Early Years Management in Victorian Sessional Kindergartens

Snapshot

Does the Department of Education and Training support service providers managing sessional kindergartens to meet the outcomes of the Early Years Management Policy Framework?

Why this audit is important

In July 2016, the Department of Education and Training (DET) introduced the Early Years Management Policy Framework (the policy framework). The policy framework contains five outcomes that focus on improving early years services in Victoria. Studies show that quality early learning has a positive impact on a person’s schooling and adulthood.

Early Years Management (EYM) organisations run sessional kindergarten and long day care services. EYM organisations receive support from DET and additional funding from the Victorian Government to deliver services in line with the policy framework’s outcomes.

Who we examined

- DET

- five EYM organisations

- three local councils, one providing EYM services.

What we examined

- how DET has planned and implemented the policy framework

- how DET has supported EYM organisations and monitored their progress to meet the policy framework’s outcomes.

What we concluded

While DET and EYM organisations have made progress in implementing the policy framework, DET's support has not effectively assisted EYM organisations to meet its intended outcomes.

Due to its limited performance monitoring, DET does not know if EYM organisations are delivering services in line with the policy framework’s outcomes. This hinders DET’s ability to improve the quality of early learning services for Victorian children.

What we recommended

We made five recommendations to DET aimed at improving its performance framework and monitoring tools, clearly defining performance expectations, assessing if support addresses program challenges, and strengthening its continuous improvement processes. All our recommendations were accepted.

Video presentation

Key facts

What we found and recommend

We consulted with the audited agencies and considered their views when reaching our conclusions. The agencies’ full responses are in Appendix A.

The Early Years Management Policy Framework

The 'outcomes' stated in the Early Years Management Policy Framework do not describe the intended impact on early childhood education outcomes

An outcome measures the broader impact that a service has on individuals and the community.

The Early Years Management Policy Framework (the policy framework) introduced outcomes that the Department of Education and Training (DET) could use to consistently and transparently monitor the impact of the policy framework at an organisational and system level.

The policy framework’s 'outcomes', reflect DET’s primary focus on improving the delivery of the services that individual Early Years Management (EYM) organisations provide. As program objectives they are valid and meaningful. However, they are not truly 'outcomes' as the metrics DET uses largely measure inputs and processes. While the measures inform the user of whether elements of the policy framework have been implemented, they do not demonstrate what is being achieved as a result. Doing so would further strengthen the policy framework and allow it to clearly link to broader DET outcomes detailed in its 2016–20 Strategic Plan, such as:

- achievement—raise standards of learning and development achieved by Victorians using education, training, development and child health services

- engagement—increase the number of Victorians actively participating in education, training, development and child health services.

DET has not sufficiently developed its performance framework

DET developed the Outcomes and Performance Framework (OPF) to help it monitor EYM organisations’ performance against the policy framework’s outcomes. The OPF contains 31 measures to monitor the policy framework’s effectiveness at an organisational, regional and statewide level. This framework was released in draft in 2016 and the measures were identified as ‛sample‘ measures. DET planned to further develop the OPF as its use matured in consultation with the sector. However, it has not put the framework to use over the last four years, or further developed it with the sector as it intended.

In November 2019, DET started drafting the Monitoring and Improvement Framework (MIF). When finalised, this framework will replace the OPF and outline DET's new approach to monitoring performance and supporting continuous improvement in EYM services across the state.

Weaknesses in measure design

We primarily focused on assessing the OPF because the MIF is not developed enough to fully review. However, what DET has developed so far in the MIF has similar inherent design weaknesses as the OPF. We identified the following issues with how DET designed the OPF measures:

- Nearly all (26 out of 31) of the measures are process measures. This allows DET to know whether the policy framework is being implemented but not what is being achieved or the impact of it.

- DET has not established clear and practical measures for each of the policy framework’s outcomes to help it effectively identify improvements at an organisational level.

- The measures are not supported by enough information to enable DET to assess performance at an organisational, regional or statewide level.

- The design of some measures does not fairly assess performance. In other examples, the measure is not defined, which means it cannot be applied.

In addition:

- DET has not identified all of the data sources it needs to assess performance against the measures.

- DET has not established baseline levels for the measures to assess changes in performance over time.

Recommendations about performance measures

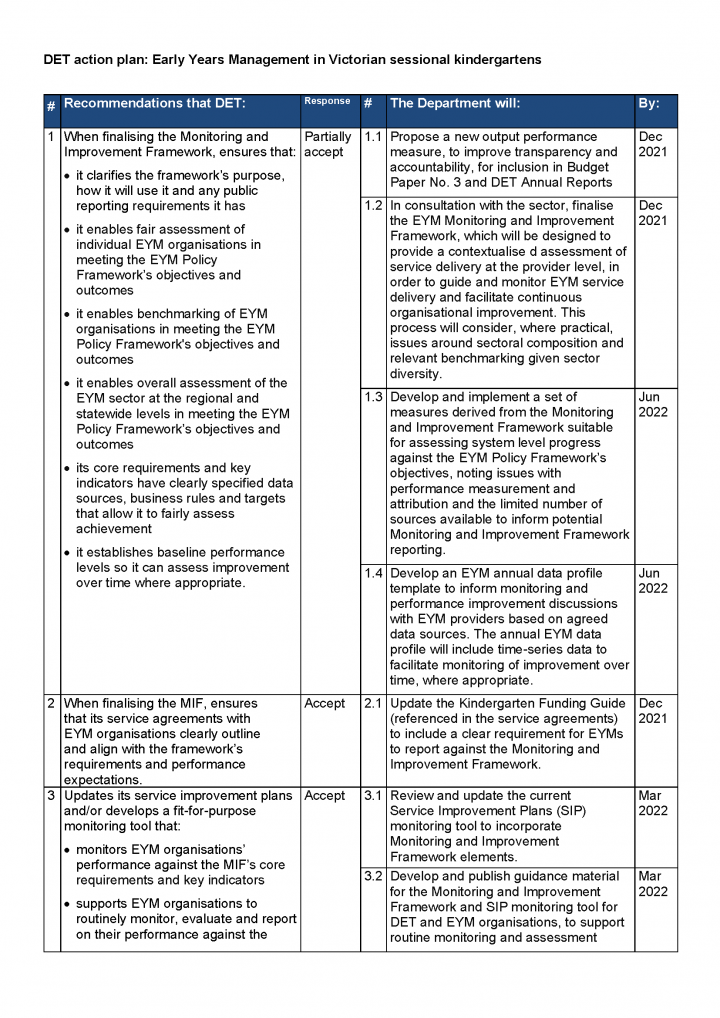

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education and Training | 1. when finalising the Monitoring and Improvement Framework, ensures that:

|

Partially accepted |

Reporting and monitoring

DET does not require EYM organisations to report on the measures

DET uses SIPs as the key monitoring tool for EYM organisations. However, SIPs are not used for all government-funded kindergarten services.

The Kindergarten Funding Guide gives kindergarten providers detailed information about the types of kindergarten funding available, how to apply for funding and eligibility criteria, and how to comply with operational requirements once DET has granted funding.

To date, DET has not required EYM organisations to report against the OPF’s measures. The routine reporting that EYM organisations complete aligns only with a limited section of the OPF. As such, DET has not used the OPF's measures to monitor EYM organisational performance against the policy framework. DET advised us that it takes a partnership approach to monitoring, which it does through its service improvement plans (SIP) that identify areas and actions for improving performance against the EYM outcomes. However, DET acknowledges the need to move towards a more consistent and quantitative assessment of EYM performance.

DET is ultimately accountable for ensuring that EYM organisations are delivering services in line with the policy framework’s outcomes. However, the standard service agreements that DET holds with EYM organisations, which reference the policy framework and Kindergarten Funding Guide, contain minimal information about how organisations should report on their performance against the policy framework's outcomes.

Limitations in DET’s monitoring processes

We reviewed DET’s monitoring processes for all government-funded kindergarten services and focused more specifically on how it monitors EYM organisations. We found that DET does not collate, analyse or report on the data it collects through SIPs, which is a missed opportunity to review and understand performance.

Recommendations about monitoring tools

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education and Training | 2. when finalising the Monitoring and Improvement Framework, ensures that its service agreements with Early Years Management organisations clearly outline and align with the framework’s requirements and performance expectations (see Section 2.4) | Accepted |

3. updates its service improvement plans and/or develops a fit for purpose monitoring tool that:

|

Accepted |

Assessing achievement against the policy framework

DET cannot link performance improvements to the policy framework

DET's EYM Kindergarten Operating Guidelines states that it would use the OPF to build a picture of the overall value and impact of the EYM program. However, we found that:

- DET does not assess how EYM organisations and services perform at a regional and statewide level despite having nine OPF measures designed for this purpose.

- DET undertakes limited analyses of the data and relevant performance information it does collect.

The inherent weaknesses in the outcomes DET defined in the policy framework and the design of the performance framework intended to measure the impact, mean that DET is unable to demonstrate:

- if any performance improvements are linked to the policy framework’s implementation

- that the support it provides to EYM organisations has led to any broader performance improvements at a regional or statewide level

- that its investment in the EYM program is generating positive results.

Gaps and challenges

DET does not have a comprehensive view of gaps and challenges

DET does not have a comprehensive approach to understanding the issues that EYM organisations experience while working to implement the policy framework. Across feedback provided by the six audited EYM organisations and the respective DET regional and area staff, we identified 20 common gaps and challenges that impact their ability to implement the policy framework, such as:

- difficulties in balancing the financial viability of individual kindergarten services with the financial viability of their service portfolios

- that the cost to attend sessional kindergarten services is becoming too high for some families

- ongoing difficulties recruiting and retaining a highly skilled workforce.

While DET provides a range of financial and non-financial support to EYM organisations, it cannot demonstrate that this effectively addresses the gaps and challenges that EYM organisations experience.

DET also could not demonstrate that the action it has taken on its investigations into challenges experienced by the sector is directly leading to improved support that addresses the issues.

Recommendations about support to EYM organisations

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education and Training | 4. routinely assesses if its support to Early Years Management organisations is addressing the underlying gaps and challenges they face in implementing the Early Years Management Policy Framework (see Section 3.1). | Accepted |

Continuous improvement

DET’s continuous improvement process is not aligned to achieving the outcomes

While DET has a continuous improvement process for individual EYM organisations, this process is aligned to implementing the policy framework, not assessing whether outcomes are achieved.

DET’s SIPs are used to capture a minimum of three improvement areas that EYM organisations self-assess and nominate each year with approval by regional staff. However, DET does not systematically capture improvements or necessarily align them with the OPF’s measures.

We reviewed DET’s continuous improvement process for individual EYM organisations and assessed how it informs broader improvements at a regional and statewide level. We found that:

- DET does not have a clear process for collating, escalating and addressing common areas for improvement at a regional and statewide level.

- There is a general lack of knowledge sharing across the sector and DET does not report on the data and information it routinely collects from EYM organisations.

- DET only captures examples of good practice at an organisational level and does not have a process to share these at a regional and statewide level.

Recommendations about continuous improvement processes

| We recommend that: | Response | |

|---|---|---|

| Department of Education and Training | 5. routinely captures improvements, gaps and challenges that Early Years Management organisations experience and:

|

Accepted |

1. Audit context

Quality early learning has a positive impact on a person’s schooling and adulthood. Recognising this, both the Victorian and Australian governments provide a significant amount of funding for kindergarten services.

In 2016, DET introduced the policy framework to improve kindergarten services across the state.

Starting in 2020, the Victorian Government is investing what will amount to almost $5 billion over the next 10 years to give children access to funded three-year-old kindergarten.

This chapter provides essential background information about:

1.1 Kindergarten in Victoria

DET is responsible for Victoria’s education system. This includes education within the early childhood education and care (ECEC) sector, which is referred to as kindergarten. Kindergarten is a program that qualified early childhood educators deliver to children in the years before they start school. Kindergarten helps children to develop social, emotional, cognitive and physical skills that are important to lifelong learning.

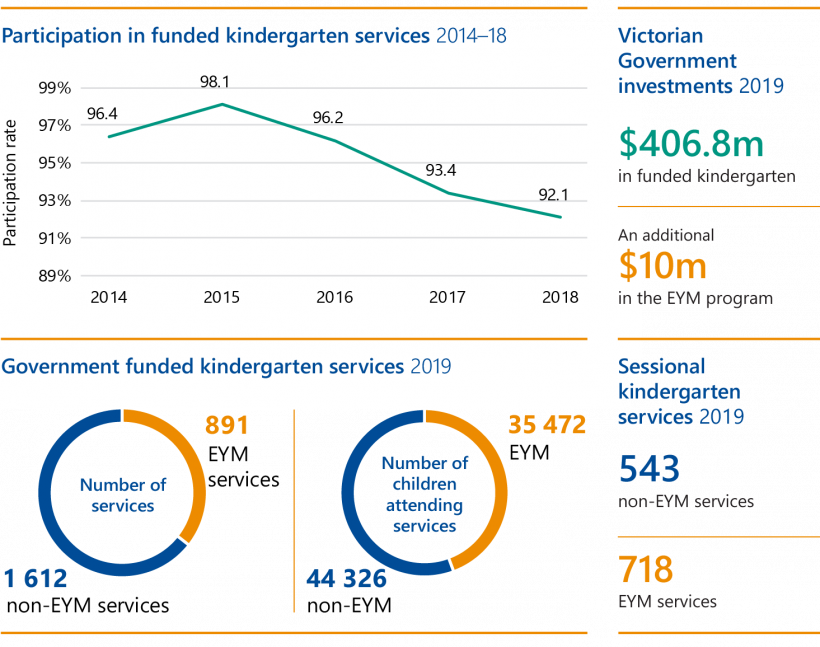

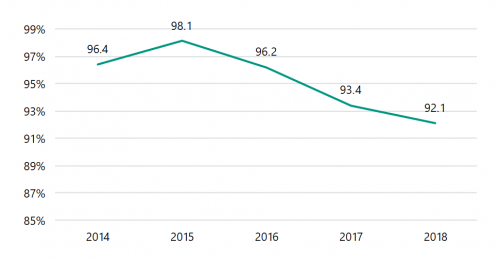

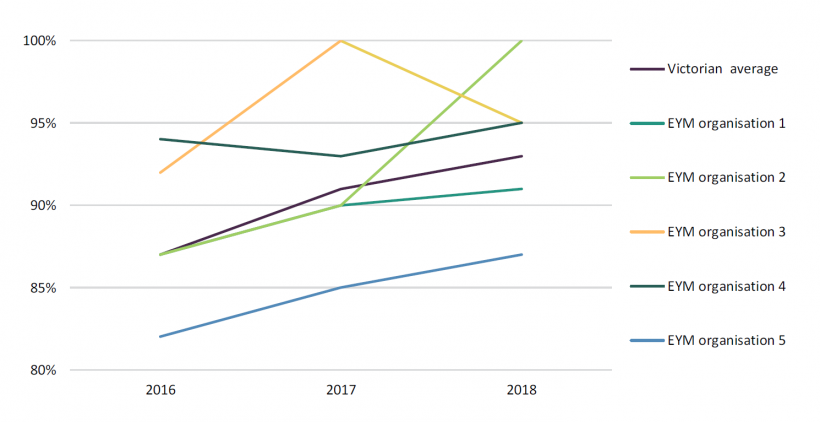

While kindergarten is not compulsory, most Victorian parents choose to enrol their children in it. In 2018, 92.1 per cent of Victorian children attended kindergarten in the year before starting school. Figure 1A shows participation levels for Victorian kindergarten from 2014 to 2018.

FIGURE 1A: Victorian kindergarten participation

Note: The participation rate is calculated by the number of children enrolled in their first year of state government funded kindergarten divided by a ratio of 70 per cent of four-year-old and 30 per cent of five-year-old children eligible to enrol, based on Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) population data. Participation rates are not directly comparable before and after 2016 because the ABS rebased their population data in 2016.

Source: VAGO, data from the Department of Education and Training 2018–19 Annual Report.

Government funding

The National Partnership agreement is a funding arrangement between the Australian and state governments to increase Australian children's participation in kindergarten programs.

Under the National Partnership on Universal Access to Early Childhood Education 2018–20, Australian children are funded to participate in 600 hours of a kindergarten program.

In 2019, the Australian Government contributed $123.9 million towards Victorian kindergarten programs and the Victorian Government provided $406.8 million. This funding is put towards:

- service and program delivery

- increasing access for children

- workforce-related expenses.

DET also provides additional funding for EYM organisations. In 2019, it provided $10 million to EYM organisations through the following grants:

- an annual grant ($10 232 per service)

- a one-off grant to start a new service ($3 070 per service)

- a one-off grant to establish a new EYM organisation ($5 000 per provider)

- a one-off grant to transition a service with complex financial or industrial issues to an EYM organisation ($3 070).

Eligibility for funding—kindergarten providers

To be eligible for government funding, kindergarten providers must meet eligibility criteria and operational requirements. For example:

- kindergarten programs must be planned and delivered by a qualified early childhood educator who is registered with the Victorian Institute of Teaching

- programs must have an educator to child ratio of 1:11 or less.

When a service is approved, kindergarten providers are eligible for funding per child and can also access a range of subsidies to deliver kindergarten programs to three and four-year-olds.

Eligibility for funding—children

Victorian children can currently access 600 hours of government-funded four year old kindergarten. To be eligible for full funding, children must be at least four years old on 30 April that year and enrolled in a kindergarten program that offers 15 hours per week. Vulnerable children may be eligible to access an additional year of government-funded kindergarten.

In 2020, the Victorian Government started funding three-year-old kindergarten in six rural local government areas. This funding, which is also provided per child, is being progressively rolled out up until 2029. This will allow Victorian children to access at least five hours of funded three-year-old kindergarten per week in 2022.

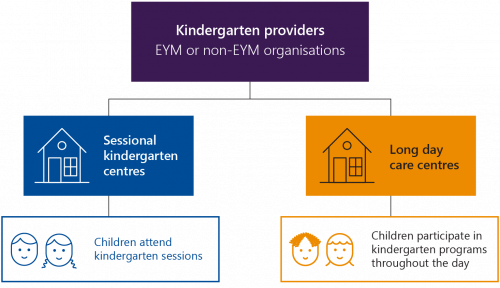

Types of kindergarten programs

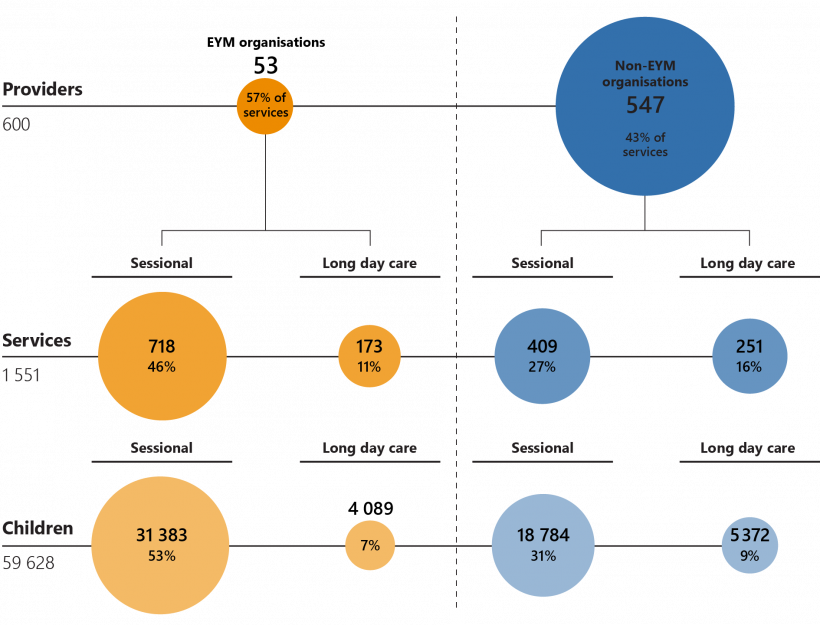

In Victoria, providers deliver kindergarten programs through sessional kindergartens and long day care centres, as Figure 1B shows.

FIGURE 1B: Kindergarten program delivery in Victoria

Source: VAGO.

As Figure 1C shows, sessional kindergartens and long day care centres differ in a number of ways.

FIGURE 1C: Key differences between the delivery of kindergarten programs

| Sessional kindergarten | Long day care centre | |

|---|---|---|

| Kindergarten program delivery method | Kindergarten programs are delivered through sessions. For example, three five hour sessions per week | Kindergarten programs are integrated with the long day care centre’s hours |

| Operating hours | Usually 9.00 am to 3.00 pm | Usually 6.00 am to 6.00 pm |

| Provider type | Predominately run by community not for profit (NFP) organisations | Predominately run by private organisations |

| 2019 attendance in Victoria | 69 per cent of all government-funded children | 31 per cent of all government-funded children |

Source: VAGO.

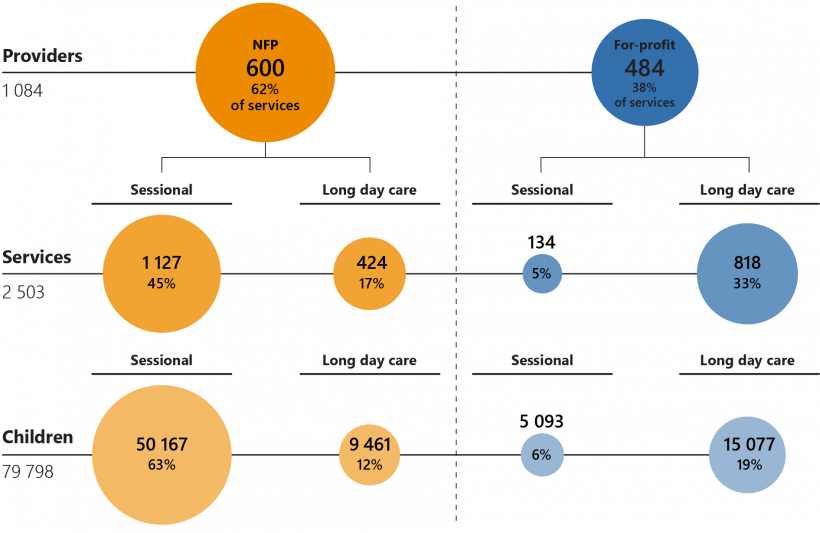

As Figure 1D shows, NFP organisations run more sessional kindergartens than private for-profit organisations.

FIGURE 1D: All funded kindergarten services in Victoria

Source: VAGO, based on 2019 Kindergarten Information Management System (KIMS) data from DET.

Kindergarten Cluster Management and the development of EYM

Traditionally, local councils and parents volunteering on committees of management (CoMs) operated Victorian sessional kindergartens. However, because of increasing time commitments and operational compliance requirements, some organisations started centrally managing clusters of kindergartens.

This approach was formalised by DET’s Kindergarten Cluster Management Policy Framework (the KCM policy framework) in 2003. Under the KCM policy framework, the cluster manager became accountable for delivering kindergarten services and complying with the relevant laws and regulations.

However, the KCM policy framework provided limited guidance on requirements, which resulted in varied management styles by cluster managers. While some cluster managers provided only administrative support to CoMs, others took on a greater responsibility, such as managing their staff's professional development and strategically planning for the cluster manager's long term sustainability.

In 2014, DET commissioned an evaluation of the KCM policy framework. The findings recognised a need for DET to clarify operational roles and responsibilities, particularly overlapping functions between EYM partners, and to mature the operational model. This led to the development of the Early Years Management Policy Framework.

1.2 The policy framework

In July 2016, DET introduced the policy framework to:

- outline its long-term vision for EYM services in Victoria

- provide greater clarity around the roles and expectations of EYM partners

- provide a sound basis for EYM organisations and partners to strategically plan how they deliver kindergarten services

- define outcomes that it can use to consistently and transparently monitor the impact of the policy framework at an organisational, regional and statewide level.

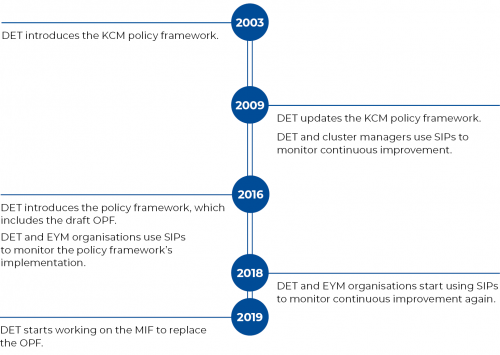

FIGURE 1E: Timeline of the policy framework’s development

Source: VAGO.

The policy framework’s vision and outcomes

DET’s policy framework envisions the EYM program to be a leading platform for achieving improved outcomes for all young children through world-class and accessible ECEC services.

As Figure 1F shows, the policy framework outlines five outcomes.

FIGURE 1F: The policy framework’s five outcomes

| Outcome | Description |

|---|---|

| Sustainable and responsive services(a) | EYM organisations are sustainable, viable and responsive to children, families and communities. They are built on strong and effective governance and partnership arrangements. The community has confidence in EYM. |

| Access and participation | EYM organisations drive high levels of participation for all children, in particular for those who are experiencing the highest level of vulnerability and disadvantage. |

| Quality and innovation | EYM organisations lead a world-class early years system in Victoria by implementing contemporary evidence based improvements in teaching and learning, and by sharing knowledge and experience with the broader sector. |

| Highly skilled, collaborative workforce | EYM organisations recruit, retain and invest in a highly skilled collaborative workforce. |

| Strong partnerships | EYM organisations collaborate with all EYM partners, community organisations, schools and other early years stakeholders to lead the development and coordination of quality services that improve outcomes for children. |

Note: (a)This is a foundation outcome. EYM organisations need to prioritise this outcome over the others.

Source: The EYM Policy Framework, DET.

Performance framework

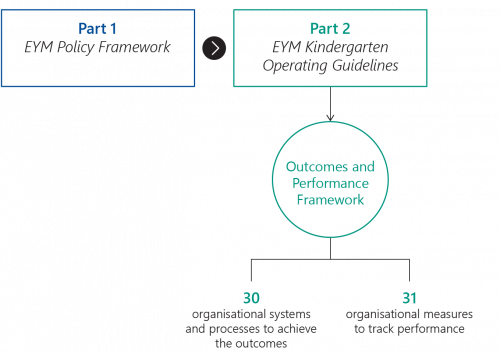

As Figure 1G shows, the policy framework has two parts—the EYM Policy Framework, which explains the EYM program’s background and context, and the EYM Kindergarten Operating Guidelines, which provides detailed operational information and processes for EYM organisations and partners. The EYM Kindergarten Operating Guidelines includes the OPF, which is the draft performance framework that DET intended to use to:

- monitor individual EYM organisations’ performance

- build a picture of the overall value and impact of the EYM program in Victoria.

FIGURE 1G: Parts 1 and 2 of the policy framework

Source: VAGO, based on the EYM Policy Framework and EYM Kindergarten Operating Guidelines.

DET intended to use the OPF’s 31 organisational measures, as outlined in the EYM Kindergarten Operating Guidelines, to evaluate if the policy framework’s intended improvements are occurring at each of the following levels:

|

Level |

Includes … |

|

organisational |

individual EYM organisations, including the services they operate |

|

regional |

EYM services collectively operating within each of DET’s four regions(a) |

|

statewide |

EYM services collectively operating across the state |

(a)Under DET's Learning Places model, the state is divided into four regions.

In November 2019, DET started drafting the MIF, which is a brief two page document that is based on the policy framework’s five outcomes. DET intends to replace the OPF with the MIF to help it and EYM organisations monitor their performance and identify areas for continuous improvement.

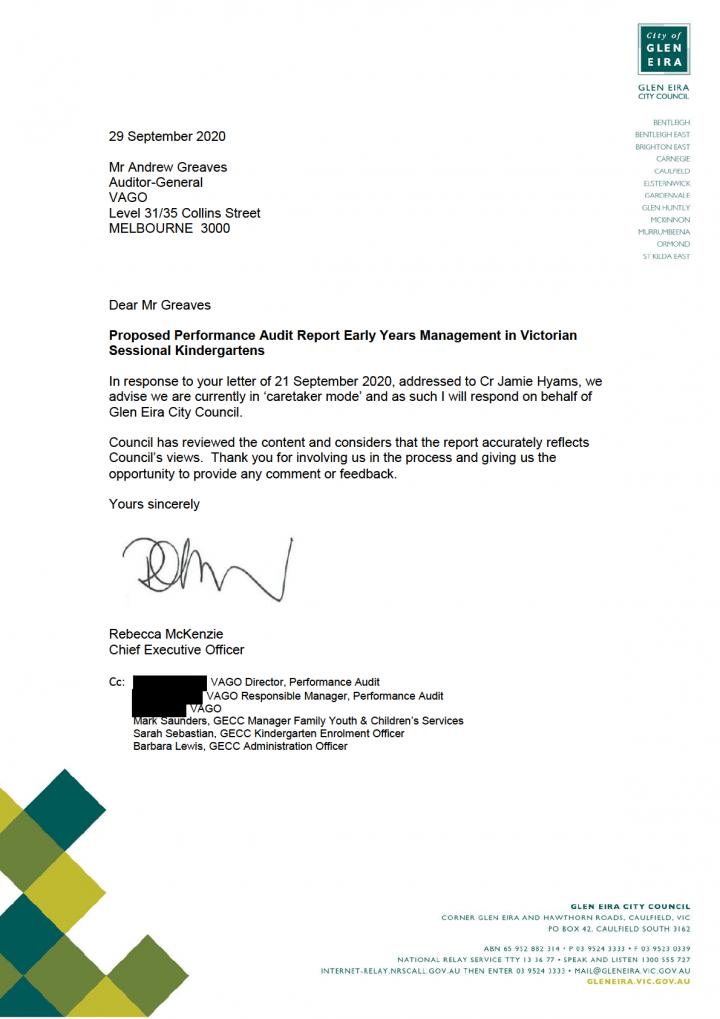

EYM organisations

Community-based NFP organisations and local councils are eligible to become EYM organisations. EYM organisations must operate at least three community-based services that offer a funded kindergarten program. Some EYM organisations operate more than 100 services.

Once approved by DET, EYM organisations are eligible for annual and one-off EYM grants and must meet operational requirements, including working towards meeting the policy framework’s OPF. EYM organisations provide leadership and management to the community-based kindergarten services and other early years services they operate.

As at December 2019, 53 EYM organisations operated 891 kindergarten services in Victoria. Of these services, 718 were sessional. As Figure 1H shows, this accounts for 46 per cent of government-funded NFP, community-operated kindergarten services. As shown in Figure 1D there are 134 sessional kindergarten services that are operated by for-profit providers.

FIGURE 1H: NFP, community-operated kindergarten services

Note: This assessment of services includes services operated by local councils.

Source: VAGO, based on 2019 KIMS data.

1.3 EYM roles and responsibilities

EYM partners

The policy framework relies on a four-way partnership model between DET, EYM organisations, local councils and families. EYM organisations operate EYM services and the other partners contribute to the quality of education and care.

DET

DET has a key role in overseeing, regulating and improving the ECEC sector. Its:

- Quality Assessment and Regulation Division (QARD):

- regulates ECEC services by administering and ensuring compliance with the Education and Care Services National Law Act 2010 and associated regulations, including EYM organisations and services

-

assesses and rates the quality of ECEC services in line with the National Quality Standard (NQS), including EYM services

The NQS sets a national benchmark for ECEC services in Australia. The NQS includes seven quality areas (QA) that are important outcomes for children.

- Early Learning Division (ELD) and the regions:

- administer funding according to the service agreements held with ECEC services, including EYM organisations

- support EYM organisations to meet the policy framework’s outcomes

- identify areas for continuous improvement in the EYM program at an organisational, regional and statewide level.

Local councils

Local councils plan for kindergarten infrastructure, can run kindergarten programs, provide council-owned buildings for community organisations to run programs in and may provide access to a central enrolment scheme for kindergarten services.

Families

As members of parent advisory groups, parent or guardian volunteers act as the voice of families whose children attend kindergarten programs, representing their interests in discussions with EYM services. Parent advisory groups contribute to their children’s educational experience by, for example, providing input into planning future services and negotiating responsibilities for fundraising.

All parents or guardians can provide feedback about the kindergarten programs their children attend either directly to the service or through surveys, such as DET’s annual parent satisfaction survey and service-run surveys.

Other key stakeholders and groups

Early Learning Association Australia

The Early Learning Association Australia (ELAA) is the national peak body for early learning. Their members include EYM organisations, local councils, and independent kindergartens and long day care centres. They have an advocacy role and provide support and advice through their work with Australian, state and local governments and other relevant organisations.

Municipal Association of Victoria

The Municipal Association of Victoria is the legislated peak body for local government in Victoria. DET has a partnership agreement with the Municipal Association of Victoria, which establishes each party’s roles in planning, funding and delivering a range of ECEC services.

Strategic Partnership Group and Forum

DET’s EYM Strategic Partnership Group (SPG) and EYM Strategic Partnership Forum (SPF) meet biannually. Members of the SPG include the Municipal Association of Victoria, ELAA and DET. Members of the SPF additionally include sector representatives from EYM organisations. The SPF supports DET in strategic planning, overseeing program performance and achievement and further developing the policy framework. It also provides input and advice to the SPG.

2. Setting and measuring against objectives

Conclusion

The EYM program is unlikely to reach its full potential while DET is not effectively overseeing EYM organisations to ensure that they are delivering quality services to young children, as envisioned in its policy framework.

DET is unable to measure the impact of the policy framework’s objectives because it has not set clear performance expectations for EYM organisations. There are also inherent weaknesses in the design of the policy framework’s OPF, and DET is not usefully collecting, analysing and reporting on the information it does have.

As a result, DET does not know if its investment in the EYM program is generating the desired results.

This chapter discusses:

2.1 The policy framework’s objectives

A program or service logic model is an essential part of planning, monitoring and evaluating a program. It gives the government and service providers a clear and shared understanding of how the program’s activities relate to its desired outcomes.

A service logic model also helps to identify how a program’s outcomes can be measured. This helps to establish clear performance measures that the government and service providers can monitor over time.

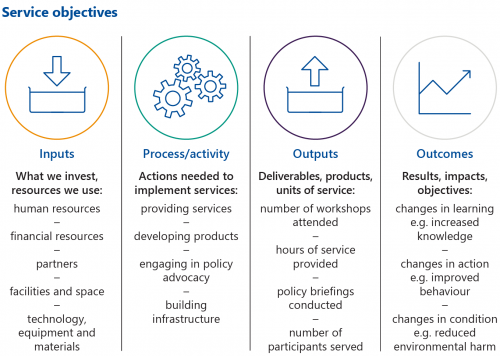

The Productivity Commission’s service logic model for government services

Each year, the Productivity Commission releases a report on the performance of government services across Australian states and territories. As Figure 2A shows, the Report on Government Services (RoGS) uses a service logic model to show how service providers transform inputs (resources) into outputs (services) to achieve their desired outcomes.

FIGURE 2A: The RoGS service logic model

Source: VAGO, adapted from the Productivity Commission’s Report on Government Services 2020.

Assessing the policy framework’s outcomes

We used the RoGS service logic model and definitions to examine the policy framework’s outcomes. As Figure 2B shows, the items that DET defined as EYM outcomes are a combination of inputs, processes, and outputs according to the RoGs service logic model.

FIGURE 2B: Our assessment of the policy framework’s outcomes using the RoGS service logic model

| Outcome | Service logic model component | Our analysis | |||

| Input | Process | Output | Outcome | ||

| 1 Sustainable and responsive services | |||||

| EYM organisations are sustainable, viable and responsive to children, families and communities. | ✓ | Focuses on the quality of kindergarten services delivered. | |||

| They are built on strong and effective governance and partnership arrangements. | ✓ | Focuses on the way that kindergarten services are delivered. | |||

| The community has confidence in EYM. | ✓ | Focuses on the way that kindergarten services are delivered. | |||

| 2 Access and participation | |||||

| EYM organisations drive high levels of participation for all children, in particular for those who are experiencing the highest level of vulnerability and disadvantage. | ✓ | Describes the participation levels of delivered kindergarten services. | |||

| 3 Quality and innovation | |||||

| EYM organisations lead a world-class early years system in Victoria by implementing contemporary, evidence based improvements in teaching and learning, and by sharing knowledge and experience with the broader sector. | ✓ | Focuses on the way that kindergarten services are delivered. | |||

| 4 Highly skilled collaborative workforce | |||||

| EYM organisations recruit, retain and invest in a highly skilled, collaborative workforce. | ✓ | Focuses on recruitment, retention and the human resource investment needed to produce kindergarten services. | |||

| 5 Strong partnerships | |||||

| EYM organisations collaborate with all EYM partners, community organisations, schools and other early years stakeholders to lead the development and coordination of quality services that improve outcomes for children. | ✓ | Focuses on the way that human resources produce kindergarten services. | |||

Source: VAGO.

Each represents a worthwhile objective where achievement is necessary to support the policy framework's outcomes. However, the metrics focus largely on measures of inputs and processes, which while informing the user of whether elements of the policy framework have been implemented, do not demonstrate what is being achieved as a result.

The policy framework also does not describe how its actions and objectives link to DET’s broader outcomes:

- achievement—raise standards of learning and development achieved by Victorians using education, training, development and child health services

- engagement—increase the number of Victorians actively participating in education, training, development and child health services

- wellbeing—increase the contribution education and training make to quality of life for all Victorians, particularly children and young people.

Developing a program logic model for EYM services when it developed the policy framework would have assisted DET to identify and address these gaps. DET drafted a program logic for its KCM policy framework; however, this does not represent a program logic for EYM as it does not fully align to the current policy framework and its outcomes.

2.2 The performance framework’s measures

The OPF has remained in draft form for four years. In response to issues identified in this audit and a 2019 report, commissioned by ELAA and funded by DET, that found scope for DET to better clarify how it assesses the policy framework’s outcomes, DET started developing the MIF to replace the OPF. DET has stated that the MIF will also help to clarify responsibilities and reduce the administrative burden for EYM organisations.

Differences between the OPF and the MIF

The key differences between the OPF and the MIF are:

|

The draft OPF outlines … |

The draft MIF outlines … |

|

the policy framework’s five outcomes |

the policy framework’s five outcomes (with minor changes) |

|

30 organisational systems and processes for EYM organisations to follow, use and report against |

27 core requirements that EYM organisations must meet and report against |

|

31 organisational measures that were intended for EYM organisations to report against |

20 key indicators that DET will annually collect and collate data for to inform its performance monitoring |

In February 2020, DET received ministerial approval to release the draft MIF for sector consultation. DET commenced this in late March with the Municipal Association of Victoria and ELAA. However, it postponed further consultation with the sector so it and other EYM partners could focus on responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. DET advised us that consultation will resume when the sector has the capacity to adequately engage in this process.

Weaknesses in the measures’ design

We primarily focused on how DET designed and implemented the OPF. This is because:

- it is the framework that DET currently uses

- the MIF is not developed enough to fully review

- DET is still finalising how it will use the MIF’s core requirements and key indicators to measure performance.

The measures are mainly processes

Processes are actions needed to implement services.

Output indicators measure how effectively, equitably or efficiently a service is delivered.

Outcome indicators measure the overall impact that a service has on individuals and the community.

As Figure D1 in Appendix D shows, DET developed the OPF’s 31 organisational measures to track EYM organisations’ performance. For example:

- organisational measure eight measures if EYM organisations have processes to regularly identify and manage risks, including compliance with the National Quality Framework

- organisational measure 13 measures if EYM organisations can demonstrate that they are complying with DET’s Kindergarten Funding Guide, especially regarding the Victorian Government's Priority of Access criteria

- organisational measure 23 contains human resources indicators, such as increased satisfaction with professional development, decreased staff turnover, and decreased use of agency staff.

As Figure 2C shows, nearly all of the OPF’s organisational measures are process measures when assessed against the RoGS service logic model. This means that DET can only learn whether the policy framework is being implemented and complied with, not what the EYM program is achieving. A program logic model would have assisted DET to identify a suite of balanced measures, including input, output and outcome indicators.

FIGURE 2C: OPF organisational measures sorted by RoGS service logic model components

| Service logic model component | OPF organisational measures |

|---|---|

| Input | 0 |

| Process | 26 |

| Output | 5 |

| Outcome | 0 |

| Total | 31 |

Note: Our detailed assessment of each organisational measure is included in Appendix D (Figure D1).

Source: VAGO.

The measures do not contain enough information

None of the OPF’s 31 organisational measures provide detailed guidance on how EYM organisations and DET should assess performance against them. As a result, EYM organisations do not know what they need to do to meet the policy framework’s outcomes, how they will know if they are making progress and how DET will assess their progress.

DET advised us that it designed the measures’ descriptions to explicitly contain the necessary information for EYM organisations to understand them. However, as Figure 2D shows, there are information gaps and statements in these descriptions that can be misinterpreted.

FIGURE 2D: Examples of how the OPF’s organisational measures can be misinterpreted

| OPF organisational measure number and description | Information gaps and misinterpretations | |

| 1 Sustainable and responsive services | ||

| Measure 3 | Quality and completeness of financial documentation, including the preparation of budgets and regular financial reporting. | Requires further information on:

|

| Measure 6 | An annual review of the strategic plan/growth plan, showing that the organisation operates in alignment with policy reforms and is well positioned to implement innovation. | Requires further information on:

|

| 4 Highly skilled collaborative workforce | ||

| Measure 21 | Participation by all ECEC professionals in professional learning programs that are linked to individual performance and development plans. | Requires further information on:

|

Source: VAGO.

It is important that DET's work to further develop the MIF establishes enough information to guide EYM organisations and DET regional staff on how to effectively monitor and analyse performance and what performance levels are expected, for example, through setting performance targets where relevant. This is also important for DET to ensure that its staff perform assessments consistently across its regions.

The measures might not fairly assess performance

We tested four of the OPF’s organisational measures with available performance data from DET and encountered several limitations. For example, some measures were difficult to apply, and some were not useful for fairly assessing EYM organisations’ performance. Three of the measures we tested are relevant to key indicators in the MIF and DET has retained one as a core requirement. Figure 2E outlines some examples of these limitations.

FIGURE 2E: Examples of limitations we identified when testing the OPF’s organisational measures

| OPF organisational measure number and description | Limitations | |

| 1 Sustainable and responsive services | ||

| Measure 7 | Desk top review indicates that the organisation is solvent and financially stable. | Measure 7 is not consistently used across all EYM organisations. Under the standard service agreement clauses used by DET, local councils are exempt from the desk top review process. This means that DET is unable to know if the financial viability of councils operating as EYM organisations is satisfactory and if the EYM services they operate are at risk of closure. |

| 2 Access and participation | ||

| Measure 10 | Increased participation of vulnerable children and their families, for example, the proportion of health care card holders accessing the service and the number of early start kindergarten (ESK) enrolments. | Measure 10 is not appropriate for assessing or indicating an EYM organisation’s performance. DET has not defined a method for calculating participation or stated if it is based on a rate, proportion or number of enrolments. Increased attendance numbers of children from families with health care cards does not indicate that an EYM organisation is actively striving to improve the participation of vulnerable children. Attendance numbers can be influenced by external factors, such as increased birth rates or demographic shifts in a local area, which do not reflect an EYM organisation’s performance. |

| 4 Highly skilled collaborative workforce | ||

| Measure 20 | 'Exceeding the NQS'. QA 1 (educational program and practice), QA 4.2 (staffing arrangements) and QA 7 (leadership and service monitoring) rated at 'exceeding the NQS'; proportion of QAs 4 and 7 that move from 'working towards the NQS' to 'meeting the NQS' or maintained at 'exceeding the NQS'. | Measure 20 is unclear and open to interpretation when applied. This measure appears to have three parts. However, this is open to interpretation. The final part of the measure—proportion of QAs 4 and 7 that move from the rating of ‘working towards the NQS’ to ‘meeting the NQS’ or maintained at ‘exceeding the NQS’—does not clarify what proportion is required. |

| Measure 20 does not cover all scenarios for improvement. This measure only includes two of the seven potential improvement scenarios that can be achieved by a service when its quality rating changes. |

||

| Measure 25 | Families' survey that shows an improvement in satisfaction. | The evidence that DET uses to assess performance against the measure is not reliable. Survey distribution is at the discretion of the EYM organisation or service, which introduces the risk of inconsistent distribution and non-response bias(a). DET does not have controls to manage non response bias and ensure that the survey is distributed equally to eligible parents or guardians. EYM organisations that have their own survey are also less incentivised to distribute DET’s voluntary survey. |

Note: (a)Non-response bias is when there is a significant difference between those who responded to the survey and those who did not.

Note: Three of the measures we tested are relevant to key indicators in the MIF and DET has retained one as a core requirement.

Note: Our approach to testing is detailed in Appendix D along with further examples of limitations.

Source: VAGO.

In the four years that DET has spent developing the OPF, it has not tested its organisational measures to determine if:

- they can be applied effectively

- the results appropriately and fairly represent performance.

It is important that DET tests the MIF’s core requirements and key indicators to determine their feasibility and confirm that the measures are logical, can be applied consistently and support measurements against the policy framework’s objectives.

The new performance framework lacks regional and state measures

In the OPF, DET clearly links nine organisational measures to the EYM program’s performance at a regional and statewide level, which should allow DET to conduct statewide assessments. However, the draft MIF only focuses on performance at an organisational level.

It is important that DET monitors and understands performance at all levels of the EYM sector so it can identify systemic issues that need addressing and areas for improvement. To form a view of the EYM program at the regional and statewide levels, DET should use dedicated measures for this purpose or make a clear commitment to compile individual EYM organisations’ results.

Statewide, regional, and benchmarked performance reporting could also help individual EYM organisations understand their performance in relation to the sector and similar organisations to identify areas for improvement.

2.3 Implementing the performance framework

While DET acknowledges that it has not implemented the OPF in a systematic and comprehensive way, it believes that what it has applied has served an important role. In particular:

|

DET has used components of |

DET believes this has … |

|

monitor how EYM organisations have implemented the policy framework |

supported EYM organisations’ change management approach and guided EYM organisations and partners to understand DET’s expectations |

|

focus EYM organisations’ reporting on changes they have made to their service delivery |

helped EYM organisations align changes to their service delivery with the policy framework’s requirements |

|

assist with communicating the common purpose and specific roles that each partner plays in EYM delivery |

established a shared and common focus for EYM partners |

One out of the six EYM organisations we audited has used the OPF’s organisational measures to informally align its daily operations with the policy framework. While all audited EYM organisations apply parts of the OPF through the SIP process (see Section 2.4), DET has not used its measures to monitor performance and improvement across the sector. DET therefore cannot demonstrate whether the policy framework has supported EYM organisations to enhance their services. However, DET intends to start formally monitoring using the MIF’s core requirements and key indicators.

Implementation issues

DET has not identified all required data sources and information collection processes

DET did not identify all of the data sources needed to assess the OPF’s organisational measures. In some cases where it identified the data source, neither DET nor EYM organisations have a system or process to collect the data. Figure 2F provides more information about these issues.

FIGURE 2F: Data sources and collection processes for OPF measures

| Measure type | Required data source identified | Data collection system/process in place for DET | Data collection system/process in place for EYM organisations | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational | 25/31 | 23/31 | 23/31 | Required data sources are not identified for 21 per cent of measures. |

| Regional and statewide | 9/9 | 9/9 | 9/9 | Required data sources are identified for all measures. |

Note: See Figure F1 in Appendix F for more information.

Source: VAGO.

As it finalises the MIF, DET should clarify the data sources and fields it needs to effectively complete assessments. It should also determine if there are systems and processes for collecting data currently in place or if new collection methods are required.

DET did not establish baseline levels for the measures

An accurate baseline or starting point is essential to measure performance and improvements over time. However, DET did not establish baseline levels for any of the OPF’s organisational measures and has not been establishing them for the draft MIF’s core requirements and key indicators.

Since introducing the policy framework in July 2016, DET has been actively collecting data through the routine funding and compliance monitoring it conducts of all government-funded kindergarten services. Some of these data sources are relevant to the OPF’s organisational measures and the MIF’s core requirements and key indicators.

ACECQA collects and holds data about kindergarten services in Victoria. It updates this information daily.

For example, DET has access to the Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority’s (ACECQA) data for all EYM services relating to:

- educational programs and practices

- staffing arrangements

- leadership and service monitoring.

DET could use this data to establish baseline levels and determine desired performance targets for relevant measures.

2.4 Reporting and monitoring

The policy framework does not clearly detail the performance reporting requirements and expectations for EYM organisations.

Reporting requirements and expectations

To date, DET has not required EYM organisations to report against the OPF’s 31 organisational measures. DET released the OPF in draft and identified the measures as sample measures. DET planned to further develop the OPF as its use matured in consultation with the sector. However, DET has not put the OPF to use, matured its use over the last four years or further developed it with the sector.

DET is ultimately accountable for ensuring that EYM organisations are delivering services in line with the policy framework’s outcomes. However, the standard service agreements that DET holds with EYM organisations, which reference the policy framework and Kindergarten Funding Guide, contain minimal information about how EYM organisations should report on their performance against the policy framework's outcomes.

Reporting for EYM organisations

Regardless of their EYM status, all government-funded kindergarten services must meet compliance and operational requirements, including routine reporting to DET relevant to the funding they receive. EYM organisations also receive a range of EYM grants and have additional routine reporting associated with this funding.

DET primarily uses SIPs to manage this EYM reporting. In the two years following the policy framework’s release in July 2016, DET monitored the progress of EYM organisations in implementing the policy framework.

During this implementation phase the SIPs were initially focused on the OPF organisational systems and processes and did not include organisational measures. EYM organisations completed SIPs quarterly with the assistance of early childhood performance and planning advisors (ECPAPA). To do this, they listed the actions they had completed against 23 of the 30 OPF organisational systems and processes.

Over time the SIPs became less focused on the OPF organisational systems and processes. In the second year of implementation EYM organisations were required to report on only 10 out of the 30 OPF organisational systems and processes. DET advised us that the SIP will be further updated to align to the core requirements and key indicators in the MIF once it is finalised and approved for use.

DET also used the SIP to monitor EYM organisations’ continuous improvement activities, which we discuss in Section 3.2.

Limitations in DET’s monitoring and reporting processes

Reporting requirements are high

EYM organisations’ reporting requirements should not outweigh or substantially consume the EYM grant funding they receive to deliver and improve EYM services.

As stated earlier, the draft MIF has 27 core requirements and 20 key indicators that DET proposes EYM organisations report on. While this is lower than the OPF’s 30 organisational systems and processes and 31 organisational measures, it is still a relatively large framework to implement and monitor. This is particularly problematic because the framework does not have output or outcome measures to give DET a clear insight into whether its policy framework is working.

This issue is further compounded by the MIF’s core requirements being similar to the OPF’s organisational measures, and therefore having the same inherent design weaknesses we discuss in Section 2.2.

DET needs to determine if implementing all of the MIF’s core requirements and key indicators is an efficient way to measure the EYM policy’s success.

Collection tools are not fit-for-purpose

DET advised us that its main barrier to collatng and analysing the data and performance information it collects through SIPs is the static nature of the template itself and the supporting documentation that EYM organisations provide.

ELD collects EYM organisations’ SIPs and supporting documents through its online portal, but it does not analyse this data and performance information. DET’s last systematic review of information it collected through SIPs was in 2012, which is four years before it introduced the policy framework.

2.5 Assessing achievement against the policy framework’s outcomes

According to the EYM Kindergarten Operating Guidelines, DET was to use the OPF to build a picture of the overall value and impact of the EYM program in Victoria.

However, DET cannot determine that individual EYM organisations are meeting their performance obligations, or that its investment in the EYM program is generating the desired results. Further, without reliable performance data, DET cannot hold organisations accountable for delivering quality services to young Victorians.

DET’s inability to review the EYM sector’s performance is partly due to the OPF’s draft status. DET has also not applied the OPF as it intended to systematically and comprehensively assess performance across the sector.

Limitations in DET’s assessment processes

DET cannot determine the EYM policy’s impact

DET currently does not know if EYM organisations’ performance has actually improved, if any improvements are linked to the policy framework’s outcomes and what the impact of this is, for example, improved education outcomes for young children.

There are nine measures in the OPF that can be used to determine EYM organisations’ collective performance at a regional and statewide level. However, DET has not undertaken an assessment against these measures. This means that DET cannot demonstrate the EYM policy’s impact in Victoria, including understanding and comparing the performance of EYM and non-EYM providers and services.

DET does not assess available data and performance information

DET undertakes limited analyses of the data and performance information it does collect to inform its performance assessments of EYM organisations.

Through the existing funding and compliance monitoring it conducts for all government-funded kindergarten services, DET collects around 79 per cent of the data it needs to assess performance against the OPF’s organisational measures.

DET could, for example, assess ACECQA data, which rates the overall quality of government-funded kindergarten services in Victoria. This data relates to the ‛exceeding the NQS’ ratings for organisational measures 11 and 17 in the OPF.

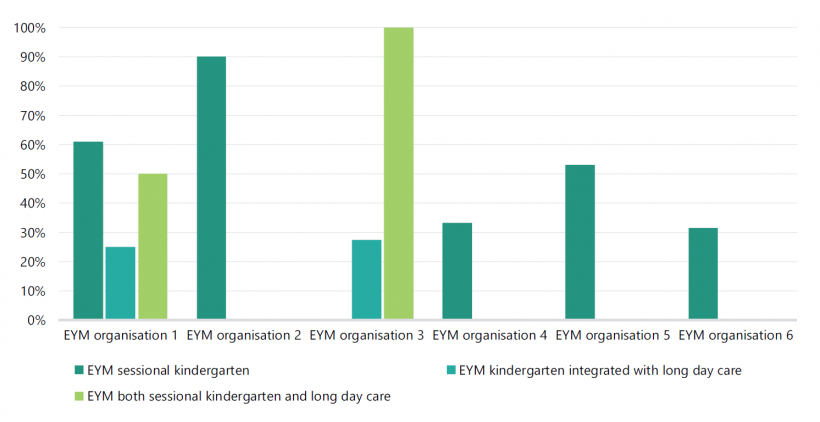

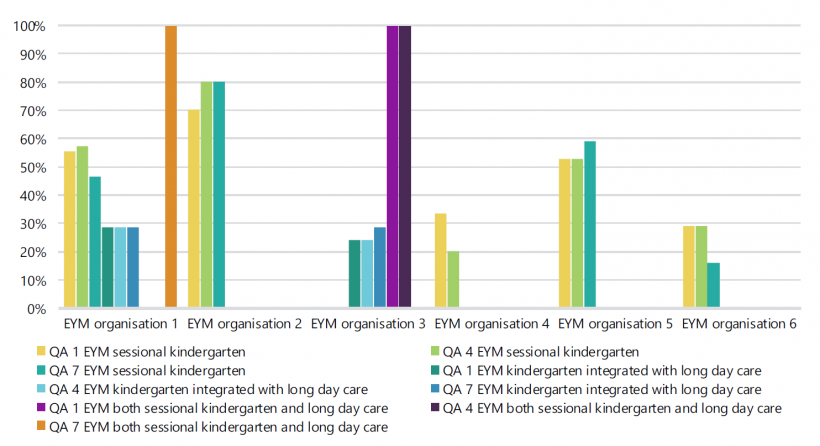

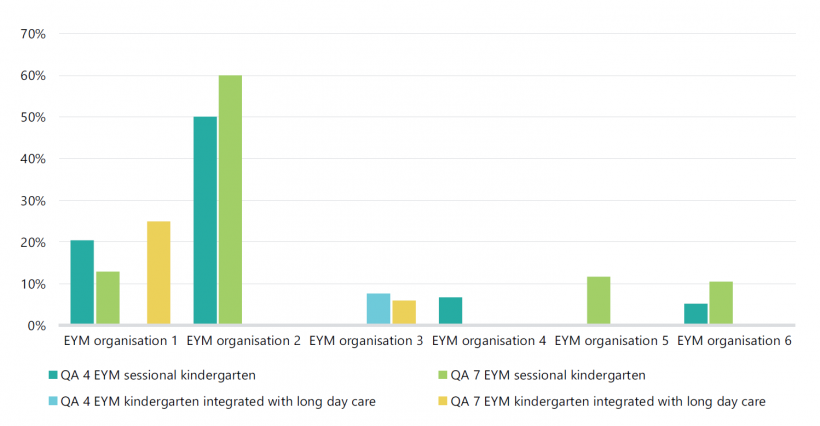

Figure 2G shows our analysis of the proportion of services under each of the six EYM organisations we audited, that achieved the 'exceeding the NQS' rating based on ACECQA data. DET could, for example, use an assessment similar to this to compare the performance of EYM and non-EYM services, or look for changes in performance since a service became EYM-operated. This would potentially give DET some feedback about the impact of the policy framework.

FIGURE 2G: Proportion of audited EYM services with an 'exceeding the NQS' rating

Note: While DET's organisational measure assesses services ‛exceeding the NQS', ‛meeting the NQS' is the legislated minimum. The criteria for services to attain an ‛exceeding the NQS‘ rating was updated in 2018.

Source: VAGO, based on August 2020 ACECQA data.

DET cannot prove that its support leads to improved performance

DET cannot clearly demonstrate that the support it provides to EYM organisations has led to improved performance against the policy framework’s outcomes.

DET provides statewide support to all government-funded kindergarten services. It provides additional support to EYM organisations and services at a regional level. However, it has no formal process to directly track how consistently this support is provided across its different regions.

DET is also not analysing available data and performance information to determine how effective its support is.

DET could use existing statewide performance assessment processes better

DET has existing processes for assessing and publicly reporting on the statewide performance of all government-funded kindergarten services.

DET could use these processes to assess and specifically report on the EYM sector at a statewide level. For example, DET reports on nine performance measures in the State Budget Papers and seven performance measures in the Productivity Commission’s RoGs. These performance measures are relevant to the OPF’s measures on:

- participation

- access to services

- service quality

- educator quality

- parent satisfaction.

3. Implementing the policy framework

Conclusion

DET and EYM organisations have made progress in implementing the policy framework. However, DET’s ability to target finite resources to the areas of greatest need is diminished while it does not have a comprehensive understanding of the gaps, challenges and emerging issues in the EYM program.

DET is unable to effectively address this shortcoming because there are weaknesses and limitations in its policy framework and processes. DET does not systematically capture common issues impacting the EYM program, continuous improvement is not aligned to the OPF, and there is a lack of evaluation and sharing of service delivery improvements across the sector.

DET also does not know if the additional support it provides to EYM organisations is improving the EYM system.

This chapter provides discusses:

3.1 Implementing the policy framework

The transition to the policy framework has required significant effort and investment from the EYM sector. Both DET and EYM organisations report positive progress in the sector since the policy framework was introduced in 2016. Audited EYM organisations all indicated that the current policy framework is a marked improvement on the previous KCM policy framework. EYM organisations also generally report strong working relationships with local DET staff in implementing the policy framework.

To continue improving the EYM program, DET needs to understand the key gaps and challenges that impact EYM organisations and services at both the individual and sector-wide level. This is important to ensure that the support DET provides to the sector is targeted to the gaps and challenges EYM organisations are experiencing.

DET does not have a comprehensive sector-wide view of gaps and challenges

DET does not have a comprehensive view of the issues and challenges that EYM organisations have experienced while implementing the policy framework.

The policy framework states that DET will work with key stakeholders to monitor the EYM sector’s responsiveness and effectiveness by identifying changed conditions and potential gaps. While DET has processes for collecting information about issues at a local level, it does not have a comprehensive or systematic process for collating and analysing issues at a statewide level.

It is important that DET clearly understands potential issues at an organisational, regional and statewide level so it can determine if it needs to provide additional support or policy responses.

DET has limited processes for compiling sector-wide issues

ECPAPAs and early childhood improvement branch managers meet with EYM organisations on a quarterly basis to monitor their performance. DET’s early childhood improvement branches are located across the state and are responsible for overseeing all government-funded services in the ECEC sector.

Branch staff have a significant role in day-to-day communications with EYM organisations and services in their local area. ECPAPAs communicate as needed to identify and address any issues that EYM organisations and services have and in some cases, may need to escalate an issue to DET’s central division to fully resolve it.

ELD relies on the SPG, SPF, work undertaken by contracted third parties and communications between DET’s regions and central divisions to identify sector-wide challenges. DET’s regional and local area staff advised us that the local issues they capture are not systematically reported to ELD, which sets and updates the policy framework.

Early childhood quality participation and access managers are based in each of DET’s four regions. They support DET’s area staff to oversee and manage the service agreements it holds with approved service providers.

ELD holds monthly strategic action group meetings for early childhood quality participation and access managers from DET’s regions and staff from its central divisions. Staff that we surveyed told us that these meetings are the best place to raise issues that EYM organisations in their region or area are experiencing. However, the group’s meeting minutes are not detailed enough to demonstrate that issues are escalated to a sector-wide level if necessary.

DET does not systematically identify and address emerging issues and trends

DET cannot readily identify emerging issues and trends across the EYM sector with the data and performance information it currently collects. DET advised us that this is because it stores data in disparate systems, and the data itself is not easy to analyse.

In many cases, DET captures performance information in static documents instead of IT systems, which makes the data complex and time-consuming to analyse. Where it does capture information in IT systems, extracting specific data fields is difficult.

Since introducing the OPF, DET has not proposed or developed any solutions to overcome these limitations.

Sector experience of implementation challenges

We surveyed and interviewed the six EYM organisations and the respective DET regional and area staff about the key gaps and challenges that they have experienced with the EYM program.

The survey focused on three of the policy framework’s outcomes:

- sustainable and responsive services

- access and participation

- highly skilled, collaborative workforce.

Figure 3A summarises the significant and recurring gaps and challenges that were raised by multiple respondents in the survey. These issues are limited to the experiences of the six audited EYM organisations and the respective DET regional and area staff and may not represent all of the key gaps and challenges experienced across the sector. These gaps and challenges have not been assessed as part of this audit.

FIGURE 3A: Key issues identified by survey participants

| Policy framework outcome | Gaps and challenges |

|---|---|

|

Sustainable and responsive services |

|

|

Access and participation |

|

|

Highly skilled, collaborative workforce |

|

Note: Each issue listed has a range of specific circumstances and contributing factors, which are identified in Appendix G (Figure G1).

Source: VAGO.

DET's support to address gaps and challenges

DET does not have clear supports to assist or address some of the gaps and challenges that the survey participants identified.

Additionally, DET cannot demonstrate that the support it does provide directly assists EYM organisations to address these key issues. It also has not assessed the adequacy and coverage of its support.

DET provides financial and non-financial support to EYM organisations and services in addition to the sector-wide support it provides to all government-funded kindergarten services. As Figure 3B shows, this ranges from funding, scholarships and incentives to programs, waivers and workshops.

FIGURE 3B: DET’s key supports for EYM organisations

| Financial supports | Non-financial supports |

|---|---|

|

DET's support also includes:

|

Source: VAGO.

DET’s investigations may not directly lead to better support for EYM organisations

When DET becomes aware of specific challenges in the ECEC sector or EYM program, or gaps in its data and knowledge, it may conduct targeted investigations. As Figure 3C shows, DET may contract third parties to investigate on its behalf or conduct its own reviews to better understand the issues.

DET’s approach to investigating issues is done on a case-by-case basis and system wide issues remain. DET has not conducted any post-investigation assessments to determine if the actions it took are directly leading to changes that better support the ECEC sector. One investigation is currently underway and three concluded at the end of 2019. However, there has not been sufficient time for DET to assess them.

FIGURE 3C: Examples of DET’s investigations into kindergarten service delivery issues

| Review | Conducted by | Key issues investigated | Results | Actions |

| EYM sector | ||||

| Early Years Managers Activity Analysis, November 2019 | External consultancy, commissioned by ELAA and funded by DET | DET wanted to understand the activities performed by EYM organisations, and how these activities align with the OPF and funding needs. | The report provided findings from a case study perspective and identified several emerging insights for further analysis. | DET provided additional financial support to EYM organisations to better cover requirements under the policy framework, including:

|

| Rural Governance Project, 2017 | ELAA | DET wanted to understand the unique challenges that EYM organisations experience while maintaining sustainable governance arrangements in rural communities. | The project produced three reports:

|

ELAA conducted individual assessments into rural EYM organisations’ governance arrangements and provided one on one support. |

| ECEC sector | ||||

| Victorian Family Day Care Project, July–August 2018 | ABS | DET wanted to understand whether children enrolled in family day care, which is home-based ECEC, are also enrolled in a preschool education program. | The review found evidence that a significant number of children enrolled in family day care are also enrolled in a sessional or long day care kindergarten program. | Unknown. |

| Multicultural Kindergarten Participation Campaign—Communication Strategy, September 2018 | External consultancy | Cultural groups’ lack of awareness about kindergarten services in inner metropolitan areas, which have lower participation rates. | The project identified cultural barriers to accessing kindergarten services. It also developed a communication strategy to address gaps in awareness and help increase the uptake of kindergarten services among three cultural groups. The communication strategy included four key pieces of communications—a poster, flyer, postcard and digital story. |

DET delivered the communication strategy to three cultural groups in inner-metropolitan local government areas of Melbourne:

|

| Kindergarten Participation and Attendance Interim Report, November 2019 | DET | DET wanted to understand the gradual decline in kindergarten participation rates in Victoria and if non participation is being underestimated. | The report identified and provided more understanding about issues relating to participation rates, as well as DET’s current strategies to address them. | DET is currently undertaking the Improving Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Kindergarten Engagement Project to encourage enrolment in kindergarten programs in 2020. |

| Three-Year-Old Kindergarten Capacity Review of Services, December 2019 | External consultancy | DET wanted to understand infrastructure and workforce capacity requirements to rollout the Three-Year-Old Kindergarten reform. | The report found that infrastructure readiness varied across the state and had limited opportunity to expand. | The findings of the report will inform decision-making in regard to the ECEC sector’s kindergarten reform. |

| Improving Culturally and Linguistically diverse Kindergarten Engagement Project Plan, July 2019–April 2020 | External consultancy | DET wanted to understand:

|

The review is currently underway. | Not applicable. |

3.2 Continuous improvement

In the EYM Kindergarten Operating Guidelines, DET clearly states that:

- the quality of EYM services relies on EYM organisations’ continual improvement

- the OPF is a tool that DET can use to continuously identify areas for improvement.

While DET has a continuous improvement process for individual EYM organisations, it has a number of limitations.

Limitations in DET’s continuous improvement process

DET does not align organisational improvements with the OPF’s measures

DET aligns its continuous improvement process with only 10 out of the 30 OPF organisational systems and processes and none of the organisational measures. DET has used its SIP to track continuous improvement by EYM organisations from July 2016.

In each annual reporting cycle, EYM organisations nominate a minimum of three key areas for improvement relevant to the EYM program, or they may nominate activities relevant to other policies such as School Readiness Funding, including:

- each area’s scope (for example, if it affects all or only specific services)

- any barriers to resolving the issue

- the desired outcomes or goals.

ECPAPAs approve EYM organisations’ nominated areas for improvement. EYM organisations self-assess their progress and provide supporting evidence for DET to assess through quarterly reviews.

However, DET does not systematically capture improvements or necessarily align them with the OPF’s organisational measures. Additionally, the SIP has limitations for tracking continuous improvement because it allows EYM organisations to:

- document projects that are already underway rather than prompting them to select the highest priority areas that require attention

- request that their evidence is only sighted, not submitted. This is partly to reduce EYM organisations’ administrative burden, but also to overcome limitations with the SIP’s online portal. This means that DET does not systematically and comprehensively collect evidence to support EYM organisations’ improvement progress.

DET has limited mechanisms to escalate common areas for improvement

DET has no clear mechanism for ECPAPAs to collate and escalate common areas for improvement. This means that DET cannot easily address common issues at a statewide level or share them with the sector for mutual benefit.

As with the gaps and challenges discussed, DET’s regional and area staff advised us that ELD’s monthly strategic action group meetings and other forums are the best places to raise common areas for improvement. However, the minutes from these forums and meetings are not detailed enough to demonstrate that common areas for improvement are escalated to a sector-wide level.

DET has only established a continuous improvement process at an organisational level

DET does not have a continuous improvement process for the EYM program at a regional or statewide level. As DET does not assess the EYM program’s performance against the OPF’s measures at these levels, it does not have a mechanism to identify and therefore act on areas of need.

There is limited knowledge sharing across the sector

EYM organisations and DET’s regional and area staff advised us that there is a general lack of knowledge sharing across the EYM sector. This includes a lack of reporting from DET’s central division on the data and performance information it routinely collects from the sector.

In a review of all relevant forum documents, we found only one instance where a lesson learnt was shared at an EYM reference group forum in March 2019. This related to one EYM organisation’s experience managing a complex complaint. During the forum, the organisation explained how it used business improvement actions to prevent similar complaints from occurring in the future.

DET has no formal processes for capturing lessons learnt. While some EYM organisations occasionally record them in their SIPs, DET does not share this knowledge at a regional or statewide level for other EYM organisations’ benefit.

Service delivery improvements

We identified several instances of service delivery improvements during this audit, as well as cases where EYM organisations have addressed the needs of their local communities with tailored solutions. Figure 3D describes some examples of this.

FIGURE 3D: Service delivery improvement examples

| EYM organisation | Service delivery improvement |

|---|---|

| Goulburn Region Preschool Association | Goulburn Region Preschool Association is improving accessibility to its Barmah kindergarten service by providing necessary free transport for vulnerable children who are eligible for kindergarten and living in the Cummeragunja Reserve. Barmah is the closest service to the reserve and many families do not have access to transport. |

| Glen Eira Kindergarten Association | Glen Eira Kindergarten Association is developing the capacity of its staff over time through on the job training of casual workers (including recent graduates) through its local workforce register. |

| Glen Eira Kindergarten Association is strengthening its communication and engagement with parent advisory groups by providing tools that clearly set out their obligations and expectations as volunteers. For example, terms of reference, a code of conduct policy and a parent advisory group manual. | |

| Greater Shepparton City Council | Greater Shepparton City Council is taking a flexible approach to ensure the long-term viability of its services. It has suspended a four-year-old kindergarten program twice in the last four years while continuing the three-year-old play groups in response to community demand. It placed eligible children in alternative services. Given its rural location, this service is prone to fluctuating enrolment numbers, which it monitors and annually responds to. |

| Early Childhood Management Services | Early Childhood Management Services seconded two family violence workers from the Caroline Chisholm Society for 12 months as outreach family support workers. The Outreach Family Support Program is a Victorian Government-funded pilot designed to connect families experiencing vulnerability to free kindergarten and other specialist support. |

| Goodstart Early Learning Services | Goodstart Early Learning Services’ Early Learning Fund provides support grants to help children living in disadvantaged circumstances access four-year-old kindergarten. |

Source: VAGO

We found further examples that DET could share more widely to benefit the sector and individual EYM organisations. However, DET’s current approach to oversight and performance monitoring limits its ability to capture and share these cases.

Appendix A. Submissions and comments

We have consulted with City of Whittlesea, DET, Early Childhood Management Services, Glen Eira City Council, Glen Eira Kindergarten Association, Goodstart Early Learning Services, Goulburn Region Preschool Association, Greater Shepparton City Council and Try Australia and we considered their views when reaching our audit conclusions. As required by the Audit Act 1994, we gave a draft copy of this report, or relevant extracts, to those agencies and asked for their submissions and comments.

Responsibility for the accuracy, fairness and balance of those comments rests solely with the agency head.

Responses were received as follows:

Response provided by the Director Community Services, City of Whittlesea

Response provided by the Associate Secretary, DET

Response provided by the Chief Executive Officer, Glen Eira City Council

Response provided by the Chief Executive Officer, Goodstart Early Learning Services

Appendix B. Acronyms, abbreviations and glossary

| Acronyms | |

|---|---|

| ABS | Australian Bureau of Statistics |

| ACECQA | Australian Children’s Education and Care Quality Authority |

| CoMs | Committees of Management |

| DET | Department of Education and Training |

| ECEC | early childhood education and care |

| ECPAPA | early childhood performance and planning advisor |

| ELAA | Early Learning Association Australia |

| ELD | Early Learning Division |

| ESK | early start kindergarten |

| EYM | Early Years Management |

| FOPMF | Funded Organisation Performance Monitoring Framework |

| KFS | Kindergarten Fee Subsidy |

| KIMS | Kindergarten Information Management System |

| MIF | Monitoring and Improvement Framework |

| NFP | not-for-profit |

| NQS | National Quality Standard |

| OPF | Outcomes and Performance Framework |

| QA | quality area |

| QARD | Quality Assessment and Regulation Division |

| RoGs | Report on Government Services |

| SAMS2 | Service Agreement Management System 2 |

| SIP | service improvement plan |

| SPF | Strategic Partnership Forum |

| SPG | Strategic Partnership Group |

| VAGO | Victorian Auditor-General’s Office |

|

Abbreviations |

|

|---|---|

| KCM policy framework | Kindergarten Cluster Management Policy Framework |

| the policy framework | Early Years Management Policy Framework |

Appendix C. Scope of this audit

| Who we audited | What we assessed | What the audit cost |

|---|---|---|

|

We assessed how DET has:

|

The cost of this audit was $770 000. |

Our methods