Enhancing Food and Fibre Productivity

Overview

Measuring the impacts of the Department of Economic Development Jobs Transport & Resources’ (the department) research, development and extension (RD&E) investments is an inherently complex task. However, there is evidence that the state’s investment in RD&E contributes to productivity growth in Victoria’s priority agriculture industries.

Many aspects of the department’s approach to agricultural RD&E reflect good practice. It has a robust investment framework and a strong commitment to RD&E collaboration nationally. It has also carried out many evaluations of its RD&E activities.

However, the application of the department’s RD&E frameworks has some gaps. These have limited its ability to show the basis for investment decisions and to demonstrate their impact, and to show how it has acted on the results of past RD&E programs.

The capacity for RD&E to drive future productivity growth and to achieve long-term goals is challenged by a range of factors, including a lack of industry investment in key areas and constrained government resourcing. Future performance also depends on RD&E activities leading to change in practices and farmers adopting new technologies. Although many evaluations show where the department’s R&D results have been effectively disseminated to end users and other stakeholders, it has not followed through on plans to assess the overall effectiveness of its approaches to delivering services and changing practices.

Enhancing Food and Fibre Productivity: Message

Ordered to be published

VICTORIAN GOVERNMENT PRINTER August 2016

PP No 182, Session 2014–16

President

Legislative Council

Parliament House

Melbourne

Speaker

Legislative Assembly

Parliament House

Melbourne

Dear Presiding Officers

Under the provisions of section 16AB of the Audit Act 1994, I transmit my report on the audit Enhancing Food and Fibre Productivity.

Yours faithfully

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

17 August 2016

Auditor-General's comments

|

Dr Peter Frost Acting Auditor-General |

Audit team Andrew Evans—Engagement Leader Chris Badelow—Team Leader Catherine Sandercock—Analyst Engagement Quality Control Reviewer Michael Herbert |

Victoria owes much to its food and fibre sector. In addition to employing over 190 000 people, the sector's exports during 2014–15 were valued at $11.6 billion—27 per cent of Australia's total food and fibre exports. Recognising this past performance and future growth opportunities, the Victorian Government has identified food and fibre as one of its six priority sectors.

While there are strong growth opportunities in global markets, sustaining the sector's success into the future will be challenging. In recent decades, the rate of agricultural productivity growth in Australia has slowed, mainly in response to drought but also because of declining public investment in agricultural research, development and extension (RD&E) since the 1970s.

The sector's future performance relies heavily on RD&E. It can lead to the development and adoption of technologies, systems and practices that increase the value and volume of agricultural production and that lower input costs. RD&E can also help to sustain the natural resource base upon which the food and fibre sector relies by reducing potential risks and impacts such as land degradation, pests and diseases, water shortages and climate change.

I note that agricultural RD&E in Victoria forms part of the National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework, which promotes coordination and collaboration between Commonwealth and state governments, rural research and development corporations, CSIRO, industry and universities. It is critical that state-funded agricultural RD&E aligns with the state's nominated roles within this framework and utilises the wide range of skills and expertise available.

In this audit, I assessed the extent to which agricultural RD&E is used to drive innovation, productivity and practice change. The audit focused on the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) as the agency responsible for delivering state-funded agricultural RD&E in Victoria.

While it is difficult to measure the impact of the department's RD&E investments, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that they have contributed to productivity growth and practice change in Victoria's priority agricultural industries. I also found that the department has well-designed models for setting RD&E priorities and making investment decisions, for providing a route to market for its research and development (R&D) outputs, and for monitoring, evaluating and reporting on its RD&E activities.

Unfortunately, the department has not consistently applied these models, limiting the evidence base underpinning its investment decisions and its capacity to show the full impact of its RD&E activities.

My recommendations reinforce the need to address this gap and clarify where the department can further improve its existing approaches to agricultural RD&E. They also highlight the need for the department to have a clearer overarching strategic direction for RD&E investment. I am pleased that the department has accepted each of these recommendations and developed plans to implement them.

I would like to thank the department for its assistance and cooperation throughout the audit.

Dr Peter Frost

Acting Auditor-General

August 2016

Audit Summary

Victoria's agricultural sector comprises around 30 000 businesses and employs more than 190 000 Victorians, mostly in regional Victoria. The sector contributes significantly to the state's economy. In 2014–15, Victorian food and fibre exports were valued at $11.6 billion—27 per cent of Australia's total food and fibre exports.

While Australia's agricultural productivity continues to increase, the rate of growth has slowed over the past two decades. This is mainly because of severe drought and less public investment in agricultural research, development and extension (RD&E) since the 1970s.

Agricultural RD&E underpins the productivity and competitiveness of agricultural industries. It can lead to better farming systems and practices that increase the value and volume of production and reduce input costs.

Victoria's agricultural RD&E is part of a national agricultural innovation system based on collaboration between governments, researchers, farm businesses and suppliers. Supporting this system is the National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework (the national framework), which aims to increase collaboration between stakeholders, focus research capability on addressing industry and cross-industry issues, and focus resources so that they are used effectively and efficiently.

Under the national framework, Victoria has a 'major priority' RD&E role in four agricultural industries—dairy, grains (pulses), horticulture and sheep meat. It also has major priority roles in six cross-industry areas—animal welfare, climate change, food and nutrition, plant biosecurity, water use in agriculture, and soils.

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) is responsible for delivering state-funded agricultural RD&E in Victoria. The department aims to sustainably increase productivity and competitiveness through RD&E.

This audit assessed the extent to which agricultural RD&E is used to drive innovation, productivity and practice change.

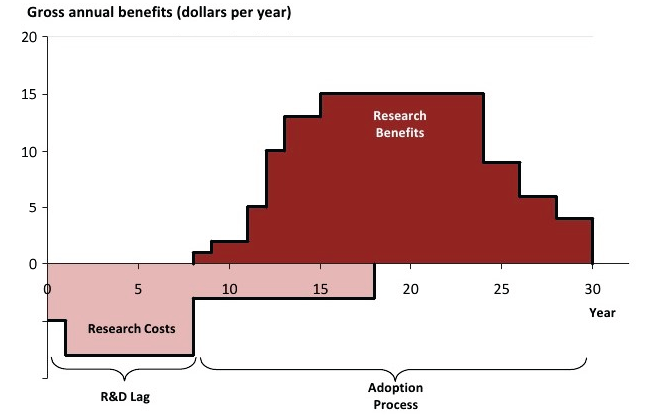

Conclusions

Measuring and attributing the impacts of the department's RD&E investments is an inherently complex task because of the various external factors that influence agricultural production, the highly collaborative nature of agricultural RD&E in Australia, and the long time needed for RD&E activities to produce the desired benefits. However, there is evidence that the state's investment in RD&E contributes to productivity growth in Victoria's priority agriculture industries.

Many aspects of the department's approach to agricultural RD&E reflect good practice. The department has a robust investment framework that enables evidence-based priority-setting and investment decision-making. It also has a strong commitment to RD&E collaboration nationally. It has carried out many program- and industry-level evaluations of its RD&E activities.

However, the application of the department's investment and monitoring, evaluation and reporting frameworks has some gaps. These have limited its ability to show the basis for its investment decisions, to demonstrate their impact and to show how it has acted on the results of past RD&E programs. Also, the absence of a clearly documented overarching strategic direction for RD&E has resulted in a fragmented planning approach that does not clearly identify or communicate to staff and stakeholders how the department plans to attract and grow investment, maintain adequate RD&E capability or foster innovation.

The capacity for RD&E to drive future productivity growth and to achieve long-term goals continues to be challenged by a range of factors, including a lack of industry investment in key areas and constrained government resourcing. Future performance also depends on RD&E activities leading to change in practices and farmers adopting new technologies. Although many evaluations show where the department's R&D results have been effectively disseminated to end users and other stakeholders, the department has not followed through on plans to assess the overall effectiveness of its approaches to delivering services and changing practices.

Findings

Research priorities and funding allocations

Investment framework well designed but inconsistently followed

Every year, the department uses its agriculture investment framework to set RD&E priorities—which are detailed in investment plans for each of its four priority industries—and to select RD&E projects for investment based on agreed priorities. This investment framework and its selection criteria are well designed and enable a logical, evidence‑based approach to prioritising and choosing projects.

At an industry level, the department's RD&E priorities and projects are in line with state and national frameworks. However, inconsistent application of the key steps in the department's investment framework and a lack of evidence showing how specific decisions have been made have limited the reliability and transparency of the department's detailed decisions about RD&E priorities and projects.

The department has recognised the need to improve its approach to setting RD&E priorities for cross-industry issues and has expanded the scope of its industry leadership groups—which comprise departmental staff and provide advice to senior management on priorities, investments and stakeholders—to support this.

Need for an overarching strategic direction for investment in RD&E

Although the department's investment framework is well designed, its strategic direction for agricultural RD&E is not clearly documented. The department has many elements of a strategic direction detailed in a range of documents so it is in a good position to more clearly and cohesively communicate these to staff, to clarify its aims and directions for RD&E and to more closely guide investment decisions.

Industry co-investment in RD&E lacking in key areas

Bilateral agreements have been central to the department's capacity to get industry co-investment for RD&E in the dairy and grains industries. The absence of such agreements in the sheep and beef, horticulture, and soil and water sectors means that industry co-investment is unbalanced and not in line with the department's criteria for choosing projects.

Planning significant changes to national RD&E roles

In early 2016, the department reviewed its nominated priority roles under the national framework and it now plans significant changes. These proposed changes still need to be negotiated with other partners in the national framework.

If implemented, the proposed changes will mean more targeted research in priority industries and less productivity-focused research in industries where there is inadequate co-investment, with realignment into research areas that have greater public benefit such as biosecurity, traceability, animal welfare and value-chain efficiency. The department's rationale for these planned changes reflects:

- the evolving national model for RD&E, where more non-government bodies are carrying out research and government bodies are placing more emphasis on more focused, strategic research

- the need to realign the department's national RD&E roles with its existing capability and capacity.

Delivering research and development outputs to end users

The 'route to market', or 'path to impact', refers to the way the results of research and development (R&D) are further developed and delivered to the target audience—the next users or end users of the results. These results commonly include information, products and services. In agriculture, users are most commonly farmers, service providers such as agricultural consultants, industry bodies, other researchers, policy analysts and other government agencies.

The department has made the route to market a critical component of its investment decisions and project delivery. Although it has had many successes in delivering its R&D results to farmers, there are several aspects it can improve.

Good model for engaging service providers but not fully delivered

The department's 2009 Better Services to Farmers strategy improved its model for delivering R&D results to end users and involved a greater focus on working in partnership with private sector providers to deliver extension services. Evaluations of some larger programs show that the department has had success in delivering this partnership approach, particularly in the beef and sheep industries. Similar success with this model has been shown by the department's performance against performance indicators that it recently established.

However, as a result of incomplete implementation and monitoring of the model, the department is not yet engaging farmers and service providers as early, consistently and effectively as it needs to. It has also not monitored how well it has managed the risks associated with the model.

Selection of audiences and delivery methods needs to improve

The department can do more to make sure its R&D results and information are effectively tailored, accessible and targeted at the right audience. For many projects, it identifies only generic audiences and routes to market rather than selecting more specific approaches based on detailed considerations and analysis.

This undermines its investments in R&D and constrains innovation—it limits the department's ability to maximise the number of farmers it reaches with its information, products and services and the rate at which farmers adopt new practices.

Successful delivery can be further enhanced

The department has had many successes in delivering its R&D results to farmers, through both public and commercial routes to market. It has used a range of good practices to do this. However, across its more than 300 projects, it does not have sufficient oversight of whether it is systematically engaging the right audiences in the right way. Nor does it have sufficient assurance that it is using routes to market to increase the reach and accelerate the adoption of its information, products and services as much as possible.

Monitoring, evaluating and reporting on agricultural RD&E

Sound monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework followed inconsistently

The department's latest monitoring, evaluation and reporting (MER) framework for agricultural RD&E remains in draft format. Its documented practices are sound, but its performance measures, key performance indicators and targets do not focus enough on the impact of changes in agricultural practices and productivity on the long-term sustainability of natural resources.

The department regularly monitors the delivery of its RD&E projects and has carried out or contributed to more than 100 RD&E evaluations in the past five years. Over the past decade, it has also met most of its Budget Paper 3 measures that relate to agricultural RD&E.

There are gaps in the department's application of its documented MER practices which limit its understanding of the impacts of its RD&E activities and how its evaluations have been used. Weaknesses in its information systems further undermine its MER capacity.

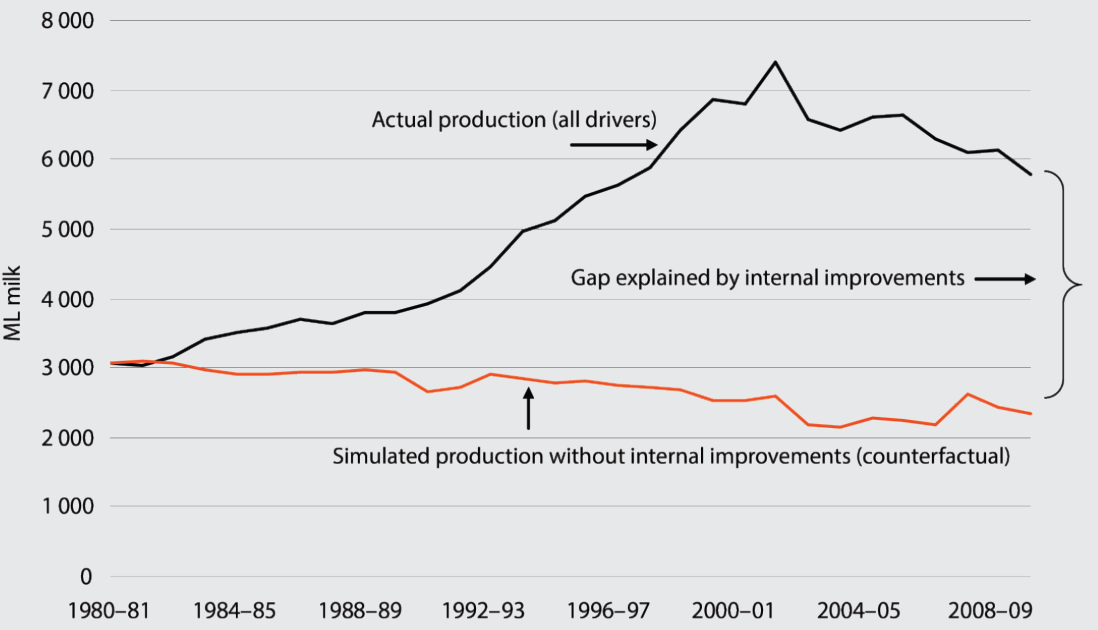

'Mega' evaluations show significant RD&E impacts but have variable rigour and relevance

The department has a key role in measuring the impacts of its RD&E activities, which are difficult to assess. Its industry-level evaluations of RD&E are valuable and point to evidence of long-term improvements in the productivity and profitability of Victoria's agricultural industries which have been partly driven by RD&E investment. However, the rigour and relevance of these evaluations to RD&E varies. The department has room to improve how it prioritises, prepares for and coordinates these evaluations.

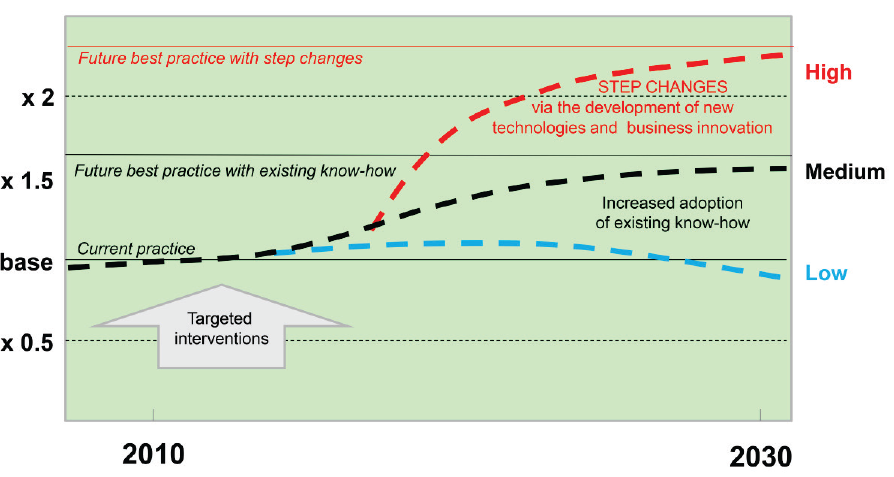

RD&E important in push to double food and fibre production by 2030

The department's RD&E activities will be a major contributing factor to Victoria's capacity to achieve the 2012 Growing Food and Fibre initiative's stated target of doubling food and fibre production by 2030. However, achieving this goal also depends on favourable economic and environmental conditions.

It remains unclear how achievable the target is, four years after it was set.

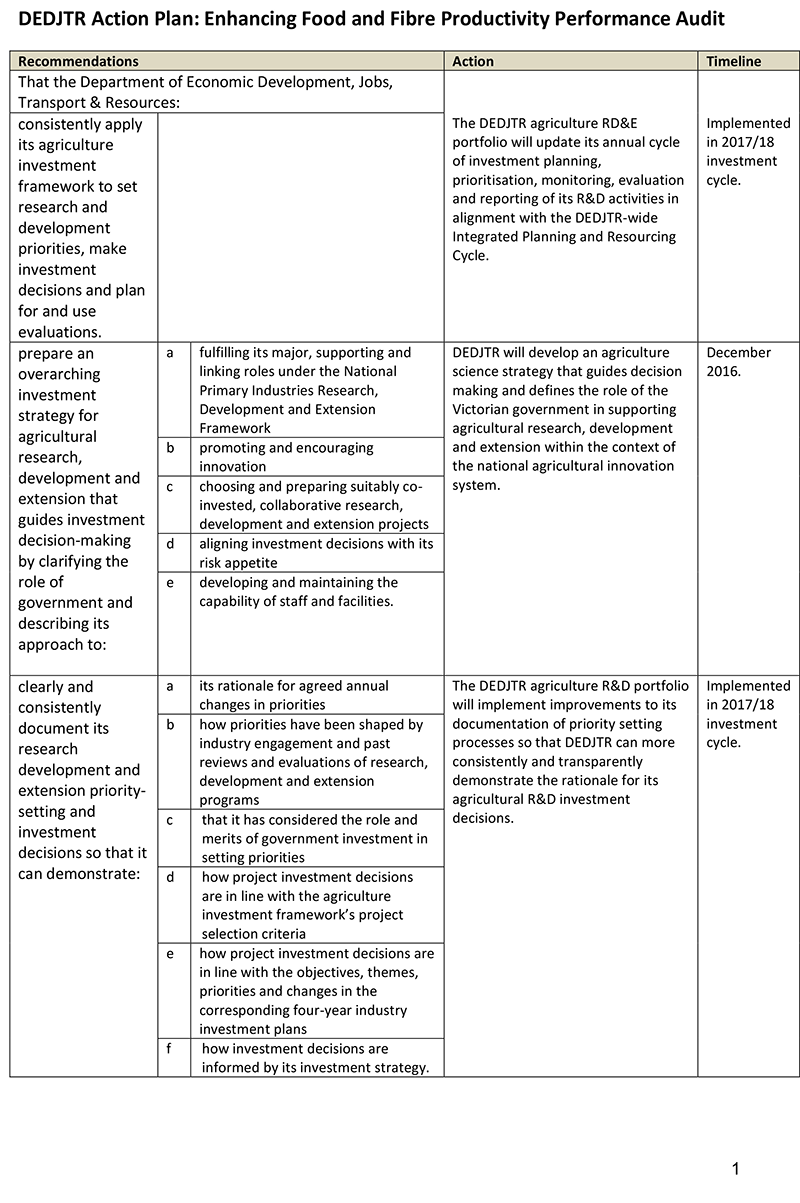

Recommendations

That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- consistently apply its agriculture investment framework to set research, development and extension priorities, make investment decisions, and plan for and use evaluations.

- prepare an overarching investment strategy for agricultural research, development and extension that guides investment decision‑making by clarifying the role of government and describing its approach to:

- fulfilling its major, supporting and linking roles under the National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework

- promoting and encouraging innovation

- choosing and preparing suitably co-invested, collaborative research, development and extension projects

- aligning investment decisions with its risk appetite

- developing and maintaining the capability of staff and facilities.

- clearly and consistently document its research, development and extension priority-setting and investment decisions so that it can demonstrate:

- its rationale for agreed annual changes in priorities

- how priorities have been shaped by industry engagement and past reviews and evaluations of research, development and extension programs

- that it has considered the role and merits of government investment in setting priorities

- how project investment decisions are in line with the agriculture investment framework's project selection criteria

- how project investment decisions are in line with the objectives, themes, priorities and changes in the corresponding four-year industry investment plans

- how investment decisions are informed by its investment strategy.

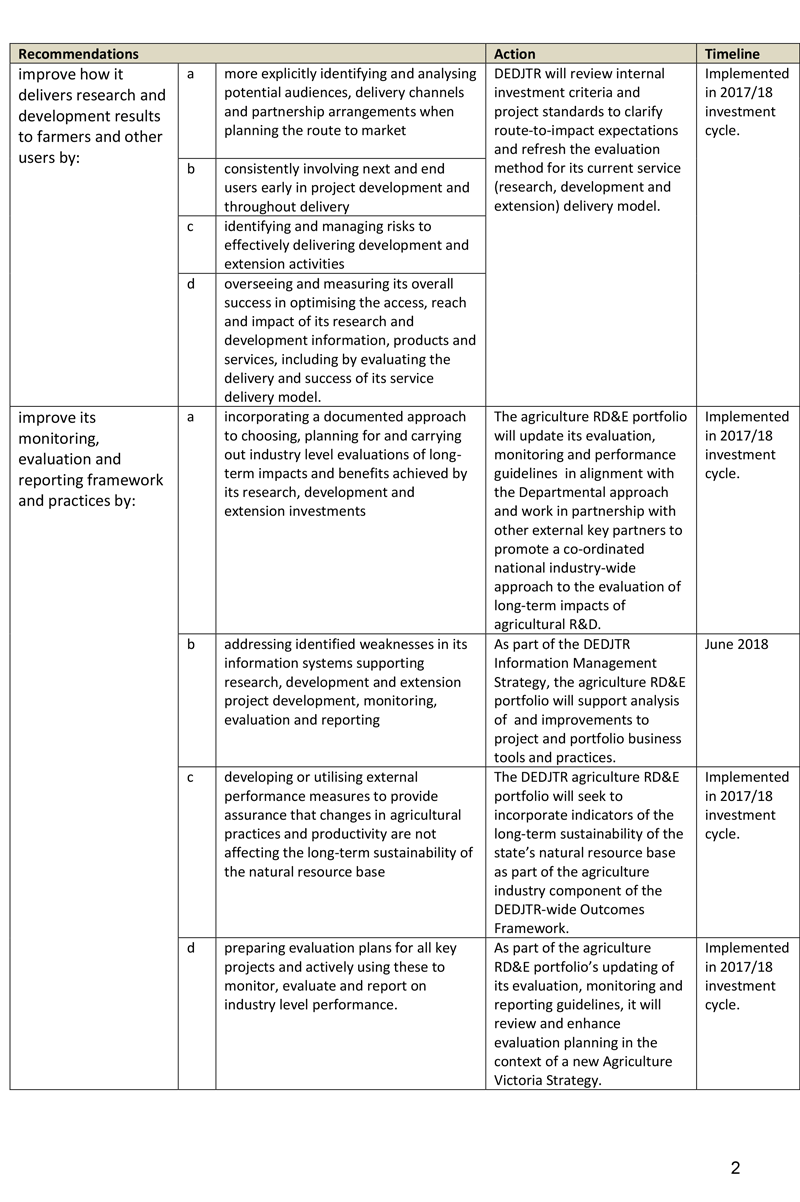

- improve how it delivers research and development results to farmers and other users by:

- more explicitly identifying and analysing potential audiences, delivery channels and partnership arrangements when planning the route to market

- consistently involving next users and end users early in project development and throughout delivery

- identifying and managing risks to effectively delivering development and extension activities

- overseeing and measuring its overall success in optimising the access, reach and impact of its research and development information, products and services, including by evaluating the delivery and success of its service delivery model.

- improve its monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework and practices by:

- preparing evaluation plans for all key projects and actively using these to monitor, evaluate and report on industry-level performance.

- developing or utilising external performance measures to provide assurance that changes in agricultural practices and productivity are not affecting the long-term sustainability of the natural resource base

- addressing identified weaknesses in its information systems supporting research, development and extension project development, monitoring, evaluation and reporting

- incorporating a documented approach to choosing, planning for and carrying out industry-level evaluations of the long-term impacts and benefits achieved by its research, development and extension investments

Submissions and comments received

We have professionally engaged with the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources throughout the course of the audit. In accordance with section 16(3) of the Audit Act 1994 we provided a copy of this report to the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources and the Department of Premier & Cabinet and requested their submissions or comments.

We have considered those views in reaching our audit conclusions and have represented them to the extent relevant and warranted. Their full section 16(3) submissions and comments are included in Appendix A.

1 Background

1.1 Introduction

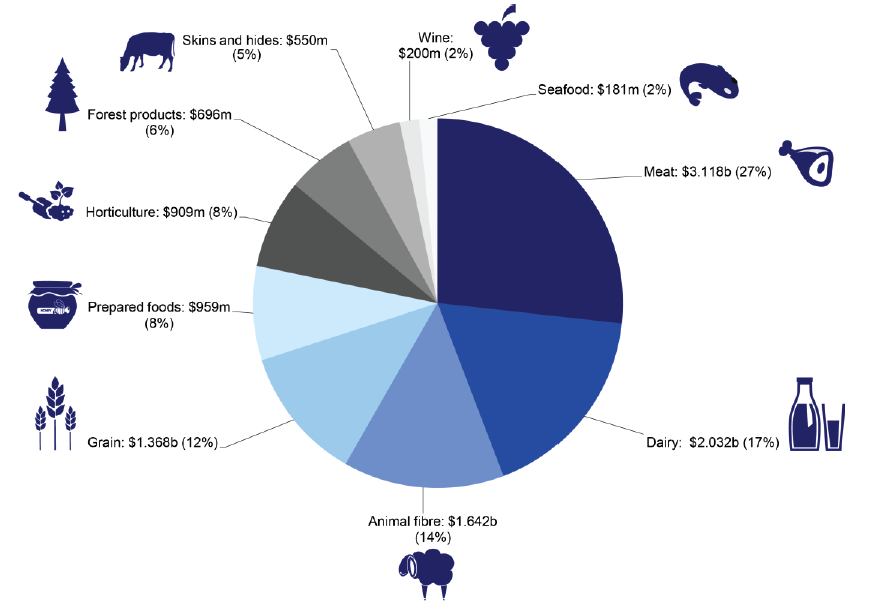

Victoria's agricultural sector comprises around 30 000 businesses and employs more than 190 000 Victorians, mostly in regional Victoria. The sector makes a large contribution to the state's economy. In 2014–15, Victorian food and fibre exports were worth about $11.6 billion—about 27 per cent of Australia's total food and fibre exports. Victoria's main export industries during 2014–15 were meat (earning $3.1 billion) and dairy (earning $2 billion), which collectively accounted for 44 per cent of the total value of the state's food and fibre exports.

Figure 1A

Victorian food and fibre exports by commodity group, 2014–15

Note: Fibre products comprise animal fibre such as wool, skins and hides, and forest products.

Note: Figures may not total 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Australia's agricultural productivity continues to grow, but the rate of growth has slowed over the past two decades. The Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences (ABARES) says that agricultural total factor productivity—a widely used index for measuring productivity in Australia—grew at an average annual rate of 2 per cent between 1948–49 and 2013–14. However, since the late 1990s, growth in agricultural total factor productivity has slowed to an average annual rate of 0.9 per cent.

ABARES attributes the slowing of productivity growth in Australian agriculture mainly to severe drought, but also to reduced public investment in agricultural research, development and extension (RD&E) since the 1970s.

Recent national and state initiatives and reviews have identified food and fibre as one of only a few sectors with the potential to boost economic development and innovation.

The federal government's National Innovation and Science Agenda identified food and fibre as a focus area and introduced a new innovation hub to encourage new technology and the use of big data in agriculture. The Committee for Economic Development of Australia's 2015 report Big Issues ranked agriculture as the second‑most important sector in providing future growth for the economy.

Food and fibre is one of the Victorian Government's six priority growth sectors. The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) has estimated that farmers producing food and fibre manage around 60 per cent of the state's available land and use up to 70 per cent of available water.

Reviews of the food and fibre sector have identified a range of environmental constraints that limit farmers' capacity to increase productivity while sustaining the natural resource base on which the sector relies. These include:

- land degradation, such as soil erosion, salinity and waterlogging

- pests and diseases, and their resistance to management efforts

- water shortages, such as reduced allocations and poor water quality

- climate change, such as extreme weather events and wildfires.

1.2 Agricultural RD&E

RD&E underpins the productivity and competitiveness of agricultural industries. Agricultural RD&E can lead to improved farming systems and practices that increase the value and volume of production and reduce input costs.

Research typically includes:

- basic research—experimental or theoretical work to acquire new knowledge of the underlying foundation of phenomena and observable facts, without looking at any particular application of that knowledge

- applied research—investigating to acquire new knowledge, but focusing on a specific practical aim or objective.

Development is systematic work that focuses on producing or improving products or services, by drawing on existing knowledge gained from multiple sources including research and/or practical experience. It includes applying, adapting and validating known technologies and information to suit specific environments and practices.

Extension draws on research and development (R&D) and involves the public and private sectors working to transfer knowledge about ways to improve productivity and sustainability to and between farmers. Knowledge transfer may be direct or indirect through service providers.

Agricultural RD&E and productivity are directly linked. The 2011 ABARES report Public investment in R&D and extension and productivity in Australian broadacre agriculture, found that:

- public R&D investment had 'significantly promoted productivity growth in Australia's broadacre sector'—covering grain, beef and sheep production—between 1953 and 2007

- the relative contributions of domestic and foreign R&D had been 'roughly equal, accounting for 0.6 per cent and 0.63 per cent of annual total factor productivity growth in the broadacre sector, respectively'

- internal rates of return for research and extension were 15.4 to 38.2 per cent and 32.6 to 57.1 per cent a year, respectively.

The 2011 ABARES report also highlighted a decline in agricultural RD&E investment in Australia since the 1970s. Research intensity—the ratio of public spending on RD&E to agricultural gross domestic product—peaked at 5 per cent in 1978, before declining to 3 per cent in 2007. The annual rate of growth in public spending on agricultural R&D declined from about 7 per cent a year between 1953 and 1978 to about 0.6 per cent a year from 1978 to 2007.

State investment in agricultural RD&E has also been in long-term decline. Data from the department shows that:

- state government investment in agricultural research has declined by about 45 per cent since 1998, when adjusted for inflation

- state government investment in agricultural development and extension services has declined by 53 per cent since 2009, when adjusted for inflation.

- Victorian agricultural RD&E intensity declined from about 1.35 per cent in 1998 to nearly 0.6 per cent in 2015.

1.3 National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework

Victoria's agricultural RD&E is part of a national agricultural innovation system that is based on collaboration. Governments, researchers, farm businesses and suppliers work together to generate ideas and knowledge, to turn these into new products, services and processes, and then to support the agricultural sector to adopt them, with the aim of increasing productivity, profitability and sustainability.

A key element of this is the National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework (the national framework), which the Commonwealth Government began in 2009 to:

- increase collaboration and coordination between key stakeholders involved in RD&E—the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), Rural Research and Development Corporations, state government departments, industry and universities

- focus research capability to better address problems in and across industries

- focus RD&E resources so that they are used more effectively and efficiently.

The framework is based on the premise that basic research can be carried out nationally and the outputs can be adapted to meet regional and local needs. Under this model, each state can focus on its RD&E strengths and access additional information from the states that have strengths in other aspects.

Under the national framework, 14 national RD&E strategies have been prepared for specific agricultural industries and seven to address cross-industry issues. States decide what their research role is in specific industries by assigning a:

- 'major priority' role—the state will carry out a lead national role in R&D

- 'support' role—the state carries out some R&D, but others will provide the major effort

- 'link' role—the state will carry out little to no research in the industry, but will access information and resources from other states and agencies.

Figure 1B lists Victoria's 'major priority' roles under the national framework relevant to agriculture.

Figure 1B

Victoria's 'major priority' roles relevant to agriculture under the National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework

|

Industry |

Cross-industry issues |

|---|---|

|

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.4 The department's role in RD&E

The department's Agriculture and Resources Group is responsible for delivering state‑funded agricultural RD&E in Victoria. It aims to sustainably increase productivity and competitiveness through RD&E. Its priorities for RD&E are the dairy, sheep, beef, grains and selected horticulture industries. These are the focus of the previous government's Growing Food and Fibre and Food to Asia Action Plan initiatives.

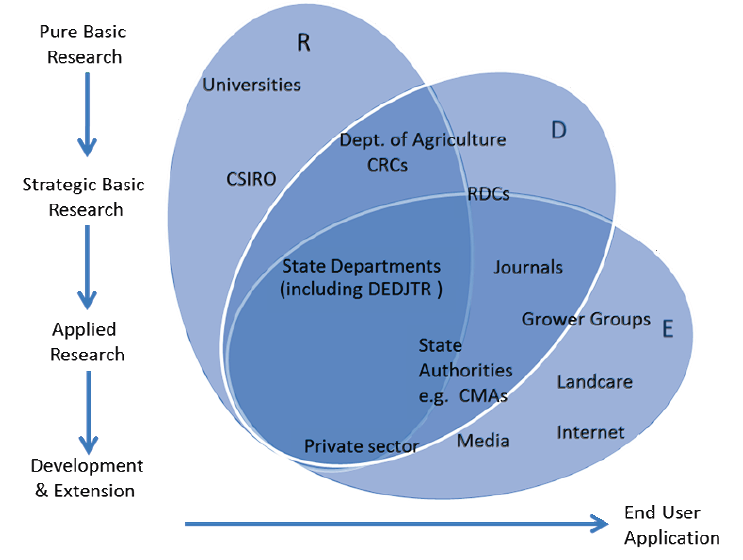

Figure 1C shows the department's role within the broad continuum for agricultural RD&E.

Figure 1C

The department's RD&E continuum

Note: CRCs are cooperative research centres; RDCs are rural research and development corporations; CMAs are catchment management authorities.

Source: Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

As shown in Figure 1D, the department received over $108 million in 2015–16 for agricultural RD&E, which includes external industry and other government sources. It receives matching funding for RD&E mainly through industry co-investors—primarily research and development corporations and the Commonwealth Government.

Figure 1D

Funding for agricultural RD&E in Victoria, 2015–16

|

Industry |

State investment ($ million) |

External investment ($ million) |

Combined investment ($ million) |

Per cent of total investment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Dairy |

17.43 |

15.15 |

32.58 |

30 |

|

Grains |

14.16 |

21.93 |

36.09 |

33 |

|

Horticulture |

9.57 |

3.91 |

13.48 |

12 |

|

Sheep and beef |

12.46 |

2.70 |

15.16 |

14 |

|

Cross-industry(a) |

5.58 |

5.40 |

10.98 |

10 |

|

Total |

59.20 |

49.09 |

108.29 |

100 |

(a) Covers areas not attributable to a specific industry.

Note: Figures may not total 100 per cent due to rounding.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office, using data provided by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

To deliver its RD&E priorities, the department's Agriculture and Resources Group works with a range of public and private sector stakeholders, through various arrangements including:

- collaborations, such as AgriBio, a $288 million joint venture with La Trobe University that provides an agricultural biosciences R&D facility

- engaging external providers, including universities, R&D bodies and private providers that are contracted to provide research

- partnerships with organisations such as CSIRO, rural research and development corporations and cooperative research centres.

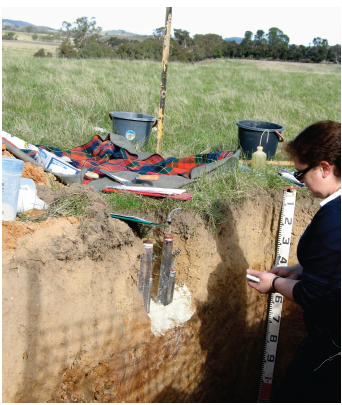

Measuring water movement in soils to improve pasture management practices. Photo supplied by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

Figure 1E details the various RD&E roles of each branch within the department's Agriculture and Resources Group.

Figure 1E

Branches in the Agriculture and Resources Group involved in RD&E

|

Branch |

Roles |

|---|---|

|

Agriculture Research and Farm Services |

|

|

Biosciences Research |

|

|

Agriculture Services and Biosecurity Operations |

|

|

Strategic Partnerships |

|

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

1.5 Victorian agricultural RD&E policies

The 2012 Growing Food and Fibre initiative aimed to double food and fibre production by 2030. The initiative included an investment of $61 million for targeted R&D over four years and ongoing annual funding of $15.7 million in subsequent years to boost productivity and profitability in Victoria's dairy, grains, red meat and horticultural industries.

The 2014 Food to Asia Action Plan aimed to work with industry in seven areas to grow exports of premium, safe and reliable food and beverage products to Asia and included investment of about $35 million. One of these seven areas included better-targeted RD&E. Actions under this theme covered:

- increasing support for RD&E services to improve natural resource management (including soils, water and climate adaptation)

- building understanding of Asian consumer preferences

- supporting small- to medium-sized enterprises to collaborate and innovate through strategic partnerships with innovation hubs

- exploring the next generation of milk components that will help to convert milk from a commodity to higher-value products for Asian markets.

The current government is investing $200 million to establish a Future Industries Fund that will support businesses in six high-growth sectors, including food and fibre. This has included the release of the Food and Fibre Sector Strategy in March 2016, which sets priorities for the sector such as helping businesses to innovate and adopt technology.

1.6 Audit objective and scope

The audit objective was to assess the extent to which agricultural RD&E is used to drive innovation, productivity and practice change.

To address this objective, the audit assessed whether the department's:

- research priorities and funding allocations are based on evidence and aligned with relevant national and state frameworks

- R&D outputs have been effectively disseminated to end users and other relevant stakeholders to drive improvements in innovation, productivity and practice

- RD&E activities are effectively monitored, evaluated and reported on to demonstrate the achievement of intended outcomes and drive continual improvement.

Machinery-of-government changes in recent years have resulted in changes to agency responsibilities for agricultural RD&E in Victoria. Specifically, agricultural RD&E had previously been managed by:

- the former Department of Environment and Primary Industries between April2013 and January 2015

- the former Department of Primary Industries until April 2013.

For convenience, this report attributes the RD&E activities of these former departments to the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

1.7 Audit method and cost

The audit examined agricultural RD&E activities through document reviews and interviews with the department.

The audit was carried out under sector 15 of the Audit Act 1994, in keeping with the Australian Auditing and Assurance Standards. Pursuant to section 20(3) of the Audit Act 1994, unless otherwise indicated, any persons named in this report are not the subject of adverse comment or opinion.

Total cost of the audit was $420 000.

1.8 Structure of the report

The report is structured as follows:

- Part 2 looks at the prioritisation of and investment in RD&E

- Part 3 looks at how R&D outputs are disseminated

- Part 4 looks at the department's RD&E monitoring, evaluation and reporting framework and the benefits and impacts of agricultural RD&E.

2 RD&E priorities and funding allocations

At a glance

Background

The agricultural research, development and extension (RD&E) priorities and investments of the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) should be based on evidence and aligned with state and national frameworks.

Conclusion

The department's RD&E investment framework is sound and its industry-level priorities and investments are in line with state and national frameworks. However, the department's inconsistent application of the framework limits assurance that detailed changes in priorities and investment decisions have been well informed. The absence of a clear overarching strategic direction document for RD&E investment further limits the framework's potential effectiveness.

Findings

- The department's investment framework enables evidence-based RD&E Priority‑setting and project selection in line with state and national frameworks.

- Key steps of the department's investment framework have not been followed consistently.

- Detailed priority-setting and decision-making about investments are not always transparent.

- The focus on cross-industry RD&E has been inadequate but is improving.

- There is no overarching strategic direction documented for RD&E investment.

- The department is proposing significant changes to its national RD&E roles in response to a lack of industry co-investment and a range of other factors.

Recommendations

That the department consistently apply its agriculture investment framework, record its investment decisions and prepare an overarching investment strategy.

2.1 Introduction

The National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework (the national framework) is highly collaborative, with many participants. For the national framework to be effective, each state and territory must prioritise and invest in research, development and extension (RD&E) activities that are in line with its nominated roles.

Therefore, it is important that the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources' (the department) agricultural RD&E priorities and investments are consistent with the national framework. It is also important that priorities and investments are:

- consistent with state policies, strategies and plans

- supportedby evidence-based decision-making to provide assurance that resources are being targeted to the areas of greatest need.

Selecting better crop varieties using robotic imaging technologies. Photo supplied by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

2.2 Conclusion

The department's investment framework for agricultural RD&E allows for an evidence‑based approach to setting priorities and making decisions about investments. The department's industry-level priorities and investment decisions are in line with national and state frameworks. It is taking steps to improve its (previously lacking) focus on prioritising RD&E in cross-industry areas.

Although the investment framework is well designed, the department has not applied it consistently and this has resulted in a lack of assurance that detailed changes in priorities and investment decisions have been well informed. The absence of a clear overarching strategic direction document for RD&E investment in Victoria further limits the investment framework's potential effectiveness. The department is in a strong position to address this latter issue, as it already has aspects of a strategic approach outlined across various documents.

In response to a lack of industry co-investment for RD&E in priority sectors—and a range of other issues—the department is planning significant changes to its nominated roles under the national framework. If put into practice, this will lead to a more targeted approach to agricultural RD&E in Victoria.

2.3 The investment framework for agricultural RD&E

Every year, the department's Agriculture and Resources Group uses its agriculture investment framework to:

- set RD&E Priorities and detail these in the investment plans for each of its four priority industries—dairy, grains, horticulture and sheep and beef

- select RD&E Projects for investment based on agreed priorities.

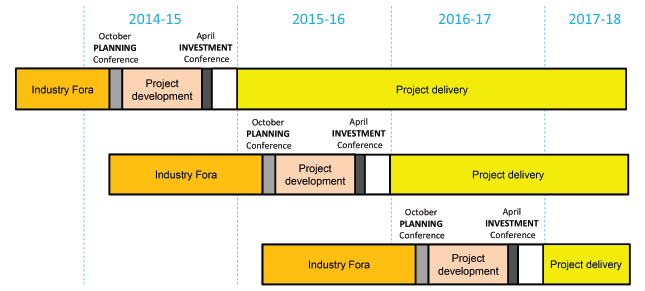

Figure 2A outlines the investment framework's cycle.

Figure 2A

The agriculture investment framework

Source: Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

2.3.1 Well-designed investment framework

The department's agricultural investment framework enables effective, evidence-based RD&E priority-setting and project selection in line with the national framework. This is achieved through:

- quarterly industry fora that give the department the opportunity to discuss existing and potential future industry priorities with key stakeholders in its four priority industries—dairy, grains, horticulture and sheep and beef

- regular meetings of industry leadership groups(ILG), made up of departmental staff, that provide advice to senior management on priorities, investment allocation and stakeholder management in its four priority industries

- an annual planning conference where draft four-year industry investment plans—which are produced by ILGs and specify RD&E Priorities and proposed investment shifts—are discussed by senior management before being finalised

- an annual investment conference where current and proposed agricultural RD&E projects are presented to senior staff for comments and discussion

- providing opportunities for evaluations of past projects to inform future investment decisions.

The department has also regularly reviewed its investment framework with a view to making ongoing improvements. A 2012 review commissioned by the department found that the framework was transparent, promoted strategic focus, facilitated consultation and had positive impacts for RD&E.

2.3.2 Adequate project selection criteria

The investment framework's selection criteria for agricultural projects provide a logical basis on which to make decisions about RD&E investments. These criteria are summarised in Figure 2B.

Figure 2B

Selection criteria for agricultural projects

|

(a) ‘Route to market’ refers to the way the results of research and development are further developed and delivered to the target audience—the next users or end users of the results.

(b) Reviewed after all project proposals are assessed individually.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

2.4 Aligning priorities and investments

There is alignment between the department's industry-level RD&E priorities and projects and the state and national frameworks.

2.4.1 Industry-level priorities in line with national framework

Victoria's industry-focused agricultural RD&E priorities are in line with the national framework.

The areas for which the department has a lead role under the national framework—dairy, grains, horticulture and sheep meat—strongly influence prioritisation. The department's focus areas, such as almonds (horticulture) and pulses (grains), are also in keeping with the national framework.

Since 2007, the Victorian Government and the department have had a central role in administering the national framework. In a 2009 joint statement of intent with the other states and territories, the government committed to 'work collectively and collaboratively to implement the Framework and underpinning industry and cross sector strategies' and to put into practice the framework's nine principles. The department has largely put these principles into practice. The principles required that the states endeavour to at least maintain funding levels, but funding across Australia has been declining since the 1970s. Victoria's funding has declined by about $6 million, or 10 per cent, since 2013.

2.4.2 Industry-level priorities in line with policies and strategies

The department's agricultural RD&E priorities for each of its four priority industries are also in line with the relevant state policies and strategies, including the 2012 Growing Food and Fibre initiative and the 2014 Food to Asia Action Plan. The main objective of the department's Agriculture, Energy and Resources strategic plan—'increasing productivity'—is clearly in line with these and sets the objective for RD&E investment planning in all four industries. This broad objective is also in line with the industries' objectives and the aims of the national RD&E strategies.

The national RD&E strategies strongly influence the selection of investment themes in the four industries. These themes are wide ranging and change little from year to year. They include but are not limited to:

- dairy—flexible dairy feeding systems

- grains—more efficient grain production practices, more profitable farming systems, and better management of risk while maintaining or improving grain quality and the natural resource base

- horticulture—innovative production systems—advanced, efficient production for the 21st century

- sheep and beef—flexible animal production systems.

The strong influence of the national framework appropriately reflects its purpose, which was to harmonise RD&E efforts so that each state focused on areas that were strategically important and reduced duplication with other states.

2.4.3 Investments in line with industry-level priorities

The department's RD&E project investments over the past three financial years have been made in line with its four priority industries. Figure 2C details the department's key projects, which comprise strategic groupings of all its individual RD&E projects.

Figure 2C

The department's key projects for agricultural RD&E

|

Industry |

Key project |

|---|---|

|

Dairy |

Productive Dairy Dairy Industry Services |

|

Grains |

Grains Productivity Grains Industry Services |

|

Horticulture |

Horticulture Productivity Horticulture Industry Services |

|

Sheep and beef |

Productive Red Meat Beef and Sheep Industry Services |

|

Cross industry |

Animal Biosciences Plant Biosciences Biosecurity R&D Bioprotection R&D Service Innovation |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The alignment between the department's project selections and the detailed priorities set in its four-year industry investment plans is discussed below.

2.5 Gaps in applying the investment framework

Inconsistent application of the key steps in the department's investment framework and a lack of evidence showing how detailed decisions have been made have limited the reliability and transparency of the department's decisions regarding RD&E priorities and projects. The department has recognised the need to improve its approach to setting RD&E priorities for cross-industry matters and has revised the structure of its ILGs to support this.

2.5.1 Key framework steps followed inconsistently

Over the past five years, the department has not consistently applied all key steps of the investment framework's annual cycle as intended.

No planning conference was held in 2015, 2013 or 2011, limiting the reliability of RD&E priority-setting in these years. No investment conference was held in 2014, limiting the reliability of detailed RD&E investment decisions for that year and assurance that they were in line with agreed priorities.

Quarterly industry stakeholder fora—which started in 2014—have not taken place since the second quarter of 2015. The department noted that the limited availability of participating industry bodies makes it difficult to schedule these fora every three months.

The department told us that machinery-of-government changes in 2013 and 2015 contributed to it not following its investment framework completely.

2.5.2 Gaps in transparency of specific decisions

Lack of evidence to support specific priority-setting decisions

The department's detailed RD&E priorities have not been set transparently. Specifically, the department is lacking documents that show:

- how the department's ILGs have gone about filtering potential RD&E priorities, including assessing the merits and impacts of investing or divesting in different priority areas

- the department's reason for annual changes in the RD&E priorities

- the extent to which RD&E priorities have been shaped by industry engagement and past reviews and evaluations of RD&E programs

- how the department has considered the role and merits of government investment compared to private investment

- senior managers having agreed to RD&E priorities before industry investment plans are finalised.

Likely project benefits assessed but adherence to selection criteria not always clear

Under the investment framework, individual branches in the department's Agriculture and Resources Group have the flexibility to prepare and assess RD&E project concepts and proposals in a way that is fit for purpose. This flexibility has led to the Agricultural Research and Farm Services branch and the Biosciences Research branch each adapting the investment framework's selection criteria to meet their respective needs. In principle, this is reasonable—so long as the criteria remain meaningful and aligned. It reflects differences in the nature and scale of RD&E activities between branches.

Both branches estimate net benefits for their project proposals, albeit in different ways:

- The Agricultural Research and Farm Services branch assesses each proposal using a 'rapid net benefits assessment'—a tool that allows scoring and ranking of proposals against its adapted criteria. The rigour of these assessments is adequate considering that its proposals are typically more numerous and smaller in scale compared to biosciences research proposals.

- In contrast, the nature of biosciences research means that the Biosciences Research branch typically invests in fewer RD&e projects but its projects are larger and longer term, developed as national or international programs. This results in bioscience project investments that are supported by more detailed, collaborative planning and assessments of likely benefits.

The Biosciences Research branch's project planning is extensive, and there is evidence that its investment decisions align with its adapted selection criteria. However, this alignment needs to be more clearly and consistently documented before final decisions about investments are made.

Figure 2D

Case study of bioscience project development: DairyBio

|

The Dairy Futures Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) was a large national research partnership involving the department, Dairy Australia, La Trobe University and 12 supporting partners from Australia and overseas. It comprised a total investment of $128 million over 6.5 years, ending in June 2016. It focused on improvements to pastures and cattle that would reduce production cost and farmers' exposure to external price shocks and allow for more production. The Dairy Futures CRC's research program is transitioning to the DairyBio program—a five‑year, $45 million investment partnership between the department and Dairy Australia. DairyBio and its transition from the Dairy Futures CRC was informed by:

The department commissioned two projects under DairyBio to start in 2015–16—one aimed at demonstrating the value of genetics and herd improvement in improving rates of genetic gain, and the other aimed at integrating large genomic and milk infrared data to improve the profitability of dairy cows. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

Aligning key project plans more clearly with industry investment plans

The department can improve how its key project plans demonstrate alignment with the objectives, themes, priorities and changes in its four-year industry investment plans. Although these key project plans provide commentary describing the proposed changes in investment for the upcoming financial year, it remains difficult to reconcile this with the corresponding investment plan.

2.5.3 Focusing better on cross-industry RD&E

The department has major RD&E roles under the national framework for six cross‑industry areas. In fulfilling these roles, it has chosen to identify cross-industry priorities and deliver corresponding RD&E projects through its four industry-themed investment plans, rather than through dedicated cross-industry investment plans. However, the extent to which the four industry investment plans address cross-industry issues varies.

As part of the department's 2014 planning conference, it recognised the need to develop a better approach to addressing cross-industry RD&E priorities identified in the industry investment plans. This has led to the department introducing two new cross‑industry ILGs in 2016 focused on:

- soils, water and climate change

- adding value to Victorian agriculture.

Measuring grain growth and quality in response to elevated levels of carbon dioxide in experimental field trials. Photograph supplied by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

The department's potential to identify cross-industry issues has also been enhanced by recent changes to its industry-focused ILGs. For example, the scope of its sheep and beef ILG has been broadened to include all livestock industries, which allows it to better focus on animal welfare issues.

It is too early to assess the effectiveness of the new ILG structure in addressing the department's previous lack of focus on cross-industry RD&E priorities.

2.6 Strategic approach to investment

The department has carried out a range of strategic work that has increased the efficiency and effectiveness of its agricultural RD&E. Its current strategic directions are articulated in a wide range of documents, but there is no overarching strategy or document that brings these together clearly.

2.6.1 Benefits of past strategic planning

The strengths of the department's current approach stem from earlier strategic planning. These strengths include:

- significant investments in RD&E facilities and capability, most notably AgriBio, a $288 million joint venture with La Trobe University that provides an agricultural biosciences R&D facility

- signing longer-term bilateral investment agreements with several key stakeholders

- introducing ILGs to provide industry-specific advice to support setting priorities and making decisions about investments

- its contribution to establishing and administering the national framework.

2.6.2 No overarching strategic direction documented

The current investment framework and other planning documents do not clearly identify and communicate the general principles that underpin the department's approaches to attracting and growing investment, or its risk appetite for doing this. This includes the amount and types of project investments it is prepared to make, given the level of benefits it seeks from these investments, and the amount and sources of co‑investment for these, both existing and new. The department also does not clearly identify what new approaches and incentives it will promote to encourage innovation or what capability mix it needs across the agriculture portfolio to deliver its forward plan.

Some aspects of the department's strategic direction are fragmented across a range of separate documents or are known by staff but not recorded. These include its principles and models for considering the role of government investment and how the role is evolving in agricultural RD&E and innovation.

Some of the strategic direction for agricultural RD&E in these areas was included in the former Department of Environment and Primary Industry's 2014 Science Strategy, but the current department does not have an equivalent strategy.

A range of the department's documents already detail many elements of an investment strategy. This places it in a good position to more clearly and cohesively communicate the key elements to staff, to clarify its aims and directions for RD&E, and to more closely guide investment decisions. It could also develop a 'road map' to link this overarching strategy to the relevant strategies and plans that collectively provide the detail of its approach.

2.7 Industry co-investment for RD&E projects

The amount of co-investment in a proposed RD&E project and the relative role of government investment are key elements of the department's project selection criteria. In practice, this means that projects should only proceed when:

- a market failure exists

- the balance of co-investment aligns with the potential beneficiaries.

Figure 2E shows varying levels of co-investment for RD&E projects in the department's priority industries since 2013–14.

Figure 2E

Investment in agricultural RD&E, 2013–14 to 2015–16

|

Industry |

2013–14 |

2014–15 |

2015–16 |

Proportion of external funding |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Internal ($ million) |

External ($ million) |

Internal ($ million) |

External ($ million) |

Internal ($ million) |

External ($ million) |

||

|

Dairy |

20.62 |

16.94 |

19.15 |

16.65 |

17.43 |

15.15 |

46% |

|

Grains |

15.09 |

20.72 |

14.44 |

24.97 |

14.16 |

21.93 |

61% |

|

Horticulture |

10.91 |

4.52 |

11.02 |

3.97 |

9.57 |

3.91 |

28% |

|

Sheep and beef |

13.81 |

3.89 |

13.61 |

3.73 |

12.46 |

2.70 |

22% |

|

Cross-industry |

5.07 |

5.34 |

4.43 |

2.73 |

5.58 |

5.40 |

47% |

|

Total |

65.50 |

51.41 |

62.65 |

52.05 |

59.20 |

49.09 |

45% |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office, using data provided by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

External partnership agreements have been important to the department's ability to secure co-investment for RD&E projects in Victoria's dairy and grains industries. Conversely, the absence of similar funding agreements focused on the sheep and beef, horticulture, and soil and water sectors means that the co-investment for RD&E in these areas is small by comparison. The department acknowledges that the co‑investment for RD&E projects in these areas is unbalanced and not in line with its project selection criteria.

2.8 Reviewing roles under the national framework

In early 2016, the committee responsible for overseeing the national framework requested that all states and research organisations review their nominated major priority, support and link roles. After its review, the department plans significant changes to its national RD&E roles. These changes have been approved by the department but still need to be negotiated with other partners in the national framework.

2.8.1 Planned changes reflect a more targeted approach to RD&E investment

If implemented, the department's proposed changes will mean:

- more targeted research in priority industries

- less productivity-focused research in industries where there is inadequate co‑investment

- are aligned focus on research areas that have greater public benefit such as biosecurity, traceability, animal welfare and value chain efficiency.

Using smart phone apps to rapidly identify plant pests and diseases.Photo supplied by the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

2.8.2 Planned changes informed by evolving RD&E system and capacity challenges

The department's internal briefings about its planned changes note that there 'has been significant change in the research and funding environment' since national roles were agreed in 2009, where the national model for RD&E now has:

- more industry, private-sector bodies and universities doing research

- more emphasis on governments doing focused research that is often more strategic

- more need for research to be translated and packaged to improve access for a wide range of organisations that provide extension services

- both industry and the private sector seeking to accelerate R&D outcomes and economies of scale through regional hubs and precincts.

There are also indications that the department needs to realign its national roles with its existing capability and capacity. Specifically, the briefings note that:

- its planned changes reflect the 'significant fiscal pressures and the competition for government funding from across the economy'

- its 2009 commitment to be a major research provider across 10 areas—while also having a central role in administering the national framework—'was an ambitious commitment, and to an extent an over-statement of the department's research role in some areas'.

Recommendations

That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources:

- consistently apply its agriculture investment framework to set research, development and extension priorities, make investment decisions, and plan for and use evaluations.

- prepare an overarching investment strategy for agricultural research, development and extension that guides investment decision-making by clarifying the role of government and describing its approach to:

- fulfilling its major, supporting and linking roles under the National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework

- promoting and encouraging innovation

- choosing and preparing suitably co-invested, collaborative research, development and extension projects

- aligning investment decisions with its risk appetite

- developing and maintaining the capability of staff and facilities.

- clearly and consistently document its research, development and extension priority-setting and investment decisions so that it can demonstrate:

- its rationale for agreed annual changes in priorities

- how priorities have been shaped by industry engagement and past reviews and evaluations of research, development and extension programs

- that it has considered the role and merits of government investment in setting priorities

- how project investment decisions are in line with the agriculture investment framework's project selection criteria

- how project investment decisions are in line with the objectives, themes, priorities and changes in the corresponding four-year industry investment plans

- how investment decisions are informed by its investment strategy.

3 Delivering R&D results to farmers

At a glance

Background

The way that research and development (R&D) results—such as information, products and services—are further developed and delivered or disseminated to farmers and others who use them is often called the 'route to market'. Accelerating the dissemination and adoption of R&D results has been identified as one of the biggest challenges facing Australia's agricultural research bodies.

Conclusion

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) has had many successes delivering R&D results to farmers. However, the department can do more to maximise the reach, accessibility and impact of its work by improving its route-to-market planning and engagement with farmers and other users.

Findings

- The department's service delivery model is well designed but would benefit from consistent engagement with farmers and service providers early in project development.

- For many projects, the department identifies only generic routes to market rather than targeting specific audiences and identifying the most promising ways of delivering the results.

- Although the department has had many project successes, it does not have good oversight of its approach to, and success in, engaging the right audiences and selecting the best routes to market across all of its projects.

Recommendation

That the Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources improve how it disseminates R&D results, including by better identifying the audiences and routes to market for its projects, managing risks, and overseeing and measuring its overall success.

3.1 Introduction

'Route to market', or 'path to impact', refers to the way results of research and development (R&D) are further developed and delivered to the target audience—the next users or end users of the results. These results commonly include information, products or services. In agriculture, the users are most commonly farmers, service providers such as agricultural consultants, industry bodies, other researchers, policy analysts and government agencies.

The Productivity Commission's 2011 report Rural Research and Development Corporations identified that accelerating dissemination and adoption locally was one of the biggest challenges facing Australia's agricultural research bodies.

For most R&D activities, the selected route to market is through public dissemination. Examples include making results available online, publishing them in peer-reviewed journal papers, mobile applications, in online farmer networks or in agricultural media, and disseminating them via field demonstrations and workshops. The less common route to market is through commercialisation, where new technology or information is licensed or sold on a commercial or cost-recovery basis that generates income. Commercial routes include licensing or selling a patent and plant breeding rights.

Identifying and protecting intellectual property created as a result of R&D activities can help to maximise the benefits of the work, for both public and private routes to market.

3.2 Conclusion

The Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources (the department) has made route to market a critical component of its investment decisions and project delivery. Although it has had many successes in delivering its R&D results to farmers, it can improve the way it targets the proposed audience and identifies preferred channels for delivering the results, to help it deliver greater innovation and changes to current agricultural practices.

A more tailored approach that extends beyond the department's traditional audiences and delivery channels is likely to help deliver the innovation and practice change needed to significantly boost productivity.

The department needs to focus specifically on overseeing the implementation of its engagement model and its effectiveness in using the route to market to maximise the reach, accessibility and impact of its work, across more than 300 projects.

3.3 Engaging with farmers and service providers

The department's approach to ensuring that its research, development and extension (RD&E) work results in practice change and improved productivity remains heavily influenced by its 2009 Better Services to Farmers strategy. This strategy was aimed at improving the targeting, accessibility and relevance of the department's development and extension services.

To achieve this, the department changed its service delivery model in two ways:

- exiting some service areas where consultants and other organisations were providing services

- focusing on working cooperatively with private service providers in other areas, to jointly deliver extension services.

This change to the delivery model followed a period of growth in the number of private providers delivering extension services and coincided with other state governments changing the way they deliver agricultural extension activities.

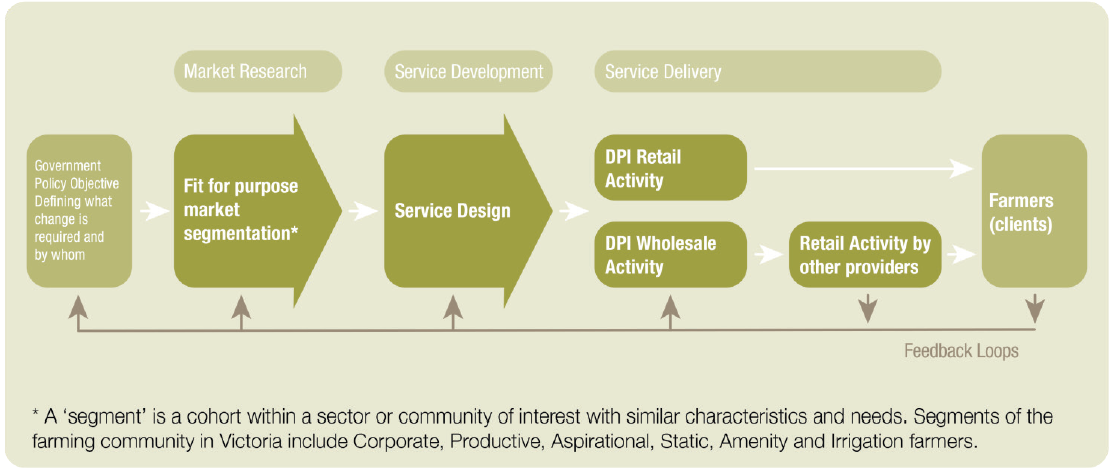

Under the new model, the department identifies target end users—specific groups of farmers—and then works in partnership with private service providers to:

- shape information, products and programs for the service providers to deliver to those farmer groups

- build the service providers' capability to deliver the information, products and programs.

This model is illustrated in Figure 3A. Its direct work with farmers is more focused on aspects of farm management that deliver 'public good', such as environmental management and biosecurity.

Figure 3A

Components of the Better Services to Farmers service delivery model

Source: Department of Economic Development, Jobs, Transport & Resources.

The department's Horticulture Industry Network program began in 2009 and was designed to follow this model—see Figure 3B.

Figure 3B

Case study of the new service delivery model —the Horticulture Industry Network program

|

Since 2009, the Horticulture Industry Network program has provided an opportunity for the department to use its new engagement model to achieve improvements in productivity, export value and efficient water use by 2020. This program has involved working with horticulture industries to build their capacity to deliver services and to help them do so in a way that is more responsive, tailored and relevant to industry needs. Working with the network's 21 industry member organisations enabled the department to reach around 160 000 growers. The department and industry jointly funded the employment of 13 industry development officers, to provide extension services to growers and develop an online network that would build collaboration between the department's researchers and the grower associations. The program's 2012 mid-term evaluation identified that many of the horticulture industries taking part thought that this new network model had improved extension services. Also, the industries employing development officers had experienced increases in:

The next evaluation is due in late 2016. |

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The Better Services to Farmers model is well designed and has improved the way the department works with the users of its RD&E results. However, the department is not engaging farmers and service providers as early, consistently and effectively as it could.

3.3.1 Good engagement model but not fully delivered

A significant change resulting from the new service delivery model was the decrease in departmental extension staff that deliver services to farmers from at least 360 in 2009−10 to less than 120 in 2015−16. The department's data indicate that, since 2009, the state government's investment in development and extension decreased by approximately 53 per cent when adjusted for inflation.

A number of examples show that the department has worked successfully with private sector service providers and has avoided competing against them—for example, the department withdrew from dairy productivity extension when Dairy Australia increased its focus on this area. In its commercial activities, the department has shifted its focus, too—for example, as the private plant breeding sector has grown, the department has shifted its focus from breeding to pre-breeding for some plant varieties.

Although the model has been in place for seven years, the department has not assessed the extent to which the model has improved the targeting, accessibility and relevance of its services. The department does not know whether it achieved the initial targets of reducing time to adoption by 25 per cent and increasing audience reach by 50 per cent.

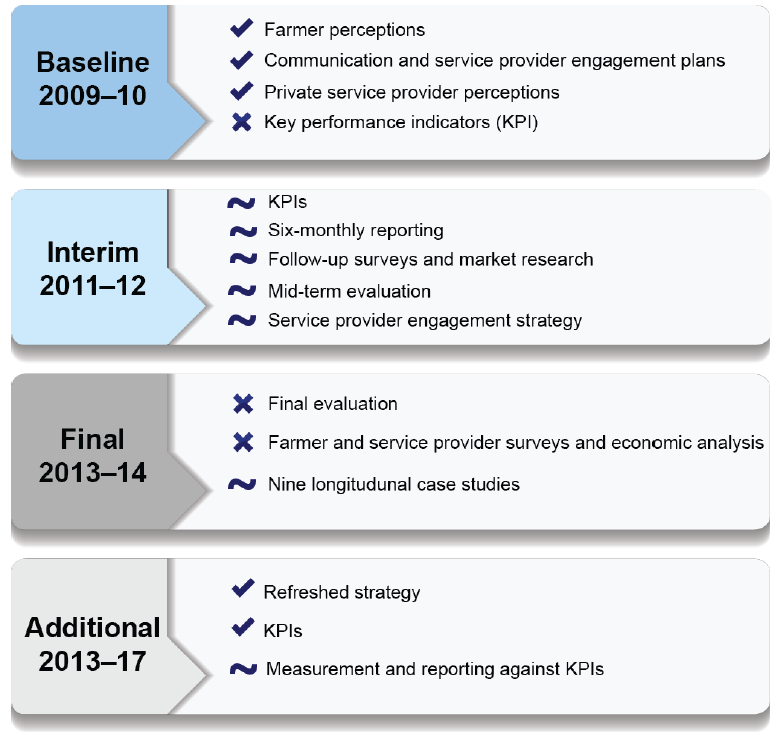

The department had a four-year plan to monitor and evaluate its success in delivering the model, but it did not follow through with many planned activities such as the final evaluation, as shown in Figure 3C.

Figure 3C

Progress monitoring and evaluation of the new development and extension model

Note: ✔ = successfully completed elements, ~ = partially completed, ✘ = not completed.

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The interim reports, surveys and mid-term evaluation identified some successes flowing from the model but also some poor progress.

By 2012, many farmers and service providers considered that the department had increased the relevance and accessibility of its services, that it had increased collaboration with service providers and that it was better targeting the audience for its work. However, improvements had not been achieved consistently in all agricultural RD&E activities, and poor performance indicators and data collection made it difficult to measure progress. The department had not engaged strategically with service providers, and the department's staff lacked a shared understanding of how to partner with them.

The department identified some reasons for this, including a lack of accountability for delivering the strategy, an absence of leadership for the changes required and inadequate resourcing.

The department responded to some issues, such as insufficient data collection, and reissued the strategy in 2013—but it did not change its overall approach to putting the strategy into practice. From late 2013 to 2015, progress on implementing the strategy was affected by staff reductions to meet government efficiency targets and the transfer of the agriculture group between departments as a result of machinery-of-government changes.

The department also identified new performance indicators in 2013. It has measured its progress against some of these indicators since 2014–15, meeting the targets set. Recent evaluations of its larger programs show many successes in delivering this partnership approach, particularly in the beef and sheep industries.

3.3.2 Engagement risks not monitored as planned

The Better Services to Farmers strategy had also identified several risks that were common in the experience of other international jurisdictions where they had moved from working directly with farmers to working only with private service providers. The strategy was designed to mitigate these risks, particularly those associated with the new model of partnering with private providers to develop and deliver services.

However, the department did not put additional risk management measures into practice and has not formally or systematically assessed the extent to which it has managed these risks. It gains some assurance from measuring client satisfaction and monitoring the development of partnerships with the private service provider sector. However, information from its reviews—or, in some instances, a lack of information—suggests that it is likely that the department remains exposed to several risks, including:

- lack of integration of productivity and environmental or social goals

- marginalisation and reduced credibility of the government department, particularly with farmers

- impact on small and/or remote landholders

- loss of skills, knowledge and staff motivation in the public sector.

3.4 Selecting the audience and delivery methods

The department can do more to ensure that its R&D results and information are effectively tailored, accessible and targeted to the right audience. For many projects, the department identifies only generic audiences and pathways rather than selecting more specific approaches based on detailed considerations and analysis.

This undermines its investments in R&D and constrains innovation—it limits the department's ability to maximise the number of farmers it reaches with its information, products and services and the rate at which farmers adopt new practices.

3.4.1 Clear, largely sound requirements

The department's investment framework and project monitoring, evaluation and reporting processes require end users and routes to market to be considered early in the development of projects and during delivery. They do not specify how this should be done, although the National Primary Industries Research, Development and Extension Framework's extension principles and the department's own agriculture intellectual property framework provide more detailed guidance.

There is a hierarchy of state, departmental and agriculture-specific intellectual property policies and guidelines that thoroughly detail the principles and steps that the department needs to follow to protect and commercialise its intellectual property. The department has considered these policies and guidelines in preparing its investment framework and its project development and management processes.

3.4.2 Some good practices

The department carries out general market research in all agriculture industries to understand its farmer and service provider audiences, and carries out specific research for some individual projects. It also explores the potential of new channels and tools to disseminate the output of its R&D work.

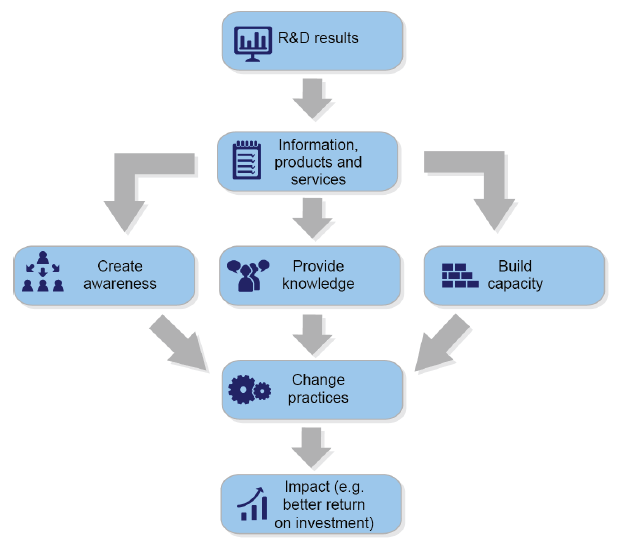

The department also aims to use knowledge about how people learn and what makes people change practices to work out the level and format of information it delivers and to work out which users and farmers to target, as shown in Figure 3D. This approach has been used well on some projects but not used at all on others.

Figure 3D

How R&D can lead to practice change

Source: Victorian Auditor-General's Office.

The department uses a range of other good practices on some projects to identify the target audiences and routes to market. These include:

- clearly aligning the selection of delivery channels/tools and the associated communications strategy for the project with knowledge of the issues, barriers to adoption and information needs of the target audience

- involving users in designing the project

- documenting risks to the project and intellectual property considerations.

3.4.3 Planning often too generic to be useful