Consumer Participation in the Health System

Overview

Consumers should be meaningfully involved in decision-making about their healthcare and treatment, and broader health policy, planning and service delivery.

There is genuine commitment and effort from the Department of Health (the department) and health services to facilitate meaningful consumer participation. The department has led implementation of consumer participation through strong policy direction and this has translated into appropriate policies, systems and activities in the four audited health services.

Implementing consumer participation is relatively recent and a challenging process, and health services do not always provide sufficient staff training, resources or support to integrate consumer participation across their organisation. Consequently, achievements both between and within health services vary. There are opportunities to enhance consumer participation at all levels, including better supporting consumers to understand and engage with basic health service information, and better involving consumers in organisational strategic planning and evaluation. This will become increasingly important as new national accreditation standards are implemented from January 2013, with significantly higher expectations and evidence requirements for consumer participation.

The department’s leadership has firmly placed consumer participation on the agenda of Victoria’s public health services. However, to further improve, the department needs to address gaps in its own implementation of consumer participation, provide better oversight of health services’ consumer participation activities and evaluate the impact of its main consumer participation policy.

Consumer Participation in the Health System: Message

Ordered to be printed

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER October 2012

PP No 180, Session 2010–12

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Consumer Participation in the Health System.

Yours faithfully

D D R PEARSON

Auditor-General

10 October 2012

Audit summary

Consumers should be meaningfully involved in decision-making about their health care and treatment, and broader health policy, planning and service delivery. There is growing recognition and evidence that consumer participation:

- positively influences an individual’s health outcomes if they are given quality information and are actively involved in decisions

- improves quality and safety by helping to design services that meet consumer needs

- provides feedback to drive service improvement

- enhances accountability by openly and transparently reporting on performance to consumers.

The audit assessed the extent to which the Department of Health (the department) and public health services facilitate meaningful consumer participation, including whether consumers are:

- supported to actively participate in their health care

- actively involved at the health service level

- actively involved at the departmental level.

Conclusions

There is genuine commitment and effort from the department and health services to facilitate meaningful consumer participation. The department has led the implementation of consumer participation through strong policy direction and setting clear expectations. This has translated into appropriate policies, systems and activities in the four audited health services.

The department and health services acknowledge the benefits of consumer participation in areas such as quality, safety and patient experience. There is evidence that having consumers on committees and working groups, and the use of consumer feedback have improved health service delivery, for example, in hospital signage, food services, information materials and physical facilities.

Implementing consumer participation in the health system is relatively recent and is a challenging process, and therefore, the achievements vary. The extent of consumer participation varies both between and within health services, as well as within the department. There are opportunities to enhance consumer participation at all levels, including by better supporting consumers to understand and engage with basic health service information, and better involving consumers in organisational strategic planning and evaluation. This will become increasingly important as new national accreditation standards are implemented from January 2013, with significantly higher expectations and evidence requirements for consumer participation.

The department and health services have a comprehensive range of policies and frameworks to support and encourage consumer participation. However, health services do not always provide sufficient staff training, resources or support for consumer participation to be successfully integrated into service delivery and improvement.

The quality and availability of information within health services varies considerably, as does the effectiveness of communication between consumers and staff. Consequently, while many consumers are supported to make informed decisions and participate actively in their health care, others are left as passive recipients of health services that are decided by medical and nursing staff. Health services recognise that there are also additional challenges in meeting the needs of those from culturally diverse backgrounds or with special needs.

The department’s leadership has firmly placed consumer participation on the agenda of Victoria’s public health services. However, to further improve, the department needs to address gaps in its own implementation of consumer participation, provide better oversight of health services’ consumer participation activities, and integrate consumer participation more broadly across the department.

The department requires health services to report on a range of consumer participation activities. However, it provides minimal feedback to health services about their performance. The department’s existing health service performance framework should better integrate consumer participation reporting. The department also needs to monitor and evaluate departmental consumer participation activities, continue to provide regular staff training in consumer participation and showcase successes across program areas.

Findings

Individuals’ participation in their health care

The department plays a major role in developing and disseminating consumer information, and assisting consumers to be actively involved in their health care. However, there is a gap in the availability of reliable, up-to-date information about common health issues in community languages.

Health services produce and disseminate a wide range of consumer information through brochures, posters, websites, patient information guides and visual display boards that outline service and quality. However, the quality and availability of consumer information was poor in one of the audited health services. Essential information, including service guides, patient rights and responsibilities, how to access an interpreter and how to provide feedback were not prominently displayed or readily available to patients throughout the health service.

Interviews with 52 patients across the four audited health services suggest that awareness and understanding of basic health service information is low. Health services need to increase efforts to disseminate critical information on rights, responsibilities and complaints processes through multiple and meaningful channels.

Each of the four audited health services had robust systems for collecting, reporting and addressing consumer feedback and complaints. This included: using a variety of formal and informal processes, capturing information on both compliments and complaints, seeking to resolve potential issues at the coalface, and reporting results at all levels of the organisation.

All four audited health services are making efforts to improve participation by diverse consumer groups. Examples include creating welcoming and culturally sensitive environments for members of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander community, multi-faith facilities, and improved access for people with disabilities.

Health services report a range of challenges in implementing their interpreter policies. They report that funding for interpreter services has not kept pace with consumer needs, demand has increased and there is a shortage of interpreters in some languages. Health services in rural and regional areas face additional barriers, such as a smaller local pool of accredited interpreters and increased travel time and costs. This issue warrants departmental review given the legal and ethical imperative to provide interpreters.

Consumer participation in health services

The audited health services have consumer participation frameworks in place, including documented policies and procedures and consumer representation on a range of committees and working groups. However, they are at varying stages of embedding consumer participation in organisational culture.

The audited health services are aware of the need to train staff at all levels of the organisation in consumer participation. They report that a major cultural shift, particularly among frontline clinical staff, is required to put consumer participation at the forefront of health care. Despite this awareness, two of the audited health services had inconsistent, ad hoc approaches to developing, implementing, monitoring and reviewing staff training in consumer participation.

Three of the four audited health services are legislatively required to have a community advisory committee (CAC) in place. The other, a small rural health service, has also elected to have a consumer liaison group.

The department’s CAC guidelines require CACs to develop a community participation plan (CPP) for approval by the board, and to monitor its implementation and effectiveness.

All three of the audited health services required to have a CPP have a plan with objectives, actions and time frames aligned to their strategic plan. However, some of the plans did not address all of the basic expectations set out by the department, suggesting that CACs and boards need to review their plans against the guidelines.

Health services report challenges in recruiting and retaining committee members who reflect the diversity in the local community, and/or building the capacity of members to operate at a strategic level. Committees also vary in the level of support they receive from health service boards and executive staff, and resources and guidance provided to support and focus their activities.

There is sound evidence of consumer input into health service decision-making at a program level at each of the four audited health services—for example, in improving individual clinical services. However, there is mixed success in involving consumers in strategic planning, staff training and health service performance monitoring, and little evidence of consumer participation in evaluation activities.

It will be challenging for many health services to meet the consumer participation requirements under the new National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards for health service accreditation. There is a significantly increased focus on consumer participation compared with previous requirements, as well as a more rigorous and robust assessment. Health services will need to address existing gaps in consumer participation activities to allow them to demonstrate compliance.

Consumer participation in the Department of Health

The department has provided strong policy direction for consumer participation through the 2006 Doing it with us not for us policy. This policy has a robust evidence base and was developed in consultation with consumers. However, the department has not fully evaluated its impact, nor planned to do so for the current version which expires in 2013. The department should review the status and usefulness of its policy within the context of the new national accreditation standards and the overarching Victorian Health Priorities Framework.

The department funds the Health Issues Centre and the Centre for Health Communication and Participation to progress research, health professional education, evaluation, and training in consumer participation. There is an opportunity for the department to address a current evidence gap by supporting research into the economic and health outcome benefits of consumer participation.

Departmental monitoring of health services’ compliance with consumer participation policy and reporting requirements is minimal. While the department acknowledges whether health services submit required tasks, its staff do not provide specific feedback to health services on the quality or appropriateness of their activities. There are also inadequate links between the assessment of consumer participation and the broader performance monitoring framework used to assess health services’ performance. Greater inclusion of consumer participation achievements in overall assessment would act as an important driver for improvement.

Recommendations

That health services:

- involve consumers in the design and review of consumer information

- make sure consumers receive and understand basic health service information

- review and improve service delivery for culturally and linguistically diverse consumers, including the provision of interpreters.

- That the Department of Health review interpreter services in the Victorian health system.

That health services:

- provide consumer participation training and development for clinical, middle management and executive level staff

- increase and diversify consumer participation in strategic planning, staff training, and evaluation activities.

That the Department of Health:

- integrate consumer participation across the department

- provide meaningful feedback to health services on reported consumer participation activities linked to their overall performance assessment

- evaluate the impact of Doing it with us not for us: Strategic direction 2010–13

- update its consumer participation policy and guidelines in the context of new national accreditation standards and the Victorian Health Priorities Framework.

Submissions and comments received

In addition to progressive engagement during the course of the audit, in accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 a copy of this report was provided to the Department of Health and four audited health services with a request for submissions or comments.

Agency views have been considered in reaching our audit conclusions and are represented to the extent relevant and warranted in preparing this report. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

All of us, at some time, interact with public health services, as patients, family members or carers. In 2011, Victorian public hospitals admitted 1.55 million patients, with a further 930 000 patients seen in emergency departments, but not admitted. In 2011–12, the Victorian Government spent just under $9 billion, 21 per cent, of its total expenditure on acute public hospitals. As consumers and funders of public health services, Victorians should be able to be involved in making sure this essential service meets their needs.

In this report, the term ‘consumer’ includes patients, carers and members of the local community.

Consumers should be meaningfully involved in decision-making about their health care and treatment, and broader health policy, planning and service delivery. There is growing recognition and evidence that consumer participation:

- positively influences an individual’s health outcomes if they are given quality information and are actively involved in decision-making

- improves quality and safety by helping to design services that meet consumer needs and providing feedback to drive service improvement

- enhances accountability by openly and transparently reporting on performance to consumers.

Consumer participation occurs at all levels of the health system:

- individual care—by being actively involved in their care and treatment

- health service—by having input into how health services operate

- departmental—by participating in policy development and program evaluation.

Traditionally, the health sector has seen consumers as passive recipients of health care. Implementing consumer participation is, therefore, an ongoing change process, requiring a cultural shift towards recognising the consumer as an actively engaged healthcare participant.

1.2 Policy and legislation

Charters, legislation and policy set out principles and expectations for consumer participation in health.

1.2.1 Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights

In 2007–08, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care developed the Australian Charter of Healthcare Rights. Commonwealth and state health ministers adopted the charter in July 2008. The charter applies to all Victorian health services, and includes consumer rights to:

- be shown respect, dignity and consideration

- be informed about services, treatment, options and costs in a clear and open way

- be included in decisions and choices about care provided

- comment on care provided and to have any concerns addressed.

1.2.2 Health Services Act 1988

The Health Services Act 1988 (the Act) is the primary legislation for health services in Victoria. The Act includes specific requirements relating to consumer participation in health. These are that:

- healthcare agencies are accountable to the public

- users of health services are provided with sufficient information, in appropriate forms and languages, to make informed decisions

- users of health services are able to choose the type of care most appropriate to their needs

- the board of a public health service appoints a community advisory committee (CAC).

1.2.3 Victorian Health Priorities Framework

The Victorian Health Priorities Framework 2012–22 is the government's overarching plan for the Victorian health system. It comprises the Metropolitan Health Plan, Rural and Regional Health Plan, and the, yet to be released, Health Capital and Resources Plan.

The framework has seven priorities—the first two relate directly to consumer participation:

- developing a system that is responsive to people’s needs

- improving every Victorian’s health status and health experiences.

Consumer participation is necessary to support other stated priorities, such as implementing continuous improvement, and increasing accountability and transparency. The framework plans make clear statements about consumer participation, including that:

- the government is committed to more and better information for patients

- patients should have the option to make choices about their care

- engaging local communities in the design and management of local health servicesis an important aspect of good governance

- more work needs to be undertaken to better understand patients’ current experiences and where there areopportunities for improvement.

1.2.4 Doing it with us not for us

In 2006, the Victorian Government released the Doing it with us not for us policy. The policy aims ‘for consumers...to participate with their health services and the Department of Human Services (now the Department of Health) in improving health policy and planning, care and treatment, and the wellbeing of all Victorians’. It provides strategic direction for consumer participation and a guide for participative actions.

The policy was updated in 2009, with the release of Doing it with us not for us: Strategic direction 2010–13. Five standards for consumer participation are included:

- the health service demonstrates a commitment to consumer participation appropriate to its diverse communities

- consumers are involved in informed decision-making about their treatment, care and wellbeing at all stages and with appropriate support

- consumers are provided with evidence-based, accessible information to support decision-making

- consumers are active participants in the planning, improvement, and evaluation of services and programs on an ongoing basis

- the health service actively contributes to building the capacity of consumers to participate fully and effectively.

Each standard is supported by priority actions and measurable ‘participation indicators’. The policy requires health services to report performance against each standard in their annual Quality of Care report from 2010–11. It also requires health services to develop and maintain a community participation plan.

1.3 Roles and responsibilities

1.3.1 Department of Health

The Quality, Safety and Patient Experience Branch within the department is responsible for implementing, managing and monitoring the Doing it with us not for us policy. This includes building the capacity of health services to implement consumer participation, and reviewing their performance. The department has a number of specific consumer participation activities.

Participation Advisory Committee

In 2006, the department established the Participation Advisory Committee. Its purpose is to advise the department on the implementation of Doing it with us not for us. The committee was involved in setting the standards and indicators in the 2010–13 strategic direction. Members include:

- consumers

- community representatives from CACs

- representatives from peak consumer groups

- representatives from health services

- a departmental staff member

- the Health Services Commissioner.

Victorian Patient Satisfaction Monitor

Since 2000, the department has contracted a company to administer the Victorian Patient Satisfaction Monitor (VPSM). The VPSM measures feedback from adult patients about their stay in Victorian public health services. The key VPSM measures are satisfaction, the overall care index (OCI), and the consumer participation indicator (CPI).

The OCI acts as the global indicator for the respondents’ hospital experience. It is made up of the scores from 25 of the VPSM survey items.

The CPI uses three VPSM survey items that measure patient satisfaction with the:

- opportunity to ask questions about their condition or treatment

- way staff involved them in decisions about their care

- willingness of hospital staff to listen to their health concerns.

The OCI and CPI scores for health services are published on the Victorian Health Service Performance website.

Under Doing it with us not for us, health services need to achieve a CPI of 75 out of 100. The department reports VPSM results annually and OCI and CPI results are included in the department’s performance monitoring framework for health services.

Supporting and promoting consumer participation

The department supports and promotes consumer participation by strengthening the evidence base and sharing knowledge across the sector. Such activities include:

- funding the Health Issues Centre to promote consumer participation, provide training and undertake research

- funding research by the Centre for Health Participation and Communication

- hosting consumer participation forums for health sector staff and consumers

- providing web-based and printed information and resources.

1.3.2 Health services

Victorian public health services have a range of consumer participation responsibilities set out in legislation, as well as policy and funding requirements. Figure 1A summarises key consumer participation responsibilities.

Figure 1A

Health service consumer participation responsibilities

Activity |

Description |

Requirement sources |

|---|---|---|

Community advisory committee |

Public health service boards must establish a CAC to provide direction, leadership and advocacy to increase consumer participation. |

Health Services Act 1988 Victorian health policy and funding guidelines Community advisory committee guidelines: Victorian public health services |

Community participation plan |

Shows how consumer participation will be integrated into health service operations, planning, and policy development. The plan is developed by the board in partnership with the CAC. |

Community advisory committee guidelines: Victorian public health services How to develop a community participation plan |

Quality of Care report |

Describes health service quality and safety systems, and outcomes to consumers. Report achievements against Doing it with us not for us participation indicators. |

Victorian health policy and funding guidelines Doing it with us not for us: Strategic direction 2010–13 Quality of care reports 2011–12 recommended reporting |

Complaint processes |

Health services are required to have effective and responsive complaints processes. |

Victorian health policy and funding guidelines |

Cultural diversity plan |

Aims to assure health services cater appropriately for culturally and linguistically diverse communities. |

Victorian health policy and funding guidelines Cultural responsiveness framework |

Key result area actions for the Improving Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Patients (ICAP) program |

Aim to improve identification, access, the cultural sensitivity of care, and participation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients. |

Improving Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Patients (ICAP) guidelines |

Mental health consumer and carer participation plan |

Aims to direct consumer participation within mental health services, including involvement of consumers in their treatment and care, and in the planning, development and evaluation of local mental health services. |

Strengthening consumer participation in Victoria’s public mental health services – Action Plan |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

1.4 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess the extent to which the Department of Health and public health services facilitate meaningful consumer participation, including whether:

- consumers are supported to actively participate in their health care

- consumers are actively involved at the health service level

- consumers are actively involved at the departmental level.

The audit assessed the department and a sample of four health services, including a metropolitan, regional and rural health service, and a specialist metropolitan hospital.

Additional stakeholder consultation included patient interviews, statewide surveys of CAC members and resource officers, CAC member and resource officer forums, and consultations with the Health Issues Centre and the Centre for Health Participation and Communication.

1.5 Audit method and cost

The audit was undertaken in accordance with section 15 of the Audit Act 1994 and the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. The total cost was $295 000.

1.6 Report structure

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 examines consumer participation in their own health care

- Part 3 examines consumer participation in health services

- Part 4 examines consumer participation in the Department of Health.

2 Individuals’ participation in their health care

At a glance

Background

Health services need to support consumers to participate in their health care to achieve better quality, safety and health outcomes. Consumers need to understand their health conditions, rights and responsibilities, and available care options.

Conclusion

The availability and quality of information within health services, and the effectiveness of communication between consumers and clinical staff vary considerably. Consequently, while many consumers are supported to make informed decisions and be active participants in their health care, others are left as passive recipients of health services.

Findings

- Only one of the audited health services has effective policies and procedures in place to involve consumers in producing and reviewing consumer information.

- Three of the four audited health services provide good consumer information, however, consumers still have low awareness of basic information.

- The health services are effective at gathering and responding to consumer feedback.

- Provision of translation and interpreter services is challenging due to limited funding and interpreter shortages.

Recommendations

That health services:

- involve consumers in the design and review of consumer information

- make sure consumers receive and understand basic health service information

- review and improve service delivery for culturally and linguistically diverse consumers, including the provision of interpreters.

That the Department of Health review interpreter services in the Victorian health system.

2.1 Introduction

Individuals have the right to be informed about and involved in decisions concerning their health care. This participation can lead to greater patient satisfaction and better health outcomes.

Recognising this, the Department of Health’s (the department) Doing it with us not for us: Strategic direction 2010–13 outlines five priority actions to support the effective participation of individuals in their health care:

- promote the rights and responsibilities of patients

- provide accessible information to consumers about health care and treatment

- communicate clearly and respectfully with consumers

- communicate and provide information about treatments and care to consumers that is developed with consumers

- listen and act on the decisions the consumer makes about their care and treatment.

This part examines how health services inform and communicate with consumers, and strategies used to meet the needs of diverse consumer groups.

2.2 Conclusion

The audited health services demonstrated a comprehensive range of policies and frameworks to assist consumers to participate in their own health care. However, the quality and availability of information within the audited health services, and the effectiveness of communication between consumers and staff vary considerably. Consequently, while many consumers are supported to make informed decisions and be active participants in their health care, others are left as passive recipients of health services that are decided by medical and nursing staff.

Consumer involvement in the audited health services was most meaningful where there were genuine partnerships between patients, their family or carer, and a multidisciplinary team of health professionals. This included structured and thorough admission processes to identify an individual’s needs and goals, and individual healthcare plans with clear, accessible language. It also involved consumer-friendly information being communicated through multiple channels, and consumers being openly encouraged to provide feedback to staff at all levels about their experience of the health service.

Areas where health services can improve consumer participation at the individual level include providing better access to interpreters, making sure patients receive and understand basic health service information, such as patient rights, responsibilities and complaints processes, and involving consumers in the development and review of consumer information materials.

2.3 Informing consumers

Health services have an obligation to inform consumers about their services, treatment options and costs in a way that consumers can understand. Health services need to make sure information is accessible and accurate and disseminated through multiple and meaningful channels. This may include face-to-face, written information, interactive media, and access to support services such as interpreters and translated materials.

Basic information to help consumers participate in their health care includes:

- patient rights and responsibilities

- quality and safety within the health service

- confidentiality and privacy

- full disclosure of costs

- how to access an interpreter or a support person such as a patient liaison officer

- compliments and complaints processes.

Health services typically provide this information through multiple sources such as patient information guides, brochures, Quality of Care reports, display boards and websites. The three larger audited health services also demonstrated effective use of volunteer guides to help consumers to access information or find their way around the hospital.

2.3.1 Consumer involvement in producing information

The department recommends in Doing it with us not for us: Strategic direction 2010–13 that ‘consumer involvement in the development of information can improve the clarity and relevance of materials’. Evidence of consumer involvement in designing information materials is an item included in the department’s Checklist for Assessing Written Consumer Health Information.

Three of the four audited health services did not have comprehensive policies and procedures in place to support this. They had, however, identified consumer involvement in producing information materials as a gap and were working towards addressing this. One health service had a Patient Information and Education Working Group to lead and advise on the production of consumer information. This health service had guidelines and an evaluation form to assist staff in developing appropriate patient information. It also trained consumers to review patient information, and had commenced reviewing all of its patient information.

2.3.2 Accessibility of basic consumer information

The quality and accessibility of basic information in three of the four audited health services was good. However, in one health service essential information about patients’ rights and responsibilities, how to access an interpreter, and how to provide feedback were missing from the emergency department, and not prominently displayed or readily available in other areas. Patient information guides were not available at bedsides in the medical or the rehabilitation wards, and staff did not know the procedures for addressing this issue. Additionally, the visual display boards providing information on services and quality were poorly positioned in busy corridors, and used complex language, diagrams and graphs.

While three health services had basic information available, it is not sufficient to simply rely on consumers accessing it themselves. Information should be provided at appropriate times throughout an episode of care, and frontline staff need to be proactive in making sure consumers have received and understood basic information.

The Victorian Patient Satisfaction Monitor (VPSM) is a six-monthly survey of patients at all public health services commissioned by the department from an external provider. Figure 2A shows that while the majority of respondents at audited hospitals in 2010–11 reported receiving information about patient rights and responsibilities, less than half reported receiving information about making a complaint. Significantly, the health service that did not have essential information readily available to consumers performed poorly in these areas, as shown in the results for Hospital 1.

Figure 2A

2010–11 patients provided with information on rights and

responsibilities, and complaints (per cent)

Hospital 1 |

Hospital 2 |

Hospital 3 |

Hospital 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Provision of patient rights and responsibilities information |

||||

Audited health service |

74.5 |

78.3 |

81.9 |

80.4 |

Other similar health services |

79.1 |

79.1 |

76.3 |

76.3 |

Provision of formal complaints information |

||||

Audited health service |

34.2 |

33.6 |

43.6 |

40.0 |

Other similar health services |

43.2 |

43.2 |

40.4 |

40.4 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on data from the Victorian Patient Satisfaction Monitor.

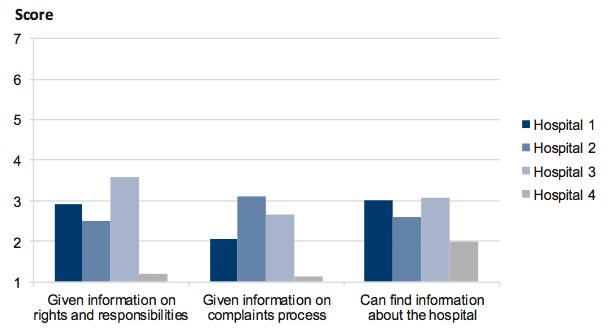

Interviews we conducted with 52 patients across the audited health services found that awareness of important information is low. Figure 2B shows that the interviewed patients consistently reported they had not received information about complaints processes and patient rights and responsibilities. They also reported they did not know how to find general information about the health service. Hospital 1’s poor performance again reflects the lack of information provided throughout the hospital. Hospital 4 in particular performed poorly in comparison to other hospitals.

Figure 2B

Average patient scores for provision of information on rights

and responsibilities and complaints

Note: Score: 1 = Completely disagree; 2 = Mostly disagree; 3 = Slightly disagree; 4 = Neither agree nor disagree; 5 = Slightly agree; 6 = Mostly agree; 7 = Completely agree.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

2.4 Communicating with consumers

Consumer participation goes beyond providing information. It also requires a two-way communication process, where the consumer provides input to decisions, and feedback on their experiences. Effective communication is critical through all stages of the consumer experience, from hospital admission, through to discharge and follow-up. Communication issues make up a substantial proportion of complaints made to health services, and are the basis for 10 per cent of formal complaints made to the Health Services Commissioner.

Frontline staff including nurses, doctors and allied health staff, have a major role in communicating with, and seeking feedback from consumers. Some of the effective means of communication seen at the audited health services included:

- hourly nursing rounds at three of the audited health services, providing more opportunity for interaction between nurses and patients

- use of whiteboards and communication books at one health service to facilitate two-way communication between patients, family members and clinical staff

- at two health services, a strong culture of empowering staff to resolve complaints directly and encouraging open disclosure of errors

- a personalised post-discharge information pack to assist ongoing treatment and recovery, including the individual’s health record, personal care plan, information about their health condition or medications, and relevant local support services and groups.

To create the Consumer Participation Indicator (CPI), the VPSM combines results from three questions—patient satisfaction with:

- the opportunity to ask questions about their condition or treatment

- the way staff involved them in decisions about their care

- the willingness of hospital staff to listen to their health care problems.

The department sets health services a target score of at least 75. Figure 2C shows that the 2010–11 mean scores for two of the audited health services are significantly above similar health services, while the mean score for one health service is significantly below similar health services.

Figure 2C

2010–11 Consumer Participation Indicator scores

Hospital 1 |

Hospital 2 |

Hospital 3 |

Hospital 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Audited health services CPI score |

80.2 |

81.4 |

84.7 |

75.6 |

Other similar health services mean CPI score |

80.4 |

80.4 |

78.4 |

78.4 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on data from the Victorian Patient Satisfaction Monitor.

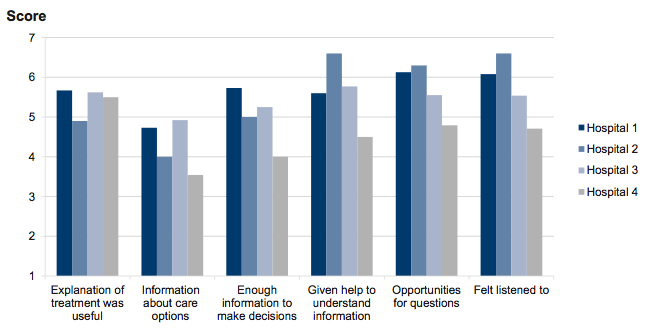

Across the four audited health services, patients were generally positive about the explanations provided about their treatment, their opportunities to ask questions and the support provided to understand their health care (see Figure 2D).

However, this was not the case for all patients, as shown in Figure 2E. This highlights the need for health services to routinely train staff in communication skills. Further, Hospital 4 again performed lower in both the VPSM results and the patient interviews conducted during the audit.

Figure 2D

Average patient scores from interviews at audited hospitals

Note: Score for item 1: 1 = Completely disagree; 2 = Mostly disagree; 3 = Slightly disagree; 4 = Neither agree nor disagree; 5 = Slightly agree; 6 = Mostly agree; 7 = Completely agree.

Score for items 2 and 6: 1 = Never; 2 = Very rarely; 3 = Rarely; 4 = Not sure; 5 = Sometimes; 6 = Often; 7 = Always.

Score for items 3, 4 and 5: 1 = Completely useless; 2 = Very useless; 3 = Useless; 4 = Neither useful nor useless; 5 = Useful; 6 = Very useful; 7= Extremely useful.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Figure 2E

Patient comments on communication with frontline staff

Positive comments:

- I gave feedback and it was responded to and modifications made.

- I was provided with information as well as going over things together.

Negative comments:

- There was too much information given all at once.

- I was unable to grasp the explanations given fully.

- I didn’t even know what or how to ask the doctors questions.

- There were no options, I was just told what was happening.

- Would be nice to talk to the doctors but they are often busy with students.

- Older people are not given the time... people who most need clarification are not given it, the nurses are in a rush.

- I would have liked more information about possible side effects.

- I was not offered an interpreter... would have been good to understand.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

2.4.1 Patient feedback

Consumers have a right to comment on their care, and to have any concerns addressed. Patient feedback provides health services with important and meaningful information to drive quality and safety improvements. It is important that health services offer consumers multiple opportunities and ways to provide feedback.

The VPSM includes a Complaints Management Index (CMI), made up of two questions addressing the ‘willingness of staff to listen to problems’, and how ‘staff respond to problems’. Figure 2F shows that in 2010–11, three of the audited health services performed similarly or better than similar health services, while one performed significantly below similar health services.

Figure 2F

2010–11 Complaints Management Index scores

Hospital 1 |

Hospital 2 |

Hospital 3 |

Hospital 4 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

Audited health services CMI score |

80.9 |

82.7 |

84.4 |

75.2 |

Other similar health services mean CMI score |

81.0 |

81.0 |

78.9 |

78.9 |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office based on data from Victorian Patient Satisfaction Monitor.

The four audited health services demonstrated effective patient feedback mechanisms. They each obtain feedback in a variety of ways such as directly through frontline staff, feedback boxes, surveys, senior management walk-throughs, patient liaison officers and post-discharge telephone calls. Three of the health services are in the process of considering, or rolling out new methods to collect ‘real-time’ information through hand‑held devices or computers in wards. The VPSM and complaints made to the Health Services Commissioner provide additional sources of information.

Each of the four audited health services demonstrated robust systems for collecting, analysing and reporting information about consumer feedback and complaints. The health services report patient feedback results at all levels of the organisation, including ward staff meetings, quality committees, executive management and the board, as well as to the community through annual Quality of Care reports. Senior management monitor trends in the data, identify follow-up actions and monitor their implementation. Examples from the audited health services include:

- introduction of secure storage for patients following incidences of lost or stolen property

- training or counselling for staff where complaints related to inappropriate manner or conduct

- re-timing of electronic doors to allow safe access for people in wheelchairs.

Importantly, two of the health services demonstrated a strong culture that staff should address any issues or concerns at the coalface. Typical complaints resolved in this way include patients disturbed by excess noise or not receiving their meal preferences.

2.5 Meeting diverse consumer needs

All health service users have a right to participate in their care. Health services therefore need to take account of the needs of vulnerable or disadvantaged groups, and those with particular needs, including some Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) people, culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) consumers, and people with a disability.

2.5.1 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander consumers

In 2004, the department introduced the Improving Care for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Patients (ICAP) program. The program aim is to improve accurate identification of and quality of care for ATSI patients. The ICAP program has four key result areas for health services that include establishing relationships with ATSI communities, staff cultural training, and addressing the cultural needs of ATSI people.

The audited health services have made sound efforts to improve participation by the ATSI community through ICAP plans. As a first step, they have improved the identification of ATSI patients through improved policies and data systems, staff training, and awareness-raising in the ATSI community.

Cultural symbols are important to create a welcoming and culturally safe environment for ATSI consumers. The most common examples seen at the audited health services were flying the ATSI flags, and displaying artwork and cultural artefacts, and a plaque recognising the traditional owners. Additional examples at some health services include celebrating major events such as National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee (NAIDOC) week, holding smoking and cleansing ceremonies, and allocating a space that meets the spiritual and cultural needs of ATSI patients, families, staff and community members.

The audited health services also employ Aboriginal Health Liaison Officers to support patients and families throughout their care journey, and promote links between the health service and local ATSI community. While health services often see these officers as an essential resource, it is important that the appropriate care of ATSI patients is the responsibility of everybody.

2.5.2 Culturally and linguistically diverse consumers

Individuals have a right to receive care that is responsive to their culture and beliefs. Examples include beliefs and practices around birth, illness and death, the gender of health professionals treating them, and dietary requirements while in hospital. Individuals also have a right to an accredited interpreter for communication with health services. This is also a legal imperative to assure informed consent to treatment.

Cultural responsiveness

Research within Australia clearly demonstrates the link between culture, language and patient safety outcomes. Some of the typical barriers CALD consumers may face when engaging with health services include:

- lack of familiarity with the local health system, services available and how to access them

- different concepts of health and illness which may affect understanding of treatment and impact compliance

- language and cultural barriers to understanding information, developing trusting relationships with health professionals, and providing informed consent

- lack of understanding of consumer rights and responsibilities.

For 2010–11, consumers with a language other than English (LOTE) gave an average VPSM score of 3.73 out of 5 in regards to whether the health service respected their cultural or religious needs. ATSI consumers scored this measure at 3.65. These results represent a range between good (3) and very good (4), but also leave room for further improvement.

Inclusive practice in care planning is one of six standards in the department’s Cultural Responsiveness Framework. This includes consideration of dietary, spiritual, family and other cultural practices. The department requires health services to develop a three-year cultural responsiveness plan that addresses the six standards, and to report against the plan annually in the health service’s Quality of Care report.

Each of the audited health services met the minimum requirements for this plan, with two exceeding them. Common activities contained in the plans, and implemented in the health services include cultural awareness training for staff, revisions to menus to account for religious and cultural needs, reviews of translated materials and information aimed at diverse groups, and activities to obtain feedback from CALD groups. The two exceptional plans identified a broader range of activities and included audits of complaints from CALD consumers and staff compliance with policies. They also clearly stated outcomes and accountabilities for tasks.

Language services

The department’s Cultural Responsiveness Framework also includes a standard that ‘accredited interpreters are provided to patients who require one’.

It is in the interest of health services to address language barriers as they can create increased costs through unnecessary procedures or increased interventions to rectify errors.

All four audited health services have a policy and procedures for accessing interpreters for LOTE consumers. However, one health service did not have information about how staff and consumers could access this service prominently displayed in public areas.

Health services experience a range of challenges in implementing their interpreter policies. Health services consistently report that funding for interpreter services has not kept pace with consumer needs, demand is increasing, and there is a shortage of interpreters in some languages. Health services in rural and regional areas face additional barriers in accessing face‑to-face interpreter services, such as a smaller local pool of accredited interpreters and increased travel time and costs. Health services also report a gap in the availability of reliable, up-to-date information about a range of health conditions and treatments translated into community languages.

Generally, LOTE speaking patients report significantly lower satisfaction scores in the VPSM. Some of the findings relating to LOTE patients in the 2010–11 survey include:

- 47 per cent said they were provided with information about how to make a formal complaint during their stay in hospital, compared with 51 per cent for English‑speaking patients.

- 42 per cent said that hospital staff encouraged their feedback, compared with 59 per cent for English-speaking patients.

- 12 per cent reported they had a reason to make a complaint, compared with 5 per cent of English-speaking patients.

These findings likely relate to language barriers experienced—this is supported by VPSM data on interpreter accessibility. The 2010–11 results found that 54 per cent of LOTE consumers wanted the hospital to provide an interpreter during their stay but only 35 per cent of these consumers reported access to an interpreter when they needed one. Of the others, 51 per cent had an interpreter ‘some of the time’, while 8 per cent ‘hardly ever’ had one, and 7 per cent ‘never’ had one.

The need to improve staff’s use of interpreters was a common issue identified by the audited health services in their cultural responsiveness plans. Given the ethical as well as legal obligations for interpreter use, health services should address this issue as a priority.

Additionally, the department needs to review the demand for interpreter services across Victoria and how well health services are meeting this demand. Without this understanding, the department is not well placed to determine appropriate funding levels, nor influence overall policy relating to the supply and use of interpreters in the delivery of public health services.

Recommendations

That health services:

- involve consumers in the design and review of consumer information

- make sure consumers receive and understand basic health service information

- review and improve service delivery for culturally and linguistically diverse consumers, including the provision of interpreters.

- That the Department of Health review interpreter services in the Victorian health system.

3 Consumer participation in health services

At a glance

Background

Consumers can make valuable contributions to health services beyond participation in their own care. They can also help to inform and improve services, facility design and the health service’s broader community engagement.

Conclusion

The audited health services recognise the benefits of consumer participation and have the necessary structures in place to support it. However, they are at varying stages of embedding consumer participation in organisational culture and are therefore achieving mixed success. There are opportunities to improve consumer participation policies and staff training, more fully support community advisory committees, and use consumer input more strategically at the organisational level.

Findings

- Two of the audited health services provide only limited staff training on consumer participation.

- Health services experience challenges in engaging consumers who reflect their community’s diversity, and building their capacity to contribute strategically.

- Community advisory committees face a number of challenges to their operation that require additional support and guidance from health services.

- Health services have significant work to do to meet consumer participation expectations in new national accreditation standards.

Recommendations

That health services:

- provide consumer participation training and development for clinical, middle management and executive level staff

- increase and diversify consumer participation in strategic planning, staff training, and evaluation activities.

3.1 Introduction

Consumer participation in health not only improves individual patients’ experiences of care, it can also assist health services to develop and improve their services, policies, strategies and facilities. The Department of Health’s (the department) Doing it with us not for us: Strategic direction 2010–13 identifies a number of priority actions for involving consumers within health services including:

- training staff in communication skills, how to involve consumers in decision‑making, and how to use the different types of participation

- involving consumers in activities such as:

- health service planning, development, monitoring and evaluation

- reviewing system-level issues regarding consumer feedback

- evaluating, monitoring and reporting on consumer participation to the community and the department.

This part examines the structures and processes health services use to embed consumer participation in their organisation, and how effectively they use consumer participation to improve services at the program, department, and organisational levels.

3.2 Conclusion

The audited health services recognise the benefits of consumer participation and have the necessary structures in place to support it. However, they are at varying stages of embedding consumer participation in organisational culture and, therefore, achieving mixed success.

All of the audited health services have overarching consumer participation policies, specific consumer committees, plans for consumer participation activities, include consumers on working groups, and involve consumers in capital projects. However, there is significant variation in:

- the comprehensiveness of their policies

- the extent to which they promote consumer participation through staff training

- the extent to which they engage consumers with the diversity and capacity to represent the community

- how they support and guide their community advisory committees

- how they involve consumers in strategic activities such as organisational planning and evaluation.

This will become an increased concern to health services as the new National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards are implemented from 2013. Expectations for high-level consumer participation, supported by evidence, are set to increase significantly.

3.3 Policies and training

Health services need to effectively communicate expectations for consumer participation to staff, and build their capacity to meet these expectations. Clear consumer participation policies and training opportunities are essential to embed consumer participation within organisational culture.

3.3.1 Consumer participation policies

All of the audited health services have an overarching consumer participation policy. Figure 3A shows that while the health services’ policies consistently promote the value and role of consumer participation, they do not all inform staff about ways to involve consumers, what they are expected to do, or how the organisation will evaluate consumer participation.

Figure 3A

Comparison of consumer participation policies

|

Features |

Health service 1 |

Health service 2 |

Health service 3 |

Health service 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Recognises participation at the individual healthcare level |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Recognises the role of consumers in improving planning and service delivery |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Recognises the role of consumers in monitoring and evaluation activities |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Specifies clear roles/responsibilities for staff at all levels |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Outlines different ways of involving consumers |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Specifies the aim to improve health outcomes for vulnerable/minority groups |

No |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Recognises the need to build the capacity of consumers |

No |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Outlines how consumer participation will be evaluated in the organisation |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Includes reference to the organisation’s consumer engagement/participation coordinator |

No |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Specifies links to accreditation standards |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

No |

|

Acknowledges links to government policies and research |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

In addition, one of the audited health services has a policy requiring consumer representation on all working groups. This sets clear expectations across the health service about the importance of gaining consumer insight when reviewing and improving services.

3.3.2 Staff training and development

All of the audited health services identified the need to develop consumer participation competencies among frontline staff, middle management and senior staff. However, only two demonstrated sound plans for implementing an appropriate training program.

These two health services demonstrated a strong commitment to an organisation-wide training program targeted to different staff and program area needs. Examples included orientation and ongoing training in communication skills, patient-centred values, and customer service techniques for frontline staff. One of these services had also trained over 300 staff in how to obtain and incorporate consumer input to the planning, development and review of services.

One of the other health services also demonstrated elements of appropriate training and development, while the fourth provided little evidence of staff development beyond that provided during initial orientation. This health service has included training activities in its community participation plan (CPP)—an annual plan outlining consumer participation activities—but has yet to implement them.

While better practice is to involve consumers in education programs for health service staff, both as participants and as presenters to share their experiences, there were only a few isolated examples of this across the four audited health services.

3.4 Community advisory committees

Consumers are involved in a wide variety of committees at the audited health services, covering areas such as quality and safety, population health, ethics and diversity. In addition, all public health services listed as such in Schedule 5 of the Health Services Act 1988, are required to have a community advisory committee (CAC). The Act also provides for the department secretary to set guidelines for the role and operation of CACs. These guidelines state that CACs have two roles:

- to provide direction and leadership to integrate consumer, carer and community views into all levels of health service operations, planning and policy development

- to advocate to the board on behalf of the community, consumers and carers.

3.4.1 Operation of community advisory committees

The operation, activities and effectiveness of CACs vary greatly across Victoria. This variation was a finding of a 2004 parliamentary inquiry into the operation of CACs, and the 2008 evaluation of CACs, commissioned by the department. While CACs continue to evolve, some are facing challenges in establishing and maintaining support at all levels of the organisation and/or attracting and retaining consumers with the required skills to contribute at the organisational level.

CACs have primary responsibility for developing a CPP for approval by the board, and monitoring the plan's implementation and effectiveness. The CPP should closely align to the strategic plan and address six areas, as set out in the department’s guide How to develop a community participation plan.

Figure 3B

Assessment of activities in community participation plans against expectations

|

Expectation |

Health service 1 |

Health service 2 |

Health service 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Strengths and limitations in consumer participation are identified and assessed and plans made to address these |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Education and training is provided to facilitate staff support of participation |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Participation is used to improve service planning and development to meet community needs |

Yes |

No |

Yes |

|

Service delivery to communities identified as hard to engage is enhanced through participation |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

|

Enhancement of care is facilitated through involving people in decision-making about their own care |

Yes |

No |

No |

|

Participation is used to improve the safety and quality of care provided |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Note: Only three of the audited health services are required to have a community participation plan.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

As shown in Figure 3B, the gaps in two of these plans suggest CACs and boards need to review their CPPs against the guidelines. Two of the three plans directly link CPP actions with the health services’ strategic objectives. One of the plans showed an enhanced level of accountability by identifying staff responsible for actions, time frames, and how staff will demonstrate success.

Support from the board and executive

Visible interest and support from the chief executive officer (CEO), management and the board are vital to the successful operation of the CAC. Both the 2004 and 2008 reviews of CACs highlighted the importance of this relationship. However, CAC members and staff of health services, and broader stakeholders still report a varying level of support from the board and senior executives for consumer participation and CACs. Figure 3C contains quotes from CAC members who responded to our statewide survey or took part in a face-to-face consultation.

Figure 3C

Community advisory committee member comments on their relationships with the board and management

Positive comments:

- It is very positive to have the CEO and board members on the CAC. I believe they give the CAC more credibility than it would otherwise have within the health service.

- We are valued and listened to by management. We are treated with respect and our opinions are heard respectfully.

- I am fortunate to be on a CAC that has very strong support from the CEO, the chairman and the board of directors. I believe their support has been crucial to the committee’s many successes and achievements.

- CAC input is becoming stronger and has a greater voice on the board than previously.

- The board is much more receptive to our feedback as time goes on, which is very rewarding.

- Excellent representation by board members at meetings.

Negative comments:

- It’s not always possible to know the outcomes of some CAC suggestions as they are forwarded to other committees, for example executive or governance.

- Management is going through the motions, as required by legislation, but nothing positive is being achieved.

- Their (executive staff) presence can shut down discussion and/or action on issues.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

There are different approaches across health services to determine who chairs CACs. Of the three audited health services required to have a CAC, only one has a consumer as the chair. This CAC demonstrated a high level of participation and confidence of their consumer members. Our surveys of CAC members and resource officers found that only a minority of CACs have a consumer as chair. While a board or executive staff member can chair a CAC effectively, it is important to mitigate any risk of inappropriately dominating consumer members and their input. Alternatively, where a consumer chairs the committee, it is important that the health service provides the necessary training to support them.

We also surveyed all CAC resource officers—the health service staff responsible for supporting the CAC. The majority of respondents identified that their CAC had ‘established relationships of trust and support between the CAC and the health service board and executive’. However, one-third identified that their CAC was still developing trusting relationships with the board. One commented that their executive sponsor had an inadequate understanding of, and lack of support for, consumer participation. Another said that changes in board membership had led to less interest and reduced linkages between the board and CAC. This feedback indicates that health services must work not just to establish, but also maintain relations between the board and management, and the CAC.

One of the audited health services is not legislatively required to have a CAC. However, through strong support and vision from the board and CEO this health service has a consumer liaison group which is chaired by a consumer. We observed mutual trust and a commitment from executive management to continue to develop members’ skills so they can participate in high-level strategic activities.

Resources

The CAC guidelines state that health services should allocate adequate funds for the implementation of their CPP, which the CAC helps to develop and monitor. However, resources vary significantly, reflecting varying support for consumer participation among health service boards and CEOs. This variation was evident across the four audited health services. Board members and senior executives at one health service report cost as a significant barrier to consumer participation and question the economic benefit of their investment. In contrast, the board and senior executives at another health service emphasised the importance of significant investment in consumer participation as it results in quality, safety and service improvements.

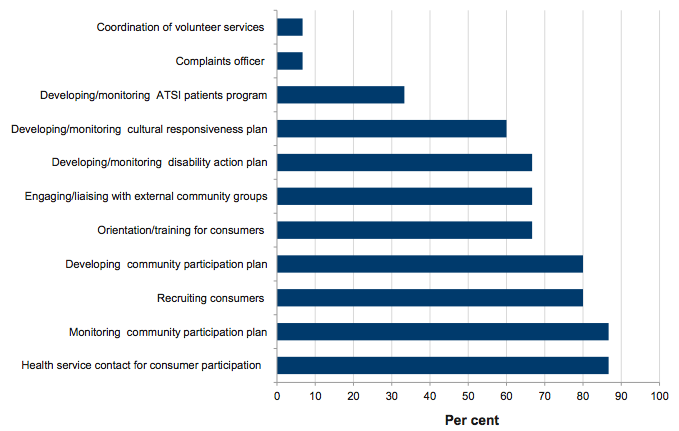

The CAC guidelines state that health services should appoint, where possible, an appropriately qualified community development officer to resource the CAC. This staff member should facilitate the CAC’s administration, undertake research, help to develop community networks, and draft submissions and responses on the CAC’s behalf. Our survey of the CAC resource officers found that they have vastly different roles and responsibilities, as shown in Figure 3D.

Figure 3D

Roles and responsibilities of community advisory committee resource officers

Source: Victorian Auditor General’s Office.

These varying roles reflect resource officers’ different time allocations and skill sets. Often resource officers carry a major role in coordinating and implementing consumer participation in the health services. Where resource officers have only a small proportion of the week dedicated to CAC and consumer participation activities, and/or have multiple roles, they are less able to do these tasks effectively. Over two-thirds reported they need additional training, often in critical areas such as community engagement, communication and leadership skills, project management, accreditation standards, research methods and design, and data analysis and reporting. However, they also reported that time and costs are major barriers to their participation in training and development.

Constraints and challenges

CACs face a range of constraints and challenges that typically reflect their stage of development, membership composition, and the profile and capacity of the local community. Lack of understanding of the role and activities of CACs, especially among middle management, frontline staff, consumers and community members is also a challenge for some health services.

Time constraints are a major barrier reported by executive staff, CAC members and resource officers. An overly ambitious workload can compound this. Additionally, over half of the resource officers responding to the survey reported that their CAC meets only the minimum recommended six times per year, or less. This is insufficient for consumers to build the required knowledge base, confidence and relationships necessary to participate fully in meetings and implement their agenda.

While health services are making efforts to improve participation by diverse consumer groups, this is significantly influenced by location and access to a diverse community. Many health services report difficulties recruiting males, people under 35, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander (ATSI) people, people with culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) backgrounds and people with diverse sexual orientations. Regional health services also report difficulties recruiting members from outlying areas.

Of the respondents to our resource officer survey, 64 per cent had no ATSI member, 43 per cent did not have a CALD member and half had no members aged under 35. This may reflect the characteristics of some health services’ local communities. However, many health services report they are trying to improve the diversity of their CAC membership and of consumer participants in other activities.

Recruitment of suitable members to CACs depends not only on the capacity of individuals within the local community, but also the recruitment methods chosen by the health service, and their approach to communicating the role and activities of the CAC within and beyond the health service. Additionally, health services will need to consider their CAC orientation program and ongoing training and support provided to consumers. Evidence from the audited health services, and our broader surveys and consultation found that orientation is rudimentary and training limited or non-existent in some health services. In contrast others have full-day orientation programs for consumers and volunteers, and extended mentoring programs.

Our survey of CAC resource officers identified the following topics as training priorities for CAC members:

- engaging local communities

- national accreditation standards

- cultural diversity and responsiveness

- general knowledge of the health sector.

3.5 Using consumer participation to improve health services

Consumer participation can assist health services to improve their operations. This occurs at the program or department level, referring to individual wards or areas of clinical service, for example an aged care ward, or elective surgery program.

Consumers can also provide valuable strategic input, for example, helping health services to understand and meet community needs, guiding major capital projects and guiding the health service’s future direction. This occurs at the organisational level and requires an enhanced level of consumer knowledge and capacity, which health services need to help develop.

3.5.1 Consumer participation at the program or department level

The audited health services consistently use and respond to consumer feedback to improve their operations, and provided numerous examples where they had involved consumers at the program or department level. In particular, aged care services and rehabilitation settings demonstrated service improvements based on consumer and carer feedback. The most common examples included improvements to food quality and information provision and, for aged care services, recreational activities and links with community organisations.

Consumer feedback on these issues is typically gained through residents’ and carers’ meetings, and informal feedback gathered through frontline staff. There were examples where staff had established project groups with consumer representatives to plan and implement service improvements, and then monitor and review the results. Figure 3E gives examples of how the audited health services have used consumer input to improve patient experiences.

Figure 3E

Consumer input to service improvement

Health service 1

This health service obtained feedback on the Outpatient Rehabilitation Services’ information pack from its Rehabilitation Consumer Reference Group. As a result changes included using simple language, new maps and a shorter, streamlined pack.

Health service 2

This health service established a consumer group to provide advice as it reviews and improves care coordination practices and systems. The consumer group has been consulted on:

- the naming of the new intake department

- the way the health service engages with its communities and consumer groups

- the development of a consumer brochure.

Health service 3

This health service is reviewing its processes for patients admitted for chemotherapy. This includes a survey of patients on their experiences from pre-admission through to discharge, and what patients value. It includes questions about information provided, whether staff checked that patients understood this and how well staff helped them to manage concerns. Staff will use this feedback to help map and then improve the patient journey from the patient perspective.

Health service 4

In response to complaints from consumers about the Emergency Department waiting room, this health service spoke to patients, two members of its CAC, and volunteers to identify improvements. Subsequently, seating arrangements were changed, the wall colour changed, and recliner chairs added to improve comfort for people with fractures. Additionally, the health service added a second triage nurse, trained volunteers to provide assistance in the waiting room, and now provides information on anticipated waiting times.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office.

Consumers can also provide valuable input to improve a health service’s physical environment. Consumer satisfaction with the physical environment is consistently one of the lowest scoring measures on the Victorian Patient Satisfaction Monitor (VPSM), particularly in large metropolitan hospitals.

The audited health services provided numerous examples where they used patient feedback, including the VPSM, to improve their facilities. Most commonly, this involved redesigning reception areas and waiting rooms, and reviewing hospital signage and patient information.

One health service demonstrated how they updated facilities to make them more welcoming and comfortable for diverse consumers using available information on consumer preferences. This included:

- colour-coded hospital signage and the use of international symbols

- improved disability access

- sensory gardens and relaxation rooms

- music therapy

- cultural and religious spaces.

3.5.2 Consumer participation at the organisational level

The CACs are the main mechanism for consumer input at the organisational level. However, health services may also employ dedicated consumer working groups for specific strategic initiatives such as a major capital project.

Strategic input from community advisory committees

Doing it with us not for us requires health services to consult with consumers in developing and reviewing strategic plans, service designs and CPPs. CACs are a key mechanism for achieving this. Common activities reported by CAC members and resource officers are:

- advising the board on consumer issues

- developing and monitoring the CPP

- input to the health service's annual report on care quality

- promoting the needs of vulnerable and marginalised consumers.