents, policies, procedures and waiting lists

- site visits to all 10 community health services

- analysis of the CHMDS.

We conducted our audit in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and ASAE 3500 Performance Engagements. We complied with the independence and other relevant ethical requirements related to assurance engagements. The cost of this audit was $440 000.

1.8 Report structure

The remainder of this report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines the strategic management of the CHP

- Part 3 examines access and demand management for the CHP

- Part 4 examines the use of outcomes measures for the CHP.

2 Strategic management

DHHS's strategic management of the CHP is important to ensure the program has the resources required to meet its overarching objective. It is also important that DHHS can measure the contribution the CHP makes to long-term health strategies.

In this part of the report, we evaluate whether the CHP supports DHHS's strategic direction and fulfils its overarching objective of delivering effective healthcare to Victoria's priority populations. We also assessed the CHP's evidence base and examined whether its funding model is sound, regularly reviewed and strategically aligned.

2.1 Conclusion

DHHS's strategic management of the CHP partly supports the achievement of the program's objectives. A strong evidence base supports the CHP's model of care, but DHHS could strengthen this by using population health data and information from the CHMDS to better target effort. While the CHP aligns with DHHS's long‑term health strategies, DHHS is unable to measure the contribution that the CHP makes to those strategies.

While the current funding model supports some flexibility in the delivery of services, the CHP's funding model does not support DHHS to achieve the program's objectives. DHHS does not know whether the unit price, funding for the CHP and the allocation of funding provide effective healthcare to Victoria's priority populations. Further work is required to develop a funding model that aligns with the purpose of the CHP.

2.2 Long-term health strategies

Health 2040: Advancing health, access and care

The Victorian Government released Health 2040 in December 2016 after consultation with the public and the sector. By 2040, it aims for all Victorians to experience:

- better health—building skills and delivering support to be healthy and well

- better access—fair, timely and easier access to care

- better care—world-class healthcare every time.

Statewide design, service and infrastructure plan for Victoria's health system 2017–2037

The Victorian Government released the Statewide design, service and infrastructure plan for Victoria's health system 2017–2037 in December 2017 to support the delivery of Health 2040's vision. It provides a blueprint for health service and infrastructure investment for the next 20 years.

The plan includes five priority areas that will deliver Health 2040's three objectives. The five priority areas are:

- Priority area 1: Building a proactive system that promotes health and anticipates demand

- Priority area 2: Creating a safety and quality-led system

- Priority area 3: Integrating care across the health and social service system

- Priority area 4: Strengthening regional and rural health services

- Priority area 5: Investing in the future—the next generation of healthcare.

Each priority area specifies a number of focuses and actions to implement the plan's five-year goals and 20-year outcomes. Priority areas 1 and 3 relate directly to community health. The relevant actions include:

- integrating prevention and early intervention

- expanding primary care service options

- establishing health and wellbeing hubs.

The plan states that community health is a central part of Victoria's healthcare system. It commits to consolidating the sector's role by including community health in provider alliances, and health and wellbeing hubs. Importantly, it acknowledges that DHHS's current funding and organisational arrangements limit the capacity of such services to maximise integration. This may affect the delivery of services to people with chronic and complex needs.

Overall, Health 2040's vision for better health, access and care clearly aligns with the CHP's objectives to provide timely, affordable and effective healthcare to Victoria's priority populations.

As DHHS launched the plan in December 2017, it is too early to see progress. However, DHHS has formed an internal steering committee to oversee action and has committed to report on progress against the plan every two years.

Victorian public health and wellbeing plan 2015–19

The Public Health and Wellbeing Act 2008 mandates that Victoria must have a public health and wellbeing plan that identifies the state's needs, examines data and establishes key objectives. The current PHW Plan acknowledges the correlation between poor health and other social inequalities, such as limited access to housing, education, employment and public transport. It aims to reduce the avoidable burden of disease and injury so that all Victorians can experience the highest attainable standards of health, wellbeing and social participation. In October 2016, DHHS released an associated document—the Victorian public health and wellbeing outcomes framework (outcomes framework). This outlines DHHS's vision for a disease-free Victoria by progressively improving people's health.

The outcomes framework contains indicators, targets and measures for each of DHHS's strategic domains. These enable DHHS to track changes in Victorians' health and wellbeing levels over time at a population level. Two population level targets explicitly relate to the mitigation of chronic disease, including:

- 25 per cent decrease in premature deaths due to chronic disease by 2025 from 2010 baseline

- halting the rise in diabetes prevalence by 2025.

|

Place-based approaches to healthcare aim to provide Victorians with access to locally available and integrated services. |

The objective of the CHP aligns with the PHW Plan's overall vision for a healthier Victoria. The CHP helps disadvantaged people—who statistically are shown to experience poorer health outcomes—deal with issues such as chronic disease and receive support to adopt preventative health behaviours. In line with the PHW Plan, the CHP provides a place-based approach to healthcare.

The work done by community health services directly supports the measures in the outcomes framework, and the CHP prioritises services for people with chronic diseases. However, DHHS does not collect data that enables it to measure the CHP's contribution to the PHW Plan's vision.

The outcomes framework notes that rigorous evaluation of programs and continuous efforts to understand what works in different contexts should complement its reporting cycle. DHHS has not undertaken any reviews or assessments of the CHP to understand its effectiveness or impact.

2.3 Evidence base for the CHP

An effective evidence base for the CHP should:

- have sound theoretical underpinnings through the use of current, reliable and relevant research

- analyse demographics and indices of disadvantage at the local level to ensure that services and funding are appropriately targeted and address demand

- rigorously evaluate the program's impact on Victoria's priority populations.

Theoretical underpinnings

DHHS published the Community health integrated program guidelines in March 2015. These are a key component of the CHP's underlying evidence base. According to the guidelines' principles, care must:

|

Health literacy is a person's ability to understand health-related information and use this information to inform his or her decisions and actions. Good health literacy is important, as it influences a person's health and experience of the healthcare system. |

- be person centred, culturally responsive, goal directed and evidence based

- take a team approach that supports the client's health literacy levels

- encourage early intervention

- engage with health promotion.

The philosophy of person-centred care is fundamental to the CHP. Person‑centred care supports clients to participate in decision-making while respecting their preferences, diversity and background. DHHS established the CHP's underlying principles following a comprehensive literature review in September 2012. This research component of the CHP's evidence base complies with optimal practice.

DHHS's use of information

While DHHS has a range of demographic information, it does not incorporate this, indices of disadvantage or analysis of local demand issues into the CHP's evidence base. This information would strengthen the CHP, and enable DHHS to appropriately target its services and ensure that priority populations receive effective, timely and appropriate care. DHHS has begun to incorporate demographic and local demand information for other state-funded community health initiatives. For example, when identifying sites for the expansion of its Healthy Mothers, Healthy Babies Program, DHHS assessed various indicators of disadvantage, such as the concentration of child protection reports across the state. DHHS should apply the same methodological rigour to the CHP to ensure that it delivers services based on robust and practical evidence.

The CHP's impact on priority populations

Likewise, DHHS has limited oversight of the CHP's effectiveness. As discussed in Part 4 of this report, DHHS's key performance measure for the CHP focuses solely on the quantity of service hours delivered. This impairs DHHS's ability to improve and innovate the CHP's service delivery model, as it lacks information regarding the quality, appropriateness and timeliness of care.

Overall, DHHS's evidence base for the CHP is lacking—it does not adequately reflect Victoria's needs and priorities, and provides limited insight into the impact of the program.

Community health services' contribution to the evidence base

The audited community health services advised us that they maintain their own evidence base. These reflect the needs of their local areas and align with their broader strategic directions. DHHS should leverage the skills and knowledge of the sector when planning service delivery.

For example, Bendigo Community Health Service funds a Strategy, Planning and Analysis team to evaluate current research and produce guidance. This ensures that its services align with optimal practice. In July 2017, the team published an internal guide Scoping of Service Delivery Models for Generalist Counselling, which outlines the benefits, risks and challenges of various approaches to care, such as telephone psychotherapy and online counselling. Guidance like this enables Bendigo Community Health Service's clinicians to offer innovative services and make informed treatment decisions while maximising their client‑ facing time. DHHS does not specifically fund research teams at community health services, however, Bendigo Community Health Service has found that the advantages outweigh the cost. DHHS could better leverage such work across the CHP.

2.4 Funding for the CHP

DHHS funds community health services to deliver the CHP to Victoria's priority populations. To do this effectively, DHHS should:

- ensure that the CHP's unit prices for one hour of nursing and one hour of allied health care accurately reflect the current costs of service delivery

- ensure the amount of funding allocated to the CHP meets the needs of the Victorian population

- ensure that the CHP's funding is distributed according to need.

The evolution of the CHP's funding model

DHHS's unit pricing for service delivery aims to fund an hour of care, as well as the community health services' associated costs.

|

Governments may fund programs through 'block funding.' This means that the money comes with general spending instructions. Activity-based funding, on the other hand, has stricter provisions. |

DHHS adopted its previous model, the Primary Health Funding Approach, in July 2002. It included three major components:

- a unit price for service delivery

- block funding for health promotion activities (no longer part of the CHP funding model)

- a resourcing component to support any associated infrastructure costs.

DHHS commissioned a review of the Primary Health Funding Approach in 2004, which evaluated different aspects of the model. This included a survey of community health services' expenditure, visits to 20 community health services and document analysis. The consultant's report recommended that DHHS collect further evidence to inform the unit price.

DHHS's 'Frequently Asked Questions' fact sheet, dated October 2008, introduces its new funding model. The fact sheet states that DHHS undertook further work following the consultant's report before deciding on a model.

DHHS formed a steering committee to oversee the implementation of the funding model. Meeting notes from the steering committee note that the unit price for the CHP is the same as that of the Home and Community Care Program, for people aged over 65, which has transferred to the Commonwealth, and the continuing Home and Community Care Program for Younger People funded by the Victorian Government. However, DHHS has not been able to provide us with the evidence of further work undertaken to inform the development of the Primary Health Funding Approach for the CHP.

DHHS's current funding model

Unit costing

DHHS annually updates its funding requirements through the Policy and funding guidelines. This document specifies the current unit price for service delivery.

DHHS advised that the CHP's unit prices rise in line with DHHS's internal indexation, approved by the Victorian Government. The level of indexation has been between 1.5 per cent and 2.5 per cent each year for the past five years. However, DHHS has not reviewed the unit cost for the CHP since 2007—so it does not know whether the unit price accurately reflects the current cost of care in community health services.

Funding amount for the CHP

The CHP currently receives approximately $105 million in funding for the delivery of nursing and allied health services. The program received additional recurrent funding of about $1 million from 2013–14. However, DHHS has not undertaken a significant review of the CHP's total funding allocation to determine whether it addresses the needs of Victoria's priority populations.

Funding distribution

DHHS describes its current CHP funding distribution model as population based. However, DHHS lacks documentation to show how it developed the model or what calculations it uses to allocate funding to community health services.

In a December 2013 memorandum to the Minister for Health regarding additional recurrent funding, DHHS noted that it allocated the funding according to population growth, social disadvantage, the catchment population of children and the percentage of developmentally vulnerable children. This appears to be a sound approach, however, DHHS cannot produce any evidence to demonstrate its application.

DHHS has not reviewed community health services' funding allocations since 2007. Community health services located in growth corridors have not received an increase in funding proportionate to the increase in their area's population. In addition, DHHS's funding allocation does not recognise demographic changes, such as increases in disadvantage.

Therefore, the funding model may compromise the CHP's ability to provide effective healthcare to Victoria's priority populations.

Proposed new funding model

DHHS is currently considering the development of new funding models for the spectrum of healthcare that Victoria funds and manages, including the CHP. DHHS has undertaken preliminary work, including commissioning research and a literature review. This includes consideration of a new funding model based on packaged funding for specific cohorts whereby community health services are funded for the number of enrolled clients at their service.

Clients with greater complexity and those from the CHP's priority populations would attract higher payments. DHHS's executive board has approved further research, analysis and engagement with the sector before it implements any reform options.

This proposed funding model is more closely aligned to the objectives of the CHP than DHHS's current funding model.

3 Access and demand

Timely access to primary care services—such as the CHP—is important for Victoria's priority populations, as early intervention may prevent people's conditions from worsening. This can also reduce pressure on the health services providing acute care.

DHHS provides community health services with set CHP funding on an annual basis. With limited resources available, it is important for community health services to manage access and demand at the local level. Similarly, DHHS must monitor the state's access and demand issues to effectively oversee the CHP.

In this part of the report, we examine DHHS's guidance regarding the management of access and demand, and its implementation at community health services. We also assess the demand management analysis undertaken by DHHS and community health services to ensure that it supports the provision of timely and effective care.

3.1 Conclusion

Timely access to the CHP is important to prevent individuals being admitted to hospital and to support their health and wellbeing. At a local level, the community health services we audited had effective strategies in place to manage their known demand. However, as a whole, DHHS cannot demonstrate that the CHP is providing timely and equitable access across the state and meeting the demand and needs of its priority populations.

3.2 Guidance for access and demand

Community health services require guidance on access and demand procedures to deliver the CHP effectively. DHHS's guidance should ensure that community health services prioritise access for clients who are most in need.

DHHS's framework for managing demand

DHHS's framework for managing access to the CHP is outlined in its key guidance document Towards a demand management framework for community health services (demand management framework). The demand management framework assists community health services to prioritise their clients and address pressures at each stage of service delivery—inflow, flow through and outflow.

Inflow

The demand management framework provides community health services with a model for inflow—or intake of clients. The initial needs identification (INI) is an important screening process that aims to identify a client's presenting and underlying needs. DHHS provides Service Coordination Tool Templates for INI, which community health services use to seek information about clients' living arrangements, health behaviours and psychosocial status. In 2016–17, INI accounted for almost 8.5 per cent of the total service hours delivered. This demonstrates the importance of funding for this process.

To ensure community health services treat clients in the appropriate order, INI enables practitioners to triage clients as priority 1, 2 or 3. Priority 1 clients require urgent intervention, whereas priority 3 clients can safely wait for care. There are, however, no clinically recommended treatment time frames for each priority group.

To facilitate the triage process, DHHS provides community health services with two sets of tools for prioritising clients:

- a generic priority tool that identifies priority populations, those at risk of imminent harm, and people with multiple complex needs

- clinical priority tools for seven of the CHP's allied health specialties.

Flow through

Flow through describes the client's journey through the community health service until they exit. The guidelines provide a number of processes to effectively manage client flow through. These include:

- waiting list management

- appointment processes

- particular models of service delivery, such as group-based work or goal‑based intervention.

The guidelines are not prescriptive and provide community health services with the autonomy to implement and tailor processes to their individual practices.

Outflow

Outflow focuses on ensuring clients exit the community health service safely and appropriately. The demand management framework states that community health services should start planning a client's exit from the service at the first appointment. There are a number of reasons that people will exit care, including:

- only needing short-term intervention

- reaching their goals

- needing to be referred to another service for different care.

Usefulness of the demand management framework

DHHS published the demand management framework in 2008. While it provides guidance for community health services, it is now out of date. For example, it refers to A Fairer Victoria—a social strategy launched in 2005.

The demand management framework contains suggestions for community health services on how to undertake different processes, but since DHHS produced this guidance, some community health services have implemented different demand management processes—for example, for dealing with clients cancelling or failing to attend appointments. Community health services we audited commented that they were not aware of what demand management techniques other services were using and were interested in having more guidance on demand management techniques.

DHHS should review the demand management framework to determine whether it is comprehensive, evidence based and in line with current processes.

3.3 Administering the demand management framework

Community health services are responsible for administering the demand management framework. We discussed with community health services how they implement the framework in their day-to-day work.

Inflow

Various sources—such as general practitioners, health services and other community organisations—refer clients to the CHP. Individuals can also refer themselves to community health services.

Service access

All the audited community health services have service access staff to manage client intake. Typically, service access staff receive referrals from internal or external practitioners, or calls directly from clients. Service access staff are generally responsible for determining whether a client is appropriate for the CHP, initially triaging the client and scheduling an appointment. If no appointments are available, the client may be placed on a waiting list. This process takes anywhere from 10 minutes to an hour and depends on the client's complexity.

Community health services have guidelines for service access staff that are consistent with DHHS's demand management framework. Coordinating service access is an important process, as it ensures that clients receive the right care at the right time and can access services efficiently and effectively. DHHS does not specifically fund service access through the CHP, but incorporates it into the hourly cost of care.

As discussed in Part 2, DHHS has not reviewed the CHP's unit price and consequently does not know if it adequately covers community health services' cost of delivering services.

Priority tools

Service access staff first assess incoming clients against the generic priority tool. If the client is from a priority group, they receive priority 1 status. If not, service access staff use the clinical priority tools to determine whether an individual is a priority 1, 2 or 3.

DHHS developed clinical priority tools in conjunction with community health services and consumers in 2008. It formed working groups for funded allied health specialities—nursing, counselling, dietetics, adult and paediatric occupational therapy, physiotherapy, podiatry and speech pathology.

All the audited community health services commented that DHHS's clinical priority tools are general in scope. However, as shown in the case study in Figure 3A, this gives community health services the flexibility to adapt them to reflect local practice.

Figure 3A

Case study: Bendigo Community Health Service's podiatry service

|

Bendigo Community Health Service has a busy podiatry service. The podiatry team has created its own clinical priority tools to maintain consistency among practitioners. It uses the University of Texas (UT) Foot Wound Classification System to grade wounds according to their severity. This system enables the health service's podiatrists to objectively assess their clients' needs. For example, using the health service's clinical priority tool, a client with a category 3 wound according to UT's system (a wound that penetrates the bone or joint and requires immediate medical attention) would be categorised as priority 1. In addition, Bendigo Community Health Service collaborates with Bendigo Health's integrated community health service to ensure that high-risk clients receive clinically appropriate care in a safe environment. This partnership represents best practice, as it aims to ensure that clients receive the right care at the right time in the right place. |

Source: VAGO based on Bendigo Community Health Service documentation.

As DHHS last updated its clinical priority tools in 2008, community health services commented that they had to adjust DHHS's clinical priority tools to reflect current research.

In 2008, DHHS engaged consultants to evaluate initial use of the tools at eight community health services. They evaluated the tools' use by service access staff and clinicians, and tested their effectiveness in further discussions with clients.

The consultants presented a report of their findings to DHHS in 2009. The report raised specific issues with the clinical priority tools and made a number of general recommendations, including that DHHS:

- implement a mechanism for continual feedback on the clinical priority tools so DHHS can understand how they are used in practice

- review the relevant literature on clinical disciplines to ensure the clinical priority tools reflect an evidence-based approach.

DHHS advised that it would consider these recommendations in the context of its resources and priorities. There is no evidence that DHHS has implemented recommendations from this 2009 review.

DHHS's clinical priority tools aim to provide consistency in the way community health services prioritise CHP clients across Victoria. It is positive that community health services have modified the tools to reflect their local practice. However, community health services are doing this independently. This means that all 85 community health services are spending time and resources updating the tools, despite DHHS neither facilitating nor funding the process. In addition to this duplication of effort, there is a risk that community health services may have inconsistent guidelines which means some clients with the same level of need may not receive the same level of access or timely intervention.

DHHS should update the clinical priority tools to promote consistent practice and reduce duplicated effort among community health services.

Flow through and outflow

The amount of time and resources required to treat individual clients influences the community health service's ability to treat new people. This impacts the number of clients that flow through community health services. Almost all community health services reported high demand for their allied health specialties. To ensure that new clients flow through efficiently and effectively, community health services have strategies that manage access. Strategies include:

- running group sessions for some services, such as speech therapy

- regularly reviewing client care needs to identify the earliest possible exit from the community health service.

Analysis of the CHMDS shows that 90 per cent of the CHP's clients access services for 10 sessions or fewer—see Figure 3B. While some clients may only need short-term intervention, this demonstrates that community health services are implementing strategies to manage outflow and provide access to more clients.

Figure 3B

Clients accessing CHP treatment

Note: The data range 11–370 is an aggregated figure.

Source: VAGO based on DHHS documentation.

DHHS's oversight of access at community health services

DHHS receives quarterly data from community health services on the number of service hours delivered in the CHP. Divisional offices use this data to assess whether community health services meet their targets, however, DHHS has no oversight of whether access is equitable. This is due to limitations in DHHS's performance measures and dataset, discussed in Part 4.

3.4 Demand in community health services

Measuring demand is important for the CHP—at a whole-of-state level, it allows DHHS to determine whether the CHP receives adequate funding and is meeting community needs.

DHHS's past and current demand measurement processes

Managing demand for the CHP is complex. There is no evidence that DHHS has undertaken any analysis of potential or hidden demand across Victoria. However, DHHS has recently commenced a demand forecasting project.

DHHS's oversight of current demand pressures is further limited, because the CHMDS contains incomplete and inaccurate data fields. For example, DHHS requires community health services to collect the concession card status of CHP clients, however, this field is blank or inadequately described in 44.5 per cent of records. This compromises DHHS's ability to understand whether community health services adequately manage demand to ensure that priority populations receive preferential and timely access to care. DHHS is undertaking a data streamlining project which it believes will support improved data collection practices by agencies. DHHS also does not collect waiting list data, which further limits its oversight of the state's demand pressures.

As discussed in Part 4, DHHS's key performance measure for the CHP focuses solely on the number of service hours delivered. Without further information, DHHS is unable to determine whether the CHP adequately services its priority populations with sufficient care, in the right place and within a reasonable time.

Action taken to improve DHHS's demand measurement processes into the future

DHHS has begun to evaluate demand in key catchment areas to address the gaps in its knowledge. For example, in August 2017, it produced a draft version of the Design, service and infrastructure plan for the Northern Growth Corridor. The report provides a high-level framework for planning in the northern growth corridor, which has experienced rapid population growth in recent years. The document profiles the catchment's diversity, service use, level of socioeconomic disadvantage, access to education, and prevalence of health risk factors, such as smoking rates. It aims to strengthen the northern growth corridor's existing healthcare network and enhance the flexible use of services to lessen disparities for disadvantaged Victorians. DHHS intends for future modelling to explore the rate of people moving into the area as well as projected use of services.

In addition, DHHS's System Intelligence and Analytics Branch has recently produced a project specification to understand how current and past investments in community health services have influenced activity patterns. It intends to use past activity data—2008–09 to 2016–17—and population estimates to gain insight into future activities and demand, and increase DHHS's knowledge of its clients. The document outlines a detailed methodology, identifies various risks, and assumes that no changes will be made to the CHP's funding formula. The project specification demonstrates DHHS's commitment to improving its oversight of demand pressures in community health services and is a step in the right direction.

Community health services' demand measurement processes

DHHS's demand management framework states that community health services should keep waiting lists to effectively manage their clients. The audited community health services all keep waiting lists and use these to monitor access. If possible, community health services avoid placing clients on waiting lists, as long delays can discourage and frustrate both parties. Waiting lists cause an administrative burden, as staff must generate acknowledgement letters, regularly maintain the waiting list, and conduct follow-up calls and status updates. Community health services have various strategies for managing demand, including:

- involving practitioners and clinicians in more detailed screening to ensure that clients are appropriately triaged, as this influences waiting times and the provision of effective care

- undertaking group therapy where clinically appropriate, for example, speech pathology for children aged five and under

- expediting access to speech pathology services for children about to start school.

DHHS acknowledges that funding for the CHP is capped, which has consequences for community health services' ability to manage their demand pressures. DHHS also acknowledges the significance of robust service planning and funding model development to support community health services to improve access for priority populations.

These funding constraints have consequences for community health services' ability to manage their demand pressures. For example, five community health services that we spoke to advised that they are unable to advertise their services or proactively seek clients, as they cannot provide care to all eligible people within the community.

Gippsland Lakes Community Health noted that in rural areas, people are under‑serviced and need is often only noticed when people travel to other areas to access service. Therefore, people in rural areas need services placed in locations where there is demand to improve access.

In addition, workforce retention rates also affect community health services' ability to meet demand. Sometimes, allied health professionals are difficult to recruit. Rural and remote community health services are affected by this more severely, as they are commonly the sole providers of allied health services in their communities. Such allied health positions may remain vacant for extended periods, which affects the community health service's ability to care for its local population.

For example, Orbost Regional Health has difficulty attracting allied health specialists—particularly physiotherapists—to its region, as it is in an isolated rural location. It often relies on graduate physiotherapists to fulfil its needs, however, most work for the community health service for only 12–18 months before leaving. When Orbost Regional Health is without a physiotherapist, it refers its clients to neighbouring services, such as Gippsland Lakes Community Health. The health service advised that this impacts access for its clients, as the region lacks regular public transport services.

To address this issue, Orbost Regional Health collaborates with different community health services across the region to share allied health specialists when they are in limited supply. For example, after the health service was unable to recruit a physiotherapist, it arranged for one from Bairnsdale to visit on a weekly basis so that its clients could continue to receive timely care. Sometimes, rural community health services—such as Orbost Regional Health —will fill service gaps with locums, however, this is an expensive option and is considered a last resort.

4 Performance and quality

Performance monitoring and reporting promotes transparency, good governance and effective management. It delineates the roles and responsibilities of agencies and is government's key accountability mechanism. Monitoring and reporting cycles require fair, relevant and consistent measures to effectively scrutinise performance.

DHHS collects data from various sources—such as feedback from staff and clients, clinical activity and local intelligence—to paint a picture of day-to-day performance at community health services.

In this part of the report, we examined whether DHHS's performance management system allows it to:

- demonstrate achievement of the CHP's objectives

- hold community health services accountable for their performance

- test and evaluate evidence-based strategies for broader policy-making within the sector

- improve the CHP and its service delivery model.

4.1 Conclusion

DHHS's performance management framework is unable to assess whether the CHP meets its objective of delivering effective healthcare services and support to Victoria's priority populations. DHHS lacks insight regarding the timeliness, equity, appropriateness or impact of care because its public and internal reporting largely focuses on the number of service hours that community health services deliver. To assess whether the CHP provides good healthcare outcomes for Victoria's priority populations, DHHS requires both quality-based and outcomes-focused performance measures.

DHHS is beginning to expand its oversight of the CHP through the client experience survey, which is a step in the right direction. While this tool provides insight into clients' experiences of the CHP and, by proxy, its effectiveness, the survey requires further research and evaluation to produce optimal results for the sector. In its current form, it has a low response rate, lacks the methodological rigour of tools used by better practice jurisdictions—such as New Zealand—and is long and cumbersome.

In addition, DHHS could improve its oversight of both registered and integrated community health services by standardising its existing monitoring procedures. DHHS uses the Funded organisation performance monitoring framework (FOPMF) to manage registered community health services, however, this is a relatively new tool and it is not consistently applied. DHHS's four divisions set their own monitoring regime for integrated community health services, which creates further variations in performance management.

4.2 DHHS's performance management system

As shown in Figure 4A, DHHS's performance management system has multiple layers—each with varying objectives. At both the state and agency levels, performance measuring, monitoring and reporting emphasise outputs rather than the effectiveness and impact of care.

Figure 4A

DHHS's performance management system

Source: VAGO.

4.3 State-level performance management

DHHS's public performance measures and reporting

DHHS sets public performance targets each year in the Victorian Budget Paper 3: Service Delivery (BP3). DHHS assesses the performance of community health care using six performance measures. As shown in Figure 4B, only two relate to the CHP.

Figure 4B

DHHS's BP3 performance measures for community health care

|

Performance measure |

Type |

Relevant |

|---|---|---|

|

Number of Better Health Channel Visits |

Quantity |

✘ |

|

Number of referrals made using secure electronic referral systems |

✔ |

|

|

Percentage of Primary Care Partnerships with reviewed and updated strategic plans |

✘ |

|

|

Number of service delivery hours in community health care |

✔ |

|

|

Percentage of agencies with an Integrated Health Promotion Plan that meets the stipulated planning requirements |

Quality |

✘ |

|

Total output cost |

Cost |

✘ |

Note: The performance measure for the number of referrals relates to all referrals made to community health services.

Source: VAGO, derived from BP3.

Two performance measures relate to the CHP, however, these both assess the quantity of care provided. DHHS lacks publicly available performance measures that specifically evaluate the quality, impact or cost of care.

DHHS's public reporting against performance measures

Figure 4C shows DHHS's publicly reported performance measures and performance for the CHP since 2014–15.

Figure 4C

DHHS's performance against targets for selected BP3 measures

|

Performance measure |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

2016–17 |

2017–18 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Target |

Actual |

Target |

Actual |

Target |

Actual |

Target |

||

|

Number of referrals made using secure electronic referral systems |

250 000 |

250 000 |

250 000 |

250 000 |

250 000 |

125 000(a) |

250 000 |

|

|

Number of service delivery hours in community health care |

988 000 |

1 055 000 |

988 000 |

1 062 000 |

1 000 000 |

1 101 000 |

1 015 000 |

|

(a) According to DHHS's 2016–17 Annual Report, this result is lower than the target due to a reduction in the number of electronic referrals made through the state system, following the introduction of additional referral portals associated with Commonwealth initiatives—My Aged Care and National Disability Insurance Scheme—that redirect flow to the Commonwealth systems.

Source: VAGO based on DHHS annual reports and BP3.

The Department of Treasury and Finance's performance management framework outlines the mandatory requirements for presenting and assessing performance information. According to the Department of Treasury and Finance, departments should 'develop performance measures that can demonstrate service efficiency and effectiveness, and cover all major activities of the output'.

DHHS's measures do not comply with this mandatory requirement, as they cannot determine whether the CHP fulfils these criteria. For example, DHHS does not publicly explain how or why the number of service hours changes over time. As a result, it is difficult for the public to assess whether annual fluctuations in service hours are due to improved efficiencies, over‑performance, or factors beyond the community health sector's control.

Likewise, current performance measures do not analyse the CHP's quality. While increasing the number of service hours may suggest that the CHP can support more clients, leading to better health outcomes, unless there is public assurance that care is high quality and effective, the program's achievements are unknown. Good measures of program effectiveness and quality generally include consultation with clients, such as analysis of client satisfaction surveys, as well as objective measures of health improvements. Importantly, this conforms to the sector's overarching philosophy of person-centred care and provides insight into the CHP's value.

In addition, while using the number of referrals made using secure electronic referral systems as a measure offers some insight into the program's efficiency, it is largely a comment on the sector's technical integration. As a measure, it is somewhat redundant, because the community health sector has continuously met DHHS's target since its introduction in 2011–12. The target of 250 000 has been precisely met every year except 2016–17, which raises questions regarding the accuracy of DHHS's reporting.

Last year, the sector only met 50 per cent of its target, however, this was due to the introduction of new referral portals at the Commonwealth level. DHHS noted it will reduce the 2018–19 target to 75 000 to reflect this change in referral pathways.

DHHS's internal performance measures and reporting

DHHS's internal reporting for the CHP uses the same performance measure—'the number of service hours delivered'. Community health services receive quarterly feedback from DHHS regarding their performance through the Funded Agency Channel. The Funded Agency Channel is a central platform that DHHS uses to convey information to community health services, such as procedural changes. DHHS's quarterly performance reports analyse the number of service hours that community health services have delivered against their prescribed targets. This quantitative review lacks supporting commentary and does not promote or encourage good practice.

In addition, this performance measure does not align with the program's objective—to provide effective healthcare services and support to Victoria's priority populations. According to DHHS's guidelines, effective care is culturally responsive, goal directed, health promoting and evidence based. However, the CHP's current external performance measure is incapable of reflecting these principles, because it lacks a person-centred focus and cannot determine whether care benefited the client. Likewise, as this measure fails to assess whether the CHP targets the right people, it does not encourage community health services to provide preferential access to Victoria's priority populations. Therefore, DHHS's internal reporting cannot determine whether the program meets its overall objective.

DHHS should consider implementing quality-based performance measures that assess client satisfaction following treatment, and outcomes-focused performance measures that assess self- and/or clinician-reported changes in health-related outcomes, behaviours and knowledge.

4.4 Action taken to address the gaps in current performance measures

In 2014–15, DHHS piloted the Victorian Community Health Indicators Project to strengthen the program's evidence base and foster a culture of continuous improvement. The project aimed to deliver two complementary suites of indicators—one focused on processes, the other on outcomes.

Process-based indicators evaluate the clients' administrative journey from entry to discharge, while outcomes-based indicators assess the impact of care. To date, DHHS has only completed its set of process-based indicators.

Process‑based indicators provide a particular view of service delivery, as they test the community health services' performance against DHHS's minimum requirements. Rather than outcomes, they enable community health services to assess a different aspect of care—its implementation—which reflects the client experience of service delivery. Process-based indicators represent better practice, as they conform to the sector's key strategic objective of person‑centred care.

DHHS's process-based indicators include measures such as:

- the percentage of clients with multiple or complex needs who have a care plan

- the percentage of complaints acknowledged by the organisation within twoworking days of receipt of the complaint.

In 2016–17, DHHS stopped collecting data against the process-based indicators due to feedback from the sector. While the indicators were positively received by community health services, they imposed significant administrative burden, as they required community health services to collect information that was supplementary to DHHS's standard reporting template. The sector's diverse range of client management systems was also an issue, as the necessary software updates were difficult and expensive.

To address this burden, DHHS is attempting to streamline the indicators' collection as part of its Community Health Data Alignment Project. DHHS has begun to embed the following five indicators into the CHMDS following consultation with the sector:

- timely initial needs identification

- interpreter use

- waiting time for highest-priority clients

- waiting time for mid-priority clients

- waiting time for lowest-priority clients.

DHHS advises that it will continue to consult with the sector as it integrates additional indicators into the CHMDS.

However, the absence of a complementary suite of outcomes-based indicators diminishes the project's overall value, as DHHS cannot conclusively determine whether the CHP provides effective health care to Victoria's priority populations. According to the Victorian Health Priorities Framework 2012–2022: Metropolitan Health Plan, poor care coordination increases the risk of poor outcomes for people with chronic disease. To analyse the relationship, DHHS requires information on both processes and outcomes.

4.5 Agency-level performance management across the sector

DHHS has four divisions—North, South, East and West. Each division operates several regional offices that are located across the state. Regional offices assign program advisors to the community health services within their jurisdiction. Program advisors are community health services' primary point of contact and carry out most of DHHS's monitoring duties.

DHHS's performance management system differs between registered and integrated community health services. DHHS's oversight of registered community health services is more rigorous than for integrated community health services, because the integrated health services are subject to the broader accountability systems of the hospital sector.

Agency-level monitoring considers community health services through a holistic lens and evaluates aspects of governance and management. It goes beyond program-level monitoring and assesses structural issues that may affect performance.

Monitoring of registered community health services

Every four years, DHHS sets a service agreement with registered community health services. This outlines the responsibilities of both parties to deliver high‑quality services and formalises their commitment to improving Victoria's health and wellbeing.

Through the service agreement, DHHS allocates funding to each program and stipulates any associated requirements. DHHS's regional offices use the FOPMF to assess whether community health services comply with their service agreements.

The FOPMF addresses the Minister for Health's gazetted performance standards, which are:

- governance—the agency must be effectively governed at all times

- management—the agency must be effectively managed at all times

- financial management—the agency must maintain effective financial management at all times

- risk management—the agency must effectively manage the risk associated with its business to ensure continuous, safe, responsive and efficient services

- quality accreditation and service delivery—the agency must demonstrate that it is able to meet quality and safety standards as established by an independent accreditation body.

The Victorian Government applies the FOPMF to various initiatives across DHHS and the Department of Education and Training—it is not specific to community health. FOPMF assesses foundational business elements, such as governance, safety and workforce arrangements. Program advisors may scrutinise the CHP's performance as part of the community health services' broader delivery platform, and some explicitly identify the CHP when assessing performance risks and issues.